The name P. Ramlee is likely to ring a bell for those who are familiar with Southeast Asian film. Luminously cast in film history narratives, P. Ramlee is frequently touted as the most outstanding star of Malay and Malaysian cinema, bar none. Well-loved by fans and critics for his charisma and onscreen/onstage achievements, the performer is also highly regarded for being amongst the first in the Malay community to have directed a film. His fervent championing of local stories with a social realist touch has by now become a common motif in the numerous articles that examine his auteuristic traits.Footnote 1

Described as ‘a legendary figure whose cultural bequest lives on for ever in the hearts of all who love Malaysia’, Ramlee features prominently in grand narratives of Malay cultural nationalism.Footnote 2 His contributions to Malay cinema are routinely articulated as forming the foundational blocks of Malaysian national cinema, or a pinnacle that Malay cinema had once reached. His old residence in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, has even been converted into a memorial gallery that purportedly serves to ‘encourage research and study in national arts and culture’.Footnote 3 In a recent study, Adil Johan points out that the state-endorsed narrative regards Ramlee as a bastion of Malay ethnonational purity and artistic greatness, effectively benchmarking standards of what constitute ‘authentic’ Malaysian film and music. Such nationalist iconicity is, in turn, fuelled by the culturally potent sentiment of ‘pity’ (kasihan), evoked through an emphasis on Ramlee's decline and lack of recognition towards the end of his life. Through such discursive framing, the multitalented P. Ramlee has become nothing short of an icon or embodiment of Malaysian localism and (ethno)nationalism.Footnote 4 Indeed, it is hard to dispute that localising and nationalising impulses motivate much of the narratives surrounding P. Ramlee in Malaysia today.

Overshadowed by the sheer volume and fervour of such narratives, the visionary's attempt at transnationalising Malay cinema has hitherto been left out of sight. It remains a little-known fact that Ramlee had aspired to bring Malay filmmaking out of the region into the city of Hong Kong, at a time when Malay film production, distribution and exhibition were still largely confined within the Malay Archipelago. Scripts and songs were written in anticipation of what would have been the first few transnational productions ever undertaken by the Malay film industry. Farewell parties were held and publicised widely in bestselling newspapers. Names of the cast and crew, as well as their respective flight information, were released to the public. By 1963, P. Ramlee seemed ever ready to set the precedent of making Malay films in Hong Kong.

This fascinating but understudied episode, referred to as Ramlee's ‘Hong Kong endeavour’ in this article, prompts critical examination. Deviating from standard posthumous narratives that valorise him as bearer of (ethno)nationalism and localism, this episode complicates the characterisation of the legendary star, and unsettles conventional wisdom about Ramlee's contributions to Malay and Malaysian cinema. More importantly, it prompts a critical reflection of Malay and Malaysian film history, particularly our understanding of the industry's crucial transitional period, that is, the transformative 1960s.

Not unlike the case in much of the scholarship on P. Ramlee, Malay and Malaysian film studies appear to be overdetermined by a similar kind of paradigmatic nationalism and localism. As the oft-cited story goes, the 1960s was a crucial period in Malay and Malaysian film history. This was when the old multiethnic studio system became increasingly untenable, enabling Malay cinema to take a decisive and seemingly unstoppable ethnonationalist turn. During this time, burgeoning calls for greater Malay and local autonomy, coupled with growing ethnonationalist sentiments within the industry, ushered Malay cinema into a new era described by historians today as ‘independent’ or ‘bumiputera’ (‘sons of the soil’). All these happened in tandem with key political events that ended decades of British colonial rule: the declaration of independence for the Federation of Malaya in 1957, that of the Federation of Malaysia (which included Singapore) in 1963, separation from Singapore in 1965, along with the coming to power of Malaysia's pro-Malay ruling party, the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO).Footnote 5 Focusing exclusively on events which pushed for localisation and nationalisation within the industry, existing film history narratives propagate and reinforce the view that, transiting from the colonial-era studio system into Malaysia's national cinema seemed to be an inevitable progression for Malay cinema in the 1960s. Against the backdrop of decolonisation and rising (ethno)nationalism, localisation and nationalisation seemed to be the only reasonable path that Malay cinema could have taken during those transformative years.

The unilaterality of such narratives is arguably legitimatised by what happened in the decades that followed. In the 1970s, Malay cinema became indisputably synonymous with Malaysian cinema at the official level. The 13 May 1969 racial riots played an instrumental role here, for it intensified Malay ethnonationalist sentiments and gave rise to the overarching pro-bumiputera New Economic Policy (NEP, 1971–90). Henceforth it became a legal requirement for film companies in Malaysia to be headed by Malays.Footnote 6 From the late 1960s through to the late 1970s, bumiputera or independent film production companies helmed by Malays indeed ‘mushroomed like a harvest season gone haywire’, as one commentator puts it.Footnote 7 Crucially, in 1981 the National Film Development Corporation Malaysia (FINAS) Act was passed, decreeing that, in order to qualify as a Malaysian film, it must be made in the national language, which is Bahasa Melayu (the Malay language).Footnote 8 By this time, Malay cinema became formally recognised as the national cinema of Malaysia. As Khoo Gaik Cheng aptly puts it:

the mainstream Malay film industry … since the fall of the studio system in the 1960s, has ridden the ethnonationalist wave of the NEP and its cultural policies. The film industry is still regarded as a site of ethnonationalism, one whose necessary existence or raison d'etre is based on reflecting and perpetuating ‘Malaysian’ culture, defined narrowly by members of the privileged ethnic majority as Malay.Footnote 9

Although this refrain of localisation and nationalisation is helpful in explaining the transitional 1960s, the lopsided emphasis placed on the ethnonationalist turn routinely obscures historical occurrences—and, by implication, alternative viewpoints—that fall outside of these paradigms. Despite being more the exception than the rule, transnational occurrences similar to P. Ramlee's Hong Kong endeavour did also take place in the 1960s, alongside the more well-known localising and nationalising initiatives. Existing scholarship is not entirely incognisant of these events, but works that do acknowledge them tend to regard or dismiss them as special cases which do not fit into the main narrative. At times they are even disavowed of a place in Malay(sian) film history.Footnote 10 Yet these seemingly insignificant occurrences warrant greater attention because they destabilise the stronghold that the localisation/nationalisation refrain currently holds over Malay and Malaysian film narratives. They alert us to the possibility that Malay cinema's seemingly unstoppable ethnonationalist turn in the 1960s was perhaps not as inevitable as previously thought, and that the future of Malay cinema was perhaps imagined and pursued in more ways than one. When transnationalism is pushed to the fore, questions about Malay cinema's transitional period abound: If, indeed, ethnonationalism began to form the dominant concern, even zeitgeist, of the 1960s, why did transnational considerations nonetheless surface within the Malay film industry during this time? How did transnational events and thought interact with the then burgeoning force of localisation and nationalisation? How does this impact present understandings of post-studio era Malay cinema development and the roots of Malaysian national cinema?

This article seeks to answer these questions by revisiting P. Ramlee's Hong Kong endeavour. Using biographical records, newspaper reports and film magazines, I reconstruct this early moment of transnational Malay cinema, tracing P. Ramlee's earliest direct contact with Hong Kong cinema, his subsequent plans to make at least five Malay films in Hong Kong, the controversy that ensued, and the outcomes of these grand plans. In particular, I interrogate P. Ramlee's motivations and the rationale of those who had opposed his plans. Situating this episode in the context of Malay and Malaysian film histories, I posit that P. Ramlee's Hong Kong endeavour can be read as an attempt to chart an alternative future trajectory for Malay cinema. As opposed to the seemingly inevitable nationalisation route, and in contrast to the hypernationalist characterisation of P. Ramlee today, a transnational model of Malay cinema was envisioned through P. Ramlee to counteract the geopolitical changes of the 1960s.

This study further complicates the localisation/nationalisation refrain by bringing to light the role that labour movements played during this crucial period. Identifying labour activism and the film workers’ union—Persatuan Artis Malaya or Malayan Artist Union (PERSAMA)—as the key opposing force that hampered Ramlee's transnational aspirations, this article argues that, through forestalling Ramlee's alternative vision for Malay cinema from materialising, PERSAMA in no small part helped to facilitate the transition of Malay cinema into the official ethnonationalist Malaysian cinema as we know it today. As much as labour strikes directly destabilised the roots of the old studio system, the fact that union solidarity and labour concerns put an effective halt to Ramlee's transnational proposal must also be considered, in probing how Malay(sian) cinema came to be.

The first contact: Love Parade

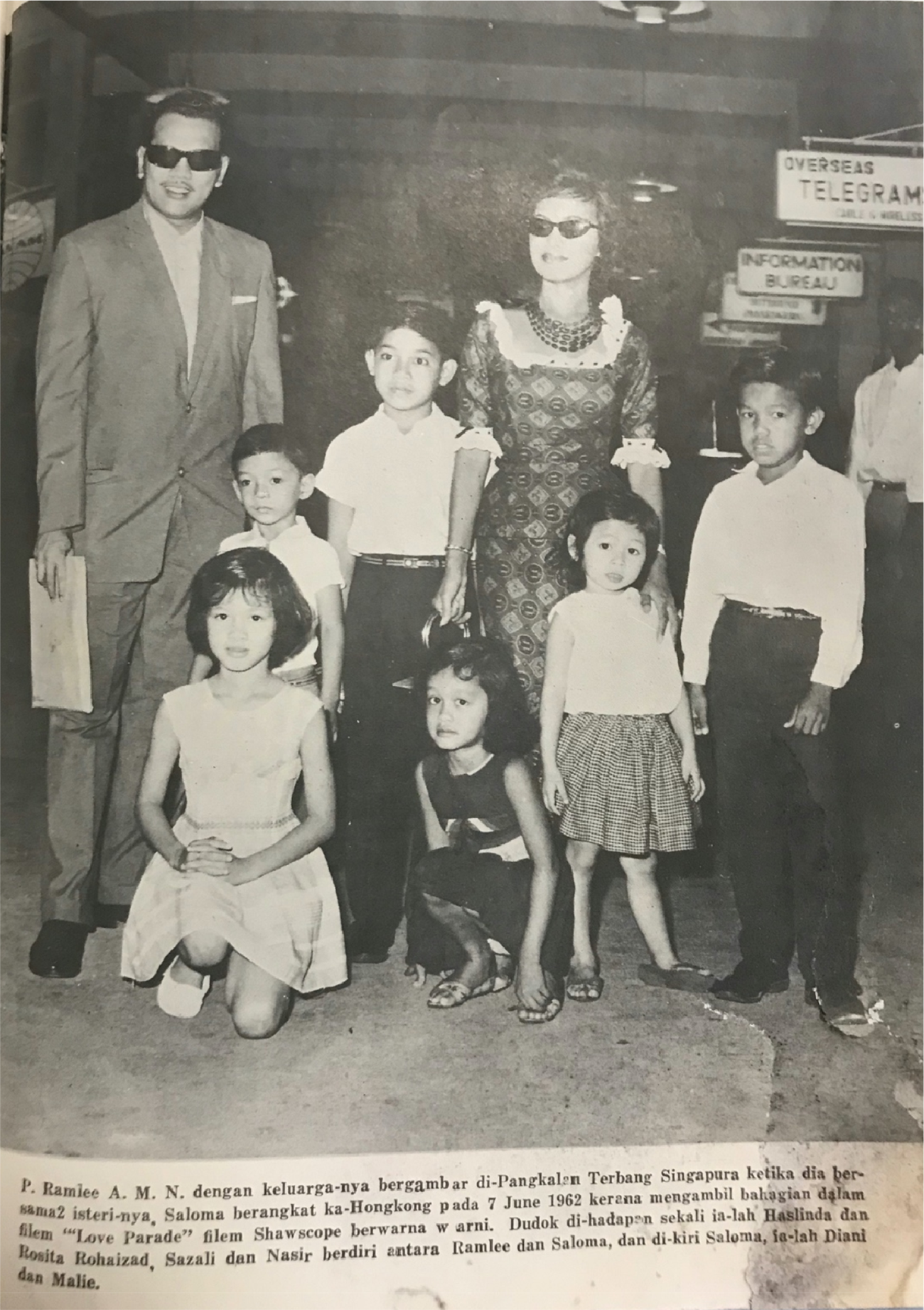

Ramlee's first foray into Hong Kong took the shape of a cameo appearance. On 8 June 1962, P. Ramlee and his wife Saloma (Salmah Ismail) left for Hong Kong to ‘make a guest appearance in a Shaw film, “Love Parade”’.Footnote 11 Figure 1 shows the duo departing from Singapore to Hong Kong. Starring Hong Kong film stars Lin Dai and Peter Chen Ho, Love Parade (花團錦簇, 1963) is a Mandarin comedy about the marriage between a fashion designer (Peter Ho) and a gynaecologist (Lin Dai). The film was produced by the Shaw Brothers (Hong Kong) Company or SB(HK). In the film, petty misunderstandings cause the couple to drift apart, culminating in a state of near-divorce. At the height of tension between the two, the male protagonist participates in an international fashion design competition. Mounting stress from the competition and his troubled marriage threaten to push him over the edge. Finally, with mediation from their friends, the couple reconciles, reestablishing love and support for one another. The film then ends on an upbeat note with a musical scene depicting the competition. A dazzling array of international fashion is showcased in this elaborate closing scene.

Figure 1. P. Ramlee and Saloma departing from Singapore to Hong Kong (Majallah Filem, 28 July 1962, p. 41).

This fashion showcase is important not only as a key plot device. It also marks the very first time Malay film stars took part in a Hong Kong film production. Donning traditional Malay clothes, Ramlee and Saloma acted as models in this fashion show. Parading their outfits gracefully, in a three minute-long sequence the couple sing and dance to the popular Malay folksong, Bengawan Solo.Footnote 12 This is preceded by similar sequences with models dressed European-style parading in the make-believe streets of Paris, and those wearing kimonos modelling in what appears to be a Japanese historical set. Filipino, Chinese and other Western fashions follow after Ramlee and Saloma's sequence. It is worth noting that the film was made in full colour (colour filmmaking only took off in Hong Kong in the 1950s), which enhanced the visual spectacle of the fashion parade.

That Ramlee and Saloma were chosen to play these roles was likely a result of intersecting industrial interests involving both Hong Kong and Malay cinemas. Fundamentally, this transnational movement was made possible, possibly also smoothened, because both stars were contracted to the very same people who produced Love Parade. The fact that the Shaw brothers owned one of the most influential Malay film production studios in the 1950s and 1960s is frequently overshadowed by the far-reaching fame of their SB(HK) studio. It bears reminding that the Shaws’ Malay Film Productions company (MFP) in Singapore—alongside Loke Wan Tho's Cathay-Keris—was a key leader in building Malay cinemas’ studio era, also known today as Malay cinema's golden era.Footnote 13 Having distributed only Chinese-language films upon their arrival from Shanghai to Singapore in the 1920s, by the late 1930s Runme Shaw and Run Run Shaw had also begun to import a variety of Indian, Western and Indonesian films. At this point they also already had in their possession a chain of 139 cinema halls across Singapore, Malaya, Indonesia and Indochina. Riding on their newfound success in the Malay Archipelago, the brothers then decided to venture into Malay film production.Footnote 14 In 1940 they turned an old warehouse on Jalan Ampas Road in Singapore into a filmmaking studio which would become the now famous MFP studio.Footnote 15

As this background is imperative to understanding Ramlee's Hong Kong endeavour, a short history of the MFP is needed here. Upon resuming operations after the Second World War, the MFP quickly became a major Malay filmmaking centre in the region. In the early days, Malay film production was organised by and large along ethnic lines: the Chinese (Shaw brothers and Loke Wan Tho, for example) provided financial capital and technical expertise, the Indians (most of them hired directly from India) assumed directorial positions, and local Malays were cast as performers. This would change in the second half of the 1950s, when the Shaws agreed to let local Malays try their hands at directing. It was precisely during this time that P. Ramlee started to explore working behind the scenes. Having achieved explosive stardom since his acting debut in MFP films such as Love (Chinta, 1948) and Fate (Nasib, 1949), in the mid-1950s this prized employee threatened to leave for Indonesia. At that time Ramlee was nearing the end of his second contract with MFP, and he had been offered a lucrative contract to work for the Persari film studio in Indonesia. As a way of keeping him in MFP, Run Run Shaw gave Ramlee the chance to direct his own film. This was backed by MFP's main officer Ja'afar Abdullah, who purportedly offered to work for free for five years if Ramlee's directorial attempt failed. Their gamble paid off. Ramlee's directorial debut, Trishaw Puller (Penarek Becha, 1955), was an instant hit. It paved the way for him to become MFP's most favoured film director, on top of being the studio's most treasured star.Footnote 16

With this knowledge, on an industrial level it is not difficult to understand why Ramlee and Saloma were chosen to front this historic move. Ramlee, Saloma, and Love Parade were intrinsically linked through the Shaws. It was a matter of transferring personnel from the Shaws’ Southeast Asian studio to their headquarters in Hong Kong. The inter-Asian cinematic network forged during the postwar period by powerful studios such as the Shaws was crucial in facilitating such transnational movements.Footnote 17 Moreover, Ramlee was the MFP's undisputed ‘golden boy’.Footnote 18 It is not surprising then, that the star was picked by the Shaws to be given this opportunity. Indeed, it would also have been a safe choice in the eyes of the Shaws. On this note it should be highlighted that Ramlee and Saloma's extended sequence stands out in the fashion showcase scene for being the only one that is not performed completely in Mandarin. The couple performed Bengawan Solo first in Malay, then a non-diegetic voice takes over, singing a Mandarin version of it to which the couple continue dancing to. The sequence then ends with the couple singing the original Malay version again. This contrasts starkly with the rest of the sequences, where models parade the stage without singing; each of these sequences is paired with non-diegetic music written in Mandarin about the respective cultures (of Paris, Japan, the Philippines, etc.). This detail illustrates how the Shaws effectively tapped upon Ramlee and Saloma's readily available (to the Shaws) talent and capabilities in this film.

Having said that, it remains a question as to why, at this point in history, the couple was invited to take part in this Mandarin film, travelling all the way to Hong Kong only to appear in a three-minute-long cameo scene. Being the shrewd businessmen they were known to be, the Shaws would presumably not have gone through such logistical trouble and incurred these extra costs if there were no perceived need for this. To further unpack this episode, I argue that we need to also consider Hong Kong cinema trends at that time. Ramlee and Saloma's short sequence in the film was undeniably a performance of ethnicity and culture. Conceived as part of a wider collection of cultural displays, this sequence was clearly added to enhance the overall cosmopolitan outlook of the fashion show. Such assertion of multicultural cosmopolitanism was very much aligned with SB(HK)'s internationalist vision at that time.

From the late 1950s till the late 1970s, Hong Kong cinema became increasingly invested in portraying a kind of modernity that articulated global links and modern aspirations. Major studios began to image ideals of the ‘international’ in their own works.Footnote 19 Films that embody global modernity, cosmopolitanism and transnational mobility, such as Love with an Alien (異國情鴛, 1957) and Air Hostess (空中小姐, 1958) started to proliferate. To a significant extent this was motivated by major Hong Kong film studios’ aspiration of becoming a leader in world, not just Asian, cinema. It is useful here to refer to Kinnia Yau and Stephanie DeBoer's illuminating work on this subject. Yau and DeBoer document this trend through a close study of SB(HK)'s co-productions with Japan, particularly the technology transfer that resulted from it. Ploughing through a host of archival materials, they posit that co-producing with Japan—then the leading film production centre in Asia—offered the Shaws ‘a possibility of access to Tokyo's holdings of advanced technologies in film production’. With this newly acquired technical capacity to produce films perceived to be attractive to a ‘world’ audience, SB(HK) was able to position itself ‘ever more proximate to the markets potentiated in its achievement of international film standards that were held to be more palatable to a developed world’. In particular, SB(HK)'s subsequent use of Eastmancolor (a kind of colour film technology developed in Japan) in their own films was thought to have brought Hong Kong cinema to the international standards of the colour age.Footnote 20 Such a turn towards the global or the international well befits Hong Kong's then-status as a ‘space of flow’ or, in Ackbar Abbas's words, a ‘space of transit’—an ‘inter-national city’ that transcends national borders.Footnote 21

In this light, Ramlee and Saloma's short performance of Malay ethnicity in Love Parade can be understood as contributing to this bigger picture. From the outset, with its overt foregrounding of scientific modernity (through gynaecology) and cosmopolitanism (through fashion design), Love Parade is unambiguously rooted in the kind of internationalist ambition and sensibility that SB(HK) was actively propagating at that time. Perhaps the most direct reflection of this is the fact that the protagonist, representing Hong Kong, eventually won first prize in the international fashion competition, beating all other representatives from around the world. Against this backdrop, Ramlee and Saloma's overt performance of Malayness not only played into SB(HK)'s vision by providing a touch of multiculturalism and cosmopolitanism to this film (albeit tokenistically). It forms part of the international fabric, alongside Paris, Japan, the Philippines, and elsewhere, that is also needed to represent this ‘inter-national’ city and assert Hong Kong's superiority in a global setting.

Although P. Ramlee and Saloma only had three minutes’ worth of screen time in Love Parade, in actual fact the couple stayed in Hong Kong for a total of ten days before heading back to Singapore.Footnote 22 Little is known about what the couple did during their stay there, or if their employers planned any other activities for them during these ten days. However, it is reasonable to deduce that the trip also enabled Ramlee to observe Hong Kong's filmmaking industry, particularly the operations of MFP's counterpart—the SB(HK) studio. Just a year after his short trip, P. Ramlee publicly announced that he would be returning to Hong Kong. Making plans to stay there for a longer period of time, Ramlee now intended to go there not as an actor but as film director; not to partake in Hong Kong Mandarin film production but to make Malay films instead. As we shall see, a similar concoction of motivating factors came into play: the intrinsic MFP-SB(HK) connection, Ramlee's favourable position within the Shaws’ orbit, and their cosmopolitan and global aspirations. Only this time, rather than in service of Hong Kong cinema's internationalist ambitions, the crossover was conceptualised as an attempt to rethink the future of Malay cinema.

Envisioning a transnational Malay cinema

Since the beginning of the studio era, Malay cinema operated predominantly within Singapore, Malaya and Indonesia. Whether in terms of production, distribution and exhibition, Malay film activities took place mainly within the Malay Archipelago, a region with a high concentration of Malay-speaking populations. In the early days, the Malay film industry was characterised more by Malay linguistic and cultural affinities across the region than by geopolitical or territorial boundaries within it. This, however, began to change by the late 1950s. During this time, more and more countries across Southeast Asia became embroiled in the struggle for independence. Anticolonial and nationalist sentiments ran high. The region turned from one that was carved out primarily by competing imperial interests into a bloc made up of distinct, sovereign nation-states.

Film industries in the region were swept along in this wave of nationalism.Footnote 23 In North Vietnam, for example, President Ho Chi Minh signed the Decree on Establishing the Vietnam State Enterprise for Photography and Motion Picture in 1953. This marked the birth of Vietnamese national cinema following years of resistance and war against the French colonialists.Footnote 24 In Indonesia the National Film Conference was held in 1959, which urged the government to establish a liaison board between the government and the film world.Footnote 25 Since the early 1950s Indonesian filmmakers were preoccupied with making what Thomas Barker has called ‘film nasional’—films that are ‘tied to the formation of an independent Indonesia in 1950, to its politics and its aspirations’.Footnote 26 As mentioned, this was generally also the case in Malaysia. By the late 1950s Malays began to call, much more assertively, for autonomy over the Malay film industry. Many in the industry envisioned a Malay cinema that would complement the sovereignty of newly independent Malaysia. More specifically, film activists made two key demands: asserting Malay cultural superiority and resisting the ‘foreign monopoly’.

Ramlee's proposed return to Hong Kong took place against this backdrop—as an alternative that went against this dominant current. In his study of the nature of independence and decolonisation reflected in Malay cinema in the 1950s and 1960s, Timothy Barnard argues convincingly that, unlike most other film industries in Southeast Asia, for the budding Malay(sian) film industry independence was not articulated in straightforward anticolonial terms. Instead of larger issues concerning the nation-state or other ethnic groups, Malay films at that time focused almost exclusively on issues that were perceived as important to Malays ethnically. The message of activist Malay films focused on independence—or ‘merdeka’—as a concept that embraced modernity for the Malay community, rather than independence of the nation-state for all citizens.Footnote 27 This approach pegged Malay cinema to an ethnocentric vision of independence and decolonisation, one that sought first and foremost to establish Malay cultural superiority as the foundational principle of a new Malay(sian) cinema.

In a way this championing of Malay cultural superiority exacerbated animosity towards the owners of the two major Malay film production studios. In a charge against ‘foreign monopoly of Malay films’, for example, the film workers’ union—PERSAMA—wrote a memorandum to the newly independent Federation of Malaya government in 1959. It claimed that ‘Malay films are produced by other races (foreigners) who reap profits on the sweat and labour of the Malays without caring for their difficulties’. It also alleged that ‘most cinemas in Malaya are owned by capitalists of other races who have monopolised the circulation of the films’, and that ‘Malay films produced by the capitalists have greatly lowered the standard of culture and art and often go against the customs and religion of the Malays’. The union thus urged the government to encourage Malays to build a film industry themselves and to impose a quota system in order to protect their productions.Footnote 28 Reading these statements in context, by ‘foreign’ and ‘other races’ the memorandum referred specifically to Chinese financiers, the likes of MFP's Shaws and Cathay's Loke Wan Tho, whose main film businesses were based in Hong Kong.

This Malay-centric take on independence, decolonisation and autonomy formed the predominant thought that circulated within the industry. Cultivating Malay cinema's local or national character defined through an ethnocentric lens seemed to be the preferred future. As Barnard puts it, by the early 1960s activists in the Malay film industry were propagating a stance that ‘played into a vision of the nation-state as a Malay state’.Footnote 29 What is constantly overlooked, however, is that the industry did also contemplate a contrasting alternative.

In June 1963, P. Ramlee revealed in the film magazine Mastika Filem that he would be making Hidayah, Seniwati, Tuah dan Tija and two other Malay films; they would all be produced in widescreen, in colour and, crucially, in Hong Kong. According to this report, the stories for these films were already submitted to the Malaysian film censorship department. Once they were approved, P. Ramlee would depart for Hong Kong.Footnote 30 Amongst the five proposed films, Seniwati would have been the first to materialise. A follow-up report was published in August the same year, stating that P. Ramlee would leave for Hong Kong very soon for at least a month to shoot Seniwati. Thereafter he would return to the Federation to wrap up the shoot. Seniwati, said to be written by Run Run Shaw himself and subsequently handed to P. Ramlee for adaptation, is purportedly about the lives of performers who were well-known in the Malay community. The film was also poised to be the first ever Malay film to be made in Shawscope (Shaws’ widescreen technology).Footnote 31

Publicity surrounding Seniwati made it seem as though it was set to happen, or at least indicates that the Shaws were serious in its implementation. In July 1963, the names of nine other personnel who would travel to Hong Kong alongside P. Ramlee were published in the widely read newspaper, Berita Harian. They include: performers Sarimah Zulkifli, Zahrah Agos, Haji Mahadi, Malik Sutan Muda, Kuswadinata, Yusoff Latiff, Shariff Dol, Ahmad Nisfu and assistant director Sudarmaji. Some other actors from Hong Kong would also be involved. These people were said to be handpicked by P. Ramlee himself.Footnote 32 It was also reported that Ramlee had begun to pen the songs for the film.Footnote 33 There were even at least three farewell parties planned for the team. Some of these were ticketed and open to the public (figs. 2 and 3).Footnote 34 A hopeful P. Ramlee commented that he might stay on in Hong Kong if Seniwati proved to be successful.Footnote 35

Figure 2. News of ticketed farewell party for Ramlee's entourage (Filem Malaysia, 13 Aug. 1963, p. 30).

Figure 3. Widely publicised celebration for Ramlee's departure (Filem Malaysia, 14 Sept. 1963, pp. 11–12).

P. Ramlee justified the need to bring Malay filmmaking to Hong Kong with a discourse that is strikingly reminiscent to SB(HK)'s internationalist vision. In a newspaper report published on 18 May 1963, Ramlee was asked why he chose Hong Kong instead of somewhere else that is ‘more culturally compatible with the Malay community’. To this, Ramlee explained that the problem of incompatibility can easily be resolved by making backdrops in the studios. The more pertinent consideration here was that Hong Kong—particularly the Shaws’ studio there—could help to elevate Malay filmmaking in terms of technology. The SB(HK) studio, then replete with one of the most advanced (and constantly improving, as we have seen above) filmmaking technologies in Asia, could provide the necessary equipment and expertise to increase the technical standards of Malay cinema. If filming was done in Hong Kong, Malay films could be shot using Shawscope technology, for example. They could also be colour-processed easily.Footnote 36 In contrast, the MFP studio at the time was severely underdeveloped. Despite being one of the most established Malay filmmaking studios of its time, the MFP was still making black-and-white films, and the crew there were neither trained in colour nor widescreen shooting.

More fundamentally, Ramlee was looking to ‘raise the status of Malay cinema to an international standard’. By tapping on the filmmaking technologies made readily available to him in Hong Kong through the Shaws, Malay films can finally ‘catch up with changes in international cinema’, becoming more competitive on the global stage. According to Ramlee, what this meant was that Malay films would then be able to better ‘attract audiences outside of the Malay Archipelago’, thus expanding the reach of Malay cinema.Footnote 37 This line of reasoning was supported by the official discourse put out by the Shaws. Ja'afar Abdullah, MFP's spokesperson and previous guarantor of Ramlee's directorial capability, claimed that both the performers and technical crew in the Malay film industry would ‘benefit from the equipment and skills that the SB(HK) studio possessed’, since ‘it was one of the most technologically advanced film studios in Asia at that time’. This would help to improve the industry's outlook and Malay cinema's position in the world.Footnote 38

In other words, Ramlee's Hong Kong endeavour, this time encompassing the prospect of making Malay films in Hong Kong, was not motivated by a desire to find appropriate settings for the films as is usually expected of on-location shoots. It was the accessibility to advanced filmmaking technologies and, by extension, pathway to international recognition that Ramlee was after. Just as Hong Kong cinema had done through working with their Japanese counterpart, it was believed that Malay cinema could also rise through the ranks and into the markets of world cinema by connecting with those in the lead. SB(HK) was to be the springboard for Malay cinema out to the wider world.

Although his argument was principally techno-developmental in nature, Ramlee's proposal can in fact be understood as a response to newly configured national realities. As we have seen, sociopolitical upheavals were reshuffling the dynamics of filmmaking in the region. Growing ethnonationalist trends both within the Malay film industry and Malayan/Malaysian society at large were threatening to uproot the very foundations of the ‘foreign-owned’ MFP. Compounded with a myriad of other destabilising factors, the future of the MFP became highly uncertain and indeed, the Shaws themselves were becoming visibly disinterested in maintaining MFP's operations.Footnote 39 Essentially what Ramlee did was to present an alternative way out, envisioning a future for the MFP through directly transplanting its operations to Hong Kong. Rather than revamping the structure from within to accommodate with the changing times (like most of his peers were calling for at that time), Ramlee saw the potential of directly migrating the business to a presumably more viable base as another way of sustaining Malay cinema.

Ramlee's proposal also responded to immediate market difficulties which resulted from the hardening of new national borders and creation of nation-states. Indonesia comes into the picture here. Although the Singapore-based MFP and Cathay-Keris remained the stronghold of Malay film production throughout the 1940s and 1950s, by the 1960s studios based in Indonesia rose as a major contender in the field. Leaders in the industry such as the prominent Usmar Ismail rallied for the development of Indonesia's national cinema. Following Indonesia's postwar independence, initiatives were also increasingly put in place to protect and develop Indonesia's national film industry. Significantly, in 1956 Indonesia's Minister of Education and Culture established the Indonesian Film Council (Dewan Filem Indonesia), which pushed for import restrictions to be imposed on Singapore- and Malayan-produced Malay films. The situation worsened when political relations between Malaya and Indonesia began to strain after talks on the formation of the independent Federation of Malaysia, which began in 1961. Tensions between the two rose rapidly and Indonesia eventually declared a state of confrontation (Konfrontasi) with Malaysia (1963–66).Footnote 40

What this rupture of diplomatic ties spelt for Malay cinema was the closure of the Indonesian market for films produced in Singapore and Malaya. This drastically shrunk the Malay film market for the MFP as Indonesia was historically the largest and most lucrative market for Malay films made in Singapore and Malaya. For the first time in Malay film history, what was once a cinematic network linked together by a shared linguistic and cultural affinity within the Archipelago began to segregate into discrete industries defined primarily in terms of the nation—a development that paralleled the geopolitical shifts in the region. This background provides depth to Ramlee's stated rationale of making Malay films in Hong Kong: ‘[to] catch up with changes in international cinema’ so that ‘Malay films would be able to better attract audiences outside of the Malay Archipelago’. Ramlee's desire to diversify and expand the Malay film market through Hong Kong was not simply a reflection of expansionist ambitions. It was a response to changing market conditions that were at that time severely disrupted by new geopolitics.

Reading these in the context of film history, Ramlee's proposal was potentially groundbreaking in two key ways. One, and perhaps most obviously, Ramlee's proposal was counterintuitive to dominant nationalist trends. While most in the industry were concerned with regaining local/native autonomy and steering Malay cinema to an ethnonationalistic direction, the key narrative in Ramlee's proposal was to improve the quality of Malay cinema through transnationalism. Rather than consolidating overtly localist or nationalist sentiments, in response to sociopolitical changes he identified instead the need to make Malay cinema artistically and technologically competitive on a global (not just local or regional) scale. This transnational collaboration or partnership was also a novel, perhaps unexpected, way of solving Malay cinema's problem of a shrinking market. Ramlee explored the idea of pitting against Indonesia's increasingly protectionist industry using a transnational Malay cinema model, instead of building another nationalised Malay film industry to compete with it. This demonstrates an imagined model of post-studio era Malay cinema that interestingly takes reference more from advanced Asian film industries than from budding national cinemas.

Two, instead of dismantling the old studio system to accommodate with changing times, Ramlee's proposal would have led to an extension of Malay cinema's studio era. This was a future imagined through historical continuity rather than rupture. More significantly, Ramlee's vision of a future Malay cinema was conveniently grounded in the vast inter-Asian transnational network that was already established by the Shaws through their diverse businesses during the studio era. This meant that Malay filmmaking would now become a more prominent node in the Shaws’ expansive studio network, and would no longer be restricted by a territorial imagination that identifies the Malay Archipelago as its core area of operation. Whereas most in the industry were calling for Malay cinema to break free from old systems and fit into newly configured geopolitical boundaries (at a time when the region became reterritorialised into a coalition of distinct nation-states), Ramlee's proposal instead captured the opportunity brought about by this geopolitical reshuffling to transcend old geographical limitations. For Ramlee, geopolitical shifts instead opened up the possibility of bringing Malay filmmaking—or deterritorialising it—beyond the region through extant studio networks.

Opposition and outcome: PERSAMA's intervention

In many ways Ramlee's Hong Kong endeavour was an anomaly of its times. Working against the mainstream, Ramlee met with serious challenges that proved too hard to overcome. Indeed, despite the hype, the team never left for Hong Kong. Love Parade remains his only direct engagement with Hong Kong cinema known to date. On the official front a number of reasons were given to account for this failure. The more complex and arguably most impactful factor, however, was strong pushback coming from within the industry itself. To a significant extent, labour activism amongst Malay film workers forestalled Ramlee's alternative vision of Malay cinema from materialising. In particular, opposition from the aforementioned film workers’ union—PERSAMA—put pressure on P. Ramlee to abandon the idea. Being involved in the union himself, theirs was not a voice that he could simply ignore. The complexity of the star's role, as well as seeds of failure, can be located in the contestation between P. Ramlee and PERSAMA.

In official discourse, the Shaws attributed the abortion of his plans to logistical problems. A newspaper article reported that the trip, originally planned for August, was delayed to October due to administrative procedures.Footnote 41 In one of P. Ramlee's biographies, it has been suggested that this administrative problem was in fact a lack of funding.Footnote 42 While the Shaws did not clarify the exact nature of this problem, what is certain is that the issue was never resolved. Not only did Ramlee's delayed trip fail to take flight, news about his Hong Kong endeavour also quickly died down.

Largely absent in the Shaws’ official statements was the strong resistance that they faced. Posing a greater threat to Ramlee's Hong Kong endeavour was the controversy that it created. This had firstly to do with Ramlee's special position within the Shaws’ orbit. As mentioned, to the employers, P. Ramlee was no doubt their obvious choice as leader of this project. To his fellow Malay film workers, however, it provoked further antagonism and suspicion towards both the Shaws and P. Ramlee. Prior to this, Ramlee was already a polarising figure in the industry. His colleagues were unhappy about the purported favouritism that Ramlee had been receiving since he shot to fame. For instance, director Jamil Sulong recalls that Ramlee received more than twice as much monthly salary as his peers.Footnote 43 Tellingly, a newspaper article published in August 1963 suggests that the ‘administrative problem’ obstructing the move was indeed ‘regarding the allowances of the artists involved’.Footnote 44 P. Ramlee himself also once declared that ‘the Shaw Brothers have put the business of making Malay films in Hong Kong entirely in my hands’.Footnote 45

The sense that Ramlee was receiving extraordinary treatment was widespread. By the 1960s MFP employees were allegedly separated into pro- and anti-Ramlee camps amongst themselves.Footnote 46 This sentiment structured their response towards Ramlee's Hong Kong endeavour, as revealed by a June 1963 Mastika Filem article:

The news of his departure to Hong Kong became a problem that was not easy to address, sometimes resulting in confusion amongst his friends in the studio. I think there were people who started to perceive P. Ramlee as being different from who he was before—as though he has gone so far as to forget his friends, and no longer interacted with them, in addition to other things. On the other hand, there were others who perceived the actions of P. Ramlee as hindering those who dream of progress.Footnote 47

In order to delve deeper into the roots of this controversy, the meaning of ‘progress’ here is worth probing, as well as why Ramlee was deemed to be ‘hindering progress’ by departing for Hong Kong. Interestingly, this has to be understood in relation to another aspect that was mentioned in the article—who Ramlee was before. This can be taken to refer not just to Ramlee's character before becoming MFP's ‘golden boy’, but also to his role in labour activism. Today it is well known that P. Ramlee wore many hats but least discussed of all is his participation in labour union activism. By the 1950s, labour movements sprang up across Singapore and Malaya.Footnote 48 Those in the film industry found representation in the Malayan Artists Union (Persatuan Artis Malaya; PERSAMA). Established in 1954, PERSAMA's main goals were to improve the wages of its members and act as a representative for negotiations between employers and employees.Footnote 49 Interestingly, the influential P. Ramlee was the very first President of PERSAMA. He was aided at that time by fellow film directors Salleh Ghani and Jamil Sulong.Footnote 50

The strength of PERSAMA cannot be understated. By February 1957, PERSAMA was organised enough to demand an increase in MFP wages and a new structure for contracts (the existing ones were deemed to be exploitative). However, with an opponent as powerful as the Shaws, the fight was tough to say the least. In response to these demands, on 3 March 1957 the Shaw Brothers chose instead to fire three PERSAMA members from the MFP: Musalmah, Omar Rojik and H.M. Rohaizad. When the protest continued, two of the most vocal agitators, S. Kadarisman and Syed Hassan Safi, both assistant directors at MFP, were also fired on 5 March 1957. A strike consequently broke out on 16 March 1957. Over 120 MFP employees picketed the front of the Jalan Ampas studio. Film stars were also seen picketing Queens Cinema in Geylang, where MFP films were being shown, and mass protests occurred at popular gathering places for the Malay community. Finally, after two days of negotiation, on 7 April 1957 the strike was officially resolved. Nevertheless, resentment over labour issues lingered and over the next few years numerous strikes, work disruptions and protests still took place at the MFP. Protests carried on into the 1960s, with another major strike occurring in the MFP studio in 1964.Footnote 51

Understanding Ramlee's involvement in PERSAMA further sheds light on why his proposal, marketed by Ramlee himself and the Shaws as a progressive leap forward, did not gain widespread support. The idea was met with severe criticism from MFP workers because many of them felt that this would divide the unity of PERSAMA at a crucial time. Given P. Ramlee's influence, to have him leave the country at this time, bringing with him a sizeable group of Malay film workers, would weaken the strength of these movements and threaten the union's solidarity. This was even more pertinent in the early 1960s, as the union was experiencing an internal split between those who represented the artistes and those who stood for workers toiling behind the scenes.Footnote 52 Union members were also concerned that, if Seniwati succeeded, more MFP manpower and resources would be sent to Hong Kong in future. By then, the union would have even less grounds to fight for their rights.Footnote 53

Indeed, the third president of PERSAMA himself—actor Jins Shamsuddin—reportedly led union objections against Ramlee's Hong Kong endeavour, and ‘a fierce battle between the union and P. Ramlee’ ensued.Footnote 54 Under the leadership of Jins Shamsuddin, by the 1960s a group of MFP employees had become affiliated with the Singapore Association of Trade Unions (SATU), which was considered to be more aggressive. They disagreed with PERSAMA's old tactics, which they perceived as too accommodating.Footnote 55 This turn towards more confrontational strategies by the mid-1960s anticipated PERSAMA's vehement protests against Ramlee's proposal. Afterall, Ramlee's proposal was one that would, as mentioned, lead to continuity rather than rupture of the old studio system. Such a future conceivably did not sit well with an increasingly uncompromising PERSAMA.

The union's protests also took a personal turn. Within the industry, some were even alleging that, by leaving for Hong Kong, P. Ramlee in fact wanted to fragment the association. They saw this as a conspiracy between the star and the Shaws, whom they felt were building their Hong Kong studio ‘on the sweat, blood and tears of their employees in MFP’, with profits made from MFP labour going to fund the Hong Kong studio.Footnote 56 This might not be an entirely unfounded accusation considering how the SB(HK) studio was undeniably the stronghold of the Shaws’ cinematic empire. As mentioned, by the 1960s the Shaws made explicit their ambition to further develop their Hong Kong film studio into one of the best in the world. In contrast, their MFP studio stagnated in terms of technology and infrastructure. Business-wise, the sociopolitical situation in Hong Kong at the time was less volatile than in Singapore and Malaysia. Thus, Chinese-language films enjoyed a wider and comparatively more stable distribution and exhibition network than their Malay counterparts. Labour costs were also cheaper in Hong Kong then.Footnote 57 In fact, Run Run Shaw himself had said in an interview in 1967, that the reason why the SB(HK) studio could churn out movies at such a rapid speed was precisely because ‘we have no unions here, you know, and we work longer hours’.Footnote 58 The film magnate also relocated to Hong Kong in 1957 to oversee the family's film business in the city. It was thus reasonable for PERSAMA members to suspect that the Shaws’ true intention was to circumvent the difficult union problems they were experiencing in Singapore, and to subsequently empty out MFP resources to their Hong Kong headquarters. Moreover, Ramlee's good relationship with the Shaws was already a source of contention amongst MFP employees to begin with. In this light, by planning to leave for Hong Kong at this crucial time, P. Ramlee was effectively seen as sabotaging the progress of the labour movement and his comrades, betraying his own efforts and credibility as a supporter of PERSAMA. In the eyes of his fellow comrades, by leaving the ongoing struggle for Hong Kong, P. Ramlee unwittingly turned from being PERSAMA's leading figure to an ally of their exploitative employer.

Most vocal among the detractors then was someone named ‘Bintang Kecil’ (Small Star).Footnote 59 On 27 July 1963, Bintang Kecil published a long letter entitled, ‘The tragedy of Malay films in the homeland: The progress of P. Ramlee as a reminder to the management’, in Berita Harian. In this strongly worded letter, Bintang Kecil expressed doubt over the purpose and intent of P. Ramlee moving to Hong Kong. Challenging Ramlee's claims, the author argued that the proposal was made more in the interest of SB(HK) and P. Ramlee's personal benefit than the future of Malay cinema.Footnote 60

Four key objections were raised in Bintang Kecil's letter. Again, issues of favouritism and labour solidarity came to the fore. What warrants special mention is that the letter clearly demonstrates how the controversy stemmed also from fundamental differences in identifying the principles or ideals that should guide the future of Malay cinema. It shows how labour activists and their sympathisers rejected Ramlee's vision because it seemed to disregard, even reverse, the ideals and demands of their movement. Below I quote Bintang Kecil's key objections at length for they effectively sum up the tone and line of argument propagated by those who rejected the proposal:

1. What is the point of expanding the influence of Malay films and revering artistes if the company is no longer interested, and if our salaries are notoriously known to be still unregulated by the association, receiving the same salary as Chinese ‘amahs’ [housemaids] in the studio? … I am not speaking for Ja'afar [MFP spokesperson] and P. Ramlee because there must be benefits for them.

2. I have received news that P. Ramlee wishes to delve deeper in his knowledge of colour films after knowing that the cameraman for Seniwati is a Japanese man who has won many big awards … He is expected to produce a film using the facilities and equipment that are only available in Hong Kong. However, if it is about learning filming techniques, why is Abu Bakar not being sent? Is it because Abu Bakar has become the best cameraman [in the Malay film industry] such that learning from a renowned Japanese cameraman is not befitting for him? Surely there is more than meets the eye here, it seems.

3. The progress of Malay films from the past till now is without question. In fact, if I am not wrong, the MFP studio was at one point in time the biggest studio in Southeast Asia, as a result of two of the most profitable Malay films, both of which starred P. Ramlee. But, we wish to ask, where exactly is the majority of equipment/setup in that studio now? Is it going to Studio Merdeka in Kuala Lumpur or to Hong Kong? … If Shawscope is not available in Singapore, why not work on it since the MFP already exists and functions similarly? Why was not the technology of colour film shooting, along with other post-processing technologies, brought over to Singapore if indeed there are plans to make more films such as Seniwati?

4. It does not make sense for a Malay story by Malay people to be deliberately made in Hong Kong … I am not convinced that the Malay extras can be replaced with Chinese Muslims, as was once suggested by P. Ramlee, because even though they are Muslims, they also remain Chinese people.Footnote 61

Bintang Kecil's arguments reveal that the potentially groundbreaking aspects of Ramlee's proposal came into direct conflict with the interests of labour activists and their sympathisers. In envisioning how to restructure the existing industry into one that suited the changing times, both sides disagreed on what were the most pressing problems to be addressed. While Ramlee's proposal embodied cosmopolitan aspirations, the third and fourth point in Bintang Kecil's letter hint at an inclination similar to an ethnocentric understanding of independence and decolonisation mentioned above. Those who objected to Ramlee's proposal were not against improving Malay cinema's technical qualities, but held that the means to achieve that should be based in Malaysia and/or Singapore. The future of Malay cinema envisioned by Bintang Kecil and his supporters was one that would remain territorially based within the Malay Archipelago. This territorially bound vision is, importantly, also one that acknowledges Malay cultural superiority and resistance against foreign influence as its foundational principles. Implicit in Bintang Kecil's fourth point is the idea that Malay film production must maintain an essence that is tied to Malay ethnicity. Rejecting the possibility that artificial backdrops and non-Malay cast members could fit into ‘a Malay story’, Malay cinema is here understood as a vehicle for representing and propagating Malay customs and beliefs defined in terms of ethnic and racial purity. Compared to Ramlee's formulation, in spirit this model of Malay cinema was thus much more closely aligned with the aforementioned ethnonationalist discourse championed by UMNO and Malay film activists. In thinking where Malay cinema should be headed amidst new nation-states, defining new local/national boundaries of Malay cinema seemed to be the key concern for Bintang Kecil and his supporters, rather than technical advancements and global recognition.

Labour rights were clearly also a major consideration in conceptualising these boundaries. The letter illustrates that those who rejected Ramlee's proposal were uninterested in transnationalising Malay cinema not because they were against expanding its market, but because they prioritised achieving fairness, solidarity, and autonomy within the local film industry. Echoing the demands of PERSAMA, Bintang Kecil envisioned a Malay cinema that no longer runs on the old exploitative structure—a break rather than continuation of the studio era. To even begin speaking about progress, Malay cinema had to be first and foremost grounded in a renewed system that guaranteed fair wages and working conditions. Seen through Bintang Kecil's perspective, it becomes clear how Ramlee's proposal can be interpreted as problematically perpetuating the old structure rather than revolutionising it, continuing to enable unjust employer–employee relationships rather than changing it (including the purported favouritism that Ramlee himself was receiving). Ramlee's proposed model of transplanting MFP's daily operations to the employer's headquarters in Hong Kong was simply not an acceptable future option for those who were fighting for their labour rights.

Bringing labour and ethnonationalist concerns together in denouncing Ramlee's proposal, Bintang Kecil's letter represents how labour activism shaped Malay cinema's transitional stage in more ways than one. Historians and critics commonly acknowledge that the aforementioned labour strikes throughout the 1950s and 1960s fundamentally destabilised the old studio system. Labour movements accelerated the disintegration of studio structures, opening the way for a new independent/bumiputera era, and the rise of a Malay-centric Malaysian cinema.Footnote 62 Ramlee's abortive Hong Kong project unveils another dimension to the story. Forming the key opposing force against Ramlee's transnational proposal, PERSAMA effectively forestalled Ramlee's alternative vision for Malay cinema from materialising. Although logistical issues may have caused a certain degree of obstruction, it was opposition from within the industry and in the public sphere that posed a greater threat. By sealing the fate of one of the very few alternative pathways at that time, PERSAMA in no small part helped to facilitate the transition of post-studio era Malay cinema into the official ethnonationalist Malaysian cinema as we know it today.

Conclusion

From his three minutes-long cameo appearance in Love Parade, to the proposed making of at least five Malay films in Hong Kong, in the early 1960s P. Ramlee was cast in the middle of a potentially game-changing plan. At a critical juncture in Malay film history, everyone in the industry was contemplating where Malay cinema was heading. Made possible by the intrinsic MFP-SB(HK) connection, P. Ramlee's special position within the Shaws’ orbit, cosmopolitan and global aspirations, Ramlee envisioned through and with the Shaws, the possibility of transnationalising Malay cinema. This was a model of Malay cinema that looked to expand its market and operations outside of the usual Malay Archipelago. It was also one where the old studio system could potentially stand the test of time, using existing infrastructure to tackle market and sociopolitical changes rather than revolutionising it. This early moment of transnational Malay cinema constitutes an alternative response—a proposed solution—to the region's then newly configured national realities.

(Un)fortunately for Ramlee, the overriding tide of ethnonationalism, itself representing mainstream response to the same set of geopolitical changes, was not to be stopped. Ramlee's Hong Kong endeavour ultimately failed to materialise. This article has shown how the star's role in labour activism played a major part in this. His departure at such a critical juncture was seen as hindering the progress of labour movements and development of an independent, decolonised Malay(sian) cinema. The ideals that Ramlee's Hong Kong endeavour embodied also stood in stark contrast to those of labour activists. Technical advancements and transnational expansion were not nearly as important nor urgent as achieving fairness, solidarity, and autonomy—here understood primarily in ethnocentric terms—within the local film industry. Being a key member of PERSAMA, these were voices that Ramlee could not simply turn a deaf ear to.

Albeit short-lived, this interesting episode provides us with valuable resources to rethink Malay cinema's post-studio era transformation and roots of Malaysian national cinema. In the context of Malay and Malaysian film histories, Ramlee's Hong Kong endeavour represents an uncharacteristic attempt to chart an alternative future trajectory for Malay cinema. It demonstrates that, as opposed to the seemingly inevitable nationalisation route, in the early 1960s a transnational model of Malay cinema also came up as a potential future that the industry could aspire towards. It challenges the overwhelming emphasis that existing film history narratives place on localisation and nationalisation, revealing that a contrasting alternative was tested and trialled at this crucial stage in history. In trying to understand the transitional period, contestations between transnational and local/national ideals must thus also be considered. At the same time, this episode reveals that the role played by labour union activism in shaping this transitional stage is also more complex than previously recorded.

This study has also brought together, in new ways, the histories of Hong Kong, Malay and Malaysian cinemas. Even in studies of the Shaws’ massive transnational enterprise, all too often Hong Kong and Malay(sian) film industries are thought of as distinctively separate entities. On the one hand, scholars who specialise in Hong Kong cinema tend to focus on Chinese-language cinemas and neglect the Shaws’ Malay film enterprise altogether. On the other hand, scholars of Malay cinema tend to relegate the Shaws’ and Hong Kong's involvement entirely to the studio era, particularly its early years. Ramlee's Hong Kong endeavour is evidence that these histories are in fact more intrinsically linked, impacting Malaysian cinema's formative years and Hong Kong cinema's prosperous heyday.

This article opened with an outline of how prevailing narratives tend to valorise Ramlee as an embodiment of localism and nationalism. An understanding of Ramlee's Hong Kong endeavour interrupts such hypernationalist characterisation. Although revered as an (ethno)nationalist icon today, Ramlee had in fact pushed for a transnational model of Malay cinema at a time of independence and decolonisation. Furthermore, his contestation with PERSAMA illuminates the complexity—indeed, irony—of Ramlee's role in this crucial period. From Love Parade to Seniwati, the Shaws favoured Ramlee to spearhead the project. Yet, it was precisely Ramlee's participation that also complicated the process. His conflicting identity as the Shaws’ favourite ‘golden boy’ and as one of the most prominent figures in the PERSAMA movement made it virtually impossible for him to execute the plan. This historical plot introduces complexity to the usual linear narrative of Ramlee going from being a ‘golden boy’ to someone who had fallen from grace, having been left behind by the changing times.

Lastly, revisiting this episode prompts us to contemplate what could have been. It leads us to consider and imagine how the course of P. Ramlee's career and Malay(sian) cinema would have progressed differently, had this alternative route been taken. With the proposal proving to be extremely unpopular with his comrades, Ramlee eventually abandoned the idea. As is well known, instead of Hong Kong P. Ramlee settled at the Merdeka Studio in Hulu Kelang, Malaysia, where his once-illustrious film career came to an unfortunate end.Footnote 63 In 1964, many were already asking if P. Ramlee abruptly relocated to Merdeka Studio only because his plans to make films in Hong Kong had failed.Footnote 64 This reminds us that, besides oft-cited reasons such as the fall of MFP, the separation of Malaysia from Singapore and the rise of a new youth-centred pop culture, the failure to materialise this transnational alternative also indirectly led to Ramlee's downfall. In the interest of critical reflection, it is worthwhile considering: If he had indeed left for Hong Kong, would Ramlee's illustrious film career not have ended prematurely as it did in reality? Would Malay(sian) cinema correspondingly have been able to transcend ethnonationalist limitations at this crucial transitional stage, and how would that have played out?

Taking this further, it is also worth reflecting: If transnationalising Malay cinema meant producing the likes of Japanese and Hong Kong films, would Malay films indeed have been able to reach a wider audience globally? How might the problems that would allegedly plague a transnational Malay cinema, particularly one that continued to rely on the Shaws’ resources and network, have been circumvented? Ramlee's Hong Kong endeavour provides a useful base from which a critique of the present situation can be launched. It is also helpful for assessing the future of Malay and Malaysian cultural production. All in all, this article has taken a serious look at an episode that is usually relegated to the margins of history. It complicates and reinterprets the nation-centrism surrounding grand P. Ramlee narratives. It also argues for the importance of this early moment of transnationalism, in understanding the development of post-studio era Malay cinema, beginnings of Malaysian national cinema, as well as their projected futures.