For about a year, Kansas was swept up in a kind of controversy that had not been seen in the state since the full bloom of the Farmers’ Alliance and the People's Party in the 1890s. It was a fight between petroleum producers and the Standard Oil trust that prompted William Allen White to offer this characteristically tart assessment of his neighbors: “It is funny—how we have all found the octopus—an animal whose very existence we denied ten or a dozen years ago.” The question White put to readers of his Emporia Gazette was whether the “octopus has just hatched out” or were “the old line Populists who put sand-burs on his tail, and tied cans to it, smarter and further seeing and more frank and honest than we were?”Footnote 1 The Kansas Oil Producers Association, organized by Republican businessmen, rebuffed the accusation made in various quarters that they were “going into Populism.” In a letter and broadsheet that widely circulated the state in early 1905, the group made their appeal on behalf of the “plain everyday people,” the ones who worked, saved, and invested.Footnote 2 They were not radicals, they insisted, and did not want to abolish Standard Oil. They wanted, as the governor said, to take the trust by the neck and compel it to be decent.Footnote 3

The Kansas oil war, so-called by the muckraking press, was a fight over the political economy of the state's petroleum industry. The details of the conflict were straightforward. There was competition in the extraction business, but when it came to railroad and pipeline distribution, as well as refining and consumer marketing, the local Standard Oil Company was the only name in town. In response to sudden downward pressure in 1904 on commodities prices that they believed Standard Oil had directly caused, producers organized and turned to state power for a “square deal.” The oil producers cast their plight in rhetoric and policy ideas that were well-known to Kansans who had watched the Populists. The battlegrounds of the oil war were monopoly, railroad rebates, common carriers, price discrimination, and the role of the state in protecting a democratic economy.

The events of 1904 and 1905 contribute to our historical understanding of the legacy of Populism as well as the development of corporate capitalism in the early twentieth century.Footnote 4 The way the oil producers, for one, thought about political economy shows the persistence of Populist sensibilities albeit in an industrial sector and among businessmen. Rhetoric and ideas tend to move and take root in new social groups over time.Footnote 5 What may seem more unlikely, however, is that those who waged the Kansas oil war were not opposed to corporate capitalism. They articulated instead a positive vision of corporations that ran counter to the anticompetitive scourge of mergers and monopolies. A corporate economy that was transparent, competitive and, above all, fair—this was the normative vision. These petroleum populists, furthermore, made significant and concrete contributions to the Progressive Era's project of economic reform. Their agitation resulted not only in broad legislative changes in railroad law, but also directly contributed to federal investigations that led to the 1911 Supreme Court decision to break up the Standard Oil trust. That decision, as Martin Sklar classically argued, reestablished the common-law distinction between good and bad combinations and restored the so-called rule of reason, thereby signaling the legal and cultural victory of corporate capitalism over proprietary capitalism.Footnote 6 The emergence and legitimation of this corporate economy depended, Sklar said, on the interrelation of diverse social movements and economic sectors.Footnote 7 These Kansas reformers stand revealed here as one of the bottom-up sources of the corporate reconstruction of American capitalism that are often overlooked.

The Kansas oil war challenges older assumptions and poses important questions about the significance of the Agrarian Revolt. Populism, in many scholarly portrayals, belonged to the past. It was a living anachronism tucked within the evolutionary layers of the American frontier that survived past its time. So said Frederick Jackson Turner in his 1893 essay on the historical significance of the frontier.Footnote 8 In their turn, many historians in the first decades of the twentieth century disagreed and found a premise for their progressive politics in the Populist Revolt, but that first Turnerian assessment had a staying power.Footnote 9 In the heady decade of religious revival and McCarthyism after World War II, Populism struck many postwar intellectuals as a font of American backwardness and authoritarianism. They did not call it primitive like Turner had, but they did see in it a multitude of sins—racial animus, undemocratic intolerance, and irrationality.Footnote 10 This interpretive yoke laid upon the agrarian movement primarily by Richard Hofstadter set the terms by which historians would recapitulate or, more often, revise the record for much of the twentieth century.Footnote 11

In the past generation or so, however, Populism has been set free from restrictive dichotomies that had cast the movement as either progressive or close minded.Footnote 12 Charles Postel's The Populist Vision, as perhaps the most prominent example, represented not only original research into western Populists but also signaled, as a winner of the prestigious Bancroft Prize, a shift in perspective among American historians.Footnote 13 Postel reflected the new consensus by portraying Populism as a mass social and political movement that was multifarious and contradictory when it came to issues of race and gender but that was nevertheless characteristically modern, driven by legible business interests, and supportive of a democratic vision of the corporate economy. No historical narrative is likely to present itself anytime soon that will be as totalizing (and perhaps enjoyable) as the interpretations of Richard Hofstadter or of his chief critic, Lawrence Goodwyn. Instead scholars have eagerly turned their attention to more particular projects like biographical, local and regional narratives, women and African Americans in the movement, the role of religion, and the history of capitalism.Footnote 14 Alongside of and, in some cases, co-productive of this historiographical scattering, scholars and journalists have written about modern political movements, socially distinct from the agrarian radicals and operating on either pole of the political spectrum, which have also come to be called populist.Footnote 15 Our contemporary historical understanding of the meaning of the Populist Revolt and the relationship between Populism and subsequent populisms, then, is more contested now than it has ever been.

One consequence of this loosening of historiography is that scholars have looked beyond the electoral failure of the People's Party in 1896 to see more carefully what became of the Populists and their ideas. We know a lot more about how the activism of the agrarian radicals did not simply disappear but moved into new political configurations and remained a vital source for progressive reform at the congressional level in the first decades of the twentieth century.Footnote 16 We also know more about the persistence of their rhetoric, ideas, and sensibilities.Footnote 17 Most recently, for example, the legal scholar K. Sabeel Rahman has made the persuasive case that from Populists in the early 1890s to Brandeisian Progressives in the 1910s, there is a discernable tradition of democratic agency shaping regulatory institutions, civil society associations, and political practices that made possible collective action.Footnote 18 This scholarship suggests that there is more of a story to be found in the traces of 1896 than previous generations had tended to assume.

Beginning in 1904 and gaining national attention in 1905, the Kansas oil war is a case study for the curious persistence of Populism. Before anything like a coherent and developed ideology of Rooseveltian progressivism had emerged, the Kansas conflict unfolded in the early years of America's first progressive presidency at a time when Republican reformism was ascendant. Faced with unequal market conditions and acute economic loss, oil producers made use of certain modes of rhetoric and political economic ideas that were both at hand and recognizable to a nation with a new appetite for muckraking. In a moment of transition in national and state politics, long before the fullness of progressivism would be made clear, oil producers found resources in a political tradition that had so recently riled the Sunflower State. Their story suggests that, when looked at through a wider historical perspective, Populism's relation to corporate capitalism was neither tragic opposition nor unfortunate capitulation but rather a dynamic and persistent force that sought to bring democratic ideals to bear on American economic institutions.

***

The small business revolt against Standard Oil was a political economic protest embedded in scientific, technological, and institutional structures. Its larger industrial context was the upheaval in the American petroleum industry at the turn of the twentieth century. Large quantities of crude oil were found in Texas in 1901 and subsequently in several more states in the American Southwest. These discoveries offered opportunities for new producers and markets in an industry that was previously limited by geographical and institutional concentration. In the late nineteenth century, there had been two main oil fields and those were in the Northeast—the Appalachian originally and then the Lima-Indiana—but suddenly there were three more and they were big: the Gulf, California, and Mid-Continent fields. Where the industry had been organized infamously by Standard Oil companies, now there were hundreds of mid-size and small producers.Footnote 19 Production increased overall by 330 percent in the first decade of the twentieth century.Footnote 20 By decade's end, the new southwestern fields produced 65 percent of American petroleum.Footnote 21

The petroleum industry was entering a period of disruption that would last for decades. As Daniel Yergin puts it, the Old House of Standard Oil “saw its control over crude oil production in the United States—and its ability to ‘establish’ prices—slipping away.” Or as Alfred Chandler argued, it was the opening up of new supplies and markets and the use of new technology that contributed to the dynamism of the period. Long before the Supreme Court broke up Standard in 1911, its monopolistic grip was pried open and oligopolistic competitors like the Texas Company and Gulf Oil came in.Footnote 22 The attribution of industry expansion to market factors tells one part of the story, to be sure. But scholarship has tended to focus too narrowly on liberal notions of how markets supposedly acted and not enough on how markets were created. Politics, including a vibrant populist tradition in the Southwest, contributed to the structure of oil markets at the state level.Footnote 23

Standard Oil was not in the business of producing oil in significant amounts in the Mid-Continent field. By the early 1900s, the company's investments in portions of southeast Kansas and northeast Indian Territory were largely in distribution, refining, and wholesale and retail sales of products like paraffin; illuminating oils; and, as time went on, also fuel oils. As with other monopolistic institutions like the American Tobacco Company, this model of offloading the risk of fluctuating commodities prices to small and mid-size producers proved to be an important source for market power.Footnote 24

Petroleum was on its way to becoming one of the twentieth century's most characteristically global commodities. There were production and refining centers in multiple regions in the United States and also in Ontario, Canada, Romania, and the Baku region of the Russian Empire. As political scientist Timothy Mitchell has argued, the materiality of petroleum—its light weight and liquidity—made it particularly fit, more than other energy commodities like coal, for international shipping.Footnote 25 By 1905, regular routes out of the Northeast and Gulf Coast brought oil to London and Europe. Global oil markets influenced the price of domestic crude, but their reach was buffered by the spatial barriers of distribution networks.Footnote 26 The Lima-Indiana and Appalachian fields of the northeastern United States as well as the Gulf Coast fields of the Southwest, on the one hand, due to their proximity to Atlantic shipping routes, were especially suited to join the global petroleum market. The Mid-Continent field, on the other hand, was by comparison landlocked, which would prove significant for the spatial politics of the industry. Early producers in Kansas shipped their barrels by way of railroad either to Standard's refinery in Whiting, Indiana, or to the East via St. Louis. The company invested heavily in a pipeline network and two refineries in the region.Footnote 27

By the turn of 1904, Kansas had gone through an oil boom and was on its way toward an oil bust. Producers, investors, and speculators flooded the field, precipitating high production levels and a decrease in prices. The price in 1903 came to a high of $1.37 per barrel, a profitable rate by many standards.Footnote 28 But by April of the next year, the average price was falling from $1.17. In subsequent months, the price of high-grade oil had declined to eighty-four cents and it would go more than thirty cents lower in 1905 to a trough of about fifty cents per barrel.Footnote 29

There were two ways of looking at this. Some critics claimed that the producers had brought these market conditions upon themselves by overproduction. “They all had a personal interest in attempting … [to] make 30-cent oil worth $2, and not one of them had the remotest conception of the petroleum industry,” one Pennsylvania trade journalist with ties to Standard wrote. The producers, in other words, simply should have known better.Footnote 30 Other large producers agreed, and, for them, the failure of small operators offered the consolation of a consolidated (and more predictable) market.Footnote 31 But other vocal producers and their allies argued that Standard was manipulating the market and driving them out of business. They were, so they said, victims of a company that had the power to unilaterally lower the commodity price and reap a reward in the consumer market. While U.S. oil prices did decline nationwide by 34 percent between 1903 and 1905, the price decline in Kansas was far more rapid and significant—about twice the national average.Footnote 32 It is impossible to know for sure how Standard Oil managers made their decisions about prices, but one thing for certain is that, having constructed an infrastructure of monopoly that insulated the firm from all competition, there was little reason for the public to have confidence in the legitimacy or fairness of collapsing oil prices.

The Kansas producers blamed Standard Oil for directly contributing to the boom and bust cycle of the field. The firm had been a booster for Kansas. The company publicized the field, making regular announcements of average daily yields, keeping prices high, and luring more and more producers into the field. The boom and then the bust, so the argument went, was no accident.Footnote 33 Beginning in 1902, Prairie Oil and Gas Company, the local member of the Standard Oil trust, talked publicly of Kansas's potential. They laid pipelines, built storage tanks, and established a refinery in the boomtown of Neodesha. There was even gossip of another refinery in nearby Chanute. “The possibilities of the Refinery will be a matter entirely for the development of the field,” W.J. Young, the firm's president, wrote in a letter printed on the front page of a local newspaper. If the refinery be built and the oil quality remain the same, he said, “there is hardly any question but that the prices for the oil would be the same.”Footnote 34

Potential oil producers had reasons to accept Young's word. Things were looking up in 1902 and 1903. As some recalled, Standard Oil spoke of the necessity of development because of the depletion of other fields in Louisiana and Texas and the subsequent scarcity of crude oil. As a result, “Kansas farmers and oil men through all parts of the country rushed into the oil business.”Footnote 35 But after the price slump, they remembered the boosterism in this way: “At the high tide of this prosperity, encouraged and stimulated by the Standard Oil Company, this great corporation, in harmony with its tactics elsewhere, commenced a systematic absorption of this vast wealth, which threatens to bankrupt these countless private investors and to depreciate and destroy the honest efforts of all the people for the upbuilding of that part of the state.”Footnote 36

Faced with combination from Standard, producers turned to cooperation. Several cooperatives were founded in 1904 for the purposes of collective bargaining and legislative lobbying. The National Oil Men's Association was one.Footnote 37 By April 1904, producers in the oil town of Chanute organized their own association also for the purposes of furthering business interests, but they had more overtly political goals: to “secure justice” in legislative matters like taxation, safety, and the general welfare of the booming field.Footnote 38 The Chanute Oil Producers’ Association, another similar cooperative, functioned as an intermediary between producers and Standard. In May 1904, for example, the association was in negotiations with Standard officials about the establishment of a purchasing agency in Chanute.Footnote 39 This association would become the center of reform agitation over the next year. It was, as one reformer put it, strong and aggressive.Footnote 40

The reform impulse within the young industry coincided with a shake-up in the dominant state Republican Party. Under the banner of anti-bossism and anti-corruption politics, new factional leaders attacked the long-held power of establishment figures and sailed into key positions in the party and in high levels of government.Footnote 41 The early years of the 1900s had been wracked by personal feuds, factional infighting, and multiple public scandals, but a turning point came in 1904 when the controversial sitting governor, Willis Bailey, declined under pressure to run for the party's nomination. His challengers were reform-minded progressives like Edward Hoch, who would be elected governor that year, and Walter Stubbs, who became speaker of the state house. “By early 1904,” one Kansas historian has written, “these men had become independent of all factions and seemed to be genuinely interested in change.”Footnote 42

Hoch was a transitional figure. He represented a style of politics that had not yet settled into a coherent and conventional progressivism, but which had moved on from the heated feuds between the GOP and the People's Party.Footnote 43 The long-time editor and owner of the Marion Record, Hoch had been a legislator and a staunch opponent of the Populists in the 1890s. By the high point of his political career, however, he had come to embrace a politics that was not wholly Populist, to be sure, but neither was it the sedate Kansas progressivism that would come later, what one historian has called “conservative” in outlook, “somewhat simplistic, and certainly not revolutionary.”Footnote 44 Railroad executives, for example, worried about what a Hoch administration would bring. He is “antagonistic,” one said. His nomination “will bring about a worse condition of affairs than during the Populist legislature of 1897.”Footnote 45

At the convention in March 1904, Republicans adopted a wide range of proposals, including antitrust, anti-corruption, and strong railroad commission policies, but at the forefront of the agenda was the oil industry. “That the marvelous development of the oil, gas and other resources of this state is not only a source of pride to every citizen,” the plank read, “but also involves new obligations of government, and we promise to give to these new questions such attention as their importance demands.”Footnote 46 Hoch positioned himself as a follower of Theodore Roosevelt, whom he said was the inspiration for reform across the country—the “Rough Rider over wrong who sits in the White House.”Footnote 47 After his election, Hoch delivered a message to the state House and Senate introducing his key legislative goals for the session. This document was widely reproduced in the press, becoming a cornerstone for the reform agenda of oil producers. “Monopoly threatens to rob our people of the chief benefits of this great endowment and appropriate the profits to itself,” he wrote. “How to save this wealth to the state and to its people, and secure them from its greatest benefits, is a serious problem.” He offered several legislative proposals, including an investigation into price discrimination.Footnote 48

Producers organized to support these measures. William Connelley, an independent oil owner and investor, known in later years as a writer and for his scholarly contributions to Kansas and Native American history, became the secretary for the most prominent of these organizations and wrote most of its public material. As he remembered later, it was the newly elected Hoch who “gave official expression” to this widespread feeling that some solution to the producers’ plight could be found.Footnote 49 Days after Hoch's message, Connelley and other Chanute producers agreed to form a representative body that could lobby the governor and legislature.Footnote 50 Connelley drafted a statement on behalf of the group calling for a statewide meeting within a week in Topeka.Footnote 51 At the subsequent January 19 meeting, they formed the permanent Kansas Oil Producers’ Association (KOPA) and adopted several resolutions calling for the enactment of reform legislation.Footnote 52

In response to this political organizing, Standard Oil made the kind of unforced error that had often characterized the trust's responses to public criticism at the turn of the century. Prairie Oil and Gas Company decided to boycott Kansas oil producers. A telegram from W.J. Young, the president, stated that “on account of the present agitation in regard to our business in Kansas,” he was directing all employees to stop immediately all purchase of new petroleum in Kansas.Footnote 53 The stoppage went on for weeks and generated a cottage industry of controversy both inside and outside the state. Current Literature opined that the “Standard Oil Company itself is responsible for that startling explosion of popular protest against its methods which, for the time being at least, has augmented and unified a powerful ‘radical’ element throughout the State.”Footnote 54 Hoch, in a message to the legislature, said the company was “petulantly and arbitrarily withdrawing its patronage from the producers in the oil-fields.” The threat of bankruptcy hung over the producers.Footnote 55 Philip Campbell, who represented the southeastern oil-rich district of Kansas, introduced a resolution in the U.S. Congress requesting the Secretary of Commerce and Labor to investigate the causes of the low price of crude oil and the high price of refined oil and to find out whether this was the result of any combination in restraint of trade.Footnote 56 Jumping at the chance to take action against a bad trust, Roosevelt directed James Garfield, the Bureau of Corporations commissioner, to investigate. Roosevelt was eager to associate himself with the oil fight. He called Campbell to the White House the next day and pledged his support.Footnote 57

The boycott strengthened the position of the Kansas Oil Producers’ Association. KOPA held a meeting in the town of Independence in March 1905. In the weeks leading up to what would be the most publicized meeting of the oil war, KOPA sent out over a thousand invitations to fellow associations and clubs, legislators and other elected officials, members of the press and the public.Footnote 58 More than three thousand people attended, including five hundred oil producers—a standing-room only crowd.Footnote 59 Among other supporters of the cause, Edward Hoch, muckraking journalist Ida Tarbell, and Phillip Campbell addressed the assembly. The stage of the auditorium was decorated with flags. Behind the podium hung banners of urgent sentiment. “So The People May Know,” read one. “An Open Competitive Market,” read another. And the center stage banner displayed a demand that reformers repeated frequently: “A Square Deal.”Footnote 60

A square deal. This was a constant refrain in the language of the producers, in their public handbills as much as in private interviews, and it best sums up the Populist sensibility of their approach to political economy. As one oil producer put it, the price of crude oil should be “established by supply and demand,” but the “supply as well as the demand is absolutely regulated by the Standard Oil Company.”Footnote 61 The politics of their war against the monopoly were deeply embedded in the structures by which that monopoly was established, from extraction to refining. Those structures warrant more attention.

***

The Kansas reformers perceived that power, like oil, flowed through technologies and infrastructures. Where a monopolistic imbalance existed in each step of the industry, between pipelines and packaging, the reform agenda called upon the state to make the market more democratic for producers. In a range of proposals from the creation of a petroleum inspection board and a common carrier pipeline law to the elimination of railroad rate discrimination and the creation of a public oil refinery, the reform agenda consisted of contesting the market power of the Standard Oil Company by appeals to the power of the state. The mobilization of the oil war began with the commoditization process.

Standard priced oil in Kansas and the Indian Territory by means of a geographical line that its critics claimed was arbitrary. In the southeastern part of the state, where drilling was concentrated, the firm offered two prices for oil pumped north or south of a line that ran through the center of Neosho and Wilson counties, down the Elk County line and across the line separating Elk from Chautauqua County (see fig. 1). Oil north of the line pumped from booming towns like Chanute and Humboldt received a lower price than oil south of the line from towns like Independence, Peru, and as far south as Bartlesville in Indian Territory.Footnote 62 Typically “South Neodesha” oil was twenty cents higher than “North Neodesha.”Footnote 63 By 1903, Standard Oil officials would release daily prices for these two commodities.Footnote 64

Figure 1. Map of the North/South Neodesha Line in southeast Kansas.

Markets elsewhere in the country were structured differently. In the Gulf field, on the one hand, where the industry was more oligopolistic, prices were varied and unstable.Footnote 65 Oil was generally priced differently for different pools within the field.Footnote 66 In Pennsylvania, on the other hand, where Standard exercised near-monopolistic control, there was one price for oil. In the Lima-Indiana field, the company scheduled three prices—North Lima and South Lima in Ohio, and one price for Indiana. The difference between North and South Lima was small.Footnote 67 But in Kansas, a crude geographical demarcation assigned two classifications to oil commodities. Officials from Standard's Prairie Oil and Gas Company asserted that oil north of the line was heavier than that found below the line. And, generally speaking, they asserted a relationship between gravity and quality. Lighter, “sweeter” crude made for more valuable products.Footnote 68

Although scientific knowledge became an important tool for the production of price schedules, the legitimacy of that knowledge did not go unquestioned. Producers disputed, first of all, whether there was enough variability in quality within a single, concentrated field to call for such a dramatic division in price, not to mention whether an east-west line was especially accurate. But the relationship between quality and gravity was also in question. As in the case of other commodities at the time such as sugar or tobacco, the oil industry in the early twentieth century faced contests over the construction of measurements and standards of purity. As scholars like Barbara Hahn and David Singerman have argued, the development of scientific standards, far from being a simple process of rationalization or modernization, is always tied up in cultural categories and political economic advantage.Footnote 69 “The more closely that scholars examine the internal workings of the technology and its contextual causes as well as its effects,” Hahn writes, “the less it appears that the physical, natural world explains the solution.”Footnote 70

The great variability in descriptions of the quality of petroleum for refinery production shows how contested the determination of value was. Agents with the Bureau of Corporations, who investigated conditions in the petroleum industry for two years, reported that gravity was only one among several categories used to determine quality at the time. The chief characteristics that indicated petroleum's “serviceability for commercial uses,” they said, were gravity, inflammability, color, and viscosity.Footnote 71 Petroleum's chemical structure as a hydrocarbon meant that refiners and, eventually, sophisticated chemists could produce a long list of products. Take these examples as they were noted by the federal agents at the time. One was a category of lighter fuels known as “crude naphtha,” including gasoline, benzene, and gas naphtha. Illuminating oils included not just water white but also “prime white” and “standard white.” There were also gas oils, fuel oils, paraffin, greases, pitch, coke, roofers’ wax, wax distillate, heavy illuminating oil, and others.Footnote 72 In the end, the Bureau of Corporations concluded that the “number of possible products is so large and each is subject to so wide a range in quality that the refining business is more intricate than is perhaps ordinarily supposed.”Footnote 73 Depending on the refining process, more quantities of a certain product could be produced and less of another, and thus the value of raw crude was subject to a dizzying array of factors. For practical purposes, depending on the end product in mind, each fraction of petroleum was “comparatively homogeneous.” As one oil producer who had his sample analyzed put it, he believed his own company “will get … better results from its own still.”Footnote 74

Standard Oil's price schedule existed in the absence of competition and it was often subject to unexpected and unexplained change. In the midst of a sharp downturn in prices in November 1904, the company restructured its pricing scheme. They exchanged the North/South Neodesha commodities for a graduated list of prices based on their version of the Baumé gravity scale. The scale was inversely related to the gravity of a sample of petroleum. For lighter crude, 32° and above, Standard offered the highest price. For each half degree lower, the price was five cents less. On November 7, 1904, for example, 32° and above was sold for $.87 and 28° was sold for $.47. Producers initially welcomed this seemingly less arbitrary manner of determining prices, but the general result was a further reduction in prices for Kansas oil.Footnote 75

This precisely graded schedule of prices in late 1904 introduced a new actor into the business of Mid-Continent oil production—the gauger. The Prairie Oil and Gas Company sent into the field gaugers, who presided over transactions between the company and producers. These experts from the local refineries tested the petroleum from storage tanks and, depending on that day's prices and the results of the gravity test, gave the producer an offer. In Kansas, unlike other fields in the United States where oil could be more easily transported to large tanks for long-term storage, Standard required that crude be received into its pipelines as its property immediately.Footnote 76

As prices sagged, encounters between producers and gaugers became frequently contentious. Some complained about the inconvenience of arranging a test. Harry Jones, a small-time oil and gas producer from Independence, said that during the winter he was required to steam his oil tanks before the gauger arrived to perform his tests. “This became very aggravating to us,” he explained, “as at times the gauger would promise to be out one day and not come, would then promise to be out the next day and not come, and sometimes would keep that up for four or five days.” Other producers grew frustrated that they couldn't get a gauger to make consistent appointments.Footnote 77

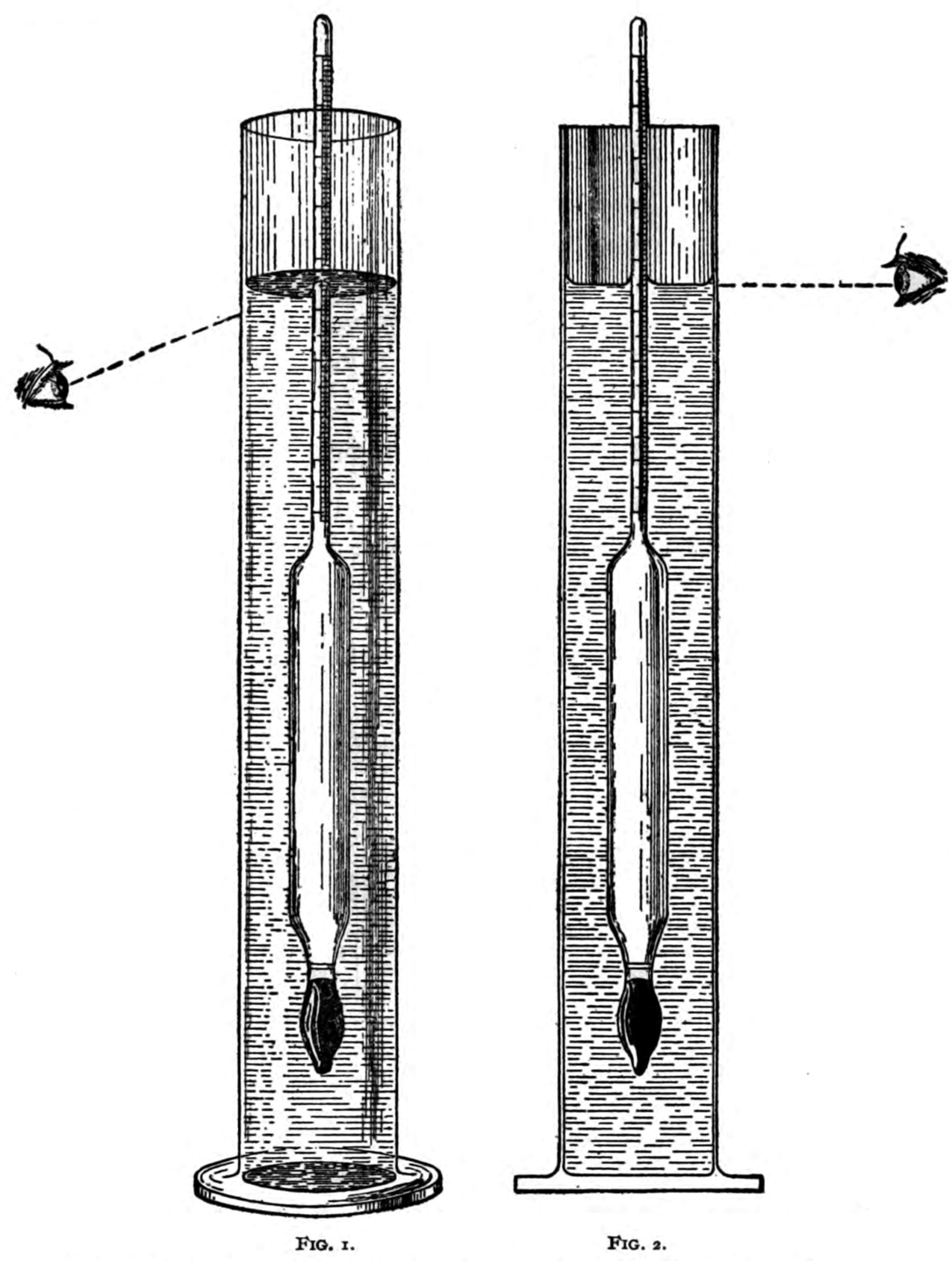

The technology used to perform the test was the most controversial aspect of this new pricing scheme. The test was based on the Baumé scale, developed by Antoine Baumé (1728–1804), a French chemist. His invention, the hydrometer, measured the ratio of the density of a substance with the density of water (see illustration of fig. 2). There has been little to no research done on the use of the scale and hydrometer in the early petroleum industry, though by the turn of the century it seems to have been in regular use, particularly in laboratory settings. Though firms and geologists all claimed to use the Baumé scale, in fact they disagreed over what the scale was, how it should be measured on an instrument, and how those instruments were affected by a range of factors, including, especially temperature. The Bureau of Standards began testing hydrometers in 1904 partly as a result of these disputes in Kansas, but it wasn't until 1924 that the administration published a national standard of petroleum tables that was approved by the industry organization, the American Petroleum Institute.Footnote 78

Figure 2. Illustration of the hydrometer. From U.S. Bureau of Standards, National Standard Petroleum Oil Tables (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1924), 4.

The test could be inconsistent in half a dozen ways at the same time. The Bureau of Standards released a circular in 1911 that provides some context. It gave instructions for the maintenance and use of hydrometers, describing the process by which a substance like petroleum could be measured. The circular noted, first of all, the importance of cleanliness. The container in which the sample was emptied should be clear, smooth glass. The hydrometer itself should be “clean, dry, and at the temperature of the liquid.” The liquid should be thoroughly stirred but the cylinder should be still and without air bubbles at the time the hydrometer is placed in it. The temperature should be 60° Fahrenheit.Footnote 79 In reading the hydrometer scale itself, the quality of eyesight was crucial. The gauger was instructed to bring the surface of the liquid level with the eye and mark the point on the scale.Footnote 80 The number of variables that could affect the result of the gravity test, including temperature, air bubbles, motion, eyesight, and sample quality called the integrity of the hydrometer into question. As the Bureau of Standards put it in 1911, “Hydrometers are seldom used for the greatest accuracy, as the usual conditions under which they are used preclude such special manipulation and exact observation as are necessary to obtain high precision.”Footnote 81

Oil producers, although glad to be rid of the North/South Neodesha distinction, found the variability and unpredictability of the test to be noxious. As one newspaper friendly to the petroleum populists put it, “A well which is producing 30 gravity oil today under the hydrometer test may be declared to be producing 28-degree oil tomorrow. It has been impossible to reconcile the oil men to this.”Footnote 82 Others pointed not at the technology, but the gauger. S.H. Hale, a long-time producer, believed that the gaugers had incentives to take their samples out of the poorest part of the oil tank that included sediment. “The gaugers, of course, are all trying to make a showing for their particular department,” he surmised.Footnote 83 Agents from the Bureau of Corporations interviewed another oil producer and operator, William Haverstick, a former railroad engineer from Neodesha who spoke freely.Footnote 84 He claimed to have drilled a well that produced a light crude, testing at 38°, a measurement that the first gauger who arrived at the lease accepted. The next two Standard Oil gaugers found significantly lower results—the first 33.5°, the second 31°. Haverstick expressed his anger to federal agents. “I tell you this gravity scheme is a damn fraud,” he said. “Whatever they tell the gauger to do, he does it.”Footnote 85

The technology of the hydrometer was in dispute, but there was little disagreement about its effect on the bottom line of the oil extraction business. The introduction of a graded price schedule based on the Baumé scale further consolidated the economic power of the local Standard Oil Company. The firm restructured its market for crude based on a less profitable price schedule. And it sought to shore up the legitimacy of the new price schedule by an appeal to the objectivity of scientific technology. But the legitimacy of science and the integrity of the market were rightly called into question by producers who recognized that both were constructions of politics. One successful owner and investor in the Mid-Continent Field, Camden Bloom, put it this way: “The Standard Oil Company has complete control of the oil industry and regulates the price both on the crude and the refined product.”Footnote 86 The monopoly possessed, it seemed, an impenetrable wall of protection.

KOPA turned to the state for relief. Representing initially the interests of hundreds of small producers and nearly one hundred oil and gas firms, the political association became the most prolific and well-known voice for the petroleum populists.Footnote 87 At the organization's meeting in January 1905, William Connelley, a businessman new to the oil industry, drafted a series of resolutions that would make up the reform agenda of that year's legislative session. Adopted unanimously by those present, one resolution called for the creation of a board of inspection that, in addition to taking proper action in the case of abandoned or dangerous oil and gas wells, would also be responsible for “the inspection and proper grading of the crude oil produced in the state.” The proposed commission would offer producers a line of appeal in the case of a dispute with a Standard Oil purchaser over the gravity of an oil sample.Footnote 88 The proposal, however, never made it out of committee. Connelley later asserted that it was lost in the shuffle of a busy legislative session, but it is more likely that industrial interests who opposed state oversight helped to kill the bill.Footnote 89

The lynchpin of monopoly was the networks of distribution. Prairie Oil and Gas Company controlled the pipeline system. As a map of the territorial distribution of refineries shows (see fig. 3), the company pumped its crude oil to the Sugar Creek refinery, just northeast of Kansas City, and to the Neodesha refinery, in southeast Kansas.Footnote 90 Its principal trunk line ran from Sugar Creek, just across the Missouri border, diagonally through the southeastern portion of Kansas, to Neodesha and the booming oil towns, and down into the Indian Territory to the city of Tulsa.Footnote 91 “Much of the larger part of the oil-producing territory of the Mid-Continent field is, however, as yet, not reached by any independent pipe line,” the Bureau of Corporations reported, “and the producers have no option but to sell their oil to the Prairie Oil and Gas Company or store it at heavy expense.”Footnote 92

Figure 3. Principal trunk pipelines in and from the Appalachian, Lima-Indiana, Illinois, and Mid-Continent oil fields. Bureau of Corporations, Report of the Commissioner of Corporations on the Petroleum Industry: Part I, Position of the Standard Oil Company in the Petroleum Industry (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1907), facing page 123.

Although Standard initially relied on railroad tank cars for oil distribution, they raced to establish their own distribution network. The company made contracts with a number of railroads like the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway Company that gave exclusive rights to lay pipelines on the right of way of railroad systems.Footnote 93 The failure to maintain exclusive possession of pipelines had dogged the company in the oil fields of Pennsylvania in previous decades. Unlike in those more competitive petroleum markets, in early 1900s Kansas the company had the resources for significant capital outlays and to satisfy producers with high commodities prices. This private pipeline network gave Standard Oil a great deal of discretion. The company took title to crude oil at the point when it was pumped out of a producer's tanks and into the pipeline. The oil was paid for on any day selected by the owner within two months after the oil was run, which gave the owner some amount of leeway to take advantage of a potential rise in prices. The company also subjected producers to a series of fines depending on the amount of sediment or the temperature of the petroleum.Footnote 94 Most significantly, the dominance of the pipeline network and, as we shall see, the success of local oil refineries left crude producers with few alternatives as commodities purchasers.

Oil producers did possess alternatives to the pipeline system, but not very good ones. The Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe dominated the southeastern part of the state.Footnote 95 Connelley, a prolific polemicist, asserted that “it is generally known” that the Standard Oil Company had shareholder interests in the Santa Fe railroad. Connelley said it was in the amount of $25 million.Footnote 96 In this instance, as in others, while he was given to combative exaggeration, Connelley was also on to something in substance. Private correspondence in the ATSF archives show that Standard did hold through an intermediary nearly 140,000 shares in the company.Footnote 97 Regardless of the financial structure of their relationship, the two companies had a mutually beneficial relationship in the Mid-Continent field.

The principal coordination between the two firms consisted in maintaining market advantages for the new pipeline network. During construction in 1904, producers in southeast Kansas shipped crude by way of railroad to Kansas City and from there to other refineries outside the state. But upon the pipeline's completion in August of that year, shipping rates suddenly went up. In what became one of the major points of contention in the fight with Standard, prompting investigation by federal authorities, the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe increased its shipping rates on crude by 70 percent.Footnote 98 KOPA published shipping rates tables and established the data for a series of rail lines from small towns in the Southeast to the Kansas City hub. “These rates are prohibitive and were made to prevent the shipment of crude oil out of the Kansas oil fields,” Connelley wrote, “and to force the producers to sell their oil to the Standard for any price it might see fit to pay.” Officials from the Bureau of Corporations agreed. In their final report, they argued that Standard's shipments of crude and refined petroleum products nationwide was of such a great volume that the trust was likely able to bring pressure on the railroad to make such advances in rates.Footnote 99

Oil only flows, to put the matter simply, when it has a distribution network to flow through. Far from a property of its materiality, the suitability of oil for easy distribution relies upon both intensive capital outlays in the form of railroad and pipeline networks and upon the political economy of distribution structures.Footnote 100 In this case, oil did not flow freely. Its material properties, on the contrary, required costly coordination between actors and specialized transportation technology. The apparent monopoly of both railroad and pipeline networks presented a dilemma. Either producers had to settle for Prairie Oil and Gas Company's offered prices or begin the long and costly process of constructing alternative distribution systems.

Kansas reformers pursued a third way. They turned to the state in order to change both the accessibility and the economy of distribution. One resolution called for legislation that would make all pipelines common carries for the transportation of oil and regulated by a state authority. In another, KOPA asked the legislature to establish maximum freight rates for both railroads and pipelines.Footnote 101 Seeking to destabilize Standard's control of the distribution network, reformers embraced the policy of common carriers and set maximum rates for distribution and prohibited the granting of rebates. A favored tactic of the agrarian Populists against railroads, the laws passed by the Kansas legislature made these transportation networks publicly available and subject to the public interest.Footnote 102 They also prohibited rate discrimination. That is, any railroad that offered rebates for one oil company but not for another would be subject to a fine and forfeiture of its corporate charter. Although freight rates by railroad would remain higher than pipeline rates, the goal of the price controls was to make independent refining possible in the state, or at least give producers the opportunity to ship petroleum out of state to another refinery.Footnote 103 One supportive legislator argued that these bills would take away from the Standard Oil trust its “great weapon” and put an end to its throttling of competition.Footnote 104

After much negative publicity, the Prairie Oil and Gas Company largely accepted the state-mandated freight rates, but they contested the legality and practicality of the common carrier law. Relitigating conceptions of public interest going back to Munn v. Illinois (1877), company officials argued that since the pipelines were built on the property of railroads and were not laid on land granted by the state, they could not be made subject to common carrier rules. Relying, furthermore, on the use of the hydrometer to determine price schedules, they asserted that the mixing of discrete grades of oil in common carrier pipelines would place too great a burden on the company.Footnote 105 In the years following, there were widespread reports that the company had never “pretended to obey the law” and refused to consider itself a common carrier.Footnote 106

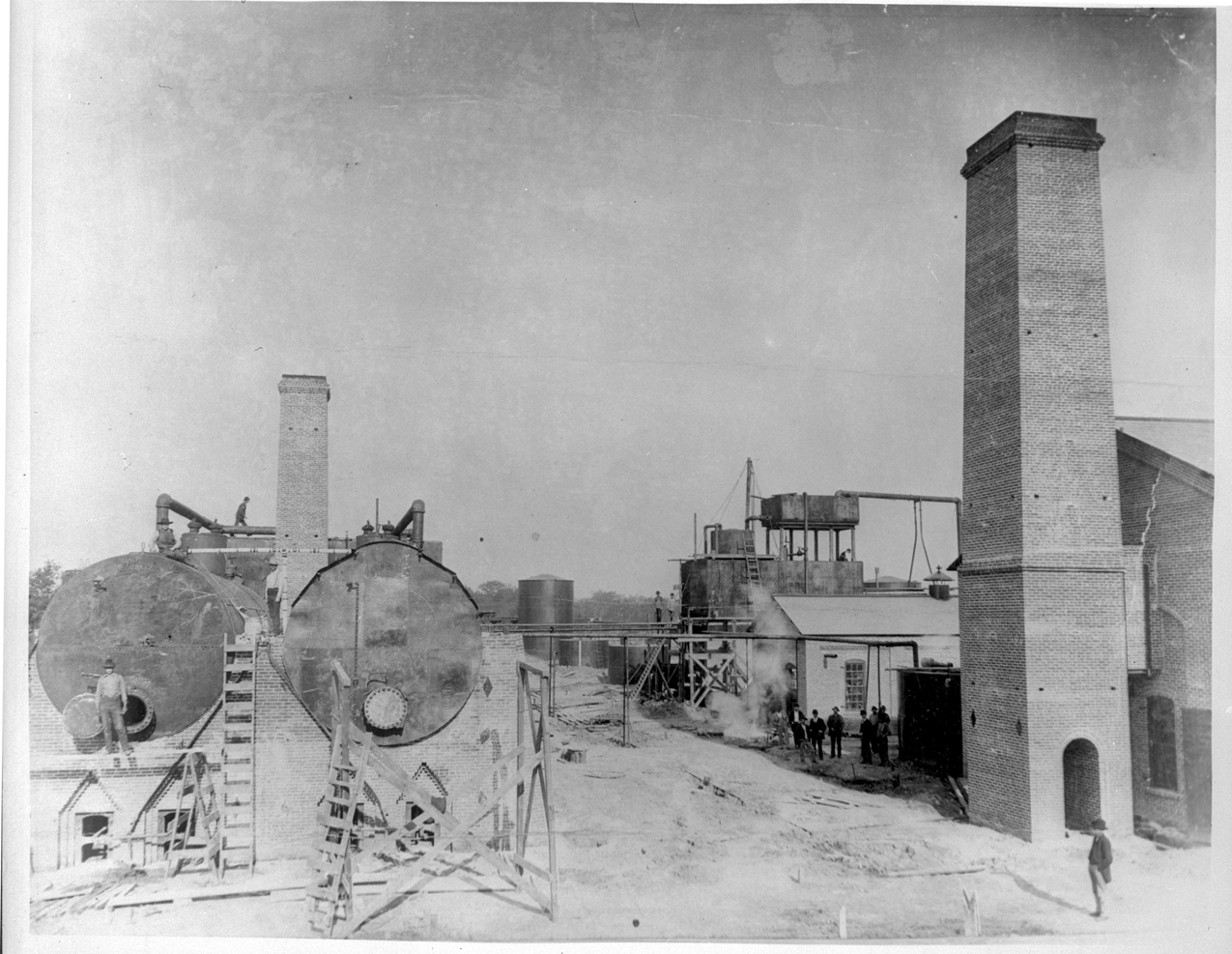

Whether it flowed through pipelines or moved in discrete tanks on rail lines, a refiner eventually distilled crude oil into a variety of consumer and industrial products, primarily illuminating oils. As with distribution, competition was nowhere to be found. By the end of 1904, Prairie Oil and Gas Company refined about 99 percent of the petroleum of that field at their refineries in Sugar Creek, Missouri and Neodesha, Kansas.Footnote 107 (See photo of Neodesha plant in fig. 4.) Independent investors attempted to make inroads into Standard's control over the Mid-Continent field. Over the next two years, more than fifteen independent oil refineries were established in the oil towns of Chanute, Independence, and elsewhere in southeastern Kansas. But the monopolistic distribution system made it difficult for independent refineries. None obtained oil through the Prairie's pipelines. They had access to petroleum by means of their proximity to the sites of extraction or from railroads and short, independent pipelines. Some refiners argued that with more equitable freight rates, they would be able to do competitive business.Footnote 108 Their success was mixed. Most dissolved into bankruptcy in the next few years.Footnote 109

Figure 4. Standard Oil Company refinery in Neodesha, Kansas, between 1897 and 1907. Courtesy of the Kansas State Historical Society.

Petroleum populists staged their opposition also against the firm's proprietary scientific knowledge. The problem, they said, was that this knowledge was private and could not be contested. Each of the refining processes—the distillation of gasoline, kerosene, illuminating oils, and other products—was conducted under the auspices of the personal knowledge of the refinery operator. In the early 1900s, before the emergence of large-scale and professionalized refining operations, petroleum refining was a craft labor.Footnote 110 Each refiner learned particular techniques for producing each product, personally judging the result with reference to color, viscosity, gravity, and temperature, all of which helped him to make decisions about what kind of products he could produce and how long it might take. He determined the original separations and further manipulated products to obtain different qualities.Footnote 111 Such proprietary knowledge in the hands of a monopoly, critics asserted, was undemocratic.

The reformers brought the progressive appetite for publicity to the scientific knowledge of oil refining by seeking to transfer private expertise into the public domain. Among the key policy ideas to emerge in late 1904 and early 1905, it was the proposal for a state oil refinery that generated the greatest amount of attention. The inspiration for the state refinery came from the success of the state twine plant, which was built in 1899 in response to the agitation of Populist farmers against high prices imposed upon them from the twine trust.Footnote 112 Hoch, the reform governor, characterized this government action in private business as nothing more than relief for oil producers and part of an attempt to establish “fair play” in the industry. The relief that Hoch and others envisioned was not direct competition with the Standard Oil monopoly, but experimentation. They regarded the state refinery as an institution that would produce oil products for public sale but—and this was its main purpose—would also release publicly available information on the methods and costs of petroleum refining.Footnote 113

At issue were the costs of refining and the limits of commoditization. What were the capital outlays of a refinery? How variable and extensive were operating costs? And what petroleum products could be made from certain kinds of raw crude? The answers to these questions were unknown to oil producers in Kansas. Hoch intended to settle “definitely and authoritatively” the question as to scientific possibilities and business profits of refining. “These matters are in endless dispute,” he told the state legislature. “No one knows about them except experts and they won't tell.” Or as KOPA put it, “The Standard Oil Company has pursued the policy of absolute secrecy in all its workings, avoiding any exposure of its methods. We believe … that the safety of the people against trusts is publicity.”Footnote 114

The reformers sought to produce open knowledge about the process of refining in order to prove two things. First, Kansas petroleum was as valuable as oil produced in the Lima-Indiana and Appalachian fields. They likewise sought to show that the refining process was relatively inexpensive. They had complained that even as oil prices had declined through 1904 and into 1905, the Standard retail company, Waters-Pierce, raised its price for refined illuminating oils in Kansas. This was just another example of unfair market conditions.Footnote 115

It was an experiment in public utility. The 1905 law placed the operation of the refinery under the jurisdiction of the state warden who was instructed to establish a branch of the prison in Peru, a town located in the middle of the southeastern oil field. With an appropriation of $400,000, the plant would be operated by prisoners and was supposed to give preference to both the consumers and producers of the state.Footnote 116 Although passed with large majorities and supported by the reform-friendly press, the law was quickly struck down by the Kansas Supreme Court, which found that it violated a section of the state constitution that prohibited the state sponsorship of internal improvements. In the years that followed, reformers like Connelley and Hoch insisted, contrary to the court, that it was merely an extension of the law passed by the Populists that used prison labor at a state-run twine factory.Footnote 117

***

The Kansas oil war, in one sense, belongs to a history of failure or roads not taken. As the state legislative session drew to a close and the national appetite for muckraking was sated, the fervor of the moment passed, and it was unclear what the consequences of the oil war might be. For about a decade following 1904, the petroleum industry of Kansas was in a state of decline.Footnote 118 Most of the small-time producers, like Connelley and even the more successful ones, ended up leaving the business. Prairie Oil and Gas Company and a growing number of other large firms turned their business to the booming fields of eastern Indian Territory, soon to be Oklahoma. Hoch and his fellow Republicans took on other Progressive Era concerns like direct primaries, child labor laws, and the graduated income tax.Footnote 119

But, in other ways, the story does not fit into our traditional narratives. It was not, for example, a simple continuation of the politics of Populism. Many of the reformers in state government had either themselves been Republican opponents of the People's Party during the 1890s or their direct heirs.Footnote 120 They were typically middle-class, small business owners, and boosters of local industry.Footnote 121 Their politics emerged at a time when progressivism was dynamic and inchoate and their response to Standard Oil was textured by the politics of Kansas and by traditions of reform.Footnote 122

Some have viewed the Kansas oil war narrowly through the lens of the petroleum industry. As historians Roger Olien and Diana Hinton have explored, local activism directed against Standard Oil and muckraking exposes of the firm originated in late nineteenth-century Pennsylvania.Footnote 123 Such petroleum populism, born out of the opposition of Standard's smaller business competition, expressed for a national audience in the activist journalism of Ida Tarbell and Henry Demarest Lloyd, came to Kansas in the early 1900s and continued to influence other local and national policy making well into the twentieth century.Footnote 124

The events of 1904–1905, however, cannot be understood simply as a part of a national or state progressive movement, nor as a straightforward inheritor of petroleum activism. For one, the progressive politics of the state were still in flux in those years. If anything, the policies that oil producers embraced were far more radical in their tenor than what would pass for Kansas progressivism over the next decade. Nor was it a mere reflection of Theodore Roosevelt and his “trust-busting” swagger. It was the particular context of the oil industry and state politics that produced the movement that latched onto the empowering icon of TR and provided him with an opportunity to score points against a business villain. The editor of the influential Topeka Daily Capital wrote that reformers were proponents of what many in the state were calling “Roosevelt's ‘Populism.’”Footnote 125 This seemingly contradictory phrase is felicitous for capturing overlapping political and rhetorical streams. At the same time, it points to the lasting significance of the Populist Revolt in the decades following the collapse of the People's Party.

The reformers pose a familiar interpretative problem. Can historical subjects who don't explicitly identify with a particular social or political movement still be understood in retrospect to be a part of that movement?Footnote 126 Leaders of KOPA and their friends tended to reject the “Populist” label. That rejection, however, must be understood historically. Where the Populists had mostly identified with the lower or petit-bourgeois classes, Republicans were elites or aspiring elites. Republican leaders had been small-town newspaper editors, many of whom passed a decade accusing the Populists of being watered-down Marxists and un-American renegades.Footnote 127 It is understandable, then, that they were reluctant to embrace the label of a political movement that they had helped to defeat just years before. It is likely, however, that when faced with what they believed to be economic conspiracy, they turned to a collection of policy ideas and rhetorical strategies that were familiar to them precisely because of the Populists.

This battle was framed as a struggle between republicanism on the one hand and tyranny on the other. After the passage of the state refinery bill, journalist Phillip Eastman wrote that Kansas state senators, “feeling the burden of responsibility being lifted from their shoulders, formed a procession and marched through the Representatives’ hall singing ‘John Brown's body lies a-moldering in the grave, but his soul goes marching on!’” Like John Brown's radical opposition to slavery, the spirit of freedom stood firmly against monopoly. Eastman quoted one senator who understood the situation in grandly national terms. “All eyes are on Kansas to see if we waver,” he said. “We are the ones to fire the first gun. This is the Lexington of the conflict, and we must win here.”Footnote 128 Another journalist's account of the scene in the Kansas senate described a closing speech by one senator. “He pointed to the painting of John Brown in the hall,” the Public Opinion article read, “and recalled that at an early day Kansas had started a movement that resulted in ‘human liberty,’ it was left to others in Kansas to start a movement for ‘financial liberty.’ … When he turned to the painting of old John Brown practically every man on the floor of the house sprang to his feet and cheered and cheered again. Up in the gallery it was bedlam let loose.”Footnote 129

Others were tempted to see the reformers as straightforward inheritors of Populism. The journalist William Allen White had been a sardonic critic of the agrarian radicals, but as we saw earlier, he couldn't help but see its lasting influence in the oil reformers. William Jennings Bryan offered support for the producers in his periodical, The Commoner, and argued that what mattered most was not party affiliation: “We are all Republicans, we are all Democrats, we are all Populists, and we are all Independents.”Footnote 130 One of the final Populists left in the legislature, Senator William Lupfer, explained his decision to vote for the state refinery bill, saying that his was a “voice from the dead.” “He told how the Pops used to clamor for state ownership of things,” one newspaper reported, “and how the Republicans ran over them, laughed at them and often abused them. ‘Now,’ he said, ‘I notice that the Republicans are growing whiskers and coming over to our side. Gentlemen, it affords me pleasure to extend to you the right hand of political fellowship.’”Footnote 131 Another remaining Populist legislator touched on similar themes, noting how Republicans used to denounce Populists for their support of state ownership of utilities. He speculated that Republicans were finally beginning to “see the light.”Footnote 132 And the Kansas Agitator remarked with irony how things had changed: “Regulating rates, investigating the trusts, buying a railroad, establishing an oil refinery! Goodness! How … how Populistic—the Republicans are!”Footnote 133

The populist sensibilities of western oil production in general have been noted by some scholars. Perhaps it should come as no surprise that Lawrence Goodwyn, the foremost historiographical champion of the agrarian populists, subsequently wrote Texas Oil, American Dreams, a laudatory account of a movement of independent oil producers from the 1930s to the 1990s. He found in Texas oilmen the anti-monopoly tradition, not only still alive but thriving. They “could never grow weary and could never give up,” he wrote sympathetically, “because they lived in the very center of a universe dominated by giants.”Footnote 134

The significance of the Kansas oil reformers consists not just in the twists and turns of Populism, but also in the story of political economic reform in the early twentieth century. It was Standard Oil's boycott of Kansas petroleum in early 1905 that provoked the U.S. Congress to call for a federal investigation into monopolistic practices in the state.Footnote 135 Roosevelt in turn tapped James Garfield, the new head of the Bureau of Corporations, to launch an investigation, which resulted not only in Garfield visiting Kansas himself but also included a handful of other investigators examining the industry in Kansas, Texas, California, Pennsylvania, and elsewhere.Footnote 136 As a result, the Bureau submitted a report to Congress in May 1906 and published in the following year its findings in three volumes, detailing the prices, profits, refining methods, and distribution systems of the American petroleum industry and, in particular, the position of the Standard Oil trust.Footnote 137 The report demonstrated Standard's monopolistic practices, its abuse of the hydrometer gauge, price discrimination, pipeline dominance, and use of freight discrimination.Footnote 138

The report made a difference in two ways. First it pushed through Congress the Hepburn Act, which dramatically augmented the regulatory powers of the Interstate Commerce Commission over railroads and effectively put to an end the long practice of discriminatory freight deals.Footnote 139 The second was more expansive. The report gave fodder to a legal campaign against Standard Oil. Within a year, seven federal and a handful of state lawsuits were filed against the company for its antitrust practices. These disparate cases concluded with the seminal Supreme Court decision, Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States, which in 1911 broke up the trust into separate firms. Frank Kellogg, the lead prosecutor in the Justice Department, credited the Bureau for providing information, some of which was not included in the final public report, which was instrumental to the development of the case.Footnote 140 William Connelley, then, with justification credited the reform efforts of 1905 for these monumental legal proceedings: “To Kansas belongs the honor of having made the first intelligent and effective crusade against the Standard Oil Company and its criminal operation.”Footnote 141

In helping to transform the intransigent and recklessly monopolistic Standard Oil Company and in forcing the firm to change its behavior, the Kansas oil reformers contributed to the project of corporate liberalism and assisted in laying a foundation for the legitimacy of big business in America.Footnote 142 This was not a wholly unintended consequence. Far from an anti-corporate politics, after all, their goal was to take Standard Oil “by the neck” and compel it to be “decent.” The producers originally sought not to destroy big business, indeed, but to make it an object of ethical and public judgment.Footnote 143

The historical meaning of these events is not straightforward. The Kansas reformers, after all, failed in their efforts to bring prosperity and economic parity to the industry. But their example shows how populist rhetoric and policy ideas continued to exert power in the years following the collapse of the People's Party. “Roosevelt's Populism”—an amalgamation of Populism, early Kansas progressivism, and petroleum muckraking—applied the ideal of a democratic political economy to the material conditions of an industrial market. Their story, in many ways, encourages us to discard well-worn dichotomies between Populism on the one hand and industrialism and corporate capitalism on the other.

The story of the Kansas oil war shows what can be found in unexpected historical places. It confirms that in the pivotal years of progressive economic reform, Americans waged local battles over the structures of corporate capitalism and who gets to benefit from them. In this case, those efforts had political economic consequences that reached beyond the counties of southeast Kansas. But the historiographical implications are also significant. It shows that the corporate transformation of the American economy was a process that is better understood by uncovering bottom-up sources. With limited access to power, the historical actors of this story set into motion social, legal, and political institutions whose eventual effect upon the structures of corporate capitalism can only be seen in retrospect. The mobilization of the state in institutions like the Bureau of Corporations mattered, but it may never have happened without one-on-one conflicts between producers and Standard Oil employees over technologies like the hydrometer. Giving attention to these hitherto passed-over sources pays off not because they reveal in some simplistic fashion that corporate capitalism was a cross-class process devoid of conflicts. On the contrary, the payoff is that we see more clearly how corporate capitalism was no monolith. There were at play rival claims to what the new corporate order should be. And there were winners and losers. The Kansas oil producers, for one, accepted large-scale business organizations but only on terms that were left unrealized—what they imagined as democratic accountability and fair play.

A key element of the turn away from proprietary capitalism, what Martin Sklar identified as a growing “general disenchantment” of small producers at the turn of the century, is revealed in sources that received scant attention from historians of corporate liberalism.Footnote 144 Until relatively recently, as James Livingston has argued, historians who studied mass social movements in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era tended to be attached to narratives of tragedy in which the victory of large-scale industry marked the foreclosure of American democracy.Footnote 145 The history of Kansas oil reformers suggests that a more textured portrait of the contests and construction of corporate capitalism at the turn of the century might be found in social sources that have gone underappreciated.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the Kansas State Historical Society for its generous support through the Alfred M. Landon Historical Research Grant.