Luxembourgish (local language name: Lëtzebuergesch [ˈlətsəbuəjəʃ], French name: Luxembourgeois, German name: Luxemburgisch) is a small West-Germanic language mainly spoken in the multilingual speech community of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, where it is one of the three official languages alongside German and French. Being the first language of most Luxembourgers it also has the status of the national language (since 1984). Although in its origin Luxembourgish has to be considered as a Central Franconian dialect, it is nowadays regarded by the speech community as a language of its own. As a consequence, German is considered a different language. An official orthographical system has been devised. Luxembourgish is used very frequently in day-to-day oral communication at all social levels; it is very common on local radio and television; it is the only language spoken in parliament sessions and it is also very often used at the workplace. Although the vocabulary of Luxembourgish has a substantial number of loan words from French and German, the morpho-syntax follows Germanic patterns. Luxembourgish today has approximately 400,000 speakers, including many L2 speakers (around 43% of the population does not have the Luxembourgish nationality).

Luxembourgish has various regional dialects located in the north, east, south and center of the country (Schmitt Reference Schmitt1963). The phonetic system presented in this article is based on the central Luxembourgish variety, which is seen as the emergent standard language (Gilles Reference Gilles1999, Gilles & Moulin Reference Gilles, Moulin, Deumert and Vandenbussche2003) and which also represents the basis for the orthography and for dictionaries (Newton Reference Newton and Newton2000). Alongside the phonetic transcription, example words are also presented in official orthography.

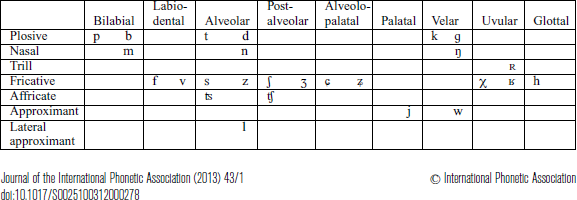

Consonants

With the exception of the alveolo-palatal fricatives and the approximant [w], the consonant inventory of Luxembourgish is quite similar to Standard German.

Similar to Standard German, voiced obstruents cannot occur syllable-finally and will be devoiced (‘Auslautverhärtung’). Likewise, the voiceless plosives [p t k] are aspirated in most positions. The phonologically voiced plosives [b d ɡ] are in fact often realized as devoiced plosives. Thus, the phonological opposition is established by a fortis/lenis distinction. In contrast to German, the glottal stop [ʔ], although observable in some speaking styles, does not form part of the phonological system. [ɡ] is found only word-initially and banned in all other positions, where the successors of historical [ɡ] are realized as fricatives [ɕ ʑ χ ʁ] or have disappeared.

The main variant of /r/ in pre-vocalic position is the trill [ʀ], the lesser used variant is the fricative [ʁ]. Older speakers pronounce [ʀ] or [ʁ] also word-finally (Bir [biːʀ] ‘pear’) whereas younger speakers often show r-vocalization and produce central [ə] or [ɐ] instead ([biːə] for Bir). Between short vowels and consonants /r/ is spirantized, either to a voiced [ʁ] as in Parmesan [ˈpɑʁməzaːn] ‘Parmesan cheese’ or to an unvoiced [χ] as in parken [ˈpɑχkən] ‘to park’. Thus, whether /r/ shows up here as voiced or unvoiced fricative depends on the voicing feature of the following consonant.

Fricatives exist at six places of articulation, all but one having a phonological voicing opposition. Among the fricatives, [χ] and [ɕ] are allophones of one single phoneme /χ/. The same holds for their voiced counterparts [ʁ] and [ʑ] with the latter allophone appearing only in a few words, however. The selection of the allophone is determined, as in German, by the preceding context ([χ ʁ] after phonologically back vowels, [ɕ ʑ] elsewhere). An increasing number of speakers no longer distinguish between the alveolo-palatal and the post-alveolar fricatives, i.e. between [ʃ] and [ɕ] on the one hand and between [ʒ] and [ʑ] on the other. The progression of the sound change may eventually lead to a phoneme merger thus reducing the number of the fricatives.

Frequently, [j] is substituted with [ʒ] (Juni [ˈjuːniː] or [ˈʒuːniː] ‘June’) (Newton Reference Newton, Flood, Salmon, Sayce and Wells1993). The labial-velar approximant [w] has to be regarded as an allophone to the voiced labio-dental fricative /v/ with the former only occurring after [ʃ] (schwammen [ˈʃwɑmən] ‘to swim’), [ʦ] (zwee [ʦweː] ‘two’) and [k] (Quatsch [kwɑtʃ] ‘nonsense’), and [v] occurring elsewhere.

Vowels

The vowel inventory contains the phones [iː i eː e ə ɛː æ aː ɑ ɐ oː o uː u] as monophthongs. In addition, Luxembourgish has a set of eight diphthongs, which is considerably larger than the Standard German one (eight compared to three).

Monophthongs

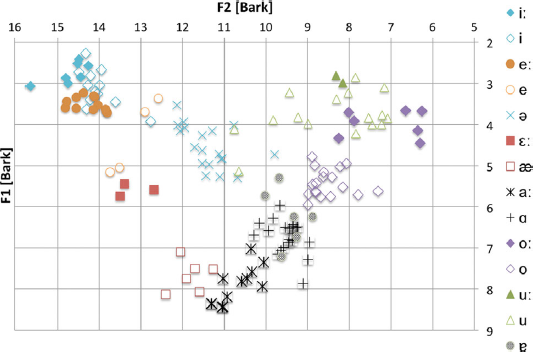

In order to give a better overview of the monophthongs in Luxembourgish, the schematic, auditorily-based system in the vowel chart is accompanied by a formant chart using the Bark scale, which provides a perceptually more realistic acoustic representation of vowel realisations (see Figure 1). Example words for each monophthong follow below.

Figure 1 Formant chart of the monophthongs in Luxembourgish (based on the accompanying sound recordings of this article, younger male speaker from the central Luxembourgish region).

Like most other Germanic languages, Luxembourgish distinguishes short and long vowels. Short [i] and [u] as in vill [fil] ‘many’ and Kuch [kuχ] ‘cake’ mainly differ in length from their long counterparts [iː] and [uː] as in Zil [ʦiːl] ‘goal’ and Tut [tuːt] ‘plastic bag’. As the formant chart in Figure 1 shows, the acoustic difference between these vowel sets is minimal. Short [e] and [o] are also realized rather closed and are thus similar to long [eː] and [oː], respectively. Depending on regional accent and speaker age, more open variants [ɛ] and [ɔ] can be found frequently, especially when followed by the vibrant /r/.

The long front vowels [eː] and [oː] are realized very close and may even show overlap with [i] and [u], respectively. From a phonemic perspective, the vowel /eː/ has two contextually conditioned allophones: when preceded by the vibrant /r/ in simplex words an open [ɛː] is realized (Kär [kɛːə] ‘core’); in all other contexts a closed [eː] (Keess [keːs] ‘cash register’) is realized.

Unlike in German, the schwa sound also appears regularly in stressed syllables or root syllables. The short vowels [ə] and [e] are complementarily distributed allophones of the same phoneme /e/. [e] (with a more open [ɛ] alternative realization) appears only before velar consonants as in Méck [mek] ‘fly’ or zéng [ʦeŋ] ‘ten’, whereas [ə] appears in all other positions. Luxembourgish schwa is realized frequently with light lip rounding and – compared to [e] – this vowel is strongly centralized.

In contrast to Standard German, the opposition between the long and short open vowels (as in German Schal ‘scarf’ vs. Schall ‘sound’) is manifested in Luxembourgish in quantity and quality, namely [aː] and [ɑ]. Furthermore, the long and front [aː] (Sak [zaːk] ‘bag’) is close to the quality of short [æ] (hell [hæl] ‘bright’, Decken [ˈdækən] ‘blanket’) and sometimes the two even merge qualitatively.

The schwa sounds [ə] and [ɐ] are high-frequency vowels in unstressed position. In contrast to German, where it is usual to omit [ə] in closed syllables, schwa is retained in Luxembourgish (e.g., setzen [ˈzæʦən] ‘to put’ in Luxembourgish vs. [ˈzɛʦ

![]() ] in German).

] in German).

Diphthongs

Luxembourgish has eight diphthongs:

For four diphthongs the schwa region is of special relevance. The diphthongs [ɜɪ] (frequent variant [əɪ]) and [əʊ] have centralized onsets and represent more or less the inverted versions of [iə] and [uə], respectively, which end in the schwa region. The diphthongs [æːɪ] and [æːʊ] are characterized by lengthening of the onset (Bruch Reference Bruch1954), which enhances the contrast to the qualitatively close diphthongs [ɑɪ] and [ɑʊ], respectively. The lengthening can disappear in fast speech forms or in unstressed syllables. All remaining diphthongs have a vowel length similar to the long monophthongs.

Similar to Standard German (Kohler Reference Kohler1999), secondary diphthongs arise after vocalization of tautosyllabic /r/ after long monophthongs. This results in centering r-diphthongs like Dier [diːə] ‘door’, Joer [joːɐ] ‘year’ and Kär [kɛːə] ‘core’ in contrast to the consonantal appearance due to resyllabification in the corresponding plural forms Dieren [ˈdiː.ʀən] ‘doors’, Joeren [ˈjoː.ʀən] ‘years’ and Kären [ˈkɛː.ʀən] ‘cores’. For many speakers word-final /r/ in French loans like classeur [ˈklɑsœ:ʀ] ‘folder’ is also realized as a consonant.

Foreign and rare sounds

Due to many loan words from French and modern Standard German on the one hand, and the Luxembourgers’ linguistic competence in speaking both these languages on the other, we find several sounds which historically do not belong to the Luxembourgish sound system. Here is a list of example words for each of the foreign and rare vowels:

As for the affricates, the affricate [ʤ] only appears in English loans like Jeans [ʤi:ns], [pf] only in a few German loans like Kampf [kɑmpf] ‘fight’, and [dz] occurs only in few words, such as spadséieren [ʃpɑˈdzɜɪəʀən] ‘to go for a walk’.

Stress and intonation

The lexical tone contrast from the Central Franconian tonal accents (Gussenhoven & Peters Reference Gussenhoven and Peters2004) has completely disappeared from Luxembourgish (Gilles Reference Gilles, Auer, Gilles and Spiekermann2002). This development has given rise to the two sets of diphthongs mentioned above with [ɑɪ] and [ɑʊ] associated with the former Accent 1, and [æːɪ] and [æːʊ] associated with the former (lengthened) Accent 2, respectively.

Word accent in Luxembourgish may fall on the antepenultimate, the penultimate or the final syllable, with the penult as the most common stress pattern, which frequently also applies to French loans like Parfum [ˈpɑχ f

![]() ː] ‘fragrant’, Dekolleté [deːˈkolteː] ‘décolleté’. Although schwa syllables normally avoid word stress (Atelier [ˈɑtəljeː] ‘workshop’), disyllabic words with an initial schwa syllable nevertheless can attract word stress (Tëlee [ˈtəleː] ‘television’) (Gilles Reference Gilles, Dammel, Kürschner and Nübling2009).

ː] ‘fragrant’, Dekolleté [deːˈkolteː] ‘décolleté’. Although schwa syllables normally avoid word stress (Atelier [ˈɑtəljeː] ‘workshop’), disyllabic words with an initial schwa syllable nevertheless can attract word stress (Tëlee [ˈtəleː] ‘television’) (Gilles Reference Gilles, Dammel, Kürschner and Nübling2009).

Little is known yet about intonation, but a typical intonational feature of Luxembourgish is the rising-mid-falling nuclear tune, which serves to signal continuation.

Cross-word phenomena

There are various obvious phonological alternations of sounds operating at a supra-segmental level. Syllable-final -n is subject to phonologically conditioned n-deletion (Gilles Reference Gilles, Moulin and Nübling2006). In external sandhi, all final -ns are deleted unless the following syllable starts with a vowel or the consonants [h d t ʦ n] (except in some well-defined special cases). Thus, the final nasal in the article den is retained in den Dësch [dən dəʃ] ‘the table’ whereas it is deleted in de Schaf [də ʃaːf] ‘the cupboard’. Since Luxembourgish has a lot of words ending in an alveolar nasal, n-deletion occurs quite often.

Unusual consonant clusters arise postlexically due to cliticization of the definite article d’ (for feminine, neuter and plural forms) as in d'Land [dlɑnt] ‘the country’ or d'Kräiz [tkʀæːɪts] ‘the cross’. Voicing of the consonant for d’ depends on the following context.

Resyllabification and voicing of voiceless obstruents (indicated with ⌣) occurs across word boundaries when the following phonological word starts with a vowel, such as eng interessant Iddi [eŋ intʀæˈsɑnd ⌣ˈidi] ‘an interesting idea’ but also in compounds like mateneen [mɑd ⌣əˈneːn] ‘together’ (Goudaillier Reference Goudaillier and Goudaillier1987, Gilles in press). In all these cases, final devoicing is blocked and the obstruent is realized voiced.

Transcriptions of the recorded passage

The following translation of ‘The North Wind and the Sun’ in Luxembourgish orthography was read by a young male speaker (age 26 years) from the central region of Luxembourg. The broad phonetic transcription is based on this version. Stress marks apply to phrasal rather than to word level here. Intonational phrasing is indicated by [|] (‘minor phrase’) and [‖] (‘major phrase’).

Den Nordwand an d'Sonn

An der Zäit hunn sech den Nordwand an d'Sonn gestridden, wie vun hinnen zwee wuel méi staark wier, wéi e Wanderer, deen an ee waarme Mantel agepak war, iwwert de Wee koum. Si goufen sech eens, dass deejéinege fir de Stäerkste gëlle sollt, deen de Wanderer forcéiere géif, säi Mantel auszedoen. Den Nordwand huet mat aller Force geblosen, awer wat e méi geblosen huet, wat de Wanderer sech méi a säi Mantel agewéckelt huet. Um Enn huet den Nordwand säi Kampf opginn. Dunn huet d'Sonn d'Loft mat hire frëndleche Strale gewiermt, a schonn no kuerzer Zäit huet de Wanderer säi Mantel ausgedoen. Do huet den Nordwand missen zouginn, dass d'Sonn vun hinnen zwee de Stäerkste wier.

dən ˈnɔχtvɑnt ɑn ˈdzon

ɑn dɐ ˈʦæːɪt | hun zəɕ dən ˈnɔχtvɑnd ⌣ɑn ˈdzon gəˈʃtʀidən ‖

viə fun h inən ˈʦweː | vuəl ˈmɜɪ ʃtaːk v iːɐ ‖

vɜɪ ə ˈvɑndəʀɐ ‖

deːn ɑn ə ˈvaːmə ˈmɑntəl ˈɑɡəpaːk v aː ‖

ivɐt də ˈveː kəʊm ‖

ziː ɡəʊfən zəʑ ⌣ˈeːns ‖

dɑs ˈdeːjɜɪnəʑə fiɐ də ˈʃtɛːəkstə ɡələ zolt ‖

deːn də ˈvɑndəʀɐ fɔəˈsɜɪəʀə ɡɜɪf ‖

zæɪ ˈmɑntəl ˈæːʊsʦədoːən ‖

dən ˈnɔχtvɑnt h uət mɑt ˈɑlɐ ˈfɔχs ɡəˈbloːzən ‖

ˈaːvɐ vaːt ə mɜɪ ɡəˈbloːzən h uət ‖

vaːt də ˈvɑndəʀɐ zəɕ ˈmɜɪ ɑ zæɪ ˈmɑntəl ˈɑɡəvekəlt h uət ‖

um ˈæn h uət dən ˈnɔχtvɑnt zæɪ ˈkɑmbv ⌣ˈopɡin ‖

dun h uət ˈdzon | ˈdloft mɑt h iəʀə ˈfʀəntləɕə ˈʃtʀaːlə ɡəˈviːəmt ‖

ɑ ʃon n oː ˈkuːəʦɐ ˈʦæːɪt ‖

huət də ˈvɑndəʀɐ zæɪ ˈmɑntəl ˈæːʊsɡədoːən ‖

ˈdoː huət dən ˈnɔχtvɑnt m isən ˈʦəʊɡin ‖

dɑs ˈdzon f un h inən ˈʦweː | deː ˈʃtɛːəkstə viːɐ ‖

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ane Kleine, Cristian Kollmann, Fränz Conrad and two anonymous reviewers for valuable comments on a former version of this paper.