1. Introduction: what should count as a multimodal metaphor and metonymy?

Much of the work carried out in metaphor studies has focused on defining what metaphor is and how to identify it. The most basic definition of metaphor puts it as a figurative operation that uses one entity (source domain) to understand another (target domain) that is from a different semantic and/or conceptual domain (Lakoff & Johnson, Reference Lakoff and Johnson2003). In the literature, metaphor is typically denoted as ‘A (target) IS B (source)’. Agreeing on what should count as metaphor is instrumental not only for theoretical purposes to build more robust, replicable analyses but also for methodological reasons: given that many experiments rely on metaphorical stimuli, a shared understanding of what metaphor is makes findings more reproducible and generalizable, thus feeding back to the theory framing the experiment.

Most existing procedures for metaphor identification have been tested on a singular semiotic mode, namely verbal discourse (MIP, Pragglejaz Group, 2007; and its later expansion to MIPVU, Steen et al., Reference Steen, Dorst, Herrmann, Kaal, Krennmayr and Pasma2010), and are carried out with the support of dictionaries and corpus tools. Both procedures work on the level of the word by contrasting the contextual meaning of a word with the basic meaning of that word, as defined by a dictionary. If there is a mismatch between meanings, the word is annotated as having potential for metaphorical interpretation (metaphoricity).

However, from a cognitive linguistic perspective, as metaphor is a conceptual operation rather than a purely linguistic one, it can naturally manifest in other modes beyond text, such as in images (El Refaie, Reference El Refaie2003; Forceville & Urios-Aparisi, Reference Forceville and Urios-Aparisi2009), sounds and music (Zbikowski, Reference Zbikowski2009), smells (Velasco-Sacristan & Fuertes-Olivera, Reference Velasco-Sacristan and Fuertes-Olivera2006), and gestures (Cienki & Müller, Reference Cienki and Müller2008), among others. Multimodal metaphors occur when the target and/or source domain is signaled in different modes (Forceville, Reference Forceville, Forceville and Urios-Aparisi2009b). In advertising, the target domain usually coincides with the product or a feature of the product, upon which positive attributes borrowed from a different domain are mapped (Pérez-Sobrino, Reference Pérez-Sobrino2017). For example, in Figure 1, the mobile phone advertised (target) is framed as a hard worker (source), which suggests that the phone will be resilient and strong for the consumer. Cat phones are products targeted at manual laborers, who need a phone that has the properties that are mapped from the source to the target domain.

Figure 1. Advertisement for Cat mobile phone (Text: “Rugged. Resilient. Reliable. One seriously hard worker.”). Provided courtesy of Caterpillar. © Caterpillar Inc. All rights reserved.Footnote 1

Despite the emerging scholarly interest in multimodal metaphor and metonymy, more work needs to be devoted to establishing a step-by-step procedure for the identification of multimodal figurative operations in multimodal contexts in order to make research findings more generalizable, transparent, and replicable. While procedures designed for the identification of metaphor in texts are helpful, they are not directly applicable to the identification of metaphor, let alone metonymy, in multimodal discourse. An extension of MIPVU to visual data is VISMIP (Šorm & Steen, Reference Šorm, Steen and Steen2018), where analysts are instructed to mark images as metaphorical if the context suggests that two incongruous elements present in an image belong to different domains, and that the context is inviting the viewer to compare them. But even VISMIP, and its extension to moving images FILMIP (Bort-Mir, Reference Bort-Mir2019), rely on verbal tools such as WordNet to infer a contrast between basic and metaphoric meaning. The lack of established corpora of multimodal metaphors and metonymies equivalent to that of, for example, the British National Corpus (BNC, Davies, Reference Davies2004) or the Corpus of Contemporary America English (COCA, Davies, Reference Davies2008), and a lack of automatized systems for identification, restricts large-scale analyses of multimodal metaphor and metonymy (Pérez-Sobrino, Reference Pérez-Sobrino2017). The characteristics of visual language, the affordances and limitations of annotating metaphorical mappings, as well as other features such as genre conventions, call for the formulation of specific methodological tools.

A similar research need applies to metonymy, another figurative operation that refers to an entity from a related semantic and/or conceptual domain to another entity (Forceville, Reference Forceville, Ventola and Guijarro2009a), such as “Hollywood” to refer to the place where films are recorded (Littlemore, Reference Littlemore2015). Metonymy is typically denoted as ‘B (source) STANDS FOR A (target)’. Much in the same way as metaphor, metonymy is a conceptual operation that can manifest across different modes (see Forceville, Reference Forceville, Ventola and Guijarro2009a, for an introduction to the notion of multimodal metonymy). For example, in an advertisement for the giffgaff mobile phone network (Figure 2), the fist is standing for a fist bump, a gestural signal for respect that giffgaff gives the customer @LayolaLotus.

Figure 2. Advertisement for giffgaff mobile phone network (Text: “*fist bump*@LayolaLotus. We don’t like contracts. But we do like you.”). Illustrator: Serge Seidlitz.

When dealing with authentic data, such as real advertisements, an additional challenge for the identification of metaphor and metonymy in discourse is that they can be context-specific and innovative (Hidalgo-Downing & Mujic, Reference Hidalgo-Downing and Mujic2020; Littlemore & Tagg, Reference Littlemore and Tagg2018). The nuance of these operations in different contexts requires more attention from analysts in order to refine what counts as a metaphor and metonymy and to decide how their identification is operationalized in specific contexts. Researchers have developed various procedures that aim to achieve a higher percentage of agreement in what metaphors are identified across multiple analysts, although there has been virtually no attention paid to identification procedures for metonymy.

In our article, we present a procedure for multimodal metaphor and metonymy identification (with a focus on advertising) and put it to the test by conducting an inter-rater reliability study. It is not our aim to offer a coded, usable dataset, but rather to explore the extent to which two researchers can agree on their annotations of figurative operations in multimodal advertising, identifying the main challenges, refining the working definitions as much as possible, and raising potential red flags. Our threefold aim is to do the following:

-

1. Lay out an annotation manual to identify and annotate multimodal metaphor and metonymy in advertising;

-

2. Draw attention to other potential variables that may explain variation in the application of an annotation manual (e.g., researchers’ background knowledge, genre conventions);

-

3. Raise awareness of the benefits of inter-rater reliability tests as a tool to refine an annotation manual.

Inter-rater reliability refers to the extent to which independent analysts make similar annotations based on the same set of rules. High inter-rater reliability scores indicate that a procedure is transparent enough for two independent annotators to produce similar annotations and can therefore be taken as a proxy for the robustness of a procedure. By examining inter-rater reliability results we do not intend to find a replacement for, or propose a complete set of answers addressing, existing procedures; rather, we aim to raise a set of considerations for researchers attempting consistence in their annotation of multimodal metaphor and metonymy or for researchers interested in developing identification procedures for multimodal figurative operations.

The research questions (RQ) driving our study are as follows:

RQ1. Can multimodal metaphor and metonymy be reliably identified?

Our main working hypothesis is that we can agree on some basic features of what should count as a multimodal metaphor and metonymy, and therefore predict that similar annotations by different analysts can be reached in a reliable way. However, we do envision a degree of mismatch in our annotations. We formulate two additional research questions to deal with potential sources of variation in the annotation between analysts and propose ways to address them.

RQ2. If multimodal metaphor and metonymy can be reliably identified, is reliability subject to genre conventions?

Does product-specific advertising posit stricter genre conventions that make the presence of some metaphoric or metonymic mappings more predictable than generic advertising? In order to address this question, we compare our annotations of generic advertisements (i.e., a range of products and services) with our annotations of genre-specific mobile phone advertisements (that sell phones or data plans). We predict that the narrower range of potential persuasive messages in mobile advertising is more likely to constrain the number of potential metaphorical and metonymic source domains invoked, potentially making these mappings more predictable. For instance, many mobile advertisements display hands (rather than a full depiction of a person) in order to convey the user’s ownership of their new phone. The commonality of this visual metonymy is specific to this genre of advertising. Generally, hands are not only associated with ownership, and in other contexts the depiction of a hand may mean something else entirely.

RQ3. Does reliability increase with analyst experience gained with practice?

In many identification protocols, resolving analyst disagreement is addressed as a ‘discussion and reconciliation’ process without reporting many details; likewise, the nature and degree of successful training in using the procedure are barely mentioned. Whereas we test and track the evolution of analyst experience in more depth by asking the following question: To what extent does splitting the annotation over several rounds, with interim discussions of the cases of disagreement, raise the level of agreement between analysts? We predict a steady improvement in the consistent application of the procedure, with higher levels of inter-rater agreement toward the final round of annotation. However, given the inherent creative (and sometimes disruptive) nature of the examples under scrutiny, we envision reaching a threshold of agreement that cannot be surpassed, although we cannot anticipate when in the process it will be placed.

In Section 2, we review existing procedures that identify multimodal metaphor and consider how these may be used to develop a procedure for identifying multimodal metaphor and metonymy, and justify our research questions. We explain our new procedure in Section 3, detail our method and inter-rater reliability tests in Section 4, and discuss our findings in Section 5. We illustrate the steps of our procedure with examples from our corpora of 41 authentic advertisements, and discuss the main challenges encountered in the identification and characterization of multimodal figurative communication. We conclude this paper by returning to the question driving our study, ‘What counts as a multimodal metaphor and metonymy?’ in Section 6.

2. Procedures to identify multimodal metaphor and metonymy

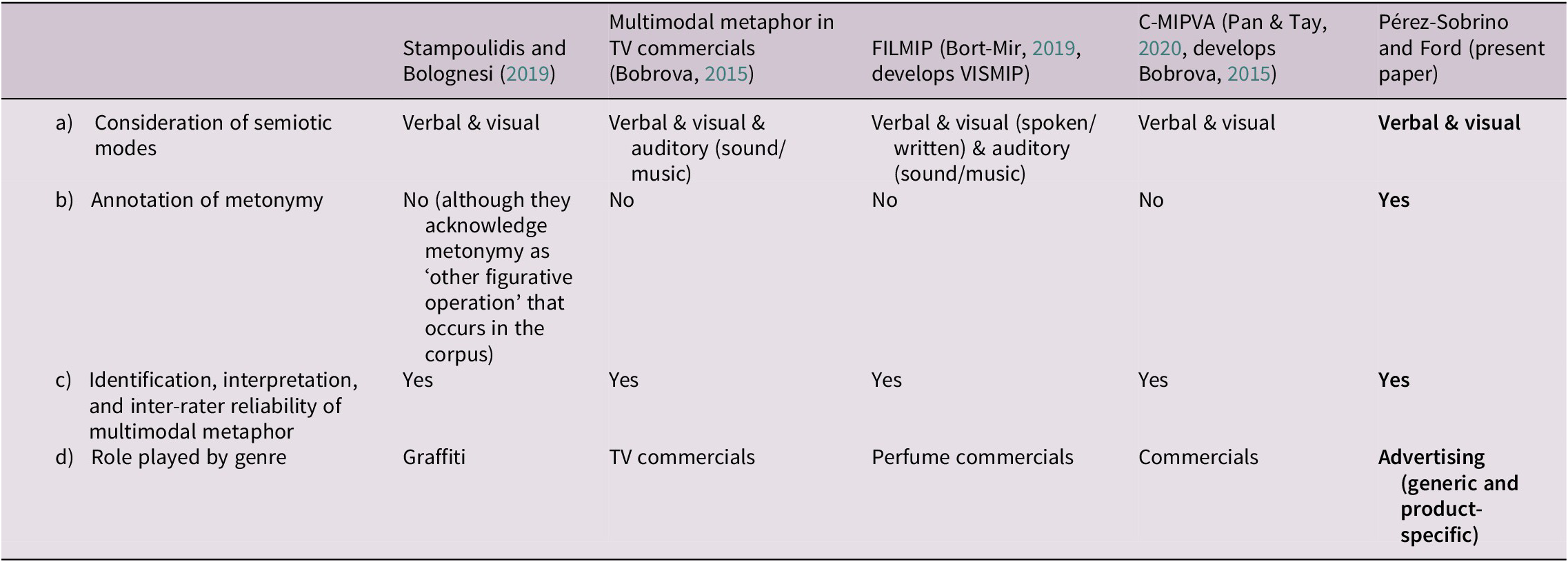

Our procedure has been inspired by the work carried out by scholars in the field of multimodal metaphor identification. In this section we present and compare the affordances of earlier procedures, and inter-rater reliability measures, against ours. We do not wish to make any claims as to the validity of one procedure over another, nor as to particular inter-rater measures; rather, we wish to motivate our decisions in the formulation of our own variables of interest and criteria for annotation and analysis. See Table 1 for a comparison of the procedures reviewed in this section in terms of the following variables of interest: (a) consideration of semiotic modes, (b) annotation of metonymy, (c) identification, interpretation, and inter-rater reliability of multimodal metaphor, and (d) role played by genre.

Table 1. Summary of affordances of multimodal metaphor identification procedures

2.1. Consideration of semiotic modes

Stampoulidis and Bolognesi (Reference Stampoulidis and Bolognesi2019) propose a cognitive, semiotic identification procedure for multimodal metaphor in Greek street art, based on VISMIP, whereby the verbo-pictorial scenario (street art) is marked as metaphorical if it stimulates the viewer to disentangle incongruities that belong to different domains. Stampoulodis and Bolognesi analyze metaphor as a form of polysemiotic communication that combines two interacting semiotic systems: language and depiction. They explain that various sensory modalities, such as sight (visual), hearing (auditory), smell (olfactory), touch (tactile), and taste (gustatory) may be triggered according to the viewer’s perception (further explanation in Stampoulidis et al., Reference Stampoulidis, Bolognesi and Zlatev2019). For example, an advertisement for earphones may trigger auditory perceptions, or for an ice cream may trigger gustatory perceptions, despite the product only being presented visually.

With the growing interest in multimodal metaphor studies, more combinations of different modes are being acknowledged, although research extending metaphor identification to more than the verbo-visual modes is still embryonic. Interdisciplinary procedures combining cognitive science and film studies are the filmic metaphor identification procedure FILMIP (Bort-Mir, Reference Bort-Mir2019), and the procedure for the identification of multimodal metaphor in TV commercials (Bobrova, Reference Bobrova2015), later developed into the creative metaphor identification procedure for video advertisements C-MIPVA (Pan & Tay, Reference Pan, Tay, LIN, Mwinlaaru and Tay2020). FILMIP is intended to be a “dynamic version of VISMIP,” considering visuals, written discourse, spoken discourse (voice), sound, and music, and is concerned with the identification of metaphoricity (Bort-Mir, Reference Bort-Mir2019: 110). Bobrova (Reference Bobrova2015) and C-MIPVA focus on the construction of metaphor through filmic techniques where incongruence or the interaction of different modes in moving images “contribute to creating a noticeable and impressive transfer of meaning between two different things [concepts attributable to a target and source domain] to assist in achieving a commercial purpose” (Pan & Tay, Reference Pan, Tay, LIN, Mwinlaaru and Tay2020: 217).

While in our procedure we maintain the modal distinctions of verbal (written discourse) and visual (image) modes, we understand, and take into account, the role verbo-pictorial elements can play in sensory inputs that may contribute toward the main message of an advertisement.

2.2. Annotation of multimodal metonymy

While Stampoulidis and Bolognesi, Bobrova, C-MIPVA, and FILMIP have discussed instances of metaphor, there is little to no discussion of metonymy or measurement of inter-rater reliability for metonymy. As metonymy plays a crucial role in motivating and providing access to metaphorical meaning, we believe metonymy should be involved in the process of metaphor identification at least to some degree. In an attempt to unify the identification of both metaphor and metonymy under an umbrella procedure, Pérez-Sobrino et al. (Reference Pérez-Sobrino, Littlemore and Houghton2019) developed a number of steps to identify metaphor and metonymy in multimodal advertising, which we take up and update in the present article.

The starting point of these steps is similar to that of VISMIP, and Stampoulidis and Bolognesi, in that one should identify the incongruous part of the advertisement under consideration. In the next two steps, Pérez-Sobrino, Littlemore, and Houghton decided which items of the advertisement should correspond to the target domain (which usually coincides with the product or service being advertised) and the source domain (that is, the invoked scenario whose features are borrowed to portray a positive image of the product or service being advertised). In a final step, they decided whether the mapping between both domains is metaphoric or metonymic. The authors reached strong agreement with metaphor (Krippendorff’s alpha = 0.71) but only weak agreement with metonymy (Krippendorff’s alpha = 0.45)Footnote 2. With metonymy identification still in the early days, further research is required to create, test, and refine the operationalization of metonymy identification procedures, as is our contribution with this article.

2.3. Reporting inter-rater reliability results for the identification and interpretation of multimodal metaphor

One way to measure the robustness of an identification procedure is to test the extent to which the interpretations annotated by the researchers following the same set of instructions converge or diverge from each other. Inter-rater reliability scores are a good indicator of such gaps and also highlight the specific place where adjustments are needed in the procedure, thus contributing to reducing the subjectivity inherent to the task of identifying figurative language ‘in the wild’. As can be seen in our analysis, in some cases achieving high inter-rater reliability scores is possible through the elaboration of the working definitions and clear examples; in other cases, the procedure reaches its limit because some advertisements are deliberately ambiguous.

Relying on inter-rater reliability tests to improve metaphor identification is a relatively recent strategy followed by researchers across linguistics, psychology, rhetoric and communication studies, among other disciplines (for a thorough review, see Bolognesi et al., Reference Bolognesi, Pilgram and van den Heerik2017). Increasing the validity and reproducibility of inter-rater reliability scores for metaphor analysis has been achieved through a number of methods: the collaborative coding of multiple researchers (Maslen, Reference Maslen, Semino and Demjén2016), participant involvement in the analysis (Davies et al., Reference Davies, Watson, Bakerson, Wan and Low2015), triangulating metaphor identification with other sources such as interviews or field notes (Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong, Davies and Paulson2011) or consulting the literature (e.g., Grady, Reference Grady1997), and acknowledging one’s own cultural, experiential background as an analyst (Declercq & Van Poppel, Reference Declercq and Van Poppel2023). As is the case with our study (see Section 4.2. ‘Procedure’), having researchers with different linguistic, cultural, and experiential backgrounds can result in a critical examination of data and procedure as it brings different perspectives and, as Declercq and Van Poppel (Reference Declercq and Van Poppel2023, p. 7) put it, “makes visible the unconscious layers of interpretation that occur in any qualitative analytical process.”

Inter-rater reliability is commonly calculated using Cohen’s kappa (Cohen, Reference Cohen1960). Kappa scores differ from percentages in that they range from 0 (null agreement) to 1 (complete agreement). A score of 0 means that the obtained agreement is equal to chance agreement; a positive value means that the obtained agreement is higher than chance agreement. Although there is no consensus on how to interpret kappa scores, scores above 0.80 are acknowledged to ensure an annotation of reasonable quality. Scores above or equal to 0.67 are also acceptable, provided that significance is reached (Artstein & Poesio, Reference Artstein and Poesio2008).

Whereas the rule of thumb in psychology is that strong agreement should be 85% or higher, in the specific case of metaphor identification, the convention is that strong agreement is achieved through scores greater than 0.7 (Bolognesi, Reference Bolognesi2017) or even 0.8 (Carletta, Reference Carletta1996). For instance, in their study on metaphor identification in street art, Stampoulidis and Bolognesi (Reference Stampoulidis and Bolognesi2019) found strong agreement for metaphoricity (Cohen’s kappa = 0.865). They tested the reliability of their interpretation of metaphor (i.e., conceptual labels for source and target domains) using a four-step procedure that aimed to identify the content of the metaphorical message in the street art corpus. Two external analysts evaluated the extent of agreement between the authors in order to check whether the procedure led to the same labeling of metaphor. According to the external analysts, there was agreement between the authors for identifying the topic of the street art and for whether there were incongruous elements present; however, the authors’ decisions over whether the elements belonged to different domains and conveyed a pragmatic message were less reliable. Stampoulidis and Bolognesi (Reference Stampoulidis and Bolognesi2019: 1) suggested these latter results may have been due to the variability in individual analysts’ pragmatic interpretation that was dependent on “conceptual, contextual, socio-cultural and linguistic knowledge.”

Similarly, Bort-Mir (Reference Bort-Mir2019) trained two analysts and engaged one untrained analyst to test the reliability of each step of the FILMIP in two perfume commercials, which resulted in high agreement (Fleiss κ and Krippendorff reliability tests were all above 0.7). However, the qualitative interpretation of 21 and 18 analysts for two commercials, respectively, varied considerably (from 50% to 3.8% agreement), which Bort-Mir suggested may be due to individual differences in cultural and social background, their level of expertise, and the complexity of the task, although these factors were not tested.

Pan and Tay (Reference Pan, Tay, LIN, Mwinlaaru and Tay2020: 234) found that when verbalizing metaphor in moving images, conceptual labels could differ between analysts. Verbalizing non-verbal metaphors is not a neutral task (Forceville, Reference Forceville, Forceville and Urios-Aparisi2009b), and a “certain degree of individual variance…is unavoidable” (Pan & Tay, Reference Pan, Tay, LIN, Mwinlaaru and Tay2020: 234). However, Pan and Tay demonstrate that this issue can be resolved; the analysts discussed the linguistic expression of metaphor prior to their testing the inter-rater reliability, which resulted in high agreement of metaphoricity (Fleiss’ kappa k = .78).

In light of the inter-rater reliability research reviewed here, we examine the inter-rater reliability scores of metaphor and metonymy identification and interpretation in the collaborative coding of two researchers. Our annotation manual feeds from a combination of inter-rater reliability tests performed on initial annotations done independently by the researchers and subsequent discussions to assess the extent of agreement to refine the procedure for the ensuing round of annotations. This is so because an acknowledged drawback of pursuing high reliability (indicating replicability) is that it is sometimes linked to oversimplified coding schemes that fail to capture relevant but nonreplicable interpretations. The analysts should, therefore, try to find a middle ground between highly replicable and highly accurate coding systems (Krippendorff, Reference Krippendorff2013). We consider reasons for agreement and disagreement, including the researchers’ linguistic, cultural, and experiential background, their expertise in metaphor analysis (taking into account their knowledge of the literature on this topic), and advertising genre, consulting the literature and inventories on metaphor domains when necessary.

2.4. Role played by genre

An additional variable in these studies is genre. According to Caballero (Reference Caballero, Semino and Demjén2016: 195), genre is a particular kind of discourse that groups together usage events and routines as norms that serve conventionalized communicative functions. Genre norms may shape the kinds of metaphors or metonymies that are used in the context of that genre. For instance, Stampoulidis and Bolognesi (Reference Stampoulidis and Bolognesi2019) focused on the role played by the specificities of street art, whereas Pérez-Sobrino et al. (Reference Pérez-Sobrino, Littlemore and Houghton2019) focused on advertising. Bort-Mir (Reference Bort-Mir2019) tested five perfume advertisements to demonstrate the application of FILMIP, a genre of advertising that is ripe with the use of figurative meaning, particularly metaphor (Lievers, Reference Lievers2017: 52), as metaphor helps convey via the TV screen the most ineffable of senses: smell (Levinson & Majid, Reference Levinson and Majid2014). Pan and Tay (Reference Pan, Tay, LIN, Mwinlaaru and Tay2020) found that identifying creative (i.e., uncommon) multimodal metaphors in 10 commercials for tangible products was more likely to result in agreement between analysts than for intangible products. Their findings suggest that the type of product (like genre) may influence the ease with which analysts can identify metaphors in commercials.

What these studies (Bort-Mir, Reference Bort-Mir2019; Pan & Tay, Reference Pan, Tay, LIN, Mwinlaaru and Tay2020; Stampoulidis & Bolognesi, Reference Stampoulidis and Bolognesi2019) suggest is that the expertise and contextual knowledge of the analysts play a crucial role in the reliability of identifying metaphor in multimodal discourse, as well as genre. An aspect that has not been paid enough attention is the expertise gained by analysts over the course of their annotations. Steen et al. (Reference Steen, Dorst, Herrmann, Kaal, Krennmayr and Pasma2010) report a series of independent studies showing that kappa scores increased as the analysts became more familiar with the procedure (in this case for verbal metaphor identification). In our study, we have added genre and a practice effect as variables to explore variations in the reliability scores for identifying and interpreting multimodal metaphor and metonymy according to figurative language type (RQ1), advertisement type (RQ2), and round number (RQ3).

3. A stepwise procedure to annotate multimodal metaphor and metonymy in advertising

As we have shown in the previous section, our procedure differs from others in its explicit interest in multimodal metonymy alongside metaphor. Our procedure expands previous work by Pérez-Sobrino (Reference Pérez-Sobrino2017) and Pérez-Sobrino et al. (Reference Pérez-Sobrino, Littlemore and Houghton2019). In four steps, the procedure aims to detect the potential for figurative meaning in printed multimodal advertisements and to discern whether or not it is metaphoric and/or metonymic. It does not aim to provide instructions to formulate conceptual labels (as is the case, for example, of MetaNet, Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Lupoiu, Wang, Sell, Paul Hugonin, Lalanne and Fan2020), although we did annotate our own interpretations of identified metaphors and metonymies to perform an inter-rater reliability test.

A full version of the procedure with the refinements we made at each round of annotation is available in an openly accessible repository: https://osf.io/eg583/. However, due to space constraints, we illustrate a summarized version of the steps with an example for buyresponsibily.org from our corpus.

3.1. Step 1. Formulate the main message of the advertisement

First, the analyst needs to summarize, in a single sentence, what the advertisement is about. Given that advertisements usually have multiple co-occurring metaphoric and metonymic mappings at work (for a review, see Pérez-Sobrino, Reference Pérez-Sobrino2017), we decided to verbalize what would be considered as the main persuasive message of the advertisement under consideration. That way we would disregard secondary but pervasive mappings, such as metonymies like LOGO FOR BRAND. For example, in Figure 3, the message could be phrased as “irresponsible shopping exploits workers.” Although this advertisement may seem straightforward, there are more narratively complex advertisements with multiple co-occurring messages where it is not always clear what the actual mapping is that promotes the product.

Figure 3. Advertisement for buyresponsibly.org (Text: “What’s behind the things we buy? Buyresponsibly.org”).

3.2. Step 2. Identify what product or service is being promoted

As pointed out by Forceville (Reference Forceville1996: 121), the product tends to coincide with the target domain of the mapping; that is, whatever it is the advertisement claims about the product, positively or negatively. In Figure 3, reckless, irresponsible, unethical shopping is verbally cued by the word “buy” and visually cued by the shopping trolley and the white price tag.

3.3. Step 3. Elicit what is being said about the product (or its related attributes)

This step involves looking at the visual, verbal, or verbal-visual (multimodal) incongruity presented in the advertisement (if there is one) and describing what ideas are borrowed from another domain to talk about the product. As pointed out by Forceville (Reference Forceville, Forceville and Urios-Aparisi2009b: 30), verbalizing non-verbal metaphors is never neutral, given that there is no “like” or “is like” structure to link source and target domains. We do not wish to make any claims in this regard, and use verbalization exclusively for practical purposes. In order to identify the most likely source domain in the advertisement, we rely on previous research on visual operations undertaken in the field of cognitive linguistics, visual semiotics, and marketing (for a detailed review, see Pérez-Sobrino et al., Reference Pérez-Sobrino, Littlemore and Ford2021: 40). Specifically, we resort to the triggers for visual similarity formulated by Gkiouzepas and Hogg (Reference Gkiouzepas and Hogg2011): juxtaposition of the visual unit identified as target domain in step 2 with something else; replacement of such target domain for another element that feels incongruous in the visual context; and fusion of the target domain with another thing. For Figure 3, we annotate the trolley as the source domain as it is replacing a cage (because of its display and size) in which the workers are trapped.

3.4. Step 4. Establish if the mapping is metaphoric, metonymic, or both

In this step we decide whether the relationship between the target and the source domains identified in steps 2 and 3 is metaphoric or metonymic to best describe the message verbalized in step 1. Be aware that there may not be a relevant figurative connection there, in which case the advertisement can be annotated as having no metaphor or metonymy. Step 4 is probably the hardest step, as it involves connecting the different verbal and visual elements annotated in previous steps. In our case, the task involves deciding whether the image of the trolley, the price tag, the words “the things we buy” (referring to the idea of shopping), and the cage with prisoners inside (visually cueing exploitation) are connected through an A IS B (metaphor) and/or A FOR B (metonymy) mapping (where A is the target and B is the source).

In the context of general and genre-specific (mobile phone) advertising, our initial definitions for metaphor (TARGET (product/company) IS SOURCE (verbo-pictorial context)) and metonymy (SOURCE (feature of the product/company) FOR TARGET (product/company)) were refined over six rounds of annotations with the following result: metaphor as TARGET (product/service/company) IS SOURCE (feature/function of product/service/company in the verbo-pictorial context); and metonymy: SOURCE (feature/function of product/service/company) FOR TARGET (product/service/company). Further indications as to what counts as metaphor and metonymy are noted in our annotation manual.

With respect to Figure 3, the incongruous elements in the picture, the trolley and the cage, are distinct enough for a metaphoric mapping to take place; they allow for the interpretation of the advertisement in terms of visual metaphor. However, the advertisement is not about trolleys, but rather about reckless shopping. It can thus be argued that the visual depiction of the trolley provides a point of access to a more complex (and increasingly difficult to depict in a straightforward way) idea of shopping through a further multimodal metonymic mapping. This mapping interaction between the visual metaphor and multimodal metonymy is also known as metaphtonymy (Díez Velasco & Ruiz de Mendoza Ibáñez, Reference Díez Velasco, Ruiz de Mendoza Ibáñez, Dirven and Pörings2002).

3.5. Summary of main refinements added over the course of rounds of annotation

The absence of a finite set of conceptual labels to formulate source and target domains, and the sometimes-intended ambiguous nature of advertisements, makes it hard to reach an exact or similar interpretation of the advertisement. However, over the course of the rounds of annotation we learnt a number of lessons that helped us narrow the gap between our annotations. These refinements were critical to revisit what should count as agreement for the inter-rater reliability studies. Together with a compilation of illustrative examples (taken as ‘gold standards’), these revisions were added to the manual over the course of six rounds of annotation following a color coding system that indicates the precise rounds in which they were incorporated. We briefly overview below the three most relevant refinements: (a) inclusion of metaphoric scenarios within the ‘metaphor’ label, (b) discarding logos from the ‘metonymy’ label, and (c) annotating personification as a separate category.

(a) Metaphoric scenarios . When the message identified was more general and represented a narrative event or a scenario, we annotated it as a figurative operation involving ‘SCENARIO A’ and ‘SCENARIO B’ (Musolff, Reference Musolff2006), and therefore fell within the metaphor category. For example, an advertisement for a guitar (Figure 4) shows an exit sign with a person running toward the fire exit holding a guitar (the rock star), followed by other people (crazy fans): SCENARIO A (exiting the building due to a fire) is mapped onto SCENARIO B (rock band running to escape crazy fans).

Figure 4. Advertisement for Fender guitar. The Fender logo and headstock are registered trademarks of FMIC.

(b) Logos . As can be seen in the example above, many (if not all) advertisements show a logo that metonymically affords access to the company, or provides essential information about the company. Logos are often displayed in one of the corners of the advertisement, outside what can be considered the main image or main message, and act merely as a subsidiary link between the product and the company. Although logos convey key information through the choice of colors (Jonauskaite et al., Reference Jonauskaite, Parraga, Quiblier and Mohr2020), typeface (Hyndman, Reference Hyndman2016), and sounds used in the name (Spence, Reference Spence2012), in our study the logo and its typography should only be coded if they are a part of the main image and contribute to developing the main narrative of the advertisement. An example of the narrative potential of logos in advertising can be seen in Figure 5, where the different typefaces and corporative colors help to cue the different ‘businesses’ mentioned in the advertisement.

Figure 5. Advertisement for Peugeot.

(c) Personification . We added a separate category for personification because it is sometimes difficult to distinguish whether it has a metaphoric or metonymic basis. For example, an advertisement for shoes (Figure 6) portrays a person’s fingers with painted nails as eyes for a pair of shoes with the caption “You are what you wear.” Is it that the shoe behaves like a person through the attribution of human attributes (hinted at in the visual part of the advertisement), or that the shoe is a prominent part of the customer to the extent that it defines who they are (most likely interpretation conveyed in the verbal part)? Personification can involve non-human creatures as the source domain, but still refer to human traits or features that personify that entity. For example, a genie or angel are mythical beings (non-human), but they take human form and have human mannerisms; therefore, depending on the mapping in the advertisement, these can be annotated as personification, and it is taken out of the metaphor-metonymy annotation given its ambivalent interpretation.

Figure 6. Advertisement for MAX shoes (Text: “You are what you wear”).

Overlapping metaphors and metonymies . A potential challenge for annotation was cases where metaphor and metonymy interacted in the advertisement. Do we need to annotate them both? In such cases, not mutually exclusive interpretations were determined as agreement if there was a singular, more basic figurative operation that could underlie the interpretations. Consider an advertisement for a mobile phone (Figure 7) that is referred to as a ‘comeback’, which has double meanings: the phone is back on the shelves to buy, and the phone is like a famous star making a comeback/return to the stage. This pun is part of the wit of the advertisement and leads to different interpretations about what is mapped. We decided through discussion that an underlying primary metaphor for JOURNEY (that one could return from) encompassed these different meanings and still communicated the core message of the advertisement.

Figure 7. Advertisement for Lumia phone (Text: “Everyone loves a comeback”).

These examples were used as the ‘golden standard’ in our annotation manual; that is, we used them as cases of reference as to what counted as agreement. The reader may refer to the annotation manual for a more detailed discussion of these and other examples.

4. Methodology

We acknowledge that this is a small-scale study, but our findings shed light upon indicative effects that invite a larger-scale replication to confirm them. However, in order to compensate for the limitations of the dataset, and increase the reproducibility and relevancy of our procedure, we provide below a clear account of our materials and methods. Our dataset, annotation manual, and R scripts are available in a public repository: https://osf.io/eg583 (advertisements are not included due to copyright reasons). For further arguments in this line, see Bastian (Reference Bastian2016).

4.1. Materials

A random sample of 42 advertisements was selected from two larger corpora of advertisements compiled for two previous studies (Ford, Reference Ford2017; Pérez-Sobrino, Reference Pérez-Sobrino2017). In order to inform RQ2 (that looks into genre as a source of variation in reliability scores), Ford randomly selected 21 generic advertisements from a corpus of 210 advertisements that promoted a variety of physical goods and services (explained in Pérez-Sobrino, Reference Pérez-Sobrino2017, pp. 82–84), where the researcher collected a balanced number of examples for seven types of goods, including products and services; and in order to ensure the representation of the corpus, the researcher only retained every third advert of those initially found. Ford sampled 21 mobile phone advertisements that sold mobile phones, and call and data plans from a corpus of 48 advertisements (Ford, Reference Ford2017). All the generic advertisements were extracted from the database Ads of the World (www.adsoftheworld.com) and the genre-specific advertisements for mobile phones were extracted from Advanced Google Search. For our study, the advertisements were grouped into six rounds of seven advertisements each (three rounds of seven generic advertisements and three rounds of seven mobile phone advertisements).

4.2. Procedure

Figure 8 shows the stages of our study. After compiling the corpus (1), we drafted the annotation manual (2). The stages covered in detail in this paper are the annotation of the 42 advertisements in six rounds of seven advertisements each, preceded by a training round of three advertisements to cohere understanding of the initial procedure (3), with interim discussions of the annotations (4), and the inter-rater reliability test (5, explained in more detail in Section 4.3).

Figure 8. Stages of the study.

We annotated the advertisements independently following the four-step procedure described in Section 3. We met after each round to discuss diverging annotations with respect to our identification and interpretation of metaphor and metonymy, and our labeling of source and target domains, to see at which step of the procedure our annotations differed and to consider any refinements that needed to be made to the annotation manual. The purpose of these meetings was not to agree on any specific interpretation over another, as sometimes several readings are equally valid, but to find the best way to revise instructions that are too general. We documented each refinement in our annotation manual after each round of annotation. We noted any instances of pervasive mappings that we removed from further analysis (e.g., LOGO FOR BRAND). Declercq and van Poppel (Reference Declercq and Van Poppel2023, p. 7) refer to this as establishing necessary “cut-off points on the continuum” of novel to conventional metaphors (and metonymies) in the analysis. We also documented any difficult cases so that we could refer back to them as examples in future annotation rounds. The revised procedure was applied in the subsequent rounds of annotations.

Refining the annotation manual over rounds of annotations developed our shared understanding of source domains and target domains and what metaphor and metonymy is in our multimodal advertising corpus. Our annotation manual became a tool to consult as we independently analyzed the data, with it assisting with difficult or on-the-fence cases (similarly to Declercq & van Poppel, Reference Declercq and Van Poppel2023). The annotation manual also enabled us to remain more consistent with our independent annotation, as well as establishing our collaborative definition of metaphor and metonymy in this context.

The researchers in this study are both linguists with a shared interest and expertise in metaphor and metonymy in advertising. Their cultural background is different: Pérez-Sobrino is Spanish and Ford is British. For future researchers interested in our procedure, we suggest that at the beginning of the annotation manual they establish crucial background knowledge about metaphor and metonymy to assist in the reproducibility of the analysis.

4.3. Inter-rater reliability tests

We conducted two complementary tests to check the reliability of our procedure (see Figure 9). In Study 1, we performed an inter-rater reliability test on our annotations on the potential of the advertisement presenting a metaphoric and/or metonymic mapping. This annotation corresponds to step 4 in our procedure, where we asked whether the product advertised (target domain, step 2) and what was being said about it (source domain, step 3) were best described in terms of a metaphoric or metonymic mapping, involved both, or none. Given that we are two researchers annotating the same number of stimuli (42 advertisements) and have a binary categorical answer for the two figurative operations (treated independently: is there a metaphor? yes/no; is there a metonymy? yes/no), we report Cohen’s kappa (Cohen, Reference Cohen1960). This statistical test measures the agreement between two analysts in a way that takes into account the possibility of agreement occurring by chance, thus making it a more robust measure than observed agreement. Cohen’s kappa ranges from 0 (null agreement) to 1 (complete agreement).

Figure 9. Visual summary of the two reliability tests conducted.

In Study 2, we retained the cases for which both analysts agreed on the potential for metaphoric and/or metonymic interpretation (as independent annotations) and investigated the extent to which we interpreted the mapping in the same way. In other words, we measured the extent to which we identified similar target (step 2) and source (step 3) domains in the mapping. This follow-up study is relevant for two reasons. First, because there might be several overlapping figurative messages at work in the advertisement, but not all of them might be equally relevant. If we are to test the reliability of the procedure, we should be able to discern the most relevant message from the supporting or accessory messages. Second, because even if we agree on what is the main message of the advertisement, we may pick up on different multimodal cues to interpret the advertisement depending on our background, preferences, or previous experience, which might lead to slightly different interpretations of the advertisement. As illustrated in Figure 11, after examining our annotations in steps 2 and 3, we coded them as ‘similar’ whenever our annotations for source and target domains referred to similar ideas (we did not look at a finite set of conceptual labels since there are many mappings that could reflect the creativity of advertising messages). If there was only one coincidence (either source or target domain), we coded it as ‘partial’ agreement. If we picked up on different multimodal cues and ended up with different source and target domains, we coded it as ‘different’ interpretations.

5. Findings

5.1. Study 1. Identifying multimodal metaphor and metonymy

We now report the results from our first inter-rater reliability test, where we explore the extent to which two independent analysts, following the instructions summarized in Section 3, are able to agree on their annotations of multimodal metaphors and metonymies in our corpus of advertisements. This task is a yes/no issue concerned with the identification of a metaphor or metonymy structuring the main message of an advertisement. The identification of the ideas connected in the mapping is a more qualitative matter and is dealt with later in Study 2. To assess the level of agreement between two analysts, in line with the previous research using inter-rater reliability tests as a tool to validate metaphor identification procedures reviewed in Section 2.3, we interpreted the kappa scores based on definitions outlined by Altman (Reference Altman1990) for slight (0.2–0.4), fair (0.4–0.6), moderate (0.6–0.8), and substantial (0.8–1) agreement. This is perhaps a conservative approach to assess the agreement of our annotations, provided the sometimes-intended ambiguity of the advertisements that makes annotation subjective. However, given the scarcity of studies of a similar nature to take as reference, we decided to adopt the conventional interpretation of kappa scores. Future research should question and consider more flexible levels of agreement.

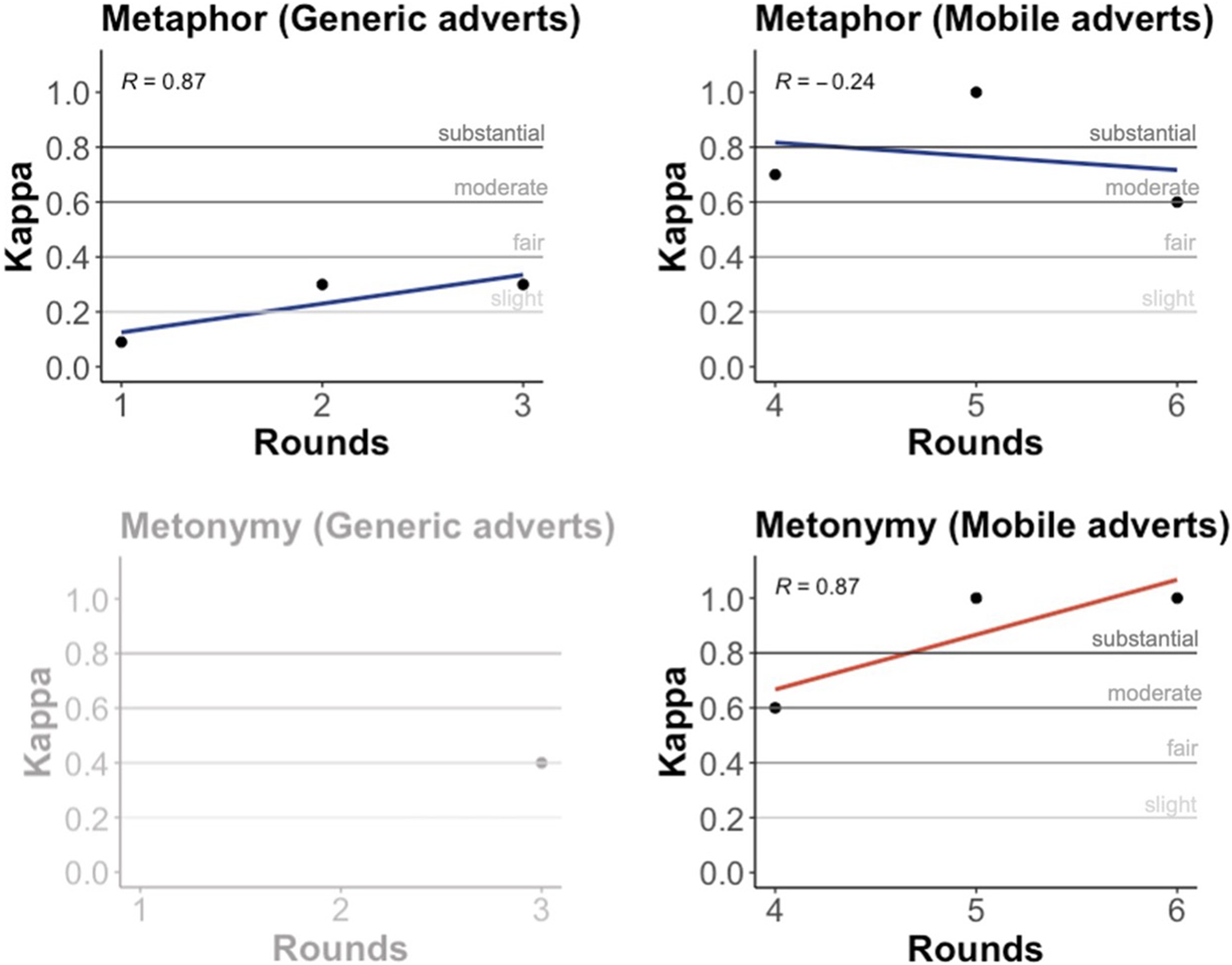

5.1.1. Headline finding: multimodal metaphor and metonymy can be reliably identified in advertisements, and it gets better with practice

Figure 10 shows the evolution of the kappa values reported for the identification of metaphor and metonymy across six rounds of annotations (RQ1). The kappa scores for both metaphor and metonymy increase in a consistent fashion across rounds, from almost null agreement for metaphor in the first round (ᴋ < 0.2) to above moderate in the latter rounds of annotation (ᴋ= > 0.6), and from fair (ᴋ = 0.4) to perfect (ᴋ = 1) agreement for metonymy.Footnote 3 We report Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) in Figure 5 to show whether the agreement increases or decreases with practice (RQ3) by correlating Cohen’s kappa with the number of rounds. The analysts benefited from practice as they were more likely to converge in their annotations towards the final rounds, with a faster evolution for metonymy (r = 0.95) than for metaphor (r = 0.82).

Figure 10. Evolution of inter-rater reliability by figurative language type across rounds.

What Figure 10 shows is that, whereas inter-rater reliability improved across rounds for both metaphor and metonymy (k > .6, moderate to substantial), there was a better performance for metonymy. This might be because the understanding of what counts as metonymy is more constrained in our procedure to focus exclusively on the main message and exclude supporting or accessory metonymies to be annotated, such as the logo standing for the brand. We included in the procedure an explicit instruction to annotate instances of personification as a separate category (see our analysis of Figure 1). This was a critical decision because personification can be interpreted as not only having potential for metaphoric interpretation (by portraying a mobile phone as a working man, thus prompting the connection between human and phone features) but also metonymic (whereby the properties of a working man, e.g., strength and resilience, are mapped onto the phone, but without necessarily understanding the phone as an animated being); however, we are fully aware of the ambivalence of such a figurative mechanism as personification.

A question that remains unanswered is whether the improvement in the agreement between analysts was due to practice over rounds of annotations, or whether the constraint on narrative range in mobile phone advertising was the factor that made it easier to spot metaphors and metonymies. To address this, we break down the rounds by type of advertisement (rounds 1–3 for generic advertisements and rounds 4–6 for genre-specific advertisements) to explore the trends by advertisement type (RQ2 and RQ3).

5.1.2. Headline finding: the specificity of mobile phone advertisements makes it easier to spot metonymy, but not metaphor

With regard to metaphors in generic advertisements (rounds 1–3), analysts did not converge much in their responses, but practice helped to raise agreement in their annotations by the end of round 3 (r = 0.87). The really interesting pattern appears when we compare the performance for metaphor and metonymy in mobile phone advertisements (rounds 4–6). As shown in Figure 11, the performance for metaphor and metonymy identification followed opposite trends in rounds 4–6 for mobile phone advertisements. Although the agreement was higher at the beginning for metaphor than for metonymy (ᴋ = 0.7 and ᴋ = 0.6 in round 4), the kappa scores for metaphor decreased by the final round, whereas it increased to perfect agreement for metonymy (ᴋ = 0.6 and ᴋ = 1 in round 6).

Figure 11. Evolution of inter-rater reliability by figurative language type by advertisement type and across rounds.

Overall, the analysts reached moderate to substantial agreement in their annotations of metaphor and metonymy in mobile advertisements; still, a closer look at the Pearson’s correlation coefficient shows a strong positive relationship (r = 0.87) between observed inter-rater agreement and rounds of annotation for metonymy, meaning that researchers got better in agreeing upon their interpretations of the advertisements, but a weak negative relationship in the case of metaphor (r = −0.24). This is probably due to the fact that there are some overarching metonymies that tend to appear in advertisements about phone apps (e.g., a musical note that stands for playing music, in Figure 12), phones (e.g., a human hand next to a phone that stands for ownership over the phone), or data plans (e.g., portraying a SIM card to prompt Internet browsing).

Figure 12. Advertisement for EE mobile phone network (Text: “More beats per minute. Download albums superfast with mobile #4GEE. Only on EE.”).

For the case of metaphor, agreement decreased in the sixth round of annotation (even though it was still higher than for generic advertisements) because some of the advertisements from the mobile corpus contained several overlapping messages. This made the researchers pick different structuring verbalizations of the advertisement, which had consequences for the identification of the main metaphor at work. It highlights a creative license that makes advertisements more engaging as they allow for multiple valid readings of the same campaign; but that naturally hinders the success of our task, which for the sake of practicality was restricted from the beginning to the identification of a single ‘main’ structuring metaphor. In order to illustrate this, see Figure 13 where phone size correlates with the power of the phone to get more information; a visual manifestation of IMPORTANCE IS BIG (Yu et al., Reference Yu, Yu and Lee2017). But here the ‘bigger picture’ can also be taken literally, since the size of the screen is larger too, and therefore both literal and figurative readings apply.

Figure 13. Advertisement for Blackberry phone (Text: “Work narrow. Work wide. See the bigger picture.”). ©2014 BlackBerry Limited. BlackBerry Passport® smartphone advertisement is used with permission from BlackBerryLimited. All Rights Reserved.

5.2. Study 2. Interpreting multimodal metaphor and metonymy

In Study 2 we assessed the extent to which we agreed on the interpretation of the advertisement by triangulating the qualitative information provided in our respective verbalizations of the main message of the advertisements (stage 1), our annotations of what we perceived to be the product being advertised (stage 2), and what was being said about it (stage 3). The difficulty of this task is that, whereas we might have a general feel that the product is being compared to something else, sometimes highly creative and complex advertisement designs make it hard to discern what the actual ideas are that are being connected via metaphor or metonymy.

5.2.1. Headline finding: it is easier to agree on the interpretation of metaphors rather than of metonymies, although the higher specificity of mobile advertisements lowers the agreement scores for both figurative operations

Figure 14 demonstrates the evolution of agreement between the interpretations for advertisements featuring metaphor and metonymy in both generic and mobile advertisements made by both analysts over the six rounds of analysis. Although similar interpretations were overall more frequent than partially similar and dissimilar interpretations for both metaphoric and metonymic advertisements, both analysts were likely to converge more in their interpretations for metaphor (82% of coincidence on average) than for metonymy (54% of similar interpretations on average). In other words, it was easier to have a similar interpretation of the advertisement if it was based on metaphor. Supporting evidence can be found in the evolution of different interpretations that decrease across the three rounds for metaphoric and metonymic generic advertisements, as well as the low rate in mobile advertisements, but increase for metonymic mobile advertisements. One possibility that may explain the increase of different interpretations of metonymic advertisements in the mobile corpus is that it was usual to find multiple co-existing metonymies supporting a main metaphor, which sometimes led the researchers to pick up on different (yet still viable) cues to the metonymies (based on the main image, words, typography, background color, etc.).

Figure 14. Evolution of agreement in the interpretations by figurative language type, by genre, and across rounds.

Interestingly, the advertisements that led to partially similar or different interpretations in mobile advertising were more likely to convey abstract messages, such as data plans, or were campaigns promoting the company. Similar interpretations were more likely to be reached for advertising products of a more concrete nature, such as phone handsets. Finding ways to encode an abstract idea in images is a challenging task that makes advertisers resort to creative strategies that sometimes make the advertisement harder to work out.

We identified two major reasons why metaphor and metonymy interpretation in mobile phone advertisements could have been more difficult than in generic advertisements. First, regarding metaphor, sometimes the narratives set up complex scenarios to shed light on a hard-to-depict service, such as top-up plans. In Figure 15, the advertisement is connecting the idea of topping-up with the game of duck-fishing – a game typically found at a fairground, where prizes are found on the underside of the duck once it has been caught. Although these ideas are sufficiently distinct to be connected via metaphor rather than via metonymy, viewers may pick up on different cues to work out the message that top-up plans have surprising rewards associated with ducks. Indeed, the analysts came up with two related, but different, interpretations: on the one hand, phones are like rubber ducks, and there is a surprise when they are topped-up or caught; on the other, topping-up can be understood as the act of duck-fishing (game), a metaphorical mapping that shifts the focus from the object to the action. The verbal part of the advertisement does not clarify things, as it refers both to surprises “of all sizes” (hinting at the different sizes of the ducks) and to “top-up.” Although both analysts identified the same frames for both the metaphorical source and the target domains, they picked up on different multimodal cues to extract the ideas being compared in the metaphoric mapping. In this case, we marked the interpretation as different, as neither the source nor the target domain coincided in the two possible readings of the advertisement.

Figure 15. Advertisement for O2 network (Text: “Surprises of all sizes every time you top up”).

The second reason has to do with metonymies. We have mentioned that some metonymies can be treated as ‘usual suspects’ in mobile advertising, as they are likely to appear across different campaigns. An example of HAND FOR OWNER can be seen in our previous analysis of Figure 2, a very recurrent metonymic mapping in mobile advertisements. However, the hand is depicted in the shape of a fist bump, which evokes more concrete connotations than a hand holding a phone. A fist bump has multiple meanings depending on the cultural knowledge or prior experiences; it may cue respect, power, a greeting, happiness, or belonging to a community. The multiplicity of part-whole mappings makes it harder to interpret the same metonymic mapping. Whereas this might not be a problem for advertisers, as they may intend audiences to consider the advertisement as a whole, it may be a challenge for this study as it makes it hard to agree on what message is intended by the advertisement.

6. Conclusion

In summary, our study tests the reliability of an annotation procedure that allows the systematic analysis of multimodal metaphor and metonymy, and suggests that identification may become easier after practice. The second study reported agreement on the actual interpretation of metaphors and metonymies by means of reliability analyses.

Our two studies have shown that a systematic stepwise procedure and inter-rater reliability tests can help to improve the consistency of the identification of metaphor and metonymy in multimodal contexts (RQ1). We reached moderate to substantial agreement in identifying the potential for a metaphoric and/or metonymic interpretation of the advertisements (Study 1), but not so much for the interpretation of such mappings (Study 2), as we did not always pick up on the same multimodal cues to work out the frames connected via figurative mappings. Metonymy was, to a certain extent, harder to identify, mostly for two reasons: (1) part-whole connections are sometimes difficult to disentangle, which makes metonymies sometimes border the literal; and (2) in some cases, it is harder to decide what the main metonymy is, as we usually find several at work providing economic points of access to a main metaphor.

In response to the issue of genre (RQ2), we did find that some metonymies were highly pervasive across mobile phone advertising, which confirmed our hypothesis that knowing the specificities of the genre at work may be useful to ‘train’ the eye for spotting metonymies. However, besides personification, we did not find any recurrent metaphors in mobile advertisements, and therefore genre did not play any role in raising agreement for metaphor identification and interpretation.

Finally, we found evidence to support our hypothesis that reliability increases with analysts’ experience gained with practice (RQ3). We found that we improved the consistency between our annotations for the potential of a metaphoric or metonymic reading of the advertisements (Study 1), but not so much for the selection of the domains connected via such figurative mappings (Study 2). We sometimes struggled to decode the more sophisticated advertisements for phone companies and data plans, given that companies had to find ways to depict abstract services in concrete, visual ways. Therefore, in the process of identification and interpretation of metaphor and metonymy, it is crucial to have training rounds to clarify issues before starting the actual annotation, to hold group discussions of controversial examples to revise the procedure, and to be patient as the evolution in the agreement does not always follow a linear fashion. Ultimately, we need to acknowledge that there is a threshold that cannot be surpassed given the inherent subjectivity of the task, and analysts must consider joint annotation and discussion.

We posit that our take on the identification of multimodal metaphor and metonymy has a number of benefits to the field of figurative communication and multimodality in that it:

-

a) is sympathetically timed with the rise in multimodality research to further our understanding of multimodal figurative communication;

-

b) builds on existing procedures with new empirical research; and

-

c) acknowledges metonymy as a cognitive and linguistic operation in its own right, and provides a framework from which more empirical research on multimodal metonymy in discourse can be conducted.

While we do not have a definite answer to the initial question driving this article, ‘What should count as a multimodal metaphor and metonymy?’, our studies have shed light on the fact that the distinction between metaphor and metonymy goes far beyond the traditional definition based on cross-domain and internal-domain mappings. A procedure for multimodal metaphor and metonymy identification and interpretation should at least address the following issues (and should therefore be taken up by further research):

(a) The gradability of metaphor, or metaphoricity (Dunn, Reference Dunn2015; Hanks, Reference Hanks, Stefanowitsch and Gries2006; Müller, Reference Müller2008), as the boundaries between metaphor and metonymy are sometimes blurred. We have seen that in the case of personification, where two readings are feasible (Dorst, Reference Dorst2011), and in the case of multiple metonymies that provide concrete points of access to a more abstract metaphor, it makes up a composite that is sometimes hard to disentangle (see Goossens, Reference Goossens, Dirven and Pörings1990; Ruiz Ruiz de Mendoza, Reference Ruiz de Mendoza and Barcelona2000; and Pérez-Sobrino, Reference Pérez-Sobrino2017 for a multimodal application).

(b) The role of background knowledge the individual analyst has on a topic/genre to perceive a given metaphor as figurative or not. In our case, revising the corpus of mobile phone advertisements in advance was helpful to clarify doubts about unknown terminology or phone features, and also to spot (and discard) some genre-specific metonymies that were pervasive across mobile advertisements.

(c) The stylistic ways by which similarity is cued in non-verbal contexts, where there is no “is” or “is like” text to flag the metaphoric mapping (Forceville, Reference Forceville, Forceville and Urios-Aparisi2009b: 31). In our studies we looked at the conceptual incongruity between the product and the surrounding context, and/or the text or images next to it.

Funding statement

The present study has received funding from the following research projects funded by the State Agency of Research: Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (PID2020-118349GB-I00 and PID2021-123302NB-I00) and the Government of Aragón (LMP143_21). Ford is funded by the Midlands4Cities Arts and Humanities Research Council (AH/R012725/1).