INTRODUCTION

In his classic study, Abnormal types of speech in Nootka (1915/Reference Sapir and Mandelbaum1968), Edward Sapir details how speakers of Nootka (now known as Nu-chah-nulth), a native Wakashan language spoken on North America's Pacific coast, engage in ‘consonantal play’ to expand or contract the meanings of morphemes to index a whole range of social types. This includes altering certain consonants, or inserting otherwise ‘meaningless’ consonants, within the morpheme (1915/Reference Sapir and Mandelbaum1968:181). For instance, the so-called ‘diminutive’ suffix, while certainly indexing a person who is abnormally small, may also, through a slight addition or variation of sound, index those with eye defects, hunchbacks, jokers, those who are crippled, or left-handed people. In some contexts, the range also expands to include bears, the elderly, and cowards (1915/Reference Sapir and Mandelbaum1968:183–84). Sapir suggests that for Nootka speakers, ‘notions of mere smallness, of contempt, of affection are doubtless found side by side… the precise nuance of the feeling depends on the relation between the speaker and the person addressed or spoken of’ (1915/Reference Sapir and Mandelbaum1968:184).

According to Sapir, several different, yet interlocking features imbue the diminutive suffix with meaning. First are the articulatory movements themselves; consonants that otherwise would be ‘meaningless’ attain precise semiotic qualities in the practice of sound play, a phenomenon later explored under the rubric of ‘sound-symbolism’ (Hinton, Nichols, & Ohala Reference Hinton, Nichols and Ohala2006). Yet equally important for Nootka speakers is the ‘feeling’ that emerges in the utterance of the morpheme itself beyond the quality of ‘smallness’, encompassing morally laden affective stances such as ‘contempt’ or ‘affection’. Finally, Sapir points to the indexical relation between speaker and addressee, or speaker and the subject of the utterance. These inter-related processes through which sounds are creatively combined to express quality, feeling, and the social ‘nuance’, result in the interactional production of what Sapir classifies as the ‘abnormal type’.

In the following discussion, I extend Sapir's observations to the now increasingly discussed word class known as expressives, also called ideophones or mimetics.Footnote 1 Expressives, previously seen as a ‘marginal’ to grammar proper, are now the subject of a vibrant field of research that cross-cuts disciplines such as linguistics, anthropology, literary studies, and even biology (Dingemanse Reference Dingemanse2018; cf. Feld Reference Feld1982/2012; Nuckolls Reference Nuckolls1996; Voeltz & Killian Hatz Reference Voeltz and Kilian-Hatz2001; Kohn Reference Kohn2013; Hiraga, Herlofsky, Shimohara, & Akita Reference Hiraga, Herlofsky, Shinohara and Akita2015; Webster Reference Webster2015; Haiman Reference Haiman2018). Challenging the conventional notion of expressives as sound-symbolic words (or onomatopoeia), Dingemanse, in a review of recent research, defines expressives as ‘marked words that depict sensual imagery’ (Reference Dingemanse2012:655). He suggests that, contrary to ordinary language that tells about events, expressives ‘show’ the event at the very moment of use. For instance, he contrasts what he calls the ‘descriptive’ statement, ‘the person walking with a limp’, with the Siwu (Niger-Congo) expressive tyád̦tyaḑ̣i, depicting the sensual, embodied figure of a person limping as they walk (Dingemanse Reference Dingemanse2012:655).

Drawing from Sapir's original notion of the ‘abnormal’ type, I challenge this descriptive/depictive dichotomy by arguing that expressives not only show speakers’ sensual engagement with the world around them, but also relate relevant information about how speakers ‘evaluate a semiotic repertoire (or set of repertoires) to specific types of conduct’ (Agha Reference Agha2007:147). Drawing on fieldwork conducted among Mundari speakers, an expressive-rich language spoken in eastern India, I suggest that expressive meaning displays a ‘consubstantiality’ (Friedrich Reference Friedrich1979) between the semiotic processes of ‘rhematization’ or perceiving indexes as icons (Sicoli Reference Sicoli2014; Gal Reference Gal and Coupland2016), and ‘dicentization’ or perceiving icons as indexes (Ball Reference Ball2014). This dense semiotic complexity, actualized through multimodal performative acts, contributes to what Streeck, in his study of depiction, has called the creation of ‘model-worlds’: a ‘topical universe that organizes the interlocutor's imagination of the narrative scene’ (Streeck Reference Streeck2008:294). The every-day model-world making enacted by expressive use renders indexical relationships with social Others and the environment as felt iconicity, but simultaneously places this relation in contiguity with the material world, thereby changing its meaning. The twin processes of perceiving indexes as icons and icons as indexes as embedded in expressive depiction challenges conceptual boundaries between language, the body, and materiality (Cavanaugh & Shankar Reference Cavanaugh, Shankar, Cavanaugh and Shankar2017; Irvine Reference Irvine2017). Far from simply an ephemeral part of conversational usage, the model worlds invoked by expressives in everyday use perdure, this article suggests, through their intertextual relations with the narratives, stories, and songs that populate Mundari speakers’ landscapes.

MUNDARI EXPRESSIVES

Mundari is an Austro-Asiatic language spoken primarily in the hilly regions of eastern India, mostly within the Indian state of Jharkhand, although scattered communities can be found throughout other states of eastern India such as West Bengal, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, and Assam. While referring to themselves as ‘Munda’ to outsiders, in Mundari, speakers call fellow community members simply hoŗo ‘people’ as opposed to diku ‘outsider’. Speakers primarily reside in rural villages adjacent to the heavily forested regions of eastern India, and depend mainly on agriculture, the gathering of forest produce, and seasonal migrant labor as a livelihood. According to 2011 census data cited by Ethnologue, there are approximately 1.17 million speakers. Mundari has four major varieties: Hasadaʔ, located in eastern Jharkhand state; Naguri, spoken on the western side; Tamaŗia, spoken in the south and also into West Bengal and Orissa; and Keraʔ spoken in and around Ranchi, the capital city of Jharkhand, mostly by ethnically Oraon tribes, who also comprise of Dravidian Kurux speakers (Osada, Purti, Badenoch, & Choksi Reference Osada, Purti, Badenoch and Choksi2015:1). Many (though not all) Mundari speakers are bi-or multilingual, speaking Indo-European varieties such as Hindi, Nagpuri, and Bengali and other neighboring Austro-Asiatic languages, such as Santali or Ho.

Like other Austro-Asiatic languages (Diffloth Reference Diffloth, Thongkun, Panupon, Kullivanajaya and Kalaya1979; Sidwell Reference Sidwell and Williams2013), Mundari has a rich expressive repertoire (Osada Reference Osada and Nagaraja2010; Phillips & Harrison Reference Phillips and David Harrison2017). Mundari expressives are formed primarily through either full or partial reduplication, and what distinguishes them according to Osada (Reference Osada and Nagaraja2010) is that unlike for the ‘echo words’ ubiquitous in South Asian languages (Abbi Reference Abbi1985; Mohan Reference Mohan2006), in expressives, neither the ‘stem’ nor the ‘reduplicant’ has any independent meaning. For instance, in the Mundari expressive jiki-miki ‘rippling and glittering water’ (Osada et al. Reference Osada, Purti, Badenoch and Choksi2015:272), neither jiki nor miki has a meaning independent from its use in the expressive pair. This contrasts with other forms of reduplication in Mundari, such as verbal reduplication, e.g. jom-jom ‘eating again and again’ or jo-jom ‘eat-emph’ from the verbal base root jom ‘to eat’. In addition to their morphology, expressives also exhibit flexible syntactic behavior, occupying predicate, argument, or complement positions interchangeably (Osada et al. Reference Osada, Purti, Badenoch and Choksi2015:272). Expressive use is not genre-specific; the constructions occur frequently both in everyday conversation and in performative genres like songs and stories. While their occurrence is not remarkable, the markedness of expressive constructions, which includes the flexibility of their morphology and syntax as well as the specificity of their semantics, lends them to be easily detachable from everyday speech, creating conditions under which they can be subject to metapragmatic discussion (Silverstein Reference Silverstein1981).

DATA AND METHODS

The following data was taken as part of a two-year collaborative project sponsored by the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science between researchers from Japan and India on the comparative study of expressives in Asian societies. Mundari was selected as one of the subjects of this study in part because, as an Austro-Asiatic language of South Asia, insights from Mundari can also be extended to Southeast Asia, the linguistic area where Austro-Asiatic languages are more prevalent. In addition, there was the added benefit of having a native Mundari speaker, Ms. Madhu Purti, a resident in Kyoto, Japan where the project was based, as well as the support of senior researcher Toshiki Osada, who has written one of the few contemporary grammars of Mundari (Osada Reference Osada1992) and several important articles on aspects of Mundari linguistics (Osada Reference Osada1999; Evans & Osada Reference Evans and Osada2005, Reference Evans, Osada, Evans, Gaby, Levinson and Majid2011). In addition, Osada, Purti, and Nathan Badenoch, a researcher also based in Kyoto who specializes in Austro-Asiatic languages of upland southeast Asia, have produced the first full-length dictionary of expressives in Mundari, A dictionary of Mundari expressives (henceforth DME; Osada, Purti, Badenoch, Onishi, & Dutta Reference Osada, Purti, Badenoch, Onishi, Datta, Badenoch and Osada2019).

I was fortunate to be resident in Kyoto on a fellowship for two years from 2016–2018 and, as part of my stay, had the opportunity to work closely with Badenoch and Purti on a research project documenting Mundari expressives. As part of the project, Badenoch and I first elicited several expressives pertaining to common everyday themes and sensory perception in consultation with Purti. Then we sat down with Purti over two sessions in Kyoto to discuss the finer nuances of the expressives that we believed to have very similar meanings. We conducted these discussions in Mundari, although at some points Purti would switch into Japanese or Hindi for further clarification. In order to capture the multimodality of expressive meaning, we also decided to video record these discussions. While our initial sessions sought to elicit basic definitions, Purti elaborated the expressive meaning through gestures, examples of sentences, and, notably, by outlining the contexts of appropriate use. Though we began by focusing on sense-based meanings, we soon realized that Purti's vivid depictions contained much more than references to sensual experience. In order to convey the appropriate contexts of use, she routinely linked these sensual qualities to a delineated range of social types who embodied these expressives. In fact, she would frequently explain the meanings of the expressives with reference to these social types, emphasizing that the grasp of which social types could appropriately embody or materialize the expressive was as important to understanding the semantics as apprehending the sensual perceptions that these expressives were meant to convey. As our conversations in the lab progressed, both Badenoch and I quickly realized that Purti was deploying multiple modes of explanation, including narrative, song, reflection, and evaluation, to create a cultural landscape populated by ethical subjects (Badenoch, Purti, & Choksi Reference Badenoch, Purti and Choksi2019).

Following the initial data elicitation sessions in a controlled setting in Kyoto, far from the areas in which Mundari is spoken as a language of daily activity, I accompanied Purti on a two week field trip to her native village in Khunti district, Jharkhand in eastern India. The village is located on a recently paved road in a hilly and forested region. It comprises of three hamlets, all of which contain members of the Hasapurti clan, and all of who are native speakers of the Hasadaʔ variety of Mundari. At the time of research, the village had no running water, irrigation, or electricity, and most people's livelihood was based on seasonal agriculture or migrant labor. Younger residents were bilingual in Hindi or Nagpuri, although much of the older generation was monolingual in Mundari. Most members of the older generation had not been to school; among those in their thirties and younger, the majority had at least a primary-level education.

As part of the field session in the village, I sat with Madhu Purti, her mother, who was elderly in her upper sixties, and her sister-in-law, who was younger (in her upper thirties). I was also occasionally joined by some of Purti's cousins. As the visit coincided with the spring festival day of Holi, most everyone was around the village and rice beer (ili) had been served early, creating a generally festive atmosphere. The session was conducted in a similar fashion to the Kyoto session, in which I prepared a list of a few expressives, and then offered them as a subject for discussion among the participants. The elicitations were conducted in Mundari and video-recorded. However, unlike the lab session that was more explanatory in nature and took place in an environment removed from everyday language use, the village session offered much more opportunity for the expressive ‘model worlds’ to be elaborated. In this setting, where the expressives were tightly linked with the landscape and social environment, one could see how speakers multimodally craft and orient the topical universes of expressive depiction, bringing in aspects of the social and material environment. These depictions, with their dense elaboration of iconic and indexical signification, have the capacity, as Webster notes in a similar elicitation study of Navajo expressives, to ‘seduce’ interlocutors into a world of meaning (Webster Reference Webster2017).

‘EATING’ EXPRESSIVES

As Nuckolls points out, verbs depicting ‘bodily activities’ such as ‘eating, drinking, swallowing, etc.’ (Nuckolls Reference Nuckolls2012:5) commonly accompany expressive use. Due to the commonality of these words, as well as what we thought were the relatively simple semantics of such expressives, Badenoch and I began our initial consultations with Purti with expressives depicting various actions of ‘eating’, hoping it would then lead us to more semantically complex depictions. Yet even at the outset, in addition to embodying the expressive, and foregrounding the particular sense components involved in its depiction, Purti immediately linked the particular expressives to a delimited range of social types for whom the expressive could be appropriately applied. This additional ‘nuance’ revealed for all of us, sitting in an office in Kyoto, Japan far from the hills of eastern India, a ‘model world’ that illuminated perceived social relations between types of humans and nonhumans as well as material objects.

Lugum-lugum

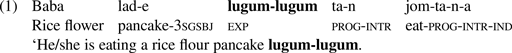

The first expressive that was elicited was lugum-lugum, which DME glosses as the ‘appearance of chewing with cheeks puffing in and out’ (Osada et al. Reference Osada, Purti, Badenoch, Onishi, Datta, Badenoch and Osada2019:189). When asked what this expressive meant, Purti immediately puffed up her cheeks, putting her lips together, and started chewing. This visual act, in combination with the sound of ‘silence’ made as the lips came together inaudibly, created a diagrammatic icon that the speaker enacted through her body. The embodied depiction was followed up with a single gloss, showing how the expressive may be used in a sentence.Footnote 2

As Purti had worked on expressive elicitation previously, she was experienced enough to know that prevailing ideologies of expressive glossing primarily sought to connect expressive meaning with sense-imagery. Hence, she foregrounded the iconic aspects of the expressive: both her diagrammatic embodiment of the expressive as well as its imagistic use in a simple utterance. However, like the Nootka speakers in Sapir's study, Purti was not satisfied that this explained what to her was the expressive's core meaning. She elaborated, saying that this motion was characteristic of ‘toothless human individuals’, which encompassed social types such as ‘babies’ and the ‘elderly’. She clearly also restricted the domain, saying that the expressive would not be appropriate for nonhumans who make similar silent chewing sounds such as cows. The social types expressed by Purti created an indexical correspondence between ‘babies’ and the ‘elderly’, uniting the opposite ends of a human lifespan. These correspondences were iconically depicted in the use of the expressive itself.

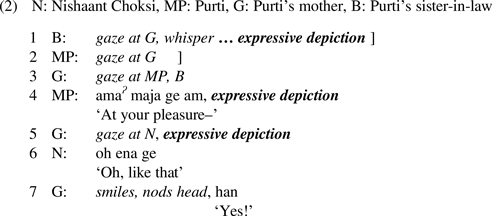

In order to corroborate this explanation, I elicited this expressive once again in the village, where Purti (MP) was joined by her younger sister-in-law (B) and her elderly mother (G), who, as is characteristic of most of the elderly in rural societies without regular access to dental hygene or dentures, was missing most of her teeth. As I brought up the expressive lugum-lugum, both MP and B both looked over at G, while modeling a silent chewing motion (expressive depiction).

The above excerpt shows how gestures such as gaze are critical to build up the meaning of the expressives in everyday use (Nuckolls Reference Nuckolls1996; Mihas Reference Mihas2013; Dingemanse Reference Dingemanse2013). When the expressive was brought up, both B and MP looked at G and modeled the expressive gesture (lines 1–4). In doing so they were embodying the expressive, but also indexing through their gaze the appropriate social type to ‘voice’ the expressive, which was G. In line 5, G responds to the change in footing by accepting the role assigned to her by the other participants (Agha Reference Agha2005), and depicting the expressive for the researcher. Having adequately depicted the expressive by ‘align[ing]-by-becoming-the-same-as’ (Nuckolls Reference Nuckolls2010:33), G smiles and enthusiastically responds to the researcher with a ‘Yes!’ (line 7). Supported and coordinated by other speakers, G's actions in line 7 bring to life the model world invoked by MP in the lab. This model world, however, would have also likely been inspired by MP's own experience and memories of interactions with real ‘toothless’ people in her life such as her mother (G) back in the village, who, for MP, renders real the social type before it is even expressed to the researcher as an abstract depiction.

Sar-sor

The next eating expressive elicited was sar-sor, glossed in DME as ‘noisy eating with slurping sounds’ (Osada et al. Reference Osada, Purti, Badenoch, Onishi, Datta, Badenoch and Osada2019:232). While the definition foregrounds auditory imagery, during our elicitation session, Purti instead chose to gloss the expressive with an analogy to a social type, ‘pig’, saying “sukuri ko leka”, like pigs, “sar-sor”. After that she began to smack her lips loudly, creating a sucking sound, followed by moving her head back and forth, sniffing with her nose, and ending with a loud snorting sound. In her depiction, motion and sound imagery were foregrounded, yet the depiction was only made possible when the consultant aligned herself with the social type being depicted, namely a ‘pig’.

While sar-sor is appropriate as a way for a pig to eat, I asked her next about what if the agent were a human person (hoŗo). She replied that yes, humans can also eat sar-sor under certain circumstances, for instance, if they are eating something that is too ‘hot’ for consumption (“lolo chij sar-sor ta-n jomoʔ -a” ‘hot things are eaten sar-sor’) She cited an example of the common Japanese practice of slurping a hot bowl of ramen noodles, which, while appropriate in Japan, would be inappropriate in a Munda context. The expressive instantiates a diagrammatic correspondence between ‘human’ and ‘pig’; people who eat sar-sor do not simply ‘eat like a pig’ in an analogical sense, but embody the nonhuman agent. However, Purti also understands this iconic relationship between human and pig as an index of a specific cultural context. Hence, a ‘Munda’ person and a ‘Japanese’ person in Purti's discussion are delineated as two separate social types, where the qualities embodied are subject to differing social evaluations.Footnote 3

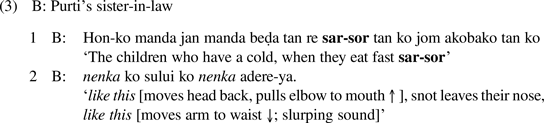

This already populated model world became further elaborated during the village fieldwork. MP's sister-in-law (B) agreed with MP's negative evaluative framing of sar-sor by saying that those adult humans who ate sar-sor ate ‘carelessly’ (“manḍi ko-m hopora ka re aun ge sar-sor ta-n jom-e-ya” ‘they who eat rice without care, they eat sar-sor’). Rather than comparing the agent with a pig, MP and B, who were now sitting at a home surrounded by B's small children, chose to invoke the figure of the ‘snotty-nosed child’. B elaborated through a multimodal depiction, shown below in (3).

Just as MP embodied ‘pig’ in the lab, B ‘becomes-the-same-as’ a sniffling child who is suffering from a cold. Her gesture brings in the material aspect of the expressive meaning, in this case, the liquid ‘snot’ (sului) that flows out her nose, which she then slurps back in. The gestures are indexically anchored with the deictic nenka ‘like this’, which appears twice in a poetic chiasmus within the utterance itself, orienting focus on the many layers of contrast involved in the expressive depiction. These contrasts also correspond to the phonic alternation in the vowels (a/o) in the expressive form itself, revealing a dense semiotic constellation of sound, meaning, and performance.

The model worlds invoked by both MP and B also index a notion of agency that is ‘molded by sociocultural fields’ (Ahearn Reference Ahearn2001:130). In both cases, the moral evaluation of the subject of the expressive action depended on what kind of agency was assigned to the social type, and then whether the cultural context sanctioned such agency. For instance, as I was transcribing the village interaction, I asked MP if ‘snotty-nosed adults’ would also be a relevant social type to eat sar-sor, and she rejected this explanation, saying that ‘for Mundas’, any competent adult would not let snot flow out of their nose like that especially when eating, and if it did, they would be expected to wipe it off. Children, by contrast, like pigs have no control over their manner of eating, nor are they expected to wipe their noses by themselves, and hence, they can eat sar-sor. Since Munda adults are considered to be proper social agents, their eating sar-sor implies ‘carelessness’, not paying attention to whether the food is cool enough to eat properly. This differential notion of agency perceived in the use of morphological forms has been documented in other societies as well, notably in Duranti's (Reference Duranti1994) discussion of ergative use in Samoa.

Sodor-bodor

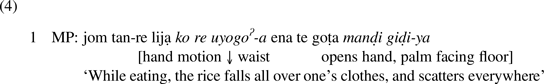

The last eating expressive I discuss here is sodor-bodor, which is glossed in DME as ‘messily eating, pieces of food stuck on lips and face’ (Osada et al. Reference Osada, Purti, Badenoch, Onishi, Datta, Badenoch and Osada2019:238). In the lab in Japan, when Badenoch and I brought up the expressive, MP gave the following explanation, given in (4).

At the outset, we glossed the expressive as encoding the set of gestures referring to ‘eating + spilling’, accompanied by a moral evaluation. This initial understanding contributed to the resulting dictionary definition including the word ‘messily’, which conveys both a style of eating, as well as a negative connotation. Yet only after entering the village did we realize that even in the lab setting, MP was modeling more than simply someone ‘messily eating’; she instead crafted a whole material and kinetic world. For instance, this was the first time in the session that the food itself ‘rice’ (mandi) became a focus of the expressive meaning in the eating expressives we had discussed up to that point. Rice is the staple grain in Munda households, and sometimes the word can be substituted for any meal. However, here, the act of spilling concerned the materiality of the rice grains themselves. In addition, the gestural motion that accompanied the expressive use foregrounded the ‘hand’, creating an indexical connection between the act of eating and a specific body part. This also makes sense with the Munda cultural context since all food is eaten with one's hands.

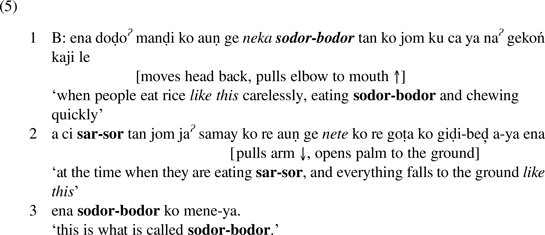

In the village setting, B elaborated on the negative connotations of the expressive sodor-bodor, on one hand, by comparing it to the previous expressive discussed, sar-sor, but, on the other, by foregrounding the central embodied and material aspects of this particular expressive that differentiates its meaning.

At the outset of her discussion of sodor-bodor (line 1), B invokes a similar social type to sar-sor by referring to the agent, presumably a competent adult, as ‘careless’. She then proceeds to create a diagrammatic equivalence between the two expressives by repeating the same gesture along with the deictic neka ‘like this’. The iconic equivalences result in an evaluative stance in which sar-sor and sodor-bodor are interpreted in relation to a normative ideology that regulates the way a body should be comported for social agents in specific situations. B's depiction reveals a dicentization process, whereby a diagrammatic icon that combines gesture and speech is seen as indexical of what Lambek (Reference Lambek and Lambek2010) has called an ‘ordinary’ ethics of everyday activities such as eating. However, while these ethics might seem ‘intrinsic’ to the social activity, the apparent immanence is actually accomplished through the performative and semiotic labor (Lempert Reference Lempert2013) undertaken by combining sound, meaning, and action in the expressive utterance.

While in the first part of the utterance B asserts an ethical framework through which to judge the social type, in the second part she elaborates on the semantic components of the expressive itself. In line 2, she distinguishes sodor-bodor from sar-sor by forming a new indexical-iconic image by moving her hand down and opening up her palm facing to the ground from a fist, while uttering the deictic nete ‘in this way’. Whereas B's depiction of sar-sor drew in imagery of nasal mucous and was concentrated in the upper portion of the body, in sodor-bodor the focus is on the scattering of the material of mandi ‘rice’, on the ground and the palm and fingers in the lower part of the body. This contrasts to the definition given in the DME in which the focus is on ‘rice’ stuck to the ‘lips’ and ‘face’.

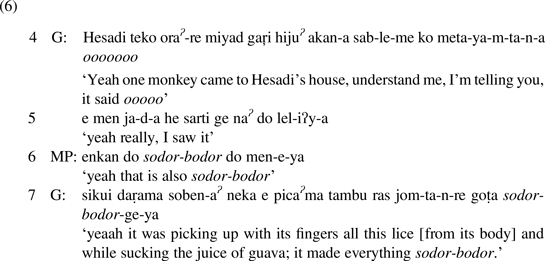

After B spoke, G stepped in to recall an experience that occurred the day before at her neighbor's house where she encountered their pet monkey.

On first hearing G's anecdote, I was initially confused. At both the lab settings and the village discussions, the use of sodor-bodor involved exclusively adult humans as social agents. Yet G's narrative involved no humans at all. In line 4, she aligns herself with the agent of the expressive, the monkey at Hesadi's house, by imitating the monkey's high-pitched squeals, ooooo. Immediately, without even going into the monkey's actions itself, MP suggests in line 6 that this was also an example of sodor-bodor. G went on to depict the expressive action by narrating how the monkey picks up lice with its fingers and sucks on guava juice.

As I did not fully understand the episode during the actual conversation, and it moved quickly to another topic, I followed up with MP during the transcription process back in Kyoto. I asked her why this episode was considered by both her and G as clearly depicting sodor-bodor and what implication it had for the social type. For instance, if a monkey could eat sodor-bodor, could other animals too, such as a chicken or a dog? MP categorically rejected this, saying that only humans and monkeys could eat sodor-bodor, as only both of them have hands with fingers. This is when I realized that the act of grasping with fingers and then scattering and making a mess below was critical to the uptake of the meaning, and that fingered creatures, which in Munda villages meant monkeys and humans, constituted the proper social agent of the expressive. To specify this ‘fingered’ aspect of the social type that led to the monkey being sodor-bodor, G used the word pica ‘plucking with fingers’ in line 7. This specification would not be necessary to humans eating, since, as mentioned above, it is assumed that humans eating would use their fingers. In addition, the monkey was not ‘careless’, but the disgust was more at the effect of the action rather than an evaluation of the agency of the monkey itself. Moving beyond both conventional sound symbolism and sense-perception frameworks, G's narrative imbues the expressive with further pragmatic potency when it is employed to describe human beings: eating sodor-bodor is akin to a monkey scattering its own lice.Footnote 4

EXPRESSIVE DEPICTION IN NARRATIVE AND SONG

In the second part of his ‘Abnormal types’ essay, Sapir noticed that the ‘consonantal changes’ observed in the invocation of Nootka abnormal types are ‘rhetorical or stylistic as much as grammatical. This is borne out by the fact that quite analogous processes are found employed as literary devices in American myths and songs’ (Sapir 1915/Reference Sapir and Mandelbaum1968:186). For instance, Nootka relate the mythological characters Mink and Deer as talking like those who have a ‘defect of the eye’ (187). Sapir's work initiated a long tradition of investigation, particularly in the Americanist tradition, into the way in which sound play and sound symbolism came to mark narrative characters, which then could serve as frames for the subsequent interpretation of linguistic form. For instance, Hymes (Reference Hymes1979) investigated Sapir's study of talking ‘like a bear’ in Takelma, another language of the Pacific northwest, suggesting that the expressive prefix ‘l’ or ‘s’ that Sapir associated with ‘Bear’ in Takelma narratives actually extends to a range of social types, such as ‘old person’, ‘mother’, or ‘foreigner’. Silverstein (Reference Silverstein, Hinton, Nichols and Ohala2006) and Webster (Reference Webster2017) demonstrate how expressive meaning is negotiated and modeled on mythological characters in Native American languages Wasco-Wishram and Navajo, respectively. These models, which are so pervasive for speakers that they can only be understood through an intertextual analysis, create, as Silverstein suggested, a ‘pragmatic metaphorical set’ that shapes the belief that forms have an inherent ‘denotational iconicity’ in speaker understanding (Silverstein Reference Silverstein, Hinton, Nichols and Ohala2006:41).

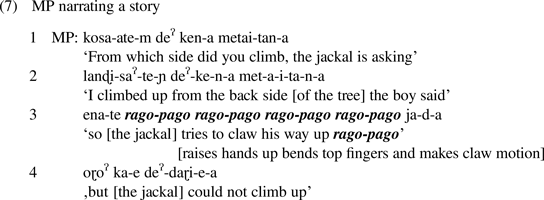

In their introduction to a special issue on expressive pragmatics, Lahiti, Barrett, & Webster (Reference Lahti, Barrett and Webster2014) emphasized expressives’ unique role as occupying a special place somewhere in between ‘grammar and poetry’, asserting that ‘any typology of ideophones [expressives] must take into account their “performativity and poetic potential” ’ (Lahiti et al. Reference Lahti, Barrett and Webster2014:335–36). Consequently, in the lab work in Japan, in addition to elicitation along the lines presented above, narratives and songs were elicited to draw out how expressives were being negotiated in performance. For instance, in the narrative below in (7), Purti is relating how a jackal is trying to claw its way up a tree to attack a young boy.

In these kinds of performances, the formal narrative structure already offers the audience a framework for interpreting the expressives, contrasting with the more seemingly ephemeral model worlds created in the elicitation sessions, both in the lab and in the village. Yet, in a subsequent analysis, Badenoch, Osada, and I (Badenoch, Choksi, & Osada Reference Badenoch, Choksi, Osada and Mohan2020), found that often when expressives appeared, they were somehow marked, either, as in (7) above, by gesture and repetition, or with altered phonation or echo effects within the utterance itself. While the purpose of these recording sessions was simply to elicit Mundari narrative texts (not highlight expressive use), our analysis shows Purti often foregrounding expressives through such multimodal poetic markers. This suggests that the expressives are ‘entextualized’ (Bauman & Briggs Reference Bauman and Briggs1990), creating a segmented world-within-a-world subject to intertextual interpretation, which then conditions the depiction of the social types within the larger narrative.

To take an example from (7) above, Purti uses the expressive rago-pago four times in sequence in line 3, and accompanies it with a gesture where she raises her hands and claws up and down, her hand motion altering between each syllable. In this way, she highlights the visual motion of Jackal, who is trying to repeatedly claw its way up a tree, as well as calling attention to the claws themselves. Yet DME glosses the expressive as the ‘scratching sound of claws on a surface’ and offers the example of a mouse scurrying around (Osada et al. Reference Osada, Purti, Badenoch, Onishi, Datta, Badenoch and Osada2019:215). In the dictionary meaning, the auditory sensation is highlighted, since mice, unlike jackals, are small and unseen. In a subsequent discussion, when I probed further into the meaning, Purti described the expressive as cuing the listener to the motion of any (and only) a four-legged clawed animal. In the performance, this cue is marked by multiple features, such as the repetition of the expressive four times, which, along with the gesture in line 3, appeared repeatedly at different points in the narrative. These processes within the formal structure of the narrative create a dense intertextual web of associations in which sensations are perceived as indexing a social type (dicent) and the indexical social type as iconizing the felt, embodied experience (rheme).

In the lab environment in Japan, performances were elicited in sanitized and demarcated conditions, and were also performed to a camera in the absence of any kind of audience or commentary. However, this changed during the village session when performances were inter-woven with the conversation, and the web of intertextual associations created through a participatory process or what Bolinger (Reference Bolinger1940) called ‘word affinities’. This joint process helped translate, or ‘transduce’ (Silverstein Reference Silverstein, Rubel and Rosman2003), the social types present in ephemeral model words to the more perduring ‘characters’ of narrative or song.

Bijir-Bijir

An example of this kind of performance occurred when the participants and I were discussing the expressive bijir-bijir in the village setting. In DME, bijir-bijir is defined as a ‘repeated flashing of bright light, like lightning in the sky’, and the example sentences include references to lightning flashing (hicir) and sunlight (jeṭe) (Osada et al. Reference Osada, Purti, Badenoch, Onishi, Datta, Badenoch and Osada2019:69). In the laboratory setting, MP offered sunlight and lightning as an important analogical reference point to depict the bright, flashing visual imagery of bijir-bijir; the indexical contiguity between bijir-bijir and lightning subsequently was interpreted iconically as a ‘repeated’ flashing of light.

Yet as I have suggested here for expressive depiction in general, once we exited the lab and entered the village setting, the expressive acquired several new semiotic valences in the interaction between myself, B, G, and MP. For instance, I expected the core meaning of the expressive to have something to do with ‘light’, since this was brought up repeatedly in the previous conversations I had with MP in the lab setting. Yet I was surprised that when I brought it up, G responded to me not with a reference to lightning or sunlight or any other light-producing entities but with another expressive, sãŗae-sõŗoe. As I had never heard this expressive before, I followed up with MP during the transcription process, and she told me that it was the sound of metal clanging together, for instance, when hunters are walking into the forest with their various weapons for the hunt, and the metal objects are clanging together. I asked then about the connection to bijir-bijir. MP responded that metal usually reflects light, therefore G's response, which happened very quickly after the initial inquiry, reflected the complex association, at least in her mind, and readily available to MP's perception, between sound, light, and materiality. As we were discussing the expressives on the day of the annual hunt for Mundas (sendra) the hunting reference made even more sense since some of the men were preparing their weapons to go to the forest that afternoon.

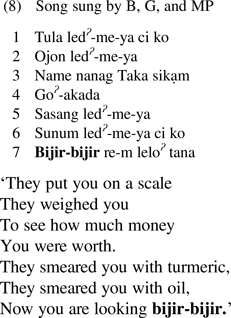

These practices of word affinity are modeled in part through how the expressives appear in performance. Following the discussion of sãŗae-sõŗoe in relation to bijir-bijir, B started singing a wedding song that made use of the latter expressive. The song was well known to both MP and G, who also started accompanying B.

The song references the practice of bride-price in which, after the engagement is fixed, the groom's side offers some money to the bride's family as payment for marriage. At the time of marriage, the bride is readied as families smear her down with turmeric and oil to make her skin shine, and adorn her with new clothes and jewelry.

As is common in many Mundari songs, the expressive bijir-bijir appears in the last line of the verse; the depictive sensual imagery accentuates the performativity of the song and the gleaming, shining figure of a made-up bride. Yet the semantics of bijir-bijir depicted by the performance depends on both the ‘social type’ marked by the bride as she appears in this (and several other) songs, as well as the ‘model world’ created through the use of the expressive at the moment of utterance. In this case, B recounts the song after G already links the expressive with ‘metal’, which I had previously associated with ‘light’, juxtaposing the visual imagery with auditory, and by extension, material imagery. These indexical connections are diagrammatically mapped within the performance text. For instance, in lines 1–3, the first part of the song references metallic objects such as ‘scale’ (tula) and ‘hard currency’ (taka sikam), while the last part refers to the glimmer of the new bride's body due to the application of turmeric (sasang) and oil (sunum). While not mentioned in the song, brides are also associated with metallic jewelry made of silver or gold that will also ‘shine’.

An analysis of the structure of the song text reveals that these affinities are not simply a matter of randomly generated, stream-of-consciousness type word association. Rather these affinities, and the ‘model worlds’ depicted by expressives at the moment of use, often are part of a more entrenched ‘bundling’ (Keane Reference Keane2003) of semiotic qualities that comprise a social type in performance, or a character. In this case, the discussion in most of the song text is predominately of materials that evoke everyday practices such as buying and selling (scale, currency) and cooking or eating (turmeric, oil). The quotidian material references downplay the affective imagery until the culmination, where the expressive foregrounds the momentary ‘flash’ of resplendence of the bride's freshly oiled and turmeric-smeared body and her glimmering, clanging ornaments, as she is about to wed. However, the song text makes clear that the ‘shine’ or ‘flash’ of the bride's body entailed in the expressive is not viewed through an aesthetically transcendent conception of beauty. Instead, the expressive depiction evokes the bride's social ‘value’, and her idealized role fulfillment in a transaction-based marriage system.

CONCLUSION

The preceding discussion addresses the possibilities for moving beyond a focus on sound-symbolic or sense-imagistic understandings of expressive depiction, showing how speakers use multimodal resources available in everyday interaction to link expressive meaning with social types. In doing so, the article suggests that speakers craft model worlds that are populated by ethical subjects, living and nonliving social beings, agents and nonagents, and material objects. These worlds are both indexical, in that they are contiguous with aspects of the larger interactive setting, but also iconic, in that that the speaker and interlocutor ‘become’ the subjects and the sensations depicted by those worlds. The varying perceptions and uptakes between speakers and interlocutors are highlighted through the way speakers coordinate actions such as gesture and gaze.

In addition, while expressives have a reputation of being difficult to elicit and speakers often initially resist pinning down a particular meaning for a word, Mundari-speaking consultants were both highly attuned to the multilayered semiotic process involved in expressive production and perception. This was evident from the fact that they very seamlessly went from embodying a particular expressive through role alignment, to metapragmatically linking an embodiment with a social type, and then evaluating that social type depending on operative ethical and agentive ideologies. Their ease at moving between these different registers and depictive modalities suggests that in other expressive-rich speech communities around the world, elicitation of the type described above could yield a wealth of interesting linguistic and ethnographic information, though this might be threatened by dominant language ideologies that devalue expressive use (Childs Reference Childs1996; Nuckolls Reference Nuckolls2010).

Finally, the article looks at how word affinities, though seemingly momentary or ephemeral, are actually structured and perdure in the narratives, songs, and stories in which expressives appear. The social life of expressives beyond particular interactional moments therefore is an extremely promising area of research. Some research on this end has been undertaken in places like Japan, where expressives have been linked to particular ‘characters’ deployed in marketing campaigns (Occhi Reference Occhi2010:81), or in Korea, where sound shape marking intensity is then commodified and associated with class and gender in advertising (Harkness Reference Harkness2011). Although this study focused on Mundari speakers who are not fully integrated with the market economy, studies in expressive-rich consumer societies such as Korea and Japan demonstrate that expressives and other sound-symbolic activities are clearly linked to materiality and commodity processes (Agha Reference Agha2011; Shankar & Cavanaugh Reference Shankar and Cavanaugh2012) and shape the ‘mimetic faculty’ characteristic of ‘capitalist perceptual modernity’ (Inoue Reference Inoue2007).

The study of expressives, once considered marginal and superfluous to a proper linguistic analysis, is starting to be taken seriously across linguistics, anthropology, cultural studies, and allied disciplines. The rich semantics of expressives, their multimodal dimensions, and their semiotic multifunctionality provide a fertile and yet to be adequately explored field to further enrich a theory of language as social action.