INTRODUCTION

This article addresses the broad question of how narrative mass media can be used by its creators to engage in acts of diversifying and decolonising the everyday language of white racism (Hill Reference Hill2008). Our study contributes to the growing body of sociolinguistic research that recognises that the media have a central role to play in establishing, reflecting, changing, and circulating language ideologies, language attitudes, and sociocultural values (e.g. Queen Reference Queen2015; Coupland, Thøgersen, & Mortensen Reference Coupland, Thøgersen, Mortensen, Thøgersen, Coupland and Mortensen2016; Meek Reference Meek, Samy Alim, Reyes and Kroskrity2020; Craft, Wright, Weissler, & Queen Reference Craft, Wright, Weissler; and Queen2020:396). As Bell & Gibson (Reference Bell and Gibson2011) argue,

performance has opened up, for example, new mediated genres and registers from which linguistic innovations circulate into everyday discourse. Performance encourages reflexivity for both performer and audience, and therefore also leads to the formation of … ‘higher order indexicalities’—awareness that a certain stylistic variant operates as an index for a certain social meaning.

To that end, we ask: how do Indigenous screen creatives index their perspectives and complicate mediated dominant points of view, making apparent ongoing colonialist and imperialist frameworks? How do they ‘decolonise’ white discourse? To begin to address this question, we first introduce the theoretical concepts underpinning our analysis and the corpus that we draw on, before we analyse and discuss a selection of relevant examples from the corpus. In so doing, we examine both overt discourses (metalanguage) and more subtle characterisation, revealing how Indigenous screen creatives counter erasure by diversifying and complicating representations and bringing in Indigenous perspectives through the processes of what we are calling semiotic overlay and erasure marking.

As Lippi-Green (Reference Lippi-Green1997/2011) long ago noted, linguistic differences in staged or scripted media performances matter; spoken language patterns in relation to the kind of character being performed. That is, it is used to enfigure, typify—or stereotype—the image before the hearing viewer. For example, Disney's heroes typically use some assumed standard American variety, while villains (or ‘negatively motivated characters’) often speak some variety of non-US English or foreign-accented English (1997/2011:117–19). The reproduction of such contrasts, to the point of standardisation, results in socialising listeners into an expectation of sociolinguistic difference that then gets mapped onto an axis of difference (cf. Gal & Irvine Reference Gal and Irvine2019). In Disney's case, it is an axis of good vs. evil. Such typified performances and coinciding mappings also flatten the semiotic richness of real-life manifestations, of actual language practices in everyday life. Even if media creatives aim to produce a faithful representation or an ‘authentic’ performance, contrasts become emblematised through non-standardised expressions (How! vs. Hello!), phonological features (-ing vs. -in’), morphophonemic constructions (contractions vs. no contractions), vocabulary (heap vs. very), linguistic forms (me as subject vs. I as subject), and grammatical structures (presence/absence of copula/auxiliary verbs, etc.). While such representational contrasts in and of themselves are not inherently problematic, oppressive, or subjugating, they become powerful and authoritative in relation to the dominant representational economies (Keane Reference Keane2003:41) within which they are formed and circulate, that inform their creation, and through which systems of value become manifest (realised). These contrasts matter for media representations of different types of marginalised peoples, including Indigenous peoples who are the focus of this article.

In the United States, mainstream media representations of Native Americans have historically been negative and stereotyped (Meek Reference Meek2006, Reference Meek, Samy Alim, Reyes and Kroskrity2020; Leavitt, Covarrubias, Perez, & Fryberg Reference Leavitt, Covarrubias, Perez; and Fryberg2015:40), maintaining discourses of ‘lasting’ (as in, the last of X) and endangerment (O'Brien Reference O'Brien2010; J. L. Davis Reference Davis2016) through topics that highlight poverty, health disparities, alcoholism, and trauma.Footnote 1 In addition, Native American television characters have featured so infrequently that some scholars have found it difficult to formally analyse their portrayal (Fryberg & Eason Reference Fryberg and Eason2017:556). Australia has a similar history of problematic representation of Indigenous people, in both fictional and factual storytelling. Whether Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are represented through negative stereotypes (e.g. as villainous, barbaric, inferior, threatening, violent) or through so-called ‘positive’ stereotypes (e.g. as ‘noble savage’), such representations do not only create an Us-Them distinction, they have been used to legitimise unjust or racist actions, laws, and policies (Behrendt Reference Behrendt2016). As such, where non-Indigenous Australian fiction has featured Aboriginal characters, their portrayal has often involved racist representation, mythologising, a lack of complexity, and/or a relegation to minor roles (e.g. Langton Reference Langton1993; Behrendt Reference Behrendt2016; Watson Reference Watson2019; Watego Reference Watego2021).

However, Australian media production has also been supporting Indigenous creative involvement and agency in film and television (see T. Davis Reference Davis, Ryan and Goldsmith2017). Even though there is clearly room for further improvement, Indigenous characters are now proportionally well-represented in mainstream Australian television series (Screen Australia Reference Australia2016), and several ‘high-end, big-budget Indigenous–authored television drama and documentary series’ (T. Davis Reference Davis, Ryan and Goldsmith2017:232) have been broadcast. Writers’ rooms

are opening up to First Nations writers, and Indigenous creatives are moving into producing and directing. ‘I mean, it had to happen. It was going to happen. It just took its bloody time getting there,’ Mailman says. ‘But now we're here, and it means that our writers and creative thinkers can take our stories anywhere, in whatever genre we want to tell our story within.’ (Ribeiro Reference Ribeiro2021)

While scholars have highlighted the significance of ‘self-representation’ (Langton Reference Langton1993:10) whereby Indigenous creative involvement may centre First Nations voices, engage with Indigenous cultures and histories, and render racism visible (e.g. Langton Reference Langton1993; Watson Reference Watson2019; Bednarek & Syron Reference Bednarek and Syron2023), it is important not to assume that Indigenous-authored media will automatically create better or more ‘authentic’ representations. As Langton points out, such a claim is naïve, as it assumes one ‘true’ representation of ‘Aboriginality’ and envisions an undifferentiated Aboriginal Other (Langton Reference Langton1993:27). Further, the series that we analyse in this article (described below under Corpus) address mainstream, mixed audiences—meaning they must blend multiple perspectives to reach different audiences at the same time.

Relatedly, Lenz proposes that Aboriginal playwrights ‘contribute to a wider recognition of Aboriginal modes of speaking within the mainstream society and affirm their status as viable and legitimate codes in their own right’ (Lenz Reference Lenz2017:380). However, sociolinguistic analyses of Australian Indigenous-authored television are only just beginning (e.g. Bednarek Reference Bednarek2023), and we still know little about how Indigenous screen creatives may counter erasure by diversifying and complicating representations and bringing in Indigenous perspectives. Most research on marginalised Englishes in ‘telecinematic discourse’ (Piazza, Bednarek, & Rossi Reference Piazza, Bednarek and Rossi2011) has taken place in relation to non-Indigenous characters. Moreover, analyses have tended to focus on American and European film/television (Stamou Reference Stamou2014) rather than Australian productions. In addition, most of this research focuses on problematic, stereotypical, stylised representation, or Othering (see overviews in Stamou Reference Stamou2014; Planchenault Reference Planchenault, Locher and Jucker2017; Bednarek Reference Bednarek2018). As a consequence, there is a lack of knowledge about self-representation and language use in Indigenous-authored television, which we aim to address in this article.

RHEMATISATION, OVERLAY, AND ERASURE MARKING

Our analyses below draw on existing concepts from linguistic anthropology and sociolinguistics but also integrate two new semiotic processes to analyse the semiotic tactics that Indigenous screen creatives use to complicate and disrupt dominant ‘white’ discourses. They are semiotic overlay, which creates new, unexpected combinations, and erasure marking, which calls out dominant tropes and stereotypes. These processes draw on the concept of indexicality and the semiotic processes of rhematisation and erasure (Gal & Irvine Reference Gal and Irvine2019). Indexicality, theorised extensively by Michael Silverstein in various publications (Reference Silverstein, Basso and Selby1976, Reference Silverstein, Clyne, Hanks and Hofbauer1979, Reference Silverstein2003, Reference Silverstein2005), is the idea that meaning emerges in and through the connections that interlocutors realise and/or experience during interaction within a particular spatio-temporal context and over time. Importantly, research on indexicality has shown that

indexicality is a universal feature of human languages, that all referential-indexical systems share a number of specific properties, and that indexical relations are crucial to contextual inference, reflexivity and semantic interpretation more generally. (Hanks Reference Hanks2000:125)

Furthermore, contiguity is a key component of indexicality in that indexical meaning becomes interpretable in relation to—or in occurrence with—its context. Context entails the immediate situation, sociohistorical circumstances, shared norms or interpretations, and so forth (see Duranti & Goodwin Reference Duranti and Goodwin1992). For mass media, indexicals are structured and comprehended in viewer-specific ways, dependent on the situations of their use over time and in co-occurrence with other signs (or media). Additionally, Gal & Irvine identify two central components for recognising and ‘construing’ a sign as an index—attention and contrast—both of which facilitate ‘grasp[ing] the sign as figure-against-background’ (Gal & Irvine Reference Gal and Irvine2019:18). These two components work in tandem to guide a viewer's interpretation, reinforcing specific interpretations by maintaining viewer expectations (expected contrast) or extending those interpretations into new contexts.

This semiotic framework has effectively theorised language ideologies, ideas about what languages are, their social provenance, their uses and users, and so forth. As many linguistic anthropologists have also addressed, language ideologies are equally loaded with moral and political interests (Irvine Reference Irvine1989:255). These ‘interests’ become socially meaningful through the representational economies that configure language, linguistic varieties, and social actors. Analyses of language ideologies have relied on some concept of indexicality to establish the relationship between specific ideological constructs and some sociohistorical provenance. Additionally, language ideological research began to reveal a patternedness to the indexical processes that resulted in the privileging of certain languages and language varieties over others. As two of the architects of the field of language ideologies, Irvine & Gal note that

[semiotic processes] concern the way people conceive of links between linguistic forms and social phenomena, [whether explicitly or implicitly, and] … people have, and act in relation to, ideologically constructed representations of linguistic differences. In these ideological constructions, indexical relationships become the ground on which other sign relationships are built. (Irvine & Gal Reference Irvine, Gal and Kroskrity2000:37)

In our analysis below, we investigate the linguistic forms that reproduce and challenge the indexical relationships—‘the ground’—on which Indigenous difference is being configured through two alternative semiotic processes, semiotic overlay and erasure marking.

As mentioned, these processes build on Judith T. Irvine and Sue Gal's concept of erasure and rhematisation, which we now explain in turn using our own examples from First Nations contexts. Erasure is ‘the process in which ideology, in simplifying the sociolinguistic field, renders some persons or activities (or sociolinguistic phenomena) invisible’ (Irvine & Gal Reference Irvine, Gal and Kroskrity2000:38; see also Gal & Irvine Reference Gal and Irvine1995). That is, in some figure-ground relationship, certain signs of difference are made opaque or invisible such that attention is not drawn to them. For example, providing signage only in English erases the visual presence and conceptual awareness of the pervasive multilingualism in US and Australian societies as well as those individuals who are multilingual. Meek's analyses (Reference Meek2014, Reference Meek, Summerson Carr and Lempert2016) of the representational logics of Aboriginal language endangerment in the Yukon Territory, Canada, have shown the various ways in which the process of erasure affected early government displays of Aboriginal language endangerment. First, these displays masked a dominant English-speaking Canadian gaze and national complicity by foregrounding the territorially recognised First Nations languages and their plight, all in the coloniser's language but not as a consequence of the coloniser's actions. Second, these bureaucratic representations elided the multilingual realities of First Nations peoples’ lives, again emphasising only one language per First Nation and omitting English, French, and other Aboriginal languages from the sociolinguistic record (Meek Reference Meek, Summerson Carr and Lempert2016). In sum, then, erasure makes invisible or erases sociolinguistic and other phenomena of different kinds (Gal & Irvine Reference Gal and Irvine2019:20).

Moving on to rhematisation, this process refers to

a contrast of indexes interpreted as a contrast in depictions … some perceptible contrast of quality in indexical signs and takes that contrast to depict—not only to index—a contrast in the conditions under which the signs were produced; some contrast of quality in what was indexed. (Gal & Irvine Reference Gal and Irvine2019:19)

In other words, there are qualities associated with particular signs (or bundles of qualia; cf. Keane Reference Keane2003) or indexes. When these qualia become essentialised, taken as inherent in some sign, two things have happened. First, the contrasting feature(s) have become meaningful in relation to the ‘ideological ecology’ wherein they circulate and guide social actors’ interpretations or comparisons. Second, the contrast itself has been erased from attention (Gal & Irvine Reference Gal and Irvine2019:19) such that the comparison becomes opaque, forgotten, lost. For example, language endangerment discourses have up until recently privileged speech, fluency, and Elders in their enumerative strategies for quantifying language crises. Ignored are signed languages, semi-speakers (though see Dorian Reference Dorian1977), passive language users, other linguistic knowledges, other linguistic skills, and colonial trauma, because the goal has been to document the last ‘real’ speakers of the ‘dying’ language (Meek Reference Meek, Summerson Carr and Lempert2016). This ‘lasting’ discourse (O'Brien Reference O'Brien2010) bundles together qualities of authenticity, fluency, a pristine and original grammar, and a concept of purism in relation to both Indigenous languages and peoples. That is, elderly speakers became the idealised, rhematised figure of language endangerment set in contrast to thriving (colonial) languages and fluent (immigrant) populations. In essence, the process of rhematisation (iconisation) results in simplifying the sociolinguistic field by rendering certain linguistic features emblematic of certain persons (or groups) in a presumptively inherent, essential, and/or causal way (Irvine & Gal Reference Irvine, Gal and Kroskrity2000:38).

The semiotic processes of overlay and erasure marking, by contrast, interrupt the semiotic economies that privilege whiteness by complicating and layering new indexical associations and thus transforming the ‘ground’ on which meanings and interpretations rely. Borrowing from Comanche/Kiowa artist Nahmi A Piah (J. NiCole Hatfield) whose artwork uses overlay to interrupt historic colonial photographs of Native Americans, semiotic overlay refers to the act of adding new, often disruptive, elements to WEIRD images and discourses (WEIRD = Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich and Democratic; Henrich, Heine, & Norenzayan Reference Henrich, Heine and Norenzayan2010). For example, adding Native American languages, written and/or spoken, to a contemporary scene, such as the Super Bowl or an opening to a conference, would be an example of semiotic overlay. Recurrence, as poetic parallelism or (re)voicing across characters, can also be instances of overlay. Relatedly, erasure marking is the act of pointing out discourse that effaces semiotically messy features from the canvas, highlighting the categorically discrete (stereotypical) features of a characterisation. For example, when a Native American character points out that they are not from ‘the rez’ [reservation], in response to another character's misguided assumption that they are, such responses would be an example of marking erasure by explicitly foregrounding (marking) the erasure for viewers (geographic erasure of urban residences). Metalinguistic and metadiscursive commentary are opportunities for erasure marking. Like erasure and rhematisation, these two processes work in tandem to disrupt hegemonic discourses and covertly racist imagery. Erasure marking highlights gaps and either explicitly or implicitly fills them in, while semiotic overlay addresses gaps by layering on new elements or dimensions (or axes of difference and evaluation), maintaining some aspects of the recognisable (rhematised) form but with new indexical connections. As we demonstrate in our analyses below, these two semiotic processes are useful for unpacking the indexical interventions that screen creatives are using to reconfigure and complicate standard, average contrasts and axes of difference. In addition to these processes, our analysis continues to be centrally informed by the concepts of rhematisation and erasure, as we discuss the various ways in which they feature in our data.

Positioning our approach in relation to media and raciolinguistics (Alim Reference Alim, Samy Alim, Rickford and Ball2016), we begin with the assumption that ‘race’ and other similar social concepts are indexically constructed, emerging out of engagements between social actors and within their socially, historically, and institutionally mediated environments. Underscoring the mutual constitutiveness of language and ‘race’ in their handbook on raciolinguistics, Alim, Reyes, & Kroskrity (Reference Alim, Reyes;, Kroskrity, Alim, Reyes and Kroskrity2020) point out that this emerging field focuses on ‘the linguistic construction of ethnoracial identities, the role of language in processes of racialization and ethnicization, and the language ideological processes that drive the marginalization of racially minoritized populations in the context of historically rooted political and economic systems’ (2020:2). Mainstream media has long employed these practices: configuring certain codes and styles in relation to characters’ ethnoracial identities, offering evaluations of some ways of speaking in contrast to other ways of speaking and corresponding types of characters, and articulating—or rearticulating—pervasive and dominant tropes about categories of languages and persons along with the features or qualia that correspond with these discourses and patterns of differentiation. These ethnoracialising practices rely on semiotic processes like erasure and rhematisation that configure interpretations in ways that can promote ‘white’ dominant frameworks at the expense of those that deviate. This has been shown to be the case in the context of fictional representations of Indigenous characters in the US (e.g. Meek Reference Meek2006, Reference Meek, Samy Alim, Reyes and Kroskrity2020). In this study, we shift the focus to Australia and move from Other-representation to Self-representation, as we examine Indigenous-authored television dialogue and illustrate the semiotic tactics for interrupting dominant (media) discourses.

ANALYSIS OF DATA

Corpus

While our analysis is qualitative, we draw on Bednarek's (Reference Bednarek2023) new corpus of Indigenous-authored Australian television series, which we use as a source for our examples. The corpus includes dialogue transcribed from sixteen Indigenous-authored television series (2012–2021), across a range of genres. Indigenous-authored is here defined as involving at least one Indigenous director, writer, or producer according to Screen Australia's Screen Guide Reference Australia2018 (in the Cast & Crew & Production Details). This conceptualisation narrowly focuses on directors, writers, and producers rather than actors or other creatives. Table 1 shows the series included in the corpus alongside their main genres (as per Screen Australia and the Internet Movie Database 2022). Unless otherwise specified in Table 1, the dialogue comes from the first season. Below, we present one example in the form of a concordance, which presents a search term with its immediate surrounding text (retrieved with Scott's Reference Scott2020 WordSmith software). For the other, extended examples, we have re-transcribed the dialogue from the corpus following the transcription conventions outlined in the appendix.

Table 1. Series in the corpus.

The series in the corpus are fictional series that address a mixed, mainstream target audience—this differs from Indigenous-authored media addressed to an Indigenous target audience. For us, the series in the corpus are interesting precisely because of their commercial context and mixed mainstream target audience. In this mass media context, how do Indigenous screen creatives counter erasure and rhematisation by diversifying and complicating representations, by indexing their perspectives and juxtaposing differing points of view?

As we discuss examples from these series and comment on the use of Australian Aboriginal English (AAE), some background on the relevant language situation is necessary, although space precludes us from a comprehensive discussion. In brief, the linguistic consequences of colonisation in Australia can be summarised as follows.

Colonisation brought the extensive diffusion of English and with it a dramatically different configuration of languages in contact, including the emergence of pidgins, creoles and mixed languages and a range of English-lexified varieties and dialects, such as Aboriginal English. Now relatively few traditional languages are spoken day-to-day or are being transmitted to children. Yet notions of simplification and loss do not adequately capture the complexity and dynamics of the contemporary contexts. Indigenous people have developed complex linguistic repertoires, often including other traditional languages and varieties of English and/or Kriol (an English-lexified creole), or a mixed language. … Indigenous speakers have shifted, or are shifting away from traditional languages in many locations, but in some places traditional languages remain the primary languages spoken, with English or Kriol included in speakers’ repertoires. (O'Shannessy & Meakins Reference O'Shannessy, Meakins, Meakins and O'Shannessy2016:3)

Thus, the role of varieties of English, including varieties of Aboriginal English, in a speaker's repertoire depends on the speaker as well as the speaker's community or family. While Australian Aboriginal English is associated with specific features of sound, vocabulary, grammar, and cultural norms (see Eades Reference Eades, Koch and Nordlinger2014; Lenz Reference Lenz2017; Malcolm Reference Malcolm2018; Dickson Reference Dickson, Willoughby and Manns2020; Rodríguez Louro & Collard Reference Rodríguez Louro and Collard2021), the term should be considered as a broad cover term for ‘ethnolinguistic repertoires of Aboriginal people speaking English’ (Eades Reference Eades, Koch and Nordlinger2014:438). In addition to regional variation, it is hard to draw a clear boundary between a ‘heavy’ (i.e. basilectal) variety and a creole, or between a ‘light’ (i.e. acrolectal) variety and general Australian English incorporating some features of AAE (Eades Reference Eades2013). There is context-based variation and intra- and interspeaker variability (e.g. Lenz Reference Lenz2017; Dickson Reference Dickson, Willoughby and Manns2020; Mailhammer Reference Mailhammer2021). Our main focus below is on AAE lexis, following argumentation by Lenz (Reference Lenz2017).

While many phonological and grammatical features are shared with other non-standard varieties of English, the Aboriginal English lexicon reveals various unique characteristics. The lexico-semantics of AborE have been elaborated in such a way that they now allow speakers to convey ideas that are culturally bound and reflect a worldview that clearly differs from that maintained by Anglo-Australians …. (Lenz Reference Lenz2017:13)

Analyses/discussion

Lexical form and indexicality

Starting with a brief look at rhematisation, Bednarek's corpus features multiple instances of emblematic uses of specific vocabulary and morphosyntactic constructions. More generally, there are three key ways in which linguistic resources are rhematised: recurrence, character diffusion, and metalanguage. First, recurrence refers to the way that certain Aboriginal English words (e.g. mob, blackfella) recur frequently and across different television series. Character diffusion refers to the fact that these words are associated with a range of different Indigenous characters rather than being cases of individual style. It is also important that the words are associated more often with Indigenous than with non-Indigenous characters. Finally, metalanguage refers to the way that certain language resources are explicitly associated with an Indigenous identity (as discussed below). There are thus multiple ways in which dialogue may enregister specific features reinforcing their indexicalisation of AAE and rendering a character identifiable as Indigenous.

For example, initial lexical analysis (Bednarek Reference Bednarek2023) suggests that the words country, mob (often as second person address you mob), blackfella(s), and community recur across series and are strongly associated with (different) Indigenous characters. Figure 1 shows all instances of you mob in the corpus (seventy-one instances, occurring in eleven out of sixteen series). These words also cluster with other Aboriginal English words to create styles. For example, utterances that contain mob also contain multiple other Aboriginal English words (e.g. Aunty, ceremony, deadly, grannies, sis, walkabout, dreaming, gammon, humbug, tidda). Other research (Bednarek Reference Bednarek2020) suggests that kinship terms and the utterance-final tag eh are important indexes of Indigenous identity in Indigenous-authored television series.

Figure 1. Instances of you mob (concordance).

It is important to note that the presence of such rhematised elements in the data does not imply automatic erasure of differences, or the construction of some singularly homogeneous Indigenous figure. Indeed, Indigenous characters in the corpus do not all use language in the same way, with different codes and styles clearly identifiable. For instance, only some characters’ speech features been as a past tense marker (e.g. I been tell you not to put sprinkler in here), absence of auxiliaries (e.g. How much she paying you off?), use of suffix -em on verbs (e.g. Lucky I been take ’em that shirt off him), or them as determiner (e.g. See them rocks?). Some characters’ speech features a largely ‘standard’ or ‘vernacular’ Australian English. Future work will identify the different codes and styles along with the personae they correspond to, including the association between cultural knowledge, status (e.g. Elders), setting (e.g. urban/rural/remote), perceived ‘blackness,’ and other relevant features.

Metalanguage and rhematisation

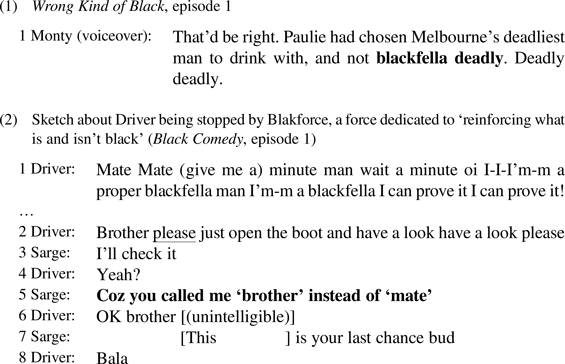

Metalanguage is shown to be an important source of rhematisation in the corpus, as it occurs across different series, albeit often in humorous genres. Relevant extracts are shown in (1) and (2) from Wrong Kind of Black and Black Comedy.Footnote 2

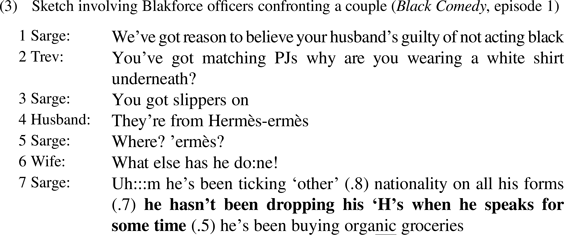

Metalanguage targets a variety of different linguistic levels, including, for example, word meanings (as seen in (1), referring to the blackfella meaning of deadly, i.e. ‘great’) and word choice (as seen in line 5 in excerpt (2)), as well as phonology. Extract (3) from Black Comedy is a good example of the latter, a sketch which makes explicit the link between ‘h-dropping’ and blackness (line 7).

Such explicit statements link words and linguistic features with Indigenous speech. They both create an expectation of difference (languaging ‘race’) and define the features that accompany or index the difference (racing language). In (3), the omission of the /h/ sound becomes iconic of an Indigenous identity. Metalinguistic awareness of difference(s) contributes to rhematisation. This is in line with Dickson (Reference Dickson, Willoughby and Manns2020:139–40), who identifies this as a salient language feature, occurring in media language and as the subject of social media commentary.

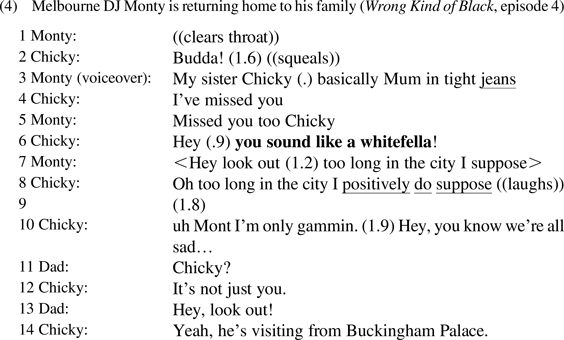

In extract (4) from Wrong Kind of Black, metalanguage is combined with mocking stylisation to foreground and negatively evaluate the Indigenous character's language variety as speaking like a ‘whitefella’ (line 6).

In this excerpt, the metalinguistic commentary rhematises racialised and linguistic differences. The contrast in this case, as with most cases, is a White/Black distinction that also incorporates a rural or remote vs. urban axis of differentiation, thus bundling together a type of voice (‘posh’) with urban-ness, whiteness, and upscaleness (line 14 also shows the link with Britishness). Apart from one additional line in the same episode (“It's OK, bro. Bro. You're home, bro”), the character Chicky has no additional dialogue in this narrative, which makes the metalinguistic commentary here all the more important in foregrounding the semiotic contrast between the characters for the audience.

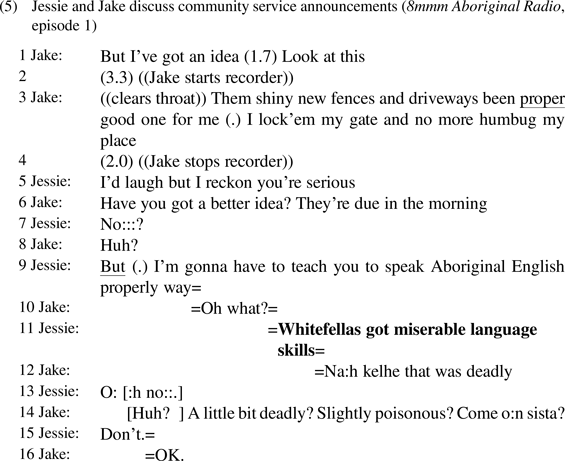

Unsurprisingly, metalanguage also occurs in commentary on the (stylised) linguistic performances of characters whose Indigenous identity is contested or who do not have an Indigenous identity. The latter is shown in extract (5) from 8mmm Aboriginal Radio. In this scene, Jake, who is white, and Jessie, who is Indigenous, need to provide community service announcements in order to promote a government housing project, but no one has said anything positive, and they are running out of time.

Extract (5) illustrates the use of a mock variety to differentiate between a non-speaker and a speaker of AAE. However, rather than reproducing the appropriative relationship that Hill (Reference Hill2008) has identified as part of mock registers in the US, this sequence ‘flips the script’ as it were, resulting in the mock variety being an object of mockery itself (“Whitefellas got miserable language skills”). This reverse mocking interrupts the rhematised association of poor language skills with Indigenous speakers. This excerpt also shows how metalanguage can require cognitive effort on the part of audiences. To ‘get’ the humour, the audience first has to recognise Jake's utterance in line 3 as a linguistic performance of Aboriginal English, and then to also interpret Jake's subsequent attempts as iconic lexical indexes of Aboriginal English (e.g. the words deadly, poisonous, and sister in lines 12 and 14). That is, the metalanguage has to be recognised as pointing both backwards (anaphorically) and forwards (cataphorically). Examples of teaching Aboriginal English to non-Indigenous characters also occur elsewhere in the corpus (e.g. in Black Comedy sketches; see also Dickson Reference Dickson, Willoughby and Manns2020:137), while examples of white characters badly imitating Indigenous characters also recur (e.g. in The Warriors). Additionally, Jessie's statements in lines 9 and 11 demonstrate the process of erasure marking when she implicitly underscores the grammaticality of AAE varieties and the complex and grammatical repertoires of Aboriginal speakers, countering assumptions of ungrammaticality in relation to AAE varieties and incompetence in relation to AAE speakers. Overlay is at work as well when Jessie re-maps the discourse, laminating the dominant discourse of Indigenous dysfluencies onto non-Indigenous, English-speaking characters. That is, the expectation of dysfluency gets flagged and discursively flipped, disrupting a linguistic incompetence associated with Indigenous speakers and a linguistic competence associated with white speakers (Meek Reference Meek, Samy Alim, Reyes and Kroskrity2020).

Racism, anti-racism, and challenging rhematisation

As anti-racism has taken centre stage in Australia and North America, Indigenous-authored television offers opportunities for remediation by illustrating what racism looks like (see Bednarek Reference Bednarek2023:197–98) and providing direct and indirect commentary that confronts it. Language becomes an effective means for making visible both racist stances and anti-racist responses. As above, lexical recurrences and metalanguage are two of the ways in which overlay and erasure marking complicate and diversify simplified (rhematised) indexical relationships. We illustrate this by way of discussing several extracts from the comedy 8mmm Aboriginal Radio (henceforth 8mmm). This series features the character Dave, the white training manager, who is described in a relevant study guide as follows.

Dave is a plainspoken, cringe-funny, forty-something, closet-alcoholic, passive-aggressive racist. He has no understanding of Aboriginal culture nor does he think he needs to, especially in the workplace. Dave doesn't care about cultural protocol; he only cares about his pay packet. He is charming when he needs to be but usually to further his own agenda. (Marriner Reference Marriner2015:5)

Language is used to make visible Dave's racist stance, including in his (metalinguistic) comments in extract (6), where Indigenous languages are denied any status and the (presumably) monolingual white character's superiority is asserted through his command of English (presented as monolithic), regardless of the multilingualism in Mparntwe/Alice Springs, where this series is set.

This exchange directly addresses the enduring legacy of colonial language ideologies, the idea that Indigenous people need to learn English, and that Indigenous languages may not even be languages but just “bloody gibberish” (line 17). This dialogue highlights the colonial perspective to the audience, iconically portraying Indigenous languages as nonsense and erasing Indigenous speakers’ competence, while also setting up an axis of difference for destabilising that perspective. Viewers hear resisting discourses that challenge these emblems and erasures through Thomas and his friends, overlaying Dave's dominant perspective with their more nuanced conceptualisations of Indigeneity and language. Furthermore, the reported speech of Thomas’ mother (line 18) underscores the boys’ speaking back at (white) authority. The enumeration of languages is also another example of erasure marking wherein these counter-discourses interrupt the effacing of fluency and multlilingualism in dominant white discourses and racist perspectives personified by Dave and highlight their underlying biased logics.

As seen in extract (7) below, Dave's racist persona is also indexed through pejorative terms (in lines 1 and 8: “scrag”, “crazy old bird”, “chink”—in another scene, he uses offensive labels for Aboriginal people), dispreferred labels (“Aborigines” in line 3), and mocking, both as a variety (using a mock Asian accent in line 8) and as a speech act (“tomartoes”, “tomaytoes” in line 5).

In addition to calling out Dave's racism, this exchange also underscores how dominant racialising frames erase diversity within Indigenous identity (Dave misidentifying the staffer based on appearance). Lines 6 and 8 highlight this semiotic process of erasure, via erasure marking, and engage the viewer in this act of recalibration.

In excerpt (8) from the same episode, the idea that Aboriginal organisations should be run by Aboriginal people is stated directly by Jake, another white character (line 5). His stance is juxtaposed with Dave's position as the latter continues to perform an entrenched, irreversible ‘mindset’ of cultural and racial superiority.

Through mocking Jake, Dave indexes his entitlement (his right to correct and control), differentiates himself from Jake, and becomes coloniality personified (rhematisation). However, in drawing the audience's attention to a taken-for-granted point of view (Dave's in lines 2 and 4), this dialogue then contrasts it with an alternative point of view qua Jake. Jake's Aboriginally inflected stance that reasserts Indigenous control (line 5) semiotically overlays Dave's position, a mainstream discourse of assimilation. This process of overlay preserves the colonial frame while at the same time adding an Indigenous dimension.

Extract (9) elaborates the racist, authoritative personification of Dave further, demonstrating his cultural arrogance in relation to Elder Lola, whom he feels justified to correct regarding language use (line 4).

Here the recurrence of Aboriginal/Aborigine (Dave's re-voicings of the ABC staffer) produces a parallelism across scenes, resulting in a process of overlay that walks the audience through the countering of rhematisation by adding new dimensions of meaning with each uttered version. Specifically, it complicates by revealing multiple points of view. The contestation over lexical variants poetically differentiates, suggesting that decontextualised words are not enough to disrupt racism but analyses of their recontextualisations can reveal acts of appropriation and dominion, as evidenced by Dave's re-voicings above.

Before we move on to other examples, it is important to note that evaluative discourses around blackness and/or Aboriginal identity (as in extract (7) above) recur across series, sometimes but not always produced by racist characters. Such discourses are mediated reflections (Bednarek & Syron Reference Bednarek and Syron2023) of contested and shifting intersubjective definitions and conceptualisations of Aboriginality in Australia (e.g. Carlson Reference Carlson2016). In some cases, these discourses may circulate what Meek (Reference Meek, Samy Alim, Reyes and Kroskrity2020:369) calls the ‘racial logic that determines Indianness: purism (percentage of “Indian blood”)’ (see also Bond, Brough, & Cox Reference Bond, Brough and Cox2014; Carlson, Berglund, Harris, & Poata-Smith 2014 in the Australian context).

• How Aboriginal are you, like, half? (Kiki and Kitty, episode 1)

• I just found out through stringent DNA saliva testing that I am approximately zero point zero one per cent oppressed by the Australian colony. … I'm one of you, sis. And we are deadly. (All my Friends are Racist, episode 3)

• She [Aunty] found out she was 1/64th black last week. (KGB, episode 3)

The enfigurement of Indigeneity discussed so far has focused on processes of rhematisation in relation to lexical indexes, metalinguistic statements, and metadiscursive commentary. We have shown how rhematisation in these series works to configure a viewer's interpretation, and how overlay and erasure marking complicate conceptualisations of Indigeneity while also interrupting hegemonically racialising discourses (via racist characters). The different ways in which such discourses circulate or challenge raciolinguistic ideologies is worthy of further study, including how concepts such as ‘blackness’ and ‘Aboriginality’ are differentiated or conflated in and through the analysis of the different bodies that are cast in different types of linguistic performances (as in extract (7)). However, we now move on to discuss discourses of erasure.

Discourses of erasure and erasure marking

The bundling of linguistic and non-linguistic features via processes of rhematisation is but one way in which raciolinguistic ideologies are constituted by and constitutive of racial and lingual differences. Erasure is another way in which these differences are realised. However, in identifying this process we attend to absence, as in what's missing or not apparent? What is the viewer's attention being drawn away from? What is the audience not seeing or hearing? And then, how are characters calling attention to such erasures (in acts of erasure marking and/or overlay)?

In 8mmm, discourses of language endangerment—which can involve erasure (as explained above)—are associated with white characters. For example, in a conversation among Koala, who is white, and Milly and Lola, who are Indigenous (extract (10)), language endangerment becomes a topic of conversation as they attempt to answer a cultural knowledge test assigned by Dave.

In addition to the knowledge about language endangerment being linked to Koala, the white character, an evaluation of her knowledge is expressed by Milly, one of the Indigenous characters. This discourse coordinates two interpretations: an indexical link between (esoteric) quantitative information about Indigenous languages with whiteness and an indexical link of a lack of knowledge about the situation with Indigeneity. However, the dialogue proceeds with a negative stance in relation to the knowledge associated with whiteness, suggesting that such factualising about Indigeneity is more the exception rather than the norm. The last two lines of this excerpt build on this interpretation, suggesting not only that such knowledge is rare and weird (WEIRD, i.e. Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich and Democratic; Henrich et al. Reference Henrich, Heine and Norenzayan2010), but that those who produce it are slow to learn. In response to Koala's rhetorical question in line 4, Elder Lola reinforces the prior stance, that such knowledge (produced in dominant white institutions) is non-normative, if not remedial (line 5). The plot confirms this, given that the white character Dave not only asked the Aboriginal characters to take a cultural knowledge test, but also managed to give them an irrelevant test from the internet that does not apply to them. This is thematised in extract (11), which again features erasure marking.

In this excerpt, Dave's character maintains the erasure of Indigenous differences, lumping all Indigenous peoples into one category, rather than differentiating between, for example, diverse Central Desert peoples and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Furthermore, he demonstrates the erasure of alternative ways of knowing by relying on the “cultural knowledge test”. That is, the use of this test in this episode (illustrated in extracts (10) and (11)) highlights the WEIRD epistemological framework, its irrelevance (and outright WEIRD ignorance), and the reductivism that a Western universalist approach produces—it erases all other possible approaches to knowledge, learning, and interpretation. In this extreme reductionism, of which endangerment is a version, there is a corresponding elevation of attributes through WEIRD discourses of purism, rarity, and valorisation, that is, pricelessness. The erasures that Dave's character reproduces are ones that maintain dominant systems of value and devalue Indigenous systems of value, as the Indigenous characters in these series articulate through tactics of erasure marking.

Another way in which a discourse of erasure is presented and contested happens in relation to discussions of language loss, and the Stolen Generation, as seen in extract (12) from Total Control (orthographically transcribed).

(12) [Senator Alex Irving is practising her maiden speech, to brother Charlie] (Total Control, episode 1)

1 Alex: Thank you, Mr. Speaker. I wanted to speak to you in my traditional language, but I can't. My mother was sent to an Aboriginal reserve when she was a child, and those words were taken from her. So the only language I know is English. But look how far we've come. My name is Alex Irving and I'm standing here before you in the Senate of Australia. I thought this place wasn't for someone like me, not just because I'm black, but also because I'm female, from regional Queensland, because I left school at fourteen, because I'm a single mum and because my own mother was stolen and grew up on the mission. But I'm an Australian. And if I'm here, that means any one of us can be here. And if this place is ever barred to any one of us then the building around us doesn't deserve to keep on standing, let alone the Parliament that meets here.

This is an example where the (potential) erasure of colonial policies and colonial trauma in language endangerment discourses (see above on the Canadian context) is directly countered by repeatedly referencing the Stolen Generations and the actions of the colonisers (albeit using passive structures). In addition, while traditional Indigenous languages are very rare in the corpus (with the exception of Cleverman), they do occur in the speech of characters with different age ranges rather than only Elders. Passive language use is featured in Robbie Hood, where Robbie's nan uses Warlpiri, which Robbie clearly understands but does not speak himself. Use of signed language also occurs (in 8mmm). See Bednarek (Reference Bednarek2023:184) for further discussion of the limited use of traditional Indigenous languages in the corpus. These are some ways in which these series counter the erasure common in language endangerment discourses (as outlined above), overlaying Indigenous languages into English dialogue. Television dialogue also counters discourses of erasure through metalanguage, which explicitly references plurality of languages or the multilingualism of communities/speakers, while the use of specific terms referring to particular peoples/language groups (e.g. Arrernte, Biripi, Gija) makes visible to the audience the diversity of Indigenous peoples and cultures in Australia (details in Bednarek Reference Bednarek2023:194).

CONCLUSION

In this study, we have only scratched the surface of a rich dataset of Indigenous-authored television series that address a mixed, mainstream target audience. The analyses have painted a picture of diversity. On the one hand, there is some evidence of rhematisation, where bundles of linguistic features (or ‘qualia’) rhematise Indigeneity in opposition to non-Indigeneity and simultaneously erase ‘whiteness’ from conceptualisations of Indigeneity. There is some re-entrenching of ethnoracial difference, highlighting contrasts. On the other hand, not all Indigenous characters use the same style or variety—these characters are not portrayed as linguistically homogenous. Moreover, there are overt discourses and metalanguage that complicate the representation of Indigeneity. These discourses draw on the policing of ethnoracial difference, thus also circulating such discourses (e.g. of purism/blood) even where they are challenged or are the source of humour. Some characters are shown to have to contend with questions, challenges, or denials of their Indigenous identity. This makes visible the discursive co-construction of Indigeneity, especially for characters that do not conform to raciolinguistic ideologies of purism. Language can play a role in such challenges (e.g. when Indigenous characters use inauthentic styles or ‘sound like a whitefella’), but other features that are indexical of Indigeneity (e.g. appearance, behaviour) also play a role. While additional research is necessary, we hypothesise that the fewer features indexical of Indigeneity a television character has, the more likely their identity as Indigenous will be questioned, challenged, and/or denied. Even though the concept of rhematisation suggests that a truly robust iconic index would require no additional semiotic support, our analysis shows that there is a semiotic overlaying that Indigenous creatives may use to produce a recognisable Indigenous characterisation while also challenging that same viewer expectation. In fact, heterogeneity is key to interrupting the simplifying effects of rhematisation and erasure.

In sum, the metalanguage and discourses that we have observed in the dataset draw our attention in different ways to representation and raciolinguistic ideologies, achieving multiple conjectures (Gal & Irvine Reference Gal and Irvine2019). First, our analysis reveals how Indigenous creatives artfully weave in topics and issues that circulate in Indigenous media and discourses, such as language endangerment and racism. Second, while some linguistic cues index an Indigenous identity, there are also challenges to a WEIRD epistemological framework. Third, linguistic variation across characters indirectly problematises discourses of purism and assumed homogeneity. Finally, these data show that Indigenous creatives are in effect ‘decolonising’ mainstream discourses about and interpretations of Indigenousness by reclaiming the indexical landscape through processes such as semiotic overlay and erasure marking.

We have shown how screen creatives may counter erasure by diversifying and complicating representations and bringing in Indigenous perspectives, while also hinting at the diversity of representation. That is, revealing what has been erased destabilises the rhematisation. While there is a clear difference between series, we have treated these here as an aggregated dataset and have aimed to identify patterns that recur across series rather than exploring differences of representation. Nevertheless, we do not aim to imply that all series are the same. As mentioned above, Langton (Reference Langton1993:27) argues that it is naïve and essentialist to believe that ‘any Aboriginal film or video producer will necessarily make a “true” representation of ‘Aboriginality’’’ and that such an assumption would be ‘based on an ancient and universal feature of racism: the assumption of the undifferentiated Other’ (italics in original). In focussing solely on Indigenous-authored series, we also have not investigated potential differences to series that are not Indigenous-authored. In addition, audience research would be necessary to investigate how different social groups make sense of such representations. There is further work to be done on whether/how screen creatives take advantage of multiple ‘orders of indexicality’, or ‘indexical bivalencies’, allowing multiple possible interpretations, some of which might resonate with most audience members (easily recognisable), while others rely on more specific cultural or linguistic expertise and experiences. What is clear is that Indigenous creatives find ways to destabilise hegemonic narratives of difference, drawing viewers’ attention to semiotic processes of rhematisation and erasure, while simultaneously countering those processes by shifting the linguistic and discursive ground on which viewers’ interpretations have relied. Thus, language and language-ing are critical sites for discovering enduring acts of colonisation and for enabling new strategies of decolonisation.

APPENDIX: TRANSCRIPTION CONVENTIONS

- .

falling intonation

- ?

rising intonation

- !

raised volume

- underline

stress

- :

increased length

- =

latching

- -

break in word, sound cut off

- (.)

pause of 0.5 seconds or less

- (n.n)

measured pause

- h

outbreath

- .h

inbreath

- [ ]

overlap

- (())

transcriber comment or description

- [()]

uncertain transcription

- °

decreased volume

- < >

decreased speaking rate

- > <

increased speaking rate

- bold

form of analytic interest