Between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the Inka built the largest empire in the Americas. This empire integrated several ethnic groups and polities into an imperial fiction of unity, reinforced by Inka-style standardized material culture and architectural practices. However, current research shows that Inka imperialism was multiscalar, diverse, and negotiated across the empire's geographic expanse. The Inka invested heavily in roads, new administrative centers, and the mobilization of a multiethnic army. At the same time, they maintained local leaders as proxy administrators, integrated local sacred landscapes into their ritual pantheon, and granted new territories to their allies (for some examples of this diversity, see Alconini Reference Alconini2016; Bray Reference Bray2003a; D'Altroy Reference D'Altroy1992; Dillehay and Netherly Reference Dillehay and Netherly1998; Malpass Reference Malpass1993; Malpass and Alconini Reference Malpass and Alconini2010). There was no one-size-fits-all approach to Inka imperialism; instead, there was diversity across geography, chronological time of the conquest, and the relationship between the empire with its new subjects. At the root of this diversity were the relationships established between the Inka and their subjects. Sociopolitical institutions already in place at the time of the Inka conquest directly influenced local experiences of the empire across its regions.

I previously argued that Inka expansion in the Peruvian highlands was facilitated by shared sociocultural practices with other Andean populations (Hernández Garavito Reference Hernández Garavito2019:89–98). Through “cultural familiarity,” local communities and the Inka Empire could reinvent local and state practices to make incorporation less mutually costly. Such practices could be found at the residential, local, and regional levels (Hernández Garavito Reference Hernández Garavito2020).

As part of my archaeological research in Huarochirí, I excavated at the residential site of Ampugasa. Here, the Inka period (AD 1400–1532) was marked by a shift from circular patio groups, with patios being a shared space of interaction among households, to rectangular enclosures, with internal patios bounded to a single house. Results from analysis and distribution patterns of ceramic and faunal remains showed that no significant shift in access to new styles or goods matched the dramatic shift in domestic space (Hernández Garavito and Osores Mendives Reference Hernández Garavito and Mendives2019:861–862). This conclusion generally aligns with research in other regions of the Andes, where the Inka period saw the building of new settlements aligned with imperial stylistic preferences (Alconini Reference Alconini2008:72–73) or the intrusion on and even destruction of previous domestic architecture (Acuto Reference Acuto, Silverman and Isbell2008:851–857). This shift in domestic space supports Ogburn's (Reference Ogburn2008:290) observation that the Inka prioritized hindering community ties as a mean to avoid contestation. However, rather than simply intruding into pre-Inka residential spaces, my excavations show that pre-Inka houses were ritually closed before the move of local family groups into the new residential enclosures. Previous local houses remained a visible and accessible element on the built landscape of the site.

In this article, I build on these results to investigate how the ritual abandonment of previous residences and the construction of new ones in Ampugasa reflected the interplay between continuities and transformations that reinvented community practices under the Inka Empire. On the one hand, Inka period interventions on domestic buildings created visible statements of the transformations brought about by the incorporation of indigenous communities into the empire (Ferrari et al. Reference Ferrari, Acuto, Izaguirre and Jacob2017:52). On the other hand, I argue that the continuity of practices and the sacralization of previous domestic space strengthened community ties among the site's inhabitants and offset new limitations on everyday interaction resulting from new architectural layouts (communal to private patios). The ritual and careful closing of previous houses, their persistence as a visible and experiential element within the site, and the incorporation of Inka-style materials in local ritual contexts suggest that the Inka period reshaping of lived space did not negate community practices and spaces.

To support this argument, I first summarize the scholarship on provincial Inka domestic architecture as transforming everyday interactions within residential settlements. Then, I focus on Huarochirí, arguing that, from regional to local and residential scales, there is a pattern of the Inka grafting transformation onto the selective continuity of local practices and institutions. Finally, I review the excavation results from Ampugasa. Ultimately, I argue that, although changes in domestic architecture may have served to adapt Ampugasa to Inka stylistic preferences and to facilitate standardization measures visible across the empire, the enshrinement of previous houses and the continuity of indigenous practices and materials show that Inka imperialism in Huarochirí, at the residential level, directly built on the maintenance and expansion of community ties and collective identities.

Residential Life and the Inka Empire

Archaeological research worldwide has investigated the relationships among people, buildings, and activities within residential spaces (Allison Reference Allison1999; Blanton Reference Blanton1994; Hendon Reference Hendon2010; Wilk and Rathje Reference Wilk and Rathje1982). Households and houses do not exist in a vacuum; residential life is the locus not only of quotidian domestic activities but also where practices that tie people to broader collective identities are enacted (Janusek Reference Janusek2004:36; Kahn Reference Kahn2014:22–25). In colonial situations, these collective identities are strongly tied to material remembrances and reinvention of a shared precolonial past (Thomas Reference Thomas1992). Following Hendon (Reference Hendon2010:4), residential space and memory are tied as “lived through everyday life from an intensely material perspective.”

In the Central Andes and across the chronological sequence, research on residential life has emphasized the impact of formal characteristics—boundness, visibility, and internal communication—as intrinsically tied to community practices and worldviews (Nash Reference Nash2009). For example, Guengerich's (Reference Guengerich2017:266) analysis of the large houses in Chachapoyas explicitly argues for houses as models of “public-making”; in other words, the design and imposing nature of houses communicate an intentional message to observers by assuming that these observers are embedded in shared cultural values that will allow them to understand these messages. Houses are also spaces for ritualized behaviors, which can be nearly indistinguishable from domestic activities and materials. Siveroni (Reference Siveroni2006:144–145) demonstrates this point by comparing the recovered materials from structures identified as either temples or houses in the Kotosh tradition of the Peruvian highlands. Everyday domestic activities like cooking and sharing food have a communal counterpart, such as feasting, that promotes a household-level activity to a practice that brings different households together.

In the specific case of Inka architecture, scholarship demonstrates a central concern with materializing the power relationships and dominance imposed by the empire in conquered territories (Alconini Reference Alconini2004:403–408; Pavlovic et al. Reference Pavlovic, Troncoso, Sanchez and Pascual2012:552). The well-reported transformations of local landscapes through monumental architecture and the modification of natural landscapes (Christie Reference Christie2015; Dean Reference Dean2010; Meddens et al. Reference Meddens, McEwan, Willis and Branch2014) also have a counterpart in domestic spaces. Research on provincial Inka period settlements in the highlands shows a general trend from circular structures surrounding patios (or a patio group) to bounded, single-access, rectangular multifunctional enclosures during the Inka period (Covey Reference Covey2008). In patio groups, the connected rooms could be inhabited by one or more than one extended household. The layout connects different rooms through a shared patio, favoring interaction of the co-residence group in carrying out activities such as cooking or crafting. Conversely, Inka period enclosures seem to hinder the size of the household and interhousehold interaction, creating spaces for different domestic activities within enclosed houses (open patios, storage units, cooking spaces, large rooms).

Most in-depth investigations of this pattern have been conducted near the southern boundaries of the empire in Argentina, Chile, and Bolivia. Broadly, it seems that the Inka would create ritual settlements, regional administrative centers, or waypoint stations and selectively choose aspects of domestic architecture in which they would intervene (Pavlovic et al. Reference Pavlovic, Troncoso, Sanchez and Pascual2012:560). In residential spaces, however, we may be able to observe the choices of local communities in the face of imperial imposition. For example, in La Huerta (northern Argentina), Acuto and Leibowicz (Reference Acuto, Leibowicz, Alconini and Covey2018:338–340) discuss the imposition of rectangular buildings on indigenous households that prioritized communal spaces (connecting patios) as evidence of a new social layer emerging as a consequence of Inka imperialism. Acuto (Reference Acuto, Silverman and Isbell2008:849–851) equates architectural shifts to a “new agency,” in which a group of people may reap both the benefits and repercussions of associating themselves to the Inka and choosing to emulate their buildings.

In the Lurín Valley, archaeologists tend to associate shifts in architectural patterns as the outcome of the potential appearance of new ethnic groups (Cornejo Guerrero Reference Cornejo Guerrero2000:162–163; Makowski Reference Makowski2002; Marcone Reference Marcone2005; Sánchez Borja Reference Sánchez Borja2000:143–144). However, we cannot assume that identities remained fixed and conveniently marked through architecture in a period of imperial subjugation and expansion within a single ethnic group regardless of new populations moving in. In Huarochirí, we do not yet have any concrete evidence of Inka administrators living there. The logic behind the shift in architectural patterns may reflect political or economic reasons beyond ethnic identification. Instead, I propose that, even when radical shifts in the architectural layout occur, the sites’ inhabitants still may recognize in the new buildings significant continuity of the shared values and practices that made them a community.

In Ampugasa, rectangular compounds during the Inka period replaced the previous patio groups, reinforcing the model of limiting interactions among familial groups. However, this architectural shift did not lead to the destruction of previous houses. Pre-Inka houses remained standing and easily accessible to the population after these changes were made. Moreover, the proximity of pre-Inka houses to the ritual core of the site may have reinforced the transformation of domestic buildings into sacred remnants of community identity. The enshrinement of previous domestic spaces, the continuity of domestic practices, and the continued access to local goods may have offset the limitations of communal interaction implied by the residential shift to rectangular compounds.

In the next section, I use ethnohistorical research to characterize the regional identity of the Huarochirí people and to propose a model of how the Inka became enmeshed in local worldviews. I suggest that the experience of living in a new type of house (transformation) was less impactful among the people living in Ampugasa than the “shared values” (continuity) that remained embedded in the old and new domestic spaces, thereby allowing for the sacralization of the abandoned domestic spaces.

The Ritual Roots of Community in Huarochirí: Before and after the Inka

Throughout this article, I argue that the Inka grafted imperial policies onto community spaces and practices directly related to the construction of shared identities among the people of Huarochirí. Scholars have particular insights into these spaces and practices through the outstanding colonial period document known as the Huarochirí Manuscript (HM). The HM was compiled by 1608 in the town of San Damián de Checa under the ecclesiastical mandate of Francisco de Ávila as an attempt to create a compendium of local idolatries (Acosta Reference Acosta1979; Salomon Reference Salomon and Pillsbury2008a). The end product was a compelling testimony of the collective memory of a small Andean group (Salomon Reference Salomon and Pillsbury2008b:296), penned by an Indigenous scribe in Quechua (Durston Reference Durston2007) and embodying the unexpected consequences of colonialism, when a tool of oppression became a space for local agency.

The central motif of the HM is the birth, history, and veneration of Pariacaca, a snowcapped mountain near the eastern highland boundary of the province. The people of Huarochirí were divided into ayllus, broadly understood as landholding collectives that shared the same ancestry and social obligations of reciprocity and could become part of larger nested kin communities (for a detailed discussion, see Salomon Reference Salomon and Dillehay1995). Ayllus were ranked through their degree of kinship to Pariacaca (Salomon and Urioste Reference Salomon and Urioste1991:71). Following from the HM, and given the dispersed settlement patterns of the region and the absence of monumental centers, it seems that the people of Huarochirí were not politically unified but maintained a collective identity through shared ancestry. However, even though it was central to the narrative of regional unity, Pariacaca Mountain was a faraway and inaccessible landscape feature for many of the people considered his “children.” My work (Hernández Garavito Reference Hernández Garavito2020), as well as that by Chase (Reference Chase and Bray2014, Reference Chase, Alconini and Covey2018), shows that rock outcrops in both residential settlements and shrines materialized this ancestry by functioning as avatars representing Pariacaca or his children. Through seasonal performances of rituals in honor of Pariacaca and daily interaction with the outcrops, the peoples of Huarochirí maintained their collective memory and came together as kin.

Although the Inka shared an understanding of ayllus with other Andean polities, they reshaped this institution to fit into administrative semantics by grouping them in waranqas. This term defines an Inka period ideal unit of 1,000 taxpayers (Julien Reference Julien1988:258). Historical and archaeological research on Cajamarca (Watanabe Reference Watanabe2015) and Ancash (Zuloaga Reference Zuloaga2012) show that the Inka used the waranqa organization scheme as a means to standardize and manipulate the demographic makeup of subjected populations. In Huarochirí, my analysis of the HM suggests that the Inka understood the importance of the local reinforcement of kinship through regional, local, and residential scales and grafted waranqas onto local ayllu divisions (Hernández Garavito Reference Hernández Garavito2019:385–387).

Most references in the HM indicate that the Inka lord was an active participant in Pariacaca's veneration (a dancer in his festival), which reinforced and placed the rituals in a larger dimension as part of state-sponsored festivities that honored the mountain (Salomon and Urioste Reference Salomon and Urioste1991:Chapter 17). The Inka people were portrayed as another kin lineage to Pariacaca and, by extension, to the people of Huarochirí. In one reference, the HM states that the Inka set a group of 30 people at Pariacaca's foothill to feed and care for the mountain; there is archaeological evidence for this intervention (Farfán Reference Farfán, Velarde and Svendsen2010:389–400). The HM also notes that the people of Huarochirí supported these caregivers through tribute, which, in turn, had an impact on production at household and settlement levels. The ideal of social reciprocity critical to ayllu internal workings is embedded in this relationship: the Inka Empire fed Pariacaca, and the people of Huarochirí fed the people assigned to Pariacaca's care by the Inka.

The process of the Inka Empire becoming entangled in local practices served both imperial policies and local pursuit of agency: if Pariacaca was at the center of collective practices that maintained unity among the people of Huarochirí, then the Inka were directly engaged with the critical importance of the local ancestors. The Inka were renowned for assimilating regional deities into the state pantheon (Christie Reference Christie2015; Meddens et al. Reference Meddens, McEwan, Willis and Branch2014). Astuhuamán (Reference Astuhuamán and Joffré2004:17) goes further, arguing that the Inka appropriated the ritual significance of Pariacaca as a tool for conquering and integrating areas outside of Huarochirí into the empire. In other words, the Inka seemed to have more interest in shaping and transforming communal practices in Huarochirí than disrupting them outright.

The examples from the HM suggest that the Inka built on existing community ritual and identity to reinforce their control over the region. Grafting imperial policies onto the regional level created spaces for Indigenous retellings of the experience of Inka imperialism. In Huarochirí, residential life and the household experience were not divested from these broad ritual narratives, because rock outcrops were a daily reminder of unity through Pariacaca in residential settlements. If the Inka grafted even their more radical innovations on local institutions, this process would not only affect local responses but also inform—and potentially have an effect on—the power of state presence in the provinces. In the next section, I use my excavations in Ampugasa to investigate this suggested interplay of cultural transformation and continuity under Inka political domination materially.

Excavations in Ampugasa

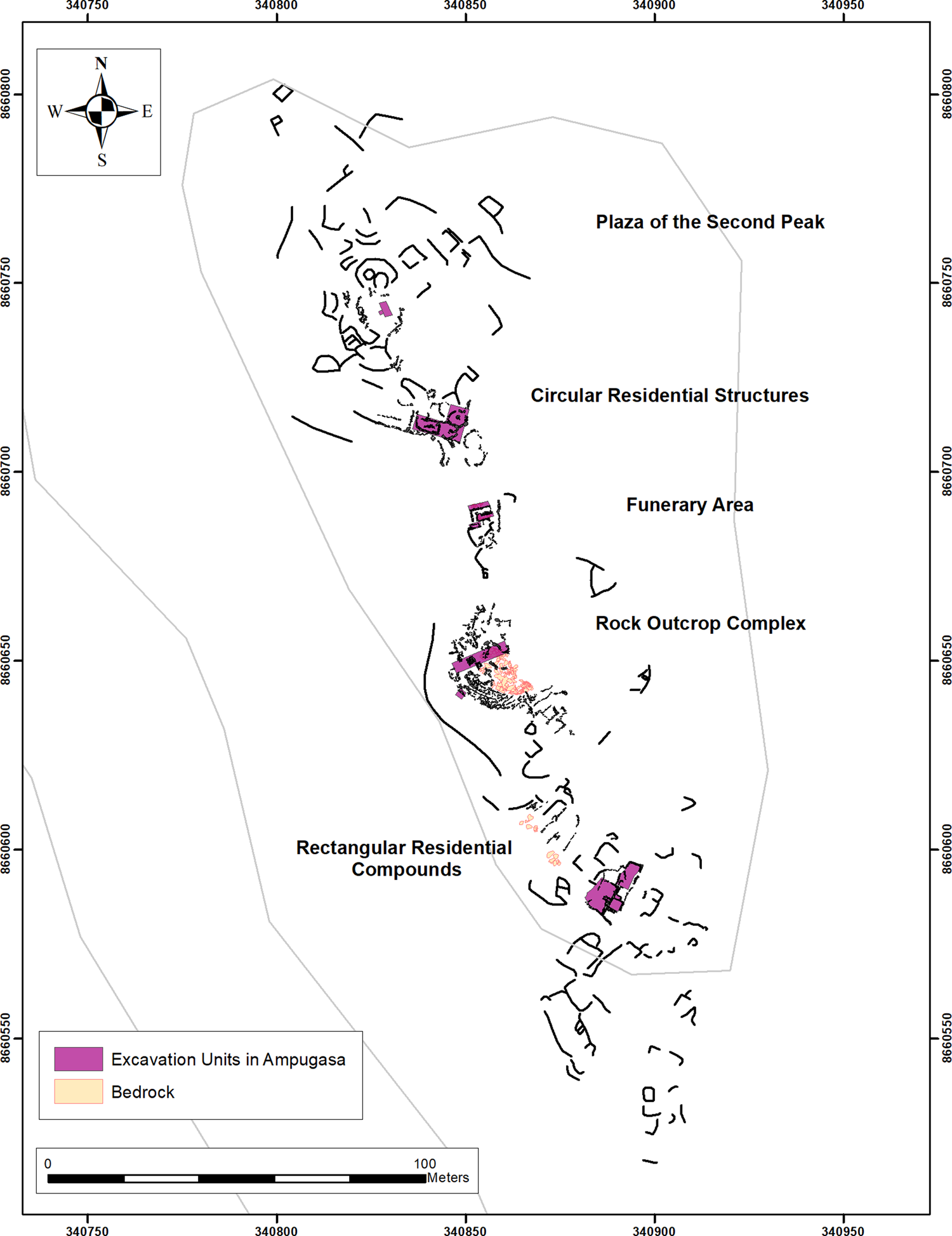

Ampugasa is a small residential complex (~1.6 ha) located atop Mount Orcocoto in the middle Lurín Valley (Figure 1). Just below the site, three modern districts—Antioquía, Cuenca, and Lahuaytambo—share the boundaries of their fields. This boundary corresponds with the main productive lands in this section of the valley and remains, to this day, a prime location for fruit cultivation. Historical and ethnographic sources (Salomon and Urioste Reference Salomon and Urioste1991; Spalding Reference Spalding1984) locate Ampugasa as part of the Langasica waranqa and the ayllu of Avichuca. Before the Inka period, this ayllu likely migrated from the region of Santo Domingo de los Olleros (more than 15 km away), which was a hub for ceramic production and distribution during colonial and republican periods (Quiroz Reference Quiroz1981:21–33). As expected, Ampugasa is not a substantial settlement; only a few families of the same ayllu may have moved there to ensure direct control over the productive valley bottom.

Figure 1. Location of the modern Huarochirí province, including the location of the waranqas and Ampugasa.

Site Description

Architectural structures in Ampugasa extend over two peaks and the hillsides (Figure 2). The entrance to the site is from the south, through eight rectangular compounds scattered along the eastern hillside. There had possibly been more compounds, but modern electrical infrastructure may have destroyed them. Each compound (measuring ~17 × 9 m) had one or two entryways that did not share a uniform orientation and enclosed between four and eight smaller rectangular structures. Through excavation, we confirmed that the enclosed structures had high walls and most had two stories. Considering that access to the site was from the south, the Inka period structures likely provided an imposing view for outsiders coming into the site, thereby materializing the narrative of imperial control.

Figure 2. Plan view of Ampugasa with excavation units. (Color online)

Moving north through the compounds, a sequence of terraces containing the slope, and creating new flat surfaces for construction, lead to the first peak and the rock outcrop.Footnote 1 The outcrop has an approximate area of 400 m2 and was surrounded by a small plaza that followed the hilltop's contour, with an approximate area of 280 m2. Five curving rows of flat steps funneled movement toward the outcrop's apex. We found several looted funerary structures peppering the face of the outcrop and at the top. These structures consisted of small rectangular chambers roofed with slabs and were accessible through a small window in one of the longer walls. A stairway likely connected the top of the outcrop to the eastern cliff.

North of the outcrop is a narrow and constrained natural corridor between the peaks. Along the corridor were remains of aboveground burials leading to the main funerary structure in the flat section between the peaks. Despite intense looting, the structure stands with most of its walls more than 1 m tall; it also shows evidence of a second story. This structure is unique: most other funerary structures found were located within household spaces, whereas this one stood without any other associated building. Its location, the fact that it corresponded to the earliest occupation period of the site, and its formal characteristics (discussed later) suggest that the people interred here may have been ranking community members within Ampugasa or even ancestors.

North of the funerary structure is the earliest residential sector. The structures were circular or elongated with rounded corners. Small, irregular patios connected the circular structures and created communal spaces. The rooms did not have a single orientation; instead, accessways connected the structures among themselves or to the central patios. Most structures had an average diameter of 4 m; rectangular rooms with rounded corners could measure up to 6 × 3 m. In one of the patios, we found a large millstone (approximately 1 m in diameter), which suggests that stages of food preparation and potential consumption were carried out in the patios rather than inside the houses. We did not find evidence of pigment remains or metallic slag that would suggest another function.

Passing through to the north is the second peak, where we excavated a circular plaza (approximately 11 m in diameter) surrounded to the east by small subterranean cists. The western cliff is delimited by more retaining terraces, some of which were associated with structures. Within the plaza, there are five large rectangular boulders with evidence of wear. These types of boulders resemble the standing stones used as ritual markers, commonly known to Andean scholars as huancas.Footnote 2 Their location and weight suggest they may have originally stood in the center of the plaza.

Despite its location on a hilltop, we found no evidence of defensive traits in the architecture or slingshots, mace heads, or any type of weaponry. My results in Ampugasa support Feltham's (Reference Feltham, Eeckhout and Fort2005:135–136) observation that most residential settlements in Huarochirí were emplaced on hilltops to maintain visual connections with sacred mountains in the landscape, rather than as a defense mechanism.

Chronology of Occupation in Ampugasa

Stratigraphy in Ampugasa was shallow, with maximum depths reaching no more than 30 cm, except when rockfall comprised a significant layer. We defined the occupational sequence through six AMS radiocarbon dates (two human bones, one shell, two samples of organic residue attached to ceramic sherds, and one corn cob).Footnote 3 I completed the calibration in OxCal 4.3.2. For calibration of the shell, I used the Marine 13 correction curve. I estimated the reservoir effect in consultation with the Marine Reservoir Correction Database (http://calib.org/marine) and used the Callao Bay collection from the Smithsonian Institute (the closest published source from my research area) reported by Jones and colleagues (Reference Jones, Hodgins, Dettman, Andrus, Nelson and Etayo-Cadavid2007) as a proxy. For the rest of the samples, I used the SHCal13 atmospheric curve, which corrects the limitations of IntCal13 for the Southern Hemisphere (Hogg et al. Reference Hogg, Hua, Blackwell, Niu, Buck, Guilderson, Heaton, Palmer, Reimer, Reimer, Turney and Zimmerman2013; Marsh et al. Reference Marsh, Bruno, Fritz, Baker, Capriles and Hastorf2018). The results showed a continuous occupation, with earliest dates in the funerary area and circular domestic structures, and later dates in the rectangular compounds. The dates support excavation results and are consistent with the shifts in architectural layouts. I present a detailed description of the dates in Table 1.

Table 1. AMS Radiocarbon Data for Ampugasa.

Although there is no hard date for the arrival of the Inka in Huarochirí, based on colonial documents, most scholarship has dated this period around AD 1450–1500 (Dulanto Reference Dulanto, Silverman and Isbell2008:764). However, recent research suggests earlier dates for the Inka expansion throughout the Andes (Greco Reference Greco, Scaro, Otero and Cremonte2017; Gyarmati and Condarco Reference Gyarmati, Condarco, Alconini and Covey2018; Ogburn Reference Ogburn2012). In addition, the lack of absolute dating for the latter parts of the Andean sequence makes it difficult to define a chronology of Inka conquest in different Andean regions. My excavations suggest the Inka conquered Huarochirí before AD 1450.

The earliest dates recovered are from the funerary area that stands between the two domestic components. The samples came from two individuals in a communal funerary structure and are very consistent, with MU-010 having a median of 1349 AD and MU-011 a median of AD 1344. The dates are well into the Late Intermediate period and well before any Inka presence in the central coast valleys. However, more excavations and systematic dating in the region are required for a better temporal resolution. Because the funerary section is associated with the rock outcrop of Ampugasa, I consider them contemporary elements in the ritual core of the site. This model supports the critical role of ancestrality in claiming ownership of the territory and belonging to the landscape (Salomon Reference Salomon and Dillehay1995:321).

The dates from the circular structures (MU-016 and MU-018) partly overlap with the dates from the ritual core and continue to the early fifteenth century. The range connects the pre-Inka period of Huarochirí with the earliest arrival of the Inka in the region. Consequently, I interpret the circular domestic structures as the original houses of the population of Ampugasa. The excavation results (which I discuss next) confirm their domestic use. The dates likely correspond to the ritual closing of the structures and the initial move toward the rectangular compounds.

Finally, the dates from the rectangular compounds immediately follow those from the circular structures. The contexts of the dated materials correspond to the use of the compounds as residential spaces and straddle the Late Horizon or Inka period and the early colonial period.

Excavation Results

The ritual core of the site—the rock outcrop and funerary structure—was the earliest part of the site and was never abandoned. The constructions in this area inform our understanding of local buildings and layouts, and I discuss them first. Then I address excavations in the pre-Inka (circular structure) and Inka period (rectangular compounds) residential areas. I excavated a single patio group from the circular structures and one compound of the rectangular Inka period houses. The excavation areas were representative in form and dimension of other residential units in the site. Finally, I discuss what the shift in houses and the sacralization of local residential space may have meant for the residents of Ampugasa and Inka imperial policies in Huarochirí.

Excavations in the Ritual Core

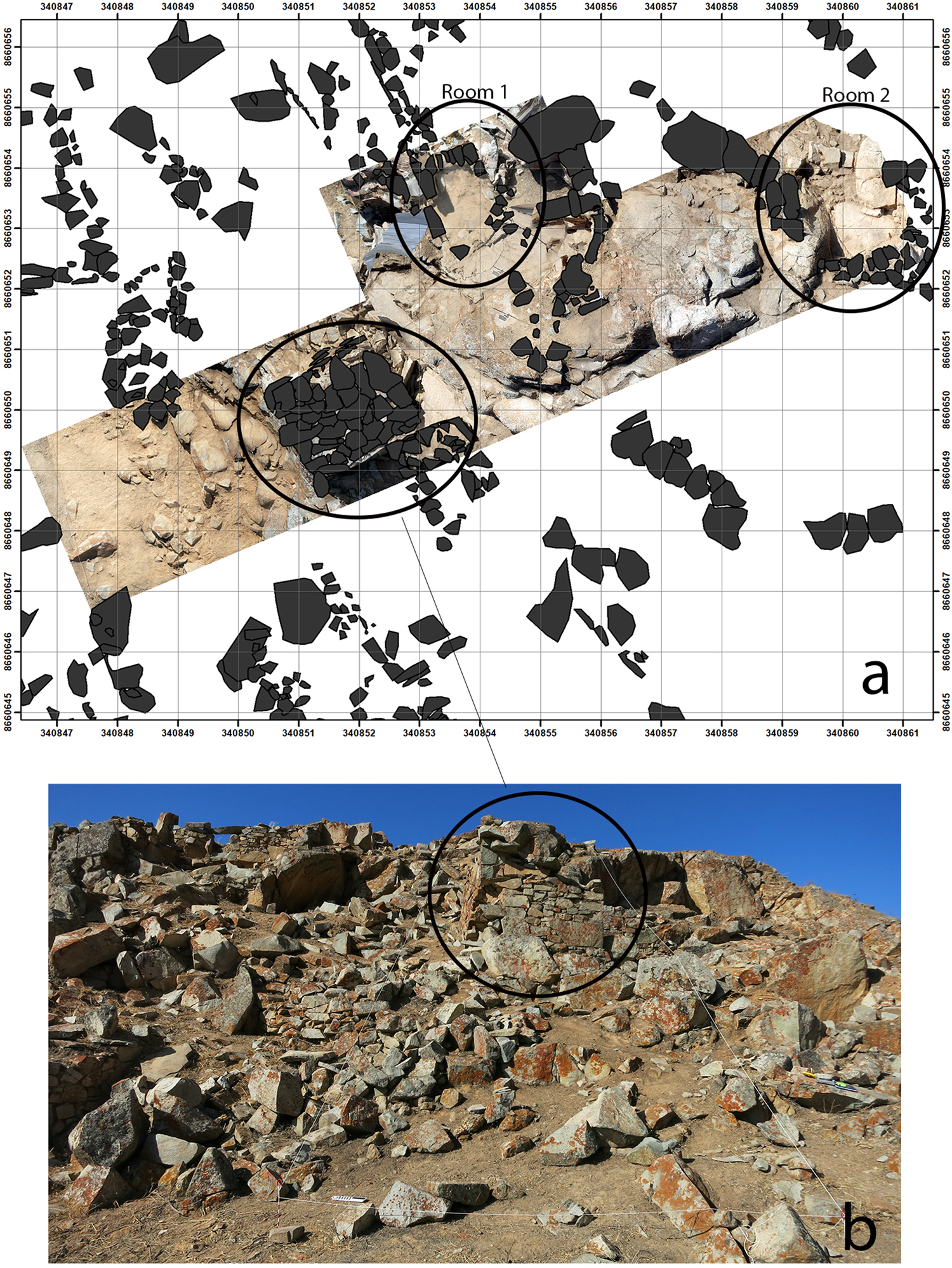

In the outcrop, we excavated a 15 × 3 m trench from the top to the base of the plaza (Figure 3). The plaza section did not yield many remains, because the use surface was already exposed, with limited portions covered by rockfall. However, we confirmed that several rectangular structures roofed with slabs had a funerary function. One such room (Room 1) measured 1.6 × 1.2 m with a northwest-to-southeast orientation. We recovered human remains belonging to three individuals: one adult (only hand and feet bones, clavicle, and patella), one child between three and four years old (a tooth, vertebrae, ilium, some ribs, and phalanxes), and one perinatal individual (cranium fragments, vertebrae, and coxal, humerus, and hand bones). The sparseness and type of remains suggest the bodies were originally buried there and then moved to another location. However, we do not know when this movement took place. The location of burials in the outcrop seemingly supports the emphasis on kinship as a central aspect of sociality within Ampugasa. We obtained more evidence supporting this observation by finding a nearby freestanding, multichambered funerary structure approximately 25 m from the rock outcrop.

Figure 3. Plan view of the rocky outcrop, with (a) the excavated trench and location of associated structures and (b) a view from the lower edge of the trench. Photograph courtesy of Proyecto Arqueológico Sierras de Lurín. (Color online)

In the standing funerary structure, the external walls were thicker than most of the other walls in the site (~50 cm), with the preserved wall in the northwestern corner rising to 1.5 m (Figure 4). We identified four connected rooms, with the two largest ones accessible through a corridor. Although the extensive looting of these rooms prevented their excavation, we recorded brown coarse ceramic sherds and beads from the spillovers, which suggest that the individuals in the chambers once had a distinct funerary attire. We excavated in the smallest and best-preserved chamber. We recorded at least 19 individuals: 11 adults, 5 children, 2 infants, and 1 perinatal. The individuals were initially flexed, with their backs resting against the walls; we found imprints from basketry in some of the soil clods that suggest that the bodies rested on a mat. The only associations found in this chamber were ceramic fragments probably used in the mortar and one shell pendant.

Figure 4. Photographs of the (a) funerary structure, (b) the corridor connecting the chambers, and (c) recovered artifacts. Photographs courtesy of Proyecto Arqueológico Sierras de Lurín. (Color online)

The burial is the earliest dated context on the site. We dated this burial through samples from two of the individuals within the chamber. The bodies seem to have been undisturbed. Interestingly, we found Inka-style sherds associated with local-style sherds in the spillover of one of the looted chambers. Two potential interpretations are possible. First, the Inka may have superimposed their ancestors in one of the chambers of the funerary structure. However, neither excavations nor historical sources from the region suggest the physical presence of Inka officials living in Ampugasa to support this reading. Second, the vessel could have been added to a previous burial by local community members as an offering after the Inka conquest.

From this perspective, the physical transformations of domestic space brought about by the Inka conquest at Ampugasa are not necessarily associated with fundamental changes or limitations placed on local ritual practices at the collective level. The inhabitants of Ampugasa would have had access to this ritual core after the Inka conquest and after the settlement had shifted into new domestic spaces. The maintenance of these spaces and the engagement of Inka culture with the local ancestors could suggest that the empire accepted—and even encouraged—the practices that made the people of Ampugasa Pariacaca's children. In this sense, the embedded message of communal memory and ancestrality communicated by the freestanding funerary chambers associated with the rock outcrop persisted after the Inka conquest. Rather than being erased, the semantics of the message—the people of Ampugasa were children of Pariacaca—was expanded to incorporate the new, additional relationship between the Inka and the ancestral deity.

Excavations in the Residential Areas

There are two residential areas in the site: the earliest circular houses to the north and the Inka period rectangular compounds in the southern hillside. The circular structures had low-rising walls made with unworked stones and perishable organic roofing, and they were connected through internal patios (patio groups). After the Inka conquest, the circular houses were ritually closed, and new buildings were erected. The rectangular compounds resembled the carefully selected and worked walls of funerary areas, rather than the masonry of the circular structures (Hernández Garavito and Osores Mendives Reference Hernández Garavito and Mendives2019:848–850).

We excavated three circular connected structures (Figure 5). The stratigraphy was shallow and included a level of modern vegetation, followed by evidence of structural collapse (rockfall, mortar patches, and windblown soil), before reaching the floor level and its associated features. We also continued excavations below the floor and into the bedrock, discarding the presence of previous occupational levels. One of these rooms (Room 3) had no observable features on the floor level and seemed to have been cleaned before abandonment.

Figure 5. (a) Plan view of the circular structures; (b) possible mochadero. Offerings recovered included a textile sword (c), quena (d), and pendant (e) associated with the burial. Photographs courtesy of Proyecto Arqueológico Sierras de Lurín. (Color online)

In Room 1, we found a series of burning events on the floor. The most substantial ash accumulation laid directly on the access to the room. Within the ash, we recorded abundant faunal remains, including the radius of a single guinea pig (Cavia porcellus), and Artiodactyl remains (see the later discussion). Of the total remains of this feature, 46% of the bones had evidence of burning, and only 4% had cutmarks (in terms of portions, we found cuts in two ribs and two feet). We recovered various parts of the animals, suggesting a cooking event directly connected to closing access to the structure. We also found artifacts such as a quena (pan flute) and a textile sword. This enclosure was the only location where we found similar artifacts.

Excavations in Room 2 further support the interpretation of a ritual closing of the circular structures. The main feature of this room is a centrally placed boulder of 1.4 × 1.2 m, with an abutting standing slab 1 m tall, creating a chair-like form. The form of this feature is consistent with what colonial period documentation refers to as stone “altars,” or mochaderos. The term mochadero comes from the Quechua muchay cuni, which refers to the act of reverence (González Holguín Reference González Holguín1989 [1608]:246). Mochaderos were the specific natural or worked rocks where acts of reverence, offerings, and libations took place.

In Ampugasa, the location of the mochadero within domestic space suggests that it was likely used in household-level rituals. A posthole on the floor of the room hints to partial roofing with organic materials. On top of three flat slabs on the mochadero, we found human remains of five individuals, with ages ranging from a fetus to a one-year-old child. We found remnants of red pigment on the cranium and over the long bones. Imprints of basketry suggest the bodies were positioned in a small mat, and we recovered four malacological pendants as part of the context. At the foot of the mochadero, we found a layer of ceramic sherds covering the structure's floor. We collected a total of 8,920 g of sherds. Only 85 were considered diagnostic and were analyzed. Although the sherds were coarse and undecorated, their careful placement supports the intentionality behind their deposition. Noticeably, none of them were either Inka style or connected to other local styles of the Late Horizon.

I hypothesize that these three rooms were part of the dwelling of, at least, an extended household unit. As mentioned, Room 3 was cleaned. In Room 1, the ash lenses suggest the burning of offerings (such as the quenas) and possibly the last episode of sharing food within the newly closed circular houses. Room 2 served as the location of household-level rituals. The human remains found in the mochadero were likely moved from another context at the time of the closing and as people moved to the rectangular compounds. Covering the floor of the room with ceramic sherds further shows the careful process of closing.

In the rectangular compounds, we conducted excavations in one of the better-preserved structures in the eastern hillside, which has an area of 128 m2. The compound comprised nine rooms, of which we excavated four (70 m2). We could not find the access to the compound, which was likely close to the fallen northern corner. Inside the compound, we found evidence of two-story structures and several means of access connecting all the rooms (Figure 6).

Figure 6. (a) Plan view of the rectangular compound and (b and c) room details. Photographs courtesy of Proyecto Arqueológico Sierras de Lurín. (Color online)

Unlike the circular structures, we uncovered evidence in the rectangular compounds for their period of use, rather than abandonment. The function of Room 1 is hard to pinpoint. It could be a resting area, albeit with some evidence of cooking. We did not recover artifacts that indicated artisanal functions, such as textile implements, pottery wheels, or polishers. In the middle of the eastern wall, we found an accessway leading to a small corridor connected to Room 5. Although the floor was clean, we found evidence of at least one slab protruding from the western wall that could be evidence of textile production (as a support for a waist loom). However, we did not find spindle whorls or textile remains. Nor did we find physical evidence of specialized activity areas in the circular structures, which could further support a move toward concentrating household activities in a single space.

Three accessways leading to different parts of the compound support the interpretation of Room 5 as a foyer. Through the northeastern entryway, we accessed an area with two facing two-story storage units, which had been heavily destroyed and looted. Passing through the storage units, we reached Room 9 to the northeast. Here we found remains of several burning events associated with nearly complete cooking pots. We found a bench abutting the western wall, which probably served for other activities. In the corner of this bench, we found remains from a colonial period midden, which suggests that the room was clean and in use at the time of the site's abandonment. I propose that Room 9 replaced the patios that connected the circular structures as spaces for interaction. Most domestic activities could now be contained in each compound, which directly transformed spaces of interhousehold interaction to intrahousehold interaction.

To substantiate whether temporal shifts in the architectural layout corresponded to shifts in domestic practices, my team and I investigated potential changes in the locations where subsistence goods were processed and used. The most readily available faunal remains for consumption recovered from the excavation correspond to the Artiodactyl order, which includes camelids and deer. Camelids were the most-represented species of the sample, and we recovered evidence for most body parts. Carlos Osores Mendives examined the evidence of cutmarks and burns on camelid remains.Footnote 4 In Table 2, I report the proportion of the sample from the whole population analyzed. In Supplemental Table 1, I present the detailed account of the specific Artiodactyl remains recorded per residential area and loci.

Table 2: Quantification and Distribution of Mammals and Artiodactyl Remains in Ampugasa.

Notes: NISP: Number of identified specimens; MNI: Minimal number of individuals.

Looking at these remains, we found that in the rock outcrop, the earliest part of the site, a large percentage of the bones had cutmarks and little evidence of burning (Table 3). However, faunal remains are scarce in the ritual core of the site. Inside the domestic circular structures, there is less evidence of cutmarks than in the outcrop, and burned fragments are slightly more represented than unmodified ones. It is possible that for the closing ceremony, food processing took place in a communal area like the outcrop or even the patios, and then the discarded remains moved to the closing contexts. Cooking together is one of the most common activities recorded in Andean extended households, and sharing food is a well-recorded aspect of Andean sociality (Bray Reference Bray2003b; Curtright Reference Curtright2013). The care and time investment in the closing (for example, laying the floor with ceramic sherds) and the great ritual importance of the offerings (for example, the offering of the children on the mochadero) suggest that the abandonment of these residential spaces would not hinder communal activities but rather create a momentous occasion for interaction.

Table 3: Distribution of Cutmarks and Burned Elements per Skeletal Portion of Camelids.

Finally, in the rooms we excavated in the rectangular compounds, we found no evidence of cutmarks, but one-third of the bones were burned. The area identified as an internal patio showed a surface space with lenses of ash and poorly preserved floors, which suggest that cooking took place in situ. During the Inka period, household cooking took place within the bounded compound. Although community feasting may have taken place in central spaces like the outcrop (and likely cleaned afterward), our findings suggest that daily cooking occurred within residential walls. The stark difference between cooking in the patios linking the circular structures and the compounds is apparent when considering the height of the walls and the intentional curtailing of visibility for non-household members. Still, other activities, like butchering or processing food before cooking, are not represented in our findings and may have occurred in more communal locations.

From a state perspective, I suggest that the significance of this new form of dwelling went beyond transforming household activities and hindering interhousehold interaction. The shape and physical separation of the compounds likely facilitated the demographic control of the site's residents. The shifts in architecture and masonry in Ampugasa align with findings suggesting that the Inka actively reshaped the “face” of residential sites, using imposing architecture as a materialization of imperial power (Acuto and Leibowicz Reference Acuto, Leibowicz, Alconini and Covey2018). These shifts may say more about the nature of Inka administration and the specific imperial narrative they aimed to convey in the provinces than reflecting an active attempt to shift interaction within and among households. For instance, whether intentional or not, the ritual closing of previous houses and their closeness to the ritual core would have reinforced rather than negated the importance of community identity and broader regional narratives among the inhabitants of Ampugasa.

Conclusions: Abandonment, Sacralization, and Community

In this article, my goal was to investigate whether the residential shift from traditional patio groups to rectangular compounds in Ampugasa reflected an interplay between continuities and transformations of local practices after the Inka conquest of Huarochirí. This pattern in residential settlement is generally acknowledged in the specialized literature as a means for the Inka to resolve potential conflicts by hindering horizontal integration (Ogburn Reference Ogburn2008) and materializing Inka power in local built landscapes (Acuto Reference Acuto, Silverman and Isbell2008). My work in Ampugasa expands this premise to question whether the on-the-ground material evidence of how the shift from one residential space to another, and the practices carried out by the residents, conform to an idea of radical change as a consequence of imperial imposition. I argue that even a visible and tangible change in the site's residential history is embedded in local worldviews and everyday experiences that sought to construct the Inka into a kin lineage and transform, rather than abandon, the practices and activities that served to maintain community interaction and collective identities.

In Huarochirí, interpretations of the HM and earlier archaeological work (Chase Reference Chase, Alconini and Covey2018; Hernández Garavito Reference Hernández Garavito2020) demonstrate that Inka transformations in the region relied heavily on local practices. Moreover, the Inka's incorporation into local traditions suggests that both Inka imperial policies and local attempts to retain agency after becoming part of the empire were mediated by local material culture. On a domestic scale, I argue that the ritual closing of pre-Inka houses and their persistence as a visible and experiential element go against expectations that the erasure of community practices and memory was at the center of the Inka reshaping of lived space. The results from excavations at Ampugasa show that, even though the shifts in residential layouts conformed to those recorded in local sites across the Andean highlands during the Inka period, these shifts on their own did not lead to an erasure of local community practices and identities. In other words, imperial spatial practices at the domestic level in Huarochirí were grafted onto local lifeways and enshrined local identity.

Continuity and transformation are irrevocably connected (Roddick and Hastorf Reference Roddick and Hastorf2010). In Ampugasa, in the shift from circular to rectangular structures, we can see both imperial transformation and the local enactment of Inka policies (Acuto and Leibowicz Reference Acuto, Leibowicz, Alconini and Covey2018). However, and unlike in other published case studies, in Ampugasa, pre-imperial residential spaces were ritually closed and remained standing. The experience of transforming indigenous residential spaces into sacred spaces through their ritual closing memorialized the community's recently experienced past during and after the Inka conquest of Huarochirí. There is no evidence that the Inka hindered access to the site's ritual core (the rock outcrop); incorporation of Inka material culture into the most singular and likely important burial of the site further demonstrates an interplay between the old local practices and the new Inka ideas and materials. Ultimately, negotiation of the Inka into local community forms was likely less costly to the empire than a complete revamping of the communal organization of a population that did not resist their annexation.

Although there was a modification in residential space, there seems to be no shift in ritual practices and spaces, which further supports this interpretation. Some activities, like cooking, may have changed to the intrahouse level, but other activities, such as food processing, may have still taken place in the interhouse level. Consequently, although new architectural layouts may have led to some activities becoming encapsulated in domestic space, the intention behind the move may not have been as simple as constraining household interactions. Other activities may have offset potential ruptures: by reinventing domestic life and transforming previous houses into sacred spaces, the Inka were not denying previous community ties but grafting their residential practices onto them.

In briefly discussing the potential shifts in meat processing from the patio groups to the residential compound, I aimed to demonstrate that Ampugasa's residents performed the same activities they had before the conquest but in new spaces. Although some areas of daily interaction (the patios) may have moved from open to restricted spaces, not every activity took place within the house and was limited to specific intrahousehold interactions. In presenting a microanalysis of life in Ampugasa before and after the Inka incorporation, I aimed to demonstrate that further exploration of the on-the-ground mechanisms of Inka imperialism at the residential level will provide critical insights into the agency of and construction of community identities among their subjects.

Acknowledgments

My initial work in Ampugasa benefited from the advice and support of Tom Dillehay, Steve Wernke, and Krzysztof Makowski. Kasia Szremski, Scotti Norman, Gabriela Oré, Keitlyn Alcantara, Grace Alexandrino, Paul Christians, and Kevin Vaughn generously gifted me their time by reading the initial draft. This article greatly benefited from the comments of three anonymous reviewers. Their advice was invaluable, yet all errors remain my own. Martha Palma completed the bioarchaeological analysis. The Peruvian Ministry of Culture authorized excavations in Ampugasa with Permit No. 256-2015-DGPA-VMPCIC/MC granted to me. Fieldwork funding came from a Wenner-Gren Dissertation Fieldwork Grant, an NSF Doctoral Dissertation Improvement Grant, and internal grants from Vanderbilt University. The initial draft of this article was completed while I was a Chancellor's Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of California, Riverside (2019–2020).

Data Availability Statement

Raw counts and weights of materials, as well as a description of the excavations, are reported in my doctoral dissertation (Hernández Garavito Reference Hernández Garavito2019) freely available online through ProQuest. The collections excavated from Ampugasa are currently stored in the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru and are in the process of being turned over to the custody of the Peruvian Ministry of Culture.

Supplemental Materials

For supplemental material accompanying this article, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2020.91.

Supplemental Table 1. Detailed Distribution of Artiodactyl Remains per Loci.