Although the US preserves a dominant position in Latin America, China’s growing influence in the region poses economic and political challenges and has set up a potential battle for the hearts and minds of the populace. Such a battle would imply that increasing support for China comes at the expense of the United States, but there is an alternative: Latin Americans could eschew the international rivalry and judge the two outside powers independently. Only in the first of these cases would the views of the two countries necessarily covary. Covariance in views toward China and the United States, then, is a symbol of whether the international rivalry has been internalized by the Latin American public.

Latin America’s citizenry developed its views toward the United States over the many decades of US hegemony. Those views, however, could change as the public begins to come to terms with the new international competitor reshaping the economic structure of the region. Debates about Latin America’s economics, which used to be dominated by discussions of the region’s trade deals and dependence on the United States, IMF loans, and the role of USAID, are now focused on China’s purchase of raw materials and the opportunities and consequences of Chinese investments in infrastructure. The shifts in the Latin American economies have been dramatic, with China having displaced the former quasi-monopsonist as the prime buyer of soybeans from Argentina and Brazil, copper and copper ore from Chile and Peru, and frozen beef from Uruguay, among other products. China’s foreign investment in the region has also skyrocketed, such that it has now established a clear physical presence (Reference EllisEllis 2014). Concomitant with trade and investment, China has worked to curry favor in the region by building diplomatic relations (Reference StruverStruver 2014) and “strategic partnerships” (Reference EllisEllis 2018), selling arms and building ties to the region’s militaries (Reference LodoñoLodoño 2018), investing in infrastructure, offering huge loans with favorable terms (Reference Gallagher, Irwin and KoleskiGallagher, Irwin, and Koleski 2012),Footnote 1 using aid to build legislative buildings and sports stadiums (Reference EllisEllis 2014), and even employing journalists in the region and setting up media outlets to generate positive popular opinions (Reference Lim and BerginLim and Bergin 2018).

These activities have not fully upended foreign policy orientations (Reference StruverStruver 2014; Reference Flores-Macías and KrepsFlores-Macías and Kreps 2013)—and not all citizens have been convinced—perhaps owing to general concerns with a “new dependency” as well as specific revelations about highly publicized projects that have had enormous social, environmental, and economic costs (Reference GallagherGallagher 2008; Reference Gallagher and PorzecanskiGallagher and Porzecanski 2010; Reference Wise, Myers, Myers and WiseWise and Myers 2016; Reference EllisEllis 2018). In any case, adding China to the equation challenges US hegemony—and perhaps views about the United States—by providing evidence of the benefits (and costs) of working with the international competitor.

China has been rising while US involvement in the region has been attenuating. Not always by its own design, the United States no longer has its USAID missions in some countries, it has been forced to close down military bases, and, while the United States maintains some allies, anti-US presidents have held power in multiple countries during this period of China’s rise. It has not helped that US officials continue to treat Latin America with a lack of respect or perhaps disdain, as evidenced by Secretary of State Tillerson’s 2018 revival of the Monroe Doctrine (see Reference Barrios and CreutzfeldtBarrios and Creutzfeldt 2018).

The long relation of the United States and the countries “below” (Reference SchoultzSchoultz 1998) has given Latin Americans ample time to form opinions, negative or positive, about their northern neighbor. Contributing to the charged attitudes is a history of infamous and heavy-handed intervention, with examples such as the incitement of the overthrow of governments in Guatemala and Chile, covert support for violent civil wars in Central America, a controversial and adversarial stance toward Cuba, and a war in which Mexico lost about half of its territory. In the economic realm, many blame dependency on the United States for the region’s poor economic development or criticize other US economic policies directed toward the region, such as forcing countries to impose unpopular debt reduction plans (Reference Stallings and KaufmanStallings and Kaufman 1990; Reference Roett, Hartlyn, Schoultz and VarasRoett 1993; Reference NaímNaím 2002; Reference StiglitzStiglitz 2002). These negative attitudes toward the United States are central planks in the campaigns of the region’s leftist politicians. The right views many of these events differently. For them, the US has supported order and fought socialist or communist threats (Reference SmithSmith 2012).

Perhaps orthogonal to the attitudes based on US interventions in the region, personal and cultural ties have likely contributed to a positive view of the northern power. Recently the high levels of violence in Mexico and Central America have pushed migrants north, and more generally the US is an aspiration for many in Latin America owing to its geographic contiguity plus its stable democracy and stronger economy. With around fifty million Latinos in the United States, countless millions in Latin America have financial and cultural ties with friends and relatives in the North.

The shifting role of the two powers in the region, within a context of historical US engagement plus China’s recent impacts on those economies, yields three potential hypotheses about Latin Americans views toward the two rivals. First, Latin Americans could see China as a rival to the United States. In this case, perhaps owing to ideological views or perspectives on governmental forms, those who hold negative views about the traditional power might welcome the new challenger, and those who see the United States in a positive light might reject China. The second hypothesis is that Latin Americans might view the two powers similarly. This positive covariance could be driven by the idea that the United States and China are interchangeable foreign powers, with similar impacts on the region’s environments and economies.Footnote 2 Both those who criticize foreign investors as well as those who see the benefits of attracting foreign capital, for example, may not differentiate the source of the funds.

The third hypothesis, which we show is most consistent with our data, is that feelings toward the two countries are unrelated. This result could obtain if different factors drive attitudes toward the two countries. We argue, alternatively, that it obtains because while Latin Americans’ attitudes toward the United States are structured by ideology and other factors, they are not well structured with respect to China. Perhaps the sorting of views toward the United States in accord with political ideology is a result of the long experience, for better or worse, between the United States and its southern neighbors. China, meanwhile, had minimal relations with the region until the 1990s, and only in the last two decades has it ramped up its economic relationships. Politically it still maintains a lower profile. Owing to this more limited experience, it seems reasonable to hypothesize that Latin Americans have not yet formed strong opinions about China. But, because we find that there is not much difference in citizens’ willingness to put forth responses about their attitudes toward the two countries, and attitudes toward China are not overly positive (or negative) in the region, we differ with Armony and Velásquez (Reference Armony and Velásquez2016), who argue that Latin Americans are in a honeymoon with China, and with Aldrich and Lu (Reference Aldrich and Lu2015) who suggest that Latin Americans might be “intrigued by the ‘new kid on the block.’”

Our alternative explanation for why attitudes toward China are mostly unrelated to traditional explanatory variables is that there have been contrasting consequences of the new relations and that China has been successful in attracting support from a variety of corners; it appeals to the left for its ideological and anti-American stands while appealing to the right for its influence on the economy (Reference Brand, McEwen-Fial and MunoBrand, McEwen-Fial, and Muno 2015; Reference Dussel PetersDussel Peters 2005). At the same time, for cultural, social, economic, and environmental reasons, both the left and right may have reasons to be wary of China. Perhaps China’s ability to attract some support from multiple audiences in Latin America also shows frustration or ambivalence about democracy (Reference Cohen, Lupu and ZechmeisterCohen, Lupu, and Zechmeister 2017) and that democracy is not an ideological cleavage.

To evaluate the Latin Americans’ views toward China and the United States, and the covariance thereof, we evaluate three survey questions. The questions ascertain how the region’s residents view (1) the influence of those powers in their own country, (2) the trustworthiness of the two powers’ governments, and (3) if China or the United States (rather than another country) would provide the best model for development. We use these questions first to show that there is tremendous regional variance in the attitudes, especially with respect to the United States. More important for our purposes, at neither the country nor individual level do the data show strong covariance, either positive or negative. Given the lack of covariance, attitudes toward the two countries cannot share a common underlying causal factor. In this case, we show that factors such ideology and other variables explain attitudes toward the United States, but there are no clear correlates with attitudes about China.

In searching for evidence to explain the attitudes, we statistically explore five issues. First, given that China’s rise not only challenges the United States in terms of economic but also political hegemony, we evaluate whether Latin Americans’ ideological predispositions drive attitudes about the rivals. Are those on the left more inclined to show more affinity for China? The second query is whether strong democrats are inclined to state more positive feelings toward the United States, and vice versa. Third, do cultural ties with the United States hamper views about China? The fourth question is whether people in countries where China has had a greater economic impact are more likely to express positive sentiments toward that country, and, perhaps, disparage the United States. We also test the corollary, about the relation of attitudes and economic ties to the United States. Finally, do Latin Americans’ views about the potential tradeoffs between economics and the environment drive their attitudes toward China and/or the United States?

As we have implied, these hypotheses—most interestingly that related to ideology—have support in the data with respect to the United States, but they largely fail in tests about attitudes toward China. This failure explains the evident lack of covariance in attitudes, and it is owed, we argue, to China’s support, though still middling, coming from diverse sectors of society. Whether or not gaining the diverse support has been a result of an intentional strategy, it could propel China’s rise, given that the region faces continued economic pressures in the context of increased polarization.

Data and Methodology

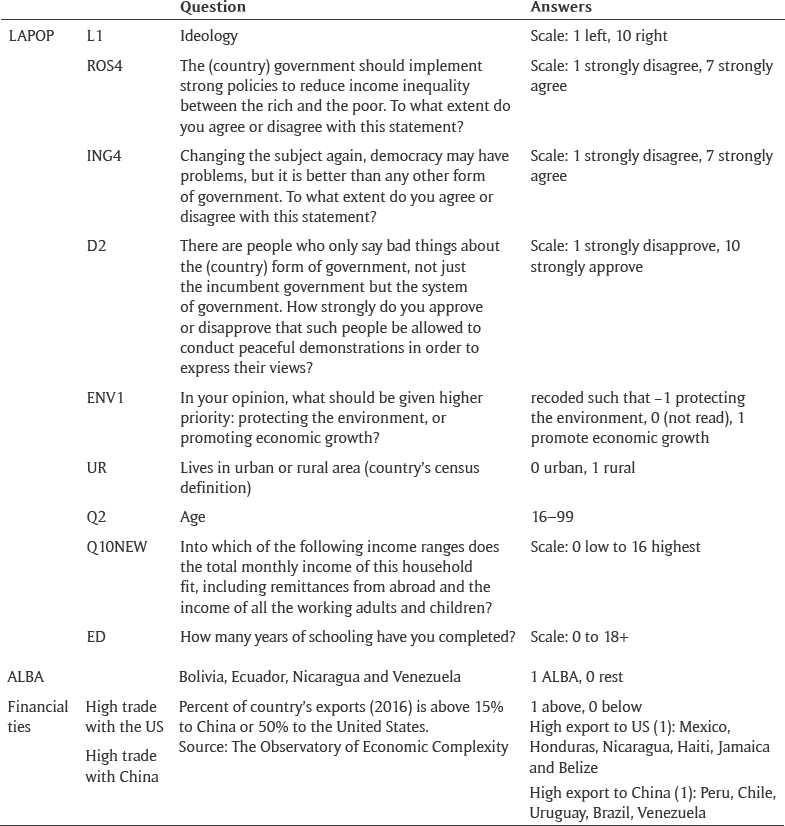

To investigate the Latin American views about China and the United States, we rely on the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP), a comprehensive survey conducted for most of the region’s countries since 2004. Here we focus on the approximately twenty thousand observations and twenty countries of the 2014 wave, when the survey provided three questions from which to judge the attitudes toward the two powers.Footnote 3 Table 1 provides the precise questions for our study.

Table 1: Questions in LAPOP about the opinion on US and China.

To assure that these questions do offer different vantage points for assessing attitudes, we ran several correlational analyses which show that sizeable minorities did not have consistent views about the questions (Appendix Tables 1–2). As examples, only 32 percent who rated the influence of the United States negatively graded that country’s government as untrustworthy, and only 43 percent who rated the influence of the US positively chose that country as the best model for development. Similar patterns hold with respect to views toward China. The bottom line is that the three questions tap different aspects of respondents’ attitudes.

A Lack of Covariance at the Country Level

We begin the analysis at the country level. For the questions about influence and trustworthiness, Figures 1 and 2 therefore plot, by country, the percentage of survey respondents who responded with favorable views toward each power. Figure 3 counterposes the percentages choosing China or the United States as their favored development model. The figures first indicate that in most Latin American countries there are more people holding positive views toward the United States,Footnote 4 and that the range of such views is wider with respect to the United States. For example, while the populations in Bolivia, Chile, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Nicaragua, Paraguay, and Venezuela all have a similar proportion (about 40 percent) of their citizens expressing positive views about the trustworthiness of the Chinese government, the corresponding proportions with respect to the US government are sprawled across almost the whole range of the graph (from 40 percent to 75 percent). Largely as a result of several Central American countries where a larger than average proportion of citizens express positive attitudes toward both China and the United States, plus Argentina, which is a low-end outlier, the lines running through the scatters in the first two graphs do indicate some positive relation. But because there is limited variance with respect to China, those lines are still relatively flat (and would be much more so without the outliers). In short, albeit with a few exceptions, favorable responses about the United States do a poor job of predicting attitudes toward China.

Figure 1: Trustworthiness of US and China governments (LAPOP questions MIL10A and MIL10E). Combined responses that indicated the governments were either somewhat or very trustworthy. Includes Don’t Know (DK) and No Response (NR) in the denominator.

Figure 2: Positive opinion about the influence of US and China (LAPOP questions FOR7 and FOR7b). Combines responses for “positive” and “very positive.” Includes DK/NR in the denominator.

Figure 3: Best country as model for future development: US and China (LAPOP question FOR5). Includes DK/NR in the denominator.

With an even flatter (but negatively sloping) regression line, Figure 3 supports similar findings about more predisposition toward the United States, more limited variance with respect to China, and as a result, limited covariance in views toward the two countries.Footnote 5 On average 12 percent chose China and 30 percent chose the United States as the best development model, and only in Bolivia was China the preferred of the two options. As in the previous figures, this graph reveals a weaker correlation at one end of the scale than at the other. Specifically, where the US model is most popular, few respondents picked China as their most preferred model, but of the four countries where the lowest proportions chose the United States, two rank low (Uruguay and Argentina) and two rank high (Bolivia and Ecuador) with respect to the likelihood of picking China.

In sum, the country-level analysis suggests weak patterns with respect to the covariance of views. Given these weak correlations, it does not appear that geopolitics cleave Latin Americans’ attitudes with respect to the two powers. We test this, as well as the influence of ideology and several other variables, at the individual level in the next section.

Individual-Level Analysis

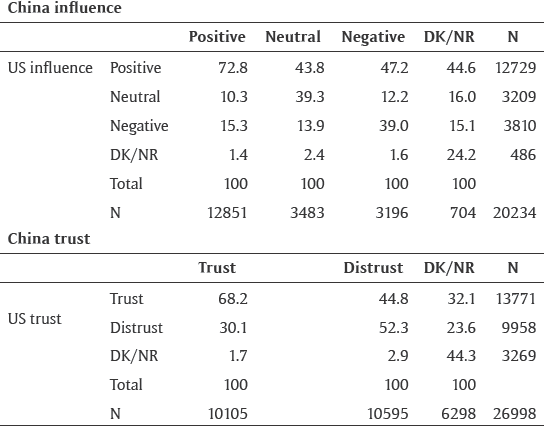

Validating the country-level assessments, tests at the individual level yield an emphatic finding of positive but weak relations. A correlation coefficient relating views of the trustworthiness of the two governments is about 0.24 and about 0.23 for views about those countries’ influence (excluding nonresponses). Table 2 details the correlations. As an example, 73 percent of the citizens who viewed the Chinese influence as positive judged the US similarly, and the other side of the diagonal yields 39 percent. Similarly, 68 percent who say they trust China also trust the United States, while 52 who distrust China express a similar view about the United States. It would be overstated, however, to argue that there is a strong positive correlation in these views, as almost half who judged the Chinese influence negatively gave the US a positive ranking (and 15 percent who scored the Chinese as a positive influence judged the US as a negative influence). The off-diagonals with respect to the question of trustworthiness yield a similar conclusion: relations are positive but weak.

Table 2: Correlations in views: Individual-level data.

Source: Elaborated using LAPOP questions FOR7, FOR7b, MIL10A, and MIL10E with weighted responses. Combined responses for very trustworthy and trustworthy, very positive and positive influence, and parallel negative responses.

Hypotheses: Drivers of Latin American Views about China and the United States

In order for views about China and United States to covary systematically, the variables explaining views toward one of the countries must also affect, positively or negatively, the views toward the other. The covariance would be positive if the Latin Americans see China as a complement, and negative if they view China as an alternative or rival. There would be no covariance if different variables explain attitudes toward the two counties—or, as we find, there are no clear correlates with attitudes toward one of the countries.

Ideology, international relations, and the market

The first potential explanatory variable is ideology, which is founded on the rival powers’ divide with respect to the role of the state in the economy. At least since the Cold War there have been ample examples of dramatic conflicts—in Cuba, the Southern Cone, Central America, and recently in Venezuela—pitting the United States against left-leaning leaders and movements in Latin America. Perhaps owing at least in part to this history, leftists in the region are also wont to denigrate the United States for its economic activities in the region. Dependency, the 1980s debt crisis, and the general lack of economic progress in the region continue to fuel anti-Americanism, particularly on the left. This view is not circumscribed to Latin America, with Chiozza (Reference Chiozza2010) showing in worldwide tests that an “antimarket worldview” and anti-Americanism are conjoined. Azpuru and Boniface (Reference Azpuru and Boniface2015) provide a statistical test to confirm that relation for Latin America (see also Reference Almonds, Samuels, Levitsky and RobertsAlmonds and Samuels 2011).

While the left in Latin America disparages the United States, the political right has been supported by the United States in most internal political battles, and many of the elite have financial and familial ties to the United States. Still, at the time of the survey that we study, the United States had a Democratic president, which could have led Latin Americans from the right to indicate wariness about the United States. This suggests a possible nonlinear relation for the ideology variable, but our main expectation is that leftists will align with anti-Americanism and vice versa.

The Latin American left’s anti-Americanism could give the Chinese an opportunity to gain favor by providing a positive alternative for economic development. Given their preference for greater state involvement in the economy, affiliates of the left might endorse the Chinese model, and their wariness of the United States could yield a predisposition of the left to side with that county’s political rival. This would be consistent with the findings of Aldrich and Lu (Reference Aldrich and Lu2015) or Carreras (Reference Carreras2017) that citizens living in Bolivarian Alliance (ALBA) countries, where there are more strident leftist presidents and strained ties with the United States, are more likely to express positive attitudes toward China.Footnote 6 Accordingly, rightists who support the United States and the neoliberal model should be wary of China. These assumptions aside, Armony and Velásquez (Reference Armony and Velásquez2016) find that ideology does not explain Latin American attitudes toward China (see also Reference Tokatlian, Roett and PazTokatlian 2008). This result could be consistent with Ellis (Reference Ellis2009, 2) who notes that Chinese businesses target all parts of Latin America, regardless of their economic model and that “the hope of [exporting to China] is virtually ubiquitous in the region.”

In sum, while we expect ideology to correlate with attitudes toward the United States, we are dubious that such a relation will hold for China. We test the role of ideology in several ways. At the individual level we evaluate two survey questions: the first uses respondents’ self-placement on a ten-point left-right ideology scale (question L1; 1 = left) and the second asks the degree to which respondents agree that the state should implement policies to reduce inequality (ROS4; 1 disagree; 7 agree). We complement these questions with a categorical variable that separates residents of ALBA countries (1 = yes).

H1: The left will espouse more negative views toward the United States and vice versa. Ideology should have a more limited impact on views about China.

Democracy

Related but distinct from left-right semantics, the issue of democracy could drive a wedge in views about China and the US. While strong democrats should be wary of China’s authoritarian regime, always rhetorically, and sometimes programmatically, the United States has long promoted democracy in the region (Reference SmithSmith 2012; Reference KaganKagan 2015; Reference Maisto, Millett, Holmes and PérezMaisto 2015). This would lead to a hypothesis that those most supportive of democracy would exhibit more support for the United States and less for China.Footnote 7 Chiozza’s (Reference Chiozza, Katzenstein and Keohane2007) study of anti-Americanism provides a basis for this hypothesis. While he does not include Latin America in his study, he finds that those who espouse “democratic ideas and the customs that America embodies” are more likely to have a favorable opinion of the United States.

The democracy variable, however, might not correlate with attitudes toward the United States, because while Washington has rhetorically favored democracy, it has often supported right-wing movements and dictatorships. A poignant example was the US support of the failed 2002 coup against Venezuela’s popularly elected Hugo Chávez. This and other US-supported coups in the region, as Baker and Cupery (Reference Baker and Cupery2013) remind us, frequently have significant support among Latin Americans. Those who are dubious of democracy, therefore, might still be supportive of the United States, and thus we might not find an unambiguously positive relation between views about democracy and support for the United States.

The LAPOP survey offers several questions to test this hypothesis. The first (ING4) asks whether democracy is better than any other form of government, using a seven-point scale (1 = disagree). The second question (D2) asks respondents to use a ten-point scale (1 = disapprove) to indicate whether they approve of critics using “peaceful demonstrations to express their views.”

H2: Support for democracy and the right to protest will be positively (but perhaps not strongly) correlated with attitudes toward the United States and negatively toward China.

Cultural relations

Especially about the United States, cultural relations should influence the Latin American’s views. In spite of the conflictual history, an impressive percentage of Latin Americans view the US positively (Reference Baker and CuperyBaker and Cupery 2013; Reference SillimanSilliman 2014). In part this is due to their seeing the United States as an aspiration. Perhaps the positive counterparts of the heavy-handed intervention, which include international aid, cultural exchanges, and trade relationships, have also led some to view the United States in a positive light. The pervasiveness of US culture—which traces back to the highly publicized visit of Walt Disney in 1941 and is now evidenced by the ever-present US films, fast food restaurants, music, and style—has certainly created familiarity. At least for many, this could translate into a positive view.

China does not have the lengthy cultural or migration ties with Latin America, which leads Creutzfeldt (Reference Creutzfeldt2016, 32) to label cultural affinities in the region with China as “thin.” He also cites Dussel Peters (Reference Dussel Peters2006) in noting “a growing racism towards Chinese,” and Carreras (Reference Carreras2017) finds that China suffers from “cultural misunderstanding” in the region. At the same time, China has made significant efforts to woo Latin America, not only through the economic projects but also with high-level state visits of Chinese leaders and reciprocal invitations for Latin American leaders. China has also attempted to build cultural links through its Confucius centers, sister-city relations, and other mechanisms (Reference EllisEllis 2009). Stallings (Reference Stallings, Myers and Wise2016) further argues that China has used aid to build a positive image and gain economic opportunities. Cheng (Reference Cheng2006, 524) adds that while “the vast distance between China and Latin America generates difficulties in transportation and mutual understanding, it also means that both parties have no serious conflicts of strategic and political interests.”

To test the impact of cultural affinity, it would be useful to have questions about relatives abroad or travel, but LAPOP has only asked such questions in Ecuador and Guyana. While imperfect, the best individual-level question about cultural affinity toward the United States and China is the one we use as an alternative dependent variable: Which country ought to be the model for future development for your country?Footnote 8 We thus test the importance of responses to this question with respect to our other dependent variables, with the (strong) expectation that:

H3. Those who choose the United States as the best model for development will trust that country’s government and see its influence as positive, and the expectations for choosing China correspond. Unless attitudes toward the two countries do covary, respondents’ pick for the best development model will not affect views toward the rival country.

Economic influences

Next, if economic concerns drive Latin Americans’ views toward their largest trading partners, a positive covariance in attitudes toward China and the United States could obtain if trade with or foreign direct investment from one is seen as a supplement to that of the other. If the region’s citizens see China as a replacement for the United States, then the covariance would be negative.

The strength of these ties varies considerably across the region. The economic bonds include aid, loans, and remittances, but levels of trade provide a clear proxy that shows, for example, the integral relation of Mexico and Central America with the North.

China’s patterns of engagement with the region have been somewhat different, and the recent high-profile involvement could generate even stronger opinions. Beginning from a very low level, China began purchasing larger amounts of Latin American primary products and investing in the region’s economy around 2000. Trade between China and Latin America grew by more than 1500 percent, from $16 billion in 2001 to almost $280 billion in 2014, and investment has seen a similar level of growth (Reference Jenkins, Peters and MoreiraJenkins, Dussel Peters, and Mesquita Moreira 2008). Dussel Peters and Armony (Reference Dussel Peters, Armony, Xirinachs, Peters and Armony2018) find that this growth has translated into significant job creation in the region. Parallel to those changes, Latin American real per capita income began to rise in about 2004, moving from its stagnant level of about $5,800 during the previous decade to $7,500 in 2016.Footnote 9 Importantly, this comes after decades of stagnation, and the positive growth is often attributed to China’s growing purchases of material from and foreign direct investment in the region.

Latin Americans also have potential bases from which to criticize Chinese involvement in their region. Many investment projects have had highly publicized negative environmental impacts, aroused suspicions of corruption (Reference González-VicenteGonzález-Vicente 2012; Reference Irwin and GallagherIrwin and Gallagher 2013), and construction often uses Chinese rather than domestic labor. While, as noted, Dussel Peters and Armony (Reference Dussel Peters, Armony, Xirinachs, Peters and Armony2018) tell of the overall growth in the region’s employment, they also explain that some is of low quality, and some countries (notably Mexico) or sectors have not benefited. Finally, a recent report by the Economic Commission on Latin America and the Caribbean (2018) provides a different caveat; China’s Belt and Road initiative has spurred much infrastructural investment, but 93 percent of this spending has gone to countries with large petroleum reserves, and some accords require these countries to sell the oil to China (CEPAL 2018, 22). Gallagher, Irwin, and Koleski (Reference Gallagher, Irwin and Koleski2012) sound a related concern; with 61 percent of loans going to Ecuador and Venezuela in 2010, it appears that politics, oil, and finance are closely related.

The role of the economy suggests two tests. The first uses an objective variable. The expectation is that closer economic ties with a power should improve attitudes toward it (Reference Baker and CuperyBaker and Cupery 2013). Investment data is so unreliable that Dussel Peters (Reference Dussel Peters2018) reported that for some countries the difference in what China and the receiving country report can be 300 percent. We thus test this expectation using trade data, grouping countries on the basis of the percent of trade going to the respective powers (+/– 50 percent exports to the United States; +/– 15 percent exports to China).

The subjective variable we test is a three-option survey question (ENV1) which asks whether the respondent prefers protecting the environment (–1), promoting economic growth (1) or both (0). Here our expectation is that citizens who lean toward growth will espouse more positive attitudes toward both foreign powers, while concerns for the environment should incline them in the other direction.

H4: Stronger economic ties (measured in terms of exports) will yield more positive attitudes toward the corresponding country. If attitudes toward the two countries do not covary, then strong economic ties with one country will not affect views about the other.

H5: Citizens who express strong preferences for supporting the economy over the environment will have favorable views of both the United States and China, and vice versa.

Age, education, income, and urban/rural status

Beyond our main variables of interest, our models include measures of age, education, income, and rural/urban status. We do not emphasize these variables, but as they have theoretical value, we do not consider them as simply controls. First, we test the idea that younger voters, because they did not personally experience the height of US interventionism in the Cold War, might have more positive opinions about the United States than their elders. This is consistent with the finding of a Pew Research Center study (2014) about world attitudes toward the United States and China, and also tracks Magaloni (Reference Magaloni2006), who explains that the youth in Mexico had a more negative view toward their long-standing ruling party because they had not experienced the many positive years of their rule (see also Reference ChiozzaChiozza 2010, 111). For education and income we would expect that more educated or wealthy voters would have more nuanced views about, for example, the role of foreign direct investment in their countries (Reference Ahmed, Bastiaens and JohnstonAhmed, Bastiaens, and Johnston 2015; Reference Kleinberg and FordhamKleinberg and Fordham 2010). They might also have more contact with the United States; Martínez i Coma and Lago Peñas (Reference Martínez i Coma and Peñas2008) hypothesize that this leads to more positive views. Next, while urban Latin Americans might feel the positive benefits from greater exports of their minerals, those from rural areas might consider both jobs and environmental degradation (see Reference Garriga and VidellaGarriga and Vidella 2015).

In sum, Latin Americans have ample reasons to hold strong views—perhaps positive or negative—about the United States, based on the power’s long history of intervention in politics and influence in the region’s economic development. China has not had such a long history in the region, but its meteoric rise as a central player in the Latin American economies clearly challenges the US dominance in that realm. We have shown that that rivalry is not clearly evident in the attitudes of the region’s citizens, and our tests below explain this outcome by showing that traditional variables such as ideology and economics explain attitudes toward the United States but not toward China. We interpret the failure to explain views about China as the result of the diverse attractions to and concerns about the new power cutting across ideological and other divides.

Multivariate Models and Results

We test our hypotheses via pooled regression models, with standard errors clustered by country. Given that the data is hierarchical, we also ran a series of robustness checks with models that include (a) random country intercepts, and (b) fixed effects or dummy variables for each country. The results of these models, which can be found in our online appendices, show very similar substantive effects as those in the pooled regressions. Data and necessary information for replication is available from the authors or at our websites.

Given that the different survey questions have different structures, each requires its own form of multivariate models. The simplest model is for trust in the two governments. The questions code four responses, from very trustworthy to untrustworthy but without neutral, and we collapse the extreme and moderate responses (and drop the “don’t know” and “no response” options) into positive (1) and negative (0) categories, to aid interpretation. This allows a standard logit model (and, as noted, hierarchical and fixed effects forms). The question about the powers’ influence does include a neutral option, and thus we ran a three-category ordered logistic regression (1 = negative; 3 = positive). Finally, the survey question about which country provides the best model for development asks respondents to choose among multiple countries, thus necessitating a multinomial logit. In that model we pool all responses other than China and the United States into an “other” category. Tables 3 and 4 provide the results.

Table 3: Predicting opinions about government trustworthiness and the countries’ influence.

Note: /1 Logit models; /2 Ordered Logit models.

*** p ≤ 0.01; ** p ≤ 0.05; * p ≤ 0.1.

Table 4: Predicting China and the US as the best model for development/1.

Note: /1 Multinomial logit using “other” as base category.

*** p ≤ 0.01; ** p ≤ 0.05; * p ≤ 0.1.

As foreshadowed, the first regressions include five groups of independent variables: ideology, views about democracy, affinity for the US or China as a development model, economic ties, and concern with the environment, plus demographics (Appendix Table 3 provides the definitions). The regressions testing for respondents’ favored development model are similar, except they necessarily lack a proxy for cultural affinities. We tested for collinearity among several variables (e.g., income and education or the two variables testing ideology) but found almost none. We thus include all variables in the reported results.

To interpret the substantive significance, Table 5 provides the marginal effects of the variables of primary interest, showing the change in favorable views with respect to each dependent variable given a maximal change in each of independent variables (while holding other variables constant). Given the differences in the statistical and substantive significance of some of the variables across the different models, the regressions confirm that the dependent variables capture different images about views toward the US and China.

Table 5: Substantive impacts*.

* Coded for probability of favorable views.

In terms of the hypotheses, there are six findings. The first clear result is that ideology is statistically and substantively significant (in the expected direction) only with respect to the United States. Specifically, the four most northwestern values in Table 5 predict that moving from the extreme left to extreme right leads to an eighteen-point increase in the likelihood of responding that the US government is trustworthy, while the same move only changes the probability of giving China a positive nod by just (negative) four points. Models for the other dependent variables tell similar tales. The second independent variable, which captures ideology by asking respondents about the role of the state in reducing inequality, shows only small effects.

For the trustworthiness and influence questions, the ALBA variable, which also captures ideology and geopolitics, again shows a strong impact on perceptions about the United States but almost no impact on views toward China. Specifically, the predicted likelihood of giving a favorable view about trustworthiness of the US government or influence of that country falls sharply (–20 and –14 points, respectively) for residents of ALBA countries, while it changes (negatively) by just one or two points for both questions concerning China. For the question of “most favored development model,” the model continues to signal a large negative impact for ALBA membership on views about the United States, but it does find a significant and opposite effect on views about China, although it is still only half the size of that for the counterpart.

Third, results for the variable measuring support for democracy are statistically significant in the trust models, but the substantive effect is small. The variable coding tolerance for demonstrations was statistically insignificant in most regressions and substantively insignificant in all (and thus not shown in the table).

Fourth, our proxy for cultural ties showed, unsurprisingly, a strong positive relation between choosing a country as a favored development model and views toward that country. More interestingly, the results contribute to our expectation of a lack of a tie between views toward the United States and China, because choosing the United States as a favored development model has almost no impact on views toward China, while choosing the Eastern power as the favored development model has a small but positive impact on attitudes toward the Westerner. Since geopolitics do not bifurcate individuals, we have more evidence against the covariance hypothesis.

Fifth, the categorical trade variables provide a bit of support that the international rivalry could generate negative covariance in citizens’ attitudes, given that high trade to China reduces positive views about the United States, with effects ranging from seven to nine points. However, that variable has only mixed effects on views about China itself, with a negative correlation of high trade and trustworthiness of that country’s government. To confirm these results, we examined the bivariate relationships and found remarkable consistency in views about China regardless of the level of trade (Table 6). Trade with the United States, meanwhile, has marginal effects that range from small to moderate on attitudes toward both countries.

Table 6: Trade and views about China.

* Includes neutral category, which is not shown.

Sixth, the regressions show that those answering that they prefer to promote growth over protecting the environment are a bit more likely to judge the influence of both China and the US positively. The effects are too weak, however, to support overall covariance in attitudes toward the two powers. Since foreign investment in Latin America affects rural and urban communities differently, we tested the urban dummy variable in tandem with views about the environment/economic tradeoff. The results, however, are small and inconsistent.

Finally, the demographic variables (some of which we have left off the table) had some significant impacts, but they did not generate correspondence between the two countries. Older citizens were less likely to choose the United States as their preferred development model, but the effect was minimal with respect to China. The model also suggests that age somewhat reduced the likelihood of indicating that China’s influence was positive, but the variable does not affect how they will view the US influence. Income had a negative relation with the likelihood of picking either the US or China as a favored development model, but even going from the lowest to highest income bracket only produced a five-point change in predictions for the United States and less for China. The education variable, finally, yields conflicting impacts, with a greater likelihood of trusting both countries’ governments, little impact on the influence question, and contrasting impacts on choosing those countries as the favored development model.

Are Attitudes toward China Ill-Formed?

The previous discussion showed that views toward the United States are more clearly determined by ideology and other variables than are views toward China. Is this because voters have not yet defined their attitudes toward the newer power, or is it, as we contend, that China attracts voters from across the political spectrum? In defense, we provide three pieces of evidence, focusing on the data for those who did not respond or answered that they did not know when asked about trust or influence.

The most straightforward piece of evidence for this idea is that there was not an unusually large number of Latin Americans who scored the United States on these questions but failed to qualify China.Footnote 10 For the question about the influence of the two powers, only about 3 percent failed to give answers with respect to either China or the United States. More did fail to respond about the trustworthiness of the governments, and the difference is significant: about 11 percent more failed to respond about the trustworthiness of the Chinese government than about the US government, but this is still too small a difference to sustain the idea that citizens are generally unable to discuss China while they have solid ideas about the United States. Stating the response rates in the affirmative makes this point more emphatically: while 88 percent of Latin Americans provide a view about the United States, 77 percent of those citizens also do so for China.

Second, there is not an ideological skew among those failing to affirm a view about China, thus confirming earlier findings and suggesting that China will not be burdened by geopolitical divisions as it continues to make inroads in the region.

Third, as shown in Table 2, almost half of those who did not give an affirmative answer with respect to China’s trustworthiness did the same with respect to the United States. That value falls to one-fourth for the question about influence, but this is misleading since there were so few people (2.4 percent) who did not rank the two powers’ influence.Footnote 11

To answer the question posed in this section, the “don’t know” and “no response” data do not support the idea that the weak relation of ideology (or other variables) with attitudes about China is the result of Latin Americans not yet having formed opinions about China. Instead, that analysis confirms that Latin American views toward China are unrelated to ideology.

Conclusions

The long and contested history between the United States and its southern neighbors has resulted in Latin Americans forming strong and opposing views about the North. As we have shown, these polarized views are evident at the country and individual levels, with some, especially from the right, seeing the United States as providing opportunities for economic and political progress and others, especially on the left, focusing on economic dependency, military intervention, political pressures, and opportunism. Our data considering views toward China show relative consistency at the country level, and thus geopolitics or ideology have little variance to explain. Individual-level data corroborate the inability of these or other variables to accurately foretell attitudes regarding China. Since our models only explain attitudes toward one of the powers, attitudes between the two of them cannot covary, either positively or negatively.

The data we analyzed in this project came from 2014, and LAPOP has now published some results for the Trump years. The 2018–19 data show, unsurprisingly, that confidence in the US government plummeted across the region, but—in support of our thesis about the lack of covariance—support for China was up in some countries (e.g., by 17 points in Argentina) but down in others (e.g., by 10 points in Chile). Preliminary investigation shows that our other finding, that ideology explains support for the United States but not for China, also continues to hold. For example, among leftists in Brazil, 74 percent found the US government untrustworthy while they split almost 50/50 in their views about China.

Why do ideology and other variables fail to explain attitudes toward China? Our tests showed that most citizens do offer opinions about China, and thus this pattern is not explained by a lack of information. Instead, the failed models seem to be a function of China’s appeal across the ideological spectrum. While the appeal should not be overstated, because significant numbers do not judge China positively, the new regional power has been equally successful in winning support from the left, presumably for ideological and geopolitical reasons, and from the right, presumably for economic opportunities and growth.

In sum, then, the lack of variables strongly linked with attitudes toward China does more than explain the lack of covariance in attitudes toward the two powers: it also suggests that the Chinese have not generated ideological opponents. Has this been a concerted and intentional strategy? Given the region’s polarized politics and its economic needs, a diverse support base could help China to continue its rise. This concern led us to explore legislators’ views in a companion paper (Reference Bohigues, Morgenstern, Alcántara, Montero and PérezBohigues and Morgenstern 2020) revealing similar findings. However, future research will need to establish a link between attitudes and policy.

Appendix

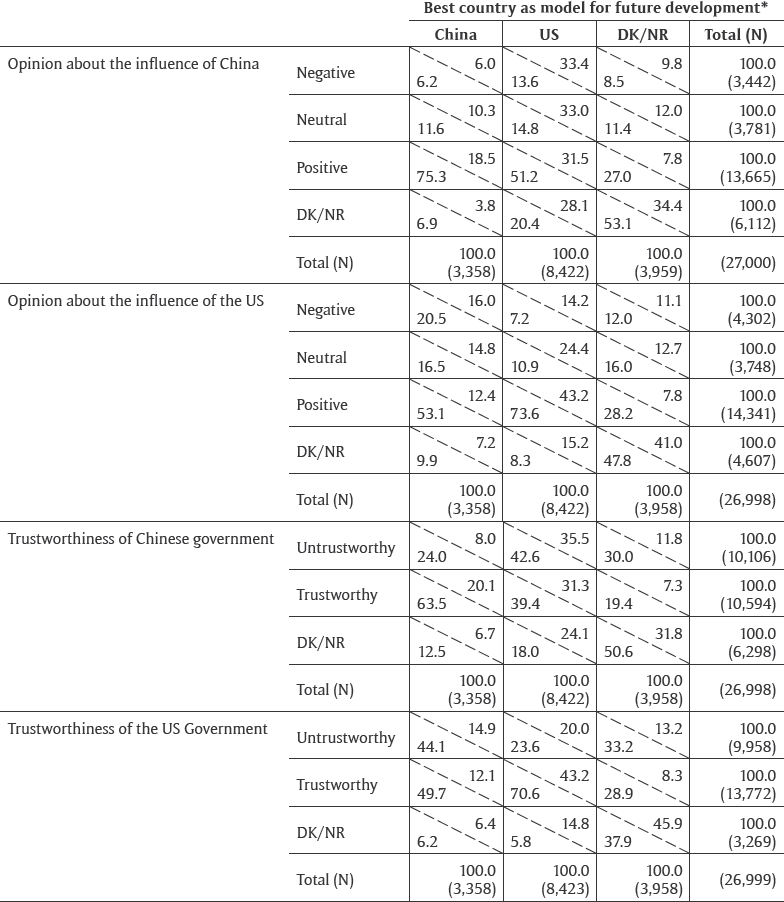

Appendix Table 1 Opinion about the influence of US/China vs trustworthiness of US/China government.

Source: LAPOP Questions FOR7, FOR7b, MIL10A and MIL10E.

Notes: Column percentages in lower row; row percentages in upper row.

Appendix Table 2 Best country as model for future development vs. Opinion about the influence of US and China and trustworthiness of US and China governments.

Source: LAPOP questions FOR5, FOR7, FOR7b, MIL10A and MIL10E.

Notes: Column percentages in lower row; row percentages in upper row.

Differences in the total N due to the weighting in the database.

* Does not include the rest of possible answers for the best model for future development question.

Appendix Table 3 Independent variables.

Appendix Table 4 Unformed opinions*.

* Percent of respondents answering DK/NR. For “influence” question, only considers respondents who answered previous question about the degree of influence of the respective power.

Additional File

The additional file for this article can be found as follows:

• Online Appendix. Alternative Models. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.656.s1

Acknowledgements

We thank, in particular, Samuel Talman for providing invaluable research assistance.