In 1913, 38-year-old Sakharam Ganesh Pandit informed the Superior Court of the State of California for the County of Los Angeles that he was a “free White person,” according to his skin color, high-caste status, Aryan ancestry, and race science. Pandit also submitted evidence of at least 5 years of residency in the United States. The Indian immigrant was in the process of finalizing his petition to naturalize as a US citizen by proving that he met the requirements stipulated in naturalization law.Footnote 1

At its birth as a sovereign nation, the United States required an immigrant to be a “free white person … of good character” if they sought to naturalize.Footnote 2 The all-White male Congress enacted this racial prerequisite in the nation's first federal naturalization law in 1790, underscoring the founding legislators’ efforts to codify Whiteness within the law, facilitate the settlement of a White nation, and enforce White supremacy. Following the Civil War, Congress amended federal naturalization law by extending naturalization to “aliens of African nativity and to persons of African descent.”Footnote 3 Congress designed the amendment to retain racial eligibility within federal naturalization law, to thwart naturalization attempts by non-European immigrants, particularly Chinese immigrants, as Congress attempted to recast the nation's racial prejudice against Black Americans and immigrants.Footnote 4 These changes in federal naturalization law gave non-African and European immigrants the option of naturalizing as African natives or descendants, or as White persons.

Between 1878 and 1952, US federal courts adjudicated fifty-two cases pursued by immigrants from Syria, Korea, the Philippines, China, Burma, Armenia, Japan, India, Hawai'i, and Mexico who sought to naturalize as US citizens by proving to US courts that they were indeed White. Their arguments solicited a range of rulings from US judges that underscored how immigrants’ contestation of racial categorizations challenged the founding legislators’ efforts to integrate White supremacy into law. When Pandit appeared in court to complete his naturalization proceedings, he encountered a puzzled Judge William Morrison. Morrison was uncertain if Indian immigrants were eligible to naturalize as US citizens based on their race, since judges across the United States made different rulings on whether Indian men constituted White persons, or persons of a different race such as Mongolian, Asiatic, or Hindu.Footnote 5 Witnessing Morrison's hesitancy, Pandit shared that he needed to naturalize to qualify for the California bar and practice law in the United States. At the time, most states required individuals to be US citizens to qualify for the bar. On hearing Pandit's woes, Frederick Jones, the naturalization examiner in Pandit's case, informed Pandit that “the Judge [was] going to take a little time so that the door may not be thrown open to such as are not desirable.” Several weeks later, Judge Morrison naturalized Pandit, ruling that the immigrant “represent[ed] the highest type of the Hindu race, its culture and thought, and apart from the question of color or race is in all respects qualified for citizenship.” Even the most anti-Asian organizations were drawn to Pandit's accomplishments and status. For example, the San Francisco Call, the press organ of the Asiatic Exclusion League (AEL), an umbrella organization for labor groups dedicated to preventing Asian immigration, underlined Pandit's accomplishments as a college graduate, lecturer, law student, and “man of the Brahmin caste.” It also revealed Judge Morrison's praise for the remarkable nature of Pandit's legal brief to the court.Footnote 6

The racial classification of Indian immigrants preoccupied judges and bureaucrats across the United States until 1923, when the US Supreme Court agreed to review Indian immigrants’ eligibility to naturalize as US citizens. The US Supreme Court unanimously ruled that Indian men did not constitute White persons in United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind.Footnote 7 Following the Supreme Court's ruling, the Department of Justice (DOJ) attempted to denaturalize all Indian men who had gained US citizenship, as well as their families, by claiming they had naturalized “illegally.” The DOJ's decision was among the first efforts in US history to denaturalize an entire community of immigrants and their families and cast them as illegal citizens. The DOJ's discretionary decision-making remade legally naturalized immigrants as permanent aliens.

Denaturalization proceedings brought a 51-year-old Pandit back to court in 1926. Pandit argued his case based on equitable estoppel, a defense that prevented federal courts from denaturalizing him on the basis that he had relied on his status as a citizen to such an extent that he would experience great harm if his legal status changed. Since 1913, Pandit had exercised a range of rights reserved for US citizens. He had secured admission to the California bar in 1917, practiced law, and co-purchased 320 acres of land. Pandit also married Lillian Stringer, a White woman, in June 1920.Footnote 8 The marriage was considered legal under California's existing miscegenation laws because Pandit was considered White.Footnote 9

Pandit's nearly 200-page court file defies the teleological narrative of immigrant to citizen that marks the United States' imaginary as a “nation of immigrants” and a multicultural nation.Footnote 10 His case presents an array of critical points that demand an alternative interpretation of the history of US citizenship and alienage. For example, what did the naturalization examiner mean when he noted that Judge Morrison sought to prevent “undesirables” from acquiring US citizenship? How did caste become relevant to the adjudication of race in the United States? How did the DOJ delineate illegality when men like Pandit were naturalized in US courts in the presence of court clerks, naturalization examiners, judges, and district attorneys? Why did the DOJ pursue the denaturalization of Indian men and their families, but not for other Asian immigrants not classified as White? Finally, why was it that when Pandit returned to the court in 1926 for denaturalization proceedings, key aspects of his personal, professional, and economic life were contingent on his racialization as White and legal status as a US citizen, including his profession, land ownership, and marriage to a White woman?

This article unravels an important historical conjuncture in the making of modern US citizenship and alienage by drawing on the state's regulation of naturalization as it relates to Asian immigration in the early twentieth century. It draws particular attention to Indian immigration. My primary concern is to examine the socio-legal formations that constructed the thick distinctions between the modern US citizen and alien along the lines of racial difference and racial capital. Specifically, this article argues that Asian immigration to the United States remade the modern US citizen and alien in two significant and interconnected ways.Footnote 11 First, it underscores how the adjudication of race in US courts and connected political campaigns re-mapped race in the United States and sharpened the racialization of continental Asia and Europe in profound ways that ultimately produced immigrants from southern, central, and eastern parts of Asia as the modern US alien. Second, the debate over Asian immigrants’ eligibility to naturalize refashioned legal status as a normative avenue to sustain a regime of racial capital. It cast citizenship as a legal avenue for White men and families to acquire and protect a proprietary interest in citizenship and recast some Asian immigrants as permanent aliens in a period when alienage came to signify disposable immigrant labor.

At the center of these struggles for citizenship, the legal boundaries of Whiteness and the Asiatic acquired new definitions that substantiated a national color line based on racial difference. Given that US citizenship continues to be heralded as a form of legal security for immigrants and remains a critical issue in need of political reform, this history proves invaluable for tracing the hidden hierarchies of US citizenship and alienage, their relationship to racial capital and labor, and our understandings of the emancipatory prospects of citizenship.

This article has the immense fortune of building on the rigorous work of legal scholars who have excavated the histories of racial capital, citizenship and alienage, and the construction of race in US courts. The latter body of scholarship underlines that while race has important effects and affects in our world, it is a shifting social construct, not a biological fact. Specifically, legal scholars have focused on the role of the courts in adjudicating race, particularly Whiteness as it relates to naturalization in the United States. In his insightful analysis of the prerequisite cases, Ian Haney López points to forms of evidence such as skin color, demeanor, ancestry, character, and deportment that US judges used to determine who was and was not “White by law.”Footnote 12 Sherally Munshi calls attention to the role of racial visibility and the performance of Whiteness and citizenship in the adjudication of race, while Sarah Gualtieri reminds scholars that immigrants’ attempts to be classified as White contributed to political and legal activism that spanned national borders and immigrant communities.Footnote 13 Turning to racial categories more broadly, Mae Ngai's critical interventions remind us that Whiteness was not the only racial category under deliberation in naturalization cases. Categories such as “Asian” were equally important, as were state techniques in constructing immigrants as “impossible subjects,” including “illegal aliens” and “alien citizens”—citizens who remained alien—in the United States.Footnote 14

Drawing on these insights, I offer several methodological interventions for understanding the making of modern US citizenship and alienage, and the adjudication of race in the United States by considering the relational formations of race and histories of racial capital. First, I uncover how the prerequisite cases shaped racial categories beyond White and Asian through larger relational race formations that distinguished racial differences among and between immigrant communities from Asia.Footnote 15 In federal courts and political discourse, immigrants from Asia engaged in “a possessive investment in Whiteness” to secure the legal rights to US citizenship and the life opportunities and rights afforded to individuals who fell within the bounds of Whiteness.Footnote 16 As the Bureau of Naturalization and US courts deliberated whether immigrants from Asia were White, they also distinguished which immigrants from Asia were White. Immigrant communities and multiple US bureaucracies contributed to these processes of legal adjudication on a trans-imperial scale. Just as federal judges struggled to create a precedent in case law, federal bureaucrats strived for uniformity across the nation's naturalization processes. The Bureau of Naturalization, State Department, and DOJ initially encountered the racial classification of Asian immigrants without a clear or consistent conceptual framework, even though they policed Asian immigrants’ submission of their first and second papers and oversaw their naturalization hearings.

The legal struggles of Asian immigrants, including Pandit's, remade the legal boundaries between White and Asiatic. Federal judges and bureaucrats adjudicating immigrants’ naturalization petitions created a sharp racial division between which immigrants from the continent of Asia were classified as White and which were classified as Asiatic. US courts largely constructed immigrants from more western parts of Asia as White and eligible to naturalize, while individuals from southern, central, and eastern parts of Asia were deemed not White and recategorized as the modern US alien. These legal boundaries acquired sharper definition that substantiated a new national color line based on racial difference, reconfiguring which immigrants from continental Asia were “historically ‘alien-ated’ in relation to the category of citizenship.”Footnote 17 Asian immigrants who were classified as Asiatic rather than White emerged as permanent aliens. New racial distinctions among Asian immigrants in the early twentieth century have continued to shape the contours of US racial formations, including in the field of Asian American Studies today. While Asian American Studies includes Asians from southern, central, and eastern parts of Asia, and has recently incorporated Indigenous communities and the Pacific, immigrants from more western parts of Asia receive far less attention. This disparity reveals how definitions of “Asia” and “Asian” continue to be influenced by the prerequisite cases and other sociolegal formations.Footnote 18

My second methodological intervention uses racial capital as the key socio-legal context for understanding how the prerequisite cases unfolded to remake the history of US citizenship and alienage. By racial capital, I refer to the processes by which access, acquisition, and protection of rights, goods, privileges, and legal reforms became attached to race. In her pivotal essay on Whiteness and property, Cheryl I. Harris argues that it was “the interaction between conceptions of race and property that played a critical role in establishing and maintaining racial and economic subordination.”Footnote 19 Throughout the mid-twentieth century, US citizenship was a form of legal status that provided immigrants deemed White with greater rights and privileges to capital accumulation, including but not limited to property, while prohibiting other immigrants from having the same rights and privileges.Footnote 20 The exclusion of Asian immigrants from the United States and from US citizenship was central to this process. State and federal laws on naturalization and citizenship also played an important role.Footnote 21 When Sakharam Ganesh Pandit naturalized, most immigrants did not choose to become citizens as soon as they became eligible. Rather, it was the growing distinction between citizenship and alienage, and increasingly restrictive federal immigration laws, which compelled many immigrants to naturalize. Instead of explicitly referring to race in state law, legislators across the United States expanded citizen-only laws on an unprecedented scale. Citizen-only laws stipulated “eligible to citizenship” clauses as a proxy for race to evade federal anti-discriminatory constitutional law and jurisprudence, particularly in relation to the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Examining these entanglements of race and naturalization, legal scholars of US immigration and citizenship have substantiated the historical development of citizenship and alienage in the United States.Footnote 22 In the early twentieth century, many legal distinctions between citizens and aliens were forged to marginalize Asian immigrants. These legal processes helped make the distinctions between citizen and alien equivalent to the distinctions between White and Asiatic, the historical term used to refer to Asian immigrants at the time. American studies scholar Lisa Lowe captures this historical conjuncture: “In the last century and a half, the American citizen has been defined over and against the Asian immigrant legally, economically and culturally.”Footnote 23

Building on this scholarship, my work traces how the radical transformation of citizenship and alienage established the notion that citizenship was essential for the acquisition of property, employment, and various forms of socioeconomic mobility in the United States. I reveal how the expansion of state citizen-only laws and restrictive federal immigration laws targeting Asian immigrants positioned US citizenship as a coveted legal status that offered White individuals the potential to acquire, sustain, and expand their capital while restricting non-White immigrants from these opportunities. This included but was not limited to the right to vote, own land and property, hold a professional occupation, and gain membership in professional organizations such as the American Bar Association, which mattered to Asian immigrants like Pandit. The passage of these laws imbued US citizenship with greater value as a legal status, subsequently heightening the importance of Asian immigrants’ racial classification and eligibility for US citizenship in the courts and beyond. As citizen-only laws expanded across the United States, Asian immigrants found it difficult to exercise citizen-only rights and privileges because it was harder for them to acquire first papers or gain eligibility for naturalization. Congress's passage of restrictive federal immigration laws only heightened the precarity of Asian immigrants, particularly laborers, in the United States. By eroding protections against deportation and limiting socioeconomic mobility, legislators and voters established a critical precedent in the production of a transitory and disposable labor force in the United States that targeted Asian immigrants while the nation's dependence on low-wage migratory labor grew.

The history of racial capital also provides a critical lens through which to reinterpret the remaking of legal status and who the nation believes is worthy of citizenship and naturalization reform. Just as federal immigration law offered legal exemptions for elite immigrants, including students, merchants, and diplomats, as a form of reciprocity to protect and expand US imperial interests in Asia, White judges, clerks, and naturalization examiners naturalized Indian immigrants with racial capital in the form of elite education, fiscal wealth, high-caste status, and access to White and Christian networks.Footnote 24 These decisions reflected how US officials expanded national citizenship to include the most elite Indian immigrants, with the exception of individuals who participated in revolutionary freedom movements.Footnote 25 Restrictions on the latter group reveal how US naturalization and immigration law upheld racial capital on a transimperial scale in the early twentieth century by attempting to secure the longevity of Euro-American imperialism and the continued extraction of wealth and resources across the world.Footnote 26

In the wake of Thind and exclusionary immigration and naturalization policies in the United States, more elite and middle-class Indian immigrants invoked their postgraduate education, financial status, and general socioeconomic standing as they advocated for immigration reform. Institutional organizations and political networks organized by Indian men portrayed Indian immigrants and their families as Americanized, well-educated, patriotic, and financially stable. By the 1920s, their portrayals of what kinds of immigrants were worthy of immigration reform became integral to the language of naturalization.Footnote 27 In the mid-twentieth century, newer and more elite Indian immigrants emphasized India's markets and geopolitical importance, as Congress considered immigration and naturalization reforms for Asian immigrants. These arguments elicited sympathy and close consideration from US legislators. Consequently, when Congress opened the United States’ borders and citizenship to Indian and other Asian immigrants, it expanded the entanglement of modern immigration and naturalization law with racial capital. In effect, the legal debate over Asian immigrants’ eligibility to naturalize in the United States, and subsequent immigration reform integrated racial capital as a critical component of US citizenship, alienage, and immigration and naturalization reform.

America's Non-Citizens: A Brief History

Citizenship, as a critical feature of the US imperial project, sustained White supremacy and White purity alongside racial capital. In addition to excluding most Indigenous and Black persons during the early period of conquest and slavery, the United States maintained White supremacy and an investment in racial capital through a range of local, state, and federal laws, as well as through bureaucratic tactics. As legal historian Barbara Welke shows, legal restrictions on Indigenous and Black persons and racial prerequisites of immigrants ensured that able White men alone were America's first citizens and the only subjects to maintain full legal personhood.Footnote 28 US citizenship was a highly particularized legal status rather than a liberal category of legal personhood. In subsequent years, war, US imperialism, and struggles waged by communities of color and women softened restrictive barriers to US citizenship. Following hostilities between the United States and Mexico, the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo stipulated that Mexicans in ceded territories would be naturalized as US citizens if they did not declare their intent to “retain their character as Mexicans” one year after the treaty's ratification.Footnote 29 Naturalizing thousands of ethnic Mexicans, the treaty folded newly colonized populations considered White enough into the nation's citizenry without formal consent or direct reference to race. As the United States expanded its empire across the Pacific and into the Caribbean, legislators designed what Sam Erman characterizes as “three novel, hybrid categories: lands that were neither foreign nor domestic, nonindigenous people who were neither citizens nor aliens, and domestic citizens who had less than full constitutional rights.” As US capitalists settled in colonies, these hybrid categories restricted the naturalization of newly colonized persons overseas while retaining rights and resources on the US mainland for White citizens and immigrants.Footnote 30

The first major blow to Congress's desire for a national White citizenry came in 1868 when free Black persons secured the right to birthright citizenship through the Fourteenth Amendment, the language of which restricted Indigenous communities from US citizenship on the basis of jurisdiction.Footnote 31 Two years later, in 1870, Congress created a second racial category within naturalization law, in keeping with the reforms of the Reconstruction Era, giving “aliens of African nativity and persons of African descent” the right to naturalize as US citizens.Footnote 32 The reforms were designed in response to a domestic retreat from racial equality and global concerns. The latter, as Lucy Salyer has shown, related to the right of expatriation, fraudulent naturalization papers, and immigrants’ allegiance to the United States, which European immigrants and their allies directed against Chinese immigrants.Footnote 33 A select number of Chinese immigrants were still able to naturalize after 1870, but the terms of their naturalization have yet to be comprehensively studied.Footnote 34 Drawing on a wider history of violence targeting Chinese immigrants in the nineteenth century, Beth Lew-Williams powerfully illustrates that the Reconstruction Era, known for the reinvention of the modern US citizen, was also integral in the creation of the modern alien and its “illegal” counterpart through Chinese restriction.Footnote 35

Early immigration from Asia and the ensuing racial prerequisite cases both mark an important conjuncture in the making of modern US citizenship and alienage. Asian immigrants were compelled to delineate whether they were of White or of African ancestry to naturalize as US citizens. In 1878, Ah Yup unsuccessfully argued that Chinese people were White on the basis of anthropological classifications before California's Ninth Circuit Court, which determined that “a native of China, of the Mongolian race” was not White.Footnote 36 Other Chinese immigrants followed, hoping to prove that they were White, until the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act formally barred Chinese laborers from the United States and prohibited US courts from naturalizing all Chinese immigrants as US citizens.Footnote 37 For Chinese immigrants, lifelong alienage rather than citizenship was the sequel to immigration. The 1882 exclusion of Chinese immigrants from the United States and from US citizenship did not prevent other Asian immigrants from seeking to naturalize. Immigrants from continental Asia challenged the boundaries of Whiteness in US courts, hoping to secure US citizenship and avoid the fate of Chinese immigrants.

The Legal Construction of White and not-White Asian Immigrants

The history of Indian and Asian immigration and naturalization offers a window into the complex interplay between race, legal status, and racial capital in the early twentieth century. Newspapers, local legislators, and labor unions in the United States, including the Asiatic Exclusion League, characterized the arrival of Indian immigrants as the latest iteration of an “Asiatic invasion” when they began to arrive on the Pacific seaboard in 1899. They arrived in groups of two or four, then by the dozens, and then by a few hundred each year, never totaling more than some 10,000 by the 1920s. In popular and bureaucratic discourses, Indian immigrants were Asiatics, alongside Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Filipino immigrants. The derogatory term, used by employees at the Department of Labor, marked the racial inferiority and difference attributed to immigrants from Asia. The Asiatic immigrant, unlike other immigrants, was seen as a distinct problem alongside the “Negro problem” in the US South. As one outlet put it, “There is not danger that the yellow man will displace the white man, nor that the Japanese, or the Hindus, or any other Asiatic race, will land on these shores and drive the white man across the continent into the Atlantic ocean … the danger lies in our having on this coast the same terrible problem that the South has with its negro question…”Footnote 38

Indian immigrants first filed their papers for naturalization in the early twentieth century as Asian labor immigrants experienced greater difficulty entering the United States. Officials across the Department of Labor, Census Bureau, and other bureaucracies generally agreed that Indian immigrants were ineligible to naturalize as US citizens because they did not constitute White persons. In January 1907, Hart North, Angel Island's Immigration Commissioner, wrote to Alameda County Clerk John P. Cook, insisting that “no alien [was] entitled to citizenship except he be of the White or African race,” when he learned that two Indian immigrants, Dakam and Fukur Chand, had filed their first papers for naturalization after being forced to remove their turbans.Footnote 39 The US Attorney General, Charles J. Bonaparte, also insisted that Indian immigrants were not White.Footnote 40 The Government of India and the India Office did not take any official action. Instead, James Bryce, the British ambassador in Washington, DC, simply informed the Government of India of Bonaparte's statement: “Mr. Bonaparte's ruling is advice rather than a judicial decision.”Footnote 41 The following year, the chief of the new Bureau of Naturalization, Richard K. Campbell, called attention to Asian immigrants’ eligibility to naturalize as US citizens, questioning whether they could actually naturalize at all.Footnote 42 The Bureau of Naturalization lacked the legal authority to determine the racial eligibility of immigrants for naturalization but aimed to procure a uniform system of adjudication on the racial eligibility of Asian immigrants seeking naturalization. Campbell saw the Bureau of Naturalization as an enforcement agency whose success was measured, in part, by increasing uniformity across naturalization processes in the United States and ensuring that only the most suitable aliens naturalized.Footnote 43 To facilitate this process, Campbell placed Indian immigrants at the center of the debate, hoping to limit the ability of other immigrants from Asia to naturalize. In 1908, Campbell directed district attorneys and naturalization examiners to encourage clerks of the court to accept the declarations of intention for Indian immigrants, and then challenge them if they were naturalized so that a case could move up through the courts and establish precedent that Indian immigrants were not White.Footnote 44 He then planned to target other Asian communities to establish precedent that “off-color races” should be restricted from US citizenship.Footnote 45

Indian immigrants proved an ideal target for US government officials for two main reasons. First, Indian immigrants lacked foreign diplomatic support and formidable legal and political organizations because they were a small community of imperial subjects engaged in anticolonial activism. As early as 1908, British officials colluded with the US government to restrict the naturalization of Indian immigrants as US citizens and to denaturalize anticolonial activists who had acquired naturalization.Footnote 46 They feared that prominent Indian activists could lead powerful anticolonial movements abroad.Footnote 47 In the early twentieth century, as historians Moon-Ho Jung and Seema Sohi have shown, British and US authorities developed an expanding security state apparatus as a result of anti-imperial politics led by Indian immigrants and pan-Asian political solidarities.Footnote 48 US and British immigration officers and bureaucrats worked together to disrupt naturalization and initiate the denaturalization of Indian immigrants, underscoring how legal status in the United States was routinely defined by threats to a transimperial order that sustained White supremacy.

Second, US bureaucrats like Campbell understood Indian immigrants as a middling group between White and non-White immigrants from Asia. Given that certain understandings of Whiteness were linked to geographical proximity to the Caucasus Mountains, Campbell and others understood that Indian immigrants were not designated White as easily as immigrants from west Asia, which included the Ottoman Empire. But they were not easily classifiable as Mongolian or Asiatic either, as were immigrants from parts of Asia that were farther east than India. Thus, if federal courts found Indian immigrants to be not White, immigrants from regions farther east in Asia could also be designated not White.Footnote 49

In 1909, Campbell's maneuverings within the Bureau of Naturalization and the DOJ gained public attention, leading the press to question Asian immigrants’ eligibility to naturalize as US citizens. Campbell insisted that Asiatics—including “Turks,” “Hindoos,” and other “Mongolians”—were not White because “the average man in the street” did not understand them as such. Campbell's statements were carried in newspapers across the United States and created fissures within the Bureau of Naturalization, DOJ, and State Department, which criticized Campbell's public proclamations over fears that relations with Asian countries and empires could sour as a result.Footnote 50 Secretary of Commerce and Labor Charles Nagel insisted that Campbell had misstated the bureau's position and that the matter resided with the courts.Footnote 51 The Bureau of Naturalization also drew criticism from the State Department as it negotiated a reciprocal naturalization treaty with the Ottoman Empire, and publicly announced that the issue of racial eligibility for US citizenship was a matter for the courts.Footnote 52 Still, over the next two decades, the Bureau of Naturalization continued to provide legal information to county clerks, court clerks, and judges, to influence their opinions on the prerequisite cases.

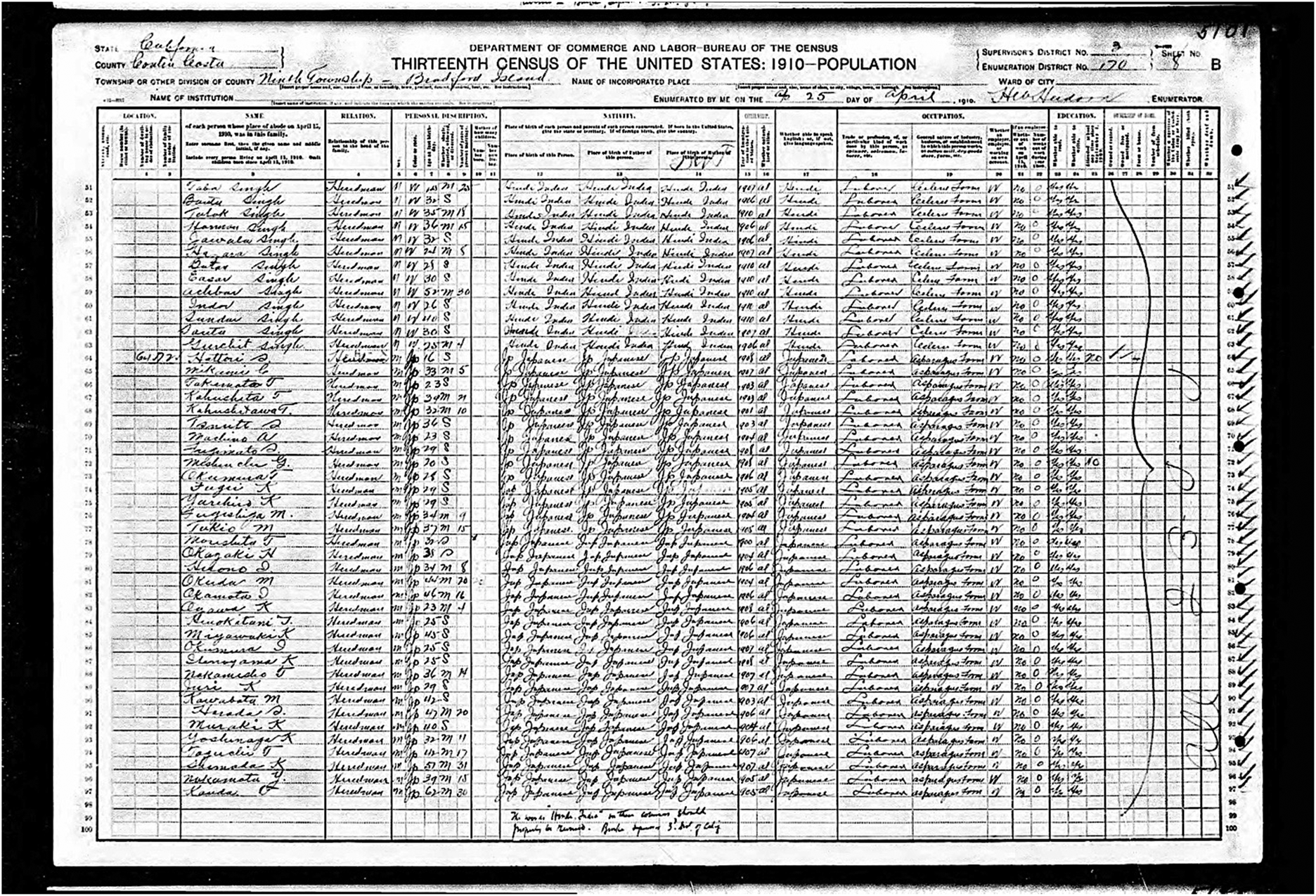

In 1910, the Census Bureau added to the dilemma of Indian immigrants after it classified Indians as “belong[ing] ethnically to the Caucasian or white race,” but not White, because they were not popularly conceived of as White. The Census Bureau concluded, “Hindus, whether pure blood or not, represent a civilization distinctly different from that of Europe,” and insisted that it “was thought proper to classify [Indian immigrants] with non-white Asiatics.”Footnote 53 The decision deviated from the practices of census takers who routinely delineated Indian immigrants as “white,” “Ot” (Oriental), and “H” (Hindu) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Indian immigrants were assigned various racial backgrounds by census takers, including H (Hindu), Ot (oriental), and W (White). In this selection from the 1910 federal census in Bradford, California, Indian immigrants are labeled W (White), while Japanese immigrants are labeled Jp (Japanese).

Source: 1910 U.S. census, Contra Costa County, California, population schedule, enumeration district 170, sheet 8B, digital image,

Ancestry.com, citing National Archives microfilm publication T624, roll 75.

US officials’ targeting of Indian immigrants and other immigrants from more eastern parts of Asia made them a foil for immigrant communities from more western parts of Asia. Some individuals in Syrian, Armenian, Turkish, Jewish, and other communities feared that they would be classified as Asiatic or Mongolian if they were seen as racially proximate to Indians, and would thus encounter greater difficulty naturalizing or lose the right to naturalize as US citizens. Despite their heterogenous demographic, Jewish community members from various parts of the world also feared that they could be distinguished as a distinct race or nation and barred from the United States.

The dilemma of how to determine which immigrants from continental Asia were White enough for US citizenship was captured in a national headline from 1909: “Do we Bar the Asiatic of Aryan Descent Simply because we do not Want the Asiatic of Mongolian Descent?”Footnote 54 Across US courts, Syrian, Armenian, Jewish, and other communities advocated that their geographical proximity to Europe and the Caucasus classified them as White. Starting in 1909, important legal precedents from the prerequisite cases created racial difference among immigrants from continental Asia as White, Asiatic, or Mongolian. In 1909, the Census Bureau's Chief Examiner, R.S. Coleman, insisted that Syrians were not White but of “Asiatic birth.” The agency's decision immediately disenfranchised Syrians from an array of rights. In La Crosse, Wisconsin, 100 Syrian voters were informed that they would lose their citizenship and the right to vote.Footnote 55 In response, the Syrian-American Club of New York City rallied Syrian organizations across the country and deposed a delegation to the nation's capital in hopes of modifying the Bureau's ruling.Footnote 56 In December 1909, Costa George Najour, a Syrian Christian immigrant from Beirut, became the first applicant to successfully litigate his status as a White person in a US federal court. Syrians celebrated the Najour's naturalization in Atlanta's circuit court after his lawyer and a Syrian voluntary association successfully proved that he was not Mongolian, as the attorney general insisted, but from “central, north, or east Asia,” and thus Caucasian and White.Footnote 57 Najour later recounted his victory as helping establish that “Syrians were different from the Yellow race.”Footnote 58 The case held meaningful precedent for subjects of the Ottoman Empire and western Asia, and for Christians from the region who sought to naturalize as Syrian given the slippages around nationality that played out in US courts.

In 1909, Armenian immigrants celebrated the court's decision in the case of Jacob Halladjian, Mkrtich Ekmekjian, Avak Mouradian, and Basar Bayentz. Judge Francis Cabot Lowell insisted that Armenians were not Mongolian and had “always been reckoned as Caucasians and White persons; that the outlook of their civilization has been toward Europe.” The decision countered the attorney general who had challenged the petitions of other Armenian applicants, insisting that they belonged to the Asiatic race.Footnote 59

In some courts, judges struggled to assess whether Parsee Indians were White because of their shared ancestral heritage with immigrants from more western parts of Asia. In 1909, judge Emile Lacombe, on the Second Circuit, granted citizenship to Bhicaji Franyi Balsara, an elite Parsee immigrant in New York who had arrived in the United States as a cotton buyer for the Tata group, noting “he was a gentleman of high character and exceptional intelligence” and of “the purest Aryan type.” Lacombe included that the naturalization of Parsees created legal grounds for “Afghans, Hindus, Arabs, and Berbers” to naturalize as US citizens, intending to provoke the DOJ to challenge his ruling.Footnote 60 The DOJ appealed, contending that Parsees were not White because only immigrants from England, Holland, Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Germany, Sweden, and France were interpreted as White when Section 2169 was passed.

Balsara's case worried Syrian, Jewish, and Armenian immigrant communities that shared ancestral heritage with Balsara and believed that his case would impact their own chances to naturalize as US citizens. The Black press recognized that the central issue at stake for the US government was whether the case “would open the door not only to Parsees but to Afghans, to the Hindus, to the Arabs, even to the Berbers.”Footnote 61 In 1910, Syrian immigrants provided funding and legal support for Balsara, hiring Louis Marshall and Max J. Kohler, who had supported the naturalization petitions of Syrian immigrants and participated in campaigns to protect the rights of Jewish immigrants to naturalize by ensuring that the Census Bureau did not adopt a distinct racial category such as “Hebrew” to classify Jews as not White.Footnote 62 Marshall and Kohler, critics of Asian exclusion and descendants of immigrants from western Europe, became involved in defending Jewish immigrants from eastern Europe, fearing that the restriction of eastern European Jews could affect the more established Jewish community of western European descent. Despite differences in the Jewish community, individuals with ancestral origins across Europe argued that their proximity to Europe and their Semitic origin with European intermixture constituted them as White. Men such as Marshall and Kohler also recognized that their community's fate was connected to that of Parsee and Syrian immigrants on the naturalization issue.Footnote 63 The Circuit Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in New York upheld Balsara's naturalization, insisting that he was Caucasian and therefore White, but it simultaneously declared that “Chinese, Japanese, and Malays, and the American Indians do not belong to the white race.” The ruling reasserted that immigrants with ancestral heritage in west Asia, but not those from more eastern parts of Asia, could be welcomed into the national polity. It also left the eligibility of other Indian immigrants in flux since the court distinguished Parsee as “distinct from the Hindus … who dwell in India.”Footnote 64

Legislative efforts to uniformly bar Indian labor immigrants from the United States placed Indian immigrants at the center of Asiatic difference once again in 1914.Footnote 65 These efforts finally succeeded in February 1917, when the Senate overrode President Woodrow Wilson's veto and passed the most stringent federal immigration law in US history. The 1917 law racialized the geography of Asia and Europe, narrowing the bounds of acceptable Whites by excluding southern and eastern Europeans through a literacy examination and barring entire communities of immigrants from parts of southern, central, and eastern parts of Asia through a “geographic exclusion zone.”Footnote 66 The act built on the precedent of Asian exclusion established in the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, but without referring to race or nationality. Instead, the geographic exclusion zone—called the “Asiatic barred zone”—drew a line of exclusion roughly from Afghanistan to the Pacific, effectively barring all labor immigrants from parts of southern, central, and eastern Asia while carving out exceptions for Japan and the Philippines. Former iterations of the bill expressly named “Hindus” and other Asian immigrants as excluded communities or stipulated that “those not eligible to become naturalized citizens of the United States” should be excluded from the United States. Legislators ultimately opted for geographical coordinates with the hope of curbing any legal and diplomatic challenges stemming from explicit reference to race or nationality.Footnote 67

The 1917 Immigration Act was forged amid the rapid expansion of a transimperial surveillance apparatus that sought to police enemy aliens and foreign threats, as Christopher Capozzola has demonstrated.Footnote 68 US officials reflected these concerns in immigration proceedings, asking Indian immigrants whether they had conspired or would conspire with Germans, and collaborated with British officials to target Indian immigrants in the United States seeking to overthrow the British government with German support.Footnote 69 Throughout the war, British intelligence officials worked alongside US officials to unveil various Indian and German alliances and prosecute conspirators. In 1917, the United States sued Indian activists in the German–Hindu Conspiracy trial. The men, including US citizens such as Taraknath Das, claimed they were fighting for freedom against an oppressive colonial regime. The German–Hindu Conspiracy case fueled the longest and most expensive trial in US history at the time, and sparked concerns about the politics of Indian immigrants in the United States.Footnote 70

The 1917 Immigration Act and the transimperial surveillance apparatus in the United States targeting Indian immigrants for deportation had three significant effects on the naturalization of Asian immigrants. First, its passage spurred a new wave of naturalization petitions from Asian immigrants, particularly Indian laborers and activists who were generally targeted by US bureaucrats and immigration officials for deportation.Footnote 71 Second, the 1917 law gave fodder to district attorneys, attorneys general, judges, and naturalization examiners to argue that the exclusion of Indian laborers from the US justified their exclusion from US citizenship. Third, the law sharpened the presumptions of racial difference between immigrants from more western parts of Asia and immigrants from other parts of Asia. It provided new legal grounds for the former to claim that they were eligible to naturalize as US citizens because they had not been excluded through the Asiatic barred zone.

Racial Capital and the Making of White and not-White Indian Immigrants

The adjudication of race in the case of Indian immigrants reveals how the acquisition of US citizenship was predicated on the racial capital of immigrant men. Indian immigrants in the United States experienced great difficulty naturalizing as US citizens, but the most elite among them secured US citizenship in the early twentieth century. With their discretionary decision-making powers, state officials restricted male Indian laborers and Indian women to permanent alienage while naturalizing elite immigrants as US citizens based on their racial capital. US citizenship and alienage were therefore affected by gender, class, and race. These patterns revealed that the naturalization of Indian immigrants in federal courts mimicked the forms of racial capital carved out in existing federal immigration law in exemptions for Asian students, teachers, merchants, and clergy, to preserve the investments of American capitalists.

Muslim merchants, largely from colonial Bengal (present-day Bangladesh), were among the first Indian immigrants to naturalize in the United States. They naturalized in the US South, where federal courts were partial to legally expanding the conception of Whiteness to Asian persons, to distinguish all races from Black residents during the early Jim Crow period.Footnote 72 Bellal Houssein and Abdul Hamid, both 32-year-old men with strong ties to New Orleans’ Creole community, were among the first Indian immigrants naturalized in the United States on March 20, 1908 in the Eastern District Court of Louisiana in New Orleans.Footnote 73 They naturalized despite ongoing denaturalization proceedings against Chinese and Japanese immigrants in the region.Footnote 74 While their naturalization petitions and other federal records do not provide information about how these immigrants proved that they were White, Indian men denied naturalization in courts across Northern states found success naturalizing in the US South, where they were classified as merchants, traders, and peddlers. Abdul Hamid, for example, re-filed in New Orleans after his case was denied in the Circuit Court for the Southern District of New York.Footnote 75

US courts refused to naturalize Indian laborers and men who wore turbans, and Indian men who refused to remove their head coverings for naturalization proceedings were turned away or thrown out of the courtroom.Footnote 76 County clerks saw Indian men wearing head coverings as “turbaned foreigners” refusing the “manners of America.”Footnote 77 The only men who wore turbans and worked as middling laborers were Indian war veterans, such as Ishar Das Duke, Bishen Singh Mattu, Joe Namo, and Devi Chand, who naturalized under the 1918 Service Act, which allowed “any alien” who served in the armed forces to naturalize as a US citizen.Footnote 78 The law was part of a gendered federal effort to conscript immigrant men and their families into US citizenship based on their allegiance and martial service, despite allegations by the Bureau of Naturalization and its anti-Asian supporters that the Service Act only applied to “aliens” who were eligible to naturalize under existing naturalization law as White.Footnote 79

Modern alienage in the United States preserved the domain of naturalization for men by obfuscating the relevance of race in deciding cases related to the naturalization of women. Indian women were denied US citizenship by federal courts based on coverture, which delineated how immigrant women were doubly alien in the United States: both as alien immigrants and because their legal personhood was defined through coverture.Footnote 80 Indian women who traveled to the United States were deemed to have the nationalities of their husbands or fathers. The handful of Indian women in the United States in the early twentieth century were either married or were the daughters of immigrants, but 19-year-old Kanta Chandra, an orphan, made history when she submitted a petition to naturalize in 1916. Chandra claimed that she was White. Warned by the deputy clerk that she would lose her status as a US citizen if she married (presumably an Indian) after naturalization, Chandra stated that she had plans to obtain a medical degree instead. Still, the court denied Chandra's application for naturalization.Footnote 81

Amid racialized opposition from leading federal bureaucracies, including the Departments of Labor and Justice, more than seventy well-to-do Indian immigrants were able to secure naturalization between 1908 and 1923 after proving that they were White.Footnote 82 These men stood in contrast to the hundreds of Indian labor immigrants whom state officials refused to naturalize and comprised most of the Indian population in the United States. Relatively well-to-do Indian men—merchants, students, clergy, and white-collar employees—had secondary education, professional employment, English fluency, associational ties to White and Christian communities (including through marriage), and high-caste status, and did not wear religious articles of faith. Individuals who were interested in anticolonial movements refrained from discussing their political views or reframed them in the language of freedom to secure naturalization. Often represented by attorneys in US courts, they distinguished themselves as White and distinct from Indian laborers. County clerks, court clerks, naturalization examiners, and judges recognized and validated these distinctions by naturalizing well-to-do Indian immigrants and denying naturalization to Indian laborers.

Moving among courts in San Francisco, New Orleans, Galveston, Detroit, Portland, OR, Boxelder County, UT, Pittsburgh, and Los Angeles, well-to-do Indian men successfully naturalized as US citizens, often with the assistance of attorneys and White peers. Among them were Jaswant Rai Gandhi and Karm Chandra Kerwell, both graduates of the University of Michigan; Dyiatri Singh, a DePauw University alumnus; and Prafulla Chandra Mukerjee, a chemist at Pennsylvania's Homestead Steel Works.Footnote 83 Many enjoyed close ties to Christian organizations and churches, and some, like Randjit Singh who taught at Christian Bible School in Minneapolis, were clergymen. US courts on the Pacific and Atlantic seaboards also naturalized an array of Indian merchants, including business owners Vaishno Das Bagai and Diwan Singh Mainee, and Sheriarji Maneck, a Parsi merchant who ran an international firm headquartered in Surat.

The adjudication of race in the case of Indian immigration substantiated the nation's concern with racial purity, but translated it into a transimperial context that relied heavily on evidence related to caste and blood purity. As theories of race purity gained prominence in state law across the United States, legal requirements such as the one-drop rule and blood quantum became mechanisms of dispossession to retain interracial persons as slaves (prior to abolition), police interracial intimacies, and to deprive Indigenous communities of their lands.Footnote 84 Legal requirements related to racial purity therefore sharpened the boundaries of Whiteness. They also placed a heavier legal burden on immigrants communities not immediately deemed White to prove both Whiteness and the purity of their Whiteness.

Caste became central to defining race and racial purity for Indian immigrants in US courts.Footnote 85 The legal precedent set by Bengal-born Akhay Kumar Mozumdar in 1913 marked an Indian immigrant as White if he was “a high-caste Hindu of pure blood.”Footnote 86 Mozumdar testified that he was a “high caste Hindu of pure blood” and a member of the Aryan race to combat the naturalization examiner's declaration that he was Asiatic and not White.Footnote 87 The District Court of the Eastern District of Washington ruled in Mozumdar's favor, and even the Asiatic Exclusion League emphasized the importance of “high-caste” status to naturalization following the court's ruling.Footnote 88 Mozumdar's case caught the attention of the Black press, and the Chicago Defender predicted that it boded well for all Indian and Japanese immigrants who sought to naturalize in the United States.Footnote 89

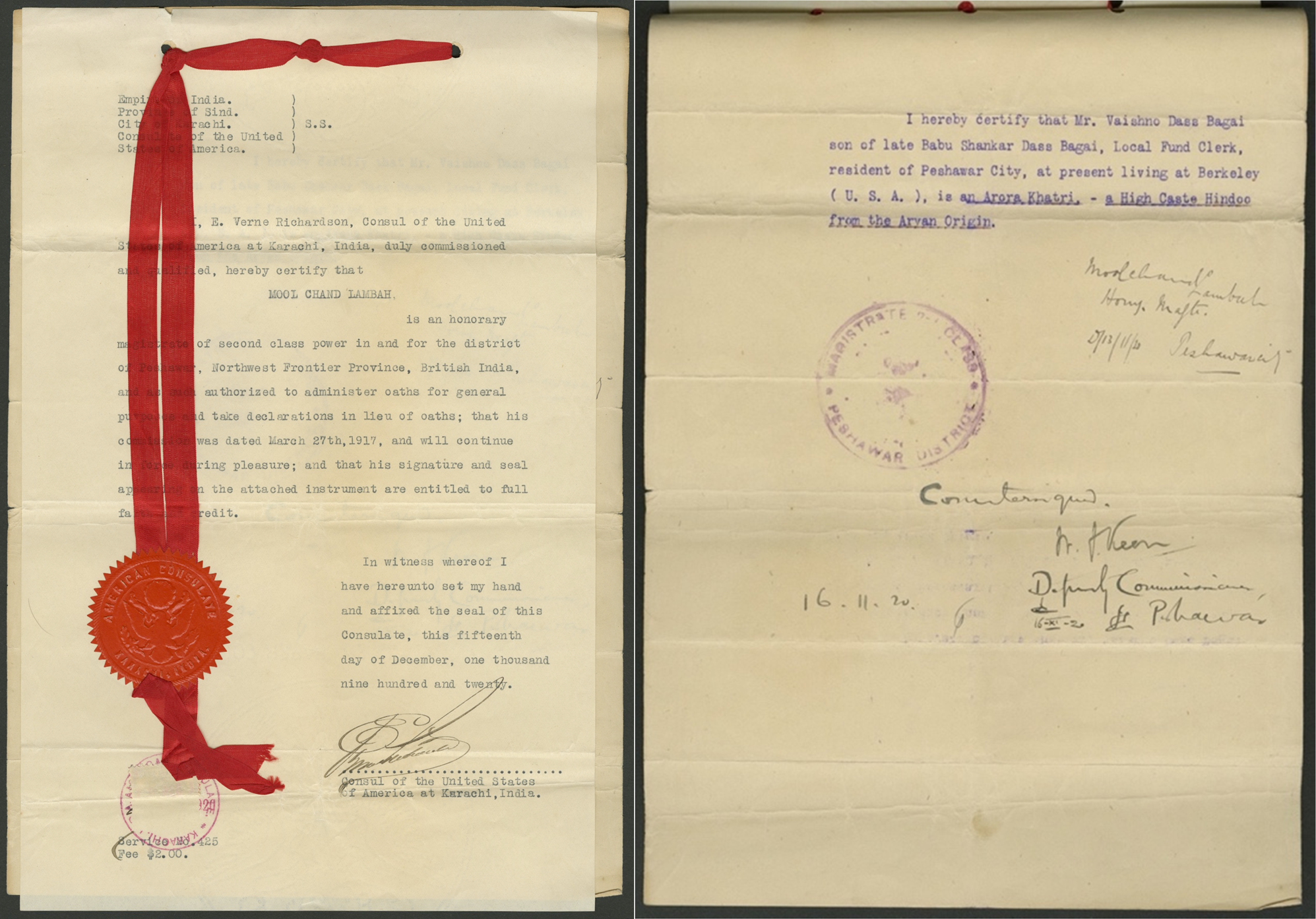

Other Indian immigrants, such as Saranghadar Das, a Stanford graduate and chemist, and Sakharam Ganesh Pandit, an aspiring law student, argued that they were “high caste Hindu[s] of pure blood” to successfully naturalize as US citizens.Footnote 90 Members of the anticolonial diasporic Ghadar movement, who advocated against the racist governance of the British Empire, including Godha Ram and Bhagat Singh Thind, also claimed high-caste status to distinguish themselves as White.Footnote 91 They cited ethnology and race surveys, which classified Indians as Caucasian and Aryan and therefore White, and claimed that Brahmin communities were endogamous to establish racial purity. Some Indian men relied on a transimperial knowledge exchange to support their naturalization petitions in US courts. Vaishno Das Bagai, an Indian merchant and anticolonial activist, wrote to the local magistrate in his home district of Peshawar and obtained three caste certificates through the US consul certifying that he was a “high caste Hindoo from the Aryan origin.”Footnote 92 The certificates, like birth certificates and other vital registration documents, represented how bureaucratic forms of knowledge could supplement and even replace local knowledge about race (Figure 2).Footnote 93 They also highlighted that Indian immigrants like Bagai had a deep understanding of Indian bureaucracy and local connections to acquire documents while overseas.

Figure 2. Caste Certification for Vaishno Das Bagai, issued by Mool Chand Lambah, December 15, 1920.

Source. Vaishno Das and Kala Bagai Family Materials, South Asian American Digital Archive. Courtesy of Rani Bagai.

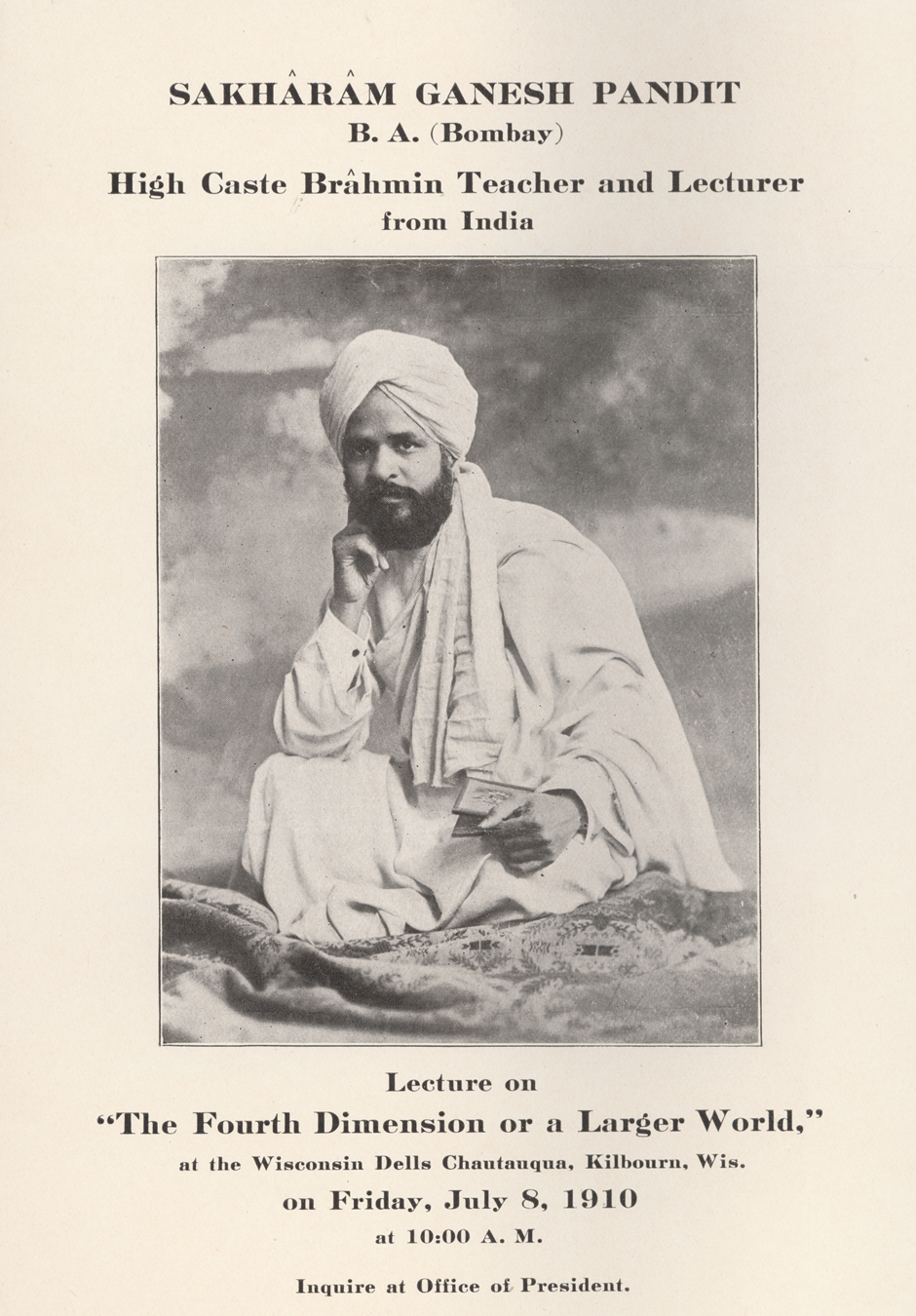

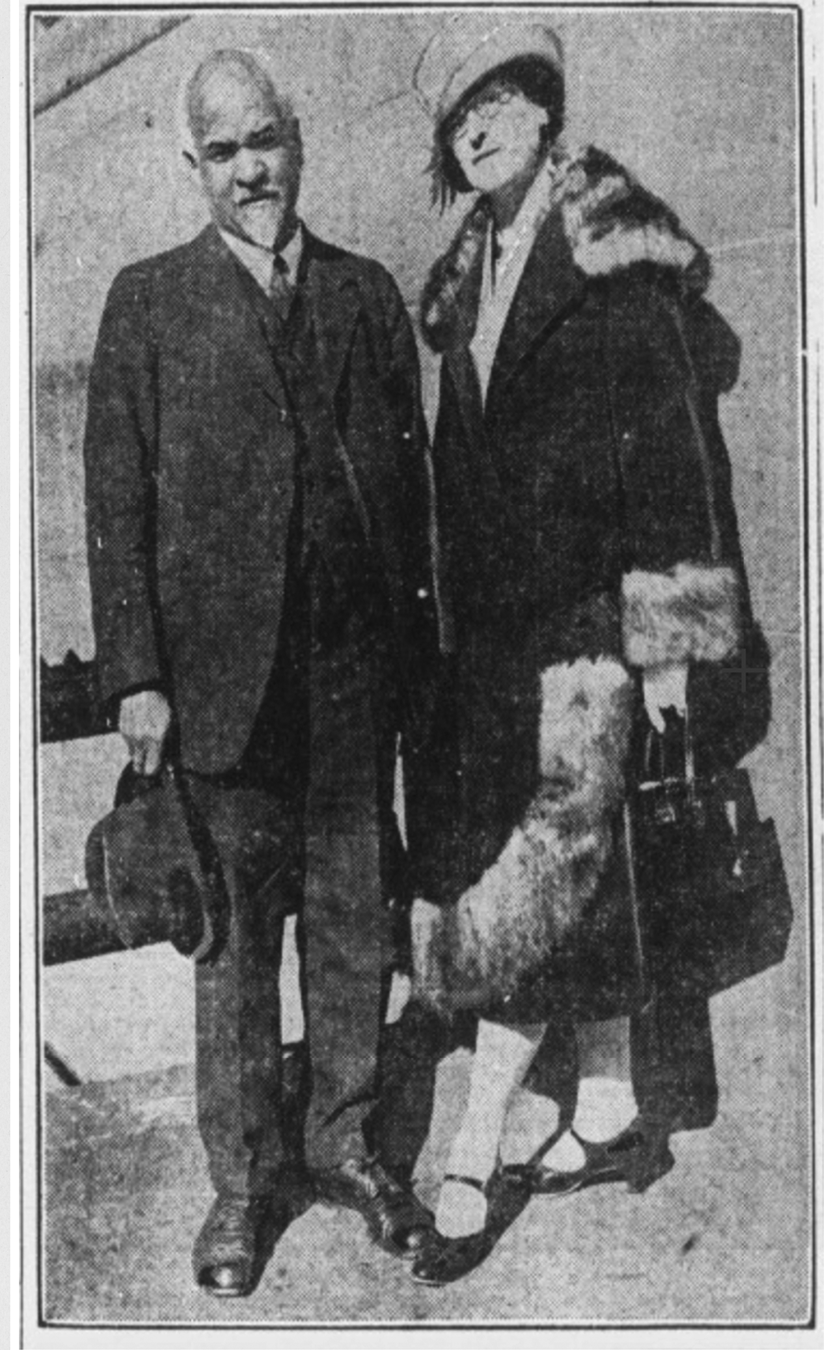

Some immigrants, like Pandit, shed turbans, beards, and non-Western clothing to naturalize as White, underlining how race was predicated on physical appearance and decorum as much as on caste, blood, and ancestry. Embracing Western dress, hairstyles, and English in US courts fostered a sense of visual Whiteness and upper-class decorum that was required of those proximate to Whiteness to naturalize as US citizens (Figures 3 and 4). But entry to US citizenship did not guarantee that all US officials registered men like Pandit as White. Despite his best efforts to appear White, Pandit continued to be classified as non-White. In 1918, a World War I draft registration card recorded Pandit as Oriental.Footnote 94

Figure 3. Photogram of Pandit from a pamphlet advertising the lectures of Sakharam Pandit, described as “High Caste Brahmin Teacher and Lecturer from India.”

Source. Redpath Chautauqua Collection, Special Collections & Archives, University of Iowa Libraries.

Figure 4. Photograph of Pandit and his wife, Lillian Stringer, printed in a Californian newspaper after he successfully contested his denaturalization.

Source. “‘Man Without Country’ Wins Rights,” Illustrated Daily News, December 17, 1925, 1.

The National Struggle for Racial Capital and the Making of US Citizens and Aliens

In the early twentieth century, the line separating the rights and privileges accorded to US citizens and those accorded to aliens thickened. State legislatures employed legal status as an avenue to disenfranchise aliens from the right to vote, marry across interracial lines, secure public sector employment, and maintain membership in white-collar professions such as law and medicine. States expanded citizen-only laws with the intent of keeping aliens from an array of resources and socioeconomic mobility. These laws coded race through the language of legal status to avoid explicit racial discrimination and normalized the notion that citizens and aliens were legal subjects with distinct rights and privileges. In effect, legal status such as citizenship became critical for White citizens to acquire wealth. It also limited non-White immigrants from acquiring wealth, which further animated legal debates on whether Indian immigrants constituted white persons or not. While non-White immigrants could not naturalize, European immigrants could naturalize because they were classified as White, reinforcing their own racial capital and socioeconomic mobility.

Tensions over Asian immigration and access to citizenship boiled over in response to property ownership, especially of agricultural land. Across the United States, White citizens feared the purchase of land by first-generation Japanese immigrants whose purchasing power surpassed that of other Asian immigrants. In California, landed Whites fretted over growing Issei economic strength and the racial threat to the status quo in the agricultural industry, which regarded Asian immigrants as laborers, not landowners.Footnote 95 Indian immigrants were a secondary but important concern in the struggle over land ownership. White citizens, fearing increasing land ownership among Asian immigrants, passed the first alien land law in California in 1913. California's alien land law built on the state's constitutional and state provisions restricting “aliens ineligible to citizenship” from owning and leasing land.Footnote 96 This racially coded clause became the model for alien land laws in Arizona (1917); Washington, Texas, and Louisiana (1921); New Mexico (1922); Idaho, Montana, and Oregon (1923); and Kansas (1925).

Alien land laws not only circumscribed the opportunities of alien immigrants but also called into question the eligibility of Asian immigrants to naturalize. White nativists policed land purchases by Japanese and Indian immigrants alongside their naturalization petitions. They conveyed news to local papers, which reported on acreage and location. Reports in the White press, together with land registration files, drew the attention of local district attorneys and attorney generals who targeted Japanese and Indian immigrants who leased or purchased agricultural land. Naturalization cases in counties where Indian immigrants purchased the most land received the most publicity, including Imperial, Fresno, Los Angeles, Sutter, and Sacramento counties.Footnote 97 The loss of land rights for Indian immigrants was so significant that major newspapers in colonial Punjab, the birthplace of most Indian immigrants in the United States, criticized California's alien land laws. One paper even insisted that the Japanese government would send “a delegation to California to straighten the United States out.”Footnote 98

The alien land laws, when enforced, sought to recast Japanese and Indian immigrants as immigrant labor by reducing them to share tenancy that mimicked sharecropping leases in the US South. They also made Asian immigrants dependent on propertied Whites to circumvent alien land laws and avoid the brunt of their enforcement.Footnote 99 The disenfranchisement of Japanese immigrants spurred Syrian immigrants to file first and second papers for naturalization and wage stronger campaigns to secure US citizenship on the basis that they were not Asiatics.Footnote 100 Many Japanese and Indian immigrants left their state or adapted to alien land laws by teasing out a series of legal techniques that undermined the strictures of existing alien land laws. For example, Indian and Japanese immigrants assigned property ownership to their wives when they were US citizens, and to birthright children.Footnote 101

The Supreme Court and the Construction of Aliens Ineligible for Citizenship

Struggles over land and resources, and over who constituted a White person by law, led the Supreme Court to deliberate the eligibility of Asian immigrants for citizenship. The legal dispute over Japanese rights to naturalization made its way to the Supreme Court in 1922, when Takao Ozawa, a Japanese immigrant resident in Hawai'i and former Berkeley student, insisted on securing naturalization despite others in the Japanese immigrant community believing that the moment was inopportune to present a test case to the US Supreme Court. The United States had just refused to accept the racial equality clause affirming the equality of all nations, submitted by Japan to the League of Nations, signaling that it would not grant legal equality to Japanese immigrants in the United States.Footnote 102 The Bureau of Naturalization avoided challenging the naturalization cases of more well-to-do Japanese immigrants and others in military service. It settled on making Ozawa's case a test case believing it would be easier to contest across federal courts.Footnote 103 Japanese American organizations, such as the Japanese Association Deliberation Council and the Japanese Association of America, reluctantly agreed to assist with legal support after realizing that Ozawa's would be the test case on Japanese immigrants’ eligibility for citizenship. The Pacific Coast Japanese Association Deliberation Council hired George W. Wickersham as Ozawa's chief counsel. The decision underlined the community's legal consciousness. Wickersham had previously served as US attorney general under former US President William Howard Taft, who was then Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Ozawa's legal team argued that he classified as White based on his skin color and American-ness, while James M. Beck, Solicitor General of the United States, argued that only immigrants understood as White “in their ordinary sense,” not the “technical sense,” were White.

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court George Sutherland penned the court's unanimous decision. The court's ruling declared Ozawa part of the “brown or yellow races of Asia,” which were purposefully excluded from the nation's early federal naturalization laws. The court concluded its ruling noting that since Ah Yup (1878), there was an “almost unbroken line” that held that White persons were understood as “what is popularly known as the Caucasian race.”Footnote 104 The ruling rendered Japanese immigrants in the United States ineligible for citizenship on the basis of race, but provided some hope for Indian immigrants, because the court cited two cases related to Indian immigrants’ eligibility for US citizenship in support of its decision.Footnote 105

As Ozawa's case made its way through the courts, Vernor W. Tomlinson, a naturalization examiner in the Portland Bureau who was an avid supporter of Americanization campaigns, brought Campbell's 1908 vision to fruition by contesting the naturalization petitions of Indian immigrants. Tomlinson targeted Bhagat Singh Thind, a former student of Khalsa College, interpreter, University of California at Berkeley student, and Ghadar activist, as he sought to naturalize in 1918. During Thind's third attempt to naturalize in Oregon after he failed in Washington state, Tomlinson colluded with British officials, insisting that Thind should be restricted from citizenship on the basis he had violated US neutrality laws during the war by participating in the Ghadar movement.Footnote 106 The Pacific Northwest was a hotbed of Asian activism, as Kornel Chang has described, so Tomlinson was likely familiar with Indian activists such as Thind.Footnote 107 The attorney general appealed the case, but Thind appealed to the US District Court for the District of Oregon, where Judge Charles Wolverton naturalized Thind after noting “a line of cases” illustrated that Indian immigrants were White, and that Thind “now professe[d] a genuine affection for the Constitution, laws, customs, and privileges of this country.”Footnote 108 The DOJ appealed to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, and the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case in 1923.

Thind was an anomaly among other Indian immigrants who were naturalized as US citizens. Unlike many Indian citizens, Thind was of middling socioeconomic status. He spoke English but lacked graduate degrees from acclaimed universities and was not as active in White networks. He also wore a turban, which served as a physical marker of distinction beyond the color of his skin. For the DOJ, Thind most likely represented the perfect test case to try the boundaries of Whiteness. The US Supreme Court heard the case of Bhagat Singh Thind three months after Ozawa. The question before the court was “Is a high caste Hindu of full Indian blood, born at Amrit Sar, Punjab, India, a white person?”Footnote 109 William R. King, a former justice on the Oregon Supreme Court, and Thomas Mannix, Thind's original attorney, argued the case on Thind's behalf. The lawyers cited American and European race thinkers such as Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, Thomas Henry Huxley, and Max Mueller; the Encyclopedia Britannica; Daniel Folkmar's Dictionary of Races and People; and many cases that the Supreme Court had cited in Ozawa to delineate that Thind was Caucasian in accordance with existing race science, and therefore white.Footnote 110 Thind also attached an appendix to King's brief, claiming he was a “free white person” and had pure Aryan blood, since ancient texts from India, in particular the Laws of Manu, prohibited inter-caste marriage.Footnote 111 Like many Indian immigrants who had sought citizenship before him, Thind emphasized the relationship among caste, blood, and race in his claims to racial purity and Whiteness. In Thind's case, the DOJ alleged that Indian immigrants were not White under the original intent of Section 2169, and did not have the right to naturalization, since they were barred from the United States under the Immigration Act of 1917.Footnote 112

The US Supreme Court unanimously denied Thind citizenship on nearly every legal basis that emerged in the prerequisite cases: the original intent of Section 2169, racial purity, race science, ancestry, “popular” understandings of race, federal immigration law, and visual assimilability. Sutherland penned the court's unanimous ruling, noting that the various texts cited in Thind's defense were “in irreconcilable disagreement as to what constitutes a proper racial division,” before alleging that Indian immigrants were of “Asiatic stock” and could not establish racial purity based on caste because “intermixture” was still possible, “even in the case of the Brahman caste.”

Federal immigration and naturalization law were both integral to the court's ruling on Indian immigrants’ ineligibility for US citizenship. Citing the 1917 federal bar on Indian immigration to the United States, the court declared “it is not likely that Congress would be willing to accept as citizens a class of persons whom it rejects as immigrants.” The court's multiple rationales indicated that it sought to reach a definitive resolution on the eligibility of Indian immigrants to naturalize. The court's ruling also noted that Section 2169 was designed for immigrants from Europe, including “swarthy people of Alpine and Mediterranean stock,” and that revisions to the law in 1870 were designed to “exclude Asiatics generally from citizenship.” It dismissed Thind's references to popular and common usages of race that delineated Indians as White, asserting that the terms “white” and “Caucasian” should be interpreted through “popular meaning,” because it would be “illogical to convert the words of common speech … to scientific terminology.” The court added that this sense of the word “white” did “not include the body of people to whom the appellee belongs.”Footnote 113

The court also insisted that even if Indians and Europeans shared a common Aryan ancestry, their origins had been “sufficiently differentiated” over time, making Indian immigrants “distinguishable from the various groups of persons in this country recognized as white.” Thind symbolized the force of the Supreme Court's rationale. He did not pass as White, as many other non-White immigrants had before him. He was not as light-skinned as his peers or Ozawa, and he wore a turban and long beard. The Negro World, in its assessment of the case, noted, “This ruling [was] merely another step in the national program to make the United States a ‘white man's country.’”Footnote 114

News of the Thind case and denaturalization attempts spread across the United States and India. Sudhindra Bose, a naturalized US citizen, decried the Supreme Court's decision as the “most recent slap at India,” which “enthrone[d] racial superiority and human inequality.” Bose called on the Viceroy of India to remedy the humiliation of Indians in the United States.Footnote 115 He was likely unsurprised when the government of India remained silent on the issue. Taraknath Das contended that US naturalization laws were directed against “all Asiatic peoples,” particularly the Chinese, Japanese, and Indians; these groups, he said, were “equally discriminated against within the British Empire and United States.” “According to the present laws of the United States, a man of the position of the late Dr. Sun Yat Sen of China, men of such eminence as Dr. Nutobe or Dr. Anazaki of Japan and savants and scholars like Rabindranath Tagore, Gandhi, and Jagadis Chunder Bose or P.C. Ray cannot become citizens of this country” or own land, Das wrote. He urged the Chinese, Japanese, and Indian governments to construct a common policy so that people of other nations would not discriminate against them. Das also noted that naturalization laws protected Armenians, Persians, Syrian Christians, and Palestinian Jews, alongside all White persons and persons of African birth and nativity.Footnote 116

The Lawful Recasting of Aliens as Immigrant Labor

The San Bernadino Sun captured the aim of modern alienage in the headline “Asiatics Must Work on Wage or Not at All.”Footnote 117 The Supreme Court's rulings in Ozawa and Thind concretized the construction of Indian and Japanese immigrants as Asiatics and as permanent aliens whose legal rights, access to capital, and mobility—particularly to and from the United States—were vastly restricted because of their legal status. Local White residents and federal officials relied on the intersection of federal naturalization law and state alien land laws in recasting Indian and Japanese immigrants as immigrant labor. They targeted Indian and Japanese immigrants who owned or leased land in various of the United States, forcing them to sell, find legal loopholes, or move.

On the very day that the Supreme Court delivered a ruling in Ozawa, it also cited the case as precedent to uphold the ineligibility of Japanese immigrants to own or lease land under Washington State's existing alien land law, because they were ineligible to naturalize as US citizens. The case involved an affluent Japanese immigrant, Takuji Yamashita, whom Wickersham represented and believed would provide a strong test case in the event that Ozawa's was thrown out on a technicality.Footnote 118 The following year, the court upheld that alien land laws did not violate the Due Process or Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment, which underlined how legal status became an acceptable form of racial discrimination through property law.Footnote 119 The two rulings highlighted how legal status could be employed as a form of racial discrimination and segregation to retain land and property, including homes, for White Americans. The impact on the Japanese community was devastating, as Michael R. Jin has shown, leading to the loss of land, suicide, and the departure of many Japanese immigrants, including US citizens, from the United States.Footnote 120

Just four days after the Supreme Court delivered its ruling in Thind, the Chico Record asserted that the ruling “place[d] Hindu residents of this state, many of whom have large lease-holdings of agricultural lands … under the provisions of the alien land law.”Footnote 121 In some regions, such as California's Imperial Valley, Indian immigrants left their landholdings as attorney generals targeted them. Local councils met to formulate plans for White farmers to take over vacated lands and capitalize on cotton fields left behind.Footnote 122 British officials expressed concern over the “undue hardship” caused by the enforcement of the alien land laws, but their diplomatic response rang hollow. Rather than contesting the alien land laws, they merely asked US officials to allow Indians immigrants more time to sell their property.Footnote 123 But Indian immigrants continued to contest the alien land laws using their own resources in local courts.Footnote 124 In colonial India, Indian legislators and activists supported reciprocity bills that denied US citizens the right to purchase land and gain admission to colonial India.Footnote 125 They did so just as the British ambassador Bryce and British consuls rescinded Indian immigrants’ rights to reciprocity in the United States.Footnote 126

Congress employed federal immigration law to police the boundaries of Whiteness established through the racial prerequisite cases. In 1924, Congress passed the Johnson-Reed Act and created the United States's modern regime of immigration quotas based on national origin that ranked Europeans in a hierarchy of desirability but recast persons of European descent within the United States as sharing a common Whiteness. The law also barred “aliens ineligible to citizenship,” with the sole purpose of restricting immigrants from Japan.Footnote 127 The new federal immigration law drew criticism from a range of Asian immigrants and their home governments. Two days after the passage of the Johnson-Reed Act, the Labor Appropriation Act established the US Border Patrol as a new policing power. The growth of new bureaucracies in the United States was integral to policing the boundaries of Whiteness on and within the United States' land and sea borders, as well as Central and South American immigrants, given their exemption from any quotas established through the Johnson-Reed Act.Footnote 128 In the words of Indian immigrant Sudhindra Bose, the law was an attempt to render “America completely white, chemically white.”Footnote 129

After 1923, Indian, Chinese, Japanese, and Korean immigrants who had not naturalized resided inside US borders as permanent aliens.Footnote 130 The passage of the 1924 laws, which restricted entry, including re-entry, to the United States, encouraged European immigrants who had previously resisted naturalization, or remained indifferent to it, to naturalize.Footnote 131 European communities with lower naturalization rates, including Italians, were increasingly targeted by immigration restrictions in the wake of World War I, as Maddalena Marinari has argued.Footnote 132 Amid new state and federal naturalization and immigration regulations, many European immigrants discerned the value of US citizenship.

The Use of Ozawa and Thind as Precedent for Disenfranchisement

The legal boundaries of White and Asiatic acquired sharper definitions in the wake of Thind and Ozawa, as naturalization examiners contested the eligibility of Asian immigrants for US citizenship and continued to shape Asian immigrants’ synonymity with US alienage. V.W. Tomlinson, the examiner who pursued Thind across district courts in Oregon, followed directives issued by the Bureau of Naturalization, and subsequently targeted Armenians, Syrians, and “other immigrants from the Near East.”Footnote 133 The Commissioner of Naturalization, Raymond F. Christ, supported additional test cases to determine the “admissibility to citizenship of members of other Asiatic races, such as Afghans, Syrians, Armenians, Turks, Kurds, Arabs, and Bedouins.”Footnote 134 In 1924, Tomlinson returned to the District Court of Oregon and contested Judge Robert S. Bean's decision to naturalize Tatos Cartozian, an affluent Armenian Christian rug merchant, and his family, placing Armenian immigrants at the center of a new legal battle over Asian immigrants’ eligibility for naturalization.

Naturalization examiners regularly stifled naturalization attempts by immigrants from continental Asia, but the Bureau of Naturalization opted to limit its appeals until the US Supreme Court decided on Cartozian's case. The District Court of Oregon delivered a ruling on the matter in 1925. The court insisted that Thind did not determine the racial eligibility of the entire “Asiatic stock” for naturalization, and that Armenians, although from Asia, were proven by ethnological studies to be “of the Alpine stock, of European persuasion” and “amalgamated readily with the White races,” according to the term's common use and Section 2169.Footnote 135 The ruling held after the DOJ failed to appeal the matter to the US Supreme Court in subsequent years.

Yet the Bureau of Naturalization and DOJ successfully contested the naturalization cases of immigrants from parts of Asia adjacent to colonial India and farther east, hardening the racialization of continental Asia by carving out central Asia, as well as parts of eastern, southern, and central Asia as a geographical demarcation of racial difference. Federal officials targeted Afghan immigrants because their early naturalization was contingent on Indian immigrants’ eligibility to naturalize. For example, attorneys for Abba Dolla, an Indian immigrant of Afghan descent who had traveled to the United States with Abdul Hamid, cited Hamid's case as precedent to successfully naturalize in Savannah, Georgia in 1910.Footnote 136 Afghan immigrants’ eligibility for citizenship, contested across the United States, culminated in Feroz Din's 1928 case.Footnote 137 Hearing the case, the Northern District Court for California insisted that Din “was readily distinguishable from ‘white’ persons and approximate to Hindus,” and cited Thind as precedent to restrict Afghans from the right to US citizenship.Footnote 138 While Filipinos were restricted from naturalizing as US citizens as US nationals, those who naturalized in the United States were targeted by the DOJ like other Asian immigrants following Thind and Ozawa. This group included Filipino men like Ambrosio Javier.Footnote 139 It is likely, as in the case of Chinese immigrants, that a small number of other Asian immigrants restricted from naturalization based on race or imperial policy continued to naturalize as US citizens, but this history has yet to be recovered.

US bureaucrats, nativists, and legislators also employed Ozawa and Thind as case precedent to restrict the naturalization of Mexican immigrants. The California Joint Immigration Committee worked alongside national organizations, such as the American Eugenics Society, alleging that Mexican men, women, and children were ineligible to naturalize as US citizens. Nativist groups argued that the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo conferred US citizenship on Mexicans in new US territories, but did not delineate Mexicans as White. Nativists raised legal challenges and questions about the eligibility of Mexican immigrants for US naturalization using the cases of Ozawa and Thind as precedent. These efforts proved unsuccessful, but still created havoc for Mexican immigrants, as Natalia Molina has described.Footnote 140

From Legal to Illegal Citizens

The arc of denaturalization was long by the early twentieth century, and Thind became a nodal point in this history.Footnote 141 Thind, as Kritika Agarwal has argued, was not a naturalization case, but a denaturalization case.Footnote 142 It stripped Thind of US citizenship and enabled the Bureau of Naturalization and DOJ to initiate the nation's first denaturalization campaign against an entire community of immigrants on the grounds that Indian men had “illegally procured” citizenship. Some within the Bureau of Naturalization feared that denaturalization would spur diplomatic and racial tensions, but the bureau moved forward with supporting the denaturalization of all Indian immigrants.Footnote 143 Following Thind, the Department of Naturalization released the records of sixty-nine Indian men who had naturalized as US citizens to attorney generals who then filed equity cases, claiming that the men “illegally procured” US citizenship.Footnote 144 The charge of illegality was distinguished from fraud but did not specify what Indian immigrants had done to violate the law. Unlike many other immigrant communities, Indian immigrants did not have diplomatic support and proved an easier target for the DOJ. Assistant US attorneys deployed US marshals and naturalization examiners to deliver subpoenas and decrees of court to denaturalize Indian immigrants. State officials issued notices in local papers when they learned that immigrants had moved. The fates of wives, mostly White and Mexican, and the children of Indian men who were not birthright citizens, were equally impacted because of coverture laws.Footnote 145