Over the past several decades, research has considered the sources of punitive attitudes toward offenders, in general, (e.g., Reference Tyler and BoeckmannTyler and Boeckmann, 1997; Reference Unnever and CullenUnnever and Cullen, 2010) and toward categories of offenders in particular (Reference Pickett and ChiricosPickett and Chiricos 2012; Reference PickettPickett et al. 2013). This avenue of research is important because popular attitudes impact criminal justice policymaking and practice (Reference EnnsEnns 2016). However, theory and research suggest that punitive attitudes are more complex: people may have distinct punitive attitudes related to victims as well as to offenders. The current study broadens the analysis of punitiveness to include “victim-centered punitiveness,” referring to punitive responses toward actions affecting different types of victims. Victim-centered punitiveness can be distinguished from the more commonly analyzed “offender-centered punitiveness,” which encompasses punitive responses toward offenders.

To develop a framework for understanding victim-centered punitiveness, I draw on recent Moral Foundations Theory (MFT) (Reference HaidtHaidt 2007, Reference Haidt2012; Reference Haidt and JosephHaidt and Joseph 2004). According to MFT, judgments about morality reflect multiple domains of moral concern (“moral foundations”), which can elicit strong, intuitive reactions to transgressions against three different entities: individuals, groups, and the “divine,” referring to bodily purity or integrity (Reference HaidtHaidt 2012). Three types of victim-centered punitiveness are thus suggested by MFT: punitiveness toward crimes against individuals, punitiveness toward crimes against collectives, and punitiveness toward crimes against the “divine.”

Using data from a national online survey (N = 915), I develop measures for victim-centered punitiveness and provide the first empirical examination of offender- versus victim-centered punitiveness. I pay particular attention to exploring whether, as MFT would suggest, the moral foundations that correspond to concerns about individuals, collectives, and the “divine” are associated with each dimension of victim-centered punitiveness.

Explaining Public Punitiveness

Public attitudes about offenders have been of interest to researchers for decades. Indeed, public attitudes support a variety of punishment goals, including retribution, rehabilitation, deterrence, and incapacitation (Reference Cullen, Fischer and ApplegateCullen, Fischer, and Applegate 2000). Research has focused on three theoretical perspectives to explain variation in the extent to which people support punitive policies (e.g., Brown and Socia 2016; Reference Unnever and CullenUnnever and Cullen 2010).

First, punitiveness may be an expression of racial animus. Because crime in the United States has historically been typified as being committed by racial minorities (particularly Black men), punitive policy preferences may reflect a response to perceived threat from racial minorities, an apparatus for control, or a way to “vent” anti-Black sentiments (Reference SossSoss et al. 2003). Indeed, racial resentment is one of the most consistent predictors of punitiveness (e.g., Reference Barkan and CohnBarkan and Cohn 1994; Reference SossSoss et al. 2003; Reference Unnever and CullenUnnever and Cullen 2010).

Another explanation is that people may support punitive policies because they are concerned about crime, particularly if they do not believe that the courts are effective in dealing with offenders (Reference SimonSimon 2007; Reference Unnever and CullenUnnever and Cullen 2010). Related explanations include other “instrumental” concerns, such as crime levels, fear of crime, and perceived risk of victimization (e.g., Reference Kleck and JacksonKleck and Jackson 2016). Research, however, has provided only mixed support for this perspective (Reference Kleck and JacksonKleck and Jackson 2016).

A third explanation is that punitive attitudes are “expressive.” Rooted in classical sociological theory (Reference DurkheimDurkheim 1964 [1933]), this perspective posits that people are punitive because they view crime as threatening to shared social values. Punishment serves to express disapproval of behavior that offends public sensibilities and to demarcate the boundaries of morally acceptable behavior (Reference EriksonErikson 1962; Reference Tyler and BoeckmannTyler and Boeckmann 1997). Indeed, concerns about social decline tend to strongly predict punitive attitudes (Brown and Socia 2016; Reference Tyler and BoeckmannTyler and Boeckmann 1997; Reference Unnever and CullenUnnever and Cullen 2010). Authoritarian and conservative worldviews (which encourage the maintenance of social boundaries) are also linked to greater punitiveness (Reference UnneverUnnever et al. 2007). Thus, research supports the perspective that punitive attitudes are “expressive.”

The Moral Psychology of Punitiveness

Although the idea that concerns about morality may influence public punitiveness is not new (Reference DurkheimDurkheim 1964 [1933]), research has only recently begun to explore how individuals’ moral orientations may shape their punitive beliefs. In general, moral psychology aims to explain how people make judgments about right and wrong. Research suggests that, like many psychological processes (Reference KahnemanKahneman 2011), moral judgments are formed through a dual-process system in which intuitions—which are “fast, automatic, effortless, associative, implicit (not available to introspection), and often emotionally charged” (Reference KahnemanKahneman 2003: 698)—precede and inform conscious thought (Reference GreeneGreene 2013; Reference HaidtHaidt 2001, Reference Haidt2012; Reference Haidt and HerschHaidt and Hersch 2001). Once a moral intuition has been formed, conscious, explicit moral reasoning may be used to justify or, less frequently, to override the intuitive judgment (Reference GreeneGreene 2013; Reference HaidtHaidt 2001). Thus, intuitions are powerful determinants of people's consciously held views (Reference HaidtHaidt 2001, Reference Haidt2012). Research using various methods supports the notion that moral judgments are made via a dual-process system (e.g., Reference CushmanCushman et al. 2006; Reference GreeneGreene 2013; Reference Haidt and HerschHaidt and Hersch 2001; Reference HaidtHaidt et al. 1993).

Understanding moral intuitions is important because punitive sentiments are, at least in part, a product of moral intuitions (Reference DarleyDarley 2009; Reference RobinsonRobinson 2013; Reference RobinsonRobinson et al. 2007). Likely developed through evolution to promote cooperation within groups (Reference GreeneGreene 2013), the desire to punish moral violators typically occurs in response to perceived moral violations (Reference Aharoni and FridlundAharoni and Fridlund 2012); such desire appears to operate independently of utilitarian concerns about offender dangerousness or the potential for deterrence (Reference CarlsmithCarlsmith et al. 2002; Reference DarleyDarley et al. 2000). Considering such evidence, some researchers suggest that the desire to punish derives directly from moral intuitions—what they term “shared intuitions of justice” (Reference RobinsonRobinson et al. 2007).

To the extent that diverse moral concerns underlie punitive attitudes, we might expect punitive attitudes to be diverse as well. Moral judgments can be “person-centered” or “act-based” (Reference UhlmannUhlmann et al. 2015). Person-centered morality refers to judgments about a person's overall moral character, whereas act-based morality refers to judgments about the rightness or wrongness of an act. This distinction may be reflected in the structure of punitive attitudes. Specifically, people may make punitive judgments about offenders in general (corresponding to person-centered moral judgment) that are separate from punitive preferences regarding different types of crimes (corresponding to act-based moral judgment). As the following sections explain, theory from moral psychology indicates that people may especially differentiate among crimes that affect different types of victims.

Moral Foundations Theory

MFT posits that people have moral intuitions about five broad domains called “moral foundations” (Reference GrahamGraham et al. 2009; Reference HaidtHaidt 2007; Reference Haidt and JosephHaidt and Joseph 2004). Each moral foundation is associated with the perception (via moral intuition) that certain types of acts or ideas are virtuous, whereas violations of those things are moral transgressions and violators are moral transgressors.

Harm/Care promotes the sense that caring, kindness, and the protection of the vulnerable are virtuous, whereas causing suffering or failing to provide care are wrong. Fairness/Reciprocity elicits intuitions that equality, proportionality, and trustworthiness are virtuous, whereas inequality, unfairness, and cheating are moral violations.Footnote 1 Authority/Respect promotes intuitions that obedience and deference to authority, social hierarchies, and social customs are virtuous, whereas disrespect and disobedience are moral transgressions. Ingroup/Loyalty elicits the sense that loyalty and sacrifice for one's group (e.g., one's family, community, or country) are virtuous, whereas betrayal and selfishness are wrong. Finally, Purity/Sanctity, which has been described as the moralization of disgust (Reference HorbergHorberg et al. 2009), is associated with the intuition that bodily integrity and purity, however they are defined by one's culture or religion, are virtuous, whereas bodily degradation and impurity are moral transgressions. Intuitions relating to Purity center on the notion that “the body is a temple” and include “moral concepts such as sanctity and sin, purity and pollution, elevation and degradation” (Reference HaidtHaidt 2012: 100).

These moral foundations correspond to concern about three entities—individuals, collectives, and the “divine” (Reference HaidtHaidt 2012; see also Reference Shweder, Brandt and RozinShweder et al. 1997).Footnote 2 Harm and Fairness promote the view that individuals are an important moral unit, meaning that violations against individuals are egregious moral transgressions. Loyalty and Authority promote the view that collectives or social groups are important moral units and that violations against one's group are serious moral transgressions. Finally, Purity encompasses the idea that people are “temporary vessels in which a divine soul has been implanted,” meaning that the divine soul is an important moral unit and violations against bodily integrity are moral transgressions (Reference HaidtHaidt 2012: 100). Thus, violations against the “divine” are, in practice, typically violations against the body.

Although all people may be predisposed to view these concerns as moral, every person does not endorse all moral foundations equally. Rather, because different (sub)cultures define different issues as having moral significance (Reference GrahamGraham et al. 2009; Reference HaidtHaidt et al. 1993; Reference Shweder, Brandt and RozinShweder et al. 1997), socialization may determine the set of moral foundations that individuals most endorse (Reference HaidtHaidt 2007, Reference Haidt2012; Reference Haidt and GrahamHaidt and Graham 2007; Reference Haidt and JosephHaidt and Joseph 2004). Thus, the particular sets of moral intuitions that people experience are likely, in large part, a product of the social and cultural values to which they are exposed as children. This variation in the endorsement of moral foundations among individuals means that people have different levels of intuitive moral concern about transgressions against individuals, collectives, and the “divine.”

Punitiveness Toward Offenders and Offenses

Overall, moral psychology research suggests the necessity of distinguishing between punitiveness toward offenders (i.e., persons) and crimes (i.e., acts), especially crimes committed against different types of victims (i.e., individual, collective, or divine). Moreover, because punitive judgments are rooted in moral intuitions (Reference RobinsonRobinson et al. 2007), individuals’ moral foundations likely influence offender- and victim-centered punitiveness in diverse ways.

Offender-centered punitiveness describes punitiveness toward criminals in general or toward specific types of offenders (e.g., juvenile offenders), regardless of the specific crimes committed. Multiple moral foundations likely motivate offender-centered punitiveness (Reference CantonCanton 2015; Reference Silver and SilverSilver and Silver 2017). One set of moral responses may flow from the perspective, discussed earlier, of offenders as threats to shared social or religious values (Reference DurkheimDurkheim 1964[1933]; Reference Tyler and BoeckmannTyler and Boeckmann 1997). Specifically, the moral foundations Loyalty, Authority, and Purity are thought to be group-oriented (or “binding”) in that they center around group norms, rules, and customs, including those that dictate standards of bodily purity or sanctity; violations of these foundations are transgressions against society (Reference GrahamGraham et al. 2009). To people who endorse these foundations, then, offenders—who, by definition, flout social rules—may be viewed as having transgressed morally against society. In turn, endorsement of the binding foundations (Loyalty, Authority, and Purity) may be associated with greater offender-centered punitiveness.

The foundations that center on individuals (Harm and Fairness, also known as “individualizing” foundations) may also be relevant to offender-centered punitiveness. To those who heavily endorse only these foundations, crimes are not transgressions against society, but rather acts carried out by individuals against other individuals. Moreover, as individuals themselves, offenders are worthy of moral concern. To the extent that harsh punishments may be disproportionate (violating the Fairness foundation) or cause offenders to unduly suffer (violating the Harm foundation), the endorsement of these foundations may reduce offender-centered punitiveness.

By contrast, victim-centered punitiveness refers to punitive responses to crimes against different victim types. Moral concerns may also shape victim-centered punitiveness. As noted earlier, the moral foundations correspond to moral concerns about three types of entities: individuals, collectives, and the “divine.” Violations of the moral foundations associated with each are transgressions against the relevant entities. Because people endorse different sets of moral foundations, they are differently sensitive to acts committed against individuals, collectives, and bodily purity/sanctity.

People may thus have different punitive responses to crimes against different victim types (Reference BrubacherBrubacher 2014). Specifically, crimes can be divided into three groups based on the units of moral concern implicated by moral foundations: those committed against individuals (e.g., robbery or assault of a person), collectives (e.g., theft from the government, treason), and bodily integrity or the “divine” (e.g., incest, illegal drug use).Footnote 3 In turn, punitive attitudes can be expected to vary on the basis of the moral orientations that people endorse, as the endorsement of the relevant foundations should increase the perceived egregiousness of crimes against the corresponding victim types. Three dimensions of victim-centered punitiveness therefore exist: individual, collective, and divine.

The Current Study

This paper examines whether the punitive types suggested by MFT (offender-centered punitiveness and victim-centered punitiveness) are empirically distinct. Additionally, this study tests specific hypotheses regarding the moral foundations associated with each type of punitiveness.

Because the binding moral foundations (Loyalty, Authority, and Purity) may lead people to view offenders as committing transgressions against society, whereas the individualizing foundations (Harm and Fairness) may produce concern for individual offenders, I hypothesize the following regarding offender-centered punitiveness:

H1: Loyalty, Authority, and Purity are associated with greater offender-centered punitiveness.

H2: Harm and Fairness are associated with reduced offender-centered punitiveness.

To the extent that the moral foundations promote varying levels of moral concern for individual, collective, and “divine” victims, I hypothesize the following regarding victim-centered punitiveness:

H3: Harm and Fairness are associated with greater individual victim punitiveness.

H4: Loyalty and Authority are associated with greater collective victim punitiveness.

H5: Purity is associated with greater divine victim punitiveness.

Data and Method

Data for this study were collected in the summer of 2015 using an anonymous, nationwide, online survey of adult Americans. Respondents were recruited through Amazon's MechanicalTurk (MTurk), where members perform “human intelligence tasks” (HITs) such as surveys in exchange for payment. Research consistently suggests that MTurk is a good source of high-quality data and supports its use in social research (Reference MullinixMullinix et al. 2015; Reference WeinbergWeinberg et al. 2014),Footnote 4 and MTurk samples are commonly used in research published in leading social science journals (e.g., Reference AbascalAbascal 2015; Reference MunschMunsch 2016). Respondents were restricted to United States residents over the age of 18 who had a 90 percent or higher prior approval rating on MTurk (reflecting their completions of prior HITs).

Dependent Variables

Offender-Centered Punitiveness

Offender-centered punitiveness was measured using four items from a scale used by Reference Pickett and BakerPickett and Baker (2014) to measure support for punitive policies. Following the typical approach to measuring punitiveness, the items emphasize the offenders who are to be punished, while providing little to no information about the victims affected. Specifically, respondents were asked to report on a five-point scale how much they supported or opposed the following policies: (1) Increasing the use of the death penalty for offenders who are found guilty of murderFootnote 5; (2) Locking up fewer juvenile offenders; (3) Reducing the use of mandatory minimum sentencing laws, like “Three Strikes,” for repeat offenders; and (4) Sending fewer juveniles to adult courts. Responses were coded so that higher scores indicated greater punitiveness, then summed to form a scale (alpha = 0.720).

Victim-Centered Punitiveness

Respondents were asked to indicate the punishment they thought would be appropriate for nine offenses (or deviant actions that are often criminalized) against different types of victims. Punishment options ranged from no punishment to life in prison.Footnote 6 Three of the crimes victimized individuals (stealing an elderly woman's purse; robbing a stranger at gunpoint; beating one's spouse badly enough to hospitalize him/her), three victimized a collective (stealing government secrets and putting them on the internet; sending money to a terrorist organization that has targeted your country; defacing a national landmark, such as Mount Rushmore), and three violated standards of bodily purity (having consensual sex with one's own 20-year-old daughter; smoking crack cocaine; performing oral sex on a stranger for money). Responses to each set of three items were summed to form scales measuring Individual Victim Punitiveness (alpha = 0.642), Collective Victim Punitiveness (alpha = 0.676), and Divine Victim Punitiveness (alpha = 0.601).Footnote 7

Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were employed to assess the discriminant validity of the victim-centered punitiveness measures. Principal axis factoring using promax rotation showed that the nine items composing the victim-centered punitiveness measures loaded on three factors at 0.5 or higher, with one exception (“Having consensual sex…,” with a factor loading of 0.374). When the offender-centered punitiveness items were included, the items loaded on a separate factor as expected. Confirmatory factor analysis also supported the formation of the victim-centered measures. For a three-factor solution corresponding to individual victim, collective victim, and divine victim punitiveness, the relevant parameters were all within (or very near) the suggested guidelines for assessing goodness of fit: Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) = 0.033; Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.057; Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.960; Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.940. Neither a one-factor solution nor a two-factor solution (treating the collective and divine victim measures as a single factor to reflect their roots in the binding foundations) produced acceptable goodness of fit measures (SRMR = 0.071; RMSEA = 0.129; CFI = 0.766; TLI = 0.689 for a one-factor solution; SRMR = 0.061; RMSEA = 0.112; CFI = 0.831; TLI = 0.766 for a two-factor solution).

Independent Variables

Moral Foundations

Measures for the moral foundations were adapted from the 20-item, two-part Moral Foundations Questionnaire (MFQ) (Reference GrahamGraham et al., 2011). Part one of the MFQ asks respondents, “When you decide whether something is right or wrong, how relevant or irrelevant are the following considerations to your thinking?” An example of an item is, “Whether or not someone conformed to the traditions of society,” measuring Authority. Reponses are measured on a five-point scale (1 = Very irrelevant, 5 = Very relevant). Part two of the MFQ asks respondents to rate their agreement with statements reflecting each of the five moral foundations. An example of an item is, “People should not do things that are disgusting, even if no one is harmed,” measuring Purity. Responses are measured on a five-point scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 5 = Strongly agree). Two items in each Part correspond to each of the moral foundations.

Scales measuring each of the moral foundations were constructed by recoding the items so that higher scores corresponded to greater endorsement of each foundation, then taking the average of the appropriate items from each scale (see Appendix A). Items that appreciably reduced the reliabilities of these scales were removed, so that the final reliabilities for each moral foundation are as follows: Authority (alpha = 0.703); Loyalty (alpha = 0.648); Purity (alpha = 0.846); Harm (alpha = 0.707); and Fairness (alpha = 0.711).Footnote 8 Confirmatory factor analysis supported the formation of these measures (SRMR = 0.037; RMSEA = 0.046; CFI = 0.984; TLI = 0.954).

Control Variables

Controls are included for known correlates of punitiveness, particularly racial resentment, fear of crime, prior victimization, and respondents’ demographics. Following prior studies (Reference Unnever and CullenUnnever and Cullen 2010), Racial Resentment was measured using five items from the Symbolic Racism 2000 scale (Reference Patrick J and SearsHenry and Sears 2002) (e.g., Generations of slavery and discrimination have created conditions that make it difficult for Blacks to work their way out of the lower class). All responses were coded so that higher scores correspond to greater racial resentment, then summed to form a scale (alpha = 0.924).

Fear of Crime was measured by asking respondents to indicate on a five-point scale how afraid they were that someone would try to do the following in the next year: (1) Break into your house; (2) Rob or mug you; (3) Rape or sexually assault you; and (4) Murder you. Responses were summed to create a scale (alpha = 0.908). The item measuring Prior Victimization asked respondents whether they had been the victim of a crime in the past five years and was coded 1 = yes, 0 = no.

Respondents’ gender, race, ethnicity, age, education, and income were also included. Gender was coded so that 1 = Female and 0 = male. Race/ethnicity was coded so that 1= non-Hispanic white, and 0 = nonwhite or Hispanic. Age was measured in years. To account for a potential nonlinear relationship between age and punitiveness (Reference ChiricosChiricos et al. 2004), a quadratic term (Age2) was included. Education was measured so that 1 = High school graduate or less, 2 = Some college, 3 = Associate degree, 4 = Bachelor's degree, and 5 = Master's degree or beyond. Finally, income was measured in intervals so that 1 = Less than $10,000; 2 = $10,000–19,999; 3 = $20,000–$29,999; 4 = $30,000–$49,999; 5 = $50,000–$69,999, 6 = $70,000–$99,999; and 7 = $100,000 or more.

Analysis

Respondents who had item missing data on any of the measures are dropped from the analysis, resulting in an analytic sample of N = 915. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the analytic sample. The analysis then proceeds in three stages. First, a model predicting offender-centered punitiveness from the moral foundations and controls is presented. Second, models predicting each type of victim-centered punitiveness from the moral foundations and controls are estimated. Third, to assess whether the moral foundations exert effects on victim-centered punitiveness net of offender-centered punitiveness, full models are estimated that predict victim-centered punitiveness from the moral foundations, controls, and offender-centered punitiveness. Finally, I conduct supplemental analyses that weight the data to match the general population, include measures of conservatism, and disaggregate the victim-centered punitiveness measures.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics

Note: Standard deviations are omitted for dummy variables.

Abbreviations: SD = standard deviation.

Where appropriate, comparisons between coefficients across multiple models are made using the multivariate regression “mvreg test” function in Stata, which provides an F-test of the equivalence of the coefficients across regression models with the same sample and independent variables but different dependent variables (Reference DattaloDattalo 2013). In assessing whether the effects of the moral foundations differ across the victim-centered punitiveness models, the effect size of the foundation relevant to each type of victim-centered punitiveness is compared to the effect size of the same foundation in the other two models. Because two hypotheses are tested for each moral foundation, the alpha level required to reject the null hypothesis for each is adjusted using the Bonferroni method: α = 0.05/2 = 0.025. For all other assessments of effect size across multiple models, a single test is performed using “mvreg” to determine the equality of coefficients across models and a standard alpha level (0.05) is used.

Results

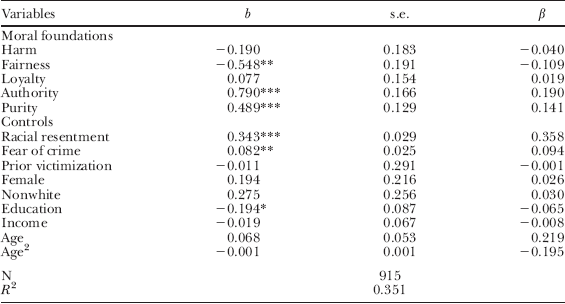

Table 2 presents regression models predicting offender-centered punitiveness from the moral foundations and controls. As hypothesized, Authority (b = 0.790, p < 0.001) and Purity (b = 0.489, p < 0.001) both have significant, positive relationships with offender-centered punitiveness, whereas Fairness has a strong negative relationship with offender-centered punitiveness (b = −0.548, p = 0.004). By contrast, neither Harm nor Loyalty has a significant effect on offender-centered punitiveness. This suggests offender-centered punitiveness is driven largely by moral concerns about the proportionality of punishments and the violation of social rules. By contrast, moral concerns about harm are unrelated to offender-centered punitiveness, possibly because concerns about harm to offenders may be offset by concerns about harm to victims (Reference CantonCanton 2015). Additionally, the null effects for Loyalty suggest that although people view the violation of group rules and norms as punishable, they do not perceive offenders as “betraying” their communities.

Table 2. Regression Model Predicting Offender-Centered Punitiveness

†p < 0.10; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (two-tailed).

Abbreviations: b = unstandardized regression coefficient; s.e. = standard error; β = standardized regression coefficient.

In general, the control variables are associated with offender-centered punitiveness in ways consistent with prior literature. Racial resentment and fear of crime are both positively related to offender-centered punitiveness (b = 0.343, p < 0.001; b = 0.082, p = 0.001). Greater education is associated with reduced punitiveness (b = −0.194, p = 0.028).

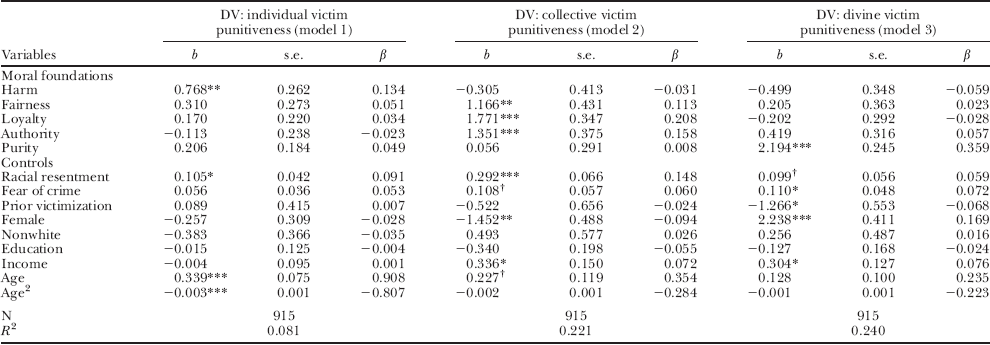

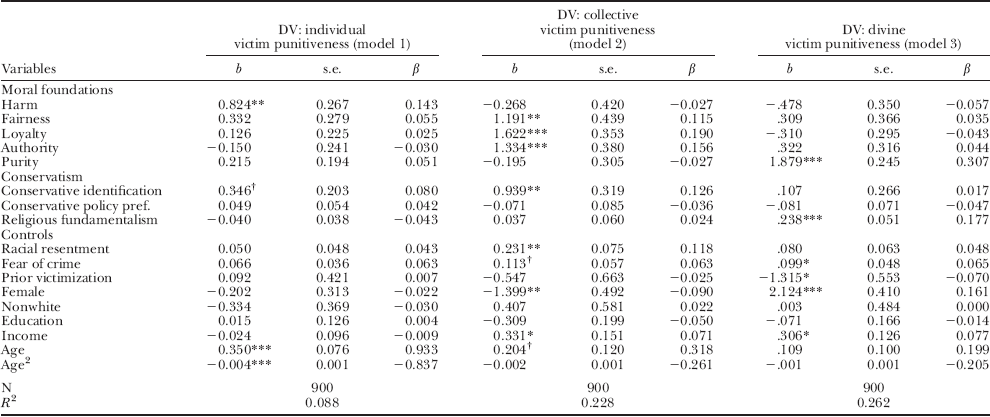

Table 3 presents results for victim-centered punitiveness. With few exceptions, each type of victim-centered punitiveness is associated strongly, and solely, with the hypothesized moral foundations. In Model 1, Harm predicts greater individual victim punitiveness (b = 0.768, p = 0.003), although Fairness does not have a statistically significant effect on individual victim punitiveness. As predicted, Loyalty (b = 1.771, p < 0.001) and Authority (b = 1.351, p < 0.001) are strongly related to collective victim punitiveness (Model 2). Similarly, those who endorse Purity express more divine victim punitiveness (b = 2.194, p < 0.001). Although Fairness is not significantly related to individual victim punitiveness, it has an unexpected positive effect on collective victim punitiveness in Model 2 (b = 1.166, p = 0.007). Finally, it is worth noting that the standardized effect sizes for the relevant moral foundations are larger than those of racial resentment, fear, or any other variables (other than age in Models 1 and 2).

Table 3. Regression Models Predicting Victim-Centered Punitiveness

† p < 0.10; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (two-tailed).

Abbreviations: b = unstandardized regression coefficient; s.e. = standard error; β = standardized regression coefficient.

For the most part, the differences in the effects of the different foundations on each type of victim-centered punitiveness are statistically significant. That is, the coefficient for Harm is significantly larger in the model predicting individual victim punitiveness than in the models for collective and divine victim punitiveness (respectively, F = 7.86, p = 0.005; F = 12.34, p < 0.001). The effects of Loyalty are significantly larger for collective victim punitiveness than for individual or divine victim punitiveness (respectively, F = 24.79; F = 26.29; p < 0.001 for both). The effects of Authority are also greater for collective victim punitiveness than for individual or divine victim punitiveness (respectively, F = 17.73, p < 0.001; F = 5.01, p = 0.025). Finally, Purity predicts divine victim punitiveness more strongly than it predicts individual or collective victim punitiveness (respectively, F = 61.28; F = 43.87; p < 0.001 for both). Put simply, the moral foundations appear to be associated with punitiveness in the ways that MFT would suggest.

There are also substantial differences in how the control variables are associated with offender- versus victim-centered punitiveness (see Tables 2 and 3). For example, whereas racial resentment is a strong predictor of offender-centered punitiveness (β = 0.358, p < 0.001), it is not significantly associated with divine victim punitiveness (β = 0.059, p = 0.074); the difference in the coefficients is highly significant (F = 365.87, p < 0.001). Similarly, fear of crime is associated with offender-centered punitiveness (β = 0.094, p = 0.001) and divine victim punitiveness (β = 0.072, p = 0.023), but not with individual or collective victim punitiveness (F = 3.48, p = 0.008). Compared to men, women express more divine victim punitiveness (β = 0.169, p < 0.001), but less collective victim punitiveness (β = −0.094; p = 0.003); there are no sex differences, however, for offender-centered punitiveness or individual victim punitiveness (F = 13.36, p < 0.001). Finally, income is associated with collective and divine victim punitiveness (β = 0.072, p = 0.025; β = .076, p = 0.018, respectively), but not with offender-centered punitiveness or individual victim punitiveness (F = 2.89, p = 0.022).

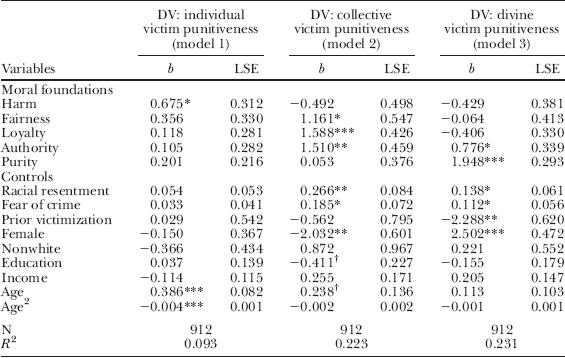

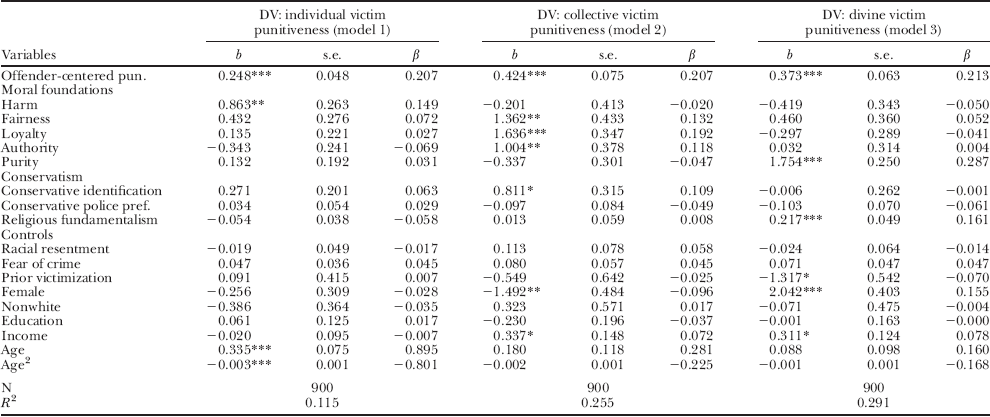

Table 4 presents the full models predicting each type of victim-centered punitiveness, controlling for offender-centered punitiveness. Although offender-centered punitiveness is strongly related to victim-centered punitiveness in each model, the results for the effects of the moral foundations are strikingly similar to those in Table 3. With the continued exception of Fairness, each moral foundation continues to be significantly associated with each type of victim-centered punitiveness in the hypothesized way, and the effect sizes are comparable to those in Table 3. Thus, the moral foundations have a strong effect on victim-centered punitiveness, above and beyond the effects of offender-centered punitiveness.

Table 4. Full Regression Models Predicting Victim-Centered Punitiveness from Offender-Centered Punitiveness, Moral Foundations, and Controls

† p < 0.10; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (two-tailed).

Abbreviations: b = unstandardized regression coefficient; s.e. = standard error; β = standardized regression coefficient; pun. = punitiveness.

Supplemental Analyses

Three sets of supplemental analyses were conducted. First, the data were weighted using the General Social Survey (GSS) to better assess the generalizability of the results. Second, models including measures of respondents’ political and religious conservatism were estimated. Third, models were estimated that disaggregated the victim-centered punitiveness measures into their component items. Taken together, these analyses further our understanding of the moral foundations associated with punitiveness, as well as provide sensitivity analysis for the main findings.

GSS Weighting

Because the data for this study derive from a nonprobability online sample, supplemental analysis was conducted after weighting the data to match population characteristics. Since nonrandom selection into a sample is problematic primarily if respondents systematically differ from the population on the outcome variable, I weight based on punitiveness as well as demographic characteristics.

The GSS, an annual, nationally-representative survey of noninstitutionalized adults in the United States, asks respondents about their death penalty support. Death penalty support is strongly representative of general punitiveness (Reference LibermanLiberman 2013). As such, weighting per this measure likely provides results closer to what would be obtained if the MTurk respondents held similar punitive attitudes to GSS respondents. The exact wording of the 2014 GSS question was included in the MTurk survey: “Do you favor or oppose the death penalty for persons convicted of murder?” The response categories are “Favor” and “Oppose.” Weights were constructed that adjust for both the differences between the MTurk and GSS respondents on death penalty support, and the differences between the MTurk respondents and the U.S. population on gender, race, and educational attainment.

The weighted results are presented in Appendix B for offender-centered punitiveness (Table B1), victim-centered punitiveness (Table B2), and for the full models (Table B3). Overall, the results from these models are strikingly similar to the nonweighted results, bolstering confidence in the external validity of the findings.

Conservatism Measures

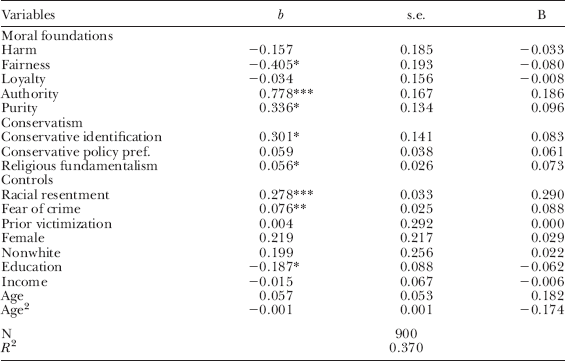

Conservatism is thought to be, at least in part, an outcome of the binding moral foundations Loyalty, Authority, and Purity (Reference GrahamGraham et al. 2009; Reference HaidtHaidt 2012; Reference Haidt and GrahamHaidt and Graham 2007). Theoretically, then, conservatism could be expected to partially mediate the relationships between the moral foundations (particularly Authority, Loyalty, and Purity) and indicators of punitiveness (Reference KolevaKoleva et al. 2012). Political conservatism and related orientations such as religious fundamentalism were thus excluded from the main models to avoid overcontrol bias (Reference Elwert and WinshipElwert and Winship 2014). To assess whether the effects of the moral foundations are, in fact, distinguishable from the effects of political and religious conservatism, I estimated models controlling for three forms of conservatism: conservative identification, conservative policy preference, and religious conservatism.

Appendix C presents the results for offender-centered punitiveness (Table C1), victim-centered punitiveness (Table C2), and for the full models (Table C3). Overall, the results are very similar to those in the main analysis. Although the coefficients for some of the moral foundations are reduced in some models (in line with the mediation hypothesis), the differences are small and inconsistent. Overall, then, this analysis indicates that the effects of the moral foundations on punitiveness are largely independent of individuals’ political and religious preferences.

Disaggregating the Victim-Centered Punitiveness Measures

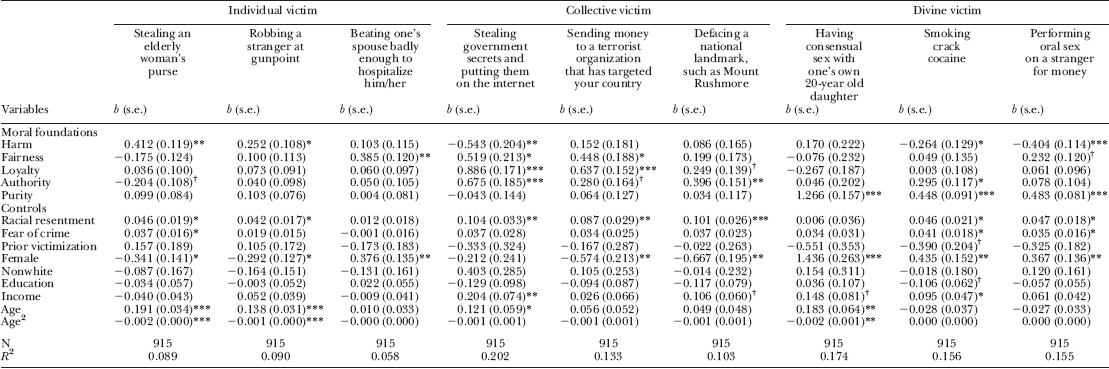

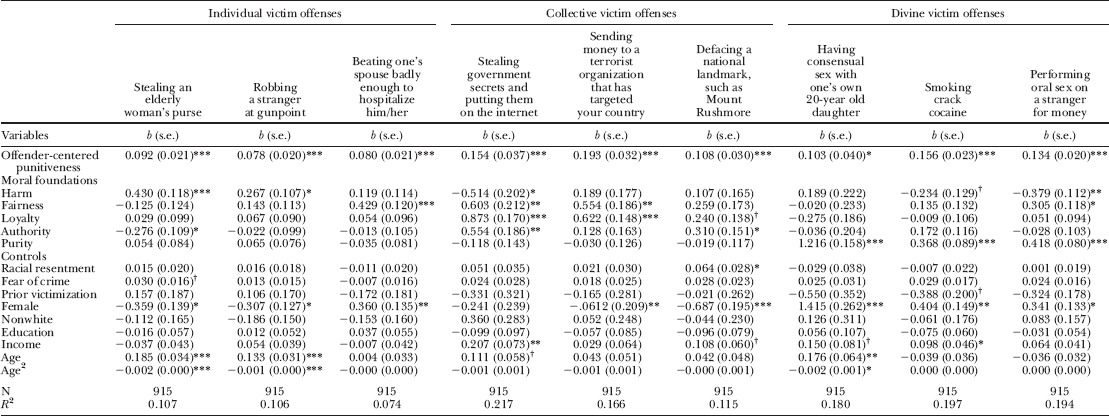

A final set of analyses examines punitiveness toward each of the crimes/deviant actions included in victim-centered punitiveness measures. If the moral foundations predict punitiveness toward each specific offense in ways consistent with MFT, it may increase our confidence in the validity of the victim-centered punitiveness measures. The results for the moral foundations and controls (Table D1) and for the full models (Table D2) are presented in Appendix D.

For the most part, the results show that each of the individual offenses is strongly associated with at least one of the expected moral foundations, and not with the other foundations, as MFT predicts. An exception is that Harm appears to predict reduced punitiveness toward certain offenses (stealing government secrets and putting them on the internet, smoking crack cocaine, and performing oral sex on a stranger for money). To someone who strongly endorses Harm, perhaps, such “victimless” offenses may not be viewed as morally wrong, whereas punishing someone who has committed no moral violations may be viewed as wrong. Thus, barring a few idiosyncratic results, the disaggregated analysis supports the use of the victim-centered punitiveness measures and the theoretical framework presented in the current study.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study demonstrates the importance of distinguishing, both theoretically and empirically, between offender-centered and victim-centered punitiveness. Indeed, offender-centered punitiveness is associated with a strikingly different set of factors than are any of the three forms of victim-centered punitiveness. Key contributions of this study are therefore to present a new framework with which to consider public punitiveness, and to provide the first empirical evidence regarding the correlates of victim-centered punitiveness.

Another important contribution of this study is to introduce concepts from moral psychology to the study of punitiveness. Despite the central role of moral outrage in classical sociological accounts of punishment (Reference DurkheimDurkheim 1964[1933]), and the clear link between moral judgments and punitive preferences (e.g., Reference DarleyDarley 2009), previous research on public punitiveness has so far neglected the role of moral intuition. Indeed, to my knowledge, no previous studies testing theoretical models of punitiveness have included any measure of respondents’ personal moral values or foundations. These findings clearly demonstrate that offender- and victim-centered punitiveness are empirically distinct categories, and that the specific moral foundations that individuals endorse are important predictors of types of punitive attitude.

To claim that moral values underpin punitive preferences raises questions about the role that individuals’ moral preferences should play in determining criminal punishment. Whereas this study is intended to be descriptive, it may help to inform an ongoing debate regarding the role of lay moral judgments in punishment. On one side, legal scholar Paul Robinson argues that lay punitive preferences based in moral intuition should provide the basis for criminal law, and that doing so is “essential to law's crime control effectiveness” (2013: 141), particularly its ability to “harness the powerful forces of social influence and internalized norms” (2013: 141; see also Reference Robinson and DarleyRobinson and Darley 2007). Thus, Robinson argues that lawmakers should seek to “maximize [a criminal] code's moral credibility with the community that it governs” (2013: 91). Of course, using moral intuitions to guide criminal punishment may also have severe drawbacks. Intuitions of justice shared by a majority may produce punitive policies that are inconsistent with deontological justice, as in the case of slavery or Nazism (Reference RobinsonRobinson 2013: 167). This problem may be exacerbated if intuitions of morality differ systematically across social groups, as MFT suggests that they do (Reference GrahamGraham et al. 2009, Reference Graham2011). Echoing this argument, other scholars (e.g., Reference GreeneGreene 2013) have argued that because moral intuitions tend not to favor people who are viewed as out-group members, it is imperative to overcome our moral intuitions, and to implement policy based on rational perspectives, such as utilitarianism, instead. The current study shows that a plurality of moral views, shared by different social groups, influence punitive attitudes. Thus, maximizing “moral credibility” for all people, and effecting this in ways that are consistent with deontological conceptualizations of justice, may be difficult. However, continued analysis in this area is certainly needed. Research suggests that extant laws and legal distinctions (e.g., regarding causation and intent) already adhere closely to people's intuitions about morality (Reference RobinsonRobinson 2013).

Whereas this study does not suggest that any particular punishment regime be adopted, it may help to explain variation in extant punitive regimes, both cross-culturally and over time. Cultures differ in the extent to which they emphasize certain virtues, making the widespread endorsement of specific moral foundations variable across cultures (Reference HaidtHaidt 2012). Given the high correspondence between lay intuitions about justice and criminal law (Reference RobinsonRobinson 2013), it seems reasonable to expect that cultural differences in morality are expressed as differing punitive regimes. For example, whereas the strong endorsement of Purity is largely concentrated among political and religious conservatives in the United States (Reference GrahamGraham et al. 2009; Reference HaidtHaidt 2012), Purity may be more widely endorsed in other cultures where religious values regarding bodily sanctity are more prevalent (Reference HaidtHaidt 2012). This phenomenon could help to explain why in some countries, perceived violations of bodily integrity (such as homosexuality) are punishable by death, life in prison, or other harsh sanctions.

The framework developed here might also help to explain temporal shifts in punishment regimes. Although people's moral foundations are difficult to change at the individual level (Reference HaidtHaidt 2012), new generations may be socialized to endorse different sets of moral foundations as social mores change. Over time, punitive practices may change accordingly (Reference PinkerPinker 2011). As the United States grows less traditionalist and more secular (Reference BruceBruce 2002), for example, this phenomenon might be reflected in the ongoing trend toward the decriminalization of acts associated with violations of the binding foundations, especially Purity (e.g., homosexual activity, sex work, and drug use) (Reference PinkerPinker 2011: 636). Regarding offender-centered punitiveness, an increasing emphasis on the individualizing foundations Harm and Fairness during the “Humanitarian Revolution” of the 18th century (Reference PinkerPinker 2011: 133) might help to account for the reduction in capital and corporal punishments, as well as other institutionalized forms of violence like slavery, in Western cultures. Understanding popular intuitions of justice might also provide insight into the public's reception of proposed criminal justice policies. For example, an increasing emphasis on Harm and Fairness rather than the binding foundations could help to explain recent shifts toward “reintigrative populism” (Reference PickettPickett 2016).

Moral intuitions may also influence criminal justice policy through another avenue. According to the “elite manipulation” model of criminal justice policy formation (Reference BeckettBeckett 1997), politicians manipulate public sentiment about crime for their own political gain. Because they are associated with punitive judgments, the moral foundations may therefore provide politicians with a “menu” of sentiments that can be manipulated to influence public punitiveness. Indeed, research shows that people are especially responsive to messages framed in terms of the moral foundations that they endorse (e.g., Reference Feinberg and WillerFeinberg and Willer 2015).

The results also have implications for understanding debates regarding crime and punishment in the United States. Variation in the endorsement of different moral foundations may help to explain why social groups that endorse different moral foundations, such as liberals and conservatives, often find it difficult to reach consensus on issues where each side views itself as taking the more “moral” position (Reference HaidtHaidt 2012; Reference Haidt and GrahamHaidt and Graham 2007). In the context of criminal justice attitudes specifically, the endorsement of different sets of moral foundations by different groups may “explain why attitudes are so complex and intractable and how it is that people with different views about punishment often struggle to reach mutual understanding, much less agreement” (Reference CantonCanton 2015: 55).

Turning to this study's specific findings, offender-centered punitiveness and victim-centered punitiveness were generally both shaped by the moral foundations that respondents endorsed in the manner suggested by MFT, particularly for victim-centered punitiveness. Except for Fairness, the moral foundations were each associated with punitiveness toward crimes against the relevant victims: Harm predicted individual victim punitiveness; Loyalty and Authority predicted collective victim punitiveness; and Purity predicted divine victim punitiveness. Offender-centered punitiveness, on the other hand, was positively associated with Authority and Purity, but negatively associated with Fairness, which again is consistent with MFT.

The unexpected, countervailing effects of Fairness on offender-centered punitiveness and collective victim punitiveness may be explained by some elaboration of MFT. Reference HaidtHaidt (2012) suggests that rather than comprising a single concept, Fairness has two component moral foundations: Fairness/Cheating, which deals with concerns about reciprocity and taking more than one's fair share; and Liberty/Oppression, which emphasizes equality and freedom from oppression. Fairness/Cheating is thought to be, like Authority and Loyalty, a binding foundation, in that it protects the group from individuals who would take more than their fair share (Reference HaidtHaidt 2012). Liberty/Oppression, on the other hand, is thought to be an individual-oriented foundation like Harm, in that it protects individuals from being unjustly treated by those in power. Although the dual Fairness/Cheating and Liberty/Oppression foundations remain “provisional” (Reference HaidtHaidt 2012: 347), the distinction has important theoretical implications.

Specifically, the positive effects of Fairness on collective victim punitiveness might reflect concerns about the group-oriented Fairness/Cheating. Rather than perceiving offenders’ actions as unfairly affecting individuals, those who endorse the Fairness/Cheating foundation may perceive offenders who victimize the group for their own gain as taking advantage of the group or attempting to take more than their fair share. The negative effects of Fairness on offender-centered punitiveness, on the other hand, could be explained by the Liberty/Oppression component of Fairness. To the extent that overly harsh punishments involve the unfair removal of individuals’ liberty or the repression of individuals’ rights, those who endorse the Liberty/Oppression foundation may be reluctant to impose harsh punishments on offenders (Reference CantonCanton 2015). As such, the moral foundations appear to shape punitiveness in ways that are consistent with MFT.

The finding that offender-centered punitiveness is largely shaped by Authority and Purity also has interesting implications. Specifically, given that Authority and Purity both promote obedience to social or religious rules and customs, offender-centered punitiveness may stem from moral outrage that an offender has violated important social rules. This notion is consistent with “expressive” theories of punitiveness, which suggest that punitiveness results from a sense that society's values have been violated or threatened (Reference DurkheimDurkehim 1964 [1933]; Reference Tyler and BoeckmannTyler and Boeckmann 1997; Reference Unnever and CullenUnnever and Cullen 2010).

While this study focuses theoretically on punishment derived from moral outrage against offenders or offenses (i.e., retributive punishment), it is important to note that people endorse many punishment goals, and often do not cite retribution as the most important goal (Reference Cullen, Fischer and ApplegateCullen, Fischer, and Applegate 2000). The endorsement of certain moral foundations may be associated with support for punishment goals other than retribution. For example, endorsement of the moral foundations that promote concern for offenders (i.e., Harm and Fairness) could lead people to prefer punishment goals that involve greater consideration for offenders, such as rehabilitation (Brubacher, 2014). Similarly, it may be that people are more likely to support instrumental punishment goals such as deterrence and incapacitation when their moral foundations are not triggered. Another possibility relates to the dual process nature of moral judgments. Intuitions are thought to precede and strongly influence reasoned judgments (Reference HaidtHaidt 2001, Reference Haidt2012). Whereas Americans tend to report that multiple punishment goals are important (Reference Cullen, Fischer and ApplegateCullen, Fischer, and Applegate 2000), research suggests that in practice, punitive preferences track retributive desires more closely than concerns about deterrence or incapacitation (Reference AlterAlter et al. 2007; Reference CarlsmithCarlsmith et al. 2002). Thus, it may be that people's stated diverse punishment goals reflect after-the-fact justifications of their intuitions. Future research might address with these questions further.

In addition to showing that punitive attitudes are associated with individuals’ moral orientations, this framework may be useful for understanding various phenomena in criminal justice. For example, individuals’ “global” support for punitive policies in the abstract tends to be greater than their “specific” support for applying punishment in a given case (e.g., Reference ApplegateApplegate et al. 1996). To the extent that global questions about crime policy draw on ideas about how best to punish offenders in general, it may be that people respond primarily with offender-centered punitiveness. When information about specific crimes is given, however, people's attitudes may be more likely to reflect victim-centered punitiveness. While it is possible that support for punitive policies can reflect victim-centered punitiveness (e.g., policies governing drug use), or for concerns about offenders to influence specific punitive attitudes (e.g., when information about offenders’ circumstances is provided), the operationalization of these concepts in the extant literature generally parallels the offender-centered vs. victim-centered dichotomy identified here. For example, Reference ApplegateApplegate et al. (1996) classic study assessed people's global support for a “Three Strikes” policy, then asked them to sentence offenders based on vignettes in which offenders had committed various offenses (most of them against individuals). Whereas sentencing offenders may evoke moral outrage based on concerns about Authority or Purity violations (though this moral outrage may be tempered by Fairness concerns), asking people to consider crimes against individuals may primarily provoke concerns about Harm violations, which are more weakly related to punitiveness. Moreover, because these attitudes are driven by intuitive, automatic processes (i.e., moral foundations), people may be unaware that their attitudes are contradictory at all. To best capture individuals’ overall punitiveness, then, it might be useful to combine indicators of offender-centered and victim-centered punitiveness into an overall measure of punitive attitudes.

A related avenue for future research concerns the intersection between judgments about crimes and offenders. Moral psychologists argue that some actions are viewed as being especially indicative of a person's poor moral character, even if—compared to other actions in the abstract—they are not considered to be extremely morally egregious, a phenomenon known as “act-person dissociation” (Reference TannenbaumTannenbaum et al. 2011; Reference UhlmannUhlmann et al. 2014, Reference Uhlmann2015). In one study, respondents rated the act of assaulting a coworker as more morally wrong than muttering a racial slur in the company of a coworker, but rated a person who muttered a racial slur as having a worse moral character than a person who committed an assault (Reference UhlmannUhlmann et al. 2014). This phenomenon may have important implications for understanding criminal justice attitudes. For example, although people consistently rate sex crimes as being less severe or worthy of punishment than murder (e.g., Reference Sellin and WolfgangSellin and Wolfgang 1964), people tend to view sex offenders as “the worst of the worst” (Reference Mancini and PickettMancini and Pickett 2016). A possible explanation for this is that sex offenses are viewed as more indicative of the moral character of individuals than is the more serious crime of murder. Future research should further consider how moral intuitions about offenders and crimes (i.e., people and acts) may shape punitive attitudes together, particularly to the extent that moral judgments about offenses may color views of offenders.

This research also suggests that studies focusing exclusively on offender-centered punitiveness provide a limited view of the other causes and correlates of punitive attitudes. Various sociodemographic variables (racial resentment, fear of crime, sex, and income) had different effects on each type of punitiveness. Notably, racial resentment is one of the most robust known predictors of offender-centered punitiveness (e.g., Reference Barkan and CohnBarkan and Cohn 1994; Reference Unnever and CullenUnnever and Cullen 2010), a finding that was replicated here for offender-, but not all types of victim-centered, punitiveness. Although racial resentment was a strong predictor of punitiveness toward crimes against collectives, it had smaller or negligible effects on punitiveness toward crimes against individuals or the divine. Moreover, all of these effects disappeared entirely when offender-centered punitiveness was controlled. Thus, the results highlight the potential theoretical gain that might be obtained by separately considering victim- and offender-centered punitiveness, particularly in the context of racial attitudes.

These findings also, however, raise questions about the role of social context, particularly regarding offenders’ race. In the United States, violent crime and street crime have historically been characterized as a “young Black problem” (Reference WelchWelch 2007), and holding this view is associated with greater punitiveness (Reference ChiricosChiricos et al. 2004; Reference Pickett and ChiricosPickett and Chiricos 2012). Victim-centered punitiveness may therefore be influenced by racialized typifications of offenders who commit certain types of crimes—particularly violent crimes against individuals. Indeed, the results suggest that racial typifications may play a role in individuals’ punitiveness toward violent crimes or street crimes such as those used to compose the individual victim punitiveness measure. Specifically, racial resentment is significantly associated with two of the three crimes composing the individual victim punitiveness measure (stealing an elderly woman's purse and robbing a stranger at gunpoint).Footnote 9 However, these effects are rendered insignificant by the inclusion of the offender-centered punitiveness measure. This suggests that while the crimes may elicit punitiveness toward an imagined nonwhite offender, these effects may be be attributable to offender-centered punitiveness. It would be fruitful, however, for future research to further explore how typifications of offenders (or of victims; see, e.g., Reference PickettPickett et al. 2013) affect victim-centered punitiveness.

A related question is how social factors, such as offender race, might intersect with the moral foundations in influencing offender-centered punitiveness. Research has linked the endorsement of the binding moral foundations (Loyalty, Authority, and Purity) to expressions of racial animus (Reference Kugler and JostKugler, Jost, and Noorbaloochi 2014), perhaps because racial animus may reflect concerns related to these foundations: loyalty to one's in-group, the perpetuation of existing social hierarchies, or the “purity” of one's race. More generally, research suggests that because moral intuitions likely evolved to promote cooperation within groups or “tribes,” they may steer people to be unduly harsh toward individuals who are perceived as out-group members—a distinction often marked by race in today's world (Reference GreeneGreene 2013). This suggests that the binding moral foundations might differentially affect punitiveness toward offenders of different races, or among respondents of different races. Thus, another avenue for future research might be to consider how the moral foundations interact with offenders’ race, or with racial typifications of offenders, to influence punitiveness. Specifically, we might expect individuals who strongly endorse the binding foundations to be more punitive toward nonwhite offenders, or when they perceive offenders in general to be racial minorities. We might also expect white survey respondents—who are more likely to view Black-typified offenders as being outgroup members—to have punitive attitudes that are more strongly tied to the binding moral foundations. Ancillary analysis shows that authority is, in fact, a stronger predictor of offender-centered punitiveness among whites in the sample (β = 0.211, p < 0.001) than among nonwhites (β = 0.053, p = 0.575), although Purity remains a strong predictor of attitudes in both samples.

This study has three main limitations. First, it draws on data from an online convenience sample. Thus, there is no theoretical basis for assuming the findings will generalize to the U.S. population. However, several findings are suggestive of high external validity. First, the results for the relationships between the controls (e.g., racial resentment, fear of crime, education) and offender-oriented (i.e., “general”) punitiveness are highly consistent with those obtained in previous studies using nationally representative samples (Reference ChiricosChiricos et al. 2004; Reference Unnever and CullenUnnever and Cullen 2010). Second, the key findings were largely unchanged after weighting responses to match demographic and punitive characteristics of the U.S. population. An important next step, however, will be for researchers to replicate this analysis using a more representative sample.

A second limitation of the study regards the validity of the victim- and offender-centered punitiveness measures. Given that a relatively small number of items is used to comprise each victim-centered punitiveness scale, it is plausible that the results may be somewhat idiosyncratic to the offenses included in the measures. For example, sex work has been under challenge in many jurisdictions, and it is possible that people may view sex crimes differently than other types of crimes as a consequence. There are a few reasons, however, to have confidence in the results. One is that factor analysis showed that the items loaded on three distinct factors. Additionally, supplemental analysis predicting punitiveness toward each of the crimes/deviant actions composing the victim-centered punitiveness measures (e.g., beating one's spouse, defacing a national landmark, smoking crack cocaine) showed that, consistent with MFT, at least one of the expected moral foundations was associated with each individual offense (Appendix D). It would be instructive, however, to replicate this study using measures that include a broader variety of crimes, particularly since some idiosyncratic results do emerge from the disaggregated analysis. In doing so, future research could expand upon the theory laid out here to better understand how the moral foundations influence punitive attitudes about specific crimes.

Regarding the offender-centered punitiveness measures, it is important to note that the items used to measure offender-centered punitiveness were drawn from a scale intended to measure support for punitive policies (Reference Pickett and BakerPickett and Baker 2014), rather than one that had been specifically designed to measure offender-centered punitiveness. While the items in this scale all ask respondents how much they support or oppose punishment for different kinds of offenders, two of the items specifically reference offenses (murder and repeat offenses). Thus, it is possible that this measure captures victim-centered punitiveness as well as offender-centered attitudes. Additionally, it is likely that important aspects of offender-centered punitiveness (such as offenders’ race) are not captured by the measure. Just as this study assessed punitiveness toward crimes against different types of victims, then, it might be fruitful to examine punitiveness toward crimes committed by different types of offenders. Thus, future research might also attempt to develop a more focused and comprehensive measure of offender-centered punitiveness.

A third limitation of the study is that it draws exclusively from the MFQ to gauge intuitive moral processes. While the MFQ is widely used, other measures of the moral foundations exist. For example, the “sacredness” scale (Reference Jesse and JonathanGraham and Haidt 2012) asks people to report how much money they would require to perform actions that violate each of the moral foundations. Additionally, this study is somewhat limited in that it relies on the original five-foundation taxonomy of the moral domain, rather than on the proposed six-foundation taxonomy that separates Fairness into its two components (see Reference HaidtHaidt 2012). While measures of the six-foundation taxonomy are not yet available, future research should attempt to further explore how moral intuition shapes punitiveness using a wider variety of measures.

Despite these limitations, the current study provides strong theoretical and empirical contributions to the punitiveness literature. Specifically, this research develops a new framework for understanding punitiveness, and demonstrates the importance of distinguishing between offender- and victim-centered punitiveness in social research. Additionally, this research integrates theory from moral psychology to explain variation in punitiveness, and shows that intuitive moral processes may underlie diverse punitive attitudes. In doing so, this study opens up several new avenues for future research. A key takeaway is that in understanding punitiveness, moral intuitions matter, even though they have received little attention in the literature to date. Subsequent studies should continue to examine the moral bases for different types of punitive attitudes, and to explore the sources of offender- and victim-centered punitiveness.

Appendix A: Moral Foundations Questionnaire

Table A1 Moral Foundations Items and Measures

Note: This table shows all items appearing in the 20-item MFQ as well as the items used in each measure.

Appendix B: Weighted Results

Table B1 Weighted Regression Model Predicting Offender-Centered Punitiveness

† p < 0.10; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (two-tailed).

Abbreviations: b = unstandardized regression coefficient; LSE = linearized standard error.

Table B2 Weighted Regression Models Predicting Victim-Centered Punitiveness

† p < 0.10; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (two-tailed).

Abbreviations: b = unstandardized regression coefficient; LSE = linearized standard error.

Table B3 Weighted Regression Models Predicting Victim-Centered Punitiveness from Offender-Centered Punitiveness, Moral Foundations, and Controls

†p < 0.10; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (two-tailed).

Abbreviations: b = unstandardized regression coefficient; LSE = linearized standard error; pun. = punitiveness.

Appendix C: Conservatism Measures

Because different forms of conservatism may be related in different ways to criminal justice attitudes (Reference Silver and PickettSilver and Pickett 2015), two measures were used to assess respondents’ political conservatism and one measure was used to assess respondents’ religious conservatism. Conservative Identification is measured using a five-point scale on which respondents indicated their political preference (1 = Very liberal to 5 = Very conservative). Conservative Policy Preference is measured using four items asking about support for federal government policies (e.g., Federal spending for education should be reduced). Items were measured on a five-point scale (1 = Strongly agree to 5 = Strongly disagree), and coded so that higher scores corresponded to more conservative policy preferences, then summed to form a scale. Additionally, Religious Fundamentalism (a form of religious conservatism) was measured using four items assessing religious beliefs (e.g., the miracles described in the Bible really happened). Responses were given on a 5-point scale (1 = Strongly agree to 5 = Strongly disagree) and coded so that higher scores corresponded to greater religious conservatism, then summed to form a scale. Models including each of these measures are presented in Table C1 (offender-centered punitiveness), Table C2 (victim-centered punitiveness), and Table C3 (full models).

Table C1 Regression Model Predicting Offender-Centered Punitiveness with Conservatism Measures

†p < 0.10; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (two-tailed).

Abbreviations: b = unstandardized regression coefficient; s.e. = standard error; β = standardized regression coefficient; pref. = preference.

Table C2 Regression Models Predicting Victim-Centered Punitiveness with Conservatism Measures

† p < 0.10; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (two-tailed).

Abbreviations: b = unstandardized regression coefficient; s.e. = standard error; β = standardized regression coefficient; pref. = preference.

Table C3 Full Regression Models with Conservatism Measures

†p < 0.10; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (two-tailed).

Abbreviations: b = unstandardized regression coefficient; s.e. = standard error; β = standardized regression coefficient; pref. = preference.

Appendix D: Disaggregated Victim-Centered Punitiveness Measures

Table D1 Regression Models Predicting Punitiveness toward Specific Offenses

† p < 0.10; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (two-tailed).

Abbreviations: b = unstandardized regression coefficient; s.e. = standard error.

Table D2 Full Regression Models Predicting Punitiveness toward Specific Offenses

† p < 0.10; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (two-tailed).

Abbreviations: b = unstandardized regression coefficient; s.e. = standard error.