INTRODUCTION

The performance of foreign subsidiaries is regarded as an important focus in strategy and international business research (e.g., Andersson, Forsgren, & Holm, Reference Andersson, Forsgren and Holm2002; Delios & Beamish, Reference Delios and Beamish2001; Fang, Wade, Delios, & Beamish, Reference Fang, Wade, Delios and Beamish2007; Ma, Tong, & Fitza, Reference Ma, Tong and Fitza2013; Miller & Eden, Reference Miller and Eden2006). A central question is how strategies of multinational enterprises (MNEs) affect the financial performance of their foreign subsidiaries (Gaur & Lu, Reference Gaur and Lu2007; Zaheer, Reference Zaheer1995). MNEs often engage in two types of international strategies: product diversification and geographic diversification. Existing studies have predominantly focused on how corporate international diversification affects the performance of MNEs (e.g., Contractor, Kundu, & Hsu, Reference Contractor, Kundu and Hsu2003; Lu & Beamish, Reference Lu and Beamish2001; Tallman & Li, Reference Tallman and Li1996), but not on the performance of their foreign subsidiaries. As such, the literature on MNE diversification has not adequately addressed the question: How do MNE diversification strategies affect the financial performance of their foreign subsidiaries?

To address this question, we draw on the literature on types of control resulting from product diversification (i.e., strategic control and financial control) (Baysinger & Hoskisson, Reference Baysinger and Hoskisson1990). We aim to explore the relationship between MNE product diversification and foreign subsidiary performance, and introduce geographic diversification as a moderator into the relationship. In their study of product-diversified firms, Hitt, Hoskisson, and Kim (Reference Hitt, Hoskisson and Kim1997) differentiate among three types of firms in terms of the product diversification level in their study of organizational performance: non-diversified (single-business) firms, moderately diversified firms, and highly diversified firms. In general, non-diversified firms emphasize strategic controls, whereas highly diversified firms emphasize financial controls (Baysinger & Hoskisson, Reference Baysinger and Hoskisson1990). In contrast, moderately diversified firms may adopt a mix of the two types of controls.

Building on this theoretical insight, we shift attention from MNE performance to the performance of foreign subsidiaries. Operations of foreign subsidiaries are subject to and benefit from the strategies of their headquarters in different ways (Kostova & Zaheer, Reference Kostova and Zaheer1999; Westney, Reference Westney, Ghoshal and Westney1993). Because non-diversified firms and highly product-diversified firms involve different coordination and information-processing costs to the parent (Hashai, Reference Hashai2015; Hitt et al., Reference Hitt, Hoskisson and Kim1997; Lu & Beamish, Reference Lu and Beamish2004), their corresponding control mechanisms (strategic and financial control) may result in favorable outcomes (Hitt et al., Reference Hitt, Hoskisson and Kim1997). However, the two types of controls likely co-exist in moderately diversified firms. Different control mechanisms may impose conflicting demands on subsidiaries. It remains unclear to what extent corporate product diversification affects subsidiary performance.

In this study, we theorize that MNEs with different levels of product diversification may have different or even conflicting demands on their foreign subsidiaries. Foreign subsidiaries that are able to avoid the conflicting demands may perform better than those that cannot do so. Broadly speaking, foreign subsidiaries may benefit from strategic control for knowledge transfer because of their shared product lines with the parent firm, and may benefit from financial control for strategic flexibility. We argue that, in terms of product, foreign subsidiaries in non-diversified MNEs and highly diversified MNEs are more likely to achieve superior performance because the former can leverage the capabilities of the parent firm and the latter can achieve greater strategic flexibility – the ability and autonomy to modify and reconfigure its operating activities as well as to adopt efficient and effective practices (Hoskisson & Hitt, 1994). In contrast, foreign subsidiaries in moderately diversified MNEs may not be able to fully leverage the capabilities of the MNE or gain sufficient autonomy to make decisions. Thus, we propose a U-shaped relationship between MNE product diversification and foreign subsidiary performance. That is, foreign subsidiaries in MNEs with a moderate level of product diversification are less likely to perform better than those in MNEs with a low or high level of product diversification.

The literature on international diversification suggests that MNEs’ product diversification is often coupled with geographic diversification (Hilman, Reference Hilman2015; Sambharya, Reference Sambharya1995; Vachani, Reference Vachani1991). The coupling generates four types of strategic combination (Kim, Kim, & Pantzalis, Reference Kim, Kim and Pantzalis2001): low-low combination (low product and geographic diversification), low-high combination (low product and high geographic diversification), high-low combination (high product and low geographic diversification), and high-high combination (high product and geographic diversification). We argue that foreign subsidiaries in MNEs with low-high combination may outperform those in MNEs with low-low combination because the former is more likely to benefit from economies of scale. Moreover, foreign subsidiaries in MNEs with high-low combination may outperform those in MNEs with high-high combination because the former is more likely to benefit from the strategic flexibility and the latter can face the problem of over-diversification.

To examine the proposed theoretical relationships, we rely on a sample of 422 publicly listed European firms in a longitudinal setting (from 2005 to 2011) in European countries, including transitional (Central and Eastern) European countries, with 20,104 subsidiary-year observations. We use the generalized methods of moments estimation together with a set of simultaneous equation models to estimate the results and rule out endogeneity issues. We find a U-shaped relationship between product diversification and subsidiary performance and geographic diversification moderates the relationship, as predicted. Given the importance of transition economies in international business research, we conducted a subsample test contrasting the results based on the transitional (Central and Eastern) versus Western European countries. While our proposed model remains robust for both subsamples, we also found some interesting patterns regarding their differences. Specifically, subsidiaries that are in or from transition economies reach the bottom of the U-shaped curve at a higher level of product diversification than those in or from Western economies. Further, the benefits of geographic diversification differ for subsidiaries in and from transition versus Western economies.

This study makes an important contribution to the literature on internationalization. Numerous studies have focused on the relationship between international product and/or geographic diversification and MNE performance (for a review, see Hitt, Tihanyi, Miller, & Connelly, Reference Hitt, Tihanyi, Miller and Connelly2006). Our knowledge is limited on the relationship between MNE diversification and subsidiary performance. Subsidiary performance is different from MNE performance because they are at different levels of analysis; and even within the same MNE, subsidiaries may differ in levels of performance. Our study provides additional insights by extending this literature to systematically explore the relationship between MNE product diversification and subsidiary performance under the condition of geographic diversification.

BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES

Corporate Strategy and Subsidiary Benefit

Scholars have argued that strategic and financial controls are associated with the degree of product diversification owing to their different information processing requirements (Baysinger & Hoskisson, Reference Baysinger and Hoskisson1990; Hoskisson, Johnson, & Moesel, Reference Hoskisson, Johnson and Moesel1994). Organizations that pursue low levels of product diversification typically manage information processing with a greater emphasis on strategic controls because subsidiaries share the common business (Geiger & Cashen, Reference Geiger and Cashen2007; Henderson & Fredrickson, Reference Henderson and Fredrickson1996). In contrast, extensive product diversification increases coordination complexity in headquarters, thereby emphasizing financial controls because the governance scope exceeds the managerial capabilities (e.g., information overload) (Geringer, Beamish, & DaCosta, Reference Geringer, Beamish and DaCosta1989; Tallman & Li, Reference Tallman and Li1996). Although firms may use both types of control alternatively to ensure favorable outcomes (Hoskisson, Johnson, & Moesel, Reference Hoskisson, Johnson and Moesel1994), financial controls evaluate and reward subsidiary managers on objective financial criteria, whereas strategic controls focus on the behavior and action of subsidiary managers ‘to achieve competitive advantage in their respective markets’ (Hoskisson & Hitt, 1994: 172).

Research indicates that MNE strategies are likely to affect foreign subsidiaries’ operations (Bartlett & Ghoshal, Reference Bartlett and Ghoshal1989). Product diversification strategies and their corresponding control mechanisms likely affect the way in which subsidiaries benefit from and are constrained by the parent policies. Specifically, in non-diversified firms where practices tend to be standardized, subsidiaries are likely to adopt common templates, procedures, and expectations in operations. The strategic control of parent firms creates conditions to transfer skills and capabilities from headquarters to subsidiaries (Rosenzweig & Singh, Reference Rosenzweig and Singh1991). For instance, Zara, the largest chain owned by Inditex, a Spanish apparel retailer, retained consistent promotion policies and product offerings internationally and used the same business system in all the countries in which it operated. In fact, its corporate managers perceive the role of the corporate center as a ‘strategic controller’ that setting corporate and business strategies and controlling the performance (Ghemawat & Nueno, Reference Ghemawat and Nueno2006). Similarly, during its twenty-five years of successful globalization, Starbuck's strategy was to retain its core services and product offering as much as possible, while adapting to local demands where appropriate (Alkema, Koster, & Williams, Reference Alkema, Koster and Williams2010).

In contrast, financial control in highly product-diversified firms creates conditions whereby subsidiaries are able to gain strategic flexibility with the financial support from the parent. These subsidiaries are likely to adopt effective practices to achieve superior performance while connecting with the parent MNE through financial linkages. Jeffrey Immelt[Footnote 1], the famous veteran chairman and CEO of GE, once stated that ‘[T]he heart of strategy is choices around where you want to play and how you want to win over whatever timeframe is important to you’. According to GE's 2005 annual report, the conglomerate perceived itself as taking the advantage of its enormous size, that is, depth and breadth, to leverage even small ideas to create big financial gains (Bartlett, Reference Bartlett2006). Vivendi SA, the French mass media conglomerate, revitalized itself in 1998 by creating a corporate office that disciplined cash flow of and strengthened headquarter financial control over all its businesses (Montgomery & Turner, Reference Montgomery and Turner1998).

Moreover, we consider the joint effect of product and geographic diversification on subsidiary performance. Although the two types of diversification share many similarities, such as benefits from economies of scale and scope, extension of core competencies, market power, and growth opportunities, as well as accesses to foreign knowledge, resources, and institutions (Hilman, Reference Hilman2015; Hitt et al., Reference Hitt, Hoskisson and Kim1997; Hitt et al., Reference Hitt, Tihanyi, Miller and Connelly2006), the two types of diversification strategies may affect subsidiary performance through different mechanisms. When an MNE is also geographically diversified, according to Kogut's (Reference Kogut1985) study on operating flexibility, being active in multiple countries enables the firm to engage in arbitrage by shifting activities from one country to another. That is, under the assumption that each business can be conducted in multiple countries, geographic diversification increases operational scope and scale (Zahra, Ireland, & Hitt, Reference Zahra, Ireland and Hitt2000), which provides opportunities for arbitrage within a global network (Kogut, Reference Kogut1985). As such, geographic diversification allows firms and their subsidiaries to have the flexibility in operations to exploit intrafirm comparative advantages, including flexible input sourcing, workforce size and skills, plants and equipment, and shifting production across countries (Kogut, Reference Kogut1985; Miller, Reference Miller1992).

The operational flexibility resulting from MNE geographic diversification increases the scope and scale of MNE operations (Goerzen & Beamish, Reference Goerzen and Beamish2003). Subsidiaries in geographically diversified MNEs are more likely to benefit from the flexibility in business operations by helping MNEs realize the arbitrage processes. Building on the MNE network model (Ghoshal & Bartlett, Reference Ghoshal and Bartlett1990), it has been argued that foreign subsidiaries can benefit from the flexibility through internal transactions to manage unfavorable local environments (Chung, Lu, & Beamish, Reference Chung, Lu and Beamish2008; Kogut & Kulatilaka, Reference Kogut and Kulatilaka1994) or to take advantage of the depreciation of local currency (Sundaram & Black, Reference Sundaram and Black1992). For example, foreign subsidiaries may mobilize resources from sister subsidiaries to take advantage of local opportunities (Kogut & Kulatilaka, Reference Kogut and Kulatilaka1994).

MNE Product Diversification and Foreign Subsidiary Performance

Because subsidiaries may benefit from strategic and financial controls of the firm in distinct ways, we propose a U-shaped relationship between product diversification and foreign subsidiary performance. We argue that subsidiaries in a non-product-diversified firm are more effective because they are better able to leverage the parent firm's capabilities, whereas subsidiaries in a highly product-diversified firm have more strategic autonomy and flexibility to adopt effective practices to achieve better performance. Conversely, subsidiaries in a moderately product-diversified firm are less able to achieve better performance because of the conflicting demands from strategic and financial controls. The reasons are as follows.

First, firms with a single business or product often rely on specified knowledge, technology, skill, or capability to enhance performance. The core competences developed in home-country operations can apply to international markets to extend the product life cycle (Bartlett & Ghoshal, Reference Bartlett and Ghoshal1989; Porter, Reference Porter1986). Thus, foreign subsidiaries can benefit from an MNE's core business because knowledge transferred from headquarters can enhance the subsidiaries’ competitive advantage (Fang et al., Reference Fang, Wade, Delios and Beamish2007). However, knowledge transfer is more likely among subsidiaries within the same product line than among those across different product lines (Stern & Henderson, Reference Stern and Henderson2004). That is, firms with low levels of product diversification are more likely to facilitate knowledge transfer to subsidiaries (Sambharya, Reference Sambharya1995) because business similarity between the parent and its subsidiaries enables the leverage of the firm's core competency via effective transfer of practices and technologies. Research shows that knowledge transfer from the MNE enhances subsidiary performance (Chang, Gong, & Peng, Reference Chang, Gong and Peng2012; Fang, Jiang, Makino, & Beamish, Reference Fang, Jiang, Makino and Beamish2010).

Moreover, these subsidiaries are more able to gain support from the headquarters. For example, subsidiary managers in single-business firms are more likely to undertake risky projects because corporate managers understand their strategic proposals (Geiger & Cashen, Reference Geiger and Cashen2007; Hitt et al., Reference Hitt, Hoskisson and Kim1997). Sambharya (Reference Sambharya1995) found that MNEs with a single business strategy often have higher international involvement than those with diversified strategies. For these reasons, subsidiaries in non-product-diversified firms are able to achieve better performance.

Second, highly product-diversified firms tend to ensure greater financial control and thus grant greater strategic flexibility to subsidiary managers to make decisions (Hoskisson & Hitt, 1994). Flexibility refers to ‘the ability of the organization to adapt to substantial, uncertain, and fast-occurring environmental changes that have a meaningful impact on the organization's performance’ (Aaker & Mascarenhas, Reference Aaker and Mascarenhas1984: 74). Foreign subsidiaries, even following an ordained template within a firm, are allowed to have certain competitive differentiation within the ‘range of acceptability’ (Deephouse, Reference Deephouse1999). They may customize a template to enhance their efficiency (Westphal, Gulati, & Shortell, Reference Westphal, Gulati and Shortell1997) or to improve their substantive performance (Heugens & Lander, Reference Heugens and Lander2009). For example, while subsidiaries of the same firm may have adopted a common template, they may attempt to modify or customize the template for their specific needs for certain objectives (Bartlett & Ghoshal, Reference Bartlett and Ghoshal1989; Kostova & Roth, Reference Kostova and Roth2002).

Bartlett and Ghoshal (Reference Bartlett and Ghoshal1989) revealed that structures of subsidiaries in different foreign countries are not homogeneous, because they are able to modify within the range of acceptability to achieve competitive differentiation. It has been acknowledged that with higher levels of product diversification, corporate managers typically are not directly involved in subsidiary strategy-making processes (Michel & Hambrick, Reference Michel and Hambrick1992). Subsidiaries of highly product-diversified firms require different knowledge, product markets, and skilled workers because they have limited commonalities. Strategic flexibility provides subsidiaries with an advantage that enables them to choose effective practices and needed resources (Salomon & Wu, Reference Salomon and Wu2012) or to modify and reconfigure operating routines in pursuit of effectiveness. Thus, subsidiaries of a highly diversified firms are likely to adopt effective practices to improve their performance.

Finally, subsidiary performance can be impaired at the moderate level of product diversification because subsidiaries are less able to benefit from either knowledge transfer or strategic flexibility. There is an important trade-off. Although subsidiaries in single-business firms are less able to gain strategic flexibility, they are more likely to benefit from extending the reach of firm competencies. Product-diversified structure may serve as a barrier to knowledge transfer because of an increased complexity and extra efforts (Björkman, Barner-Rasmussen, & Li, Reference Björkman, Barner-Rasmussen and Li2004; Sambharya, Reference Sambharya1995; Szulanski, Reference Szulanski1996). Thus, when levels of product diversification increase, the subsidiaries’ ability to take advantage of knowledge transfer from headquarters will decrease. As a result, product diversification at the moderate level increases the difficulty for subsidiaries to effectively utilize the transferred knowledge from headquarters because knowledge is often imperfectly mobile to different markets (Fang et al., Reference Fang, Wade, Delios and Beamish2007).

In a highly product-diversified firm, the trade-off in favor of subsidiaries is strategic flexibility, although they are less likely to gain technological support from the parent (Sambharya, Reference Sambharya1995). Subsidiaries in moderately product-diversified firms, as compared to those in highly product-diversified firms, are less able to benefit from such flexibility. According to Lubatkin and Chatterjee (Reference Lubatkin and Chatterjee1994), subsidiaries in moderately product-diversified firms have more opportunities to exploit between-unit synergies than those in single-business firms, but have fewer opportunities to do so than those in highly product-diversified firms. Taken together, subsidiaries in moderately product-diversified firms are stuck in the middle. When the level of MNE product diversification is either high or low, subsidiaries may achieve better performance than when the level of diversification is moderate. We offer the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1:

Foreign subsidiary performance will have a U-shaped relationship with an MNE's product diversification.

Geographic Diversification as a Moderator

Product and geographic diversifications as different MNE strategies may not work in isolation (Geringer et al., Reference Geringer, Beamish and DaCosta1989; Hitt, Hoskisson, & Ireland, Reference Hitt, Hoskisson and Ireland1994). Instead, MNEs may simultaneously seek to balance their growth across both geographic and product scopes (D'Aveni, Reference D'Aveni1989; Seo, Gamache, Devers, & Carpenter, Reference Seo, Gamache, Devers and Carpenter2015). On the one hand, the two diversification strategies may generate a complementarity effect and enhance performance (Chang & Wang, Reference Chang and Wang2007; Hitt et al., Reference Hitt, Hoskisson and Kim1997). On the other hand, the simultaneous presence of high degrees of product and geographical diversifications may stretch firm resources and depress performance (Geringer, Tallman, & Olsen, Reference Geringer, Tallman and Olsen2000; Sambharya, Reference Sambharya1995; Tallman & Li, Reference Tallman and Li1996).

Because the two types of diversification strategies also increase the complexity for subsidiaries to benefit from their parent firms, we argue that these subsidiaries may benefit from two trade-offs: (1) when a firm's low product diversification is coupled with high geographic diversification, or (2) when high product diversification is coupled with low geographic diversification, foreign subsidiaries will perform better. The trade-offs may shift the U-shaped relationship (per Hypothesis 1) in a way as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Demonstration of moderating effect of geographic diversification on product diversification

Regarding the first trade-off, subsidiaries may benefit more from high rather than low levels of geographic diversification because single-business firms have the opportunity to arbitrage across countries by standardizing products and achieve economies of scale. Although single-business subsidiaries in a less geographically diversified firm (i.e., low-low combination) can gain market share and enhance performance through improved identification with their parent firm's brands, capabilities, and technologies, these subsidiaries are less able to benefit from the firm's economies of scale and from exploiting market imperfections (e.g., differences in national resources) under a limited level of geographic diversification.

Relatively, subsidiaries in a geographically diversified firm can benefit more from a concentrated product strategy (i.e., low-high combination) because they can maximize internal support to gain a competitive advantage. The evolutionary path for many MNEs is to expand from one country to another based on their distinct product competencies because single-business firms use their experience to expand into many markets and achieve economies of scale (Sambharya, Reference Sambharya1995). Economies of scale gained through geographic diversification allow subsidiaries to increase efficiency. Subsidiaries can increase sales through an increased usage of existing products by maximizing the firm's product-specific expertise to fit new customers’ needs in the respective host countries (Daniels, Reference Daniels1994; Tallman & Li, Reference Tallman and Li1996). On the one hand, the subsidiaries are able to gain technological and knowledge support from the parent firm because of product concentration. On the other hand, geographically diversified subsidiaries can be equipped with flexibility to incorporate effective local practices (Jensen & Szulanski, Reference Jensen and Szulanski2004; Xu, Pan, & Beamish, Reference Xu, Pan and Beamish2004).

Considering the second trade-off, when firms implement a diversified product strategy, subsidiaries may benefit more from low rather than high levels of geographic diversification (i.e., high-low combination). Specifically, within a limited geographic span, subsidiaries can introduce various products from the parent into the host markets and benefit from organizational synergies. For example, using a sample of 12,992 foreign subsidiaries of Japanese MNEs, Delios, Xu, and Beamish (Reference Delios, Xu and Beamish2008) find that the product diversification of an MNE within each of its host-country markets leads to higher subsidiary performance, because subsidiaries that carry different products in a given foreign market may benefit from shared corporate resources (e.g., corporate image, distribution channels, warehouses, sales forces, etc.) (Daniels, Reference Daniels1994) or exploit interdependencies across nearby business units (Sambharya, Reference Sambharya1995). Thus, low levels of geographic diversification allow highly product-diversified foreign subsidiaries to exploit the strategic flexibility in depth by adopting better practices to improve their respective product sales in certain host-country markets. In contrast, communication and information sharing decreases with geographic distance among sister subsidiaries if the MNE is highly geographically diversified (Von Zedtwitz & Gassmann, Reference Von Zedtwitz and Gassmann2002). Escalating geographic dispersion may increase coordination and transferring costs for highly product-diversified subsidiaries before the advantages of strategic and operational flexibilities and inter-unit synergies can be enjoyed.

When a firm diversifies simultaneously by product and by geography, this dual diversification strategy (i.e., high-high combination) may result in a double-adaptation conflict, that is, concurrent adaptation to different product markets and to different geographic markets for its subsidiaries. However, the concurrent adaptation is difficult to achieve because complexity arises from this situation. Specifically, in highly geographically diversified firms, subsidiaries with different product lines have to develop locally acceptable practices in line with industry norms, which may go beyond their headquarters’ templates (Kristensen & Zeitlin, Reference Kristensen and Zeitlin2005). The benefits of economies of scale by spreading operations multi-nationally are at risk when an MNE adapts its processes of production and marketing to multiple host countries. Therefore, ‘such adaptations will lower potential economies of scale’ (Hennart, Reference Hennart2007: 434). Previous studies have argued that diversification in two disparate directions may deteriorate firm performance because firm resources can be stretched (Geringer et al., Reference Geringer, Tallman and Olsen2000; Sambharya, Reference Sambharya1995; Tallman & Li, Reference Tallman and Li1996). We argue that dual diversification may also reduce the performance of foreign subsidiaries. This is because dual diversification takes the parent firm considerably afield of its established expertise (Daniels, Reference Daniels1994; Sambharya, Reference Sambharya1995), increases the incompatibility of products across product markets in different countries (Rangan, 1998), and goes beyond the range of acceptability since conflicts among different expansion paths may lead to coordination-related distortions and make it difficult to achieve synergies. Therefore, we expect that:

Hypothesis 2:

Geographic diversification will moderate the U-shaped relationship between product diversification and subsidiary performance, such that higher geographic diversification in a less product-diversified firm will lead to better subsidiary performance than lower geographic diversification; in contrast, lower geographic diversification in a highly product-diversified firm will lead to better subsidiary performance than high geographic diversification.

METHODS

Data and Sample

We initially collected all publicly listed firms from the Amadeus database of Bureau van Dijk (BvD), which has been widely used in previous studies (Bode, Wagner, Petersen, & Ellram, Reference Bode, Wagner, Petersen and Ellram2011; Castellucci & Ertug, Reference Castellucci and Ertug2010; Moschieri, Reference Moschieri2011). This database provides two advantages for our data analyses. First, Amadeus provides a standardized and uniform format of financial information of European firms according to the widely accepted European accounting standards (Barone & Cingano, Reference Barone and Cingano2011; Svaleryd & Vlachos, Reference Svaleryd and Vlachos2005); thus, the data can be used for cross-country analysis (Bureau Van Dijk, Reference Bureau Van Dijk2010). Second, Amadeus provides a relatively large and longitudinal sample of firms and their subsidiaries. We cross-validated the data with the Osiris database of BvD, which provides the most accurate and comprehensive consolidated financial information comparable for public companies across countries in the world (Gerstner, König, Enders, & Hambrick, Reference Gerstner, König, Enders and Hambrick2013). The consolidated financial statements reported by Osiris summarize the assets of the parent firm and all of its subsidiaries (both domestic and foreign). We only included firms with precisely the same consolidated amount of assets from both databases to ensure that all subsidiaries in each firm in the collected sample are included in our analyses.

We included subsidiary information from 2005 to 2011 from Amadeus. We lagged our independent variables by one year; hence, our observation window was from 2006 to 2011. Initially, we identified 741 public firms from the Amadeus database; but after matching the data with the Osiris database, we excluded 319 firms because of their incomplete subsidiary information.[Footnote 2] The final sample consisted of 4,918 foreign subsidiaries operating in 32 European countries, with 20,104 subsidiary-year observations. These subsidiaries were established by 422 firms with headquarters based in 25 European countries.

Given the importance of transitional economies in international business, we also performed a subsample test in post hoc analyses for firms based in transitional (Central and Eastern) European countries. In our sample, more than 20% of all parent firms and 40% of all subsidiaries are based in these CEE countries (see Robustness Tests ‘Subsample Analysis of Transitional versus Western European Parent and/or Subsidiaries’ below).

Dependent Variable

Studies using international samples have widely used return on assets (ROA) to measure organizational performance (Wan & Hoskisson, Reference Wan and Hoskisson2003; Zellmer-Bruhn & Gibson, Reference Zellmer-Bruhn and Gibson2006). Consistent with earlier studies (Delios & Beamish, Reference Delios and Beamish2001; Rangan & Sengul, Reference Rangan and Sengul2009), we measured subsidiary performance using subsidiary ROA for each subsidiary-year observation. We also considered alternative measures of subsidiary performance, including return on equity, return on sales, and sales growth (see Robustness Tests ‘Alternative Measures of Subsidiary Performance’). We lagged all time-variant explanatory variables below by one year.

Independent Variable

We calculated MNE product diversification using the entropy measure at the 4-digit level of standard industrial classification (SIC) (Hitt et al., Reference Hitt, Hoskisson and Kim1997) using the following formula:

$$ {\hbox{Product\;diversification}} = \mathop \sum \limits_{\rm i} {\rm P}_{\rm i}{^\ast}\ln \left( {\displaystyle{1 \over {{\rm P}_{\rm i}}}} \right), $$

$$ {\hbox{Product\;diversification}} = \mathop \sum \limits_{\rm i} {\rm P}_{\rm i}{^\ast}\ln \left( {\displaystyle{1 \over {{\rm P}_{\rm i}}}} \right), $$where Pi is the ratio of subsidiary sales of a firm in a 4-digit industry i to the total sales for each year. This measure captures both the number of industries where a firm operates and the relative importance of each industry in total sales (Hitt et al., Reference Hitt, Hoskisson and Kim1997), and varies over time.

Moderating Variable

Consistent with existing studies (Hillman & Wan, Reference Hillman and Wan2005; Hitt et al., Reference Hitt, Hoskisson and Kim1997), we measured geographic diversification using the following entropy measure:

$${\hbox {Geographfic diversification}} = \mathop \sum \limits_{\rm i} {\rm G}_{\rm i}{^\ast}\ln \left( {\displaystyle{1 \over {{\rm G}_{\rm i}}}} \right),$$

$${\hbox {Geographfic diversification}} = \mathop \sum \limits_{\rm i} {\rm G}_{\rm i}{^\ast}\ln \left( {\displaystyle{1 \over {{\rm G}_{\rm i}}}} \right),$$where Gi is the ratio of a firm's sales in country i over the total sales but excluding the sales of the firm's in its home country each year. We considered an alternative measure by using geographic scope (see Robustness Tests ‘Alternative Measure of Geographic Diversification’) and obtained similar results.

Control Variables

We included control variables at the subsidiary, parent, and country levels. At the subsidiary level, we controlled for subsidiary experience, which was measured by the number of years the subsidiary had operated in a host country (Delios & Beamish, Reference Delios and Beamish2001). We also controlled for subsidiary size, measured by the logarithm of the subsidiary's assets, and subsidiary leverage, measured by the subsidiary's debt-to-asset ratio. Finally, we controlled for the subsidiary asset intangibility, measured by the ratio of intangible asset over total asset. At the parent firm level, we controlled for parent firm performance, measured by its return on assets (ROA) (Nell & Ambos, Reference Nell and Ambos2013), to gauge the parent firm's profitability.

At the country level, institutional distance is likely to affect the performance of subsidiaries in foreign countries (Kostova & Zaheer, Reference Kostova and Zaheer1999; Salomon & Wu, Reference Salomon and Wu2012). There are varieties of capitalism, which are the predominant regimes in Europe. Different countries design, revise, and maintain their institutions based on their own culture and economic situations, which exhibit persistent distinctiveness (North, Reference North1990; Williamson, Reference Williamson2000). Therefore, local institutional constraint is presumably important. The gap between home- and host-country institution, or institutional distance, is thus a composite construct that reflects differences in cultural, economic, and regulatory dimensions (Salomon & Wu, Reference Salomon and Wu2012). We thus controlled for institutional distance, relying on the Political Risk Services database (Guillén, Reference Guillén2000) and included all six dimensions from the database: (1) voice and accountability, (2) political stability and absence of violence, (3) government effectiveness, (4) regulatory quality, (5) rule of law, and (6) control of corruption. We used the Euclidean distance to calculate the institutional distance:

$$\eqalign{{{\rm Institutional \;distance}} = \cr & \hskip-110pt\sqrt {\mathop \sum \limits_{\rm i} {\lpar {\hbox{institution index i of host country}}-{\hbox{institution index i of home country}} \rpar }^2},} $$

$$\eqalign{{{\rm Institutional \;distance}} = \cr & \hskip-110pt\sqrt {\mathop \sum \limits_{\rm i} {\lpar {\hbox{institution index i of host country}}-{\hbox{institution index i of home country}} \rpar }^2},} $$where i represents one of the six institutional dimensions. We collected institutional variables from other databases, such as Polity IV, Heritage Foundation, Freedom House, Euromoney, Economic Freedom of the World project and obtained similar results (Guillén, Reference Guillén2000). We also controlled for two characteristics of a host country: first, we included the logarithm of GDP of the host country, which has been conceptualized as a measure for prosperity (Mitra & Golder, Reference Mitra and Golder2002) and for market size of a host country (Grosse & Trevino, Reference Grosse and Trevino1996); second, we included openness of host country, measured by foreign direct investment over GDP (Lu & Ma, Reference Lu and Ma2008).

We also included year-fixed effects to rule out potential temporal impacts on subsidiary performance (Rangan & Sengul, Reference Rangan and Sengul2009), and industry-fixed effects as different industries pose different requirements on subsidiaries to follow the respective industry norms.

Estimation Method

To test our hypotheses, we apply the difference Generalized Methods of Moments (GMM) estimation (Arellano & Bond, Reference Arellano and Bond1991) along with a set of simultaneous equation models (SEMs) following Kumar (Reference Kumar2009) and Mayer, Stadler, and Hautz (Reference Mayer, Stadler and Hautz2015). This approach considers the firm/individual fixed effects that might correlate with variables at the right hand side of the models. More importantly, it allows us to address two critical issues: the causal relationship between product and geographic diversifications that arises from simultaneity, and the reverse causality problem because of the feedback rule, in which subsidiary performance can affect MNE diversification strategy. We first differenced the equation by subtracting the last period value of each variable from its counterpart in the current period.

Because the two diversification measures (product and geographic diversification) might affect each other, we then used the lagged dependent variable and lagged exogenous explanatory variables as instrumental variables for the endogenous variables (i.e., the diversification-related variables and interactions) in the seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) framework (Zellner, Reference Zellner1962). The number of lagged periods can be chosen optimally to obtain the most efficient estimates. Our analyses show that the optimal period is to lag by one year.

The first step of the difference GMM is to obtain the predicted values of the differenced endogenous variables, namely product diversification (PD), geographic diversification (GD), and all interaction terms involving either of the two variables, so that these variables will no longer be endogenous. We regressed any term involving the endogenous variable (PD or GD) to rule out endogeneity and to avoid the forbidden regression (Haans, Pieters, & He, Reference Haans, Pieters and He2016). We then regressed the differenced endogenous variables on the differenced exogenous explanatory variables and non-differenced instrumental variables simultaneously in the SEM. We then adopted the SUR framework (Zellner, Reference Zellner1962) to exploit the correlation of error terms (i.e. ![]() $\varepsilon _{i,t}^{1,1} $,

$\varepsilon _{i,t}^{1,1} $, ![]() $\varepsilon _{i,t}^{1,2} $,…,

$\varepsilon _{i,t}^{1,2} $,…,![]() $\; \varepsilon _{i,t}^{2,1} $,

$\; \varepsilon _{i,t}^{2,1} $, ![]() $\varepsilon _{i,t}^{2,2} $,…) among the equations. The regression will generate the most efficient and consistent estimates for

$\varepsilon _{i,t}^{2,2} $,…) among the equations. The regression will generate the most efficient and consistent estimates for![]() ${\widehat{ \Delta PD_{i,t}}}/{\widehat{ \Delta GD_{i,t}}}$,

${\widehat{ \Delta PD_{i,t}}}/{\widehat{ \Delta GD_{i,t}}}$,![]() ${\widehat{ \Delta PD_{i,t}^2}} /{\widehat{\Delta GD_{i,t}^2}} $, and all interaction terms involving PD/GD, i.e.:

${\widehat{ \Delta PD_{i,t}^2}} /{\widehat{\Delta GD_{i,t}^2}} $, and all interaction terms involving PD/GD, i.e.:

and each interaction term involving PD, in equation (1-3), (1-4), …respectively

and each interaction term involving GD, in equation (2-3), (2-4)…, respectively.

where Δcontrols i,t-1 are exogenous predictors including Δsubsidiary size i,t-1, Δsubsidiary age i,t-1, Δsubsidiary intangibility i,t-1, Δparent firm performance i,t-1, Δlogarithm of host country GDP i,t-1 and Δhost country openness i,t-1; instrumental variables include Δsubsidiary performance i,t-2, subsidiary experience i,t-2, subsidiary size i,t-2, subsidiary age i,t-2, subsidiary intangibility i,t-2, parent firm performance i,t-2, institutional distance i,t-2, logarithm of host country GDP i,t-2, Δhost country openness i,t-2, and their lagged terms.

After we obtained the predicted values of the variables related to product and geographic diversifications from the SEMs, we estimated our final model by regressing the performance on the predicted values of endogenous variables and exogenous explanatory variables while considered the heteroscedasticity, i.e. using Generalized Least Squares (GLS):

$$\hskip-9pc \eqalign{ subsidiary\; performance_{i,t} = g\lpar {{\widehat{\Delta PD_{i,t-1}}},\; {\widehat{\Delta GD_{i,t-1}}},{\widehat{\Delta PD_{i,t-1}^2}}}, \cr\; {{\widehat{\Delta GD_{i,t-1}^2}}, \; \Delta moderators_{i,t-1},\; \Delta controls_{i,t-1}} \rpar $$

$$\hskip-9pc \eqalign{ subsidiary\; performance_{i,t} = g\lpar {{\widehat{\Delta PD_{i,t-1}}},\; {\widehat{\Delta GD_{i,t-1}}},{\widehat{\Delta PD_{i,t-1}^2}}}, \cr\; {{\widehat{\Delta GD_{i,t-1}^2}}, \; \Delta moderators_{i,t-1},\; \Delta controls_{i,t-1}} \rpar $$ The coefficient estimates of interests are those on ![]() ${\widehat{\Delta PD_{i,t-1}}}$,

${\widehat{\Delta PD_{i,t-1}}}$,![]() $ {\widehat{\Delta PD_{i,t-1}^2}} \; $, and their respective interaction terms, as well as on

$ {\widehat{\Delta PD_{i,t-1}^2}} \; $, and their respective interaction terms, as well as on ![]() ${\widehat{\Delta GD_{i,t-1}}}$,

${\widehat{\Delta GD_{i,t-1}}}$,![]() ${\widehat{\Delta GD_{i,t-1}^2}} $, and their respective interaction terms.

${\widehat{\Delta GD_{i,t-1}^2}} $, and their respective interaction terms.

We conducted further tests to ascertain the validity of the GMM estimation (Durand & Jourdan, Reference Durand and Jourdan2012). Since we used the instrumental variable estimation in a general way, some common problems associated with the approach remain. These problems include: (1) instrumental variables have to be time-variant in our panel data; (2) the exogeneity of the instrumental variables, i.e. the instrumental variables should be uncorrelated with the residual; (3) the exclusion restrictions, i.e. the instrumental variables should not enter the model directly; (4) the strength of instrumental variables, i.e., the correlation of instrumental variables and the endogenous variables should be high enough (Stock & Yogo, Reference Stock, Yogo, Andrews and Stock2005); (5) the overidentification restriction, namely, there might be too many instrumental variables (Hansen & Singleton, Reference Hansen and Singleton1982); and (6) the error terms are not autocorrelated, otherwise the instrumental variables will become endogenous and invalid, as indicated by Arellano and Bond (Reference Arellano and Bond1991).

GMM framework can address problems (1), (2), and (3) (Blundell & Bond, Reference Blundell and Bond1998). We conducted the first stage F-tests and Wald test for the strength of instrumental variables for each potential endogenous variable, i.e. the variables related with product and geographic diversifications. The first stage F-statistics are well above the 10% maximum bias (Stock & Yogo, Reference Stock, Yogo, Andrews and Stock2005), indicating that our estimations meet the requirement of problem (4). We also conducted Sargan's test (Hansen & Singleton, Reference Hansen and Singleton1982), and found no evidence for overidentification. Thus, our estimations also resolve problem (5). Finally, the Arellano-Bond serial correlation test suggests that our inclusion of first order lagged dependent variable was appropriate, since the first-order autocorrelation – AR(1)– is significant but AR(2) is insignificant, as reported in Tables 2, 3, and 4.

Finally, we adopted the classical way of using GMM, i.e. including the lagged dependent variable in the model as a robustness check. The results remain consistent.

RESULTS

Main Results

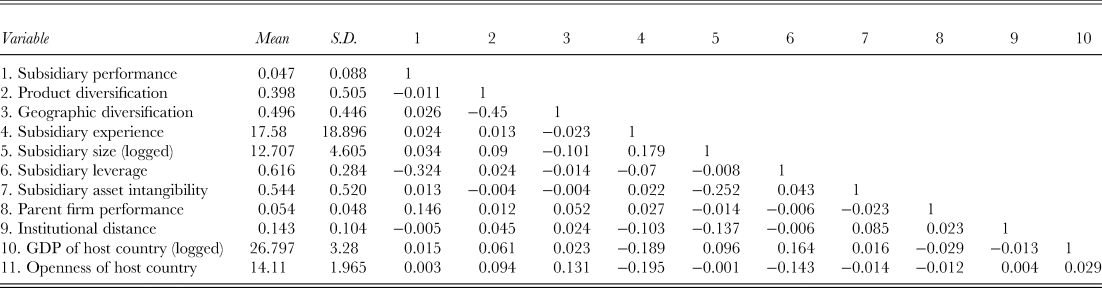

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics and correlations for all variables in this study. The correlations show no significant concern of multicollinearity as the largest correlation is below 0.3. Variance inflation factor (VIF) tests also indicate no multicollinearity problem, given that the largest VIF is 2.423, which is below the traditional threshold of 10.0, and the mean of 1.840 is below the threshold of 2.5 (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, Reference Cohen, Cohen, West and Aiken2003).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix

Note: Correlations with absolute value that exceeds 0.01 is significant at the 5% level.

Table 2 presents the results of the difference GMM method. Model 1 includes only the control variables. Model 2 adds the independent variable and its quadratic term. Model 3 tests the moderating effect of geographic diversification. The predicted results are consistent across all models. Among the significant controls, subsidiary size, subsidiary intangibility, parent firm performance, GDP of host country, and openness of host country have positive effects, whereas subsidiary leverage has a negative effect on subsidiary performance. These findings are in line with our expectation.

Table 2. Results of the difference GMM and SEM estimations (dependent variable: Subsidiary Performance)

Notes: Standard errors are in parentheses. N = 20,104. * p < 0.10; ** p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01. All time-varying explanatory variables were lagged by one year. Adjusted R2 is less interpretive in GMM models.

Hypothesis 1 predicts a U-shaped relationship between MNE product diversification and subsidiary performance. In Model 2, the coefficient estimates on both linear (β = −0.133, p < 0.01) and quadratic (β = 0.157, p < 0.01) terms are significant with expected signs. The lowest point occurs at a moderate level of product diversification, -0.133/(-2×0.157)≈0.424, around the mean of 0.398 and the median of 0.496. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is supported. Meanwhile, before the inflection point 0.424, a one standard deviation increases in MNE product diversification (0.505) on average decreases subsidiary performance by 0.036, which is 76.1% of the mean value of subsidiary performance, while one standard deviation increases in MNE product diversification after the inflection point increase subsidiary performance on average by 0.056 or 118.2% of the mean value of performance. The effects are economically significant. However, given that we are discussing a curvilinear effect, our effect sizes are mostly point estimation results rather than the shape of the curve itself and that our effect sizes could be overestimated. Robustness test in the section of ‘Robustness of the U-shaped Curve and Its Moderation’ shows further results in detail.

Hypothesis 2 states that in a less geographically diversified firm, high product diversification leads to better subsidiary performance than low product diversification does, and that in a more geographically diversified firm, low product diversification leads to better subsidiary performance than high product diversification does. In Model 3, the coefficient of the interaction term between product and geographic diversification is negative and significant (β = −0.050, p < 0.01), whereas the coefficient of the interaction term of the square of product and geographic diversification is positive and significant (β = 0.003, p < 0.01). Meanwhile, at the low level of geographical diversification (one standard deviation below the mean, 0.050), a one standard deviation increases in product diversification on average leads to 0.054 or 113.9% of the mean subsidiary performance. On the other hand, at the high level of geographical diversification (one standard deviation above the mean, 0.942), a one standard deviation increases in product diversification on average leads to 0.109 less or 231.8% of the mean subsidiary performance. The effects are economically significant. These results were plotted in Figure 2, supporting Hypothesis 2. That is, subsidiaries achieve better performance when low product diversification is combined with high geographic diversification, and when high product diversification is combined with low geographic diversification.

Figure 2. Moderating effect of geographic diversification on product diversification

Robustness Tests

Subsample analysis of transitional versus Western European parent and/or subsidiaries

Firms in the transitional and Western Europe are different in terms of their institutional development, economic progress, and infrastructure, following the East-West split that had lasted more than four decades. Studies found that Central and Eastern European firms still exhibited attitudes and tendencies that were at odds with market practices (Shinkle & Kriauciunas, Reference Shinkle and Kriauciunas2012; Shinkle & McCann, Reference Shinkle and McCann2014; Steensma & Lyles, Reference Steensma and Lyles2000). More importantly, Central and Eastern European countries as transitioning markets deserve academic efforts to compare and contrast with the Western European firms (Hoskisson, Eden, Lau, & Wright, Reference Hoskisson, Eden, Lau and Wright2000). Our sample consists of eight out of twenty-five home countries located in Central and Eastern Europe: Bulgaria, Estonia, Croatia, Hungary, Macedonia, Poland, Russian Federation, and Slovakia, and sixteen out of thirty-two host countries located in Central and Eastern Europe: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Czech, Estonia, Croatia, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia, Macedonia, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Russian Federation, Slovenia, Slovakia, and Ukraine.

We presented subsample results based on whether the parent firm's home country is in transitional or Western Europe (Panel A of Table 3) and whether the subsidiary's host country is in transitional or Western Europe (Panel B of Table 3). By contrasting the results of transitional and Western European firms (either parent or subsidiary), we can see that Central and Eastern European firms (1) approach its lowest point faster and thus suggest that the conflict between internal consistency and local adaptation is more intensive; (2) have less positive impact of geographic diversification on subsidiary performance; and (3) the moderating effect of geographic diversification on the product diversification (shifting the lowest point to the right) is weaker.

Table 3. Subsample analyses based on home and host countries’ location (transitional vs. Western Europe) by difference GMM with SEM

Notes: Standard errors are in parentheses. * p < 0.10; ** p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01. All time-varying explanatory variables were lagged by one year. Controls are the same as Table 2. Adjusted R2 is less interpretive in GMM models.

Taken together, these results suggest that Central and Eastern European firms are weaker than their Western counterparts in terms of accommodating the dual logics – home or host – in business, and that the geographic spillover effect is weaker in Central and Eastern European firms. The differences may be attributed to the reason that Central and Eastern European firms still need time to figure out appropriate business models to deal with the conflict between internal consistency and local adaptation, and that they need to accumulate knowledge and skills to capture the benefits of geographic diversification.

Robustness of the U-shaped curve and its moderating effects

Following the suggestion by Haans et al. (Reference Haans, Pieters and He2016), we follow the three steps described by Lind and Mehlum (Reference Lind and Mehlum2010) to check the robustness of the U-shaped curve using the full model. In addition to the significant quadratic term of product diversification, we find that the slopes at the two ends of product diversification are positive and negative respectively, indicating that the slopes are steep enough for the U-shaped curve. Moreover, the turning point (0.424) falls within the data range, and is proximate to the mean of 0.398 and the median of 0.496. The value also falls within the range of one standard deviation around the mean. We then applied the confidence intervals test developed by both Fieller (Reference Fieller1954) and Rao (Reference Rao2009), and verified that both the minimum and maximum values of product diversification are outside the 95% confidence interval of the turning point.

To examine whether the relationship between subsidiary performance and firm product diversification is U-shaped or S-shaped, we added the cubic term of product diversification to the full model in Table 4. The result shows that the cubic term is not significant (β = 0.005, p > 0.10). Thus, we confirm the U-shaped rather than S-shaped relationship.

Table 4. Robustness of U-shaped curve and its moderating effects by difference GMM with SEM (dependent variable: Subsidiary Performance)

Notes: Standard errors are in parentheses. N = 20,104. * p < 0.10; ** p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01. All time-varying explanatory variables were lagged by one year. † Semiparametric (partial linear model) results are based on marginal effects. Adjusted R2 is less interpretive in GMM models.

Columns 2 and 3 in Table 4 used logarithm and exponential transformations[Footnote 3] of product diversification, respectively. The results show that the explanatory power of the two models in terms of their R-squared values declines substantially. Column 2 shows that the coefficient estimate on the logarithm of product diversification is not significant (β = 0.005, p > 0.10), nor is significant for its interaction terms. Thus, the U-shaped curve doesn't show a logarithmic relationship (Haans et al., Reference Haans, Pieters and He2016). Similarly, Column 3 shows that none of the variables involving product diversification is significant (β = 0.003, p > 0.10), indicating that the exponential transformation is not appropriate (Haans et al., Reference Haans, Pieters and He2016).

In Columns 4 and 5, we split the sample in terms of the turning point of 0.424. For the subsample with product diversification smaller than the turning point, the effect of product diversification on subsidiary performance is negative (β = −0.172, p < 0.01), whereas the effect turns positive (β = 0.149, p < 0.01) when product diversification is larger than the turning point. This result further verifies the proposed U-shaped relationship. Moreover, we find that the moderating effect of geographic diversification on product diversification is positive (β = 0.082, p < 0.01) in Column 4 and negative (β = −0.158, p < 0.01) in Column 5. This finding provides further support for Hypothesis 2.

Column 6 in Table 4 reports the results from a semiparametric estimation (Ai & Chen, Reference Ai and Chen2013; Imbs & Wacziarg, Reference Imbs and Wacziarg2003). We adopted the semiparametric example developed by Ai and Chen (Reference Ai and Chen2013) and used a partial linear regression with an endogenous nonparametric part (i.e., product and geographic diversifications and their corresponding interactions). The endogenous nonparametric part is in form of an unknown function linking variables related to either product or geographic diversification to the subsidiary performance, while the other variables are linearly correlated with subsidiary performance. Column 6 reports the marginal effects of all variables (for variables involving product diversification, we calculated the marginal effects from the unknown function; while for variables other than those related to product diversification, the marginal effects are the same as the coefficients). The results are consistent with those shown in Table 2.

In Column 7 in Table 4, we adopted the dummy variable approach (Haans et al., Reference Haans, Pieters and He2016). We assigned dummies according to different intervals or quintiles (0~20%, 20~40%. 60~80% and 80%~100%, while 40~60% serve as baseline) of product diversification. The results are consistent with those reported in Table 2. In Column 7, the first two dummies are negative and significant, whereas the last two are positive and significant, supporting the U-shaped effect of product diversification. Hypothesis 2 is also supported given that the interaction terms between low product diversification and geographic diversification are positive, and that those between high product diversification and geographic diversification are negative.

Alternative estimation approach: Multilevel modeling

Given the nested structure of our data, which included subsidiary-, parent-, and country-level variables, multilevel modeling may be appropriate to estimate the model (Hillman & Wan, Reference Hillman and Wan2005). Multilevel modeling considers the variation within each hierarchy level, thereby serving as an alternative modeling approach to panel data estimation (Kreft, Kreft, & de Leeuw, Reference Kreft, Kreft and de Leeuw1998). Following Hillman and Wan (Reference Hillman and Wan2005), we used a two-level (rather than three-level) hierarchical structure for modeling because subsidiaries are cross-classified by both parent firm and host country. Each subsidiary exclusively belongs to one parent firm and one host country. To account for the fixed effects, we used STATA to fit the generalized linear models with multilevel mixed-effects. We included random intercepts of both parent firm and host country. Considering the home – host country differences, three-level hierarchical estimation may also be appropriate. Thus, we extended the model to nest the parent firm into the home – host country pair. The results are similar as those reported in Table 2.

Alternative measures of subsidiary performance

We further checked the robustness by using alternative measures of subsidiary performance, including return on equity, return on sales, and sales growth (Giannetti, Liao, & Yu, Reference Giannetti, Liao and Yu2015). We removed the observations with negative values of equity, which comprise 0.14% of our sample (28 in total). The results remain consistent with those reported in Table 2.

Alternative measure of geographic diversification

We used geographic scope (the number of host countries that a firm's subsidiaries are operating in) as an alternative measure of geographic diversification (David, O'Brien, Yoshikawa, & Delios, Reference David, O'Brien, Yoshikawa and Delios2010; Hitt et al., Reference Hitt, Hoskisson and Kim1997). The results remain consistent with those in Table 2.

The balanced panel data result

There might be pick-up effect of new entrants: subsidiaries that entered a host country later may be different from existing ones in multiple aspects. We thus focused on subsidiaries that were in operation throughout the sample period (2005–2011), i.e. a subsample of balanced panel, for further investigation. The results still fall in line with those reported in Table 2.

DISCUSSION

We have examined how MNE strategies may affect subsidiary performance, an issue largely overlooked in the literature on diversification. The results show that MNE product diversification has a U-shaped relationship with subsidiary performance. Moreover, subsidiary performance may benefit from the trade-offs between product and geographic diversifications. That is, foreign subsidiaries in MNEs with low-high combination outperform those in MNEs with low-low combination. Moreover, foreign subsidiaries in MNEs with high-low combination outperform those in MNEs with high-high combination.

Theoretical Implications

We extend the diversification literature (Hilman, Reference Hilman2015; Wiersema & Bowen, Reference Wiersema and Bowen2011), which has traditionally focused on the firm's perspective (Hitt et al., Reference Hitt, Tihanyi, Miller and Connelly2006; Palich, Cardinal, & Miller, Reference Palich, Cardinal and Miller2000), by drawing attention to the subsidiary's perspective. Scholars have largely focused on whether the effects of product and geographic diversifications on performance are linear or curvilinear, and the results are mixed in the literature (Palich et al., Reference Palich, Cardinal and Miller2000; Tallman & Li, Reference Tallman and Li1996). It is well acknowledged that as the level of product diversification increases, firms shift from an emphasis on strategic controls to an emphasis on financial controls due to information overload problems and inability to adequately understand the operations of each subsidiary (Baysinger & Hoskisson, 1989; Hill & Hoskisson, 1987; Hitt et al., Reference Hitt, Hoskisson and Ireland1994). From the subsidiary's perspective, foreign subsidiaries may benefit from knowledge transfer in a non-product-diversified multinational firm and from strategic flexibility in a highly product-diversified firm to enhance their performance. We identify knowledge transfer and strategic flexibility as two mechanisms for our theoretical development.

Our finding on the U-shaped relationship between product diversification and subsidiary performance adds to the literature on the relationship between headquarters and subsidiaries by revealing the benefit of subsidiaries from different corporate strategies. Previous studies have focused on the relationship between firm entry strategies and subsidiary performance (e.g., Anand & Delios, Reference Anand and Delios1997; Delios & Beamish, Reference Delios and Beamish2001; Woodcock, Beamish, & Makino, Reference Woodcock, Beamish and Makino1994). We show that diversification as another type of corporate strategy also affects subsidiary performance. Specifically, subsidiaries in non-product-diversified firms are better able to gain access to critical firm resources (e.g., brands, operation experience, and technological support) from the parent and to leverage the transferred knowledge to enhance performance (Fang et al., Reference Fang, Wade, Delios and Beamish2007). Moreover, subsidiaries in highly product-diversified firms are likely to enhance performance, because they enjoy increased autonomy and flexibility to adopt effective practices. Hillman and Wan (Reference Hillman and Wan2005) found that subsidiaries in diversified firms were more likely to engage in political strategies to safeguard their economic interests in host countries because they have the autonomy to adopt competitive practices. In contrast, at the moderate level of MNE product diversification, subsidiary performance may suffer because imported firm-specific advantage cannot be effectively leveraged on the one hand (Rodgers & Wong, Reference Rodgers and Wong1996; Zaheer, Reference Zaheer1995) and because they are unable to gain full strategic flexibility on the other hand.

More importantly, we address the benefit of subsidiaries from the trade-offs that MNEs make across product and geographic markets. Previous studies have examined the interactive (complementary or conflicting) effects of industrial and geographic diversification on firm performance (Denis, Denis, & Yost, Reference Denis, Denis and Yost2002; Hitt et al., Reference Hitt, Hoskisson and Kim1997; Sambharya, Reference Sambharya1995; Vachani, Reference Vachani1991). However, little theoretical work has linked the interaction of these two strategies to subsidiary performance. Extending this line of inquiry, we show that subsidiaries may achieve better performance only when low product diversification is coupled with high geographic diversification, or when high product diversification is joined with low geographic diversification. The implication is that subsidiaries in over- or under-diversified firms (in terms of both product and geography) have considerable difficulties in enhancing their performance than subsidiaries in firms that pursue either product or geographic diversification strategy. The reason is that subsidiaries in under-diversified firms are less likely to benefit from economies of scale and scope, and that subsidiaries in over-diversified firms are challenged in connecting or coordinating efforts. Thus, our findings provide guidance that may benefit firms to choose diversification paths and balance different types of diversification to augment subsidiary performance.

Implications for MNEs in Transition Economies

Given that our findings are generalizable to MNEs from transition economies based on the subsample test, our theory has important implications for MNEs from other transition economies, especially those from China, by far the largest transition economy worldwide. First, MNEs from China share many similarities (e.g., firm capabilities, strategies, and policy constraints) with those from Central and Eastern European countries (Wright, Filatotchev, Hoskisson, & Peng, Reference Wright, Filatotchev, Hoskisson and Peng2005). Chinese MNEs have made significant efforts to expand globally and are likely to continue this trend under the Belt and Road Initiative since 2013. Despite these efforts, Chinese managers may not fully understand the relationship between international diversification and subsidiarity performance given their relatively short history in the global market. According to our findings, Chinese MNEs should be cautious about the potential downside in product diversification strategy abroad in the short run. Our study shows that a diversified product portfolio of the parent firm may hurt its foreign subsidiaries’ financial performance at the initial stage. However, this downward effect will be reverted once the level of product diversification exceeds some threshold, beyond which MNEs’ product diversification strategy will create a positive impact on their foreign subsidiaries.

Furthermore, our findings about the joined effect of product and geographic diversification provide implications for Chinese MNEs to enhance the performance of their foreign subsidiaries. Like firms from Central and Eastern European countries, Chinese firms are also likely to fall short in managerial resources and capabilities that allow them to compete in foreign markets efficiently and effectively (Peng, Reference Peng2012). Therefore, Chinese MNEs should be aware of the trade-off between product and geographic diversifications during global expansion or along the map of Belt and Road. Our theory suggests that firms may become over-stretched when managing product and geographic diversification simultaneously. This scenario is likely to be exacerbated for MNEs from transition economies, which are typically characterized by constrained managerial resources and less efficient corporate governance (Hoskisson, Wright, Filatotchev, & Peng, Reference Hoskisson, Wright, Filatotchev and Peng2013). In sum, our findings presented above about MNEs from Central and Eastern European countries lend useful implications for MNEs from other transition economies, in particular China.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study has several limitations that may provide opportunities for future research. First, our study emphasizes the importance of MNE strategies in affecting performance at the subsidiary level. However, strategies at the subsidiary level may also affect subsidiary performance. We were unable to compare and contrast the different influences of MNE and subsidiary diversification strategies on subsidiary performance, because diversification information for subsidiaries in different countries is unavailable in secondary sources. However, this can be an important direction for future research.

Second, our longitudinal data were limited by publicly available databases. Thus, we lack specific information on the motives of subsidiaries regarding the mechanisms of product diversification, such as knowledge transfer for non-product-diversified MNEs and strategic flexibility for highly product-diversified MNEs. Future research may develop surveys or case studies that may complement our research for a finer-grained and more nuanced understanding of different benefits and open the black box involving the control mechanisms.

Third, because we are only able to trace subsidiaries of parent firms to calculate diversifications in Europe from the BvD database, this data limitation may confine the generalizability of our findings. Future research may collect data in a worldwide scope or focus on other regions beyond the European countries. This effort will contribute to a more complete understanding about the importance of corporate diversification on subsidiary performance.

Finally, given the trend of increasingly diversifying abroad by MNEs based in emerging economies, it is useful to examine whether our theoretical framework apply to these MNEs. MNEs from emerging economies are different from those from developed economies because the former may have different motives and locational choices than the latter. Thus, it is an important topic for future research to explore how corporate diversification strategies of MNEs from emerging economies affect the performance of their foreign subsidiaries.

CONCLUSION

Despite these caveats, our study has made an important first step to understand the joint effect of product and geographic diversifications on their foreign subsidiary performance. Future research may extend this line of inquiry in at least the following directions. First, our discussion has mostly focused on knowledge transfer that happens along the MNE-subsidiary link. However, within an MNE, foreign subsidiaries may share and learn about each other's practices through formal (e.g. corporate conference or training sessions) or informal (e.g., personal connections or job rotations) means. Shared experience and knowledge at the subsidiary level may provide feedbacks to enhance foreign subsidiary performance.

Second, our study highlights the benefit of geographic diversification as a result of economies of scale. The scale economy logic draws upon the assumption that production functions in each country are largely similar, so that operations in multiple countries help amortize the fixed cost (Hennart, Reference Hennart2007). Whereas our moderating effect of geographic diversification has taken into account the validity of this assumption, we believe that further analysis should dissect specifically how MNE production functions vary across countries. Such analysis will contribute to the current understanding about both MNEs and scale economy.

Finally, we take into consideration the institutional distance between an MNE and its host countries as a factor that influences foreign subsidiary performance in respective host countries. We duly acknowledge that in fact institutional distance is a multi-dimensional construct, consisting of aspects like cultural, economic, regulatory, administrative, demographic, knowledge, and political distance (Berry et al., 2010; Salomon & Wu, Reference Salomon and Wu2012). Therefore, future studies should look into various dimensions of distance across geographic regions, and investigate their independent and joint effects on MNEs’ subsidiary performance.