For at least 35 years, US politicians and pundits have scared the public with tales of declining vitality in US manufacturing, from Trump tweeting that ‘China is stealing our jobs’Footnote [1] to a recent article by a ranking congressman that claimed that ‘America has lost its competitive manufacturing edge and the jobs that go with it’ (Yoho, Reference Yoho2019). Such assertions are questionable at best, and bunk at worst. Economic data do not support the claim of a decline in US manufacturing vitality or that globalization and offshoring are the main culprits. The US remains a dynamic, innovative, manufacturing nation, with productivity (in terms of output per worker) way ahead of any other nation. Moreover, until 2011, the US was the biggest manufacturing country on the planet (by total value of manufacturing output) and even in 2018/19, the US remained a close second, with $1867 billion in manufacturing output, compared with China's $2,010 billion. Figure 1 shows the US output index in current dollars at a record high until 2019.Footnote [2]

Figure 1. US manufacturing current dollars output (Index 2012 = 100)

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

It is true, however, that the number of jobs in US manufacturing declined from a peak of near 20 million in 1979 to below 12 million in 2010 (recovering a bit to over 13 million workers in 2019). See Figure 2. The physical evidence is not hard to miss in the US ‘rust belt’ states, where hulks of abandoned factories blight the landscape. The around seven or eight million reduction in total manufacturing workers was accompanied by a downward squeeze on wages. Laid-off workers found other jobs, but at significantly lower pay. Diseases of despair such as addictions and suicides rocketed in the post-2008 period. By 2015, the ‘American Dream’, which for two centuries suggested that children would be better off than their parents, came to a crashing halt. By 2015, Pew Research found that ‘Just 37% of Americans believe(d) that today's children will grow up to be better off financially than their parents’ (Stokes, Reference Stokes2017). The disaffected then voted for nativist candidates like Trump who laid the blame entirely on globalization, particularly targeting China.

Figure 2. Employment numbers in US manufacturing

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

BUT ARE GLOBALIZATION AND OFFSHORING THE REAL CULPRIT?

No. Globalized competition has indeed been responsible for some fraction of US job losses (in both manufacturing and services) and the angst that caused in parts of the US and Europe. But the seeming contradiction between the historically highest dollar value of US manufacturing output (Figure 1) and a workforce that had sunk to below 12 million workers by 2015 (Figure 2) can be explained by the increase in automation and robotics, as well as Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) that enable more output with fewer workers – in short, enhanced productivity (Baily & Bosworth, Reference Baily and Bosworth2014).

When a company faces downward price pressure from its competitors, eventually it must do something to cut costs in one of four ways: (i) offshore its production to lower-wage countries, and/or (ii) automate its equipment, thereby reducing the workers needed, but making the surviving workforce more productive in terms of output per worker, and/or (iii) computerize and digitize its processes, and/or (iv) cut workers’ wages (Goos, Manning, & Salomons, Reference Goos, Manning and Salomons2014; Hawksworth, Berriman, & Goel, Reference Hawksworth, Berriman and Goel2018). Offshoring is only one factor, besides the others (a) automation, (b) ICT, and (c) the shrunken bargaining power of labor versus management and shareholders, that jointly explain the transformation in US manufacturing.

The principal explanation for the phenomenon (seen in Figure 2) whereby the number of jobs in US manufacturing has declined (since the 1950s), while at the same time output has increased, is likely to be automation (including robotics and ICT). Tellingly, the share of manufacturing employment in all (non-farm) employment – the red line in Figure 2 – has been on an inexorable decline since the 1940s, when globalization was only a glimmer in the futurist's eye. Hence globalization could hardly have been a strong causal factor until perhaps the 1990s or 2001 when China joined the WTO.

In terms of output, US manufacturing remains an important part of the economy. According to Ramaswamy et al. (Reference Ramaswamy, Manyika, Pinkus, George, Law, Gambell and Serafino2017), manufacturing accounts for 70 percent of US R&D, 60 percent of exports, and 55 percent of patents. But because of the faster growth of the services sector in GDP, manufacturing contributes towards only 12 percent of US GDP and only 9 percent of employment in 2020.

As Autor, Dorn, and Hanson (Reference Autor, Dorn and Hanson2015), Jaimovich and Siu (Reference Jaimovich and Siu2019), and Michaels, Natraj, and Van Reenen (Reference Michaels, Natraj and Van Reenen2014) indicate, it is very difficult to disentangle the causal effects of globalization from the effects of automation and ICT. In fact, some of the findings imply a larger causal role of automation and IT. Moreover, I propose later below another underlying factor – the declining power of unions in the US and the consequent shrinkage in manufacturing wages.

HYPOTHESIS

Productivity (Aided by Automation and ICT) Are Dominant Explanations (Compared to Offshoring)

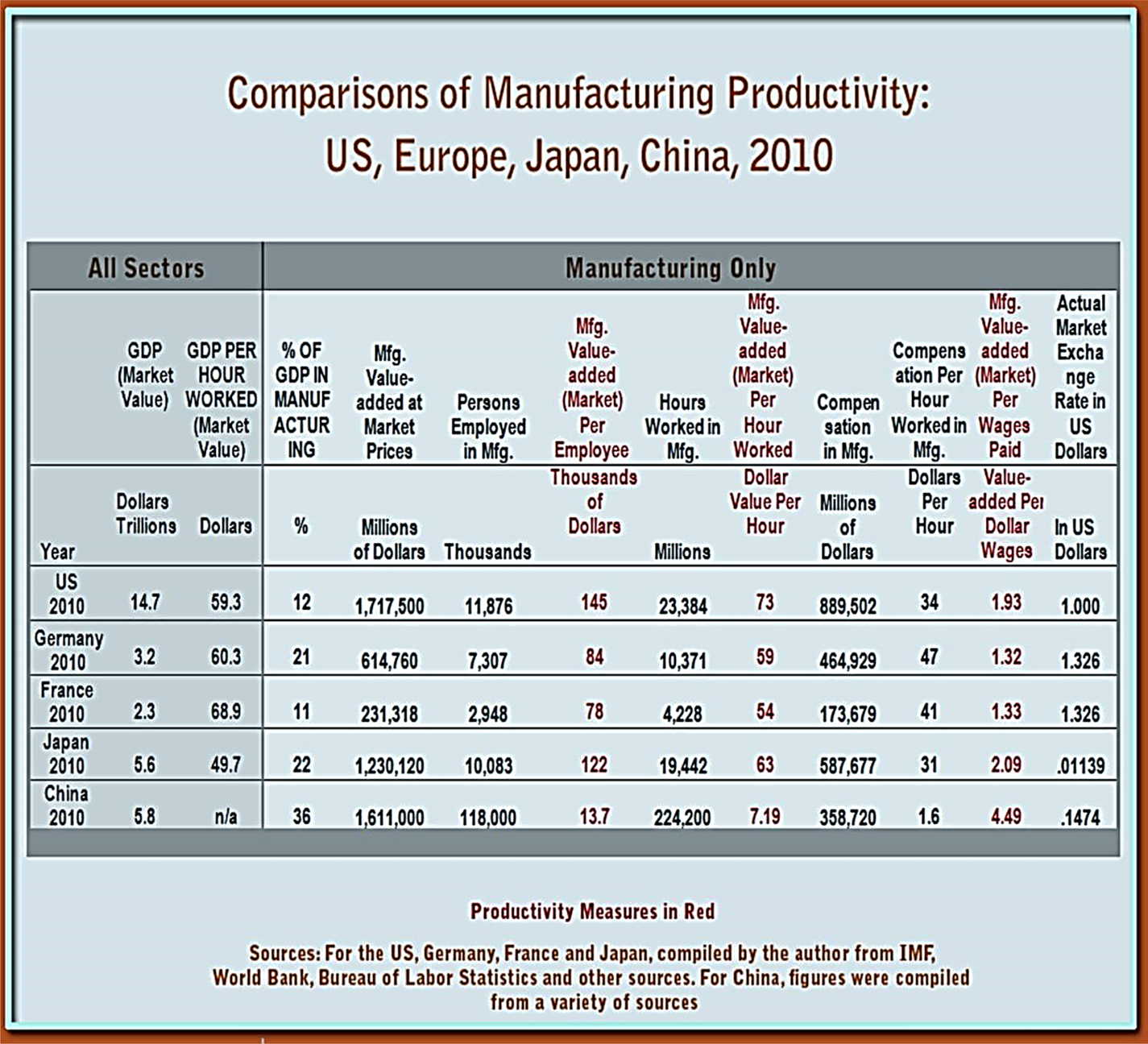

A comparison I did a few years ago,Footnote [3] (see Figure 3) puts the US way ahead of any other nation in terms of productivity measures: ‘$ Output per employee per year’, as well as ‘$ Value Added per employee per hour’. Not much has changed since then in terms of a comparison across the selected countries. US manufacturing should remain the envy of the world today. Alas, unrivalled productivity is the result of the casual willingness of US companies to replace a worker with a robot or new equipment, which means (i) layoffs of unskilled workers and (ii) to some extent higher wages for the fewer surviving skilled workers who, being better paid than their laid-off brethren, increase income inequality.

Figure 3. Productivity in the US versus other countries

Source: Contractor, Reference Contractor2012

Incidentally, in Figure 3 we see China coming out on top in one productivity measure, the ratio of $ value added per worker divided by the $ wages paid. But that is because the denominator – Chinese wages – was so lowFootnote [4] compared to US and European wages – labor supply in China being 118 million manufacturing workers, compared to only 11.9 million in the US.

REDUCED BARGAINING POWER OF US WORKERS

There is no law of economics or management that determines what share of a company's profits should accrue to workers, versus management, versus shareholders. That is a function of unionization and bargaining strength.

There are five claimants to a company's profits: (1) The government (taxes), (2) Shareholders, (3) Management, (4) Workers, and (5) Society. While (1) above is an exogenous variable, the distribution of after-tax profits accruing to (2), (3), (4), and (5) is indeterminate, and is an internal decision made by upper management, which reports suggest has been paying itself and shareholders more, to the detriment of the share of the pie captured by workers.

Union membership in the US economy has sunk from 32 percent of the workforce in 1950 to around 10 percent in 2020 (see Figure 4), with an accompanying reduction in bargaining power, although companies are more profitable. There are no counterfactual studies of how much greater the share of the labor force in after-tax profits would have been were its bargaining power not beaten down, particularly over the last four decades.

Figure 4. Percentage of US workers who are members of unions

CONCLUSIONS AND FODDER FOR FURTHER RESEARCH

There is nothing wrong with US manufacturing, which was at record output levels until January 2020, and remains vital, innovative, and the most productive (output-per-worker) in the world. But in other ways, the US economy and its politics have gone through some wrenching transformations, such as the decline in manufacturing jobs and the depressed earnings of the bottom half of the workforce. Politicians, and the public that ‘follows’ them, have seized upon globalization – specifically, the offshoring of work to low-wage nations like China – as the chief culprit. Here I offer alternative explanations, namely the likely larger role in job displacement played by automation, robotics, and information technology.

But in my view, all of these are not causes or explanations, but rather only the visible symptoms of an even deeper underlying root cause, namely hypercompetition (as seen in Figure 5). In considerable part, competition results in downward price pressures. In turn, that forces companies to cut production costs under two broad strategic choices: (i) offshore and/or (ii) automate with more ‘intelligent’ machines that need fewer workers. Both result in layoffs, although less so under option (ii). I hypothesize here that automation has resulted in far more US job losses than has offshoring. Conclusive studies are lacking, although we have weak evidence of this in Miller (Reference Miller2016), Jaimovich and Siu (Reference Jaimovich and Siu2019), and Baldwin (Reference Baldwin2019). There is also a third option enabling companies to reduce costs, (iii) to squeeze or reduce worker wages, given the weakening of union strength.

Figure 5. Root causes and symptoms

It is very difficult to empirically disentangle the relative impacts of offshoring, automation, and the worker share of after-tax profits, as Autor et al. (Reference Autor, Dorn and Hanson2015), Jaimovich and Siu (Reference Jaimovich and Siu2019), and Michaels et al. (Reference Michaels, Natraj and Van Reenen2014) have found.

Another Research Question

But there is another research conundrum for economists and historians to probe – the mutually-reinforcing feedback loop between offshoring and hypercompetition (see Figure 5). Following the big reduction in tariffs under the Seventh GATT Conference, which concluded in 1979, the NAFTA treaty in 1995, China's accession to the WTO in 2001, and the easing of business rules and liberalization of government regulations regarding incoming FDI (Contractor, Dangol, Nuruzzaman, & Raghunath, Reference Contractor, Dangol, Nuruzzaman and Raghunath2020; World Bank, 2019), from the early 1990s companies found a much more welcoming trade and FDI environment, enabling them to offshore more easily than ever before.

As a research question, how did competition in the US and Europe (the root cause indicated in Figure 5) intensify? Was it initiated by increasing shipments from domestic Chinese or Mexican exporters, who put downward price pressure on European or US companies, which then triggered an offshoring and automation response to meet the import threat? Or was the offshoring initiated by US and European multinationals themselves, who, after sensing heightening competition with each other, consciously established export-oriented FDI affiliates in China and Mexico in order to take advantage of lower labor costs and bring the cheaper output back home?

Figure 6 suggests a partial answer from a Congressional Research Service report that drew data from a Chinese Ministry of Commerce source. In 1990, the percentage of China's exports done by foreign companies’ affiliates in China was only 12 percent. However, between 2001–2012 more than 50 percent of China's exports were done by foreign companies. It was only from 2013 onwards that domestic Chinese companies have accounted for more than half of China's exports. This suggests that the mutually-reinforcing feedback loop (illustrated in Figure 5) between hypercompetition and offshoring, in search of cheaper labor costs, was more the creation of US and European multinationals, rather than because of local Chinese exporters. The Chinese government may say to the US or Europeans complaining about China's trade surplus, ‘Don't blame us. Your own multinationals had a big role in making China the “factory of the world.”' This research question requires further investigation.

Figure 6. Percentage share of China's exports (and imports) done by foreign enterprises

Source: Morrison, Reference Morrison2019

At any rate, the broad conclusion of this article is that globalization (including offshoring) is only one symptom among several other corporate phenomena – such as automation, ICT, and wage reduction – that explain the resulting strains that have occurred in US politics and society.

Target article

A Decline in US Manufacturing Because of Globalization and China? Don't Believe This Fake News

Related commentaries (1)

The Decline of US Manufacturing: Issues of Measurement