INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic has created unprecedented disruptions to businesses around the world. As people reduced close personal contacts while engaging more with virtual forms of interaction, businesses faced major changes in regulations, organizational practices, and customer demand. These experiences of the pandemic are likely to have a long-term impact on individual behaviors and capabilities. Many observers thus expect major and persistent changes in business models (e.g., Ritter & Pedersen, Reference Ritter and Pedersen2020; Spicer, Reference Spicer2020), international value chains (e.g., Gereffi, Reference Gereffi2020; Shih, Reference Shih2020), and individual work patterns and career paths (e.g., Caligiuri, De Cieri, Minbaeva, Verbeke, & Zimmermann, Reference Caligiuri, De Cieri, Minbaeva, Verbeke and Zimmermann2020; Côté, Estrin, Meyer, & Shapiro, Reference Coté, Estrin, Meyer and Shapiro2020).

We argue that the crisis creates entrepreneurial opportunities that, if acted upon, help societies overcome the social and economic disruptions of the pandemic. Especially in emerging economies, entrepreneurs may be able to respond to such opportunities by identifying social needs and developing novel solutions to such needs. In consequence, entrepreneurial innovations (in business models and technologies) during the crisis shape the ‘new normal’ of post-COVID-19 societies, where behaviors and capabilities have changed as a consequence of the experience of the pandemic.

Our theoretical argument starts from the notion of resilience, the ability to react and recover from a crisis (Hamel & Välikangas, Reference Hamel and Välikangas2003; Williams, Gruber, Sutcliffe, Shepherd, & Zhao, Reference Williams, Gruber, Sutcliffe, Shepherd and Zhao2017). In particular, resilience is concerned with organizations’ ability to ‘bounce forward’ after a crisis; it does not imply a return to the status quo ante (Grandori, Reference Grandori2020). This distinction is important in cases of major external disruptions because businesses focusing on restoring past prosperity are likely to reinforce structural inertia and thus slow the process of attaining sustainable paths of economic growth. In contrast, where innovation, and hence internal disruption, interplays with external disruption, long-term growth paths may be quite distinct from pre-crisis paths of the economy.

Emerging economies entered the COVID-19 pandemic with, typically, less efficient institutional frameworks and less munificent resource environments (Gao, Zuzul, Jones, & Khanna, Reference Gao, Zuzul, Jones and Khanna2017; Meyer & Grosse, Reference Meyer, Grosse, Grosse and Meyer2019). However, many emerging economies have strong entrepreneurial communities skilled in making use of fairly ordinary resources. The ability to combine ordinary resources into novel competitive advantages has been referred to as compositional capability (Luo & Child, Reference Luo and Child2015; Zhou, Li, Zhou, & Prashantham, Reference Zhou, Li, Zhou and Prashantham2020), which is particularly valuable in contexts where many consumers are both cost conscious and very flexible (Krishnan & Prashantham, Reference Krishnan and Prashantham2019; Luo & Child, Reference Luo and Child2015). Recently, such strategies have extended beyond traditional focus on managing resource scarcity to powerful innovative strategies transforming industries with innovations in business models or products (Park, Zhou, & Ungson, Reference Park, Zhou and Ungson2013; Williamson & Wan, Reference Williamson, Wan, Grosse and Meyer2019; Yip & McKern, Reference Yip and McKern2016).

We argue that the capabilities entrepreneurs developed in volatile emerging markets also help to innovate when facing a major external shock such as the COVID-19 pandemic. With recent technological advances, notably digital platforms and databases (Jiang, Reference Jiang2020; Ma & Hu, Reference Ma and Hu2021), such entrepreneurs can access advanced resources from a broad range of potential partners and transform their industries. Indeed, the combination of entrepreneurial mindsets with a strong digital infrastructure and strong network relationships provide a foundation for entrepreneurial responses in emerging economies, and China in particular. Specifically, we draw attention to Chinese entrepreneurial ventures’ combination of (1) digital prowess and (2) a relational orientation that enable compositional renewal of their business models and thereby resilience in surviving the COVID-19 crisis.

We contribute to the ongoing discussion in this journal regarding the resilience of emerging economies (Grandori, Reference Grandori2020; Redding, Reference Redding2020; Välikangas & Lewin, Reference Välikangas and Lewin2020) by moving the focus from the policy environment to entrepreneurs, and to the drivers of entrepreneurial activity. This shift in focus has direct policy implications: If entrepreneurs play a vital role in enabling recovery, then government policies centralizing control of supporting incumbent industries (as frequently observed in 2020; Cirea et al., Reference Cirera, Cruz, Davies, Grover, Lacovone, Lopez Cordova, Medvedev, Okechukwu Maduko, Nayyar, Reyes Ortega and Torres2021; Mei, Reference Mei2020) are likely to be counterproductive.

Our argument is structured as follows. First, we review the recent literature to explain entrepreneurial behaviors at times of external disruption, and in emerging economies. To this end, we explore recent theoretical work – primarily on compositional capability (Luo & Child, Reference Luo and Child2015), which also echoes the notions of bricolage (Nelson & Lima, Reference Nelson and Lima2020) and effectual decision making (Sarasvathy, Reference Sarasvathy2001). Then we illustrate some entrepreneurial initiatives in the early months of the pandemic with a special focus on China. On this basis, we argue that many emerging economies are well positioned to take advantage of entrepreneurial opportunities arising during the crisis, and thus to shape post-COVID-19 societies. We outline implications for future research before concluding with policy implications.

RESILIENCE AND ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN DISRUPTED AND VOLATILE ENVIRONMENTS

The unprecedented economic and social disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic raises important questions regarding the resilience of organizations and societies, as highlighted in a recent forum in this journal (Redding, Reference Redding2020; Välikangas & Lewin, Reference Välikangas and Lewin2020; Zhou, Reference Zhou2020). The term ‘resilience’ describes organizations, systems, or individuals that are able to react and recover from duress or disturbances with minimal effects on stability and functioning (Hillmann & Guenther, Reference Hillmann and Guenther2021; Linnenluecke, Reference Linnenluecke2017). Resilience is the outcome of complex organizational processes before, during, and after a crisis (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Gruber, Sutcliffe, Shepherd and Zhao2017). Resilience refers not only to restoring the business prevailing before the crisis, but also to developing it to perform at least as well under the new conditions after the crisis (Hamel & Välikangas, Reference Hamel and Välikangas2003). Such ‘“bouncing forward” or “generative” resilience distinctively involves the imagination of the new in response to the unimagined’ (Grandori, Reference Grandori2020: 495). As Williams and Shepherd (Reference Williams and Shepherd2016) observed, following a major disaster, many entrepreneurs aim to ‘build back better’.

The drivers of such proactive resilience are entrepreneurs both within large organizations and as owners or mangers leading an organization. Joseph Schumpeter (Reference Schumpeter1936) attributed entrepreneurs a critical role as drivers of economic disruption, while Israel Kirzner (Reference Kirzner1973) emphasized the role of entrepreneurs in recognizing opportunities arising from disequilibria caused by external disruption, thus helping economies back towards and equilibrium.[Footnote 1] Both view entrepreneurship as a process of creating new combinations, and entrepreneurs as individuals who identify opportunities and take initiatives to exploit such opportunities. Thus, entrepreneurship encompasses both opportunity identification and exploration (Venkataraman, Reference Venkataraman1997).

However, there is a tension between these two views in that disruption is an outcome of Schumpeterian entrepreneurship and a driver of Kirznerian entrepreneurship. The COVID-19 pandemic represents an external disruption in the Kirznerian sense, inducing entrepreneurs to fill economic needs. However, we suggest that some entrepreneurs go beyond filling gaps and advance disruptive changes to their industries, notably in robotics and the digital economy. Thus, Kirznerian and Schumpeterian entrepreneurship dynamically interact. Before detailing how this may play out in China, we briefly introduce three literatures contributing to this debate: entrepreneurship following natural disasters, entrepreneurship in emerging markets, and a novel theoretical perspective relevant to such contexts – compositional strategy.

Entrepreneurs Facing Natural and Human-Made Disasters

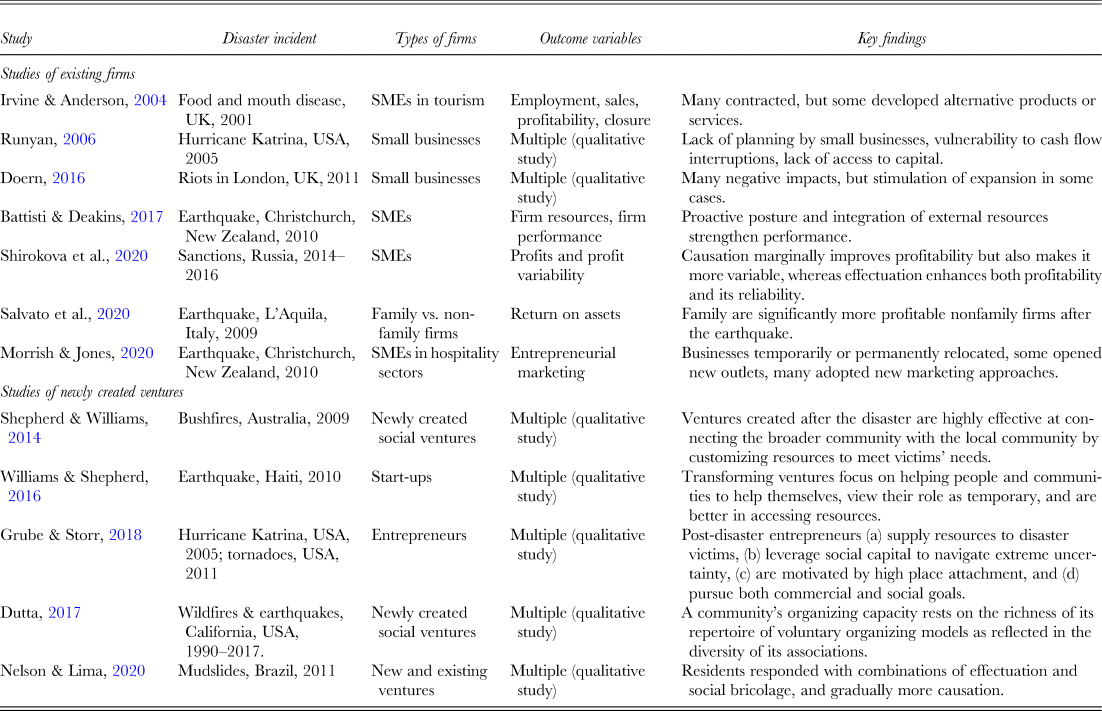

Do entrepreneurs prosper or falter when facing major disruptions in their environment? The literature on entrepreneurs facing natural disasters provides important pointers for studying responses to COVID-19, albeit the disasters studied are typically much narrower in geographic scope. As shown in Table 1, many authors emphasize the negative impact of disruption on existing entrepreneurial ventures. A particular concern is that resource constraints lead to underinvestment in innovation, which then limits firms’ ability to compete in the longer run.

Table 1. Studies on the impact of natural or human-made disasters

However, these same studies also find evidence that in some of the so impacted firms, the disruption fueled business expansion (Doern, Reference Doern2016). The ability to achieve such positive outcomes, however, depends on the characteristics of the entrepreneur. For example, Battisti and Deakins (Reference Battisti and Deakins2017) argue that a firm's proactive posture and capability to integrate external resources drive enhancements of its resource base and thus indirectly organizational performance.

Several qualitative studies shed light on the processes that enable small and entrepreneurial firms to respond to a natural disaster, such as bushfires in Australia (Shepherd & Williams, Reference Shepherd and Williams2014), an earthquake in Haiti (Williams & Shepherd, Reference Williams and Shepherd2016), hurricanes and tornadoes in the South of the US (Grube & Storr, Reference Grube and Storr2018), mudslides in Brazil (Nelson & Lima, Reference Nelson and Lima2020), as well as a series of natural disasters in California, US (Dutta, Reference Dutta2017). These studies develop a few common themes. First, they do not clearly separate for-profit and not-for-profit organizations, which reflects the charitable nature of many local initiatives in disaster zones, which may or may not result in a viable business in the longer run. Second, they emphasize the role of community in mobilizing resources, especially volunteers. Third, they emphasize local knowledge of the needs of the victims of the disaster as both motivation and resource driving these ventures.

Thus, external disruptions can trigger innovation by entrepreneurs. Specifically, characteristics of innovative start-ups in volatile environments also enable resilient responses to external disruptions because being innovative is a precondition for resilience, as entrepreneurs tend to constantly and continuously anticipate and adjust to a broad range of crises (Hamel & Välikangas, Reference Hamel and Välikangas2003; Linnenluecke, Reference Linnenluecke2017).

Entrepreneurship in Emerging Markets

The environment of emerging economies is typically subject to high levels of environmental uncertainty, arising from volatility in political, regulatory, and economic conditions. At the same time, specialized resources are scarce and consumer markets are typically large, but characterized by price sensitivity, low barriers to entry, and high volatility (Meyer & Peng, Reference Meyer and Peng2016). Despite – or perhaps because of – these contextual challenges, many emerging economies have developed vibrant entrepreneurial communities. Traditionally, innovation in emerging markets focused on local adaptation of foreign products and development of ‘good enough’ products (Chang & Park, Reference Chang and Park2012) or frugal innovation (Hossain, Levänen, & Wierenga, Reference Hossain, Levänen and Wierenga2021).

In recent years, the entrepreneurial scene has become far more dynamic. Several qualitative studies by leading scholars such as George Yip (Greeven, Yip, & Wei, Reference Greeven, Yip and Wei2019; Yip & McKern, Reference Yip and McKern2016; Yip & Prashantham, Reference Yip, Prashantham, Grosse and Meyer2019), Sam Park (Park, Zhou, & Ungson, Reference Park, Zhou and Ungson2013), Arie Lewin (Lewin, Valikangas, & Chen, Reference Lewin, Välikangas and Chen2017), and Peter Williamson (Williamson, Wan, Yin, & Lei, Reference Williamson, Wan, Yin and Lei2020; Williamson & Wan, Reference Williamson, Wan, Grosse and Meyer2019) illustrate powerful innovative strategies by indigenous firms. Notably in China, entrepreneurs have upgraded their innovations in view of dynamic competition that creates continuous pressure for firms to upgrade their knowledge base, their products, and their business models (Luo & Bu, Reference Luo and Bu2018; Yip & McKern, Reference Yip and McKern2016; Yip & Prashantham, Reference Yip, Prashantham, Grosse and Meyer2019). Many of the most consequential innovations in emerging markets are business model innovations, as highlighted in recent contributions in this journal (Ma & Hu, Reference Ma and Hu2021; Mehotra & Velamuri, Reference Mehotra and Velamuri2021).

This upgrading has been enabled by an interplay of several advancements, including education catch-up, diffusion of technology through global value chains, availability of engineers and research staff at comparatively low costs, and increasingly sophisticated local demand, for example from a rising middle class and from government projects (Yip & Prashantham, Reference Yip, Prashantham, Grosse and Meyer2019). However, while local entrepreneurs increasingly challenge foreign competitors in their market segments (Greeven et al., Reference Greeven, Yip and Wei2019; Williamson & Wan, Reference Williamson, Wan, Grosse and Meyer2019), their mindset remains informed by its roots in highly volatile and competitive domestic markets.

Theoretical Perspectives: Composition-Based View

In considering the resilience of entrepreneurs facing external disruption and/or operating in emerging economies, a useful starting point is the composition-based view (Luo & Child, Reference Luo and Child2015), which emphasizes the use of readily available (and ordinary) resources. The composition-based view resonates with two complementary yet distinct perspectives from entrepreneurship research: bricolage (relating to the use of resources that are ready to hand) (Baker & Nelson, Reference Baker and Nelson2005; Fisher, Reference Fisher2012) and effectuation (the means come first and the ends follow, as opposed to causation which is the reverse) (Prashantham, Kumar, Bhagvatula, & Saravathy, Reference Prashantham, Kumar, Bhagvatula and Saravathy2019; Sarasvati, Reference Sarasvathy2001).

Luo and Child (Reference Luo and Child2015) argue that emerging economy firms are adept at composition – that is, leveraging ordinary resources and integrating some level of product or service innovation with business model innovation at price-value ratios suitable to emerging economies. They suggest that they use a blend of imitation and innovation based on their ability ‘to synthesize and integrate disparate resources, including the open resources available to them’ (Reference Luo and Child2015: 389) while operating in an environment characterized by a shortage of core technologies, weak local brands, and little product differentiation. While technological knowledge accumulation is typically portrayed in advanced economies as a process of absorption, Luo and Child (Reference Luo and Child2015) point out that, in emerging economies, the emphasis is on the composition of suitable rather than superior technologies, with firms ‘adapting existing technologies and products rather than inventing entirely new ones’ (Reference Luo and Child2015: 380).

Luo and Child (Reference Luo and Child2015) allude to two features of the Chinese entrepreneurial landscape that are distinctive: (1) the ubiquity of (especially mobile) digital technologies and (2) the emphasis on relational norms. They illustrate the former with electronic device maker Xiaomi, which they show to utilize and combine various readily available digital technologies. The latter is described as a ‘unique ability to cultivate business networks’ (Reference Luo and Child2015: 387) which, they argue, along with Chinese firms’ market intelligence and ability to find open resources, contributes to their ability to compete on the basis of compositional innovation.[Footnote 2]

The compositional perspective indicates how resilience is enabled. First, by focusing on readily available means, entrepreneurs will have a bias for action, rather than acting defensively by denying transformations perceived as threatening (Elliot & Smith, Reference Elliott and Smith2006; Vuori & Huy, Reference Vuori and Huy2016). Second, the orientation to leveraging network relationships makes it possible to seek out and lean on resilient mentors for support and guidance (Prashantham & Floyd, Reference Prashantham and Floyd2019). Third, the associated agility enables entrepreneurs to pivot on emergent needs based on their understanding of their available resources (Brenk, Lüttgens, Diener, & Piller, Reference Brenk, Lüttgens, Diener and Piller2019). This theoretical perspective has been developed in particular in highly volatile or disruptive contexts, which makes it particularly relevant to the pandemic context.

ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN CHINA DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

The Chinese economy appears to have been more resilient than others in responding to the crisis, at least in the year 2020. Thus, China arguably provides a useful ‘natural experiment’. In the early period, i.e., before January 20, 2020, the policy response to the pandemic has been characterized by denial and ineffective sharing of information from local hospitals in Wuhan to key decision makers in the party and government (Zhou, Reference Zhou2020). In contrast, after January 20, 2020, the central government led a highly coordinated approach with strict regulations imposed on citizens and businesses, which created a radical institutional disruption but created some degree of control over the virus, while changing aspects of the continuously evolving institutional framework of its transition economy.

Initial evidence suggests that in China, the pandemic-induced economic downturn took a V-shape, quite distinct from many other countries, along with accelerating structural changes in at least some industries (Economist, 2020; Lin, Reference Lin2020). Principally, one can attribute this recovery to three effects: First, the Chinese government took decisive actions after January 20 that (almost) eradicated the virus within China. Second, e- and m-commerce businesses are highly developed in China, and consumers are used to digital communications and platforms for many daily activities, which gave them more options during the lockdown (Ba & Bai, Reference Ba and Bai2021; Jiang, Reference Jiang2020; Ma & Hu, Reference Ma and Hu2021). Third, Chinese entrepreneurs responded quickly by upscaling production of products suddenly in need, and by creating new business models to serve changing consumer needs. The arguments are complementary and potentially reinforce each other. While local policy makers often emphasize the first, we here explore the third argument.

For the analysis, we need to distinguish stages of the crisis. Some businesses saw demand surges early in the crisis, others saw temporary catch-up demand in later stages, while yet others likely face longer run shifts in demand that require preparing for a future ‘new normal’ (Ritter & Pedersen, Reference Ritter and Pedersen2020).

Managing Disruption: Survival

The pandemic and the ‘lock-downs’ in many locations immediately disrupted many aspects of business, including demand, costs of supplies, and in consequence cash flow. Initial reactions were often driven by survival needs as firms aimed to secure their viability in view of deteriorating financial performance and constraints on investments. Worldwide, thus, firms faced drop in revenues and consequently reduced their investments (e.g., Beck, Flynn, & Homanen, Reference Beck, Flynn and Homanen2020; Dai et al. Reference Dai, Feng, Hu, Jin, Li, Wang, Wang, Xu and Zhang2021).

Others faced disruptions in their global supply chains. First, disruptions at the point of manufacture in early stages of the crisis in China led to supply shortages in Europe and North America. Second, restrictions of international travel impacted in particular service aspects of global value chains, including sales and engineering, quality control, and after sales services (Côté et al., Reference Coté, Estrin, Meyer and Shapiro2020). Third, in many countries, supply bottlenecks for medical products led to political pressures for localization of critical supply chains, especially for food and health care related products (Gereffi, Reference Gereffi2020).

Facing these immediate disruptions, firms had to adapt their existing plans. Proactive early strategic responses were often supported by a combination of compositional strategies. Many Chinese entrepreneurial ventures have shown resilience in surviving the COVID-19 crisis, demonstrating a combination of digital prowess and relational orientation, using their extant resources in a manner consistent with composition to renew their business models. For example, TMiRob, a robotics ventures, was able to utilize its existing technology in a new context namely, to provide disinfection and service robots to emergency teams in Wuhan hospitals. Also, New Oriental, an education provider, almost instantly shifted almost all its students to its rapidly upgrading online learning platform – but still acted in a relational way by initiating donations to schools. Such relational behaviors, we argue, reflect the propensity for social embeddedness in China.[Footnote 3] JD Health's online pharmacy business coordinated a plethora of actors – including manufacturers, distributors, and volunteers – to launch the Hubei Drug Shortage Assistance Platform. Double Lucky Seafood Cuisine, an upmarket restaurant, not only switched to online delivery services, but did so with community-building initiatives by developing creative and engaging live cookery shows.

Two observations arise from the examples. First, digital competences (resulting from prior compositional processes) were leveraged. This evidence, albeit anecdotal, suggests that digital platforms have become a valuable external resource, and a channel to access other external resources. Second, many firms demonstrated a relational orientation in responding to social needs in their community. Such philanthropic actions can enhance reputation among network partners and other stakeholders (Brammer & Millington Reference Brammer and Millington2005; Zhang & Luo, Reference Zhang and Luo2013). The latter included charitable initiatives without doing their normal cost and benefit analysis, as reported in many scholarly blogs (e.g., Meyer, Pedersen, & Ritter, Reference Meyer, Pedersen and Ritter2020). Third, many of these initiatives involve new forms of interactions with consumers or facilitate changes in business customers internal operations – with potential long-term implications.

Managing Uncertainty: Envisaging a ‘New Normal’

In developing longer-term strategies during the COVID-19 crisis, firms faced unusually high degrees of uncertainty regarding the business environment. This crisis is structurally different from most economic downturns, such as those previously studied (see Table 1), because it triggered potentially enduring changes in individual routines, consumer preferences, resource availabilities, industry structures, and institutional frameworks. These external disruptions create opportunities for entrepreneurs to create business models that solve arising social needs by disrupting established business models.

Specifically, companies may aim to position themselves for a ‘new normal’, a competitive environment with new patterns of behavior and industry structures. However, the nature of such shifts was highly uncertain. In fact, there may be further disruptions such that it is more appropriate to speak of ‘a series of new normals’ (Shepherd, Reference Shepherd2020). Some industries experienced an early surge in demand during the crisis that may or may not have been temporary, including health care products, equipment for home offices, and certain online services. However, during the crisis, it was often hard to predict if a surge in demand would be lasting or not (Ritter & Pedersen, Reference Ritter and Pedersen2020), and hence how much investment in increased capacity would be justified (not to mention the fluidity of the competitive environment with many new entrants).

At least two theoretical arguments suggest that post-crisis demand for certain products or services, notably those involving digital technologies, would be significantly different from pre-crisis demand (Meyer, Reference Meyer, Fang and Hassler2021). First, consumer preferences are likely to change as a consequence of experiences during the crisis. For example, people are experiencing business models grounded in the internet economy, such as online shopping or video calling, and likely also adjust their preferences for the long run. For consumers in China, the impact of digitalization on (already fairly digitally savvy) buying behaviors during COVID-19 was considerable. For example, e-commerce consumption was boosted in categories associated with a healthy lifestyle – such as organic food and immunity-boosting supplements – and this shows signs of remaining high post-COVID-19. Online phenomena such as social commerce involving community group buying and livestreaming reflect the relational orientation of Chinese society, which in turn stems from its high levels of social embeddedness. These phenomena are likely to remain vibrant even after COVID-19-related restrictions have been relaxed. Among the examples introduced earlier, Koolearn and JD Health appear to benefit from changing attitudes to receiving services online, while TMiRob benefits from changing attitudes to robots versus people providing personal services.

Second, firms’ own resources are evolving during the crisis, especially their human capital. For example, many employees learned how best to handle technologies – including organizational processes to handle remote work effectively – while emergent technologies matured in terms of functionality. It is hard to think of any industry in China where firms don't view the application of digital technologies as essential, not discretionary. To illustrate, in the industrial (B2B) realm, innovative offerings such as head-mounted (thus, hands-free) AR-enabled devices, which have a range of applications (e.g., telemedicine or remote monitoring of manufacturing), became essential for many services during the pandemic – and demand seems set to stay robust in China even with the easing of restrictions. In such a case, a relational orientation goes hand in hand with a digital focus, with client companies, technology providers (e.g., Alibaba Cloud), and government entities (e.g., local health departments) in China having to work collaboratively to ensure client-specific customization and regulatory compliance (CEIBS, 2021). To further illustrate, teachers on Koolearn's education platform and doctors on JD Health's platform likely develop skills in communicating through these new mediums, which in turn enhances the quality of the service they deliver. This shift to work-from-home is likely to be permanent at least in some businesses (Caligiuri et al., Reference Caligiuri, De Cieri, Minbaeva, Verbeke and Zimmermann2020), which creates new entrepreneurial opportunities for coordination of work and for delivery of services (Hill, Reference Hill2020).

This enhancement of firms’ capabilities, along with lasting behavioral changes, can provide a basis for businesses to identify new entrepreneurial opportunities.

SYNTHESIS AND DIRECTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

Under the circumstances of the pandemic, certain entrepreneurial qualities commonly found in emerging economies are valuable not only for entrepreneurial growth but for economic recovery more broadly. We have argued that entrepreneurs can potentially play a pivotal role in helping societies overcome the disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic. They may become a driving force in structural transformations that develop the ‘new normal’ into societally desirable outcomes. This argument suggests that resilient entrepreneurs provide a foundation for a resilient society. Moreover, entrepreneurs used to high volatility and major disruptions are relatively well positioned to respond flexibly and timely to the pandemic. In other words, the combination of speed and flexibility, with recently upgraded innovation capabilities, places entrepreneurs in emerging economies in a strong position to promote innovations that will eventually shape post-COVID-19 societies.

We suggest that swift entrepreneurial action during a major disruption would benefit from compositional capability (Luo & Child, Reference Luo and Child2015; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Li, Zhou and Prashantham2020). While this is the primary lens we adopt, we note that this is also potentially supported by bricolage processes in managing (relative) resource scarcity (Fisher, Reference Fisher2012; Nelson & Lima, Reference Nelson and Lima2020) and effectual decision making (Sarasvati, Reference Sarasvathy2001, Reference Sarasvathy2008). In highly volatile contexts such as India or China with many cost-conscious but flexible consumers, this ability has historically supported jugaad innovation (Krishnan & Prashantham, Reference Krishnan and Prashantham2019; Radjou, Prahbhu, & Ahuja, Reference Radjou, Prahbhu and Ahuja2012; Yip & McKern, Reference Yip and McKern2016) or ‘good enough’ competition (Chang & Park Reference Chang and Park2012). However, these same capabilities also help entrepreneurs show resilience when facing major external shocks such as the COVID-19 disruption by utilizing novel types of resources, especially digital resources).

These reflections lead us to new research agendas for generative resilience in entrepreneurship in China, and in emerging economies more generally. First, the scholarly literature provides compelling theoretical suggestions regarding the impact of external shocks on entrepreneurship. Yet, while we found a number of studies linking external disruptions to performance variables such as access to finance, sales, and survival (Table 1), we did not find hard evidence regarding the impact on aspects of innovation, such as new product introductions, business model innovations, or break through of new technologies (as captured by e.g., sales from new products). We thus suggest a focus on innovation (in a broad sense) during the crisis, and the long-term impact of such innovation on resilience of the economy and the society more broadly. Specifically, the pandemic offers a quasi-natural experiment to explore further the notions of entrepreneurial opportunity and entrepreneurial impact emanating from crisis.

Second, in the literature on disaster responses, we noted a focus on ‘bouncing back’ on the previous economic path, rather than ‘bouncing forward’ (Grandori, Reference Grandori2020) onto a new technology trajectory or an accelerated growth path. In other words, the entrepreneurship observed in these studies appears to be primarily of Kirznerian type – identifying opportunities arising from disequilibria in the economy and thus helping the economy to move back to an equilibrium. This literature, by design, focuses on disasters that are limited in geographic and temporal space. Yet, the current pandemic is creating broader challenges because the likely persistence of certain changes in human behaviors. This raises the question if and under what conditions an external disruption triggers Schumpeterian entrepreneurship that eventually helps transforming industries or economies.

Third, future research may provide deeper insights into entrepreneurial processes in different types of firms at times of external disruption. In particular, relational orientation is widely associated with Chinese business norms and entrepreneurship (e.g., Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007), but we do not understand well how it links to the idea of resilient responses to crisis. Furthermore, as seen from the brief examples we provided, relationship building behaviors such as volunteering and donations have gone hand-in-hand with digital technology, another pervasive feature of modern Chinese life. This relational-digital combination warrants further research attention with respect to entrepreneurial responses to external disruption.

Finally, a paramount question concerns the context for entrepreneurship. To what extent is what we observed specific to China and, more generally, how do aspects of the social, technological, and institutional environment impact entrepreneurship in disaster response situations? Future research could tease out how social embeddedness is leveraged in a crisis differently in China and other Asian emerging markets, such as India. In particular, the role of ties with non-market actors and the contingent effects of the political system may have an important effect on how social embeddedness influences entrepreneurs' coping with a crisis. Moreover, comparative studies with other countries that kept the pandemic under control relatively quickly, such as Japan, Vietnam, or New Zealand, can generate insights on institutional influences on entrepreneurship. The distinctive features of digital technology and a relational orientation in China are especially worth comparing with other settings to examine how these attributes vary across different contexts, and whether other regions have their own distinctive features that came to the fore in their entrepreneurial (or other) response to the crisis.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

We have argued that entrepreneurs in emerging economies, and China in particular, are well positioned to respond to emergent opportunities and thereby to drive not only economic recovery but also economic restructuring by advancing novel business models and technologies. This argument has direct implications for practice.

For managers and entrepreneurs, our analysis suggests that in the face of a major crisis, they ought to focus on resources they control, and consider opportunities they can create with these resources. In the 21st century, these resources specifically include digital resources, and resources accessed via digital platforms. While detailed causal analysis and planning may be appropriate at other times, major external shocks require a different approach. Compositional strategies are appropriate especially in volatile and disruptive environments and are likely to have a long-term impact: Resources such as networks and reputation created during the crisis can create early mover advantages for the post-crisis recovery. In fact, managers in advanced and stable environments may find ideas on how to revitalize their entrepreneurial spirits in emerging markets.

For policy makers concerned with resilience at the level of societies (as addressed by e.g., Redding, Reference Redding2020; Välikangas & Lewin, Reference Välikangas and Lewin2020), we suggest that entrepreneurial initiatives are core to advancing new technologies and new forms of organizing. This in turn implies that entrepreneurship merits support through government policy initiatives, for example regulatory change to facilitate contact-less economy, online-to-offline businesses, or structural reforms in health care. Our suggested focus on entrepreneurship challenges the predominant tendency of policy responses during the pandemic that emphasize centralization of control and support for incumbent firms, in China and elsewhere (Cirera et al., Reference Cirera, Cruz, Davies, Grover, Lacovone, Lopez Cordova, Medvedev, Okechukwu Maduko, Nayyar, Reyes Ortega and Torres2021; Zhou, Reference Zhou2020).