A headquarters’ formal decision-making authority means little if its actions are not perceived as legitimate.

(Brenner & Ambos, Reference Brenner and Ambos2013: 791)INTRODUCTION

The issue of headquarters (HQ)-subsidiary relationships in multinational corporations (MNCs) has remained a contentious one in international business (IB) research that has spanned five decades (Kostova, Marano, & Tallman, Reference Kostova, Marano and Tallman2016; Paterson & Brock, Reference Paterson and Brock2002). Prior research has indicated that HQ-subsidiary relationships in MNCs typically become ‘strained or even adversarial’ (Bartlett & Ghoshal, Reference Bartlett and Ghoshal1986: 88), manifest in power struggles (Bouquet & Birkinshaw, Reference Bouquet and Birkinshaw2008; Geppert & Dörrenbächer, Reference Geppert and Dörrenbächer2014) that are dysfunctional for the MNCs (Blazejewski & Becker-Ritterspach, Reference Blazejewski, Becker-Ritterspach, Dörrenbächer and Geppert2011). Under such problematic relationships (Kostova & Roth, Reference Kostova and Roth2002; Kostova & Zaheer, Reference Kostova and Zaheer1999; Tempel, Edwards, Ferner, Muller-Camen, & Wächter, Reference Tempel, Edwards, Ferner, Muller-Camen and Wächter2006), a subsidiary may resolve to meet local demands by seeking greater autonomy (Ambos, Askawa, & Ambos, Reference Ambos, Asakawa and Ambos2011), stronger influence (Bouquet & Birkinshaw, Reference Bouquet and Birkinshaw2008) and favourable mandates (Birkinshaw, Reference Birkinshaw1996), and by engaging in issue selling (Balogun, Jarzabkowski, & Vaara, Reference Balogun, Jarzabkowski and Vaara2011) and other micro-political negotiations vis-à-vis the HQ (Dorrenbacher & Gammelgaard, Reference Dörrenbächer and Geppert2006).

Facing the internal legitimacy challenge thus portrayed, the adoption of control plays an important role for the HQ in pursuing its goals (Jaussaud & Schaaper, Reference Jaussaud and Schapper2016) by seeking to induce compliant subsidiary behaviours (Blazejewski & Becker-Ritterspach, Reference Blazejewski, Becker-Ritterspach, Dörrenbächer and Geppert2011) through the adoption and implementation of various administrative or social arrangements (Harzing, Reference Harzing1999; Jaussaud & Schaaper, Reference Jaussaud and Schapper2016). Nevertheless, even when implementing its mechanisms of output, process, and social control, the HQ may still find it difficult to achieve effective subsidiary management unless both the HQ and its controls are perceived as credible and legitimate (Brenner & Ambos, Reference Brenner and Ambos2013). As Beetham (Reference Beetham1991: 31–32) points out, ‘the quality of performance needed from the subordinate party in a relationship, and the degree of legitimacy the relationship requires, are closely connected’. In other words, the legitimacy of the HQ's controls requires recognition of the HQ's ‘right to govern’ (Courpasson, Reference Courpasson2000).

While there is a growing concern about the organizational challenges for establishing the legitimacy of controls in MNCs (Brenner & Ambos, Reference Brenner and Ambos2013; Sageder & Feldbauer-Durtmuller, Reference Sageder and Feldbauer-Durstmuller2019), ‘the lack of attention to legitimation processes in HQ-subsidiary relationships is a serious omission’ (Balogun et al., Reference Balogun, Fahy and Vaara2019: 224). So it would be meaningless to study legitimation in a vacuum without also investigating those entities (i.e., control mechanisms) that are being legitimized, as a step toward understanding legitimation in our focal organization. However, salient studies of MNCs have either focused on the power struggles and contestations between the HQ and its subsidiaries (Bouquet & Birkinshaw, Reference Bouquet and Birkinshaw2008; Geppert & Dörrenbächer; Reference Geppert and Dörrenbächer2014) or on the perceived legitimacy of particular strategic decisions taken by the HQ (Balogun et al., Reference Balogun, Fahy and Vaara2019; Brenner & Ambos, Reference Brenner and Ambos2013; Li, Xia, & Lin, Reference Li, Xia and Lin2017) and foreign subsidiaries (Conroy & Collings, Reference Conroy and Collings2016) from developed nations. Thus there is a gap in literature regarding how the HQ of a developing MNC can, through legitimation, render effectual its controls over foreign subsidiaries.

Heeding a recent call for more research on HQ-subsidiary relationships in ‘new types of MNCs’ (Kostova et al., Reference Kostova, Marano and Tallman2016: 182), our research will focus on the strategies of legitimation, through which the legitimacy of the controls imposed by the HQ is created and maintained in the context of a developing MNC. Accordingly, our first research question (RQ) is: What mechanisms do the HQ of a developing MNC adopt for controlling outputs, work processes, and behaviour in its subsidiaries?

A Chinese MNC provides an interesting research context for advancing our current state of knowledge about the role of legitimacy in HQ-subsidiary relationships (Kostova & Zaheer, Reference Kostova and Zaheer1999; Kostova & Roth, Reference Kostova and Roth2002). Given that for Chinese MNCs, ‘their corporate images and legitimacy in host countries are unfavourable’ (Wei & Nguyen, Reference Wei and Nguyen2017: 1010), such scepticism may spill-over to colour the views of local employees and managers in Chinese MNCs, and challenge the arrangements and practices of the HQ as illegitimate and inappropriate in local contexts (Fang & Chimenson, Reference Fang and Chimenson2017; Hadjikhani, Elg, & Ghauri, Reference Hadjikhani, Elg and Ghauri2012). Since gaining legitimacy would confer upon a Chinese HQ the ‘right to govern’ (Courpasson, Reference Courpasson2000), the converse of this, i.e., subsidiaries’ lack of acceptance of certain control mechanisms, might serve to undermine HQ-subsidiary relationships in Chinese MNCs, thus inducing uncooperative behaviours. Lack of understanding about the use of legitimation as a rhetorical device for strengthening HQ-based controls over subsidiaries constitutes a notable gap in the literature about Chinese MNCs. Hence, our second RQ is: How can the HQ of a Chinese MNC seek to legitimize its controls to ensure subsidiary cooperation?

The rest of the article is organized into four main parts. First, we review HQ controls from a legitimacy perspective and identify associated legitimation challenges for Chinese MNCs. We then explain our methodology and discuss the main findings in the context of our research questions. We conclude the article by explaining our main theoretical and practical contributions, and by discussing limitations and future research directions.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

HQ Controls and Their Legitimation in MNCs

MNCs can be conceived as ‘complex organizational entities with intricate and multifaceted internal political processes’ (Geppert, Becker-Rittenspach, & Mudambi, Reference Geppert, Becker-Ritterspach and Mudambi2016: 1210). HQ-subsidiary relationships have long been viewed as inherently problematic (Blazejewski & Becker-Ritterspach, Reference Blazejewski, Becker-Ritterspach, Dörrenbächer and Geppert2011; Geppert & Dörrenbächer; Reference Geppert and Dörrenbächer2014; Lange & Becker-Ritterspach, Reference Lange, Becker-Ritterspach, Becker-Ritterspach, Blazejewski, Dörrenbächer and Geppert2016; Morgan & Kristensen, Reference Morgan and Kristensen2006). The HQ faces the prospect that, driven by self-interest (Balogun et al., Reference Balogun, Jarzabkowski and Vaara2011) and desire for greater autonomy (Bouquet & Birkinshaw, Reference Bouquet and Birkinshaw2008), some subsidiaries will seek to act as ‘subversive strategists’ (Morgan & Kristensen, Reference Morgan and Kristensen2006). The HQ may accordingly seek to strengthen its control, conceived as ‘the process by which one entity influences, to varying degrees, the behaviour and output of another through the use of power, authority and a wide range of bureaucratic, cultural and informal mechanisms’ (Geringer & Hebert, Reference Geringer and Hebert1989: 236–237). In turn, there are likely to be differences of opinion between the HQ and foreign subsidiaries regarding the merits of such control mechanisms, especially those that involve resources, behaviour, and outputs (Harzing, Reference Harzing1999).

Legitimacy as ‘a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate’ (Suchman, Reference Suchman1995: 574) forms the basis for exercising authority and influence, i.e., legitimate power (Leach, Reference Leach2005) in organizations. Leach (Reference Leach2005) distinguishes between authority and coercion in exercising formal power in organizations. The authority of an entity to exercise formal power depends on perceptions among organization members that such formal power is legitimate. Organization members are likely to go along willingly with formal power exercised by an entity that they perceive as having legitimate authority. However, if organization members perceive that the formal power exercised by an entity lacks legitimacy, then they will regard that power as coercive in nature, and if they go along with it, they will do so only grudgingly, in order to obtain resources or avoid sanctions, and not willingly.

Leach (Reference Leach2005) similarly draws distinctions between influence and manipulation, with the former reflecting legitimate informal power and the latter reflecting illegitimate informal power. Organization members are likely to accept informal influence if they are persuaded or won over by it, whereas they will only go along with being manipulated if they are unwittingly deceived by it or wish to avoid the prospect of social disapproval if they demur.

It would follow from Leach's (Reference Leach2005) analyzes that in an MNC, the ability of the HQ to exercise authority or influence over the subsidiaries depends on perceptions among the latter that the respective formal or informal controls are legitimate (Brenner & Ambos, Reference Brenner and Ambos2013). In the event that foreign subsidiaries perceive that the HQ lacks legitimacy, i.e., ‘may lack credibility within the focal subsidiary’ (Brenner & Ambos, Reference Brenner and Ambos2013: 777), and are sceptical about the HQ's roles and contributions (Li et al., Reference Fiaschi, Giuliani and Nieri2017; Nell & Ambos, Reference Nell and Ambos2013), they are likely to engage in opportunistic behaviours (Oliver, Reference Oliver1991; Saka-Helmhout & Geppert, Reference Saka-Helmhout and Geppert2011) and other kinds of politicking (Holm, Decreton, Nell, & Klopf, Reference Holm, Decreton, Nell and Klopf2017; Tempel et al., Reference Tempel, Edwards, Ferner, Muller-Camen and Wächter2006). These non-compliant responses may include issue selling (Conroy & Collings, Reference Conroy and Collings2016), ‘continuous search for mandate extension’ (Morgan & Kristensen, Reference Morgan and Kristensen2006: 1480), and ‘acquiring or accessing local idiosyncratic resources to enhance (their) power within the organization’ (Chen, Chen, & Ku, Reference Chen, Chen and Ku2012: 259).

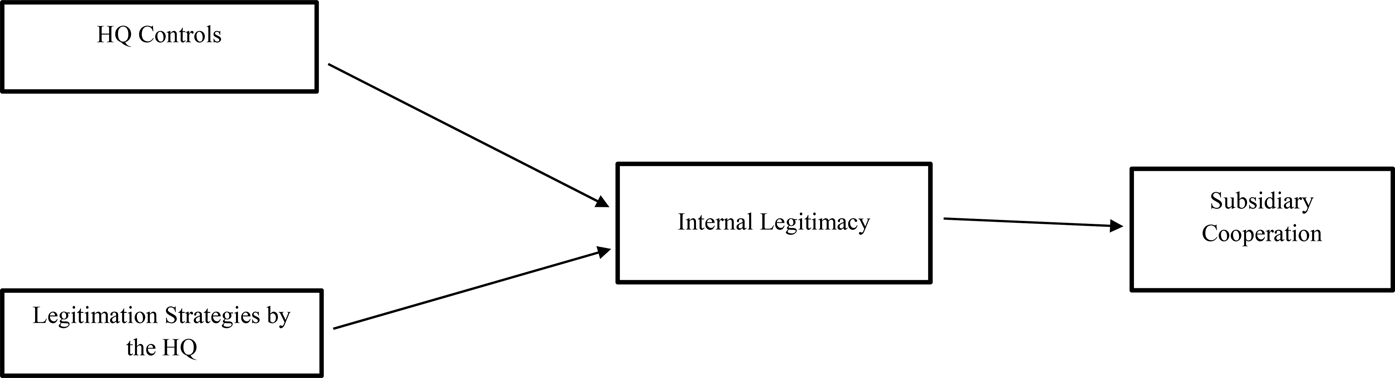

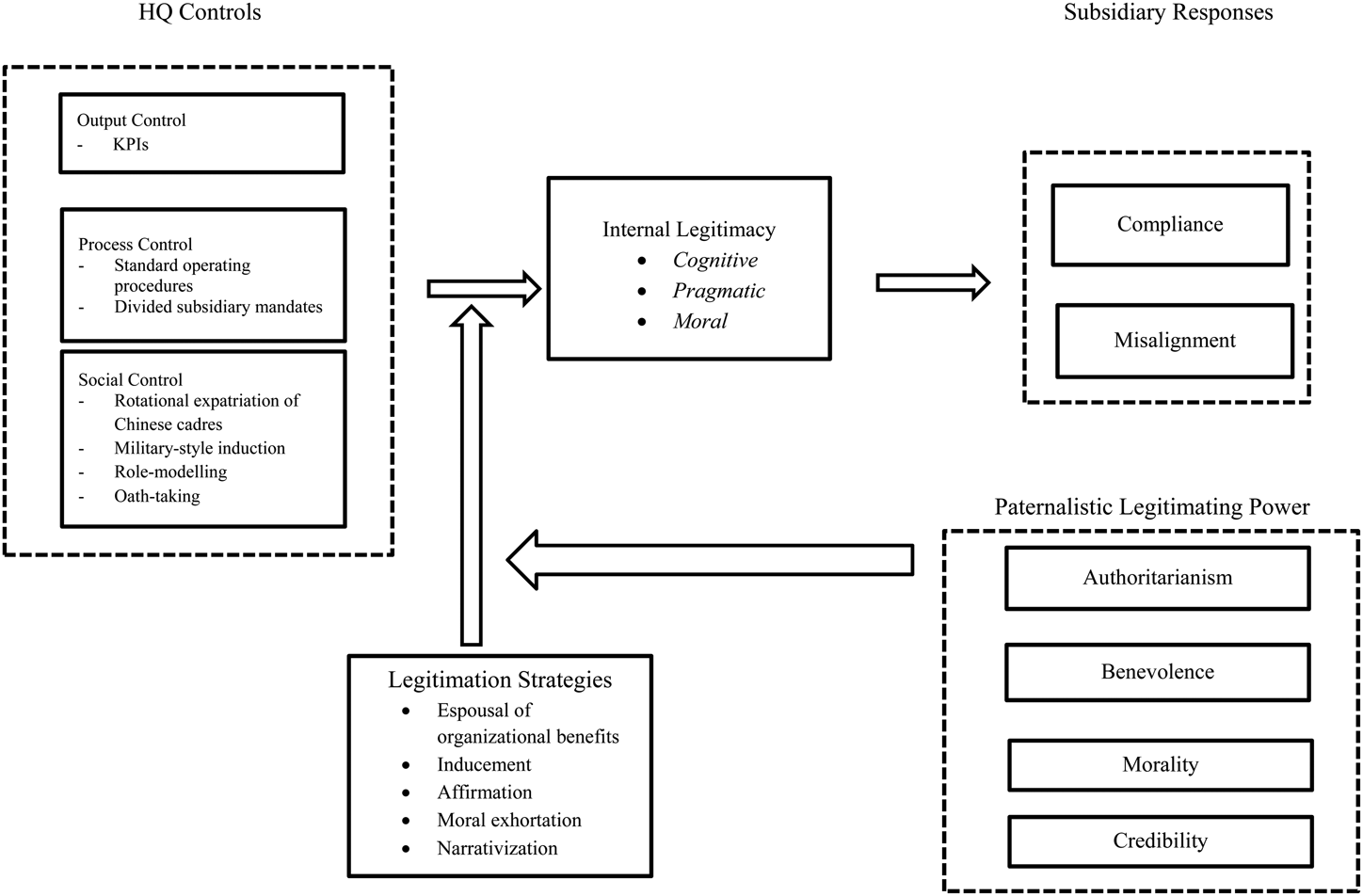

Drawing on the assertion that ‘a consideration of internal legitimacy strikes at the heart of discussions in the international business literature regarding the nature of the tensions that characterize HQ-subsidiary relationships and decision-making’ (Balogun, Fahy, & Vaara, Reference Balogun, Fahy and Vaara2019: 226), this article focuses on how an HQ can seek to build and maintain legitimacy for its means for subsidiary control (see Figure 1). In our study, internal legitimacy is defined as ‘the acceptance and approval of an organizational unit by the other units within the firm’ (Kostova & Zaheer, Reference Kostova and Zaheer1999: 72). Assessing the alignment of cognitive understandings, normative evaluations, and pragmatic interests (Suchman, Reference Suchman1995) between the HQ and its subsidiaries ‘requires dual consideration of the legitimacy judgments of organizational members and [of] the managerial legitimation strategies’ (Balogun et al., Reference Balogun, Fahy and Vaara2019: 224). In the findings section of this article, besides analysing the means adopted by an HQ for exerting control vis-à-vis its subsidiaries, we shall also analyze the various means of legitimation employed by the HQ that are designed for ‘creating a sense of positive, beneficial, ethical, understandable, necessary, or otherwise acceptable action in a specific setting’ (Vaara & Tienari, Reference Vaara and Tienari2008: 986). We shall also analyze the role of Mr. Ren Zhengfei as a paternalistic leader with widely respected authority to provide legitimation for the various means of control. Preceding this, in the case background subsection of our methods section, we outline the track record of achievements by the firm, which we also consider relevant to the perceived internal legitimacy of the HQ as a control centre.

Figure 1. A conceptual model

For example, we anticipate some relationships between Suchman's (Reference Suchman1995) three main types of legitimacy and three of the legitimation strategies identified by Vaara and Tienari (Reference Vaara and Tienari2008). Let us consider, first, the types of legitimacy (Suchman, Reference Suchman1995). Cognitive legitimacy concerns whether an item for legitimation, which in our case would be a control mechanism or one of its key features, can be readily explained and understood on the basis of culturally familiar ‘common sense’. Pragmatic legitimacy could address the mutual self-interest of the subsidiary, the HQ, and the affected organization members, such as whether a particular control mechanism is perceived as helpful in enhancing quality, averting mistakes, or rewarding good performance. Moral legitimacy would concern whether a control mechanism could be regarded as right and proper from a social desirability perspective.

For the purpose of our study, we shall construe legitimation as the rhetorical means employed by an entity (i.e., the HQ) toward the aim of achieving and maintaining the acceptability to particular stakeholders (i.e., the subsidiaries) of particular arrangements and obligations (i.e., controls). Particular types of legitimation (Vaara & Tienari, Reference Vaara and Tienari2008) may constitute attempts to gain or maintain particular types of legitimacy (Suchman, Reference Suchman1995). Our concern with legitimation is based on the premise that seeking to exert HQ control over subsidiaries in the absence of legitimacy becomes naked coercion, which cannot actually force local managers to comply if the latter remain able to access and utilize locally embedded resources for resistance (Hong & Snell, Reference Hong, Snell and Mak2016; Morgan & Kristensen, Reference Morgan and Kristensen2006). The perceived necessity of legitimation in such cases is illustrated by a recent case study (Balogun et al., Reference Balogun, Fahy and Vaara2019) of how the senior management in a European region of another MNC provided extensive and multifaceted legitimation for their decision to relocate the regional head office, and to centralize policy making there. In that case (Balogun et al., Reference Balogun, Fahy and Vaara2019), announcements in the run up to the new arrangements were greeted by strong vocal opposition from employees at the affected subsidiaries, but the accompanying and ensuing legitimation appeared to help employees to come to terms with the new situation.

Next, we shall explain how three of Vaara and Tienari's (Reference Vaara and Tienari2008) legitimation strategies may relate to internal control mechanisms and to the seeking of Suchman's (Reference Suchman1995) three types of legitimacy. Rationalization involves referring to evidence about the utility of particular control mechanisms, or in the absence of such evidence, it involves articulating expectations that may be regarded as reasonable and favourable regarding their likely outcomes, and hence may, depending on the emphasis, seek to establish cognitive or pragmatic legitimacy. Moral evaluation or moralization involves invoking value systems that support or justify a control mechanism, and hence is congruent with attempts to establish the moral legitimacy of that mechanism. Mythopoesis or narrativization involves the use of storytelling about how a control mechanism is related to a familiar cultural or historical phenomenon and about the role the mechanism will play in the future. To the extent that mythopoesis involves conveying a sense of destiny or inevitability, it may constitute an attempt to establish cognitive legitimacy.

Challenges in the Legitimation of HQ Controls in Chinese MNCs

There has been a consensus within the growing stream of studies on the globalization of Chinese firms that Chinese HQs seek to exert a high degree of control over their subsidiaries (Auffray & Fu, Reference Auffray and Fu2015; Huang, Reference Huang2011; Sun, Reference Sun2009), reflecting their institutional and cultural heritage (Bartlett & Ghoshal, Reference Bartlett and Ghoshal1988; Redding, Reference Redding2014). However, as compared to western MNCs (Blazejewski & Becker-Ritterspach, Reference Blazejewski, Becker-Ritterspach, Dörrenbächer and Geppert2011; Ciabuschi, Forsgren, & Martin, Reference Ciabuschi, Forsgren and Martin2012), Chinese HQs face greater challenges in achieving legitimacy for their controls over their foreign subsidiaries. For example, many Chinese MNCs have a relatively short history of internationalization (Williamson, Ramamurti, Fleury, & Fleury, Reference Williamson, Ramamurti, Fleury and Fleury2013). Some of them may accordingly lack sufficient foreign experience (Meyer & Thaijongrak, Reference Meyer and Thaijongrak2013), and thus incur the liabilities of foreignness (Child & Rodrigues, Reference Child and Rodrigues2005; Klossek, Linke, & Nippa, Reference Klossek, Linke and Nippa2012) and outsidership (Schaefer, Reference Schaefer2020) when facing complex and unfamiliar institutional overseas environments. Where this is the case, a Chinese MNC's lack of ‘capacity to adjust to conditions in their host contexts’ (Child & Marinova, Reference Child and Marinova2014: 349) may make it difficult for the HQ to engage in the selection and deployment of control systems that are deemed ‘desirable, proper, or appropriate’ (Suchman, Reference Suchman1995: 74) by foreign subsidiaries. For example, compared to western counterparts, Chinese MNCs tend to employ a higher ratio of senior expatriates for controlling and managing the daily operations of foreign subsidiaries (Auffray & Fu, Reference Auffray and Fu2015), but deficiencies in the expatriates’ management and leadership skills have caused resentment among local employees (Cooke, Reference Cooke2014).

Also, Chinese MNCs may potentially suffer from negative ‘legitimacy spillovers’ (Kostova & Zaheer, Reference Kostova and Zaheer1999), arising from adverse media reports about practices in the home country that are considered questionable (Engels-Zandén, Reference Engels-Zandén2007), in turn reflecting an unfavourable country of origin image (Chintu & Williamson, Reference Chintu and Williamson2013). Such reports may induce skepticism among local employees about the HQ's underlying motives (Fang & Chimenson, Reference Fang and Chimenson2017) for importing particular behavioural controls from China.

Furthermore, as illustrated in a recent case study of a Chinese MNC in the UK (Lai, Morgan, & Morris, Reference Lai, Morgan and Morris2020), even though behavioural controls that are legitimized by symbols and stories embedded in wider discourses about the history of the home country may be meaningful and attractive to many expatriate managers, such narratives may be incomprehensible to or unappealing to locally employed organization members. In such cases, either the latter may need to be exempted from the corresponding controls, or some alternative means of legitimation may be adopted, suitable for non-home country originated employees.

To sum up thus far, this study follows others (Balogun et al., Reference Balogun, Fahy and Vaara2019; Brenner & Ambos, Reference Brenner and Ambos2013) in adopting the concepts of legitimacy (Suchman, Reference Suchman1995) and legitimation (Vaara & Tienari, Reference Vaara and Tienari2008) to analyze HQ-subsidiary relationships in a Chinese MNC, based on the premise that Chinese HQs are faced with some inherent internal legitimacy challenges. Specifically, the main concern regarding internal control facing Chinese MNCs may stem from negative perceptions about the legitimacy of organizational practices from the home country. In this regard, even though Chinese HQs may possess resource power, their ‘control may not automatically be perceived as legitimate’ (Brenner & Ambos, Reference Brenner and Ambos2013: 777). Since Chinese HQs need to enhance their authority to govern by legitimizing their controls, and since this is problematic, viewing HQ-subsidiary relationships from an organizational legitimacy perspective is therefore considered as an appropriate and relevant focus for our study.

With reference to the case of Huawei Technologies Co. Ltd (‘Huawei’), a Chinese MNC facing the liabilities of foreignness (Child & Rodrigues, Reference Child and Rodrigues2005), origin (Chintu & Williamson, Reference Chintu and Williamson2013), and outsidership (Schaefer, Reference Schaefer2020), we aim to provide ‘context-sensitive’ explanations (Plakoyiannaki, Wei, & Prashantham, Reference Plakoyiannaki, Wei and Prashantham2019) to advance our understanding about control and legitimation in MNCs by investigating how a Chinese HQ provides legitimation for its controls to ensure subsidiary cooperation.

METHODS

With the aim of obtaining a contextualized understanding of how an HQ of a PRC-based MNC seeks to legitimize and render effectual a comprehensive set of controls over its foreign subsidiaries, we undertook a single, instrumental case study (Eisenhardt, Reference Eisenhardt1989; Stake, Reference Stake1995; Yin, Reference Yin1994) of a particular Chinese firm, which has over two decades of international experience, and does business in over 170 countries. We adopted a qualitative approach to analyze the controls that were being orchestrated by the HQ, and the associated rhetorical discourses of legitimation for those controls. Although it was not possible to gather extensive data about the relationships between the HQ and particular subsidiaries, we sought to understand the overall pattern of subsidiaries’ responses to the controls, based on ‘down-to-earth descriptions’ (Yanow, Reference Yanow2004). We considered that although a single case study would not be conducive to broad generalization (Silverman, Reference Silverman2013; Stake, Reference Stake1995), it would have potential value in driving theory development.

The Focal Firm

Huawei is headquartered in Shenzhen, China. It has over 170,000 employees worldwide (Huawei, 2016), around half of whom work in R&D (Sun, Reference Sun2009). The firm was founded in 1987 by Mr. Ren Zhengfei, who had previously served in the People's Liberation Army (Zhang & Wu, Reference Zhang, Wu and Petti2012: 117). By 2004, Huawei had established subsidiaries on all six continents. Huawei currently sells telecommunication network equipment, IT products and solutions, and smartphones in more than 170 countries and regions (Huawei, 2016). Among Huawei's foreign subsidiaries, most focus exclusively on sales and service, while the others focus exclusively on providing internal services such as pursuing R&D within specialist domains. The design, installation, and maintenance of overseas telecommunications networks is managed by Chinese expatriates, working closely with specialists in the Shenzhen HQ. Huawei divides its global markets into the PRC and seven other zones, and each of the eight regional HQs reports directly to the firm's marketing management committee (Sun, Reference Sun2009: 139). By 2015, Huawei's revenue was approximately CNY 395 billion (USD 60.8 billion), which entailed a year-on-year increase of 37% (Huawei, 2016). Huawei ranked 129th on the Global Fortune 500 based on revenue in fiscal year ending 31st March 2016 (Fortune, 2016).

We chose Huawei as our case study because it is a Chinese MNC that has achieved market success across much of the world, while apparently maintaining strong, legitimate control by the HQ over its overseas subsidiaries. As an emerging MNC and latecomer to the global market in 1997 (Chong, Reference Chong2018), Huawei did not initially enjoy sufficient legitimacy (Suchman, Reference Suchman1995) vis-à-vis stakeholders in developed economies for the purpose of ‘incorporating ideas and objectives into foreign subsidiaries’ (Brenner & Ambos, Reference Brenner and Ambos2013: 777). Huawei's internationalization process therefore proceeded incrementally, in a pattern resembling the Uppsala approach (Johansson & Vahlne, Reference Johanson and Vahlne1977). The sequence of Huawei's foreign entries appears to have been important in overcoming the liability of foreignness and overcoming legitimacy deficits. Foreign expansion began in Africa and other peripheral markets, replicating Huawei's earlier development within China that began in rural outposts before moving into the Tier One cities (Chong, Reference Chong2018; Hensmans, Reference Hensmans2017; Sun, Reference Sun2009; The Economist, 2011). During the early expansion into host countries with significant institutional voids and adverse market conditions (Khanna & Palepu, Reference Khanna and Palepu2010), Chinese expertise could attract more respect and face less competition than it would have done in more established markets. The HQ could accordingly cast itself as the primary source of managerial and technological competencies, while accumulating international experience, and building cognitive and pragmatic legitimacy along with core competencies (Kostova & Roth, Reference Kostova and Roth2002), in preparation for its subsequent entry into more developed countries (Kotabe & Kothari, Reference Kotabe and Kothari2016), such as those in Western Europe.

There are four other distinctive corporate features of Huawei. First, its culture has been described as characterized by strict discipline, hard work, single-minded purpose, high pressure, and high efficiency (Su & Chen, Reference Su, Chen, Su and Chen2014; Sun, Reference Sun2009). Prior to Huawei's overseas expansion, which began in the mid-1990s, such characteristics attracted the labels of ‘Mattress Culture’, reflecting the practice of not going home to sleep (Chen, Reference Chen2007: 144–145) and ‘Karoshi Culture’ (Su & Chen, Reference Su, Chen, Su and Chen2014: 77–78). Contemporary sources indicate that the high pressure culture persists (Su & Chen, Reference Su, Chen, Su and Chen2014; Zhang & Wu, Reference Zhang, Wu and Petti2012), even as Huawei has gained recognition for innovation (Fast Company, 2017; Hensmans, Reference Hensmans2017).

Second, Huawei operates an employee share ownership scheme, which, until recently, for legal reasons was open to Chinese employees only and is tied to current employment (Su & Chen, Reference Su, Chen, Su and Chen2014; Zhang & Wu, Reference Zhang, Wu and Petti2012). In 2014, around 75,000 Chinese Huawei employees owned more than 90% of Huawei stock (Zhang & Wu, 2014). Although these are only ‘virtual shares’, as the stock itself is held by Huawei's Trade Union committee, current employees owning the shares earn dividends and hold voting rights. However, they do not possess unrestricted rights to sell their shares at will or to retain them after leaving Huawei (Yang, Reference Yang2019). Furthermore, while conferring strong performance incentives to shareholding employees in Huawei, this particular scheme has not empowered them to participate in strategic decision making (Zaagman, Reference Zaagman2019).

Third, unlike most emerging MNCs, Huawei's subsidiaries are almost all greenfield sites (Morphy, Reference Morphy2018; Schaefer, Reference Schaefer2020), ostensibly in order to increase the HQ's influence over institution building (Clark & Geppert, Reference Clark and Geppert2011), although there are exceptions regarding some R&D and manufacturing subsidiaries in Europe (Ma & Overbeek, Reference Ma and Overbeek2015; McCaleb & Szunomár, Reference McCaleb, Szunomár and Drahokoupil2017). Fourth, reflecting the patterns of internationalization and organic growth described above, the older subsidiaries of Huawei tend to be located in less-developed countries, while the subsidiaries that are located in developed countries tend to be younger.

Data Collection

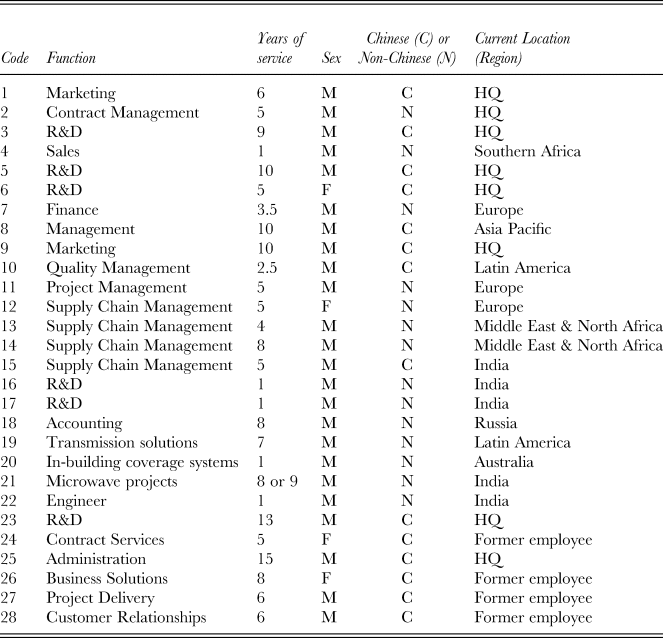

Data were collected through interviews and from documents. We shall explain the interview-based data collection part first, because most of this part was conducted before the document-based part. Altogether 28 semi-structured, one-on-one, face-to-face interviews were conducted with a mixed sample of Chinese and non-Chinese managers, each of whom was interviewed once. Some Chinese were former employees. Details of the interviewees are given in Table 1.

Table 1. Background of interviewees

A Chinese research assistant with an MBA degree conducted an initial round of interviews, each lasting around 20 minutes, with interviewees 1–17. He then conducted a second round of interviews, each lasting around 60 minutes, with interviewees 18–22. The first author, also Chinese, then conducted a third round of interviews, each of which also lasted 60 minutes, with interviewees 23–28. Both interviewers are fluent in English, and they conducted interviews in either Chinese or English, according to interviewees’ preferences. The second and third round interviews, given their longer duration, probed more deeply than those in the first round for explanations and elaborations.

Each interview was guided by a list of open-ended questions, which was adjusted over time (Brinkmann & Kvale, Reference Brinkmann and Kvale2015). Interviews began with demographics. Subsequent questions began with issues anticipated to be uncontentious, namely: How do the various parts of Huawei work together to identify customer needs and find affordable solutions? Please can you explain the roles of the HQ and the various types of subsidiary? Please can you explain the key policies regarding expatriates? Please can you describe the culture of Huawei? These were followed by potentially more sensitive questions, namely: Comparing HQ and subsidiaries, which is more powerful? Why? What controls does the HQ deploy? How are they justified (legitimized)? How do the local subsidiaries or regional offices respond to such controls? In addition to posing the preceding questions, the second and third round interviews probed for critical incident stories (Chell, Reference Chell, Symon and Cassell1998) in conjunction with the following questions: Please explain if there have been any ‘difficult’ cases regarding controls? If an employee or group disagrees with an instruction or procedure, what happens? Have you ever observed or heard about power struggles? Please explain what happened? In your view, what steps, if any, should the company take in the future to empower the regional offices/local subsidiaries?

Considering the difficulty of obtaining formal consent for research in Chinese firms (Stening & Zhang, Reference Stening and Zhang2007) and at Huawei's HQ in particular (Chang, Ho, Tsai, Chen, & Wu, Reference Chang, Ho, Tsai, Chen and Wu2017), i.e., the so-called ‘bamboo curtain’ (Snell & Easterby-Smith, Reference Snell, Easterby-Smith, Campbell and Brown1991), informal access arrangements were made for the interviews. The first two rounds of interviews took place at an off-site hotel near to the Huawei HQ, which was regularly used for Huawei's conferences, meetings, and training sessions involving senior HQ-based executives, and expatriate managers and senior local staff from Huawei's overseas subsidiaries. At the hotel, the first interviewer, who had informal connections both to the hotel and to Huawei, approached potential interviewees, inviting them to take part in the study. He pointed out to interviewees that they had the right to refuse and to withdraw at any time, that the purpose was academic and sought to understand control mechanisms and HQ-subsidiary relationships within the company, and that their identities would be fully protected. He obtained interviewees’ explicit consent prior to interviewing them. Ethics approval was obtained from the second author's institution, which funded the research. Interviewees for the third round were obtained through snowball sampling (Handcock & Gile, Reference Handcock and Gile2011), based on referrals by HQ-based interviewees, and were interviewed at convenient locations for them, such as quiet cafés, or (in the case of former Huawei employees) their current offices. All interviews were audio-recorded with interviewees’ consent and were transcribed in English by the respective interviewers.

These procedures yielded a heterogeneous sample of interviewees. Altogether, there were 8 people employed at Huawei's Shenzhen HQ, among whom 7 were Chinese. Another 16 people were employed at Huawei's overseas subsidiaries, with representation from all 7 Huawei regions outside the PRC. There were also 4 former Huawei employees. Overall, there were 14 Chinese and 14 non-Chinese informants, and a mixture of senior and middle-ranking employees, covering a wide range of functional specialisms. Together, the interviewees had aggregate experience of working at Huawei subsidiaries that were located in at least 23 countries, including India (7 people), Germany (6 people), France (4 people), Singapore (3 people), and the UK (3 people). Among those Chinese interviewees, who were currently based at the HQ, all had previously worked in at least one overseas Huawei subsidiary. This reflects that a career history of job postings within Huawei in multiple country locations is typical among Huawei's Chinese managers (Tao, Cramer, & Wu, Reference Tao, de Cremer and Wu2017).

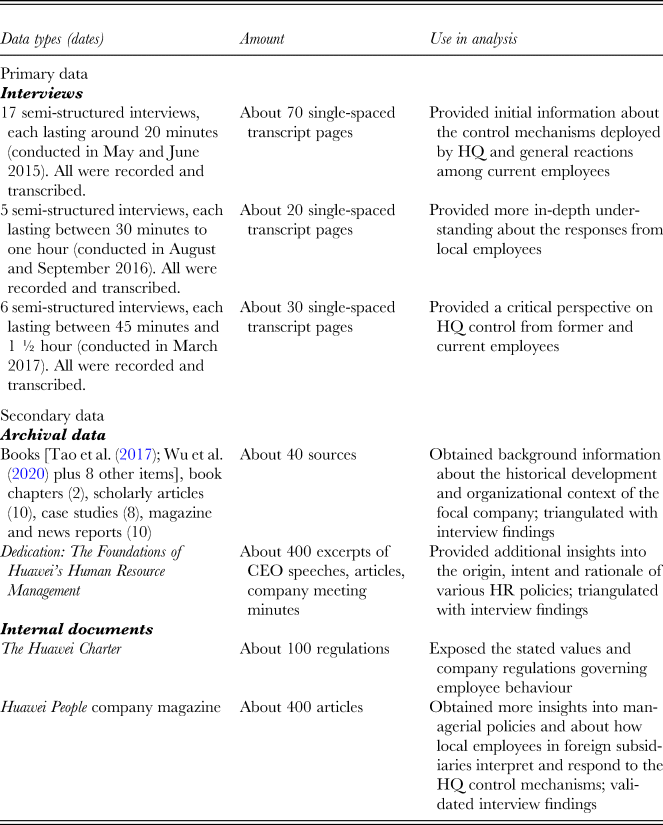

Another substantial portion of our data comprised documentary sources in English and/or Chinese that contain descriptions and characterizations of organizational controls and manifestations of legitimation within Huawei (see Table 2). Internal sources included issues 250–283 of Huawei People, a monthly company magazine available in English on the internet, covering 31 May 2014 to 30 September 2017. This is a channel for employees to share experiences, reflections, and ideas about working in Huawei, and for the CEO and other top managers and consultants to convey policy ideas and explanations. Another internal source was the book, Dedication: The Huawei Philosophy of Human Resource Management, compiled by Huawei's Executive Management Team (EMT) and available in English (Huang, Reference Huang2016). This book contains excerpts from speeches and letters by Mr. Ren Zhengfei and from meeting resolutions by the EMT. We also consulted the Huawei Charter, an internal document developed with the help of Chinese scholars in 1996–97 (Tao et al., Reference Tao, de Cremer and Wu2017), to understand the visionary framework that had been guiding the development of company policies and regulations. External sources are listed in our references section, and comprised independently written case studies, books, book chapters, scholarly articles, magazines, and newspaper reports about Huawei. Among these external sources were two company-facilitated books (Tao et al., Reference Tao, de Cremer and Wu2017; Wu, Murmann, Huang, & Guo, Reference Wu, Murmann, Huang and Guo2020), the former based on 136 interviews with current or former Huawei employees, and the latter a compendium of research articles on the managerial transformation of Huawei. In cases where particular sources were available only in Chinese, two Chinese research assistants, who had completed or were taking research postgraduate degree programmes, provided English translations of salient passages.

Table 2. Data sources

Data Analysis

Data analysis involved data reduction, categorization and subcategorization, the drawing of provisional conclusions, and data verification (Miles & Huberman, Reference Miles and Huberman1994). We began by inspecting the interview transcripts. Within these, data reduction involved highlighting for analysis only those passages that appeared related to headquarters-subsidiary relationships, the enactment or legitimation of managerial controls, and subsidiary-level responses to such controls. Through open coding (Corbin & Strauss, Reference Corbin and Strauss2015) we identified around two dozen first-order concepts and eight second-order themes within the highlighted portions of the transcripts. We then turned to the documentary data sources, with the exception of Tao et al. (Reference Tao, de Cremer and Wu2017), which we did not obtain until we had arrived at our provisional conclusions. We shall explain later in this section how we used Tao et al. (Reference Tao, de Cremer and Wu2017). The other documentary sources contained a large volume of material, and we performed a similar data reduction process before engaging in open coding. Besides confirming the concepts and themes arising from the interviews, our analysis of the documents generated three dozen additional first-order categories and a dozen more second-order themes, and with these in mind, we returned to the interview transcripts and identified some passages that required recoding.

We then examined the whole body of first-order concepts and second-order themes to see if they could be sorted into pre-existing conceptual frameworks. In particular, we were able to match the seven emergent categories of control mechanisms that we identified from our data as subcategories that served to enrich the broader framework of output controls, process controls, and social controls that Sageder and Feldbauer-Durstmuller (Reference Sageder and Feldbauer-Durstmuller2019) had already developed, based on their extensive review of studies of management controls in MNCs. After close inspection, we preferred to retain our own category labels for the control mechanisms as these were fine grained and had emerged from the data.

We were also able to locate our five emergent categories of legitimation as subcategories to enrich the categories within the broader Vaara and Tienari's (Reference Vaara and Tienari2008) typology, which includes rationalization, moralization, and mythopoesis (see also Van Leeuwen & Wodak, Reference Van Leeuwen and Wodak1999). In addition, we noted similarities and differences between some of our emergent categories of legitimation and categories of legitimation developed by Balogun et al. (Reference Balogun, Fahy and Vaara2019). Once again, we preferred to retain our own set of category labels where they differed from those of other scholars, not only because our categories were fine grained and had emerged from the data but also because the other typologies had been developed in contexts other than that of the legitimation of control mechanisms. We considered categorizing subsidiary responses according to West and West's (2006) three-category typology of behavioural reactions to corporate culture inculcation (supporters, compliers, and resisters), but in the end we preferred the simpler ‘boy scouts’ versus ‘subversive strategists’ dichotomy of Morgan and Kristenson (Reference Morgan and Kristensen2006).

Once our category systems had crystallized, we were able to arrive at a theoretically saturated understanding (Bowen, Reference Bowen2008) and moved to a conclusion drawing stage based on insights into ‘regularities, patterns, explanations, possible configurations, causal flows and propositions’ (Miles & Huberman, Reference Miles and Huberman1984: 24). This entailed visualizing and mapping the interdependencies between the various categories (Merriam & Tisdell, Reference Merriam and Tisdell2016), thereby building a theory of how Huawei's HQ has acted in order to maintain control over its subsidiaries without suppressing their resourcefulness, as we explain in our findings section.

In terms of epistemological foundations, our analytical approach was based on social constructivism (Creswell, Reference Creswell2013), also termed interpretivism (Merriam & Tisdell, Reference Merriam and Tisdell2016), through which we sought to appreciate the various cultural and institutional contexts that the interviewees and documentary sources were referring to. We sought to construct a full and coherent picture of control and legitimation within Huawei that was consistent with how the interviewees and authors of the documents that we analyzed were making sense of these phenomena. In constructing this holistic picture, our interpretations were also informed by our own pre-understanding (Gummesson, Reference Gummesson2000) of the role of control and legitimation in organizations, based on our theoretical sensitivity and extensive personal experience as organizational analysts, and open to modification and enhancement in light of the data we obtained.

Since this was qualitative research, we acknowledge that questions may arise regarding whether our interpretations are more plausible than alternative explanations (Cuervo-Cazurra, Andersson, Brannen, Nielsen, & Reuber, Reference Cuervo-Cazurra, Andersson, Brannen, Nielsen and Reuber2016), not least because of language differences and subsequent process of translation (Outila, Piekkari, & Mihailova, Reference Outila, Piekkari and Mihailova2019). With such challenges in mind, we adopted seven data verification procedures to establish that our interpretations are trustworthy and credible (Lincoln & Guba, Reference Lincoln and Guba1985). First, through data triangulation, we established that the patterns and meanings derived from the interview data were consistent with those from the documentary sources, which at that stage did not include Tao et al. (Reference Tao, de Cremer and Wu2017). Second, our sample of interviewees was heterogeneous in terms of functions, and included some individuals with extensive experience of several overseas subsidiaries. Third, the first author double-checked the English transcriptions to ensure consistency with the original tape-recordings and Chinese texts (Silverman, Reference Silverman2013). Fourth, when choosing examples for the findings section, we identified quotes that encapsulated the core meanings of the categories and conveyed the nuances of the subcategories. Fifth, the co-authors held regular meetings to discuss whether the transcript items had been accurately categorized and sub-categorized and could ensure inter-rater reliability (Hammersley, Reference Hammersley1992: 67). Sixth, regarding peer debriefing (Yin, Reference Yin1994), we shared our main interpretations with some of the third-round interviewees for verification and confirmation. Seventh, after our analysis was completed, we performed a close analysis of all the passages in Tao et al. (Reference Tao, de Cremer and Wu2017) that referred to controls, means of legitimation, and HQ-subsidiary relationships within Huawei, compared our own categorizations with the material therein, and confirmed that data saturation (Bowen, Reference Bowen2008) had been reached.

The main sub-section of our findings section, which follows, analyzes the control mechanisms that the HQ is using to control the subsidiaries. For each control mechanism, we provide explanations of key aspects of how the mechanism works along explanations of the strategy or strategies adopted for the legitimation of those key aspects. A short sub-section then describes apparent subsidiary-level responses against the backdrop of the HQ's expectations and demands. Throughout the findings section, when referring to interviewees 1–28, we shall also indicate whether they are Chinese (C), who were interviewed in Putonghua, or non-Chinese (N), who were interviewed in English, and whether at the time of interview they were employed at the Shenzhen headquarters (H) or at an overseas subsidiary (S), or were former Huawei employees (F).

FINDINGS

Control Mechanisms and Strategies Adopted for Their Legitimation

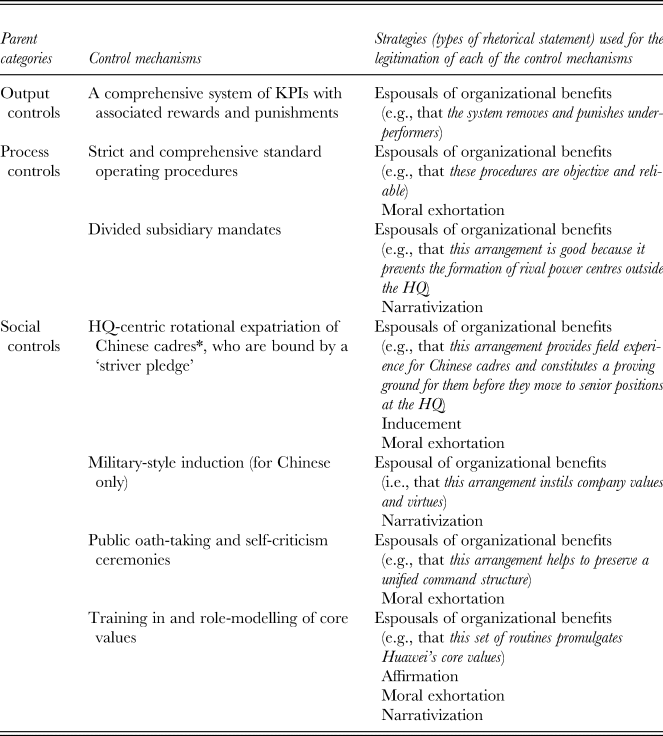

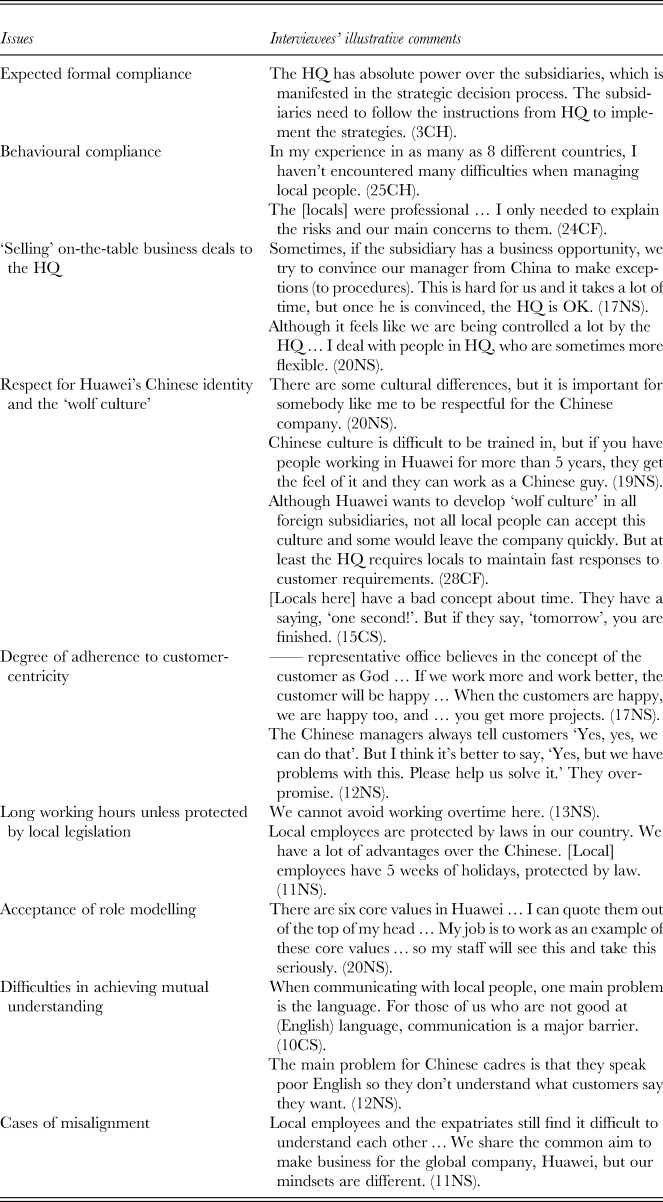

Inductively from our data, we distinguished seven HQ-originated control mechanisms that were being applied vis-à-vis Huawei's overseas subsidiaries. They are listed in column 2 of Table 3, and appeared to fall within the three parent categories of output controls, process controls and social controls of Sageder and Feldbauer-Durstmuller (Reference Sageder and Feldbauer-Durstmuller2019), which are listed in column 1 of Table 3. We shall explain column 3 of Table 3 after explaining the content of Table 4, which we do next.

Table 3. Control mechanisms in Huawei and corresponding strategies of legitimation

Note: *Cadres also support output and process controls

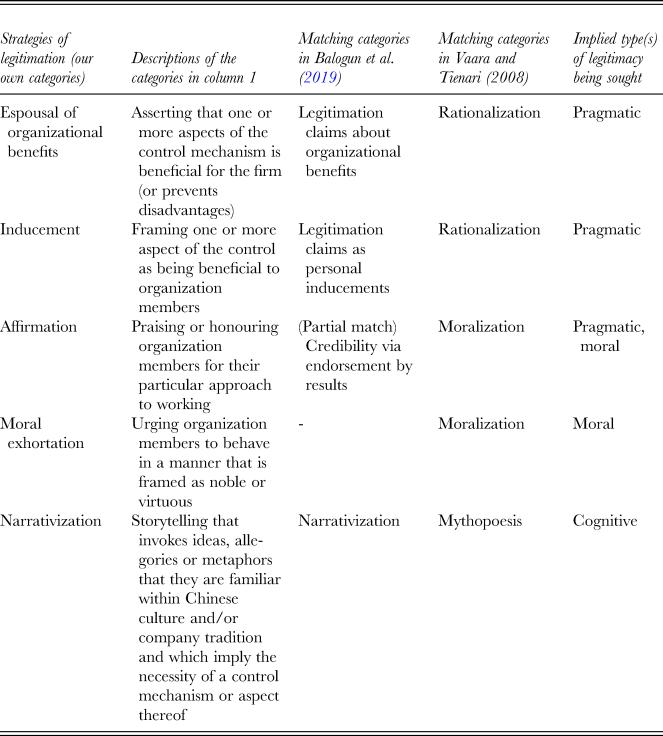

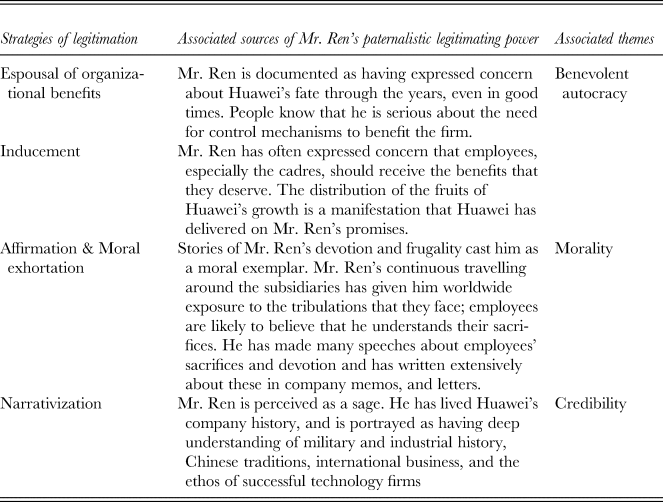

Table 4. Strategies of legitimation and the types of legitimacy being sought

Inductively from our data, we distinguished five strategies that were being employed as rhetorical means for the legitimation of the control mechanisms. These legitimation strategies are listed in column 1 of Table 4, alongside our definitions thereof in column 2 of Table 4. Column 3 of Table 4 maps our five strategies of legitimation against the typology of Balogun et al. (Reference Balogun, Fahy and Vaara2019). While there are some correspondences between the five legitimation strategies that we identified and those of Balogun et al. (Reference Balogun, Fahy and Vaara2019), there are differences with respect to our categories of affirmation and moral exhortation. Column 4 of Table 4 maps our five inductively distinguished strategies of legitimation against the typology of Vaara and Tienari (Reference Vaara and Tienari2008). Among our inductively distinguished strategies of legitimation, two, namely inducement and espousal of organizational benefits, fall within Vaara and Tienari's (Reference Vaara and Tienari2008) broader category of rationalization; another two, affirmation and moral exhortation, fall within Vaara and Tienari's (Reference Vaara and Tienari2008) moralization; while our fifth category, narrativization, corresponds to Vaara and Tienari's (Reference Vaara and Tienari2008) mythopoesis. Column 5 of Table 4 identifies the types of legitimacy (Suchman, Reference Suchman1995) that each of our five inductively distinguished legitimation strategies appears to target. Among them, espousal of organizational benefits and inducement appear to seek pragmatic legitimacy, affirmation appears to seek both pragmatic and moral legitimacy, moral exhortation appears to seek moral legitimacy, and narrativization appears to seek cognitive legitimacy.

Returning to Table 3, we shall next explain the pattern of usage by Huawei's HQ of the strategies of legitimation as rhetorical statements in support of the various control mechanisms. This pattern is indicated in column 3 of Table 3. Among the strategies of legitimation, espousals of organizational benefits were prevalent and were used to support all seven control mechanisms. The associated espoused benefits tended to refer to anticipated outcomes for the organization as a whole rather than for subsidiaries per se. For example, the control mechanism of divided subsidiary mandates was legitimized as an arrangement that prevents the formation of rival power centres outside the HQ, indirectly implying common good for the organization. Another example is that the control mechanism of HQ-centric rotational expatriation was legitimized as a means for providing field experience for the cadres (a centrally recruited stratified echelon of leaders), and as a proving ground for them, implying common good for the organization while appealing to centrally recruited cadres, engaged in rotational assignments across the subsidiaries.

In the rest of this section, we explain and illustrate the seven control mechanisms in the sequence indicated in column 2 of Table 3, while in the process offering further explanations and illustrations of the five strategies that were being used for their legitimation.

Control mechanism 1: KPIs linked to rewards

Huawei's key performance indicator (KPI) system applies at all levels and within all functions and projects at each subsidiary. Although cadres stationed at the subsidiaries can negotiate with the HQ about their KPIs, the system is driven by the HQ, and cascades down the line. Interviewees perceived that their own performance against KPIs was being closely monitored by the HQ, and that the ensuing rewards or sanctions (including potential demotions and pay cuts) were reinforcing accountability by reflecting measured performance. For example:

We are under the management of the HQ. . . Our operations are dictated by various KPIs on a yearly, quarterly, monthly or even daily basis. (15CS)

Interviewees indicated, accordingly, that the KPI system not only generates pervasive performance pressure at each sales/service subsidiary, but also enables the HQ to pinpoint areas for improvement. For example:

If some subsidiaries are poor at project delivery, they need to be re-assessed on their project delivery time and quality compliance in order to improve the overall standards of operation. (9CH)

Rhetorical statements of legitimation for the KPI system involved the espousal of organizational benefits, including this one about the alignment of personal and company interests:

We focus on results and responsibilities during appraisals, and jointly share the pressures arising from market competition. (Work Report to the Board of Directors Regarding the Completion of the 2003 Business and Budget Goals, 2003, quoted in Dedication, section 2.2.2)

Control mechanism 2: Standard operating procedures (SOPs)

External sources indicate that Huawei's system of SOPs, introduced in 1998, was based on extensive consultancy by Western consultancy firms, especially IBM, and encompasses all functions (Chen, Reference Chen2007; Sun, Reference Sun2009: 145; Sun & Zhang, Reference Sun and Zhang2015; Tao et al., Reference Tao, de Cremer and Wu2017; Zhang & Wu, Reference Zhang, Wu and Petti2012: 112–115). Tao et al. (Reference Tao, de Cremer and Wu2017) point out that before being finalized, the associated systems had been systematically piloted and refined to address the concerns of users. Interviewees indicated that the HQ owns the SOPs, that these are typically electronically embedded, and that subsidiaries cannot waive them without the HQ's approval. While local cross-functional teams are given autonomy in terms of arranging deals with local customers, they must operate within the boundaries of authorization and seek cooperation from regional and global HQ offices. The information systems of the subsidiaries are richly integrated with those of the HQ (Li, Chang, & Guo, Reference Li, Chang, Guo, Wu, Murmann, Huang and Guo2020), enabling close monitoring by the latter. For example:

There are specific steps to follow… Huawei's system is standardized throughout the world. (26CF)

Everything you do will be monitored by the IT systems. Huawei has invested a lot of effort to develop a system and has created a lot of steps for us to follow … So I think the information system has been designed to control what the employees are going to do. (11NS)

Rhetorical statements of legitimation for the SOP system often involved espousals of organizational benefits and typically emphasized the importance of efficiency and objectivity. For example:

These systems are all methodologies … They can help us remove unnecessary layers, and streamline our process from end to end, thus making our company less reliant on individuals. This is the most cost-effective and efficient approach’. (Ren Zhengfei, Living with Peace of Mind, 2003, quoted in Dedication, section 4.5.1)

Huawei's approach to adopting systems and procedures developed by external consultants has followed the initial pattern of absolute adherence, with subsequent incremental adjustments only permissible after an observation period stretching over many years (Murmann, Reference Murmann, Wu, Murmann, Huang and Guo2020a). Statements of legitimation for the SOP system introduced by IBM involved moral exhortation by Mr. Ren, implying that the SOP system was so important that it was worth making personal sacrifices in adhering to it:

We would like every one of you to wear a pair of American shoes. We will let out American advisors to tell you what American shoes look like. You may wonder whether the American shoes can be adapted. Well, we have no right to change anything. This is at the discretion of the advisors. (Ren Zhengfei, circa 1997, quoted in Tao and Wu [Reference Zheng, Luo and Maksimov2015: 163–164])

If you think the IBM shoes pinch your feet, then cut your feet off. (Ren Zhengfei, quoted in Tao et al. [Reference Tao, de Cremer and Wu2017: 314])

Control mechanism 3: Divided subsidiary mandates

Huawei's HQ slices and dices the mandates of subsidiaries in ways that appear to be designed to forestall the rise of power nodes at the periphery, which might otherwise emerge to challenge the authority of the HQ. We explain three key aspects of the division of subsidiary mandates in Huawei and how they are legitimized. The first is that Huawei's local representative offices for sales/service operate separately from Huawei's local R&D units, even if these entities are close geographic neighbours. Because the sales/service subsidiaries lack an R&D function, they depend on a superordinate platform for product improvements. Conversely, without a sales function, the R&D subsidiaries cannot transact business without intermediation by a superordinate platform for financing. As an interviewee from an R&D unit commented:

HQ is more powerful than we are … All customer orders come from HQ, and we can't generate any business ourselves … which prevents us from being powerful. (17NS)

Another interviewee encapsulated the role of the sales/service subsidiaries:

The subsidiaries just have to do their business well. Just like in this coffee shop the waiters just have to sell the coffee. (25CH)

The second aspect of the slicing and dicing of subsidiary mandates is that the reporting lines of the local sales/service subsidiaries are kept separate from those of the R&D subsidiaries. For example, Huawei's Western European regional HQ for sales and service is in Düsseldorf, Germany (Huawei, 2017b) whereas each R&D site in Europe reports to the 5G research centre in Leuven, Belgium (Mobile Europe, 2015). This separation of sales/service functions from R&D at the regional level appears to discourage the concentration of power at any of the regional offices, and to reinforce the dependency of the latter on central intermediation. Huawei thus appears to prefer to centralize authority rather than to allow regional or country-based autonomy in major policy-making.

It appeared that the following piece of narrativization by Huawei's Chief Management Scientist was an attempt to provide and maintain cognitive legitimacy for the strict separation of sales from R&D at both local and regional levels:

… As profit centers, Huawei's product lines and regional sales organizations are all incomplete in functions … One of the most notable characteristics of Huawei's management is that it achieves small-scale business organization by way of quasi-profit centers. This is an approach that is definitely at the forefront of the world's financial management. (Huang Weiwei, Mr. Ren's Bucket of Glue Theory (iii), in Huawei People, 283, September 2017: 28)

A third aspect of Huawei's division of subsidiary mandates is that the overseas R&D units, including 18 that are located in different European cities, focus on distinctive specialist domains (Huawei, 2014; Huawei, 2017a; Pang, Reference Pang2017). A statement of legitimation for this third aspect of the control mechanism of mandate division involved espousal of organizational benefits. This referred to the advantages arising for Huawei from capturing local talent pools for specialist research, and capitalizing on their external embeddedness:

Our microwave COE is a case in point. We found a leader in this field in Milan, and decided to build a team there especially for him … Milan is the home of microwave. It has abundant talent, a mature industry, and many universities with specialist labs in this field. (Ryan Ding, From Lone Heroes to Heroic Teams, in Huawei People, 275, February 2017: 4)

An additional arrangement (for which we could not find a legitimizing statement) that may have facilitated subsidiary mandate division is that Huawei's sales/service subsidiaries have been created through internal development (greenfield sites) rather than through acquisitions, as noted in the literature review. An interviewee commented:

Huawei never engages in M&A, because it has a very unique culture. It would be difficult for Huawei to manage acquired firms. Huawei built all the subsidiaries itself, even the unrelated businesses. (24CF)

Control mechanism 4: HQ-centric rotational expatriation of Chinese cadres

As is stated in external secondary sources (e.g., Chen, Reference Chen2007; Sun, Reference Sun2009; Tao et al., Reference Tao, de Cremer and Wu2017), the HQ directly appoints members of a stratum of Chinese leaders, whom we have referred to as cadres, to management positions at the subsidiaries on a rotational basis. Within a given subsidiary, while junior and middle-ranking cadres perform functional specialist duties, the senior cadres normally occupy the highest line management positions. An interviewee pointed out that the incidence of non-Chinese senior managers (as opposed to senior R&D specialists) is rare in Huawei's overseas subsidiaries:

So far, in the whole of Huawei, we have just two non-Chinese as VPs, and both are in Europe. The CEO of Czechoslovakia is Polish, and the CEO in Belgium is Portuguese. (25CH)

By way of legitimation for the Chinese-dominated aspect of HQ-centric rotational expatriation, Mr. Ren has provided an argument based on espousal of organizational benefits. He implicitly argued that such rotational experience in the sales/service subsidiaries equips the Chinese cadres to operate more effectively when they eventually return to the HQ and, in turn, acquire centralized authority there:

We will not allow those who have never worked in field offices to sit at the HQ and give directions to field offices. All managers should go to work in field offices and (learn to) solve real-world problems. (Ren Zhengfei, Building a Professional Financial Team That Has Solid Integrity, Dares to Shoulder Responsibilities, and Stick to Principles, 2006, quoted in Dedication, section 6.1.1.)

Cadres on expatriate duty regularly return to the HQ for briefings and are stationed at any given subsidiary for around three years before being sent back to the HQ or on to other subsidiaries. They owe their primary allegiance to the HQ, while serving as key managerial resources at the subsidiaries. Supervision of the subsidiaries by the HQ is thus based on the rotational expatriation of cadres, for the purposes of testing, developing, and exploiting the managerial capabilities of the cadres, who are ‘loaned’ to the subsidiaries. The senior cadres at each subsidiary engage in the person-to-person instruction and monitoring of staff there, while remaining in close contact with the HQ. Besides accumulating and disseminating HQ-based expertise, senior cadres on rotation are expected to perform three other embedded agency roles (Battilana & D'Aunno, Reference Battilana, D'Aunno, Lawrence, Suddaby and Leca2009). The first of these roles appears to be to serve as ‘cultural diplomats’ (Loveridge, Reference Loveridge2005: 397), who promulgate and uphold HQ-originated norms and values (especially vis-à-vis more junior Chinese staff, who are also on rotation). As expressed by an interviewee:

Our Huawei CEO has conveyed to us that [in the subsidiaries] we must rely on our veteran employees, who are so called ‘strivers’, sharing the same thoughts … Power would not be given to local people because we don't trust them. (25CH)

Mr. Ren has used moral exhortation as a means for legitimizing the cultural diplomat role of the cades on rotation:

Passing our corporate culture down to subordinates is the responsibility of managers at all levels. If our managers can't understand our culture, it will be impossible for them to pass it to others. (Ren Zhengfei, Having a Sense of Service and Branding, and Showing Team Spirit, 1996, quoted in Dedication, section 4.1.3.)

Interviewees indicated that a second role of the cadres on rotation at the subsidiaries is to ensure that the HQ-originated policies, procedures and standards are implemented properly, and that resources are allocated within the subsidiary in accordance with the priorities and criteria set by the HQ:

Their [cadres’] job is to help the subsidiary follow the overall strategies set by the HQ and ensure that those policies will be fully executed. (4NS)

Huawei is a centralized company. In general, we have to come to the HQ for any important decisions, such as finance, staffing or other issues related to project control. (17NS)

As a means of legitimation, Mr. Ren espoused the organization benefit of this second, directive role of the cadres on rotation as follows:

We should not discuss corporate policies with employees, which may whet their appetites. We only need to explain policies to them … We must ensure that our corporate policies are not changed arbitrarily. (Ren Zhengfei, Speech at the EMT ST Meeting, 2009, quoted in Dedication, section 2.1.12)

The third role of cadres on rotation is to serve as ‘battlefield generals’ (a term coined by Mr. Ren), who are entrusted by the HQ to provide accurate and useful ‘battlefield intelligence’, which is especially salient if the cadres request additional help from specialists located at the HQ, or ask for additional headcount (‘reinforcements’) beyond the budgets originally allocated by the HQ:

If the subsidiary needs to convince HQ to give them more resources, you need to go through the subsidiary manager [top cadre there] first. (26CF)

A statement of legitimation for this third, commando in-charge role was conveyed in the form of narrativization by Mr. Ren, who invoked a military metaphor of the kind that organization members would be familiar with, given the emphasis on military metaphors and stories in Huawei People:

Under the new governance model, those who can hear the gunfire call for support; frontline organizations have both responsibilities and authorities; and corporate functions provide enablement and supervision. (Ren Zhengfei, Letter from the CEO, in Huawei, 2013: 8)

An additional aspect of the rotational expatriation of Chinese cadres is that the latter are bound by a ‘striver pledge’, which they are required to sign early in their career. This is a contractual agreement, through which the cadres waive their rights to overtime pay and to other protections and entitlements, such as a say in where they will be stationed, in exchange for career opportunities and membership of Huawei's employee share ownership scheme. Interviewees explained:

I signed the striver pledge, requiring me to forfeit paid holidays and to follow the company's staff assignment policy. On one hand, you have to give up your personal interests, but you can also share the company profits in return. (28CF)

(As a cadre) the company could ask you to go everywhere and rotate your position … Anyone could be rotated to any of the 170 plus subsidiaries. (24CF)

An alternative name for the striver pledge is ‘dedicated employee agreement’ (Osawa, Reference Osawa2016). It obliges cadres to accept and execute all assignments that are given to them. While Su and Chen (Reference Su, Chen, Su and Chen2014: 76) claimed that the Huawei cadres ‘develop a sense of duty and absolute obedience to their superiors’, implying a chain of command extending from the HQ into the subsidiaries, expectations about cadres’ obedience are less strict in contemporary Huawei (Tao et al., Reference Tao, de Cremer and Wu2017). Cadres nonetheless must accept all challenges assigned to them, as indicated by these interviewees:

(Unlike locals) the Chinese employees can't refuse their supervisors and managers. It is impossible for them to say ‘no’ to the boss, or they will be fired. (7NS)

(As a cadre) your superior can decide your fate in the company, so Huawei is a leader-centric company with the leader as the focal point … They demand absolute obedience from their subordinates. So that is why they have such a high level of execution. (28CF)

In statements designed to legitimize the striver pledge, Mr. Ren embraced the legitimation strategy of inducement:

When the business is good, their (the strivers’) income will be very high. (Ren Zhengfei, Speech at a Meeting with the IFS Project Team and Staff from Finance, 2009, quoted in Dedication, section 3.2.9.)

We value the contributions of dedicated employees and reward them accordingly. (The Second Coaching Report on Huawei's Charter, 1998, quoted in Dedication, section 3.3.2.)

Mr. Ren also espoused the organizational benefits associated with the striver pledge, as below:

Key employees are those the company can rely on during its development, especially during times of crises or major internal and external events. They share in both the company's successes and failures and remain dedicated in whatever positions they assume. (EMT Meeting Minutes No. [2008] 006, quoted in Dedication, section 6.4.1.)

Control mechanism 5: Military-style induction

Huawei's HQ has sought to inculcate norms, codes, and values into potential cadres at the very beginning of their Huawei careers. According to external secondary sources, the firm has a long-standing tradition of providing military-style induction for newly recruited Chinese graduates (Osawa, Reference Osawa2016). New Chinese recruits undergo a month of military training (Su & Chen, Reference Su, Chen, Su and Chen2014: 76; Sun & Zhang, Reference Sun and Zhang2015), plus another ‘two weeks of cultural indoctrination on the Shenzhen campus’ (The Economist, 2011). Referring only to this home-country arrangement and not to the induction of non-Chinese employees, Su and Chen (Reference Su, Chen, Su and Chen2014: 76) claimed that ‘Huawei implants its corporate culture in new recruits to override other learned behaviours’. According to Tao et al. (Reference Tao, de Cremer and Wu2017: 199), ‘“Brainwash” isn't really the right word because the company does more than that; perhaps “brainswap” is more appropriate’. They elaborated as follows:

Having gone through various training sessions on the values that drive their daily work, almost every one of them (Huawei's Chinese employees) has undergone a transformation. Every cell in the Huawei organism is trained to be customer-centric. (Tao et al., Reference Tao, de Cremer and Wu2017: 33–34)

Taken together, these sources imply that the early socialization of those who become Huawei cadres matches van Maanen's (Reference Van Maanen1978) categories of being intense, formal, collective, serial, and divestiture-based. The aim appears to be to transform them into a disciplined army under unitary command. As one interviewee stated:

As soon as you are recruited, the brainwashing process begins. My boss used to tell me that he could find strong traits of Huawei in me. (26CF)

A key statement offering legitimation for Huawei's military style induction of potential cadres involved narrativization:

As the old Chinese saying goes, ‘A valiant general always starts as an ordinary soldier, just as a prime minister always starts as a local official’. (Ren Zhengfei, A New Year Message for 2010, quoted in Dedication, section 6.1.1)

In our analysis of articles in Huawei People, we found some stories about past ‘struggles’ that cast the marketplace around Huawei as a ‘battlefield’. Such articles may also have been used for a strategy of narrativization in seeking cognitive legitimacy for military style induction. In addition, articles in earlier editions of Huawei People that were outside the scope of our own analysis, i.e., prior to May 2014, appear to have cast military-like struggles as part of a wider narrative of Huawei as a Chinese organization seeking to redress more than a century of perceived foreign domination and repression (Lai et al., Reference Lai, Morgan and Morris2020).

Control mechanism 6: Public oath-taking and self-criticism ceremonies

Since 2007, the senior and middle-ranking cadres in every HQ department and subsidiary have been required to participate in oath-taking and self-reflection ceremonies (Hawes, Reference Hawes2008; Hawes & Chew, Reference Hawes and Chew2011; Tao et al., Reference Tao, de Cremer and Wu2017). Some middle-ranking local employees may also participate. Articles in Huawei People, such as the one from which the extract below is taken, contain photographs and reports of the ceremonies, and have set out the protocol of such ceremonies:

The Western European Region Management Team (MT) read and discussed the eight principles for managers at its 2017 annual meeting … At the meeting, managers also identified gaps between their own work ethic and the standard required by the eight principles, and reflected on the shortcomings in their work. After the discussion, the MT members took a solemn oath, expressing their determination to firmly adhere to the eight work ethic requirements for managers … Similar meetings were also held by the management teams of (Business Groups) and representative offices in Western Europe. (Discussion of the Eight Principles and Oath to Improve Work Ethic, in Huawei People, 276, March 2017: 38)

Liu (Reference Liu2015) has suggested that a key function of oath-taking and self-criticism ceremonies at Huawei is to maintain unity and avoid friction (196). Indeed, this potential organizational benefit corresponds to one of the eight principles alluded to in the extract given immediately above. Principle no. 8 is given below:

No. 8. We will not allow the act of taking sides or forming cliques to gain foothold at Huawei. (Oath-taking: Eight Principles for Managers, in Huawei People, 275, February 2017)

In a set of statements providing legitimation for these ceremonies, Mr. Ren has offered moral exhortation for managers to engage in self-criticism and self-reflection and has claimed as an organizational benefit that the associated conceptual processes have helped to prevent Huawei's demise:

We should ask managers to first criticize themselves, and then let others judge if they can pass. Managers must be open-minded, accept criticism from others, and engage in self-reflection. (Ren Zhengfei, Speech at the Communication Meeting with the Steering Committee on Self-reflection, 2006, quoted in Dedication, section 5.7.1.)

Without self-reflection … we … would not have survived in this volatile and competitive market. Without self-reflection, we wouldn't have been able to introspect, motivate ourselves, and boost team morale in the face of crises. (Ren Zhengfei, Anyone Who Climbed Out of the Pit of Setbacks is a Saint, 2008, quoted in Dedication, section 4.1.1.)

Control mechanism 7: Training in and role-modelling of core company values

Referring to an earlier era in Huawei's development when the firm was aggressively embarking upon foreign expansion, several external sources have referred to Huawei's ‘wolf culture’ as an encapsulation of the firm's approach to seizing business opportunities (Chen, Reference Chen2007; Hawes, Reference Hawes2008; Su & Chen, Reference Su, Chen, Su and Chen2014; Sun, Reference Sun2009; Zhang & Wu, Reference Zhang, Wu and Petti2012). This metaphor remains part of the company folklore, as indicated in the following quotes:

If I can use a few words to describe Huawei, I will first use ‘wolf character’. In English we may use ‘aggressive’ or related adjectives. Once they set an objective, everyone from top to bottom will work together to achieve it by whatever means. (28CF)

Someone once said to me that to work at Huawei you need to be aggressive like a wolf, so it's a good thing that I'm a wolf, too. (Italian head of Milan Research Centre, Huawei Built a Research Lab Because of Me, in Huawei People, 272, October 2016: 7–14)

As legitimation for the ‘wolf’ aspect of the core value system of the company, Mr. Ren has, in the past, provided moral exhortation to participate in the wolf culture:

To expand, an enterprise must develop a wolf pack. Wolves have three key characteristics, a keen sense of smell, a pack mentality and tenacity. We must create an environment that encourages employee dedication. When opportunities emerge, a group of leaders will stand out and seize them. (Ren Zhengfei, How Long Can Huawei Survive?, 1998, quoted in Dedication, section 1.4.3.)

Mr. Ren's (Reference Ren2012) speech, The Spring River Flows East, involves role modelling and narrativization about extreme dedication and self-sacrifice. In the speech, Mr. Ren describes having suffered nightmares, depression, and two cancer operations associated with the stress of dealing with a particularly challenging period in the company's history. Nowadays, however, rather than advocating wolf-like aggressiveness, Huawei's internal communications emphasize the values of more moderate applications of customer-centricity, dedication, and perseverance (Tao et al., Reference Tao, de Cremer and Wu2017). These core values are mentioned alongside self-reflection in the 2016 annual report (Huawei, 2016). As explained below, these values have formed the basis of training sessions for local employees at Huawei's subsidiaries:

Recently I have been the project lead on the core values for Huawei Africa. We did a roadshow holding ten sessions across the region. I had taken people through various case studies of how Huawei core values are used in our day to day lives. I also do regular training on the company's core values. (Local Senior HR Manager, Huawei South Africa, Ambassadors of the Core Values in Huawei People, 279, June 2017: 10–11)

Mr. Ren has in recent times pointed out that not all Huawei people need to be ‘wolves’. In a statement of legitimation for the complementary role of ‘Bei’ within the core value system of the company he adopted the twin strategies of narrativization and moral exhortation:

Our young employees should be full of drive and ambition, like wolves; but at the same time, we should also allow other employees to work slowly and carefully, like the Bei, a legendary animal from Chinese folklore … The most effective organization is one that has wolves and Bei cooperating closely. (Ren Zhengfei, Firm Belief and Strong Focus Lead to Greater Success, in Huawei People, 263, January 2016: 6)

Role models are an additional channel for conveying Huawei's core values to local employees and have been the basis of many articles in Huawei People that feature local employees at overseas subsidiaries. Their stories exemplify Huawei's core values of customer-centricity, dedication, and perseverance. Such articles embrace the strategies of affirmation and moral exhortation in providing legitimation for Huawei's core values and for the role models of those core values. Extracts are given below:

We are here to deliver value to our customers, and the customer's success is Huawei's success. Living this core value is the engine driving me forward. (Local employee in Egypt rep. office, Matching My Customer Anywhere, in Huawei People, 276, March 2017: 18–19)

(In wartime Libya) our local employees formed into two groups – one stayed in Tripoli to maintain the government's networks, while the other went to Benghazi to maintain the networks of the opposition forces. Networks in other cities were maintained by Chinese staff we'd deployed locally … We are not afraid of sacrifices and have demonstrated our responsibilities to our customers. (Meeting Minutes: An Insight, An Idea with Ren Zhengfei, in Huawei People, 256, February 2015: 1–7)

Another manifestation of affirmation as a strategy for the legitimation of the contribution of role models as a means for conveying the core values has been the worldwide institution of Huawei's ‘Future Star’ Award (Tao et al., Reference Tao, de Cremer and Wu2017), under which employees can be nominated by their peers to receive a badge that honours them as a role model of company values. Around half of all Huawei employees have received this award:

The Future Star Award aims to encourage every employee to identify their role models, strive for excellence, and make continuous progress … In Future Star I and II, more than 66,988 Future Stars were selected … This year, … 36,003 employees have been awarded the honour. (Future Star Award III: Ongoing Event, Non-stop Inspirations, in Huawei People, 276, March 2017: 15)

Mr. Ren has provided further moral exhortation in support of role modelling as a means of instilling core company values:

Don't think that our spiritual culture is just empty talk. It is about holding up role models to guide the team forward … people who have contributed to the company … Look at the role models around you. Benchmark yourself against them and learn from them! (Minutes of a Meeting Between Mr. Ren Zhengfei and the General Manager and Other Managers of the China Region, in Huawei People, 281, July 2017: 2–5)

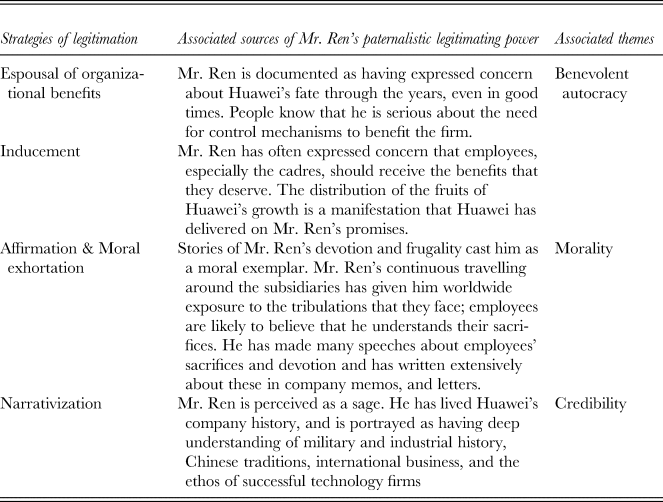

The importance of Mr. Ren as an agent of legitimation

Mr. Ren has sought to confer legitimacy to all seven control mechanisms explained above, whether through the legitimation strategies of inducements, espousals of organizational benefits, moral exhortation, affirmation, or narrativization. External sources have claimed that Mr. Ren's power to provide legitimation derives from his charisma (e.g., The Economist, 2011; Li, Reference Li2006, Tao et al., Reference Tao, de Cremer and Wu2017), his unique referent power as the founder of Huawei, and his right to veto decisions of the Board of Directors (Smith, Reference Smith2016; Tao et al., Reference Tao, de Cremer and Wu2017). One source of Mr. Ren's legitimizing power is that he has regularly disseminated his letters and texts of his speeches to employees, often through Huawei People, and often these communications are about practices that he has observed in the subsidiaries. It appears that Mr Ren is acutely aware of the power of his speeches and letters as vehicles of legitimation. As quoted by Zhao et al. (Reference Zhao, Guo, Wu, Wu, Murmann, Huang and Guo2020: 81), ‘On average, each of his speech drafts has been revised more than fifty times before being delivered’. This painstaking attention to detail may have contributed to their impact. For example, an interviewee stated: