INTRODUCTION

In an increasingly global business world, organizations often look to management practices developed in other countries and cultures. One of the most serious concerns that organizations have when transferring these practices is whether their employees will find them relevant and, as such, adopt them in their work. To better capture the multiple challenges related to the transnational movement and adoption of management practices, researchers have increasingly used the concept of translation, defined as the modification that a practice undergoes when transferred into a new context (Boxenbaum & Pedersen, Reference Boxenbaum, Pedersen, Lawrence, Suddaby and Leca2009), with a particular emphasis on the various transformations and adaptations aimed at improving the fit with local socio-cultural and linguistic contexts (Brannen, Reference Brannen2004; Piekkari, Tietze, & Koskinen, Reference Piekkari, Tietze and Koskinen2019; Welch & Welch, Reference Welch and Welch2008; Westney & Piekkari, Reference Westney and Piekkari2019).

Explicit in this conceptualization of translation is the understanding that when management practices move across national contexts, they cross not only socio-cultural but also linguistic boundaries (Brannen, Piekkari, & Tietze, Reference Brannen, Piekkari and Tietze2014; Piekkari et al., Reference Piekkari, Tietze and Koskinen2019; Rovik, Reference Røvik2016; Schomaker & Zaheer, Reference Schomaker and Zaheer2014; Tenzer, Terjesen, & Harzing, Reference Tenzer, Terjesen and Harzing2017) and that each crossing presents some specific challenges. Despite the growing recognition that linguistic differences pose distinct challenges to the transnational movement of practices, translation research has paid little attention to these challenges, leaving us with a lack of understanding of the complex processes around the re-verbalization in a new language of the original definitions and terminologies attached to a practice (Piekkari et al., Reference Piekkari, Tietze and Koskinen2019).

Recent research on practice translation in the context of East European transforming economies has begun to address this gap and to shed light on the complex decisions regarding defining and naming the various terms that describe elements of a practice in ways that are meaningful for local users (Kuznetsov & Kuznetsova, Reference Kuznetsov and Kuznetsova2014; Outila, Piekkari, & Mihailova, Reference Outila, Piekkari and Mihailova2019; Tietze, Tansley, & Helienek, Reference Tietze, Tansley and Helienek2017). For instance, in their account of the translation of ‘employee empowerment’, a term specific to Western human resource management practices, Outila et al. (Reference Outila, Piekkari and Mihailova2019) describe how Russian managers and employees use proverbs to help define the local meaning of empowerment. In a similar context, Tietze et al. (Reference Tietze, Tansley and Helienek2017) emphasize the important role played by translators and consultants in defining the various terms related to Western ‘talent management’ practices in a way that renders them meaningful as a whole discursive system to local Slovakian companies. Overall, this line of research has made salient the diversity and complexity of translation strategies through which local definitions of foreign practices emerge.

Yet, even when a local definition emerges, it remains unclear whether the name of a practice – what in this study we call the label, under which the redefined practice becomes known locally – is important for the reception of the practice by the local audience, especially by the employees who are called to use it. Studies have been done that describe translations of foreign practices and make references to various elements of a practice being named either with a foreign label, that is, the original name of the practice transliterated in the local script, or with a new, translated label, and some of these studies have elaborated on the pros and cons of such decisions (de Souza & Pidd, Reference de Souza and Pidd2011; Kuznetsov & Kuznetsova, Reference Kuznetsov and Kuznetsova2014, Reference Kuznetsov and Kuznetsova2016; Tietze et al., Reference Tietze, Tansley and Helienek2017; Westney & Piekkari, Reference Westney and Piekkari2019). Some attention in this area has been given to a specific category of knowledge users, academics, noting their dissatisfaction with the quality of the transliterated (Holden, Kuznetsov, & Whitelock, Reference Holden, Kuznetsov and Whitelock2008) as well as translated (Kuznetsov & Yakavenka, Reference Kuznetsov and Yakavenka2005) managerial and business terms. To our knowledge, however, no research has dealt with the impact of a transliterated label versus translated label on the way in which the practice is received by its actual local users. The overall sense is that the key aspect in rendering a practice relevant to the local audience is establishing a local definition well-understood by this audience, but that once the definition of a practice is in place, labeling it with the original word or a translated word is inconsequential for the way in which the practice is used: ‘the important issue is the idea and not the name’ (de Souza & Pidd, Reference de Souza and Pidd2011: 62).

In this article we turn the above assumption into a research question and ask whether the perceived relevance of a foreign practice by employees also depends on whether the practice is labeled with the original foreign word or a local word; and, if that is the case, what mechanisms might explain this effect. In addressing this question, we follow recent calls to transcend disciplinary boundaries and to integrate insights from connected disciplines in order to shed light on new areas of language and translation in transnational settings (Brannen et al., Reference Brannen, Piekkari and Tietze2014; Tenzer et al., Reference Tenzer, Terjesen and Harzing2017), including the less researched area of practice relevance (Kuznetsov & Kuznetsova, Reference Kuznetsov and Kuznetsova2016).

Theoretically, we expand the existing organizational translation research in two directions. First, to formulate our hypothesis about the likely perception of a practice when presented under a foreign or a domestic label, we draw from translation studies, especially those conducted on the role of ‘foreignization’ (retaining as many elements as possible from an original) and ‘domestication’ (removing as many elements as possible from the original) in conveying translated meaning (Venuti, Reference Venuti1992/2019, 2008). Second, concerning the label, we use the concept of semantic fit – defined as the extent to which a chosen label conveys the intended meaning of a practice in the local linguistic context (Brannen, Reference Brannen2004, Schmitt & Zhang, Reference Schmitt and Zhang2012) – to further explore the mechanisms that might create differences in perception between foreign and domestic labels.

Empirically, we carried out a field experiment in two branches of a Russian bank that had just begun implementing practices related to Toyota's Lean Production System (LPS). We randomly assigned employees to one of two conditions: one in which they received a set of LPS-related practices under the Japanese label, transliterated with the Cyrillic alphabet and one in which the same set of practices had a translated Russian name. All survey respondents received the same set of definitions for the practices in the Russian language. We asked each employee to assess how relevant each practice was for their work. This research design allowed us to isolate the effect of the label from that of the definition and to test the effect of the label of a practice on the perceived relevance of that practice with a stronger causal model (cf., Eden, Reference Eden2017).

Our analyses show that, on average, employees assessed the LPS practices as less relevant when they were presented under transliterated Japanese labels, regardless of the common definition that accompanied both transliterated Japanese labels and Russian labels. However, the negative impact of the foreign label was mediated by the semantic fit of the label, suggesting that the sheer foreignness of a practice's label is less problematic for employees when the foreign label fits with the linguistic codes of the Russian language. When it disrupts these codes, the negative effect of this disruption is more important than the simple foreign sound of the label.

The article starts with a brief description of the LPS and its adoption by Russian businesses. Drawing from translation research, we then theorize the likely impact that labeling LPS practices with foreign Japanese or local Russian words might have on the perceived relevance of LPS-related practices by Russian employees, and propose specific hypotheses to test our theory. Next, we introduce the empirical setting and describe in detail our experimental design and analytical strategy. The final sections present our findings, point out the limitations of our analysis, and discuss the article's theoretical and practical contributions.

LEAN PRODUCTION IN RUSSIA

Toyota's Lean Production System is particularly interesting for examining the role of language in the transnational transfers of organizational practices because, unlike the majority of transnationally transferred practices, it is a rare case of a practice that originates neither in the Western culture nor in the English language. As the antithesis of mass production that had dominated the Western world in the first half of the 20th century, the introduction of LPS in organizations in the US turned the most widespread and taken-for-granted organizational practices and assumptions on their heads. Whereas the success of mass production was predicated on the maintenance of highly-specialized resources and slacks (e.g., inventory, repair space, extra equipment) to buffer the uncertainties of the production process, the main goal of LPS practices was to eliminate exactly these resources (MacDuffie & Krafcik, Reference MacDuffie, Krafcik, Kochan and Useem1992).

In its broadest understanding, LPS is a system of problem identification and problem solving practices (MacDuffie, Reference MacDuffie1997; Shah & Ward, Reference Shah and Ward2007; Spear & Bowen, Reference Spear and Bowen1999). LPS relies heavily on all employees’ initiative to identify the concrete instances of its problems and to apply its solutions appropriately. Given the active involvement of employees, for LPS to deliver successfully, adoption by management alone never suffices; employees’ understanding of the practices and their commitment to use the practices in their daily activity is essential.

Since the 1970s, LPS has diffused successfully, initially in the US and then around the world, due to a vast ‘translation ecosystem’ (Westney & Piekkari, Reference Westney and Piekkari2019) that grew around LPS. The ecosystem included translators, consultants, practitioners, and academics, as well a broad literature – both professional and academic – that helped define the meaning behind the various LPS practices (Hines, Holweg, & Rich, Reference Hines, Holweg and Rich2004). Although most organizations precisely define the LPS practices ‘in house’, the presence of a unifying knowledge network (Lean Enterprise Institute) has contributed to some uniformity in the definitions of various LPS practices. Furthermore, many of the original Japanese terms for describing LPS processes, such as muda, gemba, and kaizen, were adopted and, over time, have become part of the lean vocabulary worldwide (Womack, Jones, & Roos, Reference Womack, Jones and Roos1990; Womack, Reference Womack2013).

The Russian context is different from the other settings in which LPS has been studied in that no coherent ‘translation ecosystem’ (Westney & Piekkari, Reference Westney and Piekkari2019) has emerged, despite the fact that in the past two decades a wide range of Russian organizations across industries has been experimenting with a variety of LPS versions. The same incoherent approach to translation has been observed in Belarus (where the organization that we investigate in this study has a subsidiary). In contrast with the US, where academics at business schools played a role in the translation ecosystem by contextualizing LPS practices and explaining their relevance, academics in Russia and Belarus remained skeptical about the relevance of foreign management practices (Kuznetsov & Kuznetsova, Reference Kuznetsov and Kuznetsova2016; Kuznetsov & Yakavenka, Reference Kuznetsov and Yakavenka2005).

Lately, lean practices have received endorsement by the government and technical support from international consultancies (Bakatina et al., Reference Bakatina, Duvieusart, Klintsov, Krogman, Remes, Shvakman and Solzhenitsyn2009; Boltrukevich & Rabunets, Reference Boltrukevich and Rabunets2015). Despite this apparent enthusiasm for LPS practices, their actual adoption demands the kind of flexibility and proactivity that is at odds with the hierarchical and authoritative nature of traditional Russian organizational practices (Berliner, Reference Berliner and Berliner1988; De Vries, Shekshnia, Korotov, & Florent-Treacy, Reference De Vries, Shekshnia, Korotov and Florent-Treacy2005; Leitzel & Clarke, Reference Leitzel1997; Puffer, Reference Puffer1995). Moreover, some critics inside Russia have even questioned the suitability of the very concept of lean for Russia, their argument being that the logic of lean was natural for resource-poor Japan, but completely alien to Russia, with its abundance of land, water, and fossil fuels (Prokhorov, Reference Prokhorov2008). Thus, it is clear that if LPS is to be successfully implemented by Russian organizations, the process of translating its core elements for the Russian context should be carefully attended to in order to convey the local relevance of LPS practices. Overall, the variety of opinions regarding the suitability of foreignization versus domestication as translation strategies for LPS in the Russian context suggests that the cultural and linguistic fit of new practices is important and worth investigating in more detail.

HOW DO FOREIGN AND TRANSLATED PRACTICE LABELS MATTER?

When a new practice that has traveled across socio-cultural and linguistic boundaries is introduced in an organization, its specific terminology will represent as much of a novelty as the practice itself. To date, however, most translation research has focused on the complex work that goes into establishing the local meaning of a transferred practice, along with a definition well-understood by the local audience. Although the labeling of the various elements of a practice with original words or translated words is also an implicit part of the practice translation work, it has only received limited attention in the organizational translation literature (e.g., Piekkari et al., Reference Piekkari, Tietze and Koskinen2019; Tietze et al., Reference Tietze, Tansley and Helienek2017). Moreover, two basic questions have not been investigated until now: Does the choice of label (a transliterated original name versus a translated local name) affect the outcome of the translation, that is, the likelihood that organizational members find the practice relevant and use it? If the choice of label impacts the outcome, how does it do this? (See Rovik [Reference Røvik2016] on the overall paucity of studies that investigate translation outcomes.)

In explaining our reasoning behind the proposition that it matters which language is used to label the elements of a transferred practice, we draw from the concepts of foreignization and domestication (Venuti, Reference Venuti1992, 2008) recently introduced in the organizational translation literature to explain strategies for constructing the local meaning of imported practices (see also: Rovik, Reference Røvik2016; Westney & Piekkary, Reference Westney and Piekkari2019). Domestication refers to translation strategies whose aim is to alter the presentation of a practice to a local audience by removing as many of its foreign elements as possible in order that it conforms to the values, beliefs, and social representations of that audience. Presented with a well-domesticated version of a practice, the local audience encounters a variety of artifacts, including texts, whose meaning is ‘intelligible and even familiar to the target-language reader, providing him or her with the narcissistic experience of recognizing his or her own culture in a cultural other’ (Venuti, Reference Venuti1992: 5). Venuti argues that text translation strategies are affected by cultural politics, which reflect power relations between the culture of origin and the destination culture, and that preferences for domestication are reflective of situations in which the destination culture aims to affirm its dominance.

By contrast, foreignization refers to translation strategies that retain as many elements as possible from the original in the target context. This includes using foreign artifacts such as visual elements, foreign words and phrases, even if additional explanatory text is needed. A translation strategy focused on foreignization deliberately disrupts the socio-cultural and linguistic codes of the destination language (Venuti, Reference Venuti and Baker1998). The deliberate disruption is considered positive insofar as it creates awareness that the recipients enter another cultural context and thus need to be open to a new way of thinking.

Although the uptake on Venuti's work in organizational research is very recent, some studies have started describing instances of both strategies. One of the most thorough accounts of their use is Westney and Piekkari's (Reference Westney and Piekkari2019) description of the interplay between domestication and foreignization strategies in the introduction and spread of LPS practices in the US in the period 1970-1990. For instance, domestication was evident in the first phase, in which academics and consultants described Japanese management practices and their advantages, while at the same time emphasizing that high-performing American companies were similar in many respects with high-performing Japanese firms. In turn, foreignization was more evident in later stages, when the distinctiveness of LPS was established and a new terminology emerged to mark this distinctiveness. As a result, many of the Japanese original terms for describing LPS practices were adopted into the mainstream vocabulary and used actively by employees and managers, as well as becoming part of the written accounts of LPS (Westney & Piekkari, Reference Westney and Piekkari2019; Womack et al., Reference Womack, Jones and Roos1990).

An example of foreignization is described by Tietze et al. (Reference Tietze, Tansley and Helienek2017) in their account of translating ‘talent management’ practices in a Slovak company. In their study, the translator who organized training workshops for the Slovak participants used English labels, that is, ‘loan words’ from English, when discussing various components of the talent management system, but acknowledged that, due to previous discussions and examples, the labels were also infused with Slovak meaning. Accounts of foreignization are also available from studies in UK hospitals where LPS was introduced, with some suggesting that using foreign labels could be sometimes beneficial because it helps staff shift easier to new work practices (de Souza & Pidd, Reference de Souza and Pidd2011).

Domestication and foreignization strategies speak to our research, which aims to understand perceived relevance of new practices, because they offer insights into how local audiences might react to labels. In particular, foreignization via the use of original foreign labels conjures the representation of difference in status and expertise between the country in which a practice originates and the country into which the organizational practice is translated. Such a representation is more likely to trigger among members of the receiving audience reactions of devaluing the foreign practice and defending the status and importance of local practices and knowledge – a bias widely known as ‘not-invented-here’ (Antons & Piller, Reference Antons and Piller2015). This bias can be attenuated when members of the organization to which a new practice is transferred have exposure to the socio-cultural context of the organization in which the practice originates. Such an exposure strengthens the identification of the receivers of a new practice with the members of the organization in which the practice originates, thus easing the transfer of knowledge between the two parties (Gupta & Govindarajan, Reference Gupta and Govindarajan2000; Kostova & Roth, Reference Kostova and Roth2002). In contrast, when members of the receiving organization perceive themselves as culturally different and distant, they are less likely to believe that ideas coming from the others would be valuable or relevant (Reiche, Harzing, & Pudelko, Reference Reiche, Harzing and Pudelko2015).

Michailova and Husted (Reference Michailova and Husted2003) provide some evidence of such beliefs regarding the evaluation of knowledge coming from other countries. Although the opening of the Russian economy increased the exposure to foreign practices and familiarized organizational members with several foreign business terms (Kuznetsov & Kuznetsova, Reference Kuznetsov and Kuznetsova2014), the belief that practices based on Russian values and culture are at least worth preserving is still widespread in the business community (Michailova & Husted, Reference Michailova and Husted2003; Prokhorov, Reference Prokhorov2008; Puffer & McCarthy, Reference Puffer and McCarthy2011). We expect the same mechanism to be at work in our case: When LPS practices are presented under original Japanese labels that have been transliterated with the Cyrillic alphabet, a Russian employee will question their relevance more compared to situations in which the same practices are presented under Russian translated labels:

Hypothesis 1: Transliterated Japanese labels of LPS practices have a negative impact on the perceived relevance of practices by Russian employees.

Semantic Fit Mediation Effect

The extent to which a practice presented under a foreign label is likely to result in a lower perceived value compared to the situation in which the same practice is presented under a domesticated label might depend on the degree to which the foreign label fits with or disrupts the socio-cultural and linguistic codes of the destination language (Venuti, 2008). That an original word or phrase might not fit another linguistic context is not a new hypothesis in translation research; yet, despite its relevance, there are few transnational organizational translation studies that examine it (Brannen, Reference Brannen2004; Piekkari et al., Reference Piekkari, Tietze and Koskinen2019; Schomaker & Zaheer, Reference Schomaker and Zaheer2014).

Brannen (Reference Brannen2004) developed the concept of semantic fit for understanding successful and unsuccessful international transfers of business artifacts such as products, brands, or management practices. Semantic fit is the degree to which the image, name, or other representation of a business artifact conveys the artifact's intended meaning in the given socio-cultural context (Brannen, Reference Brannen2004: 602). By definition, semantic fit is high in the context of origin. However, when moved into a new socio-cultural and linguistic context, the link between an artifact's image or name and its original meaning can become loose or even break due to unintended connotations, thus lowering the semantic fit of that artifact.

For instance, Brannen describes how a well-known Disney character, Mickey Mouse, an image which at the origin (in the US) is associated with a certain trait (smart), when moved to a new context (Japan and France respectively) is linked with different traits (safe and reliable in Japan, a smart trickster in France). Similarly, a practice identified by a word or phrase – its label – that evokes a specific meaning in the context of origin might no longer convey the same meaning when moved into a new context, where words and sounds can be infused with unintended meanings despite the concerted efforts of its transferors (translators, consultants, academics, etc.) to provide definitions and explanations aimed to link the label and the intended meaning. Linguistic translation becomes an intercultural interaction which outcome depends on how the chosen words resonate with local audiences, given their specific socio-cultural expectations (Chidlow, Plakoyiannaki, & Welch, Reference Chidlow, Plakoyiannaki and Welch2014).

Likewise, organizational researchers have long argued that ‘sensemaking is about labeling’: The way in which organizational initiatives, practices, and events are labeled affects how employees understand them and then deploy them in their everyday activities and interactions. Deployable labels demonstrate considerable plasticity, in part, because they are socially defined and adapted to local circumstances (Weick, Sutcliffe, & Obstfeld, Reference Weick, Sutcliffe and Obstfeld2005: 411), which is more consistent with domestication as opposed to foreignization, in general, and with translation as opposed to transliteration, in particular.

Evidence from the international translation of brand names showed the prevalence of domestication strategies in brand naming (Francis, Lam, & Walls, Reference Francis, Lam and Walls2002) and the lack of semantic fit caused by foreignization (James, Reference James2014). Schmitt and Zhang (Reference Schmitt and Zhang2012) found that local consumers had ‘tacit linguistic intuitions’ that allowed them to quickly evaluate whether a brand name was appropriate for the kind of product presented: Potential consumers of a product or service who had linguistic expertise but no marketing or branding expertise were able to reach conclusions similar to those of marketing and branding experts with regard to the semantic fit of a brand. Unlike branding experts who can explain the fit and test it on consumers, non-expert native speakers sensed ‘intuitively’ when a brand name conveyed the meaning of a product or service as belonging to a certain category, e.g. medicine, soft-drink, banking, hotel, accounting. They were also able to identify semantic misfit: cases when the brand name linked to a category to which the product or service did not belong, e.g., a brand name for a drink evoking the image of a product from a non-beverage category.

Organizational members exercise the same intuition of semantic fit in the case of an organizational practice. Analyzing data from two change projects in large Scandinavian companies, Naslund and Pemer (Reference Naslund and Pemer2011) find that new labels assigned to organizational actors and events have to semantically fit with the organization's dominant story and language in order for the change project to succeed. Similarly, in brand research, when the foreign brand name – either the transliterated original name or a new translated one – triggers an association with a category to which the product does not belong, the customers will take longer to adopt the product or can even reject it (Brannen, Reference Brannen2004).

Studies provide abundant evidence of semantic misfit of foreign business and management terms in the Russian context caused by linguistic and socio-cultural challenges to adequately conveying their meaning (Holden, Kuznetsova, & Fink, Reference Holden, Kuznetsova, Fink and Tietze2008; Holden & Michailova, Reference Holden and Michailova2014; Kuznetsov & Kuznetsova, Reference Kuznetsov and Kuznetsova2014). In the case of our study, semantic fit is high if the labels of LPS practices, either Japanese or Russian, trigger among employees associations with the work and management domain to which organizational practices belong. On the contrary, if the label of an LPS practice triggers associations with other domains, semantic fit will be low. For instance, a native Russian speaker might not link the transliterated labels Muda and Mura – the Japanese names of two important LPS problem identification practices – with the domain of work and management, regardless of the actual definition standing next to the label. In fact, a native Russian speaker might notice that the two labels, when pronounced with the stress on the second syllable, connote with something akin to ‘fool’ and ‘bullshit’ which does not instill confidence in the labeled practice's relevance.

To summarize the arguments and evidence above, a transliterated label of an LPS practice is detrimental to the practice's perceived relevance to the degree in which its meaning in the context of origin gets lost in the context of destination or, in our terms, shows low semantic fit:

Hypothesis 2: The negative effect of a Japanese label on the perceived relevance of a practice is mediated by the semantic fit of the label.

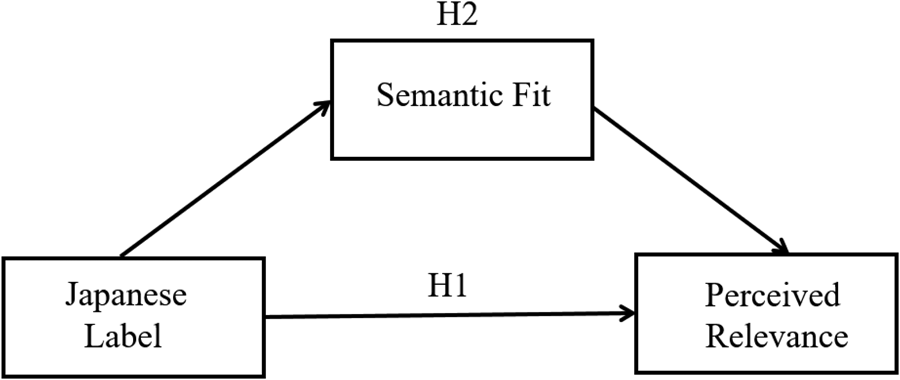

Table 1 summarizes the concepts, theoretical arguments, and empirical findings from the extant literature that we used in support of our two hypotheses derived above and presented graphically in Figure 1.

Table 1. Summary of references cited in the theoretical section

Figure 1. Theoretical model of the impact of label on perceived relevance

STUDY DESIGN

Setting, Sample, and Experiment

In 2011, the bank under study launched a major rollout of LPS and established lean laboratories for piloting them. The rollout began in Russia in the spring and spread to the bank's subsidiary in Belarus in the fall. In the spring of 2012, we carried out a survey of the employees’ perception of the relevance of LPS practices at two branches: in the city of Yaroslavl, the administrative center of one of Russia's 86 regions, and at the Minsk branch of the bank's Belarussian subsidiary. While at the time of the experiment the definitions of various LPS-related practices were already established at the organizational level and known by employees via training, the decision regarding labeling these practices with Japanese or Russian words was still in progress.

The working language at both branches was Russian. All of the employees at each branch constituted the survey population. A total of 163 out of 302 employees at the Russian branch and 142 out of 212 employees at the Belarussian branch who answered all the survey questions were included in our analysis, which constituted a response rate of about 54% in Russia and 67% in Belarus.

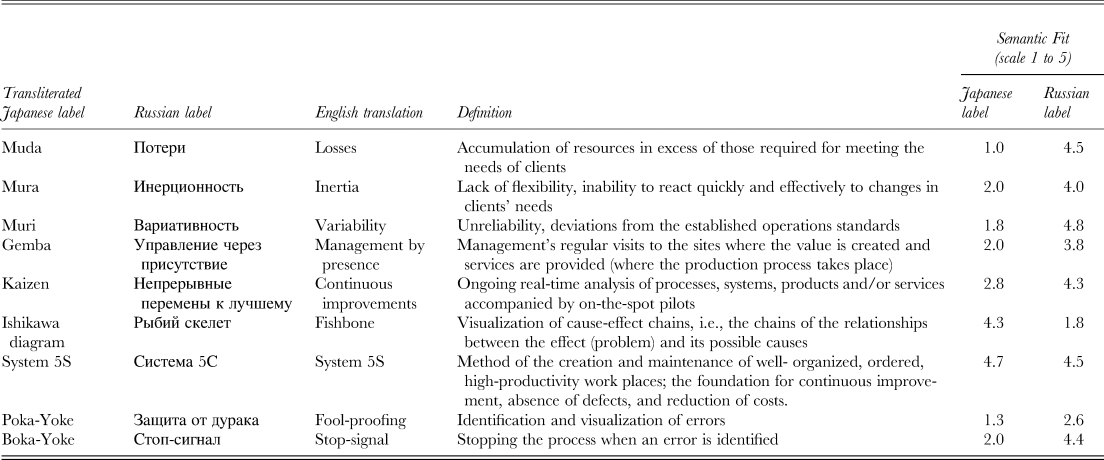

We investigated nine LPS practices that the bank's management considered critical for their activity, and on which training had been focused. Three practices related to problem identification, such as losses caused by accumulation of excess resources (Muda), inertia (Mura), and quality variability (Muri). The other six practices were solution oriented (Gemba, Kaizen, Ishikawa diagram, system 5S, Poka-Yoke, Boka-Yoke). The bank's management had prepared and distributed to all employees a ‘Dictionary of the Bank's Production System’. For each LPS practice, the dictionary listed its transliterated Japanese label, using Cyrillic letters, the translated label in Russian, and the definition of the component, also in Russian. This information is presented in Table 2. The first column of the table contains the Japanese label for LPS components, transliterated with Cyrillic letters, the second column contains the Russian label, the third is the translation in English of the Russian label, and the fourth column provides the common definition in English.

Table 2. Labels, definitions, and semantic fit

In order to understand whether the perceived relevance of LPS practices is affected by the practices’ labels, we implemented a field experiment in which the bank's employees were randomly assigned to one of two conditions. In the first condition, employees were asked about the relevance of each practice to their daily job, with practices called by their Japanese label, transliterated in Cyrillic, and followed by their definitions from the bank's dictionary. In the second condition, employees received the same questions, but this time practices were called by their translated labels in Russian, followed again by their definitions from the bank's dictionary. Thus, although all respondents assessed the same LPS practices, which were described identically by common definitions, the label under which the practices appeared was Japanese for the first group and Russian for the second. The randomization was done across both branches, so that employees at each branch had the same chance to be selected in one or the other group. We asked each employee to assess how relevant each practice was for their work on a 7-point Likert scale, with 1 ‘absolutely irrelevant’ and 7 ‘absolutely relevant’. With the context being identical for all respondents, if differences in relevance across the two groups appear, they would be caused by the only varying element, the label under which the practice was presented.

Semantic Fit

To evaluate the semantic fit of the LPS labels, we followed a procedure designed to capture the tacit linguistic intuition of native speakers previously used in studies regarding brand names in marketing. Specifically, Schmitt and Zhang (Reference Schmitt and Zhang2012) explored how native Chinese language experts, not marketing or branding specialists, assessed products and services with dual names, a common feature in Chinese brand naming. Four linguists assessed on a 5-point scale the semantic fit of the brand names, that is, whether the names sounded appropriate for a product or service in the category to which the brand belonged (e.g., medicine, soft-drink, banking, hotel, accounting).

To implement the procedure, we surveyed five Russian language and literature experts from two universities in the US and UK, four of which were native Russian speakers. We showed all the labels, the Japanese labels transliterated with Cyrillic letters, and the Russian translated labels, to each expert in a random order, and posed the following question: ‘Based on what you know about the phonetics, syntax, and other rules and conventions of the Russian language, does this sound to you like a term appropriate for naming a management practice’? The experts had to evaluate the fit on a 5-point scale, from 1 ‘absolutely inappropriate’ to 5 ‘absolutely appropriate’. To obtain the semantic fit for each label, we averaged the respondents’ answers.

Obtaining an external assessment of the semantic fit, as opposed to asking the employees about their perception of fit, is a requirement for the internal validity of well-designed experiments to protect against single-source bias (Chang, Witteloostuijn, & Eden, Reference Chang, Van Witteloostuijn and Eden2010; Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). In our case, this bias might lead to reverse causality whereby an LPS practice's relevance, as perceived by employees, affects the practice label's semantic fit assessed by the same employees. To the extent that our external respondents have the linguistic intuitions of natives, that is, equivalent to the native Russian-speaking employees in our survey, their assessment should appropriately capture the sense of semantic fit among Russian native speakers. Overall, the careful setting of the experiment allows us to build a strong causal model for assessing the impact of Russian and Japanese labels on the perceived relevance of LPS practices.

Analytical Strategy

To test our model, we ran a series of linear regressions, with the dependent variable Perceived Relevance of an LPS practice by the employee measured on a 1-7 scale, as described above. The effect of the Japanese label (compared to the Russian label) is captured by a dummy variable Japanese Label that takes value 1 if the label is transliterated Japanese and 0 if it is a Russian translated label. To test Hypothesis 1, that Japanese labels have a negative impact on the perceived relevance of practices by Russian employees, we regress Perceived Relevance on the variables Japanese Label and Minsk Branch, the latter being a control for possible differences between the branches. Minsk Branch takes value 1 for the Minsk branch and 0 otherwise. As the sample includes all the respondents who answered all the questions, we have no missing values and a total of 2,745 individual-evaluations across all nine practices.

To test for the mediating effect of a label's Semantic Fit (Hypothesis 2), we followed the mediation model described by Baron and Kenny (Reference Baron and Kenny1986). Specifically, we introduced the variables Japanese Label and Semantic Fit stepwise and ran an additional regression of Semantic Fit on Japanese Label. Practice fixed effects control for the unobserved variance among the nine LPS practices.

ANALYSIS AND FINDINGS

To get a first glimpse into the relationship between labels and perceived relevance, we start by presenting descriptive statistics and correlations among our variables. Table 3 shows that the mean of the perceived relevance varies significantly between 3.88 for Muri and 5.45 for Poka-Yoke. The correlations of specific interest are those between the perceived relevance of all practices and Japanese Label. The correlations are mostly negative, showing that the respondents who assessed the relevance of practices under the Japanese label perceived most of the practices as less relevant than the respondents who assessed the relevance of the same practices presented under the Russian label. Since we varied the labels’ language randomly, these correlations represent a first test of the causal relationship between label and perceived relevance.

Table 3. Perceived relevance of practices: Descriptive statistics and correlations for individual level variables (sample = 305 respondents)

Notes: Significance levels: *p<0.1, ** p<0.05 (correlation coefficients with Minsk Branch and Japanese Label are Bonferroni-adjusted)

Before presenting the full regression model, we also investigated descriptively the Semantic Fit. The last two columns in Table 2 show the mean fit assessment of the five linguists. The semantic fit varies across practices and across labels, with Muda unanimously considered not an appropriate sounding term for a management practice. Other labels, such as Poka-Yoke and Muri also received low semantic fit scores, as did the Russian Fishbone and Fool-proofing. The results are consistent with research on international brands, which showed that both foreignization and domestication of texts could result in low semantic fit, but also expose the fact that in our sample, overall, Japanese labels are perceived as having a lower semantic fit than the Russian labels.

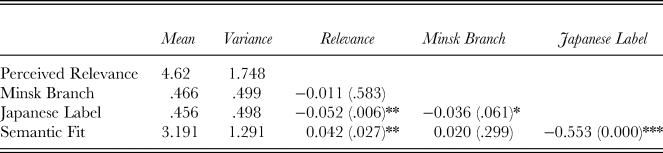

To test our entire model, we next run a set of regression analysis. Table 4 presents the descriptive statistics and correlations between all the variables in the regression models. As before, the correlation coefficient between the Japanese Label and Perceived Relevance is negative (−0.052, p = 0.006). Furthermore, the correlation coefficient between Semantic Fit and Perceived Relevance is positive (0.042, p = 0.027), while the coefficient between Semantic Fit and Japanese Label is negative (0.553, p = 0.000).

Table 4. Perceived relevance of practices: Descriptive statistics and correlations for individual*practice level variables (sample = 2745 individual*practice)

Notes: P-values are in parenthesis. Significance levels:

* p<0.1, ** p<0.05, *** p<0.001

Column 1 in Table 5 shows the results of our regression analysis testing of Hypothesis 1, that transliterated Japanese labels have a negative impact on the perceived relevance of LPS practices by Russian employees. Aside from the variables of interest, the regression includes controls for the branch, individual respondents and fixed-effects for the nine practices. The coefficient for Japanese Label is negative, showing that when practices are presented under a Japanese label, their perceived relevance for employees decreases by 0.186 (p = 0.065). This result is consistent with our descriptive findings and confirms Hypothesis 1 that a causal link exists between the language of the label and the perceived relevance of the practice named with that label.

Table 5. Linear regressions for testing the impact of label on perceived relevance1

Notes:

1 P-values are given in parentheses. Significance levels: * p<0.1, ** p<0.05, *** p<0.001

2 The coefficient estimate for the effect of Japanese Label does not change if practice fixed effects are included but the model overfits the data since the 18 degrees of freedom are too limited to start with.

To test Hypothesis 2, that the link Japanese Label – Perceived Relevance is not only influenced by the sheer foreign sound of a Japanese label but also could be due to the semantic fit of a label, we run the full mediation models (Baron & Kenny, Reference Baron and Kenny1986) and show the results in Table 5, columns 2–4. Model 2 shows that the semantic fit is 1.433 lower (on a scale of 1–5) for Japanese labels compared to Russian labels. This large effect unequivocally points to a lack of semantic fit of the transliterated Japanese labels. Model 3 links semantic fit with the perceived relevance of the practice. It shows that the higher the semantic fit of a practice's label, the higher the perceived relevance of that practice. In our case specifically, it shows that a 1-point increase of semantic fit has the effect of a 0.114 increase in perceived relevance (p = 001). This result represents causal quantitative evidence consistent with previous qualitative evidence in organizational translation research that semantic fit is a crucial aspect in trans-national moves of organizational practices, although it seldom receives attention (Brannen, Reference Brannen2004).

Model 4 confirms that the relationship between label and perceived relevance is mediated by the semantic fit of the label. Analytically, this is shown by the fact that when both variables Japanese Label and Semantic Fit are entered into the model together, the effect of Japanese label is reduced (from −0.186 in Model 1 when entered alone, to −0.027) and drops its statistical significance to p = 0.820, while Semantic Fit retains its sign, magnitude and statistical significance at p = 0.005. We also note that in none of the models did the branch to which the employees belong have a statistically significant impact (p>0.672).

The conclusions drawn from our analyses are robust to alternative explanations, as they are based on a carefully designed experiment aimed to assuage causal concerns typically associated with qualitative studies or quantitative non-experimental surveys. Our conclusions are theoretically meaningful, as they contribute to establishing whether a causal link exists between the language of a label and the perceived relevance of the practice presented with that label and to clarifying the mechanisms behind that link. Below we also investigate the practical meaning of our results by looking at effect sizes. As alternatives to reporting the statistical significance, which shows how likely the reported effect is, effect sizes communicate the practical significance of reported effects. Effect sizes represent the magnitude of the effects in a standardized metric that can be understood regardless of the scale used for measuring the dependent variable.

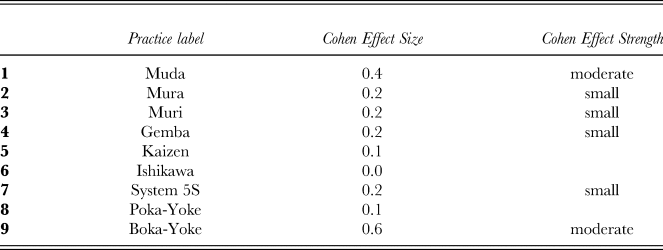

To qualify the magnitude of the effect we use Cohen's d method, which describes the standardized mean difference of an effect and is the standard method for calculating and reporting effect sizes in between–subject research designs. Specifically, Cohen suggests that when the ratio between mean differences of a variable measured in two experimental groups divided by the standard deviation of that variable is 0.2 we look at the effects as small, when the ratio reaches 0.4 we could consider the effects of medium size and when over 0.8 we could speak of large effects (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988, Reference Cohen1992). In Table 6 we present the effect sizes and their respective strength for each practice calculated using Cohen's method. The effect size varies across the nine practices, with Kaizen, Ishikawa, and Poka-Yoke showing ratios close to zero, most of the others showing small effects, and Muda and Boka-Yoke showing moderate size effects.

Table 6. Cohen effects size

We also note that effects presented here are the result of a rather conservative test of the relationship between a label and perceived relevance. First, the regression coefficients are aggregate effects across all practices; yet, when investigated with Cohen's method, there is clear variation in effect strength. Second, we sought respondents’ evaluations of relevance while exposing them to both the label as well as a precise definition of the practice under that label. In real life, an actor might not make it to the definition if the label triggers a sufficiently strong reaction. In such a situation, when employees just hear or read the label of a practice and stop short of the definition, we expect the effect of the label on relevance will be larger.

To summarize, our analysis shows that while the presence of a foreign label appears to generate a more negative reception of new practices (as evidenced by the negative coefficient for Label in Model 1, but qualified by the different strengths of the effect for each practice), that negative reception diminishes when the label's semantic fit is accounted for. In other words, the sheer foreignness of a label seems less problematic for the local audiences when the foreign label fits with the linguistic codes of the destination language. However, when the foreign label disrupts these codes, the negative effect of this disruption appears more important than its foreign sound.

DISCUSSION

In this article we have explored whether, and if so, how, the labels under which organizational practices are transferred to new linguistic contexts affect their reception by local audiences, specifically their perceived relevance by local employees. While previous research in organizational translation has started to shed light on the complex decisions regarding the naming of foreign practices with translated or transliterated terms, the actual impact of these translation decisions on the perceived relevance of practices by local audiences has received little attention (Piekkari et al., Reference Piekkari, Tietze and Koskinen2019; Tietze et al., Reference Tietze, Tansley and Helienek2017). We aimed to contribute to the organizational translation literature by investigating how the labeling of foreign practices, by use of transliterated foreign words versus translated words, affects their perceived relevance by the local employees called to implement them.

Drawing from translation studies and research on semantic fit, and using an experimental design in a Russian organization, we showed that the labeling of new practices affected their reception by local Russian-speaking employees. Specifically, when LPS practices were presented under transliterated Japanese labels they were viewed as less relevant than when they were presented under Russian labels. Especially in the Russian context, such a result was predicated on the lower trust in foreign ideas and the widespread belief in the worth of Russian values and the Russian way of doing things (Michailova & Husted, Reference Michailova and Husted2003; Puffer & McCarthy, Reference Puffer and McCarthy2011). However, our mediation analysis showed that this was not the only mechanism through which labels affected the perceived relevance of LPS practices. Specifically, the analysis showed that a much stronger mechanism was the semantic fit between the label and the linguistic code of the Russian language, and that, when the labels attached to LPS practices disrupted those codes, the perceived relevance of the practices by Russian employees decreased. Taken together, these results make a number of contributions.

We contribute to the literature on organizational translation by shedding light on some of the challenges encountered when practices cross linguistic boundaries, thus answering calls to expand the scope of translation research and more directly focusing on inter-lingual translation (Brannen et al., Reference Brannen, Piekkari and Tietze2014; Piekkari et al., Reference Piekkari, Tietze and Koskinen2019; Tenzer et al., Reference Tenzer, Terjesen and Harzing2017). Linguistic differences have been seen as barriers to communication between headquarters and subsidiaries (Reiche et al., Reference Reiche, Harzing and Pudelko2015; Schomaker & Zaheer, Reference Schomaker and Zaheer2014) and as ‘discursive voids’ (Outila et al., Reference Outila, Piekkari and Mihailova2019; Tietze et al., Reference Tietze, Tansley and Helienek2017) to be bridged by a variety of translators. Up to now, substantive research effort has been put into better understanding how various actors co-create definitions of imported practices that are meaningful for the local audiences. Our study continues this research effort by asking whether it matters if definitions are labeled with transliterated or translated words.

The results of our experiment show that the language in which the nine LPS practices were labeled mattered for the Russian employees who were called to use these practices, and that they found the practices more relevant when they were presented under a translated Russian label compared to a transliterated original Japanese label. The analysis also showed that the influence of a foreign label on perceived relevance happens mostly indirectly, by affecting the sense of fit with the local linguistic codes. Thus, our contribution to the organizational translation research lies in the findings regarding these mechanisms, especially the role of semantic fit.

The question as to whether the language of the labels matters is not only theoretically intriguing, but also practically relevant, as organizations increasingly aim to transfer and adopt practices developed in countries with different socio-cultural and linguistic contexts. With many practices (especially Western ones) diffused now globally, late adopters have limited opportunities to change the terminology that accompanies these practices. For instance in Russia, the setting of our study, transliteration (especially from English) appears to be, for many organizations, the preferred way of labeling foreign practices (Kuznetsova & Kuznetsov, Reference Kuznetsov and Kuznetsova2014), despite increasing calls for the creation of a comprehensive Russian business dictionary that would allow Russian organizations to draw from a common vocabulary when introducing a foreign practice (Holden et al., Reference Holden, Kuznetsova, Fink and Tietze2008; Pshenichnikova, Reference Pshenichnikova2003).

Our analyses suggest that creating a common Russian dictionary might not suffice, and that a major recontextualization effort should also be considered as an important part of this endeavor. Specifically, the semantic fit of the labels included in such a dictionary should be checked and, where labels with a low semantic fit are in use, organizations might consider proactive counter strategies such as offering early hands-on experience with new practices and demonstrating their benefits (‘learning by doing’) to compensate for possible low semantic fit.

The results of our study are also useful for managers who lead practice transfer exercises in their organizations. As it was the case in the organization in which we conducted our study, the managers had no insight into the reasons why translated or transliterated terms should be favored in order to affect the perception of LPS practices. We believe that understanding the different mechanisms through which labels affect perceived relevance is important, because each mechanism suggests a different strategy. If only the foreign sound matters, then organizations should always strive to fully translate the terminology of foreign practices. If the semantic fit affects perceptions of relevance, then organizations should take a more nuanced approach: retain some foreign labels, especially those that are widely used around the world, and translate others, especially those that disrupt local semantic codes.

By using a field experiment, our study answers calls from researchers in the fields of organizational translation and international business to expand the repertoire of data sources and analytical techniques in order to better test causal effects of language differences (Tenzer et al., Reference Tenzer, Terjesen and Harzing2017). Our study suggests that experiments, although difficult to set up, are an effective tool to test claims established via qualitative or cross-sectional surveys (Fan & Harzing, Reference Fan, Harzing, Horn, Lecomte and Tietze2020). To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to use an experimental setting to causally test the effect of labels on the perceived relevance of practices and some of the mechanisms responsible for this effect.

While identifying the causal effects is an empirical contribution of the article, the small size of some of these effects warrants an elaboration of the discussion in the Analysis and Findings section above. There we pointed to a variation in effect strength, with two transliterated labels out of nine studied showing a moderate effect on perceived relevance, and argued that our exposing the respondents to both the label and a precise definition of the practice under that label might have dampened the effect of the label per se. Another plausible explanation for the small effect sizes is Russians’ familiarity with scientific management, the forerunner of LPS (Beissinger, Reference Beissinger1988). Familiarity with management practices themselves can decrease the importance of their labeling, in general, and of any differences between transliterated and translated labels, in particular. By asking respondents whether a specific new practice is familiar to them or reminds them of another practice, future studies could test if the label effect is larger when the familiarity effect is controlled for.

At the same time, small effects should not be seen as less important. Small differences at the outset might have large consequences later: The initial slightly lower perceived relevance of a practice due to its Japanese label could create a vicious cycle if it undermines the implementation process and yields an ineffective practice. Indeed, Kuznetsov and Kuznetsova (Reference Kuznetsov and Kuznetsova2016: 79) warn that initial glitches in the transfer of foreign knowledge can be highly consequential as ‘a cause of severe and enduring problems with the adoption and absorption of new knowledge’, while Brannen (Reference Brannen2004: 603) gives multiple examples where poor initial semantic fit induces negative effects on various innovative production methods including continuous improvement (kaizen). In our empirical case, one can imagine employees inventing counter-cultural artifacts – anecdotes, jokes, etc. – that ridicule the imported practices, discourage engagement with them, and condemn them to failure.

A related limitation of our analysis is the R-square of 0.075 and thus the greater than 90% unexplained variance of the outcome, which prompts the question of complementary theories that might explain the perceived relevance of lean production practices. The growing literature on employee perspectives on HR Management Systems (HRMS) identifies a number of contenders: the congruence between employees’ and managers’ goals as well as managers’ positional power, legitimacy, and credibility (Bowen & Ostroff, Reference Bowen and Ostroff2004); the firm's HR strategy, quality versus cost reduction, and employee well-being oriented philosophy (Nishii et al., Reference Nishii, Lepak and Schneider2008); an employee's gender, status, employment security, and advancement opportunities (Liao, Toya, Lepak, & Hong, Reference Liao, Toya, Lepak and Hong2009). While this literature establishes mainly associations between the listed factors and employee perception of HRMS, our article paves the road for testing the same factors’ causal effects.

While the difference between transliterated labels and translated labels is generally small in terms of their effects on the perceived relevance of the corresponding LPS practices, they differ drastically in terms of semantic fit, and this difference explains about 30% of the overall variance in semantic fit in our model. This partial confirmation of semantic fit being a mediator between labeling and perceived relevance of management practices is an important contribution in its own right, since it provides the first quantitative evidence to evaluate two major claims: first, that foreign management terms often misfit the Russian linguistic and socio-cultural context; and second, that low semantic fit is consequential for organizational outcomes. Our findings offer much stronger support for the former than for the latter: The semantic fit of foreign terms is an issue per se but might not be as practically consequential as the extant literature claims. Future research could apply our experimental method to other organizational activities of international business, such as negotiations, teamwork, or mergers and acquisitions, to induce a lack of semantic fit and assess its effect on the outcome of interest.

The contribution of this paper is also limited by a rather narrow coverage of LPS practices. The most comprehensive recent review of lean production in manufacturing identifies 48 practices (Shah & Ward, Reference Shah and Ward2007) while we included only nine in our analysis. Management's particular focus on these nine LPS components at our Russian bank, together with our own interest in the role of language, and not the practices per se, partially justify our research design. A more comprehensive analysis of lean production systems using the approach developed in this article is certainly in order.

A final limitation concerns the generalizability of the effects presented here. Our study and its hypotheses have been contextualized to a Russian setting, yet one might wonder whether these effects are limited to Japanese labels in Russia or whether they could be extended to other situations. Are they about a language's strangeness or its status? We believe that the evidence from the literature we reviewed suggests that the way in which foreign practices are labeled and employees’ perceived relevance, and possibly use, of these practices, are linked, and that further studies that could clearly separate the mechanisms that link them are certainly needed.

CONCLUSION

In summary, by unpacking the relationship between the labels under which foreign practices are introduced to a local audience and the perceived relevance of these practices by that audience, this study contributes to a better understanding of how organizations could intervene to improve employees’ grasp of new practices and to increase the chance that employees will more easily adopt them in their daily work. Moreover, by testing this relationship in Russia, and with a language that is very different from English as today's lingua franca, we provide a glimpse of the potential that transition economies offer to advancing organizational translation research.