INTRODUCTION

The Multifaceted Nature of Informal Networks

Research on informal networking, or network-based problem solving in which interpersonal ties are effectively converted into firm-level performance, has a rich history in the literature on management and organization (Larson & Starr, Reference Larson and Starr1993; Nonaka & Von Krogh, Reference Nonaka and Von Krogh2009). In contrast, the informal dimensions of management and organization in an international context have received much less attention. Many scholars have pointed out that networking theories and comparative analyses of social capital are developed largely by Western scholars and based on assumptions of circumstances and social structures that are typical in Western societies (Horak, Taube, Yang, & Restel, Reference Horak, Taube, Yang and Restel2019). Thus, these theories need a robustness test for informal ties and networks formed in other parts of the world and, possibly, adjustment to account for their nature, characteristics, and tacit knowledge (Fey & Denison, Reference Fey and Denison2003; Ledeneva, Reference Ledeneva2008, Reference Ledeneva, Ledeneva, Bailey, Barron, Curro and Teague2018; Li, Reference Li2007b; Qi, Reference Qi2013; Sato, Reference Sato, Burawoy, Chang and Hsieh2010). The growing body of literature about informal ties and networks in various emerging and transitional countries – such as guanxi (China), blat (Russia), clannism (Kazakhstan), and wasta (Arabic-speaking countries) – has resulted in analyses on the role of informal networks in advanced and industrialized economies. Horak and Taube (Reference Horak and Taube2016) discuss yongo in South Korea, Sato (Reference Sato, Ledeneva, Bailey, Barron, Curro and Teague2018) writes about aidagara in Japan, and Kubbe (Reference Kubbe and Ledeneva2018) analyzes vitamin B in Germany, and there are many other examples (Ledeneva, Bailey, Barron, Curro, & Teague, Reference Ledeneva, Bailey, Barron, Curro and Teague2018). The findings on emerging markets emphasize the role of informal networks in transitions and structural changes in formal institutions, and insights in studies on developed economies indicate that informal networks persist even where formal institutions are effective. The multifaceted nature of informal networks and their transformation in the process of development prompts a detailed examination of the range of functions associated with informal networks in theory and practice. Until now, the literature has been dominated by research on China and studies on guanxi. This special issue, driven by the need for incorporating research originating in other contexts, takes a cross-country comparative perspective and enhances our understanding of the effect of differences and similarities among countries on the way in which informal networks operate and are perceived and conceptualized.

Family ties are viewed as essential for socialization, well-being, and family business success in market democracies but also associated with nepotism, dynasties, and family-run states. Likewise, informal networks in emerging markets are sometimes viewed askance because of their moral ambivalence and an assumed association with collusion, cliques, clans, cronyism, and other negative phenomena. Moreover, it is often believed that informal networks in emerging markets should not receive great attention, as they will become superfluous after formal institutions develop, and people learn to trust these institutions. Hence, it is essential to concentrate on reforming formal institutions and capacity building for transparency, accountability, disclosure, and other principles of good governance. However, recent studies show that informal networks do not seem to disappear in emerging markets as they mature (e.g., on China, see Bian, Reference Bian2017, Reference Bian2018, Reference Bian2019), nor are they superfluous in more advanced economies (e.g., on South Korea, see Horak & Klein, Reference Horak and Klein2016). They seem to persist because of, or in spite of, their capacity to adjust to the dynamics of development in business, politics, and society.

The full spectrum of informal networks’ capacity for change and continuity, as well as their bright and dark sides has not yet been discussed or explored in specific contexts. We hope that this special issue will spark more research and generate more knowledge on how both aspects can be successfully managed, so that the dark side of informal networking are better controlled, regulated, or reduced without losing social cohesion, flexibility, and other benefits of the bright sides. Indeed, the documented benefits of informal networks include efficiency gains in the coordination of economic activities and entrepreneurship as well as social contributions, which are important for individual well-being, such as community spirit, solidarity, and sociability. Thus, we contribute to and broaden the evolving discussion in the business-to-business (B2B) literature since the 1990s on the dark side of business relationships (Abosag, Yen, & Barnes, Reference Abosag, Yen and Barnes2016; Anderson & Jap, Reference Anderson and Jap2005; Grayson & Ambler, Reference Grayson and Ambler1999). This B2B research stream focuses primarily on business relationships between buyers and suppliers by analyzing the pernicious part of business relationships when they became too close, resulting in opportunism, deception, lock-in with current partners, and opportunity costs leading to underperformance (Abosag et al., Reference Abosag, Yen and Barnes2016; Jiang, Liu, Fey, & Wang, Reference Jiang, Liu, Fey and Wang2019).

In B2B relationships, the type of organization with which one is developing informal networks is important (Jiang et al. Reference Jiang, Liu, Fey and Wang2019). In business-to-government relationships, the stronger the relationship the better, because if your firm is based in Beijing, a relationship with the Beijing government cannot usefully be substituted for one with the Shenzhen government (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Liu, Fey and Wang2019). In contrast, B2B relationships need to be moderately strong, rather than as strong as possible (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Liu, Fey and Wang2019), because very weak relationships generate no leverage, but overly strong relationships create excessive ties, which could prevent the pursuit of other attractive options.

This study of informal networks is broader in scope than the B2B literature, which focuses on business contexts and emphasizes the dark side of business relationships (Abosag et al., Reference Abosag, Yen and Barnes2016; Anderson & Jap, Reference Anderson and Jap2005; Grayson & Ambler, Reference Grayson and Ambler1999). Informal networks are embedded in culture and society, in which both formal and informal constraints shape their modes of operation. Hence, our conceptualization of informal networks is intended to apply to and integrate knowledge from different countries.

Expertise in informal networks is sometimes associated with area studies and their nuanced approach to culture. The most developed are China-centered studies on guanxi (Bian, Reference Bian1997, Reference Bian2017, Reference Bian2018, Reference Bian2019; Burt & Burzynska, Reference Burt and Burzynska2017; Chen & Chen, Reference Chen and Chen2009; Chen, Chen, & Huang, Reference Chen, Chen and Huang2013; Li, Reference Li and Yeoung2007a, Reference Li2007b; Luo, Reference Luo2000; Opper, Nee, & Holm, Reference Opper, Nee and Holm2017). Some research has been conducted on blat and svyazi in Russia, Ukraine, the Caucasus, and other areas in the former Soviet Union (Ledeneva, Reference Ledeneva1998, Reference Ledeneva, Bittner, Hackenbroich and Vockler2006; Smith, Torres, Leong, Budhwar, Achoui, & Lebedeva, Reference Smith, Torres, Leong, Budhwar, Achoui and Lebedeva2012; Yakubovich, Reference Yakubovich2005). Analyses have also been done on yongo networks in South Korea (Horak & Klein, Reference Horak and Klein2016; Horak & Taube, Reference Horak and Taube2016), clannism in Kazakhstan (Minbaeva & Muratbekova-Touron, Reference Minbaeva and Muratbekova-Touron2013), jeitinho in Brazil (Park, Nunes, Muratbekova-Touron, & Moatti, Reference Park, Nunes, Muratbekova-Touron and Moatti2018), and wasta in Arabic-speaking countries (Abosag & Lee, Reference Abosag and Lee2013; Afiouni & Nakhle, Reference Afiouni, Nakhle, Budhwar and Mellahi2016; Al-Husan, Al-Hussan, & Fletcher-Chen, Reference Al-Hussan, Al-Husan and Fletcher-Chen2014; Berger, Herstein, McCarthy, & Puffer, Reference Berger, Herstein, McCarthy and Puffer2019; Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006aReference Hutchings and Weirb). Fragmentation in area studies is replicated in studies on informal networks, so the research on informal networks in an international context is in its infancy and lacks comparative analyses, as the international business literature predominantly focuses on guanxi.

The centrality of informal networking in the modus operandi of the largest economies in the world – such as China, India, Russia and the former republics of the Soviet Union, Arab countries, and countries in South America – makes it essential for us to understand both its dark and bright sides if we are to grasp its global implications. By shedding light on the dynamic and often ambivalent operating modes of informal networks, this special issue of MOR is a step in that direction.

DEFINING INFORMAL NETWORKS IN EMPIRICAL RESEARCH

Informal networks have been studied in several disciplines, among others, in economics, sociology or social anthropology. In economics, for instance, research on economic ‘clubs' finds that transaction costs for economic coordination of activities can be kept low through informal coordination and conciliation, peer pressure, and collective punishment (Buchanan, Reference Buchanan1965; Sandler & Tschirhart, Reference Sandler and Tschirhart1997). In sociology, the roots of informal network research can be traced back to Park (Reference Park1924), Simmel (Reference Simmel and Wolff1950), Homans (Reference Homans1950), Cooley (Reference Cooley1956), and Blau (Reference Blau1964), who analyzed patterns of interaction and communication in order to understand social life. In social anthropology, the development of exchange theory focused on the content of relationships that actors form and the conditions under which they evolve (Lévi-Strauss, Reference Levi-Strauss1969; Malinowski, Reference Malinowski1922). Role theory used the metaphor of ‘fishnets’ in studying organizations to describe the loosely coordinated work of units in an organization, thus implying the network concept (Katz & Kahn, Reference Katz and Kahn1966).

The most common understanding of informal networks implies that social networks have some utility in handling formal constraints. In the language of participants, this use is often referred to as mutual help or personal trust. In the language of observers, the situation is much more complex. According to the ‘topographical map’ of existing perspectives on social networks, students of social networks implicitly or explicitly make two choices. First, they treat ‘nodes and ties’ as either personal (represented by people) or impersonal (represented by organizations). Second, they consider networks internally (exploring their constitution and properties) or externally (exploring their implications in a broader socioeconomic context) (Ledeneva Reference Ledeneva, Bittner, Hackenbroich and Vockler2006).

For our purposes, the internal constitution and properties of informal networks can be distinguished by transactional content, the nature of the links, and structural characteristics (Tichy, Tushman, & Fombrun Reference Tichy, Tushman and Fombrun1979). Thus far, the dominant focus of network analysis has been structural characteristics, including network characteristics, such as size, density, centrality, bridging, and gatekeeping. Size and density have been underresearched, and even less so in emerging markets, but the existing studies provide a framework for analyzing informal networks in business (Shekshnia, Ledeneva, & Denisova-Schmidt Reference Shekshnia, Ledeneva and Denisova-Schmidt2017). Transactions can involve everything from an information exchange, advice, and benchmark intelligence to help and support. Efficient and effective information exchange is an explanation for bonding as well as a strategy for manipulating behavior. The discussion on the nature of the links includes the frequency of contact or relational strength. Granovetter (Reference Granovetter1973, Reference Granovetter2017) sharpened understanding of social networks by introducing a notion of the strength of ties in characterizing networks. However, the presumed reciprocal interaction of the nodes is simplified. Given networks’ multiplicity, it is essential to understand whether and in what way actors are linked to other networks and how networks overlap.

In terms of external implications, the conceptualization of networks, related to their multiplicity, overlap, and potential for channeling, is essential for overcoming opposite phenomena, such as the individual versus structure in sociology, subjectivism versus objectivism in social theory, and bounded versus absolute rationality in economics. The network effect can be understood as compensating for limited human capacity and human failure to match the assumption of perfect rationality of homo economicus, thus mitigating the issue of “bounded rationality” (Simon Reference Simon1957: 198; see also Klaes & Sent Reference Klaes and Esther-Mirjam2005). Belonging to networks benefits insiders, often without intentionality or even awareness. The value, capacity, and impact of informal networks is related to network capital, assessed through the prism of social network analysis or a social capital framework. From the social capital perspective, these ties are linked to the advantages and opportunities that people obtain through membership in certain communities or networks. According to Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu and Richardson1986: 248–249) social capital is ‘the aggregate of the actual or potential resources which are linked to possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition’. Whereas Bourdieu tended to associate social capital with the embedded advantages of the privileged and thus viewed it as negative, Coleman (Reference Coleman1988) introduced the notion of positive and negative social capital. Burt (Reference Burt1992; Burt & Burzynska, Reference Burt and Burzynska2017) further conceived the potential for brokerage between social networks.

The concept of social capital has been used as a theoretical framework for discussing informal ties (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu and Richardson1986; Burt, Reference Burt1992; Lin, Reference Lin2001) by addressing the ‘intangible’ mechanisms behind economic interactions that could be used as a basis for comparison (Putnam, Reference Putnam1995). For empirical purposes, researchers tend to explore either the subversive side of networks (as in the B2B study discussed above) or the supportive side of networks, related to civic capital, economic growth, health, happiness, and well-being (Guiso, Sapienza, & Zingales, Reference Guiso, Sapienza and Zingales2010). In this special issue, we focus on the functional ambivalence in informal networks and discuss both the dark and bright sides, as well as establish the potential for achieving a balance by adjusting the formal and informal constraints within which networks operate.

Viewed from a broader perspective on informality, informal networks are shaped, driven, or regulated by institutional frameworks while also shaping, driving, and regulating them. Typically, informal networks are said to be more important in the coordination of activities in transitional economies, where formal institutions (e.g., contracts, formal rules, law, courts) are ineffective or nonexistent (North, Reference North1990; Peng, Pinkham, Sun, & Chen, Reference Peng, Pinkham, Sun and Chen2009). Yet, in both developing and developed economies, despite its simplistic nature the formal/informal dichotomy is useful for empirical research for several reasons. First, it allows us to envisage a spectrum of constraints – a full range of existing constraints on human behavior, from formal/legal regulations to social norms and informal pressure – that embraces their variety and multiplicity. Second, by pointing out the informal part of the formal, it prevents us from ignoring the hidden structures in uncodified or unarticulated forms, which would yield a distorted perspective of management, organizational behavior, business, and leadership. Third, the formal/informal dichotomy can be looked at dynamically, that is, it can imply either formalization of informal norms or informalization of formal rules. This perspective highlights the role of informal networks as tools and channels for backing up both formal institutions/organizations and informal institutions/values, norms, and ethics of behavior.

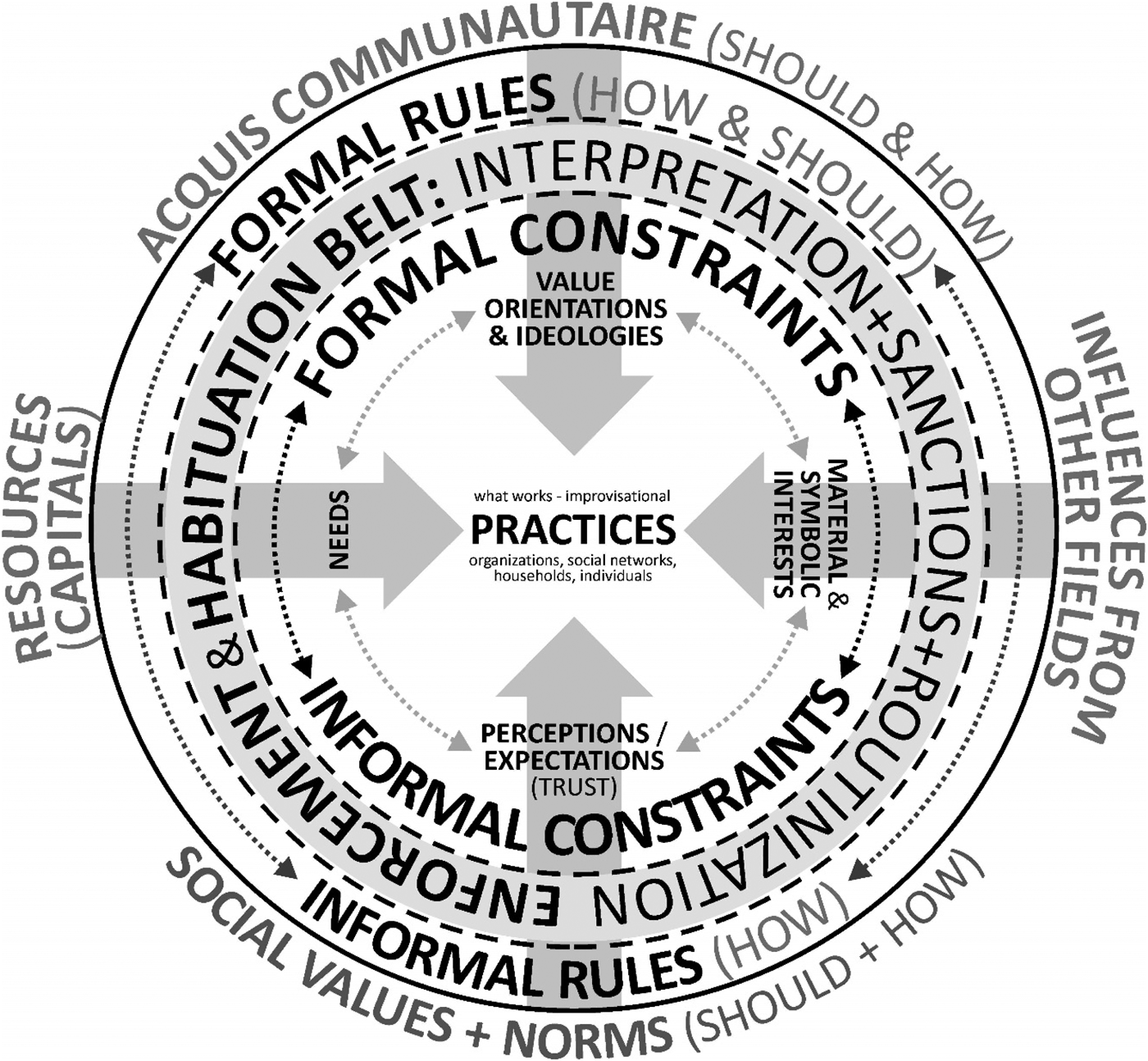

Our understanding of Douglass North's definition of ‘institutions’ is that they are ‘the humanly devised constraints that structure political, economic and social interaction. They consist of both informal constraints (sanctions, taboos, customs, traditions, and codes of conduct), and formal rules (constitutions, laws, property rights)’ (Reference North1991: 97; emphasis added). Interestingly, North puts ‘informal constraints’ before ‘formal rules’, which might reflect his views on their historical primacy. However, empirically the combination of formal rules and informal constraints that frame the ways in which informal networks operate creates constraints only when the legal rules and social norms are enforced. To become actual constraints, both rules and norms have to go through the ‘enforcement; belt, as illustrated in Figure 1, showing the gap between formal and informal institutions in the Europeanization of the western Balkans.

Figure 1. Closing the gaps between formal and informal institutions: A theoretical model

The model looks complex, yet its fundamental premises are consistent with Scott's (Reference Scott and Ritzer2004b) interpretation of institutional theory. Scott's (Reference Scott2004a) conception of institutions as durable ‘social structures’ consists of three pillars: (1) cultural-cognitive, (2) normative, and (3) regulative elements that give stability and meaning to social life. The first two pillars can be seen as informal constraints (cultural norms, customs, codes of conduct) and formal rules (normative prescription), while the third ensures that these elements both become actual constraints, i.e., regulated and enforced.

An important empirical question is whether informal networks can be considered social structures or institutions. Their potentiality and often dormant nature seem to support this notion. The fluidity and the context-bound nature of informal networks, relationship-based and rules-oriented, suggest otherwise. Informal networks appear to be universal in human society, but how work depends on the context, and their functionality varies significantly across countries and development stages. North describes economic development in two stages:

1. Local exchanges within a village community, in which dense social networks of informal constraints facilitate local exchange with a relatively low transaction cost (Clifford Geertz, 1979; cited in North, Reference North1991).

2. Market exchanges linking a village community to larger, urban, and interconnected ‘markets’. This stage of economic development is full of transactions among socially distant individuals, which increase transaction costs that call for formal rules to reduce risk of various kinds due to increasing transactions among strangers (North, Reference North1991).

North's views on the evolutionary nature of institutions seem to contradict the idea of informal networks as institutions:

Throughout history, institutions have been devised by human beings to create order and reduce uncertainty in exchange. Together with the standard constraints of economics they define the choice set and therefore, determine transaction and production costs and hence the profitability and feasibility of engaging in economic activity. They evolve incrementally, connecting the past with the present and the future; history in consequence is largely a story of institutional evolution in which the historical performance of economies can only be understood as a part of a sequential story. (Reference North1991: 97)

However, informal networks certainly enable constraints, as the channels and ‘conveyer belts’ for enforcing cultural norms and formal/organizational changes through peer pressure. In other words, when social networks channel informal pressure, driven by personal relationships, formal rules and procedures are circumvented, and they are referred to as ‘informal networks’. Such informal networks are particularly essential when formal rules and informal constraints clash and impose contradictory demands on an individual. For example, in some institutional frameworks, both formal and informal constraints are so strong that an official cannot remain a good bureaucrat and a good brother at the same time, so informal networks enable and channel ways of navigating the constraints to help the brother while still keeping the bureaucratic job.

In other types of sociological ambivalence, some professionals are similarly vulnerable to conflicting demands on the job. Merton (Reference Merton1976) offers an example of a doctor who has to give a patient personal attention yet remain an impartial and impersonal expert. The idea of dual utility (i.e., a knife that can both kill and cure) applies to networks. Although an informal network per se is neither good nor bad, its functionality is defined by the nature of the formal and informal constraints that shape them. The conventional wisdom is that informal networks are good when they do not siphon public resources/funds/abuse power or betray trust and bad when they do. Nonetheless, understanding societies in which the boundary between public and private is blurred is challenging in empirical research.

Many theoretical debates have taken place in management studies and political science on the types of interaction between formal (grounded in codified rules enforced by hierarchies) and informal (grounded in norms, customs, and traditions enforced by social networks) institutions (Helmke & Levitsky, Reference Helmke and Levitsky2004), but empirical studies on such interactions are not plentiful. One reason is the typology itself. Although political scientists shed light on the dynamics of interaction between formal and informal institutions, they seem to deny informal institutions equal status. The primacy and (in)effectiveness of formal institutions define the types of informal institutions: accommodating, substituting, complementary, or competing (Helmke & Levitsky, Reference Helmke and Levitsky2004). The typology and comparative agenda have been formulated but not empirically tested.

The other reason for this empirical elusiveness of informality is that the notions of the formal and the informal are analytical constructs, which are often difficult to detach and analyze separately or possess dual utility that is hard to categorize. In fact, what is formal and what is informal are often contextual and depend on the perspective: ‘Like a quantum particle, we find them in two modalities at once: informal practices are one thing for participants and another for observers’ (Ledeneva, Reference Ledeneva, Ledeneva, Bailey, Barron, Curro and Teague2018: 7). One key challenge in trying to understand informality is to resist making analogies to formal institutions. Informality is fluid, seemingly irrelevant, or taken for granted – in other words, it appears nonexistent unless one is looking for it or questions it explicitly (Ledeneva, Reference Ledeneva1998: 4). Conventionally, this is the case when we perceive an environment as ‘normal’ because we were raised and socialized in it. In other words you find what you are looking for.

In emerging market studies, it is reasonable to question whether the formal/informal distinction remains useful for understanding developmental issues:

One might expect to see a clear definition of the concepts, consistently applied across the whole range of theoretical, empirical, and policy analyses. We find no such thing. Instead, it turns out that formal and informal are better thought of as metaphors that conjure up a mental picture of whatever the user has in mind at that particular time. (Guha-Khasnobis, Kanbur, & Ostrom, Reference Guha-Khasnobis, Kanbur and Ostrom2006: 3)

We focus here on the empirical evidence on informal networks in order to highlight the full spectrum of existing constraints, both formal and informal, to make them visible and to assess their potential for transformative change. In some countries, business success is barely possible without informal networks. Because informal networks are not codified and are not easy to study, their modus operandi, with their dark and bright sides, should be firmly on the agenda of leaders of multinational corporations in order to assess risks and seize opportunities. However, the three implications of the formal/informal dichotomy point equally in the opposite direction: the potential for formalizing informal networks, the crucial role of formal constraints in shaping the modus operandi of informal networks, and the complexity of constraints that drive the functional ambivalence of informal networks. (For a summary of quantitative studies used in this introduction and their effect sizes, see Appendix I, and for a summary of qualitative studies, see Appendix II.)

THE DARK AND THE BRIGHT SIDES OF INFORMAL NETWORKS

The moral ambiguity involved in discussing both the dark and bright sides presents an obstacle that requires a delicate touch. Obviously, neither scholars nor practitioners are keen on appearing to overlook the negative aspects of networking deliberately. Informal networking is conventionally connected to the risk of corruption associated with gifts, favoritism, nepotism, insider trading, and fraud. In other words, merely exploring the bright side of informal networking might create the impression of support for dubious, quasi legal, questionable, or unprofessional behavior. The ethics of conducting ethnographic fieldwork in contexts with normative frameworks that may vary from the mainstream is not a new issue. Methodologically, social and legal anthropologists studying corruption recommend suspending normative judgments about behavior while collecting data but resuming it when they are analyzed. More generally, the negative bias has to be confronted, mindful that negative events are more powerful than positive ones. In social psychology, it is said that ‘bad feedback has more impact than good ones [sic], and bad information is processed more thoroughly than good. Bad impressions and bad stereotypes are quicker to form and more resistant to disconfirmation than good ones’ (Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Finkenauer, & Vohs, Reference Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Finkenauer and Vohs2001: 323). Baumeister et al. (Reference Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Finkenauer and Vohs2001) find few exceptions to the rule that ‘bad is stronger than good' and speculate that nature may have shaped the human psyche to be more sensitive to negative events as part of risk management and developing a survival instinct.

However, ignoring the dark side by focusing on the bright side may not be the best approach either. Psychological research suggests that a focus on reducing the effects of the dark side in relationships may be more influential in improving relationships overall than investing solely in the bright side (Baumeister et al., Reference Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Finkenauer and Vohs2001). Inspired by psychological research, we take a more holistic approach and consider both aspects of informal networks. We employ a strategy of transforming informal networks by trying to reduce their dark-side effects (e.g., by increasing transparency), as well as exploring the potential of the bright side, along with an assessment of their respective effectiveness and time horizon.

Studies on the dark side of informal networking point out its vulnerability to corrupt behavior, competitive advantage, channeling favors, and abuse of power, often exercised with a nod to cultural practices and traditions. For instance, guanxi and corruption are said to be supported by the Chinese culture of giving gifts (Luo, Reference Luo2008). Russian culture includes kinds of cooptation known as kormlenie (feeding), that is, allowing civil servants to feed off the office and the constituency, which persisted through tsarism and the Soviet period and are observed to this day. Favoritism in hiring and promotions, in which candidates are recruited or promoted not because of merit and competence but because of knowing the right people, can prevent an organization from advancing and limit its potential for creativity and innovativeness (Horak, Reference Horak2017; Banovic, in Ledeneva et al., Reference Ledeneva, Bailey, Barron, Curro and Teague2018). In South Korea, which is often described as a networked society, respective networks (i.e., in-groups) have ‘flexibility, tolerance, mutual understanding as well as trust. Outside the boundary, on the contrary, people are treated as “non-persons” and there can be discrimination and even hostility’ (Kim, Reference Kim2000: 179).

Countries have different levels of tolerance for the social cost of competitive advantage, correlated to their level of openness. Not only do business expatriates face difficulty in integrating into a society and a business environment with a low level of receptiveness caused by tight domestic networks but society as a whole, which sharply distinguishes in-groups and out-groups, can also suffer because of segregation (Kim, Reference Kim2000; Renshaw, Reference Renshaw2011).

For instance, the bright side of informal networks refers to an informational advantage that members possess (Gu, Hung, & Tse, Reference Gu, Hung and Tse2008). Separate informal networks that become connected, or bridged, benefit from the larger amount of information available because of being connected. People can be motivated to connect networks – i.e., to become ‘a node’ – by potential benefits, at least for a while, from the connection, as most information flows between networks via nodes (Burt, Reference Burt1992, Reference Burt1995, Reference Burt, Lin, Cook and Burt2001; Coleman, Reference Coleman1988). The bridging of networks is usually conducted via weak ties, whereas strong ties are related to bonding social capital and serve to exchange information within an extant network. Organizations are said to benefit most in terms of information acquisition when their managers can draw on a diversity of ties – i.e., on a mixture of strong and weak ties with peers as well as non-peers (Burt, Reference Burt1997, Reference Burt2000).

Further, from an economic perspective, informal networks contribute to a reduction in transaction costs and the risk of free riding by network members, because they have established mutual trust as well as peer pressure. This lowers the cost of monitoring and supervision. For example, if someone is hired for a job on the recommendation of a network member, an obligation is created between that person and the recommender as well as the network that enabled and backed this decision. In addition, if that person, after obtaining the job, becomes a free rider or exploits the position for personal gain, the recommender's reputation is put at risk (Burt, Reference Burt2000; Lew, Reference Lew2013). Further, informal ties and networks are often based on a certain level of trust, and they support cooperation and mutual help, provide sociability and emotional support, and hence reduce loneliness (Ledeneva, Reference Ledeneva, Ledeneva, Bailey, Barron, Curro and Teague2018). However, exchanges of any kind lead to an implicit contract that demands reciprocity; therefore, maintaining ties through reciprocal favors and satisfying demands can be time consuming, costly, and, at times, burdensome.

Nonetheless, informal networks can be seen as a reliable resource in uncertain environments with a weak legal system (Gu et al., Reference Gu, Hung and Tse2008). As mentioned in the context of guanxi and wasta, its mediation function plays an important role in conflicts, whether in business or in family affairs (Barnett, Yandle, & Naufal, Reference Barnett, Yandle and Naufal2013). However, as the perceptions of the bad dominate those of the good, ‘people generally speak of wasta in negative terms and think largely of its corrupt side, negating the traditionally positive role it has played in mediation’ (Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006a:147). When people speak about leveraging their networks, they often mention leveraging their friends, which they suggest is a good thing; in contrast, when people talk about others leveraging their networks, they often use words such as blat and wasta, which more often have a negative connotation. In other words, there is a double standard. The dark sides and the bright sides of informal networks are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. The dark sides and the bright of informal networks

CONTRIBUTIONS TO THIS SPECIAL ISSUE

The contributions to this special issue add to our knowledge on informal networks in several ways, taking their dark and bright sides into account. They cover a range of informal network ties and types as they offer new insights on informal aspects of management in China, with a focus on guanxi as well as the functioning of the less studied network types, such as elite networks in Malaysia, wasta in Arab countries, and bazaaries in Iran.

In alignment with MOR's mission, contributions on China and guanxi are well represented in this special issue, in acknowledgment of the pervasiveness and importance of informal networks in China and their relevance for network theory and practice. Other types of networks covered, in the Middle East and Southeast Asia, are excellent examples for understanding informal governance in emerging markets and their respective business culture more thoroughly. Each of them represents a springboard for further research on informal networks in emerging markets. We have organized the order we discuss the manuscripts below by country or region, starting with three contributions on China, followed by Iran, the Arab Middle Eastern region and Malaysia. We briefly describe the contributions to the special issue as follows.

Based on institutional logics theory, Xi Chen in her contribution entitled ‘The State-Owned Enterprise as an Identity: The Influence of Institutional Logics on Guanxi Behavior’, explores the organizational factors that might influence the guanxi behavior of employees at Chinese publicly listed firms, joint ventures, and state-owned enterprises (SOEs). On the bright side, guanxi behavior can lead to greater trust among individuals, sociability, and a sense of belonging. It can also positively influence career development. On the dark side, the effects of guanxi include favoritism, particularism, abuse of power, and exclusion. Chen found that guanxi behavior is connected to a collectivistic identity at Chinese SOEs. As guanxi behavior seems to be connected to the socialist institutional logic of SOEs, institutional transition can be challenging.

By exploring the role of business expatriates in China, Shuang Ren, Doren Chadee, and Alfred Presbitero assess in their study titled ‘Influence of Informal Relationships on Expatriate Career Performance in China: The Moderating Role of Cultural Intelligence’, the dependence of expatriates’ career performance based on their ability to develop guanxi with local employees. They show the positive effect of guanxi on expatriate performance, linked to the level of their awareness about cultural norms and values in China. The expatriates studied come from the United States, France, South Korea, and Taiwan and manage foreign enterprises in Beijing and Shanghai. The evidence suggests that the prevalence and persistence of guanxi influence is found not only among the Chinese managers (Bian, Reference Bian2018, Reference Bian2019) but also among expatriate managers working in an increasingly globalized China. Although this study offers a timely analysis about the importance of culturally specific social capital in expatriate career development and performance, it makes a larger point about the need to understand the extent to which the interplay of informal networks and cultural intelligence facilitates and affects globalized enterprises in locations with operational relevance.

Staying with China, Katarzyna Burzynska and Sonja Opper analyze in ‘Interbank Relations, Environmental Uncertainty, and Corporate Credit Access in China’ how informal banking networks in China help a company to secure new bank loans, if it has prior loans. As the findings in this study confirm that close-knit banking networks facilitate access to credit, the question of whether these networks are good or bad becomes critical. On the bright side, after banks obtain more information on the borrower, they can reduce the risks of lending. In addition, reliable borrowers have better access to loans, as shown by the study results. On the dark side, banking networks lack transparency in terms of creditor evaluation criteria, and they can bias competition, as it is unclear whether the best firms end up with the most advantageous banking networks. Moreover, the risk of political interference remains, adding yet more bias. These findings are based on an analysis of a large number of publicly listed corporations on China's stock market and advance our understanding about how the interplay between informal networks and network embeddedness both facilitates and constrains business strategies by Chinese corporations.

We now shift focus to the Middle East, which we recognize is diverse, having similarities and differences such as the fact that some countries are predominantly Arabic while Iran practices Shi'a Islam. Two studies in this special issue analyze, respectively, Iranian bazaaries and wasta. Marina Apaydin, Jon Thornberry, and Yusuf M. Sidani refine the Uppsala internationalization model by exploring how informal networks can help firms to internationalize in their article on ‘Informal Social Networks as Intermediaries in the Foreign Markets’. They use the case of Iranian bazaaries, an important resource that is similar to guanxi in China, and define them as ‘a cohesive homogenous group of Shia merchants historically proven being capable of an economic or even political action’. They are seen as the main actors and gatekeepers of economic activity in Iran. Enriched by the historical context of the bazaaries, this study illustrates the present-day ways in which they influence the process of internationalization. The study suggests that bazaaries could play an important intermediary role at multinational enterprises (MNE) in the internationalization process and have a positive impact on performance, if not survival, of MNE subsidiaries in Iran. This is especially the case where the leadership of MNEs faces constraints due to Shi'a Islam. Bazaaries in Iran show similarities to other forms of brokerage and informal networks such as guanxi and yongo. On the bright side, they facilitate team spirit, cooperation, and loyalty. On the dark side, they are prone to bribery, cronyism, and corruption.

In the article entitled ‘Wasta: Advancing a Holistic Model to Bridge the Micro-Macro Divide’, Sa'ad Ali and David Weir revisit the definitions of wasta and review the extant literature on it. They reveal the multidimensional nature of wasta, which is used in the Middle East and is interpreted, on the one hand, as a structure, and, on the other hand, as a process embedded in distinctive values and morals of behavior. Thus, wasta can represent a clan structure as well as a process of mediation, for example, settling disputes between families. Because the notion of wasta is closely tied to family and clan affairs, including strong obligations to benefit an immediate and extended family, wasta is by nature exclusive. In addition, distributing resources and benefits to in-groups is time consuming, costly, and might be ethically questionable because people without wasta are left out. The bright side of wasta is its high family and clan cohesion, which gives its members protection and security.

Even less research on informal ties and networks has covered Malaysia, in particular the role played by directors’ networks in the capital market. In their study, Effiezal Aswadi Abdul Wahab, Mohd Faizal Jamaludin, Dian Agustia, and Iman Harymawan investigate the relationship between directors’ networks and accruals quality as a proxy for earnings. In the paper entitled ‘Director Networks, Political Connections and Earnings Quality in Malaysia’, the authors find that politically connected directors’ networks negatively influence firms’ accruals quality. Networks created by directors exert managerial influence, lead to board directorship overload, and prevent effective monitoring. However, although the results are significant for politically connected directors, this is not the case for directors with no political connections. The authors speculate that having politically connected directors on the board can be seen as liability for the firm.

DISCUSSION AND OUTLOOK

Theoretical debates on informal networks have been dominated by the neoinstitutionalist literature (e.g., North, Reference North1990), including transaction cost economics (e.g., Williamson, Reference Williamson1979, Reference Williamson1996) and sociological research on social capital (e.g., Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu and Richardson1986; Granovetter, Reference Granovetter1973, Reference Granovetter1995; Putnam, Reference Putnam1993). However, the theories on informal networks that resulted from these multidisciplinary efforts over the years suffer from incompleteness and inconsistency. In response, we point out five major omissions or avenues for future research to advance knowledge on informal networks, as follows.

Conceptual Inconsistency Needs to Be Reduced in Discipline-Based Approaches and Area Studies Findings

According to Granovetter (Reference Granovetter1973, Reference Granovetter1995), weak ties are of particular value to an individual and are important in acquiring information or a job. But in East Asia, informal networks (e.g., guanxi or yongo) are often based on strongly personalized social ties, which are emotional and less instrumental, and may or may not be kinship based (Li, Reference Li2012; Luo, Reference Luo2000). The same applies to wasta in Arab countries, where the family, which includes the extended family and, up to a point, even a tribe, plays a dominant role (Khalaf & Khalaf, Reference Khalaf and Khalaf2008). These differences raise doubt that current definitions of informal networks are universally valid and, instead, indicates that they are content bound, in which their validity is limited by the context. Thus, there are differences in the conceptualization of informal networks in the West and elsewhere (e.g., Russia, East Asia, Southeast Asia, the Middle East and the Arab Middle East). In addition, much of the network research focuses on either network dyads (guan in guanxi) or network structure (xi in guanxi), as pointed out by Li et al. (Reference Li, Zhou, Zhou and Yang2019). Research on informal networks would benefit by integrating these two perspectives. To understand how informal networks develop and change over time requires more process-oriented and time-series informal network research.

Knowledge Construction

At present, the general knowledge about informal network constructs is rather thin. Recent research points out that social capital and network theories have been developed almost exclusively by Western scholars based on thinking about typical Western social ties and networks and do not take into account the character and nature of informal social ties and networks in other parts of the world and the way in which they are formed. To date, international business studies have largely neglected many other informal networks as a focus of research, with the exception of guanxi (China). However, it would be difficult for theory development to achieve greater generalizability without taking them into account. The current state of knowledge on informal ties in the international business field, other than research on guanxi, is low with respect to svyazi (Russia), yongo (South Korea), jinmyaku and gakubatsu (Japan), wasta (Arab countries), jaan-pehchaan (India), and jeitinho (Brazil). The field would benefit from comparative studies to compare and contrast informal networks across countries, beyond comparisons of guanxi and blat (Ledeneva, Reference Ledeneva2008) and yongo and guanxi (Horak & Taube, Reference Horak and Taube2016). As shown by Jiang et al. (Reference Jiang, Liu, Fey and Wang2019) and others, not all networks behave the same way, yet the tendency has been to view informal networks in one country in terms of a undifferentiated pattern. No studies of regional variation have been conducted (Putnam, Reference Putnam1993). More attention in research should be paid to the membership in networks – suppliers, customers, government, influential people whose utility to the firm is not yet clear, etc. – and how this affects how they work. Future research would also benefit by considering the effect of individual characteristics, such as a person's big five personality ratings, on how they work in a network or how a network should be designed to enable a person with certain characteristics to work best. Further, future studies on networks should explore how people's position at their firm affects how their external informal network works and how informal networks operate at organizations that are more decentralized.

Formal–Informal Institutional Interaction

Formal and informal institutions interact and thus determine each other's effectiveness (North, Reference North1990; Pejovich, Reference Pejovich1999). However, institutional interaction and the resulting co-evolution is a challenging theme. Because of the lack of empirical studies, the nature and operating modes of the linkages between informal and formal institutions and their interaction and influence on each other's developmental direction are an important yet poorly understood topic (Hodgson, Reference Hodgson2002). Either cultural or institutional dynamics or both play a role, but the precise role may differ across regions. Tracing this process in different regions would add to overall understanding of the effectiveness of formal institutions and the evolution of both formal and informal institutions. Future research would also benefit from exploring interaction between formal networks and informal networks, networks within a firm and external to a firm, and how these relationships change when organizational boundaries are blurred.

Persistence of Informal Networks

Since the 1990s, Western scholars have speculated about whether informal networks that dominated communist regimes would persist or decline in post-communist countries. In the twentieth century, it was assumed that with greater economic advancement and the creation of more formal institutions would come less reliance on informal relationships. However, because of the emergence of the gig economy and the increasing complexity introduced by new technologies in the twenty-first century, researchers envisage that, even in industrialized countries with stable formal institutions, informal networks function as channels for economic coordination and play other important roles as well (Horak & Klein, Reference Horak and Klein2016; Horak & Taube, Reference Horak and Taube2016). Further research is needed to clarify variations in the persistence of informal networks across countries as well as explore the potential of informal networks in Western countries, where their role has not been highlighted. Informal networks might play a similar role in all countries, with their configuration, functions, and scale determined by the context. To date, no comprehensive studies have been conducted to support or reject this hypothesis.

Ethical Considerations

Multinational corporations (MNCs) operate in contexts that are rife with informal networks in markets worldwide. However, little academic research shows how MNCs manage informality – that is, whether they have systemic processes for managing informal ties, as reported by Kim (Reference Kim2007) at Samsung, or whether these ties are hidden, taken for granted, discreetly avoided, or intentionally ignored. Although MNCs may be vertically integrated, the social environment in which they operate is heavily shaped by informal culturally embedded institutions (Berger et al., Reference Berger, Herstein, McCarthy and Puffer2019). MNCs must therefore take a stand on their involvement in informal networking. Their ethical code needs to address the two aspects of informal networks –positive and negative – and determine which strategies are best for addressing them.

CONCLUSIONS AND TOPICS FOR FURTHER STUDY

The articles in this special issue contribute to increased awareness of informal networks, their functional ambivalence, and context-bound influence. The authors specify the dark and bright sides of informal networks and their modes of operation in different countries. Several case studies illustrate the Janus-faced nature of informal networks. First, they can increase efficiency and decrease costs by circumventing bureaucratic formal procedures, facilitating competitive advantage, yet expose their members to the risks of favoritism, collusion, abuse of power, and other forms of corruption, in which the advantage of one is achieved at the expense of others. Second, the opportunity costs of the use of informal networks may be detrimental to business, because the reverse side of competitive advantage is often associated with complacency or reliance on extant informal relationships, rather than efforts at innovation to explore other, potentially more lucrative opportunities. Third, informal networks are ambivalent. On the one hand, they promote sociability and social cohesion but only toward insiders. On the other hand, they are exclusive of outsiders, hence those without informal ties may lack access to crucial benefits, such as jobs, career advancement, and information.

A more detailed understanding of how to reduce inequality and channel access to information and resources for out-groups, informal networks can be usefully differentiated based on the nature and degree of their exclusivity. For some networks, family ties are the defining characteristic (e.g., clannism or guanxi), and for other networks, clan ties are the dominant defining factor and becoming a member of that group is only possible by acquiring clan membership (e.g., wasta). Given the variety of determinants and multiplicity of avenues that shape informal networks, a uniform cross-country approach is unlikely to be found. As our case studies show, the workings of informal networks differ significantly and are embedded in particular national institutional frameworks and regional cultures. However, certain commonalities and differences can be identified. There is great value in a comparative, yet context-specific study of informal networks across different countries. Explicitly including more than one country in a study of informal networks highlights both universal patterns and specific features, which advance our overall understanding of informal networks.

From a managerial point of view, embracing the hidden dimensions of the workings of informal networks can facilitate decision-making and context-sensitive policies. Ensuring transparency and developing explicit policies on how to deal with informal networks in order to diminish the dark side effects of informal networks, while keeping the bright side effects on the organizational behavior, are critical.

Although the articles in this special issue add valuable knowledge, more research is needed to address the broader theoretical themes highlighted in this discussion and to explore the practical implications of research on informal networks. First and foremost, deeper and broader construct knowledge is needed to develop a connection to informal networks in respective countries (for a comprehensive overview of informal network types, see Ledeneva et al., Reference Ledeneva, Bailey, Barron, Curro and Teague2018). Further, questions to be explored in a comparative, yet context-bound context could include – (i) How can informal networks be characterized so that they are comparable yet considered in a culturally specific setting? (ii) What features and modes of operation comparable? (iii) How can firms and managers draw on the positive aspects of informal networks, without the risks of noncompliance with the norms of legal, moral, and responsible behavior? (iv) How can informal networks be researched empirically, and what research designs are best suited for satisfying the replicability requirements? The informal network field could also benefit by continuing to explore additional theoretical lenses. For example, future research could consider the use of informal routines (Feldman, Reference Feldman and Pentland2003), which are anchored in bounded rationality and include the logic of appropriability and consequentiality (the expected consequences).

Whether we apply the formal/informal institutional lens or regard them as metaphors, how formal and informal institutions interact and influence each other remain a black box. We shed some light on the dimensions and related dynamics in the formal/informal dichotomy, but more research is needed to comprehend the longevity of informal networks. As informal networks are not likely to disappear with the creation of formal institutions and their development to higher levels of effectiveness, how do they affect and adjust to the formal frameworks? Are informal networks less prevalent or less studied in Western countries? What features of informal networking persist in mature democracies and well-functioning markets? The evidence that informal networks persist is overwhelming, yet at the firm level, they are often taken for granted. Firms and their employees, particularly expatriates and policy makers at the firms’ headquarters, need to be trained and understand how to govern informal ties, how to become integrated into informal networks, how to influence informal networks, and how to transform them by enhancing their bright side while monitoring the risks of their dark side.

Research on informal networks is interdisciplinary, with a great deal of potential for collaboration across disciplines. At present, it appears that knowledge has been developed in parallel with disciplinary silos, mostly in sociology, political science, and international business studies. Research on the characteristics and operational modes of, for instance, blat/svyazi is quite advanced in social anthropology and political science, but less developed in international business (notable exceptions are Puffer and McCarthy, Reference Puffer and McCarthy2011; Minbaeva et al., forthcoming). Because politics plays a much greater role in many emerging markets than in the market-based liberal democracies in the West, the studies on such natural experiments, revealing the hidden dimensions of emerging markets, can be used as a basis for further comparative research and experimentation. East-West collaborations and cross-regional studies are needed to channel knowledge, verify the findings in various social sciences, and test their applicability in practice.

APPENDIX I

Summary of Quantitative Network Articles Referred to in this Article

APPENDIX II

Summary of Qualitative Network Articles Referred to in this Article