INTRODUCTION

Since the end of the first decade of the 21st century, emerging market firms (EMFs) have become major players in the global economy, which has increased the scholarly attention to those firms that have engaged in value-added activities beyond their national borders (Gammeltoft, Pradhan, & Goldstein, Reference Gammeltoft, Pradhan and Goldstein2010; Gonzalez-Perez, Manotas, & Ciravegna, Reference Gonzalez-Perez, Manotas and Ciravegna2016; Luo & Bu, Reference Luo and Bu2018). Within the last two decades, developing and emerging countries have increasingly attracted international investment, even surpassing developed economies. According to UNCTAD (2019), from 2007 to 2018, 58 percent of the global inward foreign direct investment (FDI) flow was captured by emerging and developing nations; while developed economies received just 40 percent of the global inward FDI in the same period. In the case of Latin America and the Caribbean, just in 2019, FDI grew by 10.3 percent, representing 10.7 percent of the world share; countries like Brazil, Colombia, and Chile experienced FDI grow greater than 20 percent (UNCTAD, 2020). Despite this change in FDI flows, firms originating in emerging markets are still underrepresented in scholarly publications, meanwhile, empirical studies of firms from the United States, Europe, and Japan are still largely covered (Ciravegna, Lopez, & Kundu, Reference Ciravegna, Lopez and Kundu2016).

Scholarly discussion based on empirical evidence from Latin America is even more scarce; furthermore, nascent literature neither fully captured the special competitive conditions nor satisfactorily explained the behavior of these firms (Aguilera, Ciravegna, Cuervo-Cazurra, & Gonzalez-Perez, Reference Aguilera, Ciravegna, Cuervo-Cazurra and Gonzalez-Perez2017; Cuervo-Cazurra, Narula, & Un, Reference Cuervo-Cazurra, Narula and Un2015). And most of the studies (e.g., Cuervo-Cazurra et al., 2018; Fiaschi, Giuliani, & Nieri, Reference Fiaschi, Giuliani and Nieri2017; Gonzalez-Perez & Velez-Ocampo, Reference Gonzalez-Perez and Velez-Ocampo2014) analyze Latin American companies that have already engaged in foreign value-added activities and FDI. However, Latin American firms with some international experience, for instance in the form of exports and sales subsidiaries, that are still in pre-FDI stages remain understudied.

International expansion is a complex and paradoxical process for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) originating in emerging markets (Li, Li, & Dalgic, Reference Li, Li and Dalgic2004). On the one hand, EMFs are encouraged to increase their exports and international presence because of the perceived gains in innovation and competitiveness (Nuruzzaman, Singh, & Pattnaik, Reference Nuruzzaman, Singh and Pattnaik2018). Besides, EMFs are fast learners (Luo & Bu, Reference Luo and Bu2018) that also exhibit higher adaptability and resilience (Guillén & García-Canal, Reference Guillén and García-Canal2009), and are frequently better prepared to operate in demanding and conflictive environments (Fiaschi et al., Reference Fiaschi, Giuliani and Nieri2017). On the other hand, EMFs also have structural disadvantages at home that hinder their international endeavors (Mesquita & Lazzarini, Reference Mesquita and Lazzarini2008). Such barriers are classified as internal and external constraints to expanding internationally (Leonidou, Reference Leonidou2004). On the internal side, the main internationalization barriers include lack of international experience and managerial talent (Vendrell-Herrero, Gomes, Mellahi, & Child, Reference Vendrell-Herrero, Gomes, Mellahi and Child2017) and insufficient organizational capabilities to offer products or services to compete internationally (Ribeiro, Lahiri, & Mendes, Reference Ribeiro, Lahiri and Mendes2015). Meanwhile, external obstacles entail unsophisticated and unstable institutions (Madhok & Keyhani, Reference Madhok and Keyhani2012), negative country-of-origin effects (Ciravegna, Lopez, & Kundu, Reference Ciravegna, Lopez and Kundu2014; Vidaver-Cohen, Gomez, & Colwell, Reference Vidaver-Cohen, Gomez and Colwell2015), and inadequate export incentives (Azzi da Silva & Da Rocha, Reference Azzi da Silva and Da Rocha2001).

Previous research covering the international expansion of EMFs originating in Latin America has covered different areas. For instance, Mesquita and Lazzarini (Reference Mesquita and Lazzarini2008) analyzed how relational governance helps SMEs overcome structural deficiencies and access global markets. More recently, Ribeiro et al. (Reference Ribeiro, Lahiri and Mendes2015) classified internationalization barriers of new technology-based companies. Similarly, Bianchi, Carneiro, and Wickramasekera (Reference Bianchi, Carneiro and Wickramasekera2018) analyzed the drivers and inhibitors of international commitment. While Ciravegna et al. (Reference Ciravegna, Lopez and Kundu2014) compared the country-of-origin effects and the network building mechanisms in the international expansion of a set of Latin American and European SMEs, and Fabian, Molina, and Labianca (Reference Fabian, Molina and Labianca2009) contrasted the decision-making rationale of SMEs that decide to internationalize and those that prefer to remain local.

As observed in these studies, previous research on the internationalization of Latin American firms has relied heavily on either companies that have already engaged in FDI activities (also known as multilatinas) (Hennart, Sheng, & Carrera, Reference Hennart, Sheng and Carrera2017) or in the analysis of drivers and obstacles that Latin American SMEs face when expanding abroad (Bianchi et al., Reference Bianchi, Carneiro and Wickramasekera2018; Ribeiro et al., Reference Ribeiro, Lahiri and Mendes2015). However, little has been said about the mechanisms that EMFs in pre-FDI stages use to tackle the challenges associated with their origin that affect their international expansion. Thus, we aim to answer this research question: How do EMFs in pre-FDI stages deal with the challenges and obstacles associated with their origin and their incipient international expansion?

There are two main reasons that both support and prompt the study of how EMFs in pre-FDI stages handle internal and external challenges to compete internationally. First, although since the 1990s several Latin American countries have implemented economic liberalization policies (Dominguez & Brenes, Reference Dominguez and Brenes1997), the region still suffers from macroeconomic imbalances, debt crisis, and political risk that prevents domestic firms from exploring international markets (Ciravegna et al., Reference Ciravegna, Lopez and Kundu2016). Additionally, deficiencies in infrastructure and logistics, exchange-rate volatility, and export dependency on commodities have negatively influenced the evolution of foreign trade in the region during the last three years (ECLAC, 2019). These contextual conditions discourage companies in the region from exporting so that less than 15 percent of all firms have sales outside their country of origin (Lederman, Messina, Pienknagura, & Rigolini, Reference Lederman, Messina, Pienknagura and Rigolini2014). In other words, Latin American firms in pre-FDI stages are scarce and the scholarly understanding of their behavior is still limited. Understanding such mechanisms has implications for other business practitioners and export promotion agencies alike, as they would recognize how companies in similar situations have dealt with liabilities associated to their origin and their lack of international exposure.

EMFs that are actively engaged in exports and international sales subsidiaries might remain at this internationalization stage for long periods of time and some of them do not consider FDI an option. International business (IB) is a multiparadigmatic field (Sullivan & Daniels, Reference Sullivan and Daniels2008), and IB theories have shifted from studying country competitiveness to the behavior of MNEs and the linkages between parent MNEs and subsidiaries (Rugman, Verbeke, & Nguyen, Reference Rugman, Verbeke and Nguyen2011). However, the theorization of companies that have not engaged in foreign value-added activities is still incipient. This lack of empirical evidence of EMFs in pre-FDI stages leaves room for explanatory and contextualized contributions that offer theoretical propositions that could be eventually tested in different emerging markets. Therefore, this study represents an opportunity not only to contextualize international business (IB) research as advocated by Teagarden, Von Glinow, and Mellahi (Reference Teagarden, Von Glinow and Mellahi2018), but also to extend the theoretical lenses to observe internationalization of EMFs.

And second, as several authors have stated (Aguinis et al., Reference Aguinis, Villamor, Lazzarini, Vassolo, Amorós and Allen2020; Luo & Zhang, Reference Luo and Zhang2016), the special conditions of EMFs imply that they could be used as a laboratory to extend IB theory and better comprehend the behavior of indigenous firms. In this particular case, our findings contribute to the contextualization of liability of emergingness (LOE), which Madhok and Keyhani (Reference Madhok and Keyhani2012) refer to as the disadvantages that EMFs experience when expanding overseas because of their origin, and also to the analysis of the linkages between international expansion and corporate reputation in the context of Latin America, a relationship in which recent studies highlighted that further analysis was required (e.g., Borda, Geleilate, Newburry, & Kundu, Reference Borda, Geleilate, Newburry and Kundu2017; Thams, Alvarado-Vargas, & Newburry, Reference Thams, Alvarado-Vargas and Newburry2016; Vidaver-Cohen et al., Reference Vidaver-Cohen, Gomez and Colwell2015). Besides, the novelty of this study is also related to the jointed analysis of international expansion decisions, obstacles and patterns, and the difficulties associated with the lack of credibility and even negative corporate reputation in international markets, which are traits that could be useful when observing the behavior of EMFs from different countries of origin.

To answer our research question, we analyzed 10 firms that have not been academically studied before, and that, unlike many other Latin American firms, do not base their international expansion on the exploitation of natural resources but on the exploitation of their firm-specific advantages (FSAs). The next section of this article provides a theoretical context of the international expansion of EMFs and introduces Jaguar firms’ characteristics. We then describe methodological considerations, including transparency criteria, selection of cases, and data collection. Finally, we present our findings and conclusions in which we formulate propositions and draw implications for future research.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

There are several conceptual differences between EMFs and multinational enterprises (MNEs); the former term highlights companies that originated in emerging markets (Jormanainen & Koveshnikov, Reference Jormanainen and Koveshnikov2012), while the latter indicates companies that have engaged in valued-added activities internationally (Cuervo-Cazurra, Reference Cuervo-Cazurra2007), therefore, EMFs might or might not engage in FDI. Moreover, EMFs might possess ambidexterity, adaptability, and proximity to customers (Luo & Bu, Reference Luo and Bu2018), and could suffer from home-market institutional voids, unsophisticated capabilities, and credibility deficit (Madhok & Keyhani, Reference Madhok and Keyhani2012). Conceptually, the term EMFs includes both companies in pre-FDI stages and firms that have already become MNEs; however, for the purpose of this article we are analyzing just those that have not engaged in FDI activities, which, as Hernandez and Guillén (Reference Hernandez and Guillén2018) argue, represent an opportunity to grasp empirical evidence and better understand the ‘emerging’ stage of EMFs.

EMFs not only need to deal with structural disadvantages of their home countries but also face legitimation and reputation issues that often hinder their internationalization endeavor (Fiaschi et al., Reference Fiaschi, Giuliani and Nieri2017). Therefore, EMFs often use their internationalization as a mechanism to upgrade internal capabilities (Thams et al., Reference Thams, Alvarado-Vargas and Newburry2016). Such new capabilities support these companies in overcoming two weaknesses: their lack of competitive strengths associated with their unsophisticated markets of origin (Estrin, Meyer, & Pelletier, Reference Estrin, Meyer and Pelletier2018; Petrou, Reference Petrou2007), and their lack of favorable reputation in international markets (Vidaver-Cohen et al., Reference Vidaver-Cohen, Gomez and Colwell2015).

EMFs’ Drivers and Obstacles to Expand Internationally

According to Buckley and Casson (Reference Buckley and Casson2009), firms that possess FSAs gain competitive advantage when operating internationally by using them within the boundaries of the firm, mainly due to market imperfections of intermediate products. However, several authors (e.g., Ramamurti, Reference Ramamurti, Ramamurti and Singh2009; Witt & Lewin, Reference Witt and Lewin2007) argue that EMFs might lack FSAs and that they undergo international expansion as a way to both learn best practices and escape their home country poor conditions (Cuervo-Cazurra et al., Reference Cuervo-Cazurra, Narula and Un2015).

EMFs usually lack knowledge-based advantages (Casson, Dark, & Gulamhussen, Reference Casson, Dark and Gulamhussen2009); instead, these firms develop home-born, knowledge-based advantages linked to their proximity to natural resources, privileged access country specific advantages at home-nation, low production costs, knowledge of local customers, political know-how, and adaptability to markets with institutional constraints (Cuervo-Cazurra & Ramamurti, Reference Cuervo-Cazurra and Ramamurti2014). Regarding motivations to internationalize, Guillén and García-Canal (Reference Guillén and García-Canal2009) claim that some of the reasons for EMFs to engage in FDI are spreading risk, following local clients, escaping home-government unfavorable regulations, and acquisitions of FSAs. Nevertheless, as noted by Verbeke and Kano (Reference Verbeke and Kano2015), a detailed analysis of these reasons leads to the inference that the evident linkages between EMFs' reasons to internationalize and the four traditional motivations to expand overseas already covered in the literature: market seeking, strategic-resource seeking, efficiency-seeking, and natural-resource seeking (Dunning, Kim, & Park, Reference Dunning, Kim and Park2008).

Peng, Wang, and Jiang (Reference Peng, Wang and Jiang2008) argue that institutions have the greatest effect on enterprise strategy and performance. Underdeveloped institutions generate higher transaction costs and reduce efficiencies in market-based exchanges. Nevertheless, underdeveloped and unstable institutions usually characterize emerging economies (Cuervo-Cazurra, Reference Cuervo-Cazurra2012). This encourages firms to generate more ambitious international strategies, originating three resulting processes. First, EMFs invest abroad to escape the constraints of home country institutions and to overcome the negative reputation associated with their country of origin. Second, institutional reforms in emerging economies are attracting foreign and often developed countries firms to compete with local firms, which encourages EMFs to increase their international commitment to avoid competition and reduce risks. And third, as institutional voids create higher transaction costs for EMFs, they favor the association in business groups that usually implies access to resources, capital, labor, and international experience (Gaur, Kumar, & Singh, Reference Gaur, Kumar and Singh2014). These factors are linked to the four internationalization motivations for EMFs to invest internationally (Cuervo-Cazurra & Narula, Reference Cuervo-Cazurra and Narula2015; Cuervo-Cazurra et al., Reference Cuervo-Cazurra, Narula and Un2015).

There are different classifications of obstacles of EMFs to expand internationally. For instance, Madhok and Keyhani (Reference Madhok and Keyhani2012) explain that these companies not only suffer from the so-called liability of foreignness (LOF) (Zaheer, Reference Zaheer1995, Reference Zaheer2002) but also from LOE. EMFs ‘face an additional burden and confront specific challenges, especially in advanced economies, simply by being from emerging economies’ (Madhok & Keyhani, Reference Madhok and Keyhani2012: 30). While LOF applies to all firms because of their non-local situation (irrespective of their origin), LOE is a sort of handicap to firms from emerging markets. LOE occurs mainly for three reasons: first, due to mixed conditions (poor infrastructure, unsophisticated local customers, weak formal institutions) that create institutional voids and undermine competitiveness; second, because of their managerial and capabilities weaknesses; and third, the deficit in terms of credibility and legitimacy assessed by foreign stakeholders. The lack of legitimation and a poor reputation in international markets is a problematic situation for EMFs (Fiaschi et al., Reference Fiaschi, Giuliani and Nieri2017). Moreover, when those EMFs are also international new ventures (INVs), they often face two other liabilities: liabilities of newness/inexperience and liabilities associated with their small size (Zahra, Reference Zahra2005).

With regard to the particular international expansion barriers of EMFs in pre-FDI stages, different studies demarcate between internal and external obstacles. Internal obstacles include lack of knowledge and innovation capabilities (Azzi da Silva & Da Rocha, Reference Azzi da Silva and Da Rocha2001), unprepared talent and lack of organizational capabilities (Ribeiro et al., Reference Ribeiro, Lahiri and Mendes2015), and the shortage in working capital and marketing deficiencies (Leonidou, Reference Leonidou2004). While external obstacles comprise institutional voids associated with underdeveloped regulatory frameworks (Ribeiro et al., Reference Ribeiro, Lahiri and Mendes2015), inadequate governmental incentives (Azzi da Silva & Da Rocha, Reference Azzi da Silva and Da Rocha2001), and negative country-of-origin effects (Ciravegna et al., Reference Ciravegna, Lopez and Kundu2014).

International Expansion in the Latin American Context

According to Cuervo-Cazurra (Reference Cuervo-Cazurra2012), academic interest in studying the internationalization of companies from emerging markets coincides with the bold international growth of companies such as Huawei, Tata, Embraer, Bimbo, and CEMEX, after the year 2000. As already mentioned, in the case of Latin America most of the studies on international expansion and FSAs relevant to their internationalization have taken into consideration large companies (Bandeira-de-Mello, Fleury, Aveline, & Gama, Reference Bandeira-de-Mello, Fleury, Aveline and Gama2016; Bianchi, Reference Bianchi2014; Parente, Cyrino, Spohr, & Vasconcelos, Reference Parente, Cyrino, Spohr and Vasconcelos2013; Velez-Ocampo, Govindan, Gonzalez-Perez, & Herrera-Cano, Reference Velez-Ocampo, Govindan, Gonzalez-Perez and Herrera-Cano2017); however, studies that analyze smaller firms in earlier stages of international expansion are not so common (e.g., Ciravegna, Lopez, & Kundu, Reference Ciravegna, Lopez and Kundu2014; Gonzalez-Perez, Velez-Ocampo, & Herrera-Cano, Reference Gonzalez-Perez, Velez-Ocampo and Herrera-Cano2018).

Regional governments and institutions have played a central role in the internationalization of small and large firms alike. Until the 1980s, import substitution policies were implemented to protect local economies and national sovereignty; however, more recently, local governments have counterbalanced the economic openness that allowed foreign competitors with support plans to selected firms with international proclivity (Fleury & Fleury, Reference Fleury and Fleury2011; Hennart et al., Reference Hennart, Sheng and Carrera2017). The role of local government in the international expansion of Latin American companies is far from homogeneous. Within the last 30 years, there have been pro-market reforms and reversals (Cuervo-Cazurra, Reference Cuervo-Cazurra2016) that generated macroeconomic imbalances between and within countries (Ciravegna et al., Reference Ciravegna, Lopez and Kundu2016). Furthermore, shared reputational value, which encompasses both country and corporate reputation, is less likely to produce positive outcomes in the context of regions with political instability and high volatility like Latin America (Kelley, Hemphill, & Thams, Reference Kelley, Hemphill and Thams2019).

Institutional sophistication levels also vary significantly across Latin American countries; therefore, institutional uncertainty affects the internationalization of companies from different Latin American countries. For instance, elements like price interventions by local governments and vulnerability to product imitation without effective governmental controls are sources of concern for local and foreign companies operating within the region (Andonova & Losada-Otálora, Reference Andonova and Losada-Otálora2018). Additionally, within the last few years, there are some elements that have delved the difficulties for regional companies to internationalize, like unresolved private and public corruption practices, the lack of generalized competitiveness and innovation, and the vulnerability to global economic slowdown (Spillan & Ramsey, Reference Spillan and Ramsey2019).

Regarding international expansion decisions of Latin American firms, the exploitation of natural resources and search for larger markets has traditionally boosted their international presence (Gonzalez-Perez et al., Reference Gonzalez-Perez, Manotas and Ciravegna2016; Losada-Otálora & Casanova, Reference Losada-Otálora and Casanova2014). In spite of the profound differences in terms of economic and social development between and within Latin American countries and considering that the exploitation of natural resources is still the most predominant business activity for large MNEs, these companies are now changing their business practices to adopt more sustainable uses of natural resources (Majano & Pérez-Pineda, Reference Majano, Pérez-Pineda, Jäger and Sathe2014). The shift to more sustainable business practices even in extractive industries within Latin America is linked not only to social and political advancements but also to the international orientation and insertion in global value chains (Majano & Pérez-Pineda, Reference Majano, Pérez-Pineda, Jäger and Sathe2014).

In many cases, these firms do not possess clear competitive advantages and FSAs before their first international operation, but when they expand they also develop these advantages and later used them both internationally and domestically (Casanova, Reference Casanova2011). Aguilera et al. (Reference Aguilera, Ciravegna, Cuervo-Cazurra and Gonzalez-Perez2017) highlight four mechanisms that have influenced the international growth of Latin American firms. The first one corresponds to those firms that transformed from state-owned to private firms with strong ties to their local government; the second mechanism is used by companies that propelled their international expansion on home-market profits derived from advantageous regulatory conditions; the third driver includes those companies that took advantage of internal market development derived from deregulation and economic openness; while the last driver represents firms that signed alliances and partnerships with MNEs from developed economies to benefit from their expertise and gain credibility.

Related to this fourth mechanism, and considering that EMFs internationalize searching for legitimacy, which is enhanced when entering developed economies and contributes to generating credibility signaling at home (Meouloud, Mudambi, & Hill, Reference Meouloud, Mudambi and Hill2019), Borda et al. (Reference Borda, Newburry, Teegen, Montero, Nájera-Sánchez, Forcadell, Lama and Quispe2017) suggest that the combination of local embeddedness and foreign presence intensifies reputation assessments, especially in more open economies. Complementarily, Cuervo-Cazurra et al. (Reference Cuervo-Cazurra, Carneiro, Finchelstein, Duran, Gonzalez-Perez, Montoya, Reyes, Fleury and Newburry2019) analyze a set of Latin American firms that managed to develop uncommoditizing strategies based on innovation, efficiency, and coordinated control, which allow them to compete on the basis of high quality, premium pricing, and favorable reputation. Additionally, as country of origin acts as a predictor of corporate reputation, and Latin American countries' companies suffer from legitimacy when compared to either European or American enterprises (Vidaver-Cohen et al., Reference Vidaver-Cohen, Gomez and Colwell2015), there is a growing number of companies firmly implementing corporate social responsibility practices to reduce this liability and gain trust and support when operating internationally (Aya Pastrana & Sriramesh, Reference Aya Pastrana and Sriramesh2014).

Jaguar Firms

As already mentioned, previous research on the internationalization of Latin American EMFs has mainly centered on either the identification of drivers and obstacles that these companies meet when expanding abroad (Bianchi et al., Reference Bianchi, Carneiro and Wickramasekera2018; Ribeiro et al., Reference Ribeiro, Lahiri and Mendes2015) or in the analysis of internationalization strategies of companies that are already engaged in foreign value-added activities (Andonova & Losada-Otálora, Reference Andonova and Losada-Otálora2018; Conti, Parente, & de Vasconcelos, Reference Conti, Parente and de Vasconcelos2016). Moreover, other studies have covered more specific areas, such as the relationship between home-country institutions, state ownership, and internationalization of multilatinas (Hennart et al., Reference Hennart, Sheng and Carrera2017), the role of experiential knowledge, networks, and institutions in Latin American SMEs' integration in global value chains (McDermott & Pietrobelli, Reference McDermott, Pietrobelli, Epstein and Molina2017), and the extent to which Latin American business groups' diversification influences the multinationality performance relationship (Borda et al., Reference Borda, Newburry, Teegen, Montero, Nájera-Sánchez, Forcadell, Lama and Quispe2017).

Nevertheless, existing research insufficiently covers how EMFs in early stages of international expansion bear with the international expansion challenges linked to their country of origin and lack of international experience. And it is precisely at this point where this research lies by providing propositions on the mechanisms that these companies use when approaching international markets. Foreshadowing the findings of this study, Figure 1 introduces a summary of the above-mentioned theoretical background and also summarizes the characteristics of observed firms and the propositions that are further analyzed in the results and discussion sections.

Figure 1. Jaguar firms’ conceptualization

Note: Theoretical background boxes offer a summary of the literature review section, while Jaguar firm characteristics and propositions are introduced and discussed in the results and discussion sections.

The theoretical background box in Figure 1 provides a summary of our theory discussion and the existing research on drivers, obstacles, and contextual conditions that Latin American firms find when expanding internationally. The other two boxes condense the common features that we observed in the cross-case analysis of observed companies. Both Jaguar firm characteristics and propositions are further discussed in the findings and discussion sections.

What we label as ‘Jaguar Firms’ are those originating in Latin America that are in pre-FDI stages and share some traits that resemble the behavior of this protected and highly symbolic Latin American native wild cat. We identified these companies as tropic dwellers because of their decision to operate and exploit their capabilities mostly within the Latin American region and occasionally entering developed markets with the purpose of enhancing capabilities and surpassing strong international competitors at home. Similar to jaguars, these companies are camouflage masters, because of their abilities and strategies to disguise their country of origin and newness when operating abroad. We also gathered empirical evidence that points out these firms as solitary predators that avoid partnerships and strategic alliances unless they have the interest of enhancing their legitimacy and reputation. While these characteristics could be independently observed in other firms regardless of their origin, we argue that the simultaneous integration of the three of them and the contextual conditions of the emerging region where these companies operate offer novelty and uniqueness.

METHODS

We analyze the corporate reputation and decision-making process related to international expansion of 10 Colombian firms in pre-FDI stages using an explanatory case study methodology (Runfola, Perna, Baraldi, & Gregori, Reference Runfola, Perna, Baraldi and Gregori2017). This design was selected for several reasons. First, collecting and analyzing data from several sources provides the opportunity to contrast paradoxical evidence and conflicting realities while providing emerging theoretical perspectives that have passed through a verification process (Eisenhardt, Reference Eisenhardt1989; Jørgensen, Reference Jørgensen2014). Second, case studies emphasize the role of context while displaying the interconnection between the organization and its environment (Couper, Reference Couper2019; Tsang, Reference Tsang2013; Welch & Piekkari, Reference Welch and Piekkari2017). And third, analyzing multiple cases permits us to observe the variations behind decisions related to internationalization; furthermore, this design let each additional case replicate, disconfirm, or provide alternative explanations to corporate reputation management and international expansion decisions (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Reference Eisenhardt and Graebner2007; Yin, Reference Yin2014).

The internationalization of Latin American firms has traditionally relied on the exploitation of country-specific advantages (CSAs) rather than on FSAs (Cuervo-Cazurra et al., Reference Cuervo-Cazurra, Carneiro, Finchelstein, Duran, Gonzalez-Perez, Montoya, Reyes, Fleury and Newburry2019); with some exceptions, Latin American economies are still dependent on the production and export of natural resources (Aguilera et al., Reference Aguilera, Ciravegna, Cuervo-Cazurra and Gonzalez-Perez2017). Besides, there are fewer empirical studies on the international expansion of Colombian firms compared to those that observe firms from Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina (Gonzalez-Perez & Velez-Ocampo, Reference Gonzalez-Perez and Velez-Ocampo2014). For these reasons, we included Colombian cases of firms that are non-dependent on natural resources. Furthermore, as we were interested in the decision-making process, we selected cases in pre-internationalization that are willing to engage in FDI in the coming years. An analysis like this represents an ‘ideal setting to observe the development of capabilities’ (Hernandez & Guillén, Reference Hernandez and Guillén2018: 30).

Transparency Criteria

Different stages of qualitative research are subject to biases that need to be addressed to enhance trustworthiness and veracity (Fletcher, Massis, & Nordqvist, Reference Fletcher, Massis and Nordqvist2016). Case studies could be explored using different methods that respond to a variety of philosophical orientations, each of which present methodological, ontological, and analytical nuances (Welch, Piekkari, Plakoyiannaki, & Paavilainen-Mäntymäki, Reference Welch, Piekkari, Plakoyiannaki and Paavilainen-Mäntymäki2011). Although the criteria for assessing the quality of case studies in International Business is still a matter of discussion (Welch & Piekkari, Reference Welch and Piekkari2017), for the purposes of this study, we approached transparency and trustworthiness using several criteria. To assure construct validity, we used multiple sources of evidence, pre-established a chain of evidence, and provided early and frequent feedback to informants (Sinkovics, Penz, & Ghauri, Reference Sinkovics, Penz and Ghauri2008). To address internal validity we based interview questions on literature and compared empirical observations to theoretical expectations (Gibbert & Ruigrok, Reference Gibbert and Ruigrok2010; Yin, Reference Yin2014). Additionally, we labeled questions theoretically and used both synchronic and diachronic data source triangulation methods (Pauwels & Matthyssens, Reference Pauwels, Matthyssens, Marschan-Piekkari and Welch2004); the former refers to interviewing various participants with the same questions, while the latter consists of questioning the same participant on the same topic more than once.

To limit bias in data collection, we combined both retrospective and real-time or ongoing situations (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Reference Eisenhardt and Graebner2007). In addition, to reduce elite bias, we interviewed not only the founder or CEO but also at least two additional participants from different hierarchical levels, areas, groups, or geographies for each firm (Aguinis & Solarino, Reference Aguinis and Solarino2019). We also avoided single-source bias and achieved internal validity by triangulating data sources and evidence while taking advantage of opportunistic data collection (Eisenhardt, Reference Eisenhardt1989; Figueiredo, Reference Figueiredo2011). Additionally, while interviewing we took extensive observational notes that helped us get richer details. We audio-recorded each interview, and then transcribed and analyzed them immediately after conducting them. We also performed follow-up phone conversations and/or email communications to validate specific data.

Selection of Cases

We used a multi-staged process for selecting cases. First, we contacted Ruta N, a local governmental institution for science, technology, and innovation in Colombia, which provided information and let us participate in a training session with over 100 companies in pre-FDI stages. We were interested in studying just local firms, so we excluded subsidiaries of larger international companies. In addition, we also looked for firms that had some international experience (e.g., exports or sales subsidiaries abroad) but that have not engaged in FDI. We initially found 74 companies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria, and 32 of them were available for interviews. Then, with the assistance of three independent experts (one scholar and two consultants), we classified 19 companies as potential cases because of their representation of extreme, uncommon, and revelatory samples of observed phenomena (Yin, Reference Yin2014). As several case studies (e.g., Åkerman, Reference Åkerman2014; Riddle et al., Reference Riddle, Hrivnak and Nielsen2010; Stoian et al., Reference Stoian, Rialp, Rialp and & Jarvis2016), we followed the theoretical sampling logic for the selection of cases (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Reference Eisenhardt and Graebner2007).

Four companies in pre-FDI stages were initially selected and analyzed independently, to then add single cases until either theoretical saturation or infeasibility of new findings is achieved. A total of six cases were individually added to the initial ones, resulting in a multiple-case study among ten cases. The final number of cases is consistent with the recommendation of including between four and ten cases (Eisenhardt, Reference Eisenhardt1989).

Data Collection

This process also followed multiple stages. First, as recommended by several studies (e.g., De Massis & Kotlar, Reference De Massis and Kotlar2014; Doz, Reference Doz2011; Fletcher, Massis, & Nordqvist, Reference Fletcher, Massis and Nordqvist2016), a priori data collection protocols took into consideration multiple data types. Before interviewing the participants, we collected data from multiple sources: EMIS Benchmark, Passport, Legiscomex, the companies’ websites and reports, newspaper articles, and top manager speeches were the main sources of archival data. An initial independent case study was built to integrate relevant secondary information that let us understand the evolution of the firms.

Second, we interviewed founders and/or senior managers for each of the initial four firms. In this first round of interviews, we extended and clarified information from the previous secondary data collection. We selected some topics for guiding the interviews; however, as Rui, Cuervo-Cazurra, and Un (Reference Rui, Cuervo-Cazurra and Un2016), we also designed each interview protocol according to the interviewee profile. Every interview covered these topics/categories: (i) drivers to internationalize; (ii) international expansion patterns; (iii) obstacles to expanding internationally; (iv) firm resources, capabilities, and advantages; and (v) legitimacy and credibility building. Third, with the results of the first round of interviews, we adjusted the initial cases and proceeded to add other cases on a single basis until reaching theoretical saturation.

We then conducted the cross-case analysis that also included contrasting the cases to the theory. In this stage, and as recommended by Eisenhardt (Reference Eisenhardt1989), data collection and analysis were overlapped in an iterative process. Field notes and opportunistic data collection in business meetings, training sessions, and phone calls were also used to better grasp phenomena. Relevant observations were shared among the researchers and jointly analyzed for assuring the chain of evidence (Gibbert & Ruigrok, Reference Gibbert and Ruigrok2010). Triangulation in data collection and having multiple collaborators from the firms helped to avoid anecdotalism of getting findings from a few, well-chosen examples (Gibbert & Ruigrok, Reference Gibbert and Ruigrok2010; Silverman, Reference Silverman2006). Moreover, triangulation counterbalanced the weaknesses of a single data collection technique and produced multiple insights to the phenomenon of interest, which increases internal validity (Pauwels & Matthyssens, Reference Pauwels, Matthyssens, Marschan-Piekkari and Welch2004).

After that, we conducted the second and third rounds of interviews that included not only founders and senior executives but also employees in different roles, which helped us to get a broader look at the companies to avoid elite bias. Interviews were carried out over a 22-month period. Each interview ranged from 49 to 115 minutes. Furthermore, in the initial contact, we mentioned the objective and outcomes of the study and sent out a letter detailing the approach, length, and broad topics to be covered in the interview, just as De Massis and Kotlar (Reference De Massis and Kotlar2014) did in their study.

We retrospectively tracked the evolution of the firms’ international expansion from their inception until 2016, and actively from 2017 to 2020. As is usual in case study methodology, data collection and analysis overlap in an iterative process (Eisenhardt, Reference Eisenhardt1989; Lokke & Sorensen, Reference Lokke and Sorensen2014). Archival data were collected before and after each round of interviews. Evolving from collected secondary data to interview insights implied contrasting initial secondary cases with empirical evidence using theoretical lenses. To do so, data reduction, display, categorization, and contextualization was conducted.

Data Analysis

We conducted the data analysis following the iterative process inspired in a coding scheme that assures the data chain of evidence (Gibbert & Ruigrok, Reference Gibbert and Ruigrok2010; Yin, Reference Yin2014). As in Rindova et al. (Reference Rindova, Petkova and Kotha2007), we used open coding to break interview and archival data into categories. Our first-order codes were linked to the five areas that inspired interview questions and secondary data collection, we labeled them as: internationalization drivers, internationalization patterns, internationalization obstacles, international capabilities, and reputation decisions. We coded both archival data and first interview round information using these codes. In this initial data coding, we worked with the verbatim and paid detailed attention to the participants’ language; nonetheless, the ideas that were not sufficiently clear for us were clarified directly with the participants in subsequent interview rounds.

At this initial phase, we created a timeline with details, evidence, quotations, and events regarding international expansion and corporate reputation for each of the selected firms independently. Eventually, additional interview rounds and documentary collection assisted us in reaching a level of saturation in which further data collection no longer provided new insights but just confirmed existing findings. This step helped us to better understand the behavior of each firm.

In a second stage, after conducting the additional interview rounds, we refined the initial codes with the repetitive iteration between data and theory (Welch et al., Reference Welch, Piekkari, Plakoyiannaki and Paavilainen-Mäntymäki2011) and conducted a cross-case analysis that allowed us to identify patterns represented in refined categories. Second-order categories included existing and emerging elements that we labeled in three groups as: FSA exploiting and acquiring, internationalization burdens, and international survival mechanisms. Once more, we juxtaposed our second-order categories to the theory searching for conclusions that speak directly to theories on international expansion and corporate reputation in EMFs.

Finally, taking into account the observed categories and considering the recommendation of Miles, Huberman, and Saldana (Reference Miles, Huberman and Saldana2014) to reach bolder insights while highlighting observed patterns, we evaluated several metaphors that capture richness, complexity, and significance of findings. Metaphors have been frequently used in business literature: the ‘Springboard Perspective’ (Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2007); the ‘Goldilocks debate’ (Cuervo-Cazurra, Reference Cuervo-Cazurra2012); ‘Asian Tigers’ (Lall, Reference Lall1996); and ‘Dragon multinationals’ (Mathews, Reference Mathews2006) serve as examples. We decided that ‘Jaguars’ offer the most suitable metaphor for the characteristics of the observed companies and displayed our findings in the form of propositions. The next section provides more detail about the metaphor selection and describes the profiles of studied firms.

RESULTS

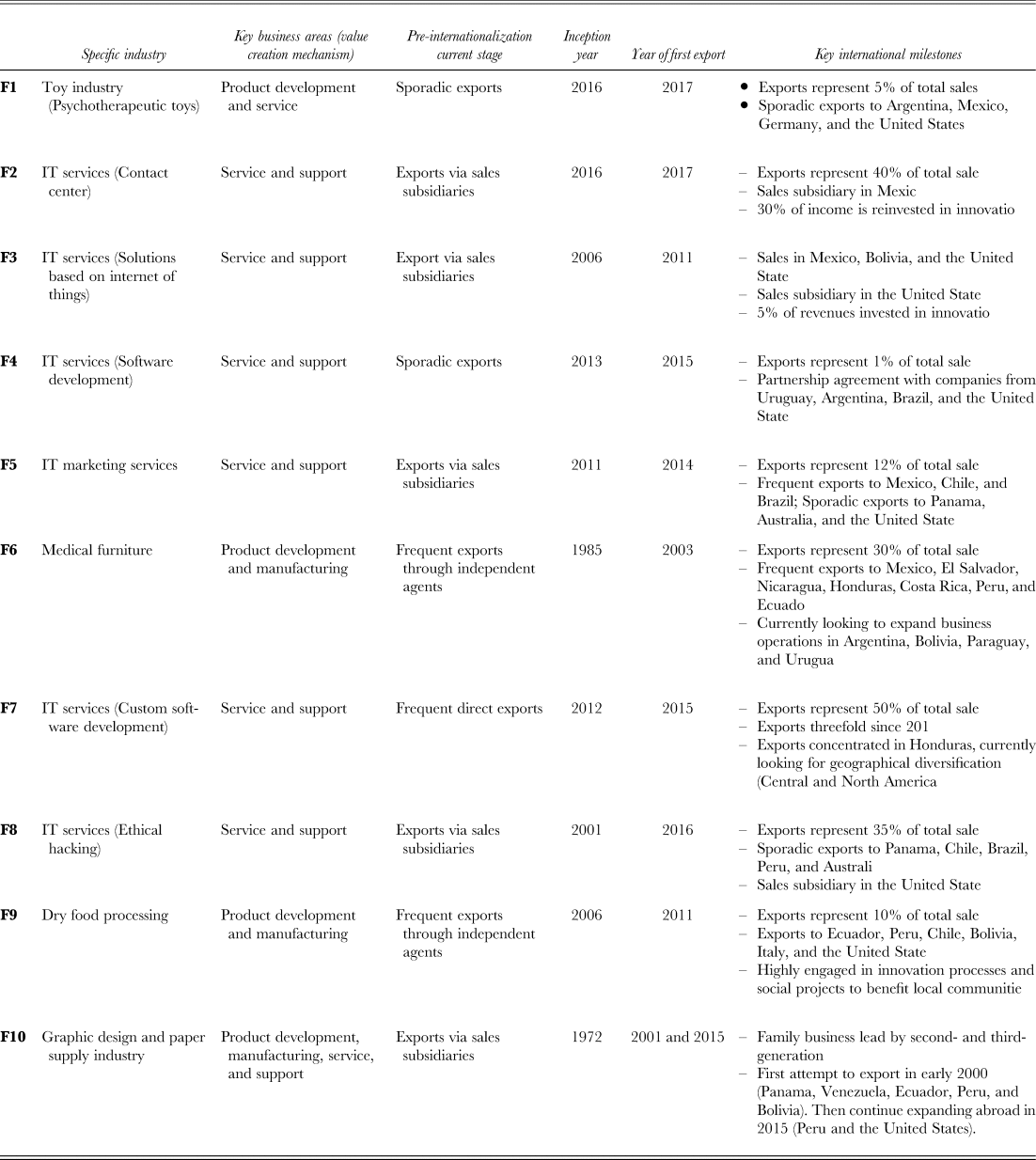

Cases here are presented and jointly analyzed to identify how these companies deal with the special challenges of early internationalization from an emerging market. Table 1 introduces the studied companies and their key characteristics. Similar to previous studies (e.g., Coviello, Reference Coviello2006; Kontinen & Ojala, Reference Kontinen and Ojala2011; Rui et al., Reference Rui, Cuervo-Cazurra and Un2016), the findings are presented at the firm level after conducting interviews with senior executives. Although observed companies are in pre-FDI stages, all of the participants expressed their intention to eventually engage in FDI activities.

Table 1. Firm profiles

FSAs and International Expansion Drivers/Patterns (Jaguar Firms as Tropical Dwellers)

Although the natural habitat of jaguars mostly includes tropical and sub-tropical moist forest close to rivers, they have been occasionally documented in dry Arizona and New Mexico, and even fishing in the Brazilian sea to survive. (Quigley et al., Reference Quigley, Foster, Petracca, Payan and Salom2017)

As observed in Table 1, with respect to the regions and markets in which these companies operate, three of them have business activities solely within the Latin American region (F2, F6, and F7), moreover, three additional companies have operations in Latin America and the United States (F3, F4, and F10). While the remaining companies have operations within Latin America and sporadically in other countries, such as Germany and the United States (F1), Australia and the United States (F5), Australia and the United States (F8), and Italy and the United States (F9), and just one of the observed companies (F9) has constant exports to a country outside its own region (Italy). When questioned about these activities, just as jaguars, all of these firms recall that they have an inclination to remain in the region; however, the unusual activities in other territories are attributable to external, reactive stimuli that allows them to unwittingly upgrade capabilities to better compete in their preferred region (Leonidou, Katsikeas, Palihawadana, & Spyropoulou, Reference Leonidou, Katsikeas, Palihawadana and Spyropoulou2007). For instance, activities of F1 in Germany respond to a college course that the founder took in that country that helped her establish some contacts there, meanwhile a former employee of F8 moved to Australia and referred the company to current employer.

Most of the companies manifested their confidence with current knowledge, capabilities, and intangible assets; when directly asked, founders and senior executives stated that they are pleased with their existing FSAs. Furthermore, they perceive international expansion as a way to exploit existing FSAs rather than to acquire new ones. ‘We have the technical level to compete with anybody in the world’, expressed one of the founders of F8. ‘We are a highly innovative company, and innovation is the only thing that let us compete with any company, regardless of their size’, said the founder and CEO of F9.

The cross-case analysis also resulted in the identification of shared features in the international expansion behavior of these firms. There are some common trends with regard to the drivers for international expansion. For instance, collaborators from F1, F2, F5, F7, F8, and F9 state that they like to feel challenged and that taking their firms to international markets is something that stimulates them in a personal way. Passion motivates them in a personal manner: ‘I feel smart when talking to international clients’ (F1), and ‘I did not want to found a company with purpose, I wanted a purpose for myself’ (F2) illustrate intimate incentives. F1, F6, F9, and F10 mention sales increases as their main driver for international expansion. The remaining cases are primarily motivated to expand abroad from a different yet shared reason. F2, F3, F4, F5, F7, and F8 provide IT services that rely on the availability of talented and skillful engineers; however, due to the recent arrival of international competitors that offer better compensation packages, observed IT companies are struggling to retain current employees and find new talent. ‘We know we do not offer the most competitive salaries in the country, we need to expand overseas, especially to the United States, to offer better compensation to our employees so they stay with us,’ expressed one of the founders of F4; while the CEO of F7 stated, ‘We realized that other companies are paying more than us. Those salaries are absolutely out of our range; we need to find more international clients to catch up and remain competitive’.

Physical proximity, cultural affinity, and the ease of having similar time zones are some of the reasons for remaining in the Latin American region, and occasionally in the United States. A respondent from F3 expressed, ‘I think Latin America is the best market for expanding, especially because of the cultural affinity. Besides, it is more convenient to work within your time zone’, similarly, the founder of F7 mentioned that ‘In 5 years, we want to have presence in North, Central and South America. This is mainly because of the time zones’. All of the participant firms expressed that they are willing to either enter or increase their presence in the United States; however, all of them (excluding F5) asserted that it is more demanding than remaining within Latin America. For instance, an executive from F6 stated that ‘Right now we are in around 10 countries, mostly in Latin America. Even though our goal is to enter the United States, it's easier for us to go into Latin American markets. Not just because of the language, but because we're culturally closer’, and an executive from F3 expressed that ‘contacting and keeping an American client requires much more effort us’.

Some findings on drivers of international expansion are somehow related to those in previous studies (Francioni, Pagano, & Castellani, Reference Francioni, Pagano and Castellani2016; Leonidou et al., Reference Leonidou, Katsikeas, Palihawadana and Spyropoulou2007). For example, we identified firms that are driven by the desire of their founders to exploit current FSAs and managerial skills in an international setting (F1, F2, F5, F7, F8, and F9); international expansion drivers of these firms are more consistent with existing IB literature that points out the internal, proactive, resource-oriented stimuli (Leonidou et al., Reference Leonidou, Katsikeas, Palihawadana and Spyropoulou2007). Additionally, drivers of F1, F6, F9, and F10 are consistent with the network and subjective, socio-demographic characteristics of founders that boost international presence (Francioni et al., Reference Francioni, Pagano and Castellani2016).

We also identified that some of these firms have international expansion drivers that, to the best of our knowledge, have not been extensively studied before in the context of Latin America. For instance, F3, F5, F7, F9, and F10 exhibit an ambidextrous behavior based on their geographical presence. These companies exploit their FSAs in neighbor markets where they operate and simultaneously explore further and often more developed markets in an attempt to acquire and upgrade FSAs. Besides, we identified that the international expansion of F2, F3, F4, F5, and F7, which all belong to the IT sector, is driven by their need to access international clients in developed economies. As these commercial transactions are usually more profitable than the ones carried out within Latin America, these firms use the additional profits to better compensate home country employees as a mechanism to protect from local war for talent and brain drain. We summarize these ideas with the following propositions:

Proposition 1a: Jaguar firms tend to simultaneously exploit their strong technical expertise and current FSAs within their own region (native environment) and occasionally enter advanced markets to acquire and upgrade FSAs.

Proposition 1b: Jaguar firms benefit from the international expansion to advanced markets (beyond their native environment) by using it as a survival mechanism that allows them to offer better compensation to their home country employees to retain their knowledge and compete with foreign firms at home.

The self-confident assessment of their capabilities and intangible assets could be explained by either their limited international exposure or the capabilities and FSAs that they have actually developed as specialized service or product providers. Anyhow, our findings represented in proposition 1a seem to disagree with the idea that EMFs internationalize to catch up FSAs (Hennart, Reference Hennart2012; Li & Oh, Reference Li and Oh2016). Instead, these companies are specialized service and product providers and reported having sufficient FSAs to compete regionally; nevertheless, Jaguar firms exhibit a more cautious behavior when conducting businesses beyond Latin America. Additionally, entering advanced markets is a reactive mechanism to get more financial resources to offer better salaries to local employees and avoid brain drain.

Obstacles in International Expansion (Jaguar Firms as Masters of Camouflage)

The rosettes on jaguars’ fur act as camouflage that help them hunt with their distinctive stalk and ambush behavior. (Seymour, Reference Seymour1989)

All analyzed cases asserted they have experienced different forms of LOF (Zaheer, Reference Zaheer1995). F1 and F9 mentioned that they have difficulties finding both international clients and partners; while F2, F3, F4, and F8 mentioned that the language barrier was a relevant issue that limits their international expansion. For example, ‘language is our main barrier to find clients in the US market’, argued one of the founders of F5. Meanwhile F8, F9, and F10 affirmed that cultural distance was larger and more problematic than they first expected; ‘We provide marketing services, our limited knowledge, and understanding of international clients restrict us’, claimed the founder of F5. Observed cases that produce tangible outcomes (non-services) also recalled their difficulties in terms of international distribution and logistics prices (F1 and F10) and non-tariff barriers, especially certifications (F6 and F9). Opposite to what is expected, these companies did not openly report additional barriers associated to LOE (Madhok & Keyhani, Reference Madhok and Keyhani2012). However, some of them refer to specific situations where they hide or conceal either their country of origin or lack of experience in international markets.

For instance, F3 and F4 remarked that their country of origin acts as a burden when expanding internationally so that they decide to disguise it. ‘We usually do not mention our country of origin. Some of our potential international clients doubt that this technology is made here’, argued one of the founders of F3. ‘Our experience with local companies is not valued by potential international clients’, mentioned the CEO of F4. The remaining cases exhibit heterogeneous pieces of evidence. For instance, the founder of F5 expressed that their lack of mutual understanding of cultural differences with international clients acts as a barrier to expanding. In addition, he mentioned that some potential international clients have demonstrated surprise when realizing the company origin ‘IT services, from Colombia, really?’ (F5). The marketing leader of F6 mentioned that their country of origin influences differently depending on the country: ‘We have had mixed experiences regarding international reputation, in Argentina they did not seem interested in our products, while in Bolivia they were very welcoming and eager to accept us’ (F6), which is consistent with previous research on consumer animosity (Fong, Lee, & Du, Reference Fong, Lee and Du2013) and the role of country reputation on exports (Dimitrova, Korschun, & Yotov, Reference Dimitrova, Korschun and Yotov2017).

F8 and F9 have experienced both difficulties and advantages linked to their origin. As F8 offers hacking services, they mention their country of origin as a way to validate their experience: ‘We are a security company that comes from a challenging market, we know many ways to be a criminal’ (F8). However, they also acknowledge that their lack of knowledge and international contacts have limited their expansion. ‘Sometimes people do not trust us because of our origin’, stated one of the founders of F8; meanwhile a senior executive of the same company expressed that ‘Being a Latin company in the USA affects trust-building with our clients, that is why we decided to create a company here [in the USA]’. When directly asked, F1 and F10 reported that they have not experienced any difficulty associated with their origin. In fact, collaborators from F10 mentioned that their country of origin constitutes an advantage when looking for international clients, especially because it is associated with good quality services/products. However, the same companies also reported that they have had difficulties associated with international logistics costs (F1 and F10) and to availability of local skillful talent (F2). F2's founder mentioned that ‘being from this country is internationally unfavorable in terms of the negative political and competitive image’.

F9 dehydrates food and beverages and reduces them to powder, so they have experienced some uncomfortable situations with potential international clients that refer to drug dealing. ‘We have to work harder because we are from Colombia. Selling powders from this country is still a taboo’, mentioned an executive from this firm, who also told us that ‘our products (usually in the form of white powders) are frequently scrutinize in foreign customs, many times it has been destroyed. We are negatively labeled for being from this country’. While F8, F9, and F10 set up sales subsidiaries motivated by covering up their foreign origin and facilitating business in the United States (F8 and F9) and Peru (F10).

We also identified that 7 out of 10 firms (F1, F2, F3, F4, F7, F8, and F10) have names in the English language. The other firms have names that are not associated with a particular language (F5 and F6) or a Spanish acronym (F9). Two companies recently changed their names and image (F6 and F8). An executive of F6 told us that ‘We recently changed our name and brand image to make it more appealing for international clients; our new name is easier to pronounce in different languages’, and one of the founders of F8 stated that ‘Earlier this year we changed the name of the company and created a new sales subsidiary in the USA. We changed our image, our brand and our name to make it more international oriented…our former name was also in English, but it was not related to what we do, the new one is more specific’. These actions could be interpreted as companies’ efforts to disassociate their names and image from a particular country of origin.

F5, F8, F9, and F10 have experienced some difficulties with expatriates and have hired locals to reduce the liability of foreignness. For instance, the founder of F5 expressed, ‘As we do not know the American market, we found a guy in Washington who was a consultant; he did not have a production infrastructure, so he contacts clients and we provide the service. We actually had some clients here in Colombia through him’. Similarly, a senior executive of F8 told us that a language barrier was one of the biggest difficulties when operating in the United States and claimed that ‘We hire some retired Americans that know the industry and want to stay active, they are good sale channels for us because they have all the networking and knowledge we lack’.

F9 and F10 decided to open up sales subsidiaries in the United States and Peru, respectively. There, they hire locals. For example: ‘We are setting up a subsidiary in Florida, USA, American companies prefer to do business with local companies’ (F9), and the founder of F10 argued that they ‘Initially thought that the cultural distance with Peru was shorter, then we realized that the only thing we have in common is the language. So, we decided to hire a local as a sales representative’. These actions imply the acceptance of the negative effects of LOF and a clear mechanism by which observed firms hide or disguise their foreignness and newness when operating abroad. This evidence led us to the following proposition:

Proposition 2: When operating outside their own country, Jaguar firms camouflage their newness and disguise their lack of international experience to reduce the liability of foreignness.

Jaguar firms are reluctant to directly acknowledge disadvantages linked to their country of origin. However, when asked indirectly, they reported hiding their foreignness and newness by adopting English company names, hiring host-country talent, and setting-up sales subsidiaries.

International Solitary Endeavor (Jaguar Firms as Solitary Predators)

Jaguars are mostly solitary; they generally avoid one another although their territories may overlap. Adults meet when in need, primarily to court and mate. (Quigley et al., Reference Quigley, Foster, Petracca, Payan and Salom2017; Seymour, Reference Seymour1989)

None of the observed cases decided to use any form of strategic alliance and/or joint venture to internationalize. Just two firms use an international partnership to leverage local and international business, F5 and F10. Initially, both companies fortuitously started their contact with such international partners, and eventually, the relationship became more solid and relevant for the success of the companies. The founder and CEO of F5 mentioned that their partnership with a global marketing platform was the result of the requirement of an American company: ‘This company told us: “I want to work with you, but you need to be certified”… then this partnership was like a miracle for us, that let us become experts in inbound marketing and reach many more clients’. Meanwhile, F10 has an agreement with an Italian provider of luxury graphic specialties. ‘We started the relationship as buyers, then we became their exclusive distributors. This relationship helped us to position as a competitive company that cares about quality and sustainability’, told us the CEO of F10.

All the observed firms received professional advisory from governmental agencies to expand overseas. However, they are reluctant to further commit and establish alliances and partnerships. ‘We used to be part of different business organizations and business clusters, but they are not as useful, we prefer to work just with our clients’, expressed an executive of F6. Nevertheless, these companies take advantage of opportunities that arise because of their relationship with other companies. For instance, F1 and F2 are constantly looking for free press opportunities. The founder of case 1 expressed, ‘I take advantage of the media exposure of my company; we have calculated the percentage of sales increment after every media appearance’; likewise, the founder of company 2 mentioned, ‘I take advantage of free press, people come to us and say, “I saw your company in a magazine and I love it, I want to do business with you”’.

Instead of establishing formal alliances, these companies actively benefit from external and even serendipitous actions. The founder of F2 stated that the establishment of a sales subsidiary in Mexico responded to several factors; ‘the market is highly competitive, it has a large population, it is close to the USA, I have family ties there… and because of the political problems, many Mexicans that lived in the USA are going back to their country, so they are familiar with the American culture and speak fluid English’. A senior executive of F8 mentioned that ‘as a former employee moved to Australia, he referred us to his new company, and we made a project there’. Meanwhile, the founder and CEO of F9 affirmed that the peace process in Colombia is beneficial for his company because ‘it represents an opportunity to invest and develop local suppliers in order to add value to the local agribusiness industry and better compete internationally’.

The studied companies also display an aggression avoidance conduct that has triggered their international expansion. Seven companies (F2, F3, F4, F5, F6, F7, and F8) acknowledge that avoidance of local competitors influences their international expansion. Furthermore, several firms (F1, F4, F7, F8, F9, and F10) mentioned that the conditions of their home country and the presence of strong competitors somehow make their operations more difficult. ‘My city is the most difficult scenario for a company like this, but it has been great training for our international expansion. People's mindset is our main barrier for expansion locally, that is why we want to expand internationally’, mentioned the founder of F1. The founder and CEO of F5 told us that ‘agencies as our pop up very often here, it is like a commodity, there are no barriers, so we need to find more international clients to compete… as our industry has become so competitive, companies are adding more and more value’.

As the competition and the business environment is a problem for some of these companies, for instance, the founder of F9 expressed that ‘One of our main problems is the local business ecosystem’; so international expansion is perceived as an exit to this problem. ‘International process is an obligation for us. Especially for two reasons: first, the local market is limited, and second, international companies are coming here to look for talent. We cannot capture the value of that workforce without being recognized abroad. We must go abroad to be able to pay good salaries and compete for new talent’ (F8). The evidence above led us to these propositions:

Proposition 3a: When expanding beyond their native region, Jaguar firms most likely perform a solitary behavior and occasionally enter strategic alliances to gain legitimacy and enhance reputation.

Proposition 3b: Jaguar firms avoid direct confrontation with strong international competitors at the home market by expanding internationally.

EMFs are likely to rely on networks (Ciravegna et al., Reference Ciravegna, Lopez and Kundu2014) and interfirm collaborations (Gould, Liu, & Yu, Reference Gould, Liu and Yu2016) when they are starting their international expansion. However, as presented in proposition 3a, Jaguar firms favor individual attempts when initiating their expansion, unless the international partner helps them build credibility and legitimacy.

DISCUSSION

This article analyzes the mechanisms that ten EMFs in pre-FDI stages use to deal with challenges associated with their country of origin and lack of international experience. As presented in Figure 1 and in the propositions, we identified some common features observed in firms that are consistent with the existing literature. For instance, the firms’ preference to remain in their own region (Gonzalez-Perez & Velez-Ocampo, Reference Gonzalez-Perez and Velez-Ocampo2014; Hennart et al., Reference Hennart, Sheng and Carrera2017) and their escape driver to international due to the unfavorable conditions of home country (Cuervo-Cazurra et al., Reference Cuervo-Cazurra, Narula and Un2015; Cuervo-Cazurra, Reference Cuervo-Cazurra2016; Witt & Lewin, Reference Witt and Lewin2007). However, our findings also report some novelties in terms of drivers and obstacles to expand. In particular, proposition 1a presents a dual mechanism by which Jaguar firms exploit their current FSAs within the Latin American region and occasionally enter advanced markets to upgrade and catch-up FSAs. To the best of our knowledge, this simultaneous mechanism has not been previously documented.

Proposition 1b highlights an international expansion driver where further clients are pursued not under a market-seeking, sales increasing rationality (Cuervo-Cazurra et al., Reference Cuervo-Cazurra, Narula and Un2015; Dunning et al., Reference Dunning, Kim and Park2008), but for knowledge and employee retention in the home country. This specific internationalization driver primarily oriented to get new international clients to eventually improve the compensation of employees and retain them was not specifically observed and/or discussed in previous studies of Latin American firms (Ciravegna et al., Reference Ciravegna, Lopez and Kundu2014; Cuervo-Cazurra et al., Reference Cuervo-Cazurra, Narula and Un2015; Gonzalez-Perez et al., Reference Gonzalez-Perez, Velez-Ocampo and Herrera-Cano2018; Paul, Parthasarathy, & Gupta, Reference Paul, Parthasarathy and Gupta2017).

Proposition 2 presents a disguising mechanism that Jaguar firms use to hide their origin and newness in international markets. We identified that observed companies modified their names to ones in English that might sound more familiar to foreign clients and dissimulate the companies’ origin. Besides, we also found that hiring locals in foreign markets and establishing sales subsidiaries are actions intended to cover Jaguar firms’ foreignness.

Even though EMFs in pre-FDI stages are expected to more likely rely on networks and interfirm collaborations (Ciravegna et al., Reference Ciravegna, Lopez and Kundu2014; Gould et al., Reference Gould, Liu and Yu2016), as presented in proposition 3a, we found that Jaguar firms are more willing to remain solitary at the initial stages of international expansion. However, they might consider engaging in strategic alliances only when the potential partner helps them build legitimacy and reputation. Proposition 3b points out that, as expected, Jaguar firms also exhibit an escapist behavior (Witt & Lewin, Reference Witt and Lewin2007); however, in this case, this driver is linked to the avoidance of strong international competitors at home rather than to institutional voids and constraints that characterize emerging economies (Madhok & Keyhani, Reference Madhok and Keyhani2012; Ribeiro et al., Reference Ribeiro, Lahiri and Mendes2015).

Figure 1 summarizes existing literature and the distinctive characteristics of what we call Jaguar firms, while the results section introduces evidence of such observations. These firms share a set of features that resemble the behavior of this American wild cat that prefers tropical and subtropical forests as a habitat. Observed cases, just as jaguars, exhibit some common characteristics. For example, they prefer to remain in their own region, are highly symbolic and vividly protected, control and depend on other species although present a solitary behavior, and although they avoid direct confrontation, roar when needing to warn territory and keep competitors away. This article thus provides empirical evidence of Jaguar firms and their preference to remain in their own region, strategies to disguise their origin and/or lack of international experience, solitary behavior, and aggression avoidance conduct.

Regarding another theoretical contribution of this study, here is an ongoing discussion on whether or not EMFs own conventional FSAs (like technological know-how, managerial abilities, strong brands, patents, innovation, marketing prowess) and internationalize to exploit or to acquire them (Buckley, Reference Buckley2018; Hennart, Reference Hennart2012; Li & Oh, Reference Li and Oh2016). The assumption that international expansion is motivated by the exploitation of FSAs is at the core of the theory (Verbeke & Kano, Reference Verbeke and Kano2016), so firms that possess FSAs internationalize to exploit them internally. However, alternative explanations of the internationalization of EMFs (e.g., Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2007; Mathews, Reference Mathews2006) assume that these firms do not necessarily possess FSAs and argues that EMFs expand abroad to acquire new FSAs rather than to exploit pre-existing ones. This is why, based on the results of this study, we believe that when firms exhibit characteristics similar to those of Jaguars firms, it is important that they won't be treated as a herd with endowments of the developing country national original. It is critical that policymakers consider that these companies should be supported in strengthening their technical and managerial capabilities and avoid giving them a treatment that homogenizes or makes their nationality visible since this could unnecessarily increase the liabilities of these companies when operating abroad.

As a recommendation to managers of Jaguar firms, we consider that these companies must challenge their FSA with international ventures, not necessarily with the purpose of expanding outside their native environment, but to strengthen precisely their FSA, and to know potential competitors outside their region.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Regarding the limitations of this study, the following can be highlighted. The findings of our research may have been influenced by the design and chosen methodology and data collection restrictions. For this study, a purposive sample of cases was used. In other words, the companies included in the study are part of a non-probabilistic sample and were selected based on the characteristics we wanted to study. It is for this reason that we consider that this may be a limitation to extrapolate our generalizations of the study to the entire population of EMFs. For this, it would be ideal to replicate this study in a different developing country with a different set of institutional characteristics. Furthermore, as we only interviewed participants from the firms’ country of origin and did not have access to foreign stakeholders of these companies, our findings reflect self-reported strategies and rationale of observed firms rather than the perceptions of foreign stakeholders towards the legitimacy and reputation strategies and outcomes of these companies. For this, it would be ideal to replicate this study in different developing countries and consider the perceptions of multiple stakeholders at home and host locations.

Interviews were conducted in English, which is not the first language of the participants. The fact that the interviews were conducted in English, and the native language of the interviewees is Spanish, does not only mean that naturalness and fluency in the answers were lost, but the accuracy of the answers might be limited. In addition, it complicated the transcription process of the interviews due to the limitations of the use of language.

From a methodological standpoint, case studies such as this that are intended to generate analytical generalization to the theory and might lack statistical generalization to the population (Gibbert & Ruigrok, Reference Gibbert and Ruigrok2010; Yin, Reference Yin2014). Theories and theoretical classification as the one proposed in this article using the metaphor of jaguars are simplifications and representations of empirical phenomena (Bacharach, Reference Bacharach1989). In addition, they are not intended to provide explanations beyond their boundaries. The international behavior of EMFs has a level of complexity and heterogeneity that prevents its reduction to a single framework. In other words, the Jaguar firm classification is not intended to capture the behavior of every EMF but to provide theoretical insights that allow us to better discuss and comprehend the rationale behind some of their decisions related to foreign expansion.

We use archival data and interviews with participants representing different status levels in the observed organizations in three rounds of interviews covering a 22-month period. As recognized elsewhere (e.g., Aguinis & Solarino, Reference Aguinis and Solarino2019; Basu & Palazzo, Reference Basu and Palazzo2008), interview data is useful for exploring and analyzing micro-foundations of strategic decisions as interpreted by participants in their own sensemaking process. However, there are some inherent limitations of interviewing like ambiguity of the language and potential lack of trust, which are not as influential in other data collection techniques (Myers & Newman, Reference Myers and Newman2007). There are a number of areas where future research could be helpful. Future studies could benefit from testing our propositions in additional emerging markets to evaluate to what extent the mechanisms identified here are generalizable to other locations. Researchers can also re-examine the dual FSA exploration and exploitation drivers in emerging and advanced markets, the camouflaging actions, and the preference of additional firms to tackle international expansion without engaging in strategic parentships. From a theoretical standpoint, future research could further explore how learning and capability upgrading interact with the international expansion of EMFs.