INTRODUCTION

Organizational learning creates advantages for firms by enhancing their capability to respond to environmental changes (Levinthal & March, Reference Levinthal and March1993). Firms learn from others ‘through the transfer of encoded experience in the form of technologies, codes, procedures, or similar routines’ (Levitt & March, Reference Levitt and March1988: 329). A classical ecology of organizational learning envisages a collection of firms that coexist and interact with each other in a space of community, which is defined as a ‘territory’ serving members’ economic and noneconomic needs (Thornton, Ocasio, & Lounsbury, Reference Thornton, Ocasio and Lounsbury2012). Interorganizational learning occurs as a result of such interactions by leading to the isomorphic diffusion of social norms among organizations in the community. According to this view, a firm's learning behaviors are not only determined by economic considerations but also facilitated or constrained by prevailing institutional forces that operate in the community (Levitt & March, Reference Levitt and March1988; March & Olsen, Reference March and Olsen1983).

Although social norms offer a useful lens through which we can understand how firms learn within a community, knowledge about why firms in different communities differ in the effectiveness of learning is still limited. To address this lack of understanding, we draw on the institutional logic perspective to uncover how institutional complexity unfolds in a community and influences firms’ organizational learning. Institutional logic is a socially constructed set of values, norms, and beliefs that guide the behaviors of organizations (Thornton et al., Reference Thornton, Ocasio and Lounsbury2012). When multiple logics coexist within a community, firms are faced with institutional complexity, defined as the degree of incompatibility between the institutional prescriptions of different groups of actors (Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta, & Lounsbury, Reference Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta and Lounsbury2011). Research shows that the existence of multiple institutional constituencies in the same community is a common phenomenon in many industries (Krug & Hendrischke, Reference Krug and Hendrischke2008), such as banking (Marquis & Lounsbury, Reference Marquis and Lounsbury2007), health care (Dunn & Jones, Reference Dunn and Jones2010), and moral markets (Yue, Wang, & Yang, Reference Yue, Wang and Yang2019).

Recent studies have begun to explore how competing-complementary logics influence organizational behaviors and outcomes (e.g., Smets, Jarzabkowski, Burke, & Spee, Reference Smets, Jarzabkowski, Burke and Spee2015; Yan, Ferraro, & Almandoz, Reference Yan, Ferraro and Almandoz2019). However, prior research is still largely silent on how institutional complexity in a community affects interfirm learning within the community. To address this gap, we study the organizational learning of firms in clusters, focusing on how they learn from each other under institutional complexity. Clusters, defined as geographically proximate groups of interconnected firms and the associated organizations that are linked by commonalities and complementarities, are viewed as communities in this research (Porter, Reference Porter2000; Zhang, Li, & Schoonhoven, Reference Zhang, Li and Schoonhoven2009). Institutional theory suggests that community logic, defined as the norms, beliefs, and values that are socially constructed by actors in a community (Marquis, Glynn, & Davis, Reference Marquis, Glynn and Davis2007), emerges from geographic proximity and dense networks that exist among community members and, as a dominant institutional order, has a profound effect on the cognitive and behavioral frameworks of social actors (Almandoz, Reference Almandoz2012; Thornton et al., Reference Thornton, Ocasio and Lounsbury2012). In the cluster literature (e.g., Arikan, Reference Arikan2009), the agglomeration of firms creates a common sense of the ‘rules of the game’ that guides knowledge flows among collocated firms (Tallman, Jenkins, Henry, & Pinch, Reference Tallman, Jenkins, Henry and Pinch2004: 265). Thus, community logic influences firms’ localized learning in clusters. Meanwhile, clusters also vary in the degree to which an authoritative actor, such as a local government, exercises control over the ways through which member firms interact with each other in the cluster (Arikan & Schilling, Reference Arikan and Schilling2011). Hence, a government logic, defined as the rules that are established by government agencies to structure the social actions in their jurisdictions (Friedland & Alford, Reference Friedland, Alford, Powell and DiMaggio1991), also influences interfirm learning within a cluster.

In this study, we posit that conceptualizations of institutional complexity go beyond the role of social norms and offer a holistic theoretical framework for untangling the causalities underlying organizational learning in a community. Specifically, we suggest that the involvement of local government in a cluster featuring strong community logic leads to the coexistence of government logic and community logic in the cluster. The resulting institutional complexity and inconsistencies between the two logics may confuse firms and influence their localized learning in the cluster. Furthermore, building on the view that multiple logics are either conflicting (e.g., Almandoz, Reference Almandoz2014) or complementary (e.g., Jay, Reference Jay2012), we theorize that the relationship between the community and government logics in a cluster can be competing or harmonious and thus hinder or facilitate firms’ learning, depending on the degree of the social connections among collocated firms and the local governmental agencies.

We make two contributions. First, our study extends March's seminal work (Levitt & March, Reference Levitt and March1988), which champions the isomorphic diffusion of social norms as a core mechanism of learning in a community. Although prior research recognizes the role of government as an institutional force in guiding firms’ learning and promoting regional economic development (Barbieri, Tommaso, & Bonnini, Reference Barbieri, Di Tommaso and Bonnini2012), little is known about how government logic works with community logic to affect firms’ learning behaviors. In this study, we suggest that multiple institutional logics (community logic and government logic) impose conflicting guidance on firms’ learning and engender a competing effect on the effectiveness of their learning. Our conceptualization advances March's insight into organizational learning (Levitt & March, Reference Levitt and March1988) by developing the premise that the role of the isomorphic diffusion of social norms in community-based organizational learning is negatively moderated by another key institutional force, government logic.

Second, we contribute to the understanding of how the compatibility and incompatibility of multiple institutional logics that exist in a community influence firm behaviors and outcomes. Prior research has conceptualized either a competing (e.g., Liu, Zhang, & Jing, Reference Liu, Zhang and Jing2016) or a harmonious (e.g., McPherson & Sauder, Reference McPherson and Sauder2013) relationship between multiple logics. We move beyond these competing theoretical predictions and, instead, focus on when the competing or harmonious relationships prevail. Specifically, we theorize whether and how the negative moderating effect of government logic on the relationship between community logic and organizational learning changes depending on the social connections between the firms in the community and local governments. In this way, our study offers new insights into the conversations regarding the compatibility and incompatibility of multiple institutional logics and their effects on organizational outcomes (Besharov & Smith, Reference Besharov and Smith2014).

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Organizational Learning in Regional Clusters

Organizational learning is a key mechanism through which a firm achieves strategic renewal. While factors such as interorganizational networks (e.g., Powell, Koput, & Smith-Doerr, Reference Powell, Koput and Smith-Doerr1996), knowledge overlap (e.g., Ahuja & Katila, Reference Ahuja and Katila2001), and the balance of competition and collaboration in R&D consortia (e.g., Chen, Dai, & Li, Reference Chen, Dai and Li2019) influence the effectiveness of learning, regional clusters are also recognized as a critical social milieu in which firms advance organizational learning via local embeddedness (Tallman et al., Reference Tallman, Jenkins, Henry and Pinch2004). In this vein, scholars have explored the issue of how new knowledge can be created from the interdependencies between collocated firms (Arikan, Reference Arikan2009). According to this knowledge-based view, clusters help enhance the effectiveness of knowledge searching and acquisition through the interactions between firms within the cluster and therefore act as an important vehicle for firms’ organizational learning.

The literature also recognizes that institutional forces in a cluster influence the effectiveness of organizational learning. Pouder and St. John (Reference Pouder and St. John1996) conceptualized the isomorphism of firm innovation as being caused by overimitation among firms in clusters. They emphasized that institutional pressures associated with the acceptance of social norms in the community influence firms’ learning. In addition, research has highlighted the role of other institutions, such as governments, in cluster-based learning (Jia, Li, Tallman, & Zheng, Reference Jia, Li, Tallman and Zheng2017; Wei, Lu, & Chen, Reference Wei, Lu and Chen2009). In particular, coercive pressure from the government may facilitate or constrain firms’ localized learning.

Three key conclusions have emerged from prior research. First, organizational learning requires a firm's willingness to search for external knowledge to renew its existing knowledge portfolios. A regional cluster, viewed as a community, acts as a learning vehicle that motivates firms’ local searching (McCann & Folta, Reference McCann and Folta2008). Second, organizational learning does not occur automatically; firms must be able to acquire and integrate external knowledge into its routines. In this regard, a cluster, through its commonly accepted practices that are embodied in geographically based interfirm interactions, enhances a firm's ability to acquire knowledge from collocated firms and assimilate it (Lawson & Lorenz, Reference Lawson and Lorenz1999). Third, learning among collocated firms is influenced by a complex set of institutional forces. Different institutional constituencies define whom others should learn from and how learning takes place in a cluster, through a bottom-up or top-down fashion (Arikan & Schilling, Reference Arikan and Schilling2011). In the next section, we introduce the concept of institutional complexity and discuss its role in organizational learning.

Institutional Complexity and Cluster-Based Learning

Linking institutions with organizational learning, March and Olsen (Reference March and Olsen1976) suggested that institutions provide organizations with conventions for determining which problems should be paid attention to and which solutions should be considered. Relying on the notions of legitimacy and isomorphism, the early institutional view emphasized the stability that certain institutions may bring to organizations (DiMaggio & Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983).

The institutional logic perspective (Friedland & Alford, Reference Friedland, Alford, Powell and DiMaggio1991) posits that different institutional logics may coexist in the same social system, creating institutional complexity that influences organizational behavior in an intricate manner (Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta and Lounsbury2011). Two opposing views dominate the scholarly debates. One suggests that multiple logics lead to the fragmentation of institutional fields, creating contradictions and tensions (York, Vedula, & Lenox, Reference York, Vedula and Lenox2018). This, in turn, may confuse organizations and threaten their performance (Lee & Lounsbury, Reference Lee and Lounsbury2015). For example, Marquis and Lounsbury (Reference Marquis and Lounsbury2007) found that local bankers in the US faced conflicting demands that threatened their autonomy when a national logic invaded the local domain. By contrast, the other emphasizes the possible harmonious coexistence of multiple logics (Smets et al., Reference Smets, Jarzabkowski, Burke and Spee2015) or suggests that blending multiple logics facilitates ‘healthy debating’ between different logics, making organizations more innovative (Jay, Reference Jay2012). The two opposing views have led scholars to call for studies to investigate the two facets of institutional logic – compatibility and incompatibility between different logics – when examining the effects of institutional complexity (Besharov & Smith, Reference Besharov and Smith2014).

Despite prior advances, research has provided limited insights into how the coexistence of multiple logics influences organizational behaviors and outcomes (Besharov & Smith, Reference Besharov and Smith2014). Using clusters as an example shows that we still have limited knowledge of why logic multiplicity sometimes inhibits firms’ learning in some clusters but promotes it in others. We suggest that this learning effect varies depending on how local governments are involved in running communities. In this regard, although evidence shows that local governments in the Yangtze River Delta region of China often engage with local business communities (Jia et al., Reference Jia, Li, Tallman and Zheng2017), how they interact with local communities to jointly influence firms’ learning through technological collaborations across different areas, such as Nantong and Changzhou, remains unclear (Nee & Opper, Reference Nee and Opper2012). To this end, we study the role of institutional complexity in organizational learning by using Chinese township clusters, also known as specialized towns (zhuan ye zhen), as our research setting. In the next section, we review this context by engaging and validating the two key concepts in our study – community logic and government logic.

Community and Government Logics in Clusters

March (Reference March2005) suggested that the Chinese context is characterized by a unique set of institutional arrangements. This view holds true for industrial clusters in China. As an industrial cluster, a Chinese town differs from its counterparts in Western countries due to ‘its concentration of firms in the same industry’ (Nee & Opper, Reference Nee and Opper2012: 133). Accordingly, a Chinese township cluster has both geographical and administrative boundaries. This context is particularly interesting because the cluster is situated at the crossroads of community logic and government logic (Jia et al., Reference Jia, Li, Tallman and Zheng2017). On the one hand, township clusters arose as a result of the industrial evolution of Chinese society. Historically, merchants in traditional sectors, such as textiles and handicrafts, established geographically bounded communities in rural areas and created their own rules of doing business in the community (Hua, Chen, & Prashantham, Reference Hua, Chen and Prashantham2016). As time passed, this kind of social convention spreads to other modern industries (such as electronics) and has started to play a dominant role in coordinating the social behaviors of firms in clusters (Hua et al., Reference Hua, Chen and Prashantham2016). As Nee and Opper (Reference Nee and Opper2012) posited, the community-based way of coordinating shaped ‘capitalism from below’ in China. For example, the township cluster of Danyang in Jiangsu province – a glasses manufacturing cluster – was formed in the late 1970s. At that time, a well-functioned local chamber had already existed for more than 10 years before the government established public service centers in the town. On the other hand, China's administrative delegation of a power program (Wei, Zhou, Greeven, & Qu, Reference Wei, Zhou, Greeven and Qu2016) allowed local governments to play an increasingly important role in local economic development by supporting business at the township level (Nee & Opper, Reference Nee and Opper2012). These two observations imply that the behaviors of firms in a typical Chinese township cluster are governed by both community logic and interventional government logic (Jia et al., Reference Jia, Li, Tallman and Zheng2017).

Community logic exhibits two key features. First, it is defined by strong ties among geographically bounded members (Lee & Lounsbury, Reference Lee and Lounsbury2015). For example, Almandoz (Reference Almandoz2012) found that in the US banking industry, dense ties between banks support the development of community logic, which facilitates the acquisition of local resources for the creation of new banks. In contrast, local bankers resist national banks because these banks carry national logic and may not make decisions that are harmonious with those of their local counterparts (Marquis & Lounsbury, Reference Marquis and Lounsbury2007). Second, community logic emerges from local historical evolution, in which process members in the community coestablished a strong norm of committing to mutually beneficial cooperative behaviors (Almandoz, Reference Almandoz2014) rather than a convention that motivates the maximization of self-interest (Smets et al., Reference Smets, Jarzabkowski, Burke and Spee2015). In doing so, community logic provides explicit or implicit guidelines for actors’ behaviors by assessing whether they are engaging normatively right behavior (York et al., Reference York, Vedula and Lenox2018).

A typical Chinese township cluster often has a town-level commercial chamber to coordinate knowledge sharing and transfer among its members (Wei et al., Reference Wei, Zhou, Greeven and Qu2016). Through the process of socialization among entrepreneurs, a community logic ‘glues’ community members together and, more importantly, serves as a key legitimate reference for their behavior. Supporting this view, Nee and Opper (Reference Nee and Opper2012) suggested that local networks in China serve as conduits for obtaining and sharing market information and technological know-how. Honoring the community logic, firms in the community not only exhibit a high degree of altruism but also face high reputational sanctions for noncompliance (Nee & Opper, Reference Nee and Opper2012), ensuring that knowledge sharing and learning between firms is mutually beneficial.

Although a social sector is often structured by the dominant logic, other logics also operate in the sector and influence firms’ behaviors (Yan et al., Reference Yan, Ferraro and Almandoz2019). The extant literature on institutional complexity constantly emphasizes the impacts of institutions, such as government, on organizational outcomes (e.g., Lee & Lounsbury, Reference Lee and Lounsbury2015). In line with this view, government logic also operates in Chinese township clusters. Government logic has two key features. First, it is designed to meet the interests of certain political groups. For example, Yan et al. (Reference Yan, Ferraro and Almandoz2019) suggested that state logic engenders an interventional effect by influencing the financial logic associated with the profit-maximization of investment to uphold the value of societal sustainability. For this reason, government logic is not always aligned with other logics that exist in the community. Second, agencies carrying strong government logic tend to coordinate actors’ behaviors through a command-and-control framework (Lee & Lounsbury, Reference Lee and Lounsbury2015; Thornton et al., Reference Thornton, Ocasio and Lounsbury2012). For example, relying on state authority, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the US substantialized the government logic through its regulatory efforts into the domain of environmental governance (Lee & Lounsbury, Reference Lee and Lounsbury2015).

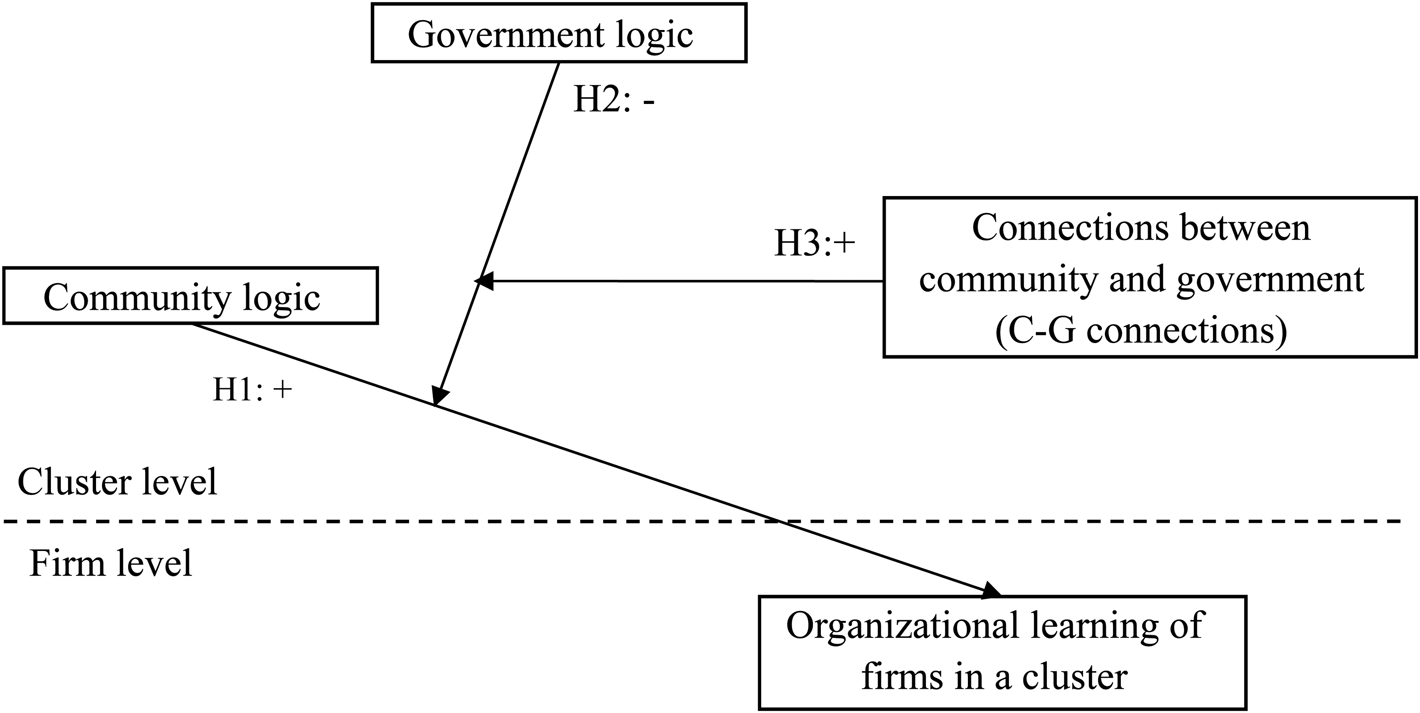

In the context of Chinese township clusters, government logic is enacted by providing certain (explicit or implicit) prescriptions that guide how a cluster should operate (Jia et al., Reference Jia, Li, Tallman and Zheng2017). Motivated by GDP growth, policymakers from Chinese local governments build public service centers to coordinate knowledge transfer and learning among firms in clusters (Wei et al., Reference Wei, Zhou, Greeven and Qu2016). For instance, town-level public service centers in Suzhou city built certain platforms and specified rules and standards regarding who can or cannot participate and guided entrepreneurs on how to interact with each other (Wei et al., Reference Wei, Lu and Chen2009). Thus, although it may enhance learning in one way or another, government logic may be incongruent with community logic with respect to firms’ localized learning. The next section develops hypotheses based on the framework shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework

HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

Community Logic and Organizational Learning

We theorize that community logic in a cluster will advance firms’ localized learning within a cluster through two mechanisms. First, community logic increases a firm's willingness to use the cluster as a key learning vehicle to learn from collocated organizations. Community logic shapes a sense of social solidarity based on mutual-benefiting and cooperative behavior that governs how organizations interact with each other in the community. Community logic thus helps curb opportunism or self-interest seeking with guile (Williamson, Reference Williamson1985), whereby partners exploit interfirm relationships for their own interests (Inkpen & Tsang, Reference Inkpen and Tsang2005). Because it ‘rewards’ norm followers and sanctions norm-breakers (Marquis, Lounsbury, & Greenwood, Reference Marquis, Lounsbury and Greenwood2011), strong community logic incentivizes firms to engage in community-based knowledge exchanges and learning.

In the context of Chinese township clusters, community logic rewards entrepreneurs who honor their commitments and do not renege on deals (Nee & Opper, Reference Nee and Opper2012) and sanctions opportunistic behaviors. Opportunists will be exposed to the community and pay the cost of malfeasance because as ‘time passes, others will find out about everything’ (Nee & Opper, Reference Nee and Opper2012: 147). Community logic in Chinese township clusters thus serves well as a mechanism reducing opportunistic expropriation and promoting learning. Firms in a cluster with strong community logic will find the community's atmosphere to be trustful and conducive to knowledge sharing and will therefore be more willing to engage in mutually beneficial learning activities.

Second, community logic increases a firm's ability to learn by facilitating the identification of the right knowledge-sourcing partners and the acquisition of knowledge from these partners. Community logic defines a set of behavioral schemata for the actors (Almandoz, Reference Almandoz2014). Through their social embeddedness in a community, entrepreneurs can internalize the value of mutual support, increasing awareness of resource distribution (Almandoz, Reference Almandoz2012). In a related vein, scholars emphasize the importance of networking for organizational learning, suggesting that social ties help firms navigate away from uncertainty through the development of collaborative behaviors and the ability to identify and take advantage of more learning opportunities (Inkpen & Tsang, Reference Inkpen and Tsang2005). Well-connected firms are more likely to overcome the problems of information asymmetry and can therefore better identify partners who possess complementary knowledge (Arikan, Reference Arikan2009). Applying this view, strong community logic strengthens social ties among firms in a cluster that can provide them with precise information about who knows what in the cluster, enhancing the effectiveness of searching for knowledge sources at a lower cost (Nee & Opper, Reference Nee and Opper2012). Accordingly, strong tie-based community logic – and not geographic proximity of firms within a cluster – influences the effectiveness of knowledge identification and exchanges learning. In other words, learning outcomes differ in different communities because of variations in the strength of community logic rather than geographic proximity.

As firms in the same community are linked through a common understanding of the accepted ways of learning due to their shared history (Levitt & March, Reference Levitt and March1988), community logic also enhances a firm's knowledge acquisition ability. In our case, community logic legitimizes certain informal ways of learning. For example, a strong community logic in the township cluster embeds social ties and common values among community members (Almandoz, Reference Almandoz2012; Lee & Lounsbury, Reference Lee and Lounsbury2015). In turn, this embedment promotes the development of personal trust among these members and, thus, enhances their informal learning with each other (Nee & Opper, Reference Nee and Opper2012). Survey-based data on the Yangtze River Delta region corroborate this view and show that more than 65 percent of firms’ technical collaborations were facilitated by factory visits, informal observations, and personal consultations in clusters; more than 86 percent of the firms utilized personal introductions and circles of friends to acquire customer information (Nee & Opper, Reference Nee and Opper2012). Such a common understanding of ‘how to learn in a community’ enhances firms’ ability to learn by reducing the cost of knowledge acquisition and increasing the value of organizational learning between firms. Therefore, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 1: Community logic is positively associated with the organizational learning of firms in a cluster.

Moderating Role of Government Logic

The role of bureaucratic institutions in organizational learning was highly emphasized by Levinthal and March (Reference Levinthal and March1993). Cluster scholars suggest that governments often actively engage in guiding firms’ localized learning (Arikan & Schilling, Reference Arikan and Schilling2011). Although multiple logics may coexist in the same community, the relationships between these logics rely on the specific context of the phenomena under investigation. In our case, local governments in China view clusters as an important instrument for catalyzing economic growth (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Li and Schoonhoven2009). This kind of government involvement is based on and has also gradually shaped certain government logic intervening with the operations of the cluster. Unlike community logic, government logic is exercised by local governmental interest groups and imposed in a top-down fashion (Lee & Lounsbury, Reference Lee and Lounsbury2015).

However, although the local government's involvement in clusters is intended to promote firms’ learning, as an outsider, the local government has limited knowledge about the community (Nee & Opper, Reference Nee and Opper2012). It thus may unintentionally apply ineffective policies or practices that hamper interfirm learning within the cluster in one way or another. Therefore, in line with the view that state logic interferes with community-based forces (Marquis & Lounsbury, Reference Marquis and Lounsbury2007; York et al., Reference York, Vedula and Lenox2018), we propose that government logic may dampen the positive effect of community logic on firms’ learning in a township cluster.

First, government logic may weaken the effect of community logic by hampering a firm's willingness to engage in cluster-based learning. From the discussion above, as it is based on the dense ties between members and the commonly accepted norm of ‘how things should be done’ that curbs opportunism, community logic increases a firm's willingness to learn from collocated partners in the cluster. However, in playing its role in coordinating knowledge exchange among firms (Jia et al., Reference Jia, Li, Tallman and Zheng2017), a local government may bring their own policies and rules for knowledge exchange into the community. In our context, local governments introduced external entities into the township clusters (Wei et al., Reference Wei, Zhou, Greeven and Qu2016). Because these practices may be motivated by objectives, such as the promotion of regional GDP growth that are not entirely congruent with those of the firms in the cluster, the ‘invasion’ of government logic disrupts the existing rules and routines of learning that have long been established based on community logic. For example, both the extant literature (e.g., Nee & Opper, Reference Nee and Opper2012) and interviews from our field visits show that the local governments of township clusters often introduce external firms and universities not in the area into existing local business networks and promote their interactions with the local firms. Although this intention is undoubtedly good when assisting local firms, these firms often have to make greater efforts and pay higher costs to facilitate inter-organizational learning with these external collaborators. Because they are not familiar with each other, informal and community-based norms and social mechanisms may not work well in such cases; instead, they will have to use formal contracts or other market-based mechanisms that increase transaction costs. As a result, government logic may create inconsistencies and place them in the middle of the two logics, thereby reducing their willingness to engage in community-based learning activities.

Second, government logic may disrupt a community's social structure and the community-based informal ways of learning, thus hampering a firm's ability to learn by using the cluster as a vehicle. Bell, Tracey, and Heide (Reference Bell, Tracey and Heide2009) argue that the common understanding of how to learn helps cluster firms effectively transfer know-how. However, as outsiders, governments may have a limited understanding about what knowledge can be beneficial for firms, who have certain knowledge, and how other firms can gain access to it. In contrast to informal ways of learning that communities embrace, governments, due to their bureaucratic and command-and-control frameworks, often promote formal ways of learning (Thornton et al., Reference Thornton, Ocasio and Lounsbury2012) that disrupts the social fabric of the cluster. For example, local governments in China set up public service centers in township clusters with the aim of promoting firms’ learning by holding product exhibitions, sponsoring official symposiums, and organizing regular salons and workshops for knowledge sharing. In such cases, governments act as intermediaries to promote interactions between firms (Jia et al., Reference Jia, Li, Tallman and Zheng2017). Despite good intentions, however, the imposition of a formal learning method may disrupt the well-established person-based informal way of learning in the cluster. In this regard, both prior research (Nee & Opper, Reference Nee and Opper2012) and anecdotal evidence from our field work show that public service centers often encourage and select certain groups of local firms into the platforms based on the standards and policies of the town governments, which, at times, conflict with the community logic operating in the cluster. For instance, public service centers often implement policies or take initiatives that prioritize the selection and cooperation of high-tech and/or large companies (Nee & Opper, Reference Nee and Opper2012; Wei et al., Reference Wei, Zhou, Greeven and Qu2016) because they believe that these firms have greater potential in promoting regional development. Although these intentions are good, this type of top-down approach may conflict with firms’ self-generalized collaborations based on their trust and commitment embedded in the community logic. Consequently, firms have to deploy additional resources, time, and attention to conforming to institutional prescriptions and accommodating new partners. This in turn increases learning costs, reducing the ability of firms to enhance organizational learning by taking advantage of clusters.

In sum, due to the ‘invasion’ of local governments, firms in the cluster may find themselves caught between community logic and government logic. They must strike a delicate balance between these two logics and move away, to a degree, from the well-established ways of learning that have been dictated by the community logic to accommodate the demands of the government and new partners. In turn, their willingness and ability to enhance learning through community logic is reduced. Hence, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 2: Government logic will negatively moderate the effect of community logic on the organizational learning of firms in a cluster such that the positive relationship will be weakened when the government logic is stronger.

Moderating Role of the Connection Between Community and the Government

According to Besharov and Smith (Reference Besharov and Smith2014: 369), the coexistence of ‘both multiple and powerful logics’ represents a typical situation of the high centrality of institutional multiplicity, defined as the ‘degree to which multiple logics are each treated as equally valid and relevant to organizational functioning’. The same authors further postulate that whether multiple logics will lead to substantial conflicts is contingent on the degree of compatibility of the different logics, defined as ‘the extent to which the instantiations of logics imply consistent and reinforcing organizational actions’ (Besharov & Smith, Reference Besharov and Smith2014: 367). In other words, the impact of multiple logics is determined by both the number of logics and the degree of compatibility among these logics. Multiple logics can coexist peacefully when they carry inherently consistent prescriptions of social actions (Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta and Lounsbury2011). Building on this view, we argue that although government logic may negatively moderate the effect of community logic on firms’ localized learning, strong social connections between the firms in the cluster and local governments can mitigate this negative effect.

Besharov and Smith (Reference Besharov and Smith2014) suggested that the close connections developed through socialization between different groups of actors influences the compatibility of the logics they represent. In contrast, the segmentation of coexisting logics generates less complementarity due to a lack of interactions between their representatives (Smets et al., Reference Smets, Jarzabkowski, Burke and Spee2015). Applying this view, we suggest that strong community and government (C-G) connections help attenuate the contradictions between community logic and government logic and allow the two institutional constituencies to reach more consistent understandings about how firms in the cluster should interact, thereby enhancing organizational learning by mitigating the negative moderating effects of government logic asserted in Hypothesis 2.

First, strong C-G connections help local governments and communities embrace each other's rules and norms of organizational learning. For example, through participating in various social events, local governments are more aware of the tacit interpersonal relationships and the power dependences among firms in the cluster. This, in turn, helps the local governments not only to better understand the social norms operating within the cluster but also comprehend why and how the cluster as a community has developed such particular norms to guide interfirm learning. Similarly, these events also provide opportunities for firms to connect with local governments more closely and increase their understanding about the objectives and rules of the governments’ involvement in the cluster. Assisted by these mutual understandings, local governments and communities can better develop compromises with respect to the goals and strategies used for organizational learning. Therefore, when community logic and government logic coexist in the same cluster, strong C-G connections help to alleviate the negative effect of government logic.

Second, strong C-G connections increase the ability to develop common understandings about ‘who knows what’ and the specific ways firms learn, thus attenuating the negative effect of government logic. Hitt, Bierman, Uhlenbruck, and Shimizu (Reference Hitt, Bierman, Uhlenbruck and Shimizu2006) argued that the high-level relational capital of professionals improves communication and the alignment of goals between the local community and government. This view is in line with Tallman et al. (Reference Tallman, Jenkins, Henry and Pinch2004), who suggested that strong connections between actors within a community enhance the understanding of each other's ways of doing things. In our context, strong C-G connections with firm managers enable government officials to be better able to understand the stock and distribution of knowledge in clusters and how such knowledge can be shared between firms. Equally, such connections also enable firms to develop a better understanding of the specific ways through which the government assists firms’ learning (e.g., by building public services centers). As the top-down approach used by the government and the bottom-up approach used by the community converge, the government and entrepreneurs will be able to blend more elements of formal procedures (from the government) with person-based routines (from the community). As a result, organizational routines regarding which knowledge can be beneficial, who should be suitable knowledge source partners, and how knowledge can be shared will be better aligned with the objectives and approaches of the government.

In contrast, weak C-G connections will limit the opportunity for government logic and community logic to adapt to each other. As the members of each group emphasize the legitimacy of their rules vis-à-vis that of the other rules, the compatibility of the different logics is compromised, inhibiting firms’ learning based on community logic. In sum, when community logic and government logic coexist in the same cluster, strong C-G connections harmonize the incompatibilities of the two logics and therefore help mitigate the negative effect of the government logic on learning. Thus, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 3: The relationship between community logic and the organizational learning of firms in a cluster will be moderated by both government logic and the connections between the local community and government (C-G connections), such that the negative effect of the interaction between community logic and government logic will be weaker when C-G connections are strong as opposed to weak.

METHODS

Sample and Data

Jiangsu Province in China is well known for a concentration of township clusters. We conducted an onsite survey of 60 township manufacturing clusters in this province during 2014 and 2015. First, based on the website of Jiangsu Province's Small and Medium-sized Enterprise Bureau (http://www.smejs.cn) and the homepages of the towns in Jiangsu Province, we identified a total of 170 township clusters. We contacted the leaders of all these clusters, and 60 showed willingness to participate in our research project. Among these 60 township clusters, we randomly selected ten firms from each as potential candidates in our sample. Finally, 577 firms from 60 township clusters participated in our survey. To collect relevant information at both the firm and cluster levels, the chairman of the local chamber of commerce and one mayor in each town were invited to be the cluster-level informants, while the CEOs and CFOs of the 10 selected firms were invited to be the firm-level informants. This procedure is the ‘most effective in reducing common method bias’ (Poppo & Zhou, Reference Poppo and Zhou2014: 1517), and it enabled us to separate the measures of the independent variable, moderators, and dependent variable. After we checked the completed questionnaires, we obtained valid observations from 354 firms (with responses from 354 CEOs and 354 CFOs) distributed in 39 clusters (with responses from 78 local elites). The effective response rate was 61% (354 of 577 firms) at the firm level and 65% (39 of 60 clusters) at the cluster level.

We performed two multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVAs) to test for nonresponse bias (Poppo & Zhou Reference Poppo and Zhou2014). The results indicated no significant differences between the non-respondents in our final sample in terms of a cluster's GDP, the number of firms and total profits in the last year (Wilk's Λ = 0.98; F = 0.42; p = 0.74) and firm characteristics, including last year's total profits, ownership and the number of employees (Wilk's Λ = 0.99; F = 0.95; p = 0.41).

Measures

Dependent variable

Using the items proposed in Lane, Salk, and Lyles (Reference Lane, Salk and Lyles2001), we asked firm CEOs to answer relevant questions regarding the extent to which their firms learned from other firms in the same cluster in terms of the following dimensions of knowledge: (1) new technological expertise, (2) new marketing expertise, (3) product development, (4) managerial techniques, and (5) manufacturing processes (1 = a little, 7 = a great extent). Cronbach's α is 0.94. The single-factor measure model fits our data well: χ2(5) = 88.80, p = .00; CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.90, and SRMR = 0.03. All factor loadings are higher than 0.85 and significant at the p = .001 level. The average variance extracted is 0.76, and the composite reliability is 0.94, exceeding the benchmark numbers of 0.50 and 0.70, respectively.

Independent variable

We used the age of the local chamber of commerce (i.e., the number of years since it was established) in 2015 to measure the strength of the community logic in a focal cluster. These data were reported by the chairman of the local chamber of commerce. According to the extant literature (Almandoz, Reference Almandoz2014; Lee & Lounsbury, Reference Lee and Lounsbury2015), community logic emerges from the historical co-experiences of geographically bounded members and embeds in their social ties. In the case of township clusters, entrepreneurs often establish local chambers of commerce to develop their common identity, share information, and facilitate collaborations. For instance, our field work in the cluster of Hangji in Jiangsu province shows that, because of the co-experiences of local firms as members of the local chamber since 2000, they formed a strong common understanding and practices of sharing technological know-how based on their local identities and norms. Similarly, in the Danyang cluster, the over 20-year-old local chamber of commerce plays an important role in enabling active learning among local firms through the strong norms of knowledge exchange. Accordingly, the age of the local chamber of commerce well captures the definitional features of the community logic. If a cluster had not yet established a local chamber of commerce, we regarded it as in the emerging stage of forming a community logic; thus, the community logic was weak. In this case, we calculated the cluster's community logic as 0.

Moderators

We used the number of public service centers to measure the strength of government logic. The data were reported by the mayors of the township clusters. According to Jia et al. (Reference Jia, Li, Tallman and Zheng2017), one unique characteristic of China's township clusters is that the local government plays a pivotal role in fostering or even ‘managing’ regional development by designing a cluster's overall strategy, providing infrastructure and formulating supportive policies. To facilitate organizational learning, local governments typically establish public service centers to encourage collaborations among cluster firms. Our interviews with local cadres from government agencies provided supportive evidence for this observation. For example, as officers from the Suzhou Science and Technology Bureau and the Loufeng town government in Suzhou city stated, based on their own criteria, certifications and judgments, their public service centers often helped firms to participate in regular forums and salons to enhance their interactions. As government-based information sharing platforms, these centers have helped to initiate and stimulate substantial knowledge exchanges among the selected firms. Hence, based on their beliefs regarding regional development, this top-down approach could reflect the coordinating mechanism local governments designed to promote interfirm organizational learning. Accordingly, we measured the strength of government logic as the number of public service centers in a township cluster.

Connections between community and the government (C-G connections)

The insight and measurement of this construct originated from previous studies (Li & Atuahene-Gima, Reference Li and Atuahene-Gima2001; Nee & Opper, Reference Nee and Opper2012) that captured firm-level political connections. The data were provided by the chairmen of the local chambers of commerce. To make this construct appropriate for measurement at the cluster level, we conducted a number of informal interviews and then adapted the above scales by focusing on the features of the relation between a town government and its collocated firms as a whole entity. Our measurement thus reflects the cluster-level variances in C-G connections across different township clusters. Specifically, we invited the chairmen of the local chambers of commerce to evaluate the following: ‘To what degree does the local government’: (1) ‘engage in social interaction with the executives and managers of the firms in the township’; (2) ‘know the social relationships among cluster firms’; and (3) ‘introduce specific firms or managers to each other’ (1 = very little, 7 = very much). Cronbach's α was 0.95. The factor loadings of the three items were all higher than 0.89 and were also significant at the p = 0.001 level. The AVE was 0.86, and the composite reliability was 0.95, exceeding the benchmarks of 0.50 and 0.70, respectively.

Control variables

At the cluster level (objective data were provided by the chairmen of local chambers of commerce), we added the cluster's overall sales and profits (in 100 million yuan) to control for cluster size and performance, respectively. We used a dummy variable, cluster certification (a cluster is coded as 1 if it was officially certified by the provincial government and 0 otherwise). This variable reflected a focal cluster's status and performance, capturing the willingness and opportunity of a firm to learn inside the cluster. To control for the effect of a cluster's knowledge base (Arikan, Reference Arikan2009), we added the total numbers of R&D centers in a focal cluster. As firm-level controls (objective data were provided by the CFOs of the firms), we included firm size, using firm last year's sales (in 100 million yuan), and firm age, using the number of years since the firm was founded. To control for ownership type, we distinguished foreign firms (international joint ventures and foreign-owned firms, coded as 1) from domestic firms (state-owned and private firms, coded as 0) (Sheng, Zhou, & Li, Reference Sheng, Zhou and Li2011). A firm's own R&D capability and its knowledge sources outside the cluster may influence its learning orientation (Arikan, Reference Arikan2009). To control for this effect, we included a firm's R&D intensity (the ratio of R&D expenditures to sales) and its numbers of R&D branches outside the cluster. Finally, to account for the role of sectoral differences, the firms were categorized into 17 industries based on their two-digit SICs.

RESULTS

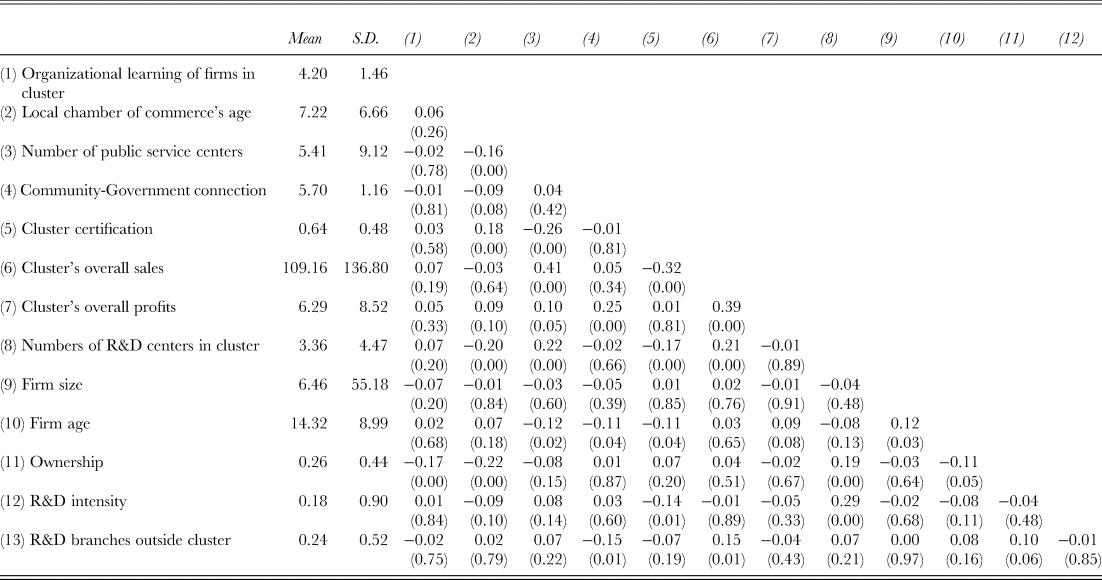

The descriptions and correlations are presented in Table 1. The variance inflation factor (VIF) ranges from 1.02 to 1.67. The average value is well below the acceptable level of 10, indicating that multicollinearity does not have an undue influence on the estimates.

Table 1. Description and correlations

Notes: The industry dummies are not included in the correlation matrix but are included in the model estimations. P values are in parentheses.

Analytical Strategy

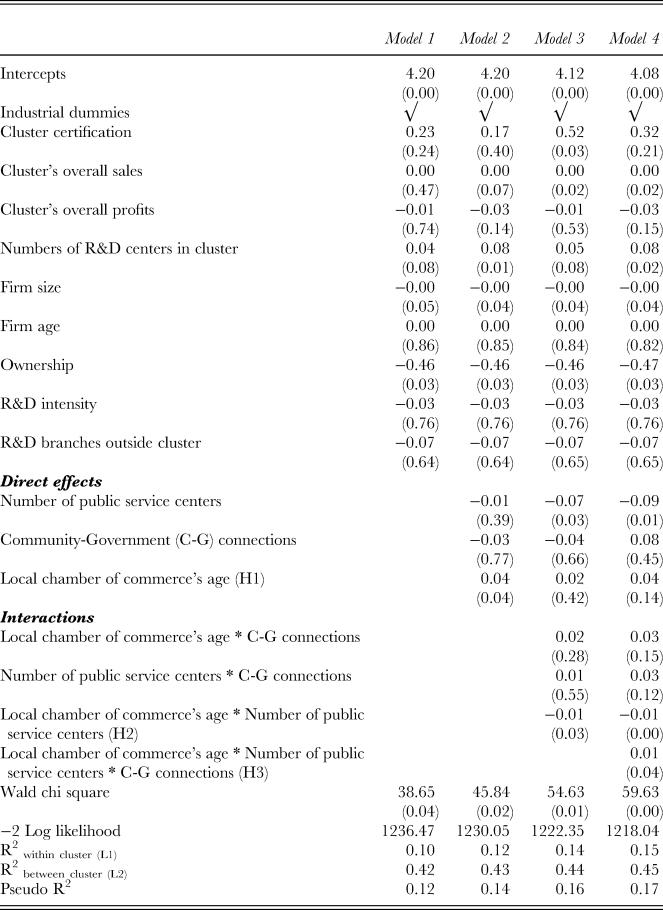

The data in our sample had a hierarchical structure, with firms being nested within a cluster. Accordingly, we employed multilevel modeling, allowing us to better test our cross-level predictions (Klein & Kozlowski, Reference Klein and Kozlowski2000). Our cluster-level sample size is 39, which is more than the general rule-of-thumb requirement of 30 in multilevel modeling analysis, enabling us to obtain accurate estimations (Snijders, Reference Snijders, Everitt and Howell2005). Following the suggestion by Hofmann, Griffin, and Gavin (Reference Hofmann, Griffin, Gavin, Klein and Kozlowski2000), we centered the cluster-level variables around the grand mean of the sample and centered the firm-level variables around each cluster's mean. This ‘best practice’ (Aguinis, Gottfredson, & Culpepper, Reference Aguinis, Gottfredson and Culpepper2013: 1490) allowed us to separate within-cluster and between-cluster variance and thus generate unbiased coefficient estimates. Before we tested our hypotheses, we ran a null model in which no predictors were included. This model ensured the significance of the between-cluster differences in organizational learning behaviors. The results showed that ICC 1 = 0.07, suggesting that 7% of the variance in the dependent variable systematically resided between clusters. Thus, empirically, multilevel modeling was appropriate for our study. Table 2 summarizes the results.

Table 2. Result of multi-level modeling

Notes: Unstandardized coefficients are reported, with p values in parentheses; Pseudo R2 = (R2 within cluster * (1-ICC1) + R2 between cluster * ICC1).

Hypothesis Testing

As shown in Table 2, the pseudo R2 increased from 0.12 in Model 1 to 0.17 in Model 4, providing general support for our theoretical predictions. Compared with the null model, Model 1 contributed 10% of the within-cluster variance, 42% of the between-cluster variance and 12% of the total variance in organizational learning, indicating that we included meaningful control variables in our model. Model 2 shows that community logic is positively and significantly related to organizational learning (b = 0.04, p = 0.04), supporting Hypothesis 1. Comparing Model 2 with Model 1, we observe that community logic explained an additional 2% of within-cluster variance, an additional 1% of between-cluster variance and an additional 2% of total variance in organizational learning.

Hypothesis 2 states that government logic negatively moderates the positive relationship between community logic and firms’ organizational learning. Model 3 shows that the cross-level interaction between community logic and government logic is negative and significant (b= -0.01, p = 0.03). This result suggests that when government logic is strong, community logic is less likely to promote organizational learning. Comparing Model 3 with Model 2, we observe that the cross-level effect accounts for an additional 2% of within-cluster variance, an additional 1% of between-cluster variance and an additional 2% of total variance compared to the results of the model with only the direct effects of the cluster-level predictors. Hypothesis 2 is thus supported.

Finally, Hypothesis 3 proposes that the relationship between community logic and organizational learning varies depending on government logic and the connections between the community and the government. Model 4 shows that the coefficient of the three-way interaction between community logic, government logic and C-G connections is positive and significant (b = 0.01, p = 0.04). Again, comparing Model 4 with Model 3, we observe that our test explained an additional 1% of within-cluster variance, an additional 1% of between-cluster variance and an additional 1% of total variance. The result indicates that the three-way interaction provides a unique explanation for organizational learning, in addition to the effects of the control variables, the direct effects and those of the two-way interaction between community logic and government logic. Hypothesis 3 is thus supported.

Supplemental Analysis

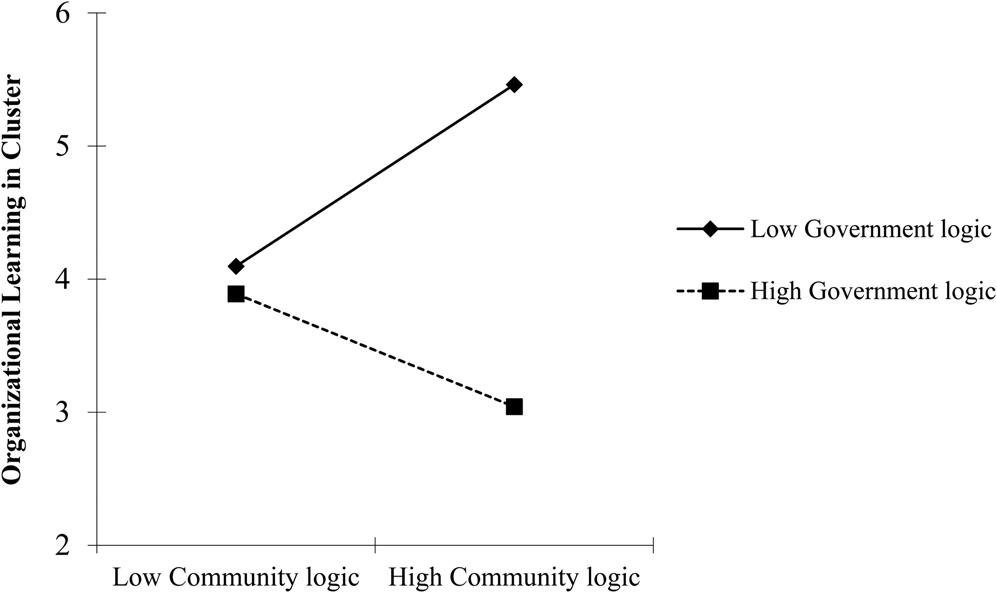

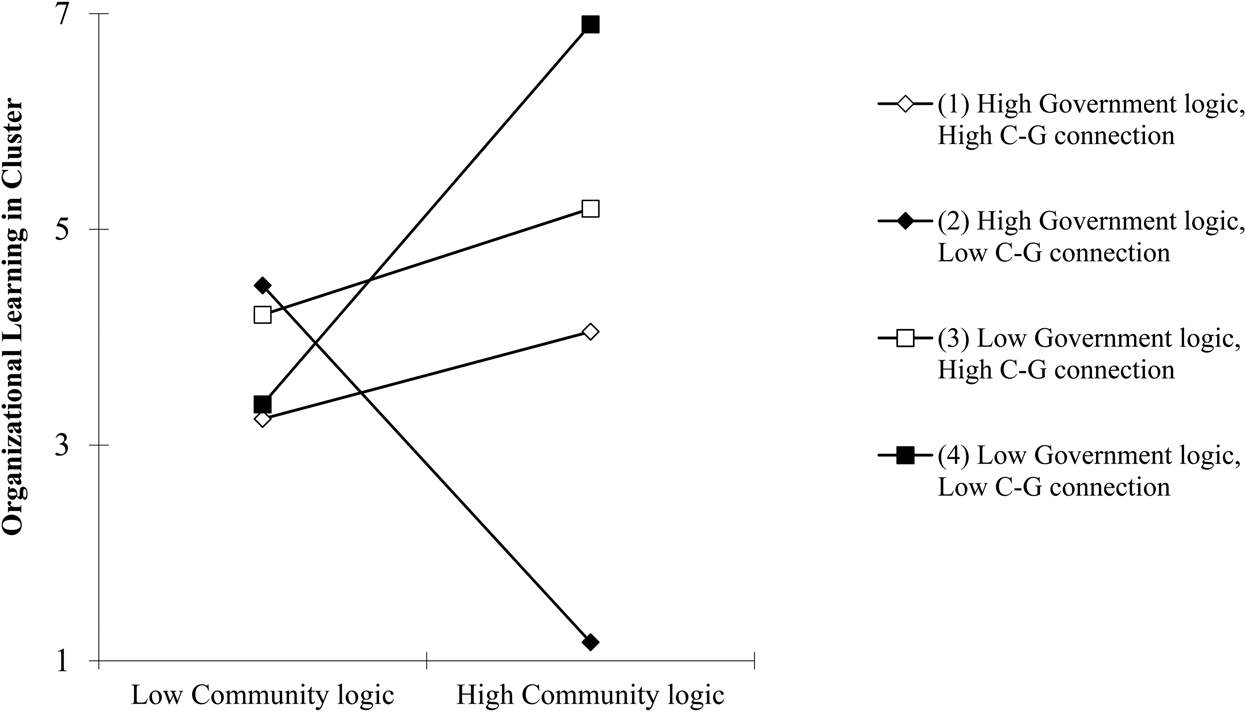

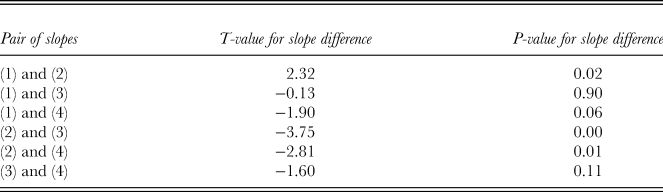

Using tools developed by previous studies (Preacher, Curran, & Bauer, Reference Preacher, Curran and Bauer2006), we conducted the simple slope analysis and slope difference tests of the combined effect of community logic, government logic, and C-G connections on organizational learning. The high and low values are set at one standard deviation above and below the mean value, respectively. These analyses helped us to better interpret the above results; see Figure 2, Figure 3, and Table 3.

Figure 2. Moderation effect of community logic on organizational learning at low and high levels of government logic–hypothesis 2

Figure 3. Three-way interaction with organizational learning as dependent variable–hypothesis 3

Table 3. Slope differences test for three-way interaction

Figure 2 shows that the relationship between community logic and organizational learning is positive and significant when government logic is weak (b = 0.10, p = 0.00) and negative but not significant when government logic is strong (b=-0.06, p = 0.24). These results suggest that the effect of the community on organizational learning is stronger when the community imposes a dominant logic and that it is weaker when a strong competing logic of the local government is present. Again, these findings support our first two hypotheses.

Figure 3 plots the result of a simple slope analysis of the moderating effects of government logic on the relationship between community logic and organizational learning when government logic and C-G connections are simultaneously considered. First, the main effect is positive when both government logic and C-G connections are weak (slope 4, b = 0.26, p = 0.01), and the effect is nonsignificant when both government logic and C-G connections are strong (slope 1, b = 0.06, p = 0.44) and when government logic is weak and C-G connections are strong (slope 3, b = 0.07, p = 0.09); furthermore, the effect is negative when government logic is strong and C-G connections are weak (slope 2, b= -0.25, p = 0.01). Thus, as predicted, the relationship between community logic and organizational learning varies depending on the relative levels of both the government logic and C-G connections. These results generally corroborate Hypothesis 3.

Second, we predicted that the negative two-way interaction between the community logic and government logic would be weakened when C-G connections are strong as opposed to weak. In Figure 3, this two-way interaction at a low level of C-G connections is depicted by slope 2 and slope 4, while that at a high level of C-G connections is depicted by slope 1 and slope 3. Following previous studies (e.g., Nishii & Mayer, Reference Nishii and Mayer2009), these two pairs of slopes were jointly considered, and we show evidence corroborating Hypothesis 3.

When C-G connections are low, the effect of community logic on organizational learning is positive when government logic is weak (slope 4), while this effect is negative when government logic is strong (slope 2), and the difference in these two slopes is statistically significant (slopes 2 and 4 in Table 3, p = 0.01). Under this circumstance, local governments impose a competing logic against the community logic, thereby weakening the relationship between the community logic and organizational learning. When C-G connections are high, however, the effects of community logic on organizational learning are nonsignificant regardless of whether the level of government logic is weak (slope 3) or strong (slope 1), and the difference in these two slopes is not significant (slopes 1 and 3, p = 0.90). In this case, a buffering effect emerges as the C-G connections increase, preventing the effect of community logic on organizational learning from being weakened by the intervention of the government logic. Overall, the interaction effect between community logic and government logic, as demonstrated by the differences in the effect of community logic on organizational learning when the government logic is strong versus weak, is less pronounced when C-G connections are high (slopes 1 and 3) than when C-G connections are low (slopes 2 and 4). Moreover, when the government logic is strong, the negative relationship between the community logic and organizational learning (slope 2) can be effectively alleviated as the C-G connections increase (slope 1). Again, the significant difference (slopes 1 and 2, p = 0.02) indicates the critical role of C-G connections in increasing compatibility of these two strong institutional logics. However, the difference between slopes 3 and 4 was not statistically significant (slopes 3 and 4, p = 0.11). This result indicates that C-G connections have a buffering effect on the relationship between community logic and organizational learning when the government logic is strong. Hypothesis 3 is supported.

Finally, like almost all cross-sectional studies, reverse causality may threaten the coefficient estimations. Clusters with lower levels of interfirm learning may attract more government attention. This in turn may lead the government to build more public service centers in these clusters. As such, government logic may be endogenous to firms’ learning, contaminating our results. We conducted two additional tests to address this concern. We first used the two-stage instrumental variable regression method (Brahm & Tarziján, Reference Brahm and Tarziján2014; Laursen, Masciarelli, & Prencipe, Reference Laursen, Masciarelli and Prencipe2012). In the first stage, we used cluster human capital, measured as the percentage of employees with university degrees or above in a township cluster, as our instrument. On the one hand, as human capital at the cluster level implies high-quality development potential, governments are likely to invest more in public service centers (Nee & Opper, Reference Nee and Opper2012) in clusters with a higher level of human capital. Therefore, cluster human capital should be highly correlated with government logic. On the other hand, although human capital may help firms search for talent and knowledge, clusters with a higher level of human capital tend to be more sensitive about losing knowledge and therefore build strong mechanisms to prevent talent from leaving and knowledge from leaking. Hence, cluster human capital is less likely to influence individual firms’ learning in the cluster. Empirically, we find that cluster human capital has a positive and significant effect on the number of public server centers (b = 24.83, p = 0.00), yet it has a nonsignificant effect on organizational learning (b = -0.95, p = 0.10). Thus, our instrument is valid both theoretically and empirically (Wooldridge, Reference Wooldridge2002).

In the second stage, we regressed the outcome variable organizational learning on the predicted number of public service centers obtained from the first-stage regression, in addition to all exogenous explanatory variables that are used in the first-stage. The estimated results from the second-stage regression show that the interaction effect of community logic and government logic on organizational learning is still negative and significant (b = -0.01, p = 0.01). In addition, following Jandhyala and Phene (Reference Jandhyala and Phene2015), we adopt a two-stage residuals inclusion method in which the residuals from the first-stage estimation are included as an additional explanatory variable in the second stage. Again, we find evidence of a negative moderation effect of government logic (b = -0.01, p = 0.04), corroborating Hypothesis 2. Furthermore, we follow Zhu and Chung (Reference Zhu and Chung2014) and run a regression using the number of public service centers as the dependent variable and organizational learning at the cluster level as the moderator. The analysis indicates that this relationship is statistically nonsignificant, suggesting that reverse causality is not a substantial problem in our empirical analysis (Landis & Dunlap, Reference Landis and Dunlap2000).

DISCUSSION

Implications for Theory

First, moving beyond the role of the isomorphic diffusion of social norms (Levitt & March, Reference Levitt and March1988), we develop a fine-grained framework for understanding the institutional drivers of interfirm learning in a community. Viewing regional clusters as communities (Pouder & St. John, Reference Pouder and St. John1996; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Li and Schoonhoven2009), our analyses show that while community logic enhances a firm's localized learning, government logic weakens this effect. Our explanation is that while local governments, as a key stakeholder of clusters, strive to enhance interfirm learning, they may offer guidelines that contradict the usual ways firms engage in community-based learning. Further, the pursuit of political objectives by local governments means that they may provide coordinating mechanisms that are not aligned with local firms’ strategic priorities and community-based learning methods (Wang, Hong, Kafouros, & Wright, Reference Wang, Hong, Kafouros and Wright2012). Our findings suggest that community-based learning goes beyond the mechanism of isomorphic diffusion and is dependent on a complex configuration of multiple institutional logics. Thus, an important implication of our study is that to deepen the understanding of the role of the isomorphic diffusion of social norms in organizational learning, it is imperative to examine how other institutions operating in the community strengthen or weaken the role of isomorphism. Given that multiple institutions cooperate in a community (Marquis et al., Reference Marquis, Lounsbury and Greenwood2011), this is a promising direction to extend the seminal work of March and Olsten (Reference March and Olsen1983).

Second, our finding regarding the role of C-G connections in alleviating the conflicts between community logic and government logic advances the understanding of when logic multiplicity leads to conflicts and when it maintains harmony. Past research has tended to emphasize either a competing (e.g., York et al., Reference York, Vedula and Lenox2018) or a complementary (e.g., Jay, Reference Jay2012) relationship between multiple logics. The empirical evidence on the effect of institutional multiplicity on organizational behaviors and outcomes is just as equivocal. Our study extends this line of research by suggesting that different logics could be both competing and complementary (Smets et al., Reference Smets, Jarzabkowski, Burke and Spee2015), depending on the connections between the different logics. We demonstrate that even when multiple logics provide conflicting prescriptions, the social connections between actors who carry these logics can help mitigate the competing effect. Therefore, moving beyond recent studies that emphasize the conflicting nature of institutional multiplicity (e.g., Yan et al., Reference Yan, Ferraro and Almandoz2019), we offer a more nuanced explanation of why logics compete in certain situations but are complementary in others. Furthermore, although some studies have suggested that logic compatibility may change continuously (e.g., Besharov & Smith, Reference Besharov and Smith2014; Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta and Lounsbury2011), the extant literature to date has offered little insight into when a certain competing effect resulting from logic multiplicity may become less competitive or even mutually supportive. Our framework reveals that, although the co-existence of multiple logics may increase the competing effect on actors, the social connections between these actors can alleviate this effect. Such connections enable local governments and communities to increase the understanding of each other's rules and norms of organizational learning and each other's specific ways of learning. Hence, because C-G connections foster the mutual adaptation of local governments and communities and enable the development of consistent goals and means, they help attenuate the negative effect of government logic. This study thus serves as a direct response to Besharov and Smith (Reference Besharov and Smith2014)'s call for research investigating the conditions under which multiple logics can achieve compatibility. This finding implies that future research on the role of multiple logics should not only consider the interactions of these logics but also the levels of connections between them to arrive at a more nuanced understanding of how institutional complexity influences firm outcomes.

Implications for Practice

First, we show that government logic hampers the positive effect of community logic on firms’ learning by imposing a competing logic. This finding suggests that when a strong community logic operates in clusters, local governments should minimize their intervention in these clusters, as this action may unintentionally interfere with the role of community logic. This of course does not mean that the government should not be involved in the operations of clusters at all, as this is practically impossible given the pervasive impact of government in countries such as China. Rather, we suggest that governments should help clusters nurture community logic and perhaps give them more discretionary power in regard to issues related to interfirm learning within a cluster. Instead of simply selling the ‘best practice’ policy template, local governments should fine-tune their policies to resonate with the conditions of clusters and curate interfirm learning in a way that is harmonious with the isomorphic diffusion of norms.

Second, we find that through social connections, communities and governments are able to codevelop understandings that help mitigate the competing effect of government logic on learning. This finding suggests that when government logic interferes with community-based organizational learning in a cluster, firms should not simply respond by avoiding interacting with governments; quite the contrary, these firms should actively build connections with the government to forge common cognitions of each other's objectives, intentions and approaches. Meanwhile, managers should also realize that although C-G connections may help firms compensate for environmental uncertainty (Liu, Yang, & Augustine, Reference Liu, Yang and Augustine2018), overreliance on connections with governments may be counterproductive, as it may reduce their motivation to increase entrepreneurial learning capabilities (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Hong, Kafouros and Wright2012). Overall, our findings suggest that firms and local governments should work in concert to enhance the compatibility of different institutional logics that operate in clusters to maximize the learning effectiveness of firms.

Limitations and Future Research

First, as we focus on how government logic influences the effect of community logic on firms’ learning in a cluster, we do not compare the direct effects of these two logics or explore the conditions under which one logic may outweigh the other. Future research that compares these effects would complement our study. Second, as logics that are not related to government may also exist in a community, future research can examine how these logics and community logic jointly influence firms’ organizational learning and how these logics differ from government logic in terms of interactions with the community logic. Finally, the multisource design in this study enables us to test several interesting hypotheses and conduct several robustness checks. However, like all studies relying on surveys, the nature of cross-sectional data does not allow us to accurately infer causality. Further research using longitudinal designs may help tease out this effect.

CONCLUSION

This study enhances our understanding of how institutional complexity unfolds in a community and influence firms’ organizational learning. Our findings show that organizational learning in a community depends on not only the strength of different institutional logics and the interactions among them, but also the social connections among their respective constituencies. By building on and going beyond March's seminal work, this study offers new insights on the antecedents and mechanisms of organizational learning in communities. It also adds to the growing scholarly debates on organizational behaviors under institutional complexity.