INTRODUCTION

The relationship between internationalization and performance has attracted researchers’ attention for more than 40 years, but empirical findings from more than a hundred studies have been described as heterogeneous, unconvincing, and contradictory (Aulakh, Reference Aulakh2009). As comparative firm-disadvantages influence the internationalization of emerging market (EM) firms (Cuervo-Cazurra & Ramamurti, Reference Cuervo-Cazurra and Ramamurti2017), a separate stream of literature has examined the link between internationalization and performance for EM firms. For example, Xiao, Jeong, Moon, Chung, and Chung (Reference Xiao, Jeong, Moon, Chung and Chung2013) stipulate an S-type relationship between internationalization and performance of Chinese firms, while Chen, Jiang, Wang, and Hsu (Reference Chen, Jiang, Wang and Hsu2014) suggest an inverted U-shaped relationship, moderated by the marketing and technological resources. Hsu, Chen, and Cheng (Reference Hsu, Chen and Cheng2013) report that for Taiwanese firms, the link between internationalization and performance is moderated by CEO's age, education level, and international experience. Zhang, Ma, Wang, and Wang (Reference Zhang, Ma, Wang and Wang2014) suggest that the link between internationalization and performance is positively moderated by strategic, structural, and operational flexibility. Clearly, research on EM firms is just as confusing and inconclusive as to what determines a positive link between internationalization and performance.

In this article, we challenge two predominant ideas. Firstly, the notion that internationalization in isolation can influence the performance of firms. While many important factors at firm, industry, and country level have been studied as moderators, rarely have they been combined to provide a more holistic and realistic account of internationalized firms’ performance. We adopt a strategic-fit research-approach, which asserts the necessity of establishing close and consistent linkages between the firm's strategy, structure, and environment (Venkatraman, Reference Venkatraman1989) in order to determine performance effects. We suggest that contingency theory offers the theoretical logic needed to answer the key research question here: what specific configurations of (internal and external) contingencies, international strategy, and structural characteristics drive organizational performance.

Second, the effects of internationalization on performance cannot be easily generalized as they vary depending on firms’ country of origin (Marano, Arregle, Hitt, Spadafora, & van Essen, Reference Marano, Arregle, Hitt, Spadafora and van Essen2016). The predominant separation of internationalized firms into developed and emerging market (EM) firms is inadequate because what is typical internationalization behavior for Chinese firms, for example, may not hold true for any other type of EM firms. Russian firms are a peculiar category of EM firms that deserves more attention as it can shed new light on the discussion about the internationalization-performance relationship. For example, the literature suggests that Russian firms are latecomers to the global stage, have limited international experience, do a very limited assessment of problems they may face abroad due to their ‘Russian image’, and have no guidelines on how to deal with such challenges (Panibratov, Reference Panibratov2015). Such a perilous international position requires special attention to determine potential positive performance effects. We offer two main contributions. First, we extend the classic contingency model (Donaldson, Reference Donaldson2001) by adding internationalization (scale and scope) as a new critical contingency in addition to task interdependence and task uncertainty. We test this on a sample of Russian firms, which originate from an institutional context marked by ambiguous property rights, incomplete transmission of information, uncertain and inconsistent government policies, and corruption (Luo & Park, Reference Luo and Park2001; Shenkar, Reference Shenkar1990). Such a precarious home market may jeopardize any positive effects associated with internationalization. However, we suggest that even at such a disadvantageous position, a multidimensional fit between organizational structure, external and internal contingencies can lead to specific strategic configurations that could bring positive performance effects for Russian internationalizing firms.

Second, contingency theory applications are numerous (see e.g., Donaldson, Reference Donaldson1987; Drazin & Van de Ven, Reference Drazin and Van de Ven1985; Tosi & Slocum, Reference Tosi and Slocum1984; Venkatraman, Reference Venkatraman1989) – for example, criterion-free vs criterion-specific, deductive vs inductive, and moderation vs mediation approaches. We move beyond the commonly employed fragmented contingency perspective, which typically examines a limited number of contingency factors by estimating a few two-way interactions effects. We use a more comprehensive approach that involves a large set of contingency factors. This approach allows us, instead of looking at a few variables or linear associations among such variables, to find frequently recurring clusters of attributes (Miller, Reference Miller1988). In line with modern empirical literature that takes a configurational approach, we apply a (fuzzy-set) Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA), an empirical method not based on traditional probabilistic thinking, but instead on Boolean logic (see, e.g., Fiss, Reference Fiss2007, Reference Fiss2011). FsQCA is instrumental in empirically analyzing how bundles of ‘independent’ variables work together to determine ‘dependent’ variables. Our approach demonstrates that there exist configurations, a result of a fit between a variety of contingencies and structural arrangements, leading to superior performance even for disadvantaged (internationally) EM firms such as Russian internationalized firms.

The structure of this article follows a typical inductive approach. As a start, we provide an overview of contingency literature and outline our guiding theoretical logic. Thereafter, we describe our methodology and summarize our findings. In our discussion, we inductively develop propositions for future empirical testing. We conclude with how our study contributes to the ongoing debate on the role of complex fit in improving organizational performance, reflect on this study's limitations and future research opportunities.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Our objective is to introduce an integrative framework to identify and explain various mechanisms that underlie performance effects by propelling the core argument in the fit literature that the degree of congruence between strategy, structure, and its (external and internal) context has significant performance implications (Aldrich, Reference Aldrich1979; Hofer, Reference Hofer1975). Fit generally refers to (a) the level of efficiency with which an organization matches its internal strengths and weaknesses with the external opportunities and threats (Andrews, Reference Andrews1980), and (b) the degree of effectiveness of strategy implementation in particular environments (Schwartz & Davis, Reference Schwartz and Davis1981).

Contingency logic stipulates that there is no one best way to design organizational structures, but rather that organizational performance is contingent on the fit between the environment, structures, and processes of the organization (Drazin & Van de Ven, Reference Drazin and Van de Ven1985). Burns and Stalker (Reference Burns and Stalker1961) developed propositions on how organizations should structure themselves in order to mitigate the impact of emerging contextual changes. The authors proposed that in stable environments, organizations should adopt a mechanistic structure, while in unstable environments, it is best to adopt an organic structure. Mechanistic structure is defined by low complexity, high centralization, high formalization, and stratification, while an organic structure is highly complex and has low formalization, centralization, and stratification. The organizational structure is thus viewed as a continuum that runs from a mechanistic to organic structure, affected by changes in organizational size, task uncertainty, and task interdependence contingencies (Burns & Stalker, Reference Burns and Stalker1961).

Chandler (Reference Chandler1962) suggests that changes in strategy are mainly responses to opportunities or threats created by changes in the external environment, which in turn trigger a necessity for structural alterations. For example, Task interdependence (i.e., diversification and integration) contingencies describe whether the activities of a firm are closely connected or not, in the horizontal and vertical organizational dimensions. Size is associated with diversification and increased bureaucratization, which means formalization and decentralization increase as well. Task uncertainty (i.e., technological change or environmental instability) causes uncertainty for the organization and its managers, creating the need for innovation and structural adaptation as a response to environmental and technological change (Burns & Stalker Reference Burns and Stalker1961; Hage & Aiken Reference Hage and Aiken1970). In the case of innovation, there will be reciprocal interdependence among the functional departments because of the necessary interaction between the research and the other strategy contingencies (Donaldson, Reference Donaldson2001). Past literature shows how performance is affected by structural adaptations in response to these specific contingencies. However, it remains unclear how performance is influenced by a far more complex bundle of contingencies an internationalizing firm faces and the structural choices it makes to accommodate them.

Next, we introduce the new contingency, internationalization, using the concept of fit and performance. We add internationalization as a new critical contingency in relation to size, task uncertainty, and task interdependence. We develop our arguments to accommodate the peculiarities of Russian internationalized firms, originating from a highly uncertain and institutionally constraining home context.

A Contingency Model of Internationalization-Performance Relationship

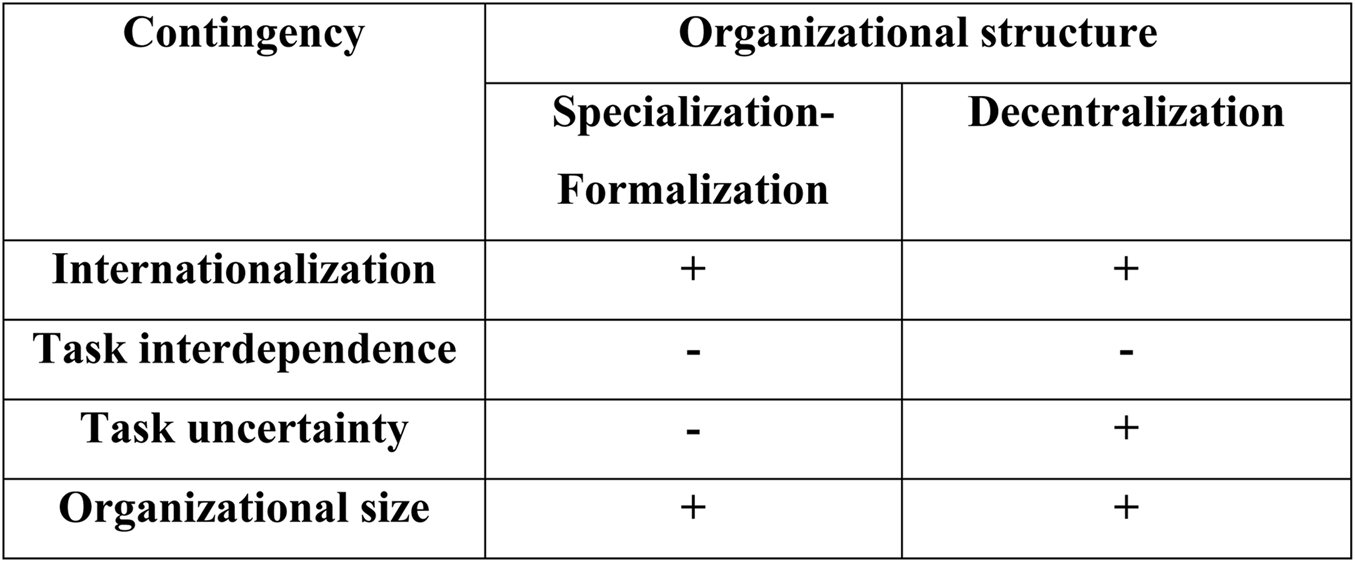

Organizational size is of central importance in contingency theory due to its inter-dependence on the task contingencies (Donaldson, Reference Donaldson2001). The key argument of contingency theory is that the fit between each of the structural elements and size positively affects performance (Figure 1). Internationalization is a natural extension to this model, as it is directly related to both size and task. For instance, in the process of internationalization, the organization increases in size encounter various forms of (external) uncertainties and alters the way intra-organizational activities are connected, thereby creating a degree of a misfit with the existing levels of structural adaptation. The negative performance feedback causes a structural change restoring fit.

Figure 1. Extended contingency theory model of organizational structure

Source: Adapted from Donaldson (Reference Donaldson2001)

Internationalization is achieved either by the increasing volume of internationally sold goods or services or by increasing the number of foreign markets served. We, therefore, separate this new contingency into internationalization scale and scope. Internationalization scale implies an increase in the proportion of sales to customers outside the home country, irrespective of the diversity of countries in which the focal firm operates. Internationalization scope increases international diversity by extending the spread of a firm's operations across different countries (Ghoshal & Bartlett, Reference Ghoshal and Bartlett1990). Next, we develop our arguments based on our logical inference for an inter-dependence between internationalization scale, organizational size, internationalization scope, the two task contingencies, and the desired match with structure to arrive at superior organizational performance.

A surge in internationalization activities (i.e., increasing internationalization scale), likely requires establishing communication channels abroad, securing financial resources to support international operations, hiring and training additional personnel to oversee internationalization efforts (Stopford & Wells, Reference Stopford and Wells1972). Exposure to international markets and greater competitive pressures would stimulate firms to constantly upgrade their products and adapt to new market conditions (Dikova, Jaklic, Burger, & Kuncic, Reference Dikova, Jaklic, Burger and Kuncic2016; Filipescu, Prashantham, Rialp, & Rialp, Reference Filipescu, Prashantham, Rialp and Rialp2013). As a result, there will be an increased demand for expanding the workforce with specifically qualified personnel to match internationalization requirements.

Internationalization activities are likely to exacerbate Russian firms’ organizational complexity due to their liabilities of foreignness (Lee, Kelley, Lee, & Lee, Reference Lee, Kelley, Lee and Lee2012). The ‘liability-of-foreignness’ arises from geographic, cognitive, and material distance and plays ‘a salient role in highlighting the costs of doing business in unfamiliar environments’ (Moeller, Harvey, Griffith, & Richey, Reference Moeller, Harvey, Griffith and Richey2013: 96). Moreover, Russian firms are likely to suffer from liabilities of country-of-origin as well. In their recent study Dikova, Panibratov, and Veselova (Reference Dikova, Panibratov and Veselova2019) note that in host countries displaying politically hostile attitudes towards Russia, acquisition deals initiated by Russian firms are viewed as a threat (and often opposed) because of perceived intervention by the Russian State in Russian firms’ business. These liabilities are likely to manifest as obstacles to successful internationalization. To overcome them, Russian firms would have to make investments in specialized human resources and develop specific organizational processes. For example, employees in internationalizing Russian firms may initially require training, or even stand idle, until the work processes are reorganized, and the new employees receive a specific assignment so that international specialization increases. Until specialization is increased to match the requirements of satisfying increasing demand in international markets (and fit the new firm size), there may be a temporary misfit that lowers performance. Internationalizing Russian firms with adequate management can, of course, avoid misfit by adjusting the level of horizontal structural specialization in parallel with increasing internationalization and organizational size. In this case, structure is changed because of contingency fit rather than negative performance feedback.

International specialization likely leads to higher levels of formalization. On the one hand, internationalizing Russian firms may adopt new organizational systems to reflect the new professional training required, and, on the other hand, the new systems are introduced to resolve unexpected problems encountered in the process of internationalization, especially because these problems are likely to affect performance negatively. In other words, higher levels of formalization are needed to regain fit and improve performance; formalization is, thus, indirectly caused by new administrative changes required by the increased scale of international operations. Finally, an increase in the number of levels in the organizational hierarchy impedes the flow of information to the upper levels of the organization, thus, rendering centralization less effective (Donaldson, Reference Donaldson2001). Performance of Russian firms is therefore positively affected by a fit between internationalization scale, specialization, formalization, and decentralization.

International scope increases gradually by adding new export destinations or establishing subsidiaries in new host countries. Past research reports that Russian internationalized firms primarily aim for growth of their global market share; thus, they mostly target developed market economies (Kalotay & Sulstratova, Reference Kalotay and Sulstarova2010). Consumers and governments in the west may impose inconsistent requirements or apply discriminatory treatment towards Russian firms (Miller, Lavie, & Delios, Reference Miller, Lavie and Delios2016). Diverse international environments, which include individuals, other organizations, technological and social forces, have a potentially significant impact on firm performance (Tushman & Nadler, Reference Tushman, Nadler, Gerstein, Nadler and Shaw1992). The diversity of the international environment creates uncertainty as it reflects not only inconsistencies in requirements by numerous stakeholders but also information asymmetries limiting the ability of Russian firms to properly respond to these requirements (Carpenter & Fredrickson, Reference Carpenter and Fredrickson2001). Below, we demonstrate how an organizational structural change occurs in response to international scope, task uncertainty, and task interdependence, as a way to establish the fit with the environment.

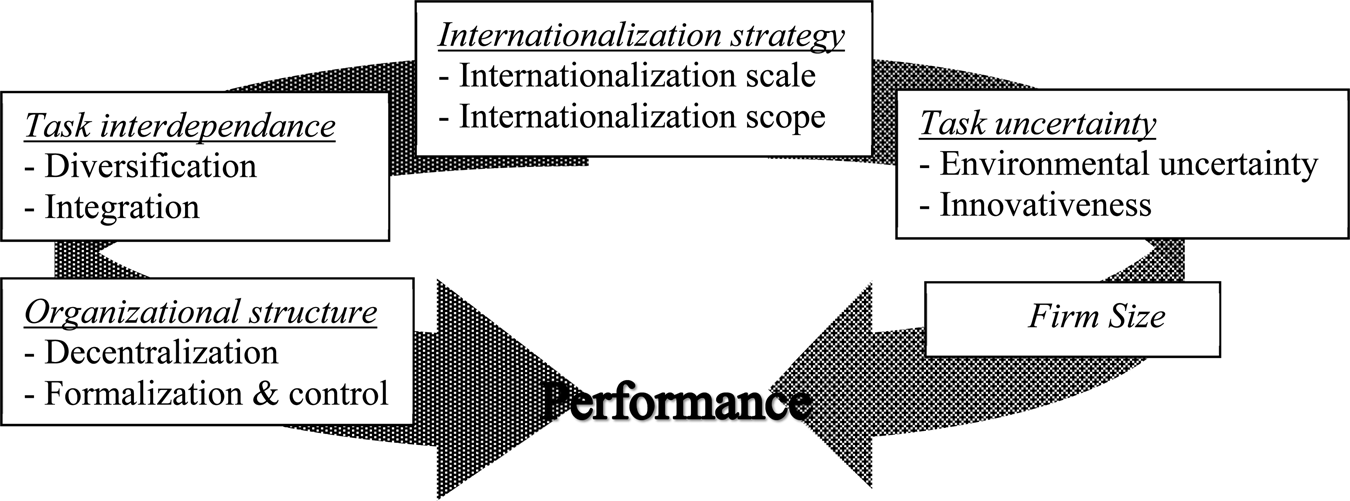

Operating in difficult institutional and economic conditions at home stimulate Russian firms to develop abilities to manage scarce resources under great uncertainty (Del Sol & Kogan, Reference Del Sol and Kogan2007). However, home-country institutional context influences Russian internationalized firms in a specific manner. Research suggests that even in private firms, state influence remains substantial (Kalotay & Sulstarova, Reference Kalotay and Sulstarova2010), leading to often blurry lines between business and government (UniCredit Aton Research, 2008). We consider the role of the state and policy change as an additional level of uncertainty for Russian firms. Furthermore, home-market economic instability and a shortage of technological, administrative, physical, or other resources may encourage Russian firms to diversify to reduce risks. Diversification requires financial control systems with decentralized responsibility and competition between departments (Hill & Hoskisson, Reference Hill and Hoskisson1987; Williamson, Reference Williamson1975), which is reflected in a high degree of formalization, low degree of centralization, low degree of internal horizontal integration, and knowledge sharing. Russian firms increasing their internationalization scope may face increasing coordination costs of managing export (foreign) operations, spreading managerial resources thinly across markets, and reduced abilities to support marketing programs abroad (Dikova et al., Reference Dikova, Jaklic, Burger and Kuncic2016). As task interdependence decreases because of diversification, specialization-formalization increases (e.g., creation of profit reporting systems), so does structural differentiation (e.g., the number of hierarchical levels) due to increased international scope. Figure 2 visually presents our conceptual model.

Figure 2. Conceptual model: Performance effects of a complex fit between internationalization, task uncertainty and interdependence, size and structure

On some occasions, management may correctly anticipate the need to adopt new structures to fit the new level of a given contingency; however, this is likely to be rare as it requires knowledge of subtle and complex fits (Donaldson, Reference Donaldson2001). Therefore, empirical testing should aim at establishing the various combinations (fits) between a given set of contingencies and structural variables that result in positive performance outcomes. In our empirical analysis, we follow the key argument of contingency theory that instead of looking for the best way of organizing Russian internationalized firms, it is better to analyze different situations and co-align the way of organization with the settings of the situation (Morton & Hu, Reference Morton and Hu2008). Our configurational approach presents a holistic picture considering relationships between elements of non-linear character (Meyer, Tsui, & Hinings, Reference Meyer, Tsui and Hinings1993).

METHODS

The fsQCA Analysis

Considering the complexity and non-linearity of the relationships between a firm's internationalization, task interdependency, task uncertainty, organizational size, and structure, we apply a fuzzy set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) as it is not limited by the shape of relationships and, thus, provides a promising way to examine these issues (Pajunen, Reference Pajunen2008). FsQCA is based on the sets theory, which allows conducting a detailed analysis of the role played by examined factors in achieving declared results. The basic statement of fsQCA is that a particular situation is best understood as a specific configuration of the signs (Fiss, Reference Fiss2011) because not all the factors are equally important or ‘strong’ in all situations. The configurational approach considers an organization as a complex system consisting of a set of interrelated elements interacting with various elements of their environment. Standard statistical methods often do not adequately address such complex interdependence. Unlike conventional linear methods considering an influence of individual independent variables on a dependent variable, fsQCA focuses on the ways of combining independent variables (configuration) to achieve the desired result (Fiss, Reference Fiss2011; Ragin, Reference Ragin2000). Thus, fsQCA combines the benefits of both qualitative and quantitative research methods (Pajunen, Reference Pajunen2008). In fsQCA ‘a case is described by the combination of “causal conditions” and the “outcome”’ (Schneider, Schulze-Bentrop, & Paunescu, Reference Schneider, Schulze-Bentrop and Paunescu2010). Through the specific algorithms, it transforms the specificity of each case into general patterns; thus, it reveals factors and relationships common for the whole sample, which makes wider formal generalization possible (Woodside, Reference Woodside2013).

A preliminary stage of fsQCA requires calibration of original data into fuzzy-sets. The choice of an external criterion, used to convert the original values to the degree of their belonging to the set, plays a crucial role in the calibration processes. An external criterion could be determined based on general knowledge, collective scientific knowledge, or a researcher's own accumulated experience obtained through the study of the problem. It should be formulated in an explicit form, applied systematically and transparently (Ragin, Reference Ragin2008). To calibrate the initial data on the basis of a chosen and theoretically grounded external criterion, the researcher sets at least three important threshold values for structuring a fuzzy set. These thresholds, or ‘qualitative anchors’, are important for distinction between relevant and irrelevant variation (Pajunen, Reference Pajunen2008). The first threshold determines the full membership of the element in the set, the second threshold determines the complete non-membership of the element to the set, and the third one is a crossover point, in which the element equally belongs and does not belong to the set. As both outcome and causal variables are calibrated and assigned with membership value, fsQCA ‘explores how the membership of cases in causal conditions is linked to the membership in the outcome’ (Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Schulze-Bentrop and Paunescu2010).

After completing the preliminary stage, transformed values can be used for basic analysis, which includes constructing a truth table and reducing the number of analyzed combinations. A truth table is a data matrix that includes all possible combinations of the independent variables. Each row of the table corresponds to a unique combination of variables, where the entire table presents a list of all possible combinations. The distribution of observations is not homogeneous, some combinations are quite common, some are rare, and others are not observed at all. As a result of the analysis and the transformation of the truth table, some lines are excluded from the analysis; these are combinations for which no observations were assigned. The remaining rows are analyzed in terms of the minimum number of observations for a particular combination and the minimum consistency value. In order to be considered as sufficient, a consistency value should exceed 0.75–0.80 (Fiss, Reference Fiss2011; Ragin, Reference Ragin2000).

To minimize the number of combinations to a manageable set, a counterfactual analysis of causal conditions should be applied. Counterfactual analysis is very important in the analysis of configurations because even a small number of configuration elements leads to a huge number of lines of the truth table. This procedure makes it possible to divide causal conditions into core and peripheral conditions, in other words, necessary and sufficient ones. This specificity of fsQCA brings about an additional benefit related to non-linearity and diversity. Some causal factors which are significant in one configuration might be insignificant or even have reverse relationships, in another configuration (Pajunen, Reference Pajunen2008). This is closer to reality, considering the joint effect of all causal factors on the outcome variable.

Data Collection

The data for the study were collected through a specifically developed survey. A specialized Russian analytical agency randomly selected and contacted 1500 firms either by an e-mail or phone and invited a firm representative to fill in the questionnaire. All the respondents took key managerial positions, such as a head of department or division; they were responsible for a functional area or certain market and possessed knowledge about their firm's internal processes, procedures, performance, market competitive position, and other relevant issues. In total, 875 filled questionnaires were received back, which resulted in a 55 percent response rate. Most contacted firms were operating solely domestically, and therefore the final sample accounted for 213 internationalized Russian firms. The international scale of the firms included in the final sample was quite diverse, with the average share of foreign (to total) sales at around 10 percent. These firms were active in a wide range of industries, among them 31 firms represent machinery and equipment industry, 50 firms operate in chemicals, rubber, and plastics industry, 14 firms – in metallurgy, 19 firms – in wood and timber industry, 4 – in oil and gas industry, 13 firms in transportation. All firms were either medium or large-sized with more than 100 employees: 81 firms could be characterized as medium-sized with more than 100 and less than 250 employees, and the rest 132 firms as large firms with more than 250 employees. The average number of employees for the entire sample was 827, and the average firm age was 36.5 years. The majority of firms (161 out 213) were reported as private, 44 firms as having partial state ownership, and only 8 firms were predominantly state-owned.

Measures

Most of the measures in this study were derived from questions allowing respondents to answer on a 7-point Likert scale. The outcome variable, organizational performance, was adapted from Khandwalla (Reference Khandwalla1977) and measured with a 7-point Likert scale where 1 denotes ‘significantly lower than average in the industry’ and 7 – ‘significantly higher than average in the industry’. Respondents were asked to evaluate their company's performance in comparison to the industry's average (above or below the industry's average) and/or to their main competitor. The items covered such aspects as their market share and sales growth, average return on investment, and average profit. The scale was successfully tested for its reliability (Cronbach's alpha is estimated at the level 0.845).

Predictors (causal factors) were divided into two categories: contingency factors and structural factors. Internationalization was captured by two variables, internationalization scale, and internationalization scope. To measure Internationalization scope, respondents were asked to assess to what extent they agree with the statement that their firm operates in many foreign countries. A 7-point Likert scale was used to measure the variable where ‘1’ denoted strongly disagree and ‘7’, strongly agree with the statement. The international scope variable aims to capture the level of diversity of a firm's international business environment, as the more diverse environment would add more complexity to the decision-making process. Thus, instead of using an objective measure (e.g., the number of markets where the firm operates), we apply a subjective measure of international scope as it reflects the perceived magnitude (operational burden) and complexity in serving these markets. Internationalization scale variable was measured as a share of revenue obtained from foreign markets to the firm's total revenue (Banalieva & Sarathy, Reference Banalieva and Sarathy2011; Geringer, Tallman, & Olsen, Reference Geringer, Tallman and Olsen2000). Size was measured by the number of employees permanently working in the firm.

Task interdependence was captured by diversification and integration. To measure Diversification, respondents were asked to evaluate what percentage of the firm's revenue was obtained from a major product category. Due to the specific formulation of this question, the values for this variable were calculated as 100 percent minus values provided by the respondents. Internal horizontal integration was measured with Miller and Droege's scale (Miller & Droege, Reference Miller and Droege1986) and had Cronbach's alpha of 0.703.

Task uncertainty is a complex construct captured by the firm's ability to innovate and the level of environmental uncertainty. Firstly, Innovativeness was measured using adapted scales developed by Covin & Slevin (Reference Covin and Slevin1989) oriented at measuring the firm's capabilities for introduction and commercialization of new products and processes (Cronbach's alpha 0.812). Secondly, Environmental uncertainty variable was measured with an adapted Miller and Droege's scale (Reference Miller and Droege1986) consisting of 6-items (Cronbach's alpha 0.677). The questions addressed aspects such as demand predictability, the frequency of changes in production- and supply-chain processes, the frequency with which new products get introduced to the market, the costs of product obsolescence, etc.

In the second category, our structural factors include centralization and formalization. Centralization was measured with adapted Pugh and Hickson's scale (Pugh & Hickson, Reference Pugh and Hickson1976). The scale included 12 questions on the hierarchical level involved in making certain managerial decisions. The test on centralization scale reliability showed a very high result with Cronbach's alpha 0.943. Formalization and control variable was measured with Khandwalla's scale (Khandwalla, Reference Khandwalla1977) of 5 items (Cronbach's alpha 0.885).

Calibration of Outcome Variable and Causal Conditions

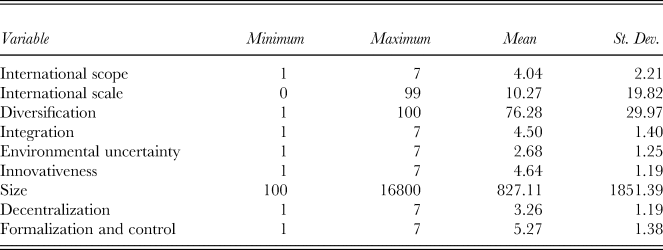

The descriptive statistics for our sample are presented in Table 1. Following Pappas, Kourouthanassis, Giannakos, and Chrissikopoulos (Reference Pappas, Kourouthanassis, Giannakos and Chrissikopoulos2016), we set up 3 similar thresholds for fuzzy membership scores for all Likert-scale variables where 6 is a threshold for full membership in the set, 2 is a threshold for full non-membership of the set, and 4 is a crossover point for neither in nor out. These thresholds are logical due to the nature of the Likert scale measures. For the variables international scale, size, and diversification, which were measured on traditional interval scale, the thresholds were set up on the basis of theoretical logic and prior knowledge. Thus, international scale variable obtained the values of 50, 5, and 10 corresponding to highly internationalized firms with foreign sales more than 50% of total sales, low internationalized firms with foreign sales less than 5%, and moderately internationalized firms with about 10% which also represents the mean value for the whole sample. The thresholds for size variables were chosen based on the commonly accepted distinction between medium and large firms and the mean value for our sample. Thus, we assigned 1000 as an upper threshold, so firms with a number of employees more than 1000 were treated like very large firms; 250 as a lower threshold were set up to differentiate the firms that are traditionally treated as medium-sized (those not belonging to the large ones); and, finally, crossover point was estimated at 500 meaning that firms which have around 500 employees working on a permanent basis could be treated neither as medium-sized nor as very large ones. Finally, for diversification, we set the thresholds for fully in the set at 75%, for fully out of the set at 25%, and the crossover point is derived by averaging the upper and lower thresholds. Fs/QCA 2.5 software was used to conduct the analysis.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

RESULTS

Following Ragin's (Reference Ragin2008) recommendations for a higher cutoff point for large-scale samples (e.g., 150 and more cases), we set up a frequency cutoff of 2 and a consistency cutoff of 0.80. As a result, we identified 2 core conditions that formed a ‘parsimonious’ solution. This means that to obtain high organizational performance a firm had to fulfill at least one of these ‘necessary’ conditions, namely high integration (raw coverage 0.70, unique coverage 0.11, consistency 0.97) and/or low diversification (raw coverage 0.84, unique coverage 0.24, consistency 0.87). The overall solution coverage was 0.94, and solution consistency was 0.87. The results obtained from the parsimonious solution indicated that Russian firms performed better if they were focused (active in one product/activity), rather than diversified. This goes against previous research that views a diversification strategy as a way to obtain high performance, especially in an uncertain environment. The second core condition accounted for the structural settings of high performing Russian firms and indicated the relevance of (internal) integration mechanisms. Both of these conditions are indicators of task interdependence (Donaldson, Reference Donaldson2001), which allows us to state that high interdependence is a determining condition of high organizational performance of Russian firms.

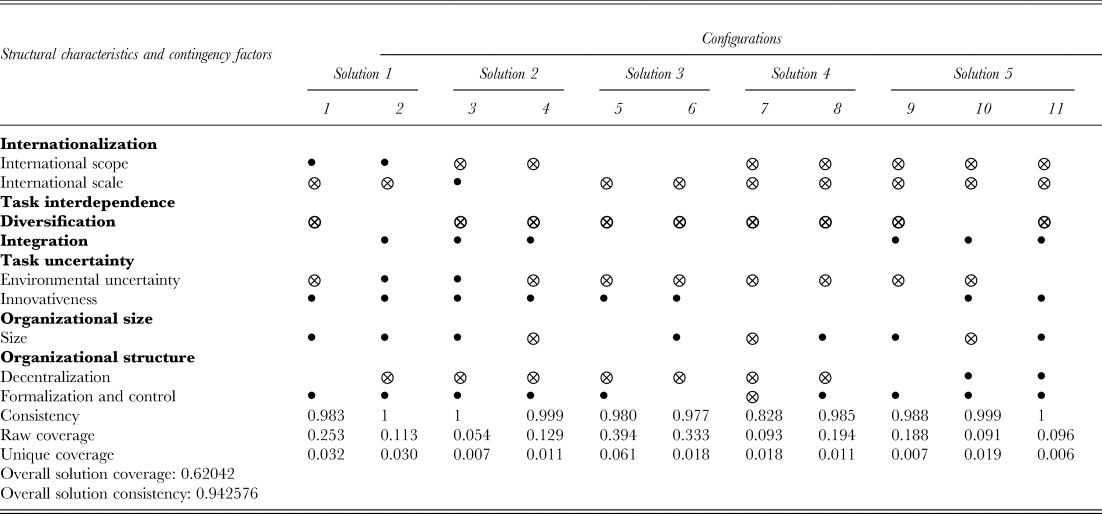

At the next step, a so-called ‘intermediate’ solution was retrieved, which provided sufficient conditions for high performing firms (Table 2). The ‘intermediate’ solution provided 11 configurations of the independent variables’ values. The intermediate solution presents the major benefit of the QCA; namely, it enables researchers to capture all three aspects of causal complexity: conjunction, equifinality, and causal asymmetry (Misangyi et al., Reference Misangyi, Greckhamer, Furnari, Fiss, Crilly and Aguilera2017). Equifinality means that different configurations of causal (core and peripheral) conditions (paths) can lead to the same outcome (Fainshmidt, Witt, Aguilera, & Verbeke, Reference Fainshmidt, Witt, Aguilera and Verbeke2020). In our study, these configurations form sufficient conditions to achieve high organizational performance. Specifically, configuration 1 shows that the best performing Russian internationalized firms have a relatively high international scope but sell a rather small volume of goods in these markets (international scale is an absent peripheral condition), are not diversified, are very innovative, their environmental uncertainty is not an issue (i.e., a lack of peripheral condition), are relatively large, may or may not be decentralized, and are highly formalized. In configuration 2, the best performing Russian internationalized firms have a relatively high international scope, sell a rather small volume of goods in these markets, are very integrated but may or may not be diversified, face more environmental uncertainty, are innovative and relatively large, are centralized, and have substantial formalization. In configuration 3, the best performing internationalized Russian firms sell a substantial volume of goods (services) abroad but in fewer foreign countries (i.e., scope is an absent peripheral condition), are not diversified and are very integrated, are innovative and operate under elevated environmental uncertainty, are relatively large and centralized, with substantial formalization.

Table 2. Outcome of fsQCA analysis of organizational performance determinants

Notes: «•» - presence of core condition, «⊗» - lack of core condition; «•» - presence of peripheral condition, «⊗» - lack of peripheral condition

Some of the configurations are similar to each other, with only slight differences in one or a couple of elements, which prompted us to group them. Thus, configurations 1 and 2 were combined together and formed Solution 1. Configurations 3 and 4 were grouped together in Solution 2, configurations 5 and 6 were combined in Solution 3, configurations 7 and 8 were combined in Solution 4, and finally, configurations 9 to 11 formed Solution 5. Considering these solutions separately, we identified generic profiles of Russian internationalized firms successfully operating in different settings. We use these configurations to formulate propositions for future research.

Solution 1 corresponds to well-performing Russian firms that have pursued international scope at the expense of international scale. This solution is mostly applicable to large and innovative companies, with established formalization and control mechanisms and an emphasis on horizontal integration and centralization. In general, this solution assumes the fit between high task interdependence, moderate task uncertainty, relatively high internationalization (scope), and centralized, usually formalized organizational structures.

Solution 2 corresponds to well-performing internationalized Russian firms that have pursued international scale at the expense of international scope. They implemented a high level of formalization, centralization, and control as structural settings at the presence (and absence) of several peripheral conditions (contingencies). The configurations within this solution provide options for innovative, not-diversified (focused) firms of different sizes with high horizontal integration. Similar to the previous group of firms, this group features high task interdependence, diverse task uncertainty, and the possibility for the pursuit of international scale (at the expense of scope), which, in turn, is matched by specific structural solutions: high formalization, control, and centralization.

Solution 3 corresponds to well-performing Russian firms that have a high level of formalization and control as structural solutions, at the presence (and absence) of one core condition and several peripheral conditions. The critical absent condition is diversification, and the key peripheral conditions are innovativeness and an absence of environmental uncertainty and international scale. This solution is applicable to firms of different sizes that may (or may not) pursue high international scope at the expense of international scale. This solution assumes the fit between moderate task interdependence, moderate task uncertainty, and centralized organizational structures.

Solution 4 is mostly applied to early internationalizing firms or to firms with low international presence (both international scale and scope appear as absent peripheral conditions). This solution indicates that even less internationalized Russian firms have an opportunity to reach high organizational performance if other conditions are met. For example, these firms are not diversified, can be of different sizes, may or may not be innovative, and do not have to deal with environmental uncertainty. For smaller firms, the structural choices are lack of formalization and control but high centralization, while for larger firms, these are high level of formalization, centralization, and control. This solution assumes the fit between moderate task interdependence, low task uncertainty, and centralized organizational structures.

Solution 5 is typical for successful Russian firms, mostly large and rather innovative but not very internationalized (both international scale and scope appear as absent peripheral conditions). They operate mostly under low external environmental uncertainty. Structurally, they employ highly decentralized decision-making and formalized processes and procedures, supplemented by a high level of integration. According to this solution, high task interdependence fits moderate task uncertainty and decentralized and formalized organizational structures.

Robustness Check

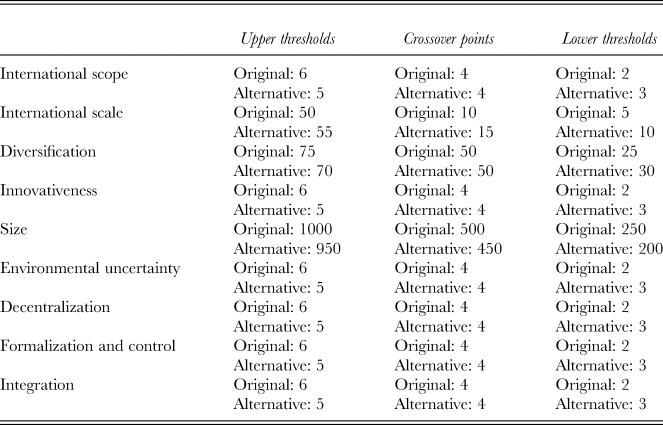

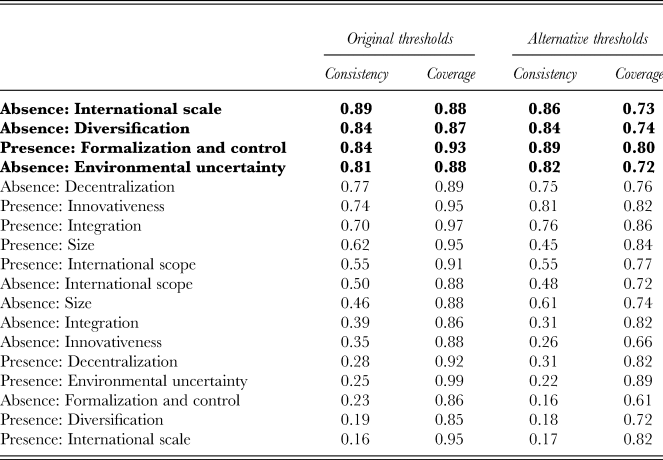

To check the robustness of the fsQCA results, we follow Skaaning (2011) and test our solutions for sensitivity by addressing the issues of calibration thresholds, minimum frequency, and consistency levels. Firstly, new calibration thresholds were set up for both outcome variable and causal factors. The alternative thresholds assigned values near the original ones, so that the same theoretical justifications could be applied for new and original anchors (Skaaning, Reference Skaaning2011). The original and alternative values are presented in Table 3. The comparison of the necessary conditions’ analysis for the original and the alternative values of thresholds showed high consistency, i.e., most of the causals factors that obtained high values of consistency in the analyses were the same (Table 4).

Table 3. Values used for calibration into set membership scores

Table 4. Analysis of necessary conditions for original and alternative thresholds values

Furthermore, we increased the minimum consistency level up to 0.90, fixing the original calibration thresholds and the minimum number of cases. The parsimonious solution included a high level of integration and low diversification as necessary conditions for a high firm's performance. Most of the conditions are identical or very similar to the baseline settings, which allowed us to ascertain the reliability of the analysis and results.

To test the robustness of our results, we additionally reran an analysis with industry and ownership variables. For state-ownership, the thresholds were assigned as follows: 0% for full non-membership, 10% for the сross-over point, and 50% for the upper threshold, which defines a border value for full membership. As industry variable has just two values, 0 and 1, the lower threshold was set at 0, the upper threshold at 1, and the crossover point got the value of 0.5. Both variables were found to be irrelevant for all configurations; hence, they were not included in the final analysis presented in Table 2.

DISCUSSION

In this article, we studied performance implications of a multidimensional fit between internationalization, diversification, integration, innovativeness, environmental uncertainty, organizational size, and structure (formalization, decentralization, and hierarchical control). We extended the classic contingency model (Donaldson, Reference Donaldson2001) by adding internationalization (scale and scope) as a new critical contingency in addition to task interdependence, task uncertainty, and size. We tested our model on a sample of Russian internationalized firms, which represent relatively low internationalized firms originating from an unfavorable institutional context. We chose this specific sample of EM firms, because arguably firms originating from a home country marked by severe deficiencies in environmental munificence, are likely to be limited when they start to internationalize (Estrin, Meyer, & Pelletier, Reference Estrin, Meyer and Pelletier2018; Luo & Wang, Reference Luo and Wang2012; Meyer & Thaijongrak, Reference Meyer and Thaijongrak2013; Ramamurti, Reference Ramamurti2012). Institutional constraints at home and numerous challenges Russian firms encounter abroad due to their liability of origins (among others) create an opportunity for research that can detect unique performance effects associated with internationalization, not present under a different set of circumstances.

To achieve our overall goal, we applied a fuzzy set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA). This methodology allowed us to conduct a detailed analysis of the specific role played by all examined contingency and structural factors towards the ultimate goal of (excellent) organizational performance. The basic assumption of this method is that a specific phenomenon is best understood as a certain configuration of characteristics (Fiss, Reference Fiss2011). FsQCA carries on the benefits of both quantitative and qualitative research, as it considers diversity and specificity of each case and reveals patterns common for the whole data array (Woodside, Reference Woodside2013). The fsQCA explicitly allows for equifinality of different combinations of causal conditions (Fainshmidt et al., Reference Fainshmidt, Witt, Aguilera and Verbeke2020), which means that more than one combination of causal conditions may be found to be linked to the same outcome (Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Schulze-Bentrop and Paunescu2010). We reported several general configurations, which we will use to derive propositions for future research on the link between internationalization and performance.

Our results point to several interesting observations. In all solutions corresponding to high performance, diversification appeared as an absent core condition. Furthermore, as shown in solutions 1 and 2, internationalization was either in favor of scope (i.e., geographic diversification) or scale (i.e., volume of products or services sold abroad). A number of studies (Hitt, Hoskisson, & Kim, Reference Hitt, Hoskisson and Kim1997; Lu & Beamish, Reference Lu and Beamish2004) have examined issues related to complex internationalization (i.e., geographic and product diversification), and have argued that firms can profitably engage in such activities when they possess a particular set of advantages (Delios & Beamish, Reference Delios and Beamish1999). Perhaps our findings are not counter-intuitive. A key feature of Russian business is the personalized nature of many Russian companies. Most large companies have a very narrow scope, and often the fate of the company depends on the fate of the man at the top (Wenger, Petrovic, & Orttung, Reference Wenger, Petrovic and Orttung2006). Perhaps product diversification is simply not a strategic goal for most Russian firms, with the exception of very few. Moreover, the sample of Russian internationalized firms we studied may perhaps lack unique competitive advantages to pursue aggressive internationalization scale and scope simultaneously. We, however, postulate that the internationalization we observe in the case of well-performing Russian firms can only be explained in combination with the remaining contingencies and structural choices, rather than in isolation. Next, we focus on some of the prominent conditions that would inform our propositions for future research.

Diversification is typically examined in relation to firms’ innovative capabilities (Cohen & Klepper, Reference Cohen and Klepper1992). Past research shows that firms selling only one category of products are less likely to engage in R&D than those selling a broader range of products (Piga & Vivarelli, Reference Piga and Vivarelli2004). This logic does not necessarily apply to our set of Russian (focused) firms as innovativeness is a peripheral condition in four of our five solutions. Finally, a challenge facing corporate diversification stems from ‘managing the conflict between the new and old (business activities) and overcoming the inevitable tensions that such conflict produces for management’ (Dess et al., Reference Dess, Ireland, Zahara, Floyd, Janney and Lane2003: 358). We believe the lack of product diversification in the case of well-performing Russian firms is likely linked to the structural solutions for managing a single-product firm, but not necessarily linked to innovation. Innovativeness is particularly important for internationalized Russian-firms’ competitive advantage, as it leads to higher perceived quality and market recognition, but is also a way of overcoming both liabilities of foreignness and liabilities related to the country of origin. Russian innovative firms would perhaps develop a more sustainable, international source of competitive advantage (Porter, Reference Porter1980) as such strategy relies on product customization, which involves developing and sustaining close relationships with diverse foreign customers. These close relationships build the ‘reputation,’ which in turn generates customer loyalty abroad (Treacy & Wiersema, Reference Treacy and Wiersema1993).

According to the literature, task uncertainty associated with innovation is caused by the complexity and diversity of the tasks performed, which often creates confusion (Hartmann, Reference Hartmann2005). Environmental uncertainty, on the other hand, is what firms face as a result of unpredictability in the actions of the customers, suppliers, competitors, and regulatory groups that are external to the organization but certainly produce or cause conditions that affect the organization and its future (Govindarajan, Reference Govindarajan1984). Information sharing within the organization is key in both types of uncertainty, which explains why integration is a core condition in three of the five solutions of our analysis. An interesting observation is that environmental uncertainty appears as an absent peripheral condition in three of the solutions. This suggests that many Russian internationalizing firms do not necessarily thrive in uncertainty abroad, despite the fact that home conditions likely prompt Russian firms to develop abilities to manage scarce resources under great uncertainty (Del Sol & Kogan, Reference Del Sol and Kogan2007). However, in order to fully understand the performance implications of our set of contingencies, we need to include the structural solutions implemented by the examined Russian firms.

In the past, research linking uncertainty and structural characteristics provided controversial results. Some suggest that in uncertain environments, flexible, adaptive, organic structures are more suitable (Minzberg, Reference Mintzberg1979) because, with the increase in uncertainty, administrative tasks become less routine and more complex, which requires a low level of formalization of procedures (Lin & Germain, Reference Lin and Germain2003). Others note that to remain competitive in a dynamic environment, formalized planning, coordination, and performance control is required (Tung, Reference Tung1979). If operating in dynamic environments requires a higher degree of integration, this will considerably increase the costs of coordination, and in turn, affect the costs of hierarchical management (Hill & Hoskisson, Reference Hill and Hoskisson1987; Jones & Hill, Reference Jones and Hill1988). Moreover, the benefits of vertical integration in uncertain environments can also become less pronounced, if a management's response to uncertainty is manifested in the decentralization of decision-making, as well as the decrease in information exchange between departments (Aleksander, Reference Aleksander1991).

In the case of Russian internationalized firms, we observe a preference for centralized, highly formalized, and tightly controlled organizational structures (in four of the five solutions). Only for the least internationalized Russian firms (Solution 5), the organizational structure appears decentralized yet formalized and controlled. A study by Paswan, Dant, and Lumpkin (Reference Paswan, Dant and Lumpkin1998) shows that in uncertain environments, firms become more cautious about resource-management and, therefore, increase control over their operations through centralization of decision-making, decreasing involvement of lower hierarchical levels and reducing formalization. What we observe in our sample echoes these findings with the exception of formalization, which appears as a peripheral condition. We argued this is indirectly caused by new administrative changes required by the internationalization. Russian internationalized firms opt for centralization and control as a way of managing scarce resources, innovation as a means of creating a competitive advantage abroad, and formalization as a means of reducing the complexities of internationalization. According to Donaldson (Reference Donaldson2001), an increase in the number of levels in the organizational hierarchy impedes the flow of information to the upper levels of the organization, thus, rendering centralization less effective. However, we find that performance of Russian internationalized and innovative firms under moderate environmental uncertainty is positively affected by specialization, formalization, integration, and centralization.

We summarize these findings in the following proposition:

Proposition 1: Russian focused, integrated, and innovative firms pursuing internationalization under low uncertainty will perform well if they are decentralized, formalized, and tightly controlled.

When entering foreign markets, Russian firms are likely to face a multitude of factors adding to the costs of operating abroad and, as a result, not have performance benefits, especially if a number of numerous foreign markets are simultaneously served. Hence, the question we answer here is what configuration of task interdependence, task uncertainty, size, and structure is associated with good performance for internationalized Russian firms. Well-performing internationalized Russian firms, focused on internationalization by scope, active in multiple foreign locations, are rather large (solution 1), not diversified but quite innovative and centralized, formalized and favoring tight organizational control (solution 2 is more relaxed about firm size as it is not limited to large firms only). Our results are also indicative of the typical managerial practices in most large Russian firms, namely strong centralization of decision-making despite the likely increase of hierarchical levels in the process of internationalization. These findings do not indicate a misfit between discussed contingencies and the preference for mechanistic organizational structures, likely due to the relatively low level of internationalization of these Russian firms. Perhaps flexible organizational structures may be more suitable for Russian firms pursuing a more aggressive internationalization. However, because of the specific set of contingencies and structural choices, the pursuit of either scale or scope (but not both) results in a positive performance outcome (solutions 1 and 2).

We summarize these findings in the following proposition:

Proposition 2: Russian focused, integrated, and innovative firms operating under uncertainty in a centralized, formalized, and tightly controlled structures will perform well if they pursue (high) internationalization either via scope or scale.

It is also important to discuss solutions 3, 4, and 5, where internationalization is not a critical condition for the above-average performance of Russian international firms. In solution 5, integration is a present core condition, and in the other two solutions, it was neither a condition nor a lack of it. Earlier, we noted that task interdependence indicates whether the activities of a firm are closely connected or not in the horizontal and vertical organizational dimensions. In the case of innovative, not-diversified (focused) internationalized Russian firms, results indicate interdependence among the functional departments, likely because of a necessary interaction between the research and other strategic contingencies (Donaldson, Reference Donaldson2001). We find that performance of Russian large (or medium) innovative firms under low uncertainty (solutions 3, 4, and 5) is positively affected by a fit between specialization, formalization, integration, and centralization, irrespective of substantial internationalization (in solutions 3, 4, and 5 both internationalization scope and scale were not present as a condition). We summarize these findings in the following proposition:

Proposition 3: Russian focused, integrated, and innovative firms of small or large size operating under low uncertainty will perform well if they are decentralized, formalized, and tightly controlled irrespective of their level of internationalization.

Naturally, our study is not without limitations. Quite a few relate to our dataset. Our sample is small and specific, with information about 213 Russian firms and based on single-respondent surveys capturing perception-measures of performance. Moreover, the data reflect an uneven cross-section, with measures of Russian firms that internationalized at different dates, mostly at the time of turbulent domestic transition. Future research is needed to explore the generalizability of our findings. We cannot exclude issues of critical importance, such as key-informant, retrospective, and sampling biases that might affect our findings. However, we are confident that our results offer a solid steppingstone for further work in the configurational tradition. Moreover, although we strongly believe in the novel method applied here, methodological triangulation is required.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we believe the main contribution of our study is the definitive support for the notion that instead of looking for the best way of organizing international firms, it is better to analyze different contingencies and co-align the structure and organization of the firm in response to these contingencies. This is particularly relevant for internationalizing Russian firms as they face conflicting demands from diverse stakeholders, are often constrained by various liabilities, and do not necessarily follow the internationalization path of developed-market firms. Positive performance outcomes can be uncovered by establishing various combinations (fits) between a comprehensive set of contingencies and structural variables (equifinality). Thus, an important practical implication of our results is related to the possibility of performing diagnostics on the current state of firms on specified causal factors, choosing the most relevant configuration in terms of better fit on most causal factors, and further aligning the factors that do not fit the chosen configuration to achieve high organizational performance. We hope our configurational approach is valuable enough to warrant further attention, with studies exploring different datasets and applying alternative methods.