INTRODUCTION

Multinational enterprises (MNEs) are often viewed as networks with dispersed foreign subsidiaries that serve as key actors (Buckley, Reference Buckley2009; Dellestrand & Kappen, Reference Dellestrand and Kappen2012; Ghoshal & Bartlett, Reference Ghoshal and Bartlett1990; Nohria & Ghoshal, Reference Nohria and Ghoshal1997). As such, it is often assumed that sister subsidiaries may cooperate with each other by sharing information to enhance their respective performance due to the norms of reciprocity and mutuality (Andersson, Forsgren, & Holm, Reference Andersson, Forsgren and Holm2002; Novicevic & Harvey, Reference Novicevic and Harvey2004). However, scholars also suggest that sister subsidiaries compete for external resources in the market (Fauli-Oller & Giralt, Reference Fauli-Oller and Giralt1995; Kalnins, Reference Kalnins2004; Phelps & Fuller, Reference Phelps and Fuller2000) and internal resources from the headquarters (Ambos & Birkinshaw, Reference Ambos and Birkinshaw2010; Birkinshaw & Fry, Reference Birkinshaw and Fry1998; Birkinshaw, Hood, & Young, Reference Birkinshaw, Hood and Young2005).

Given both cooperation and competition inherent in an MNE network, previous studies present a dilemma in predicting the performance of sister subsidiaries in a host country. On the one hand, sister subsidiaries may cooperate by bringing together different knowledge and experience from their practices and relationships with various local stakeholders to address unresolved problems in the host country, leading to better subsidiary performance. On the other hand, subsidiaries may also compete against one another when they depend on the same host market for resources and survival, lowering their profitability. This dilemma leads to the research question: How do MNE networks affect the performance of sister subsidiaries in a given host country?

To address the question, we draw on the coopetition perspective (Brandenburger, Nalebuff, & Brandenberger, Reference Brandenburger, Nalebuff and Brandenberger1996), which suggests that both cooperation and competition, known as ‘coopetition’, can arise within a multiunit organization (Fauli-Oller & Giralt, Reference Fauli-Oller and Giralt1995; Tsai, Reference Tsai2002) with a number of sister subsidiaries (Luo, Reference Luo2004, Reference Luo2005; Phelps & Fuller, Reference Phelps and Fuller2000). The number of subsidiaries within an MNE in a host country has been viewed as a construct of a subsidiary network because of their spatial proximity (Chung, Lu, & Beamish, Reference Chung, Lu and Beamish2008; Dhanaraj & Beamish, Reference Dhanaraj and Beamish2009), whereby sister subsidiaries are able to share host-country experience (Delios & Beamish, Reference Delios and Beamish2001; Gaur & Lu, Reference Gaur and Lu2007; Miller & Eden, Reference Miller and Eden2006). Our study extends existing studies by differentiating between product-similar subsidiaries and product-different subsidiaries in an MNE's country-specific subsidiary network.

We argue that the two types of subsidiaries have distinct implications for subsidiary performance, which may provide insights into the aforementioned dilemma. Specifically, the product-similar subsidiary network, which is defined as the total number of an MNE's subsidiaries in the same industry and host country, will have a curvilinear effect on subsidiary performance. On the one hand, they are embedded in the MNE network for collaborative advantages. On the other hand, they compete in the same host country for a larger market space. We propose an inverted U-shaped effect of product-similar subsidiaries on subsidiary performance. In contrast, the product-different subsidiary network, which is defined as the total number of subsidiaries in different industries but in the same host country, will have a monotonic (positive) effect on subsidiary performance, because these subsidiaries are more likely to collaborate while avoiding direct market competition.

For a more thorough understanding of the relationship between subsidiary network and performance, we introduce two moderators, namely, host-country economic advantage (Miller, Thomas, Eden, & Hitt, Reference Miller, Thomas, Eden and Hitt2008) and subsidiaries’ intangible resource (Delios & Beamish, Reference Delios and Beamish2001), which may alter the relationship. The two constructs are highly relevant to our research topic. Specifically, the resource advantage of MNEs from more developed countries enables them to outperform local competitors in less developed countries. Thus, their subsidiaries are less likely to cooperate. In contrast, MNEs from less developed countries have resource disadvantages in more developed countries. Thus, their subsidiaries are more likely to cooperate. Moreover, intangible-intensive subsidiaries are less likely to be affected by inter-subsidiary coopetition because their own competence. As we argue below, host-country economic advantage and subsidiary intangible resource will alter the proposed relationship between subsidiary network and performance. Our argument is largely supported based on a sample of foreign subsidiaries in European countries.

This study presents two main contributions to the coopetition research. First, subsidiary performance, as an interesting phenomenon, has received increasing attention in the strategy and international business literatures (Andersson et al., Reference Andersson, Forsgren and Holm2002; Delios & Beamish, Reference Delios and Beamish2001; Fey & Björkman, Reference Fey and Björkman2001; Miller & Eden, Reference Miller and Eden2006; Venaik, Midgley, & Devinney, Reference Venaik, Midgley and Devinney2005). Although these studies advanced our knowledge on identifying antecedents of subsidiary performance, we know little about how different types of inter-subsidiary relationships affect subsidiary performance. Our study fills this research gap by providing a theoretical framework to explain the optimal number and composition of subsidiaries in a given host-country network that may allow the subsidiaries to effectively manage their coopetitive relationships toward higher levels of performance. Specifically, we differentiate between a product-similar subsidiary network and a product-different subsidiary network in a host country from the coopetition perspective (Brandenburger et al., Reference Brandenburger, Nalebuff and Brandenberger1996; Lado, Boyd, & Hanlon, Reference Lado, Boyd and Hanlon1997) to contrast their distinct performance implications.

Second, our study enriches the coopetition perspective by introducing host-country economic advantage and subsidiary intangible resource as moderators to explore the boundary conditions of the theoretical perspective. In our view, different coopetitive relationships are likely to change when external and internal conditions vary, which may enhance or damage a subsidiary's competitiveness in the host country. Thus, specifying the conditions of coopetitive relationships among subsidiaries within an MNE and identifying the theoretical mechanisms (i.e., different combinations and interactions of cooperation and competition) (Bengtsson & Kock, Reference Bengtsson and Kock2000; Chin, Chan, & Lam, Reference Chin, Chan and Lam2008) are crucial to the investigation of the influence of networks on subsidiary performance.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Economic actors are embedded in a wider social network (Granovetter, Reference Granovetter1985). Scholars have theoretically discussed coopetition as a phenomenon from network theory (Gnyawali, He, & Madhavan, Reference Gnyawali, He and Madhavan2006; Gnyawali & Madhavan, Reference Gnyawali and Madhavan2001). The coopetition perspective connects competing approaches to explain the relationships between network actors and their performance. On the one hand, cooperation through networks allows actors to achieve collaborative advantages by sharing information and coordinating actions. On the other hand, competition often also exists among network actors in many aspects (Lado et al., Reference Lado, Boyd and Hanlon1997; Tsai, Reference Tsai2002). An MNE can be viewed as a social network where subsidiaries are embedded and perform important roles (Ghoshal & Bartlett, Reference Ghoshal and Bartlett1990; O'Donnell, Reference O'Donnell2000). Sister subsidiaries within the same MNE system are often connected through operational coordination or routinized communication (Chung, Lee, Beamish, & Isobe, Reference Chung, Lee, Beamish and Isobe2010; Forsgren, Holm, & Johanson, Reference Forsgren, Holm and Johanson2005; Kim, Lu, & Rhee, Reference Kim, Lu and Rhee2012). In our study, coopetition refers to the concomitant presence of competition and cooperation in the subsidiary networks. We argue that network coopetition may have important impacts on subsidiary performance.

A Coopetition Perspective of Subsidiary Networks

Given that coopetition captures the notion of ‘duality in every relationship’ (Brandenburger & Nalebuff, Reference Florida1996: 39), we may not be able to simply separate inter-subsidiary cooperation from inter-subsidiary competition (Bengtsson & Kock, Reference Bengtsson and Kock2000). Our study expands the application scope of the coopetition perspective to specify inter-subsidiary competition among product-similar subsidiaries and inter-subsidiary cooperation among product-different subsidiaries to contrast their performance implications. In general, as the number of subsidiaries increases, regardless of whether these subsidiaries are product-similar or product-different, they will compete for resources and support from their headquarters (Ambos & Birkinshaw, Reference Ambos and Birkinshaw2010). In our study, the distinction of product-similar or product-different subsidiaries is their external or market competition. As the number of product-different subsidiaries increases, their internal competition increases. For comparison, as the number of product-similar subsidiaries increases, both internal and external competition of these subsidiaries increases. As such, the two types of subsidiaries may have different influence on their performance.

Inter-subsidiary cooperation

MNE networks provide a platform for subsidiary cooperation, and subsidiaries may benefit from the MNE networks in various ways. First, country-specific networks provide opportunities to share experiences in the host country and accelerate knowledge transfer across subsidiaries. Different subsidiaries have different business relations with host-country stakeholders (e.g., customers and suppliers). Through embedded networks, subsidiaries can access knowledge, ideas, and opportunities, as well as benefit from different types of spillovers and exchanges of information and skills (Andersson et al., Reference Andersson, Forsgren and Holm2002; Ciabuschi, Dellestrand, & Martín, Reference Ciabuschi, Dellestrand and Martín2011).

Moreover, MNE networks generate collaborative advantages by facilitating the effective use of organizational resources and facilities in the host country to enhance their efficiencies. Additionally, MNE networks allow subsidiaries to coordinate their actions against local competition in a host country. Researchers argue that MNEs may operate a number of subsidiaries in the same host country to sustain their competitiveness through the expansion of their market domains for greater economies of scale or through the preemption of the entry of rivals (Chang, Reference Chang2012; Song, Reference Song2002). Subsidiary density may also indicate the appeal of a host country (Demirbag, Tatoglu, & Glaister, Reference Demirbag, Tatoglu and Glaister2010; Miller & Eden, Reference Miller and Eden2006). Finally, as the hub of subsidiary networks, headquarters coordinate network activities and allocate resources by bridging the competence gap between dispersed subsidiaries to enhance the competitive edge of the entire MNE (Dellestrand & Kappen, Reference Dellestrand and Kappen2012).

Inter-subsidiary competition

A firm's subsidiaries may not only cooperate to gain the benefit of pooling resources, but also compete with each other for market share (Brandenburger et al., Reference Brandenburger, Nalebuff and Brandenberger1996). In reality, a firm's subsidiaries ‘often meet and even compete in multiple geographical and product markets’ (Kalnins, Reference Kalnins2004: 117). Inter-subsidiary competition in the same market has been observed within an MNE (Luo, Reference Luo2004; Prajogo & Sohal, Reference Prajogo and Sohal2004); such phenomenon is known as ‘intracorporate competition’ (Phelps & Fuller, Reference Phelps and Fuller2000). Inter-subsidiary competition can be induced by the headquarters of firms to prevent unwanted subsidiary coalitions against the initiatives of the headquarters (Kalnins, Reference Kalnins2004), foster the effective and efficient use of organizational resources (Phelps & Fuller, Reference Phelps and Fuller2000), or lower market entry of external competitors (Fauli-Oller & Giralt, Reference Fauli-Oller and Giralt1995).

Indeed, competing subsidiaries within an MNE may pool their resources to extend their economic reach or strengthen their presence in the host market. These subsidiaries may obtain a competitive edge that none of them can achieve individually. However, competition may also provide disincentives for cooperation. The critical issue specifically focused in our study is that foreign subsidiaries pursuing their own economic interests may reduce the overall profit of the subsidiary network in a given host country.

A Coopetitive Approach of Subsidiary Performance

We argue that different mechanisms can be used to explain subsidiary performance by applying the differentiated coopetitive configurations. In this study, we focus on the number of subsidiaries of an MNE in a host country, which has been viewed as a construct of subsidiary network (Chung et al., Reference Chung, Lu and Beamish2008). This variable has also been conceptualized as the ‘network size’ in a host country (Chung et al., Reference Chung, Lee, Beamish and Isobe2010), to capture the coopetitive relationship among MNE subsidiaries. As a point of departure from existing studies, our study differentiates between a product-similar network and a product-different network of subsidiaries in a given host country. For product-similar subsidiaries, the central question is how to grow the market pie and how to share the market pie (Brandenburger et al., Reference Brandenburger, Nalebuff and Brandenberger1996). However, direct market competition may not exist among product-different subsidiaries. We argue that the two types of networks variably affect subsidiary performance, which allows us to advance the coopetition perspective.

Specifically, MNE networks allow participants to leverage their linkages to create a collaborative advantage (Lado et al., Reference Lado, Boyd and Hanlon1997), which can benefit foreign subsidiaries. By nature, sister subsidiaries compose a social network within the MNE through various formal and informal connections (Andersson, Björkman, & Forsgren, Reference Andersson, Björkman and Forsgren2005; Chung et al., Reference Chung, Lee, Beamish and Isobe2010; Dellestrand & Kappen, Reference Dellestrand and Kappen2012; Nohria & Ghoshal, Reference Nohria and Ghoshal1997). To deal with host-country uncertainties, sister subsidiaries are likely to activate and rely on both product-similar and product-different subsidiary networks in the host market. However, the two types of network may affect subsidiary performance differently. From the coopetition perspective, we argue that the product-similar subsidiary network will have a curvilinear (inverted U-shaped) influence on subsidiary performance, whereas the product-different subsidiary network will have a monotonic (positive) effect.

Boundary Conditions of the Coopetition Perspective

To examine the strength of the predictions from the coopetitive perspective, it is useful to specify its boundary conditions, both internal and external. Foreign subsidiaries are embedded not only in an MNE's networks, but also in the broader economic environment between countries (Dellestrand & Kappen, Reference Dellestrand and Kappen2012; Holm, Johanson, & Thilenius, Reference Holm, Johanson and Thilenius1995; Meyer, Mudambi, & Narula, Reference Meyer, Mudambi and Narula2011). A subsidiary network tends to provide different benefits under different economic conditions (Chung et al., Reference Chung, Lu and Beamish2008). Economic advantage denotes the difference in economic development between an MNE's host and home countries (Ghemawat, Reference Ghemawat2001), which has been used to explain foreign subsidiary behavior and outcomes in the international business literature (Makino, Lau, & Yeh, Reference Makino, Lau and Yeh2002). Host-country economic advantage reflects competitive pressures from indigenous firms, which may fundamentally shape the way of coopetition of foreign subsidiaries within a multinational firm.

We thus introduce host-country economic advantage, which is a macro construct that captures the external competitive pressure in the host country, as a moderator in the relationship between subsidiary network and performance. Specifically, in a more developed country, foreign subsidiaries are often in a disadvantaged position in terms of country image, technology, management expertise, brand, and marketing knowledge (Al-Laham & Amburgey, Reference Al-Laham and Amburgey2005; Anand & Delios, Reference Anand and Delios2002; Dunning, Reference Dunning1993, Reference Dunning1994; Florida, Reference Florida1997). Thus, MNE subsidiaries in more developed countries may rely more on cooperation to survive and grow. This argument suggests that the economic advantage of host countries may alter the relative importance of cooperation and competition in subsidiary networks.

Moreover, intangible assets are a source of competitive advantage because these assets are more difficult for others (competitors) to duplicate. Given the increasing importance of intangible assets in value creation (Dunning, Reference Dunning1998), the intangibility of subsidiary assets can be an imperative determinant of subsidiary performance because it is more difficult for outsiders to assess the process (Contractor, Kundu, & Hsu, Reference Contractor, Kundu and Hsu2003; Delios & Beamish, Reference Delios and Beamish2001). Since intangible resources are conceived as a key inimitable capability by which subsidiaries sustain competitive advantage, inter-subsidiary cooperation and competition may affect the willingness of subsidiary mangers to share their knowledge, even though it is the desire of headquarters to stimulate innovation transfer and knowledge sharing among subsidiaries (Dellestrand & Kappen, Reference Dellestrand and Kappen2012; Kogut & Zander, Reference Kogut and Zander1993).

Building on this insight, we introduce intangible asset intensity, which is a micro construct that demonstrates the subsidiary's competence, as a moderator in the relationship between subsidiary network and performance. Indeed, innovation transfer and knowledge sharing likely enhance the performance of network actors as a whole (Andersson, Forsgren, & Pedersen, Reference Andersson, Forsgren and Pedersen2001; Fang, Wade, Delios, & Beamish, Reference Fang, Wade, Delios and Beamish2013). However, competition in the same host-country market may hinder internal transfer and create barriers against information sharing. Taken together, the relationship between network coopetition and subsidiary performance is contingent on both external and internal conditions of the subsidiaries. To examine the developed theoretical framework above, we develop a set of hypotheses below.

HYPOTHESES

Product-Similar Subsidiaries

MNEs may increasingly set up product-similar subsidiaries in a host country to increase their capacity to secure new market opportunities in the host country (Chang, Reference Chang2012). We argue that subsidiary performance may follow a shift in balance between the cooperating and competing forces as the number of product-similar subsidiaries substantially increases. When the number of product-similar subsidiaries operating in the same host country is small, they are more likely to explore the possibility of cooperation. Subsidiary managers may exchange information about their experiences in the host-country. Therefore, they may gain valuable knowledge from each other, which can be subsequently used to adjust their practices to the local conditions and enhance their respective performance. When the number of product-similar subsidiaries increases, a relatively large network can help identify more business opportunities. Inter-subsidiary cooperation can produce considerable synergistic outcomes that a single subsidiary cannot achieve individually.

However, as the number of product-similar subsidiaries increases to a certain point, the relationship of these sister subsidiaries can be transformed from partners to competitors. In this situation, inter-subsidiary competition can be intensified because these subsidiaries share many similarities in terms of products and services, as well in resources and capabilities. According to previous studies (e.g., Fauli-Oller & Giralt, Reference Fauli-Oller and Giralt1995; Kalnins, Reference Kalnins2004; Phelps & Fuller, Reference Phelps and Fuller2000), a firm may establish competing subsidiaries in a geographic location to increase their effectiveness in the marketplace and dependence on the parent firm. It is important to note that MNE headquarters may also divide a large host-country market into smaller regional markets to reduce self-cannibalization among the subsidiaries. However, as the number of product-similar subsidiaries increases to a certain point, their market overlap can be unavoidable. These subsidiaries may not only compete for headquarters’ support but also begin to compete for the same customers.

As market overlap increases, managers of product-similar subsidiaries may not be willing to share business opportunities and may avoid knowledge transfer (Björkman, Barner-Rasmussen, & Li, Reference Björkman, Barner-Rasmussen and Li2004). Subsidiaries may show self-interest by competing for a larger market space in the host market. Their cooperation can be seriously handicapped by competition in the same marketplace. The more subsidiaries established in the same host country, the greater the competition for market shares among these subsidiaries. As a result, the drawback of both internal and external competition may outweigh the benefits of cooperation. That is, to a certain point, the competition may lower profit margin for each product-similar subsidiary of the MNE. Taken together, we submit:

Hypothesis 1:

There will be an inverted U-shaped relationship between the number of an MNE's product-similar subsidiaries in a given host country and a foreign subsidiary's performance.

Product-Different Subsidiaries

In contrast, when the number of product-different subsidiaries in a host country increases, the subsidiaries may even benefit more from the diffusion and retrieval of information within a country-specific network. These subsidiaries are more likely to exhibit a high level of inter-subsidiary cooperation, facility sharing, and resource transfer because they do not compete directly in the same host-country market. We consider two scenarios. First, it has been argued that some product-different subsidiaries are exchange partners across value chain activities, such as research and development (R&D), manufacturing, logistics, distributions, or marketing activities (Jarillo & Martíanez, Reference Jarillo and Martíanez1990). Such resource exchange enhances interdependencies among subsidiaries. Interdependence promotes symbiosis and coordination in products, processes, or activities according to the respective demands of the network actor (O'Donnell, Reference O'Donnell2000; Pfeffer & Salancik, Reference Pfeffer and Salancik1978).

In the second scenario, when some MNEs pursue unrelated diversification and their subsidiaries have few business interactions, these subsidiaries may also share information through other communication channels, such as middle manager conferences, organizational forums, interpersonal relationships, or managerial ties (Chung et al., Reference Chung, Lee, Beamish and Isobe2010; Forsgren et al., Reference Forsgren, Holm and Johanson2005; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Lu and Rhee2012). Thus, as the number of product-different subsidiaries increases, the focal subsidiary has more opportunities to gain information from their sister subsidiaries. Although their competition for organizational resources also increases, cooperation may still dominate as the headquarters may coordinate and balance their needs. The difference between product-similar and product-different subsidiaries in coopetitive relationship within each type of network leads to the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2:

The number of product-different subsidiaries in a host country will positively affect subsidiary performance.

Host-Country Economic Advantage as a Macro Moderator

Research has shown that the desire of MNEs to gain access to valuable knowledge often drives them to establish subsidiaries in more advanced countries and the desire to gain access to foreign markets motivates them to establish subsidiaries in less advanced countries than their home countries (Chang, Reference Chang1995; Dunning, Reference Dunning1993; Kogut & Chang, Reference Kogut and Chang1991; Makino et al., Reference Makino, Lau and Yeh2002; Tsang & Yip, Reference Tsang and Yip2007). From this viewpoint, achieving better performance for foreign subsidiaries in more developed countries is more difficult than in less developed countries due to an increased external competition from indigenous competitors with substantial resource advantages. We argue that the economic advantage of host countries will alter the influence of coopetition among product-similar subsidiaries. That is, the inverted U-shaped relationship between product-similar network and subsidiary performance will be less evident when the host-country economic advantage is higher.

Specifically, when foreign subsidiaries have resource disadvantages in more developed markets, they are less likely to achieve better performance against indigenous competitors, even though these subsidiaries tend to cooperate. In contrast, MNE subsidiaries are more likely to achieve better performance in less developed countries because of their home-based proprietary resources and capabilities. As such, the inverted U-shaped relationship, as articulated in Hypothesis 1, will be less pronounced when the economic advantage is high (i.e., the economic development level in the host country is much higher than that in the home country) because foreign subsidiaries face fierce competition from stronger indigenous firms. In contrast, when the economic advantage is low, the inverted U-shaped relationship will be more pronounced because product-similar subsidiaries in less developed countries are capable of leveraging their home-based advantages to serve fragmented local markets and achieve better performance more effectively.

Especially, when too many product-similar subsidiaries are established in a host country, inter-subsidiary competition dominates. Subsidiary performance may suffer more in less developed countries than in more developed countries. This outcome can be primarily attributed to the inter-subsidiary competition that is more likely to escalate in less developed countries because of the lack of strong local competition. Thus, when the level of competition from indigenous host-country competitors is low, product-similar subsidiaries may depend less on inter-subsidiary cooperation. Instead, these subsidiaries are more likely to compete with one another. This situation will create pressure to cut prices; thus, lowering subsidiary performance. In more developed countries, however, strong local competition may stimulate more intense inter-subsidiary cooperation. In other words, the strong local competition may limit the capacity of foreign subsidiaries to expand their market spaces, thus reducing the possibility of inter-subsidiary competition.

Moreover, product-similar subsidiaries may leverage their network advantages to deal with the stronger local competition in more developed countries. For example, inter-subsidiary cooperation can benefit from a ‘coalition’ effect (Emerson, Reference Emerson1962) against external (indigenous) competitors. That is, product-similar subsidiaries within an MNE may band together to combat the local rivals, defend the market status quo, or maintain parity with their indigenous rivals. Thus, when the number of product-similar subsidiaries is very large, inter-subsidiary competition faced by subsidiaries in more developed countries will be less intense than those in less developed countries. In this manner, we expect:

Hypothesis 3:

The inverted U-shaped effect of the number of product-similar subsidiaries in a host country on subsidiary performance will be less pronounced for subsidiaries in more developed countries than for subsidiaries in less developed countries.

Furthermore, we argue that host-country economic advantage will enhance the positive effect of product-different networks on subsidiary performance (per Hypothesis 2). When product-different subsidiaries face strong indigenous competition in more developed countries, they may rely more on one another, leading to an enhanced cooperation. To compensate for their weaknesses, these subsidiaries may benefit more from a collective learning process by sharing intra-country information and business opportunities from the product-different networks in the more developed countries. The cooperation may address the higher economic advantage because it involves sharing local experience, coordinating diverse skills, and integrating multiple aspects of spillover effects. Thus, the influence of strong indigenous competition will diminish for subsidiaries with a larger product-different network in more developed countries. This reasoning leads to:

Hypothesis 4:

Host-country economic advantage will enhance the positive effect of the number of product-different subsidiaries in the host country on subsidiary performance.

Intangible Asset Intensity as a Micro Moderator

We further examine the moderating role of the intangible asset intensity of subsidiaries in the proposed inverted U-shaped relationship, as predicted by Hypothesis 1. We argue that the curvilinear relationship will be less pronounced for more intangible-intensive subsidiaries because these subsidiaries rely on their own competence to achieve better performance and thus are less affected by inter-subsidiary coopetition. When intangible asset intensities of subsidiaries in an MNC are low, these subsidiaries are more likely to enhance their performance by leveraging inter-subsidiary cooperation. Intangibility of subsidiary assets often leads to superior performance. Thus, similar network actors tend to emulate those who are able to produce better outcomes (Haunschild & Miner, Reference Haunschild and Miner1997; Lieberman & Asaba, Reference Lieberman and Asaba2006). That is, through MNE networks, the less intangible-intensive subsidiaries have a higher potential to gain the spillover benefit than the more intangible-intensive subsidiaries, given that knowledge spillovers in networks are often directional from knowledge-intensive actors to less knowledge-intensive actors. Taken together, the curvilinear relationship will be more pronounced for less intangible-intensive subsidiaries because they can benefit more from inter-subsidiary cooperation or the transfer of knowledge from intangible-intensive subsidiaries to enhance their performance.

When there are a large number of product-similar subsidiaries in the host country, inter-subsidiary competition will dominate. In this situation, intangible-intensive subsidiaries in an MNC are more likely to maintain their performance because they are less subject to the inter-subsidiary competition. However, these subsidiaries will recognize that the knowledge gained by less intangible-intensive subsidiaries may be used against them, despite the notion that sharing knowledge is a key source of competitive advantage for the collective benefit of network actors (Levy, Loebbecke, & Powell, Reference Levy, Loebbecke and Powell2003). Thus, intensified inter-subsidiary competition triggers the conflict of interests among product-similar subsidiaries on the use of shared knowledge. In this situation, product-similar subsidiaries may no longer be willing to closely collaborate, and the performance of less intangible-intensive subsidiaries is more likely to suffer. Taken together, coopetition in the product-similar network of an MNE exhibits a more significant influence on less intangible-intensive subsidiaries than on more intangible-intensive subsidiaries. We thus expect:

Hypothesis 5:

The inverted U-shaped effect of the number of product-similar subsidiaries in a host country on subsidiary performance will be less pronounced for subsidiaries with higher levels of intangible asset intensity than for subsidiaries with lower levels of intangible asset intensity.

We further argue that the intangibility of subsidiary assets will reduce the positive effect of product-different network on subsidiary performance. To overcome their disadvantage, subsidiaries lacking intangible resources are more likely to rely on product-different networks to enhance their performance. Through these networks, the subsidiaries may benefit from the access to heterogeneous resources and by taking advantage of the linkages (Chung et al., Reference Chung, Lu and Beamish2008; Nohria & Ghoshal, Reference Nohria and Ghoshal1997). These linkages enable them to take advantage of upside opportunities and avoid downside risks by shifting value chain activities (Kogut & Kulatilaka, Reference Kogut and Kulatilaka1994). Thus, less intangible-intensive subsidiaries may actively communicate with product-different subsidiaries in the same host country and coordinate their operations to generate synergy by pooling resources or sharing opportunities. In contrast, intangible-intensive subsidiaries are often more advantaged in dealing with local competition and thus less benefit from cooperation. The subsidiary-specific advantage can lessen the importance of the collaborative advantage generated from subsidiary networks. Thus, we present the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 6:

The level of a subsidiary's intangible asset intensity will reduce the positive effect of the number of product-different subsidiaries in a host country on the subsidiary's performance.

METHODS

Sample and Data Sources

To test our hypotheses, we combined several databases. Our sample is mainly from the Bureau van Dijk (BvD) database, which provides comprehensive data on most multinational firms and their subsidiaries (Malhotra & Lumineau, Reference Malhotra and Lumineau2011; Moschieri, Reference Moschieri2011; Rawung, Wuryaningrat, & Elvinita, Reference Rawung, Wuryaningrat and Elvinita2015), mostly in Europe. We collected the subsidiaries’ financial information, such as assets, debt, profits, and year of establishment from the database. We also obtained the macro variables of both home and host countries, such as GDP from the World Bank database, bilateral trade data from United Nations Comtrade Database (Xia, Reference Xia2011), and distance measures between home and host countries from the CEPII database. We excluded MNEs with incomplete subsidiary information (i.e., observations with missing values in any of the variables employed in this study), resulting in a sample of European subsidiaries. That is, our sample includes European MNEs and their foreign subsidiaries across European countries. Thus, our sample includes both transition (Central and Eastern European) economies and developed (Western European) economies.

Meanwhile, because of the same accounting principles (IFRS) in Europe (Schipper, Reference Schipper2005), our sample of cross-country subsidiary performance is more comparable. The unit of analysis is subsidiary-year; thus, we retained the subsidiaries with consecutive observations within the sample period from 2005 to 2011. The final sample includes 9,256 overseas subsidiaries established by 790 MNEs in 36 host countries and 27 home countries, resulting in a longitudinal dataset with 33,279 subsidiary–year observations.

We further performed t-tests for subsidiary- and MNE-level variables included in our study, that is, return on assets, intangible assets over total assets, logarithm of total assets, total liabilities over total assets, and age. We also performed t-tests for MNEs’ number of product-similar subsidiaries and number of product-different subsidiaries. All twelve tests suggested that the differences between firms that were included and those excluded were insignificant at 10% level. We also employed the Hotelling T-squared tests for joint significance and found that the difference of two populations was insignificant. Therefore, our longitudinal dataset was a representative sample of European firms to the extent that BvD database provides a representative majority of European firms.

Dependent Variable

We measured subsidiary performance using return on assets (ROA) (Delios & Beamish, Reference Delios and Beamish2001). Our sensitivity tests indicate that similar results can also be obtained by adopting return on equity or return on sales.

Independent Variables and Moderators

Product-similar subsidiary network was measured as the number (density) of all sister subsidiaries with the same SIC code at the four-digit level within a given host country in the past year. We divided this variable by 10 to adjust the coefficient scale.[Footnote 1] We added a quadratic term of this variable into the analysis to examine its curvilinear effect. Earlier studies have labeled this variable as ‘subsidiary density’ because it accounts for all active subsidiaries of an MNE in the host country (e.g., Demirbag, Apaydin, & Tatoglu, Reference Demirbag, Apaydin and Tatoglu2011; Dhanaraj & Beamish, Reference Dhanaraj and Beamish2009; Miller & Eden, Reference Miller and Eden2006). However, previous studies do not differentiate densities between product-similar and product-different subsidiaries.

Product-different subsidiary network was measured as the number (density) of all sister subsidiaries with different SIC codes at the four-digit level within a given host country in the past year. We divided this variable by 10. We also added a quadratic term of this variable into the analysis to examine its potential curvilinear effect.

Host-country economic advantage was measured based on the difference between the logarithm of host-country GDP per capita and the logarithm of home-country GDP per capita. GDP per capita is generally used to capture the level of a country's economic development (Tsang & Yip, Reference Tsang and Yip2007).

Intangible asset intensity of foreign subsidiary was measured as the subsidiary's intangible assets divided by the total assets of the subsidiary (Zhang, Li, & Li, Reference Zhang, Li and Li2014).

Control Variables

We controlled for the characteristics of the subsidiary (micro) and country (macro) structures of home and host countries (Rangan & Sengul, Reference Rangan and Sengul2009), which may also affect the foreign subsidiaries’ performance in host countries. At the subsidiary level, we controlled for subsidiary size, which was measured by the logarithm of assets. Large subsidiaries may exhibit more operational flexibility in a foreign market because these subsidiaries often possess more slack resources and are therefore less averse to international risk. Subsidiary leverage was measured as total debt over assets. This parameter reflects the exposure of a subsidiary to the risk of liquidation. We also utilized other popular measures, such as debt over equity or long-term debt over asset. These measures produced very similar results. Moreover, we controlled for subsidiary age, which was measured by the number of years from the founding date of the subsidiary. This variable captures a subsidiary's host country experience (Delios & Beamish, Reference Delios and Beamish2001; Gaur & Lu, Reference Gaur and Lu2007).

At the MNE level, we controlled for the corresponding financial variables, which were often employed to predict subsidiary performance (Luo, Reference Luo2003). Specifically, we included MNEs’ (1) profitability, measured as return on assets; (2) asset intangibility, measured as intangible assets divided by the total assets; (3) size, calculated as logarithm of total assets; (4) leverage, computed as total liabilities over total assets; and (5) firm age.

At the industry level, we controlled for (1) industry munificence, calculated with five year moving observations, in which we first regressed the logarithm of industry level sales on time trend and then took the antilog of the coefficient estimate on the time trend as the measure of industry munificence (Keats & Hitt, Reference Keats and Hitt1988); and (2) industry complexity, computed as 1 (one) minus Herfindahl index based on each firms’ sales (Dess & Beard, Reference Dess and Beard1984). Sutcliffe and Huber (Reference Sutcliffe and Huber1998) argued that industry munificence and complexity are important in shaping subsidiary relationships and performance.

Macro structures at the country level are also likely to affect foreign subsidiary performance (Rangan & Sengul, Reference Rangan and Sengul2009). At the country level, we controlled for export dependence of the host country, which was measured by the export from the host to the home country over the GDP of the host country deflated to 2005 (Weber, Davis, & Lounsbury, Reference Weber, Davis and Lounsbury2009). The export dependence is a common indicator of overseas subsidiary performance and survival (Xia, Reference Xia2011). We also controlled for geographic distance, measured by population density weighted distance (in logarithm). The data were collected from the CEPII database (Bertrand & Lumineau, Reference Bertrand and Lumineau2016; Guler & Guillén, Reference Guler and Guillén2010; Rangan & Sengul, Reference Rangan and Sengul2009). Geographic distance may affect the coordination, communication and trading costs between the parent firm and their foreign subsidiaries. Further, we controlled for logarithms of host country GDP and population to measure the market size (Zhang & Markusen, Reference Zhang and Markusen1999). Finally, we used fixed effects model to control for various time-invariant effects, as discussed below.

Estimation Technique

For our longitudinal data sets, three prevailing estimation techniques exist: pooled ordinary least squares (Pooled-OLS), random effects model, and fixed effects model. We used the fixed effects model throughout the paper (Rangan & Sengul, Reference Rangan and Sengul2009) because the fixed effects approach considers time-invariant factors, such as the relationship between headquarters and subsidiaries and national cultural difference, among others. Failure to recognize these time-invariant factors can potentially lead to biased estimation results; thus, obscuring the causal relationship. We conducted a Breusch and Pagan Lagrangian Multiplier test to examine the heterogeneity across subsidiaries. The result suggests that the subsidiary and time-fixed effects exist; thus, the Pooled-OLS is inappropriate to estimate our results (Breusch & Pagan, Reference Breusch and Pagan1979). Moreover, the choice between the random effects model and the fixed effects model depends on whether the fixed effects are correlated with the variables of interest. We carried out a Hausman test and rejected the random effects model, suggesting that only the fixed effects model can produce consistent estimates; thus the model is more appropriate for estimation (Hausman, Reference Hausman1978). We therefore used the fixed effects model for estimation throughout this work. In addition, we used subsidiary fixed effects in a robustness test, which allows us not only to control for the country fixed effects and compare different host countries but also to obtain the most robust results (Hausman, Reference Hausman1978).

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the summary of the statistics and the correlation matrix of the variables. The table indicates that multicollinearity is not an issue because the largest correlation coefficient between pairs of predictor variables is 0.475. Moreover, we verified multicollinearity in the regression models by examining the variance inflation factor (VIF) for each predictor variable. The largest VIF is approximately 4.36, which is significantly lower than the general cut-off threshold of 10 (Neter et al., 1996).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix

Note: Correlation coefficient exceeding 0.01 is significant at the 5% level.

Table 2 shows the results of the fixed effects model analyses. Model 1 provides the results for the control variables only. Model 2 includes the two main effects of the number of product-similar and product-different subsidiaries. Model 3 adds the quadratic terms of the subsidiaries to examine their potential curvilinear effects. Model 4 tests the moderating effect of economic advantage. Model 5 assesses the moderating effect of intangible asset intensity. Model 6 is a full model that includes all predictor variables and interaction terms. The results are highly consistent across models in terms of sign, magnitude, and significance level. The results show that larger foreign subsidiaries exhibit better performance among the significant control variables. The effect of financial leverage is significantly negative. In contrast, geographical distance positively affects subsidiary performance, as expected.

Table 2. Results of fixed effects models predicting subsidiary performance

Notes: *** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05; + p < 0.10. Time varying variables are lagged. Number of product-similar subsidiaries and number of product-different subsidiaries are descaled by 10.

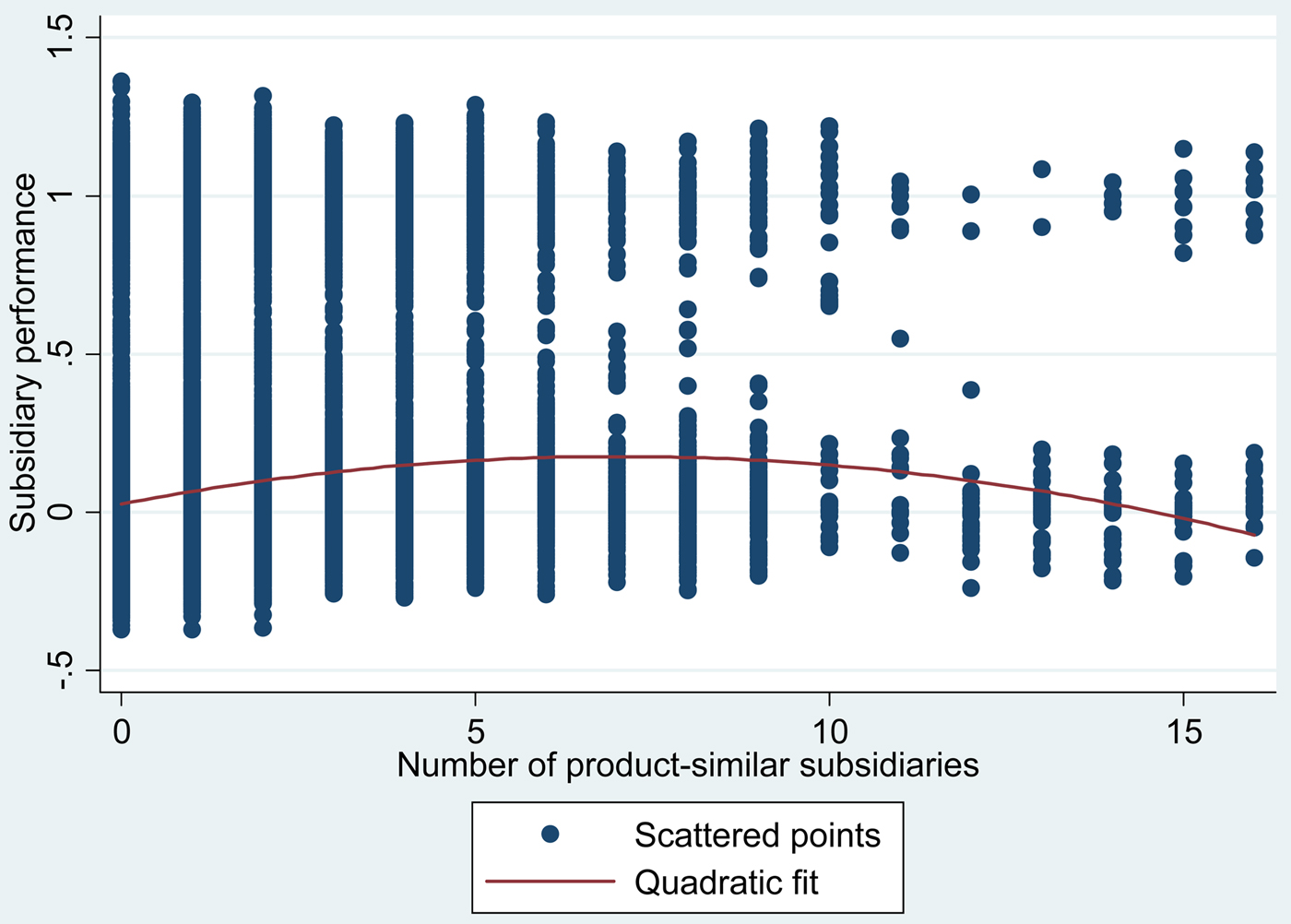

Hypothesis 1 predicts that an inverted U-shaped relationship exists between the number of product-similar subsidiaries and subsidiary performance. In Model 2, the main effect of the number of product-similar subsidiaries is not significant. However, Model 3 supports Hypothesis 1 because the number of product-similar subsidiaries and its quadratic terms are both significant (for the linear term, β = 0.035, p < 0.01; for the quadratic term, β = −0.034, p < 0.05), suggesting that moderate levels of subsidiary number lead to optimal performance. For better interpretation, we use Figure 1 to illustrate this interaction. To draw the figure, we plotted the original data points of subsidiary performance on the vertical axis and the number of product-similar subsidiaries on the horizontal axis, using scatter and quadratic fit plots to indicate relationship between the two variables. The figure exhibits an inverted-U shaped curve, with the highest point indicated by the regression results appearing at around 6. This value is approximately the middle point of our observations (mean = 6.394 and median = 5). Meanwhile, when the number of subsidiaries is below 5, subsidiary performance decreases by 0.017 with an additional product-similar subsidiary, whereas when the number of subsidiaries is above 5, subsidiary performance increases by 0.015 with an additional product-similar subsidiary. The effect sizes are considerable compared with the mean level of subsidiary performance, 0.047. Further, the addition of the number of product-similar subsidiaries and its squared term also substantially increases the explanatory power as the within-R2 increased by 6.5%, and the impact is considerable compared with 15.5% of the baseline model and 33.5% of the full model.

Figure 1. Curvilinear effect of the number of product-similar subsidiaries on subsidiary performance Left: high level of economic advantage; right: low level of economic advantage

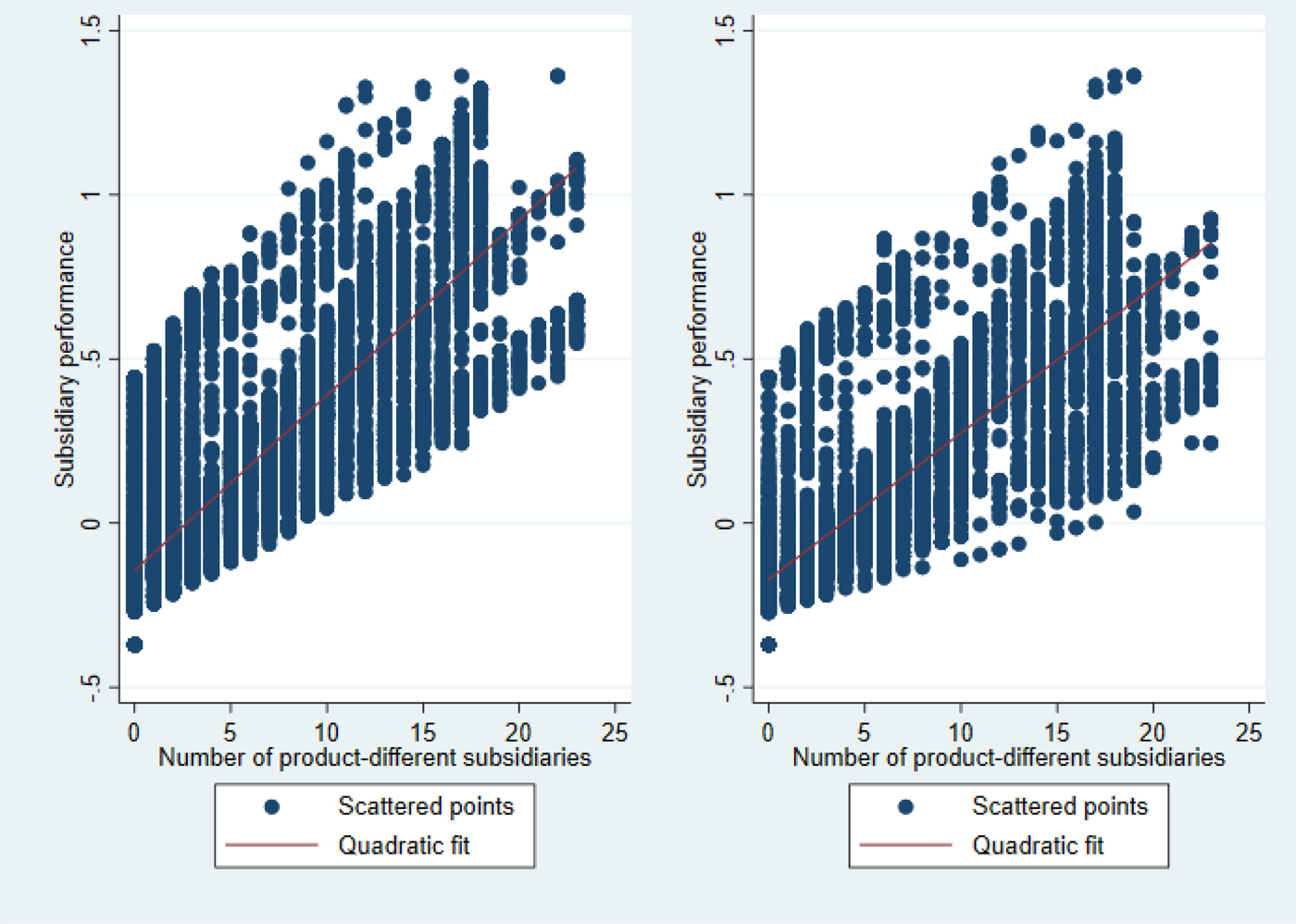

Hypothesis 2 states that the number of product-different subsidiaries has a positive effect on subsidiary performance. In Model 3, the coefficient estimate of the number of product-different subsidiaries is positive and significant (β = 0.017, p < 0.001). However, its quadratic term is not significant (β = −0.005, ns.). These findings indicate that product-different subsidiary network has a monotonic, rather than a curvilinear effect on subsidiary performance, as we expected. Meanwhile, subsidiary performance increases by 0.017 with an additional product-different subsidiary. Compared with the average subsidiary performance 0.047, the impact is substantial. The inclusion of the number of product-similar subsidiaries enhances the explanatory power notably because the within-R2 increased by 4.5%, and the impact is sizeable compared with 15.5% of the baseline model and 33.5% of the full model. Thus, Hypothesis 2 is supported.

Hypothesis 3 posits that the inverted U-shaped influence of the number of product-similar subsidiaries on subsidiary performance is less pronounced for subsidiaries in more developed countries than for subsidiaries in less developed countries. In Model 4, the coefficient estimates of the interaction of host-country economic advantage and the linear term of the number of product-similar subsidiaries (β = −0.017, p < 0.05), as well as the interaction of host-country economic advantage and its quadratic term (β = 0.008, p < 0.001), are both significant. The moderating effects are sizeable compared with the mean effects. Figure 2 demonstrates this interaction. We drew two subfigures with original values of the variables, dividing them by high (one standard deviation above the mean) versus low (one standard deviation below the mean) levels of economic distance. In each subfigure, we plotted subsidiary performance on the vertical axis with common scale on the vertical axis to ease comparison and the number of product-similar subsidiaries on the horizontal axis. The two subfigures indicate that subsidiaries in less developed countries in general can perform better than those in more developed countries, since the inverted U-shaped relationship is less pronounced in countries with economic advantage. Thus, Hypothesis 3 is supported.

Figure 2. Moderating effect of host-country economic advantage on the number of product-similar subsidiaries Left: high level of economic advantage; right: low level of economic advantage

Hypothesis 4 maintains that economic advantage enhances the positive effect of the number of product-different subsidiaries on performance. In Model 4, the interaction between economic advantage and the number of product-different subsidiaries is significant and positive (β = 0.002, p < 0.01). The moderating influence is substantial compared with the main effects. We drew Figure 3 with the original data, split them with high versus low level of economic advantage. Subsidiary performance is on the vertical axis and the number of product-different subsidiaries is on the horizontal axis. The figures demonstrate that the slope of the left subfigure (high economic advantage) is steeper than the right one (low economic advantage), suggesting that the cooperation among product-different subsidiaries is more important in dealing with external competitive pressures in more advanced countries. Thus, Hypothesis 4 is supported.

Figure 3. Moderating effect of host-country economic advantage on the number of product-different subsidiaries Left: high level of intangible asset intensity; right: low level of intangible asset intensity

Hypothesis 5 suggests that the inverted U-shaped effect of the number of product-similar subsidiaries on subsidiary performance is less pronounced for subsidiaries with higher levels of intangible asset intensity than for subsidiaries with lower levels of intangible asset intensity. In Model 5, the coefficient estimates on the interaction of intangible asset intensity and the linear term of the number of product-similar subsidiaries (β = −0.041, p < 0.01), as well as on the interaction of intangible asset intensity and its quadratic term (β = 0.030, p < 0.001), are significant. The moderating effects are sizeable compared with the main effects. We used original values of the variables to draw Figure 4. Then in each subfigure, we plotted subsidiary performance on the vertical axis and the number of product-similar subsidiaries on the horizontal axis. The figure suggests that the inverted-U shaped curve became less pronounced when the level of intangible asset intensity is higher. Thus, Hypothesis 5 is supported.

Figure 4. Moderating effect of intangible asset intensity on the number of product-similar subsidiaries Left: high level of intangible asset intensity; right: low level of intangible asset intensity

Hypothesis 6 predicts that a subsidiary's intangible asset intensity reduces the positive effect of the number of product-different subsidiaries on the subsidiary's performance. In Model 5, the interaction between intangible asset intensity and the number of product-different subsidiaries is significant and positive (β=0.005, p < 0.001), which contradicts our prediction. The moderating effects are economic meaningful compared with the mean effects. We drew Figure 5 with the original data, with subsidiary performance on the vertical axis and the number of product-different subsidiaries on the horizontal axis. The slope of the left subfigure (high level of intangible asset intensity) is steeper than of the right one (low level of intangible asset intensity), suggesting that subsidiaries with higher levels of intangible asset intensity are more likely to leverage the collaborative advantages. Hence, Hypothesis 6 is not supported.

Figure 5. Moderating effect of intangible asset intensity on the number of product-different subsidiaries

DISCUSSION

We have addressed the question of how different types of subsidiary networks in a host country affect subsidiary performance from a coopetition perspective. Our results demonstrate that product-similar subsidiary network exhibits an inverted U-shaped effect on subsidiary performance, whereas product-different subsidiary network shows a positive effect. Moreover, host-country economic advantage and intangible asset intensity reduce the inverted U-shaped effect of product-similar subsidiary network on subsidiary performance. Moreover, both economic advantage and intangible asset intensity enhance the positive effect of product-different subsidiary network. However, the moderating effect of intangible assets contradicts our prediction. Our findings provide useful theoretical and practical implications.

Implications for the Coopetition Perspective

This study contributes to the existing literature on subsidiary performance from the coopetition perspective. Understanding the determinants of foreign subsidiary outcomes has been a central research topic in the organization theory and international business literatures (e.g., Delios & Beamish, Reference Delios and Beamish2001; Miller & Eden, Reference Miller and Eden2006; Mitchell, Shaver, & Yeung, Reference Mitchell, Shaver and Yeung1994; Shaver, Mitchell, & Yeung, Reference Shaver, Mitchell and Yeung1997; Tsang & Yip, Reference Tsang and Yip2007; Zaheer, Reference Zaheer1995). The literature has documented various factors that may affect subsidiary performance, including the choice of foreign entry mode, MNE commitment of resources, corporate diversification strategy, host-country experience, intangible assets, knowledge transfer, and various national differences, among others. However, limited attention has been given to the examination of the effect of coopetitive relationships among subsidiaries in the host country on their performance. Thus, our study has taken a step to fill this gap.

Our study supports the idea that foreign subsidiaries within an MNE do not operate in a relational void. Researchers have conceptualized MNEs as networks that consist of cross-border subsidiaries and have focused on the competitive advantages of MNE networks (Chung et al., Reference Chung, Lu and Beamish2008; Nohria & Ghoshal, Reference Nohria and Ghoshal1997). By conceptualizing MNE network advantages at the corporate level, Vermeulen and Barkema (Reference Vermeulen and Barkema2002) demonstrated that the number of foreign subsidiaries affects an MNE's profitability. Researchers have also suggested that country-specific subsidiary networks, which are operationalized as the total number of sister subsidiaries in a given country, may affect subsidiary survival (Demirbag et al., Reference Demirbag, Apaydin and Tatoglu2011; Dhanaraj & Beamish, Reference Dhanaraj and Beamish2009). Chung et al. (Reference Chung, Lu and Beamish2008) suggested that a subsidiary level analysis of MNE network advantages is useful in identifying the subsidiaries that are more likely to benefit from linkages among subsidiaries. Our study contributes to the literature because it has determined the tension between cooperation and competition by differentiating product-similar from product-different subsidiary networks. Moreover, our study provides empirical analysis and evidence, which is a contribution that can address the paucity of empirical examinations of coopetition outcomes by using quantitative data (Soppe, Lechner, & Dowling, Reference Soppe, Lechner and Dowling2014).

Our findings suggest that the coopetition approach of subsidiary performance is indeed useful in predicting the effect of subsidiary networks. Earlier studies mainly focused on coopetition within inter-firm relationships, such as joint ventures or alliances (Bengtsson & Kock, Reference Bengtsson and Kock2000; Dowling, Roering, Carlin, & Wisnieski, Reference Dowling, Roering, Carlin and Wisnieski1996; Gnyawali et al., Reference Gnyawali, He and Madhavan2006; Park & Russo, Reference Park and Russo1996). Studies at the subsidiary level have focused on either inter-subsidiary competition (e.g., Kalnins, Reference Kalnins2004) or inter-subsidiary cooperation (e.g., Ghoshal & Bartlett, Reference Ghoshal and Bartlett1990). Meanwhile, the notion of coopetition has been increasingly used to explain inter-subsidiary relationships (e.g., Birkinshaw, Reference Birkinshaw2001; Luo, Reference Luo2004, Reference Luo2005; Phelps & Fuller, Reference Phelps and Fuller2000; Tsai, Reference Tsai2002). However, this stream of literature does not explicitly specify the conditions under which network actors are more likely to collaborate or to compete against each other. Our results show that product-similar and product-different subsidiary networks in a host country have different effects on subsidiary profitability.

Specifically, when the number of product-similar subsidiaries in a host country is small, cooperation is likely to dominate to deal with host-country uncertainties. Product similarity captures subsidiaries’ collective identity because these subsidiaries compete against indigenous rivals in a host country. However, as the number of product-similar subsidiaries increases to a certain point, inter-subsidiary competition can significantly intensify. The relationship among the subsidiaries will be transformed from cooperation to competition. Our findings support the notion that an inverse U-shaped relationship exists between product-similar subsidiary density and performance. The result also suggests that subsidiaries, which can use organizational resources efficiently and to compete against external competitors effectively, achieve the best performance. In contrast, cooperation is likely to become dominant among product-different subsidiaries because of their lack of direct market competition. Thus, our results confirm that product-different subsidiaries continue to benefit from their increasing number or density in the host country.

Our study also explored the boundary conditions of the coopetition perspective on subsidiary performance by introducing host-country economic advantage and intangible asset intensity as moderators. To gain a better understanding of the coopetitive effect of a subsidiary network, we must determine the context in which subsidiaries are embedded (Beugelsdijk, Reference Beugelsdijk2007; Dicken & Malmberg, Reference Dicken and Malmberg2001; McCann & Mudambi, Reference McCann and Mudambi2005). Although management scholars have thoroughly studied the subject of cultural distance, less attention has been accorded to host-country economic advantage (Dow & Karunaratna, Reference Dow and Karunaratna2006), which demonstrates competitive pressures from indigenous firms. In more developed countries, local firms may impose stronger competitive pressures.

As noted, our research context is European MNEs and their foreign subsidiaries across European countries, which include both transition (Central and Eastern European) economies and developed (Western European) economies. In general, the developed countries are more economically advanced than the transition countries. Levels of intangible asset intensity are higher for foreign subsidiaries from European developed economics than for foreign subsidiaries from European transition economics. Our findings imply that the inverted U-shaped relationship between product-similar subsidiary density and performance is more pronounced for subsidiaries in transition economies than for subsidiaries in developed economies. This finding suggests a trade-off. The performance of a product-similar subsidiary network is more difficult to enhance in Western European countries (due to stronger local competition) than in Central and Eastern European countries. However, the performance of a network is more difficult to maintain in the transition countries (because of stronger internal competition) than in the developed countries.

Moreover, international business studies have emphasized the importance of intangible asset advantages (Delios & Beamish, Reference Delios and Beamish2001; Dunning, Reference Dunning1993; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Li and Li2014). Extensive intangible resources demonstrate subsidiary-specific knowledge that can be transferred among MNE subsidiaries. In our view, cooperation may increase the transfer of knowledge from intangible-intensive to less intangible-intensive subsidiaries through the host-country-specific networks, whereas competition diminishes the knowledge transfer at the subsidiary level. The implication of our findings is that the inverted U-shaped relationship between product-similar subsidiary density and performance is more pronounced for subsidiaries from transition economies than for those from developed economies. Thus, another trade-off occurs, that is, product-similar subsidiary cooperation is more like to enhance the performance of subsidiaries from transition economies than that of subsidiaries from developed economies (because of the lack of spillover effect). However, when product-similar subsidiary competition occurs, the performance of subsidiaries from developed economies is more effectively maintained than that of subsidiaries from transition economies (because of their relative technological disadvantages).

As expected, our results show that economic advantage strengthens the effect of product-different subsidiary density on subsidiary performance because cooperation allows subsidiaries to collaborate against strong external competitive pressures. However, we have also found that intangible asset intensity strengthens, rather than reduces, the effect of product-different subsidiary density on subsidiary performance, which contradicts our prediction. This finding suggests that intangible resource advantages and collaborative advantage are not substitutes but complements. One possible explanation is that intangible-intensive subsidiaries are more capable of coordinating network activities, leading to collaborative synergies that play an important role in enhancing competitive performance. Thus, our findings not only contribute to the MNE network literature on subsidiary performance, but also serve as a basis for further exploration of the boundary conditions of the coopetition perspective by highlighting the contingent value of different moderators.

Practical Implications

The observed findings above have practical implications as well. Our findings can guide subsidiary managers on managing coopetitive relationships with sister subsidiaries to achieve the best performance. Given that cooperation and competition often coexist, understanding their combinations and inferences in different situations is useful. Our study indicates that the density of product-similar subsidiaries represents an important pattern of the coopetitive relationships among these subsidiaries. A proper match between the coopetitive role and network density may enhance firm performance or avoid unwanted side-effects. In contrast, a mismatch is a potential source of problems. For example, competition may reduce the likelihood of subsidiaries to seek partnership because the primary concern of subsidiaries is how to partition a pie (market share) in such a way that their self-interest is maximized. However, a match or mismatch varies between product-similar and product-different networks. Relatively, product-different networks are more likely to encourage subsidiaries to transfer developed knowledge, which may enhance their collective advantages against strong local competition in the host country.

Subsidiary establishment, country choice, and market exit are corporate-level decisions. For MNEs, balancing cooperation and competition among subsidiaries may help them achieve better performance. To this end, MNEs should have a diverse subsidiary portfolio, which could be achieved by specifying the number and composition of subsidiaries in each host country. The active management of subsidiary portfolio may generate network advantages in host countries. Moreover, MNEs must consider external competitive pressures that vary across countries. Similarly, the subsidiaries’ intangible assets affect knowledge transfer. These factors may shift the relative importance of cooperation and competition among subsidiaries to achieve the best performance.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

The limitations of this study can provide opportunities for future research. First, our study suggests that the subsidiary portfolio of an MNE (the number and type of subsidiaries) in a host country may affect subsidiary performance from a coopetition perspective. The performance and survival of subsidiaries are frequently used as two dependent variables to understand the operational outcomes of the subsidiaries (Delios & Beamish, Reference Delios and Beamish2001; Tsang & Yip, Reference Tsang and Yip2007). However, it is not clear whether the conditions that lead to poor economic performance may also lead to market exit such as subsidiary dissolution or divestiture (Delios & Ensign, Reference Delios and Ensign2000). Constrained by data limitations and availability, our study is unable to examine whether our current framework can also predict subsidiary survival. Future research may extend our theoretical framework this direction because subsidiary survival or failure affects an MNE's subsidiary portfolio, and consequently influences the coopetitive relationships among sister subsidiaries.

Second, the extent to which a subsidiary will cooperate or not within the network depends on its mandate granted by the headquarters of the MNE.[Footnote 2] Future research may rely on surveys or interviews to reveal whether the subsidiary mandate can be changed or renegotiated over time. In general, when specific subsidiary mandates require greater local embeddedness, the incentives for cooperation with other subsidiaries in the MNE network may diminish because the mandates increase the incentives for cooperation with other local players. Thus, it will be useful for future research to focus more on coopetition with various local stakeholders, which goes beyond our current study as we have focused only on coopetition among subsidiaries within the MNE network.

Third, we argue that identifying the boundary conditions of the coopetition perspective is a way to gain better understanding of subsidiary performance. We only focused on host-country economic advantage and intangible asset intensity as the two moderators. However, many other factors, such as cultural and institutional differences between countries, may also shift the cooperative and competitive relationships of sister subsidiaries. Future works may extend our research framework toward the identification of other meaningful moderators; the lack of attention to important boundary conditions may have limited our understanding of how coopetition can precisely predict subsidiary performance.

CONCLUSION

Despite the aforementioned limitations, this study represents an important contribution to the coopetition perspective on subsidiary performance. This study provides better comprehension of the different types of subsidiaries networks in a host country along with their different effects, which have not been theorized or examined in the past. The results suggest that subsidiary portfolio management in a host country is important because the number and composition of subsidiaries are crucial in terms of their coopetitive network effects. MNEs have increasingly established subsidiaries to achieve their global strategies. Thus, determining how subsidiary performance will improve in each country by drawing implications from our findings is pivotal. We hope that our study provides a basis for future research to examine the outcomes of subsidiary portfolios from the coopetition perspective, which in turn will also enrich the coopetition literature.