INTRODUCTION

The study of the impact of social networks and interpersonal relationships on business practices in different regions of the world has been important in international business research in the past decade (Velez-Calle, Robledo-Ardila, & Rodriguez-Rios, Reference Velez-Calle, Robledo-Ardila and Rodriguez-Rios2015). Researchers have used frameworks based on social networks, institutions, social capital, and group identity to explore the role that an individual's membership of networks and alliances plays in influencing their business decisions and practices (Coleman, Reference Coleman1988; Granovetter, Reference Granovetter2005; Ledeneva, Reference Ledeneva2018; Li, Reference Li2007; Putnam, Reference Putnam1995; Qi, Reference Qi2013; Sato, Reference Sato, Burawoy, Chang and Hsieh2010). In Arab countries, wasta describes networks rooted in family and kinship ties that individuals, acting through their connections, use to bypass formal bureaucratic procedures and to ease the process of achieving a goal (Cunningham & Sarayrah, Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993; Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006a, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006b; Smith, Torres, Leong, Budhwar, Achoui, & Lebedeva, Reference Smith, Torres, Leong, Budhwar, Achoui and Lebedeva2012a). Wasta is also known as ma'arifa or piston, which denote similar practices in North African nations such as Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco (Iles, Almhodie, & Baruch, Reference Iles, Almhodie and Baruch2012; Smith, Huang, Harb, & Torres, Reference Smith, Huang, Harb and Torres2012b).

The countries of the Arab Middle East hold substantial importance for the world, politically, geographically, and economically (Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006a; Iles et al., Reference Iles, Almhodie and Baruch2012). As a result, scholars in economics have conducted substantial research on the countries of the Arab Middle East; however, management inquiry has been scarce and fragmented (Iles et al., Reference Iles, Almhodie and Baruch2012; Khakhar & Rammal, Reference Khakhar and Rammal2013; Metcalfe, Reference Metcalfe2007; Weir, Reference Weir and Warner2000).

Indeed, there is still much that western economies and other cultures can learn about the management practices of the countries of the Arab Middle East to inform the development of their own practices. Doing so will answer the call of researchers for more contextually embedded and context-specific research (Tsui, Reference Tsui2004) to complement and contextualise the management theories developed in the UK, the US, and the countries of western Europe (Hofstede, 2017).

This article aims to leverage our theoretical understanding of wasta by organising the fragmented research on this practice through a systematic literature review that will enable us to understand the practice in a more holistic way. In conducting this review, we analysed the identified papers in terms of the theoretical lens according to which wasta was viewed, so creating a bridge between a theoretical focus on the macro aspect of wasta (wasta viewed according to institutional theory) and an alternative focus on its micro aspects (wasta interpreted through social capital and social networks theories), thus leading to the development of a holistic model of wasta.

From a practical perspective, in the context of business and organisational management, wasta exists where social networks are influential in organisational decision making. Understanding wasta is therefore important not just for Arab business people, but also for international businesses that operate in the countries of the Arab Middle East. Moreover, understanding wasta processes can help researchers better understand the way in which social capital and other forms of social networks impact businesses around the world.

The article starts by exploring different informal social networks around the world, thereby revealing the similarities between them but also stressing their differences and justifying the importance of studying wasta. The article then presents the methodology used for the systematic literature review. The importance of wasta in the business context is then explored, followed by a discussion of gaps in research on wasta. Next, the article provides a detailed exploration of the different theoretical lenses used to explore wasta: the use of wasta as a substitute for weak formal institutions and as a form of social capital and social network. Based on this discussion, the article then discusses a holistic model of wasta, thereby adding to our understanding of wasta in terms of social capital in complex networks. A further section discusses the implications of this research for theory and advances suggestions for practitioners. The article concludes by discussing the limitations of this study and providing suggestions for future research.

INFORMAL SOCIAL NETWORKS AROUND THE WORLD

Management scholars have moved from an initial focus on how business approaches developed in the UK, US, and western Europe can be applied in different contexts towards what organisations can learn from business practices in emerging and developing economies (Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006a; Horak & Klein, Reference Horak and Klein2016; Weir, 2003). Some have explored different forms of social networks, such as guanxi in China (Chen, Chen, & Huang, Reference Chen, Chen and Huang2013; Chen, Reference Chen2016; Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006a; Qi, Reference Qi2013) and its counterparts: wasta in the Arab Middle East (Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006a; Metcalfe, Reference Metcalfe2007); blat in former Soviet countries (Ledeneva, Reference Ledeneva2006; Onoshchenko & Williams, Reference Onoshchenko and Williams2014); compadrazgo in Latin American countries (Velez-Calle et al., Reference Velez-Calle, Robledo-Ardila and Rodriguez-Rios2015); yongo, yonjul, and inmaek in South Korea (Horak, Reference Horak2014; Horak & Taube, Reference Horak and Taube2016), ‘pulling strings’ in the UK (Smith et al., 2012); and yruzki in Bulgaria (Williams & Yang, Reference Williams and Yang2017), so highlighting the important impact these social networks have on different aspects of business practices in all of these areas. These networks, although similar to the concepts of alumni or professional networks in the west in terms of the benefits they bring to their members (Horak, Reference Horak2014; Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006a), have a key difference in that they are deeply embedded in the cultures of the countries in which they are practised (Horak, Reference Horak2014; Horak & Taube, Reference Horak and Taube2016; Hutchings & Weir, 2006; Ledeneva, Reference Ledeneva2006; Velez-Calle et al., Reference Velez-Calle, Robledo-Ardila and Rodriguez-Rios2015). This cultural embeddedness means that they also differ in the facts that they are far less accessible to, and more prescriptive towards, their members (Cunningham & Sarayrah, Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993; Horak & Taube, Reference Horak and Taube2016).

Despite the similarities of such networks in terms of structure and form, which has led to some researchers treating these practices as different faces of the same coin (e.g., Smith et al., Reference Smith, Torres, Leong, Budhwar, Achoui and Lebedeva2012a; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Huang, Harb and Torres2012b), other scholars researching these networks have used analytical frameworks from different theoretical perspectives to unpack the differences among them. For instance, Horak and Taube (Reference Horak and Taube2016) compared the networks of guanxi in China and yongo in Korea using social capital and institutional theory. They observed some similarities: both networks are society-spanning constructs; they are relatively closed to outsiders; and they are developed and maintained through reciprocal action that creates trust and trustworthiness, which serves as a major factor in network cohesion. Nevertheless, the two networks evince several fundamental differences, most significantly the fact that guanxi can be characterised as utilitarian (purpose-based), whereas yongo is, in principle, based on cause-based ties.

Other researchers have focused on how differences in the origins of each practice lead to variations in how individuals interact and the processes and procedures they go through to achieve a goal in each of these practices. In the case of wasta, its origin is in tribalism (Cunningham & Sarayrah, Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993); for guanxi, in Confucianism (Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006b); and for blat, in communism (Onoshchenko & Williams, Reference Onoshchenko and Williams2013). For example, it is argued that patrons of blat generally view it as a positive practice due to the historic reliance upon it in the countries in which it prevailed during the Soviet era (Onoshchenko & Williams, Reference Onoshchenko and Williams2014). This is because in the Soviet command economy, having friends in strategic places was highly advantageous because although the possession of money did not guarantee access to commodities, goods, and services that were in short supply, these could become accessible using personal connections (ibid.). Thus, people view blat positively because it is necessary and involves helping other individuals without the need for a direct repayment (Onoshchenko & Williams, Reference Onoshchenko and Williams2013). On the other hand, wasta involves different and conflicting emotions, as it is sometimes viewed as a corrupt or unjust act that contradicts the teachings of Islam, the main source of ethical guidance for the majority of the people in the region (Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006b; Mohamed & Mohamad, Reference Mohamed and Mohamed2011). For example, using one's connections (or wasta) to hire an unqualified individual for a job for which other applicants are more suitable can be ethically problematic and directly contradictory to the teachings of Islam (Cunningham & Sarayrah, Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993). Such differences have an impact on how policy planners and managers in each of the different countries in which these practices exist can manage them – and whether they should.

METHODS

In order to develop a holistic understanding of wasta and the main theoretical perspectives from which it has been studied, we conducted a systematic literature review of wasta research. The benefit of a systematic review for wasta is made evident by similar reviews conducted on guanxi and published in Management and Organization Review (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Chen and Huang2013; Li, Zhou, Zhou, & Yang, Reference Li, Zhou, Zhou and Yang2019). These studies tied the existing literature together and provided suggestions for advancing research on guanxi.

We conducted our review between July and December 2019. The study included academic journal articles on wasta published between 1993, when Cunningham and Sarayrah published the first book that explicitly focused on wasta, and 2019. The focus on academic journal papers rather than book chapters and other sources was due to the theoretical and methodological detail which such publications provide, so allowing the objectives of a systematic review to be aligned with the aims of this research study (Cho & Egan, Reference Cho and Egan2009). The only exception was the inclusion of Cunningham and Sarayarah's (Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993) book Wasta: The Hidden Force in Middle Eastern Society, which, as the seminal work on wasta, is referenced by almost all the journal articles analysed.

The inclusion criteria for selecting journal articles were as follows:

1. The articles are published in English in peer-reviewed journals

2. The articles explore wasta as a core concept, rather than anecdotally

To assess the articles, one of this article's authors first read the selected article, noting the year of publication, the journal of publication, the methodology, the topical focus, and the geographical focus, that is, the country or countries in which primary data was collected. The analysis of the papers focused on the theoretical lens (social capital theory, institutional theory, attribution theory, etc.) and corresponding level of analysis (micro or macro) that was used to view wasta. Although some papers clearly highlighted the theory used to explore wasta, others were less clear on this and we had to classify them through reading the paper carefully and deducing this from the discussions presented.

The review used the search engine Library Plus at the first author's university. This provides access to 75 databases, including Business Source Complete, Emerald, JSTOR, openDORA, ProQuest and Scopus. The keywords were: ‘Wasta’, ‘networks in the Arab Middle East’, ‘favours in the Arab Middle East’, ‘social networks in the Arab Middle East’, ‘social relations in the Arab Middle East’, and ‘social capital in the Arab Middle East’. This search identified 56 journal articles, 41 of which met our inclusion criteria and were selected for further analysis.

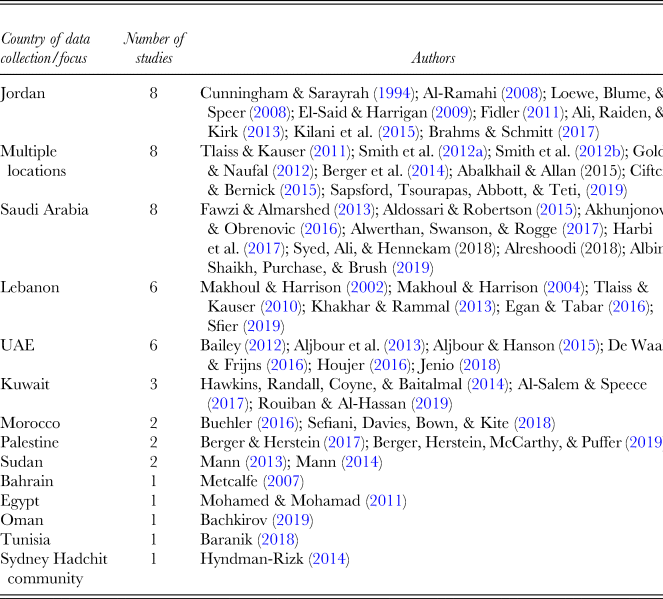

Wasta research is still in its infancy and we were aware of relevant papers published in different journals then the ones available in the databases consulted; so, the search process was repeated using Google Scholar to identify such articles. Such papers often appear in newer, smaller, or regionally focused journals with which are often less academically rigorous but have the advantage of providing insights from an indigenous emic view of wasta. This second process identified 31 additional relevant articles, published mainly in journals focusing on the Arab Middle East (e.g., Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review; Journal of Arabian Studies: Arabia, the Gulf, and the Red Sea; Middle East Journal). After applying the inclusion criteria, we included 22 of the 31 articles, thus giving a total of 63 articles included in the review. Table 1 gives an overview of the articles included in the review. These are highlighted with an asterisk (*) in the reference list.

Table 1. Articles published by time period

Table 1 highlights a hiatus in wasta research, between Cunningham and Sarayrah's seminal textbook, published in 1993 (and their subsequent 1994 article) and Makhoul and Harrison's (Reference Makhoul and Harrison2002) exploration of this practice through a client–patron lens in the context of Lebanon. It can be seen that the number of papers has significantly increased since 2012, with 48 of the 63 articles published in the last seven years. This increase in the quantity of research has been partially reflected in the quality of the publications, with some papers appearing in high impact journals (e.g., Aldossari & Robertson, Reference Aldossari and Robertson2015; Berger, Silbiger, Herstein, & Barnes, Reference Berger, Silbiger, Herstein and Barnes2014; Khakhar & Rammal, Reference Khakhar and Rammal2013; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Torres, Leong, Budhwar, Achoui and Lebedeva2012a; Sidani & Thornberry, Reference Sidani and Thornberry2013;). Nevertheless, the majority of wasta research continues to be limited to regional and lower impact journals (see Table 2).

Table 2. Journals that have published more than one article on wasta

In terms of methodology, papers were mainly either qualitative (20 papers) or quantitative (17 papers), with fewer using mixed methods (8 papers). Most of the comparative studies were quantitative in nature (5 papers), with only one comparative qualitative and one mixed-methods paper.

Moreover, as Table 3 highlights, whereas much of the initial wasta research (up to 2010) focused on developing countries of the Arab Middle East, such as Jordan and Lebanon, research in the last three years has diversified to include North African countries, such as Morocco and Tunisia, in addition to an increase of publications dealing with the highly-developed, rich and urbanised Gulf states such as Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the UAE, where these networks are integral to the survival of different societal groups (Albin Shaikh et al., Reference Albin Shaikh, Purchase and Brush2019; Al-Salem & Speece, Reference Al-Salem and Speece2017; Rouiban & Al-Hassan, Reference Rouibah and Al-Hassan2019).

Table 3. Location of study data collection/focus

Finally, it is worth noting that, although wasta research was initially general in its focus, there is evidence that recent research is becoming more specific. For instance, research initially tended to focus on male wasta network groupings, but there have been recent studies of the use of wasta by women (e.g., Abalkhail & Allan, Reference Abalkhail and Allan2016; Bailey, Reference Bailey2012), immigrants (e.g., Hyndman-Rizk, Reference Hyndman-Rizk2014; Stevens, Reference Stevens2016), and non-Arab expatriates (e.g., Aljbour & Hanson, 2013, Reference Aljbour and Hanson2015).

Based on the findings of the literature review, the next section presents our understanding of wasta and its importance in the business context. Following that, we highlight the gap in our theoretical understanding of wasta and identify the main theoretical lenses through which it had been studied.

WASTA AND ITS IMPORTANCE IN THE BUSINESS CONTEXT

Linguistically, wasata, better known as wasta, is an Arabic word that means ‘the middle’ and is associated with the verb yatawassat, to mediate; to steer conflicting parties toward a middle point, or compromise (Cunningham & Sarayrah, Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993). In classical Arabic, wasata is used to refer to the act of mediation, and a waseet is the person who performs it (Aldossari & Roberson, Reference Aldossari and Robertson2015; Cunningham & Sarayrah, Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993). In all etymological explanations, W, S, and T connote a middle place; in spoken Arabic in the Middle East, however, the word wasta is used to refer to both the act and the person mediating between the parties (Aldossari & Roberson, Reference Aldossari and Robertson2015; Tucker & Bucton-Tucker, Reference Tucker and Bucton-Tucker2014b). This etymological point is important because it emphasises the embodied nature of wasta, which does not exist outside of a human context in which complex motivations and diverse and polyvalent social identities – rather than disembodied abstractions such as ‘rational economic actors’ – represent the fundamental units of analysis and theory. The etymology of wasta, as an action and a person, is generally associated with the notion of occupying a middle place in a network (Aldossari & Roberson, Reference Aldossari and Robertson2015; Al-Ramahi, Reference Al-Ramahi2008). Looking further into the linguistic roots of the word, wasta can be understood simply as the ability ‘to get things done through the use of social connections’ (Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006a). This highlights the importance of ‘brokerage’ or intermediation between the different parties in the wasta process.

Wasta is sometimes defined as favouritism that is normally based on tribal and family affiliation (Cunningham & Sarayrah, Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993). It has been used as a descriptive term applied to behaviours that are widely evident within Arabic culture, often connotated with negative terms such as cronyism and favouritism that derive from the geographic or historical socio-political context. However, its connotations are wider than this simplistic definition. Some recent research depicts wasta, similar to other social networks such as guanxi and blat, as a common, if not necessary, way of doing business in the regions and cultures in which each practice prevails (Alwerthan et al., Reference Alwerthan, Swanson and Rogge2017; Gold & Naufal, Reference Gold and Naufal2012; Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006a, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006b). It could therefore be argued that Wasta is not just favouritism or corruption, but rather a part of the culture that creates cohesion in the countries of the Arab Middle East. In those countries, there is a strong and pervasive expectation that an individual will provide wasta to family, relatives, and friends whenever possible (Loewe et al., Reference Loewe, Blume and Speer2008), thereby demonstrating generosity and loyalty (Alwerthan et al., Reference Alwerthan, Swanson and Rogge2017). This is likely to be particularly true in tribal societies (e.g., Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, or Jordan) in which individuals who do not provide wasta may bring shame to themselves, their families and their tribes (Cunningham & Sarayrah, Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993).

Wasta is also a practice that was historically used to mediate between conflicting tribes, a use termed ‘intermediary Wasta’ (Cunningham & Sarayrah, Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993) or Sulh (Al-Ramahi, Reference Al-Ramahi2008). Subsequently, it was used to describe the achievement of a specific goal with the help of a patron (Cunningham & Sarayrah, Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993, Makhoul & Harrison, Reference Makhoul and Harrison2004; Mohamad & Mohamad, Reference Mohamed and Mohamed2011). Modern day intercessory wasta, referring to the use of an intermediary to secure a goal, is a widespread practice in the countries of the Arab world and is practised for a variety of reasons. It may be used for political aims, such as to achieve political influence or to win parliamentary elections (Al-Ramahi, Reference Al-Ramahi2008); for social aims, as in pre-arranged marriages, to help a male obtain the approval of a potential bride or her parents (Cunningham & Sarayrah, Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993); or for economic aims, to secure a job or promotion, or to cut through bureaucracy in government interactions (Loewe et al., Reference Loewe, Blume and Speer2008). It is important to point out, however, that these different aims are seldom disconnected and that an act of wasta might be fuelled by, or result in, a combination of these aims. Moreover, wasta can be a self-reinforcing process; the more it works, the stronger it gets, and what works in one context can strengthen the chances of its working in another sector (Cunningham & Sarayrah, Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993; Tucker & Bucton-Tucker, Reference Tucker and Bucton-Tucker2014b). Intercessory wasta is claimed to be a factor in every significant social and economic decision in the Arab world (Gold & Nuafal, Reference Gold and Naufal2012; Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006a).

The Gap in the Theoretical Understanding of Wasta

As highlighted above, there is now a substantial amount of research on guanxi that is exploring its origins, historic and current practice, ‘process’ and impacts on the political, social and economic spheres in China (Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006a; Velez-Calle et al., Reference Velez-Calle, Robledo-Ardila and Rodriguez-Rios2015). On the other hand, while as mentioned above the systematic review indicates that research on wasta has been improving in both quantity and rigor, it has not reached the quantity and depth of research on its Chinese counterpart, despite being a major factor in everyday and strategic business decisions in the countries of the Arab world (Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006a; Velez-Calle et al., Reference Velez-Calle, Robledo-Ardila and Rodriguez-Rios2015).

Some researchers provide a general description of the act of wasta and speculate on the possible positive or negative outcomes of its use (e.g., Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006a, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006b; Metcalfe, Reference Metcalfe2007; Tlass & Kauser, Reference Tlaiss and Kauser2011). Others offer a more detailed analysis of this practice using theoretical underpinnings such as social capital, attribution theory and institutional theory, limiting their focus to one country, business function, industry or context (e.g. Al-Ramahi, Reference Al-Ramahi2008; Cunningham & Sarayrah, Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993; Harbi et al., Reference Harbi, Thursfield and Bright2017; Loewe et al., Reference Loewe, Blume and Speer2008).

This fragmented body of knowledge of wasta, characterised by the use of limited data collected from narrow regional/sectoral areas and utilising a limited or mono-theoretical lens, has resulted in a lack of depth in the understanding of this complex phenomenon, leaving a gap in our knowledge of this practice and its impact on business processes in the region. The rest of this article addresses this knowledge gap by analysing wasta according to the main theoretical lenses through which it has been explored by previous researchers, thereby providing a holistic theoretical view of this practice that advances the research field and enables us to provide practical and theoretical recommendations based on these findings.

APPROACHES TO WASTA RESEARCH

Wasta is a phenomenon that manifests in a wide range of political, social, and business situations throughout the Arab Middle East. As a consequence, it has been explored by researchers from a variety of social science disciplines, including social development (e.g., Makhoul & Harrison, Reference Makhoul and Harrison2004), law (e.g., Al-Ramahi, Reference Al-Ramahi2008) and business, economics and human resources (e.g., Berger et al., Reference Berger, Silbiger, Herstein and Barnes2014; Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006a, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006b; Mohamed & Mohamad, Reference Mohamed and Mohamed2011). Many of these researchers have explored wasta through a mono-theoretical perspective, such as: institutional theory (16 identified publications, e.g., Barnett, Yandle, & Naufal, Reference Barnett, Yandle and Naufal2013; Brandstaetter, Reference Brandstaetter2011; Loewe et al., Reference Loewe, Blume and Speer2008; Sidani & Thornberry, Reference Sidani and Thornberry2013); attribution theory (one paper, Mohamed & Mohamad, Reference Mohamed and Mohamed2011); national culture theories (two papers, Aldossari & Robertson, Reference Aldossari and Robertson2015; Harbi et al., Reference Harbi, Thursfield and Bright2017); social networks (19 papers, e.g., Sefiani et al., Reference Sefiani, Davies, Bown and Kite2018); and social capital theory (15 papers, e.g., Bailey, Reference Bailey2012; El-Said & Harrigan, Reference El-Said and Harrigan2009; Tlaiss & Kauser, Reference Tlaiss and Kauser2011). Nevertheless, as highlighted in the sections above, much of the research exploring wasta has lacked theoretical rigour. To address this issue, Table 2 presents the publications that were identified as key influential research studies exploring wasta according to the institutional, social networks, and social capital theories which predominate in wasta research. The discussion of the literature will include all relevant articles identified in the literature review but will focus on these publications, as they have been identified as the most rigorous available from the extant literature and those that have substantially extended our theoretical knowledge of this practice.

The Institutional Approach

A major branch of research on wasta has used the institutionalist perspective to explore this practice (e.g., Al-Ramahi, Reference Al-Ramahi2008; Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, Yandle and Naufal2013; Cunningham & Sarayrah, Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993; Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006a; Loewe et al., Reference Loewe, Blume and Speer2008; Sidani & Thornberry, Reference Sidani and Thornberry2013; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Torres, Leong, Budhwar, Achoui and Lebedeva2012a). Researchers adopting this perspective have explored the origins of wasta: how this practice was historically used as a mechanism to access and distribute resources through informal institutions such as tribes, and the reasoning for this practice's continuous existence in the Arab Middle East, where institutional voids exist and formal institutions are weak or almost non-existent (Cunningham & Sarayrah, Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993; Loewe et al., Reference Loewe, Blume and Speer2008; Sidani & Thornberry, Reference Sidani and Thornberry2013; Tucker & Bucton-Tucker, Reference Tucker and Bucton-Tucker2014a, Reference Tucker and Bucton-Tucker2014b). As such, research exploring Wasta from the institutional perspective has been important for deepening our understanding of the function wasta serves as a source and regulator of resources when formal governing institutions are absent or weak. Some institutional researchers, however, can be criticised for focusing on the negative aspects of wasta, as many have treated wasta as an inefficient practice that needs to be replaced by formal, more efficient institutions (Loewe et al., Reference Loewe, Blume and Speer2008).

The Social Capital and Social Networks Approaches

Researchers adopting the social networks and social capital perspectives (e.g., Albin Shaikh et al., Reference Albin Shaikh, Purchase and Brush2019; Aljbour et al., Reference Aljbour, Hanson and El-Shalkamy2013; Bailey, Reference Bailey2012; Berger et al., Reference Berger, Silbiger, Herstein and Barnes2014; El-Said & Harrigan, Reference El-Said and Harrigan2009; Fawzi & Almarshed, Reference Fawzi and Almarshed2013; Gold & Naufal, Reference Gold and Naufal2012; Harbi et al., Reference Harbi, Thursfield and Bright2017; Tlaiss & Kauser, Reference Tlaiss and Kauser2011;) fundamentally view wasta as an aspect of social networks building social capital. This is especially prevalent in Arab Middle Eastern countries such as Jordan (El-Said & Harrigan, Reference El-Said and Harrigan2009), Lebanon (Tlaiss & Kauser, Reference Tlaiss and Kauser2011), the United Arab Emirates (Bailey, Reference Bailey2012), and Saudi Arabia (Albin Shaikh et al., Reference Albin Shaikh, Purchase and Brush2019; Fawzi & Almarshed, Reference Fawzi and Almarshed2013). Although some researchers clearly highlight that they have used either social network theory (e.g., Abalkhail & Allan, 2015; Berger et al., Reference Berger, Silbiger, Herstein and Barnes2014) or social capital theory (e.g., Albin Shaikhet al., Reference Albin Shaikh, Purchase and Brush2019; Bailey, Reference Bailey2012) in exploring wasta, many have drawn on elements of both these inherently related theories in exploring this practice (although one theory may prevail in their analysis). Moreover, there is a consensus among these researchers that wasta should be treated as a form of currency that favours exchange between individuals and that is neither innately positive nor negative, but which might produce outcomes that are positive or negative. Because of this common analysis and view of wasta, this review groups together research using both these lenses.

Table 4. Summary of key influential wasta research

Other Lenses Used to Explore Wasta

Interestingly, although there is no research that explores wasta solely from an identity perspective, many studies have used identity as a complementary lens alongside social capital or institutional lenses (e.g., Bailey, Reference Bailey2012; Metcalfe, Reference Metcalfe2007). It is important to note that, even though researchers have used middle-range theories such as attribution theory (Mohamed & Mohamad, Reference Mohamed and Mohamed2011) and modernization theory (Sabri & Bernick, Reference Sabri and Bernick2014) to explore wasta, the scale and scope of research using the institutional, social networks and social capital lenses to explore wasta has been substantially wider. Research using these lenses will therefore be explored in detail to achieve a comprehensive view of our current understanding of wasta.

KEY APPROACHES TO WASTA RESEARCH

Wasta from the Institutional Perspective

Institutional theory has become a dominant theory for exploring economics and management at the macro level and has been used to explain actions at the governmental, organisational, and individual levels (Greenwood, Oliver, Sahlin, & Suddaby, Reference Greenwood, Oliver, Sahlin and Suddaby2008). At the macro (societal) level, this theory explains how the macro environment and the events that occur lead to the development of cultural ideas that evolve over time and become legitimised within a society and its institutions (Eisenhardt, 1988). Kostova, Roth, and Dacin (Reference Kostova, Roth and Dacin2008) further explain this notion through highlighting that institutional arrangements are shaped by a country's national culture and are therefore country specific. This view proposes that certain cultural practices, including wasta in this case, are developed and normalised by national culture which, as it develops, constantly influences these institutional arrangements (El-Said & Harrigan, Reference El-Said and Harrigan2009; Sidani & Thornberry, Reference Sidani and Thornberry2013). Thus, institutionalists who have studied wasta argue that it is a result of the social context of institutions, which shapes the institutions and individuals’ actions (Sidani & Thornberry, Reference Sidani and Thornberry2013).

The historical development of wasta: The institutional perspective

In exploring the origin of the practice of wasta, Cunningham and Sarayrah (Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993) highlighted the dominant ‘intermediary’ use of wasta by tribal leaders who mediated between two fighting tribes to reconcile them and achieve sulh (reconciliation) (Al-Ramahi, Reference Al-Ramahi2008). Cunningham and Sarayrah (Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993) and El-Said and Harrigan (Reference El-Said and Harrigan2009) also explore the other ‘intercessory’ use of wasta: using mediation to achieve a goal or access resources in the British mandate of Palestine and Transjordan in the 1920s and 1930s. The research highlights how wasta was used by Prince Abdullah and allied British leaders as a mechanism of control through providing tribe leaders with access to resources and jobs. These tribe leaders then acted as mediators (Waseet), redistributing these resources to their tribe members. The tribal leaders attained and maintained power and legitimacy through this process and Prince Abdullah and his allies maintained these leaders’ allegiance. In this situation, the process of wasta was operationalised in the informal institutions of the tribes, so replacing the function of weak, newly developed formal institutions of the new state of Transjordan. Similar processes occurred in other countries of the Arab Middle East (Cunningham & Sarayrah, Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993).

In modern times, although tribal governance has given way to official government institutions in most aspects of life in the countries of the Arab Middle East, intercessory wasta remains a powerful method for attaining resources as people perceive the formal institutions as weak and focused on self-benefit, and they see the short-term benefit of wasta for its participants (Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, Yandle and Naufal2013; Sidani & Thornberry, Reference Sidani and Thornberry2013).

The institutional view on wasta in organisations

El-Said and Harrigan (Reference El-Said and Harrigan2009) explored the development of wasta through associating it with the negative trope of nepotism. Although the authors described wasta as a form of social capital, they drew on elements of institutional theory, particularly the concepts of organisational legitimacy and trust (see Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Oliver, Sahlin and Suddaby2008 for a detailed exploration of these concepts) to explore how this practice persisted and evolved in society. The authors used the concept of pragmatic legitimacy (viewed as achieving the self- interests of the organisation's members and their close in-groups) to explain how wasta first became institutionalised and was then maintained as society developed. The authors argue that, in the case of wasta, the organisation's most immediate set of users and beneficiaries comprises the families and tribe members of the owners, managers and employees, and such a practice corresponds well with their interests (El-Said & Harrigan, Reference El-Said and Harrigan2009). From these users’ perspective, a business firm that avoids practising wasta is not fulfilling an important aspect of achieving group coherence and benefiting the members of the group (Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, Yandle and Naufal2013; El- Said & Harrigan, Reference El-Said and Harrigan2009).

The second aspect discussed by institutionalists studying wasta is trust. Fukuyama (Reference Fukuyama1996) argued that societies need large amounts of generalised trust in order to prosper. When formal governmental institutions are not able to obtain this level of trust from the members of society, then other, informal institutions, such as those involving family or tribe members, assume prominence (Fukuyama, Reference Fukuyama1996; Herreros & Criado, Reference Herreros and Criado2008). This is the case when governments act arbitrarily and lack accountability or transparency, and when legal systems provide little protection for private property or contract enforcement (Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, Yandle and Naufal2013; El-Said & Harrigan, Reference El-Said and Harrigan2009). This lack of a supportive institutional framework forces people to lean back on the family (Xin & Pearce, Reference Xin and Pearce1996). Throughout much of the Arab Middle East, authors have argued that generalised social trust, that is, the willingness to extend a degree of trust to people outside the extended family, is severely limited (El-Said & Harrigan, Reference El-Said and Harrigan2009). In such an environment, it becomes clearer why reliance on wasta provided by family members and trusted friends becomes the default solution to achieving goals such as seeking employment (Cunningham & Sarayrah, Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993; Loewe et al., Reference Loewe, Blume and Speer2008; Sidani & Thornberry, Reference Sidani and Thornberry2013).

Due to the pragmatic legitimacy of wasta as a beneficial practice for the group, and the concentration of trust in familial and friendship groups, wasta makes pragmatic sense; it is a symptom of state institutions that did not, historically, develop well. From this point of view, such practices are necessary as a competitive weapon for a firm to position itself on an equal or better footing than others; wasta becomes a gateway to better competitiveness in an environment where everybody else is trying to do the same (El- Said & Harrigan, Reference El-Said and Harrigan2009; Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, Yandle and Naufal2013). This highlights the benefit of wasta for the individuals using it; it provides them with access to information and resources using their in-group connections. It also highlights the benefit for institutions that achieve high levels of coherence and trust, leading to cohesive work environments, increased levels of trust between employers and employees, reduced levels of absenteeism and employee turnover, and the ability to mobilise employees’ connections to attract new, loyal employees (Alwerthan et al., Reference Alwerthan, Swanson and Rogge2017; Cuningham & Sarayrah, Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993; Loewe et al., Reference Loewe, Blume and Speer2008).

However, institutionalists studying wasta also highlight the negative aspects of the use of wasta as a mechanism to distribute resources as it restricts the allocation of such resources to in-groups through binding social relations that concentrate access to resources in these groups and exclude others (see El-Said & Harrigan, Reference El-Said and Harrigan2009, and Sidani & Thornberry, Reference Sidani and Thornberry2013, for more detail). This negative aspect of using wasta has been the focus of many institutional researchers, who argue that this parallel informal system is time consuming, costly, and lacks ethical justice as it provides individuals with rent-seeking abilities and favours people who have access to wasta over those who do not (Loewe et al., Reference Loewe, Blume and Speer2008). In the business environment. Loewe et al. (Reference Loewe, Blume and Speer2008) highlight negative outcomes of using wasta, which include reduced organisational productivity, lack of diversity, and increased inequality in organisations and society, leading to the reinforcement of localised power in particular established groups. Finally, Loewe et al. (Reference Loewe, Blume and Speer2008) argue that the prevalence of wasta maintains the weakness of the formal institutional framework by reducing trust in the political and legal institutions.

Most researchers adopting this view highlight how wasta and similar informal systems are only sustainable while they continue to make ‘economic sense’ to their practitioners and will eventually be replaced by more efficient formal institutions as further economic and technological developments occur (Loewe et al., Reference Loewe, Blume and Speer2008; Sidani & Thornberry, Reference Sidani and Thornberry2013). This process might have a ‘cultural lag’, where individuals within society continue to practise wasta for some time even after developments enable more economically sensible alternatives (Sidani & Thornberry, Reference Sidani and Thornberry2013).

A conceptual model for the institutional view of wasta

Based on the discussion of research exploring wasta through the institutional lens presented earlier in this section, we now propose a conceptual model of how wasta is viewed by institutional theory.

This model highlights the institutionalist focus on the influence of the macro environment, that is, national culture and the formal institutions of state, on wasta. Groups A and B represent different social groups. These could be organisations, families, tribes or different social groups in which people identify with each other. As highlighted in the discussion above, there could be further combinations among these groups, as members of the same organisation are often members of the same family or tribe (Cuningham & Sarayrah, Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993; El- Said & Harrigan, Reference El-Said and Harrigan2009; Sidani & Thornberry, Reference Sidani and Thornberry2013). Institutionalists studying wasta have focused on the relationships among the members of each group and how, through using wasta to attain their goals, the groups react to external events and occurrences. These relationships are characterised by a high degree of trust and reciprocity among members (Sidani & Thornberry, Reference Sidani and Thornberry2013). When external events such as economic or political difficulties happen, and in the absence of strong formal institutions, these relationships and the bonds between these groups are strengthened, in part by excluding others (El- Said & Harrigan, Reference El-Said and Harrigan2009).

Researchers of wasta from the institutional perspective highlight how this situation persists until other, more efficient ways of gaining resources become available to the members of these groups (Sidani & Thornberry, Reference Sidani and Thornberry2013). This highlights the institutionalist focus on the macro view of the ‘group’ or the ‘wasta network’, thereby exploring the dynamics of the network's reaction to the external environment. It also highlights how these researchers view wasta as an inefficient practice that will eventually be replaced by more efficient institutions, thus neglecting its embeddedness in culture.

Figure 1. Conceptual model of wasta from an institutional perspective.

Wasta from Social Networks and Social Capital Perspectives

Social capital, roughly defined as the value that exists in the connections between individuals, is directly related to social networks, as social capital exists in the structure of network relationships (Burt, Reference Burt, Lin, Cook and Burt2001; Coleman, Reference Coleman1988, Reference Coleman1990; Li, Reference Li2007; Lin, Reference Lin2001; Putnam,1993). It consists of aggregated resources linked to the possession of a durable network of mutual acquaintance and recognition (Bourdieu & Wacquant, Reference Bourdieu and Wacquant1992). Social capital researchers have mainly classified it according to two types. The first is bonding social capital, which flows in ‘strong ties’ between members of the same group or network and helps these members to ‘get by’ by providing them with strong support from members of the same network. The second is bridging social capital, which flows in ‘weak ties’ between members of different groups and help these individuals in ‘getting ahead’, as these ties bridge the gap between the two networks and help information pass over what Burt (Reference Burt1992) calls a ‘structural hole’ (Burt, Reference Burt1992; Gittel & Vidal, Reference Gittell and Vidal1998; Granovetter, Reference Granovetter2005).

Burt (Reference Burt2000, Reference Burt2005) identified the role of an information broker, who is a member of one group or network but possesses a tie with a member or members of another group. These ties enable the broker to carry information from one network to another, across what are termed ‘structural holes’ between networks. These structural holes are the ‘vacuum’ between groups, where members do not have ties with each other. Brokerage is deemed most useful when the groups that are linked together are closed or relatively closed. This is because the broker provides new information and access to resources which were not available to members of the other group. This situation is also beneficial for the broker, as the possession of ties becomes valuable, particularly when few other brokers possess ties between the two groups (Burt, Reference Burt2005). The broker will be in a powerful position where he or she can exchange the benefits needed by others for resources (Cullinane & Dundon, Reference Cullinane and Dundon2006), or can influence and control the other members of the network who require such benefits (Blau, Reference Blau1964; Watson, Reference Watson2002). The more closed the social networks are, the more powerful the broker becomes (Granovetter, Reference Granovetter1973).

Wasta from a social capital and social networks perspective

Wasta researchers from the social networks and social capital perspectives have focused on the relationships between the members of the networks (e.g. Albin Shaikh et al., Reference Albin Shaikh, Purchase and Brush2019; Sefiani et al., Reference Sefiani, Davies, Bown and Kite2018). Their focus has therefore been mainly on the micro (individual) level and how these relationships can bring benefits and drawbacks to those involved and the people around them (Aljbour et al., Reference Aljbour, Hanson and El-Shalkamy2013; Bailey, Reference Bailey2012; Berger et al., Reference Berger, Silbiger, Herstein and Barnes2014; Gold & Naufal, Reference Gold and Naufal2012; Fawzi & Almarshed, Reference Fawzi and Almarshed2013; Tlaiss & Kauser, Reference Tlaiss and Kauser2011). Wasta can be beneficial for individuals seeking employment, as mediating between parties through a wasta intervention between the job seeker and an organisation can help a qualified individual to secure a job (Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006b). This benefit extends to organisations, which can use wasta to secure qualified and loyal employees when certain skills are lacking (Mann, Reference Mann2013, Reference Mann2014). Wasta provision is associated with higher levels of need satisfaction and correspondingly lower levels of distress (Alwerthan, Reference Alwerthan2016; Alwerthan et al., Reference Alwerthan, Swanson and Rogge2017). However, wasta can have negative aspects, both for its practitioners and for others. Wasta can give an unfair advantage to people who have it and can prevent those without it from gaining fair access to public bids or to jobs in public and private organisations (Loewe et al., Reference Loewe, Blume and Speer2008). Although some people may benefit from wasta by using it to attain a job, they may also, because of using it, suffer from being viewed as inadequate and/or immoral by their peers and the wider society (Mohamed & Mohamad, Reference Mohamed and Mohamed2011). In addition, there are also negative links between being on the receiving end of wasta and psychological distress; those who have benefitted from wasta in securing jobs show higher levels of psychological distress, explained in part by lower levels of autonomy, competence and relatedness to others (Alwerthan et al., Reference Alwerthan, Swanson and Rogge2017).

In addition to extending our understanding of the benefits and drawbacks of using wasta at the individual level, researchers exploring wasta from the social capital perspective have also deepened our understanding of the types of wasta relationships among individuals. In exploring social capital between East Bank and West Bank Jordanians, El- Said and Harrigan (Reference El-Said and Harrigan2009) applied the concept of bonding and bridging social capital to wasta, so highlighting how the bonding social capital type of wasta used among Palestinian Jordanians helped them to ‘get by’ in difficult economic and social times; while bridging social capital, the type of wasta used between East Bank Jordanians and Palestinian Jordanians, helped the later ‘get ahead’ using these weak ties. The social capital lens also helps in understanding the role of the individual acting as a wasta broker (or waseet) between the parties requesting and providing wasta favours. Indeed, Burt's (Reference Burt2000, Reference Burt2005) exploration of the role of the information broker is reflected in the role in the wasta process of the waseet, who can benefit from the network by mediating between parties and gaining different forms of capital (financial, social, or human) for their own use. Indeed, Al-Ramahi (Reference Al-Ramahi2008) and Berger et al., (2004) highlight how acting as a waseet can bring pride and respect (forms of human capital) to the waseet, who will thus acquire good standing (or sumah), which in turn cultivates further access to wasta. Moreover, a waseet may continue to be respected even (or perhaps especially) if she/he does not appear to have benefited from a negotiated outcome in which their role has been significant (Cunningham & Saryarah, Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993). It can be therefore be deduced that the power of a waseet may be latent and thus less easily quantified.

A conceptual model for wasta from a social capital perspective

Based on previous researchers who adopted social networks and social capital as lenses through which to view wasta, we developed the model shown in Figure 2, which depicts wasta from the social networks and social capital perspectives.

Figure 2. Wasta from a social networks and social capital perspectives.

This model reflects the focus on the individual level of wasta and the movement of social capital in the relations within and between groups. Each circle highlights the different bonding groups, such as families or tribes. The arrows show connections among individuals inside the groups; these are characterised by strong relationships, typical of bonding social capital. The dashed arrows between the circles represent the weaker ties between members of different groups. These ties contain bridging social capital, which is likely to present new and unique information. As such, group members A3, B1, B3, C1, and C2 are information brokers who can act as waseet not only to members of their own group, but to members of different groups, so gaining access to more capital and wasta themselves. A point often neglected by wasta researchers is that this process is not always straightforward, where one waseet mediates between two individuals (as in the case of B1 mediating between C1 and A3) (Cuningham & Sarayrah, Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993); in fact, the process can have several waseets connected through both bonding and bridging social capital (as in the case when A2 wants a favour from C3 using B1 and C1 as mediators). It is worth noting that this ‘complex’ wasta means that the individual requesting the favour has several routes that he/she could utilise and that often several ‘routes’ could be used simultaneously (Cunningham & Sarayrah, Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993).

DISCUSSION

The arguments presented above highlight the added depth offered by viewing wasta through each theoretical lens. However, using a single theory to explore such a phenomenon can be argued to have resulted in a simplistic view. We suggest that wasta is a more complex process than the literature often recognises.

Viewing wasta from the institutional perspective helps in understanding this practice at the macro level and its importance where informal institutions are necessary, or are culturally and economically preferred to the use of formal institutions (El-Said & Harrigan, Reference El-Said and Harrigan2009). Institutional research also highlights that reliance on wasta for attaining and distributing resources comes with the risks of rent-seeking and the creation of concentrated power pockets in society (ibid.). At the organisational level, wasta can lead to a lack of organisational productivity, a lack of diversity, and increased inequality (Loewe et al., Reference Loewe, Blume and Speer2008). However, this line of research can be criticised for focusing on the negative outcomes of wasta and would benefit from a more balanced approach.

The social networks and social capital lenses help us to understand the micro level of wasta among the members of the same and different groups. Using the bonding and bridging social capital dichotomy, we suggest that, similar to the way in which Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Chen and Huang2013) differentiates guanxi into different levels, the process of wasta can be divided into different levels. Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Chen and Huang2013) distinguish Shengren guanxi (guanxi with a stranger); Shuren guanxi (guanxi with a known person); and Qinren guanxi (guanxi with family members or strongly connected persons). We propose, for wasta: bonding social capital wasta (used as bonding social capital in ties between members of close-knit groups such as family or tribe members) and bridging social capital wasta (wasta used in weaker bridging ties among members of different groups such as friends). Moreover, a combination of these strong and weak ties could be used in the same wasta request using different information brokers (waseets). These forms of wasta capital are exchanged between the different actors: the individual requesting wasta, the intermediate (or information broker/waseet) and the person granting wasta. It is suggested that, similar to guanxi, the tie or bond and the level of trust and commitment increase as the wasta moves to the next level (Fu, Tsui, & Dess, Reference Fu, Tsui and Dess2006). Qi (Reference Qi2013) names this the Reinforcement Effect.

It is important to note, however, that the type of tie used does not imply a particular outcome, negative or positive: rather, this depends on other, complex inputs into the process, for example, the qualification or fit of a candidate with the job when wasta is used in employee selection, or the circumstances and motives for accepting a wasta request (see Ali, Reference Ali2016, for a detailed exploration of this issue).

Based on this understanding of wasta through both the institutional and social capital lenses, Figure 3 presents a holistic conceptual model of wasta.

Figure 3. A holistic model of wasta

This article contributes to our comprehension in three ways. It helps in understanding wasta on both the micro- and macro-levels, and provides a holistic view of this practice that bridges the micro–macro divide.

Contribution to Understanding Wasta at the Micro-Level

At the micro-level, that is, social networks and social capital views, the model advances our understanding of this practice by highlighting the complex nature of internal relationships in wasta networks and the social capital that flows through them. The model highlights that wasta can require the mobilisation of both bonding social capital between members of the same group (such as in the tie between C1 and C3); bridging social capital between members of different groups (such as in the tie between B1 and C1); or a combination of both (such as in the ties between A3 and C1, which could take several possible routes). In doing so, it also sheds light on the role of the waseet as an information broker, thus highlighting that the social capital to which the operation of wasta adds is an asset that benefits not only the receiving party, but also the other parties involved in granting and facilitating it, and it thus becomes a network asset. Future researchers exploring wasta from the social networks and social capital perspectives could build on this by investigating the complex interactions in wasta requests that mobilise both bonding and bridging social capital. Deeper exploration of the role of the waseet in the wasta process is also necessary, and the final section of this article suggests specific avenues for research on this issue.

Contribution to Understanding Wasta at the Macro Level

The model links the complex relations revealed by exploring wasta on the micro level to the macro-institutional level, which reflects wasta as a product of informal institutions such as tribes that interact dynamically with the external social, political and economic environment and the formal institutions. Our exploration of wasta from an institutional perspective responds to the simplistic, frequently negative, view often adopted by institutionalists studying wasta that it is an unethical practice, reflective of cronyism or corruption, that will eventually be replaced by more efficient practices as institutions evolve. In doing so, this article contributes to our understanding of social networks not only as informal institutions that replace inefficient or ineffective social institutions, but also as social structures that are pragmatically necessary and sometimes preferred to formal ways of governing and distributing resources.

Such dilemmas may appear readily soluble to the theorist bound in a framework of rational economic action and competitive frameworks of market and state action. By reflecting the network aspect of wasta, the discussion and resulting model help us to understand that wasta is a practice that, while it may have negative outcomes for its practitioners and the wider society in some instances, is pragmatically needed in a market in which formal institutions are weakened and which is a tumult of bargains rather than a structure of definitely preferable outcomes.

Future researchers of wasta who take an institutional perspective are encouraged to build on the ethos of this article by adopting an emic and indigenous view of wasta. We urge them to take into consideration the instrumental (economic) and sentimental (social) logics of wasta practitioners and the societies where it prevails. This will allow us to move away from the simple view, held by many institutionalist researchers, of the practice as favouritism, cronyism and corruption, while still maintaining a balance with the views of many social networks and social capital researchers, who often neglect the ‘dark side’ of this practice and the complex mixture of bonding and bridging social ties involved in some wasta transactions. Avenues of research could include exploring how the instrumental (economic) and sentimental (social) logics behind wasta are achieved and maintained within and between networks. Another question to explore is, how do the wasta process dynamics change with the development of the different societies and the micro and macro environments in which this practice prevails?

Contribution to the Holistic View of Wasta

In combining the different views of wasta provided by researchers adopting the institutional, social capital, and social networks theories, the model's major contribution is in bridging the micro–macro divide in viewing wasta, so helping us to understand wasta as including the network itself; the ties between members inside it; and the capital that resides in and moves through these ties. Through understanding wasta as a whole, we can better understand the dynamic relationship between the network and the outside macro environment and how the ‘type’ and ‘intensity’ of ties influence and are influenced by the macro environment.

Through this linkage, the model highlights how wasta ties and their use are strengthened where formal institutions are weak and where it is ‘logical’ or ‘economic’ to use wasta rather than to rely on inefficient or ineffective formal processes and institutions, or when social divisions make access to these difficult (Cuningham & Sarayrah, Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993; El- Said & Harrigan, Reference El-Said and Harrigan2009; Sidani & Thornberry, Reference Sidani and Thornberry2013). Moreover, the type of wasta ties predominantly used is dependent on the particular macro-environment (bonding wasta, used to ‘get by’, is more prevalent in harsh economic times, while bridging wasta, used to ‘get ahead’, is more prevalent in good political and economic times) (El- Said & Harrigan, Reference El-Said and Harrigan2009).

Through bridging the micro–macro divide, this model also helps us to understand the outcomes of wasta in a more holistic way. For individuals, wasta can provide a form of benefit (capital) for the different stakeholders in the network (the individual requesting wasta, those acting as waseet(s) and the individual providing it) (Berger et al., 2004). However, these benefits might come at a price, as wasta may also have negative consequences for the individual using it, such as causing psychological distress (Alwerthan et al., Reference Alwerthan, Swanson and Rogge2017) or being viewed as unqualified by others when used to attain employment (Mohamad & Mohamad, Reference Mohamed and Mohamed2011). Moreover, using wasta has negative impacts on other individuals at the micro level, such as missing out on opportunities for benefits because other people have used wasta to get them (Cuningham & Sarayrah, Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993) and providing waseets with rent-seeking possibilities (Loewe et al., Reference Loewe, Blume and Speer2008). Wasta's use by individuals can also impact the wider group and society, including by reducing organisational productivity, decreasing diversity and increasing inequality in organisations and society, thus leading to the reinforcement of power pockets for particular established groups (Loewe et al., Reference Loewe, Blume and Speer2008). However, wasta's outcomes for society are not solely negative, as the ability to cultivate trust through the practice of wasta has benefits at the macro level. For instance, in the business context, trust generated by the reinforcing nature of wasta can lead to cohesive work environments, increased levels of trust between employers and employees, reduced levels of absenteeism and employee turnover, and the ability to mobilise employees’ connections to attain new, loyal employees (Alwerthan et al., Reference Alwerthan, Swanson and Rogge2017; Cuningham & Sarayrah, Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993; Loewe et al., Reference Loewe, Blume and Speer2008). Future researchers of wasta might want to explore the interlinks between the benefits of wasta to its practitioners and its drawbacks for them and other stakeholders.

The benefits of our model in explaining the dynamic relationship between the actors involved in wasta (the individual requesting it, the waseet and the individual granting it) and the network and external environment go beyond this topic to respond to the call to address what is described as a ‘pervasive problem’ in the social sciences – the so-called ‘micro-to-macro problem’. This concerns our capacity to explain the relationships between the constitutive elements of social systems (people) and emergent phenomena resulting from their interaction (such as organisations, societies and economies) (Goldspink & Kay, Reference Goldspink and Kay2004; Kuhn, Reference Kuhn2012). Followers of this line of thought highlight that, without the capacity to explain this relationship, there is, in effect, no substantive theory of sociality (Goldspink & Kay, Reference Goldspink and Kay2004), thus reinforcing the need to look at wasta in a holistic way.

Suggestions for Practitioners

The findings can be used to help practitioners, particularly those who are unfamiliar with the culture of the countries of the Arab Middle East, to operate successfully in the context of wasta. We provide three recommendations.

First, the review of the literature on wasta demonstrates that this practice essentially operates in a context of complexity, diversity and a multiplicity of potential strategies. In these conditions, wasta offers an open-ended approach to organisational and business dilemmas in which the opportunity for the co-evolution of acceptable outcomes is often of greater significance than the achievement of a perfect solution. In the countries of the Arab Middle East (and perhaps more generally, if comparative research confirms this), practitioners rarely encounter framing expectations such as those implied by rational actor frameworks. The only certainty is uncertainty, and it may turn out that there is no better outcome than one that proves to be temporarily acceptable to the main actors. The market is a tumult of bargains rather than a structure of definitely preferable outcomes. In these conditions, the pejorative labelling discourse using notions of ‘cronyism’ or ‘corruption’ adds little to our understanding of the processes supporting viable actions and supportable outcomes. ‘Outsiders’ who wish to operate in these societies have to approach wasta pragmatically, being open to participating in the exchange of favours and the development of their own wasta networks, while remaining cautious of crossing any ethical or legal boundaries.

Second, it is important to realise that the social capital to which the operation of wasta adds is an asset that is not valuable until it is triggered through social action, and exists as much in its latency as in any exact present exchange value. Actors who wish to use their wasta connections must be active in doing so, and they should also avoid the quid pro quo mentality as wasta networks take time to develop and the ‘return’ is not always in the same type of capital. It is worth remembering that, in order to develop wasta, an individual will need to act as a waseet in several instances in order to become part of a wasta network.

Third, as wasta networks are in practice never closed, but are continuously evolving, giving off soft signals rather than generating definite and predictable quantities, they represent a potential for organisational and individual learning. It takes time to develop wasta networks, to be able to identify who can act as a waseet in different situations and to understand how to create a strategy for and structure a wasta ‘transaction’.

Limitations and Future Research Implications

The main limitation of this article lies in the fact that it had to build on scarce high-quality theoretical research on wasta, with few primary studies comparing wasta in the different countries of the Arab Middle East. As stated earlier, much of the extant literature on Wasta has framed the research agenda according to mono-theoretical lenses consisting mainly of the institutional, social networks, and social capital theories. In response to the limitations of previous research, future researchers of wasta could build their research on the holistic model developed here that encompasses the micro and macro aspects of wasta networks. This is consistent with calls to bridge the micro–macro divide in management research. It also ensures capturing the complexity of the wasta process, which aligns with the call of this special issue of Management and Organization Review to take a holistic and more inclusive view of informal networks.

We suggest that research can further explore the ‘black box’ of wasta interactions between the party requesting wasta, the waseet(s), and the party granting wasta. This recommendation also springs from the fact that there is little empirical knowledge about the different instrumental and sentimental motivations of the waseet to intermediate in the wasta process; how these decisions to intermediate are taken; the ways in which the waseet(s) navigate the requests within the complex bridging and bonding ties in and between networks; or the ways in which the waseet ‘operationalises’ the capital gained by granting wasta requests to create a network asset. Specific avenues of research include exploring questions such as: what motivates an individual to be a waseet in the wasta process? How do waseets assess the decision to act as such, and how do they go about connecting to the different wasta parties within and between complex networks? How do waseets assess the capital attained through granting wasta requests? And how can this capital be mobilised through the different complex networks? In exploring these questions researchers should take into consideration how these interactions are impacted by the macro social, political and economic environment. We suggest that in-depth case qualitative studies will be particularly beneficial for these purposes.