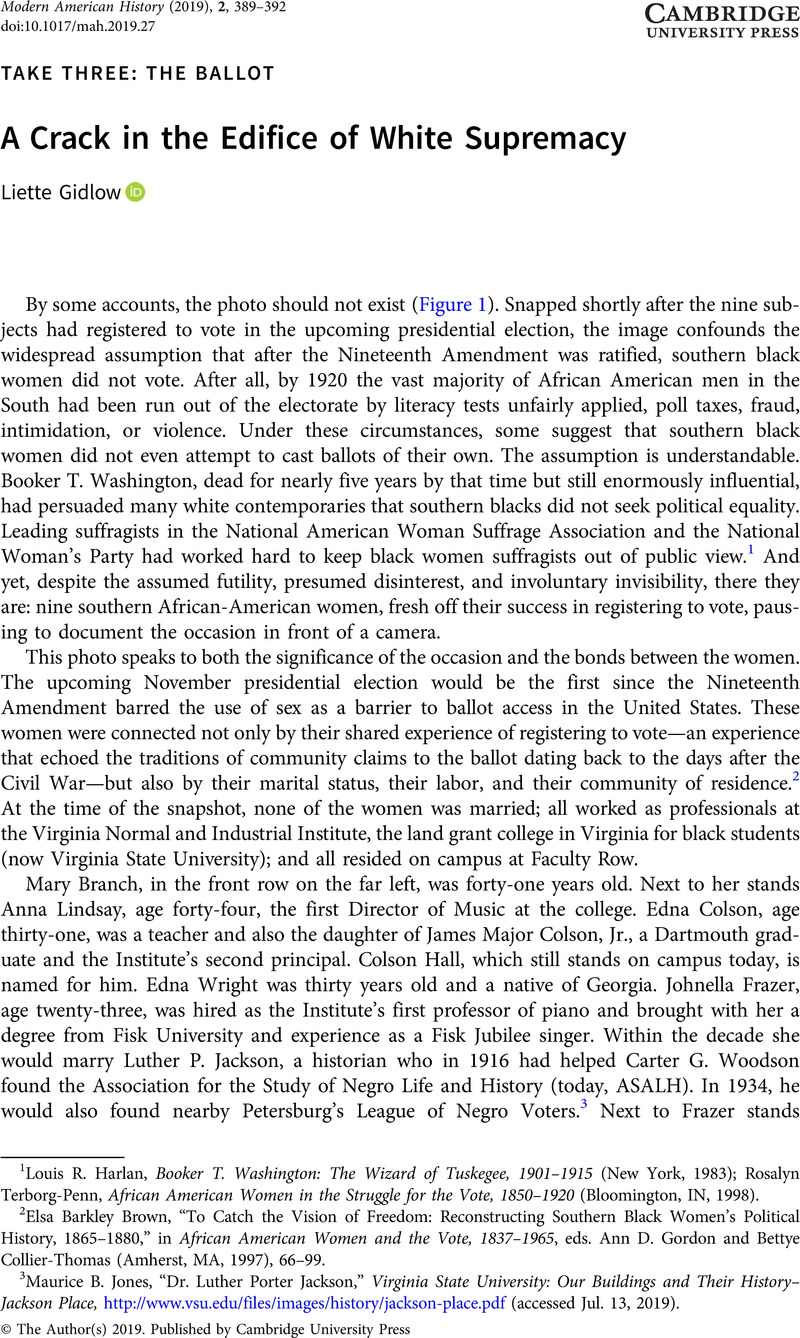

By some accounts, the photo should not exist (Figure 1). Snapped shortly after the nine subjects had registered to vote in the upcoming presidential election, the image confounds the widespread assumption that after the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified, southern black women did not vote. After all, by 1920 the vast majority of African American men in the South had been run out of the electorate by literacy tests unfairly applied, poll taxes, fraud, intimidation, or violence. Under these circumstances, some suggest that southern black women did not even attempt to cast ballots of their own. The assumption is understandable. Booker T. Washington, dead for nearly five years by that time but still enormously influential, had persuaded many white contemporaries that southern blacks did not seek political equality. Leading suffragists in the National American Woman Suffrage Association and the National Woman's Party had worked hard to keep black women suffragists out of public view.Footnote 1 And yet, despite the assumed futility, presumed disinterest, and involuntary invisibility, there they are: nine southern African-American women, fresh off their success in registering to vote, pausing to document the occasion in front of a camera.

Figure 1. “First Colored Women Voters Club of Ettrick, Virginia,” October, 1920. Courtesy of the Virginia State University Special Collections and Archives.

This photo speaks to both the significance of the occasion and the bonds between the women. The upcoming November presidential election would be the first since the Nineteenth Amendment barred the use of sex as a barrier to ballot access in the United States. These women were connected not only by their shared experience of registering to vote—an experience that echoed the traditions of community claims to the ballot dating back to the days after the Civil War—but also by their marital status, their labor, and their community of residence.Footnote 2 At the time of the snapshot, none of the women was married; all worked as professionals at the Virginia Normal and Industrial Institute, the land grant college in Virginia for black students (now Virginia State University); and all resided on campus at Faculty Row.

Mary Branch, in the front row on the far left, was forty-one years old. Next to her stands Anna Lindsay, age forty-four, the first Director of Music at the college. Edna Colson, age thirty-one, was a teacher and also the daughter of James Major Colson, Jr., a Dartmouth graduate and the Institute's second principal. Colson Hall, which still stands on campus today, is named for him. Edna Wright was thirty years old and a native of Georgia. Johnella Frazer, age twenty-three, was hired as the Institute's first professor of piano and brought with her a degree from Fisk University and experience as a Fisk Jubilee singer. Within the decade she would marry Luther P. Jackson, a historian who in 1916 had helped Carter G. Woodson found the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (today, ASALH). In 1934, he would also found nearby Petersburg's League of Negro Voters.Footnote 3 Next to Frazer stands Nannie Nichols, born in Georgia, who was twenty-seven years of age. In the back row on the left stands Eva Conner, age twenty-six, from South Carolina; Evia Carpenter, age thirty-one, a teacher; and (Beatrice) Odelle Grein, age twenty-four, a librarian at the college.

There they are. Nor were they the only ones, for other archives reveal that a great many black women in the Jim Crow South tried to register and vote after ratification. Most, it seems, were defrauded or rebuffed—new victims of disfranchising tactics perfected by white supremacists in the decades since the Civil War. But in some locations, a few, and sometimes more than a few, succeeded in casting ballots.Footnote 4 With their persistent attempts and sometimes with their votes, southern black women chiseled a crack in the edifice of white supremacy. Within a century, their votes changed the course of American history.

White supremacists feared black women's votes. As Congress debated whether to send the federal amendment to the states, and then as states debated whether to ratify it, they repeatedly said so. Black women, they believed, would vote in great numbers and even outnumber white women at the polls. The Macon, Georgia Daily-Telegraph, for example, reported that local black women were “clamoring” for the vote as state legislatures in the summer of 1920 were deciding whether to ratify.Footnote 5 The historian Kenneth R. Johnson reviewed a range of southern white newspapers and anti-suffrage publications from the 1910s and came to the same conclusion. “It was widely believed,” Johnson observed, that “Negro women wanted the ballot more than white women [and they] were expected to register and vote in large numbers if given the opportunity.”Footnote 6

Worse yet, white supremacists feared that enfranchising black women might open up opportunities for the return of black men to the polls. In Richmond in 1915, the Evening Journal expressed that fear not far from the Virginia Normal and Industrial Institute itself. If the Anthony Amendment was ratified, the editors warned, “twenty-nine counties will go under negro rule,” a situation that would compel the men of Virginia to return to defending white supremacy through fraud and violence, to “return to the slimepit from which we dug ourselves.”Footnote 7 A writer from Georgia shared that opinion in a piece published in the Woman Patriot, the official publication of the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage. “To ratify the double suffrage amendment means the giving of the vote to Negro men, Negro women, white men and white women.”Footnote 8 In 1920, African Americans outnumbered whites in Mississippi and South Carolina and in 219 counties in the SouthFootnote 9; if they voted as Republicans, as they were expected to do, they would challenge the hegemony of the southern Democratic party—the institution most responsible for safeguarding white supremacy through its control of state legislatures and the criminal justice system, and its influence at the federal level. Giving black women the ballot, white supremacists believed, would put all that Jim Crow had accomplished at risk. The white women of the Southern Anti-Ratification League, based in Montgomery, Alabama, saw the big picture clearly. “We oppose the adoption of this amendment because the vast majority of white women do not want it; … [and] because we believe that to adopt it will nullify the work of those wise and patriotic men who have purified the ballot box from the contamination of Negro votes.”Footnote 10

In the short run, southern white supremacists most often succeeded in keeping access to the ballot box mostly white, but it was not easy. Under pressure from aspiring southern black voters, women like the Ettrick voters and also men, they were forced to find more effective ways to exclude African Americans from the electorate, ultimately relying heavily upon the white primary and expanding its reach to efficiently disfranchise masses of black would-be voters.Footnote 11 Over time, however, African American women built on their efforts to secure ballot access in the 1920s. In the 1930s, they cultivated what historian Glenda E. Gilmore calls “the politics of community” by organizing black women as workers and consumers. In the 1940s, they turned to “the politics of protest” in the “Double V for Victory” and March on Washington campaigns.Footnote 12 Before long, all these efforts underpinned the powerful mobilizations of the freedom struggles of the 1950s and 1960s.

The Voting Rights Act, passed in 1965, finally brought the promise of the Fifteenth and Nineteenth Amendments closer to fulfillment by dramatically expanding the African American electorate in the South. The percentage of the adult black population that was registered to vote jumped in every southern state while tripling in Alabama and increasing ten-fold in Mississippi.Footnote 13 In the decades to come, however, many southern black men would find their ballot access again obstructed, this time through felony disfranchisement laws that transformed the “law and order” campaigns promoted by Richard Nixon and George Wallace, the Reagan Administration's “War on Drugs,” and the bipartisan mass incarceration policies of the 1990s into a raced, classed, and partisan matrix of voter suppression measures.Footnote 14 Those voter suppression measures had a gendered impact as well, because over the same time frame, African American women, fewer of whom were incarcerated and thus disfranchised than black men, built themselves into a decisive electoral force by voting as a bloc and turning out at consistently high rates. In every election cycle since at least 1994, African American women have exhibited the sharpest partisan preference of any demographic group.Footnote 15 In the closely fought 2000 presidential election, black women comprised nearly two-thirds of all black voters and supplied the margin of victory for Democratic nominee Al Gore in eight states.Footnote 16 And in 2008 and 2012, African American women produced the highest voter turnout of any demographic group and helped to secure the election and reelection of Barack Obama.Footnote 17 Long story short, the election of the first African American president was built in part upon the legacy left by the courageous members of the “First Colored Women Voters Club of Ettrick, Virginia” and others like them. And just as southern African American women persisted in their struggle for ballot access amidst a hostile environment a century ago, so too, through Stacy Abrams's “Fair Fight 2020” campaign and other, less well-publicized efforts, they persist today.