Introduction

In Italian East Africa, what was the relationship between private food companies and colonial government? Dictator Benito Mussolini's ten-year Battle for Grain (1925–1935) had already primed the Italian nation – culturally, economically, and militarily – to support the invasion of Ethiopia (1935).Footnote 1 This article argues that the second Italo-Ethiopian war (1935–1941) created an indelible connection between food and empire due to the Fascist regime's incorporation of East African territory by seizing fields in the countryside and building factories in the city. At the same time, pasta companies modernised manufacturing and expanded distribution in Northern Italy. In other words, Fascist imperialism in East Africa coincided with the industrialisation of pasta production in Italy, and that the advertising and packaging of major brands absorbed the racial terms and stereotypes in currency from the 1890s to 1940s. But more directly, Italian food companies like Barilla pasta also created commercial narratives of East African empire at the apex of the Fascist ventennio. The East African empire, as depicted by Italian pasta shapes and advertisements, was consumable.

From the late 1920s, corporate visions of life in colonial Eritrea and occupied Ethiopia utterly infused food shops and markets in the Italian metropole due to the ‘point of purchase’ trade model.Footnote 2 Grocers selected a single brand, like Barilla, of a given foodstuff, like pasta, to sell. Store furnishings then provided the brand with a promotional core in the city centre. Opening the door to a Barilla branded shop, a customer would have seen merchandising like calendars, account books, postcards, and catalogues. As David Ciarlo said of German imperial advertisements, they flooded food stores with a ‘tide of visuality … a pictorial ocean’ (Ciarlo Reference Ciarlo2011, 3). This article draws on Ciarlo's approach by examining ‘the dynamics of commercialized pictorial power’ (Reference Ciarlo2011, 4). Italian pasta buyers would have left a store with a paper package of boxed Barilla pasta, but they also would have received a gift with the purchase. Barilla-branded objects like makeup mirrors, switchblades, thermometers, coin holders, wallet calendars, and ash trays could fit in the palm of a woman's hand. Slipped into pocketbooks and then stuffed into desk drawers, this commercial imagery, often with East African themes, could be found in many Italian homes.Footnote 3

Historical research of Italian industry has largely focused on those areas deemed critical to national development, with emphasis on primary materials like metals (aluminum, iron, and steel), textiles (rayon, lanital), and associated industries like engineering and electronics. It may thus come as a surprise to hear that from the Unification in 1861 to the Second World War, the largest industrial segment of the Italian economy was the food sector (Carreras Reference Carreras, Amatori, Bigazzi, Giannetti and Segreto1999). Thanks to companies like Barilla, along with Buitoni-Perugina, Cirio, and Galbani, the food sector had the highest production for value added and the number of workers. Yet, as noted by business historian Silvia Messina, ‘The food business has long been considered residual, underdeveloped and made up of several family firms scattered throughout the country, often very small, conservative and led by weak innovation and growth strategies’ (Messina Reference Messina2015). Messina further notes a lacuna: the transnational activities of the Italian food industry during the 1930s. The dictatorship created economic incentives for agricultural production that greatly favoured private food companies as they strove to expand across domestic and East African markets.

The transnational history of dry pasta and its related ephemera can help to illustrate the broader enmeshment of industry and the Fascist empire. This article examines wheat farming and pasta production in tandem as a means to understand Fascist food industry in empire. Empire held two associations in Fascist Italy, one concrete and one abstract, as noted by Nicola Labanca (Reference Labanca, De Grazia and Luzzatto2002). It referred specifically to the geographic expanses in occupied East Africa. But it also evoked the lost territories of the Ancient Roman empire, together with a host of aspirational qualities, including military might and cultural status. To bring the new map of the East African empire into alignment with Fascist visions of Ancient Roman imperial prestige, industry titans approached empire as a process, held in place by sets of extractive practices. In her study of cuisine and empire, Rachel Lauden notes that these practices coalesce around two questions: how to feed the city, and how to provision the army (Laudan Reference Laudan2013). Here I aim to provide a more thorough accounting of how Italian colonialism in East Africa shaped the culture of pasta. To do so, I analyse the ephemera, the pasta advertisements and packaging, that connected occupied East Africa to Italy, demonstrating how regime projects to promote grain evolved into corporate projects in private industry. I argue that these two stories form a single cohesive narrative, one that can unite much of the excellent work that has been done on Fascist agriculture in empire (Saraiva Reference Saraiva2018, Corban Reference Corban2022) with the transnational history of Italian food companies. Because vestiges of imperial imagery can still be found in Italian pasta advertising today, we might approach food products as objects of debate regarding colonial memory and the national past, as we do with museums and monuments.

Previous scholarship on la cucina coloniale provides the broad terms for how Fascist empire in East Africa was then translated into food via naming practices that conflated the colour of food and people, with Assab licorice and Africanette sponge cake becoming popular in continental Italy (Scarpellini, Reference Scarpellini2014). But food companies also used colonial imagery of Eritrea and Ethiopia to advertise the most emblematically Italian of foods, like pasta. To investigate this paradox, an Italian food cast in colonial terms, this article follows the entanglement of pasta, as well as grains more generally, in Italian commercial narratives of empire. It contributes to the study of la cucina coloniale with new objects, photographs, and calendars attesting to Barilla's industrial ventures in East Africa, from the Archivio Storico Barilla and the Musei delle Aziende chain as well as agricultural records of the Fascist colonial government from the Istituto Agronomico per l'Oltremare. At stake in this inquiry lies the shifting question of national identity as expressed through local cuisine.

Food history, and the history of corporations, show how hard it is to separate the food supply chain into discrete stages ruled by either agriculture or industry. The two are mutually constitutive. Agrarian policy under Fascism holds a mirror up to the history of the Italian food industry, particularly for firms that processed wheat into pasta. As noted by Anthony Cardoza and Domenico Preti in their studies of Emilia Romagna, local business elites primarily benefited from the new agrarian policies, leading to what Cardoza termed a ‘fascist conquest of the countryside’ (Cardoza Reference Cardoza1983; Preti Reference Preti, Legnani, Petri and Rochat1982). Federico Cresti, Alexander Nützenadel, and Paul Corner added geographic breadth to these findings, Cresti in his incorporation of new source bases (colonial agriculture records from the Ministero degli Affari esteri in Rome and Istituto agronomico per l'Oltremare in Florence, Reference Cresti1996), Nützenadel with his centering of agrarian autarkic production (Reference Nützenadel1997), and Corner in his foundational analysis of detailing the regime strategies for increased domestic wheat production under the Battle for Grain in Emilia Romagna (Reference Corner1975). Building on this previous scholarship, the Barilla pasta company offers a case study to illustrate how the regime attempted to graft private industry onto agrarian policy in Italian East Africa.

Here I rely on the food history work of Carol Helstosky, and her investigation of consumption patterns through descriptive details and statistical analysis. This work also stands on the shoulders of consumer economics historians like Emanuela Scarpellini. Her approach relies on close observation. She examines food labels, prices, and quantities for the details that these convey about the Italian diet. In tracing the Barilla supply chain from consumption to production, I draw on Perry Willson's methodology for the history of field and factory work under Fascism (Reference Willson1993, Reference Willson2002). Case studies like Willson's Clockwork Factory are common to business history, and constitute some of the exceptional work in this arena, such as Luciano Segreto's work on Feltrinelli (Reference Segreto2019), and Franco Amatori's work on Lancia (Reference Amatori1992). Segreto takes this approach with Barilla as well, adding depth to this article, along with work from Carlo Gonizzi, head archivist of the Barilla Gastronomic Library in Parma.

From the Battle of Adwa to the Battle for Grain

Prior to the Great War, Italy struggled to obtain sufficient grain stocks. Although most of the Italian diet was based on grain, Italy had never been self-sufficient in this field. Against this backdrop, the Italian Ministry of Colonies launched the valorisation of Eritrea in 1917. The campaign aimed to transform East Africa into an Italian breadbasket, as voiced by the slogan, ‘Ask the Motherland for as little as possible and give her as much as possible’ (Italian Ministry of Colonies, ‘Approvvigionamenti, consumi e contributi delle Colonie Italiane’ 1917).1 Writing in retrospect, Minister of Corporations Ferruccio Lantini summed up the Italian grain import statistics through the 1910s and 1920s:

In materia di cereali … il nostro fabbisogno di grano non poteva essere soddisfatto, se non ricorrendo ad acquisti in paesi stranieri per quantitativi imponenti. Oltre 20 milioni di quintali di frumento sono stati importati annualmente fino al 1928 con uno esborso di valuta che ha superato anche i due miliardi di lire all'anno.

In the matter of cereals … our need for wheat could not be satisfied, if not by resorting to purchases in foreign countries of huge quantities. Over 20 million quintals of wheat were imported annually until 1928 with an outlay of currency that even exceeded two billion lire a year (Lantini Reference Lantini1939).Footnote 4

And yet, the Italian pasta industry was very successful during these years. On the eve of the First World War, battle lines severed Italy's supply chains to the east. In 1913, Italian steamships ferried 71,000 tons of pasta across the Atlantic, mainly to the United States, which absorbed 45,000 tons of the total (Messina Reference Messina2015). But it was a high-water mark for the Italian pasta industry, as the wartime trade interruptions created space for competition from Italian emigrants, who founded their own pasta factories in Canada, the United States, Brazil and Argentina (Rodanò Reference Rodanò1935).Footnote 5 With less flour arriving from Romania, Turkey, and Russia, bread shortages convulsed Italy in December 1914, and prices rose rapidly. Bakeries pulled dark loaves of ‘war bread’, made from chestnut and other minor flours, from their ovens. Still, costs rose, causing hunger that in turn led to violent public unrest. The bread strikes claimed 50 lives.Footnote 6 Rural instability pervaded the Italian colony of Eritrea as well. On 8 February 1917, Governor of Eritrea Giacomo De Martino summoned all regional commissioners to Asmara to deliver a message. Every field in Eritrea was to be sown with Italian staples, namely wheat, potatoes, and corn. The decree attempted to halt cultivation of barley and ‘cereals of indigenous consumption’, like teff (Istituto Coloniale Italiano 1920, 291). But Eritrean farmers were highly sceptical of the efficacy of Italian agronomy Protests spread from Kwä‘atit to Akkälä Guzay (Zaccaria Reference Zaccaria, Bekele, Chelati Dirar, Volterra and Zaccaria2018).

When Mussolini rose to power in 1922, the regime focused on grain as the symbolic commodity at the centre of their new autarkic politics. By unshackling the Italian economy from the ‘slavery of foreign wheat’, the Fascists would achieve financial and diplomatic autonomy on the world's stage. But to decrease its dependence on trade partners, it would first need to increase domestic wheat production and consumption. To this end, Mussolini inaugurated the Battaglia del Grano (Battle for Grain) in 1925. Wheatfields were battlefields, and the horns of victory would metaphorically blast when Italian farmers pushed their field to the productive limit, squeezing 15 quintals of wheat from each hectare of land (22 bushels per acre). It was an astronomical ask. As Tiago Saraiva has observed, the mythic 15 quintal figure would have meant increasing the productivity of Italian wheatfields ‘by one third in comparison to the post-World War I values and well above the productivity of the US for the years 1923–1927 (14½ bushels per acre)’ (Saraiva Reference Saraiva2018). In addition to increasing wheat production, the regime also aimed to achieve financial autonomy through protectionist measures. Just a year after the Battle for Grain, the Battaglia della Lira (Battle for the Lira) was launched on 18 August 1926, introducing protectionist tariffs for national industries. In a much photographed public appearance, Mussolini stripped bare to the waist in LUCE newsreels to thresh the Ardito grain planted outside Fascist New Towns like Sabaudia.

Many economic historians consider the Battle for Grain to be a success, in that it increased wheat production in certain regions of Italy. Paul Corner (Reference Corner1975) Luciano Segre (Reference Segre1982), Alexander Nützenadel (Reference Nützenadel1997, Reference Nützenadel2001), and the Banca d'Italia (2011) leveraged ISTAT data to show that improvements to wheat cultivars, machines, and fertilizers boosted domestic wheat production, ultimately achieving Mussolini's keystone goal of making Italy self-sufficient in wheat production. At the same time, many food historians define it as a failure, due to its negligible benefits to small farmers and the overall cost. Carol Helstosky and Emanuela Scarpellini combine ISTAT and international data banks in their studies, and are more tepid in their assessments. Helstosky points to the Royal Institute for International Affairs in London, which ‘estimated that the Battle for Grain cost Italy 225,570,000 lire between the years 1925 and 1929, given the international wheat surplus and a turn of exchange in Italy's favour’, leading her to deem the Battle for Grain ‘a costly mistake’ (Helstosky Reference Helstosky2004a, 43). Scarpellini, who relies more heavily on ISTAT than Helstosky, characterises the Battle for Grain as a marginal success for some northern and central reclamation regions: ‘Technically, there was increased production, above all after the land reclamations in Latium and the Maremma, but the real crux of this campaign was gaining the consent of the farmers, after a long period of disinterest shown by the liberals, precisely when the country's productive axis was definitively shifting towards industry’ (Scarpellini and Mazhar Reference Scarpellini and Mazhar2016, 86). Both lines of thinking are technically correct, as they have defined success for the Battle for Grain by different parameters.

It is Scarpellini's point that perhaps matters most for the present discussion, because it speaks to the connection between Emilian wheat farmers and Parma's pasta entrepreneurs. Here, there is broad agreement regarding who reaped the rewards. As Perry Willson put it, ‘historians generally concur that big landowners benefited more than small from many of the regime's policies. In a number of ways, furthermore, government policy assisted industry far more than agriculture’ (Willson Reference Willson2002, 15).Footnote 7 Most recently, Mario Carillo's economic analysis adds a surprising twist to Scarpellini's observation. Bringing the statistical analysis of the Battle for Grain up to the present day, he argues that the policies industrialised towns more than they ruralised regions. In townships like Parma, where the Battle for Grain increased local wheat yields, bursts of economic activity followed, ‘unexpectedly trigger[ing] a cumulative process of development that unfolded over the course of the twentieth century’ (Carillo Reference Carillo2020, 43).

The Battle for Grain and the Battle for the Lira were good for the dry pasta industry across the Italian peninsula. But the Battles were especially helpful to northern upstarts like Parma-based Barilla. Barilla's engagement with the politics of Fascism is not characteristic of pasta companies in Italy. Barilla, located in Benito Mussolini's home region of Emilia Romagna, made political choices that pasta companies like Agnesi in Liguria and De Cecco in Abruzzo did not. These brands barely engaged with Fascist politics, and their advertisements and products did not incorporate the regime's projects and symbols.Footnote 8 But while Barilla's ties to the regime may seem to make it an outlier among interwar pasta companies, its enmeshment is characteristic of food companies that were located near symbolic sites of Fascist ascension, like Perugina chocolates and Buitoni pasta in Umbria, where the future colonial administrators gathered at the Hotel Brufani in Perugia to herald the March on Rome.

For the dry pasta industry, early Fascist alimentary policy provided public sector contracts to large firms, which in turn allowed them to purchase new machinery and to break ground on new factory plants. Buitoni expanded domestically and abroad, opening their first foreign pasta plant in France. Barilla took advantage of the protected domestic market. It aimed to increase its market shares in a sector that had been dominated by southern Neapolitan entrepreneurs since the eighteenth century. The revaluation of the lire set the lire-pound exchange rate at 92.46, thereafter known as the quota 90. Though the quota 90 aimed to fight inflation, its ratification curtailed exports, and contributed to the collapse of the Italian stock market. As Luciano Segre has observed, the quota 90 was a contradictory policy, in that it increased the exchange rate and depressed wheat prices, effectively neutralising the wheat tariffs and ultimately working against the Battle for Grain (Segre Reference Segre1982).Footnote 9

In addition to new cultivars and chemicals, the Battle for Grain also introduced new trade fairs and exhibitions where Barilla could promote their pasta brand. Gold medals and diplomas of honour ornamented the walls of Riccardo Barilla's company offices, as Barilla took the top prize at the inaugural First Wheat Exhibition in Rome in 1927. Barilla returned the regime's compliment. The 1929 Barilla catalogue offered a number of new pasta shapes, all signs of the times. Gears and wheels evoked industry, airplanes and ‘rapidi’ evoked technology and speed. The capital of Libya, Italy's North African colony, was rendered as butterflies called tripolini. Housewives could even boil a pot of fasci, the bundle of lictors that symbolised the Fascist party.Footnote 10

In the early 1930s, Barilla not only changed the company pasta shapes, they also changed the pasta recipe to support Fascism's promotion of prolific motherhood, defined by the regime as birthing six or more children. The company introduced what Luciano Segreto refers to as a ‘therapeutic’ pasta line, featuring gluten-enriched pastas for infants and small children (Segreto Reference Segreto1988, 4). In addition to introducing new products that signaled company support for the regime's pronatalist policies, Barilla sponsored the Board for the Protection of Motherhood and Childhood (known by the Italian acronym ONMI) directly. Riccardo Barilla donated pasta to regime nurseries in 1932, and funded ONMI construction projects, investing over 10,000 lire (Segreto Reference Segreto1988, 4). He made numerous, well-publicised visits to Roman nurseries that received the food aid, meeting with medical staff and cafeteria cooks on site.

The Barilla company did better still at the Second Wheat Exhibition, held in Rome five years later, on 2 October 1932, the tenth anniversary of the March on Rome. It was a high-profile event. Royalty, including King Vittorio Emanuele and Prince Umberto, sat in attendance for speeches from Mussolini and Minister of Agriculture Giacomo Acerbo. Here, Barilla received the gold a second time. What's more, their exhibit also drew the personal attention of the Duce. Breathless coverage in Il popolo d'Italia described the conversation between Riccardo Barilla and Benito Mussolini, ‘His Excellency the head of government showed a keen interest … stopping with special interest at the stand of the Barilla pasta factory of Parma.’ He especially enjoyed Barilla's ‘symbolic homage of fragrant bread’. Conspicuous wins like these led to further meetings between Barilla's management and key figures of the Fascist regime in Rome during the mid-1930s. Multiple accounts attest to Riccardo Barilla's ongoing curation of positive relationships with Achille Starace and Benito Mussolini, as well as lesser-known officials with ties to the colonial armies (Segreto Reference Segreto1988, 4–5). On 2 October 1934, Riccardo Barilla welcomed Guido Marasini, former president of the Provincial Federation of Farmers to a factory visit followed by a private reception in the company garden.Footnote 11 In Marasini's then new capacity as the executor of trade union regulations, it was a valuable friendship for an industrialist to have. In the early 1930s, Barilla relied on government contracts for the majority of its business, both in Italy and abroad. In every Italian colony, Barilla pasta was now available for purchase (Segreto Reference Segreto1988, 4).

Military supplies accounted for the majority of Barilla's business with the state in the 1920s and early 1930s. Pietro Barilla described how pasta companies gained these contracts, ‘auctions were held, companies competed and whoever won the auction got the production contract: at the time there was a lot of military work and very little civilian work’ (Barilla, cited in Gonizzi Reference Gonizzi2003, 234). In Emilia Romagna, the economic depression of the early 1930s brought unemployment to historic highs, reaching 20 per cent of the working-age population in Parma. Still, the military contracts meant that Barilla fared better than other local food industries like dairy and canning. After studying at the Calw international college in the Black Forest region of Germany in 1932–3, Pietro Barilla returned to Italy with a new zest for ‘order and organisation’ (Gonizzi Reference Gonizzi2003, 234) that he applied to corporate strategy.

Minister of Corporations Ferruccio Lantini reflected on these years in his 1939 Autarchia Alimentare article, ‘I Problemi della Autarchia Alimentare’, using the economic situation as the premise for his proposals for wheat farming in the empire.Footnote 12 Autarkic policy hurt Italian companies as much as it helped them, as Italy's isolation from foreign trade hindered Italian exportation abroad even as it aimed to promote domestic industry through protectionist tariffs, as observed by Carol Helstosky in her specific investigation of alimentary autarchy and Emanuela Scarpellini in her broader economic history of Italian consumption under Fascism.Footnote 13 Although Riccardo Barilla successfully cultivated relationships with the heads of the Fascist state to promote company interests, his ties to the Fascist officials of the PNF branch in Parma burned with acrimony. The Corriere Emiliano smeared Riccardo Barilla for his labour practices, specifically for employing too many women and children, and not enough men from the local Fascist milizia. Footnote 14 Newspaper columns lambasted the whole Barilla family for their sub-par contributions to the nascent Italian empire in East Africa. When Riccardo Barilla's daughter and son-in-law donated their wedding rings to the nation for the Day of Faith, local officials refused to accept the donation. The Barilla wedding rings were ‘stamped with the mark of low-quality gold’, making them an unworthy contribution to the nation (cited in Segreto Reference Segreto1988, 5).

By 1936, Barilla was convinced that the future of the company lay in moving away from overseas work orders, including those for the Italian army, and towards the emerging middle-class market. A second trip to Germany in December 1936 brought Pietro Barilla into the orbit of leading German industrialists. He wrote of his meetings, ‘Very interesting visit to the Schram factories. I had the pleasure of spending half a day with an industrialist who has a lot to say with regard to pasta. Lufthansa behaved very well, and in this field too, which is new to me, I had the opportunity to get to know a proper organisation’.Footnote 15

In the agricultural sector as in the pasta industry, profits of the Battle for Grain went to northern landowners. Po Valley landowners arguably gained the most from wheat autarchy. As owners of the fertile plains and paddies, they reaped huge profits from braccianti, the seasonal hired hands who owned no land of their own. Willson draws the regional differences as one of farming approach: ‘Whilst Northern farms increased output through productivity gains, many Southern farms did so largely by expanding acreage’ (Willson Reference Willson2002, 14) Even though the Battle offered generous state subsidies to the latifondisti, the southern landowners, in the form of high duties on imported grains, Helstosky, drawing on statistician Benedetto Barberi's analysis of food availability in Italy, notes ‘the south and the islands lagged behind with only a 20–30 per cent increase in yield … the campaign could not provide more wheat at cheaper prices for Italian consumers … the average amount of wheat available, per person, decreased between the decade 1921–30 (178.5 kilograms per person) and 1931–40 (164.4 kilograms per person)’ (Helstosky, 2004aa, 76). Hunger in the Mezzogiorno posed a problem.

Demographic colonisation in East Africa promised a partial answer to this particular southern question by restoring Italian peasant bodies through wheat farming. The Italian Fascist regime promoted massive resettlement schemes of ethnic Italians to the colonies, where they farmed the new rust-resistant wheat varieties developed by the Department of Genetics and Plant Breeding of the Centro Sperimentale Agricolo e Zootecnico per l'Africa Orientale Italiana (CSAZAOI). Settlements in Ethiopia aimed to root homogenous regional groups in new lands, with names like Puglia d'Etiopia, Romagna d'Etiopia, and Veneto d'Etiopia.Footnote 16 Italy, a latecomer empire, thus stands in contrast to older models of British and French colonialism, as Roberta Pergher has argued (Pergher Reference Pergher2018). In these older empires, small numbers of white settlers oversaw vast work crews of local labour. More akin to imperial Germany, Italy was a lesser European colonial power, albeit one with access to luxurious African food products, like Ethiopian coffee and Somali bananas.

Under Italian colonialism, the Fascist regime's emphasis on demographic colonisation and settlement centered on the question of land use. Who could farm where? What crops could they plant? Which methods and tools could they use? ‘Indeed’, Haile Larebo contends, ‘one of the most notable legacies of Italian agricultural policy was the introduction of racial competition and conflict over land and production’ (Larebo Reference Larebo1994, 91). Rhiannon Welch has elaborated on this point, noting that the regime made rhetorical links between agricultural and biological labour through a shared rhetoric of productivity, what she terms the regime's ‘vital key’ (Welch Reference Welch2016). Fascist empire was thus a social as well as territorial reclamation project aimed at energising Italian labourers as much as increasing the agricultural productivity of East African land.

Two bodies of historiography of Italian East Africa offer support for this characterisation. The Battle for Grain provides a means to interweave these threads, with foundational Ethiopian land-use scholarship emphasising the battle, and the more recent ecocritical turn emphasising the grain. Haile Larebo's account of land grant disputes between Ethiopian and Italian elites (Larebo Reference Larebo1994), dovetails with Jim McCann's emphasis on Emperor Menelik's agricultural policies and taxation as nationalisation projects (McCann Reference McCann1995). These historians use government materials to examine the machinations of elite political actors at the national level. They are in conversation with the scholarship of George Baer (Reference Baer1967), Franco Catalano (Reference Catalano1969) and Giorgio Rochat (Reference Rochat1971), with studies oriented around the core belief that the Ethiopian Invasion of 1935 aimed to use a swelling empire abroad to distract the Italian public from the deteriorating economy at home.

From the start, the Fascist regime conflated its military and agricultural projects in East Africa. As Francesco Angelini, the National Secretary of the Sindacato Fascista Tecnici Agricoli and Deputy of the XXVII, XXIX, and XXX Legislatures in the Kingdom of Italy put it, the perfect farmers for the new colonial settlements were the legionnaires who had conquered Libya, Italy's so-called ‘fourth shore’. He proposed the Legione Rurale ‘Dux’, an agricultural colony of a ‘technical-military nature’, composed of one thousand men between the ages of 25 and 40 and their families (assumed to consist of a wife and five children) to act as ‘military-colonial pioneers’.Footnote 17 The legionnaires, he went on, were ideal colonists: ‘Sono prescelti, con carattere di assoluta preferenza, i rurali in servizio militare ed in attesa di smobilitazione’ (‘Those who are selected, with a character of absolute preference, are the rural people in military service and awaiting demobilization’). The Italian colonial government would provide each family with 15 to 20 hectares of land that ‘had previously belonged to Emperor Haile Selassie, the Rases, and other feudal lords of the Old Empire’, (prima appartenenti all'ex negus e familiari, ai rai e ad altri feudari dell Vecchio Impero’). The settlement would be overseen by a strict agro-military hierarchy, including a commander, a vice-commander, and a lieutenant commander, aided in turn by commanders for every hundred people, and their own sub-commanders below that.Footnote 18 This was the regime's imperial vision: a colony of ‘militia-contadini’ who would cultivate and valorise the Ethiopian fields.

The Fascist milizia volontaria invaded Ethiopia in October 1935, and Mussolini declared the establishment of Italian East Africa. Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie spoke out against the aggression, and the League of Nations enacted sanctions against Italy (League of Nations 1936). With foreign grain imports cut off, valorisation of the colonies assumed increased importance. The regime demanded that the colonies become self-sufficient, in the hope that they would soon help to feed Italy. The Fasci di Combattimento built experimental agricultural stations in the attempt to breed better wheat cultivars (Saraiva Reference Saraiva2018), a eugenic step that they believed would ultimately build better people. But despite promises that the Italian farming technology would coax the Ethiopian highlands to produce enough grain to feed Abyssinia and Italy alike, the colonies always imported more food from Italy than they ever exported back to the metropole. In 1936 Italy exported over 75,000 tons of wheat to Ethiopia. The following year, the figure nearly doubled, with 128,000 tons of wheat making the Mediterranean crossing. The high export figure did not indicate unbridled success for the Battle for Grain in continental Italy. As Perry Willson (Reference Willson2002) has noted: ‘Many historians have judged the Battle for Wheat harshly, noting, for example, that high duties meant that Italians ate expensive wheat far above world prices and that the obsession with wheat damaged other produce.’Footnote 19 Rather, it evokes the failure of the regime's attempt to use Ethiopian fields to provide Italy with more bread and pasta. As demonstrated by statistics furnished by the Minister of Corporations Antonio Ferruccio, the colonial settlements could barely feed themselves.Footnote 20 As Saraiva put it: ‘Instead of becoming the granary of Italy, Ethiopia swallowed most of Italy's food exports. In 1938, without a clear idea of the actual supply needs of the recently conquered colony, Mussolini simply ordered that the empire become self-sufficient in wheat’ (Saraiva Reference Saraiva2018, 147).

The Barilla Company in Libya and Eritrea

Pasta companies not only participated in creating the mythos of East African empire. They also provided food donations and financial support. In 1932, Barilla won first prize for their pastas at the Tripoli Trade Fair in Libya, expanding their brand presence into the north African colony. As early as 1933, the Italian expansionist journal Illlustrazione coloniale listed Barilla, Buitoni, and Fratelli Bertagni as the key overseas pasta suppliers for ‘Amministrazioni centrali, Governi coloniali, Comandi di truppe, Militari, Porti, Ferrovie, Arsenali, Imprese di lavori pubblici, di colonizzazione, costruzioni, trasporti’ (‘central administrations, colonial governments, troop commands, military engineers, ports, railways, arsenals, public works, colonisation, construction, transport companies’).Footnote 21 Photographs from 25 April 1935 show Italian and East African labourers unloading endless crates of Barilla pasta (Figure 1), as Marshal Emilio Del Bono amassed Italian and Askari troops and supplies to march southward. As previously noted, the Italian-led forces attacked Ethiopia on 3 October 1935, without prior declaration of war. With the occupation of Ethiopia, the Fascist government offered substantial military orders to key pasta firms, including Barilla. Military pasta supply orders continued through the Secobd World War (Messina Reference Messina2015). Photos depicting the arrival of Barilla pasta on African shores taken on 11 November 1935, in the immediate aftermath of the invasion, now show military ranks in attendance at the Barilla delivery. A line of Askari and Italian soldiers, the former in fezzes, the latter in garrison caps and pith helmets, stand guard over the pasta boxes (Figure 2). Barilla's contributions to empire were recognised in the January 1937 volume of L'Industria nazionale, which lauded Barilla in their ‘rubrica di benemeriti’, a list of industrial, economic and social groups honoured for their substantial contributions to the progress and wellbeing of the Italian nation. Barilla was further included in a smaller group, reserved for industries that ‘hanno fatto pervenire al Duce forti somme in denaro, volta a volta destinate alle Federazioni Provinciali dei Fasci di Combattimento o ad enti nazionali’ (‘sent large sums of money to the Leader, destined for the Provincial Federations of the Combat Fascists or national boards’).Footnote 22

Figure 1. Photograph of Italian and East African laborers unloading Barilla pasta crates. 25 April 1935. BAR I A 0000 00215. Barilla Historical Archive, Parma.

Figure 2. Photograph of Italian and Askari soldiers with Barilla pasta crates. 25 November 1935. BAR I A 0000 00232. Barilla Historical Archive, Parma.

Figure 3. ‘Pietro Barilla alla Galbani dell'Asmara’. 1938. BAR I A 0000 00535. Barilla Historical Archive, Parma.

Members of the Barilla family participated personally in East African business ventures. ‘I assure you that we have not thought twice about sacrificing ourselves, just to introduce our name into Africa’, Pietro Barilla wrote to his friend Angelo on 21 May 1936.Footnote 23 Letters and photographs from the Archivio Storico Barilla attest to this. Pietro Barilla served in the Italian Fascist army's 97th Motor Corps, and sent over 800 war front letters from industrial and military sites in Asmara, Llubjana and Ukraine before and during his deployment, from 1939 to 1946. Addressed to his secretary, ‘Miss Rivola and the Ladies of the Office at the Barilla Pasta Factory’, the letters detail the assignments abroad (‘we accompany the foot soldiers, take them everywhere, they are the reason for our movement and life’) and the shifting geography of war. On 9 January 1939, Barilla thanks Rivola for a letter sent to him in Ethiopia, where he was undertaking commercial tasks in the Italian territory. The following year, in 1940, Pietro Barilla redrafted the Barilla pasta company's exclusive contract with the Galbani cheese company for sales in Eritrea.Footnote 24 A photo taken in Asmara in 1938 shows Pietro Barilla with the Galbani family in their offices (Figure 3). He managed the coup thanks to an investment in the maintenance and use of rail distribution networks across Ethiopia, for parallel use with Galbani cheese distribution. The dairy company from Melzo, Lombardy, had first laid the tracks. It was, as Archivio Storico Barilla archivist Carlo Gonizzi notes, part of a strategy for expansion that ‘envisaged a distribution of pasta in eastern Africa’ (Gonizzi Reference Gonizzi2003, 209).Footnote 25 In other words, Pietro approached military deployment as a business opportunity, one that opened new territories to the Barilla family's commercial empire.

Figure 4. Photograph of East African children dressed in clothing designed from Barilla flour sacks. 25 November 1935. BAR I A 0000 00233. Barilla Historical Archive, Parma.

At the nexus of private food industry and Fascist empire, railroads and highways connected East African consumers with Italian foods, and also made them accessible to Fascist government and military violence. Concurrent with the militarised deliveries of November 1935, there is also a set of posed photographs featuring East African children. The Archivio Barilla provides the following description of Barilla's activities in East Africa vis à vis the photos,

Tra le prime aziende nazionali coinvolte nell'espansione coloniale, la Barilla aveva stipulato un accordo con la Galbani di Melzo per usufruire parallelamente della rete commerciale e dei depositi impiantati dall'azienda casearia in Africa Orientale. Vari documenti testimoniano questa presenza, ma la foto più suggestiva ritrae tre ragazzi di colore che indossano abiti ricavati dai sacchetti di tela bianca della pasta Barilla.Footnote 26

One of the first national companies involved in colonial expansion, Barilla had entered into an agreement with Galbani di Melzo to simultaneously use the commercial network and the warehouses set up by the dairy company in East Africa. Various documents testify to this presence, but the most evocative photo portrays three boys of colour wearing clothes made from Barilla pasta's white sacks.

The first photograph shows a group of Ethiopian children holding packets of dry spaghetti, with three in front wearing tunics sewn from Barilla pasta sacks (Figure 4).Footnote 27 In the vein of LUCE propaganda featuring East African subjects, the scene is carefully posed. Someone gave these children dry pasta to hold. They would be highly unlikely to prepare it. Even an adventurous eater would be taken aback by dry pasta's sharp edges and lack of flavour. Dry pasta would have to be cooked by an adult familiar with its preparation in boiling water. Posing children with Barilla pasta frames them as the recipients of charity, via the distribution of Italian pasta in East Africa. Even the packaging plays a role, clothing the children in the Barilla brand. Though this commercial garb presents a striking image today, textile historians like Linzee McCray have observed that sackcloth dresses were ubiquitous in many countries during the Great Depression, particularly in the United States. American flour companies noticed that mothers searched high and low for the most colourful flour sacks to buy. After baking their bread, they sewed the free fabric into dresses.Footnote 28 With near-exclusive contracts in place, Barilla had no such competition in Eritrea and produced simple, branded sacks like the ones shown here.

In the second photo, two boys flank a young man (Figure 5). Each holds at least one sack of Barilla Pastine. The loose dried pasta, often served in broth as a food for weak stomachs, is promoted on one bag as ‘refined’, and on the three others as ‘hygienic’. Although the photograph's location is unknown, ‘Mogadiscio’, the Italian spelling of the Somali capital of Mogadishu, is stamped onto several crates, attesting to importation routes that spanned the whole of East African empire. It is against this backdrop of Barilla's financial support of the Fascist imperial initiatives in East Africa that this next section turns to examine the company's use of East African imagery in pasta advertising.

Figure 5. Photograph of East African children and teenager holding Barilla pasta sacks. BAR I A 0000 00239, OR.342. Barilla Historical Archive, Parma.

The Italian food industry mass-marketed the East African empire through an organised system of symbols. Bananas, palm trees, and the inevitable tukul huts were stamped onto chocolate boxes and cookie tins. Corporations carried Fascist narratives of empire into the domestic sphere, making them a common presence in Italian kitchens and pantries. Barilla engaged in what Anne McClintock has termed ‘commodity racism’, a phenomenon that, ‘converted the narrative of imperial progress into mass-produced consumer spectacle’ (McClintock Reference McClintock1995, 33).

The 1935 Barilla photograph recalls Aurelio Bertiglia's then-popular colonial postcards (Figure 6).Footnote 29 His 1936 propagandistic artwork cast Italian Fascist soldiers and East African subjects at war as adorable children at play, promoting Fascist imperialism in East Africa as a humanitarian project. Bertiglia's colonial kewpie dolls depict the charitable distribution of Italian cuisine, figured as a European civilising gesture among African tukul huts in jungle villages.Footnote 30 Focusing on the broadly popular symbolism of children and food, postcard propaganda suggested that the Italian presence in East Africa consisted more of charitable food provision than military action. The postcard also reverses the history of who fed whom. In the colonies, Italian soldiers often hired Eritrean women and girls as cooks. Portraying soldiers as children obscures their potential to commit adult acts of brutality. Bertaglia's saccharine depiction of colonial conviviality obscures the sexual violence that often occurred in soldier-cook relationships in the colonies.Footnote 31 Postcards travelled. They helped Italian colonial imaginary of East Africa to circulate, both within Italy and beyond its borders.

Figure 6. Postcard of Italian children and East African toddlers, Rome, 1936. Illustration by Aurelio Bertiglia. Stanford University Library, Department of Special Collections and University Archive, MSS 2016-071, Palo Alto, USA.

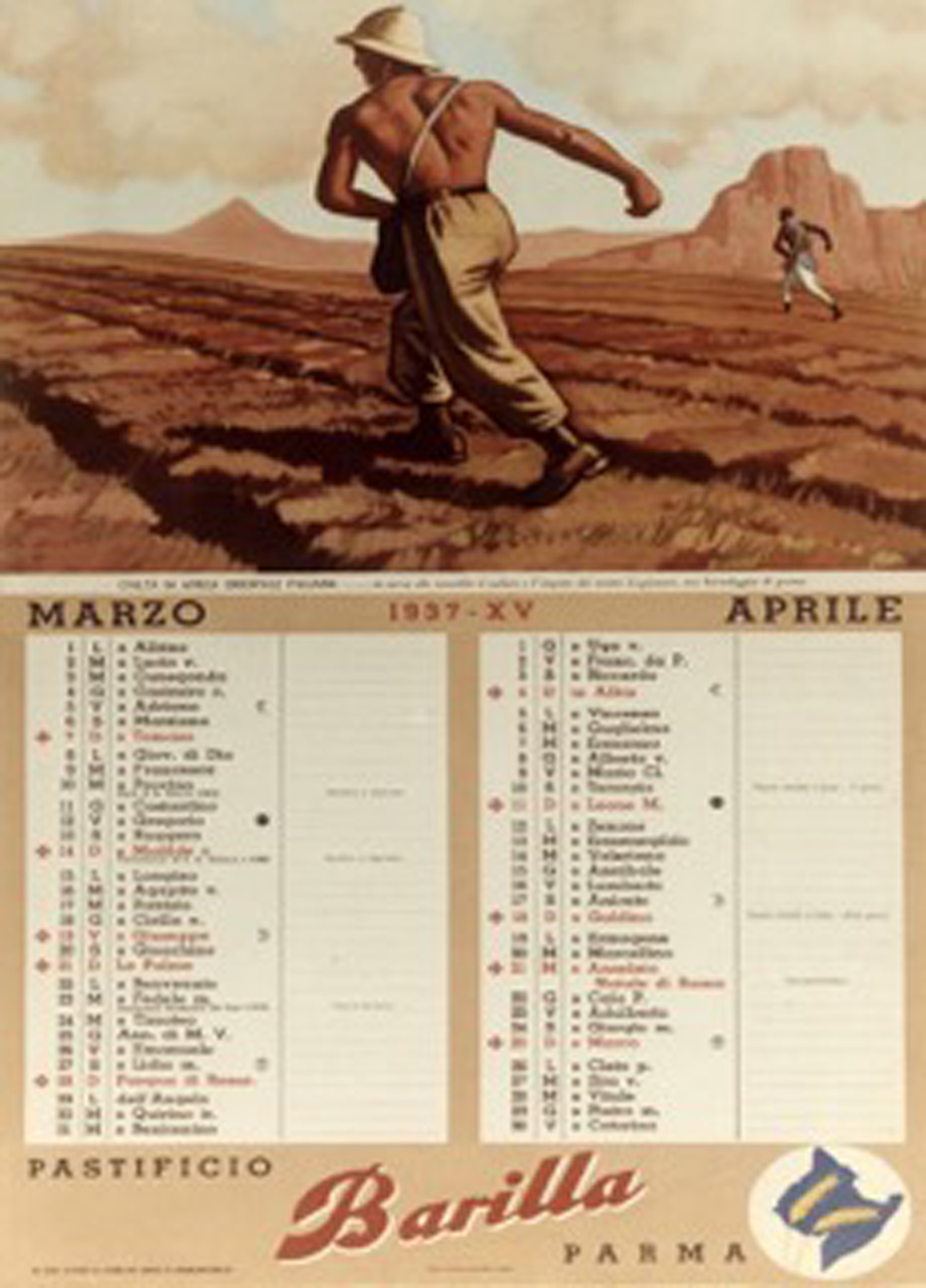

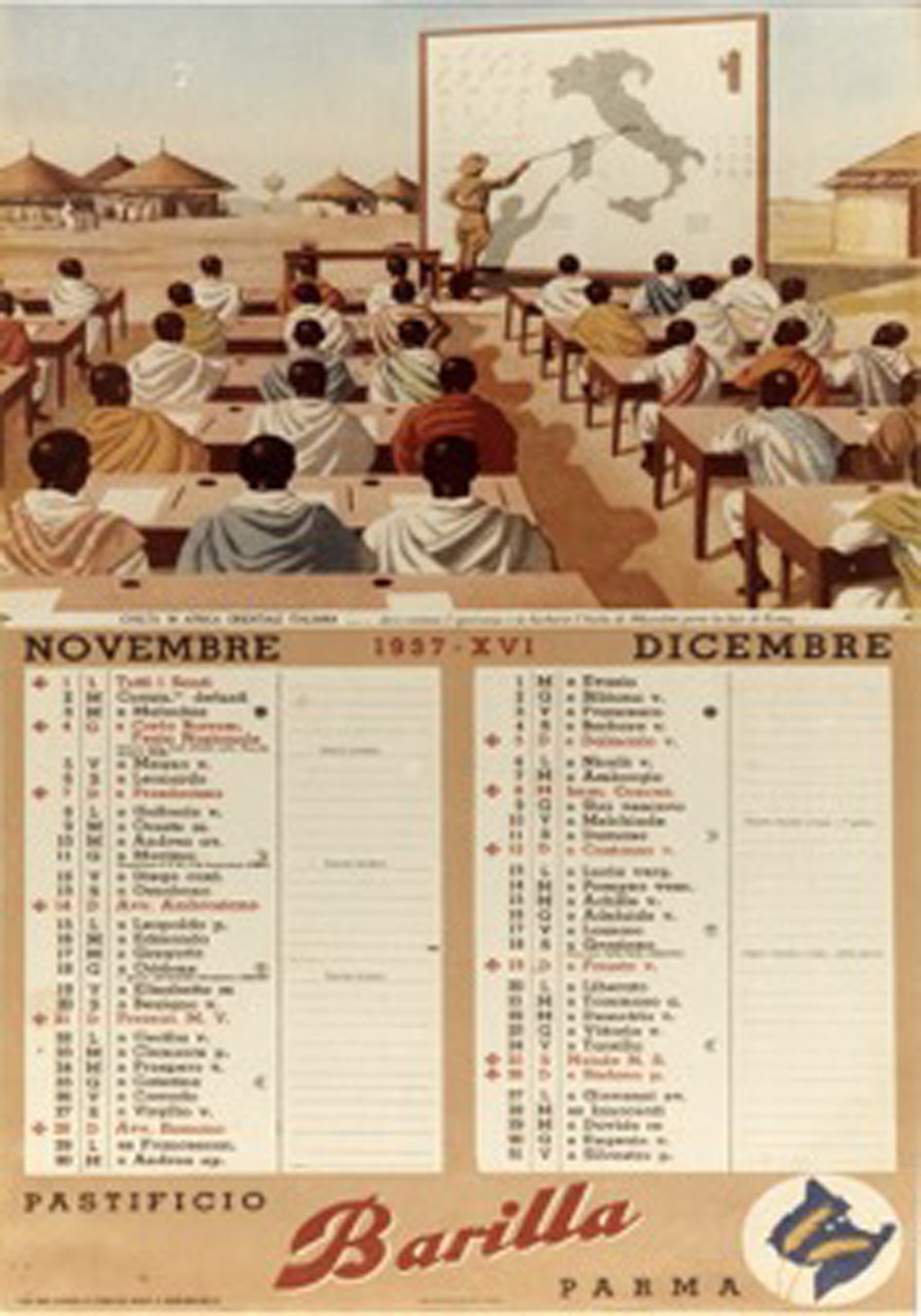

Consider Barilla's 1937 promotional calendar, ‘Civiltà in Africa Orientale Italiana’, (‘Civilisation in Italian East Africa’). Gifts like these were often given to wholesalers and their customers during the December holidays, as a means of building brand loyalty. A Christmas Eve advertisement in the Gazzetta di Parma publicised the give-away as part of a broader promotion for the decorative holiday baskets of pasta sold at Barilla-branded shops: ‘Un augurio, un cestino, un calendario’ (‘A greeting, a basket, a calendar’).Footnote 32 Calendars offered a particularly long-lasting format for pasta advertising that brought commerce and East African empire into Italian kitchens. For twelve months, Barilla calendars remained tacked to the walls of shops and homes, meaning that company advertising, and empire, entered Italian daily life as home décor.

The calendar presented the year to come as a succession of scenes of imperial conquest. It also circulated one of the regime's dearly held agricultural myths – that Italians would transform the Ethiopian landscape, ‘civilising’ it through wheat farming in the manner of Ancient Romans in the fields of Axum.Footnote 33 At once, the calendar promoted Barilla pasta specifically, and the East African invasion more generally. Artistic input from the Institute of Foreign Trade (Istituto per il Commercio Estero) ensured that the colonial imagery was suitable for distribution in Italy and abroad.Footnote 34 Pasta and industry are almost entirely absent, but for the footer bearing the Pastificio Barilla Parma company logo, appended by a new, imperial trademark: two shafts of wheat superimposed on a map of the East African empire, inked in Barilla blue.

In January-February, an Italian aircraft zooms across the desert sky, saluted by nomads on camelback below. In March-April, Barilla directly addresses their stake in the East African project, with an image of an Italian and an East African farmer sowing grain (Figure 7). The caption reads: ‘La terra che conobbe il valore e l'impeto dei nostri Legionari, ora biondeggia di grano’ (‘The earth that knew the value and the impetus of our Legionnaires now becomes blonde with grain’). In May-June, an Askari soldier kneels under the Italian flag, striking a blow with his mallet to break the chain that holds a slave captive. In December, an Italian provides an Italian geography lesson in an open-air classroom. With his wooden ruler, he points to Rome (Figure 8). The December caption reads: ‘Dove esisteva l'ignoranza e la barbarie l'Italia di Mussolini porta la luce di Roma’ (‘Where there was ignorance and barbarism, Mussolini's Italy brings the light of Rome’).

Figure 7. Inside page of 1937 Barilla wall calendar ‘Civiltà in Africa Orientale Italiana’, (‘Civilisation in Italian East Africa’). Printed in Rome, March 1937. BAR I Rl 1937 0000.02. Barilla Historical Archive, Parma.

Figure 8. Inside page of 1937 Barilla wall calendar, ‘Civiltà in Africa Orientale Italiana’ (‘Civilisation in Italian East Africa’). Printed in Rome, March 1937. BAR I Rl 1937 0000.06. Barilla Historical Archive, Parma.

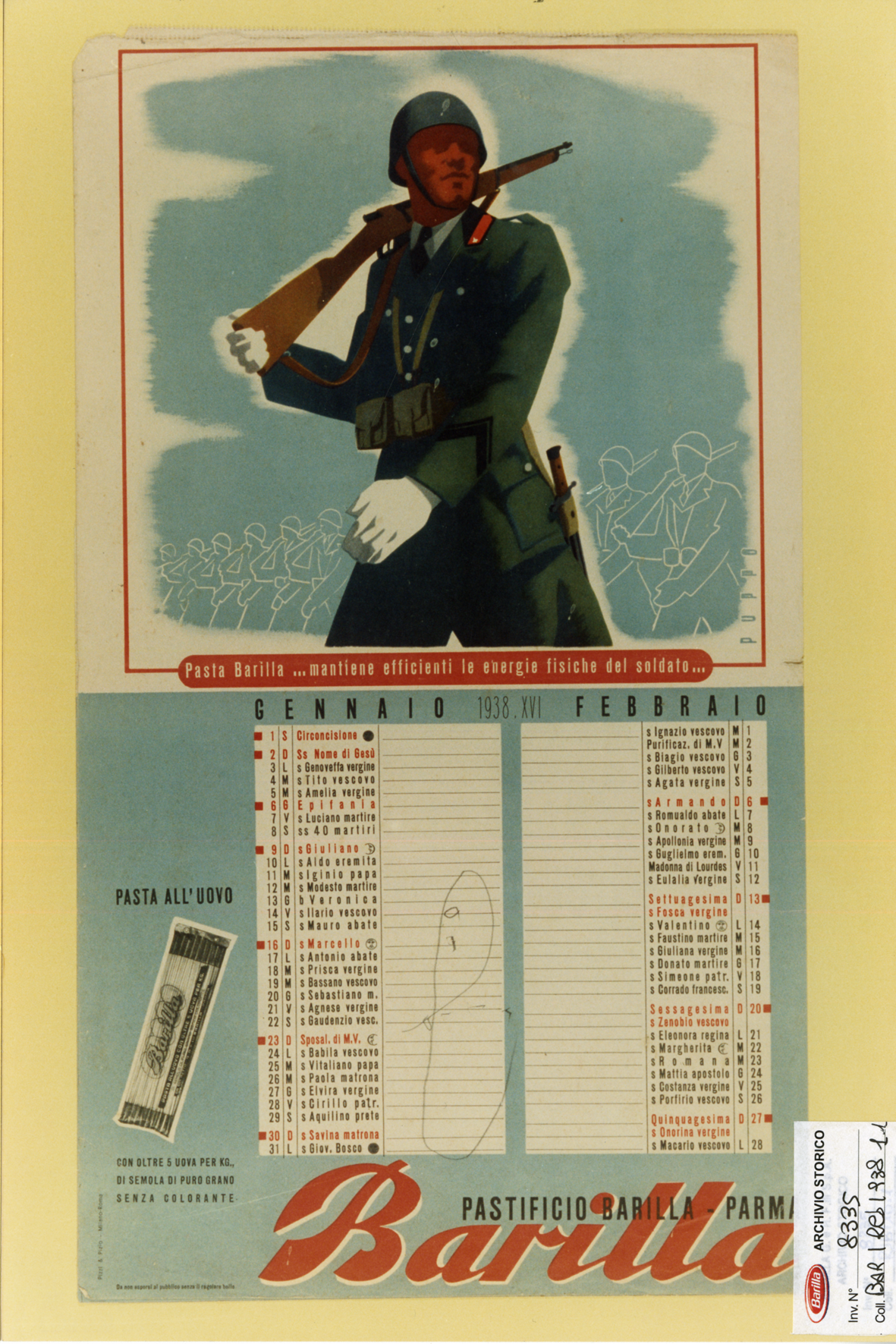

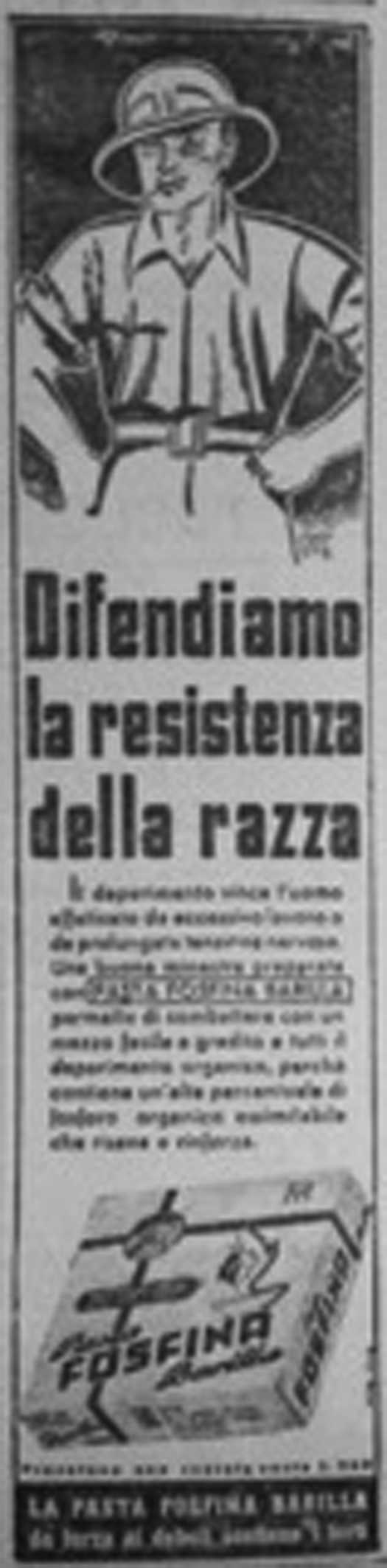

Barilla elaborated on the East African imperial theme the following year with their product launch for Fosfina pasta, a vitamin-enriched product aimed at the middle-class market. Pietro Barilla commissioned Nino Giuseppe Caimi, owner of the Milanese Ennecé advertising agency, to manage the rollout. Advertisements were drawn by the Chiavaresi graphic artist Mario Puppo, famous for his propagandistic travel posters (Figure 9). The Pasta Fosfina advertisements hewed to this touristic aesthetic, featuring colonial soldiers in their signature pith helmets. Text suggested that this pasta could combat a host of modern ailments, such as nervous tension caused by too much office work, thanks to its high phosphorous content. By eating vitamin-enhanced pasta, Italians could ‘defend the resistance of the race’ at home and in East Africa (Figure 10),

Il deperimento vince l'uomo affaticato da eccessivo lavoro o da prolungata tensione nervosa. Una buona minestra preparata con Pasta Fosfina Barilla permette di combattere con un mezzo facile e gradito a tutti il deperimento organico, perchè contiene un'alta percentuale di fosforo organico assimilabile che risana e rinforza.

Depression overcomes the man who is fatigued by excessive work or prolonged nervous tension. A good soup prepared with Barilla Phosphine Pasta allows you to fight organic decay in an easy and pleasing way, because it contains a high percentage of assimilable organic phosphorus which heals and strengthens.

Figure 9. Inside page of 1938 Barilla wall calendar, ‘Pasta Fosfina’, designed by Mario Puppo. Printed in Milan by Pizzi e Pizzio, 1937. BAR I Rl 1938 00001.01. Barilla Historical Archive, Parma.

Figure 10. Barilla Pasta Fosfina advertisement, ‘Difendiamo la resistenza della razza’ (‘Defend the resistance of the race’), in La Cucina Italiana. Printed in Rome, July 1938.

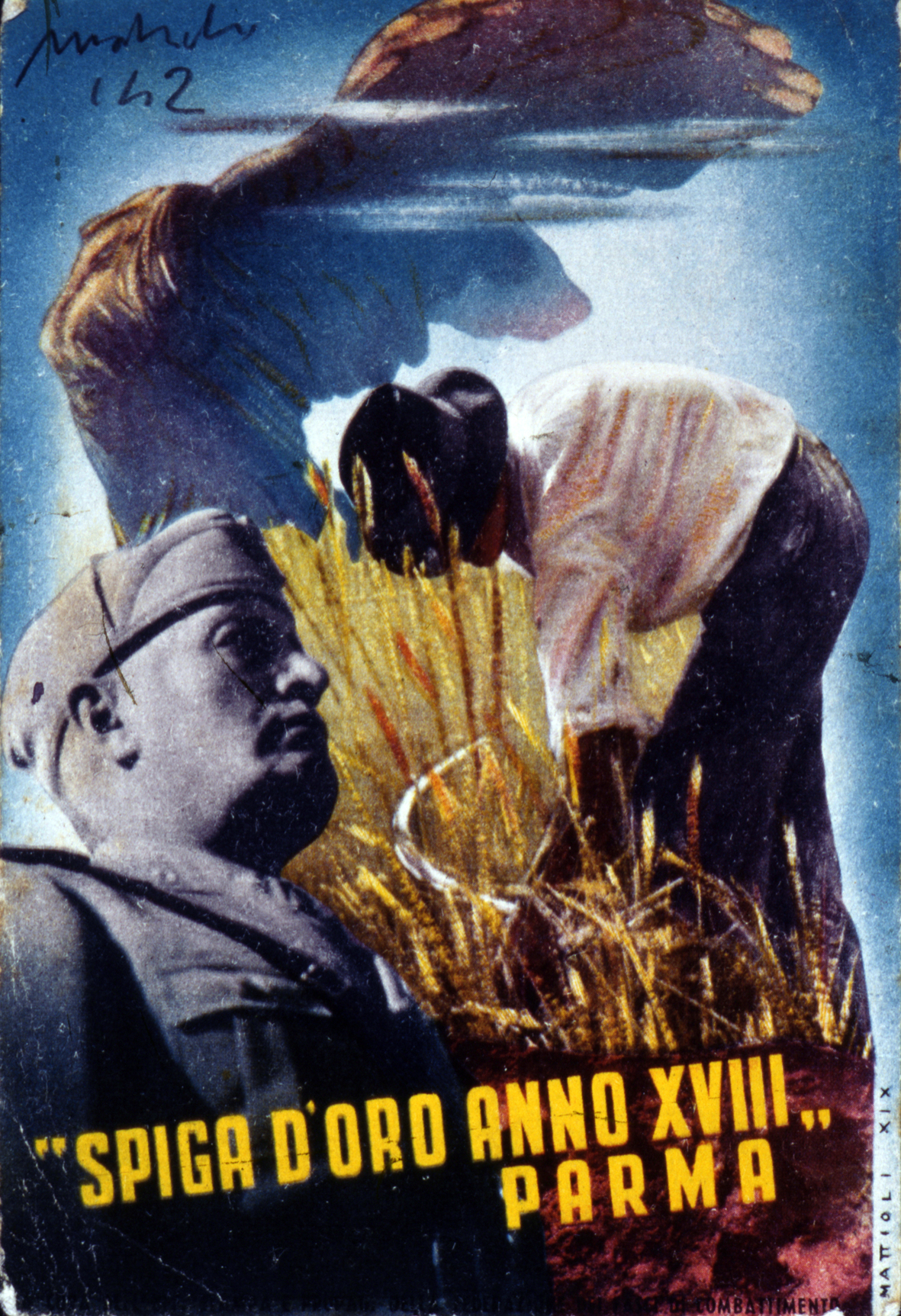

Barilla's colonial soldier was not new. He illustrated one of Barilla's longstanding consumer segments, as a chief pasta supplier to the Italian army. But what was new in these ads was the suggestion that all Italians, male and female, young and old, ought to eat like imperial troops, ingesting nutritious foods to fortify their bodies for war. This campaign and others like it brought new customers and higher revenues to the company. By the late 1930s, Barilla employed 800 people with a daily production of 70,000 kilograms of pasta and 150 kilograms of bread, a relatively new product for this company. Huge amounts of wheat were necessary to supply the Barilla factory, and they drew from nearby fields in Emilia Romagna. Largely due to Barilla's visibility as a national brand, the Parma wheat farming industry took the Spiga d'Oro prize in 1938 (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Postcard commemorating ‘Spiga d'oro Anno XVIII Parma’ (‘The 1940 Golden Wheat Shaft Award for Parma’). Designed by Carlo Mattioli. Postmarked 14 October 1941. Printed by Federazione Fasci di Combattimento, 1940, Parma. Barilla Historical Archive, Courtesy of Pasta Museum, Collecchio, Parma.

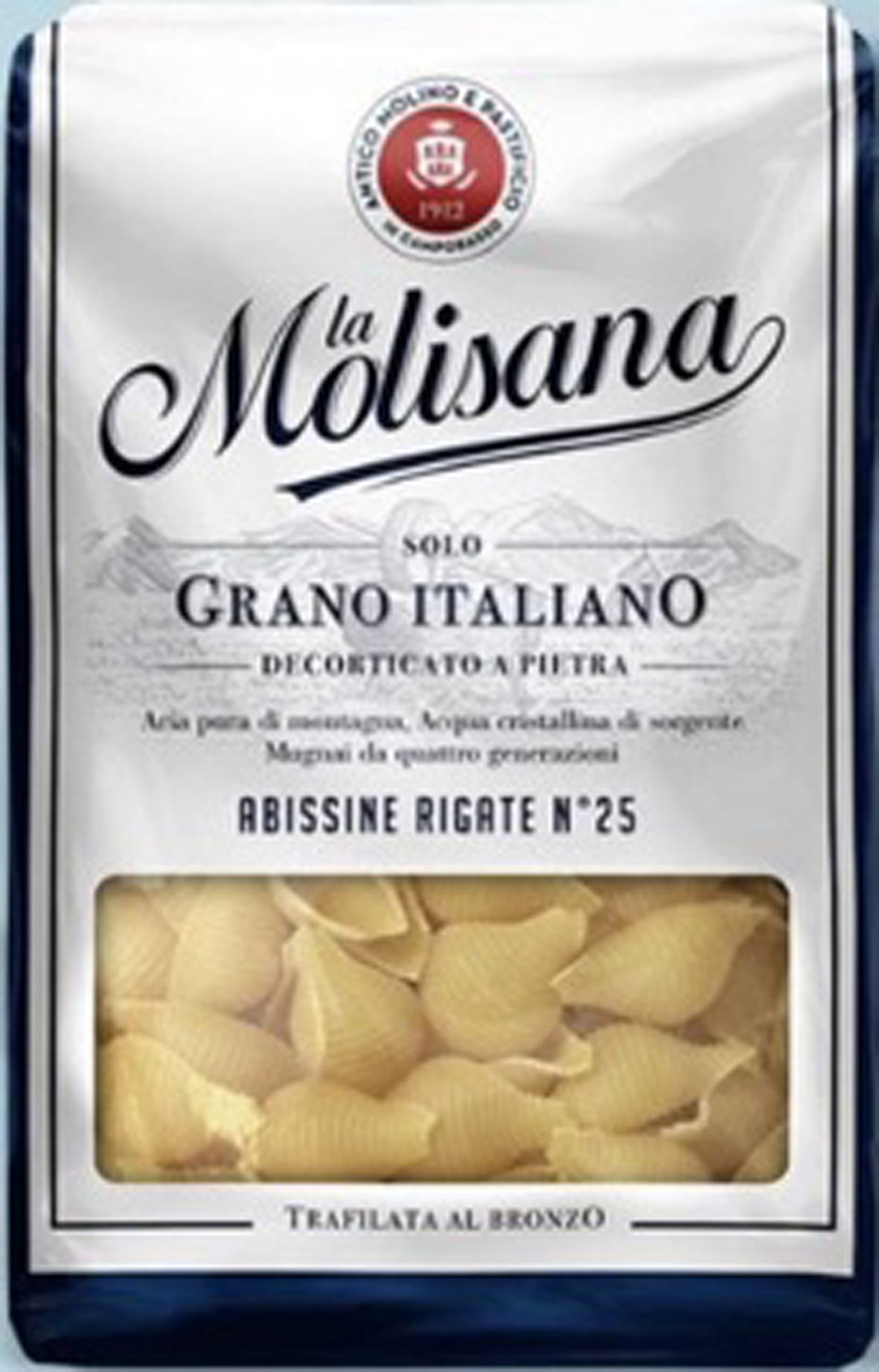

Figure 12. La Molisana ‘Abyssinian pasta’. Photograph from Massimiliano Tonelli, ‘La Molisana e i formati di pasta fascisti. Storia di un'aggressione incredibile’. Gambero Rosso 6 January 2021.

From wheat bread to white ships: 1938 to 1943

A broad raft of Fascist policies aimed to promote Italian industrial development schemes in East Africa, to varying degrees of realisation.Footnote 35 In Addis Ababa, the regime took a top-down approach, overhauling the layout and use of the Merkato Ketema commercial hub, as well as key regional markets in Harar and Quoram, in an attempt to gain control over the Abyssinian empire's taxation system for interior trade of wheat, livestock, coffee, and animal pelts.Footnote 36 In Mogadishu, and in coastal cities like Merca and Brava, the colonial government primarily invested in mercantile infrastructure like refrigerated warehouses, drying plants, and extensions to naval yards. These architectural encroachments aimed to increase shipping speeds for Somali plantation crops like bananas, sugar cane, and cotton to Italian ports in Naples and Genoa.Footnote 37

Interwar promotion of the Italian food industry arguably reached its apex in colonial Eritrea. In 1938, 2,198 companies spread across the industrial and artisanal sectors, employing over 14,000 Eritreans and over 2,000 Italians. Zaccaria notes that Asmara's urbanisation birthed a new figure, ‘the Eritrean labourer – mechanic, driver, carpenter, printer, pasta-maker, baker, tyre-fitter’ (Zaccaria Reference Zaccaria2019). Huge numbers of Eritrean women worked in industry, with the majority in the food and textile sectors. Pasta exports had held steady at 17,100 tons annually through the first years of East African empire, 1936 to 1938 (Chiapparino Reference Chiapparino and Capatti1998). But the base material, grain, continued to flow southward from the metropole to the colonies. Eritrea had imported 127 tons of dried pasta from Italy and exported four to Italy.Footnote 38 Processed grain followed the same pattern, with 6,467 tons of flour exported from Italy to Eritrea and only 35 tons returning. Ethiopia was little better, having imported 129 tons of flour and exported only ten. Advertisements in the Italian-language Asmarino newspaper Il Corriere Eritreo sought to sell their pasta machines.Footnote 39

But 1938 was also a turning point for the Italian colonial government's policies vis à vis wheat consumption. On 4 July Benito Mussolini climbed atop a thresher in the Fascist New Town of Aprilia in the Pontine Marshes to praise the hyper-productive fieldhands of rural Italy. Thanks to ‘nostri fascistissimi contadini’ (‘our most Fascist farmers’), ‘il popolo italiano avrà quindi il pane necessario alla sua vita’ (‘the Italian people will have the bread necessary to life’).Footnote 40 The Duce's propagandistic pose was widely photographed and reproduced in Fascist newspapers and magazines. Less reported was the connection that this announcement had to the ongoing legislation on baking in the East African colonies.

The Italian colonial government intervened at the level of East African bakeries and flour types.Footnote 41 In 1938 from January to June, the Italian ministers of the East African colonies introduced ‘La disciplina della panificazione’, a set of laws that used the colour of consumers’ skin to determine the colour of the bread they were permitted to eat.Footnote 42 Article one dictated the standard bread recipe for Italian military personnel. Loaves for the Italian army and road construction crews should be made from at least 80 per cent local wheat flour, mixed with no more than 10 per cent of local teff, dura, barley, and corn flours, or with imported soft wheat flours.Footnote 43 Article two standardised bread recipes available to Italian colonists: ‘Il pane per la popolazione civile di razza bianca deve essere confezionato con farina di grano, abburattate ali 80% miscelata fino al 20% di farine di cereali locali od importati’ (‘Bread for the white civilian population must be packaged with 80% wheat flour, blended with up to 20% of local or imported cereal flours).’ The legislation included some exceptions. Bakers’ recipes could offer as low as 70–72% wheat if their product was prepared for consumers with special dietary needs, like hospital patients. Italian bread products, such as grissini, were also exempt.Footnote 44 Any baker in possession of pure wheat flour was commanded to immediately sell their stocks to the Azienda Annonaria Governatoriale at the price dictated by the Comitato Vigilanza Prezzi della Federazione Fascista.Footnote 45 On 26 July 1938, governor of Addis Ababa Canero Medici established the bread recipes for East African labourers.Footnote 46 Article two stated: ‘Per l'alimentazione della mano d'opera di colore dovranno essere usate dalle imprese soltanto farine di cereali locali diversi dal grano (dura, taft, orzo, ecc.)’ (‘For the feeding of labourers of colour, only local cereal flours other than wheat (durum, teff, barley, etc.) must be used by companies’. Put telegraphically, Italians were to eat white bread made from wheat, and East Africans were to eat brown bread made from local grains, like barley. Culinary legislation in the colonies centered on questions of racial identification and division. It allotted different foods to different people, based on skin colour.

To enforce the rules, a new Commission for Control of Breadmaking (Commissione di controllo sulla panificazione) was established, consisting of a representative from the Partito Nazionale Fascista, a health inspector, and a baker.Footnote 47 This group would, from time to time, be called from East Africa to make their reports in Rome. Twice a month, this group would inspect the bread ovens from Gondar to Azozò, making sure that their owners obeyed the law. Violators were subject to jail time of up to one month plus a 500 lire fine.Footnote 48

In 1938, the question of East African wheat deficits brought greater Italian attention to ‘cereali minori’, especially the wholegrain teff flour that formed the basis of East African cuisine.Footnote 49 Ethiopian and Eritrean farmers first domesticated teff between 4000 and 1000 BCE. Teff is the smallest grain in the world, measuring just one-hundredth the size of a wheat kernel. It is similar to millet. In terms of taste, teff has an earthy, nutty flavour. Light-coloured varieties can taste slightly sweet. The ancient grain was ground into flour, then fermented to make injera, a flat bread. It also provided base grain for beer production, and thickener for soups, stews, puddings, and porridges. Wholegrain teff is nutrient-dense, high-fibre and gluten-free. Even though teff's pleasant flavour and nutrient density was known at the time, Italian agronomists like Ernesto Massi, a professor at the Milanese Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, were shocked to see that East African markets showed higher demand, and offered higher prices, for Ethiopian teff than for Italian wheat. It was, he admitted, ‘un'altra cultura alimentare’ (‘another food culture’), one that ‘potrà utilmente affiancarsi nelle piantagioni alle culture tropicali d'esportazione’ (‘will be able to usefully complement tropical export cultures in plantations’). But he argued, while teff ‘è molto richiesto dagli indigeni per alimentazione’ (‘is much in demand by the indigenous people for food’), its hardiness meant that it would better serve the Italians as animal fodder, or as a preliminary crop to recover fallow fields (Massi Reference Massi1939).Footnote 50

Less than four months later, the 1938 Race Laws went much further than the colonial legislation on bread and bakeries. On 17 November, these laws restricted the civil rights of Jews living in Italy, and outlawed marriage and madamato relationships between East Africans and Italians.Footnote 51 In 1939, Italy joined Germany in the Pact of Steel, entering the Second World War as a German ally the following year. By this time, the Fascist imperial project was already failing to meet key importation benchmarks set by the regime. Drawing on 1929–1938 ISTAT statistics and Henry Miller's 1938 report Price Control in Fascist Italy, Carol Helstosky observed a sharp decline in the quantity of food available, leading her to conclude: ‘It was the Duce's invasion of Ethiopia, and not the economic crisis of the early 1930s, that had the greatest impact on food-consumption levels in Italy’ (Helstosky Reference Helstosky2004a, 96–97). Italian colonial officials were never able to use the colonies as a granary to support all of the metropole's needs. Ethiopian attitudes towards Italian agricultural interventions ranged from lack of interest to anger, with frequent attacks on the settlements. But even without Ethiopian resistance, the colonial settlements were bound for failure on social and economic grounds, as Larebo (Reference Larebo1994) and McCann (Reference McCann1995) have observed.Footnote 52 Former soldiers did not want to become farmers. As noted by Sbacchi, out of out of a half million soldiers that arrived in 1936, only 15,000 stayed on to farm (Sbacchi Reference Sbacchi1997, 117). Despite the regime's grand plans, colonial settlements were expensive, with one family's homestead costing 150,000 lire, nearly three times the 50,000 lire predicted. They also lacked agricultural specialists and machinery. Only 400 tractors were ever sent to Ethiopia. In short order, Britain wrested control over East Africa from the Italians, and in 1941 Haile Selassie I returned to Ethiopia. Evacuations of the Italian colonists began. Trucks carried colonists overland to the ports, back to the nave bianche, all named for the gods and emperors of Ancient Roman empire: Vulcania, Saturnia, Duilio and the Giulio Cesare. Due to fuel shortages, the massive Rex and Conte di Savoia, that had carried the colonists to Africa, singing the Legionnaires’ anthem at the top of their lungs, could not be used. The Rex remained in Italian hands until 1943, when it was seized by the German government and towed to Trieste, and ultimately destroyed by the Royal Air Force Beaufighters on 8 September 8 1944. Intoning mournful rhyming verses known as the ‘osterie’ songs, the soldiers and former colonists travelled by trucks then by ships, making their way back to Italy.Footnote 53

As the Second World War action snaked up the Italian peninsula, Parma, home of the Barilla headquarters, became a divided town, half Fascist black and half Communist red. Control over the Barilla factory shifted from Axis to Allied hands, with the bread ovens first being seized by German forces, and then commandeered by American soldiers. Similarly, the fortunes of the Barilla family shifted, and then shifted again, as neither the Germans nor the partisans knew where their loyalties lay. Pietro Barilla recalled of the company under Nazi German occupation in 1943: ‘We were remote controlled … the raw materials that were sent to us were poor quality because the mills added more bran than was laid down for the mixes ordered by the government: the white flour was then sold on the black market … then there were the raids, long hours in the shelters …’Footnote 54 During this dark time, the Gestapo knocked on the door. Pietro Barilla and his father Riccardo were accused of sending money to the partisan forces gathering in the hillsides outside town. After three days of questioning, Himmler's police finally released the Barillas after they signed a statement swearing that the pasta factory would not provide financial support to the partisan bands, under penalty of death. But the partisans too had their doubts about the Barillas’ position.Footnote 55 Through the variable political currents, the company remained in business. Even up to 1944, Barilla still employed 298 workers. Meanwhile, the Fascist Party was dissolved, and Mussolini was captured and executed in 1945, at the end of the Second World War.

After Liberation, the partisans pasted posters on every wall in Parma calling for Pietro Barilla's arrest. The prints included a picture of a Christmas card, sent by Barilla to a German official, which was presented as evidence of company collaboration. Looking back decades later, Barilla defended himself: ‘He was from Stuttgart and he was not a Nazi: he was our controller, the contact required for obtaining more raw materials, petrol coupons, permits for distributing bread and pasta. At the end of the year, I had sent him the usual gifts that are sent to authorities: some spumante, some torrone. And a Christmas card.’Footnote 56 Pietro Barilla presented himself at San Francesco, the Parma town jail, and spent the next few days incarcerated with a mix of former Fascist police, and ‘poor bureaucrats overwhelmed by the end of the regime’. By the end of the week, Barilla was a free man. Over 600 Barilla workers signed a petition for his freedom, and he was released to continue work at the factory. The incident illustrates how one company town struggled with the question of how to address the entanglement of Fascism and industry after the fall of the regime. With the Paris Peace Treaty of 1947, Italy formally abandoned claim to all former colonies, and the majority of agricultural schemes and industrial claims that lay therein.

Di sicuro sapore littorio: legacies of imperialism in the Italian pasta industry

Though of great symbolic importance as the nation's archetypal food, Italian pasta's economic value cratered in the postwar years. Black markets and the disintegration of international trade agreements hampered Italian pasta export, depressing overall demand. During the difficult postwar years from 1945 to 1948, Italy imported pasta from the United States. By the late 1940s, Italian pasta exports had all but disappeared from the international marketplace (Scarpellini and Mazhar Reference Scarpellini and Mazhar2016). With the shift in the political winds, some companies found an advantage. Due to conflicts with local Fascist representatives in the 1930s, Buitoni had already transferred some manufacturing across the Atlantic, and was thus able to continue exporting pasta from the United States throughout the 1940s (Chiapparino Reference Chiapparino and Capatti1998). Many small, family-owned and -operated pasta companies also managed to survive. As Messina observes, many scholars have faulted the family-based model as a ‘determining factor of weakness and lack of progress in the food industry’. And yet, the small size of these firms ‘made it possible to wait for better times, delaying the distribution of profit, when necessary – and returning to growth during the new economic miracle of the 1950s’ (Messina Reference Messina2015).

Today Italy is the world's leading exporter of dry pasta, producing roughly 25–30 per cent of the world's total. (UNAFPA data, cited in Messina Reference Messina2015). From the economic boom to the present day, Italian pasta production has increased continually. The 1.9 million tons of bucatini exported each year account for 55 per cent of Italy's national production, with a value of 2 billion euros. But it is only in recent years that economic historians have begun to explore the Italian pasta industry's relationship with corporatism and the East African colonies during the politically fraught years of the Fascist ventennio. This new research is in part possible due to the opening of key business archives, including those of Agnesi, Barilla, and Buitoni-Perugina.Footnote 57 As Messina has noted, ‘there is still a lack of research on their history, the strategies they pursued, their performance and their structural and technological innovation … neither do we have studies which could give new insights into the relationship of the food and pasta industries to the domestic pattern of development and the process of globalization’ (Messina Reference Messina2015). This article is, in part, an attempt to chronicle the history of Italian food business during this period.

In 2021, La Molisana pasta company came under fire for their release of ‘Abyssinian pasta’, a naming procedure harkening back to colonial food naming practices. Their product catalogue and website described the history of the pasta:

Negli anni Trenta l'Italia celebra la stagione del colonialismo con nuovi formati di pasta: Tripoline, Bengasine, Assabesi e Abissine. La pasta di semola diventa elemento aggregante? Perché no!…

Di sicuro sapore littorio, il nome delle Abissine Rigate all'estero si trasforma in ‘shells’ ovvero conchiglie.

In the Thirties Italy celebrated the age of colonialism with new pasta shapes: Tripoline, Bengasine, Assabesi and Abyssinian. Does semolina pasta become a unifying element? Why not!…

Certainly a lictorian flavour, the name of Abyssine Rigate abroad is transformed into ‘shells’.

Abyssine rigate #25 was not the only pasta produced by the company to bear a colonial association. The back of the box for Tripoline #68 read ‘Il nome evoca luoghi lontani, esotici e ha un sapore coloniale’ (‘The name evokes exotic, far-away places, and has a colonial flavour’).Footnote 58 The descriptions came to light when a photographer, Nicola Bertasi, captured and posted a screenshot of the company's web description on Twitter at 12:32pm on 4 January 2021. Bertasi added the caption ‘Dopo le vicissitudini dell'omofoba Barilla finisce anche il mio rapporto con “la fascista” Molisana. Garofalo non mi tradire. Pasta Garofalo per favore. Quanto lavoro c’è ancora da fare (‘After the vicissitudes of homophobic Barilla, my relationship with “the fascist” Molisana also ends. Garofalo don't betray me. Pasta Garofalo please. How much work remains to be done.’) It shows the ongoing interconnection of Italian politics and pasta, from Guido Barilla's homophobic commentary on ‘La Zanzara’ in 2013 to the Molisana packaging.Footnote 59 The debate expanded, with representatives from ANPI (the National Association of Partisans) as well as former UN officials and presidents of the Chamber of Deputies all weighing in. Rossella Ferro from La Molisana provided an interview with La Repubblica the next day, stating that La Molisana had not meant to exalt Italian colonialism. That day, the ‘Abissine Rigate’ became ‘Conchiglie’, and the ‘Tripoline’ became ‘Farfalline’, which, as mentioned previously, was the name used by Barilla before inaugurating, and subsequently retiring, their ‘Tripoline’ pasta shape line in the 1930s. La Molisana also posted an apology to their website

Ci scusiamo per il riferimento riguardante I formati di pasta Abissine rigate e Tripoline che hanno rievocato in maniera inaccettabile una pagina drammatica della nostra storia. Cancellare l'errore non è possibile, ci stiamo già impegnano a revisionare i nomi e i contenuti dei formati in questione attingendo alla loro forma naturale.

We apologise for the reference regarding the ridged Abyssinian and Tripolitan pasta shapes which have unacceptably evoked a dramatic page in our history. Erasing the error is not possible, we are already committed to revising the names and contents of the formats in question, drawing on their natural form.

Italian cuisine is itself famously conservative, slow to change its ingredients and recipes. Food thus provides a charged venue for contemporary debates regarding culinary nationalism and the so-called purity of Italian cuisine. But traditional Italian food is a moving target. The iconic Italian tomato was once an exotic New World import, widely considered to be poisonous. Italian food companies, especially those whose industrial history extends back to the ventennio, are now in a unique position. Whether due to product names, recipes, or previous government ties, they can tell a certain story of Italy's East African empire. To put La Molisana's media firestorm into a broader perspective, we might treat consumable products, like pasta, as objects of debate, as we do with monuments and museums. They become all the more important in the face of political movements that attempt to resurrect idealised versions of the national past (Figure 12).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the American Academy in Rome, the Fulbright Global Scholar Award, the APS Franklin Research Grant, and the Trinity College Barbieri Research Grant in Modern Italian History. The author is grateful to these institutions, and the two anonymous reviewers of this manuscript for their insightful recommendations and intellectual generosity.

Competing interests

The author declares none.

Diana Garvin is an Assistant Professor of Italian with a specialty in Mediterranean Studies. Her book, Feeding Fascism: The Politics of Women's Food Work, was published by University of Toronto Press in 2022. Garvin works in the Department of Romance Languages at the University of Oregon. She conducted her postdoctoral research at the American Academy in Rome as the 2017–2018 Rome Prize winner for Modern Italian Studies. Garvin received her PhD in Romance Studies from Cornell University, and her AB from Harvard University.