Introduction

Migration flows of ex-colonials and labor migrants looking for a new home have been part of the Western European countries’ reality since the mid-20th century. In contrast, Poland has been considered a relatively homogenous society in terms of ethnicity and religion, and traditionally the immigration issue has been far less discussed than the emigration of Poles to other countries (Kotras Reference Kotras2016; Żołędowski Reference Żołędowski2020).Footnote 1 According to Poland’s national census from 2011, only 0.2% of respondents declared themselves to be foreign nationals, and almost 89% of those who answered questions about their religious affiliation acknowledged the Roman Catholic faith (GUS 2012, 2014). In the first few years after the census, the number of residence permits granted by Poland to foreign nationals remained relatively low, in comparison with other European Union countries, and up until 2015, the salience of the immigration issue in public debate was negligible (Górny et al. Reference Górny, Grzymała-Moszczyńska, Klaus and Łodziński2017; Horolets et al. Reference Horolets, Mica, Pawlak and Kubicki2020).

However, as the migration crisis and the EU discussions about a relocation program coincided with the parliamentary election campaign in Poland in 2015, the migration issue “stepped out of the shadows” and became broadly discussed, not only by the media but also by the politicians who used it as an effective means of mobilizing voters and gaining political power (Kubicki et al. Reference Kubicki, Pawlak, Mica and Horolets2017).

At that time the main opposition party – Law and Justice – did not accept the proposed migrants’ redistribution system and asserted the idea of inviolable national sovereignty. The representatives of the party held that each state should have the right to decide on the number of immigrants in its territory. They warned against the danger of Muslim immigrantsFootnote 2 unwilling to respect Polish laws and customs, trying to impose their way of life on Polish society, and thus undermining Poland’s national identity and traditional values (Szczerbiak Reference Szczerbiak2017). The Law and Justice party gained significant support from the conservative and nationalistic part of the population and won the general election of 2015. While keeping alive the nationalistic and anti-immigration public discourse in Polish society, they managed to succeed in the following parliamentary election in 2019, too.

Nevertheless, once the Law and Justice came to power, its opinion on immigration became much less straightforward. In 2015 and 2016, Poland was the second-highest country, surpassed only by the United Kingdom, which issued more residence permits to non-EU citizens than any other EU-member state. In 2017, 2018, and 2019, Poland took first place (Eurostat 2020). However, these citizens were not refugees from Syria or other Middle Eastern countries. As of December 2019, by far the most numerousFootnote 3 nation group among those with temporary or permanent residence permits are Ukrainians. According to the Polish Central Statistical Office (GUS), the number of Ukrainian citizens holding a residence permit in Poland rose from 7,168 in 2014 to 107,103 in 2019, and work permits issued to Ukrainians in this period increased even more: from 26,315 to 330,495 (GUS 2015, 2020). And this case continued after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, when Poland has accepted the highest number of Ukrainian refugees (data2.unhcr.org, May 3, 2022).

Poland thus undoubtedly presents the unique case of a two-faced immigration strategy, which raises the question: Are the citizens’ responses to immigration also unique to Poland?

According to recent cross-national comparisons (see Figure 1 for ESS data from 2018 or, for example, Ray, Pugliese, and Esipova Reference Ray, Pugliese and Esipova2017 and Esipova, Ray, and Pugliese Reference Esipova, Ray and Pugliese2020 for Gallup World Poll 2016-2019, Global Views on Immigration and Refugee crisis from IPSOS 2017, and Gonzalez-Barrera and Connor 2019), Eastern European countries display much greater opposition to immigrants than countries of Northern and Western Europe, even though their countries only have a small population of foreign-born citizens (Ray, Pugliese, and Esipova Reference Ray, Pugliese and Esipova2017; Esipova, Ray, Pugliese Reference Esipova, Ray and Pugliese2020; Gonzalez-Barrera and Connor 2019). The strongest negative sentiments are observed in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, followed by Bulgaria and Poland. Other post-communist countries included in the sample, such as Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia, also show significantly lower support for immigration than most Western European countries. While less than 4% of Icelanders stated that they would accept only a few or no immigrants of the same ethnicity, in Poland this figure was more than 40% and in the Czech Republic, it was 57%. Regarding immigrants of different ethnic backgrounds, 27% of Germans chose to accept only a few (23.5%) or none (3.6%), while in Poland this was more than 64%, in Slovakia 75%, and in the Czech Republic more than 78%.

Figure 1: Cross-National Comparison of Attitudes to Immigration

Data source: ESS Data, Round 9

Note: X-axis describes ESS countries (Hungary is omitted due to lack of data); Y-axis includes a range from 1 (Allow many to come and live here) to 4 (Allow none).

Indeed, as theory suggests, while the nationalism of Western Europe is characterized by a stress on the importance of democratic governance and civil liberties (Kohn Reference Kohn1946; Snyder Reference Snyder1968), ethnically oriented nationalism, typical of the Eastern Europe, on the other hand, advocates nativism and an exclusionary approach to citizenship (Kohn Reference Kohn1946; Brubaker Reference Brubaker2017), and this can be, alongside economic factors (Mayda Reference Mayda2006), Footnote 4 one possible explanation for the declared hostility to newcomers, especially if this issue is politicized and becomes salient in the public discourse as it happened in the Visegrád Four countries and Austria (see the shift toward more restrictive opinions on immigration in Poland in Figure 2, Table 1 and Table 2).

Figure 2: Opposition to Immigration Development in Poland 2002–2018

Data source: ESS data, Poland, Round 1–9

Note: X-axis describes ESS rounds 1–9; Y-axis includes a range from 1 (Allow many to come and live here) to 4 (Allow none).

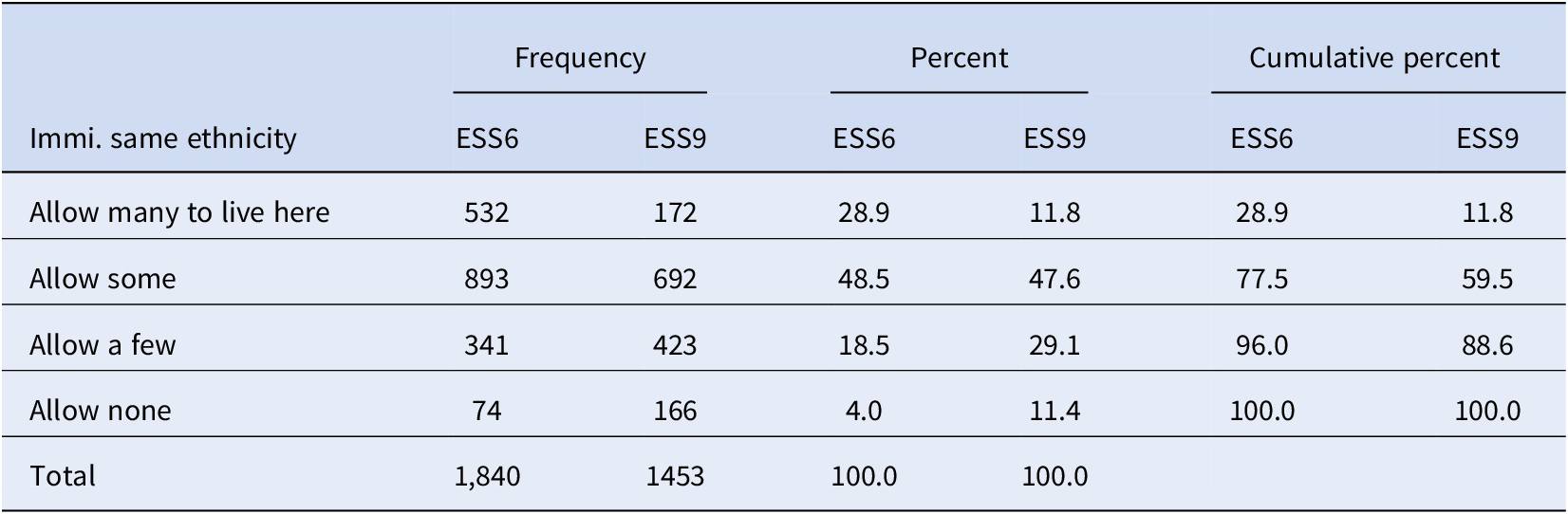

Table 1. Distribution of Attitudes toward the Immigration of People of the Same Ethnicity

Data Source: ESS Round 6 & ESS Round 9, Poland

Table 2. Distribution of Attitudes toward the Immigration of People of a Different Ethnicity

Data Source: ESS Round 6 & ESS Round 9, Poland

This article aims to contribute to the debate on anti-immigration attitudes in different countries by focusing on an East European representative, Poland. This article will compare the rationale behind the rejection of immigrants with studies of other societies, and it will attempt to find factors that explain the differences in sentiments toward people of diverse ethnic backgrounds. The proposed research will seek to provide answers to the following questions: Is negative opinion on immigration in Poland influenced by economic considerations (personal and collective), or is it more driven by the defense of cultural identity? Is the main trend that explains the rejection of immigrant minorities in Poland different from that identified in studies of the relatively richer countries of Western Europe and North America? Could we observe any dissimilarities in Poles’ views on citizens of European states and the people of non-European origin when related to members of both groups intending to reside in Poland?

Social Identity or Economic Self-Interest? Theories and Explanations

There is a long history of academic debate trying to explain what engenders negative attitudes toward immigration. Various studies have attempted to explore the causes of hostility toward foreigners and to find why some societies are generally more welcoming to immigrants than others. Up to now, the scholarly research on the acceptance of immigrant minorities has been mostly focused on Western European countries, Canada, and the United States – countries with significant numbers of foreign-born people (see Hainmueller and Hopkins Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014). However, little attention has been paid to the countries of Eastern Europe, as most of them have not been particularly affected by immigration flows, until recently. As was mentioned above, in Eastern European countries we have observed a significant drop in the willingness to support immigration since 2015, despite the relatively negligible rise in the number of immigrants to those countries. This phenomenon has not yet been thoroughly described; however, it suggests to us that people’s individual beliefs rather than the actual number of immigrants matter the most.

The two most prominent theoretical approaches of research into the acceptance or rejection of immigrants which are believed to be relevant in gaining an understanding of people’s opinions and behavior revolve around, on one hand, the issue of self-interest, and on the other hand, the role of social identity. The first primarily describes individual economic concerns and identifies competition for resources as a crucial factor in the rejection of immigrants, while the second theory explains antipathy for foreigners in terms of apprehension that minorities would undermine the traditional culture and shared customs of the host country. There are also authors who, in their anti-immigration research, use details from political and media campaigns (Barna and Koltai Reference Barna and Koltai2019; Boomgarden and Vliegenthart Reference Boomgarden and Vliegenthart2009; Branton et al. Reference Branton, Cassese, Jones and Westerland2011; Valentino et al. Reference Valentino, Brader and Jardina2013), while others refer to contact theory and neighborhood effects (Citrin et al. Reference Citrin, Green, Muste and Wong1997; Scheve and Slaughter Reference Scheve and Slaughter2001; Hopkins Reference Hopkins2011) as well as individual security fears (Duman Reference Duman2015) and more complex sociological and psychological concepts, such as social capital (Herreros and Criado Reference Herreros and Criado2009) and basic human values (Van Hootegem, Mueleman, and Abts Reference Van Hootegem, Meuleman and Abts2020).

Even though a larger part of recent studies considers collective cultural threat (as a component of the social identity theory) to be the most substantial cause of opposition to immigration (see literature review on Public Attitudes Toward Immigration by Hainmueller and Hopkins Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014), it is important to note that these studies often neglect to acknowledge the origins of the foreigners. Naturally, these concerns should be less relevant when the minorities come from a similar cultural background to the host country. As Van Hootegem, Meuleman, and Abts (Reference Van Hootegem, Meuleman and Abts2020) and Green et al. (Reference Green, Fasel and Sarrasin2010) confirm, regardless of any dissimilar historical, socio-cultural, or demographic context in the observed countries, differences in their hostility level to foreigners might be partly caused by the ethnicity of the immigrants. Individual-level data from European countries show a clear difference between the acceptance of immigrants from Europe and those of different ethnic or racial origins, and this suggests we should study these phenomena separately. By using survey data, we can distinguish between people’s opinions on the in-group and out-group citizens, and we can control for other variables that may explain the attitudinal shift that occurred in countries that have not had a significant rise in the number of immigrants.

In the existing literature relating to self-interest as an explanation for animosity toward minorities, there are several determinants believed to influence people’s acceptance or rejection of immigrants in their country – such as low level of education, unsatisfactory income, unemployment, etc. In general, those studies suggest that anti-immigration attitudes are associated with low socioeconomic status and dissatisfaction with the economic situation – both on the macro-level of the economic prosperity of the country (e.g. Citrin and Sides Reference Citrin and Sides2008), and on the level of the personal situation of individuals (Cook et al. Reference Cook, Dwyer and Waite2012; Citrin et al. Reference Citrin, Green, Muste and Wong1997; Herreros and Criado Reference Herreros and Criado2009; Bandelj and Gibson Reference Bandelj and Gibson2020; Oliver and Mendelberg Reference Oliver and Mendelberg2000; Olzak Reference Olzak1992; Mayda Reference Mayda2006; Scheve and Slaughter Reference Scheve and Slaughter2001). It is argued that nationals who are at the bottom of the labor market feel threatened by immigration because they reckon immigrants as mostly unskilled workers and cheap labor; individuals who may compete with them for work opportunities and/or welfare benefits (Espenshade and Hempstead Reference Espenshade and Hempstead1996). Hence, we should expect a poor economic performance and unsatisfactory personal financial situation to be factors that reduce citizens’ support for immigration.

While the self-interest theory proves to be plausible in some cases, there has been a growing consensus that social identity theory, which concerns immigration’s impact on a group’s well-being, rather than on an individual’s prosperity, is much more influential (Card, Dustmann, and Preston Reference Card, Dustmann and Preston2012; Haimueller and Hopkins Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014). This theory is based on the assumption that an individual’s identity is, to a great extent, determined by group belonging. Therefore, not only do people tend to see the groups they are members of in a more positive light, but because of their prejudices, they are often hesitant to accept foreign elements that might interfere with their group’s integrity (Tajfel Reference Tajfel1981). This theory may not only explain the general suspicion of foreigners but also the distinctions people make in their appraisal of immigrants based on their origins. Relying on social identity theory, the cultural threat hypothesis suggests that nationals tend to protect their culture and collective identity which, they believe, can be threatened by immigrants (Sniderman, Haagendorn, and Prior Reference Sniderman, Hagendoorn and Prior2004).

Moreover, the cultural threat is not the only channel through which social identity shapes attitudes to immigration. Religious beliefs can also be a factor in explaining the variation in anti-immigration sentiments. While some studies (e.g. Scheepers, Gisbert, and Hello Reference Scheepers, Gijsbert and Hello2002; McDaniel, Nooruddin, and Shortle Reference McDaniel, Nooruddin and Shortle2011) have found a negative correlation between religiosity and acceptance of immigrants, others (Boomgaarden and Freire Reference Boomgaarden and Freire2009; Lubbers, Coenders, and Scheepers Reference Lubbers, Coenders and Scheepers2006; Knoll Reference Knoll2009) have observed that religious beliefs can fuel feelings of sympathy for asylum seekers. Bloom, Arikan, and Courtemanche (Reference Bloom, Arikan and Courtemanche2015) point out that these discrepancies are mostly based on the particular religious and ethnic backgrounds of immigrants. While religious identity produces welcoming attitudes toward individuals who share the same ethnicity and faith, it has the opposite effect on immigrants whose ethnic background and religious beliefs differ from the majority of the population. The social identity theory suggests that identification with a religious group leads to stronger negative sentiments toward immigrants, especially when they do not share common religious or ethnic backgrounds and are thus viewed as an identity threat (Brader, Valentino, and Suhay Reference Brader, Valentino and Suhay2008). On the other hand, the religious compassion hypothesis proposes the idea that religion teaches its followers the necessity of compassion and caring for those in need. This theory presumes that religiosity should contribute to more positive feelings toward immigrants, and even more so if they are from similar socio-cultural and ethnic backgrounds (Norenzayan Reference Norenzayan2013). Nevertheless, it is important to keep in mind that some of the inconsistencies in the research could be simply caused by different measurements or diverse concepts of religiosity, too (see Smidt, Kellstedt, and Guth Reference Smidt, Kellstedt, Guth, Smidt, Kellstedt and Guth2009).

Data and Operationalization

The study of anti-immigration attitudes in contemporary Polish society is based on data from the European Social Survey (ESS). This international cross-country survey has been conducted every two years since the year 2002 in several European countries. This ensures that all the analyses will be reproducible in the future and comparable across countries. All the datasets include a battery of immigration-related questions. Figure 1 uses all available samples from countries that participated in Round 9. For the construction of Figure 2, Polish data from Rounds 1–9 are used. The main analysis, however, is only based on the Round 6 and Round 9 data, with the focus solely on Poland. The survey data from Round 6 was collected between September 22, 2012 and February 9, 2013 and the data from Round 9 was collected between October 26, 2018 and March 20, 2019. The datasets are comprised of answers from 1,989 and 1,500 respondents respectively.

In compliance with the ESS weighting manual (European Social Survey 2014), to minimize possible bias which can result from coverage, sampling, and non-response errors, post-stratification and design weight are used before running the analyses.

Dependent Variables

The presented analyses were performed on two dependent variables – attitudes toward the immigration of people of the same ethnicity, and attitudes toward those of different ethnicity. The responses were taken over two different periods. The first dependent variable is operationalized as the question: “To what extent do you think Poland should allow people of the same race or ethnic group as the majority of Poland’s citizens to come and live here?” with possible answers on a 4-point scale, with 1 being “allow many to come and live here,” and 4 “allow none” (see Table 1). The second dependent variable is operationalized as the same question with the same possible answers but refers to people of a different race or ethnic group from the majority of Poland’s citizens (see Table 2).

Explanatory Variables and Their Operationalization

To test the economic self-interest theory, three indicators are included in the analysis. The first measures the respondents’ income. Rather than asking about the actual income, a question about satisfaction with their income is used. For two reasons – the first is the general unwillingness of some respondents to answer questions about their salaries (they refuse to answer, or they lie), and the second concerns personal and regional differences; meaning that everyone has different expenses and what might be a reasonably high salary for someone in a small town may hardly cover the cost of essential goods for someone living in a bigger city (note that there are significant economic differences across Poland). After all, it should be their personal feelings about the issue, not the exact financial amount, that affects peoples’ values and opinions. The question “How do you feel about your household’s income nowadays?” is measured on a 4-point scale, where 1 equals “living comfortably on present income” and 4 equals “finding it very difficult on present income” (ESS Round 9 2020).

The second indicator used to test the economic self-interest theory concerns the respondents’ unemployment. This is used as a dummy variable and it includes people who declared themselves to be unemployed and actively looking for work (ESS Round 9 2020).

The third variable for testing the self-interest theory is the respondents’ level of education. While there have been two opposing theories concerning the relationship between education and choice of immigration policy, the more widely held view is that the higher the education, the higher the support for immigration, or conversely, as this article focuses on negative attitudes toward immigration, the lower the education, the stronger the negative feelings toward immigrants. This variable is measured as total years of completed full-time education (ESS Round 9 2020).

As regards the theory of social identity, questions related to religiosity and cultural threat are its main determinants for this analysis. The first indicator – cultural threat – is based on the question “Would you say that Poland’s cultural life is generally undermined or enriched by people coming to live here from other countries?” This variable is also measured on an 11-point scale, ranging from zero “cultural life enriched” to 10 “cultural life undermined.” (ESS Round 9 2020).

The second social identity determinant – religiosity – can be measured in several ways, each of which could lead to different conclusions. To avoid multicollinearity, only the question “How religious would you say you are?” – which is expected to be negatively correlated with opinions on immigration – is used in this analysis. It is measured on an 11-point scale, where zero means “not at all religious” and 10 is “very religious” (ESS Round 9 2020).

Besides the main competing theories – self-interest and social identity – alternative explanations will also be tested. Therefore, economic threat, interpersonal trust, perceived neighborhood safety, satisfaction with government, and three basic human values of security, universalism, and conformity-tradition are included in the models.

As Citrin et al (Reference Citrin, Green, Muste and Wong1997) and Dancygier and Donnelly (Reference Dancygier and Donnelly2012) conclude, restrictionist views are more driven by concerns relating to the overall impact of migrant labor on the national economy rather than by self-interest. Variable economic threat is based on the question “Would you say it is generally bad or good for Poland’s economy that people come to live here from other countries?” This is measured on an 11-point scale ranging from zero to 10, where zero equates to “good for the economy” and 10 equates to “bad for the economy” (ESS Round 9 2020).

In line with previous research (e.g. Ekici and Yucel Reference Ekici and Yucel2015 or Herreros and Criado Reference Herreros and Criado2009) we also expect interpersonal trust to determine people’s responses to the immigration issue. Therefore, the following question is added to the model: “Would you say that most people can be trusted, or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people?” The scale of the answers ranges from a score of zero to 10, where zero means “most people can be trusted” and 10 means “you can’t be too careful” (ESS Round 9 2020). We assume that generally, less-trusting people would be less accepting and more mistrustful and judgmental toward foreigners.

Another possible explanation for animosity toward immigrants is personal security and safety concerns. Although few empirical studies on anti-immigration attitudes incorporate this issue, it remains one of the topics most frequently addressed by anti-immigration political parties (Duman Reference Duman2015). As anti-immigration sentiments are often associated with uncertainty or fear regarding possible increased criminality due to immigrants from poorer countries, we expect higher levels of fear and anxiety when people are walking alone in their neighborhood after dark to trigger unspecified negative responses to the very idea of immigration (Rustenbach Reference Rustenbach2010). The variable neighborhood safety is framed in the following question: “How safe do you feel walking alone in this area after dark?” This is measured on a 4-point scale, with 1 standing for feeling “very safe” and 4 for “very unsafe” (ESS Round 9 2020).

Satisfaction with government should also be considered as a factor that shapes opinions on immigrants as it is the government that is responsible for immigration policy management. This variable is measured on an 11-point scale, where zero is for “extremely dissatisfied” and 10 for “extremely satisfied” (ESS Round 9 2020).

Political interest as a key indicator of political sophistication acted as a moderator of anti-immigration attitudes in some people and therefore is also important to be controlled for. It is measured on a 4-point scale, where 1 means “not at all interested” and 4 means “very interested” (ESS Round 9 2020). A higher level of political interest is associated with less frequent negative opinions about foreigners, and so it should appear negative in the model.

Additional to the previous explanations, Van Hootegem, Meuleman, and Abts (Reference Van Hootegem, Meuleman and Abts2020) point out that in anti-immigration research we should also not ignore the role of basic human values. These values serve as guiding principles in human lives and help people shape their views on societal issues, such as immigration. A value of universalism emphasizes understanding, tolerance, and the protection of universal welfare (Schwartz Reference Schwartz1994, 22) and in our model, it is based on three ESS variables: the importance of treating everyone equally, listening to dissimilar people, and caring for nature and the environment. A joint value conformity-tradition which concerns complying with social norms and expectations, including respect for and preservation of customs and traditions (Schwartz Reference Schwartz1994) is a latent variable composed of four variables from the ESS survey: the importance of doing what you are told, being humble and modest, behaving properly, and following traditions and customs. A confirmatory factor analysis proved the validity of these two latent constructs and regression scoring based on varimax rotated factors was used to create the two new variables. Another Shalom H. Schwartz value – security – should also be considered as a factor associated with attitudes toward immigrants. This variable is based on the declared importance to live in secure surroundings and avoiding anything that might endanger one’s safety. All the original questions are measured on a 6-point scale giving the respondents’ identification with the proposed values. 1 is for “very much like me” and 6 for “not at all like me” (ESS Round 9 2020). While universalism is expected to foster an accepting approach, both conformity-tradition and security should be associated with more restrictive attitudes.

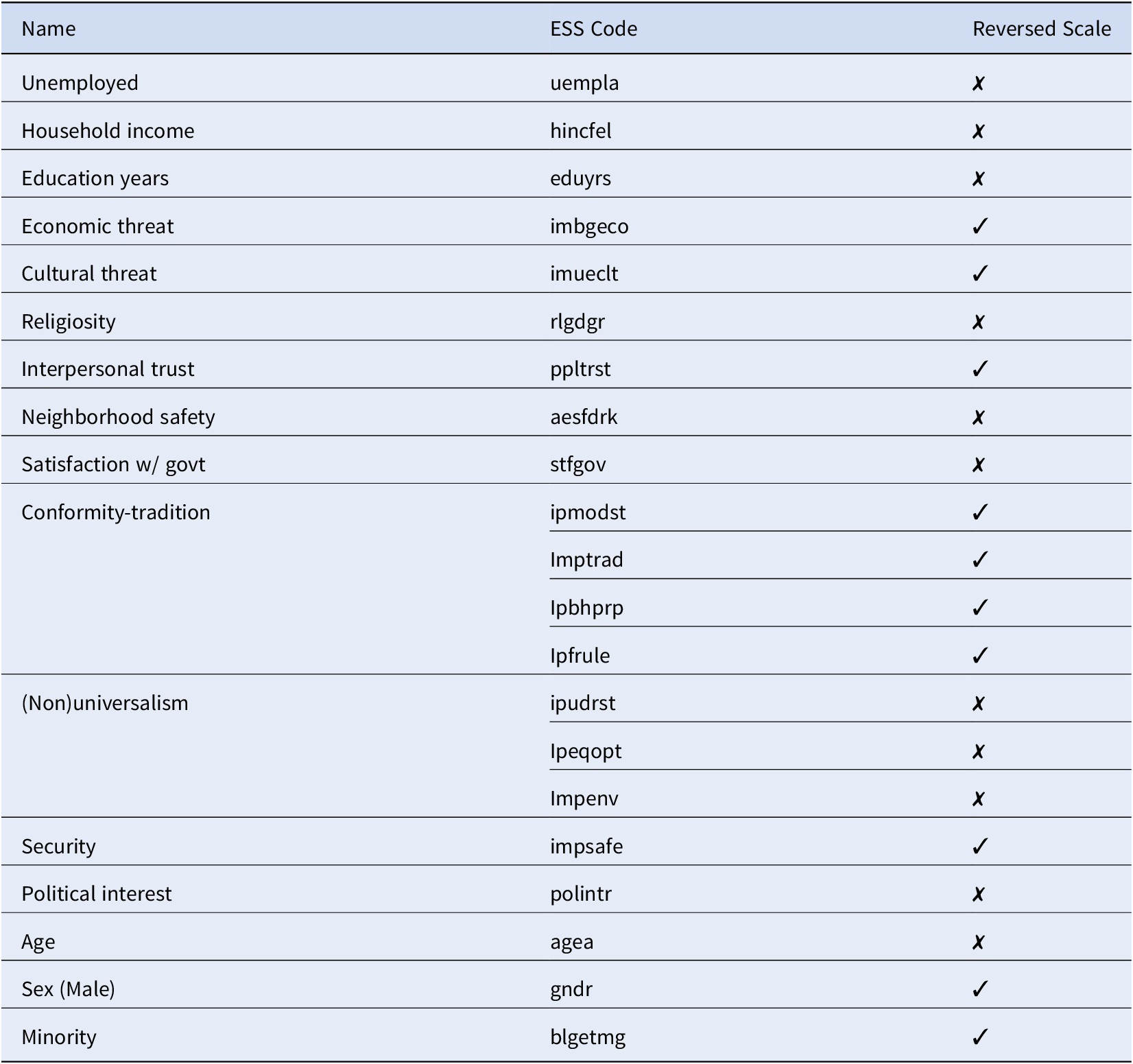

Finally, socio-demographic variables that achieved statistical significance in previous research, such as gender (male), age, and ethnic minority status, are also included in the model as control variables.

The response scales of all predictors were reversed, so in compliance with theories referred to in this article, a higher number indicates a stronger anti-immigration attitude. For easier interpretation, ordinal variables are treated as continuous. For the full list of variables used in this article see Appendix 1.

Results and Discussion

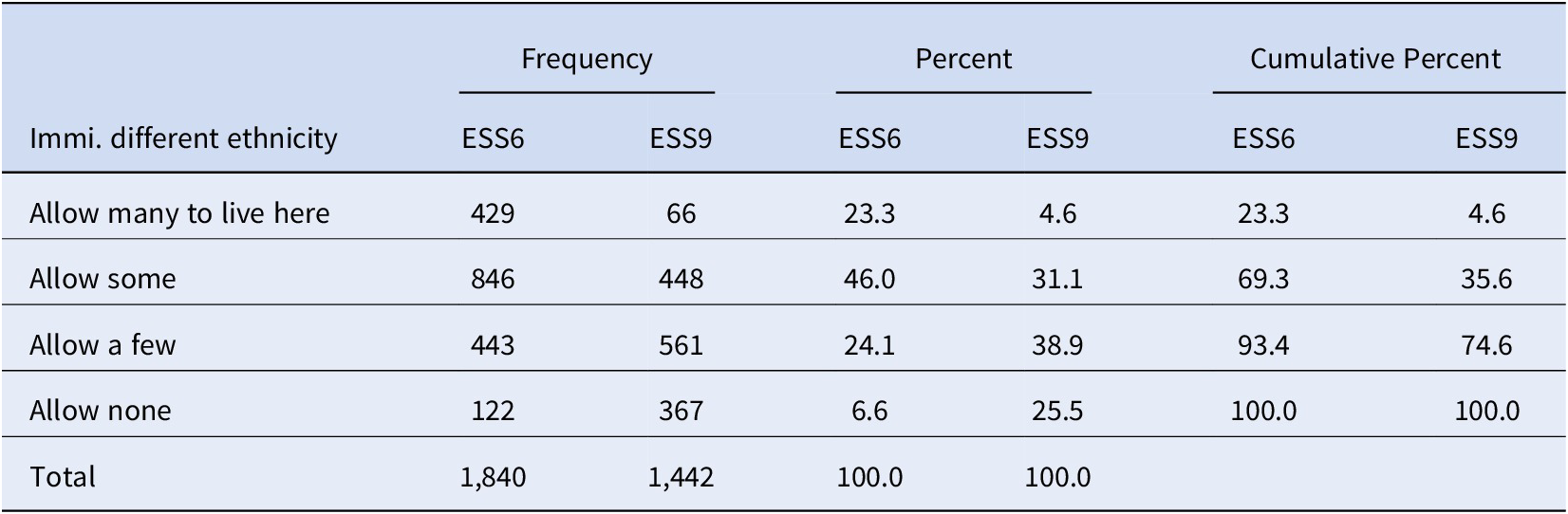

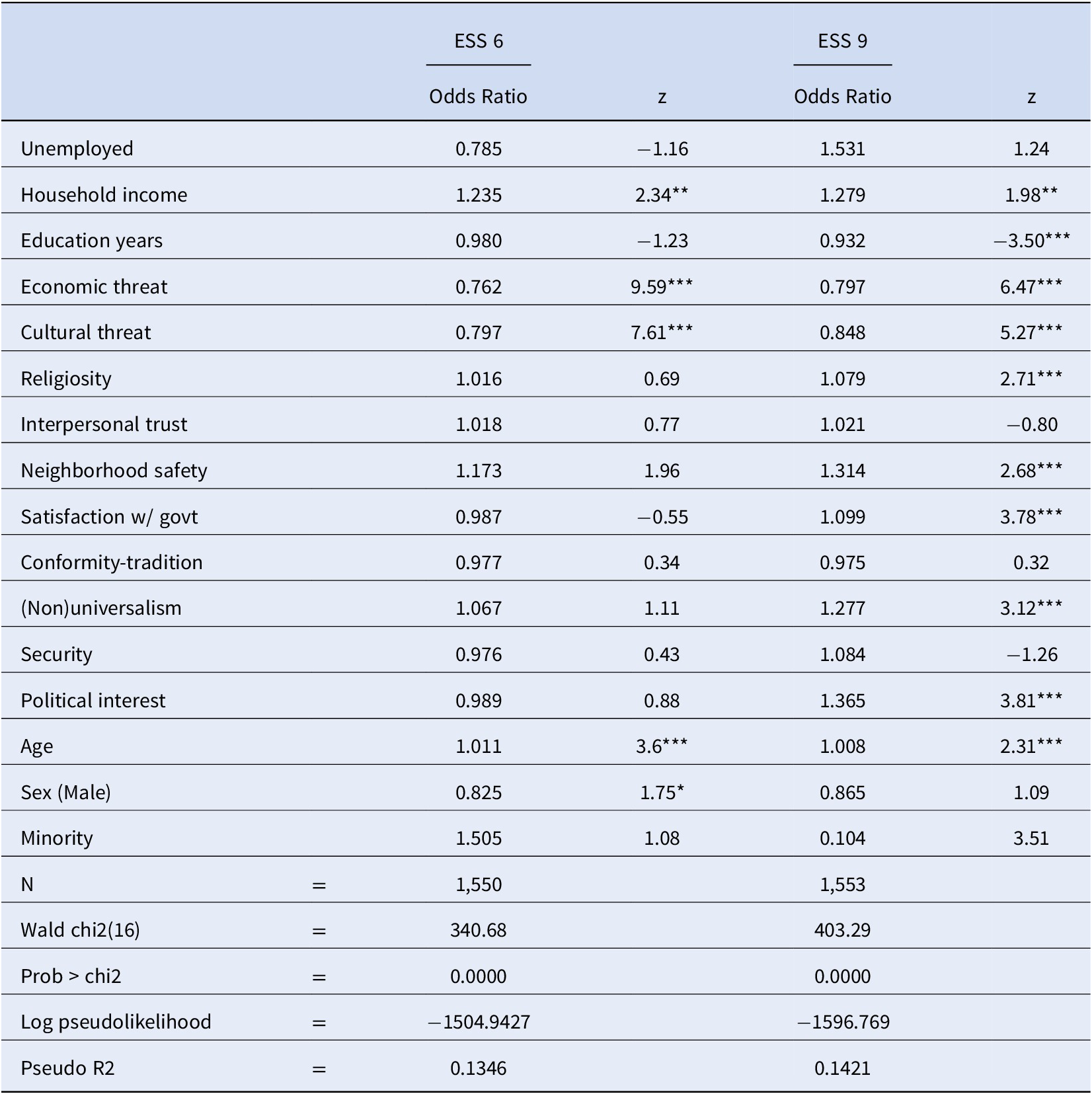

Tables 3 and 4 show the results of the ordered logistic regression analysis that examines the relationship between views on immigration and a set of explanatory variables. The first table presents the results of observations taken at two different points in time, concerning attitudes toward foreigners of the same ethnicity as the local Polish inhabitants. The second table displays the findings concerning attitudes toward people of a different race or ethnicity than the majority of people in Poland.

Table 3. Ordered Logistic Regression – Attitudes to Immigrants of the Same Ethnicity

Data source: ESS Round 6 & ESS Round 9, Poland

*** P|z| < 0.01, ** p|z| < 0.05, *p|z| < 0.1

Table 4. Ordered Logistic Regression – Attitudes to Immigrants of a Different Ethnicity

Data source: ESS Round 6 & ESS Round 9, Poland

*** P|z| < 0.01, ** p|z| < 0.05, *p|z| < 0.1

Overtime Comparison – What Has Changed after 2015?

We can see that as Poles took a stronger anti-immigration approach over time, some of the explanatory factors, such as religiosity and disagreement with the value of universalism, became much more important. Also, satisfaction with the government shows a positive correlation in the Round 9 dataset, while in Round 6 there was no relationship whatsoever. Moreover, after standardization of the coefficients, this variable is even the most important predictor in the newer dataset (if we exclude economic and cultural threat which directly address the issue of immigration). But what exactly does it tell us?

There are studies (e.g. Macdonald Reference Macdonald2021) concluding that individuals who show high support for the government, regardless of their political affiliation, are less likely to oppose immigration, when compared to their politically mistrustful counterparts. As it is the government that is responsible for immigration policy management, they suggest that people that distrust their government are also less likely to trust its ability to manage this policy effectively. However, Ildikó Barna and Júlia Koltai (Reference Barna and Koltai2019) in their research focusing on a Hungarian case have observed quite the opposite and that should help us with understanding the Polish case, too. They learned that regardless of any other motives, individuals asserting greater support for the Fidesz government display generally stronger animosity toward immigrants. In this case, citizens may not necessarily be aware of any specific consequences that immigration would bring; it is sufficient for them to hear from the government they trust that immigration is generally bad and they should fear foreigners in their country. Here it is important to note that the Hungarian government led by the Fidesz party, like the Polish government dominated by the Law and Justice party, has advocated for a strict immigration policy, and during the period that data used in the Barna and Koltai’s study was being collected, it ran an extensive campaign against refugees and other foreigners. Macdonald, on the other hand, in his study of the US, used data that was published in 2016, before Donald Trump (well known for his restrictionism) took office. We can assume that the dynamic of the relationship between trust in a government and attitude to immigration depends on a government’s composition and the policies it advocates, and we should observe this aspect in our data, too.

While it is difficult to draw any clear conclusions from our observations, we conjecture that the general change in public discourse that came with the Law and Justice government could have caused shifts in certain beliefs as the party’s officials have strived to stress the importance of Roman Catholicism and its values in human lives and to promote essentially non-universalist policies aimed at women’s rights, the LGBTQI+ community, and the Middle Eastern refugees. Trust in the government thus also became associated with opposition to immigration as those who were more positive about the government were naturally more responsive to its anti-immigration statements.

Does Ethnicity Matter?

When focusing on the ethnicity of immigrants, it is clear only from the frequency tables (Table 1 and Table 2) that Poles are generally much more welcoming toward other Europeans and have a stronger antipathy to non-European foreigners – as was predicted by the social identity theory. Nevertheless, the general pattern regarding those factors that have any impact on immigration attitudes and those that do not, is very similar in both models. The only interesting difference we observe, after standardizing the coefficients and looking at the values independently of the model, is that the ethnicity of immigrants does indeed matter not only in the salience of the expressed hostility, i.e. that ethnically dissimilar foreigners are less welcome than their counterparts of European origin but also in the importance given to individual factors. While recent literature mainly concludes that the most influential factor in predicting opposition to immigration is the personal belief that foreigners would undermine the cultural life of the host country, in Polish samples this only proves to be true when people consider immigrants of different ethnicity. Considering immigrants of the same ethnicity, however, pushes economic concerns into first place. When looking at ESS data from other countries, we observe a similar pattern in two other Eastern European countries – Czechia and Estonia. However, it is not the case for all countries in this region. In Bulgaria and Slovakia economic concerns raised by immigration dominate over cultural fears, even when reflecting on immigrants of different ethnicity, and Lithuania and Latvia place the cultural threat posed by immigrants in the first place, regardless of the foreigners’ origins.

Not only is the economic threat more important in Poland than the cultural threat, in contrast to most Western countries,Footnote 5 but also the economic self-interest hypothesis seems plausible when it concerns ethnically similar immigrants. For Poles, this mostly means Eastern European economic migrants from Ukraine, Belarus, etc. While unemployment Footnote 6 does not show any significant correlation, dissatisfaction with household income tells a different story. Also, the level of education, as another self-interest theory indicator, proved to be significantly influential in both models. However, a lower level of education does not always only relate to the fear of job competition or concerns about the costs to the welfare system. In the literature, there are two alternative interpretations for this phenomenon. The first suggests that a formal education cultivates in people a more tolerant approach to different cultures and ethnic minorities. Therefore, people who receive a better education are generally more supportive of immigration, and vice versa (Citrin et al Reference Citrin, Green, Muste and Wong1997; Hainmueller and Hiscox Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2010). Another possible explanation, as Danckert, Dinensen, and Sonderskov (Reference Danckert, Dinesen and Sonderskov2017) argue, and one which does not necessarily clash with the first perspective, but rather broadens it, relates to one of our control variables – political interest. They suggest that a certain level of political sophistication may correlate negatively with respondents’ attitudes against immigration. In other words, politically sophisticated people form their opinions on immigration via a range of diverse information sources, and this helps them evaluate issues such as immigration more logically and objectively. This, therefore, moderates excessive anxiety caused by misinformation spread by certain media and politicians.

The social identity theory, which refers to threats to a group (nation), presents another explanation for the antipathy of Poles toward immigrants, regardless of their ethnicity. As with the cultural threat hypothesis, the respondents’ negative perspective concerning the impact of immigrants on their culture increases the odds of them being against immigration. Also, in ESS Round 9 the data from the more religious Polish respondents showed that they tended to be against an influx of foreigners to Poland, which is the exact opposite of what German data from the same year displayed. This disproves the religious compassion hypothesis in the case of Poles and, in contrast to other research, this animosity also applies when they consider immigrants of the same ethnicity. According to the findings of Bloom, Arikan, and Courtemanche (Reference Bloom, Arikan and Courtemanche2015), dissimilarities in religious affiliation may play an even greater role in the rejection of immigrants than dissimilarities in ethnicity. It was not possible to tackle this question in this research as the ESS survey does not refer to the immigrants’ religion when asking respondents about their opinions on the issue of immigration. However, as mentioned above, the largest foreign minority in Poland is Ukrainian, and they are traditionally associated with the Christian Orthodox faith, whereas Poles are predominantly Roman Catholic. We assume that this fact plays a role in explaining this phenomenon which likely deserves further research.

The role of basic human values, not including universalism, as noted above, did not prove significant in the case of Poles. Also, concerning the interpersonal trust hypothesis, unlike previous studies from other European countries or results from countries that participated in ESS Round 9 (e.g. Germany, Denmark, Spain, Slovakia), the data on Poland do not display any significant link between social trust and opinions on immigration. On the other hand, the models do show comparable results, in terms of age and gender, to other similar studies. Males and older respondents tend to have more restrictionist views on immigration.

Conclusion

This article discussed the immigration preferences of Polish citizens. It tackled various questions such as: is hostility to newcomers driven more by cultural or economic concerns? What role (if any) does the ethnicity of immigrants plays in this rejection? What other factors contribute to the animosity? What differences can we observe before and after the critical year 2015? And last but not least: How does the Polish reality differ from previous research in other countries?

The descriptive analysis showed that willingness to accept foreigners to Poland has decreased over time, and in 2018 it was, at best, lukewarm. It also pointed out that the majority of Poles were at the time of the survey against a massive influx of immigrants, especially those of different ethnic or racial origins as is predicted by social identity theory. A similar pattern is observed in other Eastern European countries, however, the political reality, as well as the reasoning behind the restrictive attitudes of the citizens, are among the ESS countries unique to Poland. The ordered logistic regression analysis conducted on a representative sample of the Polish population demonstrates that economic and cultural concerns are equally important. Specifically, it seems that when considering the acceptance of immigrants of the same ethnicity, Poles are most concerned that the immigrants will be a burden on thenational economy, whereas worry about the preservation of national culture is the most influential factor against foreigners of a different ethnic background. This finding goes against previous research as well as current ESS data in Western countries that perceive cultural concerns to be the most important. This could be caused by the comparatively lower economic performance of Poland and the sudden unprecedented increase in economic immigration after 2015. Besides an evaluation of the dichotomy of the economic versus cultural threat, the analyses show that low education and dissatisfaction with household income (potential predictors of self-interest theory), higher age, and being male are other significant predictors of restrictive immigration attitudes in Poland. Additionally, after 2015, stronger religiosity, support for the government, disagreement with universalism values, and a weak interest in politics also show significant correlations with anti-immigration attitudes. These findings are especially important as it seems that it was the politicization of this issue by the Polish government which had a major impact on public opinion and actually caused the citizens’ attitudes became more restrictive over time. Moreover, public reactions to the most recent development in Poland’s immigration situation (i.e. the Middle Eastern and African immigrants trying to enter Poland from Belarus after the Belarusian president Alexander Lukashenko promised them safe passage to Europe, and the Ukrainians fleeing their country after Russian military invasion in February 2022) prove that individual beliefs strongly correspond with the perceived closeness to immigrants and with the political discourse. While (as of May 3, 2022) more than 3 million Ukrainian refugees crossed the Polish border (data2.unhcr.org, May 3, 2022) and received a warm welcome from both the government and the citizens (see Zbieg Reference Zbieg2022 on public opinion about Ukrainian refugees in Poland), the strict measures along the border with Belarus are kept in force and citizens show much less sympathy with those who are stuck at the border (for public opinion on the crisis on the Belarus border see CBOS.pl, December, 2021).

Although the proposed analyses have only limited explanatory power as anti-immigration attitudes are dependent on a great variety of factors that cannot be covered solely by standardized survey questions, this article’s findings may lay the foundations for further qualitative research that would help us better understand the motives behind these attitudes.

Disclosures

None.

Financial Support

This contribution was made with the support of the Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sports of the Czech Republic through project IGA_FF_2020_09 of the Palacký University Olomouc.

Appendix 1: Variables Used in the Models

Source: European Social Survey