1. INTRODUCTION

The call of gavia immer, the common loon,Footnote 1 the bird depicted on Canada’s one-dollar coin known colloquially as the ‘loonie’, is iconic amongst the nation’s nature sounds. The first popular album to capture hearts with the loon’s haunting cry was Bill Gunn’s 1955 A Day in Algonquin Park (Figure 1). In the 1950s, the idea of bringing wildlife sounds into the home for enjoyment and relaxation was novel, but Gunn’s LP also was original as a nature study that could be enjoyed as a piece of music. The album sleeve explains, ‘In this 30-minute presentation, we have woven together some of the sounds of nature that you may expect to hear in Algonquin Park in June or July.’ Side One is ‘Morning and Afternoon’, while Side Two is ‘Evening’; in weaving his selected sounds together, Gunn’s use of the ‘day in the life’ structure – which we have dubbed the circadian audio portrait, in reference to representations of processes which unfold over a full day – required him to make choices about what was most sonically representative of Canada’s oldest provincial park: to compose.

Figure 1 LP jacket front, A Day in Algonquin Park (2nd edn). Image permission: Ontario Nature.

While exploring Gunn’s compositional decisions and the political and creative contexts which surrounded them, we acknowledge the ways in which the album’s creation and reception play out some deeply ironic and paradoxical aspects of the wilderness myth, while inevitably feeding into the construction of a popular and idealised Canadian identity. Algonquin Park, currently part of the Indigenous Algonquin Land Claim,Footnote 2 was hardly pristine nature: Gunn’s ‘nature sounds’ were recorded within an anthropogenic, working and contested landscape. In his making of Algonquin Park there are significant and intentional erasures and omissions but also a modernist ecological sensibility struggling to articulate a place for human visitors within nature. In this, Gunn’s outlook and concerns were not so different from some contemporary soundscape composers. We argue that Gunn’s compositional use of the circadian audio portrait format marks him as a soundscape composer working well before the invention of the genre, alongside composers highly regarded for their early contributions to the recognised canon.

Despite his significant national and international influence on the aural appreciation of nature, Dr William W. H. ‘Bill’ Gunn has been a relatively unsung hero. This is in sharp contrast to the careers of his more visually oriented colleagues, the famous artist-naturalists Roger Tory Peterson and Robert Bateman, whom Gunn predeceased in 1984 at the age of 71. Our very culture and language tends to betray strong bias towards the knowledges and arts of the visible, providing some context to the dearth of studies on sound recordists of nature. British naturalist Jeffrey Boswall, long time BBC broadcaster and co-founder of the British Library of Wildlife Sounds (now at the British Library Sound Archive in London), considered Gunn to be one of the major figures of ‘bird voice’ recording in North America (Boswall and Couzens Reference Boswall and Couzens1982: 925). Renowned in the international recording community and populariser of high-quality field recordings, Gunn also created the wildlife soundtracks for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s (CBC’s) leading documentary series The Nature of Things, ‘one of the first mainstream programs to present scientific evidence on a number of environmental issues’ (MacDowell Reference MacDowell2012: 248). For the program, Gunn recorded sounds across Canada as well as locations in the Galapagos Islands, East Africa, Sri Lanka and Costa Rica.

In 1951, Gunn became director of the Wildlife Research Station (WRS) at Algonquin Park, where he had worked for several summers training younger students including Robert Bateman, later to become well-known as a wildlife artist (see Figures 2 and 3). In 1952 he left the WRS to take on the challenge of becoming the first executive director of the fledgling Federation of Ontario Naturalists (FON), an umbrella organisation for amateur and professional clubs dedicated to the ‘wise use’ of natural areas. Gunn, who disliked taking a salary from the non-profit, came up with the idea to make a record of bird songs to raise funds for the federation. In addition to his founding roles in several nature conservation organisations, Gunn also was one of Canada’s first and most respected environmental consultants, co-founding in 1970 the still active LGL Limited Environmental Research Associates.Footnote 3 Gunn’s research was actively applied to public education, management and industry, including the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry (1974–77) and the design of Toronto’s CN Tower.

Figure 2 At the Algonquin Park Wildlife Research Station, 1950. L to R: Murray Fallis (Department of Parasitology, Ontario Research Foundation), Bill Gunn, Dave Fowle (second director of the WRS, future founder of York University). Photo courtesy Algonquin Park Museum Collection.

Figure 3 Robert Bateman and Bill Gunn at the Algonquin Park Wildlife Research Station, 1946. Photo courtesy: Algonquin Park Museum Collection.

As director of the FON he also led efforts to educate the public on aspects of nature study: his 1955 book for children Playground Activities: Nature Study (Gunn Reference Gunn1955a), encourages children to ‘listen with all their might’ in an activity called ‘Nature Music’.Footnote 4 CBC proudly asserted that Gunn had amassed ‘one of the largest libraries of bird, insect and mammal sounds in the world’ (Sounds of April 1969), a project he formally began in 1955 though his earliest recordings date to 1950. The Gunn Library of Wildlife and Environmental Sounds, held in the British Library Sound Archive and purchased by the Macaulay Library (ML) at the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology after his death, contains many of the ML’s ‘gold standard’ (Budney Reference Budney2015) field recordings. This article considers Gunn’s place in the history of electroacoustic music with a focus on some of his earliest sonic creativity. With an ear to his recording, editing and cataloguing practice, we contextualise his first field recordings, his initial foray into composition with the 1955 release of his best-selling LP A Day in Algonquin Park (from his Sounds of Nature series; Figure 4) and the album’s revision in 1959.

Figure 4 Anne Gunn shipping Sounds of Nature LP orders from the Gunn basement at Glenview Avenue, Toronto, c.1960. Photo detail from the feature ‘Songs and Sounds of the Forest’, Toronto Star Weekend Magazine vol. 10, no. 38. Photographer unknown.

2. RECORDING PRACTICE

Gunn’s recording practice seems to have been less ‘purist’ than recordists such as Ludwig Koch who found that ‘landscapes full of noise – the din of a passing goods train or the drone of distant traffic – were unhelpful and unacceptable’ (Lorimer Reference Lorimer2012: 93). Indeed, Gunn chose to include a train on his very first LP of birdsong (Gunn Reference Borror and Gunn1954):

I was out north of Toronto recording in the morning in the summertime, and the goldfinch was singing beautifully … I was busy recording the goldfinch and the commuter train came along and whistled and blew … but the goldfinch never stopped! [laughter] … I thought this was a useless recording, but hearing it later, it amused me so much that we put it on the back end of the record, and it proved to be very popular because children liked the train, and so on. (Gulledge and Horne Reference Gulledge and Horne1984)

Perhaps one might assume then that Gunn saw nature and culture as blended rather than dichotomous, accepting forms of human presence as part of a ‘wild’ nature. Certainly, his library featured sounds other than ‘wildlife’: Gunn recorded cattle, the growl of a domestic dog, shuffling pigs and, predating Schafer’s soundscape research, he has tracks simply called ‘environmental recording’. But his selection of which human sounds to include on Algonquin Park and the other albums in the Sounds of Nature series are very deliberate and the preparation of source recordings which were edited and mixed into Algonquin Park show a care in excluding distracting anthropogenic sounds: for instance, the first sound heard is the song of the white-throated sparrow; examining the source tape as used on the second edition release reveals that a vehicle passed by just after the first sparrow song heard. The sound of the vehicle was excluded from the album, and the only human-produced sound to be deliberately highlighted appears in the middle of Side 2, at which point the album’s liner notes describe ‘a canoe waits invitingly’. As ‘the paddle bites into the water’ the travelling listener is depicted as a quietly embedded but still foreign presence: ‘We have disturbed a great blue heron that had begun an evening of frog-hunting, and it flies across our watery path.’ The canoe, of course, like the loon, has become a symbol of Canada itself. Its presence in Gunn’s narrative is used, as its sentimental power has been used so often, to legitimise a specific vision of a tolerant and nature-loving nation and authenticate a particular way of being in harmony with the landscape (Erikson Reference Erickson2013). Any possibility for a complex ecological story is simplified here to the nationalist refrain.

In the making of his 1930s ‘Afro-Tropical’ pieces, Koch’s recording apparatus was a seven-ton van with a direct-to-disc cutting lathe.Footnote 5 By the time Gunn was travelling Ontario to make his early recordings, his Magnecord PT6 tape machine fitted into the back of a station wagon, and could be powered from two car batteries (Figure 5). Even with this new portability, the machine was still large and heavy and for prolonged recordings it had to be in reasonable proximity to a power source as well as the creatures being recorded. Gunn’s early use of parabolic reflectors, fabricated to his specifications in Toronto based on measurements he had worked out following his introduction to the idea by Paul Kellogg at Cornell in 1951, brought the sounds of distant creatures closer to his microphone. The tube-based electronics of the preamplifier and recorder could not be easily transported far from the roadways of Algonquin Park, thus we find that Gunn’s recording sites were fixed locations such as the park’s Research Station by Lake Sasajewan (where Gunn was director in 1951–52), or other areas accessible by vehicle along Highway 60, the park’s only major roadway. A dump site at Killarney Lodge was the setting for a whip-poor-will recording (a species of bird now declining in its summer range) ‘made under quite extraordinary circumstances – in the presence of three black bears of varying size, and a crowd of about 50 people’ (Kelly Reference Kellyn.d.). Gunn described the challenge of recording the dramatic loon calls at Lake Sasajewan, due to the nature of his tube-circuitry electronics:

The common loon close-ups were among the very first recordings I ever made with my first really good studio-quality tape recorder … The loons put on their noisy displays once or twice in a 24-hour period, but it was difficult to predict just when … I was able to obtain current for my tape recorder from the research station, but the machine took a minute or so to warm up, and I went through a long, frustrating period in which I sometimes just managed to catch part of the end of their display. Finally, I solved the problem by keeping the machine warmed up through the night and by sleeping out of doors alongside it. (Kelly Reference Kellyn.d.)

Figure 5 Gunn with parabolic microphone and Magnecord PT6 reel-to-reel tape recorder in 1953 Studebaker Champion station wagon, location unknown. Image from article ‘Audiotaped Nature Recording Series “Birds of the Forest” Wins International Award’, Audio Record Magazine, vol. 12, no. 1, January–February 1956.

By the early 1950s, Gunn was already experimenting with his ‘playback’ technique of attracting birds with previously recorded calls. It is unclear if the loon calls on Algonquin Park were obtained by this method (and his reminiscence above would indicate they were not) but Anne Merrill’s ‘Wings in the Wind’ column for the Globe and Mail mentions Gunn demonstrating this technique specifically for loon recording to the Toronto Field Naturalists in 1954: ‘No doubt you will hear the Loon when Dr. Gunn brings out his next series of bird voices, which is to be entitled (I think) Songs of Algonquin Park’ (Merrill Reference Merrill1954). Field biologist Bruce Falls (a founder of the Nature Conservancy of Canada) was a young researcher working at the WRS on small mammals when he learned the playback technique from Gunn: he subsequently ‘made a career of it’ (Falls Reference Falls2013: 14, 2015).

Also revealed by delving into the Gunn collection contained within the Macaulay Library at Cornell is the presence on Algonquin Park of a number of sounds recorded well outside the boundary of the park. These were made as far as 400 km away on Manitoulin Island, in the case of the hermit thrush featured on the second edition, a crystal clear recording that Gunn chose to replace an inferior one actually made in the park, featured on the original release. Out of 23 source recordings which have been identified, seven were made outside the park. Also interesting to note is the temporal distribution of the recordings: the album’s soundscape is described in its liner notes only as taking place during ‘June or July’, but the recordings which comprise its mix were made over a four-year period (1951–54), primarily in June and July but with some of its most memorable sounds recorded earlier or later in the year: the loon recording which concludes the album was made on a foggy April night in 1954 and is seamlessly blended with a loon tape from June 1951. The sawyer beetle larva was recorded in August 1953, at the Ontario Forest Ranger School in Dorset, some 50 km from the entrance to Algonquin Park. The furthest-flung recording is that of the yellow-rumped warbler, made on 13 May 1951 at Gore Bay, Manitoulin Island. The editorial choices exercised in these instances reinforce Gunn’s composerly role, increasing skill in recording and editing and, ultimately, the fictional nature of this ‘short story in sound’ (Gunn 1955b), although the presentation of the sounds remains firmly rooted in his expert knowledge of Ontario wildlife and even with repeated listens the piece sustains the illusion of single-take continuity.

One reviewer described his clear image of a fixed-perspective, continuous recording process: ‘As Dr. Gunn sets up his recording machinery a white-throated sparrow is whistling its famous song which typifies the northwoods’ (Halliday Reference Halliday1955). In mid-2016 the authors had the opportunity to play the first side of the album for an experienced listener and soundscape composer who had not previously been acquainted with Gunn’s work: we were interested in what he might hear regarding the album’s making, insofar as clues were audible. On first listening, he accepted the morning/afternoon sequence as a continuous take, possibly with repositioning of the parabolic microphone to achieve the transitions between ‘scenes’, pointing to the care and skill with which Gunn orchestrated the composition.

3. COMPOSITIONAL STRUCTURE IN ALGONQUIN PARK

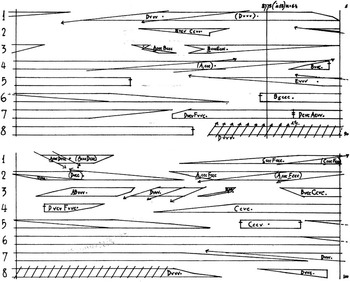

Although Gunn did not work with multitrack recording equipment – and all of the source recordings done with his Magnecord in the early 1950s were monophonic – A Day in Algonquin Park was conceived in two layers, each sometimes to be heard as ‘foreground’ or ‘background’ but usually asserting themselves as of equal importance. Two versions of a score have been found, one assumed to be a draft and one a good copy, and each comprises timelines on graph paper for the two tape layers (labelled as ‘Reel I’ and ‘Reel II’), which together give us the complete, seamless ‘story’. In this article we deal primarily with the version which we understand to be the good copy, referring to the revised second edition of the album; its temporal arrangement fits more or less precisely, in its smallest details, with the album as re-released in 1959. Unfortunately the second page for the ‘day’ side of the album has not been found in its good copy, so the draft has to stand in its stead.

The score is meticulous in detail, drawn as a timeline in black pen with 12 graph paper divisions for each minute (Figure 6). Below the timeline are notations for the beginning and ending of tape segments for the different species of birds and animals. The entries and exits of segments are different for Reels I and II, so together they create a seamless flow. Fade-ins and fade-outs are notated, sometimes with precision: ‘Fade by 13:24/fade in by 13:40’. Along the timeline, for most of the creatures included, the times of each of their calls or songs is graphically notated, with start and sometimes end timing given in seconds, in pencil. In the case of the famous loon sequence that begins about halfway through Side B, the relative amplitudes of the loon calls are graphically notated in pencilled blocks which recall other visual scores of the era such as Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Studie II (1954). The same soundscape composer mentioned earlier responded to Gunn’s timelines by immediately relating them to contemporary methods of organising such sound materials compositionally.

Figure 6 Detail from Gunn's score for A Day in Algonquin Park. This page, labelled ‘Algonquin Park – A.M., Reel 1’ represents minutes one to eight, of one of two tape layers designed to be superimposed for the ‘morning/midday’ side of the album. This page shows recordings focusing on specific bird species, while the corresponding plan for the second tape layer also includes ambient sound beds such as ‘General marsh chorus’ and multiple species recorded broadly in a single take (‘Chickadee, parula, nuthatch’). Score diagram courtesy Gunn Archive.

Below ‘ticks’ on the timeline indicating a specific sound’s occurrence is a number which likely refers to playback volume (Falls Reference Falls2016). This is one of the most interesting features of the score, as it indicates just how constructed this naturalistic soundscape is; although Gunn recorded lengthy continuous sequences, those were edited and reorganised. For instance, the white-throated sparrow sequence which opens the album was apparently sourced from four different cuts, with calls arranged aesthetically, not necessarily in the order they were recorded. Other graphical notations include fade-ins and fade-outs for the different sections, a few marks to indicate undesirable sounds which would need to be edited out or minimised (‘pop’, ‘wind’), and numbers in several places corresponding to EQ frequencies as typically presented on a 1/3-octave graphic EQ processor (125/250/500 Hz). Bruce Falls acted as mix assistant (Falls Reference Falls2015).

It is worth noting Gunn’s bookending of the album with the white-throated sparrow and the loon. The importance of the loon’s call among signifiers of Canadianness cannot be overstated,Footnote 6 and Gunn seems to have played an important role in raising it to that level: his recordings of ‘The calls of the loon … [which] have come to symbolize Canada’s wilderness, because of their lonely, haunting quality’Footnote 7 were also likely used in the original ‘Hinterland Who’s Who’ series of TV spots created between 1963 and 1977, which indoctrinated several generations of children and adults. Gunn wrote about the final, long loon sequence in 1957, in a report to the Federation of Ontario Naturalists on progress with the Sounds of Nature LP series: ‘we seem to have captured something that is close to the hearts of a lot of people’.Footnote 8 Certainly most of the album’s reviewers single out the loon segment as the most memorable part of the LP, while Side 1 opens with the white-throated sparrow song which is often rendered in words as ‘Sweet sweet Canada Canada Canada’ or ‘Oh pure Canada Canada Canada’. Gunn would not have been unaware of this rendering: as early as the 1930s the white-throated sparrow was considered a ‘national symbol’ for its song by James Baillie, who in his popular newspaper column ‘Bird Lore’ wrote ‘“Sweet, sweet Canada, Canada, Canada”… He utters it because he rejoices in having again reached his home, the place in which he was born’ (Greer and Cameron Reference Greer and Cameron2006: 42). The choices for opening and concluding segments thus seem to be quite deliberate brackets or quotation marks establishing the arch-Canadianness of the scenes which unfold in between. The album itself was quickly considered emblematic of Algonquin Park and Canadianness, to the extent that a souvenir copy was presented to Queen Elizabeth II on her brief visit to the park in 1959.Footnote 9

Gunn’s vision for the album was that it should go beyond being merely a resource for teaching oneself to recognise birdsongs, and to that end the first edition of the record, unlike other notable birdsong albums of the time, contained no narration identifying species. He wrote in 1961 that ‘ it seemed to me that the human voice […] was an intrusion that spoiled the listening pleasure after it had been heard a few times’.Footnote 10 The lack of this instructional element was missed by some listeners, and with the album’s 1959 revision and re-release a concession was made: at the end of each side, a spoken summary of the record’s ‘leading performers’ was provided, in the order of the creatures’ appearances.

4. GUNN AND THE CIRCADIAN AUDIO PORTRAIT

The genre of circadian audio portraits, into which we place A Day in Algonquin Park, can be considered a subcategory of soundscape composition, the features of which have been framed in recent years by composers Barry Truax, Hildegard Westerkamp and others. For them, the action of composing with ‘real-world’ sounds contains echoes of sonic activism rooted in honouring the subtleties of desirable sounds all too easily obliterated by ‘noises’, and foregrounding a recorded sound’s connection with a specific time and place. The title of Gunn’s album appears in quotes on the record jacket: from the start we are thus aware that the soundscapes contained within are constructions, a creative representation of this ‘day’. Gunn freely acknowledged in a 1984 interview with ornithologist Jim Gulledge that ‘it took me awhile to put that one together. People said to me, “did you actually record that all in one day?” And I said, “no, actually, I didn’t”’ (Gulledge and Horne Reference Gulledge and Horne1984). In 2016, Gunn’s ornithologist colleague Randolph Scott Little remembered him as a ‘master of ambience, or “soundscape” recording’ (Little Reference Little2016).

The roots of composing with such environmental sounds are heard in the histories of musique concrète, and the sonic studies of Henry and Schaeffer, who in the 1940s experimented with abstracting, transforming and juxtaposing sounds from everyday life (Reydellet Reference Reydellet1996). The ‘sound objects’ which become compositional material are intentionally divorced from their origins: Schaeffer placed emphasis on the idea of ‘reduced listening’, focusing on the ‘traits of the sound itself, independent of its cause and of its meaning’ (Chion Reference Chion2012). Nearly simultaneously with but quite separately from Schaeffer and Henry’s experiments, the Egyptian composer Halim el-Dabh created what has been described as the earliest example of musique concrète composition in Cairo in 1944, but that piece The Expression of Zaar, a treatment of his recording of a Zaar exorcism ceremony, seems less concerned with abstracting sound and more focused on representation of a time and place. In this, it is philosophically more akin to the framework for soundscape composition which Truax later defined as requiring several elements: recognisability of source recordings, invocation of the listener’s knowledge of the environmental context, shaping of the composition via the composer’s knowledge of that context, and ultimately that ‘The work enhances our understanding of the world and its influence carries over into everyday perceptual habits’ (Truax Reference Truaxn.d.).

Gunn did not claim himself to be a composer, and in 1955 the category of soundscape composition had yet to be defined, but A Day in Algonquin Park fits well within Truax’s terms, and the work which Gunn put into the album is certainly composerly. Gunn’s own early description of the piece was that it was ‘woven together’ (Gunn 1955b) but a later Federation of Ontario Naturalists advertising flyer for the record, c.1960, asks ‘Do you like … SOUND PAINTINGS? TONE POEMS?’, clearly indicating that connections to musical composition – even avant-garde composition – were well understood by Gunn.Footnote 11 The term ‘tone poem’ is of course most often applied to symphonic compositions, ‘usually in a single continuous movement, which illustrates or evokes the content of a poem, short story, novel, painting, landscape, or other (non-musical) source.’Footnote 12

Gunn’s colleague, the French wildlife recordist Jean-Claude Roché, who was artistically inspired to pursue his own creative sound practice after hearing Gunn’s LP, stated emphatically ‘it was music. It was the work of a musician because he has chosen … the best recordings, he has put it in some order, mixing them … making a day, but it is a theoretical day … he has made a kind of a symphony to resemble the day’ (Roché Reference Roché2015). Interestingly, Gunn himself referred to the piece as a ‘Symphony of Nature, from the land of the loon’ in promotional materials. The preparatory graphical timelines Gunn constructed for organising and layering his sounds bear passing resemblance to the timeline diagrams and musical graphics of contemporaneous ‘experimental’ composers such as John Cage, Morton Feldman and Earle Brown (see Figure 7). These composers, like Gunn, were inspired by the newly available technology of tape recording: as Cage commented in 1957, ‘Since so many inches of tape equal so many seconds of time, it has become more and more usual that notation is in space rather than in symbols of quarter, half, and sixteenth notes and so on’ (Cage Reference Cage1961: 11).

Figure 7 Page 6 of John Cage’s 193-page score for the 1951–53 tape composition Williams Mix, showing complex cuts and splices to be made. Image courtesy CF Peters Corp.

The idea of representing place and time through an artificial assemblage of recorded sequences can be found as early as 1937, in Ludwig Koch’s daytime and night-time ‘Afro-Tropical’ soundscapes published in 1938 with the ‘sound-book’ Animal Language (Huxley and Koch Reference Huxley and Koch1938). All source sounds were recorded by Koch at the Whipsnade Wild Animal Park and the London Zoo (Tipp Reference Tipp2011, Reference Tipp2016) and organised into soundscapes of less than four minutes each, on two 78 rpm records. These short pieces are like windows on an imagined African scene, but without any significant sense of change as time passes.

Other examples of constructed naturalistic soundscapes are not easily found before Algonquin Park in 1955: Jim Gulledge identified the album as ‘one of the first panoramic … composed [environmental sound] pieces to evoke a mood’ (Gulledge and Horne Reference Gulledge and Horne1984). The conceit of the form, an easily understood framework on which to drape a naturalistic sonic depiction of a place or a community, has become more popular in the decades since, however. Significant examples which have resonance with Gunn’s work might include: the hour-long 1974 piece Summer Solstice composed for broadcast on CBC Radio’s Ideas programme by the World Soundscape Project led by R. Murray Schafer;Footnote 13 the 1990s CDs Voices of the Rainforest: A Day in the Life of the Kaluli People, and Rainforest Soundwalks: Ambiences of Bosavi, Papua New Guinea, both recorded and edited by ethnomusicologist Steven Feld; Jason Reinier’s 1996 CD Day of Sound, which offered a 74-minute time-organised weaving of soundscape recordings from around the world; Francisco Lopez’s Reference Lopez1998 La Selva, based on recordings made in Costa Rica, offering a ‘prototypical day cycle of the rainy season, starting and ending at night’ (Lopez Reference Lopez1998); and the 2001 Caratinga: Soundscapes from Brazil’s Atlantic Rainforest, by Douglas Quin, which offers ‘a sonic overview of the cycle of day and night in the forest’. Another connection which should be mentioned, and which comes before any of the above examples, is Luc Ferrari’s Presque Rien No. 1 (1967–70), which was created – somewhat scandalously – in the context of the Groupe de Recherches Musicales, Schaeffer’s community of composers emerging from the aesthetics of musique concrète. Ferrari’s 20-minute work presents an apparently continuous document of the early morning of a Yugoslavian village, and he described this work and others which followed under the same title of Presque Rien, or ‘next to nothing’ as ‘more reproductions than productions: electroacoustic nature photographs – a beach landscape in the morning mists, a winter day in the mountaintops.’ Like Algonquin Park, the first in this series was a naturalistic construction, created by editing together segments recorded over many days. Ferrari’s intention in creating the series was to spawn a new genre of personal recordings functioning like holiday snapshots. Eric Drott has commented that Ferrari’s work was intended ‘not to be listened to as much as heard, used to color or to decorate an interior space’, perhaps in the manner of Erik Satie’s musique d’ameublement, so in this it was composed with an entirely different intention from Gunn’s album. Nevertheless an interesting comparison of technique and outcome may be made (Drott Reference Drott2009).

Many other recent examples of works in the circadian audio portrait vein could be cited, both commercial releases and artists’ projects which were published in limited editions or not published at all. Gunn himself did not pursue the genre extensively – perhaps surprising given the relative success of Algonquin Park – but he did publish one more LP in the ‘day of’ format which will require further analysis in a separate article: Sounds of Nature Volume 5: A Day at Flores Moradas. This 1959 release, focusing on a region in Venezuela, was composed by Gunn from 13 hours of recordings made during his visit to the area, along Venezuela’s southern border with Colombia, as environmental consultant to the Creole Petroleum Corporation.

One critique of soundscape recording and composition which has been made by anthropologist Tim Ingold in his article ‘Against Soundscape’ (Ingold Reference Ingold2007) is that it approaches sound as an object, not as an experience. Similarly, Francisco Lopez, in his essay accompanying the aforementioned La Selva, criticises bioacoustic recording that isolates each sound as a separate object, for instrumental purposes. If Gunn treats sounds as objects however, they are as elements to be arranged naturalistically with an expert’s ear, partly in the service of convincing people to actually visit and care for the conservation of the place. While recording with his parabolic reflector, he is focusing on specific sounds, but his intention in weaving the sounds together is to create an immersive experience. His ‘tone poem’ is perhaps analogous to the work of painter Tom Thomson whose Algonquin Park landscapes were constructed to create a mood, providing early inspiration for the Group of Seven. And as with Thomson’s legacy, Gunn’s ‘sound painting’ similarly can be critiqued as representing Algonquin Park as pristine and untouched when in reality the region they both depicted has long been occupied by humans.

5. CONCLUSION

As of 1981, A Day in Algonquin Park had sold well over 35,000 copies and was one of the best-selling birdsong LPs in North America (Boswall and Couzens Reference Boswall and Couzens1982: 927). It currently is out of print. Because of its widespread sales, however, used copies (usually well-worn) may be readily found in thrift stores in Ontario and through eBay and other online sources. The argument for recognising William Gunn as a soundscape composer – though he did not seek to achieve recognition as such – is substantiated by the evidence of the complex work which went into its field recording, its scoring, the technical understanding of studio practice which Gunn exhibited in processing and mixing his recordings, and finally the language he employed in presenting it to the public. In comparison to many contemporaneous composers of musique concrète or other electronic music incorporating real-world sounds, Gunn’s approach was populist and entrepreneurial, and A Day in Algonquin Park reached a relatively vast audience without any burden of first having to convince people that it was ‘music’. His composition was marketed within the framework of birdsong LPs designed to educate as much as entertain – a realm separated by a significant gulf from contemporaneous work in ‘art music’. Nevertheless, his musical handling of environmental sound did not aim to pander to a popular audience, and the album foreshadows approaches and concerns determined decades later by theorists of soundscape composition and acoustic ecology.

As compared to the isolated recording of a single bird representing a species – a practice in which Gunn was certainly expert – the structure of the circadian audio portrait requires the composer to make choices about what is representative: to compose a naturalistic soundscape. That outward openness then makes it interesting to look back in, to try to answer the questions ‘where is nature’, and ‘for whom’? What was natural for Gunn? He undoubtedly understood that the territory of Algonquin Park had been thoroughly altered by human industry and tourism, but his sonic representation of the park is as a place of great, isolated beauty and ‘unspoiled wilderness’ (Gunn Reference Gunn1955b). A Day in Algonquin Park avoids, almost entirely, sounds associated with human activity. Yet, as for many ecologists (Cameron Reference Cameron2013) and soundscape artists who have worked in anthropogenic landscapes, any easy separation of humans from ‘the natural’ is an ongoing challenge, both philosophically and technically. Francisco Lopez, responding to David Dunn’s critique of those who remove human sonic intrusions from natural environments for their ‘false representation of reality … that lures people into the belief that these places still fulfill their romantic expectations’, writes that our perception (in the field) of the sound of rain in a forest or an insect call often actively edits focus and memory, removing the nearby human voices or the sound of distant traffic. ‘Because this perceptional/conciousness level is at the basis of our apprehension of “reality”, I don’t think that a recording that has been “cleaned up’” of human-made sounds (even if this involves more than editing) is more false than another that hasn’t. In many cases, I would even think of the contrary’ (Lopez Reference Lopez1998: 4). Nevertheless, in Gunn’s production of A Day in Algonquin Park we are reminded how ecological and sonic practice can combine – however inadvertently – to reinforce the political erasures of humans and compound the effects of settler colonialism.

The work of environmental sound recordists is now often considered as connected to composerly concerns, and Gunn’s work is indicative of strong early ties. In finding him a place in the history of electroacoustic music, other suggestive reorientations of that past should perhaps follow, not the least of which is the role Gunn likely played in preparing the ears of his audience for soundscape work to follow. Gunn’s work also provides the soundscape/acoustic ecology movement with a richer history of activist, scientific and conservationist concerns, prefiguring acoustic ecologists’ goal to educate a general audience about all things sonic, and echoing Gunn’s imperative to listen with all our might.

Acknowledgements

For generous assistance with this research we would like to thank the Insight program of the Social Sciences and Humanities Council of Canada, the Eccles Centre for American Studies at the British Library, Tim Winegard of the Algonquin Park Wildlife Research Station, Greg Budney of the Macaulay Library of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Cheryl Tipp of the British Library Sound Archive, Barry Truax, Bruce Falls, Randy Little, Lucie Gunn, Jacques Robin, Myrna Clark, Darren Copeland and Nadene Thériault-Copeland.