No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

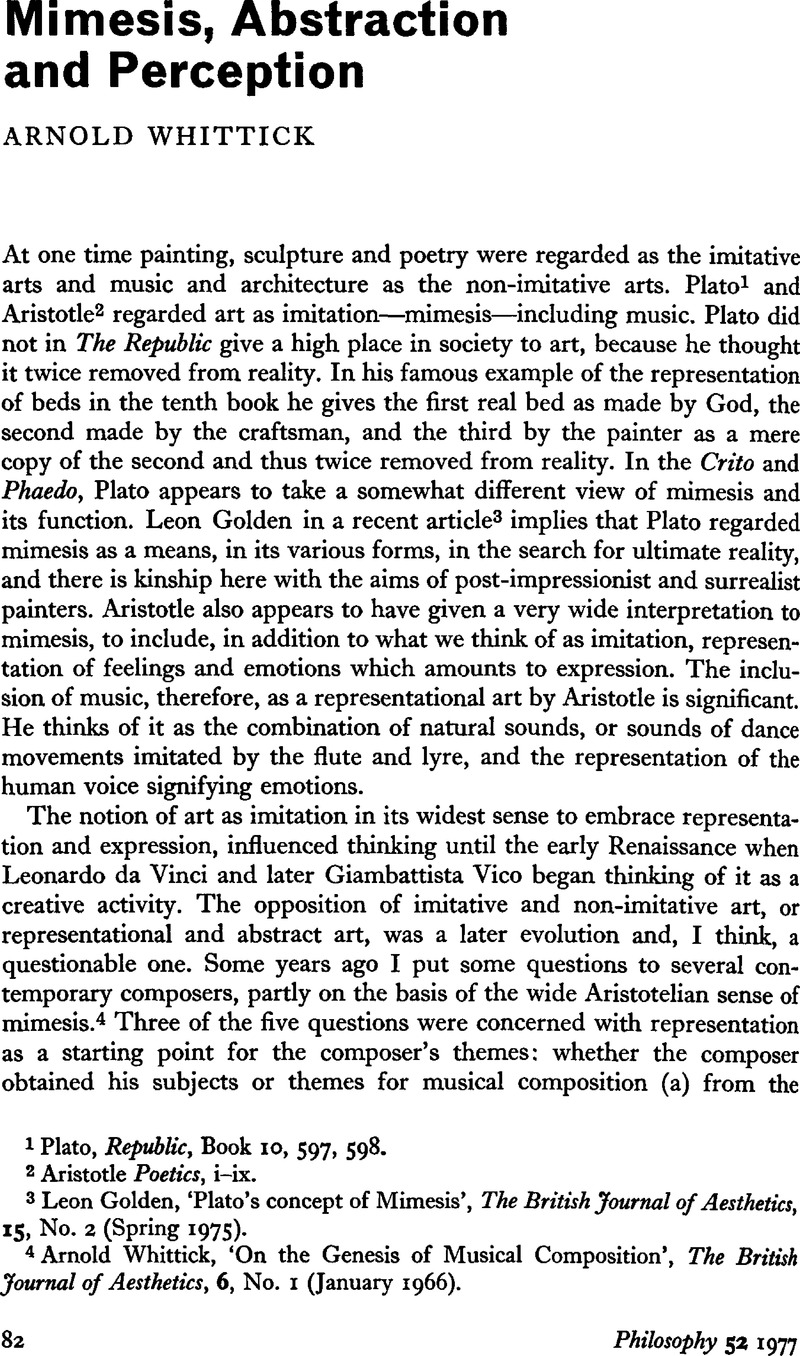

Mimesis, Abstraction and Perception

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 30 January 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Discussion

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Royal Institute of Philosophy 1977

References

1 Plato, , Republic, Book 10, 597, 598.Google Scholar

2 Aristotle, Poetics, i–ix.Google Scholar

3 Golden, Leon, ‘Plato's concept of Mimesis’, The British Journal of Aesthetics, 15, No. 2 (Spring 1975).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

4 Whittick, Arnold, ‘On the Genesis of Musical Composition’, The British Journal of Aesthetics, 6, No. 1 (01 1966).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

5 Worringer, Wilhelm, Abstraktion und Einfühlung (1908) (English translation 1910).Google Scholar

6 Gilson, Etienne, Painting and Reality (London, 1958).Google Scholar

7 Gindertael, R. V., L'Art abstrait: nouvelle situation.Google Scholar

8 Read, Herbert, Art Now, an introduction to the theory of modern painting and sculpture (London, 1933), especially section IV, Abstraction.Google Scholar

9 Read, Herbert, op. cit., 101–103.Google Scholar

10 Whitehead, A. N., Symbolism: Its Meaning and Effect (Cambridge, 1928).Google Scholar

11 The complete passage from which these quotations are abstracted is as follows—‘We look up and see a coloured shape in front of us, and we say,—there is a chair. But what we have seen is the mere coloured shape. Perhaps an artist might not have jumped to the notion of a chair. He might have stopped at the mere contemplation of a beautiful colour and a beautiful shape. But those of us who are not artists are very prone, especially if we are tired, to pass straight from the perception of the coloured shape to the enjoyment of the chair, in some way of use, or of emotion, or of thought. We can easily explain this passage by reference to a train of difficult logical inference whereby, having regard to our previous experiences of various shapes and various colours, we draw the probable conclusion that we are in the presence of a chair. I am very sceptical as to the high-grade character of the mentality required to get from the coloured shape to the chair. One reason for this scepticism is that my friend the artist, who kept himself to the contemplation of colour, shape and position, was a very highly trained man, and had acquired this facility of ignoring the chair at the cost of great labour. We do not require elaborate training merely in order to refrain from embarking upon intricate trains of inference.’

12 SirRead, Herbert quotes the passage in note 6 in his book The Forms of Things Unknown (London, 1960), 78Google Scholar. With regard to Whitehead's distinction of high- and low-grade organisms Read says that he is ‘not quite sure whether Whitehead is here making a distinction between different types of human beings, or between human beings and animals’. But Whitehead's example of Aesop's dog, and other references in his book, make it clear, I think, that high-grade organisms means human beings and most of the higher animals at least. The mention of ‘purely physical organisms’ not experiencing presentational immediacy would support this.

13 Hutcheson, Francis, An Enquiry into the Original of our Ideas of Beauty and Virtue (1725).Google Scholar

14 Kames, Lord, Elements in Criticism (1762).Google Scholar

15 Kant, Immanuel, Critique of Judgement (1790), J. H. Bernard's translation (1.16).Google Scholar

16 Read, Herbert in Art and Society (London, 1937)Google Scholar adduces some evidence for an instinctive basis for the aesthetic impulse.