Introduction

Between 1946 and 2021, 104 female presidents or prime ministers were elected or appointed in 69 countries. As of May 2022, 30 women were incumbent national executive leaders (Vogelstein and Bro Reference Vogelstein and Bro2022). As the number of female leaders has increased, scholarly attention to them has also grown. Recent studies have focused mainly on the positions that women tend to assume (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2013), the conditions enabling them to reach those positions (Beckwith Reference Beckwith2015; Genovese and Steckenrider Reference Genovese and Steckenrider2013; Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2013), and the policies they promote and implement (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2019; Reyes-Housholder Reference Reyes-Housholder2016; Reyes-Housholder and Schwindt-Bayer Reference Reyes-Housholder, Schwindt-Bayer, Martin and Borrelli2016). These leaders improve people’s perceptions of women as competent leaders (Alexander Reference Alexander2012; Alexander and Coffe Reference Alexander, Coffe, Alexander, Bolzendahl and Jalalzai2018; Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2016), as recent global attention to female leaders’ performance during the COVID-19 pandemic has shown (Johnson and Williams Reference Johnson and Williams2020; but see Piscopo Reference Piscopo2020).

When a woman holds the highest political office of a country, she challenges the perception that such an office is not for women. As an increasing number of women become prime ministers and presidents, some of them leave office amid controversy and instability, such as Yingluck Shinawatra, Aung San Suu Kyi, Theresa May, and Dilma Rousseff. When a female leader ends her career in a controversial fashion, how does that affect voters’ perceptions of women as effective political leaders? Existing studies of symbolic representation do not explicitly consider the fact that many women leaders are part of the social, economic, and political elite. Female prime ministers and presidents, like men, tend to have higher educational levels, are more likely to have postgraduate degrees from abroad, and are wealthier than the general public, especially compared to other women in that society (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2013). When female leaders are privileged elites even before assuming their office, does their election still elicit a high level of symbolic representation among the public?

To answer these questions about disgraceful exits, privilege, and symbolic representation, I analyze how Park Geun-hye’s election as the first female president of South Korea (2012) and her subsequent impeachment and conviction (2016–17) shaped voters’ perceptions of women’s potential and contribution as political leaders. Park was the daughter of the late dictator Park Chung-hee, and her electoral victory was heavily indebted to her father. She was often criticized for not understanding ordinary citizens’ lives because of her privileged family background. The most recent wave of the World Values Survey (WVS), published in 2020 (Haerpfer et al. Reference Haerpfer2022), shows that South Korea is one of a few countries in which trust in women as political leaders decreased after a female president or prime minister served. This pattern stands in contrast with the global trend of increased openness to the idea of women as political leaders, even in countries where women leaders have exited their office amid controversy, such as Brazil, Argentina, and the United Kingdom (see Appendix 1 in the Supplementary Materials online).

Analyzing an original online survey of 1,197 South Koreans and six focus groups with 35 South Korean citizens, I demonstrate that South Korean voters overall did not recognize Park’s election as the first female president of the country as a symbol of women’s political empowerment. The survey data show that conservative voters tended to acknowledge Park as a “historic first,” believed that she promoted women-friendly policies, and gave her credit for shattering the glass ceiling more often than did other groups in the electorate. On the other hand, women voters expressed strong disappointment and concerns about the failure of this historic first, as they linked Park’s failure to the diminishment of other female leaders’ electoral prospects. The focus groups revealed that voters perceived that Park’s election had more to do with her family ties than it did with her womanhood, and thus they were reluctant to consider her election a breakthrough for gender equality in the country. Her parental and marital status (a single woman with no children) cast doubt, especially among married women with children, that she would understand “women’s interests.” Almost all focus group participants expressed pessimism about the future of women in politics after Park’s impeachment. The conservative participants tended to attribute this expectation to a lack of qualified women, whereas the liberal participants commented that Park’s impeachment revealed prevailing and persistent sexism in South Korean society. By waiting three years after the impeachment to run the survey and focus groups, this study obtains valuable insight into how voters remember and evaluate Park’s political legacy after the initial shock of the impeachment subsided.

This article contributes to the study of gender and symbolic representation in two significant ways. First, it empirically tests the supposed connection between the failure of the historic first in office and people’s belief in women’s ability as political leaders. As an increasing number of women are elected, and some of them leave office amid controversy, examining the potential lasting impact of such exits expands the theoretical understanding of symbolic representation. Second, findings from this study underscore the importance of considering intersectionality in studying women leaders. Considering other aspects of leaders’ identities beyond their gender adds nuance to the link between descriptive and symbolic representation (Davidson-Schmich Reference Davidson-Schmich2011). As an unmarried woman with no children coming from a political dynasty, Park showed how a different combination of family, class, gender, marital, and parental backgrounds enabled or prohibited voters from identifying with her as a leader.

After reviewing the literature on descriptive and symbolic representation and the continuing importance of political dynasties regarding elections, I introduce the context of Park’s election and impeachment to justify why South Korea is a suitable case to analyze the nuanced connection between descriptive and symbolic representation through an intersectional lens. An explanation follows of the research design for the surveys and focus groups. After discussing the findings from the empirical data, I elaborate on their implications and the possible directions for future research.

Effect of Descriptive Representation on Symbolic Representation

Symbolic representation is related to constituents’ perceptions that they are represented (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967). Krook (Reference Krook2010) examined two aspects of women’s symbolic representation: how women’s presence in politics promotes the legitimacy of the legislature as a whole and how much this presence impacts voters’ perceptions of politics as a men’s world (Krook Reference Krook2010, 236). Regarding the first aspect, improvement in women’s descriptive representation leads to a higher level of satisfaction with democracy, legislature, and government as a whole (Alexander and Jalalzai Reference Alexander, Jalalzai, Martin and Borrelli2016; Clayton Reference Clayton2015; Lombardo and Meier Reference Lombardo and Meier2014; Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt-Bayer2010) and lowers perceived levels of government corruption (Esarey and Schwindt-Bayer Reference Esarey and Schwindt-Bayer2018; Watson and Moreland Reference Watson and Moreland2014).

Regarding the second aspect, female presidents and prime ministers shape positive attitudes about women as political leaders and challenge the notion that the offices of president or prime minister are men’s domains (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai, Alexander, Bolzendahl and Jalalzai2018; but see Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2016), even when women run for election unsuccessfully (Simien Reference Simien2016). Mediating factors such as gender and party affiliation affect who feels symbolic representation and how strongly from descriptive representation (Verge and Pastor Reference Verge and Pastor2018). The presence of women in politics increases women’s likelihood of discussing politics, contacting officials, participating in protests, and running for office (Barnes and Burchard Reference Barnes and Burchard2013; Dittmar, Sanbonmatsu, and Carroll Reference Dittmar, Sanbonmatsu and Carroll2018; Reyes-Housholder and Schwindt-Bayer Reference Reyes-Housholder, Schwindt-Bayer, Martin and Borrelli2016). Women leaders become positive role models for women and girls (Beaman et al. Reference Beaman, Duflo, Pande and Topalova2012; Campbell and Wolbrecht Reference Campbell and Wolbrecht2006; Liu and Banaszak Reference Liu and Banaszak2017), and a female president empowers female parliamentarians (Wahman, Frantzeskakis, and Yildirim Reference Wahman, Frantzeskakis and Yildirim2021), although such a role-model effect tends to decrease over time (Beauregard Reference Beauregard2018; Gilardi Reference Gilardi2015). Moreover, copartisans are more responsive to the presence of a female leader. Dilma Rousseff’s election empowered all women, for example, but especially those who identified with left-leaning/feminist views (dos Santos and Jalalzai Reference dos Santos and Jalalzai2021). Symbolic representation can transcend national boundaries. Angela Merkel’s election elicited excitement about and expectations for women’s electoral victories in other countries (Ferree Reference Ferree2006), and Kamala Harris’s election as the first female vice president of the United States, and the first woman of color, evoked feelings of (cautious) hope outside the United States (Abdellatif et al. Reference Abdellatif2021).

Some studies have found a negative correlation between descriptive and symbolic representation (Espírito-Santo and Verge Reference Espírito-Santo and Verge2017; Stauffer Reference Stauffer2021). Sometimes women’s entry into politics even leads to a negative impact on constituents’ views on women in politics (Clayton Reference Clayton2015), decreases the level of women’s political engagement (Liu Reference Liu2018), and undermines women’s appeal as alternative candidates to the frustrating status quo (Morgan and Buice Reference Morgan and Buice2013). Even though the share of women legislators has increased over time and they have actively promoted women-friendly bills (Lee Reference Lee, Franceschet, Krook and Tan2019b), South Korean women’s political participation is not as active as that of men except in voting participation, as in other Asian countries (Liu Reference Liu2022). In addition, not all female leaders stand up for women, such as Margaret Thatcher (Gottlieb and Campbell Reference Gottlieb and Campbell2019).

These mixed findings on the connections between descriptive and symbolic representation are attributable to two main factors. First, some voters do not have an accurate understanding of the level of women’s parliamentary representation; thus, studies based on legislatures can result in inconsistent findings (Stauffer Reference Stauffer2021). Second, utilizing observational public opinion polls before and after a female president’s term cannot isolate the effects of women’s representation in other institutions, such as in parliaments or in local politics (Espírito-Santo and Verge Reference Espírito-Santo and Verge2017). A survey experiment might remedy these limitations (Espírito-Santo and Verge Reference Espírito-Santo and Verge2017), but the presence of a recently impeached woman president would render it impossible to suppress the memory of the event even in an experimental setting. In contrast, this study asked the participants to directly connect Park Geun-hye’s presidential legacy to symbolic representation in light of her impeachment. Based on the literature, I test the following two hypotheses about Park Geun-hye, the first female president of South Korea and a conservative.

Gender affinity hypothesis: Female voters evaluate the symbolic nature of Park’s status as the first female president more favorably than do male voters.

Ideological affinity hypothesis: Conservative voters evaluate the symbolic nature of Park’s status as the first female president more favorably than do liberal voters.

Family Ties, Dynastic Politics, and the Question of “Which Women”?

Many women leaders are part of the social, economic, and political elite. Among all the women who became presidents or prime ministers between 1960 and 2019, 17 (27%) were wives, daughters, or sisters of male political leaders who held high office (Paxton, Hughes, and Barnes Reference Paxton, Hughes and Barnes2021, 61–63), even though the importance of family ties to women’s elections has decreased in Asia (Inguanzo Reference Inguanzo2020). Dynastic politicians, who are from “any family that has supplied two or more members to the national-level political office” (Smith Reference Smith2018, 4), exist in various types of modern democracies. Both men and women benefit from family ties, even though the share of women tapping into family ties is higher than men’s share (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2013). Seemingly at odds with the norms of the democratic idea of fairness, examples of dynastic politicians abound, including George W. Bush, Justin Trudeau, David Cameron, and Marine Le Pen (Smith Reference Smith2018, 3). Between 1995 and 2016, the percentage of members of parliament (MPs) from political dynasties in 24 democracies ranged between 5% and 10%, and legacy MPs in Japan represented more than 25% of all representatives (Smith Reference Smith2018). Those who hail from political families have electoral advantages derived from their “brand name advantages,” such as name recognition, broader press coverage, inherited political networks, political socialization, and public trust (Clubok, Wilensk, and Berghorn Reference Clubok, Wilensk and Berghorn1969; Feinstein Reference Feinstein2010; Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2013). They inherit “moral capital” and become proxies for deceased or persecuted male predecessors (Derichs, Fleschenberg, and Hüstebeck Reference Derichs, Fleschenberg and Hüstebeck2006; Kane Reference Kane2001), promising peaceful national integration, social and economic justice, and gender equality (Amirell Reference Amirell2012).

The literature on dynastic politicians addresses the factors that facilitate their entry into politics and the elements of their family ties that lead to electoral success. However, how do dynastic candidates affect voters’ perception of the legitimacy of the polity and feelings of being represented—that is, symbolic representation? Even though an increasing number of female leaders have successfully assumed the highest national executive office, existing political institutions and measures designed to promote better inclusion of women tend to benefit women in majority groups (Hughes Reference Hughes2011). Other aspects of political leaders’ identities—such as class, language, religion, and life experiences—might differ from constituents’ perceptions of what a “typical” member of their own group looks like and experiences (Paxton, Hughes, and Barnes Reference Paxton, Hughes and Barnes2021). Thus, the question remains whether women from dynastic families elicit a sense of symbolic representation among women voters, despite their privileged background. Existing studies do not provide a basis for testing hypotheses, so I analyzed the focus group data inductively to observe whether the participants felt represented despite Park’s dynastic connection and privileged background.

Failure and Symbolic Representation

Existing studies have extensively examined female leaders’ performance, finding that some finish their terms more successfully than others do (Genovese and Steckenrider Reference Genovese and Steckenrider2013; Skard Reference Skard2014). Scandals in the party can open a window of opportunity for women to move up the party leadership ladder and be elected (Beckwith Reference Beckwith2015; Thomas Reference Thomas2018), but many women are mired in corruption allegations themselves during or after their tenure, as in the case of Benazir Bhutto (Chu Reference Chu2007; Crossette Reference Crossette1996), Cristina Fernández de Kirchner (Tegel Reference Tegel2019), and Ellen Johnson Sirleaf (Ford Reference Ford2018). Leaders’ exits and their impact on the polity are much less studied than elections, whether the studies focus on executive leaders (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai, Alexander, Bolzendahl and Jalalzai2018) or party leaders (Gruber et al. Reference Gruber, Cross, Pruysers, Bale, Cross and Pilet2015). Women party leaders serve shorter terms and are more likely than men to be forced to resign (O’Neill, Pruysers, and Stewart Reference O’Neill, Pruysers and Stewart2021), and they are subject to a more demanding set of rules than their male counterparts (O’Brien Reference O’Brien2015). Many women find themselves assuming leadership positions in “glass cliff” situations, in which women become leaders when an organizational situation is precarious (Ryan et al. Reference Ryan, Haslam, Ryan and Haslam2007), although this concept has been critiqued (e.g., Thomas Reference Thomas2018, 399). The start of Theresa May’s term amid the Brexit quagmire as a takeover prime minister is an example of such a situation (Worthy Reference Worthy2016).

Existing studies have examined specific policy disappointments (Barany Reference Barany2019; Villanueva Reference Villanueva1992) and the personal, institutional, and situational factors leading to women leaders’ unsuccessful performance (dos Santos and Jalalzai Reference dos Santos and Jalalzai2021; King Reference King2002; Middleton Reference Middleton2019). Anecdotal evidence suggests that historic firsts feel a heavy burden that they “are not allowed to fail” (Ducharme Reference Ducharme2018; Friedman Reference Friedman2014; Sharpe Reference Sharpe2015). However, there is scarce empirical evidence showing that the public’s perceptions of women in politics after such exits. I hypothesize that those who think Park Geun-hye’s impeachment was related to her gender—meaning, it was a reflection of societal biases against women—worry that her impeachment would be a barrier to other women getting elected as presidents or legislators. As her impeachment represents a reflection of structural biases against women, it would reinforce prejudice against women.

Barrier hypothesis: Those who attribute Park’s impeachment to her gender hold a pessimistic view of other women’s odds of political advancement.

Family Ties, Gender, and the Rise and Fall of Park Geun-Hye

Park Geun-hye of South Korea is an ideal case to examine how female leaders’ gender, dynastic connections, and failures might impact the symbolic representation of women when biases are prevalent against women in politics. Multiple indicators suggest that South Korea is not the most favorable place to be a woman in politics. The World Economic Forum ranked South Korea 102nd of 156 countries on the Global Gender Gap Index (World Economic Forum 2021). Despite almost two decades of adopting gender quotas and mixed electoral systems, the National Assembly still has fewer than 20% women members after its most recent election in 2020 (ranking 121st in the world), below the global average of 26% and the Asian average of 21% (Inter-Parliamentary Union 2021a, 2021b). Political parties are reluctant to nominate female candidates in winnable districts (Lee Reference Lee2019a) and are even willing to forgo government subsidies rather than meet the target for the candidate gender quotas for National Assembly elections (Shin and Kwon Reference Shin and Kwon2022). Voters are skeptical of female candidates’ electoral viability and quicker to abandon a female candidate for another when her poll numbers start to slip compared with when their most preferred candidate is a man (Lee and Rich Reference Lee and Rich2018).

In this context, Park Geun-hye could mitigate the disadvantages of being a woman by leveraging her status as the daughter of Park Chung-hee, the late dictator. The senior Park staged a military coup in 1961 and ruled South Korea until his assassination in 1979. Despite his brutal and oppressive governance, many voters, especially older and conservative voters, remember the senior Park fondly as a driving force behind South Korea’s rapid industrialization during the 1970s. As recently as October 2021, South Koreans rated Park Chung-hee as the best president in the country’s history, according to a Gallup Korea (2021b) poll. Park Geun-hye joined a conservative opposition party’s presidential campaign in 1997. The party tried to use her as an icon to appeal to voters who were nostalgic for her father’s era of rapid economic development. Even though the presidential candidate lost the election under allegations of corruption and nepotism, Park Geun-hye was elected as a national legislator in the 1998 by-election (Lee Reference Lee2017).

After serving five terms as a national legislator and chair of her party, Park Geun-hye was elected in 2012 as the first female president of South Korea. Hailing from a conservative party, Park was popular among older, female, and conservative voters (Kang Reference Kang2013; Kim and Choi Reference Kim and Choi2018; Lee Reference Lee2015; Yoon Reference Yoon2017; Young Reference Young2015). A favorable evaluation of Park’s father was one of the key voting factors in the 2012 presidential elections (Kang Reference Kang2018). For her supporters, Park was a proxy for her father, expected to carry on his legacy. For her opponents, she was the daughter of the dictator who had staged a military coup and committed grave human rights abuses that delayed the country’s democratization.

Park did not show a strong commitment to promoting and empowering women politically. She is from the conservative Saenuri Party, which does not support feminist agendas and consistently nominates fewer women candidates for elections than it pledges prior to each election (Lee and Shin Reference Lee and Shin2016; Lee Reference Lee2019a). Her term as the party chair deepened factionalism, rewarding or punishing party members for their loyalty, with women members often becoming the victims of such turf wars (Lee and Shin Reference Lee and Shin2016, 364). Park did not propose any bills related to women during her legislative terms (Lee and Jalalzai Reference Lee and Jalalzai2017), even though conservative female legislators in Korea were proactively promoting women-friendly bills between 2000 and 2016 (Lee Reference Lee, Franceschet, Krook and Tan2019b). While she highlighted her image as a selfless daughter continuing her father’s political legacy throughout her political career (Shin Reference Shin2018), she emphasized the “first woman” aspect of her presidential candidacy only during the final month of her campaign (Lee Reference Lee2017).

Nevertheless, the data suggest that women voters had positive expectations of Park. According to a public opinion survey conducted by Gallup Korea approximately nine months before the 2012 election, conservative female voters were her strongest supporters, more so than were conservative men. Even among liberal voters, women expressed a higher level of favorability for Park than they did for liberal men (Kim Reference Kim2012). For the first time since democratization, female voter turnout was higher than male turnout (76.4% versus 74.8%) in the 2012 presidential election (Korean National Election Commission 2013). Approximately 52% of women voted for Park and 47% for Moon Jae-in, whereas 48% of men voted for Park and 52% for Moon (Gallup Korea 2013). However, after severe corruption and nepotism scandals broke in July 2016, her presidential approval ratings started to drop dramatically. One week before the National Assembly impeached Park, her presidential approval rating was only 4%. Even 80% of Park’s own party supporters disapproved of her performance (Gallup Korea 2016). By the end of November 2016, more than 130 protests occurred across South Korea, initially demanding her resignation then impeachment; protests were held in 70 cities in 26 countries worldwide (Lim Reference Lim2017). On December 9, 2016, more than half the legislators from her own party voted in favor of her impeachment (National Assembly Minutes 2016). Three months after the impeachment, the Constitutional Court unanimously upheld the legislature’s decision, and Park was sentenced to 22 years in prison. She was granted presidential amnesty in December 2021.

Data and Methods

Survey

I designed and conducted an online survey of eligible voters in South Korea from May 20 to 25, 2020.Footnote 1 The survey questions analyzed here are drawn from a larger project examining South Korean voting patterns in the April 2020 national legislative elections and the impact of COVID-19 on voters’ evaluation of the ruling party and voting decisions. However, only questions relevant to the focus of this article are included in the analysis. Macromill Embrain in South Korea recruited respondents and administered the online survey to 1,279 participants who met the participation age criteria (between 20 and 69). The company maintains a national panel participant database with 1.3 million users, the largest in South Korea. Although there were no attention checks, participants who did not complete the whole survey or whose response pattern raised a quality concern (e.g., marking a 1 for all the questions) were excluded. The analysis included 1,197 responses, which amounts to 16% of the total invitations. The participants were selected from all provinces, except Jeju Island, whose population is less than 1% of the country’s. Quota sampling (age, gender, and regional quotas) was used following the census data provided by the Ministry of Interior and Safety. Embrain provides small numbers of virtual points to the participants, which they can redeem as cash or a gift card at the end of each month. The participants usually earn $20 per month for participating in various surveys (Macromill Embrain Reference Embrain2022).

I employed probability weights based on education, class identification, and political ideology to improve the sample’s representativeness. As of 2020, 51% of South Koreans aged 25–64 had some postsecondary education (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2022), while 81% of the survey respondents reported having postsecondary education. Approximately half the survey participants identified themselves as upper or upper-middle class, compared with only approximately 9% of the population per the census data in 2018 (Statistics Korea 2018). Compared with Gallup Korea’s weekly reports published the same week using a nationally representative sample (Gallup Korea 2020), this study sample is slightly less conservative (11% conservative versus 23% in Gallup) and more moderate (59% moderate versus 30% moderate in Gallup). Appendix 2 in the Supplementary Materials compare the descriptive statistics of the survey participants and the general population.

The study timing should be noted. By 2020, Park’s electoral victory was eight years in the past, and she had already been impeached and sentenced to prison three years earlier. Understandably, it was not possible to separate voters’ assessments of Park from the dramatic way she exited office, and voters’ evaluations of Park might have been different had the survey been conducted before the impeachment. However, this time lapse between the election (2012), impeachment (2016), and survey (2020) provides an advantage for this study, which is about how voters remember and evaluate Park’s political legacy. With the passage of some time since the tumultuous and traumatic national experience, voters have had time to reflect on Park Geun-hye and the impeachment. A recent survey on voter support for Park’s amnesty shows that some voters have indeed changed their position on the impeachment. Even though 81% of voters supported the impeachment a couple of days before the National Assembly vote in 2016 (Gallup Korea 2016), approximately 37% of voters overall supported the amnesty of Park as of January 8, 2021, and 70% of Park’s party supporters wanted to see her release (Gallup Korea 2021a).

To measure symbolic representation, I analyzed the participants’ responses to four items, which constituted the dependent variables for the ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models:

-

1. “Park contributed positively to women’s political representation by being the first female president of the country.”

-

2. “The Park administration implemented many women-friendly policies.”

-

3. “As Park’s election shattered the glass ceiling, her electoral victory would make other women’s election easier than before.”

-

4. “Park’s impeachment would make it difficult for other women to get elected as a legislator or president.”

To test the barrier hypothesis , I included the item “one of the reasons for Park’s impeachment and conviction is the fact she was a woman” to measure one of the key independent variables. The participants indicated their agreement with these five items on a 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). I maintained the same scale when using the responses as variables in the regression models.

Based on the literature, I used the participants’ gender and political ideology as two key independent variables in the regression models. The participants indicated their political ideology on a scale of 1 to 11 in the survey. I recoded 1–4 as conservative and 8–11 as liberal and included two separate dummy variables, one for conservative and the other for liberal. In the South Korean context, conservatives value a collective identity more than an individual identity, economic growth over the distribution of wealth, hawkish attitudes toward the North Korean regime rather than conciliatory ones, and deference to authority over egalitarian attitudes (Jang Reference Jang2020; Kim Reference Kim2017; Lee and Lee Reference Lee, Lee, Lee and Lee2014). I included age, hometown, political cynicism, whether they voted for Park in 2012, household income, and education as the control variables, following studies analyzing South Korean voting behaviors (e.g., Hur Reference Hur2019; Kim and Park Reference Kim, Park and Kim2018; Yoon Reference Yoon2017).

Focus Groups

As I was interested in understanding why voters assessed Park’s political legacy the way they did in the survey, I ran six focus groups with 35 participants in South Korea in July 2021. Whereas the survey identified the overall response pattern generalizable to the population, the focus groups revealed the participants’ nuanced perceptions of Park’s election, impeachment, and the lasting impact on women’s political empowerment (Cyr Reference Cyr2017; Doody, Slevin, and Taggart Reference Doody, Slevin and Taggart2013). T Bridge Corporation, a research consultancy specializing in focus groups located in Seoul, recruited the participants using the ARS (from the company’s survey panel) and snowball-sampling recruitment via online communities. The participants completed a screening survey, which included questions about their age, gender identity, political ideology, place of residence, participation in pro- or anti-impeachment protests, and level of interest in politics (very, somewhat, not interested). To facilitate active discussions, those who said they were not interested in politics were not invited to the panel, even though I understand that such a decision could exclude certain types of responses. For logistical reasons, those who lived outside the Greater Seoul Metropolitan area, which is within two hours via public transit from the meeting space, were not invited to the panel.

Each group consisted of five to six participants with the same gender identity and political ideology (conservative or liberal) to create as comfortable an environment as possible for the participants to share their opinions (Cyr Reference Cyr2019; Hesse-Biber Reference Hesse-Biber2017; Morgan Reference Morgan2019), considering the political nature of the topic and the ever-widening gender and ideological polarization in Korean society. A survey in South Korea in 2019 reported that the gender divide is perceived to be the third most divisive political divide in Korea, following economic inequality and ideological conflicts (Gonggonguichang 2019). The vibrant #MeToo movement (Hasunuma and Shin Reference Hasunuma and young Shin2019); controversy surrounding online feminist communities such as Megalia and Womad (Evans Reference Evans2016); and the 2022 presidential election of Yoon Suk-yeol, whose campaign promises included the abolishment of the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family and penalizing false accusations of sex crimes (Gunia Reference Gunia2022; Lee Reference Lee2022) exemplify the deepening gender conflicts in the country.

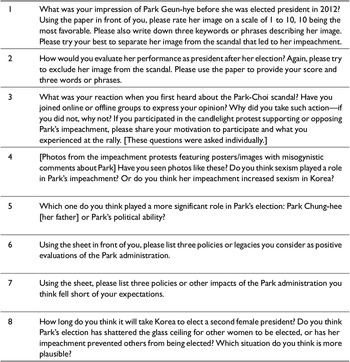

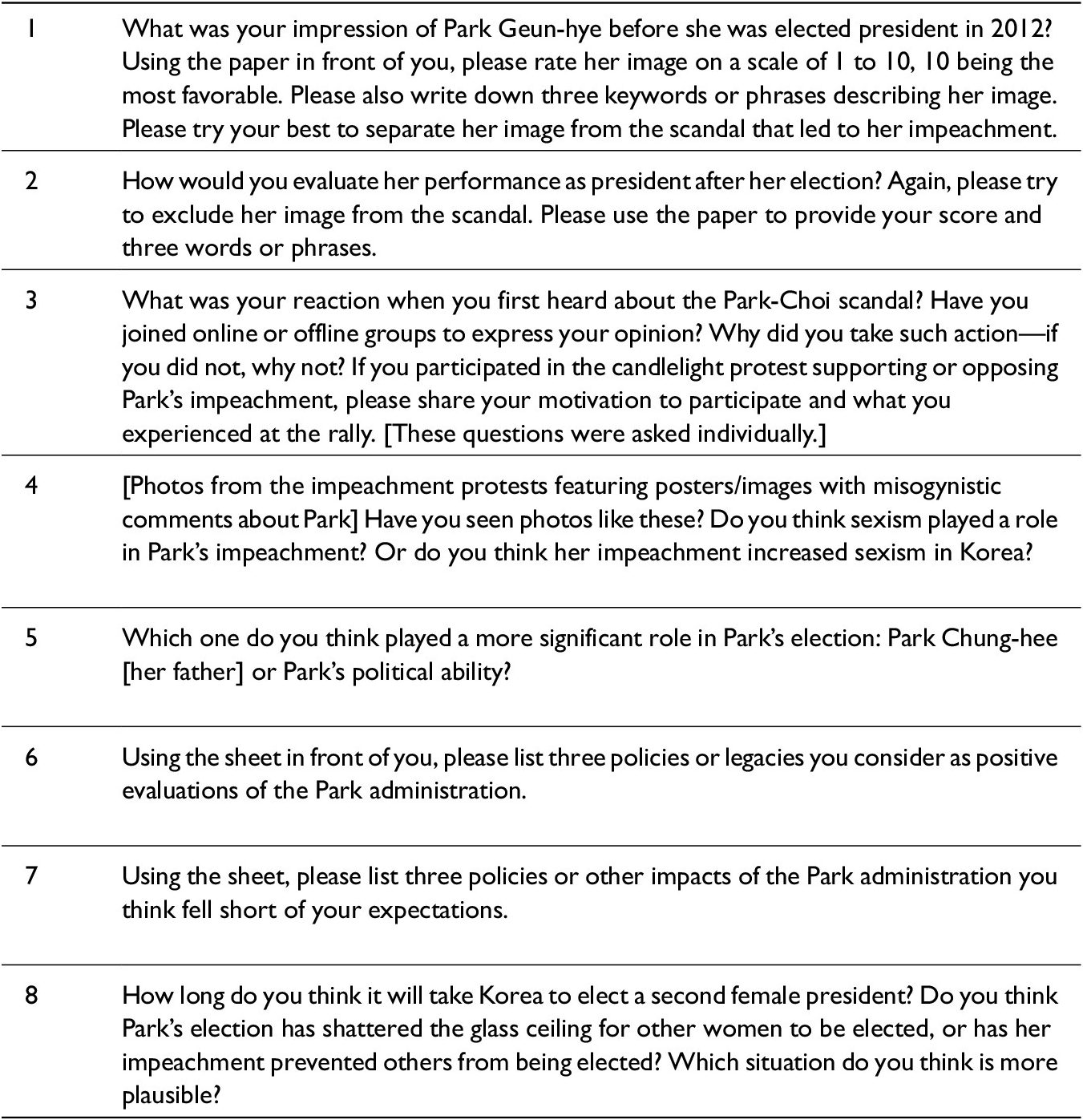

The 35 participants were between the ages of 25 and 67, and each group had participants in their 20s, 30s, 40s, 50s, and 60s, except for an online focus group with liberal women in their mid-20s and early 30s (Group LW2030). The participants were all strangers to each other (Table 1). A male moderator from the research consultancy, T Bridge, led the three men-only groups, and I facilitated the three women-only groups to further promote the free sharing of opinions by the participants. During the two-hour sessions, the participants discussed to which factors they attributed Park’s election and impeachment, whether they thought Park’s gender played a role in her impeachment, and whether the participants expected Park’s impeachment would make things more difficult for other female candidates (see Table 2 for the complete focus group questionnaire). The sessions were conducted in Korean. I chose six groups to balance the diversity of groupings, the possibility of reaching data saturation (Cyr Reference Cyr2019), and practical considerations involving costs. The participants received approximately $65 in cash to compensate for their two-hour participation and travel time.

Table 1. Focus group composition

Table 2. Focus group questionnaire

The eight main questions can be translated as follows:

I analyzed the transcriptions of the video-recorded sessions. First, I located all mentions related to the questions of interest. I used open coding to identify emerging themes and then categorized the entries by conceptual themes (Morgan Reference Morgan2019) (See Appendix 3 in the Supplementary Materials for the counting table, including t-tests). Then, I reanalyzed the transcripts to interpret the patterns identified in the counting tables (Morgan and Zhao Reference Morgan and Zhao1993). Even though I checked how frequently each theme emerged and who the speaker was, focus group results are not typically generalizable due to the sampling frame and the small sample size (Cyr Reference Cyr2019). As the survey analysis was used to identify the general patterns in responses, I mainly used the focus group data to provide in-depth contextual details and reasoning for their answers (Cyr Reference Cyr2019). Two doctoral students, native Korean speakers, reviewed the transcripts and video recordings for accuracy before I started coding the data. Even though they did not code the transcripts themselves, I consulted them after my preliminary analysis to improve the validity of my findings. Appendix 4 in the Supplementary Materials includes selected quotations illustrating themes from the focus groups.

Results

Gender, Political Ideology, and Symbolic Representation

I analyzed the participants’ responses to two survey questions—“Park contributed positively to women’s political representation by being the first female president of the country” and “The Park administration implemented many women-friendly policies”—to measure symbolic representation. Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics of the results as well as the regression results. Approximately 40% of the respondents agreed that Park being the first female president contributed to women’s political representation, but only 17% of respondents thought her administration promoted policies to promote women’s rights and gender equality.

Table 3. Perceived contribution of Park to women’s empowerment through symbolic representation and policy making

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses. OLS regressions with survey weights (education, class self-identification, and political ideology). The dependent variables are measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale, with 5 being “strongly agree.” The control variables include age, hometown, political cynicism, support for Park in 2012, household income, and education. See Appendix 4 in the Supplementary Materials for the full models. * p < .05.

I expected female voters to have more positive views of Park’s election than male voters (the gender affinity hypothesis). Contrary to my expectations, the responses to both questions revealed no significant gender gap. Women were more likely to agree that Park’s status as the first female president was noteworthy but the coefficient did not reach statistical significance (t = 1.84). I expected conservatives to express attitudes that were more favorable about Park promoting symbolic representation than their liberal counterparts (the ideological affinity hypothesis). The OLS regression results show that the conservatives were more likely to agree with both statements, supporting the hypothesis. The liberal participants were less likely than were the others to agree that the Park administration promoted women-related policies, again supporting the ideological affinity hypothesis (Table 3).

The participants in all six focus groups mentioned the “first female president” in their discussion without being prompted. Considering that none of the participants referred to President Moon Jae-in as the 18th male president of South Korea, mentioning Park’s “first” status suggests that her being the first had registered in voters’ minds either positively or negatively. Eleven of the 35 participants said that the prospects of electing the country’s first female president shaped positive expectations for them, but 22 people mentioned that the prospect did not excite them (see Appendix 3 in the Supplementary Materials). Multiple participants commented that “Park was not a female president” and “Park was just biologically a woman.” Through probing, I identified two common reasons why the participants did not attribute Park’s election as a sign of gender equality and progress in politics.

“She Did Not Earn It”: Dynastic Politics and Symbolic Representation

The focus group participants emphasized that Park was heavily indebted to her father for her entry into politics, and her gender was not an important campaign issue. As an icebreaker, the focus group participants wrote three words or phrases that came to their mind when thinking about Park before her presidency (Table 2). Of the 30 in-person participants, 25 people wrote words or phrases related to Park’s father, such as “the first daughter,” “the acting first lady” (she served as the first lady when her mother was assassinated), “the princess,” and “a hothouse flower,” suggesting that she lived a sheltered life as the daughter of the president. They argued that Park was elected on a wave of nostalgia for her father rather than as a woman’s representative. Therefore, they did not think she deserved the title of a trailblazer who shattered the glass ceiling. Unlike the other groups, however, the conservative male participants, who tended to have a favorable evaluation of Park’s father as the president who led South Korea’s industrialization, viewed her dynastic origin as a positive factor when evaluating her competency. They connected Park’s family ties to political socialization and her preparedness as a candidate. One participant mentioned, “Probably she picked up something from watching her father” (CM–Rally, Participant #4).

“Park Was Not a Woman President”: Life Experiences and Relatability

The focus group participants reported that Park’s parental and marital status initially shaped positive expectations of her. Three conservative women mentioned that Park’s unmarried, childless status was a positive factor for her image, at least before her impeachment. They expected Park to be selfless, and considered Park’s decision not to marry as a sign of her commitment to public affairs. Moreover, they anticipated a corresponding low likelihood of nepotism and corruption involving family members, a chronic problem in South Korean politics. Park herself emphasized her unmarried status as a positive factor in her 2012 campaign for the same reason. She repeatedly said that her role model was Queen Elizabeth I, who proclaimed that she was married to her country (Shin and Kim Reference Shin and Kim2013).

The same factor, however, undermined voters’ expectations about Park’s policy responsiveness and relatability as her performance started to decline. None of the groups listed specific women-related policies when asked what they considered her administration’s policy successes. This lack of acknowledgment of Park’s contributions through policy making was similar to the survey pattern, in which only 17% of the respondents agreed that her administration promoted women-related policies (Table 3). Some participants repeatedly brought up the fact that Park had never married and did not have children as the reason for her inability to represent women’s interests. The participants who mentioned that they had children at the beginning of the focus group session presented such arguments, regardless of their political ideologies. For them, Park’s single status without children suggested she was out of touch and did not understand “ordinary” women’s concerns, such as increasing housing prices, child support costs, and education systems. None of the LW2030 group members—all of whom were unmarried liberal women—brought up Park’s marital or parental status during the entire session. Other words that the participants used to describe Park’s lack of relatability were “princess” and “queen.” The words appeared in all six groups. Not only do these words carry connotations of her origins in a political dynasty, but they also suggest that voters did not consider her “one of them” with similar life experiences and challenges.

Existing studies of motherhood and women’s politics have corroborated the opinions of the focus group participants. Even though motherhood and a status as the primary breadwinner of the family discourages women from running for office (Bernhard, Shames, and Teele Reference Bernhard, Shames and Teele2021), public officials and voters prefer candidates with “traditional household profiles” (married with kids) (Heilman and Okimoto Reference Heilman and Okimoto2007; Teele, Kalla, and Rosenbluth Reference Teele, Kalla and Rosenbluth2018). Mother candidates gain electoral advantages by underscoring their understanding of women’s experiences (Deason, Greenlee, and Langner Reference Deason, Greenlee and Langner2014). Jacinda Ardern enjoyed “a baby bump for women’s rights” as her pregnancy during her term was perceived as a step toward gender equality (Galy-Badenas and Sommier Reference Galy-Badenas and Sommier2021). Examples of women being questioned for not having children are abundant, including Theresa May (Quinn Reference Quinn2019), Angela Merkel (Wiliarty Reference Wiliarty and Murray2010), Helen Clark (Trimble and Treiberg Reference Trimble, Treiberg and Murray2010), and Benazir Bhutto (Liswood Reference Liswood1995). While pursuing political leadership can be seen as violating the gender norm, being a mother can present an image of having communal qualities such as warmth (Brescoll and Okimoto Reference Brescoll and Okimoto2010).

When the participants said that “[Park] is not an ordinary person” or “she is not a woman politician,” they were referring to her privilege. The participants who attributed Park’s election mainly to her inherited support base did not feel her election marked an improved level of democracy or women’s political empowerment, nor did they feel she had an understanding of “ordinary people” to promote women’s interests. Voters expect more than descriptive similarity, expecting a female leader whose narrative of her life story resonates with them.

A Second Female President of South Korea?

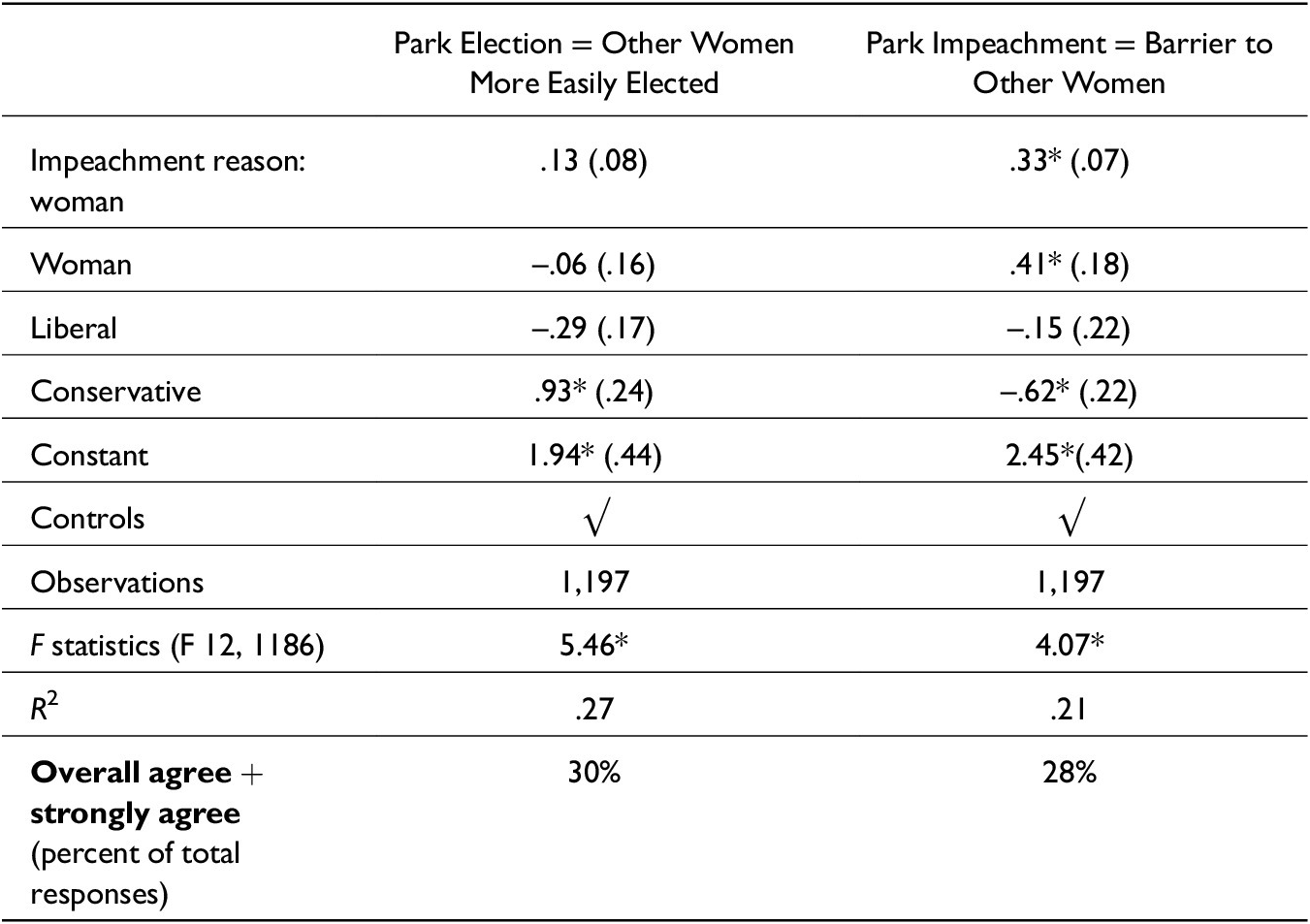

To assess how voters evaluated Park’s lasting impact on women’s political empowerment, I asked two survey questions: “As Park’s election shattered the glass ceiling, her electoral victory would make other women’s election easier than before” and “Park’s impeachment would make it difficult for other women to be elected as a legislator or president.” I expected those who attributed Park’s gender to her impeachment to hold pessimistic views about other women’s political advancement (the barrier hypothesis). Overall, approximately 30% of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed with each statement (Table 4). To measure those who attributed Park’s gender to her impeachment, I asked the survey question, “One of the reasons for Park’s impeachment and conviction is the fact she was a woman.” Approximately 13% of the respondents said that being a woman was the reason for Park’s impeachment.

Table 4. Impact of Park’s election and impeachment on a second female president

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses. OLS regressions with survey weights (education, class self-identification, and political ideology). See Appendix 4 in the Supplementary Materials for the full models. * p < .05.

The regression results show statistical evidence supporting the barrier hypothesis. The conservative participants positively rated the effect of Park’s election on the ability of other women to be elected (supporting the ideological affinity hypothesis); the women and liberal participants tended to disagree, but the coefficients did not reach statistical significance. Those who attributed Park’s gender to her impeachment were more likely to see Park’s failure as a barrier to other women’s political careers. The female respondents also worried that Park’s impeachment would impede other women’s elections, in opposition to the gender affinity hypothesis, which predicted a positive impact on symbolic representation. The conservatives did not agree that Park would be a barrier to other women, supporting the ideological affinity hypothesis.

Unlike the survey respondents, the overwhelming majority of the focus group participants expected that the country’s second female president was unlikely to be elected anytime soon after Park’s impeachment (24 of 35 participants). Women were more likely to have a pessimistic view than were men, and the difference was statistically significant (see Appendix 3 in the Supplementary Materials). Similar to the survey, two-thirds of the focus group participants disagreed with the statement attributing Park’s gender to her impeachment (22 of 35 participants); conservatives were more likely than liberals to agree that Park’s gender and sexism was a reason, and men were more likely to say so than women (statistically significant). All women focus group participants, regardless of their political ideology, squarely rejected the notion that sexism played a role in her downfall. They thought Park’s impeachment was unrelated to her gender but was absolutely related to her incompetency (see Appendix 3 in the Supplementary Materials). The impeachment confirmed their concerns about Park’s competency, as they thought she merely rode the coattails of her father without merit. The participants used words such as “puppet,” “robot,” “doll,” “regency,” and “using international trips for her fashion show” to describe Park’s incompetency and lack of agency as president.

Individualizing Gender Issues

All 11 focus group participants who thought that Park’s gender played a role in her impeachment were men, and 10 of them were conservative. How can we understand this seeming paradox—conservative men decrying Park’s being convicted for her gender? Even though these men disagreed that sexism played a part in Park’s impeachment, they reasoned that Park could not “assertively respond” to the demand for impeachment because she was a woman, illustrating the differences between men’s and women’s leadership styles (CM–Rally, #3). Similarly, she did not have the guts to fight against the demand for resignation/impeachment and should have used any means to be acquitted; she could have even considered using military forces against the protesters (CM–Rally, #5). This is an example in which the strength of the focus group as a data collection method shone through by revealing how people think and talk about specific subjects, rather than having researchers impose a definition of a particularly complex concept for a survey (Cyr Reference Cyr2017, 1039). These conservative men interpreted the statement “Park was impeached because she was a woman” as a reflection of Park’s individual quality as a woman leader. Other focus groups assumed that the question was about whether they thought impeachment was a reflection of voters’ sexism and misogyny against a female politician.

Of the 35 participants, 24 expected that electing a second female president is unlikely anytime soon in South Korea. When asked why, an interesting difference emerged that aligned with the participants’ ideologies. Ten of the 18 conservative participants thought the lack of competent female politicians was the problem, not discrimination against women or other societal-level problems. In contrast, 11 of the 17 liberal participants argued that Park’s impeachment revealed and reinforced the prevailing bias against women in politics (see Appendix 3 in the Supplementary Materials). This response pattern, along with the conservative men’s connecting of Park’s gender to her individual ability as the leader, showed that the conservative participants tended to individualize gender issues, whereas the liberal participants saw gender as a structural issue.

Women’s Political Awareness: Unintended Positive Gains

Overall, 30 focus group participants commented that Park’s impact on women’s political representation was negative, but 19 participants commented on its positive aspects (some mentioned both). These patterns do not show a statistically significant difference by the participants’ ideology or gender. Almost all the positive impacts mentioned by liberal women were unintended consequences: Park’s impeachment helped women become more interested in politics and propelled them to participate in protests for the first time. The participants opined that this experience led women to become politically more involved and mobilized, and witnessing a successful impeachment led them to feel that their voices now mattered (LW2030, #4). Studies have shown a positive connection between the descriptive and symbolic representations of women in the form of an increased level of interest and participation in politics. Ironically, Park’s failure, not her election, empowered women to participate in politics and voice their grievances.

Conclusion

When the first female political leader “fails,” what is the effect on voters’ perceptions of women as political leaders? Do voters evaluate her as a “trailblazer” for breaking the glass ceiling, or do they feel that she shut the door? When the first female president comes from a political dynasty, does she still elicit perceptions of symbolic representation even though gender is seemingly the only common denominator between her and the public? I answered these questions by analyzing South Koreans’ evaluation of Park Geun-hye’s legacy, utilizing original public opinion surveys and focus groups.

Ideological rather than gender affinity played a more significant role in the voters’ evaluation of Park’s contribution to symbolic representation and women’s political empowerment. The data did not provide evidence that women voters felt more represented after the election of the first female president of the country. Even though Park received some credit for being the first female president, her privileged background—which conferred on her several nicknames, such as “princess” and “queen,” throughout her political career—and being a single woman without children caused voters to question her ability to relate to “ordinary” people’s concerns and understand women’s hardships in a patriarchal society. The participants also did not think that Park promoted women-friendly policies as president. Given that Park emphasized her status as a dutiful daughter of her father more than her status as a women’s representative, voters’ weak acknowledgment of her contribution to gender equality should not come as surprise. When multiple focus group participants repeatedly said “Park was not a woman president,” they were not questioning her gender identity. Rather, they were asking “which women” she represented. Although tapping into family ties can increase the odds of women’s electoral victories, such an entry into politics does little to change voters’ belief that politics is men’s domain. Park’s dynastic connection and lack of commitment to promoting women’s representation and political empowerment caused voters reluctant to credit Park as a “woman president.” The female focus group participants were concerned that the epic failure of the first female president would reinforce the country’s reluctance to vote for women. The most recent WVS data corroborate their concerns.

Because of the seeming rarity and extreme nature of Park’s case, the findings of this study might not seem to be generalizable to other cases. Even though it is becoming less frequent, tapping into family ties is not uncommon, as evinced by the recent Philippines election in 2022, in which the son of Ferdinand Marcos and the daughter of Rodrigo Duterte became the president and vice president, respectively. At the same time, studies examining descriptive and symbolic representations of women should adopt an intersectional approach, paying attention to the societal and individual contexts of leaders, to elicit nuanced understanding of how particular gender norms in different societies shape unique and particular structures of injustice (Davidson-Schmich Reference Davidson-Schmich2011; Weldon Reference Weldon2006). The highly unusual circumstances of Park’s impeachment laid bare society’s deeply held beliefs, such as gender stereotypes, presenting an opportunity to examine how sexism persists even after the highest glass ceiling was seemingly shattered. This study uncovers particulars of the case and thus deepens and complicates the scholarly understanding of leaders’ exits and their impacts on symbolic representation. As women’s electoral success and political failure become more common, future comparative studies should examine whether the findings from this study can be applied to other cases.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X22000538.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by the Academy of Korean Studies (Project No. AKS-2020-R52), the American Political Science Association’s 2021 Spring Centennial Center Research Grants, and the 2021 Research and Creative Activity Faculty Awards by California State University, Sacramento. Special thanks to Minseok Jeong and Kyunghyun Ro for reviewing and correcting the focus group transcripts and collecting Korean publications. An earlier version of this article was presented at the 2021 Southwest Workshop on Mixed Methods Research and at a monthly research seminar at Sogang Institute of Political Studies. I thank the discussants and participants of these workshops for thoughtful comments. My journal reading club members—Kylee J. Britzman, Danielle Joesten Martin, and Joel Mehic-Parker—helped me keep up to date with the gender politics literature.