Introduction

The study of highlife has gained attention in music scholarship. Quite a number of scholarly oeuvres, such as Collins (Reference Collins1989, Reference Collins1994, Reference Collins2001, Reference Collins2005, Reference Collins2010, Reference Collins2018), Sunu Doe (Reference Sunu Doe2011, Reference Sunu Doe2013), Coffie (Reference Coffie2012, Reference Coffie2018 Reference Coffie2019, Reference Coffie2020), Plageman (Reference Plageman2013), Emielu (Reference Emielu2013), Aidoo (Reference Aidoo2014), Agyeman (Reference Agyeman2015), Marfo (Reference Marfo2016), Yamson (Reference Yamson2016) and Sowah (Reference Sowah2017), among others, have discussed the various aspects of highlife music. These includes social history, biographical and analytical studies on notable composers and their works, and textual meanings of highlife songs. It is worth emphasising that the above studies have increased the knowledge and understanding of the historical and theoretical perspectives of highlife music. However, an investigation into the soundscape of highlife music, which is the end product and the physical manifestation of the music, is still a desideratum in Ghanaian music scholarship. It is against this background that a study in this direction is very appropriate.

A preliminary investigation on recorded highlife songs of the 1950s to 1970s reveals a disparity in the soundscape. It appears that the 1970s soundscape was geared to the ears of the local populace, and is slightly different in tone and ambience from that of the 1950s to 1960s. This socially constructed sound was pioneered by the Ghana Film Studio (GFS),Footnote 1 where Francis Kwakye was the prime highlife recordist from the 1970s onwards. Interestingly, his recording approaches became somewhat of a trajectory for other studios of the time including the Ambassador Records Studio, the Philips/Polygram Studio and Faisal Helwani's Studio One. It is the purpose of this paper to investigate the technological approaches to the production of highlife songs at the GFS and how they reshaped the highlife soundscape in the 1970s. It also draws attention to the influence of Francis Kwakye, the then resident recording engineer of GFS to explore highlife sound recordings within this period. The study employs case study as the research design and is framed within the theoretical lenses of Ghanaian nationalism and cultural identity. Data was collected through document review, audio review, personal observations and interviews with Francis Kwakye, Maame Akua Amoako (a highlife patron) and highlife music practitioners including Kofi Abraham, Charles Amoah and Nana Boamah. Finally, the study draws on K. Gyasi's Sikyi Highlife album recorded in 1974 to discuss highlife recording practices of the 1970s and document the legacy of Francis Kwakye and the Ghana Film Studio for posterity. This particular album was selected because it elucidates the totality of GFS's recording approaches and concepts in the 1970s. It is instructive to mention that Francis Kwakye was purposively sampled for this study because he is of advanced age, and is also the only surviving member amidst the array of local engineers trained by the GFS in the 1960s. Should he pass away, all of his knowledge would be gone, hence, the need to document his contribution and legacy to the recording industry in Ghana. The paper begins by exploring the cultural perceptions of sound in Ghanaian music-making.

Sonic imagination in Ghanaian music

As Timothy Rice (Reference Rice2014, p. 202) has observed, ‘musicians from every culture respond in one way or another to the animal and natural sounds of their environment’. He suggests that a cultural setting's acoustic dimensions correspond to the music-making exhibited in that society and must be understood by the indigenes in a common language. Music-making in such contexts often revolves around the cultural beliefs, linguistic intonations and practitioners’ social behaviour. In agreeing, Steven Feld (Reference Feld1984) asserts that natural sounds trigger music-making in the Kaluli society located in Papua New Guinea. According to him, the natural sounds are exemplified in styles of sound communication interpreted as melodies and rhythms by inhabitants (Feld Reference Feld1984). For instance, he argues that ‘weeping is thus equated with bird sound and links expressions of grief with the metaphor of turning into a bird’ (Feld Reference Feld1982, p. 16). It implies that natural sounds characterise the linguistic and vocal expressions among the Kaluli, thus shaping their social behaviour. Hence, one could tell where a person is from culturally just by the sound of their speech and social behaviour, otherwise referred to as ‘soundly organised humanity’ (Blacking Reference Blacking1973, p. 89). Marina Roseman's work on the Tamia of Peninsular Malaysia also discloses cultural symbolism in how other societies socially construct their sounds. She proposes that ‘to do so, we must compare not merely the enigmatic surfaces, not the sound structures per se, but primarily the cultural logics informing those structures’ (Roseman Reference Roseman1984, p. 411). In this sense, sound structure becomes a socio-cultural product constructed to suit a cultural group's philosophies and practices. From the above discussion, it is easy to agree that every society has its cultural perception of sound and its relation to music.

In Ghana's case, traditional, popular and art entertainment (music, dance and drama) historically and socially perpetuates cultural perceptions of sound based on the way of life among the various ethnicities in the country. Each of the ethnic societies in Ghana has a distinctive array of sounds rooted in mainstream music-making and observed by both the young and old. Thus, it validates Stuart Hall's (Reference Hall1992) hypothesis on the socio-historical construing of cultural identity, which according to him, is never static but constantly progressing. Some of the prevailing ethnic musics include adowa (Asante traditional music), agbadza (Ewe traditional music), apatampa (Fante traditional music), kpanlogo (Ga neo-traditional music) and baamaaya (Dagbᴐn traditional music).Footnote 2 The above local musical cultures’ attributes comprise the linking of music to dance and the use of polyrhythms, syncopations, modal progressions and speech surrogate instruments (mmenson, atumpan, etc.). Primarily, in traditional southern Ghanaian and indeed Nigerian drum ensembles, the most significant instrument and the one that does the soloing is the ‘master’ drum, with the higher pitched drums, bells and rattles providing the support rhythms. This suggests a usual preference for low-pitched drums as the leading instrument in most indigenous drum ensembles. For instance, Ewe drummers increase the bass resonance of the open-ended vuga drum they use in their borborbor dances by lifting it off the ground with the feet from time to time. This incidentally is the reverse of the European classical music convention, in which high-pitched instruments rather play the solos while the low-pitched ones are supportive. Although melody forms an integral part of music-making in Ghana/Africa, rhythm appears to be the outstanding musical element that corresponds to the various local dances at their cultural settings (see Chernoff Reference Chernoff1979). Kofi Agawu (Reference Agawu1995) posits that rhythm is intrinsic to the daily life of Northern Ewe people. According to him, rhythm supports their understanding of cosmic periodicity, suggesting when the society can aptly conduct specific musical performances (Agawu Reference Agawu1995). The narrative is profound to the Ewe people since rhythm typifies their language, song, drumming and dancing acts.

From an ecological perspective, Kwabena Nketia (Reference Nketia1974) avers that natural materials such as logs, gourds, calabash, seeds or beads are usually fashioned into specific indigenous musical instruments to certify the sonority of their cultural pitches. These include ntorowa or axatse (local rattle), atumpan, petia, apentemma, donno (local drums) and several others. In his book, The African Imagination in Music (2016), Agawu acknowledges that musical instruments used in traditional dance-drumming produce varied sound frequencies in their respective timbres. In most instances, the ‘master’ drums have low-end sounds, the supporting drums have mid-range sounds while rattle(s) and bell(s) demonstrate high-end sounds. Together these sounds constitute a balanced musical soundscape at the cultural level. For example, an adowa ensemble consists of instruments such as atumpan (low-range pitch), petia, apentemma, donno (mid-range pitches) and dawuro (high-ranged sound). This sound framework communicates both internal and external aural signal to musicians, dancers and general audiences in a language they understand, either knowingly or unknowingly. It is vital to emphasise that the internal perception of sonic materials goes beyond its exterior dimensions. The above tripartite sound model (low, mid and high) is symbolic of the many musical cultures in Ghana, including the popular music domains. In a typical palmwine music setting, the premprensiwa provides low-end sounds to sustain the performance's bass section. The local drum(s), vocals, seperewa or acoustic guitar(s) ensure the mid-ranged sounds while the rattle and bells provide high-end sounds. A similar instance is observed in the highlife performance arena: kick drum and bass guitar (low-end sounds), snare, congas, guitar, trumpet, trombone, organ, vocals, etc. (mid-ranged sounds), and bell, rattle/maracas, cymbals, etc. (high-end sounds). This represents a balanced highlife music soundscape, specifically from the 1970s onwards when wind instruments and electric keyboards (organ/piano) had become a prominent part of most highlife ensembles. However, a further elaboration of this aspect is provided in the subsequent section. Above all, highlife appears to be a thin line that musically connects the diverse Ghanaian tribes. Its trans-ethnic identity draws musical idioms such as dance rhythms, vocal styles, dialects and instrumental resources, among others from the various cultural groups in the country. The subsequent section discusses the development of Ghanaian highlife music.

Overview of the Ghanaian highlife music

Highlife music is one of the popular musical styles that emerged in Ghana around the 1920s through the hybridisation of musical elements from Africa, Europe and the African Diaspora (Collins Reference Collins1989). The music since its nascent stages has been dance-oriented, premised on two main performance structures, namely big-band and guitar band. The highlife big-band was modelled after American jazz swing big-bands of the 1930s that utilised brass orchestras (trumpets, trombones, saxophones, etc.) and rhythm sections including guitar, upright bass, piano and percussion (Schuller Reference Schuller1968; Collins Reference Collins2018). The jazz soundscape, which is a US national product, spread to other parts of the world through records and promulgated new musical interventionism in many geographical destinations including Ghana (Feld Reference Feld2012; Denning Reference Denning2015). In the local context, highlife musicians inspired by jazz music did not only enjoy the sound of the music but also emulated its performance practice. Most of them were tutored on jazz performance by a British saxophonist named Sergeant Leopard (Collins Reference Collins1994). Subsequently, musicians such as E.T. Mensah, Joe Kelly, Guy Warren, Tommy Gripman and King Bruce, among others, relied extensively on jazz repertoires during concert performances in the 1940s (Collins Reference Collins1986). The guitar bands at the time also drew on the compositional techniques of native styles such as ͻdͻnsͻn and adakam, developed in the 19th century, which mainly paired acoustic guitar or seperewa (traditional harp-lute) with local percussions.Footnote 3 The only difference is that guitar bands typically utilised electric guitar(s), bass and Latin American percussions during performances. Its exponents include E.K. Nyame, S.K. Oppong, King Onyina and numerous others. Bands then had a solid cohesion in terms of musical liveness that was relatable to the societal sentiments of Ghanaians around this period and beyond. The performance framework of highlife big-bands and guitar bands around the 1950s and 1960s constituted what was later termed ‘Classic highlife’ style. This style emphasised a higher degree of Ghanaian/African nationalism as it gained prominence around the era of the country's independence.

Kathryn Heinen (Reference Heinen2015) discusses how European composers individually projected a sense of nationalism by amalgamating familiar folk idioms with classical music and dance ideals in their separate countries. Similarly, Ghanaian highlife musicians around the 1950s incorporated indigenous instruments into their compositions and performances in a sankofa fashion.Footnote 4 The Tempos Band around this period introduced donno (hourglass drum) into their ensemble. The Ramblers International Band also paired atenteben (local bamboo flute) with its brass section in the 1960s (Marfo Reference Marfo2016). Beyond this, the Ramblers band further ‘combined traditional values and practices from different ethnic groups and blended them with contemporary elements to promote Ghanaian identity’ (Marfo Reference Marfo2016, p. 25). This cultural appropriation of indigenous musical knowledge was not a novel situation as local instruments such as bells, rattles and drums were already a part of the highlife culture, particularly within the guitar band circles. John Collins (Reference Collins2010) reveals that Dr Kwame Nkrumah,Footnote 5 upon realising the contributions of highlife music towards the creation of Ghanaian nationalism, involved some of the highlife bands on his political voyages across Africa and elsewhere. More so, President Nkrumah around the early 1960s arranged for the top five highlife big-bands (including Uhuru) to undertake ‘a three-month course in traditional drumming and dancing at the Ghana Arts Council in Accra whilst being housed at the nearby Puppet Theatre’ (Collins Reference Collins2010, p. 92).

Between the late 1960s and early 1970s, the highlife music scene undertook a new shape, a musical revolution comprising the transculturation of highlife, afro-beat, afro-rock and afro-jazz. According to Collins (Reference Collins2005, p. 24), the 1971 ‘Soul to Soul’ concert in Accra, which brought black artists such as Chubby Checker, James Brown, Tina Turner and Nigeria's Fela Kuti, the Osibisa Band among others, led to this transculturation experience. The era also saw the emergence of electric pianos and organs into the highlife musical culture. Hence, instruments such as guitar (acoustic/electric), percussion (local/Western), wind (trumpet, trombone and saxophones), bass (acoustic/electric) and electric keyboards (organ/piano) became the standard resources for highlife music performance. This new highlife soundscape, however, blurred the line between what was considered as big-band and guitar band around the 1970s. Because musicians at the time kept experimenting within this new instrumental resource, which Mark Coffie (Reference Coffie2012) refers to as the era of experimentation, this gave rise to newer dimensions of highlife music compositions and performance practices that seemingly side-lined the classic highlife style. The subsequent paragraph discusses three subgenres of highlife that emerged in the 1970s, including sikyi highlife, funky highlife and gospel highlife.

The sikyi style was a modal form of highlife music performed in a medley fashion (Coffie Reference Coffie2020), pioneered by K. Gyasi and the Noble Kings Band in the early 1970s. Principally, the African modal scheme used in this regard accentuates two tonal centres known locally as kwaw, an indigenous harmonic framework described as phrygian and lydian from Western interpretation.Footnote 6 The sikyi highlife style is characterised by a unique percussive bass expression derived from the performance practice of the local premprensiwa (a none melodic local instrument). This trait was invented and popularised by Ralph Karikari, a versatile Ghanaian musician and official bassist of the Noble Kings Band.Footnote 7 The next development of highlife music was the funky style. It was a blend of funk elements with highlife music (Coffie Reference Coffie2018), pioneered by C.K Mann and His Carousel 7 Band in the mid-1970s. The three prevailing features of funk comprise the ‘chicken scratch’ guitar sound (pioneered by James Brown), percussive slap bass and its long 4/4 time dance grooves (Steward Reference Steward2013). These elements did not only diversify the rhythmic structure of modern highlife music but also defined its compositional structure.Footnote 8 Notable musical examples include Dan Boadi and the African Internationals’ ‘Play That Funky Music’ and Alhaji K. Frimpong & His Cubano Fiestas’ ‘Hwehwɛ mu na yi won pena’, both produced in the 1970s. Ebo Taylor, a highlife great, observes with regard the style of his global hit song ‘Love & Death’ that: ‘we can call what we play funk life or funky life … this is highlife with strong influence of funk and jazz’ (Coffie Reference Coffie2019, p. 129). The gospel highlife style was a fusion of sacred text with highlife music, developed in the early 1970s (Collins Reference Collins2018). Its roots stem from the rise of Ghanaian Pentecostal churches around the 1950s whose religious services allowed the use of highlife music ensembles covering electric guitars, bass, percussions, etc. Those churches served as training grounds for some Christianised local musicians who utilised highlife instrumentation as a basis for their song compositions, as was done by the likes of E.K. Nyame, who occasionally recorded highlife songs with Christian lyrics around the 1950s (Collins Reference Collins2018).Footnote 9 It later advanced into a definite highlife style in the 1970s, pioneered by Kofi Abraham and the Sekyedumase Gospel Band. It should be notated that the above Ghanaian highlife subgenres were further developed in the succeeding decades. The next section provides an overview of the highlife recording industry from the 1920s until the 1970s.

Ghanaian highlife recording industry (1920s to 1970s)

Recordings of local artists labelled as ‘native records’ pioneered the Ghanaian record business in the late 1920s (Collins Reference Collins2018). These ‘native records’ comprised seminal works of guitar band legends including George William Aingo and the Kumasi Trio, recorded by the Zonophone Company in London (Collins Reference Collins1994; Sarpong Reference Sarpong2004; Denning Reference Denning2015).Footnote 10 The period saw phonographic recordings embracing electronic features such as microphone, amplification and disk recording (Maxfield Reference Maxfield1926). At the time, the sound of any recorded music globally had a similar mechanical mid-based output: more like listening to music via the telephone. This was due to the primitive nature of recording technology that negated the reproduction of low and high sound frequencies. Recorded music then was pressed onto shellac 78 rpm records, a technology developed together with the gramophone by Emile Berliner in 1887 (Jones Reference Jones1985; Martland Reference Martland2013). This invention became one of the earliest breakthroughs in the evolution of sound reproduction that was patronised universally by fans of recorded music. As a result, Ghanaian entrepreneurs who could afford the gramophone referred to its records in the local parlance as ‘gramophone apaawa’, an archetype label generalised for all subsequent carriers of recorded music.Footnote 11

In 1948, Decca Records (a British multinational company) established West Africa's first recording studio in Accra, Ghana (Collins Reference Collins2018). This company recorded and produced most classic highlife albums of the 1950s and 1960s, spanning bands such as E.T. Mensah's Tempos, King Bruce's Black Beats, the Stargazers, E.K. Nyame's Guitar Band, Akompi's Guitar Band, Jerry Hanson's Ramblers International Band and several others. The era witnessed the upsurge of magnetic tape recording comprising the use of reel-to-reel tape recorders (single track) and a microphone. Owing to the limited recording technology at the time, the recording approach was more like the ‘what went in is what came out’ phenomenon. Further, the constant social interactions between highlife musicians and recording engineers during studio sessions informed the recording approaches in their specific projects. It is instructive to add that the interactions were necessary as the availability of equipment also contributed to shaping the eventual musical output. The recording process then involved the arrangement of musicians around a single microphone placed appropriately within the recording space per the directives of the engineer. Britain then served as the hub where tapes of recorded Ghanaian musics were pressed. Thus, I argue that the imagination of earlier highlife sounds on records resonated with a Western socio-cultural viewpoint. E.T. Mensah and his highlife contemporaries were jazz-inspired (Coffie Reference Coffie2012; Aidoo Reference Aidoo2014). Therefore, they expected the sound of their music to match the sonic ideals of American jazz big-band recordings, which around the 1950s had been shaped by Rudy Van Gelder (then resident engineer of Blue Note Records).Footnote 12 According to Skea (Reference Skea2002), Gelder's definition of jazz sound notable in the works of Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Miles Davis and John Coltrane, among others was adopted as a framework for music recording by other record companies of the era, which explains why the global popular music industry between the 1950s and 1960s had common similarities in recording approaches and sound representations. Engineers then employed the sound of popular hit songs as a reference guide for local productions, evident in the sound of most classic Ghanaian highlife records. An instance is E.K. Nyame's Tete Quashie album which was labelled as a ‘Blues record’ and engineered as such by Decca Records (Ghana).Footnote 13 Also, the 1960s witnessed the shift from shellac (78 rpm) records to vinyl (45 and 33 rpm) records in Ghana, although this change had happened around late 1940s in the Western world. The 45 rpms introduced the highlife music industry to a new paradigm of single recordings within a duration of 3 minutes. For instance, Ghana's Ramblers International Band recorded in permanent form singles within the timeframe of 2–3 minutes, notable in works such as ‘Work and Happiness’ (2:57 – side A) and ‘Nyimpa dasenyi’ (2:42 – side B), released on Decca's GWA 4116. Another significant innovation of the era was the introduction of the fader for closing recorded songs. This was quite at odds with the usual format in highlife music that was not only longer, but also ended with a coda and was never faded out electronically.

Around the same period, Ghana's independence and quest for Ghanaian nationalism signalled a remarkable turning point in the country's record business. As a result, in 1964, the Ghana Film Industry Corporation (GFIC), a state-owned company located in Kanda, Accra, was established. The GFIC was originally film-oriented, notable for classic Ghanaian movies such as I Told You So, You Hide Me, Do Your Own Thing, They Call It Love, Struggle for Zimbabwe, Angela Davies, and many others (Tamakloe Reference Tamakloe2013). Apart from film production which was the core operation of the agency, there were also music recordings alongside it. Bill O'Neill, a Canadian sound expert, established the music recording section as part of the activities of the sound department under the directives of president Nkrumah.Footnote 14 He designed the acoustics of GFS's recording space (present-day TV3 Limited's studio B) and became the first head of GFIC's sound department.Footnote 15 The GFIC's sound/music department was then referred to as the GFS. Portable Nagra tape recorder (single track) and a microphone initially served as the main recording equipment at the GFS. Some of the GFS's 1960s highlife recordings include K. Gyasi's ‘Owuo tᴐn a tᴐ bi’, C.K. Mann's ‘Adoma/Ammfa wohuam’, African Brothers Band's ‘Aponkyerene’, Kwaa Mensah's ‘Obi bɛyɛ yie/Nsamanfo’ and numerous others. Recorded music then was taken to London for pressing. This recording approach was maintained until the late 1960s when GFS purchased new recording devices to enhance the dexterity of its local music recordings, namely a Telefunken Magnetophon 2-track mono tape recorder, a 12-track Neve mixing desk and variety of microphones (both condensers and dynamics). This new technology permitted the experimentation of two or more microphones in 1969, but was best explored in the 1970s. Also, the normal penchant for making extended recordings (33 rpms) in Ghana and Nigeria commenced around the 1970s.Footnote 16

The highlife music trade around this period was thriving with over 200 local bands (Collins 2018); hence, GFS became a hub for most musicians to record their songs. It is essential to point out that GFIC trained many Ghanaian sound engineers in the 1960s including Steve Ampah, Edward Tettey Bassa Browne, Jacob Sedzro, David Ankora, Bossman Amoako and Francis Kwakye, among others. However, Francis Kwakye emerged as the prime highlife recording engineer at the Ghana film studio from the early 1970s onwards. The reason for this was that most of GFS's senior staffs (including sound engineers) had sojourned to India for further studies in filmmaking around that period.Footnote 17 The next section discusses Francis Kwakye's life and socio-cultural influences.

Francis Kwakye's Life and Influences

Francis Kwakye's life history within the music-making ecology of Ashanti and Greater Accra regions of Ghana generally posed a divergent imagination for highlife sound on record contrary to earlier highlife sounds. Born into the Asafo royal lineage of Kumasi, Ashanti region (Ghana) in 1948, Kwakye was exposed to traditional music performance and its sound production daily.Footnote 18 Further, his associations with Kwame Nkrumah's ‘Young Pioneers’ initiative around the 1950s trained him as a trumpeter.Footnote 19 His experiences within the brass band music traditions of the era likewise broadened his horizon on the appropriation of brass instruments and their sonic nuances in the Ghanaian context. Through an uncle called ‘B. Boy’,Footnote 20 Kwakye experienced music performances by highlife big-bands and concert parties organised by guitar bands around the late 1950s onwards. It made him aware of the scope of highlife soundscape until his official engagement with GFIC in 1969. Kwakye adapted this musical knowledge and directed them towards the redefinition of highlife sound on records around the 1970s, to purposely suit the social ears of Ghanaians raised in similar acoustical environments.

William Moylan (Reference Moylan2002) discusses sound as both physical and cognitive ideas perceived through the human ear and mental interpretation. Meaning, sound and its intricacies are understood and constructed by the human body. The human body, although physical, is a cultural product (Farnell Reference Farnell1999; Wolputte Reference Wolputte2004). Its sensitivities – what it hears, sees, feels, smells, and perceives – are socially determined. Tomie Hahn (Reference Hahn2007, p. 1) refers to this process as ‘knowing with your body’, inferring that artistic expressions (music, dance, drama, etc.) are accumulated and comprehended through bodily functions within a socio-cultural context. In essence, people become the embodiment of knowledge acquired in the course of life and transmit it to others. Accordingly, Kwakye embodied the highlife soundscape and channelled it into highlife studio productions which Ghanaians could relate to. He was aptly immersed with the sonic imagination of local musical cultures intrinsic to the local population. Thus, Kwakye recorded and mixed Latin American percussions to match the sound of indigenous percussions symbolic to the diverse ethnic groups in Ghana. Explicitly, he matched the sound of Western maracas to local rattle, Latin American clave to local castanet/bells and Western congas to local drums and engineered them from a Ghanaian interpretation of sound. Thus therefore supports Roshanak Kheshti's (Reference Kheshti2009, p. 15) claim that ‘sonic representations of culture nonetheless include an imposed layer of meaning mediated by the body and ears of the ethnographer, recordist, editor and producer’.

Kwakye's understanding of socio-cultural perceptions of sound and music-making at the local context guided his engineering ethics and ethos, which according to him was propelled towards a reflection of Ghanaian nationalism.Footnote 21 His nationalist inclination was prompted by Kwame Nkrumah's ideologies which advocated the accentuation of Ghanaian/African identity in all state-owned corporations including the GFS. Hence, GFS crafted highlife productions to suit the national identity of the local people and to project Ghanaian cultural sound to the global world. This corroborates Reginald Koven's (Reference Koven1909, p. 390) assertion that ‘for music to be great, and universally recognised as such must in a sense be national’. I therefore argue that the recording engineer as a culturally embodied figure is the representative of the home country and its sound definition as the studio context. He becomes a mediating tool in the interpretation of sound that must resonate with the social ears of consumers within that specific community. The next section positions Francis Kwakye at the Ghana film studio to discuss how his accumulated knowledge in Ghanaian cultural sound was applied at the studio context.

Ghana Film Studio and Francis Kwakye's Legacy in the 1970s

Francis Kwakye's ingenuity towards 1970s highlife recordings was incited by personal observations within the highlife soundscape of urban Accra and Kumasi respectively. He narrates:

In the course of my professional career, I realised that bands performed much better during live concerts compared to the studio context. And to duly situate the concert experience at the studio setting, I worked with some of these bands as a part-time sound engineer just to register a concert framework on my mind and implement it at the studio.Footnote 22

Results of his observations at the concert contexts suggested a new direction for highlife music recordings. According to Kwakye, he first perceived the performance settings of the various highlife bands and developed blueprints for each group.Footnote 23 Through this, he was able to accentuate the performance setting of the individual bands in a mirror viewpoint (stereo imaging) at the studio for identity purposes. He further studied the acoustical characteristics of available musical instruments during live performances and emulated them in the studio context. Further, Kwakye observed elements in songs that evoked dance and audience appreciation: a concept that ethnomusicologists use in analysing the groove of a performance (see Feld Reference Feld1988; Meneses Reference Meneses2014). He realised that audience participation in the form of dance, cheers and sing-alongs during live performances was a causative factor in the adroitness of highlife performances. Hence, at specific instances, live audiences were hosted in the studio context to boost the liveliness of certain recording projects. Such arrangements were usually made by music producers or bandleaders to convey highlife aficionados into the studio context to create an equivalent concert atmosphere. To mitigate technical hitches, the studio audiences were generally positioned farther from the performers, taking into account the recording space. GFS had a large recording booth that could hold many people without crowding. Therefore, Kwakye captured highlife music at close range to reflect its sense of closeness to Ghanaians. In other words, he intended to make Ghanaians relate to highlife music on records in the same manner as a concert experience. Maame Akua Amoako (an elderly food vendor) attested to this during a discussion. She averred that ‘any time I listen to highlife music of my time, “the 1970s”, I feel like the musicians are performing in my room’.Footnote 24 This engineering model became what was termed ‘Ghana Film Sound’ in the 1970s and was replicated by all GFS engineers who likewise manned the available studios including Philips/Polygram Studio, Faisal Helwani's Studio One and Ambassador Records Studio. This was revealed during separate encounters with highlife stars such as Nana Boamah (highlife musician/sound engineer), Charles Amoah (burger highlife musician/producer), K.K. Kabobo (veteran drummer/artist) and Kofi Abraham (gospel highlife musician).Footnote 25

Towards GFS's recording process in the 1970s

This paper draws primarily on K. Gyasi and the Noble Kings Band's 1974 Sikyi Highlife album, to discuss GFS's recording methods in the 1970s. The album was recorded by Kwakye at the GFS and pressed on vinyl 33 rpm record. The Noble Kings Band was originally a guitar band that had embraced the musical reformation of the 1970s. This band was the first to introduce electric organ and brass instruments into the highlife guitar band culture. Hence, the musical instruments outlined for the recording session encompassed percussion – claves, dawuta (double bell), ntorowa (rattle), Western congas and drum-set – as well as the melodic instruments comprising a brass section (two trumpets and an alto saxophone), lead guitar, bass guitar, electric organ and vocals. Again, the sikyi highlife album featured notable local musicians, namely Thomas Frimpong (lead vocal/drum-set), Ralph Karikari (bass guitar), Eric Agyeman (lead guitar), Ofori Frimpong (organ), Paul Willie (claves), Dotun Obajimi (rattle), Kofi Tawiah (congas), Kelly Koomson (first trumpet), Tommy King (second trumpet), Atta Kennedy (alto saxophone) and K. Twumasi (background vocal). The album spans 36 minutes 25 seconds on both side A and B. It contains the following songs: ‘Yɛde aba’, ‘Mene menua mienu’, ‘Sabarima’, ‘Ɛbia nie’, ‘Amintiminim’, ‘Siakwaa’ and ‘Nana Agyei’ on side A. On side B, ‘Efie ne fie’, ‘Nyankonton nko nyaa’, ‘Kwankwaasem nti’, ‘Egya ananse yi wonan baako’, ‘Kwaadede meyare merewu’ and ‘Ɛda a mewu’. In the first 45 seconds, Mike Eghan (then a notable MC at concert events) introduces the Noble Kings Band and the album's title/concept to the studio audience – a typical concert ideal emulated at the studio context.Footnote 26

The recording process during this era was tentative as the size of a band dictated the number of microphones. Spatial dimensions (reverb and delay) were acoustically captured within the recording space since hardware mechanisms were unavailable in Ghana at the time. Kwakye, the chief engineer, would often ensure that all musical instruments were perfectly tuned and resonated with the acoustics of the recording space.Footnote 27 This was because bands then performed together in a single take, as the possibility of doing separate overdubs was not a common practice until the 1980s. Hence, in the event of a mistake, bands had to restart the entire performance session.

In the case of sikyi highlife, the musicians were set up appropriately and performed together with microphones placed around the various performers. According to Kwakye, he positioned an AKG microphone (condenser) overhead for the percussion unit (congas, rattle, and bells) to capture the sonic solidity of the various percussionists as a unified group. Also, he placed another AKG microphone overhead for the drum-set to roundly capture its sound as a single entity and placed a dynamic microphone specifically for the lead vocalist who also doubled as the drummer. Additionally, Kwakye points out that he made use of a Neumann microphone (condenser) to record the wind instruments owing to its ability to boldly capture mid-based sound frequencies and similarly for the background vocals. Beyer microphones were set for the bass guitar via its combo monitor to mechanically filter out distorted low sounds owing to its dynamic range and for the lead guitar for clear tone production. In essence, Kwakye's microphone selections were guided by what he heard acoustically and how that could be best captured to resonate with the social ears of Ghanaians. Recordings around this period were highly timed with an electronic timer held steadily throughout a recording session. It controlled prolonged performances and abrupt endings owing to the limited length of tapes then.

The unique attribute that characterised the 1970s recording process was mixing the sound before the actual recording. All acoustic signals were suitably mixed per the directives of the engineer, music producer and performing musicians. Hence, a band could tell its sound during its recording process. Kwabena Kwakye Kabobo (then a session drummer) reveals that performers were usually placed within individual cubicles to avoid sound leakages and sound check was resolutely observed.Footnote 28 The available signal processor at the time was solely the mixing console's equalisation (EQ) knobs and volume faders. At the mixing stage of sikyi highlife, Kwakye notes that he typically tweaked the EQ knobs to ensure a desirable organic (lively) sound production from all audio signals before recording the Noble Kings Band. The percussions were sonically defined in terms of tone clarity to the extent to which one could hear the conga player's palm reflex on the drum vellum; a similar instance occurs for the traditional drumming settings. The brass section sounded warm and potent in resonance, distinctively different from how brass instruments sounded on earlier highlife records. Both the lead guitar and bass guitar had definite sound production emphasising the depth of their individual timbres. The organ was blended in a mellow fashion to complement the guitar. The vocals sounded clean and bold in the mix. According to Kwakye, earlier highlife songs were engineered based on the ratio 1:2, implying vocals above instrumentation, a standard set by Decca Records (Ghana) from the 1950s onwards.Footnote 29 However, he refocused the ratio to 1:1 based on his personal observations within the music-making ecology of Ghana. His reason was that Ghanaians conventionally do not draw a line between instrumentations and vocals during both traditional and popular music performances. He recounts:

From my observation as a child to adulthood, I realised that Ghanaians loved the instrumentation of a song as well as the vocals in all performance circles. Musicians occasionally tone down their performance to project a particular phrase in the lyrics of a song for artistic purposes, and not to draw back on the overall instrumental performance. You will hear an instrumentalist shout ‘down!’ to cue in an important message that needs to be heard loud and clear for a moment and not throughout the song. This is all done as part of the totality of music performance in Ghana for aesthetic purposes. So, I incorporated this mutuality in the signal balance of vocals and instrumentation into highlife productions at the studio.Footnote 30

Primarily, this became the first point of change in the sound recording of Ghanaian highlife in the 1970s. An archival study piloted at the J.H. Kwabena Nketia Archive for reports on Ghanaian music performances validates Kwakye's claim.Footnote 31 Explicitly, a video documentary entitled Africa Come Back: The Popular Music of West Africa was examined.Footnote 32 A copy of this video document is shared on YouTube by Daddy Lumba (a veteran burger highlife musician).Footnote 33 It focuses on 1970s Ghanaian popular music and its cultural roots, encompassing musical practices such as nwomkrᴐ (Akan vocal music with traditional drumming), kpanlogo (Ga dance-drumming), palmwine music and highlife music. Analysis of data gathered demonstrates the mutuality in vocal and instrumentation relation in terms of velocity levels as Kwakye observes. Hence, the instrumentations and vocals on the sikyi highlife album were blended to reflect a symbiotic signal level of 1:1 ratio. According to Kwakye, the shift in ratio aided in the projection of dance rhythmic elements in highlife music which were somewhat overlooked in earlier highlife recordings.Footnote 34 This coincides with Kheshti's (Reference Kheshti2009, p. 15) assertion that ‘aural positionality enables us to deconstruct the means by which the perspective and position of the recordist and recording equipment construct knowledge about sites and subjects’.

At the mastering stage of sikyi highlife, Kwakye rerecorded the captured audio data onto a new tape via the 2-track tape recorder and reprocessed it as mastered data. Ideally, he skilfully mixed the first track to reflect a low frequency range between 80 and 300 Hz and likewise mixed the second track to demonstrate a blend of mid and high frequency ranges around 400–14 kHz, to achieve a desirable balanced sound. Afterwards, he increased the volume of the newly mixed data to an amplitude of 10 dB. Then finally he rerecorded the mastered data onto a new tape. Thus, in the process of producing highlife music in the 1970s, we observe the use of two or more tapes. Usually, Kwakye boosted the volume of all newly mixed highlife data by an amplitude of between 5 and 15 dB depending on each song's initial state of loudness. It should be notated that this mastering approach was not a global phenomenon, but was uniquely conceived by Kwakye to ensure a desirable sonic output that could resonate with the social ears of Ghanaians at the time. Bobby Owsinski (Reference Owsinski2008, p. 3) posits that ‘mastering is, quite simply, the intermediate step between taking the audio fresh from mixdown from a studio and preparing it to be replicated or distributed’. Accordingly, the mastered sikyi highlife data was pressed onto vinyl 33 rpm records (long-play) at the Record Manufacturers (Ghana) Limited. This company was partly owned by the Polygram Company and a Ghanaian music producer named Dick Essilfie Bondzie (Essiebons).Footnote 35 The album was marketed and distributed by the Essiebons label under the code EBL 6117.

Essentially, most highlife recordings made during the early-to-mid 1970s were engineered around the above production parameters. However, this recording method significantly improved when GFS acquired an 8-track Revox stereo tape recorder around the late 1970s. At this point, a frequency range covering 50 Hz to 15 kHz could be ensured through a similar process involving three tracks or more. Explicitly, the first track (low frequency, 50 Hz to 200 Hz), the second track (mid frequency, 300–900 Hz) and the third track (high frequency, 1–15 kHz) blended together in a mono format.Footnote 36 Although GFS had acquired the new 8-track stereo recorder, Kwakye did not routinely produce a stereo record until the 1980s. This was because the Ghana Broadcasting CorporationFootnote 37 in the 1970s aired songs in a mono signal. Also, the majority of Ghanaians then owned mono-bussed media players such as record players and portable radio players commonly labelled as ‘wireless’. It must be emphasised that speaker technology then could only reproduce sound around the aforementioned frequency chart. Other prominent works recorded by the GFS in the 1970s include 4th Dimension Dance Band's ‘Yɛde nam pa aba’ recorded in 1973, Uhuru Dance Band's ‘Ͻdͻ te sɛ bump’, Eddie Donkor's ‘Asiko Darling’, C.K. Mann's ‘Funky Highlife’, Kwamena Ray Ellis's ‘Keyboard Africa (Highlife ‘N’ Piano)’ and The Ogyatanaa Show Band's ‘Yɛrefrɛfrɛ’, both recorded in 1975. In addition, Alex Konadu's ‘Asaase Asa’ was recorded in 1976, Ebo Taylor's ‘Ͻhyɛ atar gyan’, Alhaji K. Frimpong's ‘Hwehwɛ mu na yi won pena’ were all recorded in 1977, and there were numerous others.

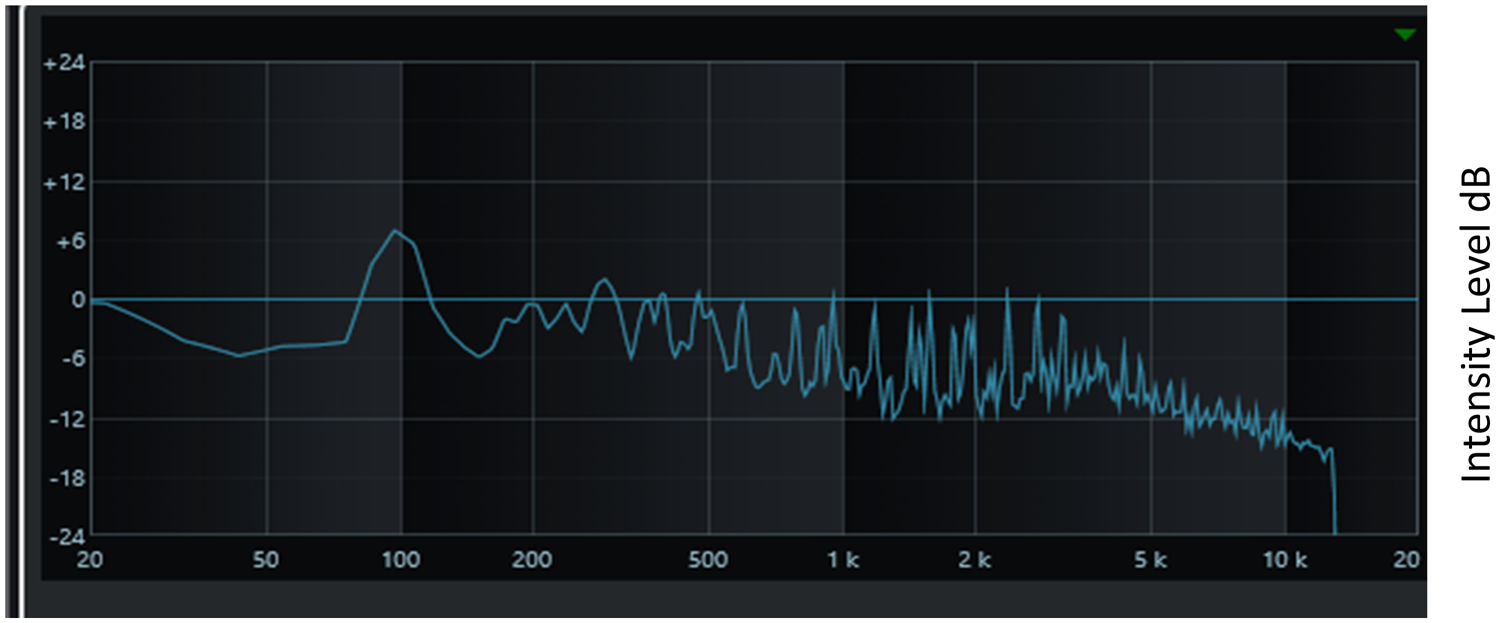

A spectral graph of sikyi highlife was deduced through a spectrum analyser found in the Wavelab virtual mastering sequencer. This was done to illustrate frequency chart and its limitations during highlife sound recordings in the 1970s. The experimentation was conducted at the Sawnd Factory Studio located at Lapaz, Accra (Ghana), involving the author and Samuel B. Agyeman (resident engineer, musician, and scholar; see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Spectrum analysis of the sikyi highlife mastered audio.

Even though Figure 1 shows a frequency range of 20 Hz to 20 kHz owing to technological advancement, 1970s highlife songs were generally recorded and mastered between 80 Hz and 14 kHz. Per the chart above, the low frequency intensity is around 80–300 Hz, the mid frequency begins around 400 Hz to 4 kHz and the high frequency is around 5–14 kHz. Therefore, the tripartite sound model (low, mid and high) that is crucial to the social ears of Ghanaians was duly captured and represented by Kwakye during the sikyi highlife recording process. Principally, the excitement that low-end sounds produced for Ghanaians both in traditional and popular entertainment circles, informs why he dedicated the tape recorder's first track to the mastering of low-end sounds (bass guitar and kick drum). Similarly, knowing the social sentiments expressed towards mid- and high-ranged sounds influenced his decision to treat the second track as mid and high sound frequencies within a wider range of 400 Hz to 14 kHz. This was done to enhance the timbral depth of dance rhythmic instruments such as congas, drum-set, bells, rattle, electric guitar, brass section and vocals, among others. These sonic experimentations, however, became flexible during the late 1970s as the 8-track tape machine allowed the dedication of separate tracks to each frequency range: low-end (track 1), mid-end (track 2) and high-end (track 3), which was further explored in the 1980s.

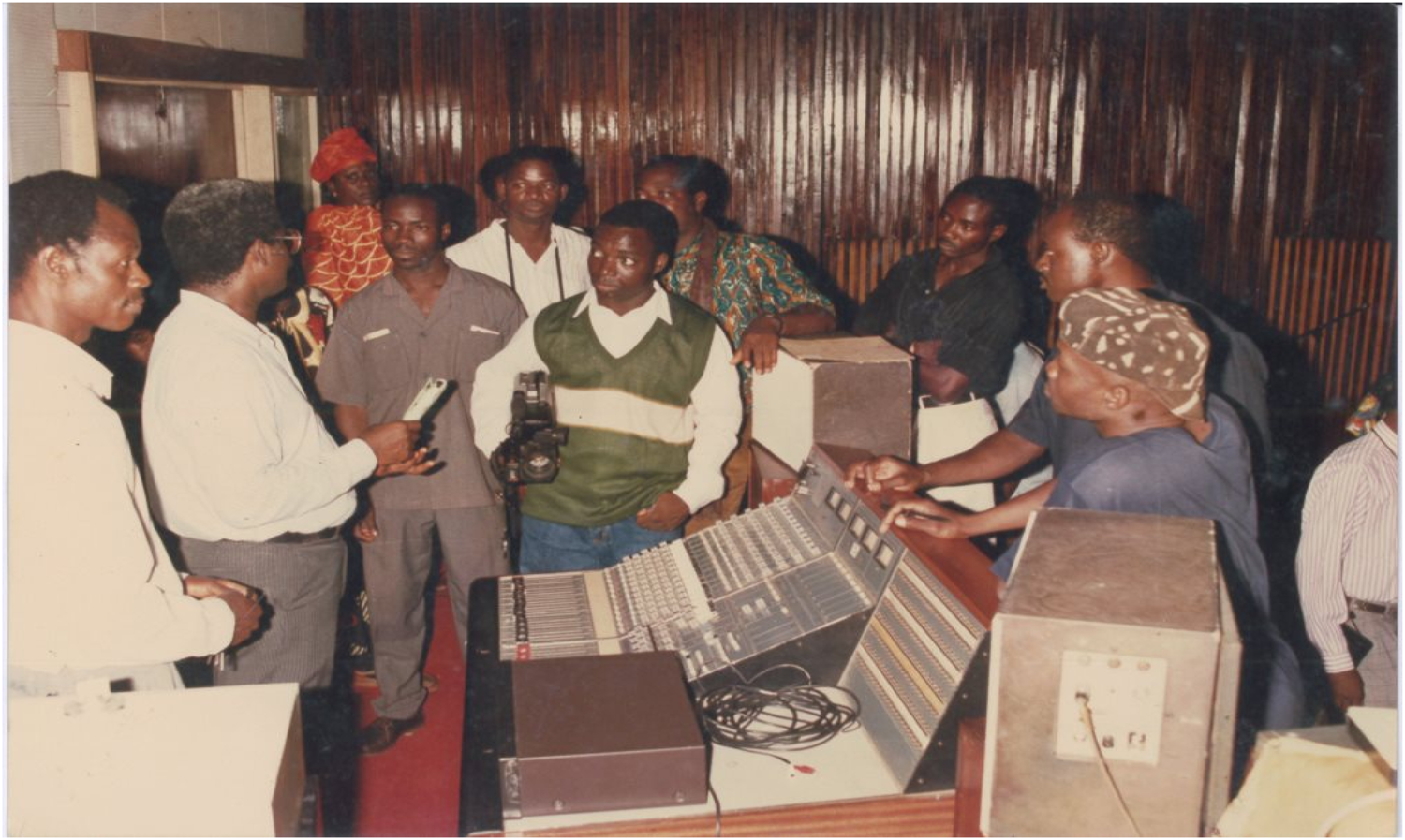

It is worth mentioning that by the mid-1970s, Kwakye was operating as the Head of GFIC's Sound Department (see Figure 2). Hence, in 1979, he recruited John Kofi Archer and Kwadwo Andoh into the corporation as sound assistants. John Archer and Kwadwo Andoh were Kwakye's former students at a training school called Radio Servicing Training School, located in Kumasi around the mid-1960s. Kwakye had his electrical engineering basis at that school and afterwards was employed as an instructor for three years until his appointment with GFIC in 1969.

Figure 2. Francis Kwakye (immediate left) and other GFIC employees in a departmental meeting around the late 1970s (photo courtesy Francis Kwakye)

Conclusion

Kheshti (Reference Kheshti2009, p. 15) asserts that ‘problematizing the positionality from which sound recordings are produced, and the aural perspectives that recordings attempt to elicit, enables us to ask: what kind of sonorous body is being materialized through these production techniques and what kind of listener is being produced through these representational practices?’ She said this in an attempt to emphasise the importance of ecological considerations in sound recording and she coined the term ‘acoustigraphy’ (a merger of ‘acoustic’ and ‘ethnography’) to explain the cultural acoustics at specific locations in San Francisco, USA. Similarly, Owsinski (Reference Owsinski2006) opines that sound crafting methods vary geographically based on his study of popular music sound representations within specific cities such as Los Angeles, New York and London. He states:

Where you live has a great influence on the sound of your mix. Up until the late 80s or so, it was easy to tell where a record was made, just by its sound. (Owsinski 2006, p. 3)

This proposes that sound recording extends beyond the scientific notion of sound as physics towards acoustic ecological factors (sound and society rapport). Locally, ecological considerations in sound recording started with Francis Kwakye, an allusion notable in the Ghanaian recording industry beyond all doubts. As the leading recording engineer of 1970s highlife music, his approach to sound recording was steered by personal experiences within the music-making ecology and soundscape of urban Accra and Kumasi (Ghana). His recording methods were guided by societal perceptions, expectations and sentiments. It is proposed that it was not only what highlife bands played at the studio that determined their sounds on records but also Kwakye's socio-cultural interpretation of what was being played that suggested the eventual sound output of recorded products. The paper concludes that sound recording is not dependent on only scientific notions of sound as physics but also the socio-cultural context within which the sound is been crafted. Hence, if people keep on imagining and creating relatively new sounds in contemporary sound recording praxis, I argue that this will also influence and explain how and why they wish to be perceived.