No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

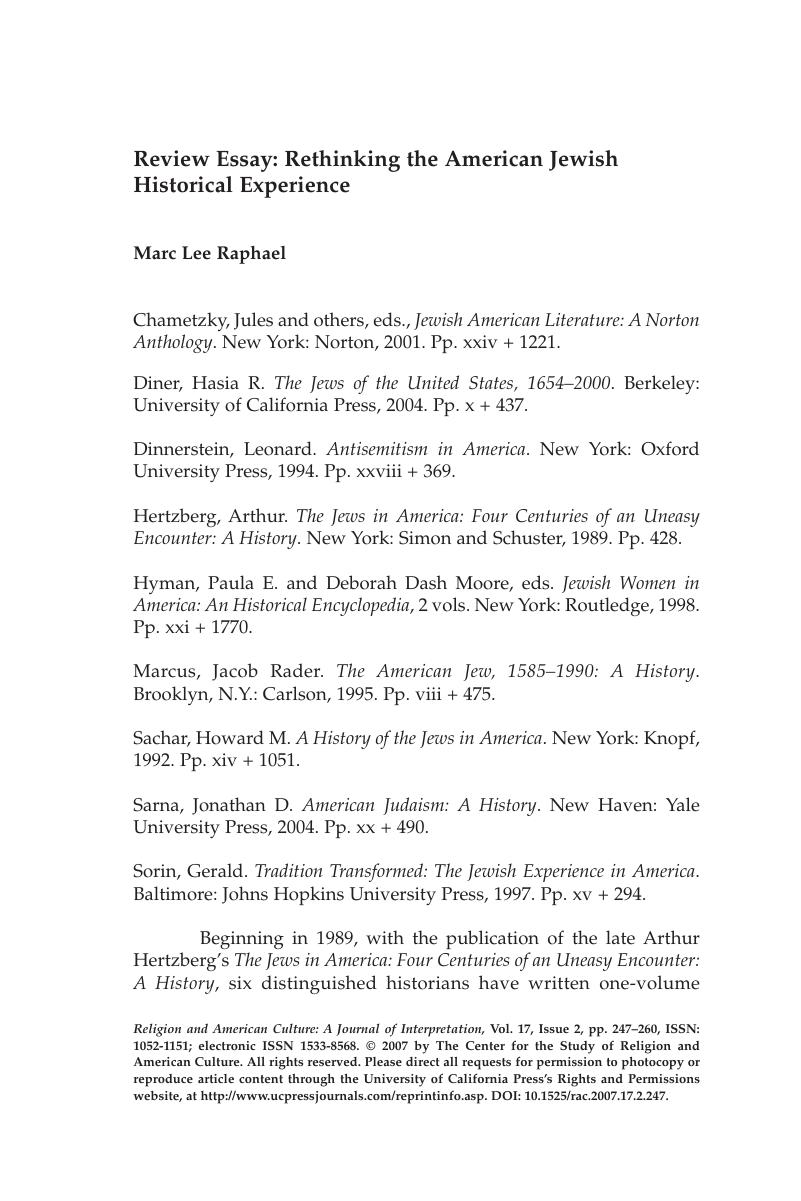

Review Essay: Rethinking the American Jewish Historical Experience

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 June 2018

Abstract

- Type

- Review Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Center for the Study of Religion and American Culture 2007

References

Notes

I am grateful to Professor Pamela Nadell for helping me both conceptualize and execute this essay.

1. There is a seventh volume, Karp, Abraham J., A History of the Jews in America(Norvale, N.J.: Aronson, 1997 Google Scholar), but it is actually a reprint of Karp's earlier Haven and Home: A History of the Jews in America (New York: Schocken Books, 1985).

2. Wiernik, Peter, History of the Jews in America: From the Period of Discovery of the New World to the Present Time (New York: Jewish Press, 1912 Google Scholar; rev. and expanded, New York: Jewish History Publishing, 1931; 3d edition, New York: Hermon Press, 1972); Levinger, Lee J., A History of the Jews in the United States (Cincinnati: Dept. of Synagogue and School Extension of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, 1930 Google Scholar; 20th rev. ed., New York: Union of American Hebrew Congregations, 1961); Handlin, Oscar, Adventure in Freedom: Three Hundred Years of Jewish Life in America (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1954 Google Scholar; repr., Port Washington, N.Y.: Kennikat Press, 1971); Learsi, Rufus, The Jews in America: A History (Cleveland: World Publishing, 1954 Google Scholar; with an epilogue by Abraham J. Karp, New York: KTAV, 1972); Feingold, Henry L., Zion in America: The Jewish Experience from Colonial Times to the Present (New York: Twayne, 1974 Google Scholar; rev. ed., New York: Hippocrene Books, 1981).

3. Levinger, A History of the Jews in the United States (3d rev. ed., Cincinnati: Dept. of Synagogue and School Extension of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, 1944), ix.

4. Marcus, Jacob Rader, “The Periodization of American Jewish History,” Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society 47, no. 3 (March 1958): 125–33;Google Scholar Levinger, History of the Jews in the United States, 3d rev. ed., 12, 13; Wiernik, History of the Jews in America, 3d ed., xiii–xxiii.

5. For example, see Handlin, Adventure in Freedom (1954), 35–50 and 80–85; and Feingold, Zion in America, rev. ed., chaps. 5 and 8.

6. More precisely, the term secular Jew was used in the early part of the twentieth century, the term cultural Jew in the past few decades. The latter (usually) describes someone who makes Jewish film festivals, or klezmer concerts, or Jewish food, or Jewish fiction, or a politically progressive Jewish ideology their main form of identification as Jews.

7. Sarna's prejudices are everywhere. He detests the Philip Roth of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s (Portnoy's Complaint is “not a very good book” and his subsequent fiction is dismissed in one sentence [780]); he has little but invective for what he labels the “Holocaust industry” and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (“staff of Americans and imported Israelis whose salaries at the upper echelons matched those of corporation executives” [847]); but he celebrates Jewish gangsters and is extremely fond of Brandeis University's first president, his father Abram L. Sarna, who “hurled himself into the Brandeis challenge with ferocious energy” (711).

8. Feingold, , Zion in America, rev. ed., 182 Google Scholar.

9. Levinger, , A History of the Jews in the United States, 20th rev. ed., 388 Google Scholar; Feingold, Zion in America, rev. ed., 278. Feingold uncritically accepts the naïve conclusions of Uriah Zvi Engelman in “Jewish Statistics in the U.S. Census of Religious Bodies (1850–1936),” Jewish Social Studies 9, no. 2 (April 1947): 127–74. Engelman cites the 3,118 figure from 1926 (and plenty of other fundamentally unsound figures) on page 162.

11. When a Catholic bishop recently (June 2006) gave a talk in Washington, D.C., on the disparity between Catholic doctrine and the position taken by Catholic elected officials in the House and Senate, one person in the audience asked the bishop how he defines a “Catholic” politician and whether he is counting “lapsed Catholics” in his (seemingly) exaggerated figure. The parallel is obvious.

13. I first wrote about national vs. local organizations in Raphael, Marc Lee, “The Maturing of American Jewish Historiography,” Reviews in American History 1, no. 3 (September 1973): 336–42CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

14. Feingold, Zion in America, rev. ed., 267–76, 269.

15. Raphael, Marc Lee, Judaism in America (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 153ffGoogle Scholar.

16. All the references in this paragraph are from Whitfield, Stephen J., In Search of American Jewish Culture (Hanover, N.H.: Brandeis University Press, 1999 CrossRefGoogle Scholar).

17. He also draws upon their data, when useful. One example is his use of the 1988 Dartmouth survey Hertzberg used (see above in text), first published by Hertzberg in the New York Review of Books, November 23, 1989, 26.

18. Lang, Berel, “Hyphenated-Jews and the Anxiety of Identity,” Jewish Social Studies 12, no. 1 (Fall 2005): 1–15 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.