Introduction

Recent research has documented the extent to which global governance institutions (GGIs) have ‘opened up’ to non-state participation.Footnote 1 Alongside the ‘opening up’ of formal inter-governmental organisations, we can also observe the proliferation of multistakeholder partnerships (MSPs) across virtually all domains of global governance: highly inclusive governance forms that feature non-state actors (NSAs) as core ‘governors’ alongside states.Footnote 2

Research on NSA participation and GGI openness has examined several aspects of this phenomenon. First, various quantitative studies have documented the extent of formal openness across global governance.Footnote 3 These approaches affirm and provide clear evidence of more inclusive governance forms. Second, several studies have addressed the drivers underlying greater NSA participation within GGIs. These include, inter alia, efforts to uncover how NGO participation is shaped by incentives at global and national levels, broader trends towards informality that enable greater non-state participation, and the principles and ethics that drive transnational activism.Footnote 4 Third, a related set of literature has examined the actual patterns of NSA participation. Uhre, for instance, provides insight into the diversity of transnational actors within global environmental governance, while Hanegraaff et al. reveal that – in global climate governance – a considerable degree of NSA participation is of an incidental nature: many NSAs attend global conferences once but do not return.Footnote 5 A fourth set of literature has sought to examine the consequences of NSA participation within and for GGIs. Scholars have long affirmed that affording greater access to NSAs can provide GGIs with more accountability, expertise, legitimacy, and effectiveness.Footnote 6 Subsequent studies have sought to explore whether and how different formal patterns of access and participation have impacted upon the authority, legitimacy, and effectiveness of GGIs.Footnote 7

We build upon these approaches that explore the extent, drivers, patterns, and consequences of the increased openness of GGIs by providing a framework that enables us to assess the quality of inclusion. We contend that while the formal openness (and measurement thereof) of GGIs has expanded, the actual—and experienced—quality of actor participation remains underexplored. While recognising several small-N and qualitative studies that have investigated the challenges associated with ‘inclusive’ governance in practice, we reflect on the notion of ‘meaningful inclusion’.Footnote 8 Such, we contend, broadly refers to the effective participation of relevant stakeholders, characterised by equitable access, sustained participation, and genuine influence in agenda setting and/or decision-making processes. This goes beyond mere formal access to include the empowerment of diverse actors, ensuring that their contributions shape governance without being co-opted by dominant interests. Ultimately, we are concerned with a ‘sociological’ conception of meaningful inclusion: that is, how stakeholders themselves evaluate the experienced quality of inclusion in concrete institutional settings. To enable empirical explorations, we develop a heuristic framework that distinguishes between the de jure and de facto inclusivity of GGIs, encompassing components that focus on stakeholder legitimacy and the dynamics of stakeholder engagement.

Through an abductive approach, we develop and apply our framework by examining the Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation (GPEDC), what some describe as a ‘uniquely inclusive’ multistakeholder development partnership.Footnote 9 In the global development context, the GPEDC seems to offer a commendable structure of inclusive governance because it formally recognises non-state actors as decision-makers at the highest political level on par with states while ensuring Southern state parity in its governance. This contrasts with the exclusive, Northern donor-focused model of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) at the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and development partnerships at the United Nations (UN), which, despite providing space for non-state actors, still adhere to state-based decision-making principles. Building on extensive ‘insider’ participant observations between 2013 and 2022, 97 interviews with key state and non-state representatives, and a comprehensive review of organisational and grey literature, we explore the inclusive quality of this initiative. We find that although the GPEDC has made exemplary progress in ensuring de jure inclusiveness, it faces intractable shortcomings across its de facto dimensions. While our intention is not to provide generalisations across global governance writ large, we contend that realising de facto inclusivity – and hence meaningful inclusion – is elusive in a world marred by stark capacity differentials. Although this does not negate efforts to improve the inclusive quality (whether de jure or de facto) of global governance, it does temper declarations on the supposed inclusive quality of GGIs in the 21st century. Our framework provides a systematic approach to evaluating such.

We first examine existing work on the inclusive quality of GGIs and then provide the rationale and components of our framework. The subsequent section illustrates how this framework can be used to assess inclusivity dynamics within the context of the GPEDC. The final section discusses these findings and concludes.

Unpacking stakeholder inclusion

Attempts to assess the inclusive quality of GGIs have been closely linked to long-standing normative concerns surrounding the so-called ‘democratic deficit’ facing global governance.Footnote 10 Enhanced representation of developing countries and NSAs within GGIs reflects moral imperatives that recognise individuals’ and collectives’ inherent rights to partake in decisions impacting them.Footnote 11 As Scholte highlights, ‘it is to the intrinsic good of human dignity that people should have a say in the politics that shape their lives, including through global governance’.Footnote 12 Stevenson argues that greater inclusivity has instrumental value: such can enable those involved to tap into diverse expertise and perspectives, leading to better outcomes.Footnote 13 Given these arguments supporting increased inclusivity, various approaches have been developed to evaluate GGIs’ inclusiveness.

First, scholars have made significant strides in providing empirical evidence for assessing the formal openness of GGIs. Tallberg et al. provide quantitative data demonstrating that international organisations (IOs) are undergoing a ‘profound institutional transformation … dramatically expanding the opportunities for transnational actors to participate in global policymaking’.Footnote 14 Historically, as Liese has noted, formal NSA representation in IO decision-making bodies was rare.Footnote 15 Yet quantitative evidence on the rise of ‘transnational’ or ‘multistakeholder’ partnerships suggests that NSAs now frequently enjoy formal access.Footnote 16 However, Tallberg at al. caution that the tendency to ‘exclusively focus on formal access [may] underestimate this change’ towards greater NSA access, ‘because many IOs offer informal mechanisms of access as well’.Footnote 17

Second, the evaluation of GGIs’ inclusiveness often features as a subsidiary element within legitimacy analyses, which typically frame ‘inclusion’ alongside ‘transparency’ and ‘procedural fairness’ as parts of ‘input legitimacy’.Footnote 18 However, these studies tend to focus on formal aspects of inclusion, potentially neglecting the varied perspectives that stakeholders hold about inclusivity and the practical challenges in its implementation. Moreover, Jongen and Scholte have recently observed that the relationship between formal stakeholder inclusion and overall legitimacy beliefs is not always statistically significant.Footnote 19 Furthermore, Schmidt highlights that inclusiveness can be understood as a key ‘cross-cutting dimension not only in terms of “input legitimacy” (the question of “who governs”), but also in terms of the inclusiveness of how governance is carried out’ (throughput).Footnote 20 Such insights complicate the view that inclusivity can be merely subsumed as a sub-component of legitimacy.

A third set of disaggregated literature provides insight into the challenges of achieving inclusive governance in practice. Critical scholars have long raised concerns that inclusivity discourses can serve to co-opt NSAs into legitimising neoliberal global governance, potentially undermining multilateral regulatory efforts.Footnote 21 Additionally, Cooke and Kothari critique participatory discourses as a ‘new tyranny’, pointing out discrepancies between formal participatory provisions and their practical implementation, which often perpetuates existing power imbalances and co-opts dissenting voices.Footnote 22 Recent scholarship has also cautioned against the ascent of multistakeholderism, which potentially contributes towards corporate dominance in global governance.Footnote 23 Mattli and Woods highlight that global regulatory bodies are particularly susceptible to special interest capture, noting that the necessary ‘capacity to participate meaningfully in global regulation are not evenly distributed’ across countries and NSAs.Footnote 24 They contend that:

Stark asymmetries in information, financial resources, and technical expertise among groups … create conditions conductive to regulatory capture even in an institutional context offering extensive formal due process and [de jure] access … [privileging] narrower interests (the ‘haves’) at the expense of broader interests (the ‘have-nots’).

Research on NSA inclusion in GGIs highlights the challenges surrounding the inclusion of traditionally excluded actors. Fisher and Green discuss how developing states and NSAs are often ‘deprived’ of the ability to influence international agendas and decision-making structures.Footnote 25 Tallberg and Uhlin note that transnational corporations and well-funded NGOs generally enjoy greater access and influence, while marginalised groups from developing countries remain underrepresented in GGIs.Footnote 26 Dingwerth observes low participation by Southern stakeholders in private transnational governance schemes and suggests that formal affirmative procedures are insufficient for ensuring meaningful representation.Footnote 27 Echoing this, he subsequently argues that to enhance inclusivity for disenfranchised civic actors and developing states, the focus should shift from merely increasing formal access to addressing underlying inequalities and structural barriers.Footnote 28 Building on these insights, Nanz and Dingwerth argue that the ‘opening up’ of GGIs transfers ‘political struggles over representation rights’ to the international realm and affirm the need for deeper scrutiny into the politics of participation as a significant aspect of international political life.Footnote 29

These studies collectively reveal a gap between formal inclusivity provisions and the practical challenges of achieving more inclusive governance.Footnote 30 We can thus conceive meaningful inclusion as requiring more than just formal provisions; it involves effective participation of relevant stakeholders, characterised by equitable access, sustained involvement, and genuine influence. Further, meaningful inclusion transcends superficial or ‘checkbox’ approaches – what Mehta and Seim describe as ‘half-hearted efforts that serve to tokenize rather than fully include a diverse set of perspectives’.Footnote 31 Meaningful inclusion requires that stakeholders can influence governance processes without being co-opted by dominant actors. While this concept helps us conceptualise what meaningful inclusion might entail, its ‘meaningfulness’ ultimately hinges on stakeholders’ actual experiences and perceptions of inclusion. Consequently, we adopt a ‘sociological’ approach that ‘combines the normative and empirical’ to engage with actor perceptions, identifying concepts that are normatively informed ‘but serve at the same time as useful categories for empirical investigation’.Footnote 32

We also leverage insights from legal studies and across the social sciences to distinguish between de jure and de facto dimensions.Footnote 33 This general distinction enables exploration into discrepancies between formal frameworks and their practical applications, as seen in various contexts: the coexistence of economic institutions and legal changes, formal versus informal rules in global organisations, and the gap between the formal and actual policy autonomy of IOs.Footnote 34 Dudzich also examines the mix of fixed and floating elements in exchange rate systems, while Lindberg et al. discuss the divide between the establishment of de jure accountability regimes and their practical enforcement.Footnote 35 Moreover, Peksen and Pollock use this distinction to analyse labour rights under globalisation.Footnote 36

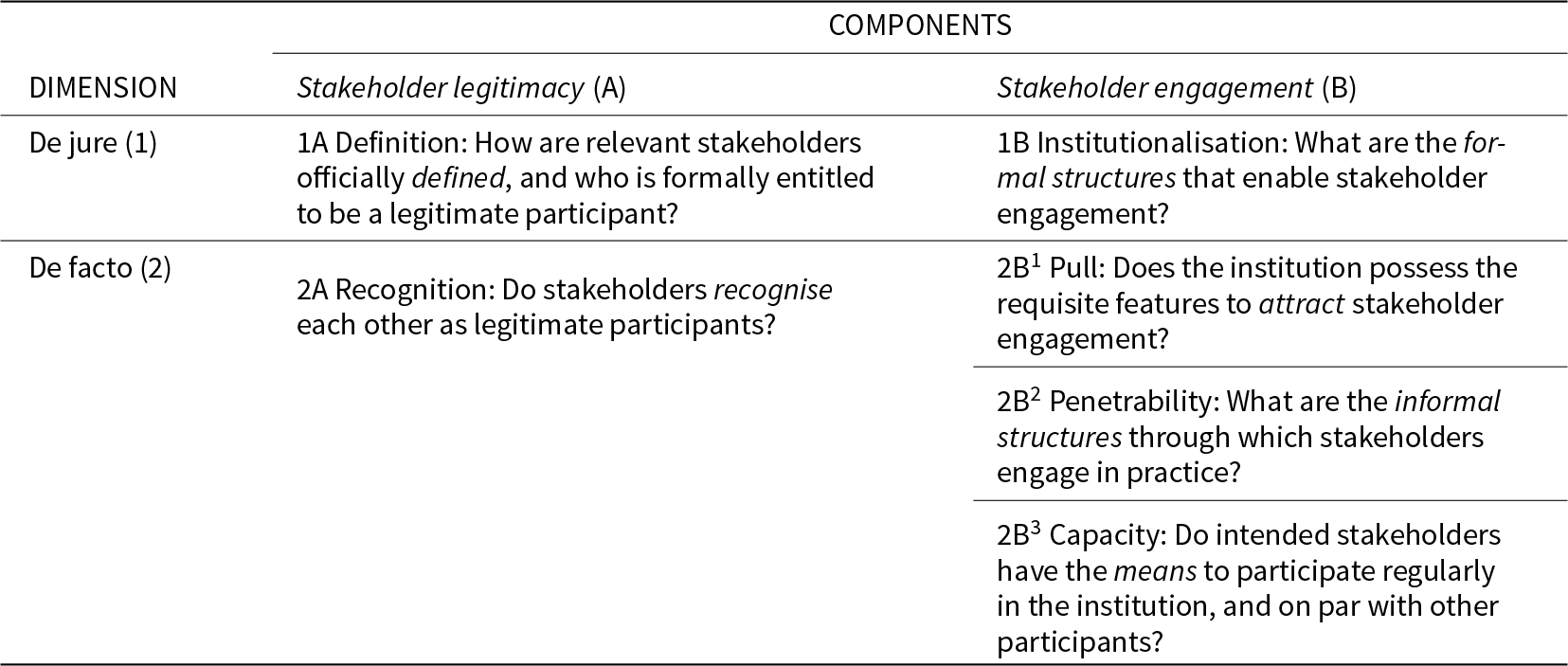

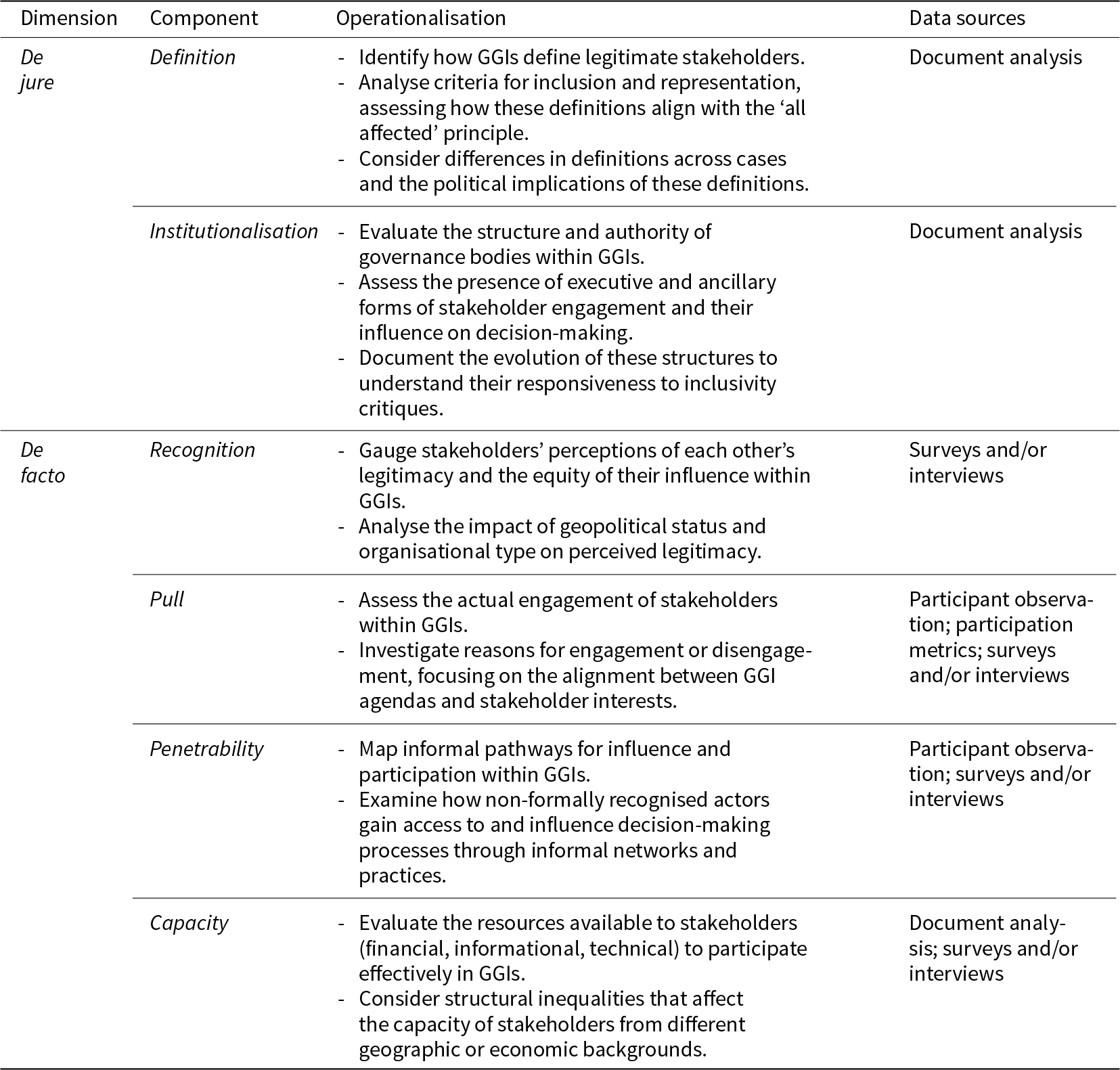

While the de jure/de facto distinction is widely employed across the social sciences, it has not been applied to the inclusiveness of GGIs. Our framework (Table 1) distinguishes between the de jure and de facto dimensions of stakeholder legitimacy and engagement, identifies sub-components, and considers their impact upon the inclusiveness of GGIs. Each component’s conceptual basis and contribution towards inclusivity as well as related insights from existing literature and proposed strategies for operationalisation (see Table 2) are detailed below.

Table 1. Stakeholder inclusivity in global governance.

Table 2. Operationalising the de jure/de facto inclusivity framework.

De jure inclusivity

De jure inclusivity concerns the formal procedures and structures that facilitate stakeholder participation. We foreground two components: the official definitions of legitimate stakeholders (definition) and the formal structures that enable stakeholder engagement (institutionalisation).

1A Definition

Defining who qualifies as a stakeholder is crucial for ensuring formal inclusivity within GGIs. Dingwerth argues that ‘defining stakeholder categories is the most fundamental task of any multistakeholder process’.Footnote 37 This component draws upon the ‘all affected’ principle of democratic governance: that anyone affected by a decision ought to be involved in governance, either directly or through representation.Footnote 38 This principle is embedded in international institutions such as the World Bank’s Inspection Panel and the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), affirming its influence on global development policy.Footnote 39

However, accurately identifying stakeholders is complex and fraught with political challenges. Dingwerth notes that standard classifications – such as public actors, businesses, and civil society – often obscure significant internal differences, complicating the process of stakeholder identification and representation.Footnote 40 Moreover, the creation of these categories can be arbitrary, influenced by existing power structures and the lack of a clear, global demos.Footnote 41

To operationalise the definition component, we propose examining how GGIs define stakeholders in their founding documents and governance practices. This invites comparative exploration into how the global ‘South’ is defined, for instance, how the amorphous ‘private sector’ is represented at the global level, and how designers of GGIs seek to bridge the ‘global–local’ gap in stakeholder representation.Footnote 42 This analysis can be extended towards assessments of whether these definitions adhere to the principle of ‘all affectedness’. Furthermore, in keeping with a sociological approach, this component also invites investigation into whether stakeholders regard such definitions as accurately capturing and allowing for meaningful representation.

1B Institutionalisation

Institutionalisation refers to the formal structures within GGIs that enable and facilitate stakeholder engagement based on previously agreed definitions. This marks a significant shift from traditional interstate governance frameworks, which usually limit NSAs to consultative roles. Contemporary multistakeholder frameworks instead provide NSAs with more substantial and varied forms of engagement. Scholte distinguishes between ‘executive’ forms of engagement, where NSAs possess decision-making authority on par with states, and ‘ancillary’ forms, where NSAs participate in traditional state-based multilateral settings without equal power.Footnote 43

The way GGIs institutionalise stakeholder engagement directly impacts the inclusiveness and depth of participation. Formal structures are crucial in defining how NSAs can (not) interact with governance processes, and their design often reflects the extent of a GGI’s commitment to inclusivity. Despite the critical role of these structures, much about their operation remains poorly understood.Footnote 44 Common elements such as boards, consultative groups, and secretariats do exist across many MSPs, but representation within these structures can vary significantly, influencing the distribution of decision-making power and potentially granting disproportionate influence to already dominant stakeholder groups.Footnote 45

The institutionalisation component can be operationalised in various ways. It primarily requires the analysis of the formal roles and powers of boards or consultative groups but also invites examination into stakeholder perspectives on whether formal structures are viewed as ‘fit for purpose’ towards enabling effective participation. Moreover, understanding how these governance structures have evolved over time can yield important insights. Initial design stages often reveal conflicts of interest and power struggles that can fundamentally influence the effectiveness and inclusivity of the institutional framework.Footnote 46 Furthermore, and in keeping with the insight from Avant et al. that ‘nothing is ever governed once and for all’, a longitudinal study of these structures can reveal how adaptations and reforms have impacted the inclusivity of de jure governance arrangements over time.Footnote 47

De facto inclusivity

De facto inclusivity refers to the perceived quality of inclusion in practice, enabling assessments on ‘who actually governs’ within GGIs.Footnote 48 The de facto counterpart to formal definition is recognition, reflecting actual acknowledgement of stakeholders. Beyond this, the de facto dimension of stakeholder engagement – paralleling formal institutionalisation – incorporates informal dynamics that influence engagement. To address this, we differentiate among three key components: an institution’s pull, its penetrability, and stakeholder capacity. We detail each in turn.

2A Recognition

Effective recognition evaluates whether stakeholders are acknowledged as legitimate participants in practice, beyond formal entitlements. Fisher and Green affirm the importance of mutual recognition among governance peers, stating that ‘effective participation in international policymaking requires more than legal recognition’.Footnote 49 While states typically enjoy recognition due to their sovereign status in interstate multilateralism, the legitimacy of NSAs in GGIs is often ambiguous and requires ongoing validation.

Despite formal participation mechanisms, NSAs frequently face barriers that undermine their influence and perceived legitimacy, often being relegated to subordinate roles. For example, civic actors in the Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa (BRICS) grouping have formal engagement platforms but often have limited impact in development dialogues.Footnote 50 Additionally, many civic actors report that their participation in GGIs is tokenistic and not afforded the same weight as other stakeholders.Footnote 51 Furthermore, Buxton argues that the pursuit of greater inclusion and ‘democratisation’ via MSPs facilitates the ‘privatisation’ of global governance, with private sector entities afforded more dominant positions than some public or civic actors.Footnote 52 Actor-type disparities are also exacerbated by the geopolitical status of stakeholders’ parent countries, resulting in the voice of some NSAs being afforded greater weight than others.Footnote 53

Operationalising the recognition component involves examining not only the types of actors included in governance, but also the ‘character of relationships’ and perceptions among them.Footnote 54 Through interviews and observations, this analysis can reveal whether stakeholders view each other as equals and identify any disparities in perceived legitimacy. Perceptions of fellow stakeholders as (il)legitimate and/or (un)equal are vital as they significantly influence the perceived quality of inclusion beyond formal participation rights. Additionally, analysing how organisational forms and the geopolitical status of stakeholders influence recognition provides deeper insights into the systemic biases that affect stakeholder legitimacy.

2B1 Pull

Contemporary global governance is characterised by significant institutional fragmentation and a competitive environment where multilateral and transnational organisations vie for political attention, a scenario often termed ‘contested multilateralism’.Footnote 55 This competition affects the effectiveness of formal participation mechanisms in ensuring genuine and sustained stakeholder engagement.

The concept of institutional ‘pull’, akin to ‘soft power’, refers to a GGI’s ability to attract and maintain the engagement of relevant stakeholders.Footnote 56 Effective inclusion in practice is compromised if a GGI, despite its formal inclusivity, only garners limited or superficial participation, whether sporadic or lacking representation from key groups. Institutional ‘pull’ thus assesses whether GGIs are perceived as relevant and effective platforms for engagement. The notion of ‘fitness’ in governance, encompassing both institutional and social aspects, is critical here: it explores the alignment of an institution’s structure and goals with the preferences, values, and needs of its stakeholders.Footnote 57

Operationalising the pull component entails examining stakeholders’ perceptions of the relevance and efficacy of GGIs. This includes assessing whether stakeholders view these institutions as suitable venues that effectively address issues pertinent to their interests and needs. Despite formal invitations to participate, a GGI might only attract limited engagement if it fails to align well with the preferences and requirements of its stakeholders. Investigating why stakeholders may ‘opt out’ provides insights into the institutional barriers and motivational factors that affect engagement.

2B2 Penetrability

Penetrability refers to stakeholders’ ability to navigate, influence, or gain access to GGIs beyond formal, institutionalised arrangements. Tallberg et al. argue that studies focusing solely on de jure procedures tend to underestimate the extent of informal non-state access across GGIs.Footnote 58 In fact, there are diverse avenues through which influence can be exerted within GGIs. In instances where specific actors are excluded from de jure set-ups, informal structures often provide crucial pathways for gaining insights and influencing those with formal authority. Fisher and Green note that civic actors, not sanctioned by official rules of international policymaking, frequently rely on ad hoc or informal tactics to impact policy decisions.Footnote 59 This dynamic is evident in various layers of the UN, where the relationship and dynamics between member states, the international bureaucracy, and NSAs highlights the significant role of informal interactions in shaping policy outcomes.Footnote 60

Informal pathways are not merely supplementary; they can be integral to the functionality of formalised partnership structures, such as NGOs accredited to the UN Economic and Social Council.Footnote 61 Informal interactions, including coffee-break chats and off-the-record meetings, often facilitate exchanges among stakeholders that prove more impactful than formal meetings.Footnote 62 These networks enable certain agents, such as issue-specific lobby groups, to exert influence that is usually restricted in more structured settings.

Operationalising the penetrability component entails mapping the informal entry points available to stakeholders.Footnote 63 This process involves both analysing visible informal channels within GGIs and uncovering the more covert and subtle strategies stakeholders employ to influence governance. An examination of documented, observed, and reported evidence of informal engagement can provide a deeper insight into how marginalised groups use these channels to either complement or compensate for formal exclusion.

2B3 Capacity

Our final component concerns the capacity of stakeholders to engage consistently and effectively with GGIs. As Guastaferro and Moschella argue, effective inclusion is not attained when only those who have the organisational structures and financial wherewithal are able to do so.Footnote 64 Proponents of resource dependence theory emphasise that non-state, especially civic, actors need substantial financial, human, and technical resources not just for maintenance but for sustained GGI engagement.Footnote 65 Yet the resources required for ‘effective interest representation in global governance … are generally only available to well-endowed organisations residing in the more privileged parts of the world’.Footnote 66

Capacity differentials are rooted in structural inequalities across class, gender, sectoral, and geographical lines, with North–South hierarchies being especially pronounced in international development.Footnote 67 For instance, Southern stakeholders often face resource and personnel constraints, further stretched by the demands of GGIs.Footnote 68 Brugha et al. highlight how the capacity of developing countries can be overstretched, impeding their effective participation in transnational partnerships.Footnote 69

Operationalising the capacity component of our framework requires examining whether stakeholders have the necessary resources to participate on an equal footing with more privileged entities. This examination should assess the resources available to stakeholders, including their financial, human, and technical capabilities.Footnote 70 The investigation should also consider the impact of these resources on participation levels and their ability to influence GGI proceedings. Understanding these capacity differentials is crucial for identifying systemic barriers that inhibit meaningful engagement.

Relationship between de jure and de facto dimensions

The de jure/de facto framework outlined above facilitates a systematic assessment of inclusivity dynamics in GGIs. Combining a focus on formal inclusivity provisions with an in-depth examination of stakeholder perceptions and the actual experience of inclusion, it contributes to unpacking what constitutes ‘meaningful’ inclusivity in global governance. The relationship between de jure and de facto dimensions, however, is complex and resists simple classification.

De jure inclusivity often sets the groundwork for de facto inclusion. For example, the establishment of the ‘NGO-World Bank committee’in 1982 paved the way for the acknowledgement of NSAs as legitimate stakeholders, progressively altering the institution’s culture and leading to enhanced engagement in practice.Footnote 71 Early involvement of NGOs and the private sector in global health governance also promoted the formalisation of their roles within the World Health Organization.

Conversely, the relationship between de jure and de facto inclusivity is not necessarily complementary. Slaughter and LaForge suggest that ‘formal inclusion often means informal exclusion: when nothing gets done in the meeting, lots of action takes place among smaller groups in the lobby’.Footnote 72 Highly de jure inclusive processes can lead to inaction, and often stakeholder groups may rely upon more informal mechanisms of (de facto) penetrability to realise governance goals. Further, the effective implementation of de jure inclusivity is often hampered by structural inequalities, diminishing the intended impact of formal mechanisms, thereby highlighting why de jure inclusivity is usually not a sufficient condition for achieving meaningful inclusion. The tripartite structure of the International Labour Organization, for instance, provides de jure stakeholder inclusion, but power differentials between wealthy governments/employers and unions from developing countries can limit de facto inclusion.Footnote 73

De facto inclusivity can also thrive even without de jure recognition, as seen in informal networks that enable stakeholder engagement and influence. The Group of 20 (G20) serves as an example where NSAs, despite lacking formal access, can still penetrate and contribute to governance discussions through de facto channels. By focusing on both de jure and de facto dimensions of inclusion, our framework enables exploration into the relationship between these dimensions, and more systematic and comprehensive insights into the challenges in achieving more inclusive global governance.

Unpacking inclusivity in global development partnerships

Notes on method

How can the de jure/de facto framework help us understand inclusivity in practice? In developing our heuristic, we not only engaged with extant literature but also abductively drew upon the case of the GPEDC: an MSP that aspires to encompass the full range of state and NSAs within the fragmented field of international development.Footnote 74 As with other policy fields, international development has been characterised by a persistent North–South divide, limited opportunities for non-state participation in GGIs, exclusive club-like governance, and Northern state dominance. Given the GPEDC’s aspiration to overcome these tendencies by providing a more inclusive model, it serves as a key illustrative case to explore de jure and de facto inclusivity dynamics within global governance. The organisational and contextual characteristics of the GPEDC (discussed below) resemble pertinent features of other MSPs across global governance, such as origins within critiques surrounding traditional state-dominated multilateral processes, NSA participation structures, an explicit commitment to inclusivity, and stark power disparities among and across state and NSAs.

Our intention regarding the case is not to develop generalisable empirical insights that invariably apply to other GGIs, but to provide an ideographic engagement that can assist with theory development and empirical illustration, and to demonstrate the appropriateness and analytical power of our framework.Footnote 75 While generalisation is not our intention, the ‘transferability’ of insights is however possible between our and other cases. As we cannot fully anticipate the specific contexts that others may wish to transfer the findings to, we provide a sufficiently thick description of the case ‘so that those who seek to transfer the findings to their own site can judge transferability’.Footnote 76

Both the development of the conceptual framework and the analysis of the GPEDC are anchored in our commitment to a ‘pragmatist’ methodology, eschewing the rigid binaries of induction and deduction that ostensibly characterise theoretical development and empirical research. Rather, we follow the view of Ragin and Rosenau that social research can be productively viewed as an iterative dialogue between theory and data – ‘an endless cycle in which theory and research feed on each other’.Footnote 77 We thus employed an ‘abductive’ approach that involved an ongoing, iterative, and reflexive dialogue between theory, data, and researchers.Footnote 78 Accordingly, our familiarity with the GPEDC initially granted us empirically grounded insights into the challenges of realising inclusive governance, particularly in a context where the SDG agenda places a significant emphasis on ‘inclusive’ partnerships. Hence, the case offers ‘an example from which one’s experience, one’s phronesis, enables one to gather insight or understand a problem’.Footnote 79 This a posteriori understanding initially prompted us to question and assess the prevailing focus on de jure inclusivity in existing approaches. Combined with an in-depth exploration of extant literature on inclusion in global governance, this culminated in the development of a more comprehensive and nuanced framework that we then applied to the analysis of the empirical data.

Our research spanned from 2013 to 2022, including participant observation via both authors working as members of the GPEDC secretariat and organising and attending high-level political events at the OECD in Paris, the UN in New York, as well as in Geneva and Mexico City. We conducted 97 semi-structured interviews with a purposive sample of key representatives, including 18 from DAC donor countries, 18 recipient country representatives, 15 South–South cooperation (SSC) provider or ‘dual-category’ representatives, 10 civil society organisations (CSOs) and networks, 7 private sector representatives, 12 from think-tanks and academia, 9 from the GPEDC secretariat, and 8 from UN bodies. Additionally, we reviewed relevant academic literature, working papers, meeting materials, budgets, reports, and policy documents.

Our research activities culminated in a comprehensive database on the GPEDC, including stakeholder perceptions (from interviews), internal procedures and power dynamics (from participant observation), and insight into longitudinal, procedural, and substantive issues (from the review of organisational material). We transcribed interviews and observation notes and used NVivo qualitative software for coding and organising the data. Our initial coding schema focused on stakeholder perceptions of the GPEDC’s inclusivity, representative structures, and equality according to a basic scheme of whether respondents held a ‘positive’, ‘neutral’, or ‘negative’ perspective. For the de jure components, we drew on official documents to identify formal definitions of stakeholders, while we coded stakeholder views on key institutional elements associated with the GPEDC and its relationship with the broader UN and OECD systems. For the de facto ‘recognition’ component, we organised and drew on coded stakeholder views on the legitimacy of one another, such as recipient views on CSOs, the BRICS, and private sector participation in the partnership (and vice versa). For ‘pull’, we drew on codes focused on the reasons for (non-)engagement in the GPEDC, including issues such as ‘declining multilateral orientations’, ‘domestic political will’, ‘relevance to SDG agenda’, ‘resource and energy requirements’, and issues surrounding the monitoring framework. For ‘capacity’, we developed codes related to capacity differentials in the partnership, such as perceptions of opportunities for ‘parity in engagement’ and views on ‘donor dependence’, ‘donor dominance’, and ‘resource constraints’.

When analysing the interview material, we did not rely on the frequency of codes as a direct measure of representativeness or prevalence of views as we recognised that some interviewees spoke on behalf of their broader constitutency, while others specified that they were speakign in a personal or organisational capacity. Instead, we avoided the direct quantification of our qualitative data and relied upon a more contextual understanding of interviewee statements. Participants’ anonymity was strictly maintained, with only general identifying information, such as stakeholder type and region. In presenting our interview-based findings on the interviews, we primarily rely on statements by stakeholders speaking in a representative capacity within the GPEDC and – where appropriate – triangulate these with other sources of data.

Background

The traditional landscape of international development governance has been divided between Northern donors and Southern recipients, creating a hierarchical development order.Footnote 80 Since the 1960s, the DAC has been the most visible embodiment of this divide, with Northern donors defining and measuring foreign aid as Official Development Assistance (ODA).Footnote 81 However, since the 1990s, state and NSAs beyond the DAC have become more prominent.Footnote 82 China and India, for instance, do not follow DAC definitions but promote SSC discourses and practices.Footnote 83 Together, these trends have led to an increasing proliferation of actors and venues across the field of international development.Footnote 84

Criticism of the DAC’s exclusive membershipFootnote 85 – its lack of de jure inclusivity – led to calls for reform from recipients, Southern providers, and civic actors, thereby ‘challenging its very nature as the pre-eminent donor forum’.Footnote 86 For some, the DAC’s survival was dependent on its capacity to include these ‘new’ actors within a legitimate and effective global governance mechanism.Footnote 87 The DAC therefore organised high-level fora in Rome (2003), Paris (2005), and Accra (2008) to both enhance aid effectiveness and broaden governance to include Southern countries, CSOs, and private foundations. Despite these efforts, major Southern actors remained hesitant to participate as development providers due to perceived incompatibilities with their own practices.Footnote 88

The DAC-sponsored 2011 Busan Forum marked a turning point: it secured the inclusion of SSC actors, culminating in the establishment of the GPEDC.Footnote 89 The GPEDC was presented as a shift towards a broader view of ‘development effectiveness’ wherein ODA would serve a complementary role alongside other public and private financial instruments.Footnote 90 The GPEDC would supposedly herald a more inclusive landscape in which ‘the old [DAC] donor–recipient relationship is replaced by an equator-less landscape of a multi-stakeholder global partnership’.Footnote 91

In what follows, we explore the extent to which this ambition has been realised. We first examine the de jure structure of the GPEDC and stakeholder perceptions thereof, then briefly outline participation data over time and key stakeholder contentions, before examining how the de facto components of our framework can help us make sense of the observed patterns.

De jure inclusivity: An inclusive governance structure par excellence

Since its first steering committee meeting, ‘inclusiveness was emphasised as a key element of the Global Partnership’.Footnote 92 In terms of formal stakeholder definition (component 1A in our conceptual framework), the GPEDC’s commitment to inclusivity was reaffirmed in its 2016 renewed mandate, and it outlined the constituency system of its steering committee:

The Global Partnership brings together, on an equal footing … developing countries … as well as countries of ‘dual character’ (that both receive and provide development cooperation); developed countries [donors] … multilateral and bilateral institutions; civil society; parliaments; local governments and regional organisations; trade unions; private corporations; and philanthropic institutions.Footnote 93

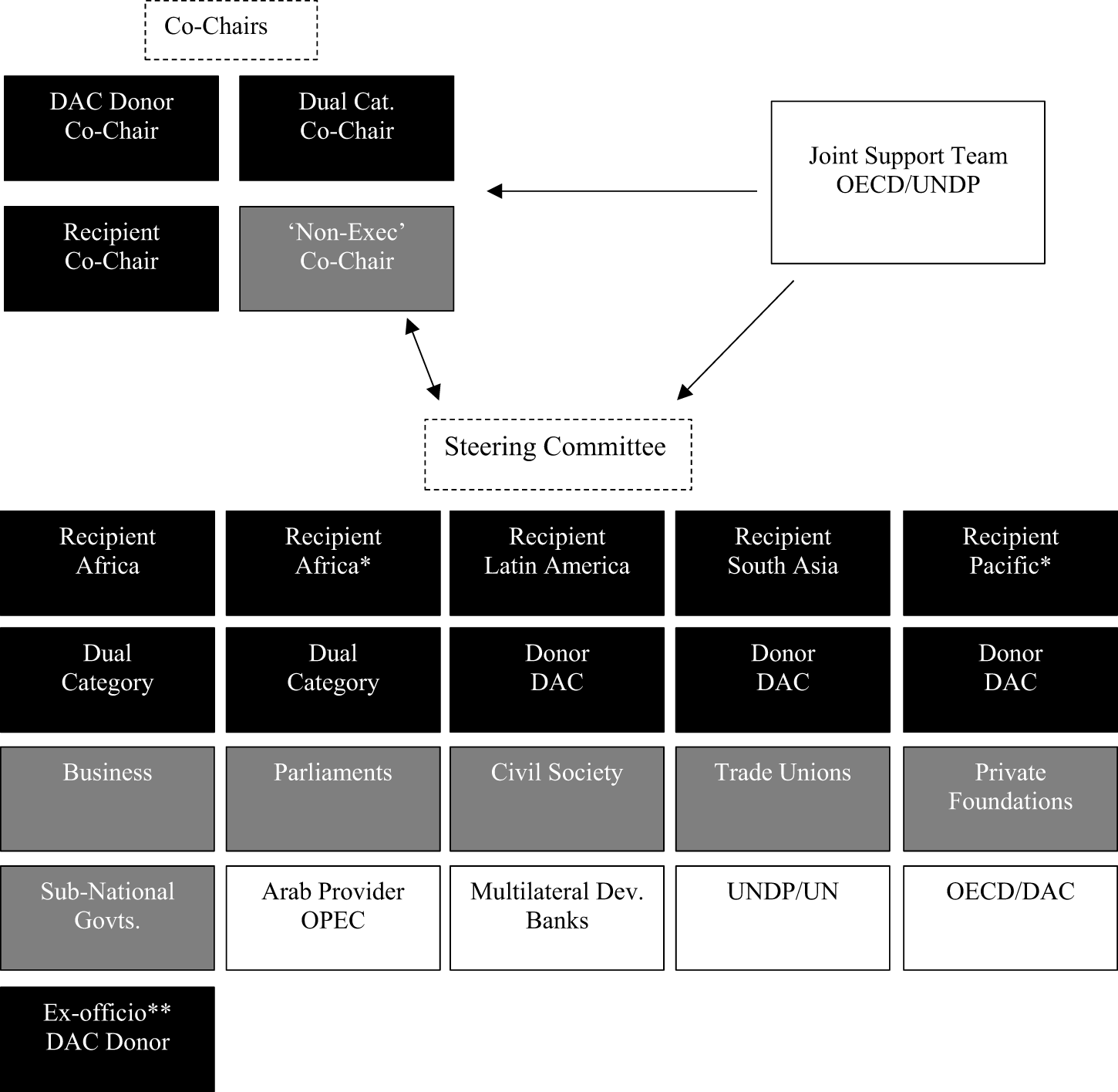

The GPEDC’s formally institutionalised governance structure (component 1B) comprises three bodies (see Figure 1). The 20-member multistakeholder steering committee is the main decision-making body that meets twice a year to provide ‘strategic leadership and coordination’ over the partnership’s programme of work.Footnote 94 Committee members are responsible for ‘consulting with, and therefore providing inclusive and authoritative representation of, constituencies with a stake in the work of the Global Partnership’.Footnote 95 The Committee is led by three co-chairs, one from DAC (donor) countries, one from recipient countries, and one from ‘dual-category’ countries. In 2019, and in response to critiques surrounding formal non-state inclusion, a fourth non-executive co-chair was introduced (see below) to represent non-state stakeholders at the highest decision-making level.

Figure 1. De jure governance structure of the GPEDC.

The Joint Support Team, comprising staff from the OECD and the UN Development Programme (UNDP), acts as the GPEDC secretariat, providing logistical and substantive support to the steering committee and co-chairs. During discussions and negotiations surrounding the partnership’s formation, the joint hosting of the secretariat was a conscious effort to explicitly connect both parent organisations, with UNDP’s focus on Southern concerns as a counterweight to what was perceived as the OECD’s strong Northern bias.Footnote 96

For many stakeholders, the GPEDC embodies an inclusive governance structure par excellence. The results of a survey commissioned by the GPEDC ‘suggest a strong convergence [among respondents] that the diverse, multi-stakeholder nature of the Global Partnership is its main added value’.Footnote 97 Bena and Tomlinson highlight that ‘the global partnership is a uniquely inclusive global initiative in which NSAs play a full role, alongside governments, in its governance and outcomes’.Footnote 98 Praise for the GPEDC’s de jure structures was confirmed via the interviews we conducted with key representatives of each stakeholder category. A DAC donor representative suggested that ‘the value-added of the GPEDC lies in its unique structure and composition of various partnerships. So far, the GPEDC is the only organisation that allows civil society equal status in the steering committee.’Footnote 99 One European CSO representative highlighted that ‘the GPEDC is one of the best examples where CSOs have a very well-defined role which is very close to that governments have from a purely formal basis’.Footnote 100 A Latin American dual-category country representative also reported that the GPEDC’s ‘is unlike any other process that I am familiar with … it is very inclusive and really an exemplar of a multistakeholder process’.Footnote 101 Recipient representatives from fragile and conflict-affected states likewise praised the GPEDC as ‘it has given countries which were [previously] rarely heard a forum where their concerns and priorities can be heard on a global level’.Footnote 102 Participating stakeholders have thus broadly recognised the GPEDC’s de jure dimensions as enabling an ‘amazing, inclusive process’.Footnote 103 Formally, the GPEDC seems to represent a significant endeavour in implementing inclusive global development governance. It defines and recognises numerous categories of development actors as legitimate participants and grants them a remarkable level of institutionalised access.

Participation over time: Patterns and challenges

The GPEDC boasts formal endorsements from 161 countries and 56 international organisations.Footnote 104 It contends that its formal accommodation of NSAs sets it apart from other development governance arrangements: the ‘GPEDC is broader than, and more inclusive of, other development actors, which distinguishes it from the OECD or G20’.Footnote 105

The GPEDC convened 1,500 senior delegates at its first High-Level Meeting in Mexico City in 2014 and 4,600 delegates at the second meeting in 2016 in Nairobi (a figure bolstered primarily by the strong presence of local actors). At a Senior Level Meeting (SLM) in New York in 2019, the GPEDC convened over 600 senior-level participants (see Figure 2). Disaggregating CSO representation at that meeting reveals that 61.8% of participants came from organisations based in the Global South, whereas 38.2% came from the Global North. The GPEDC thus not only seems to have an ostensibly well-balanced degree of stakeholder representation by type (e.g. state, non-state), but also according to geographical region as concerns participation at major events.

Figure 2. Number of participants per stakeholder category at the GPEDC 2019 senior level meeting.a

Looking past these headline figures, however, engagement trends within the GPEDC are more complex. Foremost, the GPEDC has faced a consistent lack of engagement from major SSC providers. While perhaps the key promise of the GPEDC was that it would provide a joint forum for Southern powers – notably China, Brazil, and India – to participate in a global development governance partnership alongside the DAC, the former have consistently refused to participate.Footnote 106 The ‘dual-category’ co-chair has subsequently been occupied by smaller providers, including Mexico, Indonesia, and El Salvador, leading to perceptions on behalf of DAC donor representatives that the GPEDC is not ‘truly inclusive because it doesn’t have the [major] SSC providers’.Footnote 107

In addition, the GPEDC has also suffered from declining DAC donor engagement in recent years.Footnote 108 While the GPEDC has been able to continuously secure a DAC representative for both the co-chair and steering committee positions, we observed declining seniority in terms of the representatives that DAC members have sent to subsequent high-level and senior meetings. Furthermore, securing participation from these actors often required a great deal of ‘arm twisting’ behind the scenes by the GPEDC secretariat.

The lack and/or declining participation of large SSC providers and DAC donors contrasts strongly with the engagement from Southern recipient countries. Perhaps the most visible aspect of this trend can be observed regarding those recipient countries participating in the GPEDC’s monitoring exercise of development effectiveness, one of the partnership’s core governance outputs. Participation in the GPEDC’s 2018 monitoring round almost doubled, with 86 countries participating, compared to only 46 countries in the 2016 round.Footnote 109 In contrast to the relatively junior level of DAC representation at recent GPEDC events, Southern countries tend to send more senior representatives – including at the presidential and ministerial level, as at the 2022 summit – thereby highlighting the importance that these actors ascribe to the partnership.Footnote 110

Concerning non-state participation, CSOs have been consistently active within the GPEDC, primarily through a Manila-based coordinating platform, with members across different world regions whose activities span several sectors.Footnote 111 Inversely, however, the GPEDC has struggled to maintain regular and sustained engagement from the private sector, also highlighted by GPEDC survey results.Footnote 112 Hence, the European Union (EU) and its member states have consistently highlighted their concerns surrounding the lack of engagement of two major stakeholder categories, the private sector and large SSC providers.Footnote 113 In addition, persistent concerns abound regarding the character of those representing the ‘private sector’: at the first GPEDC meeting in 2014, the ‘presence of a few handpicked African entrepreneurs failed to disguise the heavily Northern-corporate feel of the private-sector presence’.Footnote 114 The private sector representative on the steering committee has, invariably, been from a Northern-based organisation or network.

De facto inclusivity

Beyond its ‘exemplary’ model of de jure inclusivity and challenges related to formal participation, to what extent has the GPEDC offered a space for meaningful stakeholder inclusion? We now turn to the de facto components of our conceptual framework to take a more detailed look at informal stakeholder dynamics at the GPEDC and thus unpack aspects of global governance inclusion attempts that often remain hidden.

2A Recognition

To what extent do GPEDC stakeholders regard one another as legitimate participants in practice? At the first high-level meeting of the partnership in Mexico City in 2014, CSOs expressed concern over the disproportionate role afforded to the private sector.Footnote 115 This, alongside perceptions of shrinking civic space, prompted a collective protest, with CSO representatives donning Mexican wrestling masks to express their grievances prior to the final plenary.Footnote 116 Some CSO representatives suggest that their participation at the GPEDC has been ‘tokenistic’ – while ‘CSOs are consulted to death… decision-making is done by governments and donors’.Footnote 117 Yet others contend that the high degree of de jure status afforded to CSOs in the GPEDC has set a precedent, but one that ‘many governments are uncomfortable with’.Footnote 118 Due to significant resistance from some recipient country representatives who feared the dominance of non-state voices, it took nearly seven years of persistent advocacy by the GPEDC’s non-state members to secure the fourth (non-executive) co-chair position, and this was only made possible due to the expressed support provided by large Northern donors (the EU and Germany). We can, therefore, observe a somewhat antagonistic relationship between CSO and some Southern state representatives in the partnership. Some of the latter, for instance, contend that the GPEDC’s de jure structures are ‘too global’ (i.e. too inclusive), and that this risks ‘an overrepresentation of CSOs in GPEDC meetings to the detriment of other stakeholders’.Footnote 119

While civic actors thus do not feel that they are regarded as legitimate stakeholders by all states, CSOs likewise do not extend recognition to all non-state (corporate) actors. They clearly distinguish between the (legitimate) engagement of small and medium private enterprises and the (often-problematic) role of larger transnational corporations. They ‘oppose’ the latter on the basis that they are being ‘aggressively invited in’ to the GPEDC, without clear parameters as to their role within ‘development’.Footnote 120 In more explicit (and zero-sum) terms, a CSO representative from Pakistan remarked that the private sector was a ‘grotesque creature that is eating up our space’.Footnote 121 Likewise, a Southeast Asian CSO representative suggested that the GPEDC’s de jure achievements towards ‘recognising civil society as an equal partner … is sort of slowly being eroded because there’s a strong push to bring in the private sector: a private sector which is not clearly defined’.Footnote 122

Structurally more dominant players have also raised concerns about the translation of (un)clear stakeholder definitions into de facto representation. A former DAC representative recognised that the GPEDC had made strides towards including a ‘diversity of voices, [but] clear-cut direct representation for all development stakeholders, I don’t think we got there’.Footnote 123 For a private foundation representative, the difficulty in providing effective representation – and being recognised as such – for non-state constituencies was apparent: ‘It’s difficult for me sitting on the steering committee to say, “I speak for foundations globally”, because I do not … But it’s [also] very hard for the civil society representative to say that he or she represents all of [global] civil society.’Footnote 124 While those who represent non-state constituencies can be ‘quite committed’, there is – according to one CSO representative – a lack of clarity over ‘who the hell they represent’.Footnote 125

2B1 Pull

The GPEDC may formally recognise hitherto marginalised actors as legitimate stakeholders and offer institutionalised structures for engagement, but do stakeholders deem the institution worthwhile to engage with? Efforts towards ‘private sector engagement’ have mostly been driven by leading donor states, rather than corporations themselves seeking a seat at the table. The business representative on the steering committee highlighted in 2014 that the protracted formal process surrounding preparations for the first high-level meeting alongside the lack of clarity around multi-stakeholder decision-making mechanisms ‘is untenable in the longer term … [and] not conducive to strengthening business interest in the Global Partnership, where companies have great difficulty in navigating these international fora’.Footnote 126 On the lacklustre degree of private sector participation, one business representative suggested that: ‘if you’re looking globally, the GPEDC is … just another forum, and it’s a forum where there has been a lot of talk, and it’s not clear how that leads to action. As business wants action, it’s difficult to see how any individual company really benefits from it.’Footnote 127 Despite the efforts of donor states, the OECD, and the UN, the GPEDC has struggled to attain regular and sustained engagement from the business community.Footnote 128

Moreover, though China, India, and Brazil initially agreed to the 2011 Busan Outcome Document, they made it clear at the GPEDC’s 2014 high-level meeting that they would not formally join the partnership. For a dual-category country representative, this meant that the GPEDC’s ambition ‘to represent the global community on development cooperation is lacking … and this kind of non-engagement turns it into another donor country-driven platform’.Footnote 129 China, India, and Brazil instead affirmed that the UN Development Cooperation Forum was the appropriate venue for development cooperation discussions, rejecting the GPEDC as another unwelcome DAC-led incursion into monitoring their sovereign development cooperation activities.Footnote 130

Many recipient states, however, have viewed the GPEDC as an appropriate platform to address long-standing governance issues between donor and recipient countries. A West Asian representative remarked that while ‘it would help a lot to have the Chinese in … this doesn’t affect the Global Partnership [as] the Global Partnership has more-so to do with [recipient relationships with] the traditional donors’.Footnote 131 Likewise, another recipient representative argued that the creation of the GPEDC ‘was meant to improve [traditional] development partner’s engagement especially in recipient countries like us’.Footnote 132

Similarly, a considerable number of civic actors regard the GPEDC as an appropriate venue and participate actively, evidenced by the high and consistent degree of civic participation in all GPEDC meetings that is primarily organised through the CSO Partnership for Development Effectiveness.Footnote 133 As a European CSO representative acknowledged: ‘You can’t call yourself a global partnership without having those [large Southern] players involved, but they’re just going to weaken the strength of the [accountability] commitments … well good riddance then.’Footnote 134 Another CSO representative argued that GPEDC architects ‘hurt themselves by trying to enlarge the tent [towards Southern providers] … because you dilute and you change focus … just to be relevant to a few stakeholders’.Footnote 135 Despite limited private sector and SSC provider involvement, there is thus considerable political will from civic representatives towards the GPEDC.

The declining engagement of DAC states, as discussed earlier, suggests that Northern donors regard the lack of participation by large SSC countries as a failure of the GPEDC’s original purpose. Consequently, many donors no longer find that the GPEDC possesses sufficient institutional pull towards their regular and sustained participation. An aid effectiveness expert remarked that while recipient countries are ‘really keen’ on this process:

My line has always been that the GPEDC will simply never fly as a genuinely global partnership because of its [DAC] history, and that’s been proved absolutely right, the major Southern donors are just not interested in getting involved. But what I didn’t anticipate, was that the major Western donors are also now losing interest.Footnote 136

Members of the Joint Support Team see the lack of engagement of India, Brazil, and especially China in the GPEDC as a major challenge, also because it weakens DAC country commitments to the partnership. OECD representatives highlighted that ‘the Mexicans had tried really hard [in 2014] to bring China on board but it didn’t work out; I don’t know what else we can do … but I know that without China … [the GPEDC] will face serious challenges’.Footnote 137 From a UN perspective, the inclusion of large Southern players has been even more important. As a UNDP official put it: ‘We are there because we can accompany the entire UN membership … but if China and others are missing, this undermines the whole idea.’Footnote 138

2B2 Penetrability

Given the lack of engagement by large SSC providers, and issues concerning the de facto recognition of NSAs, questions of penetrability through informal means take centre stage: ‘Having a seat at the table is fine but if they [governments] don’t talk to you when it matters, that seat doesn’t mean much.’Footnote 139 At the 2014 meeting, for instance, a CSO representative remarked that: ‘It is great that we are here as official delegates … but what really matters is talking to people, to my government, when others don’t listen; coffee breaks are really important.’Footnote 140 Our evidence suggests that, at least in some cases (and notably in the Latin American context), formal engagement at the GPEDC has indeed provided the foundation for expanding CSOs’ informal access to government bodies in charge of development-related questions. As one Latin American CSO representative reported, government officials ‘often turn to us for thematic input, this never happens formally, but it helps strengthen our standing … It is helpful that we are officially invited to Global Partnership processes; but what really matters is that we know how to get our content to those who matter.’Footnote 141

Informal means have also been influential for the participation of stakeholders from large Southern powers, albeit differently. Think-tanks from China, India, and Brazil, affiliated with their respective governments, co-launched the Network of Southern Think Tanks at the first high-level meeting, linking the GPEDC to domestic voices from countries that had not formally joined the partnerships.Footnote 142 Early on, Shankland and Constantine thus suggested that despite limits in bringing all relevant SSC governments to the table, ‘the GPEDC has instead succeeded in opening up space for another kind of partnership’ – focusing on knowledge exchange between think tanks – ‘which could in turn help to bridge the gaps … between the North and South, and between governments and civil society groups from the South’.Footnote 143 While this informal engagement has failed to satisfy DAC donors’ expectations of including Southern players in the GPEDC and to give Southern NSAs a formal seat, it demonstrates other ways to potentially bypass and increase agency beyond de jure structures.

Overall, individuals often have more influence at the GPEDC than formal set-ups suggest. In the context of unequal power relations, individual agents ‘hold a kind of de facto governance power’ where think-tank representatives engage despite governmental reservations and CSO leaders establish informal channels for coordination and exchange.Footnote 144 Interviews suggest that representatives of the Joint Support Team or co-chairs, in particular, have made a real difference in whether and how they have kept (all or only some) stakeholders up to date or informally provided guidance on decision-making processes.Footnote 145

2B3 Capacity

Irrespective of the existence of (in)formal engagement channels, whether stakeholders are effectively included also depends on their capacity to engage on a regular and sustained basis. As recognised by a DAC member representative, participation is ‘not only about formality… but [also] the possibility to actually participate’.Footnote 146 Despite reduced donor involvement, the GPEDC is still seen as controlled by the DAC. On the GPEDC’s supposed horizontality, a CSO representative remarked that ‘what’s on paper differs from reality’, as ‘ultimately, one side has all the money, and the other side doesn’t … So, even if you give everyone a vote … there will always be that power dynamic.’Footnote 147

Although the GPEDC is funded by contributions from the OECD and UNDP, resources come from only a handful of donors: Switzerland, Canada, the EU, Ireland, South Korea, and Germany.Footnote 148 Thanks to the financial support of these few DAC members, and despite overall donor disengagement, the GPEDC has been able to carry out its work. One ‘dual-category’ representative thus argued:

Recipient countries see value in [the GPEDC]. But it is not simply about participation, it is also about … who is cooking that meal? Traditional donors are cooking it, and then presenting it. And it is not only their [donor’s] fault … there is also a capacity problem in many of these other [recipient] countries … They may have financial problems as well, which may not be compensated by the contribution of donor countries.Footnote 149

Our evidence suggests that the issue is not so much conspiratorial efforts by donors to control proceedings but rather the persistent structural imbalances between rich and poor states: ‘it is a partnership of equals but it’s the more active equals. So, this is not a criticism, but just that the partner countries are just not nearly as active [as other stakeholders].’Footnote 150 The reason is that, according to a recipient representative, ‘most of the times, we are more passive. Not because we don’t know what our challenges are. But we are overwhelmed by the issues back home.’Footnote 151

The varying institutional capacity and economic resources between stakeholders also affect de facto dynamics of recognition (component 2A). While many recipient countries are supportive of attempts to promote an equal playing field, one East African country representative highlighted that:

I don’t think there is equality between civil society, for instance, and the governments in the Global Partnership. The governments have the lead because it is they who gives [sic] the money and it is really the government that put in action the programmes. So, I don’t think that there is equality between all the stakeholders.Footnote 152

For some CSO representatives, long-standing disparities and dependency dynamics go to the core of influence and participation within the GPEDC:

Much of the control is with governments. It is with states and, even between states, there’s still a disparity between donors and recipients … [the latter] are still beholden to the donor countries … much of this is also dependency, economically, and probably in terms of political influence … The donors who will speak, they still have the [economic and political] control.Footnote 153

Those who represent the private sector, in turn, typically are not small and medium enterprises from developing countries, but rather a few Northern business associations who possess the necessary capacity to engage. While this is arguably not a deliberate attempt to dominate proceedings, those Northern corporate actors that decide to engage do so because they have the necessary resources. Overall, as one donor put it, capacity differentials at the GPEDC reflect the power of ‘... the “golden rule”: the person or the organisation with the gold makes the rules’.Footnote 154

Discussion and conclusion

This article contributes to ongoing debates on the inclusivity of global governance by providing a conceptual framework that systematically explores how formal and informal dimensions of inclusion interact, driven by a commitment to what we have termed meaningful inclusion.Footnote 155 The latter encompasses inclusive governance that resists co-option dynamics and superficial ‘checkbox’ inclusion and instead fosters sustained participation and the preconditions for genuine influence by a diverse range of affected stakeholders. We adopt a ‘sociological’ approach by juxtaposing normative claims with stakeholders’ own evaluations of key inclusivity components.

Applying our framework to the analysis of the GPEDC, we find that despite its formal inclusivity, the partnership faces challenges across various de facto components. There are ongoing disputes over who is recognised as a legitimate and equal stakeholder, especially between civic actors and Southern states, or between civic and private actors. CSOs rely on penetrability through informal channels to access government representatives, while informal channels also enable indirect engagement with recalcitrant SSC providers. But the GPEDC’s limited institutional pull for China, India, and Brazil has weakened DAC donor support. Significant capacity disparities among stakeholders also disadvantage the effective engagement of actors with fewer resources, particularly smaller Southern states and CSOs.

Based on the illustrative nature of our case, we can outline some general trends. Insights from the GPEDC resonate with those who point to significant progress in de jure inclusivity. The partnership’s unprecedented formal access for NSAs suggests potential to mitigate long-standing North/South and state/non-state inclusion issues in global governance. Yet intractable challenges emerge in de facto practice. While issues pertaining to institutional pull can be partially rectified via tailored communication and engagement strategies towards recalcitrant actors, these are increasingly difficult to manage in a global governance context characterised by ever-increasing institutional overlap and competition for political engagement. Further, fostering recognition between state and NSAs requires major cultural shifts, while there may be deeply political motivations for large Southern states to rally against ‘multistakeholderism’ as a global governance modality.Footnote 156 Finally, while targeted capacity building may close some gaps, it cannot fully overcome deep-rooted power imbalances.

Our analysis thus aligns with Dingwerth’s insight that the democratic – or here ‘inclusivity’ – deficit does not lie in the de jure dimension, but that access is ‘informally restricted through a plethora of … structural inequalities that pervade global politics’.Footnote 157 Contrary to most studies on inclusion, however, our case provides the surprising insight that the primary deficit as concerns GGI inclusivity derives from a lack of participation of large Southern powers, and concomitant impacts upon declining donor engagement. Hence, it is those with capacity, rather than those without, who are refusing to participate and have undermined the effective functioning and inclusive quality of the GPEDC. With China recently launching its Global Development Initiative, ostensibly aspiring for an ‘inclusive partnership’ between the Global North and South to tackle sustainable development challenges, we anticipate similar inclusivity challenges: the limited ability of civic actors to independently participate in China-dominated spaces, alongside the unlikely engagement of Northern states due to Western anxieties over the initiative.Footnote 158

Ultimately, our framework and analysis underline that power and interests, rather than formal procedures, are decisive factors in achieving meaningful inclusivity in global governance. Recognising these structural obstacles is essential for identifying strategies that, despite promoting formal inclusivity, may ultimately reinforce the authority of the powerful. This is not, however, to suggest that there are no incidents of meaningful inclusion, but rather to temper declarations on the supposed ‘inclusiveness’ of contemporary global governance.

We thus encourage further investigation into how the relationship and tensions between de jure and de facto inclusivity – as well as among stakeholders themselves – affect governance outcomes, and the extent to which the level and quality of inclusion correlate with partnership impact.Footnote 159 While our in-depth analysis of the GPEDC has revealed that de facto dynamics – specifically surrounding institutional pull and capacity – have undermined the GPEDC’s inclusivity, other components might be more prominent in other contexts. We hope that our framework serves as a productive and systematic foundation for understanding inclusivity dynamics and contributes to broader explorations of the evolution of global governance and the interests it serves.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank participants at the European Consotrium for Political Research Joint Session on ‘Complex Global Governance: Actors, Institutions, and Strategies’ (19–22 April 2022) and those at the ‘Legitimacy and Legitimisation of Global Governance in Crisis’ workshop of the Global Policy Institute at the University of Durham (3–4 November 2022) as well as Erin McCandless and Kavi Abraham for their input and comments on earlier drafts of this paper. We would also like to thank the editors and the three anonymous reviewers for their comments, suggestions, and support.