Introduction

Millennials, born between 1981 and 1996, are the first generation in the post-war era, in Europe, projected to be financially worse off than their parents (Antonucci et al., Reference Antonucci, Hamilton and Roberts2014: 1). They will be, on average, more excluded from the traditional cornerstones of adulthood: stable employment (Furlong et al., Reference Furlong, Goodwin, O’Connor, Hadfield, Lowden and Plugor2017: 11), owner-occupied housing (McKee, Reference Mckee2012), and thus, having children (Brown, Reference Brown2021). However, they have been instructed through the market-orientated state that it is the responsibility of the individual to realise a secure future, despite being disproportionately affected by economic recessions (Bell and Blanchflower, Reference Bell and Blanchflower2011; Mont’Alavo and Ribeiro, Reference Mont’alavo and Ribeiro2020), insecure labour markets (Kalleberg, Reference Kalleberg2020), and recent welfare reforms (McPherson, Reference McPherson2021). The young people from this generation also experienced the most stringent welfare conditionality and the highest rates of benefit sanctions the UK has ever seen (Webster, Reference Webster2017); however, their generational perspective has been neglected from recent welfare conditionality research. It is important to imbed generational perspectives in social policy analysis given the unique and emerging challenges recent generations of young people will face (Woodman, Reference Woodman2022).

This paper will address this gap and advances the existing literature by exploring how behavioural welfare policies shape youth aspirations. Secondary analysis of the qualitative longitudinal data showed patterns in young people’s tendencies for self-blame and the internalisation of structural problems. I coined this inductive concept internalised individualism. The nuanced narratives of young people’s experiences of employment, low-income, and welfare conditionality over time will demonstrate the strength of internalised individualism and how it typically does not correlate with enhanced employment prospects or outcomes.

This paper was developed from my ESRC-funded doctoral research, where I drew upon qualitative longitudinal data from the Welfare Conditionality (WelCond) Project (2013–2019), to recontextualise and conduct innovative secondary analysis to explore and illuminate the experiences of welfare conditionality specifically among the young people (sixteen to twenty-five) from the UK-wide dataset. More information about the original project and my secondary research will be detailed in the methodology section of this paper.

The psychologisation of social problems

There has been a recent invasion of self-help and positive psychology into nearly all aspects of life, be it health (Ehrenreich, Reference Ehrenreich2009: 7), education (Reay, Reference Reay2021), career (Du Plessis, Reference Du Plessis2021), romantic life (Hazleden, Reference Hazleden2003), or corporate (Witmer, Reference Witmer2019) and state (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Pykett and Whitehead2013; Charter and Loewenstein, Reference Charter and Loewenstein2021) strategies to address inequalities. The doctrine of self-help governance is rife, in the sense being a master of the self is increasingly seen as both a choice and the gateway to economic security (Rimke, Reference Rimke2000; Vassallo, Reference Vassallo2020: 18). Framing the social world as a battle of psychological selfhood, in which individuals have the ability to carve out their own destiny with vague guidance from ‘experts’, is pervasive in advanced capitalist societies, which shapes, and is shaped by, contemporary governance and social policies, such as conditional social security models (Friedli and Stearn, Reference Friedli and Stearn2015).

The strong belief in self-governance is used to justify reductions for state intervention and eases pressure on the state to protect all citizens, as self-improvement is positioned not only as a matter of free will but also as a ‘natural undertaking by well-meaning citizens’ (Rimke, Reference Rimke2000: 63). Millennials’ transition to adulthood has coincided with the psychologisation of everyday life and the ‘therapizaiton of social justice’ (Eccleston and Brunila, Reference Eccleston and Brunila2015: 490). This quasi-religious belief system, centred on the omnipotent power of projecting or adopting behavioural traits, such as confidence, motivation, and outgoingness, in terms of realising future aspirations, has been pedalled more readily through proliferating social media and the influencer culture (ibid). I argue the hollow motivational discourse is a convenient ‘scientific’ basis from which liberal states can govern citizens to self-govern, to maintain existing power structures, and reproduce the individualist neoliberal status quo.

The libertarian paternalism and the nudge economics in which recent social security systems in the UK operate (Gane, Reference Gane2021), positions autonomy and self-actualisation as a behavioural choice and goal. With regard to the now prevalent nudge theory (Thaler and Sunstein, Reference Thaler and Sunstein2008) across UK policy governance, Gane (Reference Gane2021: 140) argues:

This project is guided by an ideal of libertarian paternalism that treats individual market freedom as the basis of all freedom, and which bypasses concern for the structural inequalities – be these of class, gender, or race – of contemporary capitalist society by shifting attention to what are seen as the irrational and misguided choices of individuals.

Thus, unemployment and poverty have been positioned by successive UK Governments as an individual deficiency rather than the product of entrenched complex structural inequalities (Patrick, Reference Patrick2020), such as the lack of informal support networks available to the cohort of young people in this study when compared to their more affluent peers, which has been found to negatively correlate with employment outcomes (Lalive et al., Reference Lalive, Oesch, Pellizzari, Spini and Widmer2023). Therefore, through the continual responsibilisation of social security recipients, structural barriers, such as lack of stable labour market opportunities, caregiving responsibilities, and health conditions become distorted and downplayed.

Intergenerational inequalities and the framing of the policy problem

Young people who are so called NEET (not in employment, education, or training) are a group that attracts considerable attention and vilification from public bodies (Wilkinson and Ortega-Alcazar, Reference Wilkinson and Ortega-Alcazar2017). However, recent analysis demonstrates policymakers over emphasise honing young people’s employability when demand-side shortages persist (Crisp and Powell, Reference Crisp and Powell2017).

Particularly for Millennials, before the broader factors at play in a person’s lack of income or stable employment are considered, out-of-work young people are positioned by the centre-right state as intrinsically vandalised souls who require rehabilitation (Friedli and Stearn, Reference Friedli and Stearn2015). As Boland and Griffin (Reference Boland and Griffin2022: 55) argue, the blanket approach of labour activation policies across Europe for addressing the problem of youth unemployment in the contemporary insecure labour market, is ideological and misguided:

Taken from an EU-level briefing on unemployment – addressing the existence and experience of literally millions of people – a singular remedy is offered: ‘Benefit recipients are expected to engage in monitored job-search activities and improve their employability “in exchange” for receiving benefits.’

Policy interventions which seek to address social inequalities in the UK, typically encourage young people to project lofty aspirations which transcend their social background, such as high-status occupations for working-class youth, and self-reliance, as the key to reaching the cornerstones of adulthood (Chapman, Reference Chapman, Lawler and Payne2018: 139). This rhetoric is particularly targeted at marginalised young people who do not have the resources to conform to the ideal neoliberal subject. However, if they align with the individualised aspirational self, they will look internally to realise the increasingly out-of-reach cornerstones, such as secure employment (Kalleberg, Reference Kalleberg2020) and homeownership (Hoolachan et al., Reference Hoolachan, McKee, Moore and Soaita2017). The ability to reach one’s aspirations is placed firmly on the individual and not the state, thus placing failure on the former.

This neoliberal pressure to ‘continually project oneself into the future, the commitment to perpetual improvement, and the requirement for self-assessment for personal lack’, is what Vassallo (Reference Vassallo2020: 18) argues underpins educational policies which tackle social inequalities in late capitalist societies. Moreover, the contemporary political obsession with social mobility (Lawler and Payne, Reference Lawler, Payne, Lawler and Payne2018: 6) is linked to this psychological concept of a growth mindset, where disadvantaged groups are conditioned to be malleable and continually strive for self-improvement.

Young people and welfare conditionality

Conditionality is fundamental to the design of most contemporary advanced capitalist social security systems (Watts and Fitzpatrick, Reference Watts and Fitzpatrick2018: 2). It comes in different forms, but primarily it is behavioural conditions upon which social security recipients must comply to access and continue to receive pecuniary state support (ibid). Non-compliance with these conditions is met with threat or application of financial sanctions on the claim (Fletcher and Wright, Reference Fletcher and Wright2018). Evidence from the WelCond Project demonstrated that ‘benefit sanctions do little to enhance people’s motivation to prepare for, seek, or enter paid work’ (Dwyer et al., Reference Dwyer2018: 4).

Framing the problem of unemployment in these terms is predicated on the grounds that those who are on the fringes of the formal labour market are inherently flawed and lack the character traits that those in stable employment supposedly possess, such as motivation and resilience (Friedli and Stearn, Reference Friedli and Stearn2015). The concept of libertarian paternalism (Gane, Reference Gane2021) is again useful to understand how welfare conditionality functions to emphasise the personal deficits of service users, while downplaying structural barriers.

The recent social security reforms in the UK have culminated in the most stringent conditionality and highest benefit sanction rates in its history (Wright et al., Reference Wright, Fletcher and Stewart2020). Under the Coalition Government’s (2010–2015) flagship policy, Universal Credit (UC) recipients are expected to meet with their work coaches at the Jobcentre Plus once every two weeks, prove they have completed thirty-five hours of job search per week, or risk being sanctioned (DWP, 2010). Recipients can also be sanctioned for not applying for an available job (even if they do not meet the requirements), being made redundant, or voluntarily leaving a job (ibid).

The data that generated the subsequent findings of this paper largely predated the rollout of UC, most of the interviews took place between 2014 and 2017; therefore, most of the young people in the sample were claiming the out-of- work support, which preceded UC: Jobseekers Allowance (JSA). However, the behavioural conditions attached to the claim were largely similar to what they are now under UC, thus the majority of the young people had to abide by the behavioural conditions detailed above to receive the age restricted JSA rate, which in 2015 was fifity seven pounds and ninety pence per week (DWP, 2015).

Moreover, youth unemployment is recognised by the state as more problematic and less deserving of financial support (Boland and Griffin, Reference Boland and Griffin2022: 55), the UC monthly standard allowance for a single person under twenty five is £265.31 compared to £334.91 for over twenty-fives (UK Government, nd). Furthermore, young people disproportionately experience the penal aspects of state support, for instance, from November 2012 to December 2016 white males aged eighteen to twenty-four were 98 per cent more likely to be sanctioned than white males aged twenty-five to forty-nine (De Vries et al., Reference De Vries, Reeves and Baumberg Geiger2017). Evidence suggests that intensified conditionality in the form of benefit sanctions lead the average claimant to exit less quickly to Pay as You Earn (PAYE) earnings (DWP, 2023), meaning employees who earn more than £242 per week (UK Government, 2023).

The disciplining of marginalised groups by the state is not a new phenomenon. However, the centrality of welfare conditionality in the UK is symbolic of a new behaviourist policy landscape (Dwyer and Wright, Reference Dwyer and Wright2014) and the continued push toward supposed self-empowering ideologies inherent within libertarian paternalism. This turn is an example of a broader trend in advanced capitalist societies psychologising structural problems (Charter and Loewenstein, Reference Charter and Loewenstein2021), such as youth underemployment (McPherson, 2021). The result is a common-sense narrative in mainstream public policy that behaviour change in the individual (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Pykett and Whitehead2013), and instilling resilience in marginalised young people (Davidson and Carlin, Reference Davidson and Carlin2019) is the most effective method of tackling poverty.

Methodology

Background of original study

The WelCond Project (2013–2019), was a large ESRC-funded UK-wide, longitudinal, qualitative study, which sought to better understand the lived experiences of welfare conditionality over time. The original sample included a total of 481 participants and 1,081 semi-structured interviews across three waves. The participants represented a range of specific groups who claimed some form of state support. These nine groups included: ex-offenders, disabled persons, lone parents, homeless individuals, jobseekers, social tenants, those with a history of anti-social behaviour, migrants, and Universal Credit (UC) claimants. Each group were recruited separately according to policy-specific criteria; however, young people were not separately sampled. The two key research questions of the original study were: (1) How effective is conditionality in changing the behaviour of those receiving welfare benefits and services? and (2) Are there any particular circumstances in which the use of conditionality may, or may not be, justifiable?

Youth sub-sample

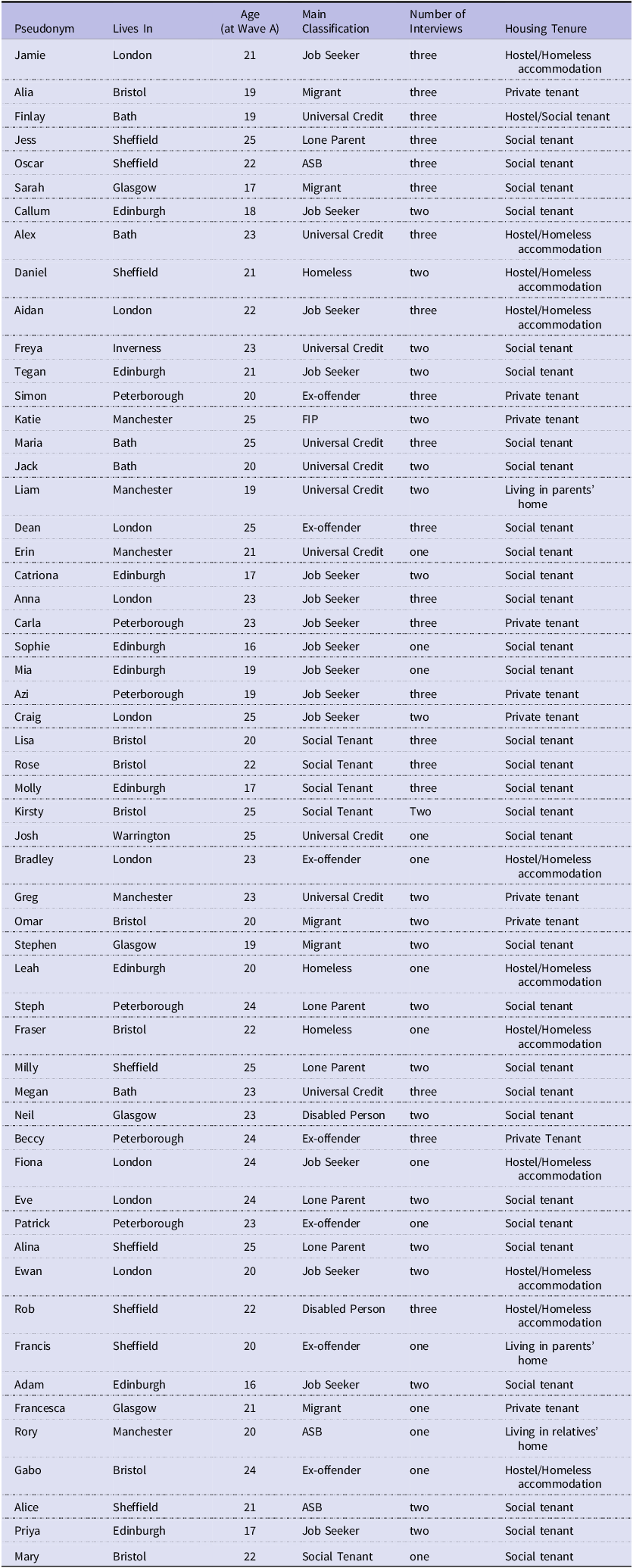

I was fortunate to be granted access to the full dataset with ethical approval from the University of York, via the primary research team. This secondary study was approved by the University of Glasgow College of Social Sciences Ethics Committee. The anonymised dataset is available via the University of Leeds Timescapes websiteFootnote 1 . This article draws upon a sub-sample of the original study, working with only the transcripts of those aged sixteen to twenty-five when they entered the study (Wave A interview). This sub-sample consisted of fifty-six young people from various policy-specific groups and a total of 114 interview transcripts across three waves. See appendix 1 for key categorical information of the full youth sub-sample.

Analytical and theoretical approach

The subsequent findings were generated through an innovative methodological approach: secondary analysis of qualitative longitudinal data. I sought to generate new theory emerging from the data, adopting an indictive approach to enable the young people to guide the analysis. The re-use of qualitative data has gained traction in recent years (Tarrant and Hughes, Reference Tarrant and Hughes2019), and given the abundance of rich qualitative datasets, such as the WelCond Project, there is ample scope for adjusting the lens of enquiry and re-analysis.

Hence, distance from the original data collection for a secondary researcher should not be perceived as a disadvantaged standpoint, because varying degrees of distance are inevitable for all researchers (Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Hughes and Tarrant2022). This does not mean however that one can simply jump into a dataset and take from it at will. It is a long and arduous process of re-contextualising and reconnecting with the primary data (Davidson et al., Reference Davidson, Edwards, Jamieson and Weller2019). In my own case, a careful process of familiarising myself with the dataset took place, through developing participant profiles, generating tables, word clouds, and coding on NVivo to identify types of response, before developing techniques of building rapport and empathy at a distance, with only words on paper to acquaint myself with, and unveil, the young people’s narratives.

I employed the use of in-depth narratives of a few young people rather than trying to include as many voices from the fifty-six participants as possible. Adapting the approach of Lulle and King (Reference Lulle and Russell2016), who used in-depth case studies to explore the experiences of ageing among female migrants in the UK, I have selected three young people so that their stories to be set out in more detail and allow individuals’ personality and biography to be a part of the analysis. Whilst I cannot claim that these case studies of internalised individualism are wholly representative, they are ‘emblematic cases’ (Tarrant and Hughes, Reference Tarrant and Hughes2019: 543) of the wider sample, that enable in- depth exploration of the concept. I aspire to combine insight and richness in the data, particularly insofar as it responds to my key research aims of illuminating subjective youth narratives of behavioural state support.

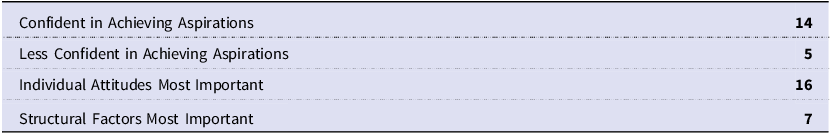

Table 1 provides an indication of the strength of internalised individualism across the sample. Participants tended to be confident that their aspiration for the following year would be met and on the twenty-three participants who were asked what could help them meet their aspirations for the year at Wave A, sixteen offered insights such as intrinsic motivation or work ethic, whereas the other seven participants suggested things such as more support, or job availability.

Table 1 Internalised individualism across the sample at Wave A

One possible limitation of conceptualising this cohorts’ narratives through internalised individualism is the potential for socially desirable responses from young people. Given the power dynamic between the researcher and the young person in these interviews is given the age and status of both the young person and the typically older academic, the young people may have favoured, or felt pressured, to express their narratives and attitudes in line with the policy framework. However, the primary research team made every precaution possible to reduce the likelihood of socially desirable responses through building rapport with the young people over time.

Findings

Freya (two interviews in 2014 and 2015)

It is 2014, Freya is twenty-three and is actively looking for work. She is living by herself in socially rented housing. Freya has no income and relies on JSA payments; however, she is carrying out unpaid care work and other work experience. She enjoys these activities and is motivated to enhance her CV and skills. Freya is confident in tying down a career:

So, I needed to work out what I wanted to do and what my strengths were […] I know I’m good at hairdressing, and that’s my career, that’s my career goal. I want to do better than I am. I really want to do better. I feel that I can, because I want to. (Freya, Wave A, twenty three, White British, Jobseeker, 2014)

This dialogue provides a sense of Freya’s approach and values. She believes she needs to fit the mould of the young professional through self-improvement and self- actualisation. This conceptualisation is intertwined with the ideology of recent UK youth policy interventions (Chapman, Reference Chapman, Lawler and Payne2018: 141). Freya is eager to abide by the conditionality attached to her claim and adopts the eternally positive and resilient self, espoused by the contemporary motivational discourse. Here, she discusses the thirty-five-hour a week job search, deemed unrealistic by many of the cohort:

Yes. I think, to be honest, it’s a tiny amount. It really is a tiny amount. It may seem a lot, but if you think about it there’s twenty four hours in a day, so if you look at it that way it’s like you’ve got plenty of time.

Freya is echoing the ‘Girlboss’ trend which has become popularised on social media (Fradley, Reference Fradley, Atay and Ashlock2022: 15), epitomised by the infamous comments of reality TV star turned entrepreneur, Molly Mae, who said in an interview for the Diary of a CEO podcast in 2021, ‘we all have the same twenty four hours in a day […] if you want it, you can achieve it.’ This psychological interpretation of unemployment is internalised strongly by Freya, as she implies that the only thing holding her back is herself. Freya has taken on board-intensified conditionality and accepts intrusive behavioural regulation. She believes that stable employment is lying in wait if one demonstrates the ‘right’ attitudes and approach, and thus alings with the confident, entrepreneurial workaholic revered within contemporary feminist culture (Gill and Orgad, Reference Gill and Ograd2017).

Her main aspiration for the coming year is to secure a job, a goal she shares with the vast majority of the cohort. She is asked what could help make it more likely that she will realise her employment aspirations:

Being prepared. Doing everything that I can in order to prepare, from having a decent meal to enough sleep, hydrated, paperwork, and all the rest of it. Well, preparation for myself, with college I mean, and being dedicated as well to stay on that path of hard work and keep on going. Even when you feel down and low and that, you’ve still got to keep on going. Sometimes it’s better when you’re feeling low to just take a wee bit of time out to recover and that, so that you can do a good job, an even better job; that’s what I find sometimes in life.

Freya’s psychological framing is central to her narrative. Services like the Jobcentre Plus, but also the contemporary cultural magnetism toward the power of positive thinking and intrinsic motivation across a range of institutions (Ehrenreich, Reference Ehrenreich2009: 4), present Freya with a lure of quality employment and a brighter future, all she has to do is believe and endeavour without relent. The evidence suggests youth transitions in contemporary Britain have been re-structured to the point where it has become increasingly difficult for young people to realise secure employment pathways, even for those who are highly qualified and motivated (Furlong et al., Reference Furlong, Goodwin, O’Connor, Hadfield, Lowden and Plugor2017: 20).

Wave B

More than a year later in 2016, Freya is interviewed for a second time and her beliefs in individualism have strengthened. During the past year, she has been diagnosed with borderline personality disorder, and she remarks having a degrading employment experience; she was cleaning toilets at a supermarket for a subcontracted company, and her manager was belittling her. Freya does not have this job at the time of Wave B interview. Freya demonstrates remarkable resilience given all the challenges she faces. When she was asked if she felt she was in a better place twelve months on from her Wave A interview, she responds:

I’m learning the importance of money, managing money. How important it is to pay your rent, and your debts and your bills, and you know, to be self-reliant. So yes, better and I feel better for it. Unfortunately, because of my last job it’s made me feel – kind of lost confidence. But what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. (Freya, Wave B, twenty four, White British, Jobseeker, 2015)

Here is an embodiment of the middle-class neoliberal subject; Pimlott-Wilson (Reference Pimlott-Wilson2017) suggests disadvantaged youth cohorts are conditioned by the state to conform to the notion of gaining satisfaction from paying the bills. Moreover, Freya personifies the resilient post-Fordist worker, where setbacks are reframed as character building and enthusiasm for future opportunities to cultivate self-identity through work (Farrugia, Reference Farrugia2020).

Despite Freya embodying the endorsed meritocratic values and self-improvement discourse, she fails to reap the rewards associated with conforming to these behaviours and attitudes. She remains pedalling between low-pay and no-pay, she is being degraded at work and is dissatisfied with her current circumstances, even though she is doing all the things asked of her. There is a discrepancy between what young people like Freya are told this behavioural mantra will deliver and their experiences in the real world. This calls into question the legitimacy of such tactics to nudge young people into work. Freya offers her aspirations for the next year, again notice how her own ability to stimulate improved well-being or control negative thoughts is central to her ability to procure full-time work:

Well, I want to be working full-time, and I want to have more of an idea how to help and control my emotions, and my feelings and my general mental wellbeing […] I want eventually to be working full-time. Being more self-reliant, like not relying on benefits for money.

Freya largely avoids focusing on the structural barriers she faces which could be shaping her well-being and labour market opportunities. She is hesitant to talk of augmented support from the state or other services to help her realise stable employment, or a more secure existence with less stress, and instead focuses exclusively on herself, internally.

Azi (three interviews in 2015, 2016, and 2017)

At Wave A, Azi was living with his brother after moving to the UK from Nigeria the previous year. Although officially it was not possible to claim JSA whilst being in full-time education at the time, according to the transcripts Azi was in receipt of JSA despite studying business full-time at a local college. This is one of the limitations of secondary analysis, not being able to cross reference information that was not clear or unchallenged in the interview. When Azi first arrived in the UK, he found it challenging to understand the system and how to navigate welfare conditionality. He was sanctioned once near the beginning of his claim because he confused his sign-on dates.

Azi accepts this form of behavioural regulation and reiterates the ideology espoused from the Jobcentre. Research from Fletcher and Redman (Reference Fletcher and Redman2022) also argued that social security beneficiaries are likely to accept the punitive design and suggest benefit sanctions are necessary for ‘other’ beneficiaries. Azi talks of going over and above the job search requirements, despite being in full-time education, just to prove to his advisor how motivated he is to comply and to find work. He emphasises throughout his narrative the importance of positive mindset and individual psychological management are to him, and his ability to realise his lofty employment aspirations. Here are his aspirations at Wave A, he is confident and psychologises the barriers to his future employment:

This time next year I hope I’ve got in a job already, I’m hoping […] I should have got a good job and again, adhered to my business plan exactly, I pray that my business plan should be come into existence. So yes, that’s what I’m hoping. (Azi, Wave A, nineteen, Black Nigerian, Jobseeker, 2014)

Interviewer

Do you have any barriers in your way of getting your aspirations and your dreams? Is there anything holding you back or any obstacles?

Azi

Yes, I would say I am sort of a negative thinker. I used to think I can’t do this, I can’t achieve this, I can’t make it. Which I could.

The psychological turn inherent within recent UK social security reforms (Friedli and Stearn, Reference Friedli and Stearn2015) can be seen playing out in the psyche and values articulated by the young people from this cohort, and more strongly in Azi’s case. He has transitioned from a non-believer into a believer, in the sense he demonstrates unwavering belief in realising his employment aspirations and this mentality will propel him to economic security.

Wave B

The following year Azi is completing his college course. He has had some temporary paid work and other work experience since Wave A. He worked in a warehouse during the Christmas period, but he did not meet his productivity target, so he was laid off. He discusses how the paid work affected his attendance and performance at college because he was working long hours and how he managed this challenge:

I think I just endured it; I had the endurance, I had that strength to just handle it because if I say I’m going to quit along the line, my rent just reminds me that I’ve got a debt of £1000 to pay. (Azi, Wave B, twenty, Black Nigerian, Jobseeker, 2016)

Azi embodies the idealised post-Fordist worker (Farrugia, Reference Farrugia2019), one who endeavours through insecure and low-wage labour driven by anxiety and determination to pay increasingly larger portions of their wage on rent. This idea of enduring the competing demands of his labour and his study were also indicative of Azi’s internalised individualism, he is committed to overcoming economic challenges, such as rent arrears, by being mentally resilient.

This is something Davidson and Carlin (Reference Davidson and Carlin2019) have argued, the idea that youth focused social policies seek to stimulate resilience among disadvantaged young people to foster individual acceptance of adversity, rather than seeking to address wider social inequalities. Reflecting on his sanction experience, Azi is one of the few from the study to suggest their own sanction experience had a positive impact. He adopts a strong notion of self-responsibility and suggests that young people who reflect on their sanctions internally, as he did, will learn and benefit long-term from financial punishment:

Let me say some people, once they’re sanctioned, they’re like, ‘Oh, I’m sanctioned. This Jobcentre don’t know what they’re doing. Why did they sanction me? They’re too mean,’ and all that, but they didn’t think back, oh, what have I done wrong? Let me look at my own side to see why they sanctioned me, that kind of thing.

This understanding of benefit sanctions gives us insight into how Azi perceives the system and his role in the system. He is committed to the system despite being punished. Azi’s aspirations are to go to university in the next year. His sights are set on continuing his business studies to Bachelor level:

Hopefully I should be in my university and should be trying to get my degree.

Interviewer

Is there anything standing in your way of achieving your goals?

Azi

Apart from financial issues I have sometimes, nothing else; it’s fine, no, because that’s the only challegne I face.

He understands that if he believes and strives, future valorised employment will materialise. However, he is yet to realise his aspirations of entering an undergraduate degree and then valorised employment. Azi’s intersectionality as a young black migrant presents him with greater barriers to secure employment when compared with the white nationals from the study.

Wave C

Azi has now finished his college course and is still set on going to university. He has been working full-time at a hardware store for over a year now and is still trying to work out how he will afford the degree he is eager to pursue. He again adopts this individualised, human capital, and optimistic outlook towards his decision to pursue higher education. He believes his degree will inevitably lead to expansive employment opportunities; another expectation that recent generations of young people are encouraged to assume but are increasingly faced with heightened competition and demand-side shortages (Bathmaker et al., Reference Bathmaker, Ingram, Abrahams, Hoare, Waller and Bradley2017: 5), especially among socially disadvantaged graduates (Formby, Reference Formby2017). Azi details his reasoning behind pursuing an undergraduate degree in business and marketing.

I just thought that if I have a degree, I could be able to work anywhere, any company and stuff like that, so I was thinking it’s worth me going to uni. I’ll have a degree and no doubt I can, obviously, get employment anywhere. (Azi, twenty one, Wave C, Jobseeker, Black Nigerian, 2017)

Azi has consistently internalised the individualised model for progress and success in the labour market and managed to enter and maintain paid work. He understands that if he believes and strives, future valorised employment will materialise. However, he is yet to realise his aspirations of entering an undergraduate degree and subsequent high-wage employment. Azi, to a lesser extent than Freya, has been somewhat betrayed by internalised individualism, as a university degree appears out of reach due to lack of financial support.

Mia (one interview in 2014)

Mia is the final narrative to demonstrate how internalised individualism plays out in the lives of young people and how young people who experience welfare conditionality conceptualise their future aspirations. Mia left the study after one interview; thus, the longitudinal aspect is absent from her narrative. However, her story provides further insight into the perceived empowerment of adopting the behavioural approach to labour market activation.

Mia was a nineteen-year-old jobseeker living by herself in social housing. She had been cut off from her family, emotionally and financially. Mia had worked in a hair salon, but her hours had been continually cut and eventually she had to claim JSA. She had recently received a four-week sanction for not informing the Jobcentre that she had finished a training course, for which she was receiving employability fundFootnote 2 instead of JSA.

Mia is asked how confident she is in finding work. She remains confident despite many non-response or rejections from the numerous applications she has made. She believes she is doing all she can to secure employment:

I’m confident but I still don’t think I have the experience that I need. I have had three years’ experience in a hair salon. I’ve had experience in a nursery when I was younger […] I’ve genuinely been looking since February and no-one wants me, no temp jobs, no part-time jobs […] it’s not even like I’m lazy and I’m not looking, because I want to work. (Mia, nineteen, Wave A, Jobseeker, White British, 2014)

The restricted and insecure labour market opportunities available to Mia are clear to see. She is, however, obfuscated from understanding this as an external problem and perceives this as an I problem, as encouraged by the penal social security system she engages with. Mia, just as with Freya and Azi, and many others from the study, are blind to the structural components at play and make sense of their employment experiences as an individual pursuit, where opportunity can be generated through observing and performing the ‘correct’ behaviours and mentality.

Questioning the principles of welfare conditionality has become more difficult for this generation who have grown up with behavioural economics dominating multiple aspects of life and thus, begin to perceive these practices as inevitable or justifiable (Pykett, Reference Pykett2013; Fletcher and Redman, Reference Fletcher and Redman2022). A welfare common sense (Jensen, Reference Jensen2014) has been crafted for this cohort of young people; harsh benefit sanctions appear inevitable because this type of approach is all they have known. Mia’s employment aspirations for the following year are as follows:

I’ll be employed and trained as a full-qualified hairdresser and have money to spend in my pockets really, just be happier because at such a young age I don’t want to be constantly in this shitty frame of mind. I’ve got no money. This is stressful. This is depressing.

Interviewer

Do you expect that you’ll be able to achieve that in a year?

Mia

Yes 100 per cent.

Interviewer

What would make it more likely or what would make it less likely?

Mia

Well, I don’t know it’s down to my motivation. There’s nothing really going to stop me at all […] because it’s definitely what I’m going to do.

This dialogue illustrates precisely the concept of internalised individualism; Mia understands her mental strength to be the defining element in her pursuit of secure employment. A young woman, who is unhappy with her situation, is angry with how the Jobcentre is treating her, is stressed about her lack of income and stability, but is restrained from looking outward and contextualising her experiences within the context of economic recessions, rising precarity, austerity, and the intensification of welfare conditionality with limited informal support.

Discussion

The concept of internalised individualism is used to contextualise how young people from this cohort tend to self-blame even when they are repeatedly excluded from secure employment opportunities. They adopt the language of pop psychology, reiterating aphorisms such as ‘it is up to me’ and ‘nothing can stop me’. There is a meeting here between broader trends in self-help culture, nudge theory (Thaler and Sunstein, Reference Thaler and Sunstein2008), and welfare conditionality (Friedli and Stearn, Reference Friedli and Stearn2015), where these young people are swept up in a coalescence of individualism and are instructed to understand their unemployment or underemployment as something to be fixed within themselves. They are conditioned to believe that if they embody the traits which those who succeed in the labour market supposedly display, such as motivation, belief, and resilience, they too could realise valorised employment. However, these young people largely fail to realise the rewards associated with conforming to the self-improvement discourses, such as stable employment. This advances the findings of García-Sierra (Reference García-Sierra2023), who argues that young people from low socioeconomic backgrounds who believe in meritocratic values are more likely to experience precarious employment when they are adults.

Internalised individualism builds upon research from Shildrick and Macdonald (Reference Shildrick and MacDonald2013), as they argue that those who experience poverty tend to conceptualise the causes of poverty as stemming from the individual traits of the poor. Othering of benefit recipients by fellow benefit recipients (Patrick, Reference Patrick2016; Fletcher and Redman, Reference Fletcher and Redman2022) is used as a protective tool to distance oneself from other marginalised identities as solidarity among working-class groups is increasingly undermined. However, internalised individualism, rather than stemming from a social or political pressure to dissociate from stigmatised groups and the protection of one’s own identity, conceptualises the individualisation embodied by this cohort of young people as a self-responsibilising and emancipating response to poverty within the pervasive, empowering culture of self-help.

This paper argues that libertarian paternalism has become influential across social policy circles within neoliberal societies (Gane, Reference Gane2021), whereby a form of ‘soft’ paternalism is exerted by the state to nudge individuals to make ‘better’ consumer and lifestyle choices. Thus, forms of self-governance can can be experienced or accepted by a range of actors and groups, and young people on the margins of the paid labour market appear susceptible to buying into the key principles. This is a neoliberal trend (Türken et al., Reference Türken, Nafstad, Blakar and Reon2016), but I argue internalised individualism is saying something profound about recent generations of young people.

The culture and specific social trends which were emerging and solidifying during the formative years of this youth cohort (those born after 1990), such as an increasingly individualised education system focused on employability at a young age (Reay, Reference Reay2021), organisational practices of bolstering resilience to combat gendered inequalities (Witmer, Reference Witmer2019), social media entrepreneurship and life coaches (Gill and Ograd, Reference Gill and Ograd2017), positive psychology governance (Binkley, Reference Binkley2011), the self as a brand (Khamis et al., Reference Khamis, Ang and Welling2017), and social policies that seek individual behaviour change to combat social challenges (Charter and Loewenstein, Reference Charter and Loewenstein2021) have shaped young people’s experiences and attitudes to work and adulthood more fully and deeply when compared to previous generations.

Contemporary UK social security policies encourage young people from working-class backgrounds to assimilate middle-class values, such as conforming to the neoliberal ideals of realising citizenship and self-worth through paid work and wealth accumulation (Pimlott-Wilson, Reference Pimlott-Wilson2017). These young people are pressured to strive for exponential social mobility through replicating the isolated individual cases of those who came from working-class backgrounds and managed to realise a middle-class adulthood (Folkes, Reference Folkes2021).

For Millennials the prioritisation of individualism over collectivism from a young age was more pronounced than among previous generations (Littler, Reference Littler2017: 49; Raey, 2021). What specialised qualities does one possess? How does one stand out in an application process? These are questions that have been at the centre of schooling and the socialisation of recent generations of young people (Reay, Reference Reay2020), as they prepare to compete in the highly stratified contemporary labour market. External factors, such as insecure labour markets and socio-economic inequalities, become less important when one’s ability to navigate contemporary labour and housing markets is perceived as primarily a consequence of meritocratic hierarchies (Littler, Reference Littler2017: 2) or the power of self-belief (Raey, 2020).

This conceptualisation of economic outcomes not only individualises the problem of un/underemployment by minimising structural barriers and promoting human capital as the dictator of improved outcomes, it pathologises the problem (Vassallo, Reference Vassallo2020: 36). The self-help discourse informs disadvantaged young people that their subordinated social position is, in part, because of individual psychological deficiencies. The young people from this study mostly embody the positive entrepreneurial self, but their labour markets outcomes remain plagued with low-pay, insecurity, and their aspirations frustrated.

There are certainly aspects of psychological traits that shape labour market trajectories, such as confidence and motivation, however evidence suggest there is only so far mindset and investment in the self can take those who face multiple structural barriers (O’Brien et al., Reference O’Brien, Laurison, Miles and Friedman2016; Abrahams, Reference Abrahams2017). To enable some of the more marginalised young people in our society to individualise and psychologise labour market outcomes may seem to some as a means of giving hope to disadvantaged young people. However, this paper argues this approach avoids what could be the central policy focus; re-structuring external factors, away from the young person’s behaviour, to enable them to have more agency over their lives and realise more secure futures.

Conclusions

This paper has developed the concept of internalised individualism that was generated through secondary analysis of cohort of young people (n=fifty-six), who all claimed some form of state support in the UK. The term internalised individualism refers to the tendency for this cohortto favour individualised and psychological pathways to realising their own labour market aspirations. This strong theme within the data was illustrated in this paper via three in-depth narratives of young people who characterise this conceptualisation of future employment aspirations.

The analysis has explored how the psychological conceptualisation of employment can permeate the psyche of young people who encounter welfare conditionality, and the subsequent impacts. The paper has also illuminated the dichotomy between young people conforming to endorsed meritocratic values and self-improvement discourses, and their experiences of welfare conditionality and the labour market, as they largely remain in poverty and are betrayed by the adoption of such values.

The individualised conceptualisation of employment and unemployment has potential long- term scarring effects (Egdell and Beck, Reference Egdell and Beck2020) for these young people and similar cohorts, as they are pressurised to transition to the increasingly elusive traditional cornerstones of adulthood (Chesters and Wyn, Reference Chesters and Wyn2019), are excluded from valorised and secure employment pathways (Furlong et al., Reference Furlong, Goodwin, O’Connor, Hadfield, Lowden and Plugor2017: 20), and then understand these lacks as an individual flaw. The detrimental impacts on well-being over time are evident as self-blame could exacerbate mental health problems associated with low-income and unemployment. Future research should seek to identify the generalisability of internalised individualism among youth cohorts who experience welfare conditionality.

Beyond addressing the wider structural inequalities faced by contmeporary cohorts of young people, there are some policy reforms that could help to improve well-being for those claiming state support whilst out-of-work and make it more likely they transition to a more secure adulthood. Firstly, given the unique generational inequalities faced by young people transitioning to adulthood in contemporary society, tailored support for young people beyond the contemporary standardised out-of-work support is essential. Rather than restricting access to financial support for young people and disproportionately punishing them, the system should seek to provide augmented unconditional support for young people, both financially and with specific non-mandatory youth training initiatives available.

Treating young people with dignity from the outset, like adults, will help foster a stronger cohesion between young people, state services, and the labour market. Instead of taking the current approach, of cracking down early and heavily on young benefit claimants to intimidate and coerce them to enter the insecure labour market with limited support, a long-term approach to support young workers is required. Their relationship and understanding of work, as well as their experience of the contemporary labour market and the skills desired contrast compared with previous generations. Therefore, bespoke training and support for young jobseekers should be developed in collaboration with young people. They are the future of the workforce and instructing disadvantaged young people to fix structural problems individually is ineffective and carries potential long-term harms.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank all of the young people who took part in the Welfare Conditionality Project and to the primary research team for all their endeavours and for enabling re-use of the dataset. I would also like to thank Dr. Jamie Redman, Dr. Annie Irvine, and Dr. Anna Gawlewicz for their feedback on earlier drafts of this article, and to the anonymous reviewers for their engagement with my work and recommendations. Finally, I would like to thank my PhD supervisors, Prof. Sharon Wright and Dr. Mark Wong, for all their support in making this article possible.

Funding statement

This research was part of my ESRC-funded PhD project, ES/P000681/1.

Appendix 1. Full Youth Sample Information

ASB = history of anti-social behaviour orders; FIP = Family Intervention Programme.