1. Introduction

On July 16, 2015, when showman Donald J. Trump rode down the golden escalator to denounce Hispanic immigrants as “rapists” and drug dealers as he declared his candidacy for the GOP presidential nomination, the moment dramatized how far many Republicans had traveled since 1980. Back then, GOP presidential contenders sparred over whose approach to immigration was more humane and business friendly. In their April 1980 debate, Ronald Reagan declared that reforms should not center around “putting up a fence,” while George H. W. Bush called for measures “so sensitive and so understanding about labor needs and human needs.”Footnote 1

In recent decades, in fact, not just Republicans, but Democrats as well, have changed their previous stances on immigration issues. Democratic Party leaders once worried that newcomers would undercut union jobs, but now they have overwhelmingly converged on support for expanded admissions and new benefits and rights for immigrants, including providing pathways to citizenship for many undocumented migrants. Meanwhile, GOP turnarounds have been sharper and continue apace. A party that not long ago catered to business desires for immigrant workers now stokes and responds to popular fears about non-European and especially Hispanic newcomers. The 2018 midterm elections featured alarmist GOP depictions of supposedly dangerous Central Americans arriving in massive “caravans” to “invade” across a U.S. southern border misleadingly described as “open”; President Trump’s 2020 reelection bid doubled down on promises to finish “The Wall.” Since then, similarly harsh GOP efforts have intensified. The Republican governor of Texas is spending billions of taxpayer dollars to “finish” the Trumpian wall, while Florida governor and GOP presidential aspirant Ron DeSantis looks for ever more telegenic ways to ship batches of migrants from the southern border to liberal locales in the Northeast.

This article aims to bring public agendas about immigration enforcement and the treatment of migrants into ongoing scholarship about processes of U.S. party polarization and GOP radicalization. The following sections first situate our study in relation to previous kindred work that has, puzzlingly, tended to downplay immigration clashes and then outline how we use data on national and state-level Democratic and Republican political party platforms to describe and begin to explain party polarization in this realm. What can platform contents over the years from 1980 to 2017 tell us about when each major party started paying more attention to immigration matters, and when and how party stances changed? Have Democrats and Republicans moved in tandem or on separate trajectories? Did national party agenda setters move first, or did state platform writers lead the way? Among state parties, which ones moved first?

After we lay out such patterns, we probe the plausibility of several causal forces invoked in accounts of immigration politicization. Full causal tests are not the objective of this article, but our descriptive findings point to promising lines for further analysis. At the elite level, polarization may have been spurred by shifts in major-party-aligned interest groups and repeated breakdowns in high-profile efforts to forge congressional compromises. In addition, polarization was likely spurred by widespread social protest movements—including nationwide pro-immigrant demonstrations in the spring of 2006 and Tea Party protests and organizing starting in 2009. In fact, the temporal evidence that we track here produces a key finding about the Tea Party. Although previous research has shown that grassroots Tea Party activists were often animated by anger about immigration, this movement was not the original cause of GOP shifts toward restrictionist stances, which were proliferating in GOP platforms from 2002 on. The Tea Party is better understood as an intervening factor, both an expression and accelerator of the Republican turn away from business-friendly immigration stances and toward ever more full-throated ethnonationalism.

At the end of this article, we briefly situate our findings about immigration polarization in relation to previous findings by sets of scholars who have also mined state and national party platforms to track social-regulatory divergences. Democratic versus Republican splits on racial equity issues since the 1960s, on family and gender matters since the late 1970s, and on immigration in the 2000s have by now layered one atop the other—and the results, we suggest, may be more than simply additive. Interactions among these processes of intense polarization about social-regulatory issues cry out for further empirical and theoretical explorations, because the interactions may have fueled a supercharged synthesis. With elites, activists, and many ordinary voters now sharply divided on multiple sets of social-regulatory issues, even as they also disagree more fiercely than ever about many aspects of government’s role in the market economy, America’s two major political parties seem increasingly locked into existential clashes over the very meaning of U.S. nationhood. The layering and interaction of so many initially distinct lines of disagreement over fundamental societal issues may explain why U.S. politics today seems increasingly mired in irresolvable “us” versus “them” conflicts and teeters frighteningly close to a fundamental breakdown of shared liberal-democratic practices.

2. Why Immigration Should Be More Prominent in Research on Party Polarization

Many analysts of contemporary U.S. party polarization and Republican Party radicalization recognize that these transformations are grounded in diverging views of what government should do about the standing and rights of various societal groups, beyond long-standing left-right debates about government’s role in the economy.Footnote 2 Understanding party polarization and agenda shifts requires looking over long periods of time and finding credible measures of the content of changing party agendas, to lay the groundwork for exploring factors that propel party shifts and polarization. Numerous scholars have taken up these challenges. Initial studies of U.S. party polarization probed the 1960s to the 1980s and stressed the regional reordering of voting blocs, advocacy groups, and party agendas that played out in the aftermath of the mid-twentieth-century civil rights movement.Footnote 3 Thereafter came an era of persistent and ultimately pervasive asymmetric polarization—in which Republicans from the late 1970s moved ever further to the right on many issues, shifting well beyond the preferences of “median voters” no matter whether they won or lost elections. To make sense of those developments, scholars have probed both elite and popular vectors—but immigration has not been front and center in either sort of study.

Scholars examining the role of elites have used longitudinal evidence about shifts in institutional functioning, organizational arrays, and business and ultra-wealthy political organizations to help explain why the Republican Party has moved toward often extreme, unpopular anti-government positions about taxes and government regulation of the economy.Footnote 4 Political fights about race, reproduction, and family forms have not figured much in such analyses—perhaps because the U.S. business associations and wealthy donors stressed in these studies highlight economic rather than social policies.

Meanwhile, researchers considering popular factors have used survey-based and ethnographic methodologies to investigate voter outlooks and social movements that may have encouraged shifting party stances. Many studies conclude that tradition-minded voters and community-based Christian right networks have prodded conservative politicians to restrict abortion and LGBTQ rights and push back against civil rights gains.Footnote 5 Some chronologically detailed studies pinpoint exactly when, from the 1970s on, Republican Party leaders, nudged by shifting constituencies, repudiated earlier moderate stands on issues ranging from civil rights enforcement to gun regulations to women’s rights and access to abortion.Footnote 6 Nevertheless, immigration and government stances toward migrants have been largely omitted from these bodies of work on causes of polarization and radicalization. This is quite puzzling. In the words of Zoltan Hajnal, one of the few political scientists who has looked closely at political reverberations of immigration, over “the past half-century 60 million new souls have joined the American experiment. Latinos now outnumber Blacks. Asian Americans are gaining fast. The reality is that immigration may not just be altering the U.S. population, it may also be altering its politics.”Footnote 7

Throughout American history, upsurges of nativist politics have always followed (albeit unevenly and with delays) earlier waves of migration—and the country is now experiencing another such nativist upsurge. New arrivals surged from the mid-1960s to around 2008, as U.S. federal policies first facilitated increased immigration and then failed to address the unintended consequences of arrivals by more than projected numbers of legal and undocumented newcomers. In 1965, the landmark Hart-Celler Act removed long-standing national-origins quotas that strongly favored immigration from northwestern Europe and, for the first time, limited the number of visas available to immigrants from countries in the Western Hemisphere. Although legislative leaders did not expect the 1965 reforms to “upset the ethnic mix of our society” (as Democratic senator Ted Kennedy put it), the removal of national-origins quotas led to greater inflows from Asia and Africa.Footnote 8 Further, limits on immigration from the Western Hemisphere raised the salience of temporary workers from Mexico and Central America, who had long engaged in patterns of circular migration to and from the United States. For the first time, undocumented immigration became a central topic of policy discussion.Footnote 9 After it became clear that arrivals were higher and from different regions than anticipated and included many undocumented job seekers, Congress and President Reagan enacted new bargains (at various points, and especially in 1986) that were supposed to combine ever-tougher border enforcement with measures to allow undocumented people already here to legalize their status and eventually become citizens. Overall, these bargains not only failed to prevent further undocumented arrivals; they actually deepened the potential impact of the culturally distinctive late twentieth-century immigrants on U.S. society as a whole.

Sociologists—above all, Douglas Massey and his colleagues—have done pathbreaking longitudinal research to spell out the effects of an increased focus on border security.Footnote 10 Repeated massive infusions of federal funds “militarized” a border that had previously allowed many short-term back-and-forth trips by Mexican men looking for work to support families back home. The new barriers did not keep undocumented people from coming—they just forced them to try multiple times, perhaps pay “coyotes” to help, and face greater risks of death by crossing desert areas away from previous urban entry points. Enforcement measures boomeranged, because as it became harder for undocumented workers to go home repeatedly for family visits in Mexico and Central America, many responded by bringing their spouses, children, and other family to the United States, moving away from high-cost areas along the southern border and settling as long-term residents in cities, towns, and states across the U.S. heartland.

These processes accelerated after the 1980s. By the early to mid-2000s, net inflows of new migrants began declining and rates of undocumented immigration fell. Nevertheless, by then, settled immigrant families, including many with undocumented members, were spread all over the United States. Federal policies had produced unforeseen outcomes, and towns and cities across the U.S. heartland were now homes to substantial clusters of immigrants speaking languages other than English. Some “new destinations” for migrant settlers were economically booming—for example, the upper South—but others were larger and smaller cities in the Midwest and East that had lost traditional well-paid unionized manufacturing jobs previously held by white native-born men. In some of these areas, low-paid, onerous jobs in industries like meatpacking recruited Hispanic immigrants.

The movement of new immigrants into the U.S. heartland did not produce one-for-one political reactions. Historically, nativist politics has usually burgeoned after, not during, increased inflows, and much depends on how politicians and local groups react.Footnote 11 Nevertheless, migrant movements from the 1960s to the early 2000s created openings in many places for anti-immigrant politicians who decided to stoke and take advantage of the resulting cultural and economic tensions in places far from the earlier immigrant portals of California, New York, and Texas.Footnote 12 In Iowa, for example, former GOP representative Steve King turned himself into an influential anti-immigrant firebrand by stoking tensions about Hispanics who came to work in meatpacking plants in his state in the 1990s.Footnote 13 Similarly, former GOP representative Lou Barletta of Hazelton, Pennsylvania, known as “Trump before Trump,” advanced his career each step of the way by decrying foreign-born Dominican newcomers as supposed sources of rising crime in his Rust Belt region.Footnote 14

In short, immigration can be a potent source of policy and political conflicts, much like changes in race relations and transformations of family structures and gender roles. Political parties and groups in their orbits have had to deal with all these major social-regulatory transformations—amid rising economic inequality and regional disparities—so political conflicts about immigration as well as these other issues need to be more explicitly included in research about shifting party agendas and growing partisan polarization.

3. Party Platforms as Indicators of Shifting Party Stands

Even though most investigations of the effects of party polarization on social-regulatory issues so far have said little about immigration, a number of recent studies demonstrate the value of political party platforms as an over-time data source. Party platforms are hammered out by party officials and associated activist constituencies every two years in most states, as well as every four years in conjunction with the national GOP and Democratic presidential nominating conventions. Some observers of U.S. politics ignore these documents on the grounds that they do not bind elected officials and are not read by most voters. However, elected officials usually do try to carry through major platform goals—whether because of ideological belief or sustained activist pressure—and many voters hear about their key provisions through the media. What is more, representatives of important organized constituencies and social movements in each party’s orbit often take a strong interest in the contents of these documents and present demands to, or sit on, committees that draft or approve platforms. When it comes to when and how issues and policy positions gain or lose visibility on public party agendas, platforms are close to an ideal source. They are public-signaling, collectively fashioned documents—and for the most part, they are produced in analogous ways again and again over years and decades. Unlike bills that come up for debate and vote (or not) at the behest of legislative leaders, issues and policy positions can be mentioned in platforms well before top party officials want them featured.

For the long run of U.S. national politics, both John Gerring and Kenneth Janda have used national platforms issued every four years to track changes in Republican and Democratic party agendas.Footnote 15 State-level party platforms have not been so readily available until recently. Because most state parties did not regularly archive these documents, it took scholars many years and much sleuthing to assemble large enough sets to enable systematic cross-state and over-time analysis. After such work, Eric Schickler and Brian Feinstein used state-level platform data to help document that the Democratic Party’s embrace of racial equality and civil rights was a gradual process that started in states as well as northern cities in the 1930s before ultimately spreading upward to national campaigns, party platforms, and presidential and congressional actions.Footnote 16 Similarly, Matthew Carr, Gerald Gamm, Justin Phillips, and Michael Auslen have worked hard to assemble even more state party platforms and used them to document that shifts toward anti-abortion and anti-LGBTQ rights stances started in the states in the 1970s, before becoming fully embraced by Ronald Reagan and the national GOP in the 1980s and afterward.Footnote 17 These previous studies, as well as the specific kinds of platform measures these scholars have used, serve as inspiration for our own coding and measurement efforts.

3.1 Data and Measurements

For the analyses we develop here, focusing on immigration stances in national and state-level platforms, we use the most extensive publicly available assemblage of national and state platforms gathered by Daniel Hopkins, Eric Schickler, and David Azizi.Footnote 18 This collection contains 735 Democratic and Republican platforms from forty-nine states during our period of interest from 1980 to 2017, along with all twenty national platforms from this period.Footnote 19 The 735 state-level platforms include 221 pairs of Democratic and Republican platforms from the same state and year between 1980 and 2017, as well as 180 unpaired Democratic platforms and 113 unpaired Republican platforms. The findings we report later in this section include all available paired and unpaired Democratic and Republican platforms since 1980.Footnote 20 A strong majority of platforms over this period—92.2 percent—were released in even years, but we assign platforms released in odd years to the previous two-year interval on the grounds that platforms are forward-looking agenda statements.

As shown in Appendix A, platform availability was modest between 1980 and 2000 but increasingly consistent after 2000, peaking from 2008 to 2012 before trailing off at the conclusion of the period.Footnote 21 Because (as we will soon show) most changes around immigration in party platforms happened from 2000 on, the spottier earlier coverage is less of a problem for this analysis than it might be for examinations of other issue areas. Appendix A also shows that platforms available to us come from a geographically broad and diverse range of states.

Focusing on national and state-level platforms’ mentions of immigration, we track two key measures: levels of attention to immigration and indicators of the content and valence of immigration references. Using these measures, we draw comparisons across all available state platforms and national platforms; we also make occasional comparisons between southwestern border states (California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas) versus all others.

‧ We measure attention as the percentage of platform words from a given year and party devoted explicitly to immigration stances.Footnote 22 Although positions indirectly relevant to immigration occur in many platform sections, we include only sentences directly referencing immigration or immigrants.Footnote 23 We use percentages instead of raw counts, because state platforms vary enormously in length and detail. Our measure is meant to capture how important immigration is across platform documents that vary considerably in length.Footnote 24

‧ To measure platforms’ policy content, we code for restrictionist and inclusionary provisions related to seven major areas of immigration policy. Summarized in Table 1, the major areas of immigration policy for which we tracked inclusionary and restrictive stances include federal authority, state and local authority, border control, the treatment of undocumented immigrants, the specific treatment of undocumented births and children, immigrant access to U.S. social policies, and immigrant incorporation. We inductively identified these seven policy areas by closely reading state and national platform sections related to immigration. We then coded the valence of each reference as restrictionist or inclusionary. After identifying references to these policy areas, we aggregated the number of inclusionary and restrictionist references in each platform, producing a count from 0 to 7. A value of 0 indicates either that a platform did not reference immigration, or that it made a vague reference to immigration without concretely addressing any of these policy areas. At the other end of the scale, platforms assigned a value of 7 make restrictionist or inclusionary references in all coded policy areas. For sets of state platforms from the same year and party, we then determine average counts. We also find values within one standard deviation of this average—bounded by 0 to 7—to indicate the spread of state party positions on immigration.

‧ Finally, to home in on recent GOP embraces of especially tough restrictionist measures, we also count the percentage of GOP platforms over time referencing three particular kinds of provisions: opposition to amnesty for undocumented immigrants, opposition to sanctuary cities and calls for local and state cooperation with federal enforcement measures, and calls to abolish or modify birthright citizenship (the long-standing constitutional understanding that children born on U.S. soil are automatically American citizens).

Table 1. Restrictionist and Inclusionary Approaches to Key Immigration Policy Issues

As we summarize our key findings about platform immigration stances in the next section, we juxtapose Democrats and Republicans to discover whether, when, and to what degree increased attention and content polarization has occurred. We likewise trace developments in national and state party platforms in order to explore whether levels of attention or polarization have been driven nationally or from the states in each major party.

3.2 When Did Republicans and Democrats Increase Attention to Immigration Issues?

These days, one need only turn on the TV news to realize that immigration issues are often front and center in party rhetoric and policy arguments. But have U.S. parties long been on high alert about immigration, or did one or both parties recently increase their attention to such issues? To help answer this question, Figure 1 uses our percentage-of-words-based measure to track shifts in attention to immigration in state and national Democratic and Republican platforms from 1980 through 2017. Setting aside for the moment a 1996 spike in attention to immigration in both the GOP and Democratic national platforms, the broad takeaway from Figure 1 is that sharp upward turns occurred around 2000 in attention to immigration in both parties’ national and state-level platforms. The changed trajectory toward much more attention is especially sharp for GOP state-level platforms after 1998. Yet increases in attention are also evident in national GOP platforms after 2000. And while the upward slopes are less sharp on the Democratic side, we also see upward turns in attention to immigration from 2002 to 2004 in both national and state-level platforms.

Figure 1. Attention to immigration in state and national Democratic and Republican Platforms, 1980–2017.

Notes: Both paired and unpaired platforms are included. Platforms released in odd years are assigned to the previous even year. Line charts track the percentage of words related to immigration in Republican and Democratic state platforms. Clustered bar plots indicate the percentage of words related to immigration in Republican and Democratic national platforms.

To understand the origins of recent trajectory changes, we dig into the early part of our period, starting with national party platforms. In the 1980s and 1990s, immigration issues received modest attention in national Democratic platforms and less attention in their GOP counterparts. Both sets of pre-2000 platforms included calls for the United States to accept refugees fleeing communist countries. However, the year 1996 saw a sharp upward spike in both Democratic and GOP national platform statements about immigration matters—coinciding with Pat Buchanan’s nativist campaign for the GOP presidential nomination. Although moderate Bob Dole eventually secured the nomination, he allowed some platform gestures toward reducing admissions and increasing enforcement, as pushed by his defeated opponent. Also in 1996, Congress hotly debated what turned out to be the last “grand compromise” immigration legislation, including provisions that sparked attention and lobbying from advocates on all sides, including business groups pushing to admit needed workers, immigrant rights advocates, and social conservatives sounding alarms about border security and undocumented “lawbreakers.” Quite likely, the same organized groups involved in the big congressional battles that year were also on high alert when the national presidential platforms were drafted; four years after the 1996 dual party peak, Democratic presidential-year national platform writers continued to address the variety of contentious issues featured in 1996.

As for state-level party platforms, both Democratic and GOP documents paid only modest attention to immigration topics in the 1980s and 1990s, and when most state-level platforms did attend to this area, they often called for federal leadership on the issue. Importantly, greater attention to immigration controversies was evident in platforms written in states abutting the southwestern border. Between 1980 and 2000, 2.0 percent of words in Democratic party platforms from California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas referenced immigration, compared to 0.7 percent in the platforms written in all other states. The gap was also present, though smaller, on the GOP side, where 0.9 percent of words in Republican party platforms in these four border states from 1980 to 2000 referenced immigration, in contrast with 0.5 percent of words in GOP platforms from all other states.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, as Figure 1 makes clear, levels of attention to immigration turned to upward trajectories in national and state-level platforms on both the Republican and Democratic sides. In Democratic platforms, increases in attention were evident at both the state and national levels, with trends moving upward roughly in tandem from 2004 to 2012. National Democratic platform attention then surged in 2016, with 4.7 percent of words in that year’s national party platform referencing immigration, compared to 2.9 percent of words in state platforms. On the GOP side, increases in attention occurred in both state and national platforms, but, notably, state-level attention to immigration surged sharply upward. In 2000, 0.6 percent of Republican state platform words related to immigration; this figure shot up to 3.9 percent and 4.6 percent by 2012 and 2014, respectively—and in both 2012 and 2014, state-level GOP attention surpassed attention to immigration in national Republican platforms. National Republican platforms also exhibited increases in attention to immigration after 2000, though the timing of national peaks was earlier. Some 1.3 percent of words in the 2000 Republican national platform dealt with immigration issues, but this share rose substantially—and ahead of state-level upticks—to reach 4.3 percent of words in 2008.

After that, attention to immigration in Republican national platforms declined in 2012 and 2016. However, we should acknowledge that Donald Trump’s 2015–16 presidential candidacy focused so spectacularly on immigration flashpoints that statements in party documents were probably superfluous. For 2016, certainly, a strong national GOP focus on immigration was there for all to see. Meanwhile, the Democratic national platform had much more to say about immigration in 2016, perhaps in response to Donald Trump’s harsh rhetoric and also because appeals about immigration reform were important for party turnout efforts in that presidential year. In the words of the preamble to the 2016 Democratic platform, the “stakes have been high in previous elections. But in 2016, the stakes can be measured in human lives—in the number of immigrants who would be torn from their homes.”Footnote 25

Can we draw any conclusions from comparison of trajectories of Republican versus Democratic attention to immigration issues in the 2000s? The trends we have documented indicate that, especially from around 2000 to 2002, immigration issues became increasingly salient for both state and national parties on both sides. Boosts in attention were largely synchronous. Nevertheless, of special interest as we move forward, state-level GOP platforms increased their focus on immigration especially sharply, coming to outpace their national-level counterparts in levels of attention to this issue. Increases in attention occurred in, but were not isolated to, the southwest border states and traditional immigrant portal states—many other states exhibited increased attention as well.

Intriguing as our findings about attention trajectories may be, tracking word percentages alone can take us only so far. We turn next to the substance and valence of platform provisions. What substantive agendas were party leaders and associated activists proclaiming as they said more about immigration issues?

3.3 Changing—and Diverging—Party Positions

As both parties, and especially Republicans, paid much more attention to immigration in the 2000s, the content of Democratic versus GOP stances moved in sharply opposite directions. Using our measures of policy content, we demonstrate that Democratic platforms increasingly adopted inclusionary themes, while their Republican counterparts increasingly made restrictionist references. Specifically, Figure 2 presents trends from state- and national-level platforms in Democratic and Republican uptake, respectively, of inclusionary and restrictionist themes. This figure tells the big-picture story about recent party polarization around immigration, especially as overall levels of attention to immigration rose in state and national platforms from 2000 to 2017.

Figure 2. Inclusionary Democratic and restrictionist Republican references to immigration within state and national platforms, 1980–2017.

Notes: Both paired and unpaired platforms are included. Platforms released in odd years are assigned to the previous even year. Negative values indicate the number of references to restrictionism in Republican platforms and positive values indicate the number of references to inclusion in Democratic platforms. Line charts track the mean number of references in Republican and Democratic state platforms to restrictionism and inclusion respectively. Ribbons indicate values within one standard deviation of this across-state mean and are truncated to have a minimum value of 0, reflecting the support of the plotted index. Clustered bar plots indicate the number of references to restrictionism and inclusion in Republican and Democratic national platforms.

Prior to explicating this story, it is worth commenting on why Figure 2 displays only the dominant valence of each party’s platform provisions. In our full data analysis, we coded for both restrictionist and inclusionary provisions in all platforms. We did this so as not to miss important crosscutting tendencies—and in particular to evaluate claims from some observers that Democrats have maintained restrictionist stances. Appendix C lays out our findings about restrictionist provisions in Democratic platforms and inclusionary stances in Republican platforms. We find that such provisions are not very numerous compared to dominant Republican restrictionist and Democratic inclusionary stances. Democrats do, on balance, offer relatively more restrictionist provisions than Republicans offer inclusionary ones, but the Democratic restrictionist proposals are mostly general calls for heightened border enforcements, always juxtaposed to other proposals for improved treatment of new arrivals. Overall, as Appendix C makes clear, including opposite valence counts would not substantially modify the dominant valence trends tracked in Figure 2. For simplicity, therefore, we keep the focus in this section on diverging trends in GOP restrictionism versus Democratic Party embrace of inclusionary measures.

Returning to Figure 2, we turn first to examining trends in state platforms’ adoption of inclusionary and restrictionist themes, as well as to the question of whether patterns of adoption were consistent across states. Tracing party averages for each year, we see that substantive partisan divides grew after 2000 as Republicans embraced restriction and Democrats emphasized inclusion. Democratic state platforms on average moved gradually toward inclusionary tenets from 2002, but Republican state platforms veritably leapt upward to proclaim more restrictionist measures—going from 0.5 platform provisions on average in 2000 to 3.1 on average by 2008. We can conclude, in short, that during the early 2000s, much of the initial party polarization on immigration stances was driven by proliferation of restrictionist positions in Republican state platforms.

As the average number of restrictionist and inclusionary references grew in state Democratic and Republican platforms, so did the size of each party’s standard deviations. Larger standard deviations suggest that later in our period, there was more variability between states in Republican parties’ adoption of restrictionist stances and Democratic parties’ adoption of inclusionary positions. This increased variability stemmed from the wider range of positions taken by state parties. While some state parties’ platform sections on immigration ballooned with detailed inclusionary or restrictionist references to all seven of the policy areas we track, others continued to make brief and vague references to immigration.

Yet others took a middle ground, making a number of inclusionary or restrictionist references in line with their party’s average. These buckets do not neatly map on to states’ statuses as border or immigrant portal states. For example, the Republican Party of Arizona’s 2010 platform—the most recently available platform from this state party in our data set—makes only two restrictionist references to immigration. By contrast, in 2010, the Republican Parties of Iowa and Minnesota, states far from the southern border, made restrictionist references to six and seven areas of immigration policy, respectively. In sum, movements toward restrictionism and inclusion within state Republican and Democratic party platforms did not proceed uniformly. However, moves toward party averages and even more extreme stances were widespread—and occurred not only within but also beyond border and other immigrant portal states.

Turning to national party platforms, Figure 2 indicates that, as in their state-level counterparts, polarization played out as the two parties paid more attention to immigration issues. Restrictionism steadily grew in Republican national platforms from mentions of two policy areas in 2000 to six in 2012 (before receding in the 2016 platform as such, when proudly restrictionist GOP nominee Donald Trump grabbed the party megaphone). On the other side of the aisle, the Democratic national platform in 2000 was still giving some attention to the 1996 enactments, making four inclusionary references to immigration. Such references then declined to two for the 2004 and 2008 Democratic national platforms, before moving sharply up to new high points in 2012 and 2016 presidential years. Taking into account the Trump effects on GOP positions in 2016, we can safely say that the two major U.S. parties were, by then, at peak national attention and very sharply polarized on immigration. What is more, even though our coding of national platforms stops in 2016, there is no reason to believe that immigration polarization has thereafter attenuated in any way.

3.4 A Closer Look at GOP State and National Shifts

Just as we learned that Democratic and Republican national and state platforms increased their attention to immigration issues roughly in tandem, so, too, have we just seen that immigration stances polarized between inclusionary Democrats and restrictionist Republicans in broadly parallel directions and tempos at the national and state levels. This finding of considerable national-state synchronization contrasts with Eric Schickler’s finding that national-level realignments around civil rights were preceded by a decades-long process of state-level realignment.Footnote 26 It also contrasts with recent findings by Gerald Gamm and coauthors that national party movements on abortion and LGBTQ issues were preceded by state-level shifts.Footnote 27 For immigration, we find not only that increased party attention and party divergences unfolded more recently than earlier rounds of attention to and polarization about racial civil rights and family and gender regulations; we also find that national and state parties have moved more quickly and in tandem.

However, within the overall 2000s picture of rapid and simultaneous increases and shifts in immigration planks in national and state party platforms, there are indications early-moving states introduced new themes that later diffused across many states and gained ground in national party platforms. We have looked especially closely at the GOP side, where turnarounds on immigration from business-friendly moderation to embraces of tough restrictionist measures have been particularly evident. States do seem to have spearheaded this turnaround. Figure 1 indicated that in the early 2000s, attention to immigration issues surged in GOP state platforms ahead of national platforms; Figure 2 shows an especially steep average state-level GOP trajectory toward more restrictionist state-level platform provisions from 2002 through 2010.

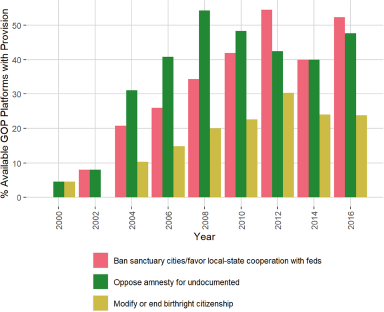

State-level GOP movements come into even sharper view when we probe particular kinds of very restrictionist planks. As displayed in Figure 3, we looked closely at the trajectories of three especially hard-line restrictionist planks: those opposing sanctuary cities for immigrants and calling on local and states authorities to help with federal enforcement actions; those opposing amnesty or a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants; and those questioning whether the U.S. Constitution’s birthright citizenship provision should be changed or reinterpreted to deny automatic citizenship to infants born to undocumented parents. For such measures, particularly opposition to birthright citizenship, GOP states were in the vanguard.

Figure 3. References to strong restrictionist provisions in state Republican platforms, 1980–2017.

Note: Both paired and unpaired Republican state-level platforms are included. Platforms released in odd years are assigned to the previous even year. For full descriptions of how we determine restrictionist stances on state and local authority, undocumented immigrants, and undocumented children, refer to Table 1.

The topic of state and local cooperation with federal law enforcement first arose in Oregon and South Carolina GOP platforms in 2002, slightly ahead of national platform mentions in 2004. The gaps were more substantial for the other two policy issues. In national GOP platforms, anti-amnesty planks appeared from 2004 on. But national adoptions began well after anti-amnesty planks first appeared—as blips—in the 1980 California platform and the 1984 Texas platform. When we turn to provisions against birthright citizenship, state priority is even more clear-cut, because the percentage of GOP state platforms including anti-birthright citizenship provisions rose from 5 percent in 2000 to 25 to 30 percent between 2010 and 2017, while national GOP platforms remained silent. Across our entire period, in fact, the only mention of birthright citizenship in a national GOP platform happened in 1996, when the party’s presidential nominee, Bob Dole, allowed a vague criticism as a gesture to nativist nomination contender Pat Buchanan.

In short, even in a nationalized political era where immigration shifts in agenda-declaring platforms have happened fast and in mostly parallel ways between parties and between national and state levels,Footnote 28 state parties can push forward new issue positions from below. Indeed, many Republican state parties appear to have done exactly that on the highly contentious matter of questioning birthright citizenship. Overall, our data suggest that restrictionist platform planks especially hostile to undocumented migrants have been encouraged by extra-party and/or subnational dynamics in the GOP orbit. Figuring out what those forces might be and how they have played out to help account for the trends we have documented over many years is the next frontier in understanding U.S. party polarization about immigration.

4. Potential Drivers of Party Shifts

In this article necessarily devoted to laying out basic trends, we cannot establish precise causes for recent increases in party attention and sharp party polarization about immigration—especially the GOP’s rapid and strong turn toward immigration restriction. What we can do, in this second major part, is explore which sorts of factors are likely or unlikely to have been major propellants of party shifts and divergences in this core area of societal regulation.

For starters, we can rule out some widely presumed but overly simple causal stories grounded in demography or public opinion. To be sure, rising concern about immigration by both parties followed the surges of newcomers arriving in the United States or at its borders after 1965, but net immigration steadied or reversed by 2008, while both party attention and polarized position taking have continued apace. Nor are overall public opinion shifts obvious drivers of party changes. As Republican and Democratic elites and activists have increasingly clashed over immigration in the 2000s, Americans in general tell survey researchers that they are more, not less, open to welcoming more newcomers or least leaving admissions at steady levels. To be sure, a growing embrace of inclusionary policies has occurred mostly among self-identified liberals and Democrats—on that side of the partisan spectrum, voters’ views have, if anything, moved toward inclusion even faster than official party agendas.Footnote 29 However, Republicans overall have remained consistently moderately supportive of immigration. As much of their party has moved to the hard right, GOP-identified voters in the aggregate have not done the same. But the overall GOP picture masks sharp internal divides, because self-identified “very conservative” Republicans and those calling themselves Tea Party supporters or Donald Trump enthusiasts have become more wary of or hostile to immigrant arrivals, especially undocumented immigrants.Footnote 30 Intense minority demands, well organized and consistently pressed on elected politicians, matter much more in this case than generalized public opinion.

Beyond demographics and overall public opinion, two sets of specifically political factors may help account for our platform trends. At the level of legislators and organized interest groups, shifts in the ranks of highly resourced core players in party orbits plausibly encouraged polarizing party immigration shifts—and repeatedly gridlocked congressional battles over grand immigration compromises may also have encouraged polarization. Looking even more broadly to include popular forces, the early 2000s saw the eruption of nationwide social movements taking opposite sides on immigration, including the immigrant rights protests of 2006, and Tea Party protests and grassroots organizing from 2009 into the 2010s. Although some view the Tea Party as primarily about government spending, previous research has found that grassroots Tea Partiers were worried about and strongly opposed to immigration and extensions of rights to newcomers.Footnote 31 In a short period, pro-immigrant protesters and conservatives, eventually including Tea Partiers, put diametrically opposite pressures on the two major parties.

In a preliminary way, we can say more about why both the elite-level and social movement factors we have just pinpointed deserve much closer attention, because they correspond to the trajectories of party change and polarization we have previously outlined.

4.1 Reorganized Insiders and Failed Congressional Compromises

Much recent work on U.S. political parties is inspired by the “UCLA school” conceptualization of parties as changing orbits of organized “policy-demanding” groups.Footnote 32 Work from this perspective urges us to see party leaders as devoted to managing and melding the sometimes crosscutting policy preferences of changing fields of organized party constituencies. Policy battles in Congress are often analyzed in these terms, as indicators of shifting party coalitions and their implications for legislative compromise or deadlock. For immigration, the most relevant scholarship in this vein focuses our attention, fruitfully, on repeated efforts to enact “comprehensive” bipartisan immigration reforms.Footnote 33 Not just the congressional processes and outcomes each time, but the aftermath of successful and failed high-profile legislative battles in 1996, 2004–07, and 2013–14 almost certainly help us understand the national-level forces that have propelled party polarization on immigration issues.

First, we can quickly note that both parties have experienced shifts in the ranks or preferences of “policy-demanding” inside players. Beginning in the 1980s, as many analysts have shown, the Republican Party turned for votes and grassroots organizational heft toward social conservatives, most strongly clustered in the South and Midwest.Footnote 34 As this happened, the one-time party of Abraham Lincoln to Dwight D. Eisenhower sought to meld its business allies’ opposition to taxes and market regulations with southern white opposition to federal civil rights enforcement and Christian right calls to restrict abortion and enforce traditional gender, sexuality, and family norms. In the early phases of Republican efforts to forge this uneasy marriage of economic and social conservatism, immigration issues were not salient and may well have been deliberately downplayed by most GOP leaders. Nor were Democrats pushing in consistent directions on immigration policy during the 1980s and 1990s, because the national party and many state parties had to deal with crosscutting pressures from, on the one hand, immigrant advocates pushing for inclusive measures and, on the other, dwindling but still politically potent industrial unions worried about newcomers undercutting wages for blue-collar union members. Arguably, the sets of “policy demander” organized groups within GOP and Democratic orbits helps to explain why, even as the major parties polarized on civil rights and abortion/family issues, both Republicans and Democrats had reasons to soft-pedal immigration stances. This accords with our platform data showing that platform proclamations about immigration matters remained both sparse and only moderately polarized from 1980 until the mid-1990s.

But then things abruptly changed. As Figure 2 dramatizes, national Democratic and Republican platforms articulated sharply polarized immigration positions in 1996, and from 2000/2002 on, both state- and national-level party platforms splayed sharply apart, with Democrats moving toward inclusionary positions on immigration and Republicans galloping toward tough restrictionist stands. Worth more investigation is whether grassroots Christian conservatives on the GOP side were becoming more concerned about the cultural reverberations of immigrant migrations by the mid-1990s.

However, relevant reworkings of constituency pressures may at first have been more telling on the Democratic side, because industrial unions had declined markedly by the late 1990s and service worker unions with many immigrant members became more important blue-collar allies of the Democratic Party.Footnote 35 Unions with many Hispanic workers supported party moves toward more inclusionary approaches to immigration, and many members of still-potent unions of teachers and public-sector employees did not feel as threatened by immigrant competitors as members of beleaguered industrial unions. As organized groups in the Democratic Party orbit—including immigrant rights advocacy organizations and immigrant-friendly unions—became more unified around welcoming and inclusive stances, national Democratic platforms added more inclusionary planks on immigration. At the same time, congressional Democrats converged on inclusionary stances and made recurrent attempts to team up with pro-business Republicans to advance compromise immigration reforms combining enhanced border enforcement with pro-business provisions and expansions of immigrant rights and possible paths to citizenship. Such efforts at balanced bipartisan compromise worked for a while, especially in the Senate, which advanced compromise packages in 1996, 2006, and 2013; however, the Senate bills tended to stall or get reworked toward tougher restrictions in the House of Representatives as business-oriented immigration moderates lost ground in the GOP to ever harder-line conservatives.

The dynamics of these recurrent high-profile DC legislative battles have been dissected by UCLA School analysts.Footnote 36 Their work highlights national immigration policy battles that certainly helped focus nationwide attention again and again on this area, and it shows that, over time, restriction-minded GOP senators gained ground even as congressional Democrats became more consistently inclusionary in their legislative preferences. Broader commentaries on legislative reform attempts also indicate that Republicans in the House of Representatives moved steadily to the hard-restrictionist right, enough to make it impossible to get House majorities for Senate-passed immigration reform compromises in either 2007 or 2014. One way to sum up this line of analysis is to hypothesize that, by the 2000s, repeated failures of efforts by party-insiders and congressional leaders to arrive at bipartisan compromises served to both raise the nationwide profile of this issue area within and between the parties, and at the same time show that America’s top officeholders and their organized allies could not reach workable solutions. At the very least, visible GOP and Democratic elite failures to handle what they called pressing immigration problems surely helped to spur growing and spreading partisan polarization.

Another possible effect of high-profile congressional battles is also worth mentioning, because even the final 1996 instance of an apparently “successful” congressional compromise legislation may actually have done as much as subsequent failed congressional efforts to politicize this arena. A careful analysis of the 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act probes voting patterns in the Senate to show that remaining business-oriented Republicans teamed up with increasingly like-minded Democrats to push the Senate version through.Footnote 37 But that was, of course, not the end of the story, because by the time reworked legislation got through the House of Representatives and onto President Bill Clinton’s desk for signature, the surviving, not especially bipartisan core of the bill featured unprecedently tough measures to suddenly deport, without recourse, undocumented immigrants living anywhere in the country who had ever committed any of a wide variety of crimes. The intended and unintended aftereffects of this law became evident on the ground by the early 2000s, and spurred further sharp partisan polarization while drawing localities and states increasingly into controversies over the role of their law enforcement in detaining local people for sudden deportation.Footnote 38 Our party platform trends show that attention and polarization in state party platforms grew from 2002 on, just as the 1996-mandated local enforcement provisions started to be widely implemented and controversies about them erupted across many states.

Congressional efforts sputtered and died in 2006–07 and again in 2013–14, which was the last time a grand compromise bargain was even attempted. As these highly visible national failures to reform federal immigration policies happened, GOP-led states, in particular, moved toward strong actions of their own, such as advancing “show-me-your-papers” style legislation that criminalized the presence of undocumented immigrants and required law enforcement personnel to ask for proof of immigration status. In Arizona, such legislation passed in April 2010 under new Republican governor Jan Brewer; at the time, it was the most wide-reaching measure to penalize undocumented immigration seen in the United States.Footnote 39 Other states were quick to mimic the Arizona bill. Within a year, thirty-one states had introduced similar bills, and Utah, Georgia, Indiana, Alabama, and South Carolina had passed copycat versions.Footnote 40 Although severe measures were challenged in the courts and some were eventually rolled back, the proliferation of state laws targeting undocumented immigrants highlights the fact that the Republican abandonment of moderate stances and compromise legislation occurred during the same few years at both the state and national levels.Footnote 41

4.2 Immigrant Rights Protests and the Tea Party

A full analysis of the roots of immigration polarization and GOP restrictionism must plausibly look beyond inside players and congressional politics to broad social movements and pressures on subnational as well as national politicians. Tellingly, the sharpest upward turn in average numbers of state-level GOP immigration restriction planks occurred between 2002 and 2006; the average of Democratic state-level inclusionary planks also turned upward then, suggesting a marked overall increase in party polarization. It is probably not coincidental that the span of time from 2002 into the mid-2010s saw not only the ultimate collapse of congressional immigration compromises along with the upticks in subnational enforcement steps and controversies mentioned earlier, but also nationwide protests about attempted national crackdowns on undocumented immigrants and residents.

An early flashpoint was the Border Protection, Anti-terrorism and Illegal Immigration Control Act, which passed in the Republican-controlled House of Representatives in December 2005.Footnote 42 This act marked a House GOP immigration initiative focused not on compromise but almost entirely on excluding and expelling undocumented immigrants. Remarkably, it also aimed to punish people who helped undocumented residents living and working in the country. House advancement of this legislation aroused intense pushback to forestall Senate passage from immigration rights advocates and other institutionally powerful opponents. Even more dramatically, it sparked “massive” and widespread protests between February and May 2006 involving up to five million people involved in 350 demonstrations across more than 140 cities in thirty-nine states—culminating in synchronized May 1, 2006, “Day without Immigrants” protests meant to dramatize what would happen to America’s economy without the work and consumer buying power of immigrants.Footnote 43 In the end, the Republican-controlled Senate did not pass any version of the House’s 2005 draconian legislation; instead, both President George W. Bush and key senators made a further push for the compromise immigration bargain that failed in 2006–07.

Nevertheless, we can safely assume that this entire episode, from the polarized House proceedings through advocacy pushback and mass protests, must have spurred further divides within as well as beyond Congress. One the one hand, immigrant rights advocates mobilized to press Congress and Democrats for a path to citizenship for the undocumented and less draconian enforcement measures. On the other hand, news accounts in 2006 pointed to right-wing backlashes against liberal amnesty proposals and newly aroused conservative worries about public assertiveness by immigrants and their allies. Get-tough-on-immigrants politicians certainly decried the protests, noting, in the words of Colorado congressman Tom Tancredo, that “all these folks who are here illegally know they can protest brazenly.”Footnote 44

Scholars who have studied the impact of these protests argue that they aroused a new sense of collective Hispanic political awareness and efficacy.Footnote 45 Conclusions about general public opinion shifts are more ambiguous; some accounts suggest that protests moved public sympathies in the direction of support for amnesty and a path to citizenship for undocumented residents, at least among people who lived near the largest demonstrations that mostly happened in immigrant portals like California and New York.Footnote 46 Other analysts point to growing public sympathy for tough border enforcement, with one GOP pollster telling Time magazine that the “views of most of the people marching in the streets of L.A. and other cities … bear little or no resemblance to the majority of public opinion in this country when it comes to illegal immigration.”Footnote 47 Additional kinds of data—such as our platform trends and later Tea Party evidence that we will mention—certainly suggest that conservatives and Republican-connected active citizens perceived the 2006 mobilizations as threatening. One sociologist who was doing research in South Carolina at the time suggested one possible mechanism when she noted that native whites who had previously seen their immigrant neighbors as hardworking family people suddenly realized that they could be a new, worrisome political force, too, at the ballot box, in strikes, or through mobilized protest.Footnote 48

Between 2006 and 2008, many analysts thought that the immigration polarization that kicked into high gear from 2002 through 2006 would turn the 2008 presidential election into an immigration policy battle royale, especially over the treatment of the 10 to 11 million undocumented immigrants residing in the United States. That ended up not happening, after the GOP nominated John McCain—who was no longer pushing moderate immigration reforms but was not a firebrand restrictionist either—and the world plunged toward a massive economic depression that took political center stage.Footnote 49 But glaring partisan divides on immigration did not go away, and they next flared up in 2009 and 2010 as a central part of the right-wing Tea Party rebellions against newly installed Barack Obama and the fully Democratically controlled Congress that took office with him after the 2008 elections.

The “Tea Party” as a whole was a concatenation of national-level far-right advocacy primarily aimed at stopping new redistributive forms of federal taxing and spending with nationally coordinated, geographically widespread protest demonstrations (especially in April, July, and September 2009) that happened alongside the spread of one to two thousand locally organized, popularly run Tea Party groups devoted to ongoing agitation against Barack Obama and his fellow liberals.Footnote 50 Much media coverage at the time never got beyond elite advocacy claims that the “Tea Party” was about cutting federal spending and reducing deficits. But interviews and ethnographic engagements with actual popular Tea Party groups revealed that Christian right and ethnonationalist priorities were much more passionately relevant at the rank-and-file Tea Party level.Footnote 51 And quality surveys showed by 2010 that Tea Party–supporting conservatives and Republicans wanted especially tough immigration restrictions and were much more concerned about perceived immigration threats, compared not only to Democrats and independents but also to other Republicans not affiliated with the Tea Party.Footnote 52 Furthermore, Tea Partiers were angry at “establishment” Republican officeholders and candidates who they believed had not done much, if anything, to reverse perceived immigrant threats—and they certainly did not want Republicans to consider compromises with President Obama and congressional Democrats.Footnote 53

On the face of it, a credible hypothesis might be that locally organized Tea Parties from 2009 pushed GOP officeholders and candidates to refuse immigration compromises and advocate ever-tougher restrictions—and there is certainly reason to believe this happened. Once in place by 2010 and 2011, between 2,000 and 3,000 local Tea Party groups and associated activists were especially geographically concentrated in very safe GOP areas.Footnote 54 Their concentration tended to pull many GOP primary contests and legislative stances toward tough, anti-compromise stands. However, our finding that upticks in GOP state platforms’ restrictionist provisions began as early as 2002 suggests that many such hard-line expressions emerged well before the Tea Party eruptions and ongoing local Tea Party organizing—even if Tea Party protests and organizing in turn spurred further Republican Party movement to the hard right on immigration and other issues. Subnational nativism in many states may, in short, have helped propel both new provisions in GOP platforms and, once Barack Obama and Democrats took over in Washington DC, widespread eruptions in Tea Party protests and organizing.

In this chronological picture, the Tea Party movement hardly loses relevance, but it becomes an important intervening factor rather than the first mover in the immigration polarization story. Grassroots anger about immigration among the most far-right voters and groups in the GOP orbit may have helped lay the basis for the original 2009 Tea Party eruptions against Obama and the Democrats—and, thereafter, also contributed more anger and organized clout to further GOP nativism. The Tea Party was not a short-term flash in the pan, because volunteers across the country organized local Tea Party groups. Along with individual activists who signed up on the email and social media list of national Tea Party labeled organizations, persistent local Tea Parties boosted the clout of social conservatives within the GOP, giving them a capacity to press demands and influence elections that went far beyond their numerical minority numbers. They did just that from 2010 onward, and one of the most popular concerns raised by the Tea Party was a long-simmering desire for Republicans in office, running for office, and running party organizations (including those writing platforms) to place much more emphasis on tough immigration restrictions.

After Republicans made big gains in the 2010 midterm elections, their net gain of sixty-three House seats allowed them to take control of the chamber for the remainder of Barack Obama’s two-term presidency. From that point, researchers tried to discern whether “Tea Party Republicans” voted differently than other GOP representatives. However, such exercises usually found no statistically significant relationships.Footnote 55 This has been the case in part because there was no straightforward way to measure “Tea Party” alignments in Congress, but more fundamentally because in recent years most Republicans—not only those aligned with the Tea Party—have moved together toward hard-right fiscal and cultural positions.

During the same years in the 2010s that our data show proliferating state-level and national GOP platform endorsements of immigration restrictions, Tea Party influences grew in Congress and persisted even after general public approval of the movement declined from 2011.Footnote 56 Republicans in Congress who were most interested in proclaiming Tea Party ties became prolific issuers of bombastic hyperpartisan tweets, starting down a polarizing communication path that Donald Trump would later turn into an expressway. Many analysts suggest that both elite and grassroots Tea Party forces ended up pushing elected Republicans not just toward far-right policy positions but also toward uncompromising styles of governance—including on any possible immigration compromises within the GOP or between Republicans and Democrats.Footnote 57

Once Republicans made further congressional and state gains in 2014, restrictionist ideas about immigration and support for tough measures against migrants living in the country took over the overall Republican agenda through the 2015–16 ascendance of Donald Trump. Both Trump’s ascendance in the GOP and his solidification of a devoted new core GOP base, were in turn grounded in the views and grassroots organization of nativist-minded popular supporters. Survey-based studies tell us that the subset of GOP base voters who supported both the Tea Party and Trump have been markedly more anxious about immigrants and more supportive of hard-line restrictions.Footnote 58

Such evidence strongly suggests that continuing rightward GOP moves on immigration matters in recent years have been furthered not by changes in U.S. public opinion in general, or even by overall shifts in Republican voter sentiment, but much more specifically by the best organized and most active grassroots conservatives. Americans in general, including many middle-of-the-road Republicans, have remained supportive of immigration.Footnote 59 Within the Republican orbit, however, highly mobilized and well-networked grassroots right-wingers have a nationwide presence; they favor tough immigration restrictions, and they are especially strong, vocal, and active in primary as well as general elections in the most conservative GOP-dominated House districts and in Senate states with larger nonmetropolitan populations. Quite likely, these grassroots conservatives agitated by immigration and undocumented immigrants have been a force to be reckoned with by state-level Republican platform writers as well.

5. Conclusion

This study contributes to a growing literature on the tempo, substance, and possible causes of U.S. party polarization in late twentieth and early twenty-first century at both the state and national levels. In conclusion, we suggest how the latest unfolding immigration clashes may be supercharging U.S. partisan divides and fueling Republican Party radicalization. The big picture comes into focus when we combine our platform-based findings on immigration polarization with findings by previous scholars who have also analyzed platforms to track party shifts and polarization.

In their pathbreaking work tracing partisan realignments around racial equity issues using state and national platforms, Brian Feinstein and Eric Schickler showed that divergences began in the 1930s and 1940s, when northern Democratic states took pro–civil rights stands that paved the way for eventual adoption of divergent national party positions in the mid- to late 1960s.Footnote 60 Next, as Gerald Gamm, Justin Phillips, Matthew Carr, and Michael Auslen demonstrated, some Democratic and Republican state platforms started to diverge on LGBTQ rights and abortion issues starting in the early 1970s, and state- as well as national-level party platform divergences proceeded steadily thereafter.Footnote 61 Crucially, once these polarizations on social-regulatory issues became pronounced within national and many state party platforms, they have not subsequently reversed. Democrats and Republicans continue to take sharply divergent positions on how to redress racial inequalities and guarantee minority rights, and they disagree equally if not more sharply on abortion and LGBTQ rights.

Layering onto these previous transformations, as our research shows, Democratic versus Republican divergences in yet another major social-regulatory realm—on immigration policy and the treatment of migrants—unfolded suddenly and sharply in the first two decades of the twenty-first century. This latest polarization occurred relatively synchronously in national and state party platforms, although many GOP state platforms moved first in the early 2000s to reorient the GOP toward severe restrictionist stances that amount to almost a 180-degree turn from where Republicans stood on immigration policy around 1980.

Figure 4 summarizes these successive layers of Democratic versus Republican party polarization on major realms of social-regulatory policy, divergences that have piled one on top of one another from the 1930s through the 2010s. Why do the temporalities and layers portrayed in this figure matter? One possibility is that the unfolding party repositioning and divergence in each successive issue area reinforces long-standing party fault lines, adding social-regulatory divergences between the parties on top of already long-standing differences between Democrats and Republicans about government’s role in the economy.Footnote 62 Conflicts between parties might intensify as a result, but actors within party networks may continue to focus on particular issue areas instead of drawing broader linkages across issues. In this case, the legislators, advocacy groups, and mobilized constituencies that care most intensely about an issue area would continue to dominate decision-making in that realm, without much spillover to position taking on other issues.

Figure 4. Layering of state and national U.S. party polarizations on social-regulatory issues.

Note: In every area, clusters of Democratic states moved left first; then the GOP moved further right.

Another possible dynamic is that decades-long, successive processes of party divergence on social-regulatory as well as economic issues have by now done more than just reinforce and add to older divisions. The layering of social-regulatory conflicts on top of economic disagreements, and especially the superimposition of new societal disputes on top of one another, may bring multiplicative, not just additive effects. Such explosive combinations may happen when many kinds of partisans—ranging from legislators to activists to voters—draw connections across previously discrete issue areas and forge multiply reinforced alliances justified by broad, morally charged, and uncompromising worldviews.

We consider the multiplicative layering possibilities well worth careful further investigation—in studies of interest groups, party dynamics, and social movements as well as in ongoing research about mass attitudes. Arguably, each successive social-regulatory polarization in the United States since the mid-twentieth century has interacted with the earlier divergences. For example, party disputes from the 1970s to 1990s about government policies toward mother-led families were infused with earlier racially charged arguments about “welfare” programs. And recent party divergences about which kinds of immigrants to welcome and how to treat new arrivals are unfolding against the backdrop of previous social-regulatory polarizations about race, voting rights, and social supports for families. Survey-based research by scholars including Christopher Parker, Matt Barreto, Marisa Abrajano, and Zoltan Hajnal has already demonstrated that racial equity issues are very much in play in immigration disputes, because new arrivals to the United States since 1965 have included higher shares of migrants from Central and Latin American, Asian, and Africa than pre-1965 waves of white, mostly European immigration.Footnote 63

Interactions among the temporally successive social-regulatory polarizations portrayed in Figure 4 may be especially important for understanding current Republican Party radicalization—including the willingness of some in and around that party to fight partisan battles outside normal institutional rules of liberal-democratic politics, even to the point of threatening or condoning political violence. Fights over racial equity, sexuality and gender, and the rules for admitting immigrants all get to the core of U.S. national identity, and they are central to debates over the collective characteristics that define American culture and nationhood in a shifting demographic and political landscape. The GOP’s overall embrace of social conservatism has been underway since the 1960s and 1970s, but it is now proceeding in a society recently transformed by new waves of non-European immigrants and the advent of younger generations of current and potential voters with increasingly varied ethnoracial backgrounds, sexual orientations, and gender identities. As these changes have been politicized, some segments of the GOP have come to see the political stakes as existential—about America’s very identity and threatening enough to justify authoritarian, anti-democratic responses.

Much more research will be needed to pin down exactly how, when, and why partisan polarizations have unfolded in successive issue areas and across various arenas of political conflict within and around the Democratic and Republican Parties. Further research can build on literatures already probing attitudes in the mass electorate, congressional voting patterns, and changing state and national party platforms, and supplement these established lines of work with analyses of organized advocacy groups, shifting interest coalitions, and social movements such as the Tea Party and the immigrant rights movement. Our contribution here has been to outline and give empirical heft to a modest but critical part of the overall story, and we look forward to doing more research on these issues. Along with many others, we aim not only to understand how conflicts over immigration have supercharged party polarization in recent years, but also how they have helped fuel the radicalization of today’s Republican Party and the increasingly worrisome embrace of authoritarian measures and threats of violence by some in its orbit.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0898588X23000056.