Helen Bledsoe: Das atmende klarsein – an act of translation

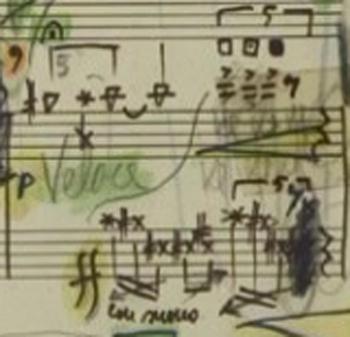

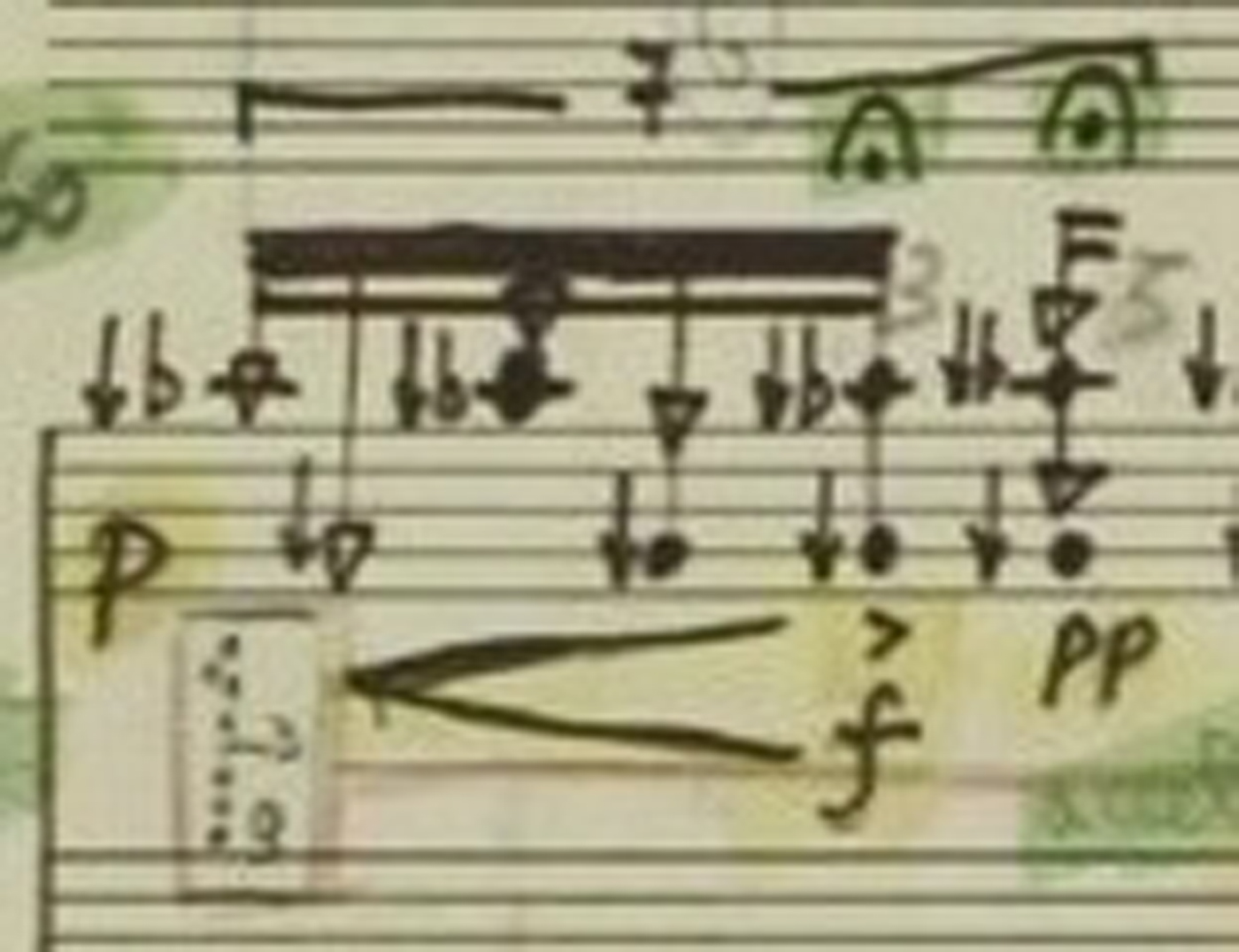

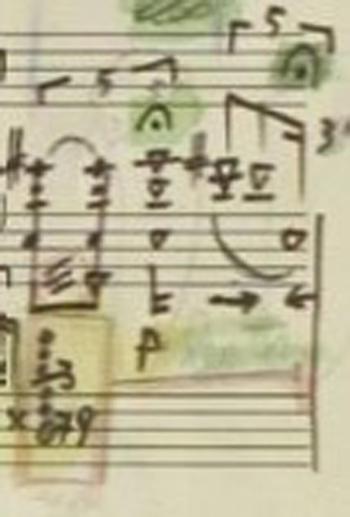

The notation of Luigi Nono's late works raises many questions for its performers. His music is not complex in the traditional sense of instrumental virtuosity; its complexity arises not from a high density of rhythmic and dynamic material, but from an attempt to depict unconventional sounds and loosen the constraints of time in order for these sounds to live. Some examples include multiple staves for single voices, various note head shapes, and detailed graphic indications (see Example 1).

Example 1: Luigi Nono, Das atmende Klarsein.

One could be fooled into thinking that such detailed notation should demand detailed reproduction. Yet according to Nono's own testimony, his scores provide a point of departure for the performer. In an excellent article by Laura Zattra, Ian Burleigh and Friedemann Sallis,Footnote 1 the authors explore this testimony within a historical perspective. According to the authors, A Pierre could be viewed as a late twentieth century version of tablature notation in that it does not provide an adequately detailed visual representation of the aural results. (See the second half of this article for more on the sonic world of A Pierre.) Tablature notation will give instructions on how to perform a work, but will not represent its sonic outcome: it is therefore prescriptive. Modern musical notation, ideally, provides a visual representation of what one hears and is thus descriptive. It is interesting to contemplate which aspects of the flute part of Das atmende Klarsein can be considered prescriptive or descriptive.

The flute parts of Nono's late works, including, among others, Das atmende Klarsein and A Pierre, were developed in close collaboration with flutist Roberto Fabbriciani. It was an enviable working relationship: Nono and Fabbriciani spent hours together, experimenting, recording and analysing sounds. Fabbriciani, like Nono's other instrumental collaborators,Footnote 2 ended up establishing his own performance tradition in relation to Nono's music. The question naturally arises: how are other players to approach this work? In an interview with Philippe Albèra in 1987 Nono said of his legacy:

Other musicians will make other music! One still tries to fix things graphically, but as I have said several times, I do not adhere to a concept of notation! It's like Gabrieli's music: he writes ‘sonar and cantar’. The dynamics, the tempo, the distribution between voices and instruments are not fixed. The practice which made the realization has disappeared.Footnote 3

Nono then goes on to insist that to make, to communicate, to live the experience of creation, is more important than to reach a fixed form. Reading this puzzles me, and leads me to wonder whether Nono is referring to his instrumental writing or to the unpredictable processing effects and spacial characteristics of live electronics, which are impossible to capture in conventional notation. I find few obvious points that invite departure in the bass flute part of Das atmende Klarsein, apart from aspects of timing and the inherent instability and variability of unconventional sounds (such as multiphonics and aeolian sounds produced by inhaling and exhaling). This is, I believe, a natural outcome of close collaboration. Barring free improvisation (which Nono does include in the final movement of Das atmende Klarsein), a performer wants to have, if not a fixed form, then at least a fixed path that describes the actions to be carried out. Although the resulting sounds will vary according to player and type of instrument, instrumental sounds are, generally speaking, not as capricious or subject to variation as electronic sounds.

Nono strove to find instrumental sounds which were un-academic and un-clichéd, but he also realised that his music would have an afterlife. Language and musical notation are subject to change, and what now sounds fresh and new will be differently perceived by future generations. Since the publication of numerous modern instrumental guides,Footnote 4 composers have embraced extended techniques almost to the point of overkill. Their use can sound clichéd to the twenty-first-century listener.

Two over-arching questions present themselves at this stage for the players of Nono's late works: How shall I realise this work today in keeping with Nono's unconventional spirit without re-creating a 1980s museum piece? and, In realising Nono's intentions, as represented by the performance tradition of another player, is my role that of a translator as well as an interpreter? In addressing the first question I study the score to discern passages which could be construed as notational elaborations, or as artefacts of transcription, or as mere misinterpretations of the manuscript. Then I decide which of these might be utilised to broaden the sound palette, depart from the score, or which are better ignored. This is particularly relevant for part 2 (the first part for flute) of Das atmende Klarsein, from which I will draw the following examples.

Bar 7 (see Example 2) shows a passage with variegated percussive noises, and expresses what I see as a notational elaboration of a relatively simple gesture of Fabbriciani's. In the manuscript shown in the DVD that accompanies the score of Das atmende Klarsein, the gesture is written on a single staff (see Example 3). This clarifies the original intention of timing. The articulation indications of the last three notes, not the notes themselves, were added above the upper staff.

Example 2: Luigi Nono, Das atmende Klarsein, bar 7.

Example 3: Luigi Nono, Das atmende Klarsein, manuscript, bar 7.

One could elaborate further by adding lip pizzicati to the key clicks using various consonants: t, k or p. The black square over the final note indicates that the embouchure hole should be covered. One could embellish the final C# covered key click with a climactic tongue ram. Either way, since the pitch changes with the closing of the embouchure hole, is C# the resulting sound (as a purely descriptive score would assume) or an indication of the fingering, producing a different result (as a prescriptive, or tablature notation would assume)?Footnote 5

Another potential point of departure is the use of multiphonics in this movement. Fabbriciani's fingerings are provided in the manuscript, although one is of course free to find alternatives, as multiphonics will vary depending on the player and type of flute. Since Fabbriciani's fingerings work well for me with only minor tweaks, I will not provide a separate fingering table for this piece. However, these sounds were subject to spectral analysis and their notation sometimes indicates more detail than we actually perceive.Footnote 6 Could one purposefully enhance what may be artefacts of analysis?

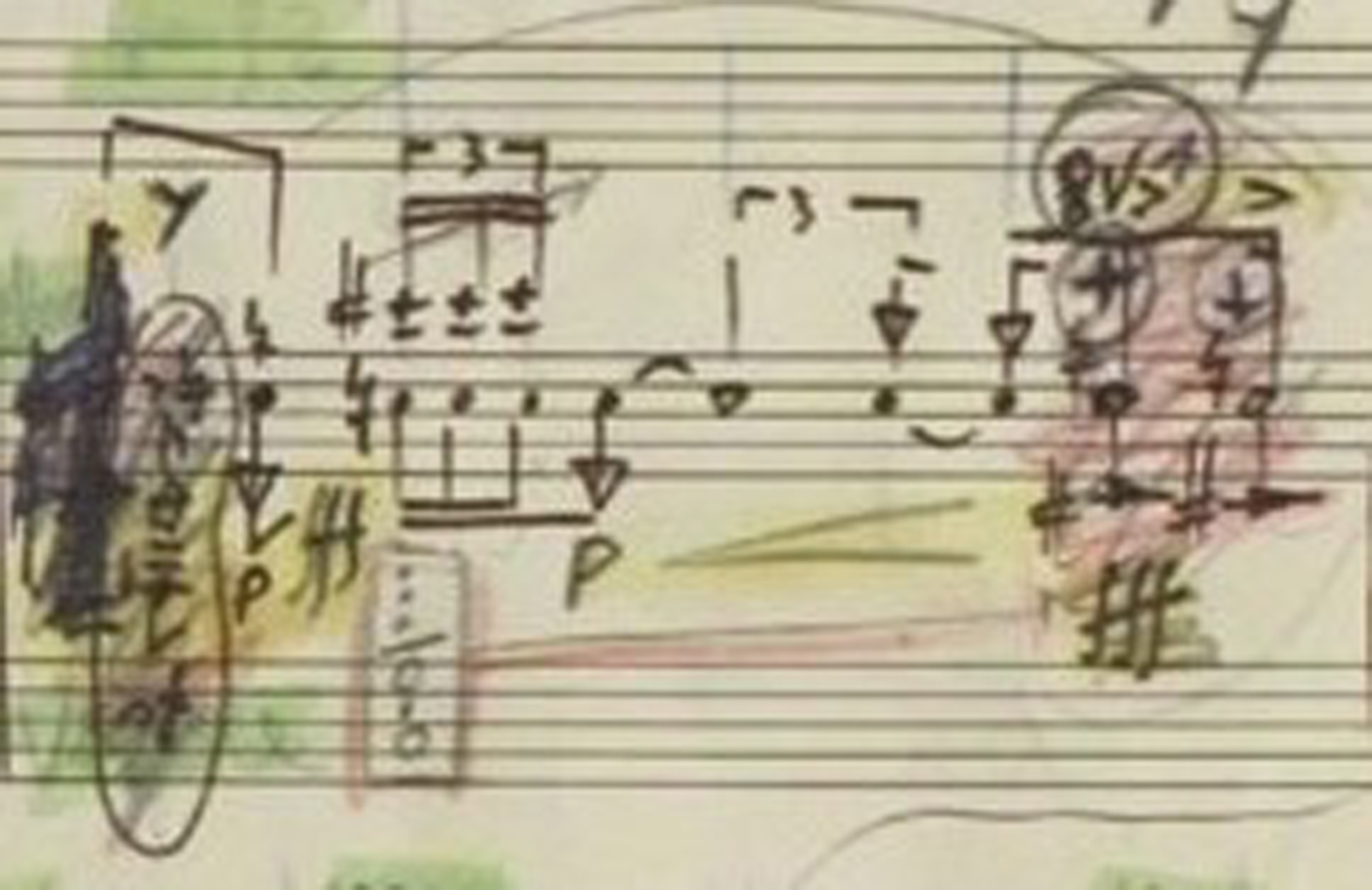

One possibility for deliberate enhancement could be found in bar 6 (see Examples 4 and 5). According to the manuscript it is clear that this passage is a rhythmicised fluctuation of the separate notes of a single multiphonic fingering. The printed score merely shows the aural result. If we were to take a descriptive interpretation, could one go so far as to enhance each note by subtly altering the fingering as in Example 6? Another example could be beats 3 and 4 of bar eight (see Example 7), which show a single multiphonic fingering, taken from Fabbriciani's manuscript, overblown to reach the upper partials of F and A. On my bass flute, Fabbriciani's given fingering does not produce the F, and indeed, one does not hear him produce it on the recording. Is the F an artefact of spectral analysis? Should I deliberately alter the fingering at this point in order to achieve this note?

Example 4: Luigi Nono, Das atmende Klarsein, bar 6.

Example 5: Luigi Nono, Das atmende Klarsein, manuscript, bar 6.

Example 6: Luigi Nono, Das atmende Klarsein, bar 6 with possible fingering alteration.

Example 7: Luigi Nono, Das atmende Klarsein, bar 8 with possible fingering alteration.

I will mention two examples here of what I consider to be misinterpretations of the manuscript.

One can see from examination of the score and manuscript in Examples 8 and 9 that the diamond-shaped symbols belong on the stems of the last two notes of the bar, indicating an airy sound, and not above the notes as printed, which could be intuitively interpreted as a harmonic indication. In Example 10 the multiphonic under the fermata and the gesture following it are misinterpreted. Examination of the manuscript and Fabricciani's recording reveals that there is no change of multiphonic here: the B and C# should remain. Personally, in this case I prefer to keep faith with the manuscript and not attempt to make a literal reading of the printed score. These questions arise naturally from experimentation with unconventional sounds, their analysis and conversion into conventional notation. Are they possible points of departure or unwanted tangents? It would be interesting to know Nono's point of view.

Example 8: Luigi Nono, Das atmende Klarsein, bar 15.

Example 9: Luigi Nono, Das atmende Klarsein, manuscript, bar 15.

Example 10: Luigi Nono, Das atmende Klarsein, bar 18.

Example 11: Luigi Nono, Das atmende Klarsein, manuscript, bar 18.

This brings us to the second over-arching question: in realising Nono's intentions represented in terms of an established performance tradition of another player, is my role that of a translator as well as an interpreter? Specifically, how do I distinguish Nono's intention from the collaborator's? How can I distinguish the collaborator's intentions from a notational fluke? These questions I will address in a more general way, since they apply not only to the flute part of Das atmende Klarsein and A Pierre, but to much of Nono's late instrumental writing. Indeed, these questions of interpretation can apply to most music. Interestingly, they apply more to pre-twentieth-century music than to the music of Nono's contemporaries. Nono's late works correspond to an older concept of music where the performance, not the score, is the crucial aesthetic arbiter for the value of the work.Footnote 7

According to Walter Benjamin, a philosopher, cultural critic, and translator whom Nono admired:

The higher the level of a work, the more it remains translatable even if its meaning is touched upon only fleetingly. This, of course, applies to originals only. Translations, in contrast, prove to be untranslatable not because of any inherent difficulty but because of the looseness with which meaning attaches to them.Footnote 8

If we view the role of interpreter as that of a translator, have we then the dubious task of translating that which is also essentially a translation? Nono is no longer with us, and we are only left with recordings and the advice of his collaborators as our reference. Since the score is not the final aesthetic arbiter of the work's value, I do experience a distinct looseness in the connections which join to form the path between the composer's ‘meaning’ and my performance.

Interpreting a musical work involves inhabiting the composer's world, crawling into their skin. Benjamin describes the content and language of an original work as a certain unity, like a fruit and its skin. However, the language of the translation envelops its content like a royal robe with ample folds.Footnote 9 How amply should I envelop the quirks of any other individual's performance, the vacillation between notes of a multiphonic, the amount of air used in tapering, the timing and flow between gestures?

The discomfort I feel with the lack of obvious possible points of departure in Das atmende Klarsein is ameliorated if I push the parallel of interpreter as translator just a bit further. Perhaps as a performer, one needs just a single point. Benjamin describes it thus:

Just as a tangent touches a circle lightly and at but one point – establishing, with this touch rather than with the point, the law according to which it is to continue on its straight path to infinity – a translation touches the original lightly and only at the infinitely small point of the sense, thereupon pursuing its own course according to the laws of fidelity in the freedom of linguistic flux.Footnote 10

Here the question of fidelity comes in to play, and he later describes how a translation should be transparent, allowing the pure language to shine upon the original more fully. A translation must give voice to the intentio of the original, not as a reproduction, but as a harmony.Footnote 11 The intentio of any work is of great importance for the translator's task of navigating between fidelity and license. Benjamin uses the metaphor of a broken vessel to visualise the relationship between the two concepts:

Fragments of a vessel that are to be glued together must match one another in the smallest details, although they need not be like one another. In the same way a translation, instead of imitating the sense of the original, must lovingly and in detail incorporate the original's way of meaning, thus making both the original and the translation recognizable as fragments of a greater language, just as fragments are part of a vessel.Footnote 12

How does one go about finding the intentio that binds what is originally Nono's to its translation, its performance? One can imagine the composer's intentio as being similar to the playwright's ‘super-objective’, as described by the Russian actor, producer, and theoretician Constantin Stanislavski in his book, An Actor Prepares. The whole stream of a dramatic play, all its individual, minor objectives, feelings and actions of the actor should converge to carry out this intentio. Stanislavski warns that if one interprets the intention as a theatrical or perfunctory object, it will give only an approximately correct direction. But if it is human and in verb form, it will be like a main artery that provides nourishment and life to the work and to the actors. He gives an example of his teacher's experience of performing Molière's Le Malade Imaginaire:

Our first approach was elementary and we chose the theme ‘I wish to be sick’. But the more effort I put into it and the more successful I was, the more evident it became that we were turning a jolly, satisfying comedy into a pathological tragedy. We soon saw the error of our ways and changed to: ‘I wish to be thought sick’. Then the whole comic side came to the fore and the ground was prepared to show up in the way in which the charlatans of the medical world exploited the stupid Argan, which was what Molière meant to do.Footnote 13

The dramatic role of the bass flute in Das atmende Klarsein is explained by Fabbriciani in the DVD that accompanies the score: the choir represents a nostalgia for the past, while the flute represents a nostalgia for the future. This is a recurring theme in Nono's late works, and the given premise of his work for violin, tape and electronics, La Lontananza Nostalgica Utopica Futura. This is an intent of the composer, but in order to distil an intentio which can be described in human terms and in verb form, one has to look further. Perhaps one could condense the ideas of distance, future and utopia by adopting a phrase Nono uttered, according to Fabbriciani, before the first performance of A Pierre: ‘non si deve capire niente!’ (‘one must not understand anything!’).Footnote 14 From a distance, one recognises and understands very little. If we allow this ambiguity to displace authenticity, it creates space for investigation and the emergence of a new utopia. Therefore, I believe this to be a strong intentio for both Das atmende Klarsein and A Pierre.

Nono's music is based on strong concepts and intentions that are crucial for its interpretation. Yet his musical scores are neither truly descriptive representations of musical results nor complete tablatures which give adequate instructions for instrumentalists of future generations. Interpretation must then rely on academic research or oral tradition. Could the outgrowth of musical concepts and sounds extend to ideas of what a contemporary musical score should contain? The DVD accompanying the score to Das atmende Klarsein is a giant, albeit labour-intensive, step in this direction. Should we consider new, critical editions of Nono's late works which contain this crucial information in the published scores?

Daniel Agi: Fingerings, Sounds, Historical Flutes – A Pierre from a flutist's perspective

The performer of A Pierre – Dell'Azzurro silenzio, inquietum is also confronted with the aforementioned questions. Unfortunately the score to this piece does not contain as much additional material as Das atmende Klarsein, therefore, some of the crucial technical questions are left open. No fingerings are given for the multiphonics that are used extensively throughout the composition. Moreover, it is unclear what model of flute Nono had in mind when writing the piece. In the second part of this article, I would like to examine A Pierre from the flutist's perspective. In addition to dealing with issues of tone production, I will address the essential question of what type of instrument the piece was written for – something the score leaves open. I discuss the practicalities of using the bass flute as an alternative for the contra-alto flute that Nono intended, and the article concludes with a catalogue of the multiphonics used in the piece with comments about their realisation on both instruments.

A sonic puzzle

Nono wrote A Pierre in 1985, on the occasion of Pierre Boulez's sixtieth birthday. The piece was premiered on 31 March 1985 in Baden Baden by Roberto Fabbriciani, the clarinettist Ciro Scarponi and the SWR Experimental Studio, which at the time was still known as the Experimentalstudio der Heinrich-Strobel-Stiftung des SWF e.V. Appropriately for the occasion, the work is 60 bars long. It reflects both the mutual respect and friendship that tied Nono and Boulez together and the conflict between two very different approaches to music after 1945. According to one anecdote, Nono intentionally created this piece as a sort of puzzle. He wanted to write a piece that was so convoluted that Boulez would be unable to make sense of how it was put together. And given the result, we can assume that Nono was successful in his attempt to breed a sense of confusion. To get a sense of just how opaque this piece is, I invite the reader to try to follow the score while listening to the piece.

This sense of disorientation begins with the fact that the amplified signals from each instrument are routed to the loudspeaker positioned next to the other player. The signals from both instruments are sent through a band-pass filter and into a harmoniser. These processed signals are then sent through two delay lines that delay the signal for 12 and 24 seconds respectively and finally the sounds are spatialised using an array of four loudspeakers.Footnote 15 The extensive use of air sounds, as well as similar timbres of the instruments in particular registers and dynamics,Footnote 16 also contribute to the veiled quality of the music. This leads to a continually changing soundscape in which it is often impossible not only to distinguish between the flute and the clarinet but also between the live playing and the delays. On the visual level, this effect is amplified by the following instruction in the preface to the score: ‘The players should … always maintain contact with their instruments, i.e. keep the mouth piece in the mouth. This also applies to passages with long rests and fermati in which the electronics continue to sound’.Footnote 17

Concerning the specific type of flute needed for A Pierre, the score specifies a ‘contrabass flute in G’,Footnote 18 a term that while found elsewhere in the literature does not accurately describe the flute required. The correct term for the instrument in question is sub-bass flute. This flute is in G and sounds an octave lower than the alto flute. At the time A Pierre was being written, these instruments were being developed and built by Christian Jäger. During this period, Jäger was director of the woodwind workshop at Hieber Music Company in Munich and was recognised as the pioneer in the area for low flutes below the range of the bass flute. Roberto Fabbriciani bought one of these flutes and demonstrated it for Luigi Nono, Peter Haller from the SWR Experimental Studio, and the clarinettist Ciro Scarponi.Footnote 19 Nono was clearly impressed by the instrument. After his initial introduction to and experimentation with the instrument he wrote the first bars of A Pierre that same day, and the opening of the piece was read through the day after.

According to the records kept in Max Hieber's workshop, Jäger built 23 of these flutes between 1982 and 1997. One had a 29 mm bore, 18 were made with a 34 mm bore, and four were built with a 43 mm bore. The two narrow-bore models have a curved head joint and are played horizontally like the bass flute. As a result of the 43 mm diameter, the wide-bore variant is correspondingly heavier and can therefore not be played horizontally. Accordingly, Jäger designed this model to be played vertically, standing on an endpin. In addition to increasing the weight and dictating the orientation of the instrument, the bore diameter also influences the timbral qualities and the range of the instrument. The narrow-bore flutes are weak in the low register and are slower to speak. In the higher registers, they are extremely flexible and are easy to overblow even in the third octave. Multiphonics and transitions between pitch and air sounds are easy to execute on these instruments. These are the exact characteristics that Nono takes advantage of in A Pierre when, for example, he asks for the seventh harmonic on d′ played pppp, or the multiphonic a′′′–e@′′′′Footnote 20 played ppp.Footnote 21

In contrast, the wide-bore 43 mm flutes have a markedly stronger low register compared to the narrow-bore models. At the same time, overblowing becomes difficult above the bottom half of the second octave, and the instrument's range is more limited at the upper end. If played with a large volume of air and fortissimo, the highest note b@′′′ can be reached, while the 29 mm flute that I played could easily reach the pitch g′′′′. The 43 mm flutes not were fitted with additional trill keys, which further complicates the search for multiphonics fingerings. These flutes are therefore not suited for Nono's piece (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Right: sub-bass flute in G by Christian Jäger, bore diameter: 29 mm Left: contra-alto flute in G by Michael Lederer, bore diameter: 43 mm.

The same is true for more recent designs that followed Jäger's great or sub-bass flutes, such as the contra-alto flutes built by other makers such as Eva Kingma, Jelle Hogenhuis and Michael Lederer. Like the sub-bass flutes, these instruments sound an octave lower than the alto flute. However, they are all manufactured with a bore diameter of 43 mm, which leads to dynamic characteristics and a smaller range that make them unsuitable for A Pierre. It is worth noting, however, that Michael Lederer told me that he intends to build a narrow bore instrument. Such an instrument would of course open up new possibilities.

At present, the correct flute for A Pierre is therefore a great or sub-bass flute by Christian Jäger with a bore diameter of 29 or 34 mm, which I will refer to as a Jäger flute in the following discussion. But Jäger only built 19 such instruments and getting access to one of these instruments is not easy. On the other hand, Nono's composition is a truly beautiful piece and also not particularly difficult to realise compared to Nono's other works for flute. It would be a shame if flutists were unable to take this piece into their repertoire just because the instrument it was written for is rare. This makes the question of an alternative to the Jäger flute all the more urgent.

The bass flute as an alternative

After my first attempts to find a narrow-bore Jäger flute were unsuccessful and I heard that the piece had already been performed on the bass flute, I began to work out a version for my bass flute (Eva Kingma, bore diameter ca. 38 mm, three ring keys). Comparing my experience working on this version with the version for the Jäger flute, it became clear that air sounds and pitched material did not blend as seamlessly into one another on the bass flute. The bass flute is clearer in the middle register compared to the Jäger flute, but it is much more difficult to play in the very high passages (especially bars 23–24 and 57–60) and the timbre has a much higher noise component,Footnote 22 while these same passages sound light and elegant on the Jäger flute.

The clear advantage of my bass flute, however, is that the multiphonics, such as those in bars 4 and 8 as well as 36 and 37, sound much more convincing than on the Jäger flute. In fact taken strictly, I was only able to find 17 good fingerings for the Jäger flute. In eight cases, I had to make do with rather approximate solutions.Footnote 23 My experience playing both types of flutes and the recordings that I have made of both versions have led me to the conclusion that the Jäger flute possess several clear advantages that make it the preferred choice for this piece. The timbral differences between the two flutes are well within the tolerable range, however, and the bass flute allows the performer to play the notated multiphonics more accurately. Thus, the bass flute is indeed a good alternative to the Jäger flute.

After deciding on a particular flute, the next step in the process of working on A Pierre is for the performer to find a way into the unique sound world of the piece. The preface to the score provides a few important pieces of advice about how the player can begin shaping the timbral dimension of the work. Even the title itself sparks our imagination: A Pierre – Dell'Azzurro silenzio, inquietum translates as ‘for Pierre, from the silent blue, restless’. Composed silences and pauses return continually over the course of the piece. Yet despite these frequent rests, the very slow tempo, and the preponderance of long held notes, short sound events periodically erupt, shining through the surrounding texture, perhaps creating the sense of restlessness described by Nono in the title. The piece needs a lot of air in the sound, even in passages where it is not explicitly notated. The multiphonics should be fragile and brittle. From my experience playing the piece, I feel it is better to view the noise and air components of the sounds as a natural result of the extreme dynamics in the piece that the performer should embrace rather than trying to consciously generate such sounds. By adopting this approach, the end result will be much more natural. The whistle tones in bars 6 and 7 should always be played with a good deal of air.Footnote 24 The whistling that recurs throughout the piece is notated as if it should sound simultaneously with the flute. However, this is only possible in a few passages, such as bars 8 and 45. Even in these passages, a continuous sound is not what is desired. The composer was looking for an unstable sound that oscillates between clear pitches, air sounds, and whistling. I was relieved to learn that this was the intention of these passages, especially given passages such as bars 53 and 44 where it is totally impossible to perform both at the same time. It is however important to sculpt beautiful transitions between the individual techniques.Footnote 25

Example 12: Luigi Nono, A Pierre – Dell'Azzurro silenzio, inquietum, bars 8 and 9, © 1985 Ricordi Music. The small back noteheads (B′′ and A′′) as well as the F#′′ under the indication ‘con fischio’ are to be whistled.

Nono had already explored the technique of simultaneously whistling and playing in Das atmende Klarsein. On the instructional DVD that is included with the score of this work,Footnote 26 it can be clearly seen that Roberto Fabbriciani whistles through his teeth. I prefer instead to whistle through puckered lips. This technique yields a similar tone quality. Moreover, the position of the lips in this style of whistling is closer to the flute embouchure, which makes it easier to negotiate the transition between flute sounds and whistling. Concerning the performance of multiphonics, the following sentence from the preface helps to clarify the composer's intention: ’ … the components of dyads and multiphonics [can] be played intermittently, in alternation, and simultaneously’.Footnote 27 On the recording that I was able to studyFootnote 28 this flexibility in interpretation can, for example, be observed at 0′38″ (bar 4). Here Fabbriciani plays both notes of the multiphonic in alternation.

Fingerings for the multiphonics

In this last section, I would like to list the multiphonics that I have compiled for the bass and Jäger flutes. Especially in the version for the Jäger flute, I had to, despite an intensive search for suitable fingerings, resort to substituting similar intervals for several of those indicated in the score, e.g. ninths and seventh. As a rule, at least one of the two notes is correct in such situations, and the resulting interval has a similar beating pattern to the intervals notated. Such multiphonics are commented in Table 1. The flutist Maruta Staravoitava, who worked with Fabbriciani on Nono's works for flute, has assured me that this is the common performance practice with this piece. I would be thrilled to see this list expanded upon; any of my colleagues who find alternative fingerings are welcome to get in touch with me.

Pitches are rounded off to the nearest 1/8 tone (25 cents). The intonation and playability can of course vary from player to player and flute to flute. The multiphonics based on the standard fingerings in the first octave (normal double harmonics like those found in bar 1) have been omitted from the list. All pitches are based on the pitches fingered, and as such sound an octave or an octave and fourth lower depending on the instrument.

Table 1: Multiphonics for Luigi Nono, A Pierre

N.B.: The bass flute for which this table is written has a thumb key with a triple mechanism. If all three holes on the left side of the diagram or just the two lower holes are closed, this operates the b@ and the b key respectively. If only the lowest hole is closed, the b key is opened halfway. This way it is possible to play an exact quartertone above b′ and b″.