Introduction

Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) is the most widely recommended psychological intervention for mental health conditions in the United Kingdom [e.g. National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE)], in America [e.g. American Psychiatric Association (APA) Steering Committee on Practice Guidelines] and many other countries.

However, the issues around the use of CBT in different countries and cultural groups are twofold. Firstly, literature confirms that the rates of recruitment, retention and engagement of ethnic minority participants in most randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of CBT (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Smith and Turkington2005) are low in high and middle income countries (HMIC).Footnote 1 Therefore, there is limited evidence of its effectiveness in minority communities in these countries.

Secondly, the majority of trials of the effectiveness of CBT have been conducted in HMIC. Therefore, the evidence base of the effectiveness of CBT in LMIC1 populations is still developing. Further literature comes from qualitative studies (Scorzelli and Scorzelli, Reference Scorzelli and Scorzelli1994) that demonstrate that principles underlying cognitive therapy can conflict with the values and beliefs of different cultural groups in the LMIC.

The last two decades have seen a trend towards cultural adaptation of interventions including CBT for ethnic minority people in the HMIC and the LMIC (Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Waheed, Gobbi, Ayub and Kingdon2010; Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Phiri, Harris, Underwood, Thagadur, Padmanabi and Kingdon2013; Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Pinninti, Turkington and Phiri2015; Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Giga and Degnan2017a,b). Meta-analyses also confirm that culturally adapted interventions are effective, but it is not known what components of the adaptation have maximum impact in engaging people and improving outcomes (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Giga and Degnan2017a). It is understandable that some adjustments for minority communities in HMIC may differ from the adjustments required for the majority populations in LMIC and this may present challenges.

This paper discusses the need for adaptations of CBT despite the challenges, highlighting available adaptation frameworks, and then we describe the evidence-based adaptation framework for CBT developed by our group. We do not propose to present a systematic review or critique of all available adaptation frameworks as it does not fit the remit of this paper. We aim to orientate the CBT practitioner to the available options and generate interest in understanding adaptation techniques relevant to practising personalized CBT with individuals from different cultures.

Why adapt cognitive behaviour therapy?

Cognitive behaviour therapy was developed by Beck as a structured, present-oriented therapy for depression. It was designed to solve current problems by targeting and modifying unhelpful thinking patterns and belief systems using the cognitive model (Beck, Reference Beck1964). Automatic thoughts and schemas were explained by Clarke and colleagues (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Beck and Alford1999). Over time, benefits of CBT have been realized for many conditions like anxiety disorders, borderline personality disorder and psychosis through case series, RCTs and meta-analyses.

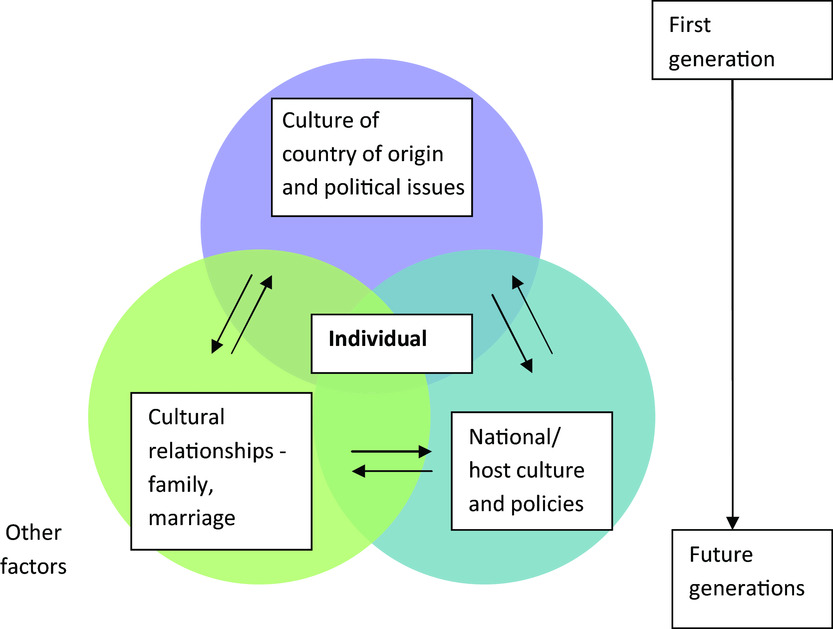

In CBT, the therapist explores the person's beliefs and experiences to elicit cognitive biases, emotions and behaviours to develop a formulation and treatment plan. Culture influences an individual's life experiences, belief systems and assumptions. As a result, it impacts on the psychopathology of mental illness. Therefore, it follows that culture shapes beliefs about health and illness, pathways into care, and trust in services.

Figure 1. Role of culture in CBT model. Reprinted with permission from Rathod et al. (Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Pinninti, Turkington and Phiri2015).

Cultural differences in life philosophies (Okasha and Okasha, Reference Okasha and Okasha2000) are well documented. The risk of continuing to practise CBT in different cultural groups without adaptation can be disengagement and poor outcomes of therapy (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Smith and Turkington2005). Additionally, it may affect the therapeutic relationship with the therapist which is central to any therapeutic intervention, again, leading to poor outcomes. The therapist may feel relatively incompetent (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Pinninti, Turkington and Phiri2015) as a consequence.

CBT is an evidence-based, pragmatic, collaborative therapy that emphasizes the critical role of cognitions, emotions and behaviours and therefore lends itself to adaptation while maintaining fidelity to the core CBT techniques (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Pinninti, Turkington and Phiri2015). Often, people from different cultural backgrounds struggle to trust the health systems, mainly mental health services (Schwarzbaum, Reference Schwarzbaum2004), especially in developed countries. The fundamental principles of CBT based on engagement and working together, can help diffuse the mistrust if the therapy appeals to the individual's cultural values.

A further argument is that CBT addresses relationships and not only cognitions and beliefs. The cognitive model of CBT suggests that the focus of therapy is on an individual's relationship (1) with self, (2) with others and (3) with the future. In many Eastern cultures family and community play a central role and are often sources of support, although changing values in many non-Western cultures might mean the nature of relationships is changing. Therefore CBT lends itself to successful adaptation, using the family and community networks as collaborators in the process where appropriate.

Frameworks for cultural adaptions of interventions

Any attempts to adapt therapy to culture have challenges. There could be a tendency to over-generalize and stereotype to cultures and subcultural groups. Maintaining fidelity to the core intervention while adapting to culture is an important consideration. Despite the challenges, local adaptations are occurring globally, based on therapists’ experiences and local population needs with some benefits. Examples include studies by Carter and colleagues (Reference Carter, Sbrocco, Gore, Marin and Lewis2003), Hinton and colleagues (Reference Hinton, Pham, Tran, Safren, Otto and Pollack2004), Kubany and colleagues (Reference Kubany, Hill and Owens2003), Patel and colleagues (Reference Patel, Araya, Chatterjee, Chisholm, Cohen and De Silva2007), Rahman et al. (Reference Rahman, Malik, Sikander, Roberts and Creed2008), Rojas et al. (Reference Rojas, Fritsch, Solis, Jadresic, Castillo and González2007) and Nagel et al. (Reference Nagel, Robinson, Condon and Trauer2009).

Numerous adaptation frameworks and guidance have been developed over time to aid this process. The first adaptation framework was published by Bernal and colleagues (Reference Bernal, Bonilla and Bellido1995), using Latino participants and based on the ecological validity model for cultural adaptation. This framework consists of eight elements: language, persons, metaphors, content, concepts, goals, methods, and context.

Bernal's model was further developed and adapted by Domenech Rodríguez and Weiling (Reference Domenech Rodríguez and Weiling2004), and then by Hwang and colleagues (Reference Hwang, Wood, Lin and Cheung2006) to extend its usability in different groups. Adaptation frameworks were developed by Tseng (Reference Tseng1999) describing the influence of culture on therapies. Resnicow and colleagues (Reference Resnicow, Soler, Braithwait, Ahluwalia and Butler2000) described two levels of cultural adaptation: surface structure adaptations and deep structure adaptations, while Leong and Lee (Reference Leong and Lee2006) developed an integrative and multi-dimensional cultural accommodation model.

Lau (Reference Lau2006), and later Barrera and Castro (Reference Barrera and Castro2006), developed adaptations consisting of systematic phases and a heuristic framework with specific emphasis on developing mechanisms that would allow for both measuring and evaluating the impact of cultural adaptations using specific outcome measures.

The models described above have similarities in the dimensions of adaptation, but differ in the level of detail, including the different cultural groups for which they were described. They have limitations in relation to cultures (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Pinninti, Turkington and Phiri2015) other than Asian and Hispanic groups. Hays and Iwamasa (Reference Hays and Iwamasa2006) attempted to address this. However, none of the previous adaptation frameworks has been tested through RCTs.

An evidence-based methodology to cultural adaptation of CBT

Our group has developed an adaptation framework that can be applied to CBT in different cultural groups. The adapted intervention has been evaluated through randomized trials (Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Waheed, Gobbi, Ayub and Kingdon2010; Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Gul, Irfan, Munshi, Asif, Rashid, Khan, Ghani, Malik, Aslam, Farooq, Husain and Ayub2015a,b; Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Phiri, Harris, Underwood, Thagadur, Padmanabi and Kingdon2013). Currently, this methodology and framework is being used to adapt CBT in Morocco (Fatema-Zahra El Rhermoul et al., Reference El Rhermoul, Naeem, Kingdon, Hansen and Toufiq2018), the Middle East and China (Li et al., Reference Li, Li, Luo, Liu, Liu, Lin, Liu, Xie, Hudson, Rathod, Kingdon, Husain, Liu, Ayub and Naeem2017).

The adaptation framework has been developed using a staged process. The first step has involved information gathering from literature and used the qualitative methodology, underpinned by the ethnographic approach. The process has ensured a co-production model with experts by experience, carers, lay members of minority communities and clinicians to develop the adaptation framework that is relevant. Emergent themes have informed development of the guidance used to deliver culturally adapted CBT that is personalized to an individual's culture. The therapy material or manual is then translated and culturally adapted in light of the guidance developed from the qualitative analyses and existent literature. The adapted therapy is field tested and further refinements are made based on the findings (Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Phiri, Nasar, Gerada, Munshi, Ayub and Rathod2016).

Table 1. Staged process of developing adaptation framework (Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Phiri, Nasar, Gerada, Munshi, Ayub and Rathod2016)

Foci of adaptation

Adaptation in our work has focused on three fundamental areas of delivery, which we refer to as the ‘Triple-A’ principle:

I. Awareness of relevant cultural issues and preparation for therapy. This can be further subdivided into: (a) culture and culture-related issues including religion and spirituality, family and community, and language and communication; (b) system and environmental aspects including individual capacity and circumstances, systems of support, services, and helpseeking pathways into care; and (c) cognitive biases and unhelpful beliefs that are directly related to the problem and its treatment.

II. Assessment and engagement.

III. Adjustments in therapy.

These areas and sub-areas are further discussed below in the framework of adaptation.

Framework for cultural adaptation of CBT

The process of adaptation starts with preparation for the therapy, i.e. pre-engagement phase as access to therapy, its delivery and most importantly availability for a given culture is as important as the actual modification of the intervention. The adaptation framework then progresses to engagement and assessment, followed by the therapy using relevant cultural adaptations to improve outcomes.

Rathod and colleagues (Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Pinninti, Turkington and Phiri2015) have developed a framework that encompasses the Triple-A principles for cultural adaptation of CBT focusing on the following aspects:

(i) Philosophical orientation;

(ii) Practical considerations of societal and health system-related factors;

(iii) Technical adjustments of methods and skills; and

(iv) Theoretical adaptations of concepts.

We have developed this adaptation model based on our work, using descriptions initially described by Tseng and colleagues (Reference Tseng, Chang and Nishjzono2005) and modifying them. The key principle is that every individual has a unique culture that is influenced by their wider culture, sub-culture and further developed through unique life experiences. There must be flexibility in applying the culturally adapted therapy, and clinicians should be aware of their own biases, and propensity to stereotype when working with people from minority groups. Below we briefly describe the framework that is explained in detail with case examples in the manual (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Pinninti, Turkington and Phiri2015).

Philosophical orientation or differences in world view

The fundamental view of life can be different between individuals and different cultures to a degree, and this can affect perceptions of health and illness, and relationship with services and professionals, including treatment and goals of therapy. Rathod and colleagues (Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Pinninti, Turkington and Phiri2015) describe philosophical orientation along the following constructs:

a. Acculturation – acculturation is the process of adjustment that involves integration of the original and new cultural values and attitudes. This can occur during the period of prolonged contact with the host culture after immigration or internal movement in countries. The blending of cultural values is often a gradual process (Garcia and Zea, Reference Garcia and Zea1997), and can occur over several generations. The process of acculturation can result in integration, assimilation, separation, and/or marginalization – describing different trajectories of individuals influencing behaviours when interacting with others (Berry, Reference Berry2005).

An individual can present with a mixture of different attitudes in different phases of life, through the influences of positive and negative life experiences and other factors. Figure 2 describes this. Understanding of an individual's level of acculturation helps to understand how to engage with them and develop explanations in therapy based on their value systems.

Figure 2. Oscillation of an individual's cultural values: Shanaya Rathod and David Kingdon (2009). CBT across cultures. Psychiatry 8, 370–371. Copyright ©2009 Elsevier Ltd; printed with permission.

Case example

Anish, a 30-year-old IT specialist, had been in the UK for three years when he developed symptoms of depression. The key stressors for him were job pressures, immigration and the need to adjust with loss of family support. He had not had enough time to integrate after migration. When he discussed his situation with his parents in Bangladesh, they called him home for a break. He, therefore, did not present to services, but on the other hand, family support mitigated against social stressors in the UK.

Discussion: This example demonstrates how the level of acculturation can influence behaviour in relation to access to services. In a different scenario, Anish may have been a second generation immigrant and could have been well integrated (identifies with both cultures) or assimilated (identify with the new culture) with the UK culture and used systems of care early.

b. Beliefs and attributions to illness: culture influences beliefs around health and attributions to illness. In many cultures, the mind and body are viewed as one. Therefore depression and other mental illnesses can present as somatic symptoms. As an example, the distress and symptoms of depression can be attributed to neurasthenia (meaning weakening of nerves) by some in the Chinese culture (Kleinman, Reference Kleinman1982). McCabe and Priebe (Reference McCabe and Priebe2004) discussed that biological explanations were much more frequently cited by Caucasians than African Caribbean and West Africans when describing symptoms of mental illness. Our research found key attributions around ‘previous wrongdoing’, supernatural beliefs, and social and biological factors in the sample of participants from South Asian Muslim, Black African and African Caribbean populations. Other attributions like the use of drugs and being arrested have also been quoted (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Phiri, Kingdon and Gobbi2010). Typical religious attributions can include ‘will of God or obeah (casting of an evil eye)’ by another.

Stigma plays an important role in cultural attributions to illness. Shame is often associated with stigma. Women can be more affected than men, especially within the South Asian Muslim communities. This gender difference can be attributed to gender bias including role expectations, rights and responsibilities.

In relation to cognitive biases, having a good cultural understanding of the individual's background may be helpful when considering cultural adaptations in relation to their assumptions, beliefs, norms and illness attributions. An understanding of the attributions helps clinicians in engaging people and addressing their distress.

c. Help-seeking behaviours defining pathways into care: an individual's attributions to health, illness and beliefs about health and illness often determine help-seeking pathways into care. Mistrust or trust for local services also dictates the speed of access by different communities. Some individuals may choose to seek help from their cultural or traditional healers first or in addition to conventional services. Understandably, delays in presenting to appropriate services may occur and prolong the duration of untreated symptoms.

Case example

Sadiq is a 21-year-old gentleman who developed early symptoms of psychosis. He was irritable with his family and spent a lot of time in his room. His family noticed changes in his behaviour and decided to send him to Pakistan and get him married. They thought that if he was given responsibility, he might ‘pull himself together’. On return to the UK with his wife, his mental state deteriorated further. He developed frank hallucinations and remained distracted and fearful. His parents took him to the local Mosque, and the Imam gave him a Taweez (arm locket). Six months later, he had been very unwell and finally his GP referred him to the local crisis team.

One of the key predictors of prognosis in psychosis is duration of untreated psychosis. In recognition of this key prognostic factor, the access and waiting time standard has been introduced in the UK (NHS England, 2015) and integrated care pathways have been developed that ensure early access to services and evidence-based interventions for first episode psychosis patients (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Garner, Griffiths, Dimitrov, Newman-Taylor, Woodfine, Hansen, Tabraham, Ward, Asher, Phiri, Naeem, North, Munshi and Kingdon2016). In Sadiq's case, the duration of untreated psychosis was 6 months before he presented to services. This example demonstrates how help-seeking pathways into care can influence access to services and awareness of how culture influences these pathways can help clinicians in understanding differing orientation to care and health.

Table 2. Cultural barriers to accessing therapy (from Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Pinninti, Turkington and Phiri2015); reproduced with permission from John Wiley and Sons)

d. Cultural orientation towards psychotherapy: cultural beliefs regarding interventions can define whether people from certain cultural groups will engage with therapies like CBT.

Practical considerations

There is a complex relationship between religion, politics and health services in any country. In some LMICs, social factors, like poverty, urbanization, internal migration and lifestyle changes, are moderators of the burden of mental illness and service provision (Rathod et al., 2017). It helps if clinicians and therapists understand to what extent policies promote integration with the other sectors such as justice, social care and development of services to ensure a more comprehensive (prevention, promotion and treatment) and holistic approach to the delivery of mental health services and experiences of individuals in the system.

Racism and effects

Racial discrimination is universal across cultures, even within diverse ethnic groups. This can apply to discrimination internally within LMIC or for minority groups in HMIC. When one is feeling vulnerable, it is difficult to talk about these experiences. Similarly, clinicians may avoid discussions about racism or discrimination. As a result, individuals can feel dissatisfied as they have not been able to discuss their main concerns in therapy. Sometimes therapists report that discussions about racism can be anxiety provoking; some admit to avoiding it due to fear of being politically incorrect or because they might say something that could easily be misinterpreted. Some therapists report that they do not feel well trained to address issues pertaining to racism or discrimination in therapy.

On the other hand, some individuals prefer talking about these problems to someone of the same colour or background as they feel they would be understood better. Moreover, they argue that a therapist from their background and colour would relate better to their experiences. A culturally competent therapist will need to recognize the potential significance of the experience of everyday racism and its impact on an individual's mental health. One has to acknowledge the disadvantages to meeting a therapist from the same background as well. This can include fear of loss of confidentiality in the community or fear of being judged.

Technical adjustments

This involves adjustment of methods, including the mode and manner of therapy and various clinical issues within the therapy for individuals of different backgrounds. Technical adjustment involves an understanding of:

a. Setting and environment of therapy: therapists use clinic setting or individual's homes and in some circumstances meet at an external venue. Meeting people in their homes gives the opportunity to see their home environments, neighbourhoods, social supports and meet family members. In either situation, the environment should be culturally welcoming; information should be available in appropriate languages and if needed interpreters should be used (Rathod and Naeem, Reference Rathod and Naeem2012).

In many LMIC distance and transport can be an issue. Individual adjustments including length and number of sessions need to be made. Technology can be an enabler, although connectivity can be a problem.

b. Therapeutic relationship: the therapeutic relationship or alliance is accepted to be one of the critical factors, if not the crucial factor, in determining the outcome of psychotherapy (Warwar and Greenberg, Reference Warwar and Greenberg2000). Therapists need to strive to build the therapist alliance at every stage of therapy including:

1. Engagement and assessment;

2. Individualized collaborative case formulation;

3. Effective sequential interventions based on the case formulation;

4. Relapse prevention and termination.

First impressions are important (Anez et al., Reference Anez, Paris, Bedregal, Davidson and Grilo2005). The personal style of the therapist can play a role in the development of therapeutic alliance. Some suggest (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Beatriz-Gambourg, Rivera and Laureano2006) a more personal and friendly style – which conveys warmth and trust – in the first session as helpful in fostering a therapeutic alliance.

Limited and measured personal disclosure in a safe manner is often a way of gaining trust. One may ask ‘how would you know how I feel?’. Therapists can answer using personal experience: ‘I do not as your experience is unique to you. However, I do know that we all have times of distress and how we feel during these times’.

Case example

Simi presented to a therapist in a very distressed state. She had lost her business and felt that she could never go on after this loss. Engaging her in treatment was very difficult as she felt extremely hopeless. After struggling for many sessions, the therapist chose to share a personal experience of surviving cancer with Simi and how they recovered and built their resilience after the illness. Simi engaged after this session and started rationalizing – ‘If you can survive this, I can also survive the loss of my business’.

Often limited self-disclosure is about building trust and respect more than the disclosing personal information.

c. Therapeutic style: Western therapists use the rational, collaborative and cognitive approaches to understanding the nature and origin of problems and coping strategies to deal with them. Eastern therapies stress the importance of experience and use meditation and mindfulness techniques. Therefore, there may be a mismatch of cultural values in therapy. However, an experienced therapist can use useful techniques that suit the individual by suitable adaptations.

d. Family structures and goals: in many cultures, families function as a unit and family members are closely involved in the therapeutic process. Families can be used as a strength as they can help engage individuals, help with homework and also provide the social support that aids recovery. The adverse impact of complex relationships also needs acknowledgment.

e. The role of religion: spiritual development is a vital part of all cultures (Laungani, Reference Laungani2004). Sometimes ignorance or interpretation of spiritual experiences as manifestations of psychopathology and lack of confidence can occur, which results in the key issue not being addressed. Clinicians in one study reported feeling disempowered when faced with the subject of religion and spirituality. The influence of religion and spirituality remains strong in Eastern cultures despite Westernization and acculturation (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Hean and Beverly2006). Some services flourish through close collaboration with religious institutions.

Theoretical modifications

Some changes in theoretical concepts need to be made for the best fit for an individual and their cultural strength. This can involve the use of different ways of explaining concepts. Some examples are cited below:

(a) Body and mind: in many cultures, the body and mind are considered one entity. The discussions used in therapy around the relationship between physical symptoms and mental illness reflect the holistic view of health and appreciation of this concept varies between cultures. Understanding what the individual values can be helpful in deciding explanations used in therapy.

(b) Self and ego boundaries: in some individuals from Eastern cultures, boundaries between self, family and society are narrow and influence interactions. For instance, the interdependent relationships with family and communities often determine how an individual seeks help.

(c) Individuality and collectiveness: when a therapist is insensitive to cultural norms and cultural explanations of idioms of distress, there could be obstacles in the cognitive and behaviour change processes, especially if the explanations used for change do not line with cultural values. In collectivist cultures, there is an interdependence with group members and the self is defined by group identity. Individuals prioritize communal needs over their own. In many Western cultures, the self is autonomous and independent of groups. Priority is given to personal goals, and the need often involves exchange relationships, i.e. ‘what's in this relationship for me?’.

Collaborative empiricism underpinning psychological interventions can be a challenge when working with people from LMIC. Some literature suggests that individuals take on a passive role as they probably would with their traditional healer or ‘guru’. However, if a therapist takes an overtly directive style they may be viewed by individuals as controlling (an agent of a dominant culture). Some individuals may respond better to a structured and prescriptive approach to therapy (Iwamasa et al., Reference Iwamasa, Hsia, Hinton, Hays and Iwamasa2006). Similarly, in some, exploration of opinions about the problem and collaboration may lead to doubts about the therapist's competencies, particularly when the locus of control is believed to be external and the individual has a desire for a quick fix. A paternalistic attitude can sometimes be more therapeutic.

Conclusion

This paper highlights the process, methods, foci and framework of cultural adaptation of CBT. As far as we are aware this is the first framework for adapting CBT for individuals from non-Western cultures that is evidence based. Adaptation of CBT can be accomplished through a series of steps that involve co-production with the key stakeholders. The process of adaptation should focus on both theoretical and philosophical considerations as well as on practical issues in improving access to therapy and in adjusting therapy techniques for the need of individuals and local population.

Main points

(1) Culturally adapted CBT shows better results in individuals from different cultural groups.

(2) Adaptation of therapy requires a robust methodology.

(3) Every individual has a unique culture that is influenced by their wider culture, sub-culture and further developed through unique life experiences.

(4) There must be flexibility in applying the culturally adapted therapy, and clinicians should be aware of their biases, and propensity to stereotype when working with people from minority groups.

Conflicts of interest

None of the authors has received funding to prepare this manuscript. The authors are experts in this field and have received research grants, lectured on the topic and published widely in this area.

Ethical statement

All authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the APA. Ethical approval was not needed for this paper as it does not present a trial.

Learning objectives

(1) To understand why the cultural adaptation of cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) is important.

(2) To understand the process of development of an evidence-based framework of adaptation.

(3) To learn adaptation techniques relevant to practising personalized CBT with individuals from different cultures.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.