Introduction

Up to 25% of women experience early pregnancy or baby loss before the age of 39 (Blohm et al., Reference Blohm, Fridén and Milsom2008). A grief reaction to such loss is normal, and may be expected. However, studies suggest that some women with experience of pregnancy loss are at increased risk of psychological distress which may require treatment (Cumming et al., Reference Cumming, Klein, Bolsover, Lee, Alexander, Maclean and Jurgens2007; Lok et al., Reference Lok, Yip, Lee, Sahota and Chung2010; Robertson-Blackmore et al., Reference Robertson Blackmore, Côté -Arsenault, Tang, Glover, Evans, Golding and O’Connor2011). In particular, rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression are elevated (Białek et al., Reference Białek and Malmur2020; Farren et al., Reference Farren, Jalmbrant, Ameye, Joash, Mitchell-Jones, Tapp and Bourne2016). PTSD is characterised by intrusive thoughts or memories, avoidance, negative alteration of cognition and mood, and hypervigilance, all of which may contribute to social, occupational and interpersonal dysfunction (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). PTSD may develop in response to experiencing a real or perceived threat, which in the case of pregnancy loss may include the sight of blood or foetal tissue, or subjective perception of experiencing the death of a baby (Farren et al., Reference Farren, Jalmbrant, Ameye, Joash, Mitchell-Jones, Tapp and Bourne2016).

Negative trauma-related beliefs about oneself, others, and the world play a prominent role in psychological models of PTSD (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000; Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Grey and Young2005). Post- pregnancy loss, women may report negative beliefs about their identity as and ability to be a mother, as well as intense feelings of guilt at not being able to prevent the loss (Evans, Reference Evans2012; Markin, Reference Markin2016). Guilt can strengthen unhelpful appraisals and prevent the traumatic memory from being processed due to avoidance (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000; Moulds et al., Reference Moulds, Bisby, Wild and Bryant2020), and may also generalise into a global negative self-evaluation, triggering feelings of shame (Kubany and Watson, Reference Kubany and Watson2003).

Grief response

The grief response following pregnancy loss is well documented as a type of ‘disenfranchised grief’ (Doka, Reference Doka1999). Unlike other losses, there are no standardised rituals to manage this grief, and there is often no physical manifestation of the loss to mourn (Fredenburg, Reference Fredenburg2017). Societal factors which discourage or make it difficult to openly acknowledge or publicly grieve pregnancy loss may leave women facing emotional and physical challenges alone (Kukulskienė and Žemaitienė, Reference Kukulskienė and Žemaitienė2022; Rowlands and Lee, Reference Rowlands and Lee2010). Stigma and misconceptions regarding pregnancy loss not only silence and obscure grief from others (Berry, Reference Berry2022), but may also contribute to the maintenance of PTSD as the trauma memory is not updated, nor are negative beliefs challenged.

Disentangling the grief response, which may include efforts to avoid reminders of the loss, emotional numbing, and a shattered world view from PTSD can be challenging for clinicians, with some conceptualising these two distinct responses as part of ‘traumatic grief’ or ‘complicated grief’ (Kersting and Wagner, Reference Kersting and Wagner2012). It may be useful here to refer to Duffy and Wild (Reference Duffy and Wild2023) for more information on enduring and prolonged grief reactions.

Current evidence base

There is a need for more robust research evaluating the effectiveness of interventions for PTSD or depression after pregnancy loss (Martin and Reid, Reference Martin and Reid2022; Shaohua and Shorey, Reference Shaohua and Shorey2021). The present evidence base is limited by studies offering only one treatment session (e.g. Nikčević et al., Reference Nikčević, Kuczmierczyk and Nicolaides2007; Sejourne et al., Reference Sejourne, Callahan and Chabrol2010), studies measuring anxiety and depression but not PTSD (e.g. Nakano et al., Reference Nakano, Akechi, Furukawa and Sugiura-Ogasawara2013), and studies not reporting findings in terms of clinically significant change (e.g. Kersting et al., Reference Kersting, Kroker, Schlicht, Baust and Wagner2011).

The evidence base for treating women during the perinatal period more broadly is also lacking; unfortunately, pregnant women are often excluded or severely under-represented in clinical research (Shields and Lyerly, Reference Shields and Lyerly2013). Treatment for PTSD after traumatic births may be drawn upon, but a review by Baas et al. (Reference Baas, van Pampus, Braam, Stramrood and de Jongh2020) highlights the scarcity of literature on birth-trauma topics despite 10% of women experiencing birth as a traumatic event (Stramrood et al., Reference Stramrood, Paarlberg, Huis In’t Veld, Berger, Vingerhoets, Weijmar Schultz and Van Pampus2011), and approximately 4% developing PTSD (Yildiz et al., Reference Yildiz, Ayers and Phillips2017). The evidence base is further muddied by unhelpful and inaccurate narratives suggesting that women in the perinatal period are unable to engage in therapy; thus, patients and professionals may postpone psychological treatment despite findings that therapy during pregnancy does not have adverse impacts (Baas et al., Reference Baas, Stramrood, Dijksman, Vanhommerig, de Jongh and van Pampus2023).

Treatment guidance

Although primary care NHS services do not work with grief through CBT, trauma-focused CBT may be offered where clinical symptoms of PTSD are present, as recommended by NICE guidelines (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2018). Both randomised controlled trials and studies in routine clinical settings find that trauma-focused CBT is efficacious in treating PTSD in a number of settings (Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Grey, Wild, Stott, Liness, Deale and Clark2013; Kitchiner et al., Reference Kitchiner, Roberts, Wilcox and Bisson2012).

However, there is limited guidance for treating co-morbid depression and PTSD (Rosen et al., Reference Rosen, Ortiz and Nemeroff2020). Some studies find that trauma-focused therapies are effective in reducing symptoms of co-morbid depression (Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Moulds, Guthrie, Dang, Mastrodomenico, Nixon and Creamer2008; Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Hackmann, Grey, Wild, Liness, Albert and Clark2014). However, recent studies highlight common residual post-treatment PTSD symptoms including insomnia, hyperarousal, irritability and difficulty concentrating, which are often part of depression (Larsen et al., Reference Larsen, Fleming and Resick2019; Schnurr and Lunney, Reference Schnurr and Lunney2019). A transdiagnostic approach has been suggested as a viable alternative; however, evidence for this is mixed (Gros et al., Reference Gros, Price, Strachan, Yuen, Milanak and Acierno2012).

As research demonstrates a reduction in depression with trauma-focused therapies, but not a reduction in PTSD symptoms with depression-only-focused therapies, Rosen et al. (Reference Rosen, Ortiz and Nemeroff2020) recommend treating PTSD first and evaluating residual depression symptoms after. This is in line with Barlé et al.’s (Reference Barlé, Wortman and Latack2017) guidance for treating traumatic grief in which a sequential approach is suggested whereby trauma must be processed before healthy mourning can occur. Overall, the lack of research and clear guidance in this area presents an issue.

Current study

The current case study explores the effectiveness of sequential CBT for co-morbid PTSD and depression in a working age adult within a primary care NHS service. Using a single case experimental design, the study proposes the following hypotheses in relation to sequential treatment:

-

(1) Trauma-focused CBT will lead to a reduction in symptoms of PTSD.

-

(2) Trauma-focused CBT will lead to a reduction in symptoms of depression.

-

(3) A depression-specific protocol will lead to a further reduction in symptoms of depression.

Introduction to case

In this paper we present the case of Mrs C, who has given permission for this paper to be written.

Mrs C is a white-British female in her early-40s who self-referred to NHS Talking Therapies (previously known as IAPT) for pain management after being diagnosed with a chronic pain condition. Mrs C completed six sessions of online guided self-help for pain management and low mood through fortnightly conversations with a Psychological Wellbeing Practitioner. During these sessions, she reported having a traumatic pregnancy loss five years ago which she had not previously spoken about. Mrs C was consequently seen for a PTSD assessment and was offered CBT with a trainee clinical psychologist.

While working as a senior midwife at her local hospital, Mrs C experienced an early stage ‘missed miscarriage’, where the foetus has died but the body has not begun the miscarriage process. In this case, the mother does not experience any physical symptoms of loss, such as bleeding or pain. These losses are usually diagnosed during the routine schedule of antenatal care, but as a member of hospital staff, Mrs C was offered a scan by a colleague during a break at work. As this scan was unplanned, Mrs C’s husband could not be with her at the time of the scan.

Upon learning about the pregnancy loss, the hospital staff verbalised the expectation that as a midwife, Mrs C should know what to expect from the process of medical management. She was sent home with medication to induce the process without being told how to prepare herself for physical symptoms which may include heavy bleeding, pain, cramps, vomiting and diarrhoea. Following the initial scan, the traumatic event spanned over two days, including a six-hour period during which there was significant blood loss, and the worst pain Mrs C had ever experienced.

Mrs C has subsequently had two young children, born in the two years following the pregnancy loss. Although Mrs C returned to work after her pregnancy loss, she later decided to stop working as a midwife after the births of her children and is now a full-time homemaker. She has a strong relationship with her husband who she describes as very supportive.

A risk assessment was carried out and Mrs C reported no thoughts of wanting to harm herself. At no point did she behave in a manner which indicated that her children were at any risk of being neglected or harmed.

Presenting difficulties

At assessment, Mrs C met diagnostic criteria for both PTSD and depression. Her pregnancy loss occurred five years prior to engaging in therapy and her symptoms had persisted since this time.

The trauma memory of the pregnancy loss was intrusive and elicited significant distress. It was also disjointed and Mrs C reported being unable to remember parts of it. As well as reoccurring and involuntary intrusive thoughts about the event, Mrs C also re-experienced physical sensations of the pain and cramping that she felt at the time of the pregnancy loss, which was subsequently triggered by menstrual pain. Although Mrs C did not dissociate, she reported that the memory felt vivid, like watching a movie of the incident.

Mrs C had not spoken about her pregnancy loss previously and actively avoided thinking about it. She also avoided any reminders of pregnancy loss; for example, she would change channels on the TV or radio if the topic was being discussed.

Mrs C reported changes in her thoughts and mood; she felt unable to control her emotions when reminded of the pregnancy loss and expressed an elevated sense of self-blame. There were also changes in her level of arousal and reactivity: she felt irritable, resulting in changes to her behaviour, and had problems with concentration.

Mrs C also met diagnostic criteria for depression; her daily mood was low, she had reduced interest or pleasure in activities, felt fatigued, had difficulty with concentration and experienced feelings of worthlessness and guilt. These difficulties had been present since the pregnancy loss.

Throughout the assessment, Mrs C was visibly distressed and found it difficult to talk about her symptoms. Her main goal of therapy was to regain a sense of control over the memory and not become emotionally overwhelmed when she was reminded of it.

Method

Design and procedure

A single case experimental design with an ABC design was used to evaluate the impact of a 15-session CBT intervention, which spanned over the course of 4 months. A baseline (Phase A) was established at three time points over the course of 3 weeks (during the PTSD screening appointment, prior to assessment session, and prior to the first treatment session). Phase B involved 8 weeks of trauma-focused CBT (tfCBT) based on Ehlers and Clark’s (Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) Cognitive Therapy for PTSD, and Phase C involved 5 weeks of depression treatment. Sessions ranged from 60 to 95 minutes and were delivered via MS Teams.

Measures

Mrs C completed the following questionnaires prior to each session. Each measure asks patients to rate on a 4-point Likert scale (from not at all, to nearly every day) how often they have experienced symptoms over the past two weeks.

Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001)

The PHQ-9 is a self-report 9-item measure of depression severity.

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL-5; Weathers et al., Reference Weathers, Litz, Keane, Palmieri, Marx and Schnurr2013)

The PCL-5 is a self-report 20-item measure of PTSD severity.

PTSD intervention: Phase B

In line with NICE guidelines, Mrs C was offered cognitive behavioural therapy for PTSD (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2018). This involved psychoeducation, developing a shared formulation, reliving, hotspot updating, and elements of reclaiming and rebuilding life work.

Psychoeducation was used to help Mrs C understand and normalise the causes, threat response, and common symptoms of PTSD. Mrs C initially found talking about the trauma very difficult, she was distressed and tearful during the sessions. Due to Mrs C’s distress, she was unable to give specific examples of her coping strategies or beliefs, so a generic maintenance cycle was discussed as if speaking about a second person with a different trauma (road-traffic accident).

To help Mrs C regulate her emotions, reminders of the ‘here and now’ were used, including looking around her and naming objects she could see, touch, hear, smell and taste, naming differences between the time of the trauma and present day, and standing up and moving her body, which she was unable to do at the time of her loss. Mrs C also found trigger discrimination beneficial in differentiating between period pain cramps, and cramps she experienced at the time of the pregnancy loss. These strategies helped Mrs C regain some control over her physical symptoms such as her rate of breathing, and also enabled Mrs C to stay within her window of tolerance of anxiety enough for the events to be spoken about. Mrs C reported that these techniques helped her to regain control of her emotions and say the words out loud that she had been unable to say before.

Formulation

A cognitive behavioural formulation was collaboratively developed with Mrs C based on Ehlers and Clark’s (Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) model. This initially involved looking at maintenance cycles, and later incorporating her prior experiences. Mrs C saw that her avoidance of thinking or talking about the pregnancy loss was maintaining her PTSD as she was not able to process the memory or challenge her beliefs about herself (e.g. her belief that she had caused the pregnancy loss).

Further exploration of Mrs C’s prior experiences allowed Mrs C and the therapist to see that Mrs C always had high expectations of herself and this contributed to her negative appraisals of herself, leading to further avoidance. As Mrs C believed that there was something wrong with her emotions, she did not discuss them with others, and perceived her trauma response as invalid.

Mrs C also recognised that the unprocessed trauma may have impeded a healthy mourning process, shown diagrammatically in Fig. 1 as ‘unaccessed grief’. It was hypothesised that processing the trauma and reducing distress related to guilt may enable Mrs C and her husband to address the grief and mourn the loss they experienced.

Figure 1. Post-traumatic stress disorder formulation developed in collaboration with Mrs C.

Working with avoidance

At the beginning of treatment, Mrs C expressed a fear that if she talked about her pregnancy loss, she would become so upset that she would not be able to cope with her emotions. By looking at the anxiety curve and an in-session behavioural experiment, Mrs C learnt that her anxiety response did reduce, and that she was able to use her breathing and here and now reminders effectively. This initial recognition of avoidance maintaining her PTSD symptoms helped Mrs C understand the rationale for reliving.

The standard protocol for reliving was then followed (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000). Mrs C identified hotspots and other incidences linked to intense emotions such as anger, sadness, shame and guilt. The personal meanings of the trauma which were inducing a current sense of threat in Mrs C were explored and are shown below in Table 1. Once the updating information had been identified, Mrs C and the therapist worked to actively incorporate it into the hotspots. This was done by bringing the hotspot to mind and then verbalising the new information (e.g. ‘I know now that…’).

Table 1. Mrs C’s hotspots with updated re-scripts

Sessions 5 to 8 were focused on updating these hotspots through collecting evidence based on what Mrs C knows now. Due to the high levels of avoidance between therapy sessions, the therapist suggested they begin with updating a hotspot with the associated belief that Mrs C’s husband had chosen not to be there with her at the time of her scan. The meaning of this was explored and Mrs C expressed a belief that her husband did not care as much as she did. When reviewing the evidence, Mrs C realised that it was not physically possible for her husband to be present at the scan, as the scan was unplanned and her husband was in a different city at the time. Mrs C was asked to rate the strength of her beliefs before and after each update, with her rating dropping from 80% to 30% for her first update. Updating this hotspot also encouraged Mrs C to engage in a conversation with her husband to disrupt avoidance between sessions.

Throughout sessions, Mrs C continued to plan homework tasks to reduce her avoidance, including writing up her hotspot updates on cue cards which she put up around her house. She reported initially finding them hard to verbalise out loud, but this became easier over time. During sessions, Mrs C practised the updates and found that her emotional distress lessened; session 9 was the first session in which Mrs C did not cry.

At the time of therapy, Mrs C had gone on to have two further children since the pregnancy loss occurred, and so there was no rationale to work on an avoidance of intimacy or a fear of future pregnancies.

Working with guilt

Socratic questioning helped Mrs C verbalise her fear that she was responsible for the pregnancy loss due to eating an item of food not recommended for pregnant women and consequently contracting listeriosis. Mrs C was asked to imagine what she as a midwife would say to a patient who also held this belief. She reported that although she ‘logically’ knew it was unlikely she had caused the pregnancy loss, the belief was still strong. Mrs C and the therapist discussed this ‘head heart lag’ (Stott, Reference Stott2007) where guilt persists despite rationally agreeing with the information being integrated into the trauma memory. To strengthen the update, the therapist and Mrs C researched the link between the item of food and pregnancy loss for homework. In the following session, Mrs C and the therapist did the mathematical calculation together based on a large-scale epidemiological study found by the therapist, which suggested that the probability of pregnancy loss was 0.000294. Mrs C reported that upon discussion with her husband, they had additionally realised that she did not have any symptoms of listeriosis. This led to an initial shift in Mrs C’s guilt.

Despite knowing that she had not caused the pregnancy loss, Mrs C’s guilt persisted as she felt that as the mother, she should have protected her baby. Kubany and Watson (Reference Kubany and Watson2003) propose perceived responsibility for the outcome as a key underlying cognition of affective guilt. A discussion around Mrs C’s inability to control other bodily functions, including her body’s pain response and her hormone levels when pregnant with her other children led to a shift in her belief that she should have been able to control her body and stop the pregnancy loss.

Working with shame

Before session 7, Mrs C’s PCL-5 scores increased from 33 to 36, which she attributed to the anniversary of her pregnancy loss. When this change in her scores were discussed, Mrs C stated that she felt embarrassed at her ‘weakness’, as she believed she should not be so distressed 5 years after the pregnancy loss. During this session, she and the therapist co-designed a survey to explore other peoples’ beliefs about whether someone experiencing distress years after a pregnancy loss is weak. The results of the survey demonstrated that other women also felt distressed years after a pregnancy loss. This was powerfully normalising and contributed to a large shift in Mrs C’s core belief from ‘I am weak’ to ‘I feel vulnerable’.

Working with loss

Mrs C and the therapist addressed the belief that Mrs C should continue to carry the pain and distress with her to show the baby she cared for it. The relationship between closeness to a person and grief response was explored: Mrs C and the therapist discussed examples of others they knew who had experienced loss and their varying emotional responses. The loosening of this belief was supported by motivational strategies exploring the benefits and disadvantages of holding on to these feelings, with the negative consequences enhanced. Mrs C was able to see that holding on to the pain was stopping her from living in accordance with her values and that there may be alternative ways to honour her baby in a meaningful way. Mrs C and her husband decided to write a letter to their baby which they would then burn and scatter the ashes of.

Reclaiming and rebuilding life work

Homework tasks from the end of each of the treatment sessions included elements of reclaiming and rebuilding life work with the aim of improving mood and building hope. These included Mrs C planning regular self-care activities, quality time with her husband, and social activities with friends. These tasks also serviced to disrupt cycles of avoidance and supported with processing grief: Mrs C was encouraged to discuss the pregnancy loss with her husband and close friends.

Depression intervention: Phase C

Given the improvement in Mrs C’s symptoms of PTSD, the focus of treatment in Phase C became the symptoms of low mood which were felt to be remaining. The reclaiming and rebuilding activities that were used during the PTSD treatment were built upon to support Mrs C to actively grieve, seek support, and reengage in meaningful activities.

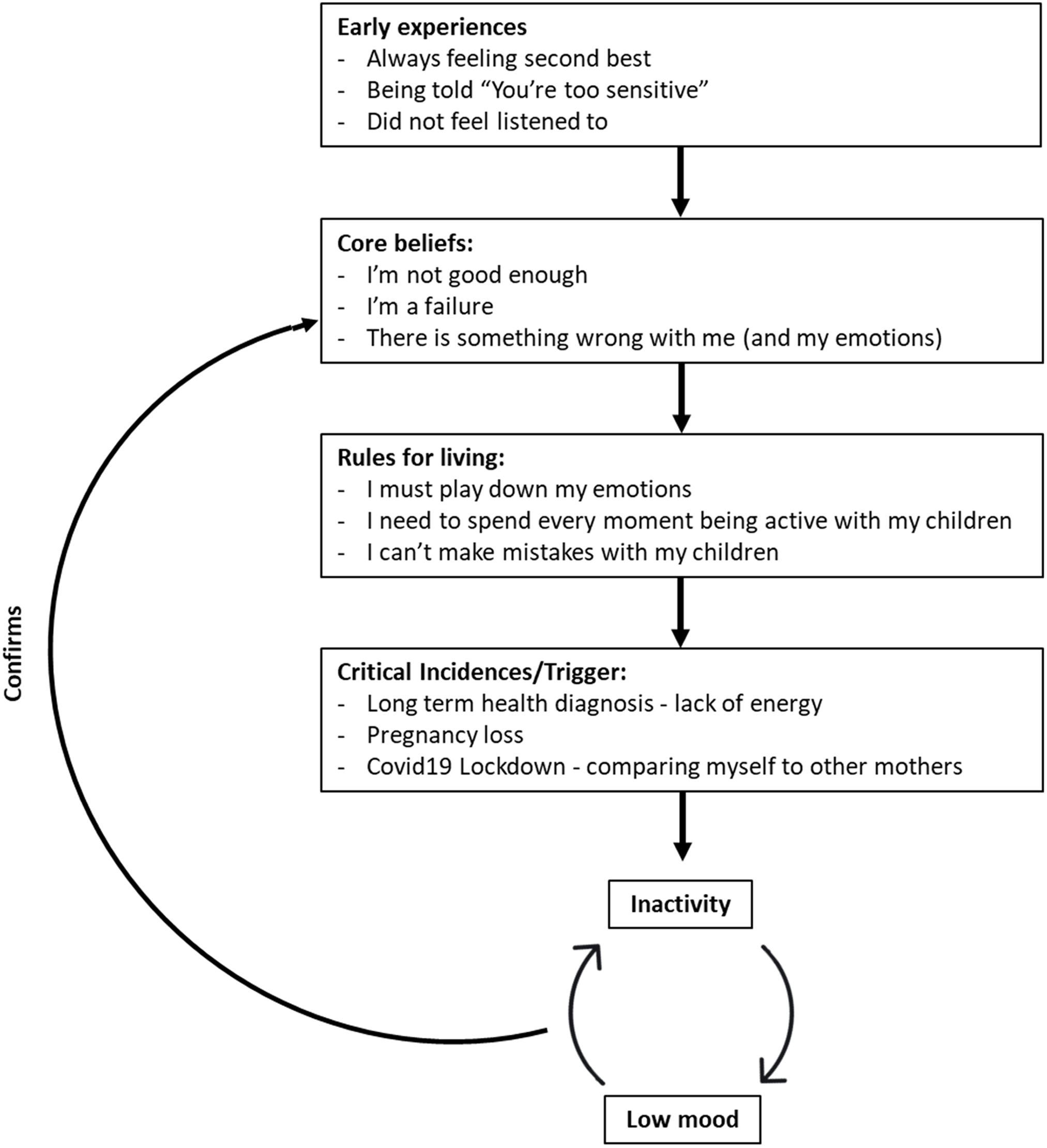

A formulation of how Mrs C’s low mood came about and was being maintained was developed together using Beck’s longitudinal formulation model (Fig. 2; Beck et al., Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979). Mrs C and the therapist explored the link between her low mood and her trauma, whereby her response to the pregnancy loss reinforced her core beliefs about being a failure and there being something wrong with her emotions.

Given the similarities between reclaiming and rebuilding life work and behavioural activation, Mrs C was familiar with ideas of monitoring mood and levels of activity and reducing avoidance. The relationship between her mood and levels of activity were reviewed in the context of loss; Mrs C noted that when her mood was low, she was less active, and this in turn meant that she had less social engagement, enjoyment, and less opportunities to integrate her loss into her life.

Mrs C’s activity planning was done in the framework of her values and what was important to her. She set herself goals in line with each value and noted an improvement in her mood which she attributed to a sense of achievement. However, she realised that she often felt exhausted and in pain after activities that she felt she should have enjoyed. When thinking about goals for the following week, Mrs C and the therapist explored the Boom-Bust cycle of pain (Birkholtz et al., Reference Birkholtz, Aylwin and Harman2004), and the importance of pacing activities.

Alongside behavioural activation, Mrs C was encouraged to explore whether her core beliefs of not being good enough, feeling like a failure, and that there is something wrong with her emotions were linked to early childhood experiences. Mrs C kept a thought diary for the week to reappraise some of her negative automatic thoughts. This helped her and the therapist identify consequent ‘rules for living’, included trying to feel ‘good enough’ by spending all of her time being active with her children. Cognitive restructuring was used to help Mrs C reframe her beliefs about herself and reappraise her expectations. Mrs C felt that she was unable to spend as much time as she wanted to engaging in activities with her children, and the subsequent mismatch between her high expectations and experience of reality contributed to low mood and guilt, which reconfirmed her core belief that she was not good enough. She was encouraged to weigh up the objective evidence for her beliefs to reappraise them in a manner similar to updating her trauma hotspots.

Ending therapy

Mrs C met her goals for therapy; she was able to talk about her pregnancy loss without feeling emotionally overwhelmed, and at the end of therapy she discussed the benefits of speaking about her pregnancy loss with a close friend. Throughout therapy Mrs C was empowered to make decisions she felt unable to make at the time of her pregnancy loss, including writing to the hospital about her experience as a patient. Through understanding the maintenance of her low mood, Mrs C was able to better pace her activities and challenge her negative automatic thoughts, although she noted that her chronic pain continued to negatively impact her mood.

During the final session Mrs C completed a therapy blueprint, which included details about what she could do if symptoms returned, her learning points from therapy, therapy gains, her strengths, and who she could speak to for further help and support.

Results

Figure 3 depicts Mrs C’s symptoms of PTSD from referral to the end of treatment. Her average baseline score on the PCL-5 was 36, and her score post-treatment was 19, indicating a reduction in PTSD scores to below clinical levels. Scoring above 31 on the PCL-5 is indicative of PTSD being present. Figure 4 depicts her symptoms of depression, from a baseline of 11.33 on the PHQ-9 to her score post-treatment of 9.67, demonstrating a small reduction of presenting symptoms.

Figure 2. Longitudinal depression formulation developed collaboratively with Mrs C.

Figure 3. Graph showing changes in PTSD symptoms according to the PCL-5, where scores above 31 of a total 80 indicate the presence of PTSD. Phase A = assessment and baseline, Phase B = trauma-focused CBT, Phase C = CBT for depression.

Figure 4. Graph showing changes in depression symptoms according to the PHQ-9, where scores of 5, 10 and 15 indicate mild, moderate and severe depression, of a total score of 36. Phase A = assessment and baseline, Phase B = trauma-focused CBT, Phase C = CBT for depression.

Discussion

This paper presents a real-life application of CBT for the treatment of PTSD and depression. The results from this case study are consistent with research supporting the efficacy of trauma-focused CBT while adding to the limited literature for pregnancy loss as a traumatic event. In line with our first hypothesis, there was a clinically significant reduction in PTSD scores following trauma-focused CBT in Phase B, and PTSD scores continued to drop during Phase C when a depression-specific protocol was used. This case therefore provides further support for CT-PTSD being an effective treatment for PTSD following pregnancy loss. Our second and third hypotheses, that trauma-focused CBT would lead to a reduction in symptoms of depression, and that a depression-specific protocol would lead to a further reduction in symptoms of depression, were not met. Trauma-focused CBT did not contribute to a reduction in depression symptoms, and symptoms persisted in Phase C.

Since completing treatment with Mrs C we have reflected on the possible reasons why her depression symptomology persisted. One possibility is that Mrs C’s grief could have played a key role in her ongoing depression symptoms. It is hoped that this piece of work allowed Mrs C to begin her grieving process, thus enabling continued improvement of her mood after the end of therapy. Follow-up scores may have elucidated the long-term impact of processing the trauma on her low mood. Another consideration is whether a sequential approach to treating PTSD and depression as separate disorders was the most suitable approach. Negative appraisals about the self (such as ‘I am weak’, ‘I am a failure’) are common in PTSD and can drive sadness, low mood, and other depression symptoms. It is possible that formulating both depression and PTSD together, especially given Mrs C’s mood deteriorated following the trauma, may have been a more effective approach. In this case, an earlier focus on reclaiming/rebuilding life work and on Mrs C’s negative appraisals about herself could have been helpful. This would have allowed more time for Mrs C to address some of her persistent negative self-appraisals; for example, keeping a positive data log that ‘I am a good and loving mother’ over the course of treatment.

Furthermore, earlier work and more time to address loss appraisals, including more work on how Mrs C could take her baby with her and imagery work may have been helpful. There were also CT-PTSD interventions, such as a site visit, that were not used with Mrs C. At the time, it was felt that a site visit was not needed as the site was Mrs C’s home and the hospital she had since returned to. However, site visits can still be a helpful way to integrate new meanings discovered in treatment into trauma memories, even if the patient has been to the site many times before. They can also be an opportunity to say goodbye to the loved one in a more peaceful way than the trauma allowed; for example, by bringing to mind imagery of the loved one at peace at the site or a peaceful act, like lighting a candle at the site. These reflections are in line with Kerr et al.’s (Reference Kerr, Warnock-Parkes, Murray, Wild, Grey, Green, Clark and Ehlers2023) recent clinical guidance paper on working with clients with birth trauma and baby loss and recommendations for working with traumatic bereavement from Wild et al. (Reference Wild, Duffy and Ehlers2023), both published after the treatment of this case.

A strength of this case study is Mrs C’s engagement in sessions. Although drop-out rates for trauma-focused CBT can be high (Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, Greene, Russ, Dutra and Westen2005), in this study, both client and therapist were motivated; Mrs C did not miss any sessions and completed all homework tasks collaboratively set. A safe space was created in sessions and both Mrs C and the therapist understood the rationale for reliving and therefore did not avoid or delay its use, as can often happen (Becker et al., Reference Becker, Zayfert and Anderson2004; Frueh et al., Reference Frueh, Cusack, Grubaugh, Sauvageot and Wells2006). Mrs C reported knowing that her symptoms may worsen through reliving before improving helped her prepare for the sessions.

Mrs C benefited from the support of her husband, who did not attend sessions given the limited scope of therapy. However, it is important to recognise the impact of pregnancy loss on partners and family systems. Chavez et al. (Reference Chavez, Handley, Lucero Jones, Eddy and Poll2019) report that 42% of men describe emotional trauma both during and following pregnancy loss, and McGarva-Collins et al. (Reference McGarva-Collins, Summers and Caygill2022) document intrusive and re-emergent chronic grief reactions in partners who felt the need to act up to male stereotypes in their qualitative study. Providing partners with information, support, and recognising their experiences of loss will contribute to the provision of optimal care (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Ma, Davies and Kammers2023).

Future case studies should consider the use of additional measures, such as the Post Traumatic Cognitions Inventory (PTCI; Foa et al., Reference Foa, Tolin, Ehlers, Clark and Orsillo1999), and measures for grief response. Measuring grief, low mood and PTSD outcomes in parallel would enable a better understanding of the relationship between this type of trauma and bereavement. Such work may also inform guidance around disentangling traumatic grief from depression at assessment.

In summary, the current study demonstrated that trauma-focused CBT was efficacious for treating PTSD but highlights a possible need to address low mood and PTSD jointly, including more interventions to target negative self-appraisals and work on reclaiming/rebuilding life earlier in treatment. Further research is needed to define optimal treatment choices for those experiencing pregnancy loss, as well as to better understand the complex picture of grief, depression and PTSD.

Key practice points

-

(1) Trauma-focused CBT can be used effectively for treating PTSD related to pregnancy loss.

-

(2) Identifying the meaning of hotspots in relation to grief is necessary for processing this type of trauma.

-

(3) Clinicians should consider formulating and addressing PTSD and low mood jointly rather than treating sequentially.

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Mrs C for her generosity in sharing her experiences for this paper.

Author contributions

Hibah Hassan: Conceptualization (lead), Data curation (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Methodology (lead), Project administration (lead), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (lead); Natalie Holmes: Supervision (lead).

Financial support

None.

Competing interests

There are no known competing interests.

Ethical standards

The author has abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. Consent was obtained from the client, who has seen the submission in full, had the opportunities to comment on and request changes, and has agreed to it going forward for publication. Ethical approval was not required as this case study was conducted within an IAPT service using routine outcome measures and the client completed the standard IAPT consent form around data governance. A standard protocol was following as recommended by NICE guidance. The client also signed a consent form giving permission for an anonymised account of work with them to be submitted to a professional publication.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.