Introduction

Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) is characterised by recurrent obsessions (intrusive, persistent, unwanted thoughts or images) and/or compulsions accompanied by marked distress and impairment in daily living (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Cognitive behavioural explanations of OCD (e.g. Salkovskis, Reference Salkovskis1985) postulate that normal intrusive thoughts can become clinical obsessions when the thought is interpreted by an individual as having personal significance and are ego-dystonic (Salkovskis, Reference Salkovskis1985). These thoughts bring with them significant distress, which results in the individual completing some action (compulsion) to reduce this, i.e. a neutralising behaviour. This reduction in distress is reinforcing, leading to an increase in occurrence of the neutralising behaviour. Central components of this model, such as unwanted intrusive thoughts and avoidance, are shared by a number of anxiety conditions, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

PTSD consists of the co-existence of the re-experiencing of elements of previously experienced traumatic event(s), avoidance of stimuli associated with the event(s), hyperarousal and negative alterations in cognitions and mood persisting for at least one month (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The cognitive model of PTSD (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) suggests individuals process a traumatic event in a way that leads to a sense of current threat. This arises due to negative appraisals of the trauma and/or its consequences which go beyond how the trauma might be generally appraised as horrific (e.g. the fact the trauma happened to them being significant) and due to the autobiographical memory lacking contextualisation. Instead, it is characterised by strong associative memory and perceptual (sensory) priming leading to the memory having a sense of ‘nowness’. This problem becomes enduring due to problematic behavioural and cognitive strategies (i.e. SSBs) preventing new interpretations and further memory (cognitive, sensory and affective) processing (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000).

Clinicians have long documented the overlap between OCD and PTSD. Pitman (Reference Pitman1993) presented the case of a veteran who developed OCD following traumatic experiences during his service, leading the author to coin the term post-traumatic obsessive compulsive disorder. Other case studies have since reported on similar presentations (e.g. De Moraes et al., Reference De Moraes, Torresan, Trench and Torres2008; Sasson et al., Reference Sasson, Dekel, Nacasch, Chopra, Zinger, Amital and Zohar2005). Empirical studies highlight the disorders can co-occur, with the National Comorbidity Survey Replication showing those with a current diagnosis of PTSD were 3.62 times more likely to have OCD than those without PTSD (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Campbell, Lehman, Grisham and Mancill2001; albeit with a small sample n = 13); whilst Huppert et al. (Reference Huppert, Moser, Gershuny, Riggs, Spokas, Filip and Foa2005) reviewed studies reporting rates of this co-morbidity and found rates of PTSD between 6 and 22% in those with OCD.

With reference to Rachman (Reference Rachman1991), it is clear these disorders share ‘psychological connectedness’ (p. 461) with several authors highlighting this link (Dinn et al., Reference Dinn, Harris and Raynard1999; Gershuny et al., Reference Gershuny, Baer, Jenike, Minichiello and Wilhelm2002; Huppert et al., Reference Huppert, Moser, Gershuny, Riggs, Spokas, Filip and Foa2005; Riggs, Reference Riggs2000). Examples of the logical and semantic relationship between certain traumatic experiences and subsequent OCD symptoms are evident in Pitman (Reference Pitman1993) and the case series of Sasson et al. (Reference Sasson, Dekel, Nacasch, Chopra, Zinger, Amital and Zohar2005), such as being covered by the blood and flesh of soldiers leading to excessive cleaning. Huppert et al. (Reference Huppert, Moser, Gershuny, Riggs, Spokas, Filip and Foa2005) suggest rituals and avoidance behaviours develop to avoid intrusive memories associated with trauma. Through negative reinforcement via compulsions alleviating distress, these symptoms become independently maintained (Fostick et al., Reference Fostick, Nacasch and Zohar2012). Once established, symptoms of PTSD and OCD have been shown to interact and exacerbate each other. In a case series, Gershuny et al. (Reference Gershuny, Baer, Radomsky, Wilson and Jenike2003) observed symptoms of OCD and PTSD were connected such that targeting OCD specific symptoms in treatment resulted in increases in PTSD symptoms, such as intrusive thoughts and flashbacks related to specific trauma memories.

Cognitive models of co-occurrence of these disorders (Dinn et al., Reference Dinn, Harris and Raynard1999; Riggs, Reference Riggs2000) focus on the negative cognitive effects of exposure to trauma evoking anxiety. This leads to excessive labelling of stimuli as threatening which leads to compensatory mechanisms, such as compulsions or neutralising behaviours which reduce arousal and are therefore reinforced (Eysenck and Rachman, Reference Eysenck and Rachman1965). Gershuny et al. (Reference Gershuny, Baer, Radomsky, Wilson and Jenike2003) proposed OCD symptoms, such as excessive checking or hyper-attention, facilitate avoidance of emotional discomfort generated by trauma cues, and therefore the authors’ conceptualised obsessive compulsive behaviours as serving a protective function against trauma-related memories and associated negative affect. Indeed, to paraphrase Riggs (Reference Riggs2000), it’s easier to worry about the dirt in your kitchen than the trauma of your combat experience.

Literature describing ‘mental contamination’ which can be apparent in OCD also has relevance here given that this can relate to traumatic experiences. Mental contamination is a current internal sense of dirtiness that occurs in the absence of physical contact with a contaminant (Rachman, Reference Rachman2004) and is thought to develop following previous emotional or physical violations such as degradation, betrayal or abuse. Importantly, feelings of mental contamination can be evoked by memories and images, such as traumatic memories, and therefore such symptoms could be triggered by situations associated with such memories. As with cognitive theories of PTSD and OCD which contest that a misinterpretation of meaning can result in distressing symptoms, the cognitive theory of mental contamination postulates too that this arises due to a serious misinterpretation of the personal significance of a psychological or physical violation. This distress results in vigorous and repetitive washing to get rid of associated unpleasant feelings (Radomsky et al., Reference Radomsky, Coughtry, Shafran and Rachman2017). Coughtrey et al. (Reference Coughtrey, Shafran, Lee and Rachman2013) found that 46% of individuals with OCD experienced mental contamination and that increased severity of mental contamination was associated with more severe OCD.

There is strong evidence for treatment of OCD from a cognitive behavioural framework. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) including exposure and response prevention (ERP) has been shown to be effective for the treatment of OCD and is recommended as the first line treatment by NICE (National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, 2005). CBT including ERP identifies and modifies dysfunctional appraisals of intrusions and symptom related beliefs. It also identifies avoided stimuli which evoke anxiety, and has individuals come into contact with these stimuli whilst refraining from engaging in compulsions or neutralising behaviours (ERP).

Trauma-focused therapies incorporating exposure such as CBT (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2008), eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR; Shapiro, Reference Shapiro2014) and narrative exposure therapy (NET; Lely et al., Reference Lely, Smid, Jongedijk, Knipscheer and Kleber2019; Robjant and Fazel, Reference Robjant and Fazel2010) have been demonstrated to be effective in the treatment of PTSD (Bisson et al., Reference Bisson, Roberts, Andrew, Cooper and Lewis2013) and are recommended by NICE guidelines (although EMDR is only recommended if an individual has a preference for this and the trauma was not combat-related). The approaches being trauma-focused means that they directly focus on memories, thoughts and feelings related to the traumatic event (Watkins et al., Reference Watkins, Sprang and Rothbaum2018). NET was specifically developed for individuals who have experienced multiple traumatic events. It enables individuals to develop a coherent autobiographical narrative of their most significant experiences to help contextualise events that were highly arousing so that internal reminders and trauma related triggers have less dominance of the person’s life (Neuner et al., Reference Neuner, Elbert, Schauer, Bufka, Wright and Halfond2020).

Treatment of OCD has been found to be less efficacious when there is co-morbid PTSD. Gershuny et al. (Reference Gershuny, Baer, Jenike, Minichiello and Wilhelm2002) found those with OCD alone improved with ERP while those with co-occurring PTSD did not, with decreases in symptoms of OCD during ERP leading to intensification of PTSD symptoms. Furthermore, Gershuny et al. (Reference Gershuny, Baer, Parker, Gentes, Infield and Jenike2008) observed that for those with treatment-resistant OCD, 82% had a history of trauma while 39% met criteria for PTSD, suggesting its co-occurrence contributed to treatment resistance. Gershuny et al. (Reference Gershuny, Baer, Radomsky, Wilson and Jenike2003) suggested due to their dynamic connection, targeting either disorder in isolation may impede therapy effectiveness. Clinicians have therefore advocated for treatment strategies targeting symptoms of OCD and PTSD simultaneously (Gershuny et al., Reference Gershuny, Baer, Jenike, Minichiello and Wilhelm2002), or consecutively (de Silva and Marks, Reference de Silva and Marks1999). A number of recent case studies have reported on the presentation and treatment of individuals with OCD and co-morbid PTSD. Nijdam et al. (Reference Nijdam, van der Pol, Dekens, Olff and Denys2013) reported the successful treatment of a male with PTSD and OCD with EMDR followed by ERP following sexual assault. It was documented that during treatment, remission of PTSD symptoms preceded that of OCD symptoms and the authors highlighted that applying EMDR first made it easier for the patient to reduce OCD symptoms because of decreased anxiety and trauma reminders. Stobie (Reference Stobie and Grey2009) also reported on the case of women with PTSD and OCD which occurred following a physical assault. They used trauma-focused CBT initially to treat PTSD followed by CBT for OCD. They reported that helping the patient understand the link between the context of previous trauma (i.e. the location in which it happened) and current OCD related intrusions (triggered by a similar location to where the trauma occurred) helped change the symptom’s meaning, and in combination with CBT/ERP, reduced the compulsions associated with this intrusion.

The current case study seeks to add to the literature on the treatment of those presenting with PTSD and OCD by presenting a case of a male in his late-20s with OCD and PTSD symptoms which emerged following a series of traumatic and highly aversive experiences. The case was initially conceptualised as OCD; however, PTSD symptoms related to trauma became more prominent upon certain exposures and interfered with OCD treatment. The case study is novel in that it presents the use of concurrent NET and CBT with ERP as a treatment approach for co-morbid OCD and PTSD symptoms.

Client characteristics and presenting problems

This study reports the case of Arwyn (anonymised), a Caucasian male referred to a Psychological Therapies Team who had recently stopped working and become housebound due to exacerbation of OCD symptoms. Arwyn reported he had been struggling with OCD for around 10 years. His symptoms centred on rituals to ensure cleanliness and decontamination. He reported spending 6 hours a day on rituals. He used anti-bacterial spray on his clothes, bed and furnishings, and washed excessively. He had quarantined all items he perceived were contaminated to his utility room, which he described as representing all the unpleasant things that occurred during his life. He refrained from eating in his family home due to fears of contamination. This resulted in him losing 10 kg of body weight.

History of traumatic and aversive events

Arwyn described four significant events he perceived as contributing to his eventual presentation. Arwyn did not initially disclose all these events but reported that intrusive memories of these events were triggered during the course of ERP. Initially when recalling these events, he was highly avoidant of discussing them and his recall was fragmented. The details below became clearer following the completion of NET itself. Certain events meet criteria for a traumatic event according to the DSM-V definition (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) in order to qualify for a diagnosis of PTSD (i.e. serious injury in this case). For others this may be less clear and might be more appropriately termed an aversive event (however, see Brewin et al., Reference Brewin, Lanius, Novac, Schnyder and Galea2009 and Anders et al., Reference Anders, Frazier and Frankfurt2011 for a discussion around the usefulness of Criterion A).

Arwyn was physically assaulted whilst visiting friends at a university he was planning to attend (1); this assault resulted in serious physical injury that required significant cosmetic treatment. As a result of this incident he stopped seeing this group of friends. He also decided not to go to university and instead started an apprenticeship in the local area which he saw as an opportunity to ‘toughen up’. During this he was subjected to significant verbal and physical bullying which occurred over a prolonged period of time and was perpetrated by individuals in a position of power over him (i.e. his supervisors). A number of bullying incidents resulted in Arwyn being put in a position of helplessness (2). He eventually dropped out of this apprenticeship and completed a university degree. By this time, he reported displaying symptoms of OCD such as excessive cleaning. Following his degree, he went travelling. Due to perceived differing hygiene norms in the country he visited and with OCD symptoms already present in the form of concerns about contamination with germs leading to illness or death, Arwyn was in a high state of stress throughout this time. It was in this context he believed he was cursed by a native of the country following a difficult interaction (3) and therefore engaged in neutralising rituals in line with the religions of that country to rid himself from the curse. Following his return, his OCD symptoms became more severe with large amounts of anxiety and SSBs. Arwyn experienced significant anxiety when confronted with people he perceived as originating from a country he had visited during his travels, or people from his workplace, leading him to take measures to avoid contact with them. This culminated in the final difficult event in which Arwyn became overwhelmed by anxiety in work whilst trying to avoid contact with contaminants (proximity to individuals perceived to be from the country in which he went travelling or objects that could have come into contact with such individuals) and subsequently became trapped in his utility room, unable to leave due to the fear of spreading perceived contamination (4).

Previous treatment

Arwyn received 12 private CBT sessions before entering the current service. Following these sessions, he had reduced his spraying of disinfectant and delayed washing his hands after touching doors. However, he still presented with avoidant and compulsive behaviours, such as not eating, which presented concerns about his health and therefore motivated a referral to secondary care. The exact nature of the CBT Arwyn received was unclear but his previous therapist (with Arwyn’s consent) reported he had a good understanding of the CBT model of OCD and his formulation. They also highlighted that Arwyn was extremely avoidant of difficult emotions.

Symptom measures

The Obsessive Compulsive Inventory revised (OCI-R; Foa et al., Reference Foa, Huppert, Leiberg, Langner, Kichic, Hajcak and Salkovskis2002) was used to measure OCD symptoms. It consists of 18 items assessing six symptoms of OCD (washing, checking, ordering, obsessing, hoarding and neutralising). The OCI-R has excellent internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and convergent and discriminant validity (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Huppert, Leiberg, Langner, Kichic, Hajcak and Salkovskis2002). A score of 21 or above is used as a cut-off to indicate the likely presence of OCD. The mean score on the OCI-R in a large sample of individuals with OCD is 28 (SD = 13.53), while those without a diagnosis of OCD scored 18.82 (SD = 11.10; Foa et al., Reference Foa, Huppert, Leiberg, Langner, Kichic, Hajcak and Salkovskis2002).

The Impact of Events Scale-Revised (IES-R; Weiss, Reference Weiss, Wilson and Keane2007), a 22-item self-report measure that assesses subjective distress caused by traumatic events, was used on two occasions during Arwyn’s treatment, once before starting NET and once at his final session. A score of 33 and above represents best cut-off for probable PTSD (Creamer et al., Reference Creamer, Bell and Failla2003).

Informed consent

The rationale and process for each aspect of treatment was provided to Arwyn, who consented to proceed with treatment and for his assessment and treatment to be written as a case study.

Design

Treatment initially used CBT (including ERP) for OCD (Salkovskis, Reference Salkovskis1985) without any focus on traumatic memories (Phase A) and later progressed to combine NET with CBT including ERP (Phase B). The choice to add NET to the treatment approach was a pragmatic one which was influenced by a plateau in symptom reduction and evidence of re-experiencing symptoms of PTSD (intrusive unwanted memories and arousal) upon exposure to certain OCD triggers. When questioned about these during exposure there was also a reluctance (avoidance) to discuss these events. Phase A was completed by a qualified clinical psychologist. For Phase B, NET was facilitated by the same qualified clinical psychologist, while CBT with ERP was carried out by a trainee clinical psychologist.

Treatment

Phase A

Initial formulation

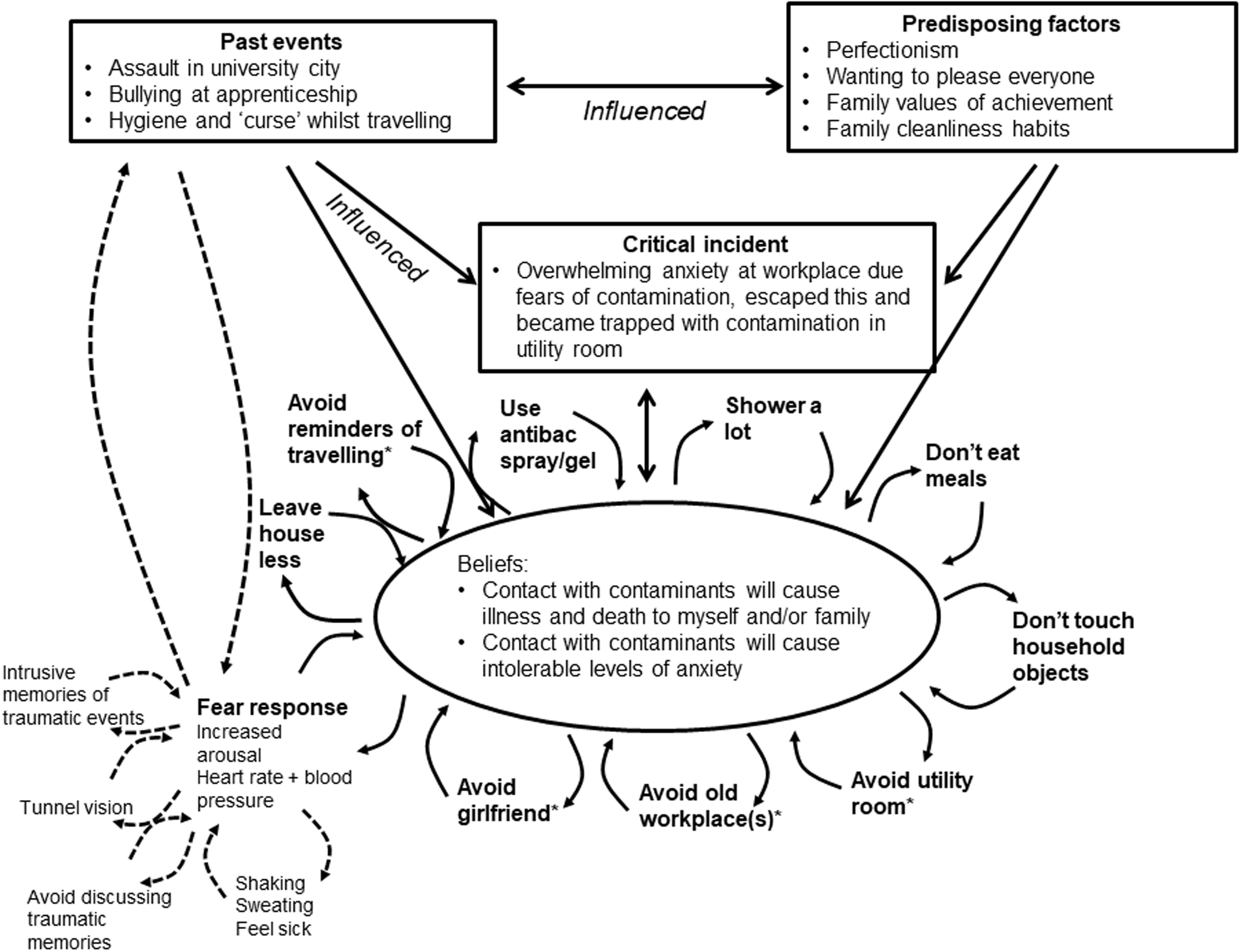

A formulation of Arwyn’s difficulties was collaboratively developed (see Fig. 1), based on a vicious flower maintenance cycle of OCD (Salkovskis, Reference Salkovskis, Tarrier, Wells and Haddock1998). A longitudinal component was added to make sense of how the OCD developed, and a critical incident to account for the why now? question. It was hypothesised a combination of pre-disposing factors, such as perfectionist tendencies (which included high standards of cleanliness) and significant life events interactively combined to lead to an overwhelming experience of anxiety during the critical incident. During this incident, Arwyn described that he became overwhelmed by anxiety at work due to beliefs that it was contaminated as a result of coming into contact with individuals who he perceived were from the country in which he was ‘cursed’ during his travels. He believed that ‘germs’ associated with people originating from the country in which he went travelling would result in illness and himself and his family dying. He perceived he lost control and ‘escaped’ to his utility room at home and became ‘trapped’ due to not wanting to spread contamination. On Fig. 1 the connection between the critical incident and maintenance factors is reciprocal due to the fact that this belief and anxiety around contamination were already present to a lesser extent and influenced his experience of this incident.

Figure 1. Arwyn’s formulation. The dashed lines were added at Phase B (revised formulation).

Arwyn developed SSBs in relation to both anticipatory and consequent anxiety (Salkovskis, Reference Salkovskis1991) in order to stop the feared outcome occurring. These avoidance and escape behaviours had the effect of preventing Arwyn discovering his beliefs were inaccurate (in line with Salkovskis, Reference Salkovskis1991), and prevented the extinction of the anxiety when exposed to the feared situations (de Silva and Rachman, Reference de Silva and Rachman1984).

Intervention directed by initial formulation

Arwyn was initially treated using CBT (including ERP) which is the first line treatment recommended for OCD by NICE guidelines (the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, 2005). It was hypothesised Arwyn exposing himself to feared situations via ERP (following an exposure hierarchy) and challenging his beliefs about the consequence of this would lead him to learn his predictions were untrue and to a reduction in anxiety.

Sessions 1 to 20 involved the collaborative development of a formulation. Arwyn was introduced to the idea of Theory A (‘contact with contaminants (‘germs’) associated with country I went travelling in will lead to illness and possible death as well as intolerable levels of anxiety causing me to lose control’) and Theory B (‘I am worried that contact with contaminants will lead to illness and possible death, anxiety is normal and will come down on its own accord’) (Challacombe et al., Reference Challacombe, Oldfield and Salkovskis2011) and evidence for these were discussed using cognitive restructuring. Arwyn completed homework tasks of exposure work to explore which theory fitted best with his experience. While ERP was conducted on two occasions with the psychologist, these were on items lower down Arwyn’s hierarchy. Most of the exposure homework was done by Arwyn alone or with help of a support worker or family members. The ERP tasks included not using his anti-bacterial spray and eating food prepared in the kitchen adjacent to the utility room.

Arwyn made progress on increasing his exposure to things lower down the hierarchy and reduced his ritualistic behaviour significantly. However, by session 20 Arwyn’s OCI-R scores had plateaued, remaining within the clinical range and both he and his family were frustrated at his rate of progress. Arwyn reported that exposure to items more directly associated with traumatic events (e.g. items or people associated with travelling, his old workplace or local areas where he was placed for his apprenticeship) he had experienced evoked intrusive memories and high levels of arousal he was unable to tolerate, and therefore would quickly discontinue the exposure. When initially questioned about these events Arwyn was visibly distressed and reluctant to discuss them and reported that he had never spoken to anyone about them before. The account of what he was able to initially share about his memory was also very fragmented.

Phase B

Revised formulation

Arwyn’s formulation was revised to highlight how intrusive memories and thoughts with negative interpretation about traumatic events brought about a sense of current threat and high levels of arousal. This further added to Arwyn’s belief he would experience intolerable anxiety. The dashed arrows in Fig. 1 represent aspects added to the revised formulation, whilst asterisks represent aspects directly associated with traumatic events Arwyn experienced. Arwyn reported voluntary suppression of the memories related to his past experiences and was not prepared to discuss these in depth at the start of therapy, a characteristic also shared with PTSD (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000). According to the cognitive model of PTSD, traumatic memories fail to become encoded in autobiographical memory and hence are experienced with a sense of current threat resulting in intrusions and physiological arousal. Due to the symptoms’ aversive nature, strategies emerge to control them (e.g. avoidance of reminders of trauma) further preventing processing and encoding into autobiographical memory (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000). Arwyn’s symptoms could fit such a profile, as he experienced high levels of distress when placed in situations associated with trauma (i.e. sense of current threat) and developed strategies to control these symptoms such as avoiding his workplace and items and memories associated with travelling. Whilst these avoidance symptoms were related to his OCD, Arwyn also reported avoidance symptoms that were pre-morbid to his OCD in that he decided not to go university (where he was assaulted) and isolated himself from his friends as a result of them reminding him of the first traumatic event (assault). Due to avoidance, Arwyn’s sense of current threat (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) when exposed to situations associated with traumatic events remained high, making it difficult to complete ERPs.

It was hypothesised applying NET to allow further processing of the traumatic memories and therefore elaboration and contextualisation (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) would lead to autobiographical storage of the memories, reducing sense of current threat and therefore arousal. This would increase the likelihood that Arwyn could tolerate exposures. NET was chosen primarily pragmatically above approaches such as TF-CBT or EMDR due to Arwyn having experienced a series of traumatic and aversive events throughout his early adulthood which meant that there were significant periods of Arwyn’s history that he found difficult to talk about. His traumatic experiences also shared some relationship with one another, such that his experience of a serious assault led to a decision not to go to university and to start an apprenticeship. It was during this subsequent apprenticeship he experienced prolonged and significant physical and psychological bullying by individuals in a higher position of power than himself (supervisors). NET assists an individual to realign their traumatic experiences within the larger context of their life and their place in the world (Schauer et al., Reference Schauer, Schauer, Neuner and Elbert2011) and is specifically designed for individuals who have experienced multiple traumatic events (Robjant and Fazel, Reference Robjant and Fazel2010) and therefore this was seen as a potential helpful approach for Arwyn. NET involves constructing a chronological account of someone’s traumatic experiences allowing conversion of the disjointed recollection of traumatic experiences to a coherent narrative, providing contextualisation (Schauer et al., Reference Schauer, Schauer, Neuner and Elbert2011). The aim of NET was to reduce Arwyn’s current sense of threat and arousal levels experienced when exposed to avoided situations to help tolerate ERPs. The aim of CBT with ERP was to further challenge his beliefs and allow further anxiety response extinction (Rachman et al., Reference Rachman, Rachman and Hodgson1980) and therefore reduce compulsive behaviour.

NET for trauma memories

Sessions 22, 25, 27, 28 and 31 used NET to allow increased processing of Arwyn’s trauma memories of the assault at a university open day, his experience of bullying at his apprenticeship, his experience travelling, and his perception he was overwhelmed by anxiety whilst in work. Arwyn described his experiences to the clinical psychologist who wrote them out as a script. The psychologist asked questions of clarification around particular hotspots including around cognitions and affect that was experienced at the time with the aim of trying to re-connect ‘hot’ (cognitive, emotional and physiological representations) and ‘cold’ (context) memories (Neuner et al., Reference Neuner, Elbert, Schauer, Bufka, Wright and Halfond2020). The writing of the script slowed down the pace to help processing of the sensory and emotional aspects of the memories. Arwyn was set between-session homework of reading through the script.

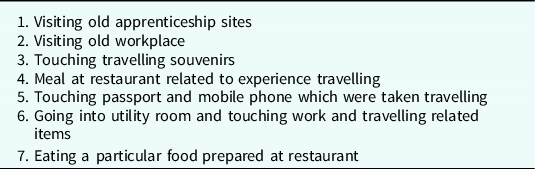

CBT with ERP

Sessions 24, 26, 29, 30 and 32 used CBT with ERP on items of his hierarchy which shared a relationship with Arwyn’s traumatic history (see Table 1). It was hypothesised that Arwyn exposing himself to avoided stimuli without engaging in neutralising behaviours would lead to a reduction in his obsessive beliefs, anxiety levels and compulsive behaviours when re-exposed to the same stimuli. During the first session, time was allocated to discuss the rationale for exposure with reference to his formulation (psychoeducation) and to update his exposure hierarchy (it should be emphasised all items were perceived as high up the hierarchy relative to previous ERPs he successfully managed during his previous 20 CBT sessions). The final hierarchy is depicted in Table 1.

Table 1. Arwyn’s exposure hierarchy

An example session of exposure to the utility room is given below which was conducted according to the protocol outlined in Salkovskis (Reference Salkovskis2007). Each ERP session followed a similar structure and due to the prolonged and field-based nature lasted 3 hours on average. An exposure practice form was used to identify Arwyn’s predictions while also providing the opportunity to track his subjective units of distress (SUDs). Outlining predictions was important to address the cognitive aspect of OCD (e.g. Meyer, Reference Meyer1966). Arwyn predicted he would become so anxious he would lose control (100% prediction). Prior to entering the utility room Arwyn was reminded to refrain from engaging in SSBs and the importance of not neutralising the exposure once he left the room was highlighted, as cognitively, going into a feared situation with the intention of undoing it can be considered as an avoidance strategy (Salkovskis, Reference Salkovskis1985). While exposure began with the trainee psychologist suggesting items to be touched, a shift was made to Arwyn independently selecting the items of exposure. Arwyn touched various items associated with his place of work and apprenticeship while his attempts to prevent spreading of the perceived contamination (known as ‘tracking’) was also brought to his attention. It was important to ensure Arwyn was fully engaged with the stimuli (he had a tendency to use conversation as a distraction method), as Borkovec and Boulougouris (Reference Borkovec and Boulougouris1982) suggest active engagement with the stimuli is crucial for extinction. Discussion followed the conclusion of the exposure in order to consolidate Arwyn’s belief the prediction will not come true on subsequent occasions (Salkovskis, Reference Salkovskis2007). Arwyn stated he learnt his anxiety reduced and he did not lose control. He re-rated the belief that he’d lose control if exposed to the same situation again at 20%. Arwyn’s SUDs also reduced from 95 to 40. A contract was collaboratively created listing the compulsions Arwyn would refrain from and the next natural time he would wash. Arwyn’s homework was to expose himself to the utility room every morning for half an hour without engaging in compulsions afterwards.

By the end of Phase B Arwyn had completed all exposures listed in his hierarchy.

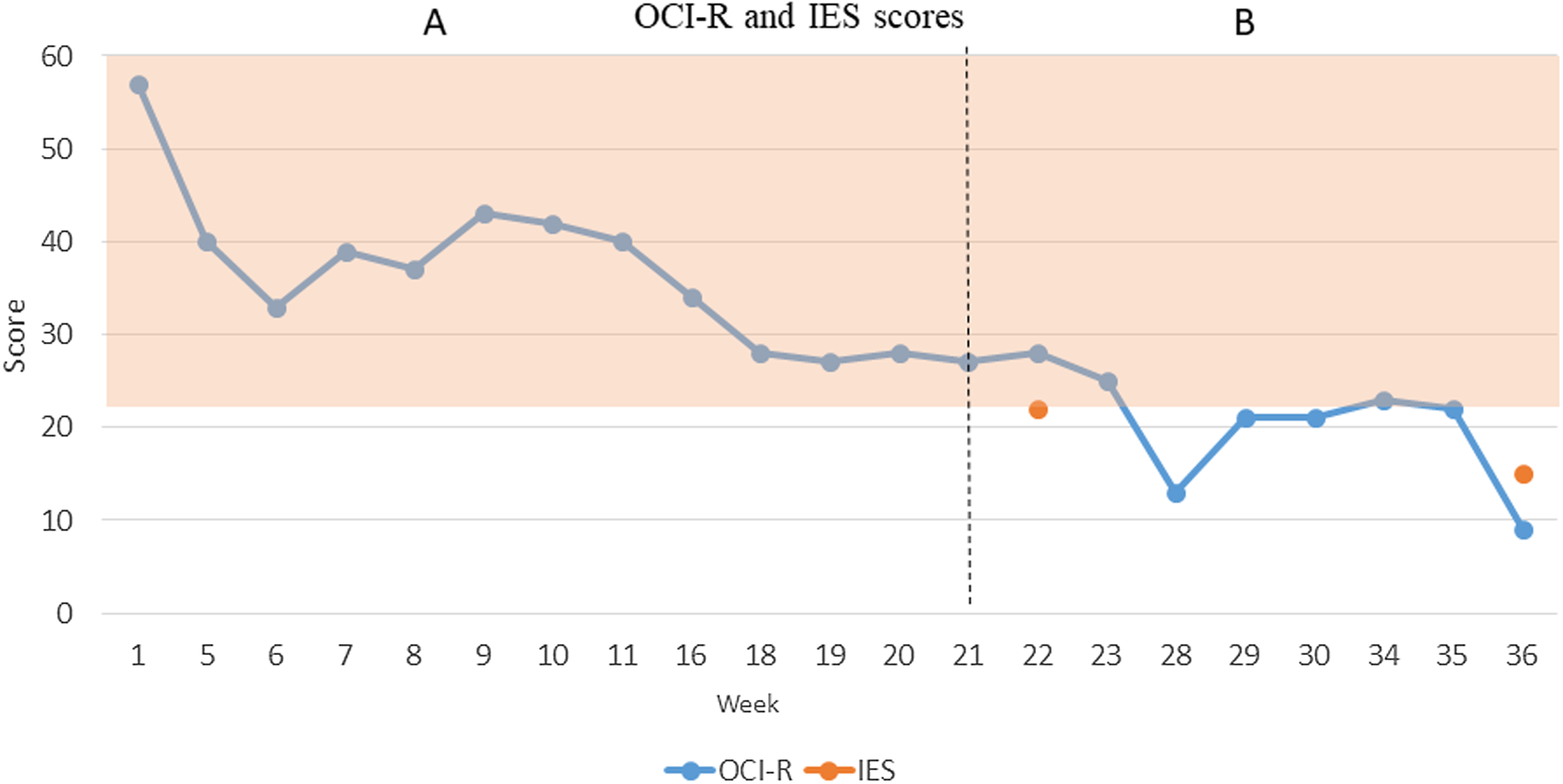

Outcome

On his entry to the service, Arwyn’s OCI-R score was 57, 2.14 SDs above the average of an OCD sample (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Huppert, Leiberg, Langner, Kichic, Hajcak and Salkovskis2002). As shown in Fig. 2, following CBT (including ERP) treatment for OCD (Phase A), Arwyn’s symptoms reduced to 28 indicating reliable improvement (Abramowitz et al., Reference Abramowitz, Tolin and Diefenbach2005) but was still above clinical cut-off. The addition of concurrent NET and CBT with ERP to the items at the top of Arwyn’s hierarchy (Phase B) led to a further reduction in OCI-R score to 9 (further reliable improvement) and well below the clinical cut-off and therefore indicating reliable recovery (Clark and Oates, Reference Clark and Oates2014). Arwyn first completed the IES-R prior to beginning Phase B, scoring 24 specifically related to his experiences in his last job (this was chosen as this was the memory he reported as currently the most traumatic). This score represents ‘clinical concern’ (Asukai et al., Reference Asukai, Kato, Kawamura and Nishizono-Maher2002) but is below the clinical cut-off of 33. By the end of Phase B Arwyn’s IES-R score reduced to 15, indicating reliable improvement (Clark and Oates, Reference Clark and Oates2014).

Figure 2. Arwyn’s OCI-R and IES scores.

From a qualitative perspective, Arwyn’s functioning significantly improved by the end of therapy in that he was actively communicating with his workplace with a view to start work again, had holidayed with friends from work and had moved in with his girlfriend (something he had previously avoided due to fears of contamination). Arwyn had also managed to return to a healthy weight and was actively discussing his memories with others.

Discussion

We presented the use of CBT including ERP (Phase A) followed by concurrent NET and CBT with ERP (Phase B) to treat an individual with OCD whose PTSD symptoms were interfering with first line OCD treatment.

Despite Arwyn’s 12 sessions of private CBT, his OCI-R remained within the clinical range and his compulsive behaviours were presenting a risk to his health. Phase A of CBT with ERP led to reliable improvement in Arwyn’s OCD symptoms and in particular in relation to SSBs and compulsions related to items lower down his exposure hierarchy. Despite this, his reduction in symptoms plateaued and remained within the clinical range and frustration emerged in response to a lack of progress on exposures higher up the hierarchy. Exposure to items at the top of his hierarchy resulted in involuntary intrusive memories and significant levels of distress which prevented Arwyn from engaging in ERP. While Arwyn’s scores on the IES-R did not meet the threshold indicating clinically significant PTSD symptoms, Arwyn presented with high levels of distress upon being asked about these memories, he was evidencing avoidance symptoms in the form of an unwillingness to discuss the memories, and reported historical avoidance symptoms that were pre-morbid to his OCD. When he did begin to try to share his memories of these events with the therapist his recall was very fragmented. Together, this suggested processing of these memories could be important to further progress. When NET and CBT with ERP were applied concurrently, Arwyn was able to complete exposure tasks to stimuli that shared a strong association with his trauma memories, something he was not able to do during Phase A. By the end of treatment Arwyn had achieved reliable recovery from OCD and reliable improvement in PTSD symptoms and he had returned to a level of functioning he was content with.

Clinical implications

Our approach involved adding NET to CBT with ERP which was already underway. This is as opposed to using a staggered approach of switching to NET alone first, before continuing with CBT with ERP. Therefore, it is difficult to separate out the individual contribution of NET and CBT with ERP to the reduction in symptoms evidenced above. However, we did show that following their concurrent application there was a reduction in Arwyn’s OCD symptoms to non-clinical levels. If OCD thoughts and behaviours developed to help avoid the distress related to trauma related memories (Gershuny et al., Reference Gershuny, Baer, Radomsky, Wilson and Jenike2003; Huppert et al., Reference Huppert, Moser, Gershuny, Riggs, Spokas, Filip and Foa2005), it is possible increased processing of the memories provided opportunity for Arwyn to consider their contribution to his life choices and this may have helped integrate it with his life story and lowered the level of arousal experienced when confronted with triggers to the memories. This may have contributed to his ability to participate in exposures to items at the top of his hierarchy whilst dropping previous compulsive behaviours. At the earlier stages of therapy, even following ERP on items lower down his hierarchy, Arwyn was not willing to do this. This appears consistent with research suggesting the experience of trauma makes the anxiety more severe and therefore more difficult to engage with ERP (Riggs, Reference Riggs2000).

As described earlier, the co-occurrence of PTSD in those with OCD has been thought to contribute to its treatment resistance (Gershuny et al., Reference Gershuny, Baer, Jenike, Minichiello and Wilhelm2002). In the current case study we provide some evidence the combination of NET for trauma memories and CBT with ERP for OCD could be beneficial for the treatment of OCD with origins in traumatic events and first line treatment for OCD has not resulted in reliable improvement of symptoms.

Alternative approaches

In the current study, the choice to use NET was partly pragmatic due to Arwyn experiencing multiple connected traumatic or aversive experiences over a number of years. In light of the aim of NET in the current study, i.e. to reduce sense of current threat and arousal in response to trauma-related triggers, it is possible (and likely, given the evidence base) that other trauma-focused therapies such as TF-CBT, EMDR or cognitive processing therapy could have resulted in a similar outcome to NET (particularly in cases where there is a single trauma). Indeed, other case studies have described combining TF-CBT (Stobie, Reference Stobie and Grey2009) or EMDR (Nijdam et al., Reference Nijdam, van der Pol, Dekens, Olff and Denys2013) with CBT and ERP (albeit consecutively rather than concurrently) as an approach to treating individuals with co-morbid OCD and PTSD.

It is also important to highlight that other studies have highlighted the role of ‘aversive’ memories in the development and maintenance of OCD (e.g. Coughtrey et al., Reference Coughtrey, Shafran, Lee and Rachman2013) and have used imagery re-scripting as a treatment approach in such cases. Imagery re-scripting can be used to relive and restructure the meaning or course of events in a memory to something less catastrophic and this is thought to be particularly helpful when the predominant emotions associated with a memory relate to anger, shame or guilt as opposed to fear (Arntz, Reference Arntz2012). In a case series, Veale et al. (Reference Veale, Page, Woodward and Salkovskis2015) applied imagery re-scripting to a series of 12 cases with OCD with intrusive distressing images emotionally linked to a past aversive memory and found reliable improvement in nine out of 12 cases and clinically significant change in seven out of 12. Given the above, it is possible that using imagery re-scripting rather than NET in the current case could also have led to similar outcomes.

A further alternative treatment approach could have been to use a trauma-focused treatment alone, without concurrent CBT with ERP. If Arwyn’s OCD developed to avoid memories and associated distress, reducing the levels of arousal associated with exposure to certain triggers with NET alone could have been sufficient to absolve the need to engage in compulsive behaviours. Therefore it is possible that Arwyn could have reduced compulsive behaviours spontaneously without the need for further CBT with ERP. Future studies could explore this hypothesis by delivering a phase of NET (or other trauma-focused therapy) first and measuring symptom change, before moving onto a phase of CBT with ERP.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations to this case study which makes it difficult to draw strong conclusions about the combined use of NET and CBT with ERP for OCD and PTSD symptom reduction.

First, throughout Arwyn’s treatment there was a consistent downward trend in symptoms, despite a plateau around 20 weeks. Arwyn’s OCI-R scores may have continued to reduce had Phase A continued, given enough time. Second whilst Arwyn had the support of his family members or support workers during exposures during Phase A, it is possible the change in Phase B to prolonged (3 hour) in vivo ERP which was facilitated by the clinician led to Arwyn’s increased willingness to complete the ERPs and therefore the improvements observed. It is possible that the quality of ERP was higher when clinician-supported rather than self-directed (although an RCT has found no differences in outcome between self-directed and therapist-directed ERP; van Oppen et al., Reference van Oppen, van Balkom, Smit, Schuurmans, van Dyck and Emmelkamp2010), whilst the presence of the therapist may have improved trust in the approach and helped with emotional containment. In order to obtain a more accurate picture of the contribution of NET to Arwyn’s willingness to complete ERPs during Phase B, it may have been preferable to keep the support he had in completing the exposures the same as Phase A (i.e. self-directed with the support of family). Third, long-term follow-up measures were not collected due to this not being routine practice in the service, therefore it is not clear if the reliable recovery was maintained. It is possible the pattern of symptom reduction illustrated in Fig. 2 was not a stable pattern. Nonetheless, it is important to emphasise the positive functional changes Arwyn had made to his life in this time. Lastly, this study described the single case of an individual whose sub-threshold PTSD symptoms were thought to be impacting on OCD treatment and therefore the approach described may not be relevant to other cases of co-morbid OCD and PTSD. Since the completion of this case study, Pinicotti et al. (Reference Pinciotti, Fontenelle, Van Kirk and Riemannin press) have reviewed the co-morbid presentation of OCD and PTSD and have made a number of recommendations for its conceptualisation, assessment and treatment. The interested reader is directed to this.

Key practice points

-

(1) Clinicians treating OCD should consider how unprocessed trauma could impact on standard treatment for OCD.

-

(2) Combining NET to process trauma memories interspersed with CBT including ERP to treat OCD symptomology may be helpful in reducing symptoms of both OCD and PTSD.

-

(3) Further research in robust and controlled studies is required prior to conclusions about the effectiveness of this approach.

Data availability

All data generated as part of this study are presented in this case study manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Arwyn (pseudonym) for his consent to share his case study.

Author contributions

Jac Airdrie: Conceptualization (equal), Formal analysis (lead), Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (equal); Sinead Lambe: Conceptualization (supporting), Investigation (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Supervision (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); Kate Cooper: Conceptualization (equal), Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Supervision (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal).

Financial support

J.A., S.L. and K.C. were all employed by local NHS trusts during the completion of this case study. No additional funding was provided.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

All authors abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. Written informed consent was provided by the subject of his case study, who saw the case study in full and agreed to it going forward to publication. No ethical approval was required for the study as only routine clinical data were used. The NHS trust which Arwyn was under approved its publication conditional on Arwyn providing his written informed consent.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.