Five dancers take the sharp, pointed finger of the odissi suchi hand gesture and bring it toward their faces as if they might poke out their own eyes. They squat, pulling their hips downward and tilting the pelvis slightly forward in the chair pose of yoga. With both feet planted beneath them, they lift one leg, move it to the side away from the body, shift it back in, and immediately follow with the other foot, moving it outward and quickly returning it back. Simultaneously, they raise their elbows. Each dancer gradually falls to the floor leaving the one white female, Sarah Beck‐Esmay, standing. Originally part of the group, she now stands alone as the other dancers crawl offstage. Beck‐Esmay presses her hand forcefully to the side of her face so that her chin moves sharply to the side. Then, she moves to the center and kneels down on the floor.

Figure 1. Ananya Chatterjea embodying the spirit of Dakini in Shaatranga: Women Weaving Worlds. The O’Shaughnessy at St. Catherine University, Saint Paul, MN, 2018. (Photo by Randy Karels; courtesy of Ananya Dance Theatre)

This moment of Ananya Chatterjea’s choreography is a transition between two pieces: “Nightmare” and “Beauty.” Chatterjea places the ensemble of dancers in a challenging situation — moving aggressively and to the point of exhaustion — in her choreographed commentary on the negative impacts of conventional ideas about beauty. A white female body becomes subject to the pitfalls of “classic” notions of an ideal body, but Chatterjea’s positioning of Beck‐Esmay is strategic: her body is continuously in conversation with the black and brown women and femmes of the ensemble.

Immediately following Beck‐Esmay’s performance, a trio of dancers emerges. Lela Pierce, Renée Copeland, and Ananya Chatterjea use the odissi hand gesture shukachanchu, with the middle finger and thumb pressed together and the other digits remaining open and rounded. Placing the mudra firmly under their cheek and tilting their chins upward and toward their fingers, they showcase the upper portion of their faces. This trio comprises one mixed‐race dancer, Pierce; one brown woman, Chatterjea; and one white woman, Copeland. Chatterjea put her own body into this power structure as the Indian dance ideal of a heterosexual, female person.Footnote 1 Next, Chinese American Hui Niu Wilcox dances alone, running in a wide circle onstage while slashing red lipstick across her lips. This example from Ananya Chatterjea’s choreography for the 2012 performance Moreechika highlights the diverse bodies in this company and stages the company’s commitment to addressing the intersection of race and gender in global issues that impact communities.

Chatterjea founded Ananya Dance Theatre (ADT) in 2004 in Minneapolis, Minnesota, to explore social justice themes through the global stories of black and brown women and femmes. The company’s first two works, Bandh: Meditation on Dream (2005) and Duurbaar: Journeys into Horizon (2006), told stories of women’s aspirations to claim a space of healing and empowerment, as well as their struggles to access water in indigenous communities and communities of color. Through ADT, Chatterjea developed the company’s proprietary dance technique, YorchháTM, an intersection of odissi dance and chhau martial arts of eastern India and the vinyasa style of yoga. In 2006, I joined the group as an apprentice, and eventually performed in Pipaashaa: Extreme Thirst in 2007, Ashesh Barsha: Unending Monsoon in 2009, and I have since danced in seven other company works. Currently, ADT is located in Saint Paul, Minnesota, at the Shawngrám Institute for Performance and Social Justice.

I mobilize “a radical practice of inclusion” as a framework for analyzing the careful work of choreographing bodies in Indian dance to fundamentally reshape social categories as a social justice project. I use the term “radical” in particular to indicate my focus on different experiences of race, gender, and sexuality that are not necessarily limited to a biologically female person‐of‐color body. In ADT’s dances, white women, queer black and brown male bodies, and mixed‐race persons move in relationship to stories of black and brown women and femmes. This radical practice spotlights the diversity of these bodies, with a clear understanding of how each person exists on an axis of power and might be socially perceived in relation to complex Asian and African intersections, stories of sexual violence, and the Black Lives Matter movement.

Attention to race and gender lays the groundwork for grappling with gender‐based violence, for highlighting the mission of the Black Lives Matter movement, and for exploring the human impact of capitalism through legacies of systemic racism and colonialism in African and Asian contexts. This framework can help define the terms “diversity,” or the visual appearance of different cultural groups in a space; “inclusion,” or the feelings of belonging those diverse ethnic persons experience; and “equity,” or the shifting of power dynamics so that different racial communities have the resources necessary to transform legacies of inequality. A radical practice of inclusion in dance will show how an inclusive practice creates a space for diverse bodies to be part of the work of ensuring equity and justice.

My choreographic analysis identifies particular gestures, movement principles, and foundational techniques of the three genres that make up Yorchhá: odissi dance, vinyasa yoga, and chhau martial arts.Footnote 2 When training in vinyasa, we move a step away from odissi and the history of how the dance has been made “classical” and toward yoga to master meditative control of the breath while remaining fully extended in a pose.Footnote 3 Although we train in all three forms, I focus on Yorchhá’s grounding in the physical postures, gestural vocabulary, rhythmic patterns, and bodily shapes of odissi, as well as the alignment and flow of vinyasa poses — and how we integrate these forms into the choreography.

Odissi body positions require the dancers’ precise execution. In chauk, for example, dancers plant their feet shoulder‐distance apart, bend their knees, and raise their arms forward to shoulder height to create a square shape. Another odissi stance, tribhangi, is formed by three bends of the body: bending one leg to sit low, lifting the other leg straight out at a low angle, while moving the upper torso to the side, and oppositionally extending the chin out. Hand gestures, or mudras, such as the pointed finger of suchi, the flowered shape of alapadma, and the touching thumb and index finger of hamsasya, are also used in ADT’s Yorchhá technique. Additionally, the poses of vinyasa contribute to the movement, poses that I describe based on the outline of the skeletal structure. Yorchhá is not designed to present odissi repertoire, yet principles such as rasa, or the embodiment of tastes and sensations in Indian dance, help to explain how dancers shape a particular emotion through the movement. The choreography is grounded in these physical values of Indian movement practices to place diverse bodies together in the context of social — rather than purely personal — perceptions of bodies in the world.

Chatterjea builds her work around issues of gender and racial politics and makes choreographic choices to focus on systemic violence against girls and women. The compositional strategies of her solo and ensemble movement, as well as the community engagement efforts of ADT, propel the work toward cross‐cultural intersections, emphasizing the group’s affinity with the Black Lives Matter movement. The company mobilizes its racially mixed and white female dancers to prioritize different experiences of capitalism in Asian and African worlds, especially in its Work Women Do dance series.

In my descriptions of the ensemble’s movement and community work I use the autoethnographic method of writing, frequently using “we” and “our.” At other times, I am an observer, witnessing the dance as a spectator alongside other audience members.Footnote 4 Here, my own bodily relation to power is deeply implicated and inseparable from the practice itself, making my observations continuously steeped in the subjectivity of my role as a dancer in the company.

Work Women Do

Framing Gender and Race in an Indian Dance Series

A major part of what led Ananya Chatterjea to make dance about gender and race was her move in 1998 to join the faculty of the University of Minnesota dance department. She had lived on the East Coast, earning her PhD in dance studies at Temple University in Philadelphia. Arriving at the Minneapolis‐Saint Paul airport with her daughter Srija, Chatterjea did not see a single person who might share her cultural heritage.Footnote 5 Feeling alienated as a South Asian woman in a predominantly white region motivated her, and in 2004 an ethnically diverse group of black and brown women and femmes showed up to audition for what became the Ananya Dance Theatre. The first company members danced in Bandh: Meditation on Dream (2005) and Duurbaar: Journeys into Horizon (2006). Four of the company’s founding artists — Omise’eke Natasha Tinsley, Hui Niu Wilcox, Shannon Gibney, and Chatterjea — describe this early period as a time of exploring their “politically indispensable” differences through dance (Tinsley et al. Reference Tinsley, Chatterjea, Wilcox, Gibney, Swarr and Nagar2010:162).

With Kshoy!/Decay! (2010), Chatterjea began to include white female artists Sarah Beck‐Esmay and Renée Copeland. And by 2012, the company had its first assigned‐male‐at‐birth artist, Orlando Hunter. Even so, Chatterjea asserted, “Ananya Dance Theatre is a company of women of color. It will always be women of color. It’s not so much about ‘head count’ as core strength” (Chatterjea Reference Chatterjea2012a).Footnote 6 The participation of white women and male bodies did not shift ADT’s storytelling away from issues faced by women and black and brown communities. Chatterjea, Wilcox, Gibney, and Tinsley wrote about this in their essay, “So Much to Remind Us We Are Dancing on Other People’s Blood,” in which they acknowledged the fluid, malleable realities of gender (Tinsley et al. Reference Tinsley, Chatterjea, Wilcox, Gibney, Swarr and Nagar2010:163).

To refine this commitment to the intersectional experiences of race and gender, ADT produced a new evening‐length dance each year, starting with the Environmental Justice trilogy: Pipaashaa: Extreme Thirst (2007), Daak: Call to Action (2008), and Ashesh Barsha: Unending Monsoon (2009) respectively exploring pollution, people’s displacement from land, and industrial waste. The trilogy went deeply into complex structural oppression in many areas of life, especially where these related to the lives of women. And from 2010 to 2013, Chatterjea developed the Systemic Violence Against Women quartet, exploring women’s experiences with and responses to systemic violence in Kshoy!/Decay! (2010), Tushaanal: Fires of Dry Grass (2011), Moreechika: Season of Mirage (2012), and Mohona: Estuaries of Desire (2013) (AnanyaDanceTheatre.org 2013). Chatterjea explained:

My earliest work as a choreographer had been with women and violence. I had worked with a South Asian women’s shelter in New Jersey. Always I had been affected by violence, so I had to really understand that domestic violence is easy to say when “one man beats up one woman.” But actually, we exist in the context of state‐sponsored patriarchy. (Chatterjea Reference Chatterjea2012a)

The premise of the dances in this series was that the daily lives of black and brown women and femmes were continually and viciously disrupted by violence that was more than just personal; it was systemic. This project continued from 2014 to 2018 in five evening‐length dances exploring the essential labor of black and brown women and femmes in the Work Women Do series.

Chatterjea’s solo work in one dance of the Work Women Do series unearths the complex politics performed by the dancers, as well as their Yorchhá training. Chatterjea’s solo, “Anthem,” is part of Shaatranga: Women Weaving Worlds, the fifth piece of the quintet. It is a dedication to Asifa Bano, an eight‐year‐old girl who once lived in a nomadic Muslim community (Shaatranga 2018).Footnote 7 Asifa was gang‐raped, beaten, and choked to death with her own scarf at a Hindu shrine in the district of Kathua (Masih and Slater Reference Masih and Slater2019). In her writing, Chatterjea has described how choreography can stage ideas about patriarchal structures and the actions — or inactions — of the state (Reference Chatterjea2004b:104). She has sought to confront and work outside the cultural politics that construct rigid notions of religious fundamentalism (110) and, especially in her solo, how problematic ideologies tied to religion harm young girls.

Through a series of yoga poses, Chatterjea’s “Anthem” offers an interpretation of the memory of Asifa. These yoga poses highlight the complexity of a life ended by sexual violence rather than put on display a visual image of a person being raped. From a face‐down prone position, Chatterjea pushes up her pelvis and torso in the yogic back bend, Upward Facing Dog. She turns to her side, lifted on one arm, and comes up onto yoga’s Side Plank with the top leg lifted off the bottom foot, forming a V‐shape with her legs, her free arm lifted straight up and her mouth wide open. She rotates and thrusts the lifted leg forward into a lunge pose, while reaching one arm forward to create a full diagonal shape with the leg and arm. She comes up slowly, legs together, and lifts one arm forward and one arm back, forming the alapadma mudra with the back hand by bowling the palm and spreading the fingers wide open. She throws both arms forward and down to bend into the Forward Fold of yoga. Lifting her arms to transition into another yoga balance, she places her hands behind her tailbone and squats down fully, then lengthens her legs out in a balance as she holds up her body with just her hands.

Chatterjea mobilized the yogic underpinnings of Yorchhá to illustrate the impact of patriarchal ideologies on brown women and girls. Dance scholarship has taken an interest in yoga and its possibilities of resistance; Sheena Sood recalls the 2002 Gujarat riots during which an estimated 2,000 Muslims were killed and accounts for the role Chief Minister Narendra Modi, now India’s prime minister, played in instigating this violence (Reference Sood2018:15). Through dance, South Asian women like Chatterjea and Sood use their bodies to challenge the ideologies that have subjected young Muslims to oppression and violence.

Another sequence illustrates how Chatterjea works her body against the effects and presence of violence in her space. The sharp charge of her arm movements and the tension in her hand gestures express vigilance against aggression. With her arms open wide to her sides, she gazes at the one hand in the gesture of kapittha: she presses the thumb inside of the index finger while folding the other fingers toward the palm. She throws her arms open wide and shifts the gaze toward one arm, and then looks forward again while pressing her body further upstage and to the confines of the corner, as she alternately opens and closes her arms. After finding her balance on one leg as she holds the shin of the lifted leg briefly in one hand, she makes a series of arm movements to trace a figure eight. Making full turns, she balances on one leg with arms out fully to the side and chest forward, bending the knee of the lifted leg so the shin is directed perpendicular to the floor. Her arms swing sharply up and down. She then shoots the lifted leg out with the foot fully flexed up.

In another segment, Chatterjea’s facial gesture indicates resistance. First, she lays on her stomach with her arms in front of her, lifts the upper spine while pressing down on the insides of the wrists and lifting her fingers off the floor. She then leans her head back and opens her mouth fully. She lifts her hands off the floor to swiftly push the crown of her head into her hands. The movement is an expression of ADT’s emotional aesthetics, what Chatterjea describes as Dakini, or the “wrathful female spirit, dancing with frenzy and ferocity.” This “energy is expelled from the performers through large gestures, big spinal movements, tremors and shaking torsos, references to oozing bodily fluids, wide open mouths, tangled hair, and deconstructed costumes” (Chatterjea et al. Reference Chatterjea, Steinwald, Peterson and Kundan2017). Central to understanding this energetic force is the Hindu deity Kali who represents “that cosmic multimillion‐year period when the world falls into decline and evil rules the day” (McNeal Reference McNeal, McDermott and Kripal2003:223). The power of Mother Kali “liberates us from suffering in this turbulent age,” explains Keith E. McNeal, and Kali’s mythic iconography as a warrior is embodied by Chatterjea. The energetic focus of the dancer remains separate from the “wrathful” emotions of Kali, who performs a “dance of divinely inspired destruction” (243). The “Anthem” solo employs the Yorchhá practice to engage the female‐bodied energetic force of resilience while honoring the lives lost to gender‐based violence.

The dancer’s intent in all ADT work is to communicate feelings viscerally so that audiences can experience these sensations. In this context, the work reflects the “rasaesthetics,” a term coined by Richard Schechner to describe “an experience that takes place inside the body specifically engaging the enteric nervous system” (Reference Schechner2001:35). The artist uses all senses to embody feelings so that the audience can experience and respond to the emotions conveyed through the performance.

Indian Dance and Community Engagement with the Black Lives Matter Movement

Chatterjea has made a concerted effort with ADT to engage with the community, centering on the experiences of people of color locally and in a broader social context. This focus on systemic racism was prompted by the tragic deaths of black men at the hands of police in the Twin Cities. The 2016 piece, Horidraa: Golden Healing, part of the Work Women Do series, was made in the wake of the killing of two unarmed black men in the Minneapolis‐Saint Paul area, Jamar Clark and Philando Castile. Activists and community organizers had converged at the fourth precinct of the Minneapolis police department in 2014 after police killed 24‐year‐old Clark in north Minneapolis.Footnote 8 This Black Lives Matter protest became part of 18 days of demonstrations to call for an in‐depth federal investigation of the events that led to Clark’s death (Sepic Reference Sepic2016). Then, on 6 July 2016, 32‐year‐old Philando Castile, a cafeteria supervisor, was killed by police in the Falcon Heights neighborhood of Saint Paul. Castile was shot several times after informing the officer he was licensed to carry (Yuen and Feshir Reference Yuen and Feshir2016). His girlfriend live‐streamed the tragedy on Facebook, as her daughter sat in the backseat of the vehicle.

As a company, we facilitated dialogues to connect these Minneapolis‐based struggles to black women’s experiences of systemic racism and violence in other states. Chatterjea specifically reached out to black women leaders in our community, bringing into the conversation musician Stephanie Watts, filmmaker and activist Julia Nekesa, musician Andrea “Queen Drea” Reynolds, and Somali community organizer Nimo Hussein Farah. At the center of our discussions from fall 2015 through summer 2016 was Sandra Bland, who had died in police custody in Waller County, Texas, after being pulled over for a routine traffic stop in 2015. The conditions of Bland’s death spurred additional dialogue on how black women endured police violence (see Lartey Reference Lartey2018). In hosting these small community dialogues within ADT, the company sought to bring Black Lives Matter movements to the center of its work.Footnote 9

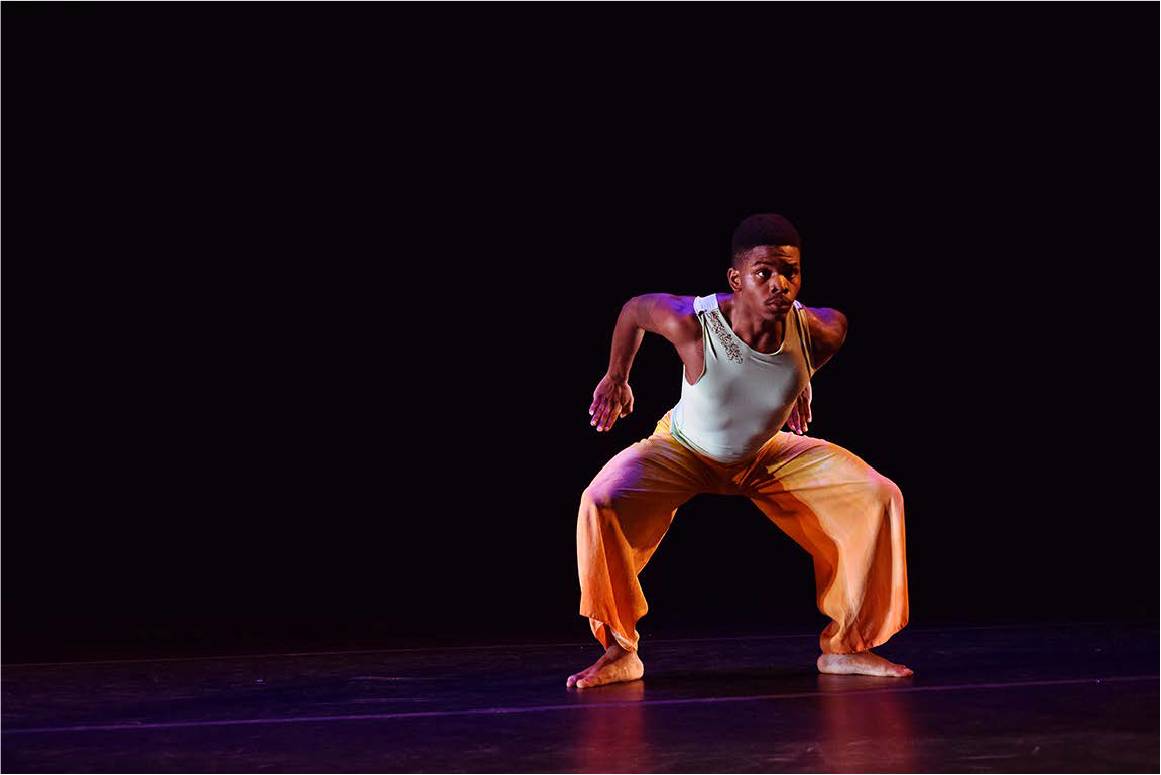

Figure 2. Jay Galtney landing in chauk position in Horidraa: Golden Healing. The O’Shaughnessy at St. Catherine University, Saint Paul, MN, 2016. (Photo by V. Paul Virtucio; courtesy of Ananya Dance Theatre)

As part of our engagement initiatives we also invited supporters to participate in making materials for our set, and prepared community members to take part onstage. For Shaatranga: Women Weaving Worlds, our 2018 community workshops guided attendees in dyeing textiles with indigo, which would later be used on the set.Footnote 10 Each person used a different technique, some shaping and binding the fabric with rubber bands, others folding it with a tool, such as a wooden bar, then dipping it in the dye. These workshops were co‐led by Chatterjea and Felicia Perry, an ADT artist and fashion designer.Footnote 11

Other aspects of our workshops focused more on the physical foundation of the company’s work. Under the theme Indigo Connections, ADT artists facilitated movement‐based exchanges with participants. ADT’s artistic associate Kealoha Ferreira and I co‐led a workshop at the O’Shaughnessy Theater in Saint Paul. The O’Shaughnessy is located on the campus of St. Catherine University, a women‐centered institution that promotes gender equality for young women leaders. Each year since the 2013 Mohona: Estuaries of Desire, ADT’s newest production has premiered at this site, including Shaatranga.

Guiding attendees through movement exercises, we divided them up in pairs and instructed them to take hold of one another’s hands, face each other, and make eye contact. Insisting on the gestural specificity and intention central to Yorchhá, we next had participants form a circle, and while fully present in observing one another’s movements, we carefully lifted up our forearms, pressed our fingers together tightly, and held our elbows at our sides. Grounding everyone in the practice of vinyasa flow, each lifting and lowering of the hands was accompanied by a collective inhale and exhale. To remind our participants of the centering purpose of this physical labor of breath, gaze, and touch, Ferreira read aloud from Audre Lorde’s Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (Reference Lorde1982). Lorde’s “biomythography” articulated our goal for participants who recalled their own memories and experiences, bringing us together as we shared our inseparable gendered, racial, and sexual lives. Many of the participants in the Indigo Connections workshops would have an opportunity to share an intimate experience of the Shaatranga performance: some would sit in risers at the back of the stage near the dancers instead of out in the theatre with the rest of the audience.

Significantly, as part of the community engagement that preceded our 2016 performance of Horidraa, ADT had also formed an alliance with young black women in the community, beginning with the Twin Cities Mayday Parade, in which ADT participated during the spring of 2016. In this annual gathering, ADT marches in a long line with other organizations, artists, and community members in celebration of spring and the possibilities for social change. On the first Sunday of every May, the parade brings together over 50,000 people to be “rooted in the local community and contemporary issues, concerns, and visions for a better world” as it proceeds toward the Powderhorn neighborhood of Minneapolis (Hobt.org n.d.). For the 2016 Mayday Parade, ADT included the Jumping Jets Drill Team and Drum Squad of Saint Paul, a group of young black women led by ADT artist Jay Galtney.Footnote 12

The goal of inviting the Jumping Jets to the Mayday Parade was to teach them some of our routines so they could dance with us. We also wanted to highlight their own work in solo performances. Galtney’s group came to our rehearsals and Chatterjea worked with them to mark each step and each transition between dance steps with clarity. ADT worked in partnership with the girls, sharing the ADT process while also amplifying the girls’ own voices and practices.

Sharing space with the Jumping Jets was transferred from the rehearsal room to parade day where at times the drill team took the lead and did their own routines, and at other points ADT stepped forward with our danced anthem: “Our color is our power! We dance loud and brown! Watch us transform! Feet to the ground!” (Ananya Dance Theatre Reference Theatre2015). In the midst of these exchanges, Chatterjea danced alongside Galtney, taking on the drill team’s sound and reinterpreting it through the Yorchhá aesthetic. She lowered her body, keeping her bent legs in a firm parallel. With sideward shifts of the torso, and with less precision of the lower extremities than she usually practiced, she adapted to an element of the “Africanist aesthetic” described by Brenda Dixon Gottschild as “the cool” (Reference Gottschild1996). Chatterjea placed her body directly in relation to an Africanist value system and reshaped her own dancing in this context.

Chatterjea most clearly brought together her Indian dance practice and African American experiences in the 2016 piece Horidraa: Golden Healing, in which Galtney and I both had solo pieces. To begin, 12 dancers hold up a length of orange‐and‐red fabric. Together we swirl it in large swoops across the stage by grabbing its edge while moving in a circular pattern. As I emerge from the circle, the ensemble runs off stage and I am alone. I come down to the floor in yoga’s Low Plank pose, holding my torso up from the floor with bent arms, elbows and hands on the floor, reaching my legs straight behind me and tucking my toes under to hold my body off the floor. I look up, look to one side, and then circle my head around. When my body lowers to the floor, one hand stretches to the audience and I turn to lay on my back and lift my chest, gazing at the audience in yoga’s Fish pose. My feet are flexed and one hand is at my navel. Then, I lift both legs to balance on my tailbone, forming the V‐shape of yoga’s Boat pose. Intersecting our training in odissi dance, as I come to stand I incorporate swastikapada position by jumping up onto my feet. I cross my wrists in front of my navel; my legs are also crossed at the ankle, as I balance on the balls of my feet. Then, I jump back out with bent knees in the grounded stance of chauk pose. Reverting back to a crossed pattern, I curve my spine and bring one knee behind the other to balance on one leg in meena puchhapada.

Indian dance practice is at the root of my movements as well as Galtney’s, connecting rather than conflating our differences. We observe this as Galtney enters at the end of my sequence, bursting onto the stage with one arm lifted and the other across his face. Galtney has a completely different way of moving through yoga poses. Galtney opens his arms out and falls to the floor in yoga’s High Plank to gaze out at the audience. Holding the pose, Galtney lifts one leg high then lowers the leg and crosses the foot under his body; this is repeated on the other side while shaking his head. With one hand on the floor, arm straight, Galtney balances on the side edge of one foot in yoga’s Side Plank, keeping a steady body to lift the top leg. Galtney turns back to face the floor, both hands down, lifts the tailbone up toward the ceiling to form yoga’s Downward‐Facing Dog, and then returns to Plank and brings one leg forward, knee bent, reaching his torso up and arching backward. Galtney falls forward and opens back up into a Side Plank.

Within the choreography for Horidraa gender expression is fluid as Galtney’s black male body moves through the spinal curvature, gestural vocabulary, and footwork of the traditionally female odissi dance. Galtney makes multiple circles of the arms in the clear, rounded shape of a figure eight then jumps up to land in the rectangular shape of chauk, feet set firmly apart. Galtney lifts one bended leg while balancing on the other. Turning, Galtney joins the thumb and index finger to hold the hamsasya hand gesture, a flower, near the face. Then, Galtney jumps up, lifting his body from the floor in the rectangular shape of chauk pose. Shifting to a curvilinear odissi position, Galtney bends both knees and reaches one leg slightly forward and to the side to lower in tribhangi while keeping one hand overhead and the other arm out at shoulder height. Galtney folds forward and then straightens up, connecting hands at the wrists and lengthening the fingers. With the arms reaching out, the hands circle around one another with wrists pressed together.

Moving across gender boundaries, Galtney dances between the masculine stereotype of the angular, rectangular, and speedy agility of chauk to the typically feminine curved spine, shapely hips, and soft gestures of odissi. Indian dance scholar Anurima Banerji has examined the historical practices of young Indian male dancers, gotipuas, who performed feminine characters onstage and whose “becoming feminine required a certain labour, a discipline one had to acquire” through the aesthetic frame (Reference Banerji2019:208). Also examining male bodies training in classical Indian dance, Royona Mitra discusses how choreographer Akram Khan’s training in South Asian dance was unusual given that the “classicization” of dance practice was a female project. “Classical” dance moves seamlessly between masculinity and femininity through its dramatization process, abhinaya, making it “a temporary trans‐gendering” (Reference Mitra2015:140– 41).

Galtney certainly embodies femininity, but the dance comprises a range of movements across a wide gender spectrum rather than a performative expression of a singular, gendered body. As Galtney describes, “It’s more than just acting. It’s much more authentic than that. You really have to put yourself in that place, and be in your body, and just go” (The Minnesota Daily 2015). The Horidraa choreography highlights the specific implications of black, gender‐nonconforming, trans, queer bodies dancing when the subject of the dance shares the messages of the Black Lives Matter movement. As Galtney frames it: “I really want people to just leave knowing that there’s a positive force within the work. But that doesn’t mean to forget the struggle, the pain. I think it should be a reminder of where we need to be and where we are” (The Minnesota Daily 2015). Horidraa places our two solos together to highlight the intersectional experiences of black bodies in the face of state‐sponsored violence.

Ananya Chatterjea’s choreography also utilizes the movement of the full ensemble to address these issues. In another moment of Horidraa, the dancers rush to center stage so they can reach their fists down toward their hips and gaze forcefully at one another with torsos angling forward. Galtney jumps out away from the ensemble and sits in chauk with arms reaching out directly to the group. Lela Pierce forces her way out to come nearby, throwing her hands toward Galtney’s face with widely spread fingers. The movement of the ensemble builds as they all swiftly jump off the floor in chauk. Then they begin to walk forward with clenched fists striking across their bodies. Pierce points her index finger and opens her mouth wide in silent laughter. She turns, falls repeatedly on one leg, and begins to grab the knee of the lifted leg. Turning her torso, she raises her arm with the stretched open fingers of alapadma. The dancers run to center thrusting out their torsos aggressively, even violently. Chatterjea’s use of odissi dance offers a complex pattern of rhythmic shifts and layers, allowing the dance to build up and to break off into solos and variations on a movement sequence.

The yogic sequence of Horidraa focuses the dance on healing, shifting the movement to an entirely different pace, igniting the breath and lengthening the body in a single pose. Coming forward, Pierce opens her mouth, moves her hand toward the audience, and brings the thumb and third finger to touch in mayura. Pierce gestures up with the shape of a flower’s petals in one hand as Wilcox, Galtney, and Chatterjea are on their knees, lifting one arm upward, their hands reflecting the flower form with hamsasya and alapadma gestures. Now in unison, they sit hips down in a squat, look up, and then move one leg forward in a lunge. Putting their palms down on the floor, they push up and quickly switch their legs beneath them. Moving their bodies to balance on one palm and the side edges of the feet, they take Side Plank pose with their raised hands alternating between alapadma and the tight‐fisted mushti. They drop down into a Plank pose with both hands on the floor, then bring one foot forward to a lunge.

Significantly, Chatterjea has choreographed the dancers’ movements, but Lela Pierce comes to the front of the group at critical moments. As a mixed‐race artist of African and European descent, Pierce is located within multiple subjectivities and identities. And as the piece goes on, her dancing intersects with an image of my own body that is projected on the scrim behind the dancers. This emphasizes for me the complexity of racial and gendered identities embodied by all of the dancers in the work. In this moment, Pierce comes forward with the flower mudra and my silhouette appears on the screen. It looks like a shadow with red shading, creating a sunset around the dark image that is my actual body on display. Pierce raises her arms in the “hands up don’t shoot” gesture protestors use as a physical statement that their bodies pose no threat to police officers. It is a peaceful gesture in contrast to the energetic, aggressive movement of the previous section. Dancers then fall to the floor, lying on their sides, shaking their torsos. Then, they take a swift turn on the floor; torsos upright, on their knees and sitting back on their heels, they press one knee out to the side, bring the other knee in, and repeat the movement.

Yoga is the final lead‐up to Horidraa’s climactic moment; the flower, an image of beauty and calm, is held up after an extended period of exhausting movement — a physical struggle. Together, as ADT dancers, our bodies are a reminder of the reality of the diversity of black femme bodies who have founded, created, and envisioned black liberation movements such as Black Lives Matter. ADT’s quintet Work Women Do brought together black and brown women and femmes as part of the company’s vision to engage in social justice concerns and focus attention on the interlocking oppressions faced by these women and people of color in the US.

Racially Mixed and White Bodies in Choreographies of Capitalism

In ADT, efforts to grapple with issues of racial and gender equality operate alongside the company’s long‐term focus on the problems inherent in capitalism. Through a thematic focus on systemic violence and the imbalanced distribution of global resources, the company has driven forward its interest in the impact of these structural inequities on queer, black, and brown women and femmes. In line with this, Chatterjea centered the 2012 Moreechika: Season of Mirage on “The mirage of a desirable notion of ‘progress’ where we relentlessly consume material objects, not realizing that we are also exhausting our reserves of non‐renewable vital resources” (Chatterjea Reference Chatterjea2012b). So while her memories of South Asian women’s stories have been at the root of her creative focus on gender and violence, she has broadened this interest to take economic injustice into account. Gender and sexuality studies scholars such as M. Jacqui Alexander have insisted that embodied practices play a major role in establishing a feminist praxis to deal with economic and social conditions because the body constitutes a source of knowledge that is perpetually “summoned in the service of capital” (Reference Alexander2005:329). ADT took this 2012 piece as an opportunity to translate individual experiences into a collective engagement with the economic marginalization of black and brown women and femmes.

In Shaatranga, Chatterjea crafted an evening‐length dance that journeyed into African and Asian histories of economic oppression as its foundation. Rather than shying away from the historical reality of violence, Chatterjea and the ensemble sought to deeply understand oppression and agency through the piece’s focus on indigo. As Chatterjea described:

The history of indigo is particularly poignant for me: forced to cultivate indigo instead of food crops by British colonizers, farmers in my home state of West Bengal rose up in revolt in 1859. This Indigo Revolt, where many farmers were ultimately put to death after a mock trial, was an early spark for the anti‐colonial movement. (AnanyaDanceTheatre.org 2018)

The history of the indigo industry in West Bengal began in 1777 when the Frenchman Louis Bonnaud established it there. When the number of factories increased from two to four hundred, Bengal became the largest producer of the material in India and a major exporter of indigo to England. Amidst these financial gains, planters were intimidating workers through violence, sexual assault, kidnappings, and extortion: “In the wake of the indigo rebellion, or ‘blue mutiny’ as it was called, peasants attacked factories and planters’ homes and beat up their European managers” (Bhatia Reference Bhatia2004:22). Shaatranga incorporated this understanding of resistance to economic subordination and systemic oppression, while simultaneously highlighting other labors, such as that of African slaves in the Americas.

For instance, the choreography of Shaatranga included a section with dancers Renée Copeland and Felicia Perry, one white and one black female artist, who both display a complex navigation of individual expression and witnessing. Perry entered from stage right wrapped in a long, indigo‐dyed fabric tied around her body from shoulder to hips.Footnote 13 After rushing out, she paused to stretch the fabric by leaning her torso forward and holding her legs in a lunge. She took a few steps with the fabric still tied taut and reached one arm out long from under the fabric, holding up the alapadma mudra and gazing toward the hand. She leaned back and turned to come out of the fabric just enough to reveal her shoulder, her thumb and index finger touching in hamsasya. Turning toward the audience and lowering in chauk, she grabbed the fabric with one hand and shifted to face backstage. In this manner, she swiveled herself around repeatedly until her body was fully out of the fabric. She held it above her head and let go of it as she dropped down to the floor. After this scene Renée Copeland jumped in with arms held up toward Perry, ran to the front of the stage, and dropped to the floor.

Copeland then grabbed hold of the “Navigation Star,” a prop built by scenic designer Chelsea Warren. The Navigation Star was inspired by the company’s visit to the Hókúle‘a canoe of the Polynesian Voyaging Society during their 2018 tour to Maui: “Witnessing the lashings and the precise intersections of ropes and wood pieces used to assess direction in keeping with the star system suggested the value of relationships to time, space, and each other, especially during long and difficult journeys” (AnanyaDanceTheatre.org 2018). The artists held the object, wrapped in colored fabrics, in the beginning and end of the dance as they met one another across histories of oppression rooted in slavery and European colonialism.

Figure 3. Renée Copeland jumping with the legs crossed in swastikapada position in Shaatranga: Women Weaving Worlds. The O’Shaughnessy at St. Catherine University, Saint Paul, MN, 2018. (Photo by Isabel Fajardo; courtesy of Ananya Dance Theatre)

Chatterjea positions Copeland at a particular intersection of the dance: following Perry’s entrance onstage with the indigo‐dyed fabric, and prior to Perry’s solo. This placement of a white female‐bodied artist in the performance of a black female‐bodied artist exemplifies ADT’s radical practice of inclusion, which always places white bodies in relation to black and brown women and femmes. In her solo, Copeland holds the Navigation Star in one hand and reaches the fingertips of the other hand to touch the torn fabric that drapes from it. She stands and then jumps to whip the star around in space, turning two full circles in the air. She lands with her knees crossed, similar to yoga’s Eagle pose. She gazes down at the star, drops down to the floor, shakes the star, and leaves it on the floor. Finding her movement again, she stretches out into yoga’s Side Plank, holding the side edge of her body up to the ceiling while raising her top leg at 90 degrees with her foot flexed. One arm still on the floor, she lifts her top arm; fingers together with only the index finger halfway down, she forms the mudra arala. Reaching to unite with the star, she lifts it and leans back with it to come up in a lunge. She jumps on the standing leg and drops her head back. As if pulled by it, she runs forward with the star ahead of her. Hopping onto one leg near Perry’s body, she folds forward. Stepping onto the opposite leg, she lengthens the arm and holds the open and stretched fingers of the alapadma hand gesture. She moves around Perry, lifting up the star high and lowering down into chauk, while circling the star around her body. Crossing her leg over to turn with the star held overhead, she lands to sit on the other side of Perry.

This is not the first time Chatterjea has positioned Copeland’s dancing in relation to black and brown women’s embodiment. In her duet from Moreechika with dancer Brittany Radke, Copeland performed aggressively by harshly gesturing directions and expressing her desire to physically harm Radke’s body:

I don’t want to abuse Brittany in a duet or be pushed by Hui. I don’t really want to do these things but when it comes to the work, I’ve found that I’m more than capable of going there and it’s because I’m so excited to articulate truth. […] All of my dance training that [Ananya Chatterjea] gave me makes me think about the intersectionality of the material body, a fairytale that we’re in a postracial society, that white supremacy has disappeared and vanquished. I just don’t think we’re anywhere near there. (Copeland Reference Copeland2013)

Just as Chatterjea situates dance artists in the work with an eye toward how their bodies are perceived in the world socially, Copeland traces her own awareness of the realities of white bodies being aligned in relation to black and brown bodies. Copeland is placed in the dance to put on display how white women’s bodies get framed in structural hierarchies and linked to the context of black and brown women. In Shaatranga, though, she is not embodying the violence of racial oppression, but rather navigating the histories of enslavement tied to indigo.Footnote 14 Copeland does so with observation, tension, and care, all while encountering the difficulties of her jumps, turns, and lifts in the dance. She enacts the ongoing practice of what it means to be a white ally by refusing to settle into stagnant guilt or by presuming true understanding of the experiences of “people of color,” instead working actively and continuously to resist and challenge systemic issues.

While the solo moment in Shaatranga was originally choreographed for Felicia Perry, it would be later performed by Alexandra Eady in Sheboygan, Wisconsin.Footnote 15 I had performed in Shaatranga at the O’Shaughnessy, but for this Sheboygan rendition I was an audience member as I had by then moved to Wisconsin while the production toured. I noticed immediately the differences Eady — as a light‐skinned black woman — had found for her narrative. Eady identifies as black American and as a biracial person with African American and Norwegian heritages (Eady Reference Eady2020). She describes the value of racial and gender differences:

I was learning an additional section that I wasn’t normally doing. I learned in that moment that it takes a lot of energy to place my body in the choreography and try to replicate something that was done by someone different. It’s almost impossible. And I realized it wasn’t going to be the same. I realized this after I had to do it. It would have been more successful if I had realized before my black body cannot replace another black woman’s body, especially when it comes to this idea of colorism and privilege. And so, my work when trying to learn that piece and perform that piece and physically do the moves was to create a narrative for myself. (Eady Reference Eady2020)

Eady’s work is another articulation of black women’s stories of continuously having to navigate European and African heritages as a mixed‐race person. Eady has readied herself to embody, relearn, and carry forward experiences of black women to support ADT’s social justice narratives.

In another scene in Shaatranga, Eady’s biracial body further illustrated a structure in which the private interests of individual freedom and competition are prioritized over the social welfare of the majority. Eady emerges onstage carrying a tower of gold‐plated shoes on her head, an image of ultimate luxury. As our attention in the ensemble gravitates toward her, we begin to wrestle each other to take hold of one of these shiny items in Eady’s control. The allure of her presence amidst these objects creates an energetic shift. We sharply slip our feet back behind us, hands to the floor, as we drag ourselves to the front and back of the stage in a Plank pose, rising only briefly to arch our spines backward or flail our arms in a circular motion. After struggling to find our ground, we manage to rise up and pick up the pace of our limbs to run toward the corner until we drop to the floor and clasp our fingers behind our heads. One by one, we roll offstage with our legs extended and arms crossed at the wrists.

Eady embodies the conflicts of capitalism further in her solo “Golden Deer.” She describes this piece as follows:

In this one moment, I had the responsibility of transforming into the “Golden Deer” which led to this piece surrounding “Capitalism.” It was this character that was very desirable but dangerous at the same time. The haunting of material objects was very contrasting to my own reality and that’s why I say performance is not about individuals onstage but is so much greater than that. It was a challenge to be able to switch quickly into these different emotional states of being this character and then being this group who was being affected by capitalism. (Eady Reference Eady2020)

Eady’s emotional work reflects her rasa training as a performer (see Schechner Reference Schechner2001). Rooted in an aesthetic practice of rasa where a complex of sensations is mobilized for storytelling purposes, ADT dancers use their rasa technique as part of their socially engaged investigations. Through capturing the sensations of her character onstage, Eady is taking on the physicality associated with the individualism, greed, and accumulation of wealth for personal gain that encapsulates capitalism.

Figure 4. Alexandra Eady as the Golden Deer in Shaatranga: Women Weaving Worlds. The O’Shaughnessy at St. Catherine University, Saint Paul, MN, 2018. (Photo by Randy Karels; courtesy of Ananya Dance Theatre)

Chatterjea’s choreography for Eady displays an aggressive agility through a series of jumps (see vimeo.com/641982496/4a8f44b4ae). She comes twirling in from stage right. She jumps high up off the floor with arms up, lands, folds her torso forward, and stands back upright with one arm raised in alapadma behind her head, the other arm forward. With fingers now held together in mushti, she quickly lifts and lowers her arms, alternately and in a circular motion. Then she jumps up high and lands three times. She turns swiftly toward the audience and reaches out her arms to snatch and claim an unseen force. She stands with arms toward the audience. Turning to the side, she jumps up again and lands in a lunge.

Eady’s “Golden Deer” solo galvanizes the rhythmic patterns, gestural specificity, and torso fluidity of Yorchhá. She expresses an assertion of power as she takes up space with extensive back bends and swift leaps into the air. She articulates a forceful readiness and vigilance in her footwork and unveils a greedy resourcefulness in the sharpness and reach of her arms. In one sequence she reaches her arms out quickly and then pulls her elbows toward one another at chest height, her fists reaching away from her torso, forming a “V” shape with her forearms. She reaches her arms out to one side and then quickly pulls them back in to bring one fist to an open mouth before punching it out forward. She takes three jumps to the upstage left corner and pauses there to lift her arms up to her face. She holds the bana gesture by making a fist with her hand and then opening the thumb and pinky finger away from the other fingers, resulting in the hand creating a V‐shape. With her swift changes from one move to the next, Eady challenges her audience to predict her next move.

Through Eady’s solo and ensemble dancing, Chatterjea’s choreography expresses how the insatiable desire for personal gain can be detrimental to the collective. When joining the ensemble in the next segment titled “Capitalism,” Eady’s previous show of power diminishes to unearth the complexities of agency and marginalization. When dancers eventually form a line in front of the audience to repeat a movement phrase until the point of exhaustion, Eady is the last one performing the sequence. We all crouch down behind her, until she calls us forward to perform the set once more. Then, we stop abruptly to push ourselves to the back of the stage by stepping quickly on the heels of our feet then dropping to the floor to crawl off. Eady’s dance labor is two‐fold: she embodies the desirable draw of capitalism and its pitfalls. Chatterjea mobilizes Eady’s intersectionality as a black, mixed‐race American to represent black and brown women and femmes who have experienced the oppression of structural racism and economic marginalization.

A practice of radical inclusion is an effort by a choreographer to place specific dancers in solo and ensemble pieces based on the social realities of race and gender. Ananya Dance Theatre reveals how its Yorchhá technique, utilizing the Indian forms of odissi dance, chhau martial arts, and vinyasa yoga, provides a physical and expressive foundation for embodying state‐sanctioned violence against South Asian women and girls and African American persons. Through engagement strategies of collaboration with local communities and audiences, the company employs their dance practice to highlight gender‐, race‐, and religious‐based violence and to participate in the mission of the Black Lives Matter movement. The radical movement practice of ADT further illuminates how cross‐cultural intersections require very careful attention to histories of slavery and colonialism.