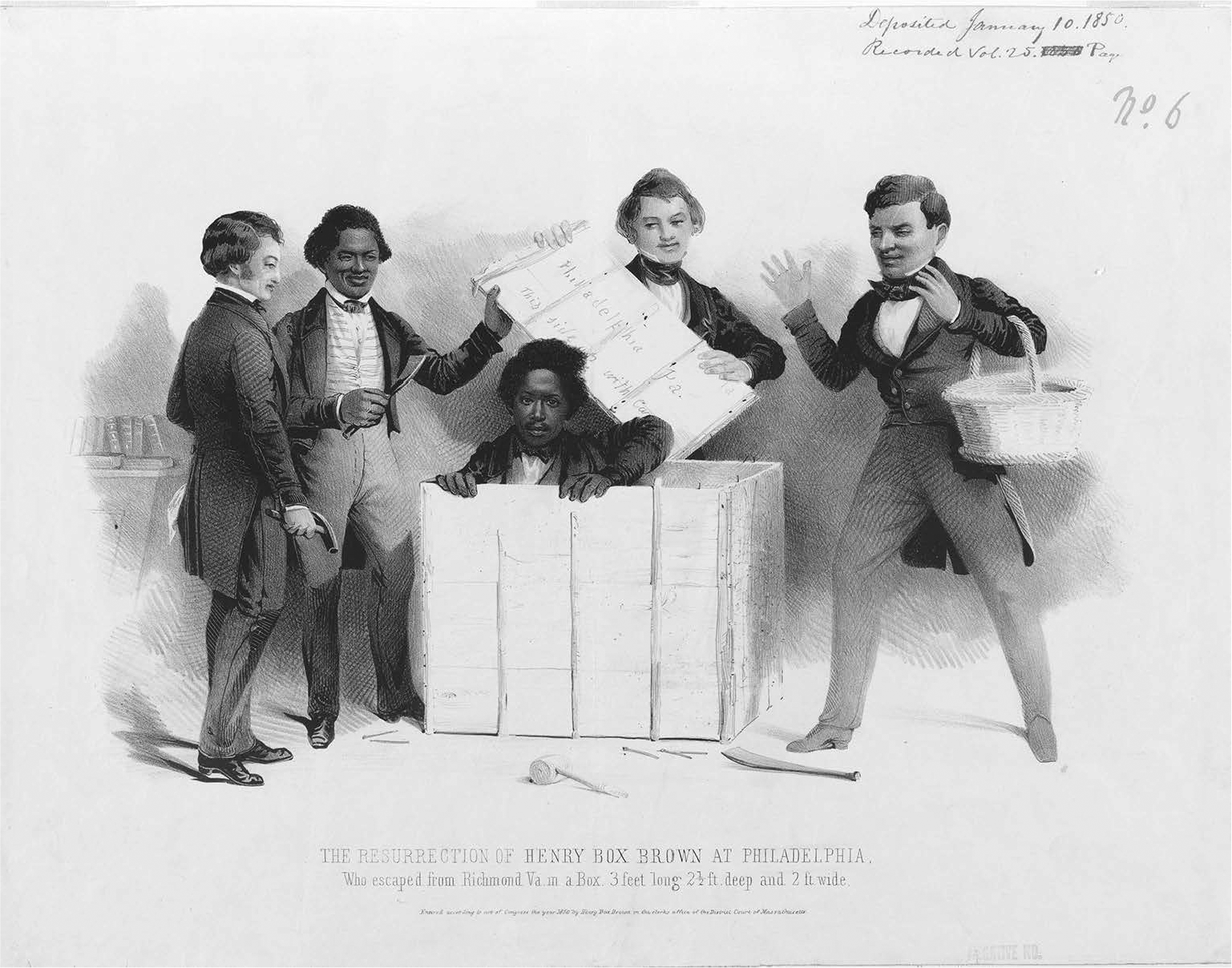

Figure 1. “The Resurrection of Henry Box Brown at Philadelphia / Who escaped from Richmond Va. in a Box 3 feet long 2 1/2 ft. deep and 2 ft. wide.” Lithograph, published by A. Donnelly, no. 19 1/2 Courtland St., NY, ca. 1850. (Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Broadside Collection, portfolio 65, no. 16)

[E]very people should be the originators of their own designs, the projector of their own schemes, and creators of events that lead to their destiny.

—Martin Delany (Reference Delany1852:209)

I’m enough of an artist to draw freely on my imagination, which I think is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.

—Albert Einstein (Reference Einstein1929)

Brown was a man of invention as well as a hero.

—William Still (Reference Still1872:81)

Student Essay Contest Winner

The PhD program in Theater and Performance Studies at UCLA trains a cohort of students who have gone on to careers across the nation and the globe as professors, researchers, and curators. The highly interdisciplinary program is run by a dedicated core faculty — Michelle Liu Carriger, Suk-Young Kim, and Sean Metzger — who have particular strengths in the following areas: East Asia and Asian diaspora, costume and fashion, film, gender and sexuality, media technology, artificial intelligence, performance theory, race, and transnationalism (moving across the Caribbean, England, Russia, Central Asia and beyond from the 19th through the 21st centuries). The program recruits applicants with backgrounds in all areas of specialization and works to tailor the program to fit individual student interests. Students work with UCLA’s world-class research faculty across the university in the fields of their interest. TAPS students are affiliated with the Center for Performance Studies and take full intellectual and artistic advantage of Los Angeles’s cultural riches; previous graduate students have collaborated with the Hammer Museum, Hollywood Fringe Festival, various galleries and theatres, and even formed their own companies. Students maintain easy access to important archives and resources like the Getty Center, Huntington Library, USC’s ONE Archive, and many more.

Henry Box Brown’s secret escape from slavery in a wooden crate mailed to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, perhaps seems inconceivable to a 21st-century audience until they read his slave narrative and the accounts of witnesses. An incredulous reader may also have difficulty being convinced that this ex-slave, who could neither read nor write proficiently, developed an innovative performance agenda on the antislavery lecture circuit in the United States and later departed to Great Britain where he developed his craft as a self-sufficient showman, mesmerist, and self-proclaimed “African prince.” A multitude of scholars have written on Henry Box Brown’s escape and his antislavery activism. Marcus Wood suggests that Brown’s confinement represents “a symbolic entombment of the soul of every slave, in a state of bondage”; whereas his emergence symbolizes “the American spirit emerging from the moral entombment of slavery” (Reference Wood2000:110). Daphne Brooks contends, “Brown exemplifies the role of the alienated and dislocated Black fugitive subject” (Reference Brooks2006:67). However, aside from Jeffrey Ruggles, who curated most of what is archived regarding Brown’s life in the public eye, there is no scholarship in which symbolic or political value is placed on his voice and identity as a magician. Tracking Brown’s life sonically from his proclamation as he waited to be released from his shipping crate to his performances on the 19th-century popular entertainment stage reveals a mode of representation that places him in concert with avantgarde jazz musician and philosopher-poet Sun Ra (1914–1993). Brown was a masterful performer who reached towards a space of alterity and signaled from the margins of Black culture. The works of both Brown and Sun Ra exemplify what I call sonic theatricality, a mode of representation that exceeds expectations of realism through a stylized fashioning of self and sound. Brown’s sonic theatricality in Great Britain ultimately elevated his political purpose by demonstrating his authority in the spaces he occupied as an African prince and mesmerist amongst a white audience— without the assistance of abolitionists.

Sun Ra, named by his mother in Birmingham, Alabama, as Herman Poole Blount, transformed the soundscape of jazz music through his prolific engagement with electronic music and sonic philosophy. His first name, Herman, was inspired by Black Herman, the most prominent African American magician of the early 20th century who also associated with Black cultural nationalists like Marcus Garvey and Booker T. Washington (Szwed Reference Szwed1998:4). Fascinated by Egyptology and cosmic philosophy, Sun Ra named himself after the Egyptian sun god Ra who sails across the sky on a divine vessel known as a solar barque (alternatively spelled bark). Sun Ra leads an arkestra, his neologism that combines the words ark and orchestra. In rhyming with barque, ark alludes to ship-type vessels of the Egyptian god Ra and Noah from the Bible. “Arkestra” emphasizes transportation through sound. Both Brown and Sun Ra transport themselves away from dispossession via vibration.

Figure 2. Image from Space Is the Place (1974) featuring Sun Ra. Directed by John Coney. New York: Plexifilm. (Courtesy of Creative Commons)

Sun Ra ultimately devised a plan of escape for Black people to achieve autonomy outside of the American sociopolitical structure. Similar to the philosophers of antiquity who imagined the universe as a monochord, Gayle Wald asserts, the sonic philosopher and musician Sun Ra envisioned “Black American dispossession in terms of resonance of sound in space” (Reference Wald2011:673). His plan would require space travel to a utopic place that those of African descent could call their own. In the opening of his 1974 sci-fi film Space Is the Place, Sun Ra — dressed in Egyptian-inspired garb and a shiny headpiece—deliberately promenades around a fantastical scene of green landscape while a cacophony of shrieking saxophones and frantic percussion play in the background. With a tranquil demeanor, Sun Ra addresses the viewer without looking directly at the camera as he utters:

The music is different [here… T]he vibrations are different. Not like planet Earth. Planet Earth sound of guns, anger, frustration. There was no one to talk to on planet Earth who would understand. We set up a colony for Black people here. See what they can do on a planet all their own without any white people there. They could drink in the beauty of this planet. Perfect their vibrations—for the better, of course.

(Coney [1974] Reference Coney2003)Comparing the sounds of Sun Ra to Brown’s vocal vibrations highlights how Brown used his sonic resonance as a tool for space-making.

Sun Ra is considered one of the pioneers of what came to be known as Afrofuturism in music, making work in this mode since the 1970s.Footnote 1 Though sci-fi writer Octavia Butler’s novel Kindred ([1979] Reference Butler2003) presents a female protagonist who travels between 1976 Los Angeles, California, and a pre–Civil War Maryland plantation, Afrofuturism remains a relatively untapped resource for unearthing the lived experience of previously enslaved Black individuals. These Black individuals’ collective status as property and three-fifths of a person relegated them to a feigned existence. Therefore, a serious engagement with the Black imaginary seems a suitable exercise in contesting the abolitionist editorial grip on their narratives and in accrediting ex-slaves with the capacity to consider a spectacular destiny outside of slavery. Brown’s biography and performances indicate that he deliberately imagined his future, as demonstrated by his planned escape through a box and subsequent reenactments of this escape in England. As well, his vocal performances as an antislavery lecturer and later as a mesmerist reified for his predominately white audience his autonomous existence. I retain Saidiya Hartman’s practice of “critical fabulation” by combining historical research with critical theory and fictional narrative to not only make productive sense of the scarce archive of Henry Box Brown, but to also offer a more befitting critical analysis of Brown’s actions as radical Black performance.Footnote 2

Henry Box Brown had to remain migratory after his initial escape in 1849, fleeing the United States to Great Britain as a result of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. He challenged the boundaries the slaveholders and abolitionist movement set upon him and evolved his transience in England into a more fluid discovery of self and destiny rather than a fixed position that suited the US abolitionist propaganda. Black abolitionist propaganda encroached upon the narratives of previously enslaved individuals, highlighting the operative tropes of motion, migration, and flight ascribed to the fugitive protagonists. Although Frederick Douglass’s Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave ([1845] Reference Douglass and Gates2012) set the tone for each fugitive slave to be seen as an “American hero” and an agent of their own destiny, Daphne Brooks asserts that this agent became an “1850s peripatetic icon whose migrant travels were put forth precisely to expose the ironies of U.S. domestic enslavement.” Henry Bibb’s Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb (1849) and Solomon Northup’s Twelve Years a Slave (1853), for example, foregrounded roaming Black male bodies with no place of respite in America (Brooks Reference Brooks2006:67). Paradoxically, fugitive Black individuals were fixed in a position of transience, which in turn hindered their ability to assert a selfhood beyond freedom from slavery. The Black subject, Fred Moten declares, is a fugitive desiring to escape racialization, to escape what is considered “proper and proposed” (Reference Moten2018:103). Brown exploits this reality and invents for himself a sprightly existence of perpetual movement toward that escape.

Innovators of Afrofuturism draw on the imaginary future, themes of freedom, pursuit of the impossible, and ancient African myths as means to interpret, transcend, and resist the oppressive conditions of black experiences. British editor Mark Sinker in 1992 started to write reviews on Black science fiction after visiting the United States where he was inspired by African American musician Greg Tate’s writing on the intersections of Black science fiction and Black music. Sinker also drew comparisons between the 1982 sci-fi film Blade Runner and slavery, comparing alien abduction to real events that occurred during slavery (Eshun Reference Eshun1998). Sociologist Ytasha Womack asserts, “The alien [other] motif reveals dissonance while also providing a prism through which to view the power of the imagination, aspiration, and creativity channeled in resisting dehumanization efforts” (Reference Womack2013:37). It is in this prism where both Brown and Sun Ra strive for their transcendence through time and space.

Reconsidering the Symbolic Value of Brown’s Box

Henry Box Brown’s journey began on the morning of 23 March 1849.Footnote 3 On that day, the 34-year-old, after equipping his mind for the “battle of liberty” he had accepted, folded himself into an approximately 3'1" high by 2'6" deep by 2' wide wooden crate. Brown’s friends nailed the lid of the box shut after puncturing three holes for air and had him conveyed to the postal office. The crate was shipped from Richmond, Virginia, to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, via the Adams Express Postal service. After 27 grueling hours, the box that contained Brown arrived, addressed to a friend of Dr. James C.A. Smith, Brown’s free Black associate, located in Philadelphia. Brown articulates his impetus for escape in his 1851 Narrative:

I now began to get weary of my bonds; and earnestly panted after liberty […] One day, while I was at work […] I felt my soul called out to heaven to breathe a prayer to Almighty God […] when the idea suddenly flashed across my mind of shutting myself up in a box, and getting myself conveyed as dry goods to a free state […] buoyed up by the prospect of freedom and increased hatred to slavery I was willing to dare even death itself rather than endure any longer the clanking of those galling chains.

(Brown [1851] Reference Smith2002:56–58)Footnote 4He desired freedom at any cost, even to the extent of temporarily confining himself in a box with the hopes of escaping what he called his “life in chains” (51). The chains serving as a literal and metaphoric representation of slavery produced a sonic resonance that presumably haunted Brown after he watched in horror as his wife and children were physically “loaded with chains” and made to journey on foot to another plantation and another set of metaphoric chains (43). When his two friends tacked the box shut a year later, perhaps the sound of the chains that imprisoned his body and soul ceased and were replaced with prolonged stillness and the silence of an imminent yet uncertain future. Following the treacherous and claustrophobic journey by train and a brief recovery upon the box being opened, Brown moved into a “hymn of thanksgiving,” which he revised from Psalm 40 to praise God for his deliverance. He believed he had risen from the dead to inherit the possession of his natural rights. That same day, following a bath and refreshment, Brown travelled to a few homes of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society committee members for welcome receptions.

The symbolic value of Brown’s box has often been discussed in scholarship in terms of either signifying or “reversing” the hellacious conditions of the Middle Passage, when Africans were, as Richard Newman describes it, “unmercifully packed together in sailing ships […P]ressed into enclosures little more than living tombs […as] nonhuman products of the commodity market, they were crammed into spaces designed only to maximize numbers and profits” (2002:xxx). Scholars have revisited the Narrative of Henry Box Brown to elucidate the symbolism behind his escape and the box itself. Recent books and articles by Cynthia Griffin Wolff, Henry Louis Gates Jr., Richard Newman, Jeffrey Ruggles, Marcus Wood, and Daphne Brooks illuminate the appeal his narrative retains into the 21st century. Gates articulates in the 2002 edition of Brown’s Narrative that the fascination with Brown’s tale

stems, in part, from the fact that Brown made literal much that was implicit in the symbolism of enslavement. Slavery was a form of “social death,” as the sociologist Orlando Patterson has famously discussed. The slave narratives were “narratives of ascent,” as Robert Stepto has argued, stories of deliverance not only from slavery to freedom and South to North but also, in Patterson’s sense, from social death to social life, even if a less than perfect life of a black person in the North of antebellum America. Brown names this symbolic relation between death and life by having himself confined in a virtual casket. He “descends” in what must have been a hellacious passage of the train ride—sweltering, suffocating, claustrophobic, unsanitary, devoid of light, food, and water—only to be resurrected twenty-seven hours later in the heavenly city of freedom and brotherly love that Philadelphia represented.

(Gates Reference Gates2002:ix) Footnote 5Gates here moderates a dialogue between Orlando Patterson and Robert Stepto to demonstrate the sociological and temporal implications Brown’s act rendered. He imagines the conditions inside the box to identify the fortitude and endurance Brown must have possessed in order to survive his conveyance. Brown moved through both horizontal and vertical spaces, from Richmond to Philadelphia and social death to social life, respectively. Hollis Robbins provides a concise synthesis of these scholars’ conceptualizations of Brown’s escape and claims that their signification of his confinement served as an “allegory for the Middle Passage and a metaphor for the oppressions of slavery and for the rigid roles and categories imposed on fugitive Black slaves and their narratives” (Reference Robbins2009:6).

Perceiving the box akin to a time machine, however, prefigures Brown as an inventor with the adroit capacity for designing his own destiny. A machine is defined as “a vehicle or conveyance” or an “apparatus consisting of interrelated parts with separate functions used in the performance of some kind of work.”Footnote 6 Brown’s machine included interior and exterior parts that facilitated his transport. Made of wood and nails, inside the box alongside himself was his hat for fanning, a gimlet for drilling small holes in the box, some crackers, and a limited supply of water for quenching his thirst and wetting his face, stored in a beef bladder (Brown [1851] 2002). The elements inside his box suited his physiological needs in order to stay alive during his transport of 350 miles. The exterior of the box displayed an address to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and the instructions “This side up with care” (Ruggles Reference Ruggles2003:32). Most critical to the function of his machine was the address, as this part initiated the functions of all the other parts to make his time travel possible.

The concept of a time machine in the English-speaking world was first published in the 1890s by English writer Herbert George Wells, famously known as H.G. Wells. His completed novella The Time Machine was published in 1895 when Wells was 34 years old. The book has been adapted into film both in 1960 and 2002. Since its introduction, the idea of time travel has influenced the core of the mainstream science fiction genre and technological innovation in general, such as space exploration and gadgets that assist in time management. The novella begins with the narrator and a group of men listening to the Time Traveller, a scientist by profession, as he discusses the fourth dimension: time. During a particular lecture to his weekly dinner guests in his drawing room at his home in an area of London called Richmond, the Time Traveller claims to have created a machine that allows a person to travel through time. Met with objection, he performs a demonstration of time travel with a preliminary model of the time machine he has been developing for two years. His demonstration requires the participation of his guests as validation of his magical exhibition. The Narrator describes the model as a “glittering metallic framework, scarcely larger than a small clock, and very delicately made. There was ivory in it, and some translucent crystalline substance” (Wells [1895] Reference Wells2011:22). Placing the mechanism on the table in a room brilliantly lit by candles and sitting in a chair close to the table, the Time Traveller instructs the Psychologist to push the lever on the model. The Psychologist’s intervention causes the machine to disappear from the table. By having the Psychologist push the lever and bear witness to the subsequent radical event, the Time Traveller attempts to perhaps verify his sanity or dismiss his lunacy. Nevertheless, the narrator and the Psychologist are in disbelief. The narrator rationalizes his skepticism by claiming that the Time Traveller is “one of those men who are too clever to be believed. You never felt that you saw all round him; you always suspected some subtle reserve, some ingenuity in ambush, behind his lucid frankness” (31). At their next meeting in the Time Traveller’s home, the Time Traveller arrives later than his guests with a surprising entrance, weary and disheveled. His coat and hair are dirty and dusty, his face a “ghastly pale…his chin had a brown cut on it—a cut half healed; his expression was haggard and drawn, as by intense suffering” (35). Following a brief recovery, the Time Traveller sits down to tell his story of successful time travel to the future, the year of 802,701 AD, where he meets the Eloi—humanoids that inhabit a paradisiacal society.

Besides H.G. Wells and Henry Box Brown being the same age when their time machine went out into the world from a location called Richmond, the Time Traveller’s mission to travel through time and space despite reasonable objections resembles Brown’s. Their objective was the same: to manifest the hope that there was more to life than what anyone could perceive in the moment. Though chronologically consistent, Brown’s first-time travel with his machine permitted him to assert his agency and emancipate himself in 1849 as the federal laws of the United States neither recognized nor protected his natural rights. He invented the seemingly impossible in a time frame that did not appear conducive to his imagination, leaping first into 1863, and then eventually into his own space of alterity where he possessed the status of African prince. Considered by his friends as cleverly mysterious, one can imagine the tireless hours the Time Traveller spent working on a dream that no one would initially believe, a dream that when achieved would result in physical pain. Both the Time Traveller and Brown did not see their intense suffering within their machines as more significant than their destinations.

Neither the Time Traveller nor Brown knew with certainty whether their bodies would survive their expeditions or the conditions of their destinations. In this context, the race of the body did not necessarily dictate the severity of the affliction. Both the black and white body were subjected to wounds and physical weariness on their perilous journey, which they embarked on to defy their current reality. However, the US politics of racial difference required Brown to self-inflict pain as the starting point for his liberty battle. He paradoxically needed to exacerbate his physical pain as a means of attaining his freedom. To avoid suspicion of his escape, he decided he needed to be excused from work for a few days to prepare. As a result, Brown poured oil of vitriol on his already inflamed finger in hopes of being granted excusal. Dropping more than intended, however, the oil had very soon eaten into the bone (Brown [1851] 2002). Brown’s confinement granted him liberation from slavery, and just as paradoxically his disabled finger contributed to his mobility. Upon receiving permission for a leave of absence, Brown never again mentions his injury or even whether he bandaged it as his overseer recommended. No appearance of injury appears in any of the recovered printed images of Brown emerging from the box despite the fact that his injury was probably still healing when he arrived in Philadelphia. Thus, Brown used a chemical to alter his body and performed disability when in fact he was able to endure even greater pain while being confined and tossed around in his box.

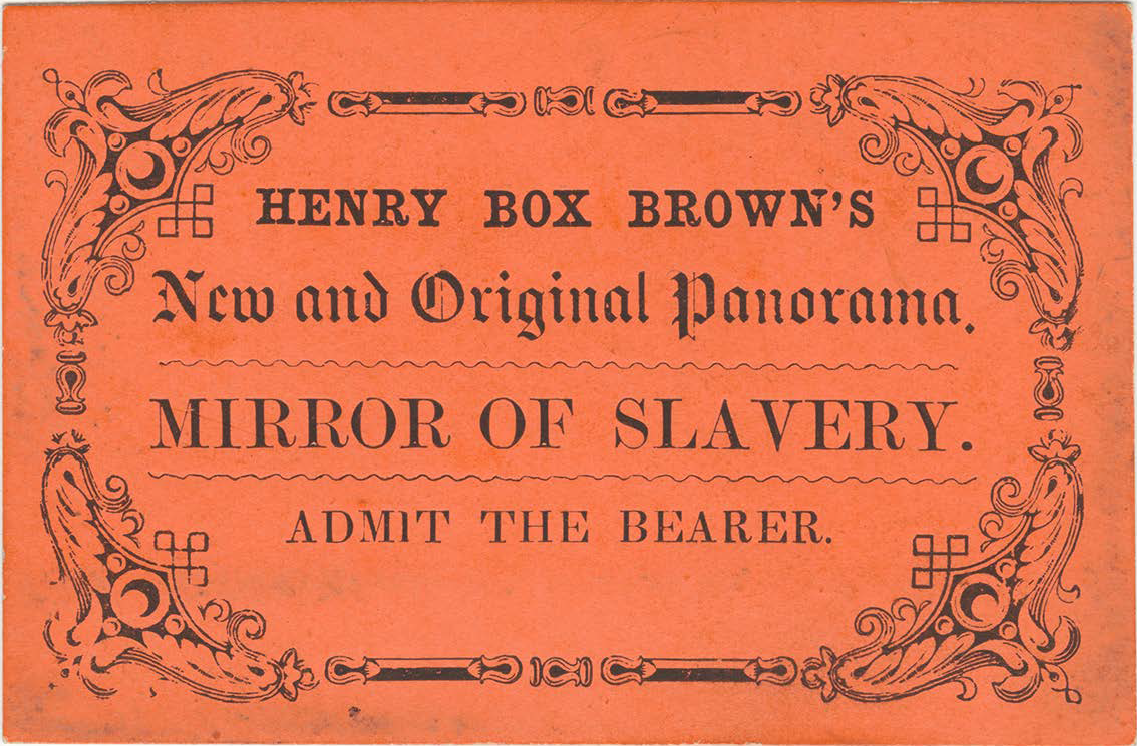

In an effort to avoid re-enslavement after the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 months after arriving in Philadelphia, Brown and his free Black associate James C.A. Smith headed to England in October 1850. There, Brown displayed his moving panorama about the horrors of American slavery, which he first exhibited in Boston in April 1850. Called the “Mirror of Slavery,” it told the story of his escape both in and outside of theatrical venues. Often performing in mill towns for working-class audience members, Brown began his first tour in Britain in November 1850. He brought with him the original box in which he escaped slavery; as a spectacular vessel the box assisted in reconstituting Brown’s identity in Britain. Like Sun Ra, who traversed and possessed space, Henry Box Brown introduced himself to the British public as a magical escape artist, arriving in a box he transformed into an esoteric vessel through staged performance.

Figure 3. Ticket to “Henry Box Brown’s new and original panorama, Mirror of slavery,” mid-1800s. May Anti-Slavery manuscript collection, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library, Collection #4601, Box 15. (Artstor, library.artstor.org/asset/SS35197_35197_19460132)

The “Great Attraction Caused in England”

On 22 May 1851 Henry Box Brown staged a grandiose reenactment of his March 1849 escape, which the Leeds Mercury called the “Great Attraction Caused in England” (in Ruggles Reference Ruggles2003:127). His box, transported to England, allowed for the reenactment of his original escape, this time from Bradford to Leeds. With this second performance of traveling in his box, this time for three hours, Brown territorializes his performance spaces; that is, before a white audience, he subscribes to the identity of an escape artist while resisting the status of a fugitive in and through geographic and social space.

Brown “was packed up in the box at Bradford” and “forwarded to Leeds” on the 6:00 p.m. train, stated the Leeds Mercury:

On arriving at the Wellington station, the box was placed in a coach, and preceded by a band of music and banners, representing the stars and stripes of America, paraded through the principal streets of the town […T]he procession was attended by an immense concourse of spectators. [James C.A. Smith] rode in the coach with the box, and afterwards opened it at the Music Hall.

(in Ruggles Reference Ruggles2003:127)The author of The Unboxing of Henry Brown, Jeffrey Ruggles, indicates that Brown confined himself in the box for two and three-quarter hours and his reemergence took place at 8:15 p.m. within the hall on Albion street (127).

The stakes of Brown’s reenactment in England were much lower than his 1849 escape; his performance exhibits a desire to be memorialized. During his reenactment Brown was neither at risk of dying, returning to slavery, nor being turned on his head for two and a half hours as he was in his 1849 escape. He was confined for no more than three hours, a fraction of the arduous hours of silence he originally had to endure. Despite being in the box for an abridged amount of time and having more control of his conditions, which allowed him to “speak to Smith and listen to the fanfare, […with] a few peepholes in the box,” there were still physiological challenges he could not control (128). His lung capacity was still probably compromised, legs cramped and brow profusely perspiring. Brown endured the temporary physical pain so that he could make an everlasting impression on his new English audience. He surmounted his projected “social death” in the American South by repeating his resurrection from the box, adding acts of magic to create an act that initiated his immortality.

Brown’s reenactment incited other reincarnations that reach into the 21st century. An event on 11 July 2008 at the Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester, England, was a reenactment of Henry Box Brown’s 22 May 1851 reenactment. Before factory machines and ambient noise, a slim, 5'9" British male of African descent emerged from a wooden box before a small audience and recited portions of Henry Box Brown’s written narrative. The actor had confined himself to a crate of the same dimensions as Brown’s for almost a half hour before his emergence. A tobacco processor in his former life as a slave, Brown “reappeared” that day in the Museum of Science and Industry exhibiting his triumph over coerced, mechanical labor, even that of underpaid white mill workers of the 19th century. His entrapment and reemergence as a man no longer under the grip of slavery, with depictions of industrialization in the background, staged a resistance to the Western world’s drive towards avid industrialization.

The actor reflected on his experience, emphasizing the physical and mental endurance one had to undergo to genuinely imagine the trepidation Brown incurred the first time: “It had to be experienced rather than imagined”:

My use of the box today was all of 25 minutes, but even then [he leans forward for emphasis] when I got out of the box, I felt faint. So when I was now delivering my lines, I was about to faint. And, I had to sit down because otherwise I would have passed out […O]bviously it was not a huge space, so there’s a lack of oxygen in there naturally. That plus being confronted with strangers [leans forward for emphasis] which is exactly what happened to him of course when he first stepped out of the box, so he would have been just as disoriented as I was.

(RevealingHistories 2008)The actor becomes the student and engages in experiential learning in order to develop an understanding of Brown’s experience. He uses his Black body in a way that imitates the labor of a Black body in the imagined past. Here, he foregrounds the body as integral to reenactment, central to the cultivation of a deeper understanding of Brown’s journey of 27 hours. The actor and his audience are invited to participate in what Rebecca Schneider calls in Performing Remains a “loosen[ing] of the habit of linear time” (2011:19). By staging a reenactment of a reenactment in reference to Brown’s original escape, the actor and the sponsoring institution throw the audience into a crosshatch of overlapping temporalities. As theatre is a time-based art, the informed audience knows that what they see onstage is in real time, thus there is collision between 1851 and 2008. Secondly, as this reenactment is staged as a recurrence of the original escape from 1849, the linear paths of 1849, 1851, and 2008 intersect. There is a certain logic of “reversibility” as Maurice Merleau-Ponty puts it; one time is encased in another (Reference Merleau-Ponty and Lefort1968).Footnote 7 The reenactment seeks to harbor an authentic moment while also bringing a trace of Henry Box Brown into the present, his future.

Science and science fiction can inform our understanding of history and futurisms. Neil deGrasse Tyson claims:

If you go to a higher dimension, it’s not unrealistic to think that you step out of the time dimension and now you look at time as though we look at space […] And so, if your whole timeline is laid out in front of you, then you have access to it, and you can jump in at any point; relive it.

(in Business Insider 2014)History is usually based on looking back; futurisms are inherently based on looking forward. However, both higher dimensions of time and performance are based on the “now” with extensions to the past, present, and future. Likewise, science fiction gives me a license to simultaneously engage all three temporal registers within one man: Henry Box Brown. His ancestry originated in Africa, and yet he was born with a death sentence as an enslaved person within the United States. His perpetual death was removed by his rebirth, when he exited his timeline to jump into his future as a freeman and eventually as a showman and magician. Sun Ra saw his time laid out in front of him by believing that he was from a higher dimension: outer space. I take the liberty of “jumping in” at any point in both Brown’s and Sun Ra’s stories as a practice of experimental historiography.

Figure 4. Sun Ra. Still from Space Is the Place (1974), directed by John Coney. New York: Plexifilm. (Screenshot courtesy of TDR)

The Sounds of Sun Ra and the African Prince

Brown’s embodied behaviors and voice are radical Black performances. Shana Redmond—an interdisciplinary scholar of music, race, and politics—draws on Avery Gordon’s work in Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination ([1997] Reference Gordon2008) in her conceptualization of the term “vibration”: “Vibration is a call, a reminder, an alert deserving attention and response, leaving a ‘something to be done’” (Reference Redmond2020:1). Like Sun Ra’s professed status as an Egyptian god, Brown’s impulse for an alternative future motivates his shift from oppression to the eventual “King of All Mesmerists” and “African prince.” Intertwined with theatrical storytelling and esoteric undertakings in stage magic and cosmology respectively, both Sun Ra and Brown invoked a call and alert to their royal lineage in a mythic Africa despite their mistreatment in the United States. Furthermore, the sound and vibrations of Henry Box Brown and Sun Ra induce a vortex of overlapping time registers that remind audience members of their coerced alienation from their respective homelands and their deliberate return to higher dimensions of freedom.

I hear Brown’s voice with an Afrofuturist ear. I imagine how the vibrations of his voice, which incited the feelings first of James McKim who opened the box in Philadelphia and then of his small audience of three others, facilitated his progress toward a space of alterity. I, therefore, return agency to the vocalizer in his impulse for an imagined future. Sun Ra:

People are just like receivers, they’re like speakers, too, like amplifiers […] If you play certain harmonies, these strings will vibrate in people’s ears and touch different nerves in the body […] My music does have a vibration somewhere within it that can reach every person in the audience through feeling.

(in Stokes Reference Stokes1991:234)The cosmic musician thus asserts with confidence his ability to produce affect in his listeners through his reverberating vocal chants and free jazz melody, a method that Henry Box Brown continued to craft throughout his career, first as an antislavery lecturer then later as a popular magician and mesmerist.

The first testament of Brown’s escape was not his visible emergence from his box as previous scholars have emphasized, but instead the vocal vibrations of Brown responding to his new acquaintance Miller McKim, the white abolitionist. Before Brown’s box was actually opened upon his arrival at the appropriate address in 1849, Brown indicated he heard a voice inquire of him, “Is all right within?” He replied with the confirmation that it was all right (Brown [1851] 2002:62). The sound of Brown’s voice—air pressed and stretched as vibration through his chest, throat, and head—declared his mission successful, as it indicated that breath was still in him after his tempestuous journey. Neither Brown nor McKim could see one another upon their initial meeting; the box hindered sight but allowed for the resonance of sound. Furthermore, Brown’s body entered into the North first, revealed by the vibration of Brown’s voice, symbolizing the presence of life, not death; man, not chattel. The presence of Brown’s voice testified to a Black body with subjectivity—a human being with feelings—before his spectacular emergence from the box.

Listening to the presumably muffled sound of his own breathing for many hours, Brown was finally able to communicate and be affirmed in his subjectivity, in contrast to being someone’s property upon his arrival in Philadelphia. Following his brief recovery from the journey, the first thing Brown did after emerging from the box was sing; he filled the new space with the melodic sounds that revealed his freedom. Henry Box Brown had been confined to complete silence for more than a day and restricted to virtual silence his entire life. However, the sound of his breathing and his strong voice as he sang a hymn of thanksgiving adapted from Psalm 40 upon his emergence from the box indicated his vitality; his song initiated his new life as a free man. African American abolitionist William Still, who was present at the event, indicated that Brown sang “most touchingly” and to the “delight of his small audience” (1872:83). Brown’s voice that day demonstrated—foreshadowed even—the affective power of his voice.

Brown’s song served as a flag of victory in his new space, which he would now inhabit and where he would soon transform. Still reported that Henry Brown briefly stepped away from the others during his welcome reception and “promenaded the yard flushed with victory” ([1851] 2002:84). Josh Kun determines in Audiotopia: Music, Race, and America that “music is experienced not only as sound that goes into our ears and vibrates through our bones but as space that we can enter into, encounter, move around in, inhabit, be safe in, learn from” (Reference Kun2005:2). Brown’s hymn shepherded him into a Northeastern antislavery framework that endowed him with a Black subjectivity. Northeastern middle-class listeners of the Anti-Slavery Society might have classified Brown’s adaptation of the psalm as a negro spiritual regardless of what his song actually sounded like. Ethnosympathy, defined by social theorist Jon Cruz as a charitable reconsideration of the inner world of “distinctive and collectively classifiable subjects,” determined the “negro spiritual” to be a preferred cultural expression by Blacks (Reference Cruz1999:3–4). Ethnosympathy ushered in Brown as a culturally expressive subject.

Seeking to capture here what is evanescent: sound is periodic waves of air molecules that hit the listener’s eardrums and create vibrations inside the body. Sound is material-dependent. Its resonance, or reverberation, is reinforced by vibrations reflecting from a surface or by the synchronous vibration of a neighboring object. Besides “a sound or vibration produced in one object that is caused by the sound or vibration produced in another,” Merriam-Webster also describes resonance as “the quality of sound that stays loud, clear and deep for a long time” or “a quality that makes something personally meaningful or significant.”Footnote 8 I hear Henry Brown’s voice as one that resonates physically and aesthetically with his listeners, cutting through the seemingly sanctimonious soundscape of the 19th–century US American North. I enact the method of what historian Bruce R. Smith calls “historical phenomenology,” through which I discover Brown’s voice as embodied knowledge through historically constructed forms such as newspapers, transcripts of speeches, and letters (Reference Smith2002:2). Like Sun Ra, Brown used his bodily and vocal performance to exceed the social and political platforms of American culture and transcend to a virtual space that did not adhere to the oppressive constraints of his birthplace. The listener is an “active agent” who plays an integral role in shaping and disseminating her or his perspectives of someone’s voice (see Eidsheim Reference Eidsheim2019:177–93). Thus, more important than what Brown’s voice actually sounded like is the impact it had on those listening to it. Within this context, my quest here is to read and hear Brown’s voice as a resonance of sound through space.

Attending the New England Anti-Slavery Convention of 1849 in New York for the first time, Brown was asked to tell the story of his escape and perform an encore of his singing. Jeffrey Ruggles retrieved quotations from archived newspaper clippings that detail the event:

After the speeches, “Henry Brown, by request of many in the audience, again came forward,” reported the Liberator, “and sang, with much feeling and unexpected propriety,” the hymn of thanksgiving he had sung on his arrival in Philadelphia. The National Anti-Slavery Standard stated that “he sang amid profound stillness, but when he concluded, the air was rent with loud applause.”

(2003:40)This experience may have been Brown’s first solo performance in front of such a large audience, though he was accustomed to public singing as a member of his church choir back in Richmond, Virginia. Based on the opinions of the journalist who submitted to the newspaper, Brown commanded his space onstage and throughout the hall, commissioning his voice to reverberate across the entire room. An “unexpected propriety” describes Brown’s overall performance. Thus, he exceeded the expectations of his listener, presenting a kind of corrective to the parodical representations of Black people running rampant in the popular entertainment of blackface minstrelsy.

Like Sun Ra, Brown aspired for songs to be emancipatory and not to present the Black subject as downtrodden and subjugated to his conditions of slavery (see Lock Reference Lock, Ellington and Braxton1999). Brown would revise popular 19th-century popular songs to tell the story of his successful escape from slavery. Although Brown’s “hymn of thanksgiving” did not directly overlap with black vernacular expression, Daphne Brooks contends that key elements of the negro spiritual such as “rigorous aesthetic innovation and an almost ritualistic investment in revision and improvisation” stylistically influenced Brown’s vocal performance (2006:116). Brown went on to sing and revise other songs as he gained popularity on the antislavery lecture circuit. He applied new lyrics to the popular tune “Uncle Ned” (1848) composed by Stephen Foster, the most famous and prolific American composer and songwriter of the 19th century.Footnote 9 Morrison Foster, Stephen Foster’s brother and executor of his estate following his death, indicated in a biographical advertisement that his brother’s ballads and negro melodies

touch a chord in human hearts that, until the Pittsburgher appeared, had lain dormant. He wedded to homely words, in the dialect of the Southern negro, music full of simple pathos, peculiar to itself, and winning a place not granted to the work of other composers.

(in Root Reference Root1991:23)The Southern negro overridden in Morrison Foster’s colorfully worded endorsement of his brother’s music reveals the absence of the negro voice in Stephen Foster’s music. The negro is an overdetermined, collective signifier that permits Foster to fabricate his authoritative voice on negro music.Footnote 10

Brown performs dispossession of Stephen Foster’s ownership of negro melodies by overlaying his sonic resonance and lyrics on Foster’s melody of “Uncle Ned.” Playing off the pathos Foster’s songs supposedly conjured for the white middle-class listener, Brown’s sonic resonance through space utilized the song’s affective power as a recognizable and beloved melody to shift the focus from an imagined negro slave to a freeman in full custody of his own labor and musical ability.

The original lyrics of “Uncle Ned” were written and sung in minstrel dialect. They recall the story of a Black person debasingly referred to as a n[…]r named Uncle Ned whose life value was equated to his hard labor, represented by his use of “de shubble and de hoe.” The lyrics also describe the sadness of the master once the slave died, depicting a “romantic and sentimentalized” version of the mythical South (Newman Reference Newman2002:xxiv). The subversive adaptation Brown created and performed in his dialect-ridden common English vernacular begins:

Have you seen a man by the name of Henry Brown,

Ran away from the South to the North;

Which he would not have done but they stole all his rights,

But they’ll never do the like again.

Chorus

Brown laid down the shovel and the hoe,

Down in the box he did go;

No more slave work for Henry Box Brown,

In the box by express he did go.

(in Newman Reference Newman2002:xxvii)In this segment of his lyrics, Brown portrays that he “ran” from the South to the North. He also emphasizes his transition from the slave Henry Brown to the free Henry Box Brown through a form of travel. Although the lyrics are fundamentally factual, Brown maintains a mythical tone in his poetics, similar to the original lyrics. In Listening to Nineteenth-Century America (Reference Smith2001), Mark M. Smith discusses the acoustemology that English speakers tried to maintain in 19th-century America. He underscores the hyperbolic yet common perspective held by English speakers about both enslaved and free African Americans. English speakers considered the sounds of African Americans as vociferous noise; they insisted, as Bruce R. Smith articulates in The Acoustic World of Early Modern England, that African Americans “chattered like monkeys, they bellowed like beasts, they mourned in chants […] they spoke a language that was no language.” The sound of African Americans and other “a-literate” groups “defied the surveillance of writing […and] threatened the acoustic world of English settlers” (Smith Reference Smith1999:330).Footnote 11 Brown entered this acoustic world, cultivated for more than a century, with a sound that appeared on the surface to emulate the sound of Stephen Foster’s “Uncle Ned,” while also subverting it. As elocution played a major role in the development of the soundscape of 19th-century America, Henry Box Brown likely exceeded the expectations of the white bourgeois listener. The elocutionary ideals of that time included “clarity, contrast, precision, emphasis, variety, fluency, distinction, and balance on vocal as well as visual registers” (Conquergood Reference Conquergood2000:330). Henry Box Brown’s performance aligned more with the elocutionary ideals than the representations of the Black body as barbarous or savage. His musical method illustrated his impulse to transcend expectations as he made space for his voice in soundwaves that flowed parallel to those expected of him.

Brown’s interest in myth-making or -revising went even further in his performances on the antislavery lecture circuit as he retold the “slaveholder’s version of the creation of the human race” in order to draw attention to the slaveholder’s self-interest in asserting his white race as a divinely inspired, supreme race. Within this version of the creation story, there were four people created (instead of two) in which the two Blacks were made to serve the two whites. The two Blacks received a shovel and a hoe, and the two whites received a pen, ink, and paper. The story ended with these final words: “They each proceeded to employ the Instruments which God had sent them, and ever since the colored race have had to labor with the shovel and the hoe, while the rich man works with the pen and ink!” (in Ruggles Reference Ruggles2003:108–09). By telling this fable, Brown satirized the beliefs of his slaveholders and again claimed his significance as not only a human being, but one who successfully relinquished the “shovel and the hoe” and could achieve financial stability. Brown’s clever subversion pushed the boundaries of his spectacular performance to the extent that he would soon need to create new performance material upon the reinvention of himself.

Within a decade of his original escape, Brown started to refer to himself as the African prince during performances and began to indulge in magic and mesmerism.Footnote 12 Jeffrey Ruggles indicates that Brown resurfaced in Wales in 1864 as “the character of an African King, richly dressed, and accompanied by a footman” and then appeared in 1875 New England claiming to be a “blindfolded seer” (2003:159). Samuel Fielden, who recounts his attendance at one of Brown’s exhibitions, asserts, “[Brown] used to march through the streets in front of a brass band, clad in a highly-colored and fantastic garb, with an immense drawn sword in his hand” (1969:142). Although Brown’s procession with flamboyant costuming could have been merely to stimulate interest in his exhibition, his alter ego as an African prince did reflect his proclamation of royal African lineage. Additionally, his colorful garb and jewelry from these limited descriptions suggest that the perception of Africa he insisted on reflecting was imaginatively ancient and inspired by the ancient civilization of Nubia, which Brown first saw in a prevalent antislavery panorama that depicted a romantic tragedy by Charles C. Green. Similarly, Sun Ra was known to wear a conglomeration of colors, glittery suits, and ostentatious hats adorned with Egyptian hieroglyphics, stars, moons, and planets. He considered costumes and music one in the same, claiming that “[c]olors throw out musical sounds” (in Corbett Reference Corbett1994:11). Brown’s marching through the streets in all his colorful splendor produced a sound of freedom that Sun Ra would embody in his outrageous outfits. Nevertheless, both Brown and Sun Ra’s embodiment of inventive or even outrageous identities served as acts of wizardry, disempowering the genealogical grip of slavery on the African American psyche. By maintaining various identities that traversed time, they claimed their capacity to transform and transcend.

The last depictions of Henry Box Brown were as a conjurer, showman, and mesmerizer. The stage in the mid-19th century also doubled as a scientific laboratory for the testing of what we today would call pseudo-scientific theories. However, since there was neither a unified nor regulated institutionalized practice of science, showmen incorporated experimentation into their performances for entertainment. Brown caught on quickly to the popular science entertainment of Britain and learned some of his techniques there from American mesmerist Sheldon Chadwick, also known as Professor Chadwick, among other names. Henry Box Brown mixed a kind of “Africanist” mysticism with the mesmerist protocols of the mid-19th century. In his experimental performances, Brown further distanced himself from the mainstream liberal abolitionist agenda that promoted popular understanding and reform instead of revolution. In contrast, Victorian popular science provided Brown with a platform to create an alliance with the British working class as he would travel frequently to the mill towns in England to perform his magic tricks and lectures on American slavery (Rusert Reference Rusert2012:297). Jeffrey Ruggles asserts that although Brown continued to lecture against slavery, his political purpose had been overtaken by his showmanship (2003:159). As evident in Henry Brown’s renaming of himself as Henry Box Brown or the African prince, names or epithets can serve the process of self-invention and discovery. Brown perhaps also appealed to his working-class white audience because as low-paid and exploited factory and mill workers, they could see their exploitation “reflected” and “amplified” by the figure of an ex-slave from the American South (Rusert Reference Rusert2012:298). I contend, however, that Brown’s showmanship elevated his political purpose by demonstrating his authority in the spaces he occupied as an African prince and mesmerist amongst a white audience without the assistance of abolitionists.

In his role as masterful magician and showman, Brown’s white patrons would have to trust him enough to be hypnotized and manipulated by his voice. In his 1887 autobiography, Fielden, who was a well-known socialist and immigrant from England and was involved in the 1886 Haymarket Riot, relayed details of his impression of Brown’s performance, seen when he was a child laborer working in a cotton mill in Todmorden, Lancashire. He wrote that Brown “was a very good speaker and his entertainment was interesting.” Fielden also recalled, “[t]hese lecturers [Brown and other Black speakers] had a very great effect on my mind, and I could hardly divest myself of their impressions, and I used to frequently find myself dilating much upon the horrors of slavery” (Fielden Reference Fielden and Foner1969:142). Fielden’s comments illustrate the significant impact Brown’s performances had on the British proletariat living in factory towns. Although Brown and the proletariat came from two different backgrounds, he empathized with the conditions of the working class who attended a lot of his shows. Daphne Brooks likens his latter character to that of underworld heroes of picaresque Black urban narratives in his employment of the “‘dark arts’ of illusion, manipulation, and the spectacularly expedient ruse to ‘crossover’ into his own singular realm of freedom” (2006:130). Toward the end of the 1850s, Brown’s performances facilitated his final escape to further exploration in a space only he knew. His voice hailed both his white middle-class and working-class audiences, challenging both groups to consider their positions on how liberation should be achieved.

Within an imaginative cartography of Brown’s escape from slavery and his subsequent spectacular performances, Brown’s inclination of thwarting the conditions of fugitivity and designing a reality contrary to the feigned existence imposed upon him as a Black man is unearthed. Historian Keith Jenkins avows, “History is a shifting discourse constructed by historians and that from the existence of the past no one reading is entailed: change the gaze, shift the perspective and new readings appear” ([1991] Reference Jenkins2003:13–14). Accordingly, I have unboxed Brown by offering an Afrofuturist perspective that tracks Brown’s end as an African prince and magician from his beginnings in Richmond, where he orchestrated his escape from slavery. Given his proclivity for myth-making and innovative transcendence through the vibration and resonance of musical performance, composer and pianist Sun Ra serves as a model for reconsidering the symbolic value of Brown’s vessel and listening to Brown’s voice within a higher register. Perspectives on time and space from science fiction and performance studies have offered ways in which performances of racialized subjects from the past can become configured in the present and future as exemplary models of subverting structures of power and augmenting reality. Brown’s perpetual and radical insurgence deserves another consideration—one that privileges the possibility of a fluid discovery of self and identity outside of abolitionist cultural production.

Henry Box Brown “lives on” today in the remains of his story, which include documents recording his escape and song, lithographs and engravings of Brown emerging from his wooden box, and museum exhibitions such as Baltimore’s National Great Blacks in Wax Museum with its representation of Brown emerging from his box. If Brown and his box are only perceived through the symbolism of the Middle Passage and his resistance to his condition as a slave, perhaps as readers we enslave Brown in our narrow perceptions. As a Black American, he would perpetually be considered an ex-slave, one of the freemen who would soon disappear into the background. Yet, as the “African prince” and “King of All Mesmerizers,” he performed the greatest trick of them all—revealing that his capacity to imagine and execute was far greater than the expectations anyone had of him.