Introduction

As populations age, a considerable economic challenge is ensuring adequate incomes to sustain people in their retirement years. A retirement income security question that has been unexplored is what happens to workers during retirement age when they have been receiving workers’ compensation benefits and not contributing to a state pension. The World Health Organisation estimates that, by 2030, one in six people will be aged 60 or over (WHO 2022). Within OECD countries, the number of people older than 65 years is expected to reach 53% by 2050 (OECD 2021). In Canada, 22.5% of the population will be over age 65 in 2050 (Eisen and Emes Reference Eisen and Emes2022). The ability of workers to fund their retirement years is a significant concern across jurisdictions, recently prompting public riots in France (The Economist 2023). In Canada, employers and employees are required to co-contribute to the Canada Pension Plan (CPP), a statutory programme that pays benefits starting age 65, so that workers have a basic income during pension age. In the UK, workers have a similar arrangement with a state pension (Age UK 2023).

Workers’ compensation boards in Canada are public sector agencies established by provincial government legislation to provide wage-loss, healthcare, rehabilitation, and long-term disability benefits to workers who are injured or become ill during the course of their employment. In the USA in 2021, there were 2.3 workers’ compensation claims filed for every 100 full-time employees (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2022); rates for lost time were similar in Canada (Tucker and Keefe Reference Tucker and Keefe2022). Given gaps in state pension contributions, how do injured workers survive financially when they are of pension age?

The topic of injured worker retirement age pensions has received no attention (so far as we can see) in working life literature, which instead has focused on compensation benefits adequacy for working aged injured workers (Hunt Reference Hunt2003; Tompa et al Reference Tompa, Scott-Marshall, Fang and Mustard2011; Grawey and Durrani Reference Grawey and Durrani2022). A challenge facing vulnerable workers in general is a lack of support when injured. While on workers’ compensation benefits, they have limited access to collective labour representation that includes advocates who can stand up for the rights of workers. The unionisation rate in Canada is low, at 15% in the private sector in 2021 (Statistics Canada 2022b) and 29% overall (both private and public sector) in 2022 (Morissette Reference Morissette2022). As workers on long-term claims have often lost their contact with their former workplace, they have also lost any union representation they might have had. While advice and representation for injured or ill workers in Ontario exist through free advisory and legal clinics and injured worker peer-support groups,Footnote 1 this support is quite limited. There are long waiting lists for legal support and these resources are not well known; they are found and accessed by only a small minority of workers (MacEachen Kosny et al Reference MacEachen, Kosny and Ferrier2007).

The complexity and mundaneness of administrative details around retirement pensions may be a further reason for a lack of media and scholarly attention to the injured worker retirement pensions. However, it is within such mundane administrative details that significant decisions about allocation of resources are made, including decisions framed by ideas about deservingness of benefit recipients (Larsen Reference Larsen2008). In his writings on the nature of power, the French philosopher, Michael Foucault, regularly invoked accounting as a critical element of ‘governmental management’, as it conceptualises what is considered a cost within discourses of abundance and scarcity (Hoskin Reference Hoskin, McKinlay and Pezet2017). Administrative details, as part of strategic calculations behind the apparently smooth functioning of a system, need to be investigated to identify parts amenable to intervention or improvement (Miller Reference Miller1990; McKinlay Reference McKinlay, McKinlay and Pezet2017).

This study is concerned with poverty during pension age among workers who have had long-term workers’ compensation claims. By long term, we mean being in receipt of workers’ compensation benefits for 5 years or more during their working life. In this paper, we focus on the jurisdiction of Ontario, Canada’s most populous province, and describe policy changes in recent years that increased injured worker poverty in older age. Canada is comprised of ten provinces and three territories, which each run their own workers’ compensation authority. This study is timely in that, in 2022, the Ontario Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB) (hereafter called by the generic term ‘workers’ compensation board’ or ‘WCB’) announced that, after years of trimming costs (including workers’ benefits) that were related to an ‘unfunded liability’, this liability was fully funded and there was now a surplus. Despite pressure from some injured worker advocacy groups to restore injured workers’ supports, such as retirement pensions that had been reduced over recent years, the WCB instead allocated the surplus as a rebate for premiums paid by businesses (WSIB Ontario 2022).

In this paper, we address workers’ compensation retirement pension procedures that have operated largely without media or scholarly attention with the aim of bringing to light critical details in workers’ compensation policy that contribute to injured worker poverty in older age. To illustrate this, we used a mixed methods approach applying critical discourse analysis to policy, parliamentary, and media documents and interviewing injured workers and those involved in administering the system to explain Ontario policies related to retirement income for injured workers, rationales put forward in parliament to support a legislative change that increased older worker poverty, and injured workers’ experiences of living under current workers’ compensation pension age policy, including personal distress and poverty.

Methods

We used a critical discourse approach (Cheek Reference Cheek2004) to design our study and make sense of the data collected. Discourses are sets of common assumptions that order reality in a certain way and encourage particular ways of thinking about situations. A critical discourse approach sensitised us to administrative and power structures, such as laws and the economy, that provide the conditions for behaviour. It also drew attention to ways that language is not neutral and can favour certain political views. For instance, business lobby groups may present scenarios in a way that foster reduced business costs. In this multi-method study, we drew on documents, parliamentary records, and in-depth interviews to gain an understanding of conditions surrounding workers’ compensation retirement pensions for injured workers and how injured workers experienced these pensions. Our data gathering took place from 2019 to 2022.

Our document analysis focused on freely available records describing workers’ compensation old age pensions across Canadian provinces and territories. Our search included legal documents, workers’ compensation documents for employers and workers, and media reports. We used the Google search function and key words such as ‘workers’ compensation pension’ and ‘workers’ compensation annuities’. This search yielded over 50 websites and documents.

To gain an understanding of the logic supporting reductions in injured worker retirement benefits in Ontario, we examined Hansard Records, which are the official reports of what was said in the Government of Ontario Legislative Assembly. We considered records from 1995 and 1996 that included word-for-word transcriptions of arguments advanced by interested parties during the debating of the bills to reduce injured worker’s retirement pension benefits. The relevant Bills were Bill 15, Workers’ Compensation and Occupational Health and Safety Amendment Act, 1995 (Ontario Legislative Assembly 1995) and Bill 99, Workers’ Compensation Reform Act, 1996 (Ontario Legislative Assembly 1996). During debates of Bill 15, no changes were made to WCB benefits, but rhetoric about benefit affordability was prominent. Bill 99 passed 1 year later and reduced both income support benefits and retirement benefits for injured workers.

Finally, to understand injured workers’ experiences of Ontario workers’ compensation pensions, we conducted semi-structured, in-depth interviews with workers who had been receiving workers’ compensation benefits for at least 5 years with a claim starting 1998 or later (to capture experience with current pensions legislation) and with key informants with knowledge of workers’ compensation retirement pensions. These included workers’ compensation policymakers, legal experts, and injured worker advocates. We recruited workers by posting an ad on social media (Kijiji) and asking selected legal aid clinics that help workers with long-term workers’ compensation claims to post our recruitment poster. For both workers and key informants, we approached known contacts and used the snowball referral method, where one person recommends another. Between 2019 and 2022, we interviewed 13 workers and 6 key informants (see Table 1 and 2).

Table 1. Injured worker sample

Table 2. Key informant sample

Workers were paid a $50 honorarium to thank them for their time. Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Using NVivo for data organisation, we applied codes to transcripts and subsequently exported coded excerpts of text. Our 16 codes drew out data on WCB policies and programmes, claims, and workers’ employment and health circumstances. Ethical approval for this study was provided by the University of Waterloo Office of Research Ethics. All interview participants were assured of anonymity and confidentiality. To blur the identities of key informants, we refer only to a general sector, such as ‘Ontario Government Organisation’. All injured worker and key informant names used are pseudonyms, while actual names are used from the publicly available Hansard parliamentary records.

Our three data gathering methods of documents, parliamentary records, and in-depth interviews provided analytic synergy. For instance, issues raised by workers in interviews and in Hansard data prompted further document analysis. Likewise, documents and Hansard data prompted interview questions. Across the three data sets, we compared and contrasted descriptions, discourses, and rationales.

Policies related to retirement income for injured workers

Retirement income for Canadians is built up through a three-pillar system (Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada 2020; Financial Consumer Agency of Canada 2021). The first pillar has a poverty reduction function and is composed of public benefits. These benefits are monthly Old Age Security and Guaranteed Income Supplements, provided to those with low incomes. For instance, a single older person is eligible for a supplement if their annual pension income falls below approximately $20,000 yearly (Government of Canada 2022). The second pillar, and a key focus for this paper, is a public national contributory pension scheme. This is the CPP,Footnote 1 which provides monthly payments to people who contributed to the plan during their working years. The amount received by this plan depends on how long an individual contributed to the plan and how much was contributed. The third pillar consists of voluntary pension schemes, including employer-sponsored pension plans and personal savings and investments. In 2021, only 38% of workers had a registered pension plan established by an employer or union (Statistics Canada 2022a). Employer-sponsored plans tend to be offered to workers in full-time, permanent jobs; the growing numbers of workers in low-wage and non-standard work tend not to have employer-provided pension plans (Mitchell and Murray Reference Mitchell and Murray2017). Workers without an employer-sponsored pension plan can voluntarily invest in a Registered Retirement Savings Plan (RRSP) or Tax-Free Savings Account, which each provide tax breaks on the income (Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada 2020). However, reduced income reduces the ability of injured workers to set aside money.

When a worker becomes injured or ill as a result of their work and is in receipt of workers’ compensation benefits, and if their employer provided an employer-sponsored pension plan, the employer is required to continue paying into it for 1 year after the start of the workers’ compensation benefits. However, employers are not required to contribute to the CPP at any time while the worker is receiving workers’ compensation benefits. This is because CPP contributions can only be paid on taxable income and Ontario workers’ compensation benefits are not taxable (Workplace Safety and Insurance Board 2023). Essentially, Ontario injured workers on workers’ compensation benefits lose all CPP pension contributions for their years on WCB benefits. Their years on workers’ compensation benefits count as zero contribution to CPP, creating a gap that deflates their lifetime average wage that is used for the CPP benefit calculation.Footnote 2

In lieu of CPP contributions, workers on workers’ compensation benefits are provided with retirement pension contributions to a workers’ compensation board fund, called the Loss of Retirement Income fund (WSIB Ontario 2021).The founding philosophy for Ontario’s Loss of Retirement Income fund (hereafter called by the generic term, retirement pension for injured workers), as laid out in the Weiler Report (Weiler Reference Weiler1980, p. 41) and the Ontario Workplace Safety and Insurance Appeals Tribunal (Workplace Safety and Insurance Appeals Tribunal 2013), is that the workers’ compensation board, as the last insurer for injured workers, should make up any income losses related to workers’ loss of contributions to the CPP. This founding philosophy reflects the ‘no fault’ foundation of workers’ compensation benefits. In the context of a no-fault workers’ compensation insurance that absolves employers of tort liability for workplace accidents and illness, workers’ compensation is intended to provide income support benefits to workers while they are unable to work due to illness or injury. WCB benefits are intended to replace the income lost as a result of the injury, with the recognition that the workers cannot sue the employer for creating dangerous or adverse working conditions (Association of Workers’ Compensation Boards of Canada 2013).

With the enactment of Bill 99 in 1998, injured workers faced reductions to their regular benefits and significant reductions to their retirement benefits. Up to 1997, the WCB contributed an amount equivalent to a full 10% of the workers’ net benefits yearly to the retirement pension for injured workers and calculated income support benefits at 90% of net income. As of 1998, the WCB contribution to the retirement pension for injured workers has been only 5% of the workers’ net benefits, and income support benefits are calculated at only 85% of net income. WSIB more than halved the amount they contributed to injured worker’s retirement pensions. Since 1998, workers have been provided with the option to voluntarily contribute an additional 5% out of their own pocket to the retirement pension for injured workers, to create a total 10% contribution to the injured worker retirement pension fund. They are provided with a brief window of time (a few months) to make this decision about the extra 5% contribution, and it is a decision that is irrevocable. In contrast to the current injured worker retirement pension system, the pre-1998 WCB contribution of 10% had recognised the WCB’s responsibility to provide an amount equivalent to both employers and employees CPP contributions, compensating for the fact that workers on compensation benefits are without employment earnings. Our documentary analysis found that workers’ compensation boards for other provinces across Canada (except for Northwest Territories and Nunavut) have made retirement pension cuts in the 1990s and 2000s. Similar to Ontario, they have resulted in injured worker retirement pension payments that are about half of what they were in the 1990s (Association of Workers’ Compensation Boards of Canada 2015).

A key problem with the retirement pension for injured workers is that the workers’ compensation retirement fund now provides strikingly lower support than CPP benefits, making retirement years particularly economically precarious for injured workers. The amount provided by the WCB retirement pension is now far less than what workers would have received if they had been making contributions to the CPP. When Ontario workers are unable to work because of a work-related illness or accident and approved for workers’ compensation, the WCB begins paying loss of income and healthcare benefits starting from the first day of work absence. At that point, WCB calculates the workers’ ‘loss of earnings’ and the worker is paid income support benefits (up to a ceiling) equivalent to 85% of their net earnings during working age years, up to age 65. To arrive at these net earnings, the WCB deducts workers’ social security contributions, including a worker’s probable contributions to CPP. The WCB calculations ignore the loss of employer-sponsored pension plans after 12 months on benefits. These are not calculated in net earnings, therefore depriving the worker of compensation for the resulting reduction in the size of the employer-sponsored pension.

The logic behind injured workers being paid only 85% of their net salary is ‘moral hazard’, or the idea that workers need a financial incentive, or some degree of financial hardship, to be motivated to return-to-work (Butler and Worrall Reference Butler and Worrall1991; Dembe and Boden Reference Dembe and Boden2000; MacEachen Ferrier et al Reference MacEachen, Ferrier, Kosny and Chambers2007). The notion that financial hardship created by a lowered income may compound the workers’ health situation at a time of injury or illness is not considered within this economic model (Dembe and Boden Reference Dembe and Boden2000; MacEachen Ferrier et al Reference MacEachen, Ferrier, Kosny and Chambers2007).

Not surprisingly, very few Ontario workers contribute the voluntary extra 5% payment to the injured worker retirement pension fund. According to WCB reports, only 13% of workers on injured worker retirement pensions opted to make this voluntary contribution in 2021 (WSIB 2021). We suggest that this lack of worker participation is because, when on WCB benefits, workers are living on benefits that provide only 85% of the former net income, and so they have already experienced a reduction in income. They are likely experiencing financial hardship with respect to keeping up with expenses that had been geared to their pre-injury income, such as rent, mortgages, and car payments (Paulk Reference Paulk2007; MacEachen et al Reference MacEachen, Kosny, Ferrier and Chambers2010; Ballantyne et al Reference Ballantyne, Casey, O’Hagan and Vienneau2016). Additionally, disability brings with it extra expenses, such as when workers have to hire people to do activities that they would formerly have managed on their own, such as shovelling snow from the driveway (MacEachen Kosny et al Reference MacEachen, Kosny and Ferrier2007; Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada 2020).

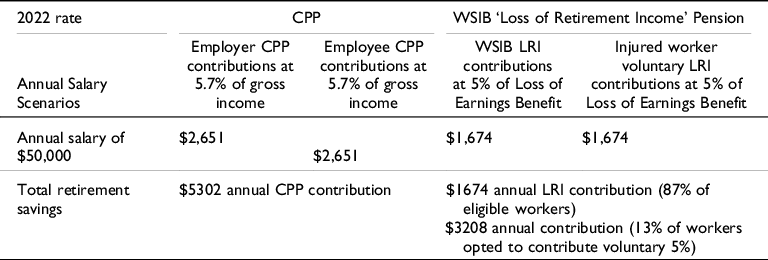

It is worth emphasising that the WCB’s calculations of workers’ retirement pensions are based on net benefits income. This is in contrast to the CPP arrangement that calculates workers’ benefits based on their gross salary and at a higher rate (the 2022 rate was 11.4% for both worker and employer contributions).

Ultimately, as laid out in Table 3, the WSIB ‘Loss of Retirement Income’ Pension (excluding the voluntary worker contribution) for a worker earning $50,000 is less than half of the retirement contributions that the worker would have contributed through the CPP plan. The salary of $50,000 used for this example is similar to the Ontario mean income in 2021, which was $53,400 (Statistics Canada 2023a).

Table 3. Comparison of CPP and WCB LRI retirement pensions

It is important to note that pension savings for CPP and WCB diverged for injured workers with wages over $61,400. This is because CPP contributions were capped at that amount in 2022 (Canada Revenue Agency 2023), while the maximum insurable earnings for WCB claimants that year were higher, at $100,422 (WSIB 2023). It is unclear how many injured workers earned the higher salaries and benefited from this divergence as we were unable to locate statistics on pre-injury salaries of Ontario injured workers. However, skilled construction workers are likely in this situation (Job Bank 2023). Other workers with high incomes tend to work in office-based jobs, which produce relatively few occupational injuries (Statistics Canada 2023b).

Other important differences are defined benefits and the format in which pension funds are paid out at age 65. CPP provides defined benefits while the retirement pension for injured workers is a defined contribution fund. That means that CPP recipients know exactly what benefits they will receive based on their contributions, but injured workers receive only the amount earned by the trust in which their contribution was placed. If the trust performs well, then they should have a good pension return. If it performs poorly, their pension amount is lower. As the WCB’s trust (called the WISE Trust) explains: ‘You assume all of the investment risks as well as rewards. Your retirement income will depend on how well your investments perform and the interest rates in effect when you convert your investments into retirement income’ (WISE Trust 2023). In all, the WCB’s injured worker retirement pension is more uncertain than a CPP pension.

A further difference between CPP and the retirement pension for injured workers is how pension funds are paid out. While the CPP provides a monthly benefit, the WCB pays out almost all injured worker retirement pension benefits in a lump sum (WSIB Ontario 2021). Lump-sum benefits have several disadvantages. A key problem is that the benefits are taxable and the sudden financial input can temporarily place an injured worker into a punitively higher tax bracket (Pension Solutions Canada 2023). A second problem is that the relatively high income in the year in which the lump sum is paid out often removes injured worker’s eligibility for low-income supports that they may have been receiving. They can lose access to services including rent-geared-to income housing, free prescription drugs (e.g., Trillium Drug Plan), and old age security payments (e.g., Guaranteed Income Supplements). Loss of access to these supports is disruptive to injured workers’ lives. When the lump sum is quickly spent (e.g., to pay off debts), workers are obliged to re-apply or re-start applications and can face lengthy waits for programmatic supports for which they had already qualified before they turned 65.

In sum, although the founding philosophy for workers’ compensation board retirement income policy was to make up any income losses related to workers’ loss of contributions to the federal pension fund, we observe that the injured workers’ retirement pension pays less than half of the amount paid by CPP. Furthermore, this late 1980s/1990s trend is observable across WCB injured worker retirement pensions in almost all Canadian provinces. These changes appear to reflect a shift across Canada in attitudes about state responsibility for older injured workers.

Rationales put forward to reduce injured worker pensions

Our analysis of parliamentary records for the two pieces of legislation that provided arguments for reduced retirement pensions for injured workers identified three key rationales provided by proponents of the reduced pension plan: excess business costs, overcompensation, and fiscal responsibility. Each is described below, together with a counter-narrative focused on the original principles of workers’ compensation.

The dominant argument put forward to significantly reduce injured worker WCB pensions was that the payments were too costly for businesses. Workers’ compensation agencies manage a mandatory, collective liability system that is compulsory for employers and workers. Within a ‘no fault’ system in which employers and workers relinquish their right to sue each other, the agencies are funded through employer premium payments. With the experience-rating of workers’ compensation premiums, a plan introduced in 1984 that was intended to increase employer accountability for workplace illness and accidents, payments for injured worker retirement benefits became an expensive part of the overall claim cost to the employer (Rixon Reference Rixon2010). The experience-rating plan generated generous premium refunds and hefty surcharges based on employer’s accident cost experience relative to their sector, prompting employers to be very sensitive to these costs (Mansfield et al Reference Mansfield, MacEachen, Tompa, Kalcevich, Endicott and Yeung2012). For this premium cost reason, the Canadian Federation of Independent Businesses advocated for introducing a ‘waiting period’ before workers became eligible for WCB contributions to their injured worker retirement pension (Legislative Assembly of Ontario 1995). Indeed, our scan of information provided by WCBs across Canada shows that we now see waiting periods of 12–24 months before workers’ compensation boards begin making contributions to injured worker pension plans.

Overcompensation was a second argument put forward during the hearings. The Canadian Federation of Independent Businesses argued that injured workers were ‘overcompensated’ with the WCB injured worker retirement benefit when it was 10% of benefits:

We recommend … revisiting the … retirement pension issue, scaling back the future economic loss awards that have turned out to be far more costly than even the most generous costings …. Our mandate … shows 81% of our [small business owner] members in favour of such a waiting period’. (Canadian Federation of Independent Businesses, emphasis added)

Similarly, a business sector representative described WCB retirement pensions for injured workers as ‘overcompensation’ because some workers may not have had a job that provided an employer-sponsored pension plan (which would be in addition to CPP payments) at the time when they were injured:

It continues to be our view that this provision may contribute to overcompensation by providing a benefit which may not have existed prior to the [workplace] accident. Although such benefits would be appropriate in cases where a pension plan formed part of the employment benefits, they would be inappropriately extended where no such benefits existed prior to the accident. (Rosa Fiorentino, chair of Alliance of Manufacturers and Exporters Canada workers’ compensation committee)

This business sector representative perhaps deliberately confused job-provided retirement pensions (e.g., company retirement plan) with CPP pension contributions. The former is a perk, while the latter is a statutory deduction required by law from all employers for each worker paycheque.

This business discourse about overcompensation is surprising given the financial reality that workers receiving workers’ compensation benefits are significantly worse off than before their injuries. Even the 10% of benefits contributed by the WCB up to 1997 was significantly less than equivalent CPP contributions, which are based on the workers gross wage not on the WCB amount of 85% of net wages.

A third key argument for reducing injured workers retirement pensions was fiscal responsibility. A provincial member of parliament with the Progressive Conservative Party, who were in power at the time, emphasised the fiscal responsibility of the workers’ compensation board and their duty to rein in costs and address the ‘unfunded liability’ of the board:

WCB investment revenue increased by $118 million in 1996 to $711 million, compared to $593 million in 1995. Administrative and other expenses decreased by $18 million in 1996. This decrease was the direct result of management initiatives to control salary and other administrative costs. […]. These results clearly indicate that the WCB continues to strive towards financial sustainability and that the WCB is fully aware of the financial challenges that remain ahead, given an unfunded liability which now stands at $10.4 billion compared to $10.9 billion in 1995’. (MPP Bart Maves)

The WCB describes the unfunded liability as ‘the shortfall between the money needed to pay future benefits and the money in our insurance fund’ (WSIB 2018).

Another conservative provincial member of government invoked the image of a bloated welfare state, which is a key tenet of neoliberal discourse that emphasises market-oriented reform policies (McKinlay Reference McKinlay, McKinlay and Pezet2017). This member of parliament dramatically suggested that the workers’ compensation board would collapse if costs were not further reduced:

If we do not get our costs under control, there will not be a viable, self-sustaining WCB … to deal with future injured workers. (MPP John Hastings)

During the debating of Bills 15 and 99, worker advocates struggled to draw the focus back to the basic principles of workers’ compensation, as per the following example:

The important thing to remember is that injured workers do not disappear when they are wrongfully cut off workers’ compensation. They’re forced on to [social benefits including] Welfare, EI, Canada Pension Plan Disability. Their lives and the lives of their families are often irreparably damaged. From our recent experience, the culture shift at the Workers’ Compensation Board … is essentially a shift away from the basic principles of workers’ compensation”. (Ian Aitken, Brant County Community Legal Clinic)

A labour leader drew attention to old age pensions as a resource for workers at a particularly vulnerable time of life and described the proposed reductions as a ‘grab’ from injured workers.

Before the bill, 10% of every FEL award was set aside for purposes of [retirement] pension. This government will cut this to 5%. These funds were for a time of life that is most vulnerable. Bill 99 is not about compensation. This is about poor insurance. This is a cheap, demeaning grab from the injured workers. This is theft …. You have taken away 5% of the injured worker’s temporary accident benefit, 5% of their FEL award for pension…. (John Cunningham, Waterloo Regional Labour Council)

In all, legislative debates about the bills that ultimately cut injured workers retirement pensions in half, by reducing WCB contributions from 10% to 5% of injured workers’ benefits in 1998, centred on neoliberal logic of ‘overcompensation’ and ‘fiscal responsibility’. Injured worker advocate calls for lawmakers to observe the principles of workers’ compensation were ineffective in avoiding the reduced injured worker retirement benefits.

The effect of reduced retirement pensions

Our interviews with injured workers on long-term workers’ compensation benefits, and with key informants, provided some insight into implementation of workers’ compensation retirement pension policy. Key topics for participants were 1) the post-1998 change that required workers to self-fund 5% of their pension if they wanted the total contribution to remain at 10% of their benefits; 2) workers’ concern about the insecurity of their ‘defined benefit’ pensions, and 3) workers’ experiences of poverty in older age.

Being asked to self-fund 5% of the pension contribution

Knowing that only 13% of workers contribute the extra 5% to their WCB pensions, we asked workers and key informants about whether workers had made this contribution and why or why not. Unsurprisingly, we found that many workers simply could not afford it:

The people who come to our [community] legal clinic for help are people who are having difficulty with the system because they’re undercompensated, so it’s rare that someone would offer to make an additional voluntary contribution, because they don’t have enough money coming in to live on. (Evander, Ontario community legal clinic lawyer)

An injured worker explained how his difficult financial situation precluded paying 5% to the WCB to increase his future WCB pension fund payout:

They [WCB] are going to put that 5% into my account which was the Loss of Retirement Income. And they asked me … if I want to deposit another 5% from the little money that I was just given, but I opted ‘no’ because I was so in debt that I had to pay my credit card. I also will pay some people back. I borrowed money from when I was trying to get cheque from my injury. (Alejandro, age 55)

Another injured worker explained the unaffordability of the extra 5% and also the lack of decision-making support provided to workers about whether to make these additional pension contributions:

I … received a letter in the mail. They send a letter. Not your caseworker explaining anything to you, just the letter that gives you the option that [WCB] will pay this 5%, you know, out of your cheque, and you can contribute toward it if you want to. And I guess at that point, I mean, I was already living on less money. I’m single and support myself in a little home. And so, I felt that I can’t afford to take any money out of. So, I didn’t opt into it, and it was a one-time offer. So, there was nobody to ask what it really was. (Paula, age 70)

The actual workings of pension funds, including that workers only have a one-time offer, were murky even to a senior administrator. A very experienced manager within the Ontario government was surprised by the rigidity of the contribution structure of the retirement pension for injured workers, noting that the brief window afforded to injured workers to make an irrevocable decision about contributing an extra 5% to the pension fund did not seem fair:

I’m surprised that, once you make the decision, that it’s irrevocable. Because circumstances can change, right? Yeah, I CAN imagine that they wouldn’t like workers to be doing it randomly, depending on from payment date to payment date, whether or not they felt they could afford it. So, some sort of protocols wrapped around that would make sense to me. But to say you have to decide by such and such a date, whether you’re in or out. And if you’re in, you’re in forever, and I guess if you’re out, you’re out forever, I- that wouldn’t make sense to me. (William, KI, Ontario Government Organisation)

An important contextual issue is that, when workers are asked about whether they want to provide a self-funded 5% contribution, it is at a point in time when they may still be thinking that they can return to work. As such, they would normally lack information to allow them to anticipate whether they will be relying on the worker’ compensation retirements for a significant period of time.

Defined contribution benefits

An important difference between the WCB injured worker pension fund and the CPP, which it was intended to replace, is that the CPP provides a ‘defined’ (guaranteed) benefit, while the WCB injured worker pension fund does not. Instead, the WCB pension is derived from a fund that pays out varying amounts dependent on success of the fund’s earnings. Workers interviewed for this study described feeling a loss of income security with this fund. As described by a key informant, workers worried that the amount paid out to them in their retirement years was subject to the performance of the fund in changing market circumstances:

That feeling of loss of control and uncertainty … could foreseeably be compounded then by looking at their retirement benefit where it’s, it’s not even a fixed amount anymore. It’s all subject to … how your money’s being managed by the private company and also where the market takes it. So, whereas a [CPP] benefit is a relied upon amount that folks can … count on, but the LRI [Loss of Retirement Income pension] piece, they know how much is being invested every month, but they don’t know how much they’re going to get out of it. And then being so many years down the road, at age 65 for some, that could—the uncertainty could be even more compounded I could foresee, in the retirement years. (Dave, KI, Injured Worker Advocate)

Poverty in old age

The prospect of poverty in old age dominated our interviews. Workers interviewed described trying to live frugally within the formal limits of their small pension incomes. The following worker, who was approaching age 65 when her monthly WCB benefits would end and be replaced by a retirement pension for injured workers lump-sum benefit, expressed her concern about her financial future:

It’s very hard to live a precarious existence. … constant financial stress, right? Never having enough or, you know, having to wait for a check to come in to pay what I can pay and not having a proper income, you know, not having enough to pay to live. I mean, I’m a very frugal person. But even still, you know, things are very expensive, phone bills are expensive, and cost of living is expensive. Rent is the biggest issue. … I don’t know how I’m going to survive. I really don’t. I’m just hoping that … things will improve. But they haven’t improved, you know. (Catherine, age 58)

Similarly, other injured workers described facing a dark future, which was not ‘the golden years’:

So, if you’re not contributing [to CPP], you’re going to be affected at age 65 when you can no longer apply for ODSP [welfare disability benefits] or Welfare yet have to take whatever CPP you’re given. And that’s what you get to live on. You have no pension plans or savings to fall back on. … When they reach age 65, it’s not going to be the golden years. (Robert, age 63)

Just my hospital pension plan [from former job] which is not enough. My retirement is not enough. I don’t know, how can I get money? I don’t have a house. I don’t have a good income. I don’t know how will I live. I don’t know. I told you, I’ll just leave it to fate. (Martina, age 61)

Minimal contributions to a CPP fund were an important reality for a relatively young worker, aged 36, who had been on WCB benefits for 10 years. Due to her permanent injury, she anticipated many more years on WCB benefits. Knowing that the WCB injured worker pension was meagre and paid much less than what she would have had with the CPP pension, she simply hoped that she would not live long after the age of retirement:

The LRI, the Loss of Retirement Income [pension] that you get … If you were any other normal working person, and you put away RRSPs [savings], then at age 65, you would start pulling that out, because you wouldn’t have a paycheque anymore. But I’m just kind of worried I’m not going to have enough in there. So, in my own LRI benefits …, who knows what if I still live another 30 years? I hope not after 65, but who knows? (Lina, age 36)

The disheartening wish to not live long on the dismal conditions of the WCB’s meagre injured worker retirement pension was also expressed by another worker interviewed:

[After my work-related injury] I lost my home. I ended up divorced because I couldn’t support anything, really. And it’s been very, very difficult. Every day is a struggle. I’m lucky I’m not homeless; at one point I was. So financially, it’s been a total nightmare. And I don’t see any change in that in sight. But I mean, the law requires [WCB] to terminate my benefits at age 65…. I see a lot of pain and a lot of heartache. I really have very little hope for, for what I’m assuming is going to be a relatively short future. Because you can’t go through this kind of … stress and hardship without it having a major impact on you. So, I’m always stressed out, I mean, so much so, that my blood pressure is through the roof, I suffer from hypertension now. And I really don’t see much of a prospect for the future at all. (Lewis, age 68)

In all, injured workers and key informants in this study expressed trepidation about injured workers’ financial futures. In a province where home ownership rates are relatively high, at 68% in 2021 (Statistics Canada 2022a), injured workers on persistently low incomes would likely be among those not owning a home and struggling with rent. Most workers interviewed could not afford to self-fund 5% of the WCB pension contribution to keep it at the pre-1998 10% contribution level. This meant that at age 65 their workers’ compensation-related pension would be extremely low. The logic of an administrative approach of allowing workers a one-time decision about the extra 5% contribution seemed flawed, even to a key administrator. Some workers interviewed had a dark view of their future, one that now excluded the WCB’s no-fault insurance ideal of replacing the CPP retirement income lost as a result of the injury, with the recognition that the workers cannot sue the employer for creating dangerous or adverse working conditions (Association of Workers’ Compensation Boards of Canada 2013).

Discussion

This study addressed the question of what happens to workers during retirement age when, during working years, they have been receiving workers’ compensation benefits. We were concerned with how injured workers survive financially in pension age. By examining administrative details and Hansard records, as well as conducting interviews with injured workers and key informants, we explored the political and economic conditions of workers’ compensation that led to poverty in older age for injured workers. While a great deal of research has been conducted about injured workers in relation to return-to-work (MacEachen et al Reference MacEachen, Clarke, Franche and Irvin2006; Cancelliere et al Reference Cancelliere, Donovan, Stochkendahl, Biscardi, Ammendolia, Myburgh and Cassidy2016; Cullen et al Reference Cullen, Irvin, Collie, Clay, Gensby, Jennings, Hogg-Johnson, Kristman, Laberge, McKenzie, Newnam, Palagyi, Ruseckaite, Sheppard, Shourie, Steenstra, Van Eerd and Amick2017; MacEachen et al Reference MacEachen, McDonald, Neiterman, McKnight, Malachowski, Crouch, Varatharajan, Dali and Giau2020), to date we have not explored what happens to injured workers when they reach retirement age. This knowledge gap is problematic given the growing aging populations across advanced economy countries.

Policymakers and business stakeholders defending the pension reduction in Ontario rationalised this change on the basis of fiscal responsibility and financial scarcity. Although workers’ compensation systems are fundamentally based on the logic that the risks of selling one’s labour within a capitalist system require a social and protective response, neoliberal logic that gained currency in the 1990s has instead emphasised individual choice, free markets, and deregulation (Whelan Reference Whelan2021). This way of thinking highlights resource scarcity and a reduction of individual reliance on the welfare state (McBride Reference McBride2016; Wright and Patrick Reference Wright and Patrick2019). In relation to work injury and workers’ compensation benefits, ‘activation theories’ promoted workers’ active participation in recovery through return-to-work before full recovery (Oorschot Reference Oorschot2002; OECD 2013; Martin Reference Martin2015; MacEachen Reference MacEachen and MacEachen2018). In relation to post-working years past the age of 65, we see that neoliberal influences have again shaped policies, with Ontario injured workers expected to actively self-fund half of their pension contributions in order to keep their pension at a level that is even comparable to the CPP fund. At the same time, a relative lack of representation by unions or other support groups among workers on WCB benefits may have facilitated WCBs across Canada to dramatically reduce injured worker pensions across Canada with essentially no media or scholarly attention.

Workers’ compensation boards internationally have been moving toward a form of lump-sum payments as a way of managing costs, but this payment approach does little to favour workers. Australian workers’ compensation reforms in 1987 introduced lump-sum benefit payments (O’Laughlin Reference O’Laughlin2005), and lump-sum payouts are common in the USA (Hunt and Barth Reference Hunt and Barth2010). As outlined by Hunt and Barth (Reference Hunt and Barth2010), lump-sum payments are financially and administratively beneficial to workers’ compensation systems. They reduce insurer’s administrative costs in several ways: it is expensive to keep a claim open, it reduces the insurer’s uncertainty about payout costs, insurers may be able to settle a claim for less than it would cost otherwise, and it removes costs related to disputes. Indeed, a 1993 analysis of New York claims found that claimants were settling for lump sums that were significantly less than they could have expected to receive through adjudication (Thomason and Burton Reference Thomason and Burton1993). Lump-sum systems do little to favour injured workers and the odds are stacked against them because even the lawyers representing them are incentivised to encourage this approach. As noted by Hunt and Barth (Reference Hunt and Barth2010), lawyers are financially incentivised by the immediate payment of lump-sum arrangements as they usually get a proportion of the payout.

A general shift from defined benefit pensions (here, the CPP approach) to defined contribution pensions (here, the retirement pension for injured workers approach) has been striking in advanced economies. The reasons underlying the shift are very similar to those advanced above regarding lump-sum pension payments. Essentially, they are less costly to employers and easier for them to administrate (Congressional Research Service 2021). Additionally, defined benefit pensions are described as convenient to employees because they are portable. What seems lost in this approach to pensions is that defined contribution approaches shift risk to workers. Under defined contribution schemes, the build-up of retirement savings depends more directly on the performance of markets and ultimately on the performance of the economy. Therefore, individual retirement savings become more uncertain, and retirement incomes are more unequally distributed (Rousová et al Reference Rousová, Ghiselli, Ghio and Mosk2021).

The discourse of welfare state leanness appeared in a particularly harsh light when Ontario’s WCB announced in 2018 that its own period of ‘unfunded liability’-related austerity was over and that they had such a great surplus that they would slash employers premiums by 30% (Mojtehhedzadeh Reference Mojtehhedzadeh2018). A $1.5 billion rebate to employers of approximately 30% of their annual premium payments was enacted in 2022 (Province of Ontario 2022). The Ontario WCB chair lauded their achievement of having Ontario employers paying the lowest premium rates in more than 20 years (Government of Ontario 2021; Province of Ontario 2022). While the Hansard parliamentary records shared in this paper show the ‘unfunded liability’ faced by Ontario’s WCB being discussed as early as 1998, this concept was heavily reinforced in 2009 by the province’s auditor general warning of this risk (Workplace Safety and Insurance Board 2019). Meanwhile, worker advocates called the unfunded liability a ‘manufactured crisis’ because, while private insurance companies are prohibited from having an unfunded liability in the event that they go bankrupt, Ontario’s WCBs did not face this risk as it had a legally guaranteed revenue source in the form of employer premiums (Wilken Reference Wilken1998; King Reference King2014; Mojtehhedzadeh Reference Mojtehhedzadeh2018). In any case, as soon as Ontario’s WCB cut their retirement pension for injured workers contributions in half, from 10% to 5%, they began saving large amounts of money annually. For instance, according to the WCB’s 2021 annual report, their costs would have been $55 million higher in 2021 if they had contributed a full 10% to the injured worker retirement fund (Workplace Safety and Insurance Board 2022). It is unfortunate for workers, and also revealing of Ontario WCB’s financial priorities, that the 2018 financial surplus was not allocated towards a restoration of injured worker retirement pensions. At the end of the day, this has created cost-shifting from employers to citizens as older injured workers are inadequately supported by their pensions provided by the WCB and instead draw on other social supports, such as rent-geared-to income housing and Guaranteed Income Supplements.

This analysis has some strengths in the multiple data sources provided analytic synergy and depth. Each data set prompted enquiries of the other data sets. Limitations exist in that the analysis is focused mostly on Ontario. We have determined that WCB pensions were reduced across Canadian provinces, which are each administrated by separate workers’ compensation boards, but we do not know if this phenomenon also occurred in other advanced economies. More investigation is also needed regarding the knock-on effects of pension reductions: who picks up the costs and how the reductions affect health and lifespan. This paper serves the modest goal of bringing attention to and opening discussion about cuts to injured worker retirement pensions and their poverty in retirement age.

Conclusion

This paper has focused on poverty during pension age among injured workers who have had long-term workers’ compensation claims and how their retirement age pensions decreased amidst neoliberal discourses about affordability and responsible administration of funds. A striking aspect of this pension reduction has been the quietness of it – it has not received media or scholarly attention. At the same time, this quietness should not be surprising when considering Foucault’s explanations of how power is hidden in administrative details and operates discreetly (McKinlay et al Reference McKinlay, Carter and Pezet2012). A political amnesia about the fundamental aims of workers’ compensation has also been present in debates about injured worker entitlements. It seems forgotten that workers’ compensation boards were established in recognition of risks associated with work, and that the workers’ compensation board, as the last insurer for injured workers, should make up any income losses faced by workers, including retirement pension income losses. This paper serves to bring the issue to the surface, inviting scholarly engagement with the issue of workers’ compensation administrative changes and the lasting harsh economic consequences for injured workers.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Nicole Carleton for her early work as a researcher on this study. We also thank John McKinnon, Orlando Buonastella, and David Newberry at the Injured Workers Outreach Legal Clinic as well as Steve Mantis and other members of the Ontario Network of Injured Worker Groups for discussions related to injured workers in retirement age. We thank the Ontario injured workers and key informants who agreed to be interviewed and shared their experiences and insights with us. Finally, we are grateful to the peer reviewers of this manuscript for their helpful comments and insights.

Ellen MacEachen is a Professor and Director in the School of Public Health Sciences at the University of Waterloo. Her research focuses on the changing nature of work and the social and economic factors that shape workers’ experiences of occupational health and safety, disability management, and workers’ compensation systems.

Pamela Hopwood is a PhD candidate in the School of Public Health Sciences at the University of Waterloo. Her research interests include precarious work, occupational health and social welfare policy.

Meghan K. Crouch recently completed her PhD in the School of Health Sciences at the University of Waterloo. Her research focuses on the changing nature of work and the impacts on health, wellbeing, and sustainability of the workforce.