Introduction

Throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, hundreds of millions of postcards circulated between Algeria and France, many of which featured photographs, paintings, and drawings of musicians, musical instruments, and performances of music. At a time when there were few opportunities for French citizens to hear Algerian music, these mass-produced images offered a rare chance for those living on the French mainland to encounter Algerian culture. Such postcard imagery was shaped, perhaps inevitably, by the exotic otherness that the French (and wider European) colonial project imagined to be characteristic of North Africa, and many of these images served to reify racial, religious, and cultural stereotyping in the minds of Europeans. However, as I argue in this article, these postcards did more than simply reinforce existing prejudices and served to reflect the role of music and sound within colonial Algeria and Metropolitan France, creating a visually inscribed sonic legacy that extended beyond the period of French rule (1830–1962).

While postcards might initially appear innocuous objects and curious sources for musicological scholarship, I suggest that they offer one way of understanding the intersection of visual and sonic culture in the early twentieth century. They act as important historical objects that enable us to see how non-European cultures were represented by the colonial system and the ways in which both music and sound were depicted visually. As such, they contribute to a much longer history of music's visual representation, and, as Tim Shephard and Anne Leonard note, ‘music and the visual have always participated together (if not always in coordination) within the same lived experiences, and the same historical realities, at the most practical level’.Footnote 1 While devoid of sonic elements, static visual objects are therefore able to depict musicians and music-making at a particular moment in time, while simultaneously representing the broader political and social power structures that existed. Susan Boynton, writing about musical iconography in medieval Europe, underscores the importance of understanding visual depictions of music within their wider context, arguing that ‘visual representations of music often employ symbolism that conveys a range of extramusical meanings’.Footnote 2 My intention in this article is to begin understanding and interpreting the types of symbolism found within colonial-era photographic depictions of music and musicians.

A degree of caution is certainly necessary in dealing with such a historical archive. It is difficult to ascertain how many images, particularly those printed on postcards, have survived the passage of time, and my own personal collection is clearly not comprehensive. Furthermore, these images were rendered within a colonial apparatus that had specific aims, not least to express Franco-European cultural superiority and control the ways in which non-European citizens living in Algeria were depicted. Nevertheless, they provide a rare opportunity to understand portrayals of music and sound during the period of colonial rule in Algeria, and this article aims to critically assess their influence at the time.

As a relatively new technology at the start of the twentieth century, photography was generally accepted as representing visual ‘truth’, as opposed to the artistic licence that painting and sculpture afforded. The photographs that appeared on these postcards were most likely to have been understood as accurate depictions of musical life in colonial Algeria. However, many of the photographs that appeared on these postcards were carefully posed and reinforced established stereotypes of Algeria and Algerians, aiming to represent an entire culture within a single framed shot. David Prochaska suggests that such images were ‘clearly made rather than “taken”’, and as such, were as much a form of fiction as an attempt to represent reality.Footnote 3 Furthermore, they were a form of fiction constructed and mediated by the French colonial authorities and European settler sections of society, reflecting not only cultural exoticism but also the more political aspects of French rule, including command of cultural production and the use of public space in Algerian towns and cities. This article contributes to a small but significant body of scholarly literature that seeks to understand music and sound within the context of French-ruled Algeria, as well as the role that auditory culture played in reflecting and shaping colonial Algerian society at the time.Footnote 4

Music, image, and synaesthesia

Algeria was ruled as a French colony for 132 years, during which time musical traditions were reified and preserved and new forms of musical expression emerged within an increasingly cosmopolitan society. Both people and objects moved relatively freely across the Mediterranean, connecting North Africa and Europe and shaping public awareness of Algerian culture in France, and vice versa. As the colonial authority, France held the greater power in terms of representation, and both French industry and the media played an important role in shaping the ways in which French citizens understood Algeria and its musics. It is these French citizens (both residents in the metropole and those of European birth or ancestry living in Algeria) that form the focus of this article as, I argue, they were the intended audience for these postcards. While Muslim and Jewish Algerian citizens did occasionally become involved in the postcard industry, forming local publishing businesses, every postcard containing a handwritten message that I have encountered is written in either French or English.

However, we might comprehend the role of these postcard images as more than simply a form of visual representation and consider their wider influence upon their audience. One way of doing so is to consider such images as a form of synaesthesia, evoking a particular sensory experience by stimulating other human senses. In the case of the postcards that I examine in this article, this would take the form of the visual evoking an auditory experience for those French citizens who received these images of music-making from Algeria. Michael J. Schmidt, in his work on jazz in Weimar-era Germany, notes that visual culture was far more pervasive in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries than auditory culture and that photographs and other visual media offer an important source of information for scholarship on music and sound during this period. Importantly, he argues that a synaesthetic reading of such imagery might allow us to overturn the supposed separation of the human sensorium, which had become established as an idea in the mid-nineteenth century, and enable us to better understand the ways in which people interpreted photographs of music at the time.Footnote 5 In other words, in an era when access to sound recordings and live performances of these musics was rare, people of the time were able to view photographs and imagine the sounds being produced. Clearly this differed significantly from listening practices, and the sounds being imagined may have been entirely inconsistent with the sonic realities of music in Algeria. However, I would argue that this is in itself significant, as photographers and postcard producers were aware that European audiences were unlikely to encounter musics and musicians from North Africa and could therefore use their imagery to project particular ideas of how Algeria might sound in ways that reflected the hegemonic power structures that were constructed through colonialism.

Another way of understanding the influence of these postcards is to place them within the wider European colonial apparatus of the time. Within the extensive body of scholarship on colonial Algeria there exists a significant amount of writing on the ways in which the French state used architecture to visually and symbolically control Algeria and how both public and private spaces became sites of resistance against colonial rule.Footnote 6 However, very little attention has been paid explicitly to sites of musical and sonic production, such as bandstands and concert halls. These were not only buildings and structures that visually reinforced the fact that the country was under French rule, but also shaped the soundscape of colonial Algeria. In featuring these structures on postcards, I argue that they became normalized in the minds of French citizens, and the presence of ‘Western’ art and military musics were accepted as integral to the daily soundtrack of life in urban Algeria. As such, postcard imagery served to ‘other’ Muslim, Jewish and Amazigh Algerian citizens through processes of exoticism, while simultaneously establishing European musical culture as accepted and conventional. And as products of the colonial regime, postcards remind us of the ways in which visual objects can provide forms of representation that are both shaped by political desires and divorced from lived realities.

In her study of Franco-Algerian film during the postcolonial period, Maria Flood writes that ‘the colonial relationship was founded on desire and projection. How the colony represented itself, and was represented by the colonized, generated political and historical reality, even if these representations were naïve or false’.Footnote 7 In this article, I aim to understand the role that these visual representations of musicians and music-making played for the French state at the time, and how they shaped the soundscape of colonial Algeria in the early twentieth century. I begin by providing contextual information about colonialism in Algeria and the emergence of the postcard industry, before examining some of the images of musicians that appear on these cards. I then move on to explore the depiction of bandstands on these postcards, interrogating the ways in which they evidence the colonial regime's management of Algeria's physical and sonic landscape, and the bandstand's role in shifting notions of public performance that have continued into the postcolonial period.

Postcards in colonial Algeria

Following a diplomatic incident involving the Dey of Algiers and the French consul, Algeria was invaded by French troops in June 1830. Given its vast geographic size, it took decades for the French to gain full control of the country, but by 1848 Algeria was declared an integral part of the French Republic, divided into three administrative départements.Footnote 8 Ruled from Paris, and effectively considered an extension of the French mainland, local Algerian culture and history were largely disregarded. French citizenship was initially restricted to European settlers, but later incorporated Jews, who nevertheless remained officially categorized as indigènes (natives). Muslims were not granted French citizenship, and while they could fight and die for France during both world wars, as they did in their hundreds of thousands, they could not vote in elections. As Arthur Asseraf explains, musulman (Muslim) remained a technical term, a racial category rather than an indication of a person's religious beliefs and practices.Footnote 9 It would be an oversimplification, however, to imagine that colonialism in Algeria simply reflected a confrontation between French imperialistic expansionism and Algerian resistance, and James McDougall writes that ‘beyond such myths, the story is more complex, less clear-cut. An interplay of uncertainty and ambition, opportunity and pragmatism, self-sacrificing resolve and ruthless determination’.Footnote 10 Within such a sociopolitical context, apparently innocuous objects, such as postcards, could play an important role in shaping power structures and representation.

The postcard was invented in Austria in the 1860s and ‘was authorized in France from 1872 [becoming] very popular after the Exposition Universelle of 1889 with cards of the Eiffel Tower’.Footnote 11 Postcard production expanded exponentially over the ensuing decades, reaching a peak in 1910 when 123 million cards were printed in France, highlighting the scale and profitability of the industry for French photographers and printing houses.Footnote 12 By 1900, around 30,000 people were employed in the postcard industry within mainland France, and this number would increase over the next three decades. The industry was so significant to the French economy that legislation was passed to support private printing houses and postage rates were reduced in the hopes of encouraging citizens to send even more postcards.Footnote 13

These cards offered a fast and affordable means of communication with friends and family, particularly for French citizens residing in or visiting North Africa. Many of these cards incorporated recurring visual tropes: scenic views of large cities, depictions of beautiful rural landscapes, mosques and Muslims at prayer, busy marketplaces, and posed photographs of highly exoticized subjects, particularly women. Cards featuring musical themes appeared less frequently but were still produced in large numbers, and there were hundreds of these designs, if not thousands, put into circulation in the early decades of the twentieth century.

The influence that these images had upon the French citizens who received them, and upon French society more broadly, should not be underestimated. Postcards normalized the presence of both native Algerian musical traditions and European art musics (performed by orchestras, ensembles, and military bands) within North Africa and hinted at the important role that the sonic domain played in shaping colonial society. These cards, I suggest, provide a particularly valuable source of historical information for scholars as they show how Algerians and Algerian musics were routinely depicted through a colonial lens. This was not a form of representation confined to academic circles or the educated middle classes in France, but as a result of their affordability and accessibility, postcards were available to every social strata. History has often tended to privilege the great works of renowned artists; this risks skewing our understanding of the ways in which visual culture shaped daily life in the early decades of the twentieth century. The advent of photography in the late nineteenth century increased access to visual materials, which provided the possibility of seeing cultures and events around the globe for those without the financial means to travel extensively. At a time when a relatively small proportion of individuals in Europe and North America would be able to ‘hear’ the rest of the world and their musics, photographs and postcards provided one way of ‘seeing’ it. However, photography was clearly still shaped by the intentions of photographers and editors, and the pictures that appeared on postcards, like those in magazines and newspapers, reflected a particular worldview that was normally Western and Imperialistic. As such, it is important that the postcards that I discuss in this article are understood in their historical, cultural, and sociopolitical contexts.

French understandings of colonial Algeria

In order to appreciate the social and political milieu within which these postcards were circulating in the early twentieth century, three particular issues warrant attention. First, by the end of the nineteenth century, Algeria had become a popular tourist destination for French tourists and travellers, who were able to make use of a burgeoning transport network throughout the north of the country. Tourism provided both a means of economic profit via the government-sponsored tourist industry and another way of visibly establishing French control in North Africa.Footnote 14 The city of Biskra, located on the northern edge of the Sahara, for example, was promoted as ‘The Queen of the Desert’ and attracted celebrated French and European figures throughout the early twentieth century, including writer André Gide and artist Henri Matisse, as well as Béla Bartók during his explorations of local folk music traditions. There was therefore a prevalent interest in the perceived otherness of North Africa among the French public at this time, which helps to explain the widespread popularity of the type of postcards that I am discussing here.

Second, most French citizens were unlikely to hear much Algerian music prior to the Second World War. Audio technologies, such as the gramophone, were prohibitively expensive, and few radio stations or record companies in France were taking a serious interest in North African musics at this time. Michael Denning suggests that up to the mid-1920s, the music industries focused upon live performance and sheet music publication, with audio recording difficult and expensive. While Denning notes that multinational record companies had been making recordings for local markets around the globe from the early twentieth century, he argues that reproduction technologies, such as gramophones, were ‘a piece of expensive furniture throughout the acoustic era, [and] these local recordings were limited to the high-status, cultivated musics of local elites’.Footnote 15 Gramophone and record sales did not increase significantly in France until the mid-1920s, and then plateaued during the 1930s due to the global economic crisis, before being limited by the outbreak of the Second World War.Footnote 16 I would argue, therefore, that in the early decades of the twentieth century, people in France were far more likely to ‘see’ Algerian music, depicted on postcards or in popular magazines such as L'Illustration, than they were to ‘hear’ it.Footnote 17

Third, as Jann Pasler has argued, French attitudes to colonialism took a sharp turn around 1900, shifting from an interest in assimilation and hybridity to a focus upon cultural difference. In the musical context, for example, Camille Saint-Saëns's Suite Algerienne of 1881 merged musical ideas drawn from the repertoire of the andalusi nubat with militaristic horn parts evoking the sounds of French army bands.Footnote 18 However, the Dreyfus affair and growth of nationalistic right-wing conservatism within mainstream French politics shifted attention away from assimilation and towards the demarcation of difference, of self versus other.Footnote 19 Moreover, Pasler writes that along with ‘anti-colonialist sentiment in the metropole [and] deep fault-lines in the French assimilationist project abroad, came racial panic (fear of racial degeneration) and increasing resistance to anything hybrid’.Footnote 20 The French mission civilastrice (civilizing mission) of the nineteenth century, which Andrea E. Duffy shows was closely linked with French industrial interests, had been replaced by the conscious othering of Algerian citizens.Footnote 21 Thus by the start of the twentieth century, the local cultures of the colonies were, in the minds of the French authorities, no longer something to be assimilated but rather to be preserved, and we can see the role that postcard imagery played in maintaining clear distinctions between Europeans and North Africans, and conserving Algerian musical traditions through French conceptions of Maghrebi cultural ‘authenticity’. Jonathan Shannon suggests that andalusi music, in particular, offered Europeans a way of understanding the relationship between Occident and Orient, Europe and the Muslim world, and this explains the support of the French authorities in efforts to preserve the music. Shannon writes that ‘twentieth-century nostalgia for things Andalusian owes a significant debt to colonial discourses of heritage and authenticity that in many ways constructed al-Andalus as an object of European fascination’.Footnote 22 Such was the prestige of andalusi in the eyes of the authorities at this time that in 1923 the first chair of Arab music was created at the municipal conservatory in Algiers.Footnote 23

Herman Lebovics notes that this was also the moment at which ethnography and folklore studies emerged in France, and this enabled French scholars to comparatively study ‘the other’ in order to articulate what, in their minds, made French culture both unique and superior. In the words of Lebovics, ‘the new politics and the new anthropology were connected’ and the pseudo-ethnographic nature of many of the postcards printed at this time provide further evidence of this relationship.Footnote 24

Images of exoticism

Postcards from this period are valuable historical objects for study because they enable us to observe multiple layers of connection and encounter during the early twentieth century; in this case between Algeria and France, Africa, and Europe; between politics, culture, and ethnography; and between photographer, subject, and publisher. Unsurprisingly, each of these relationships was enmeshed in social structures that sought to empower Europeans and marginalize North Africans. In his seminal work The Colonial Harem, Algerian writer Malek Alloula critiques French postcards of the period, charging photographers and postcard-producers with exoticizing Algerian women in order to reify the structures of control inherent in the French colonial project (Figure 1).Footnote 25 The looks on the faces of the women in this photograph, staring directly back into the camera's lens, are highly reminiscent of the images taken by French photographer Marc Garanger in the final years of colonial rule in Algeria. Garanger photographed Amazigh and Muslim women on behalf of the French army, producing staged images intended to appear on identity cards, but later republished in retrospective books. Karina Eileraas draws parallels between Garanger's work and the images that Alloula critiques, writing that ‘both sets of photographs manifest a history of colonialist intervention into the image or self-presentation of women, especially efforts to refashion or redress Algerian women's bodies according to divergent political objectives’.Footnote 26 Jennifer Howell notes that Garanger also produced work labelled as ‘ethnographic’, suggesting that

because ethnographic photography was meant to preserve the Other – and in particular the Oriental Other – as vestiges of the past, unscathed by Western notions of progress, it sought to capture images which reflected preconceived ideas of the backwardness and primitiveness of non-Western cultures’.Footnote 27

Figure 1 (Colour online) Three female Arab musicians in a staged scene, on a postcard sent in 1905 to a French recipient in Croydon, England.

Alloula argues that

The postcard is ubiquitous. It can be found not only at the scene of the crime it perpetuates but at a far remove as well. Travel is the essence of the postcard, and expedition is its mode. It is the fragmentary return to the mother country. It straddles two spaces: the one it represents and the one it will reach.Footnote 28

It is the sense of movement and encounter that Alloula alludes to here, which is the basis of my own analysis. Postcard imagery from colonial Algeria, I suggest, was always intended to forge meanings on both sides of the Mediterranean and to serve the objectives of a French authority intent on simultaneously dominating Algeria and relegating its peoples to second-class status. Furthermore, the inherent violence, both physical and psychological, that was part of French colonialism in Algeria (and throughout the Maghreb, more broadly) should not be underestimated, and neither should the role of these postcards in sustaining such violence. As Alloula adds:

Colonialism is, among other things, the perfect expression of the violence of the gaze, and not only in a metaphorical sense of the term. Colonialism imposes upon the colonized society the everpresence and omnipotence of a gaze to which everything must be transparent … The colonial postcard, for its part, fully participates in this violence. Moreover, it is a narcissistic expression. Only the coloniser looks, and looks at himself looking.Footnote 29

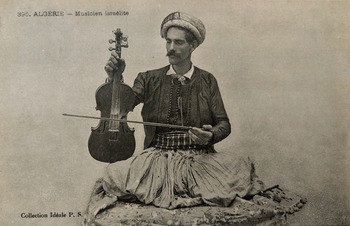

The tension between exoticizing fascination with Maghrebi culture and people and the desire for control is evident in many of the photographs of Algerian musicians that appeared on postcards at the time. Figure 2 shows a postcard sent from Oran (Wahran, in western Algeria) in 1908 to a recipient in Versailles. It features a man in traditional garb sat cross-legged on the floor and playing the kamancha, the upright fiddle used by performers of andalusi music and various associated styles.Footnote 30 The plain background of the image indicates that this was a posed shot taken in one of the many professional photography studios that emerged in Algeria in the late nineteenth century. Like many of these images, we have no clue as to the identity of the subject or whether he was in fact a musician. However, what we do know is that he was Jewish, and this is significant given the history of Judaism in Algeria. There had long been a significant Jewish presence in Algeria, dating back at least as far as the period of Roman rule in North Africa, and many of these Sephardi families could trace their heritage back to the human exodus from the Iberian Peninsula as a result of the Reconquista. This same mass migration was closely linked to the development of andalusi musical traditions (and andalusi culture, more broadly) in North Africa, and the music provided a context in which Jews and Muslims socialized and performed together. Glasser argues that:

The prominence of both Muslims and Jews in andalusi musical revival, as well as the presence of some Europeans in and around the revivalist circles even as andalusi music remained a primarily indigenous Algerian activity, makes it an especially evocative vehicle for grasping the texture of the colonial public sphere in the old urban centres and for tracing the circulation of an idiom of revival in both indigenous and European circles.Footnote 31

Figure 2 A Jewish musician playing the kamacha (upright fiddle), on a postcard image likely to have been taken in a professional photography studio.

While the finer details of this musical culture might not have been known to the average French citizen receiving such a postcard, the presence of a Jewish community in Algeria certainly was. In 1870, the Third Republic government had introduced the Crémieux decree, named after its author the French-Jewish lawyer and politician Adolphe Crémieux. This act automatically granted French citizenship to all Algerian Jews, a move which only served to increase tensions and resentment between the European, Jewish, and Muslim communities.Footnote 32 While Algerian Jews might still be ‘othered’ in the minds of many French citizens, and anti-Semitism was undoubtedly rife in both the French metropole and colonies throughout this period, they were also considered more enlightened and refined than their Muslim neighbours, and this posed image, incorporating modified Western instrumentation, reflects the slightly higher regard in which Jews were held.Footnote 33 However, this postcard also highlights the fact that Jews still remained relegated to second-class status in the minds of the French authorities, as we can see in the title assigned to the image: ‘Musicien israélite’. The choice of this term was not incidental, but rather speaks to the ways in which Jews were treated in official discourse at the time. As Samuel Everett explains, ‘the French colonial administrative term for Jews in Algeria was israélites as opposed to juifs … This underlined a racial conceptualization of the North African Jew taken from French anthropology. Jews were at once tribal descendants from Israel in biblical Palestine, and israélites indigènes, simultaneously similar to, in their backwardness, but religiously distinct from, Muslims.’Footnote 34 Thus the card presents this Jewish man both as a musician worthy of European attention and respect and as a second-class citizen, who, despite his official French citizenship, will always remain an othered ‘israélite’.

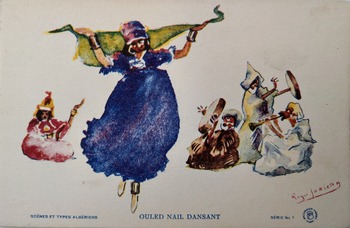

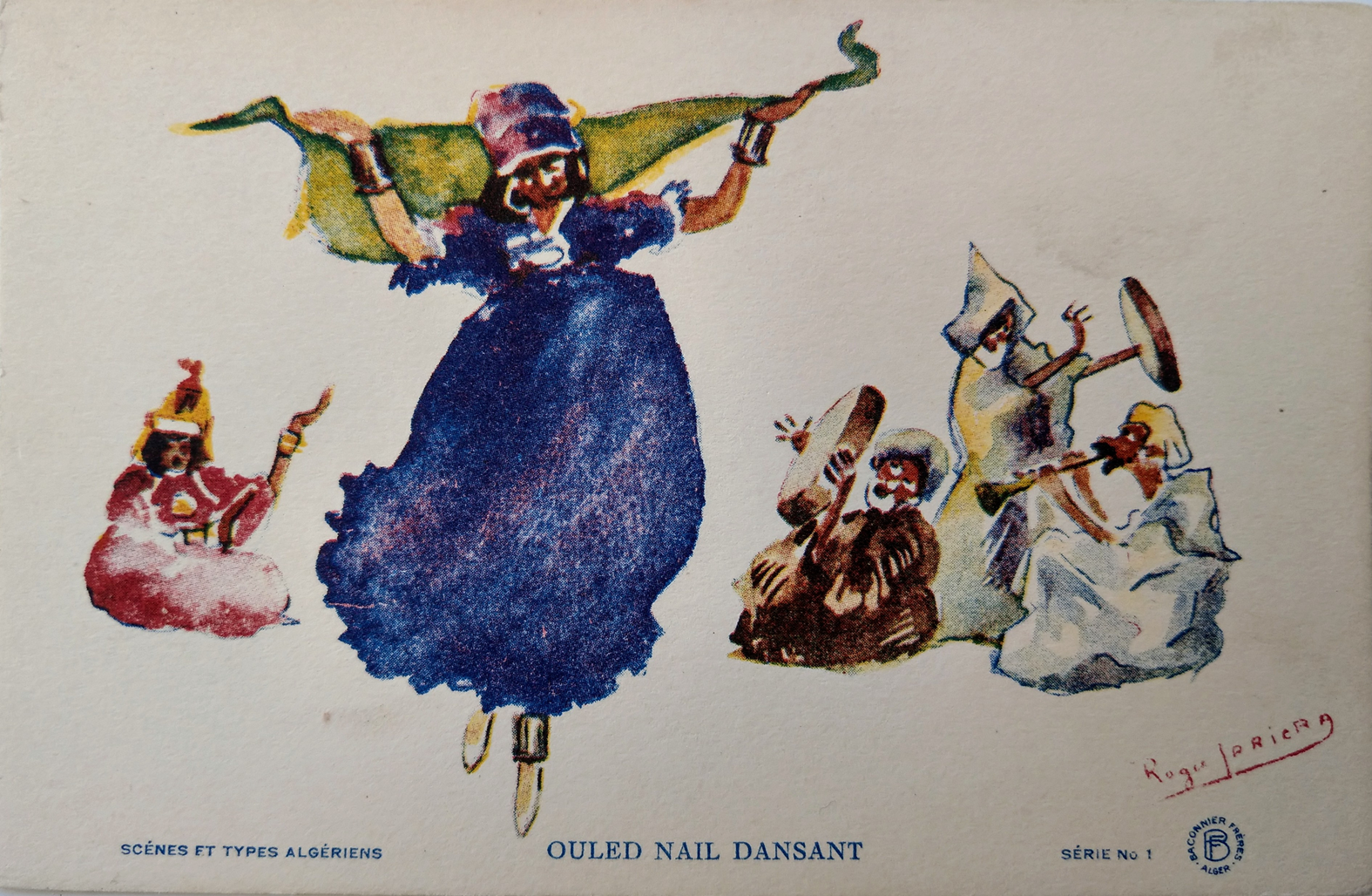

It is notable that Muslim and Jewish Algerians almost never appear in postcard images as performing musicians but are repeatedly depicted with musical instruments. The only time in which Algerians are seen in the active process of music-making is when they are involved in rituals (Amazigh folk traditions were particularly captivating for European audiences), accompanying dancing (Figure 3; belly dancers and the female dancers from the Ouled Naïl people of central Algeria appeared frequently on postcardsFootnote 35), or performing in military parades as part of the Zouaves and Tirailleurs Algeriens, the French army regiments that drew its soldiers from the local population (Figure 4).Footnote 36

Figure 3 (Colour online) A drawing on a postcard depicting a female dancer from the Ouled Naïl people, accompanied by musicians.

Figure 4 Drummers of the Tirailleurs Algériens, a regiment of the French army composed of local soldiers.

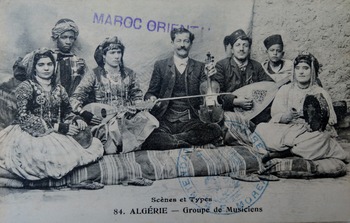

Postcards such as this, which feature images of individual musicians, are relatively rare, with posed shots of small ensembles appearing to be far more common. Figure 5 presents us with seven individuals, of which five are holding instruments used in the performance of andalusi music and other Algerian musical traditions: (from left to right) darbuka, mandole, kamancha, oud, and tar. Andalusi, in its various guises, is a music with a complex social position in both colonial and postcolonial Algeria. It was considered worthy of preservation from the early twentieth century onwards, and a number of French and European scholars were instrumental in attempts to ‘recover’ and protect andalusi.Footnote 37 It was never fully accepted by the French authorities during colonialism, but despite its somewhat chequered roots, andalusi has nevertheless embodied a degree of social decorum, and after independence in 1962 was supported by the postcolonial government as a symbol of nationalistic pride.Footnote 38 For the French, andalusi gradually became one of the more acceptable aspects of Algerian culture, while still remaining very much othered, an attitude that is evident in this photograph: while the two male musicians are wearing formal attire, similar to typical Western concert dress, the women appear in ‘traditional’ costume, reinforcing a clear sense of difference from French or European classical music.Footnote 39

Figure 5 (Colour online) Seven musicians, probably performers of Arab-Andalusi music, on a postcard that was never sent.

Notably, this particular postcard is the only one in my personal collection to include a written message on the reverse that makes explicit reference to music. In ink is scrawled the words ‘voici la grande nouba!’ (‘here is the great nouba’), which is followed by an illegible signature. This is significant for a couple of reasons. First, the message evidences the fact that some Europeans were familiar with Algerian andalusi music practices: the nouba here refers to the suite form used in various regional schools of Andalusi throughout North Africa, although the French often referred to the music itself as la nouba. The word is not printed anywhere on the card, so the person who wrote this message must have at least been aware of the nouba and was able to identify the musicians featured in the photograph as performers of andalusi. Second, there is no stamp, postmark, or address (the message in fact runs across into the address portion of the card's reverse), indicating that the card was never sent but rather kept as a souvenir or part of a postcard collection. Throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, postcard collecting was an established pastime for many French citizens and was particularly popular among urban bourgeois women.Footnote 40 In the case of this particular card, the written note and the fact that it was never posted suggested that it held a degree of importance for its purchaser, and that the musical image that appeared on it was significant. As I will discuss later in the article, this was not always the case.

‘Western’ music in Algerian spaces

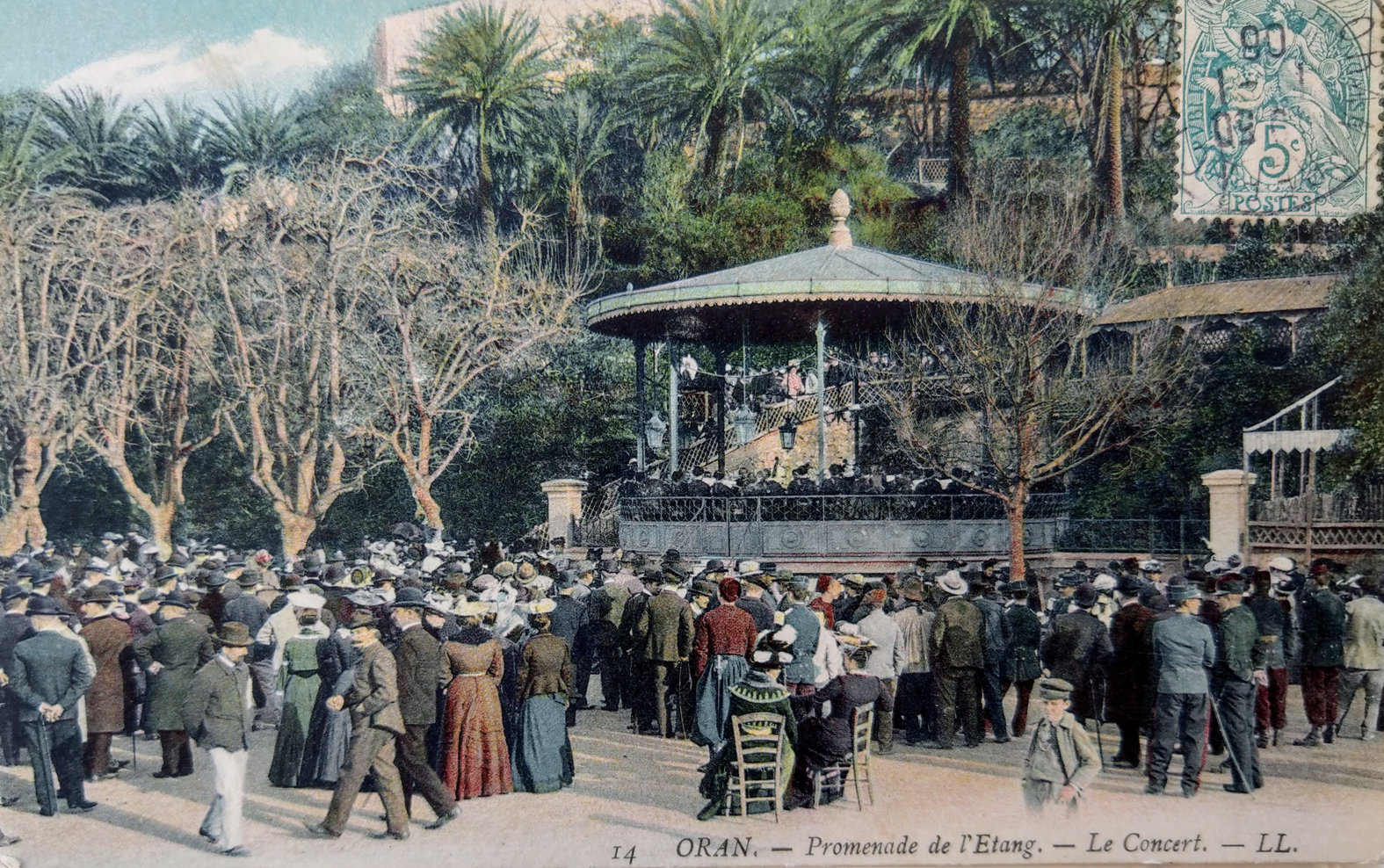

It was far more common for postcard images from colonial Algeria to depict ‘Western’ musical practices, including the performance of Western Art Musics. Figure 6 shows a postcard image from Oran, which was sent to France in 1906. The photograph shows a performance on a bandstand in the Promenade de l'Etang, a popular park situated a few hundred metres from the city's Mediterranean seafront. The audience, in the foreground, appears almost exclusively European, and features men and women in their finest clothes mingling with French soldiers of various rank. This is clearly a significant event, perhaps taking place at a weekend or on a date of celebration. The musicians on the bandstand are less clearly visible, but we can see that they appear to be wearing formal concert dress, and both music stands and the necks of cellos or double bases can be discerned. Images such as this, I argue, served to normalize the presence of Western musics within public spaces in colonial Algeria for the audiences that received these postcards. Aside from the word ‘Oran’, there is little to indicate that this photograph depicts music-making in Algeria, and this could easily be mistaken for a concert in a park on France's southern Mediterranean coastline. Yet such musical practices were entirely a product of European colonial presence in North Africa, and as this image shows, remained the preserve of European settler communities.

Figure 6 (Colour online) An orchestral performance for a European audience, in the Promenade de l'Etang in Oran, western Algeria. This postcard was sent to Metropolitan France in 1906.

Before I explore other images, there are two aspects of this particular card that warrant some attention. The first is the rear of the card, which contains a short message from ‘Jacques’ to a ‘Madame Rigole’ in the tiny Pyrenean commune of Oms, wishing her a happy new year. Brief communications such as this were common on postcards from this era as a postcard from Algeria to France ‘could be sent for five centimes instead of ten when they contained only a greeting and closing’.Footnote 41 We know nothing else of the sender or the card's recipient and can only speculate as to whether there was any significance for either person drawn from the image's musical theme. However, the card must have had some personal resonance for Madame Rigole as it has remained in almost pristine condition for over a century. The lack of reference to music within the message is unsurprising, and as I have previously mentioned, these written postcard missives commonly ignore the photograph featured on the front. Certain subjects were more likely to warrant a mention in a postcard's written message: senders often highlight their curiosity at images of groups of Muslim men praying in public, while more risqué subjects, such as belly dancers or semi-naked women, rarely get mentioned.Footnote 42 This absence of attention might suggest that the presence of musicians and musical performance is coincidental, and of little interest to those sending and receiving these postcards. However, I believe that such absence also speaks to the sense of normality constructed by these photographs. The clear visual division that takes place, between Algerian musicians as staged exotic objects and European musicians as public performers, served to structure musical life, both in Algeria itself and in the minds of the French citizens receiving these cards. Alloula, writing about postcard imagery in Algeria, argues that ‘the dancers and musical performers do not appear in front of an audience. Rather, they perform the obligatory ritual whose hieratic nature suggests the idea of a place and a feast outside space and time’.Footnote 43 As such, Muslim, Jewish and Amazigh citizens in Algeria were ‘visually silenced’ by postcard imagery and positioned as objectified curiosities in the minds of citizens in Metropolitan France.

Second, we might draw attention to the apparently trivial initials printed on the front of the card. Alongside the words Le Concert and its location (Oran, Promenade de l'Etang) appear the initials ‘LL’. These refer to the photographer, and the same initials can be found on thousands of images taken throughout North Africa and the Middle East during the early decades of the twentieth century. The photographer was never formally identified, and William Dûval describes the individual as ‘a bit of a Scarlet Pimpernel’, adding that ‘his globe-trotting activities took him and his camera to many places foreign to his native shores with no one quite knowing where or when he would turn up next. But such is the clarity and sparkling animation of his work, it is instantly recognizable even before those tell-tale initials have been sighted.’Footnote 44 Naomi Schor, however, suggests that the initials were those of brothers Abraham Lucien and Gaspard Ernest Lévy, French Jews who were the sons of Isaac Georges Lévy, founder of Léon et Lévy, one of France's most successful printing houses. The company won numerous awards for its images and produced tens of thousands of postcard designs throughout the second half of the nineteenth century and the early decades of the twentieth. Around 1919, the company amalgamated with their main competitor, Neurdein Frères, leading to the creation of Lévy et Neurdein Réunis, by far the largest producer of postcards in France.Footnote 45 Neurdein Frères was funded by the French government and charged with taking photographs for use in travel guides and other state-produced literature. They sent photographers to Algeria, but produced their postcards in France, before selling them back to businesses in North Africa, and Rebecca DeRoo writes that ‘because the postcards were bought, sold, and postmarked in Algeria, the role the French company took in their production was suppressed; the cards were understood by the French to originate from the colony and to reflect the sensibilities of the indigenous population’.Footnote 46

These details are significant because they evidence the ways in which imagery of music was entangled in a multimillion Franc industry in the early twentieth century, as this simple postcard, preserved by Madame Rigole, attests to. Yet this industry, supported in part by the French state, was deeply concerned with making their postcards appear as ‘authentic’ as possible. This image of a bandstand concert in Oran would therefore have been understood by French citizens as representing the realities of daily life in colonial Algeria, further normalizing the presence of Western Art Music. Given what we know about the social standing of those involved in the industry at this time, we might also believe that images of Western Art Music concerts, such as the one on this particular card, reflected the experiences and tastes of the very people taking the photographs and printing the postcards.

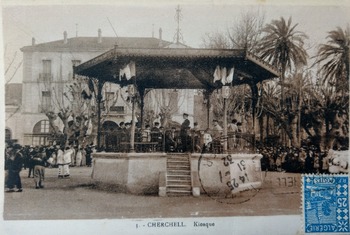

The Kiosque du Musique on the postcard

The presence of a public bandstand (kiosque du musique in French) on the postcard in Figure 6 might initially seem unremarkable but such structures appear repeatedly on cards depicting colonial Algeria and seem to be significantly over-represented in comparison with images of musicians and musical instruments. In many cases, multiple postcards were produced featuring different photographs of the same bandstand, which were commonly erected in parks or public squares in the heart of Algerian towns and cities. Many of these constructions were European in style and became sites of musical performance at weekends and on annual French public holidays, when they were adorned with tricolours and the emblems of the French republic (see Figures 7 and 8).

Figure 7 (Colour online) A postcard image of the bandstand in Cherchell, central Algeria, sent in 1932. The French tricolour and emblems of the French republic can be seen on the bandstand.

Figure 8 Europeans strolling near the bandstand in a public park in Annaba (known as Bône during the period of French colonial rule).

Their presence in Algeria at this time is unsurprising given the widespread construction of bandstands throughout Metropolitan France during the nineteenth century. Marie-Claire Mussat reports that around four thousand bandstands were erected across France between 1850 and 1914, and that their popularity reflected attempts to democratize access to art music for ordinary French citizens.Footnote 47 Given the purportedly egalitarian foundations of Republican France, the restriction of classical forms of music to concert halls and theatres was untenable and the kiosque du musique provided free performances in open public spaces, available (at least in theory) to all. In the words of Mussat:

A building that is both closed and open, the bandstand introduces an architecture of transparency to the city. Unlike the auditorium, a closed space that houses a ritual for initiates, it refuses secrecy: far from hiding, it reveals, thereby assuming the revolutionary heritage.Footnote 48

Such sentiments were certainly extended overseas, and Algeria, like other French colonies, became home to a large number of bandstands during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. These were, for the most part, stages for the performance of Western classical and French military musics, and their audiences remained drawn almost exclusively from European bourgeois settler society. However, while their active listenership was highly familiar with this repertoire, the impact upon the wider soundscape of urban Algeria should not be underestimated. Public spaces, which had long been sites of socialization among Muslims, Jews, and Amazigh citizens, were now sonically dominated by European musics. As such, bandstands not only provided a permanent physical statement of European colonial presence but also shaped the soundscape of urban Algeria, producing an auditory command of public space while local musical traditions remained restricted to private and quasi-public arenas. By visually inscribing them on postcards, photographers and printing houses reinforced this sense of control, normalizing the bandstand as a feature of urban colonial Algeria. Furthermore, this imagery separated French and Algerian citizens and their respective musical practices, producing a clear hierarchy within which Western musics were entitled to public performance in the very heart of Algerian cities and towns. Upon receiving these cards, families and friends in Metropolitan France were confronted with images of a highly stratified society, and Rebecca DeRoo writes that:

The cards express the separation of and difference between Europeans and Algerians in terms that were immediately legible to nineteenth-century Europeans: the organization of urban space and racial categories based on physiognomies. These frameworks were used to represent French control over and displacement of the Algerian population and to justify the French presence in Algeria.Footnote 49

While many of the bandstands that are featured on postcards from this time are similar to the structures that were appearing in parks and town squares across mainland France, others are more ornate and incorporate intricate designs typical of North African architecture. An example of this was constructed in the heart of Blida, a city in central Algeria located to the southwest of Algiers, where the bandstand stood in the heart of the main public square and featured the unusual sight of a palm tree growing upwards through its roof (Figure 9). While this and other similar kiosques might appear as though they were constructed by the local population, in fact they were products of a French orientalist imaginary that retained a strong interest in the architectural stylings of North Africa and Moorish pre-Reconquista southern Iberia. This fascination was so engrained that it resulted in the local French authorities adopting a form of neo-Moorish pastiche as the official government style and municipal buildings were erected across Algeria and Morocco using this architectural approach.Footnote 50 Bandstands became another physical medium for a colonial policy of appropriation and orientalist reinvention, and Herman Lebovics writes of a ‘stylized synthesis of Algerian architecture’, in which ‘not only are French rulers able to create native cultural traditions when they must, but they can invent characteristic architecture’.Footnote 51

Figure 9 The highly ornamental bandstand in the heart of the city of Blida, which appeared on numerous postcards throughout the colonial period.

The story of the design and construction of Blida's bandstand evidences the role that French local government and industry were playing in the emergence of such structures at this time. The kiosque was commissioned in 1910 by the city's mayor Victor Bérard, a French diplomat and scholar.Footnote 52 It was designed by the local municipal architect Dourel, who was instrumental in the reinvention of colonial-era Blida, and was constructed by the Spozio company, which had been founded by members of Algeria's Italian settler community. As such, the French authorities viewed the bandstand of Blida and similar structures across Algeria as a way of appropriating local architectural styles and then using them to create lucrative opportunities for members of the European settler community involved in their construction. Furthermore, these structures served only not as physical symbols of French presence in Algeria but also as sites of European music-making, in which Western art and military musics could dominate the soundscape of Algerian towns and cities. Given their location in central urban spaces, they served to radically reshape local soundscapes and to sonically dominate the daily lives of the Europeans and Algerians, Muslims, Jews, Christians, and Amazigh people living alongside one another.

Music-making in public and in private

These bandstands, I argue, represented not only a desire for French domination of public spaces and the urban soundscapes of colonial Algeria but also a deliberate attempt to control the performance of music in private. ‘Private’ spaces, such as family homes, had long played an important role within Algerian (and, more broadly, North African) societies, and their separation from the public realm was, and continues to be, clearly demarcated. This situation had only become more acute under French rule, and Zeynep Çelik writes that ‘for Algerians under the occupation, the domestic realm carried a special meaning as the private realm where they found refuge from colonial interventions that they confronted in public life’.Footnote 53 Musically, these private spaces, as well as quasi-public spaces such as the cafes maures (ostensibly public but frequented by an entirely non-European, Algerian clientele), were vital for the preservation of local musical traditions and the emergence of new forms of musical expression in the face of colonial repression and disregard for Algerian culture.Footnote 54 While homes, cafes, and local communal spaces became sites in which Andalusi music was taught and performed, and chaabi would emerge in urban Algiers, the public spaces in which bandstands were erected were not considered by local musicians to be a context in which music-making would take place.Footnote 55 In other words, the concept of both the bandstand and the very idea of performing music in such a public space were imported via the colonial regime.

The bandstand therefore acted as a means of shifting the focus of Algeria's urban soundscape into the public realm, through both overt and covert means. On the one hand, music emanating from these kiosques became the soundtrack of towns and cities across the country, at least during weekends and public holidays, when orchestras, ensembles, and military bands sonically asserted European control over the Maghreb. On the other hand, performance opportunities gradually increased for local musicians within those public spaces commanded by European society. While such opportunities might be welcomed, the force of coercion within this context should not be overlooked. By bringing Algerian musicians and ensembles into bandstands and public spaces, control of cultural production and dissemination shifted into French hands. Europeans expressed both fascination and fear of Algerian private space, as an unknown arena in which anti-colonial sentiment might be fostered, and Çelik writes that:

To the colonizers, the Algerian house represented the most impenetrable aspect of Algerian life, focused on the activities of the family and of women. In the ambivalence that typifies the colonial discourse, the house nurtured Orientalist fantasies that justified the superiority of the colonizer and his right to power, yet it also stood as a barrier protecting the sanctity of the Algerian society, signifying its resistance and hence testifying to a failure in the colonial project. To know and document this realm in order to break it open became an important item on the French agenda.Footnote 56

European photographers were certainly keen to gain access to private homes, and a number of postcards from the period appear to feature images that were taken in such contexts. However, these were far from realistic or ethnographic depictions of lived experiences, and where such postcards feature music, they always feature individuals or small ensembles in highly stylized poses. In dismantling the boundaries between the public and private realms, these photographers soon discovered that their very presence prohibited access to any sort of encounter with the realities of daily life for Algerian citizens.

Similarly, Rebecca P. Scales notes the fear that widespread access to radio technologies engendered among the French authorities in 1930s Algeria, and she suggests that ‘radio sound, as a transgressive, invisible, and distinctly modern medium that could transcend physical barriers and traverse the divide between public and private life, appeared to Europeans to be both a promising instrument of social control and a risky tool of social democratization’.Footnote 57 Surveillance of Algerian spaces in which groups of Algerians collectively listened to radios and gramophones, particularly the cafes maures, intensified around this time and Scales adds that:

Despite colonial enthusiasts’ elaborate schemes to promote indigenous radio listening in French overseas colonies through the installation of central village radios and loudspeakers in markets and public squares, colonial civil servants in Algeria judged metropolitan fantasies for creating a mass of docile native listeners to be woefully impractical and politically naïve.Footnote 58

It is clear that the French were both intrigued by and concerned about those Algerian spaces, private and quasi-public, from which they were excluded. Given the authorities’ fears about the potential power of music and broadcast sound, gaining leverage over musical performance and the urban soundscape was a serious concern. At the same time, the performance and circulation within private, non-European spaces of many traditional and emerging Algerian musics made them extremely difficult to ‘capture’ through photography, and this goes some way to explaining the focus of postcard imagery upon bandstands and highly stylized images of Algerian musicians.

It would be inaccurate, however, to suggest that a gradual shift towards public musical performance was simply an imposition upon the local population, and the agency of Algerian citizens is evident in the emergence of andalusi musical ‘associations’ at the start of the twentieth century. The first associations appeared as young, highly educated Algerians sought a way of assimilating into French society while partaking in political action that might increase the rights of Muslims and Jews and create a new civil society in North Africa.Footnote 59 This was an elitist network of mostly Muslim men educated within the colonial system who were often labelled m'tournis (traitors) by their fellow Algerian citizens, and their backgrounds would shape the development of the system of formalized preservation that remains evident in contemporary andalusi musical practices.Footnote 60 Expanding upon this mantle, musical associations offered opportunities to learn and perform andalusi, as well as a space for social interaction. Jonathan Glasser writes that ‘created as a vehicle for modernist pedagogy and public performance at the beginning of the twentieth century, the association has been an important way for amateur music-lovers to exercise their passion for andalusi music while differentiating themselves from the professional, often working-class, shaykh [master]’.Footnote 61

The first appearances by andalusi ensembles within the Algerian public spaces controlled by the French took place in the early twentieth century as part of a cultural revivalist project. One of the most important figures within this movement was the French writer and musicologist Jules Rouanet, who became a leading proponent of Arab musics, and in particular andalusi. He worked with a number of musicians and ensembles, perhaps most famously the Jewish Algerian musician and composer Edmond Yafil, who is a highly respected figure within the history of andalusi. McDougall importantly points to the fact that ‘Yafil's work, and the frequent centrality of Jewish musicians to andalusi, and, later, chaabi performance, was both an echo of an older pre-colonial and cross-confessional urban culture, and an indication of the extent to which cultural space could still exist at the overlapping margins of colonial society.’Footnote 62 Together they formed the Orchestre Rouanet and Yafil, and Glasser writes that ‘this ensemble performed some of the first concerts of andalusi music in the public squares of Algiers and was one of the groups recorded on disc by Gramophone in 1910’.Footnote 63 The connection between the visual and sonic aspects of the ensemble is significant here. In bringing andalusi into a more public realm, the orchestra were making the music both ‘audible’ and ‘visible’ to a much broader audience, including those from the European sections of colonial society. Not only did their music shape the soundscape of the spaces in which they performed, but the notability that this produced led in turn to commercial recordings with a leading European record company. As such, it was this new public presence for andalusi music that led to it being recorded and distributed, both throughout North Africa and (to a lesser degree) in Europe.

Similarly, the emergence of Algerian raï in the first half of the twentieth century was also shaped by a shift of musical performance into the public domain. Ted Swedenburg notes that French colonial agricultural policy was responsible for widespread rural-to-urban migration, which brought traditional bédoui music into towns and cities. Respected male performers of bédoui, who, like their andalusi counterparts, took on the moniker shaykh (commonly spelled cheikh when applied to raï musicians), attempted to position their music as socially reputable. However, other musicians in the vanguard of raï's early years were less celebrated, and this included in particular the female singers known as cheikhat.Footnote 64 These women were generally frowned upon by the more conservative elements of Algerian society, as they performed in public contexts considered inappropriate, and Swedenburg writes that ‘not only did the cheikhat wander the countryside during the colonial period, performing at weddings and at saints’ festivals known as waʾdat, but they also brought their music to the cities of western Algeria to play in the suqs, public squares, cafés-concerts and bars’.Footnote 65 It was here that Europeans would have their first encounters with raï, and the unofficial support that musicians would receive from European and Algerian patrons would gradually see the music grow in popularity throughout the twentieth century. By the late 1970s, the emergence of an increasingly liberal society coupled with exposure to a broad variety of international recordings saw raï musicians develop a cosmopolitan sound popular with younger audiences. Their public presence increased throughout the 1980s, and by the 1990s a large number of Algerian singers (predominantly male) were living in France, making recordings with leading commercial record companies. More than half a century after the poor cheikhat forged a new musical pathway for raï in Algeria, the music found itself visible outside North Africa for the first time, sonically and visually present on French airwaves and celebrated by non-Algerian listeners. The precedent created at the start of the twentieth century, when bandstands strove to normalize public music-making in urban Algeria and postcard imagery represented this to French audiences, could be discerned at the end of the century, as raï once again brought Algerian music to European eyes and ears.

Conclusions

At the start of the twentieth century, music-making within the public sphere in Algeria was predominantly controlled by the French colonial authorities, with local musicking practices confined to private and quasi-public spaces. The construction of bandstands within the parks and squares of Algerian towns and cities provided a space within which European musics could be performed and would gradually host andalusi ensembles and orchestras. While these physical structures served to assert French colonial dominance in Algeria, the musical performances that they facilitated produced a form of sonic domination, through which urban soundscapes were controlled and fashioned for European ears. By photographing these kiosques and featuring them on postcards and in magazines, their presence in North Africa was normalized in the minds of the French citizens on the other side of the Mediterranean who received them. Photography remained a relatively new and novel form of communication in the early decades of the twentieth century, and the notion that photographic ‘truth’ was immutable pervaded widely. Thus, photographs of musicians, instruments and musical performances were believed to reflect the reality of cultural life within colonial Algeria. Local Muslim, Amazigh, and Jewish musicians could be visually reified as exotic curiosities, while European art and military musics were normalized as a part of everyday life.

At the same time, these images also reflected a desire to shift musical performance into public contexts as a result of the fears of Algerian private and personal spaces. By placing musicians into the public sphere and capturing them on photographic images, the French colonial system was able to control cultural production and reflect this back to citizens in Metropolitan France. As Çelik argues, ‘visual culture was central to shaping the debate on the Algerian private sphere’, and through photographs, space was ‘thus mediated by photographs for the metropolitan imagination, contributing to the development of a collective consciousness about the power of the French empire’.Footnote 66

For a French general public with little knowledge of, or access to, Algerian music, the exoticizing images of Muslim, Jewish, and Amazigh musicians that were produced in professional photography studios served to construct and reinforce cultural stereotypes. Furthermore, they visually evoked musical events when their sonic elements were entirely absent. The instruments, costumes, and poses of the musicians who appeared in these photographs were rendered through an orientalist imaginary and provided a synaesthetic experience for the millions of French citizens who would receive these cards throughout the first three decades of the twentieth century.

As such, it is important that we understand the postcards produced within colonial Algeria during this period not as simple images printed onto small pieces of cheap cardboard a century ago, but rather as historical objects that reveal the ways in which the colonial authorities and French public of the time understood and represented musicians and music-making in North Africa. Entwined within these images are visual representations not only of Algerian musicians of the period but also of the place of music and sound within the power structures of the colonial state. For musicologists, they provide a window into the quotidian visual representation of music and sound for European citizens unable to hear the French colonies of North Africa. However, they also point to the musical and sonic priorities of the French state in Algeria, particularly in their depictions of bandstands within public space, and enable us to appreciate the type of iconography that the French state and industry were keen to project back across the Mediterranean to Metropolitan France. While Algeria and France's relationship was undoubtedly both intimate and fractious, these postcards are certainly not unique, and there are surely images from around the world during this period that might tell us more about the role of music in the relationship between coloniser and colonized.

The Algerian war of independence, fought between 1954 and 1962, produced a dynamic but fractured postcolonial nation. Algerian musical culture had been vibrant during the period of colonialism despite the restrictions of French rule, as evidenced by the birth of genres such as raï and chaabi, and the intersection of andalusi and Western Art musics. Nevertheless, independence offered Algerian musicians and audiences’ greater creative freedoms and opportunities to reclaim public space. Today, the kiosque du musique that was constructed in 1910 still stands in the heart of Blida, in the renamed Place du 1er Novembre, which publicly commemorates the start of the war of independence against French colonialism. It offers a reminder of French rule in the centre of a reclaimed public space but is no long a regular venue for carefully mediated musical performances. Instead, the musicians and listeners of contemporary Blida engage with music in cafés and homes, at weddings and Eid celebrations, and on stages in public venues designed, constructed and managed by, and for, local people.