On 28 December 1471, faced with the presence of paupers taking shelter under the porticoes and loggia of the Ducal Palace and the Basilica of San Marco in Venice, the Senate issued a decree attempting to resolve the illegal occupation of the city's religious and political centre. As the decree announced,

It has been decreed and determined in this council that, for the sheltering of the poor – who are found in the portico and arcades of the [Ducal] Palace and of the church of San Marco – there should be made a place of refuge in another suitable place. Certainly it is a matter of greatest piety, and a charitable gift before God, insofar as those poor are being consumed by cold, hunger and nudity. And therefore, with all things considered that need consideration, there is no place more fitting and convenient – and indeed, at the same time, more advantageously and agreeably provisioned – than the Campo Sant'Antonio. May it be decreed that the Ufficio del Sal [the Salt Office] must make a cohopertum [shelter] for the said poor in Campo Sant'Antonio, where it will seem more fitting. And let it be known that the Collegio should have the responsibility of providing that that swamp – which is between [the churches of] San Domenico and Sant'Antonio – shall be filled, over which place the same Ufficio del Sal must make a shelter, so that it always exists for sheltering the poor of this sort, who always turn to our city for the honour of God, for whom there is nothing that may be done which is more pleasing, and more agreeable for piety and for his mercy.Footnote 1

In summary, the Senate's concern over the fact that these paupers were hungry, freezing and in a state of undress led to a determination that the Ufficio del Sal, the office in charge of Venice's salt monopoly and with jurisdiction over state buildings, was to construct a cohopertum, a simple wooden canopy or shed, at the Campo di Sant'Antonio – an area located in the south-eastern edge of the city then known as the Punta di Sant'Antonio (Figure 1).Footnote 2 Prior to the beginning of construction, however, the Collegio, the government's highest executive branch, was expected to intervene in the area by filling the velma, the marshy terrain exposed during low tides and submerged during high tides.Footnote 3

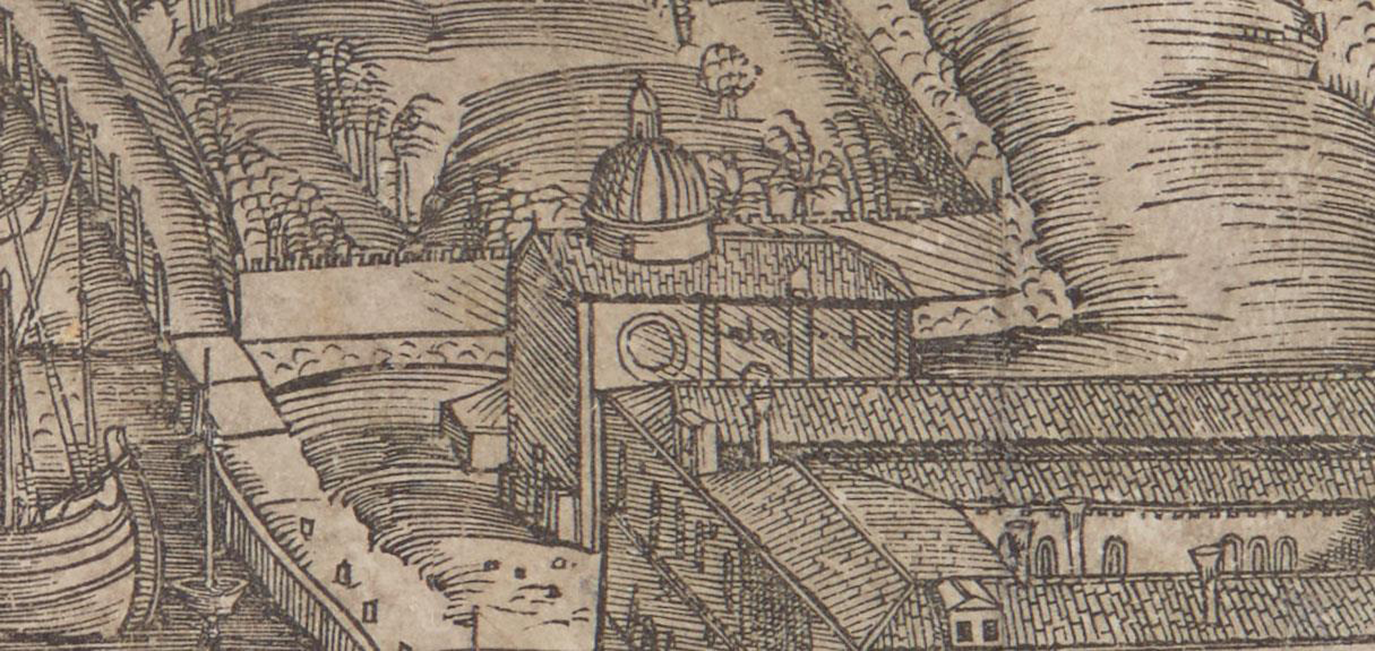

Figure 1. Jacopo de’ Barbari, View of Venice (detail), 1500. The Punta di Sant'Antonio occupies the lower part of the image. The southernmost bell tower marks the monastic complex of Sant'Antonio, while the adjacent structures represent the Ospedale and church of Messer Gesù Cristo. The convent of San Domenico is marked by the first bell tower further inland, and the Arsenale occupies the large walled area to the north. Duke Digital Repository. Accessed online: 25 September 2020, https://doi.org/10.7924/G8MK69TH.

But who were these paupers who took shelter at Piazza San Marco and would be relocated to and served by the cohopertum? Evidence from earlier that year suggests that the poor found in the area of San Marco were immigrants fleeing Venetian colonies in the east. On 8 February 1471, for example, the Senate ordered migrants found in San Marco to be transferred to and accommodated at Marghera.Footnote 4 By the fifteenth century, Venice's dominions extended beyond the city and incorporated both a Stato da mar, constituted by overseas territories, and a Stato da terra, formed by possessions on the Italian mainland.Footnote 5 Starting in 1463, a series of wars began between the Republic and the Ottoman Empire over control of Venice's overseas colonies. As a result, Venice saw continuous waves of displaced migrants arrive in the city. Confirming that ‘the poor of this sort’ always turned to Venice, the decree determined the creation of a shelter for these refugees at the Campo di Sant'Antonio.Footnote 6

Studies of ephemeral architecture in the early modern period have traditionally concentrated on structures built for royal and celebratory events. Yet, the example of the shelter at Sant'Antonio and other less alluring temporary constructions have the potential to raise questions regarding the scope, mutability and materiality of early modern urban fabrics, in some cases giving agency to historically dismissed or disempowered sections of the population.Footnote 7 This article seeks to contribute to this broader and more inclusive understanding of early modern cities. Specifically, I position the ephemeral structure of the cohopertum in the context of an early modern refugee crisis stemming from Venetian colonialist expansion and within Venice's multi-pronged urban and architectural responses in poor relief. This focus on the shelter not only clarifies what constituted an emergency in the early modern city but also illuminates Venice's resourceful response to critical urban developments in the late fifteenth century. The shelter's geographic position, in particular, demonstrates the Republic's ability to turn the presence of migrants and their resulting social pressure into assets for the local community and the Venetian military. Due to its mission to shelter eastern refugees, the cohopertum is also part of a larger picture – one embedded in Venetian affairs in the east, stemming from and aiming to stabilize the Republic's presence in the eastern Mediterranean. In this way, the shelter manifests a different Venice from the one typically described: not the thriving, cosmopolitan port city that attracted foreigners, but a metropolis forced to face and creatively address the consequences of its ambitious expansion.

More broadly, despite the persistence of mass displacements today, scholars of Refugee Studies have called attention to the systematic exclusion of refugees from history.Footnote 8 According to Tony Kushner, this historical exclusion has not been accidental. Rather, it results from an active act of forgetting those who witnessed past tensions, crises and wars but did not have a prominent role in national dramas.Footnote 9 More recently, historians such as Nicholas Terpstra have attempted to address this scholarly omission, rewriting histories that highlight the fundamental roles played by those displaced.Footnote 10 In architectural and urban history, however, the absence of refugees remains pervasive. Frequently associated with makeshift and temporary construction that was neither aesthetically pleasing nor centrally located, the architecture of refugees is no doubt harder to access in the historical record. Yet, as Philip Marfleet has argued, ‘denial of refugee histories is part of the process of denying refugee realities today’.Footnote 11 Denying the historical impact of refugees on urban fabrics would not be any different. As populations continue to be systematically displaced today as a result of wars, famines, diseases and other factors, these movements must be understood as part of a historical continuum. By focusing on the first documented shelter for refugees in early modern Venice, this intervention marks an important contribution not only to the history of Venice but also to the larger field of Refugee Studies, particularly as it intersects with urban history.

Issues of continuity: shelter and hospital

As demonstrated by analyses of later emergency shelters in early modern Venice, and perhaps due to their makeshift quality and similar geographical location, historians of Venetian charity have addressed these structures as precursors to permanent institutions that subsequently occupied the same site.Footnote 12 In the case of the shelter at Sant'Antonio, the cohopertum has been discussed in connection to the Ospedale di Messer Gesù Cristo (1474), which existed in the same general area as the shelter until its demolition in 1810 (Figure 2).Footnote 13 During this period, the terms ospedale (hospital) or ospizio (shelter) broadly defined institutions that sheltered and provided for the sick and poor, either permanently or during a critical period in an individual's life.Footnote 14 Commissioned by the Venetian government, the Ospedale di Messer Gesù Cristo originated as a governmental attempt to alleviate Venice's overwhelmed charitable system of support for the city's sick and poor through the construction of a general hospital with wide-ranging functions.Footnote 15 The first stone for the hospital was set in 1476, and starting in 1485, the Procurators de supra in charge of the Ospedale obtained a series of papal bulls to support construction of the institution. Until its destruction in the nineteenth century along with most of the buildings at the Punta di Sant'Antonio to create space for the Napoleonic Gardens, the institution occupied, like the shelter, the site between the monastic complexes of Sant'Antonio and San Domenico (see Figure 1).

Figure 2. Jacopo de’ Barbari, View of Venice (detail), 1500. This detail shows the monastic complex of Sant'Antonio with the Ospedale and church of Messer Gesù Cristo to the north. The buildings face the Canale di San Marco. Duke Digital Repository. Accessed online: 25 September 2020, https://doi.org/10.7924/G8MK69TH.

Since no depictions of the cohopertum have been identified to date, scholars have assumed that the shelter and Ospedale occupied the same site, with the hospital representing a more permanent iteration of the cohopertum. In an example of hindsight bias, despite the lack of evidence connecting the shelter and hospital, discussions of the cohopertum have historically appeared in studies of the Ospedale, creating a direct connection between the two structures that, in fact, did not exist.Footnote 16 Rather, the 1474 Senatorial decree establishing the Ospedale gave freedom to the hospital administrators to determine where the hospital should be built (‘far dichiarir dove el se habbia a fare’), suggesting that the institution was not initially envisioned as a physical replacement for the shelter.Footnote 17

In this case, modern understandings of ‘emergencies’ versus ‘crises’ help us better comprehend how the roles of these structures differed.Footnote 18 Borrowing from disaster management literature, this article considers an emergency as ‘a state in which normal procedures are suspended and extra-ordinary measures are taken to save lives, protect people, limit damage and return conditions to normal’.Footnote 19 Meanwhile, a crisis presents a difficult or dangerous period of time to an individual or small population, threatening public trust and eventually triggering changes in public policy. Thus, an emergency is an abrupt change that requires immediate action: the sudden arrival of a group of refugees in Venice during winter followed by the fast construction of a structure to shelter them. A crisis, on the other hand, does not result from an unanticipated event but rather from the accumulation of issues over time: the inefficiency of Venice's charitable system combined with population growth and an increase in the numbers of the local and foreign poor led to the need for a general hospital (the Ospedale di Messer Gesù Cristo) to treat the sick poor. Both emergencies and crises are expected to lead to disaster and, as such, require intervention by authorities. Yet, these definitions also caution us against conflating the histories of the cohopertum and the Ospedale di Messer Gesù Cristo. Contrary to the initial vision for the Ospedale to tackle poverty and disease in the city as a whole, the cohopertum merely provided overnight shelter for the poor, who were otherwise to support themselves by begging throughout the city during the day.Footnote 20 More specifically, the temporary shelter targeted the poor who could be found sleeping in the porticoes of San Marco and the Ducal Palace, relocating them from that central area to a site that would help their integration into society. Extracting the cohopertum from the Ospedale's much longer history, this article exclusively addresses the construction of this temporary shelter as a rapid response to an urban and social emergency in fifteenth-century Venice.

The urban development of the Punta di Sant'Antonio

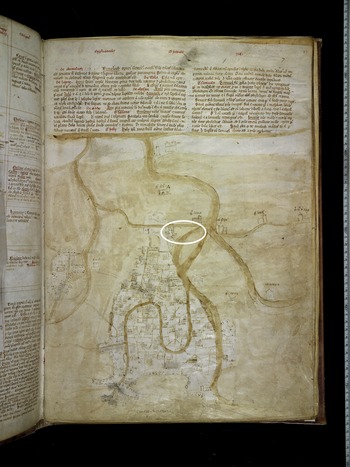

Development of the site chosen for the cohopertum had begun in 1334, when the Maggior Consiglio ceded the lands at the Punta di Sant'Antonio to Marco Catapan and Cristoforo Istrigo, two cittadini (citizens) of the island of Sant'Elena.Footnote 21 Visible in the view of the city by Fra’ Paolino from c. 1346, the area appears undefined, likely still a marshy site with shallow waters (Figure 3). Throughout the fourteenth century, landfills stemming from private and religious initiatives took place in various areas of Venice, promoted by the Republic as a strategy to expand the city's habitable zones. Not coincidentally, the land concession to Catapan and Istrigo required that they fill the lot in question, measuring 40 x 60 passi (steps), within three years.Footnote 22 The two cittadini must have satisfied this requirement by 1336, when the Magistrato al Piovego, the magistracy overseeing the maintenance and repair of streets, bridges, canals and quays in Venice, confirmed the presence of a pallificata, a required structure built as part of land reclamations to prevent landslides.Footnote 23

Figure 3. Fra’ Paolino, View of Venice from Chronologia magna, c. 1346. The circle indicates the area of the Punta di Sant'Antonio, still undefined then. Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, Mss. Lat. Z. 399 (=1610), fol. 7r. Courtesy of the Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo – Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana. Reproduction forbidden.

After building a wooden house on the site, Istrigo offered it to the Florentine friar Giotto degli Abati, then prior of the congregation of the Canons Regular of St Anthony of Vienna in France.Footnote 24 With the help of Istrigo, Catapan and others, the friar established a monastery at the Punta.Footnote 25 In 1346, Doge Andrea Dandolo (r. 1343–54) set the first stone for the future church of Sant'Antonio di Castello and its annexed hospital, which would give the Punta its name.Footnote 26 The church was finished by 1347, when the main altar received a polyptych by Lorenzo Veneziano.Footnote 27 In order to connect the newly reclaimed lands to the city proper, Venetian authorities had already asked the Dominicans who owned the land separating the Punta from the rest of Venice to allow the friars of Sant'Antonio to build a path (1334) and bridge (1342) through their possessions.Footnote 28 Finally, in 1359, the Maggior Consiglio granted the monastery ownership of the entire Punta di Sant'Antonio.Footnote 29 The friars acquired another stretch of land in 1364, this time towards the Canale di San Marco, and in this way, the Punta assumed the topographical characteristics it would keep in future views of the city (see Figure 1).Footnote 30

Building the shelter

The commission of the shelter initiated the development of the area between San Domenico and Sant'Antonio in 1471, with the Venetian Senate engaging the Collegio and the Ufficio del Sal to guarantee the reclamation of the marshy site at the Punta and the construction of the temporary structure. The cohopertum was operative by August 1472, approximately eight months after the Senate's decision to establish the shelter, if not earlier. On that date, recognizing that some paupers were not physically able to beg, the Senate established a food subsidy for the shelter.Footnote 31 It was determined that the Provveditori alle Biave, the commissioners in charge of grains, were to send two staia (approximately 166 litres) of bread for the poor on a weekly basis.Footnote 32 This Senatorial measure remains significant since it established a terminus ante quem for the opening of the shelter. Moreover, combined with later data, this food subsidy can also hint at the number of paupers living at the cohopertum. A 1649 publication indicates that Venice then consumed 634,888 staia of bread per year. Considering that the population in 1642 was 120,439, it is possible to estimate that a person ate approximately 5.3 staia of bread in a year, or 0.1 staia in a week.Footnote 33 This is, of course, a rough estimate that does not account for social class, wealth or a more complete diet. Yet, based on these numbers, the 2 staia of bread sent to the cohopertum could feed approximately 20 people per week. Since the decree specifically targeted those who were physically unable to beg, the number of paupers at the shelter was likely much higher, accounting for the individuals able to roam the city asking for alms.

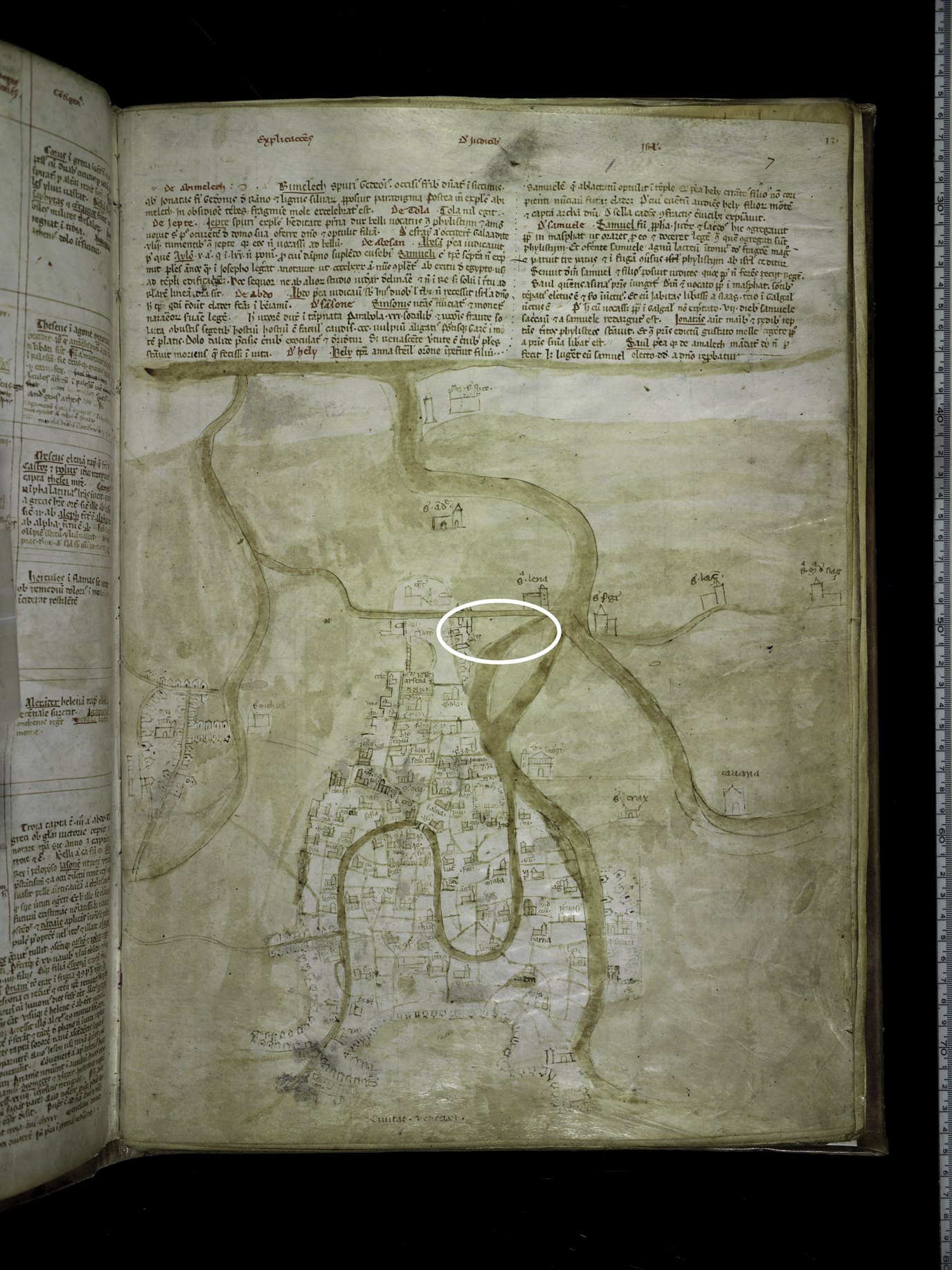

Despite our knowledge that the shelter was operative by August 1472, the area between San Domenico and Sant'Antonio encompassed a substantial stretch of land, and the precise location and appearance of the cohopertum have remained obscure (see Figure 2). Using recent high-quality scans of Jacopo de’ Barbari's View of Venice (1500), this article hopes to shed light on the matter.Footnote 34 A detail of the Punta di Sant'Antonio shows a previously unnoticed tent-like structure to the right of the hospital church (Figure 4). In his De situ urbis Venetae (c. 1494), fifteenth-century historian Marco Antonio Coccio, best known as Sabellico, mentioned a wooden church next to the later Ospedale di Messer Gesù Cristo.Footnote 35 John McAndrew hypothesizes that Sabellico, who visited the site between 1489 and 1490, perhaps saw a small oratory erected to serve the Ospedale while the hospital church of San Nicolò de Bari remained under construction.Footnote 36 Indeed, it is possible that this wooden structure described by Sabellico and discussed by McAndrew could have been the lower building identified by this study in de’ Barbari's View. Yet, it is also possible that it was the cohopertum, especially since the structure features the rectangular shape and triangular roof pitch historically associated with tents.Footnote 37 If correct, this hypothesis would suggest that the shelter remained in place into the sixteenth century. The original decree commissioning the cohopertum hints at this possibility, claiming that the ‘Ufficio del Sal must make a shelter, so that it always exists for sheltering the poor of this sort.’Footnote 38 It would not be unreasonable for the Senate to count on the longevity of a makeshift shelter. As studies of ephemeral structures have demonstrated, some of these constructions could survive for generations.Footnote 39

Figure 4. Jacopo de’ Barbari, View of Venice (detail), 1500. Visible in the detail is the previously unnoticed tent-like structure, likely the cohopertum, to the right of the hospital church. Duke Digital Repository. Accessed online: 25 September 2020, https://doi.org/10.7924/G8MK69TH.

Contextualizing the shelter

The construction of temporary structures as responses to urban crises related to disease and poverty was not novel in European cities in the fifteenth century.Footnote 40 Scholarship on plague outbreaks has shown that the provisional occupation of existing buildings or the construction of ephemeral structures constituted the most makeshift and expeditious forms of response to an epidemic.Footnote 41 Visual evidence of ephemeral responses to plague comes from a detail of a painting known as the Madonna dei tencìtt (or Madonna degli sporchini), Giovan Battista Rastellini's 1890 copy of an original created by prior Bernardo Catoni in 1630–31.Footnote 42 The painting's foreground shows the presence of dozens of tents in the courtyard of Milan's Lazzaretto during the 1630 plague outbreak (Figure 5). Traditionally, these improvised shelters would be burned once the plague subsided.

Figure 5. Giovan Battista Rastellini (after Bernardo Catoni), Madonna dei tencìtt (detail), 1890. Located in Via Laghetto, Milan. Source: Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lazzaretto_1630.jpg). Accessed online: 25 September 2020.

Venice, for the most part, did not rely on makeshift structures when dealing with plague. As early as 1423, the city had established a permanent plague hospital, now known as the Lazzaretto Vecchio, followed by construction of the Lazzaretto Nuovo in 1471 – both located on islands in the lagoon. In 1457, a proposal advocated for the construction of tents on the Lido to provide an area to quarantine those suspected of carrying the plague. Yet, the measure did not move forward.Footnote 43 Rather, the Republic only resorted to temporary structures with the goal of expanding the capacity of existing institutions: in 1576, for example, employees of the Arsenale, the state shipyards, built a temporary extension to the Lazzaretto Nuovo to allow for more patients.Footnote 44

When it came to addressing an influx of paupers into the city, however, this provisional approach seems to have been the Republic's preferred response. Shelters similar to the cohopertum were built in peripheral areas of Venice in the sixteenth century as attempts to address severe famines that drove people from Venetian territories into the city.Footnote 45 During the great famine of 1527–28, private citizens rallied to create a shelter east of the church of Santi Giovanni e Paolo to support the wave of starving immigrants from the Republic's possessions on the mainland.Footnote 46 This shelter consisted of two structures described as ‘teze’, large wooden canopies likely similar to the cohopertum, to allow for separation of sexes, as well as a small wooden chapel for worship.Footnote 47 Known as the Ospedaletto, the long and narrow complex featured at least three wooden structures when the institution received its statutes and the official name of Santa Maria dei Derelitti in 1537. A temporary construction appeared again as a response to another emergency later in the century, when starving paupers flocked into the city as a result of poor harvests and ensuing famine. In 1594, the commissioners in charge of hospitals decided to build an institution to shelter these vagrants – the Ospedale dei Mendicanti, also near the church of Santi Giovanni e Paolo.Footnote 48 Prior to construction of the permanent fabric starting in 1601, however, temporary shelters and a wooden chapel were built to house and serve approximately 100 paupers.Footnote 49 No known evidence indicates the commission of similar shelters for beggars and paupers in the city prior to 1471, but documentation from the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries appears to demonstrate that, when dealing with a sudden increase in the numbers of paupers in the city, ephemeral architecture offered Venice a rapidly deployable solution. Despite limited historical records, it is possible that the cohopertum started this trend.

Venice's existing system of support

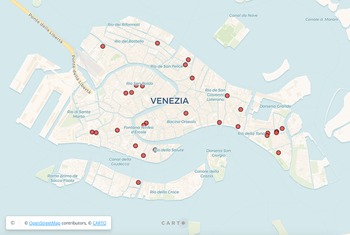

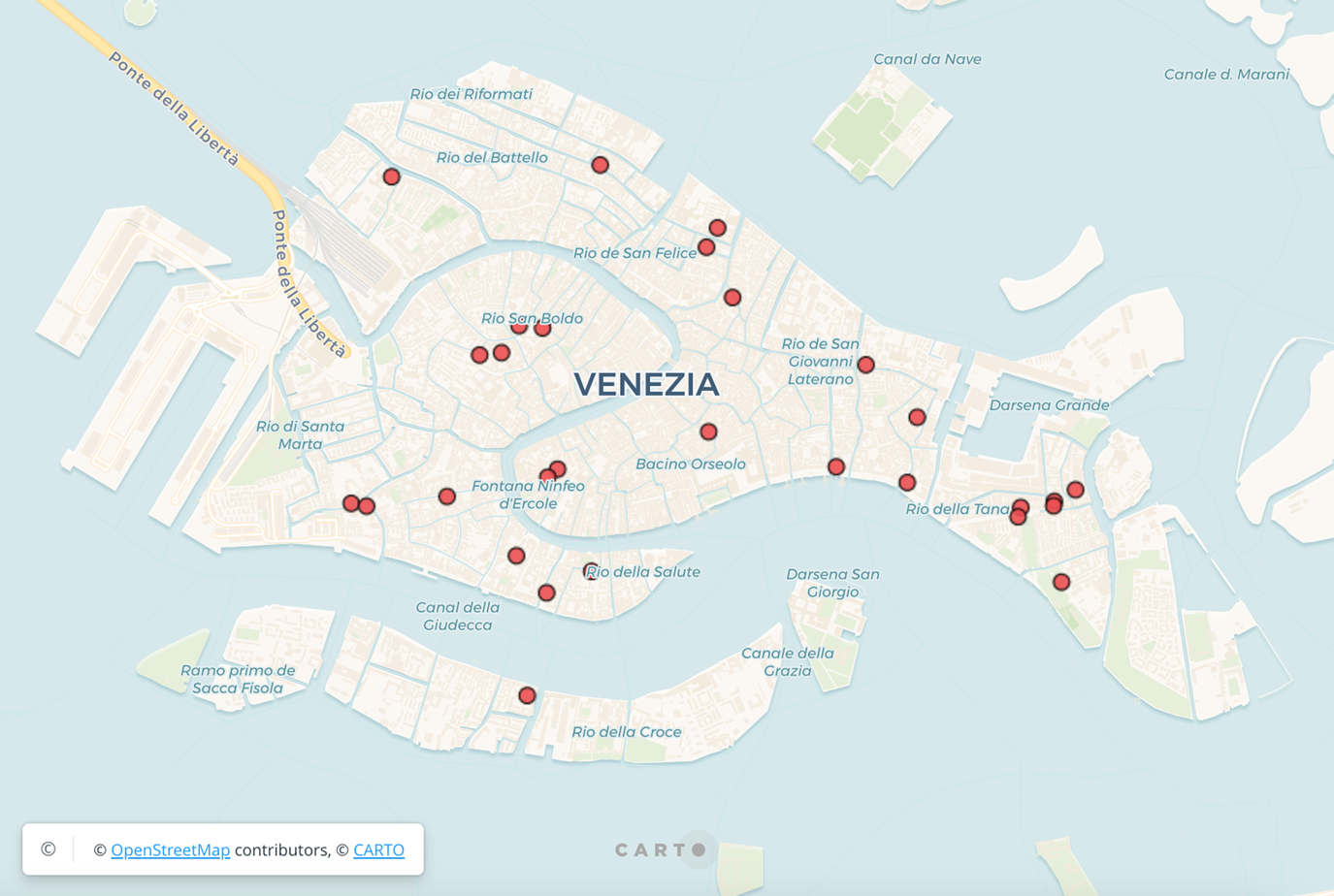

The need for the construction of temporary shelters suggests that Venice's charitable network in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries could not absorb a sudden increase in the number of paupers. But what was the state of this system prior to 1471, when the Venetian Senate addressed the poor migrants in the area of San Marco by commissioning the cohopertum? Records indicate that, in the early 1470s, the city had at least 42 hospitals, not counting isolation institutions on other islands, such as the Lazzaretto Vecchio and Nuovo for plague victims.Footnote 50 These establishments stemmed from the initiative of private donors, religious orders, confraternities, guilds and, less often, the state. Out of these institutions, the location of 29 ospedali can be identified, offering a glimpse into Venice's charitable network during this period (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Digital map showing 29 out of 42 hospitals that existed in Venice by 1471. Created by author.

Despite these 42 hospitals, until the late fifteenth century, Venice did not have a large-scale institution except for the foundling Ospedale della Pietà, which had been established in 1346 in the parish of San Giovanni in Bragora to house abandoned infants of both sexes.Footnote 51 Rather, the average size of a Venetian hospital allowed for 10 patients or residents, often widows or old men, arguably the most vulnerable groups of society after orphans and young women. Two institutions targeting the poor could each shelter approximately 20–50 paupers, while foreigners relied on ospedali designated for their particular communities, such as the two hospitals for Germans and an institution for Armenian immigrants. A 1497 report by the Milanese ambassador Battista Sfondrato confirms the limited scale of Venetian ospedali. Sfondrato recounted that Venice had small hospitals far away from each other and without much funding. Unimpressed, he remarked the lack of an institution as renowned as the Ospedale Maggiore (1456) in Milan, a general hospital designed to accommodate between 300 and 350 patients at a time and with over 2,000 admissions per year.Footnote 52

The Venetian government was certainly aware of this undesirable scenario and eventually established a commission in 1489 to survey the hospitals in the city. The commission's findings offer crucial insight into Venice's charitable crisis. Besides inspecting these institutions’ physical headquarters and finding them to be in precarious conditions, the commission also investigated testaments whose bequests had established hospitals in Venice. They reported that the majority of these institutions were ‘in poor condition and even decayed, which is an offence to God and to the honour of our state, on account of the complaints of the poor who are not receiving their dues as they ought, or in accordance with the bequests and instructions of testators’.Footnote 53 It is important to note that the Republic supervised but did not directly subsidize poor relief, relying instead on a decentralized system of private donations. However, it appears that those responsible for managing Venice's hospitals were neglecting their duties and appropriating funds, leading to the inefficiency of the city's charitable network.Footnote 54 Thus, the Republic not only lacked a large institution able to accommodate a sudden increase in the number of paupers, but the ones that existed were already ineffective in serving the local poor, explaining the need for the construction of temporary shelters.

The Venetian migrant crisis

It is no surprise, then, that the flood of immigrants into the city from Venetian territories in the east starting in the 1470s required an unusual public intervention in poor relief in the form of the cohopertum.Footnote 55 As mentioned in the introduction, this arrival of foreigners originated in the Republic's expansion in the Mediterranean.Footnote 56 Starting with the Fourth Crusade (1202–04), Venice began to acquire territories in the Aegean Sea, and following the conquest of Corfù in 1386, the Republic further advanced into the Ionian Sea, essentially controlling access to the Adriatic.Footnote 57 Together, the Dalmatian coast and the Greek mainland and islands formed what became known as Venetian Romania. Yet, Venice's dominance began to suffer serious challenges with the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottoman Turks in 1453 and the Republic's subsequent loss of several eastern territories during the First Ottoman–Venetian War (1463–79).

Beginning with the fall of Constantinople, migrants started to move from eastern to western Europe, initially targeting the Greek islands of Negroponte (present-day Euboea) and especially Crete.Footnote 58 However, Ottoman advances into Venetian territories, combined with social and economic instability, led to a second migratory wave – this time towards Venice itself. These migrations involved both voluntary migrants, whose homeland remained in Venetian possession, and refugees, whose birthplace fell under Ottoman control.Footnote 59 Migrants also came from throughout Venetian Romania, and this movement intensified in 1470 with the siege and subsequent loss of the important outpost of Negroponte in August of that year. Recent studies have demonstrated the difficulty in linking migratory movements towards Venice to specific events in the east, but the fact remains that, due to war and accompanying economic decline in its eastern territories, Venice saw a particularly significant influx of Greeks, Albanians and Dalmatians during this period.Footnote 60 Estimates indicate that, by the early sixteenth century, approximately 5,000–6,000 south-eastern European natives lived in the city.Footnote 61

Archival evidence from petitions and privileges suggests that both voluntary migrants and refugees had strong connections to their homeland as well as to Venetian political authority.Footnote 62 Subjects of the Republic, they often spoke non-Italian languages and could even adhere to different religious rites. They were not Venetian, but they were also not foreigners in the same sense as someone from France, Spain or even Florence. Their position as subjects of the Republic granted them legal status anywhere in the Venetian Empire, including Venice itself – a standing that allowed them access to courts, jobs, privileges and protection.Footnote 63 Although studies often present Venice as a thriving port city and therefore an ‘attractive’ destination to foreigners, in the case of refugees, these migrants had been under Venetian rule for decades and many simply found themselves without another option in the face of conflict and instability in the east, seeing Venice as a ‘centre’ to which they were naturally, and legally, connected.Footnote 64 Moreover, as Venetian subjects, these minorities must be understood within the structures, regulations and hierarchies of the Venetian Republic.Footnote 65 Considering historical parallels with current migrant crises and questions of accountability, Venice's own acknowledgement of responsibility for this influx of refugees into the city must be emphasized. This onus is evident in a Senatorial decree from 1479. Arguing that the Republic should be fair towards poor Albanians and their requests since they had been forced to leave their homeland, the Venetian Senate explained that aiding them made it so that ‘in the entire world our state could not be justly slandered’.Footnote 66 In question, then, was not only Venice's moral duty but also its status.

Yet, the influx of foreigners in the early 1470s raised both social and public health concerns. Socially, although some migrants could be well educated and possess financial resources, this migratory wave from Venetian colonies to Venice resulted in the arrival of many paupers, primarily single young men, in the city.Footnote 67 As refugees, they disembarked in Venice with little money or financial support from their families, in many cases having left behind whatever possessions they had.Footnote 68 Even if Venice restored relations with their homelands, now under new rulers, these migrants’ financial struggles made it difficult for them to return to or even visit their places of origin. Upon arrival, they not only faced several challenges, housing being the most critical, but their presence, presumably to stay, created social and economic tension with those already settled, whether Venetians or foreigners.Footnote 69

Further tension emerged due to concerns regarding the spread of disease. Richard Palmer has called attention to the fact that, since 1455, the Republic had kept a close watch on immigration from the Balkans due to the area's constant struggles with plague outbreaks.Footnote 70 A wave of migrants from Dalmatia in 1455 prompted the state to house them temporarily in a public warehouse located at the parish of San Biagio, while the sick were sent to the Lazzaretto Nuovo and provisions were arranged for those willing to leave Venice. A year later, the Senate determined that, as a result of the high numbers of migrants from Dalmatia and Albania, its measures to prevent plague remained inefficient. At that point, immigration was banned, with the Republic surveilling the Lido and other points of arrival for illegal migrants. The situation repeated itself in 1461, leading to similar measures. In 1478, a year marked by a particularly severe plague outbreak, this fear led the Republic to ship off to Istria the Albanian refugees dying of hunger under the porticoes of San Marco.Footnote 71 As these examples demonstrate, even if a particular wave of migration was not linked to outbreaks in other regions, public health likely factored into the Venetian decision to move paupers away from central urban areas.

Considering the cohopertum’s role

Whether for social or public health concerns, considering the remote location of the cohopertum, the Venetian government's choice to establish a shelter at the Punta di Sant'Antonio indeed suggests an attempt to isolate migrants from the central areas of Venice. Generally speaking, foreign presence in early modern cities materialized in two ways: through foreigners’ occupation of an urban space, as was the case with the migrants sleeping on Piazza San Marco, or through state intervention in the form of appointed or manufactured shelters to control minorities, as exemplified by Venice's creation of the cohopertum.Footnote 72 For the Republic, foreign presence required the Senate to produce space to accommodate these newcomers, often leading to their marginalization through placement outside of the city's already dense urban fabric.Footnote 73 This strategy fits with what Elisabeth Crouzet-Pavan has identified as the creation of a spatial hierarchy in fifteenth-century Venice, marked by the pushing to the periphery of activities such as shipbuilding, brick production, as well as of charitable institutions like confraternities and hospitals.Footnote 74 Since this urban transformation was linked to attempts to control and purify behaviour in certain spaces of Venice, particularly the central areas of Rialto, Venice's commercial centre, and Piazza San Marco, the religious and political headquarters of the city, scholarship discussing the cohopertum has tended to approach the issue of migrants by highlighting the undesirable presence of the poor in San Marco.Footnote 75 Yet, I argue that Venice had deeper social and military reasons for placing these immigrants at the Punta di Sant'Antonio – reasons that went beyond the Republic's anxieties over social decorum and public health.

Undeniably, the sudden arrival of a large number of refugees in Venice threatened the order of the city.Footnote 76 To prevent disorder, the Republic's best approach would be to incorporate these migrants into society as quickly as possible, and employment constituted one way to guarantee that transition.Footnote 77 In Venice, many eastern migrants would become domestic servants, hold public jobs as couriers or nightguards, work as craftsmen (i.e. bakers, barbers, etc.) or traders or serve in the Venetian army or navy.Footnote 78 Their integration could be facilitated by ‘national’ confraternities or scuole. For example, the Scuola of Santa Maria e di San Gallo degli Albanesi existed since 1442, assisting Albanians coming into Venice; Dalmatians counted on the Scuola of San Giorgio degli Schiavoni, established in 1451; and the Greek community received permission to establish its own confraternity in 1498.Footnote 79 While the presence of poor refugees in the area of Piazza San Marco indisputably posed a challenge to urban decorum for Venetian authorities eager to maintain the status of the city's most prominent civic space, migrants could be absorbed into Venice and its workforce.Footnote 80 The temporary shelter provided an immediate bridge.

The fact that housing presented one of the most difficult and expensive challenges faced by migrants in their new city further underscores the importance of the cohopertum.Footnote 81 In a recent study, Rosa Salzberg has called attention to Venice's ‘infrastructure of hospitality’, particularly the key role of stop-gap accommodations such as inns (osterie) and lodging houses (albergarie) as transitional spaces for newcomers who could afford those services.Footnote 82 For refugees with very limited or non-existent financial resources, few contacts and unable to access these types of accommodation as a result, the cohopertum offered a significant alternative. Yet, while osterie and albergarie clustered in the areas around San Marco and Rialto to better serve visitors, the position of the shelter at the remote area of Sant'Antonio might, once again, suggest an attempt at isolation rather than integration of these migrants. Once the location of the cohopertum is set in a more complex context, however, a contrasting picture emerges.

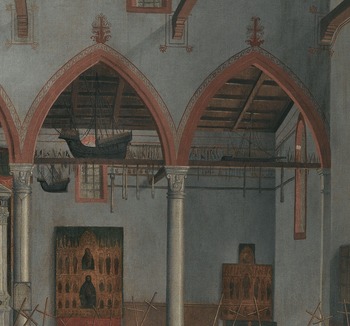

As discussed above, development of the Punta di Sant'Antonio had begun in the fourteenth century, but the parish of San Pietro di Castello, where the Punta is located, constituted an unusual area of the city with its own orientation focused on the Arsenale, the state shipyards first established in 1303, rather than Rialto and San Marco.Footnote 83 Due to the presence of industrial trades and resulting noise, the parish had historically failed to attract inhabitants. This scenario only began to change starting in the late 1400s, when the Ottoman threat led to the expansion of the state shipyards. Lured by the promise of secure work through military enrolment, a shipbuilding community began to develop in that remote area of the city.Footnote 84 The strong connection between the Arsenale and the parish only intensified in the following decades, as evident in Vittore Carpaccio's Apparition of the Crucified of Mount Ararat in the Church of Sant'Antonio di Castello (c. 1512) showing the interior of the now-destroyed church (Figure 7).Footnote 85 Visible under the church arcade and near the ceiling are models of ships and small flags, likely left on site by devotees as ex-votos. Significantly, the traditional cult of St Anthony of Vienna did not have any links to navigation. It was the location of the church of Sant'Antonio near the Arsenale that led to local veneration of the saint as the protector of navigation, evidence of the development of a strong geographical symbolism.Footnote 86

Figure 7. Vittore Carpaccio, Apparition of the Crucified of Mount Ararat in the Church of Sant'Antonio di Castello (detail), c. 1512. Courtesy of the Galleria dell'Accademia, Venice.

These devotees worked in the shipyards, forming a community known as arsenalotti, and served in the Venetian navy.Footnote 87 Since the mid-fourteenth century, the Republic had relied significantly on its eastern subjects, particularly Albanians, Dalmatians and Greeks, as manpower for its navy and shipyards.Footnote 88 In this period, Venice had difficulty staffing the Arsenale and its galleys since local Venetians were not interested in subjecting themselves to these heavy and exhausting jobs. While the Arsenale paid much less than private shipyards in the city, conditions aboard Venetian galleys could be grim, with most of the crew sleeping, working and eating on deck, inefficiently protected from extreme weather and the elements by a large canvas tent.Footnote 89 As a result, in the 1400s, the Arsenale community encompassed primarily foreigners, which explains the Senate's choice to place a shelter for refugees from those regions at the Punta di Sant'Antonio.Footnote 90 Aside from contact with compatriots, who might facilitate their transition into society, this geographical choice positioned these paupers in close proximity to the Arsenale. The latter, at that point, represented potential employment to men of any age.Footnote 91 A later Senatorial decision further supports this hypothesis: faced with another influx of Albanians following the loss of Scutari (present-day Shkoder, Albania) in 1479, the Senate mandated that a few archer positions in each galley be reserved for Albanian immigrants.Footnote 92 The shipmasters who disobeyed these orders would be fined. By placing these refugees in its shipyards and navy, the Republic would be using the same war that led to their arrival in Venice to facilitate their absorption into the urban and social fabric of the city. At the same time, the Republic would fulfil the needs of its military workforce, perhaps even taking strategic advantage of these migrants’ knowledge of their places of origin.

Conclusion

Since the Middle Ages, theologians believed that the souls of the rich were more vulnerable to damnation than those of the needy. According to contemporary belief, salvation of the wealthy depended on the poor since the prayers of the needy had the power to intercede for those privileged. This interdependence created what historian Dennis Romano has called a ‘symbiotic relationship’ between the rich and poor of Venice that was understood by contemporaries as highly influential in the maintenance of peace in the Venetian Republic.Footnote 93 If we consider the dispute with the Ottoman Turks in the east in this context, the disorder caused by the influx of immigrants into the city not only generated a social crisis surrounded by public health anxiety, but it also led to a religious predicament since Venice's existing charitable system was not able to adequately aid those in need. For Venetians, this social and, consequently, religious neglect could only result in divine punishment – war losses being one of many potential unfavourable outcomes.

If war represented divine punishment, charity toward the needy could secure divine favour during health, economic, or military crises. Documentary evidence from the period confirms this connection: at the founding of the Ospedale di Messer Gesù Cristo in 1503, for example, the Maggior Consiglio issued a decree stating that ‘the chief and most salutary means of obtaining divine favour for a state and republic…is the maintenance of the poor, in whom the person of Our Lord Jesus Christ is represented’.Footnote 94 Later into the sixteenth century, Venice's four main hospitals were referred to as the ‘bastions of the Republic’, once again stressing the crucial role of charity toward the needy in upholding the state.Footnote 95 As the war in the east progressed and Venetian possessions continued to be threatened, the commission of a temporary shelter at the Punta di Sant'Antonio for those dying of cold and hunger would ensure that divine favour fell on the Venetian side, justifying Venice's more active engagement with poor relief.

The initial decision of the Republic to build a cohopertum for the poor stemmed from a social emergency, and while the evidence associated with the shelter supports the independence of the cohopertum from the institutional and architectural history of the Ospedale di Messer Gesù Cristo, the choice to construct a temporary shelter at the Punta was not simply a spontaneous response to the arrival of immigrants in the city. Rather, the Venetian government had a multi-pronged mission. First, the Republic physically and visually removed beggars from the centre of the city, ensuring social decorum and isolating any potential health threats associated with the migrants. Second, the Venetian government relocated these refugees to an area where they would have temporary housing, find compatriots and perhaps hold a job at the Arsenale, potentially fulfilling the Republic's military needs. In this way, the modest structure of the cohopertum materialized the symbiotic relationship between the rich and poor of Venice. Addressing the charitable and religious components of what might appear to us today as clear-cut social pressure, the shelter belonged to a larger strategy to guarantee the maintenance and stability of the Venetian Empire through poor relief.