1. Introduction

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is a kind of megaregional arrangementFootnote 1 and profoundly affects the world in the twenty-first century.Footnote 2 BRI practice involves a highly complex network of agreements, ranging from memorandums of understanding (MOUs) to project contracts. The significance of BRI agreements cannot be ignored, with their many outcomes including infrastructure projects and new international mechanisms. BRI agreements are a hallmark of BRI practice, and carry profound implications for the future international economic order.

BRI agreements consist of BRI primary agreements and BRI secondary agreements. Primary agreements are non-binding instruments concluded by China and other governments and international organizations (other parties), which focus on the BRI. Of the 200 BRI documents concluded with 138 states and 30 international organizations,Footnote 3 the majority are primary agreements. Such a large number of non-binding instruments is unprecedented for China in international economic law practice. Primary agreements develop the framework for the BRI, and lay a foundation for secondary agreements implementing BRI projects. Secondary agreements include performance agreements to construct various projects (e.g., port and industrial projects) and underlying financing contracts.Footnote 4 Secondary agreements may also involve private parties such as the Public Private Partnership (PPP).

Understanding BRI agreements is thus crucial for exploring China's approach to international economic order. However, the nature and importance of primary agreements has to date not been fully explored. This paper bridges this gap by focusing on primary agreements and their close link with secondary agreements. It explores the following crucial questions: What are the legal status and characteristics of primary agreements? Why are they adopted by China? What challenges do they face? The paper proceeds as follows: Section 2 reviews the typology of BRI agreements, while Section 3 explores the legal status and characteristics of BRI primary agreements. It argues that while BRI primary agreements can be regarded as a form of soft law, they repurpose soft law characteristics for project development. Primary agreements have unique characteristics in terms of their legalization, substantive content, and structure. Section 4 argues that primary agreements benefit from the advantages of soft law to promote the BRI project, which explains why China selects primary agreements. The major challenges presented by primary agreements are explored in Section 5. Section 6 concludes with a discussion of potentially significant issues going forward. An annex, supplementary material, is included with a list of primary agreements.Footnote 5

Several points should be made here. First, this paper focuses largely on China's perspective particularly regarding the rationale for choosing primary agreements, due in part to word limit constraints and the huge variety of BRI jurisdictions. The pros and cons of primary agreements for other BRI jurisdictions, which are explored only briefly in this paper, necessitate separate country-specific analysis. Second, the BRI is understood in its broad sense under a functional approach, which focuses on the measures and mechanisms (including institutions) ‘put in place to serve the purposes of the BRI, regardless of whether they are externally labelled as part of the BRI’.Footnote 6

2. The Typology of BRI Agreements

2.1 BRI Primary Agreements

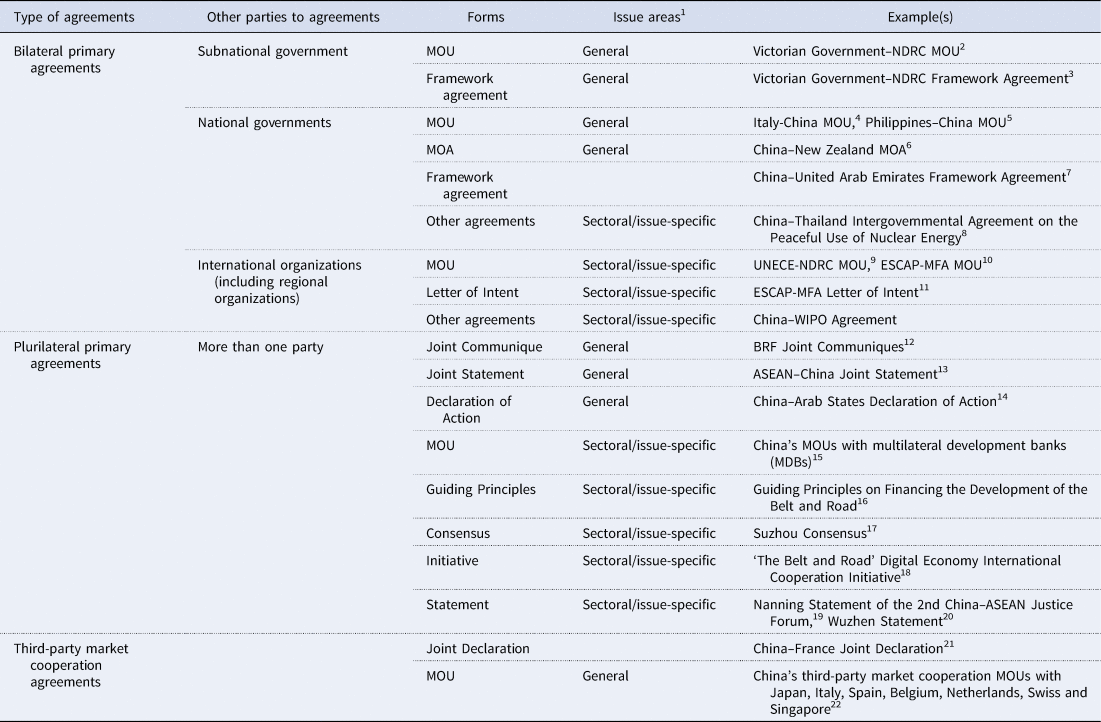

The categorization of BRI primary agreements is critical due to the large volume of agreements and their complexity. Table 1 provides a taxonomy of these agreements along the parameters of type, parties, form, and issue areas. For types and parties, there are bilateral and plurilateral agreements, depending on the number of other parties that conclude an agreement with China. A consideration of the primary agreements reveals several points. First, bilateral MOUs with other governments are the most common agreements, reflecting China's preference for informal bilateralism.Footnote 7 Second, primary agreements demonstrate China's increasing interactions with the UN. China has concluded BRI agreements with around 20 UN agencies,Footnote 8 including the UNECE-NDRC MOU as the first China–UN MOU.

Table 1. BRI primary agreements

1 The issue area has been identified based on the publicly available text (or, where the text is not available, the title) of the agreements in the examples at the time of writing. Where the text is not available, and the issue area cannot be determined from the title, this section has been left blank.

2 Memorandum of Understanding between the Government of the State of Victoria of Australia and the National Development and Reform Commission of the People's Republic of China on Cooperation within the Framework of the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road Initiative (2018), www.vic.gov.au/victorias-china-strategy (Victorian Government–NDRC MOU).

3 Framework Agreement between the Government of the State of Victoria of Australia and the National Development and Reform Commission of the People's Republic of China on Jointly Promoting the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road (2019), www.vic.gov.au/bri-framework (Victorian Government–NDRC Framework Agreement).

4 Memorandum of Understanding between the Government of the Italian Republic and the Government of the People's Republic of China on Cooperation within the Framework of the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road Initiative (2019) (Italy–China MOU).

5 Memorandum of Understanding between the Government of the Republic of the Philippines and the Government of the People's Republic of China on Cooperation on the Belt and Road Initiative (2018) (Philippines–China MOU).

6 Memorandum of Arrangement on Strengthening Cooperation on the Belt and Road Initiative between the Government of the People's Republic of China and the Government of New Zealand (2017) (China–New Zealand MOA).

7 This Agreement does not refer directly to the BRI, but is listed as a deliverable of the BRI Forum. China.org.cn, Full Text: List of Deliverables of the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation (2017), www.china.org.cn/chinese/2017-06/07/content_40983146.htm.

8 China.org.cn, Full Text: List of Deliverables of the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation (2017), www.china.org.cn/chinese/2017-06/07/content_40983146.htm.

9 Memorandum of Understanding between the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe and the National Development and Reform Commission of China (2017) (UNECE-NDRC MOU).

10 Memorandum of Understanding between the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China on the Belt and Road Initiative for the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (2019) (ESCAP-MFA MOU).

11 Letter of Intent between the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, People's Republic of China on Promoting Regional Connectivity and the Belt and Road Initiative (2016) (ESCAP-MFA Letter of Intent).

12 Joint Communique of the Leaders Roundtable of the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation (2017); Joint Communique of the Leaders’ Roundtable of the 2nd Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation (2019).

13 ASEAN–China Joint Statement on Synergising the Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity (MPAC) 2025 and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) (2019).

14 Declaration of Action on China–Arab States Cooperation under the Belt and Road Initiative (2018) (China–Arab States Declaration of Action).

15 Memorandum of Understanding on Collaboration on Matters of Common Interest Under the Belt and Road Initiative (2017), www.ndb.int/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/MOU-on-BRI-signed.pdf; Memoranda of Understanding on Collaboration on Matters to Establish the Multilateral Cooperation Center for Development Finance (2019), www.aiib.org/en/about-aiib/who-we-are/partnership/_download/collaboration-on-matters.pdf.

16 Guiding Principles on Financing the Development of the Belt and Road (2017), www.mof.gov.cn/zhengwuxinxi/caizhengxinwen/202007/t20200724_3555773.htm.

17 Suzhou Consensus of the Conference of Presidents of Supreme Courts of China and Central and Eastern European Countries (2017), www.sohu.com/a/73518080_117927 (Suzhou Consensus).

18 ‘The Belt and Road’ Digital Economy International Cooperation Initiative (2017), http://finance.jrj.com.cn/tech/2017/12/04073823734129.shtml.

19 Nanning Statement of the 2nd China–ASEAN Justice Forum (2017), www.chinajusticeobserver.com/p/nanning-statement-of-the-2nd-china-asean-justice-forum.

20 Wuzhen Statement (2019), www.chinatax.gov.cn/eng/n4260859/c5112273/5112273/files/a6466929ab654fbf842d982b0906442e.pdf.

21 Joint Declaration between the People's Republic of China and the French Republic (2018), para. 15 (‘the Joint Declaration between China and France on the partnerships in third-party markets of June 2015’), https://eng.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/zchj/sbwj/43581.htm.

22 Zheng, ‘The Significance, Practices and Prospect of China's Third-Market Cooperation’, 78.

Regarding form, agreements include MOUs, the Memorandum of Arrangement (MOA), (framework) agreements, joint communiques and statements, guiding principles, and consensuses. One form of an agreement may be used to deepen the engagement initiated under another form. For instance, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) first signed a three-year Letter of Intent with the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP),Footnote 9 followed by a MOU which China has suggested further deepens the engagement.Footnote 10

Concerning coverage, primary agreements address highly diverse subject matters, including ‘joint transportation infrastructure development, joint set-up of industrial parks, establishment of sister-city networks, trade and investment promotion, financial cooperation (such as strategic cooperation with the Asia Infrastructure and Investment Bank, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB)) or the joint collaboration in regional initiatives’,Footnote 11 and the digital economy. Some forms, such as framework agreements and MOAs, tend to cover general issues and work to develop a general framework.Footnote 12 Other forms, including intergovernmental agreements and guiding principles, address issues that are more specific. These issues, including energy, finance, and dispute settlement, are often those prioritized by China or reflect the focus area of the international organization party to the agreement (e.g., intellectual property in the China–World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) AgreementFootnote 13). The distinction between general and specific coverage is not, however, absolute. MOUs, for example, have been used to address both general and specific issues.

Notably, third-party market cooperation agreements, which are usually concluded between China and advanced economies, are often considered as BRI agreements.Footnote 14 Dongchao Zheng argues that third-party market cooperation arrangements are concerned with using China's production capacity and developed countries’ advanced technology to explore the markets of developing countries (the third-party market).Footnote 15 At the time of writing, China has signed third-party market cooperation documents with 14 states.Footnote 16

Overall, primary agreements are heterogenous and address wide-ranging domains. They cross different spheres of international law, including trade, finance, investment, environment, and labor.

2.2 BRI Secondary Agreements

Secondary agreements are agreements to implement BRI projects, and sit under top-level primary agreements. Secondary agreements are often hard law agreements. Patrick M. Norton has identified that ‘[m]ost BRI projects will be initiated by, and conducted under the auspices of, inter-governmental agreements between the Chinese and host country governments’.Footnote 17 One primary agreement also explicitly provides for the ‘[e]xecution of a separate legal instrument between the parties to define and implement any subsequent activities, projects and programmes’.Footnote 18 Primary agreements are thus likely to have substantial effects on secondary agreements, and in this way contribute to the final output of binding agreements. It is not easy to identify all secondary agreements, since the parameters for ‘BRI projects’ are often unclear,Footnote 19 and these agreements are usually not publicly available and less visible.

Secondary agreements consist of at least two categories of agreements, and may involve multiple contracts between the various bodies involved in a project.Footnote 20 One category is performance agreements, including performance guarantees, economic stabilization contracts, land usage contracts,Footnote 21 and concessions agreements that may involve exclusive concession rights (e.g., a build-own-operate-transfer concession).Footnote 22 The other category is finance agreements, including loan agreements and grant agreements.Footnote 23 They could involve China's banks and MDBs. Secondary agreements can be subject to domestic and international commercial legal scrutiny (such as in arbitration or adjudication). Many secondary agreements could be government-to-government directly or indirectly, business-to-business, or government-to-business. Various state-owned enterprises are involved in secondary agreements.

Secondary agreements are complex. They often have a long duration and several contract layers, and involve multiple parties from multiple jurisdictions, due to the nature of infrastructural projects.Footnote 24 Secondary agreements often involve large infrastructure projects ranging from portsFootnote 25 to railways,Footnote 26 which carry long-term distributive effects. They may be used to address many issues such as legal risks in investment ranging from political unrest, project delays, and cost overruns due to project abandonment.Footnote 27

Governments play an important role in secondary agreements, with the exact nature of this role often determined by the type of infrastructure involved. Differing from traditional international commercial contracts (e.g., sales contract), secondary agreements are often based on the direct or indirect support of the governments (host country, home country, or both) in funding, concession, and other aspects like dispute settlement. For instance, China's Vice Foreign Minister Le Yucheng has stated that ‘[t]he BRI cooperation agreements we have signed with various countries include provisions that the host countries will take up the security responsibility’.Footnote 28 Host governments could be a party to secondary agreements (such as ‘collateral government agreements’, which include performance guarantees, and agreements on economic stabilization and land usage), and the ‘highly political context of many BRI projects’ means that their disputes are likely to be submitted to ‘informal government-to-government discussion’.Footnote 29

Secondary agreements should be considered alongside primary agreements in understanding the complex structure of the BRI holistically. Primary agreements not only have legal implications but could also send political signals to domestic actors that the BRI is acceptable in host states, and thus advance a ‘hardening’ of the arrangements through secondary agreements. The coordination with other parties through primary agreements also helps to address complex issues arising in secondary agreements, including project-specific issues (e.g., energy-related) and general issues (e.g., funding, dispute settlement).

3. The Legal Status and Characteristics of BRI Primary Agreements

A rigid dichotomy between legalization and politics may not fully explain international agreements.Footnote 30 The legal status of BRI primary agreements is likely not the most important factor from the perspective of actors. Rather than an instrument's true legal status, legal considerations (e.g., ‘rules of sovereignty and other background legal norms’) work alongside political considerations to influence behavior.Footnote 31

On the one hand, primary agreements are similar to currently recognized forms of soft law which live in the ‘twilight’ between law and politics.Footnote 32 In this paper, soft law refers to quasi-legal obligations or law-like promises that are not legally binding but may affect state behavior. Despite different definitions of soft law, soft law is generally regarded as ‘norms that are neither law, nor mere political or moral statements, but lie somewhere in between’.Footnote 33 Soft law involves written international instruments containing hortatory rather than legally binding obligations,Footnote 34 and includes ‘nonbinding standards, principles, and rules that influence and shape state behaviour’.Footnote 35 Essentially, soft law is ‘law-like promises or statements that fall short of hard law’.Footnote 36

BRI primary agreements can be regarded as soft law because they provide for certain quasi-legal obligations or law-like promises. To illustrate, plurilateral primary agreements to some extent resemble the G20 Leaders’ Statement,Footnote 37 which forms part of the legislative products (like communiques and declarations) of the G20, a regulatory and political medium.Footnote 38 To a degree, bilateral primary agreements may display traits resembling the coordination under early bilateral investment treaties (BITs) of capital-exporting countries.Footnote 39 Various BRI primary agreements provide for enhanced policy coordinationFootnote 40 generally (such as calling for regulatory harmonizationFootnote 41) or specifically regarding prioritized issues including currency (e.g., the use of local currencies in investment and tradeFootnote 42), dispute settlement (e.g., the presumption of reciprocity regarding the recognition and enforcement of civil and commercial judgments,Footnote 43 and the use of mediationFootnote 44) and internet (e.g., the call for the ‘full respect’ of cyberspace sovereigntyFootnote 45). Many primary agreements have a similar basic structure and are linked to pre-existing legal platforms (e.g., the China–New Zealand Free Trade AgreementFootnote 46).Footnote 47 The basic structure highlights policy coordination as one of five major areas under the BRI,Footnote 48 which is also a top priority of the BRI.Footnote 49 As another example, one primary agreement provides that the implementation of its subsequent activities ‘shall necessitate the [e]xecution of appropriate separate legal instruments’ between the parties to whose terms ‘shall be read in parallel with’ the primary agreement.Footnote 50 These factors together help explain why BRI MOUs in particular are often defined as soft law,Footnote 51 and why primary agreements are regarded as ‘a quasi-legal instrument that doesn't carry any legally binding force, or whose legally binding force is weaker than that of traditional laws and regulations’.Footnote 52

On the other hand, BRI primary agreements differ from existing soft law in terms of their legalization, substantive content, and structure, all of which will be discussed below in light of the legal–political continuum. BRI primary agreements largely emphasize project development, in contrast with many existing soft law instruments (like those in international financial law) that promote rule development. This is reflected in the substantive content of primary agreements (as discussed below).

3.1 Legalization: Minimal Legalization

Legalization is a useful way of assessing the soft or hard legal character of instruments, and it can be defined along three dimensions: obligation (states or others constrained by norms or commitments with their behavior subject to scrutiny), rule precision (clearly defined rules on state behavior), and delegation (third parties authorized to implement, interpret, apply, and even develop norms, including dispute resolution).Footnote 53

Compared with existing soft law in these dimensions, most primary agreements are minimally legalized (aspirational, not precise, with weak institutionalization).Footnote 54 Primary agreements are weak across all three of these dimensions, while existing soft law is generally stronger in respect of one or more dimensions. Primary agreements feature softer legalization and a higher level of generality (e.g., heavy reliance on general statements).

First, primary agreements have low degrees of obligation and weak obligatory force. BRI primary agreements often explicitly indicate that they are not binding,Footnote 55 and their provisions are usually hortatory (e.g., ‘endeavour to’Footnote 56). The lowest level of obligation is to ‘explicitly negate any intent to create legal obligations’, such as ‘Non-Legally Binding Authoritative Statement of Principles for a Global Consensus’ and the 1975 Helsinki Final Act that indicated it was not an ‘agreement … governed by international law’.Footnote 57 Notably, the Italy–China MOU indicates that it ‘does not constitute an international agreement which may lead to rights and obligations under international law’, and none of its provisions ‘is to be understood and performed as a legal or financial obligation or commitment of the parties’.Footnote 58

The low level of obligation is also reflected in the forms of primary agreements. Their forms range from statements to guidelines that are usually ‘intended not to create legally binding obligations’.Footnote 59

However, a small number of primary agreements that develop new plurilateral mechanisms (e.g., the Multilateral Cooperation Center for Development Finance (MCDF) and the Belt and Road Initiative Tax Administration Cooperation Mechanism (BRITACOM)) reflect a higher degree of obligation. China's 2017 MOU with six MDBs is observed to reveal ‘a serious level of commitment’ (including the plan to develop the MCDF),Footnote 60 followed by another MOU to establish the MCDF. These MOUs on the MCDF and BRITACOM use the term ‘shall’ regarding certain obligations,Footnote 61 contrasting with other primary agreements that use the word ‘should’.Footnote 62 Moreover, the termination of certain BRI primary agreements requires ‘joint agreement,’Footnote 63 arguably introducing some constraints.

Second, primary agreements usually do not delegate legal authority, unlike some, although not all, existing soft law instruments. Primary agreements do not have ‘the characteristic forms of legal delegation’, involving third-party adjudication to interpret and apply rules as per established international law doctrines.Footnote 64 Neither do they designate third parties (e.g., international organizations, courtsFootnote 65) to implement the agreements (such as general principles in the agreements). Primary agreements prefer diplomacy. For instance, the Italy–China Government Committee will ‘monitor progress’ of the Italy–China MOU and the differences in the MOU interpretation will be settled amicably through consultations.Footnote 66 China appears to prefer avoiding treaties with measurable compliance requirements in favor of less formal but more flexible arrangements.Footnote 67 Essentially, primary agreements are not linked to an institutional framework with independent authority.

Third, primary agreements generally have a lower level of precision than existing soft law, and this echoes China's preference of ‘broadness is better than concreteness’ in legislation.Footnote 68 Although soft law often features imprecise rules,Footnote 69 many soft law instruments (e.g., the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development and Agenda 21) are ‘remarkably precise and dense’, which ‘enhance[s] their normative and political value’ from the perspective of proponents.Footnote 70 Primary agreements adopt general principles and sometimes standards, rather than the prescriptive terms and technocratic characteristics often found in existing soft law (e.g., international financial law instruments that spell out best practicesFootnote 71). For primary agreements, their principles are observed to be ‘laissez fair’ and ‘minimal … which is descriptive more of the parameters within which the arrangement is to proceed and be cemented, as opposed to articulating a positive vision of a development strategy as such’.Footnote 72 Moreover, primary agreements lack specific procedures on further negotiations. Many primary agreements do not provide for concrete measures and instead contain ‘pronouncements more along the lines of ideal outcomes’.Footnote 73 It is observed that primary agreements are a ‘vague’ form of governance.Footnote 74

Certain rules of a small number of primary agreements are, however, precise, which mainly involve the roadmap and steps to promote projects. The Victorian Government–NDRC Framework Agreement, signed in October 2019, provides that the draft work plan will be formulated by the end of March 2020 and both parties ‘agree to work towards having an agreed Cooperation Road Map on key areas by first half of 2020, with a view to having the joint chairs to sign’.Footnote 75 The China–New Zealand MOA provides for ‘a more detailed work plan’ to be formulated within 18 months of the MOA entering into force.Footnote 76 The Victorian Government–NDRC Framework Agreement provides for detailed rules on their working mechanisms (Working Group with a Secretariat), which is more developed than those under China's free trade agreements (FTAs) that usually do not have a secretariat.Footnote 77 It also provides for detailed rules on the steps on how to promote infrastructure projects (such as possibly ‘a joint Infrastructure Accelerator’).Footnote 78

The degree of legalization of primary agreements however varies particularly according to the parties and purposes of the agreements. Concerning parties, primary agreements with developed countries (like the Italy–China MOU) and international organizations appear to slowly integrate more legalized provisions relative to those with developing countries. Concerning purposes, agreements that create plurilateral mechanisms appear to be of a higher level of legalization than other primary agreements, likely due to operational needs. As a typical example, the BRITACOM MOU contains 36 articles over 20 pages, and its rules are much more detailed than other primary agreements.

3.2 Substantive Content: Coordinated and Project-Based Nature

Substantive content is a characteristic distinct from legalization.Footnote 79 While existing soft law often establishes international regulatory standards,Footnote 80 BRI primary agreements feature a more project-based focus. Further, although this project-based focus can be seen elsewhere in international law (e.g., soft law in the context of the international space projectFootnote 81), they are neither as coordinated nor of the same scale and extent as the BRI primary agreements. BRI primary agreements combine a project-based nature with coordination not seen in existing soft law (e.g., a large number of primary agreements, and BRI MOU template drafted by ChinaFootnote 82). In this way, primary agreements adopt many of the features of soft law, but direct these towards supporting BRI projects rather than rule development.

3.2.1 Project-Linked Agreements and Mechanism-Creating Agreements

Primary agreements consist of two categories. The first category is ‘project-linked agreements’ that focus on project promotion. These agreements are often (i) bilateral primary agreements with other governments, (ii) plurilateral agreements with a group of states, or (iii) third-party market cooperation agreements.

Primary agreements (particularly MOUs) are often expressly project-specificFootnote 83: they feature ‘a focus on pushing forward important areas and major projects’,Footnote 84 aim to ‘jointly ensure sound and smooth operation’ of major projects,Footnote 85 and ‘strive to promote the smooth progress of their cooperation projects’.Footnote 86 For instance, third-party market cooperation agreements aim at exploring projects in third states along the BRI.Footnote 87 BRI MOUs often provide for cross-border and regional initiatives with mid- and long-term development plans involving projects.Footnote 88 The Victorian Government–NDRC Framework Agreement goes further as most of its rules focus on project promotion (e.g., working mechanism, major areas, and steps to promote infrastructure projects, and roadmap developmentFootnote 89).

Primary agreements could lead to project plans that are more detailed. They may require a roadmap in a short timeFootnote 90 and the roadmap needs to be ‘faithfully implement[ed]’.Footnote 91 As one example, the guidelines of G16+1 summits have developed from listing planned symposia to covering increasingly concrete plans (the building of Serbo–Hungarian railway connections), and mechanisms (e.g., the conclusion of the framework agreement on customs clearance facilitation between China, Hungary, Serbia, and Macedonia, and the participation of financial institutions of the Central and Eastern European Countries in the RMB Cross-border Inter-bank Payment System).Footnote 92

Most BRI projects will be developed under the auspices of inter-governmental agreements.Footnote 93 The BRI relies on specific projects and related practices: MOUs will first be signed between governments, followed by contracts signed between participating businesses (participating firms may also conclude contracts with local governments).Footnote 94 To illustrate, the China/Pakistan Economic Corridor was launched in 2013, through the MOU between China and Pakistan, and involves a Chinese investment of some $45 billion into Pakistan.Footnote 95 Different Chinese and Pakistani organizations have concluded various agreements.Footnote 96 Relatedly, a BRI primary agreement may support existing projects (e.g., infrastructure projects).Footnote 97

This reflects the BRI's ‘result-oriented and progress-oriented’ nature.Footnote 98 China emphasizes the need to ‘transform leaders’ political consensus into execution for specific projects.’Footnote 99 The BRI appears to be transitioning ‘from making high-level plans to intensive and meticulous implementation’,Footnote 100 although the outcome remains to be seen.

The other category of primary agreements is ‘mechanism-creating agreements’. Primary agreements may lead to new formal and informal mechanisms, which could help to promote projects directly or indirectly through addressing selected issues behind the projects. Mechanism-creating agreements are usually bilateral agreements with international organizations and other plurilateral agreements. These mechanisms range from RMB clearing centers and economic zones,Footnote 101 to a multilateral dialogue mechanism on PPP.Footnote 102 Some agreements (e.g., the BRITACOM MOU and the MOU for the establishment of the MCDFFootnote 103) are devoted to establishing mechanisms.

There could be overlap between project-linked agreements and mechanism-creating agreements. The Victorian Government-NDRC Framework Agreement is an example. It not only promotes projects but also provides for detailed working mechanisms (Working Group with a Secretariat), which arguably are more developed than those under China's FTAs, which usually do not have a Secretariat.Footnote 104

3.2.2 Incongruence with Existing Soft Law Classification

Primary agreements promote projects directly through project-linked agreements, and indirectly through mechanism-creating agreements. The existing soft law categories (as discussed below) focus instead on rule development, problematizing primary agreements’ placement within these categories.

Existing soft law (which is defined in terms of the distinction from hard law rather than on its own terms, with a presumption that it is desirable for soft law to transform into hard law) consists of: (i) elaborative soft law, guiding the interpretation or application of hard law (‘soft law which builds from hard law’); (ii) emergent hard law, aiming to negotiate a subsequent treaty through ‘piloting’, or evolving into binding custom through state practice and opinio juris (‘soft law which builds to hard law’); (iii) soft law evidencing the existence of hard obligations (‘soft law which builds to hard customary international law’); and (iv) parallel soft and hard law, similar provisions articulated in hard and soft forms with the soft one acting as ‘a fall-back provision’ (‘co-regulation’), and (v) soft law being a source of obligation, ‘through acquiescence and estoppel, perhaps against the original intentions of the parties’.Footnote 105

Primary agreements do not fit in these categories. At this stage, primary agreements do not elaborate on existing treaties as ‘soft law which builds from hard law’, and do not involve international tribunals with authority to interpret international rules. They contrast with the judgments of international courts (e.g., the WTO dispute settlement system, and the International Court of Justice) and the resolutions of international organizations (e.g., the United Nations General Assembly Resolution on Measures to Eliminate International Terrorism, which relates to the details of the Refugee Convention).Footnote 106

Primary agreements usually do not endeavor to negotiate a treaty through piloting as ‘soft law which builds to hard law’. There is no plan for a BRI-wide treaty. It is difficult for primary agreements per se to evidence the existence of hard obligations as ‘soft law which builds to hard customary international law’. This is partially attributable to primary agreements’ high level of generality. Most primary agreements per se will continue to operate ‘on [their] own terms’,Footnote 107 and have made limited progress in making new regulatory disciplines.

In the same vein, primary agreements are too general to be a fallback version if hard law (like the WTO rules) does not function. Primary agreements themselves can hardly be a source of obligation given their vague terms, which arguably resemble a kind of ‘incomplete contract’. That said, BRI primary agreements are not just political statements: they provide for quasi-legal obligations, and support secondary agreements that contain the binding obligations. Instead of engaging in rule development, as occurs under many existing soft law instruments, primary agreements adopt a coordinated and project-based nature.

3.3 Structure: Hub-and-Spoke Network

Primary agreements are special in forming a hub-and-spoke network with China as the hub. They create a centralized network that consists of multi-layer agreements (primary and secondary agreements). To illustrate, a number of bilateral agreements could be concluded between China and another state. The Italy–China MOU is complemented by 19 other agreements on specific issue areas ranging from culture, sport, energy, to finance and infrastructure.Footnote 108 As another example, over 51 MOUs have been signed between China and Pakistan,Footnote 109 which may include secondary agreements.

Primary agreements are all signed with China and usually focus on the BRI. BRI primary agreements ‘set the stage’ for a new extra-regional governance on selected issues (e.g., infrastructure, finance, and internet) in which China plays the leading role.Footnote 110 It is observed that the China emphasizes negotiating and signing general cooperation agreements with developing states along the BRI's trade routes.Footnote 111

China drafts the BRI MOU template, and establishes the framework for future negotiations and for new international governance.Footnote 112 BRI primary agreements sometimes use a kind of ‘boilerplate language’ (e.g., ‘similar standardized terms’), which is to some extent similar to the coordination under early BITs that excluded investor–state dispute settlement.Footnote 113 For instance, BRI bilateral MOUs usually provide for the parties’ ‘understanding’ of five priorities (i.e., policy coordination, facilities connectivity, unimpeded trade, financial integration, people-to-people bonds).Footnote 114 The prioritized areas under the Italy–China MOU also largely respond to the priorities in the BRI vision issued by China.Footnote 115 China aims to enhance the ‘“soft connectivity” of the Belt and Road regulations and standards’,Footnote 116 with laws, regulations, and policies all identified as part of this ‘software connectivity’.Footnote 117 This could involve the alignment of laws and policies in areas like transport facilitation and paperless trade, and the harmonization of select technical standards, shipping documents and rules.Footnote 118 Relatedly, the UNECE–NDRC MOU also aims to assist BRI states to ‘[e]stablish a sound PPP legal, regulatory and governance framework to attract investment in infrastructure projects’.Footnote 119

Taken as a whole, both the volume of primary agreements and China's leading role across the agreements differentiate them from existing soft law China has been involved in (like China's MOUs with the EU and US on antitrust cooperationFootnote 120). Various primary agreements appear to promote China-preferred ‘software’ (e.g., China-led mechanisms, China's standards and experienceFootnote 121 through projects), and ‘hardware’ (e.g., strengthening the synergy between other countries’ infrastructure and the BRIFootnote 122). Primary agreements also differ from soft law approaches in international financial law that relies on ‘a network of international organizations (i.e. such “transnational regulatory networks” as the Bank of International Settlement and Financial Stability Board)’.Footnote 123

3.4 Summary

While many prior observations on soft law are relevant in analyzing primary agreements, their different attributes need to be considered. For instance, the precision of primary agreements centers on project-related aspects and mechanism development to promote projects. This contrasts with rule development under existing soft law and broadly much of international law that is ‘quite precise’.Footnote 124

It is useful to understand primary agreements as sitting on the legal-political continuum instead of under a rigid dichotomy between legalization and politics. As observed by Kal Raustiala, ‘[t]hat many nonbinding commitments ultimately influence state behavior illustrates the complexity of world politics, not the legal character of those commitment’.Footnote 125 It is observed that ‘law is a continuation of political intercourse, with the addition of other means’.Footnote 126 The full text of many primary agreements is not publicly available, and huge varieties among BRI primary agreement exist in terms of their form, context, and content. Specific primary agreements and their implementation need to be analyzed on a case-by-case basis.

4. Why Does China Adopt BRI Primary Agreements?

BRI primary agreements currently draw on soft law but adopt a focus on project development over rule development, unlike under existing soft law. In general, primary agreements have benefitted substantially from the advantages of soft law, and as such existing soft law analysis is largely applicable to the BRI primary agreements. These advantages include lower contracting costs and flexibility, which help China to build the framework of the BRI. Primary agreements may also help raise the legitimacy of the BRI. All these advantages correspond with China's pragmatic interest in promoting the BRI and enhancing China's role in international governance.

Furthermore, the repurposing of soft law characteristics in BRI primary agreements may be explained by China's current priorities. Existing soft law (such as international financial law) is often led by advanced economies with an aim to develop new and often detailed regulatory disciplines. China, meanwhile, currently displays a priority for project development over the development of detailed regulatory disciplines. Therefore, the formation of agreements falling with existing soft law definitions would not meet China's preferences or initiate the BRI projects in a short time. Instead, by utilizing many of the characteristics of soft law but directing these towards project development, BRI primary agreements enable China to benefit both from the advantages of soft law while also developing the BRI.

Relatedly, there could be various reasons for other parties to conclude primary agreements. They include low contracting costs (due to minimal legalization of primary agreements), possible first-mover advantages (to join the BRI as a new network), potential access to funding regarding infrastructure, and possible geopolitical considerations. For instance, primary agreements do not require binding commitments, which arguably ‘reduce the fear of the BRI countries that, given the power asymmetry between them and China, as well as, the uncertainty about China's intention and future’.Footnote 127 Given the huge variety of other parties, the reasons for concluding primary agreements need to be analyzed on a case-by-case basis. The following section will focus on China's perspective, but many reasons below (e.g., reduced contracting costs) may also apply to other parties depending on the context.

4.1 Reduced Contracting Costs

It is much easier to conclude primary agreements compared with, for example, concluding a treaty. BRI primary agreements are thus similar to soft law in that they work to reduce contracting costs (including the large number of parties, domestic ratification process, and sensitive issues,Footnote 128 possibly reducing ‘the transactions costs of continual bargaining’Footnote 129) and therefore can be concluded quickly.Footnote 130 A number of short primary agreements could be concluded with other parties, as a series of shorter instruments ‘avoid … the bargaining costs associated with a single, long agreement’.Footnote 131 China may not wish to introduce detailed rules into primary agreements as this could delay the initiation of the BRI.Footnote 132 The BRI is project-oriented and starts with MOUs, which correspond with China's tradition of ‘[h]e who wants to accomplish a big and difficult undertaking should start with easier things first’.Footnote 133

Primary agreements take advantage of the elements of soft law instruments to address sensitive issues, since the BRI often involves national interests and sensitivity. Soft law can be used to address the situation when ‘norms are contested and concerns for sovereign autonomy are strong, making higher levels of obligation, precision, or delegation unacceptable’.Footnote 134 For sensitive issues, soft law imposes lower ‘sovereignty costs’, and also permits the parties to be more ambitious and conduct ‘deeper’ cooperation than they would if they had to be concerned about enforcement.Footnote 135 Soft law arguably represents ‘a somewhat less serious pledge of a state's reputational capital’.Footnote 136 BRI primary agreements are highly vague and not subject to enforcement. The parties to the MOU could theoretically ‘moderate and modulate their level of commitment’ through soft law, limiting their obligation via the designation of their undertakings as non-binding, ‘hortatory language, exceptions, reservations and the like’.Footnote 137

4.2 Flexibility

Primary agreements allow for maximized flexibility, which is a key characteristic underpinning China's BRI approach.Footnote 138 Maximized flexibility arises from minimal legalization in terms of obligation, precision, and delegation. For instance, China retains more latitude through primary agreements with conditional language. For powerful states, ‘loosening their own constraints is often more important than having others tightly constrained’, and this brings ‘greater latitude in application’.Footnote 139 It is observed that powerful states often do not want to be obligated and have ‘less need for legalization’.Footnote 140

First, flexibility is desirable since China has not fully determined what is in its best interests in respect of many issues (particularly in new areas like digital trade). To illustrate, data localization requirements may not necessarily work for the benefits of Chinese businesses operating overseas as they would increase costs.Footnote 141 More broadly, the BRI is an unprecedented extra-regional initiative. It is also affected by geopolitical and other dynamics (e.g., COVID-19 outbreakFootnote 142). Views and policies regarding the BRI are, to a certain extent, in flux. As with soft law, primary agreements will often be preferable if states’ interests are less clear.Footnote 143 The recourse to soft law occurs when states are not sure the norms they adopt will be desirable in the future.Footnote 144 If the focuses and priorities of the BRI change, primary agreements may change. It is much easier to change soft law instruments than hard law, in part due to the imprecise terms.Footnote 145 Such flexibility allows time for China to ascertain its interests, and accordingly promote the BRI projects step by step.

Second, primary agreements enable China to learn by practice and allow trial-and-error in the BRI design and implementation. China is comparatively less experienced in addressing global affairs than major Western states (particularly the US), and needs to learn in the international arena.Footnote 146 Primary agreements benefit from the advantages of soft law in terms of flexibility in responding to political dynamics and informality.Footnote 147 Primary agreements also increase the elasticity of China in addressing the difficulty of building BRI projects.Footnote 148

Third, primary agreements provide flexibility to China in securing broad participation in the BRI and initiating BRI projects. Differing forms of primary agreements are adopted to meet various needs, including different governments and international organizations (e.g., the China–New Zealand MOA, and UNECE–NDRC MOU), areas and sectors (e.g., the MOU in the Field of Water Resources with the Government of Malaysia), and projects (e.g., the Protocol on Establishment of Joint Ocean Observation Station with the Ministry of Environment of Cambodia).Footnote 149 Applying the discussion of soft law by Shaffer and Pollack, China selects regimes (primary instruments) based on characteristics including their membership (e.g., bilateral and plurilateral), parties involved (national and sub-national governments, international organizations such as the UN), institutional characteristics (e.g., the absence of strict dispute settlement procedures), substantive focus (e.g., dispute settlement, trade facilitation, infrastructure finance, digital economy, and infrastructure standards), and predominant functional representation (e.g., by trade or finance ministries).Footnote 150 Relatedly, the network of primary agreements could enjoy the benefit of a network in terms of the ‘ability to add new members quickly and at low cost’.Footnote 151

4.3 Legitimacy

Primary agreements may increase the domestic and international legitimacy of the BRI, thereby helping to promote BRI projects. For domestic legitimacy in China, primary agreements help to show international support for the BRI,Footnote 152 including the third-party market cooperation agreements with advanced economies. As another example, the BRF Joint Communiques indicate the support of the BRI by the participants.

In respect of international legitimacy, primary agreements may be similar to soft law in that they may be used in justifying a state's actions.Footnote 153 Many of China's primary agreements link to existing international institutions and refer to international standards or rules (e.g., the adherence to ‘international good practice’,Footnote 154 and the compliance with ‘the purposes and principles of the UN Charter’, and the 2030 Agenda for sustainable development and the Paris Accord on climate changeFootnote 155). This may help to show the consistency of primary agreements with the normative status quo, and lend MOUs ‘more ability to claim legitimacy’.Footnote 156 That said, the effects of BRI primary agreements remain to be seen as the reshaping of the existing international order require wide support from the world community.

4.4 Summary

Crucially, BRI primary agreements help to promote BRI projects with reduced contracting costs and flexibility. From China's perspective, they may help establish the legitimacy of the BRI (e.g., by demonstrating the support of other parties to primary agreements). There is also likely to be a range of additional reasons behind the use of primary agreements. For instance, China appears to adopt a constructivist approach by taking advantage of ‘the communicative and constitutive impact’ of soft law.Footnote 157 Other reasons may include the various advantages of soft law, such as incrementalism,Footnote 158 and the response to ‘uncertainty by designing arrangements that are less formalized than full legalization’.Footnote 159 All these considerations behind primary instruments appear to be closely related to China's efforts to promote the BRI projects.

5. What Are the Challenges Faced by BRI Primary Agreements?

There are usually two major problems of international cooperation regardless of the substantive domain: bargaining problems and enforcement problems.Footnote 160 In the same vein, BRI primary agreements face at least two major challenges in terms of substantive rules and enforcement. The handling of these challenges will in turn affect the legitimacy of the BRI. Based on the analysis of these challenges, broader challenges for the parties to primary agreements will be explored.

5.1 Substantive Rules

Major challenges in substantive rules include rule inconsistency, ambiguity and vacuum, the balance between different considerations, a possible gap between the law-in-the-books and the law-in-action, and the relationship between primary agreements and other rules. These factors may lead to considerable issues in respect of the certainty and credibility of commitments.

First, primary agreements may face rule inconsistency, ambiguity, and vacuum. It is observed that ‘Western trade and investment projects would require the application of a uniform set of rules at the three levels of international/bilateral cooperation, domestic regulation, and private transactions.’Footnote 161 China appears to adopt a ‘One Country, One Approach’ to the BRI.Footnote 162 It is challenging in developing ‘“one legal framework” to find a single, common ground.’Footnote 163 Given the tremendous variation between the parties involved, primary agreements differ substantially, although they often share a similar basic structure. Additionally, the low level of precision results in a lack of elaborate rules (e.g., concrete required or disfavored behavior) and makes it more difficult to ensure the provisions are related to each other in a consistent manner.Footnote 164 The relationship among myriad forms of primary agreements is unclear and there is no central repository for BRI agreements. Even for BRI agreements concluded with one state, it is not easy to ensure their consistency (e.g., 51 MOUs concluded between China and Pakistan).Footnote 165

Rule ambiguity or vacuum could exist regarding various issues. The BRI projects invest largely in jurisdictions where other states and international financial institutions have been reluctant to invest,Footnote 166 and few of these countries are ‘noted for the rule of law’.Footnote 167 The BRI also expands to infrastructure and other new areas (e.g., data flow in Digital Silk Road). Many BRI legal issues fall outside the scope of WTO rules, FTAs, and BITs. All of these factors call for rules under the BRI and particularly international rules. However, primary agreements seldom address many of these issues. For instance, they rarely address wider social issues (e.g., labor issues and environment) and the robust monitoring of these issues, which affect the BRI's relationships with civil society and local communities.Footnote 168 Labor issues are generally untouched by primary agreements. The China–New Zealand MOA incorporates one ‘short and relatively weak’Footnote 169 clause that mentions environmental matters, calling for ‘push[ing] forward coordinated economic, social, environmental and cultural development and common progress’.Footnote 170 The Italy–China MOU provides a more detailed, although still general, provision on environment, including the participation in the International Coalition for Green Development on the Belt and Road.Footnote 171 This is partially explained by China's pragmatic project-based approach and social issues not being the major focus of China (e.g., China's FTAs and BITs lacking systematic rules on social issues). It is yet to be seen whether and how a regulatory system and governance standards in various BRI states would be put in place to properly address BRI related legal issues (e.g., long-term due diligence and financing, and social issues).Footnote 172

Second, it remains an open question as to how the balance is to be struck between different roles and considerations, and a gap could exist between the law-in-the-books and the law-in-action. A government may be an economic actor and a regulator, and there is tension behind these roles (e.g., economic and social considerations).Footnote 173 It is unclear how to best balance economic security (the right to regulate) with the constraints of economic sovereignty, which is a particular issue given the majority of BRI states are developing countries.Footnote 174

Free market principles are recognized in various primary agreements.Footnote 175 Due to the minimal legalization of primary agreements, time will tell whether and how these principles will apply in the practice. For instance, it is yet to be seen how the possible preferential treatment of Chinese products and services (given the source of the investment) will be balanced with market principles based on competition (like non-discrimination treatment provided in treaties).Footnote 176

Third, the relationship between primary agreements and other rules is not always clear. The obligations in primary agreements have legal implications for the signatories and even non-parties. To illustrate, the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor Memoranda may have multilateral effects on relationships other than between China and Pakistan (e.g. China–Russia, China–India and Pakistan–India relationships), and both states’ rights and obligations under international organizations to which they are members (like the WTO, World Customs Organization, the IMF, the World Bank, and the Asian Development Bank).Footnote 177

5.2 Enforcement

Challenges in enforcement may arise due to various factors, ranging from the minimal legalization of primary agreements to the actors’ negotiation positions. Primary agreements encounter enforcement issues as with existing soft law that ‘avoids judicialization’.Footnote 178 Minimal legalization of primary agreements (weak obligations, rule imprecision, and low delegation) makes enforcement more difficult. Flexibility could give rise to opportunistic behavior whenever ‘economic, political, or other pressures make compliance inconvenient’.Footnote 179 With weak legalization, ‘imprecise norms are, in practice, most often interpreted and applied by the very actors whose conduct they are intended to govern’.Footnote 180

For obligations and precision, the efficient operation of the BRI will probably require a certain level of legal harmonizationFootnote 181 that could bring reduced regulatory differences. However, primary agreements have a low level of obligation and precision. As observed by Kenneth W. Abbott and Duncan Snidal, ‘compliance issues are largely moot’ if soft law instruments have ‘little content.’Footnote 182 Primary agreements are insufficient to address possible problems like local protectionism or judicial corruption in the BRI practice.Footnote 183 Ambiguity would also ‘deflect …accountability’.Footnote 184 A low level of precision allows for wide discretion, in turn making it difficult to assess compliance.Footnote 185

For delegation, primary agreements are usually subject to consultation rather than a panel process.Footnote 186 In some exceptional circumstances, primary agreements provide for conciliation under UNCITRAL Conciliation Rules,Footnote 187 arbitration,Footnote 188 or lack a dispute settlement provision entirely.Footnote 189 Disputes over the interpretation of BRI agreements may arise, especially due to their general language, which cannot be fully addressed within the existing dispute settlement system.Footnote 190 Primary agreements do not bring a BRI-wide dispute settlement and monitory arrangement that will help enforcement, and it is unlikely that such an arrangement will be created anytime soon.

Consultations can hardly provide sufficient predictability for public and private actors, and may struggle to search for ad hoc solutions. Such difficulties may arise in practice including the calls for debt relief on BRI projects after the COVID-19 outbreak.Footnote 191 If consultations fail, the parties may only be able to rely on direct sanctions or on reputational sanctions which do not compensate the breached-against actors.Footnote 192 Soft law ‘often garners widespread participation, but it creates few concrete incentives for states to improve behavior’.Footnote 193 The lack of compliance review mechanism like third party enforcement may eventually lead to high transaction costs of interstate interaction to address disputes.

Many issues remain open. Soft law could be under-enforced if it turns out to be economically or politically more costly than the parties originally expected, and a party cherry picks certain aspects of soft law instruments.Footnote 194 For instance, it may be questioned whether enforcement is even a goal of primary agreements, when considered against the need for flexibility and preference for avoiding the tough decisions required for enforceable agreements. Will current primary agreements provide an efficient level of compliance? If a party to a primary agreement violates any obligation therein, will the other party halt its own compliance in retaliation? Is the ending of compliance by other parties a credible way to deter violations? All these are case-specific and depend on many aspects, including the issues and focuses of primary agreements, and actors involved. Factors beyond the agreements themselves, like domestic interest, will play a role. Essentially, there is a complex trade-off between compliance benefits and violation costs.

5.3 Broader Challenges

There are broader issues faced by the parties to primary agreements, which exist in both substantive rules and enforcement. An exhaustive list of all challenges cannot be developed here. However, several major areas deserve attention as they may make parties re-evaluate their expectations and also affect the views of outsiders towards the initiative.

Foremost, primary agreements impose challenges for BRI states regarding their negotiation capacity. This is particularly the case for small developing economies. BRI states may need to negotiate various issues as there is a lack of BRI-wide rules. Neither is there a central institution (e.g., an international organization) for formal rule-making under the BRI. Many BRI issues (e.g., infrastructure finance, technical standards, and e-commerce) are new or more complex than traditional issues (e.g., tariff reduction). The negotiations require the understanding of distributive consequences arising from rules (such as on trade, finance and investment) for different actors.Footnote 195 It is not easy to foresee the future ramifications of measures in fast changing circumstances.Footnote 196 Essentially, the negotiations involve the underlying issue of equity.

Second, there are challenges regarding various interests behind primary agreements. Primary agreements face the fact that actors have different interests, values, and degrees of power.Footnote 197 There are legal, political, economic, and social differences among a large number of BRI states. The BRI involves complicated issues areas, ranging from infrastructure to internet governance. For instance, infrastructure may ‘severely affect national interests’.Footnote 198 There could be gaps in a number of aspects: ‘(a) divergence in interests (who gains, who losses, who gains more); (b) conflicting ideational stakes (conflicting positions in preserving sovereignty, autonomy and identity); and (c) conflicting positions over alignment preferences (a big power wanting smaller states to side with or align more closely with it, while smaller states insist on retaining their external space for manoeuvre)’.Footnote 199 It is observed that ‘[t]he absence of common cultures, legal systems, and geopolitical interests among the BRI participants also forms significant political obstacles to the emergence of common legal practices or institutions across the BRI's extraordinary geographic scope’.Footnote 200 There is not always congruity between China and other parties in these aspects.

Third, uncertainties exist regarding the effects of primary agreements. There could be concerns that soft law may bring distorting effects on competition, which are linked with distributive imbalances and power asymmetries.Footnote 201 Soft law is often viewed as ‘a power or a persuasive force in its own right’.Footnote 202 To illustrate, Hanim Hamzah posits that ‘it is common for sponsors to provide legal terms in their favour’, which may affect the competitiveness of domestic industries of BRI states, and that an across-the-board ‘centrally coordinated’ approach could be problematic.Footnote 203 The BRI practice also faces concerns like transparency,Footnote 204 environment, labor, and debt sustainability.Footnote 205 In a broader sense, there could be challenges regarding legitimacy. Precision enhances the legitimacy of rules and their normative ‘compliance pull’,Footnote 206 while primary agreements have low level of precision. Soft law (e.g., international financial law) may be deemed to protect the interests of ‘key players’ and be vulnerable to power relations, and cause concerns over representativeness (e.g., more finite universe of interests), transparency, and accountability.Footnote 207 It is observed that standard-setting on a bilateral or regional basis ‘allow[s] for stronger influence by important actors’.Footnote 208 The challenges include how to address possible distributive implications of primary agreements as they often involve long-term projects (e.g. infrastructure), how to understand and address national interests in various states (e.g. Malaysia's East-Coast Rail Link project that was suspended on national interests and then restarted),Footnote 209 and how to address possible power asymmetries (e.g. reciprocal market access rights).Footnote 210

Finally, other challenges include that the perception of BRI agreements may differ between China and other parties. It is observed that ‘[w]hat one state believes it is signalling is not necessarily what another states[sic] hears’.Footnote 211 This issue may arise due to the sensitivity of many issues involved (e.g. infrastructure) and the minimal legalization of primary agreements, which often leave terms open to multiple interpretations.

6. Conclusion

BRI primary agreements can be regarded as soft law developing quasi-legal obligations across the BRI network. However, these agreements are also seen to repurpose the characteristics of soft law to support project development, distinct from the rule development pursued through many existing soft law instruments. Primary agreements have three major characteristics that differ from existing soft law: minimal legalization, a coordinated and project-based nature, and a hub-and-spoke network structure. In addition, primary agreements should be understood holistically with secondary agreements that often contain binding obligations to implement BRI projects. Primary agreements serve to promote projects directly (through project-linked agreements), and indirectly (through mechanism-creating agreements). It is not, however, simply the project nature of the primary agreements, but rather their scale and the extent of coordination involved that makes primary agreements unique. Minimal legalization is the pathway that China appears to have chosen to develop the BRI framework, with a hub-and-spoke network with China at the center as the structure built by primary agreements.

BRI primary agreements draw substantially on the advantages of soft law, and these advantages may largely explain the rationale behind China's adoption of primary agreements. Reduced contracting costs and flexibility help China to build wide participation and develop the BRI framework. From China's perspective, primary agreements may help its efforts to seek legitimacy (e.g. via a large number of parties signing primary agreements). In addition, the repurposing of soft law characteristics to drive project development can also be seen to align with China's current apparent prioritization of such project-based efforts over rule development more generally.

Given the focus on project development rather than on rule development, primary agreements may face various challenges. To illustrate, minimal legalization makes it difficult to regulate behavior and may create more uncertainties if interests or circumstances change. There is a long way for primary agreements to go in terms of the predictability, consistency, and stability of extra-regional economic order.

That said, the differences between project development and rule development are not absolute. BRI primary agreements currently appear to prioritize promoting project development over rule development, but it remains to be seen whether this will change in the future. There is a possibility that China may alter its priorities over time. In the long term and if everything goes smoothly, BRI primary agreements may also help China incrementally promote its role in international rule-makingFootnote 212 and selectively reshape rules.Footnote 213 For instance, the effects on rules may include the promotion of Chinese standards,Footnote 214 and agenda setting and possible rule development under China-led mechanisms. A number of issues deserve further study: Are primary agreements sustainable? Will primary agreements shift towards a greater focus on rule development? Will projects become the major way to reshape international rules in the future? Will primary agreements per se develop towards harder rules? Will other states follow the path of such primary agreements? What is the impact of COVID-19 outbreak on primary agreements, and how will primary agreements interact with secondary agreements (e.g., the extent of the former's effects on the latter)? Primary agreements and their implications deserve close attention. It remains to be seen whether they will allow for rapid responses to the fast-changing world in the post-COVID-19 era.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474745620000452.

Acknowledgement

A sincere thanks to an anonymous reviewer for the valuable suggestions. Part of the paper has been presented at the University of Edinburgh, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, and the author thanks Andrew Lang, Wei Shen, Markus Wagner, Giuseppe Martinico, and the participants of the talks for the insightful comments. The author is grateful to UNSW Law's Herbert Smith Freehills China International Business and Economic Law (CIBEL) Centre for the support, and to the European University Institute for hosting him as a Fernand Braudel Senior Fellow during which he worked on this paper. Special thanks also go to Jürgen Kurtz as the host and to Melissa Vogt for her excellent research assistance and comments.