Introduction

Previous work suggests that aesthetic judgments (e.g., “This sculpture is beautiful”) are self-referential. For example, neuroimaging work has shown that aesthetic enjoyment is associated with activity in the default mode network (Belfi et al., Reference Belfi, Vessel, Brielmann, Isik, Chatterjee, Leder, Pelli and Starr2019; Vessel, Starr, & Rubin, Reference Vessel, Starr and Rubin2012), a system of brain regions implicated in self-referential processes, including autobiographical memory (Buckner, Andrews-Hanna, & Schacter, Reference Buckner, Andrews-Hanna and Schacter2008). This finding has been interpreted as evidence that individuals engage in self-reference when evaluating works of art – that is, if evaluating art activates brain regions involved in self reference, the assumption is that aesthetic judgments are self-referential. While these neuroimaging results are interpreted as evidence for the self-referential nature of aesthetic judgments, there is no prior behavioral work to this end. Here, we sought to behaviorally test whether aesthetic evaluations are similar to other self-referential processes. The self-reference effect (SRE) is a memory-based phenomenon where individuals show improved memory for items that are judged in relation to themselves (Philippi, Duff, Denburg, Tranel, & Rudrauf, Reference Philippi, Duff, Denburg, Tranel and Rudrauf2012). The SRE has been observed for trait adjectives: For example, an individual is more likely to remember an adjective such as “kind” if they attribute that trait to themselves rather than a family member. The aim of the current study was to understand if the SRE exists when making aesthetic judgments of music. We predicted that music judged in an aesthetic manner (i.e., “I like that song”) would be remembered better than music judged in a non-aesthetic manner (i.e., “That is a classical piece of music”).

Objective

The goal of the present study was to investigate whether making aesthetic judgments of music in relation to the self (i.e., “How much do you like this music?” vs. “How much would someone else like this music?” vs. “What is the genre of this music?”) confers a memory advantage for the music. While there are many types of judgments that could be considered ‘aesthetic,’ here we looked at judgments of liking. We hypothesized that musical excerpts judged in relation to the self would be remembered better than excerpts judged in relation to another person and excerpts identified by their genre.

Methods

Participants

Thirty students (21 Female, Age: M = 19.21, SD = 1.07) participated in Experiment 1 and twenty different students (17 Female, Age: M = 18.52, SD = 0.70) participated in Experiment 2. Fifteen individuals in Experiment 1 and 15 individuals in Experiment 2 reported having formal musical experience (self report of one or more years).

Stimuli

Stimuli were 60 unfamiliar, instrumental musical excerpts from three genres: classical (n = 20), jazz (n = 20), and electronic (n = 20). Each excerpt was 5 seconds long.

Procedure

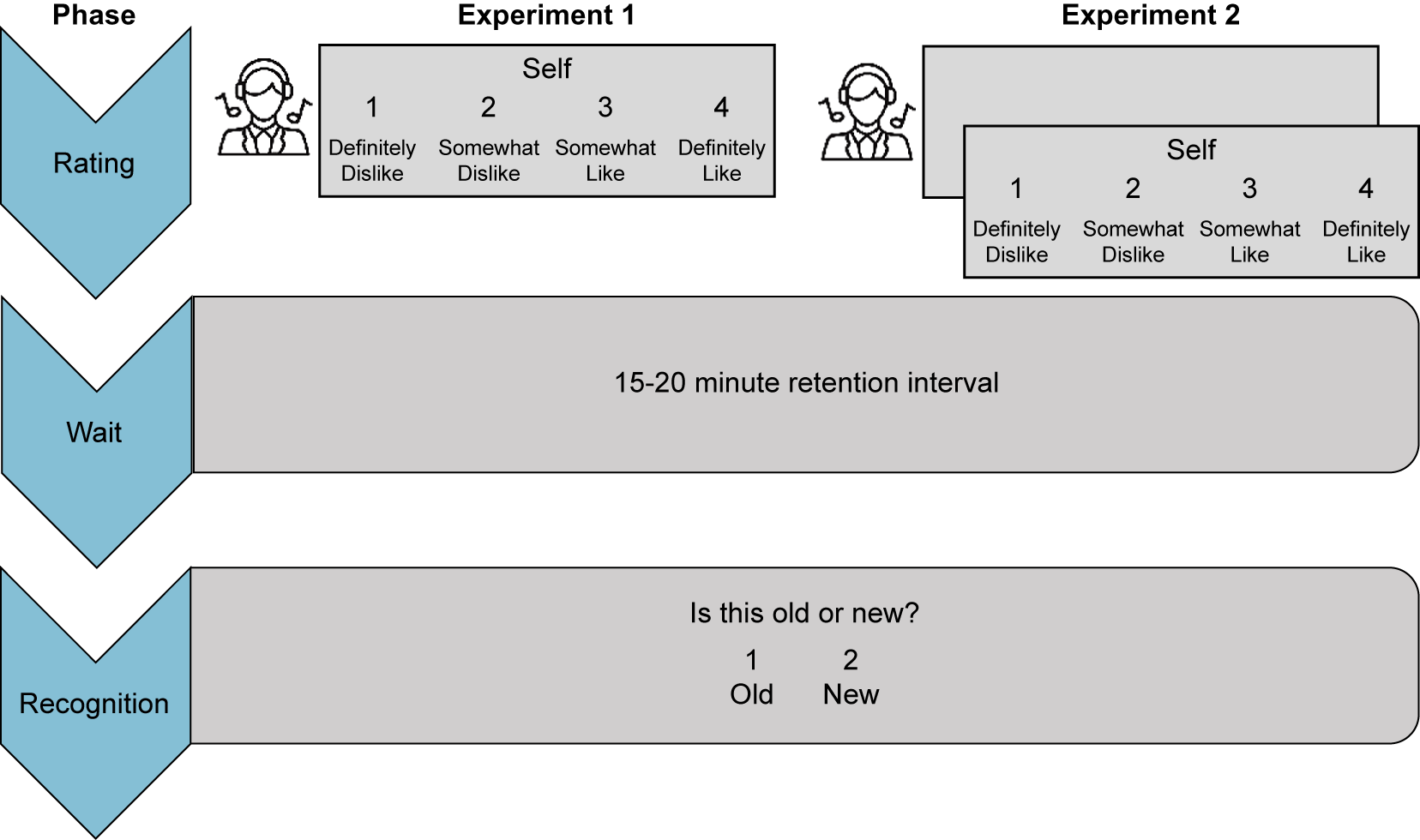

Participants completed a rating task and a recognition memory task. During the rating task, participants heard a musical excerpt and rated on a 4-point scale how much either they liked it (Self condition), how much a close relative/friend would like it (Other condition), or the genre of the piece (Genre condition). Participants rated 10 musical pieces in each condition. In Experiment 1, the rating scale was displayed on screen while the music was playing. In Experiment 2, the rating scale was displayed after the music finished. After a retention interval of 15–20 minutes, participants completed the recognition memory task (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic of the experimental task. In Experiment 1, the rating question was displayed on screen simultaneously with musical excerpt presentation. In Experiment 2, the rating question was displayed after listening to the excerpt. For the recognition memory task, participants heard the 30 excerpts previously played, as well as 30 novel excerpts. After each excerpt, participants judged whether the excerpt was old or new.

Results

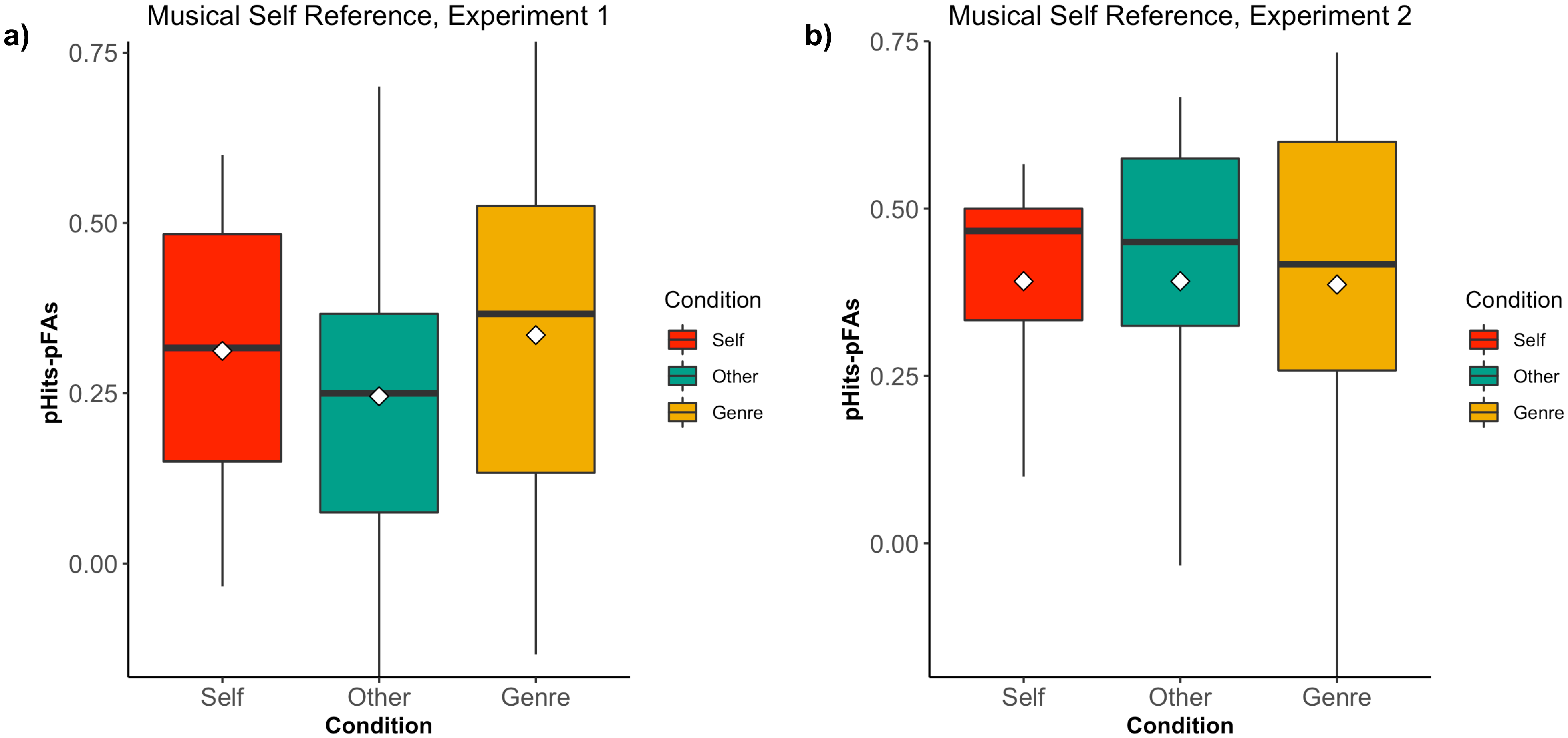

Recognition memory scores were computed for each participant as the proportion of hits minus the proportion of false alarms (pHits-pFAs) for each condition. Hits were “old” excerpts correctly identified as old and false alarms were “new” excerpts incorrectly identified as old. A one-way repeated measures ANOVA was conducted separately for each version of the experiment. There was no significant difference in recognition scores between the three conditions in either Experiment 1 (F(2, 58) = 2.76, p = 0.072) or Experiment 2 (F(2, 38) = 0.0077, p = 0.99). Thus, memory for “old” clips was not better in the Self condition than in the Other or Genre conditions (i.e. no SRE, see Figure 2). Additionally, we repeated this analysis within each genre and found no SRE for any of the three genres in Experiment 1 (see Figure 3) nor Experiment 2. The data are available at https://osf.io/t3abh/.

Figure 2. Recognition memory scores (proportion of hits – proportion of false alarms) in the Self, Other, and Genre conditions for a) Experiment 1 and b) Experiment 2. In both cases, there was no self-reference effect for musical liking. Boxplots depict the median (solid black line) and the first and third quartiles (25th and 75th percentiles). Whiskers extend up to 1.5x the interquartile range and white diamonds depict the mean for each condition.

Figure 3. Recognition memory scores categorized by genre in Experiment 1. A two-way repeated measures ANOVA (genre, condition) revealed a significant effect of musical genre (F(2, 52) = 9.77, p = 0.00025) but neither an effect of condition (F(2, 52) = 2.88, p = 0.065) nor a genre by condition interaction (F(4, 104) = 1.89, p = 0.12). Boxplots depict the median (solid black line) and the first and third quartiles (25th and 75th percentiles). Whiskers extend up to 1.5x the interquartile range and white diamonds depict the mean for each condition.

Discussion

In Experiment 1, participants knew the judgment they would be making while listening to the music. Knowing what they were judging (self, other, or genre) could have influenced their attentiveness to the music. For example, judgments of genre may require attention to specific musical features, while aesthetic judgments may point the listener towards memories or feelings associated with the music (Kubit & Janata, Reference Kubit and Janata2018). Therefore, in Experiment 2, listeners were not aware of the judgment to be made until after listening to the excerpt. In either case, there was no memory benefit for self-encoded music. One limitation to this work is the inclusion of musicians in the sample, as musicians have been shown to perform better than non-musicians in short-term and working memory tasks (Talamini, Altoè, Carretti, & Grassi, Reference Talamini, Altoè, Carretti and Grassi2017).

Overall, these results indicate that there is no memory benefit for musical excerpts judged in an aesthetic manner. This suggests aesthetic judgments may differ from other types of self-referential judgments. Though prior neuroimaging work indicates the involvement of brain regions important in self-referential processes, aesthetic judgments may not be directly self-referential.

Conclusion

While previous work suggests that making aesthetic judgments activates neural structures underlying self-reference, the current data do not suggest any memory benefit for items judged aesthetically in relation to the self. There are many factors that could influence this effect – length of retention interval, musical genre, or musical experience of the participants. Therefore, while the current data cannot definitively rule out the presence of an aesthetic SRE, the present work does not support the existence of this effect.

Author Contributions

AB designed the study, AK collected data, and AB and AK analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Funding Information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

Conflicts of interest: AK and AB declare none.

Acknowledgments.

We thank Andrea Halpern, Danielle Retcho, Ed Vessel, and Jess Rowland for stimulus development and Petr Janata for insightful comments.

Comments

Comments to the Author: I think that the experiment was well designed and there are no major observations that I would like to make. I would recommend accepting the study only after having changed a few minor things: I think that the introduction does not really give the idea of the topic, and the reader cannot understand what the “default mode network” is. I would spend a few words more on that if possible. Moreover, I think that it would be more interesting to have other behavioral studies in the introduction (1 or 2), which can give an idea of what was done in the past. This would also help to strengthen the objective: in fact, to me is not really clear why the SRE for traits adjectives could be related to the evaluation of a piece of music. Concerning the method, the authors should mention whether there were musician participants or not. Musicians are known to perform better in the recognition of musical excerpts. If there were musicians, this should be acknowledged as a limitation.