1. Introduction

Mild and mild-moderate major depressive disorder (MDD) is one of the most important reasons for consulting a general practitioner (GP) and it will be among the three leading causes of disease burden by the year 2030 [Reference Paykel, Brugha and Fryers1]. There is a lack of international consensus on the most appropriate therapeutic approach and the best strategy for implementation in Primary Care (PC). While, in some countries, pharmacological treatment with antidepressants (ADs) is recommended as an acute-phase treatment for patients with mild to moderate symptoms [2]; in most European countries a watchful waiting (WW) approach seems to be the first treatment step [3–Reference van Avendonk, van Weel-Baumgarten, van der Weele, Wiersma and Burgers5].

WW, also known as active monitoring or supportive care, has been described as an agreement between the clinician and the patient not to immediately treat the condition with ADs but to intermittently reassess its status during a specific follow-up period [Reference Hegel, Oxman, Hull, Swain and Swick6]. In common with most European guidelines for the treatment of depression, the Catalan Clinical Guideline [4] recommends that patients treated in PC should be regularly visited by GPs and offered a variety of non-pharmacological interventions (low-intensity psychosocial and psychological interventions such as problem-solving techniques, active listening, counselling, brief or computerised cognitive behavioural therapy, or medical education) while closely monitoring clinical progress. Studies show that this treatment approach is limited due to barriers including the clinician’s high care burden and lack of time, knowledge of psychotherapy and availability of mental health professionals for referral [Reference Meredith, Cheng, Hickey and Dwight-Johnson7].

Our recent systematic review found only three studies properly assessing the clinical effectiveness of WW compared with ADs when mild and mild-moderate MDD was treated in PC. No statistically significant differences in effectiveness between the two treatment arms were found in any of the articles when the main analysis was conducted (longitudinal analysis) [Reference Iglesias-González, Aznar-Lou, Gil-Girbau, Moreno-Peral, Peñarrubia-María and Rubio-Valera8]. The small sample sizes may have limited the capacity of these studies to detect statistically significant differences between groups.

The aim of this study is to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of WW compared with the use of ADs for the treatment of mild-moderate depressive symptoms in real PC practice.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This was a 12-month follow-up naturalistic prospective controlled trial comparing patients that received AD drugs with those who received WW. The study was approved by our institution (PSSJD: EPA-24-12; IDIAP: 5013-002). The detailed study protocol has been published elsewhere [Reference Rubio-Valera, Beneitez, Peñarrubia-María, Luciano, Mendive and McCrone9].

2.2. Setting and participants

The study was conducted in 12 PC centres in the province of Barcelona (Catalonia, Spain) and 68 GPs participated in the recruitment of patients.

Prior to the study, GPs received a three hour-training session on the study protocol, diagnostic criteria for depression, and national guidelines for the treatment of MDD in PC.

GPs recruited patients for the study from their daily list of patients attending the practice. Eligible patients were adults (≥18 years-old) diagnosed with a first or recurrent new episode (new diagnosis or relapse) of mild to moderate MDD according to the GP’s clinical judgement (due to the study design, there was no need for structured clinical diagnosis through standardised assessment scales). Patients were excluded if they had taken AD medication in the previous 60 days, had taken antipsychotics, lithium or antiepileptics in the previous six months, presented psychotic or bipolar disorder, had a history of drug abuse or dependency, had cognitive impairment that prevented an assessment interview, or refused to provide signed informed consent.

2.3. Interventions

In accordance with the study’s naturalistic design, GPs used their professional clinical judgment to recommend a treatment option to the patient. Patients were recommended a WW approach or pharmacological treatment with ADs.

Patients in the WW group agreed with the GP not to immediately treat the condition with ADs but to closely monitor the symptoms through a series of follow-up visits. In line with the Catalan Guideline [4], a first follow-up visit was scheduled to take place within the following 2 weeks. The guideline recommends from six to eight follow-up visits over 10–12 weeks, where GPs can consider non-pharmacological interventions. It also recommends structured, supervised exercise programmes of moderate intensity. As part of the stepped care model, in the case that the patient’s condition does not improve, the GP can intensify the treatment and initiate ADs. The number of visits following recruitment by the GP was used to monitor adherence to WW.

Patients in the AD group received pharmacological treatment with SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), particularly with citalopram, sertraline, paroxetine or fluoxetine. Adherence to ADs was monitored through pharmacy records and patients’ self-reported adherence (using the 4-item scale developed by Morisky et al. [Reference Morisky, Green and Levine10].

2.4. Outcomes

Sociodemographic data were collected on study commencement: age, gender, marital status, education and employment status.

The following outcomes were assessed at baseline, six and twelve months by an external researcher. The primary study outcome was the effectiveness of each treatment, WW or ADs, measured in terms of depression severity. This was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item depression module (PHQ-9) [Reference Diez-Quevedo, Rangil, Sanchez-Planell, Kroenke and Spitzer11, Reference Spitzer, Kroenke and Williams12]. The scale consists of nine items scored from 0 to 3, with a summed score that ranges between 0 (no symptoms of depression) and 27 (all symptoms of depression every day): 0–4 indicates minimal symptoms; 5–9 mild depression symptoms; 10–14 moderate symptoms; 15–19 moderate-severe symptoms; and 20–24 severe symptoms.

Diagnosis according to DSM-IV criteria was not used as an inclusion criterion. However, clinical diagnosis according to DSM-IV criteria was assessed using the research version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) [Reference First, Spitzer, Miriam and Williams13]. The mood and anxiety disorder modules were used.

Severity of anxiety was evaluated through the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), which is a twenty-one item self-report inventory ranging from 0 (minimal level of anxiety) to 63 (severe anxiety) [Reference Beck, Epstein, Brown and Steer14, Reference Sanz, García-Vera, Espinosa, Fortún and Vázquez15].

The Spanish version of the EuroQol-5D-3 L (EQ-5D) was used to measure health-related quality of life [Reference EuroQol Group16, Reference Badia, Schiaffino, Alonso and Herdman17]. The EQ-5D generates a health tariff that is anchored in 1.000 (best health state) and 0.000 (being dead).

The 12-item interviewer-administered version of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (12-item WHO-DAS 2.0) was used to assess disability [Reference Luciano, Ayuso-Mateos, Fernandez, Aguado, Serrano-Blanco and Roca18]. Total scores range between 0 and 100, with higher scores indicating a greater degree of disability.

Cognitive representation of medication was assessed using the Beliefs about Medicine Questionnaire (BMQ) [Reference Beléndez-Vázquez and Horne19, Reference Horne, Weinman and Hankins20]. Total scores range between 8 and 40. Higher scores represent more negative beliefs about medicines.

Chronic physical conditions were assessed using a “yes” or “no” check-list.

See study protocol for more detailed information on the administered scales [Reference Rubio-Valera, Beneitez, Peñarrubia-María, Luciano, Mendive and McCrone9].

2.5. Analysis design/strategy

Both intention to treat (ITT) analysis (all patients were included in the analysis in the group to which they were allocated independently of the treatment they finally received) and per-protocol (PP) analysis (including only those patients who adhered to the treatment originally allocated) were performed. Adherence in the WW group was defined as receiving at least 3 follow-up visits and at least one of the recommended interventions (psychoeducation, problem-solving therapy and/or physical exercise). Adherence in the ADs group was defined as having a mean medication possession ratio (number of pills filled/number of days of treatment) higher than 0.8. Sample size calculation was based on the primary study outcome: cost-effectiveness. See the study protocol [Reference Rubio-Valera, Beneitez, Peñarrubia-María, Luciano, Mendive and McCrone9] for detailed information.

Missing data patterns were evaluated to assess the plausibility of data missing at random [Reference Sterne, White, Carlin, Spratt, Royston and Kenward21]. To minimise bias resulting from the loss of information not following a completely random pattern, missing values were imputed using multiple imputation by chained equations. The imputation model included relevant socio-demographic and prognostic variables associated with drop-outs and outcome variables [Reference White, Royston and Wood22]. The number of imputations was calculated using a rule of thumb with respect to the fraction of missing information (M>100*FMI).

As this was a naturalistic study, GPs were allowed to recommend ADs or WW, based on their own clinical criteria, taking the patient’s symptoms and preferences into account. All GPs were asked to recommend both treatments although patients receiving ADs may differ from those receiving WW in ways that could predispose them to make greater or lesser use of services and/or experience different clinical progress, leading to unbalanced comparison groups. We assessed which variables were associated with a higher probability of receiving WW. After adjustment for significant variables, the only variable that predicted the use of WW was the beliefs about medication questionnaire. Therefore, all analyses were adjusted for BMQ results.

Effect size was determined by calculating the mean difference between the two groups and then dividing the result by the pooled standard deviation.

2.6. Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics of the groups were compared using the t-test for continuous variables and logistic regression for categorical variables.

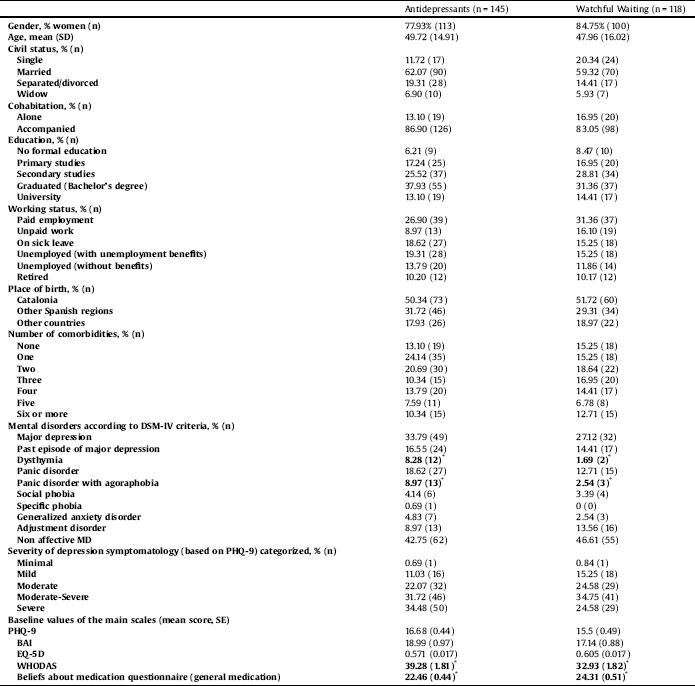

Statistically significant differences between groups existed in the proportion of patients with a diagnosis of dysthymia and panic disorder with agoraphobia, as well as baseline values in the WHODAS scale and the BMQ for general medication. All analyses were adjusted for these variables, age and gender (Table 1). No other statistically significant differences existed between the two treatment arms at baseline.

Two analysis strategies were subsequently employed. Our main strategy was a multilevel longitudinal analysis with data from the same individuals grouped over three time periods (baseline, 6 months and 12 months, modelled simultaneously). To assess the effectiveness of WW, we used severity of depression, severity of anxiety, disability and quality of life as dependent variables. Time × treatment interactions were tested in all models. We considered the effect of the intervention to vary over the course of the study when the interaction was statistically significant. The model without interaction was used when the interaction term was not statistically significant. Clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of both patient and physician were tested in bivariate regression models for each of the dependent variables. In addition to the BMQ, those variables that were associated with the dependent variables in these models (p ≤ 0.05) were used to adjust longitudinal models. As pre-specified, all the analyses were adjusted for age and gender.

As in previous papers, we used a sensitivity analysis as a secondary analytical strategy [Reference Kendrick, Chatwin, Dowrick, Tylee, Morriss and Peveler23]. We used linear regression models to assess differences between groups at 6 and 12 months. These models included severity of depression and anxiety, disability and quality of life as dependent variables and treatment as the independent variable. The adjustment strategy was similar to the main analysis as described above.

Stata MP13.1 for Windows was employed to conduct all analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Participants and drop outs

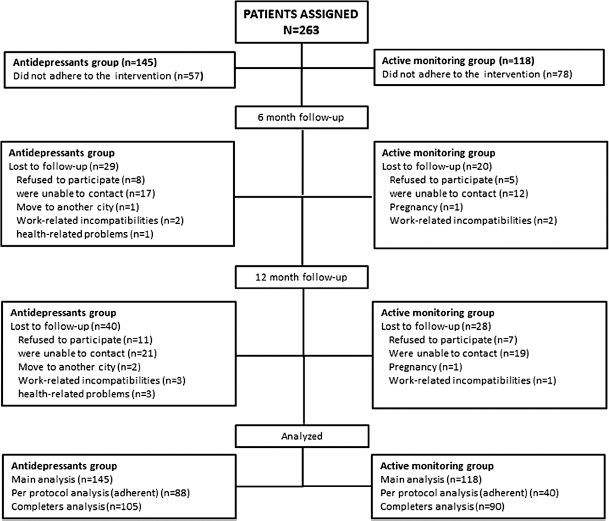

A total of 263 patients were assigned to AD (n = 145) and WW (n = 118) groups, evaluated at baseline and included in the ITT analysis. Fig. 1 shows the flowchart. Fifty-seven patients in the AD group (39%) and seventy-eight patients in the WW group (66%) did not adhere to the intervention. The rationales for non-adherence are also shown in Fig. 1. Only 88 and 40 patients in the control and intervention group, respectively, were included in the PP analysis.

3.2. Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. Most participants were women (AD: 85%; WW: 78%), with mean ages of 50 and 48 years old in the AD and WW groups, respectively; and the majority of patients in both groups were married. Approximately one third of the sample had secondary education and was actively working. Thirty-one percent of the participants met DSM-IV criteria for MDD and the mean baseline severity of depression according to the PHQ-9 was 16.15 (corresponding to moderately severe symptoms). Adherence rates were 61% in the control group (AD) and 34% in the intervention group (WW). Among patients who did not receive WW as intended, 54% did not receive at least one of the recommended non-pharmacological interventions and 84% did not receive at least 3 follow-up visits. Thirty-nine percent of the patients declared having none of these two requirements.

3.3. Main outcome measures

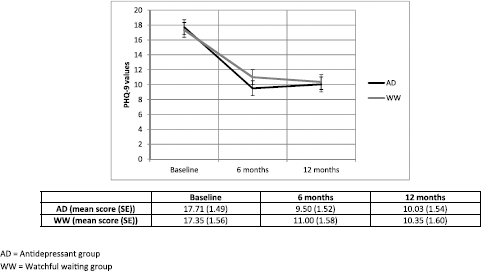

Table 2 shows the results from the ITT longitudinal analysis at 6 and 12 months for the different scales used: severity of depression (PHQ-9), severity of anxiety (BAI), disability (WHODAS) and quality of life (EQ-5D). Our main outcome measure regarding severity of depression demonstrated a statistically significant interaction in favour of the AD group at 6 months but significance was not maintained at 12 months (p = 0.487) after treatment initiation. Effect size was very small at both 6 and 12 months (<0.04). Fig. 2 shows the development of depression severity over time for both groups.

Concerning secondary outcomes (Table 2), only a statistically significant time x group interaction in favour of ADs at 6 months in the scales testing disability (WHODAS) (p = 0.019) was observed. As with depression severity measures, this difference was not seen at 12 months (p = 0.568). Effect size was also very small at 6 months and at 12 months (<0.04). Fig. 3 shows mean values for WHODAS scores by group over time. There were no statistically significant differences at any time point in the scale scores measuring severity of anxiety or quality of life at 6 or 12 months.

There were no differences in the sensitivity analysis or the PP analysis in any of the assessment scales administered (see supplementary files).

4. Discussion

Our results show that there are no clinically relevant differences between WW and ADs in the improvement of mild-moderate depressive symptoms when diagnosed and treated in PC. There is a tendency to improve more rapidly with the use of ADs but these subtle initial differences fade at 12 months. These results match those found in previous literature [Reference Kendrick, Chatwin, Dowrick, Tylee, Morriss and Peveler23, Reference Hermens, van Hout, Terluin, Adèr, Penninx and van Marwijk24], where no prominent differences in effectiveness are seen in any of the treatment arms in the management of mild to moderate depressive symptoms. In our recent systematic review [Reference Iglesias-González, Aznar-Lou, Gil-Girbau, Moreno-Peral, Peñarrubia-María and Rubio-Valera8], only one of the included studies reported statistically significant differences in clinical symptoms in favour of ADs in the PP analysis at 13 weeks. However, no between-group differences were observed in the same sample in the ITT analysis [Reference Hermens, van Hout, Terluin, Adèr, Penninx and van Marwijk24].

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics of both groups at baseline.

* Statistically significant differences at baseline between groups (p < 0.05).

Despite the unexpected nature of our results and those found in the literature, some factors should be considered when interpreting the results. Treatment non-adherence, diagnostic inadequacy, and difficulties in evaluating and typifying depressive symptoms in relation to their severity are common issues in daily clinical PC practice. These factors could limit treatment effectiveness of both WW and ADs.

Treatment non-adherence is one of the major challenges associated with the worsening of patients' clinical and economic outcomes [Reference López-Torres, Párraga, Del Campo, Villena and ADSCAMFYC Group25, Reference Ho, Chong, Chaiyakunapruk, Tangiisuran and Jacob26]. Both pharmacotherapy and non-pharmacological interventions are hindered by a lack of systematic follow-up and poor adherence, and associated factors appear to be multifactorial [Reference van Servellen, Heise and Ellis27]. In our study, adherence rates were low in both groups, especially in the WW group. Other pragmatic studies have also demonstrated poor adherence to treatment among outpatients with MDD, suggesting that early treatment optimisation and close follow-up are required to prevent long-term suffering and treatment discontinuation [Reference Sirey, Banerjee, Marino, Bruce, Halkett and Turnwald28]. The naturalistic scenario of this study has strong external validity reflecting daily clinical practice and highlighting patient and GP difficulties in following clinical guidelines for the treatment of depressive disorders. Treatment non-adherence is widely recognised as one of the reasons for treatment failure in MDD and this should lead to implementation of system-level interventions to improve treatment response and perceived health benefits [Reference Simon, Johnson, Stewart, Rossom, Beck and Coleman29].

Fig. 1. Study flow chart.

Table 2 Multilevel model based β-coefficients (SE) and p-values for severity of depression, quality of life, disability and severity of anxiety.

MDD: Major Depressive Disorder, SE: Standard Error, Ni: No interaction, WW: Watchful Waiting.

The bold values statistically significant differences between groups (p < 0.05).

A Adjusted for sex, age, civil status, educational qualifications, working status, number of comorbidities, baseline WHODAS mean value, dysthymia, adjustment disorder, panic disorder, panic disorder with agoraphobia, social phobia and beliefs about medication.

B Adjusted for sex, age, civil status, cohabitation, educational qualifications, working status, number of comorbidities, cardiovascular comorbidities, baseline WHODAS mean value, previous MDD, adjustment disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, dysthymia, panic disorder with agoraphobia and beliefs about medication.

C Adjusted for sex, age, educational qualifications, working status, number of comorbidities, respiratory comorbidities, digestive comorbidities, baseline WHODAS mean value, previous MDD, dysthymia, anxiety disorder with agoraphobia and beliefs about medication.

D Adjusted for time, sex, age, educational qualifications, working status, number of comorbidities, digestive comorbidities, baseline WHODAS mean value, dysthymia, anxiety disorder with agoraphobia and beliefs about medication.

Fig. 2. Development of severity of depressive symptoms (Mean PHQ9 score and SE) by group based on the regression model.

Fig. 3. Development of disability symptoms (Mean values for WHODAS score and SE) by group based on the regression model.

Qualitative research has explored the conversational influences on physician decision-making about treatment for depression. The results of the study point out that patients’ preferences and conceptual models of depression treatment play an important role in physician decision making. Though patient cues regarding their beliefs and preferences were presented in a subtle form, physicians appeared remarkably sensitive to these cues [Reference Karasz, Dowrick, Byng, Buszewicz, Ferri and Hartman30]. Recent literature [Reference Jaffray, Cardy, Reid and Cameron31] also suggests that exploring patient knowledge and views on depression and ADs seems to be vital when approaching MDD treatment. Development of patient-centred care systems, involving the patient more actively in treatment decision-making could improve adherence and, consequently, treatment efficacy [Reference van Schaik, van Marwijk, van der Windt, Beekman, de Haan and van Dyck32].

Other studies suggest implementing psychosocial and multidisciplinary interventions to improve early adherence to treatment [Reference Sirey, Banerjee, Marino, Bruce, Halkett and Turnwald28, Reference Rubio-Valera, Serrano-Blanco, Magdalena-Belío, Fernández, García-Campayo and March Pujol33]. This first step is part of the collaborative chronic care model which the literature consistently supports as a type of multi-component intervention to improve physical and mental outcomes for individuals with mental disorders. The collaborative care model includes a range of interventions of varying intensity, ranging from simple telephone interventions to more complex interventions involving structured psychosocial interventions. Collaborative care has proved to be more effective than standard care in improving depression outcomes in the short and longer terms [Reference Gilbody, Bower, Fletcher, Richards and Sutton34, Reference Woltmann, Grogan-Kaylor, Perron, Georges, Kilbourne and Bauer35], even by successfully treating depressive symptoms among older adults presenting with subthreshold depression who do not meet clinical criteria for MDD [Reference Gilbody, Lewis, Adamson, Atherton, Bailey and Birtwistle36]. These multifaceted interventions infer a greater role for nonmedical specialists such as nurse practitioners working in conjunction with PC physicians and mental health specialists. The figure of a care manager for maintaining continuous contact with patients with depression is part of this model and has positive effects on depression course, return to work, remission frequency, antidepressant frequency, and quality of life compared to usual care [Reference Björkelund, Svenningsson, Hange, Udo, Petersson and Ariai37]. In Spain, there have been few collaborative care programs which have also demonstrated better clinical outcomes in patients with MDD in PC settings [Reference Aragonès, Lluís Piñol, Caballero, López-Cortacans, Casaus and Maria Hernández38]. However, the lack of resources and training are still making it difficult to implement this complex model in real clinical PC practice.

MDD diagnostic adequacy should also be taken into consideration. In our sample, only 27.12% of patients in the WW group and 33.78% of the patients in the AD group met DSM-IV criteria for a major depressive episode. The remaining patients satisfied criteria for other affective disorders or did not meet criteria for any affective or anxiety disorder in the SCID-I. A large meta-analysis published in 2009 by Mitchell et al. [Reference Mitchell, Vaze and Rao39] with 50,371 patients diagnosed with depression by GPs revealed adequate diagnosis in 47.3% of cases, with more false positives than either missed or identified cases. Other studies performed in our country show even more negative results. In the DASMAP study, only a quarter of cases diagnosed as depressed by GPs were confirmed by a structured diagnosis [Reference Fernández, Pinto-Meza, Bellón, Roura-Poch, Haro and Autonell40]. Mitchell et al. highlighted the importance of re-assessment as a way to improve diagnostic accuracy. However, it is not clear that a correct MDD diagnosis would improve patient response to treatment. Previous research has found that patients suffering from other depressive disorders (minor depression, depressive disorder not otherwise specified) may not be qualitatively different as many subjects may later develop a MDD [Reference Cuijpers and Smit41–Reference Serrano-Blanco, Pinto-Meza, Suárez, Peñarrubia, Haro and ETAPS Group43]. Moreover, it seems that the degree of benefit of AD medication compared with placebo in patients diagnosed as depressed following diagnostic criteria increases with severity of depression symptoms and is minimal or non-existent in patients with mild or moderate symptoms [Reference Fournier, DeRubeis, Hollon, Dimidjian, Amsterdam and Shelton44]. In the subgroup of patients with mild-moderate depressive symptoms, diagnostic inadequacy might not underlie lack of response to treatment. However, it is still indicative of the lack of time and resources for diagnosing and reassessing depressed patients in a PC setting.

Depression severity has been directly associated with valid diagnosis of MDD in many studies [Reference Castro-Rodríguez, Olariu, Garnier-Lacueva, Martín-López, Pérez-Solà and Alonso45, Reference Nuyen, Volkers, Verhaak, Schellevis, Groenewegen and Van den Bos46]. A meta-analysis showed that only one in three people are correctly diagnosed when presenting with distress and mild depression in PC [Reference Mitchell, Rao and Vaze47]. Patients in our sample had a mean severity PHQ-9 score corresponding to moderately-severe symptom intensity. Patients with less severe depressive symptoms (and lower PHQ-9 scores) may not contact PC services and could remain undiagnosed as they did not consult a GP. Active efforts to identify these patients might be necessary to prevent future development of more severe forms of depression [Reference Cuijpers and Smit41].

Patients with somatic comorbidities may also need different strategies when diagnosed and treated for depression [Reference Nuyen, Volkers, Verhaak, Schellevis, Groenewegen and Van den Bos46]. Most patients in our sample had at least 2 somatic comorbidities (63% of patients in the control group and 69% of patients in the intervention group) that might have affected in GPs’ evaluation of depressive symptoms and the way they approach them in daily clinical practice.

In this context, we do understand the discrepancies among different clinical guidelines that adapt their recommendations in response to existing resources (Departament de Salut Generalitat de Catalunya, 2010; NICE, 2009; APA, 2010). In the UK, for instance, there is a growing number of experienced counsellors developing specific psychological and psychosocial interventions in PC practice [3]. Although clinical guidelines also recommend the same non-pharmacological approach in Spain, there is an acknowledged lack of resources and insufficient coordination between PC and Mental Health Services [Reference Calderón, Balagué, Iruin, Retolaza, Belaunzaran and Basterrechea48, Reference Latorre Postigo, López-Torres Hidalgo, Montañés Rodríguez and Parra Delgado49]. In this context, we contemplate the need to adjust clinical guidelines to real clinical practice and to devote more time and resources to improving health education, patient-centred care programmes, adherence to treatment and communication with mental health specialists. The effectiveness of each treatment strategy could be formally evaluated to provide more reliable information on the genuine, direct effectiveness of treatments.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

The naturalistic design of the study is considered a meaningful strength because it gives us a very clear view of how mild to moderate depression is approached in PC, detecting where weaknesses in the system are and allowing us to suggest where improvements could be made. However, it could also be considered as a limitation because a non-randomisation method was used that may have generated unbalanced groups. To minimise this, we adjusted our analysis with the variables that were associated with higher probability of receiving WW and the variables that differed between groups at baseline.

Another factor related to a naturalistic design concerns the low concordance rate between the clinical diagnosis made by the GP and the diagnosis according to SCID-I criteria, which may prevent us from evaluating the effectiveness of both treatments on pure MDD, but on mild to moderate depressive symptoms which do not meet MDD criteria. In our sample, the majority of patients present with subthreshold depressive symptoms or mild to moderate depression. Subsequently, generalization to MDD is not possible due to inadequate diagnosis.

Reasons for refusal or non-participation of the patients invited to take part of the trial were not recorded, not allowing us to determine how typical these participants are.

Adherence to protocol was low, which may have influenced the results obtained. To minimise this, we performed sensitivity and PP analyses.

GP participation was voluntary and therefore, GP participants may have been more motivated in mental health than their colleagues. As a consequence, their daily practice might be better adapted to the needs of these patients than standard PC practice overall.

5. Conclusion

Based on the results obtained in our study, which are in line with the existing literature, there is not enough evidence to support the superiority of WW or ADs in approaching mild to moderate depressive symptoms in PC. More research is still needed to inform GPs or policy-makers before either approach is strongly indicated. This research should also aim to determine which elements, such as an increase in GP resources (education, time, supporting counsellors and health advisors), diagnostic adequacy and/or treatment adherence, could improve the treatment of depression in PC. Practical implications would include patient decision-making strategies, GP training on how to explore the patients and other interview techniques, improve active detection of mild depression and the management of non-pharmacological treatment approaches.

Conflicts of interest

This research was funded by project "Coste-efectividad de una intervención no farmacológica en depresión mayor en Atención Primaria: Estudio INFAP" (PI11/013145) included in Spanish National Plan for R&D cofunded by Institute of Health Carlos III (ISCIII) and European Fund for Regional Development (FEDER).

Acknowlegedment

We are grateful to Stephen Kelly for his contribution in the English editing of the article.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.06.005.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.