QUESTIONS OF RESONANCE

What does the future hold for human rights? Scholars offer numerous and competing predictions (Baxi Reference Baxi2008; Hopgood, Snyder, and Vinjamuri Reference Hopgood, Snyder and Vinjamuri2017; Moyn Reference Moyn2014; Rodríguez-Garavito Reference Rodríguez-Garavito2014a; Reference Rodríguez-Garavito2014b). A revisionist camp with roots in structural realist and critical theory traditions expects that the “lingua franca” of human rights will gradually lose its relevance.Footnote 1 The ideological export of a Western cosmopolitan elite, the human rights discourse has since its postwar incarnation grown only more professionalized, legalistic, and detached from the plight of the poor and downtrodden (Englund Reference Englund2006; Hopgood Reference Hopgood2013; Moyn Reference Moyn2018). As such, those seeking empowerment against the vagaries of global capitalism and other forces of domination may soon decide that “human rights is not the right language” for their struggle (Mutua Reference Mutua2008, 1034).

Another camp with allies in liberal and constructivist schools forecasts the opposite for the future of the discourse.Footnote 2 Human rights will continue to serve as a resilient and flexible tool of social movements worldwide (Chase Reference Chase2012; Stammers Reference Stammers1999), commanding an ever-expanding popular constituency that resorts to rights claims for self-empowerment and resistance to injustice in various forms (Benhabib Reference Benhabib2009; Simmons Reference Simmons2009). Therefore, one should expect a transnational human rights discourse to adapt, evolve, and thrive well into the foreseeable future (Dancy and Sikkink Reference Dancy, Sikkink, Hopgood, Snyder and Vinjamuri2017; Rodríguez-Garavito Reference Rodríguez-Garavito2014a; Reference Rodríguez-Garavito2014b).

Though ostensibly about the future, this debate is really about how to understand the current moment. Are human rights claims still relevant, or is the world on the cusp of a collective moving-on? There is much at stake here: if the human rights discourse is no longer salient, and thus fails to inspire mobilization on behalf of the oppressed, then investments should shift to developing more promising political programs. However, the truth is that it is difficult to generalize with confidence about the popularity of human rights. Worldwide, some populations are more likely than others to embrace the language of human rights. Therefore, to anticipate future trends, we must first ask a more fundamental question: what might explain the mass appeal of human rights in different contexts?

Some scholars have referred to wide uptake of the human rights vocabulary as resonance (see Chase Reference Chase2012; Reference Chase2016), which could be defined as the regular appropriation, adoption, or amplification of a reproducible language by a designated population. Any statements predicting a bright or bleak outlook for human rights, or discussing how the discourse gains or loses traction, presume knowledge about resonance. However, scholars are rarely forthcoming about how they arrive at that knowledge. In the words of Chase (Reference Chase2012, 506), “standard explanations in the literature explaining human rights’ resonance are insufficient.” Our goal is to confront this problem. We assume that an observable indicator of human rights resonance, which possesses an intersubjective dimension, is the degree to which a population demonstrates a collective interest in the subject. And, one way a group of people may convey collective interest in a subject is by regularly searching for it on the internet. Based on this assumption, we use Google aggregate search trends data to test competing hypotheses about where the human rights discourse will take hold and flourish.

This article proceeds in four parts. First, we identify how current scholarship makes claims about human rights without paying sufficient attention to the empirical validity of key assumptions. Second, we explain why Google aggregate search trend data can help us evaluate these assumptions, and ultimately resolve some problems of evidence that plague studies of resonance. In short, analyzing Google search data on “human rights” creates unique opportunities to capture the latent, or hard to observe, interests of populations over time, and to do so in a way that addresses shortcomings in archival and survey research.Footnote 3

Third, drawing on a wide array of literatures, we construct two predictive models of domestic human rights resonance. The top-down model treats human rights “talk” as a Western cultural script that is imposed on, transmitted to, or diffused across foreign polities through various channels of influence.Footnote 4 The bottom-up model presumes that human rights interest primarily evolves out of processes endogenous to those polities, including economic development or local resistance to repression. The advantage of these models is that they provide specific, testable hypotheses. The top-down model holds that cross-national variations are best explained by international factors, while the bottom-up model holds that those variations are rooted in domestic political and economic changes.

Our fourth move is to evaluate these models empirically. We start by examining broad temporal and spatial trends in human rights interest, and uncover a little-known fact: worldwide, the countries with the highest volume of web-based searches for human rights are not advanced democracies in the OECD, but chronically under-privileged developing countries in Central America and Africa. With regard to cross-national variations, we find that the most powerful correlates of human rights interest across countries are not factors like foreign direct investment from the Global North or transnational NGO campaigns. Rather, across the board, the search for human rights is most pronounced in countries where economic growth is afoot, and citizens are routinely subjected to state violence. In other words, the human rights discourse remains resonant, especially in places where it is needed most.

CURRENT SCHOLARSHIP

Thinkers fundamentally disagree over the nature of human rights. A great deal of that disagreement revolves around the perceived contributions of the human rights “project”—past, present, and future—to the aim of emancipation (Engle Reference Engle2021). The following two statements are illustrative:

Statement 1: “Social and political systems become hegemonic by turning their ideological priorities into universal principles and values. In the new world order, human rights are the perfect candidate for this role. Their core principles, interpreted negatively and economically, promote neoliberal capitalist domination” (Douzinas Reference Douzinas2008).

Statement 2: “Since the end of the Second World War, a wide range of social movements have sought to challenge existing forms of power…. Indeed … in the previous 60 years, it was the oppressed of the world—mobilized in and through social movements—who were the hidden authors of developments in human rights” (Stammers Reference Stammers2013).

Statement 1 interprets the discourse as hegemonic.Footnote 5 To this line of thinking, in a historical moment dominated by Western economic, military, and cultural power, human rights serve as a tool of subjugation to, or marginalization within, Empire (Hardt and Negri Reference Hardt and Negri2001). In this vein, contemporary critics charge that the human rights corpus: instantiates legacies of colonialism (Inayatullah and Blaney Reference Inayatullah and Blaney2012); reproduces neoliberal subjecthood and exploitation (Odysseos Reference Odysseos2010; Whyte Reference Whyte2019); justifies violent Western interventionism (Abu-Lughod Reference Abu-Lughod2002; Zizek Reference Zizek2005); supports liberal “do-gooding” and paternalism (Budabin and Pruce Reference Budabin and Pruce2018; Gourevitch Reference Gourevitch2009); reinforces white saviorism (Mutua Reference Mutua2001; Tascón and Ife Reference Tascón and Ife2008); or too easily becomes hijacked by right-wing forces (Perugini and Gordon Reference Perugini and Gordon2015). Central in these accounts is the notion that human rights are imbricated in structures of domination. At best, the language fails to empower activists in their struggle for more equitable social arrangements (Brown Reference Brown2004). At worst, it actively disempowers would-be agents of change by blinding them to alternative avenues for resistance (Engle Reference Engle2021). In the words of Kapur (Reference Kapur2014), human rights are something “we cannot not want, even though they cannot give us what we want.”

Statement 2 represents an opposite, counter-hegemonic orientation toward human rights, the logic of which is this: despite the fact that great powers like the United States played an influential role in the formation of the postwar human rights doctrine, and at times instrumentalize human rights in the conduct of foreign policy, the West does not own or control the discourse (Sikkink Reference Sikkink2017). Instead, human rights belong to the multitude (Hardt and Negri Reference Hardt and Negri2004). Those who mobilize this language do not constitute a vertical, elite-driven social movement, but a decentralized, polycentric, and multivocal amalgamation of subaltern movements (Baxi Reference Baxi2008; Chase Reference Chase2012; O’Connell Reference O’Connell2007; Stammers Reference Stammers1999). Aligned with this position are works that: recover the alignment between decolonization and the global human rights regime (Jensen Reference Jensen2016); document the use of human rights in community-based organizing against neoliberal policies (Dunford Reference Dunford and Schippers2019); recount how rights activists struggle doggedly against American militarism (Neier Reference Neier2012); theorize how populations engage in human rights localization, vernacularization, and reverse standard-setting (Acharya Reference Acharya2004; Destrooper Reference Destrooper2017; Merry Reference Merry2006); show how human rights movements have emerged even in localities insulated from Western cultural influence (Mokhtari Reference Mokhtari2009; Nickerson Reference Nickerson2020); and outline how existing movements amplified their message by adopting a human rights frame (Langlois Reference Langlois, Bosia, McEvoy and Rahman2020). Crucial in these accounts is the role of agency. Neither the content nor the utility of human rights claims is determined by power structures. Instead, the language can serve as an enduring resource for expressing political grievances and pursuing emancipation.

Whether one conceives of human rights discourse as hegemonic or counter-hegemonic will shape one’s predictions about discursive resonance. If human rights are an extension of American imperium, then the fragmentation and decline of American power will inevitably weaken the pull of rights claim-making worldwide (Hopgood Reference Hopgood2013, chap. 5). This is why Hopgood states that the “thing most likely to stall human rights progress is people around the world simply not considering them to be as important as their advocates would have us believe” (Hopgood Reference Hopgood2018). If, however, the human rights discourse is powered by a global constituency of local activists, then the decline of American power is unrelated to expectations about resonance. In response to Hopgood, Chase (Reference Chase2013) makes this exact point: “The impetus in defining human rights has long since ceased to be unipolar, if it ever was…. Human rights’ endtimes will only come when states no longer bother rebutting them and activists no longer seek to own them.”

How do scholars arrive at such divergent—often totalizing—interpretations? How do they know what they know? A first place they turn is philosophy. Assessments of the human rights discourse are driven in part by views on the nature of language and agency. Theorists differ over “whether people can use a discourse to accomplish their good aims, or whether discourses constitute people, and hence their aims too deeply for individual intention to guide their use” (Wahl Reference Wahl and Schippers2019, 15). One may hold that people instrumentally select human rights from a menu of claim-making grammars to pursue their goals, or one may hold that actors are in effect rendered choiceless by the all-consuming and productive force of human rights tropes. Insofar as these characterizations derive from a priori reasoning, they cannot be assessed with empirical research. However, it is likely that one’s ontological commitments are influenced, at least in part, by evidence drawn from the observed world (Wendt Reference Wendt1999, 35–6). A thinker cannot entirely decide what human rights mean, or what the future holds for human rights, if one has never seen human rights in action.

For evidence, some thinkers turn to a second place: history. Scholars use archival data on the original drafting and dissemination of human rights doctrine to draw inferences about its meaning today. A growing body of scholarship focuses on the historical precursors to human rights (Hunt Reference Hunt2008; Weitz Reference Weitz2019); the intellectual authors of human rights statements in the immediate postwar period (Borgwardt Reference Borgwardt2005; Glendon Reference Glendon1999; Sikkink Reference Sikkink2017); and the evolution of human rights norms, law, and advocacy in the decades following the Universal Declaration (Buergenthal Reference Buergenthal1997; Clark Reference Clark2001). The implicit assumption of this work is that the history of human rights provides insight into the way human rights presently operate. For example, much has been made of the simultaneous emergence of global rights advocacy and the rise of neoliberal orthodoxy in the 1970s (Moyn Reference Moyn2010). Some treat this historical fact as dispositive: it proves either that human rights help justify neoliberalism (Whyte Reference Whyte2019), or at the very least serve as its “powerless companion” (Moyn Reference Moyn2018). However, it is unclear whether the history of human rights is determinative (Alston Reference Alston2013). It is possible that human rights were once aligned with neoliberal hegemony but have since been appropriated and re-fashioned for counter-hegemonic purposes (Rajagopal Reference Rajagopal2006). For this reason, it might be a “futile quest to seek out the human rights foundation as a way to understand what human rights are today” (Chase Reference Chase2012, 514).

A third resource for assessing human rights is social science on contemporary practice. If one thinks of the human rights discourse as a market, most scientific studies focus on the supply side. Researchers shine light on the dynamics of norm promotion, detailing where transnational advocacy groups originate (Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink1998; Smith, Pagnucco, and Lopez Reference Smith, Pagnucco and Lopez1998); how transnational organizations are funded (Ron, Pandya, and Crow Reference Ron, Pandya and Crow2016); and in what ways international human rights NGOs behave strategically (Murdie and Bhasin Reference Murdie and Bhasin2011; Wong Reference Wong2012). These questions have inspired vigorous data collection efforts on human rights organizations and the mounds of written material they produce (Cordell et al. Reference Cordell, Clay, Fariss, Wood and Wright2020; Lebovic and Voeten Reference Lebovic and Voeten2006; Ron, Ramos, and Rodgers Reference Ron, Ramos and Rodgers2005). Based on what they know about the supply side of human rights, social scientists make guesses about who is consuming, or using, the human rights message. But in general, they possess very few details on this demand side of the equation. Some systematic case study research delves into the emergence and mobilization of human rights in widely disparate contexts such as Brazil (Dunford Reference Dunford and Schippers2019), China (Merry Reference Merry2006), Israel/Palestine (Perugini and Gordon Reference Perugini and Gordon2015), or Iran (Nickerson Reference Nickerson2020). However, much less attention is devoted to collecting valid cross-national data on human rights uptake. Instead, observers offer “reductionist” claims about the global (non)resonance of human rights based mostly on impressions or anecdotal data (Dancy and Fariss Reference Dancy and Fariss2017; Rodríguez-Garavito Reference Rodríguez-Garavito2014a; Reference Rodríguez-Garavito2014b).

One reason variations in resonance are under-studied is that overall interest in human rights is a latent population characteristic. It exists, but it is very difficult to observe directly. One way to capture latent population variables is to survey samples of that population. The most thorough cross-national survey study of public attitudes toward human rights is Ron et al.’s (Reference Ron, Golden, Crow and Pandya2017) Taking Root. The authors find that only a small portion of individuals in developing countries are directly familiar with the work of human rights organizations, though they generally trust rights defenders. The authors base this argument about exposure to human rights in the Global South on a total of 13,277 sampled individuals from six different countries: Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Nigeria, Morocco, and India (Ron et al. Reference Ron, Golden, Crow and Pandya2017, chap. 2). On the basis of these data, Ron et al. note the widespread familiarity with the concept of human rights, but worry that it is mostly elites who are ever exposed to human rights NGOs and advocacy networks. In a separate article, the authors claim that human rights are more “‘toproots’ than grassroots” (Ron, Crow, and Golden Reference Ron, Crow and Golden2013).

One benefit of sophisticated social science like Ron et al.’s Taking Root is that it produces precise results. Compared to philosophical interpretations, archival sources, or interviews drawn from convenience samples, randomized surveys allow for methodologically sound inferences about human rights knowledge and reception. However, two problems remain. The first is that surveys are limited instruments. They are frozen in particular geographical locations in particular moments. As such, it is difficult to use surveys to observe trends. It is simply not feasible to draw samples from all countries continuously over time, and thus we cannot know how or why interest in human rights changes (Mellon Reference Mellon2013). Even the World Values Survey, with its extensive geographic and temporal coverage, can only present us with a few data points related to rights for any given country, every few years. If we are to study the resonance of human rights, we need a reliable tool that at once provides more geographical and temporal coverage of discursive shifts. In the following section, we propose that Google aggregate search data is fit for this purpose.

A second problem is that the literature by and large still lacks a causal theory for why the language of human rights resonates in some populations but not in others. According to Gordon and Berkovitch (Reference Gordon and Berkovitch2007, 245), two of the only authors to confront this question directly, “very little research has focused on how human rights discourse surfaces in the domestic sphere.” What the literature does contain are two basic models—the top-down and bottom-up accounts of rights resonance—each of which might help us generate expectations about where, and when, interest in human rights will be most pronounced.

On the one hand, the top-down model treats human rights as a language whose worldwide popularity is attributable mainly to the influence of Western powers. Some authors characterize the spread of the discourse as a type of foreign “imposition” (Dicklitch and Lwanga Reference Dicklitch and Lwanga2003, 485), where others use more passive terms such as “transmission” or “diffusion” to describe how non-Western polities come to embrace human rights idioms (Goodman and Jinks Reference Goodman and Jinks2004, 673; Greenhill Reference Greenhill2010). Regardless of terminology, these accounts emphasize exogenous, outside-in factors to explain why the language becomes a more relied-upon source of political and legal claims in some contexts. On the other hand, the bottom-up model approaches this phenomenon from the opposite direction, often referring to the outcropping of human rights interest as organic and the development of human rights movements as “grassroots” or “from below.” While proponents of this model also recognize that the discourse of human rights is a widely available script attached to the liberal international order, they would still more likely explain variations in discursive resonance across countries by pointing to endogenous, inside-out, or local factors. Though similar to the opposition between hegemonic and counter-hegemonic conceptions, top-down and bottom-up accounts more readily lend themselves to empirical evaluation, as we will show. Before we develop testable hypotheses based on these models, however, we first turn to our method for utilizing Google aggregate search data.

GOOGLE AS METHOD

To address lingering questions about human rights resonance, we may need to explore new strategies of measurement and assessment. Google Trends data, which capture average internet search patterns among defined populations in time and space, may help fill gaps left by survey work. Google data are utilized widely in public health, economics, and media studies—primarily to measure information-seeking behavior and the trending concerns of large groups (Jun, Yoo, and Choi Reference Jun, Yoo and Choi2018). For example, Google searches are used to predict influenza epidemics (Ginsberg et al. Reference Ginsberg, Mohebbi, Patel, Brammer, Smolinski and Brilliant2009) and to forecast stock market swings (Preis, Moat, and Stanley Reference Preis, Moat and Stanley2013). In political science research, though, Google Trends data are not as commonly used as other sources of large-scale digital sources of information. Notable exceptions are Pelc (Reference Pelc2013), who employs Google search data to measure information-seeking about the WTO and global trade relations, and Kalmoe (Reference Kalmoe2017), who demonstrates that Google-driven news-seeking on drone attacks increases in the United States and Pakistan after major strikes on militant leaders. More germane to our topic, researchers have selectively used Google data to make arguments about media framing of human rights crises (Dabbous Reference Dabbous2018), or the “hidden impact” of International Criminal Court interventions on human rights salience in states under investigation (Dancy Reference Dancy2021).

Our aim is broader than most of these studies. We examine aggregate worldwide searches for “human rights” in the Google search engine across five different language groups: English, Spanish, Portuguese, French, and Arabic. In using aggregate Google searches as evidence, we make the following simple assumption: the more a defined population searches for “human rights,” the more that population possesses a latent interest in human rights as a field of knowledge and practice—ergo, the more the discourse resonates (cf. Foucault Reference Foucault1990, chap. 1). If our assumption is conceptually valid, then the aggregate search data are generated through the following four-step process: (1) individuals in a population jointly receive some cue that sparks their interest in human rights; (2) they turn to the internet to privately seek information; (3) when they do, they decide to use Google as a search tool; and (4) they key in “human rights” to begin learning or discovering resources. If any step in this data-generating process is broken, it casts serious doubt on our assumptions.

Throughout the article, we use Google search rates as a dependent variable. This publicly available measure is a transformation of publicly unavailable search ratios, which are the total number of Google searches containing “human rights” divided by the total number of all Google searches in a defined population for a particular time period. Notably, Google the company does not provide raw search totals to researchers; instead, the Google Trends tool offers data that are already transformed using min–max normalization (see Section A of the Supplementary Material for more details). The unit of analysis is the population-period, which we can define as global-week, global-year, country-week, or country-year. The observed population-period with the maximum ratio of human rights searches to all Google searches receives a score of 100. The observation with the minimum ratio of human rights searches to all Google searches would receive a score of 0. All other population-period values are defined in relation to these maximum and minimum values. This min–max transformation allows one to make relative comparisons across units but not with respect to the absolute number of Google searches.Footnote 6 Using search rates, countries are scored not by how wired they are, but by how much they look up a particular search term, “human rights,” relative to other search terms. In addition, because the denominator is total searches, the search rate indicators we employ control for variation in population size and internet penetration across countries.

A justifiable concern is that Google search rate is a simplistic indicator that cannot be validated (Mellon Reference Mellon2013). An indicator of what proportion of global country-wide searches contains the phrase “human rights” is seemingly a crude measure. Would it not be more advantageous to gather data on specific searches related to, say, torture or the right to food? To this point, a couple of facts. First, “human rights” is searched in high volume across the globe.Footnote 7 Figure 1 plots pair-wise comparisons, using min–max transformations, of various search terms at the global-week level over a 5-year period. Though not as frequently searched as terms such as time, war, god, or race, “human rights” is still far more commonly searched than quotidian political terms such as terrorism, national security, or social justice. To put it in perspective, “human rights” is Google searched in English about as often as malaria, a very common and dangerous disease.Footnote 8 The high volume of global searches for “human rights” every year makes for richer and more meaningful variations across cases in comparison to (1) other similar, high-volume search terms like torture, which also yields a flood of unrelated (often sadistic) content; or (2) specific, low-volume search phrases like right to food, which is seldom keyed in across cases in various languages.

Figure 1. Pairwise Comparisons of Relative Search Term Rates

Note: In each plot, the purple line represents the higher searched term relative to the green line that represents the lower searched term. Moving from left to right, in the top-left panel, the term “time” is searched more often than “war.” In the top-middle panel, the term “war” is searched more than “god,” and so on. The term “human rights” is searched slightly more than the terms “terrorism” and “malaria,” and more often than the term “injustice.”

Second, how do we know that individuals are not searching “human rights” because they view this discourse in a negative light? Might they key in “human rights are neo-colonial” or “human rights are pointless”? Of course, not all searches for human rights are positively motivated. However, Google Trends does provide tools for observing what additional search terms or phrases are most related to queries about human rights. These are called “co-occurrence” terms because they follow similar search patterns. In nearly every case we observe, aggregate interest in “human rights” is connected to information-collection on subjects like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the United Nations, and local Human Rights Commissions. Footnote 9 Collectively, individuals turn to Google not to dig up dirt but to learn and make connections about human rights norms and institutions (co-occurrence patterns are described in more detail in Section D of the Supplementary Material).

As it pertains to questions of resonance, collecting aggregate search data on “human rights” is not all that different from methods employed in other studies. Scholars make empirical arguments based on the presence of “human rights” in print media—including frequency of use in The New York Times and other Anglo-American periodicals through the twentieth century (Dancy and Fariss Reference Dancy and Fariss2017; Moyn Reference Moyn2010); the number of articles referring to “human rights” over a 13-year period in the Israeli newspaper Ha’aretz (Gordon and Berkovitch Reference Gordon and Berkovitch2007); or the number of references to “human rights” in four Filipino newspapers over a recent 4-year period (Chaudoin Reference Chaudoin2020). The difference between those studies and ours is that they are focused on human rights in the public sphere, while we focus on human rights interest at the private, individual level, which in the aggregate produces a measure of population-wide interest.

In this sense, Google search data are similar to survey data, but they have three comparative advantages. First, these data allow one to observe aggregate search totals down to the weekly level over a series of 5 years, yielding very detailed geographical and temporal patterns. For any given country, we possess hundreds of observations measuring the relative frequency with which the population uses Google to access information on human rights, as well as the city-wide and regional breakdown of aggregate searches. A second advantage is that, in most cases, people are typing “human rights” into their digital devices on their own volition, which means that aggregate data reflect individual cognitive impulses that drive the search for human rights. People will not admit certain things even on anonymous questionnaires, and their attitudes are often shaped by their interaction with survey scientists. Internet browser data offer a way around this source of error, to some extent (Stephens-Davidowitz Reference Stephens-Davidowitz2017).

A third and final advantage of Google search data is that they may be leveraged to evaluate theories that are panoramic in scope. Claims about the waxing or waning relevance of human rights can be sweeping, which trades off with empirical specificity. For example, Hopgood defines the endtimes of human rights by a general decline in the appeal of the global human rights discourse to address practical problems. But what exactly is the empirical expectation—a uniform and simultaneous dip in human rights interest across the globe? Or would the endtimes begin in certain countries or regions, only to become contagious? In what follows, we draw on the literature to develop precise hypotheses about human rights resonance in space and time, and we test these hypotheses using Google data.

THEORIES OF HUMAN RIGHTS RESONANCE

Why human rights, a concept of relatively recent vintage, catches on in some contexts—becoming politically salient, “localized,” or “vernacularized” (Acharya Reference Acharya2004; Merry Reference Merry2006)—remains an open question. We are aware of only a handful of studies that address variations in human rights uptake in comparative perspective (Gordon and Berkovitch Reference Gordon and Berkovitch2007; Ron et al. Reference Ron, Golden, Crow and Pandya2017). As a result, we have few empirical studies of resonance from which to derive expectations. That said, many accounts offer historically informed perspectives on the appearance and evolution of rights claims in certain contexts. We separate these into top-down and bottom-up accounts.

The Top-Down Model

The top-down model of human rights resonance echoes elements of the hegemonic interpretation of the discourse, framing its spread as outside-in or vertical. In this formulation, human rights ideals pulse from the Western heart of the liberal world order to that order’s hard-to-reach extremities. This transnational flow of ideas resembles a global hierarchy. Elites in the cultural and economic core gin up concepts like human rights, and then they transmit these concepts, via policies and institutions, to populations in the periphery—even when those populations are unprepared or unwilling to receive the message. But how? Building on the work of Goodman and Jinks (Reference Goodman and Jinks2013), we theorize that top-down transmission of human rights norms could occur through three main mechanisms of influence: material inducement, persuasion, or acculturation.

Material inducement entails states or institutions increasing the “benefits of conformity or the costs of nonconformity” with human rights ideals (Goodman and Jinks Reference Goodman and Jinks2013, 23). Traditionally, international financial institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank have a poor track record with human rights promotion. Structural adjustment programs put a squeeze on public goods provision, leading to protest and repressive violence (Abouharb and Cingranelli Reference Abouharb and Cingranelli2007). However, foreign direct investment by transnational firms is empirically associated with greater protection of human rights (Richards, Gelleny, and Sacko Reference Richards, Gelleny and Sacko2001). One reason is that investment firms demand devotion to rule of law, contract-enforcement, and political stability, of which human rights protections are an indicator (Blanton and Blanton Reference Blanton and Blanton2007). Organizations like PRS Group generate revenue by producing political risk rankings for investors. These reports incorporate information on rule of law and human rights practices.Footnote 10 Knowing this, government leaders in potential recipient countries might be inclined to adopt the human rights script, at the very least to maintain a veneer of compliance with international norms. For example, one study finds an empirical relationship between FDI inflows and pro-forma domestic criminal proceedings against human rights abusers in post-conflict settings (Appel and Loyle Reference Appel and Loyle2012). If it is true that government leaders publicly support human rights norms in order to attract investors, even if it is a cheap concession, this might rhetorically “entrap” leaders and open up new avenues for human rights mobilization (Risse and Sikkink Reference Risse, Sikkink, Risse, Ropp and Sikkink1999, 27). Therefore, we might expect the following hypothesis:

-

• FDI inflows hypothesis: Inhabitants of countries with higher FDI inflows should show greater interest in human rights.

The second hypothesis involves the role of human rights non-governmental organizations, or HRNGOs, that serve as instruments of persuasion by engaging in promotional campaigning. These bodies, which often operate transnationally, are usually seen as a primary agent of norm transmission from the West to the rest of the world (Mutua Reference Mutua2001). The number of operating transnational NGOs devoted to human rights increased dramatically in the late 1990s (Smith, Pagnucco, and Lopez Reference Smith, Pagnucco and Lopez1998). The modus operandi for these HRNGOs is information politics: to produce reports, stoke media attention, shine a spotlight onto abusive states, provide consultation, and ultimately, convince target states of the wrongfulness of their behaviors. Research shows that HRNGO campaigns are in fact persuasive (Korey Reference Korey1999). Murdie and co-authors discover that negative attention from HRNGOs is correlated with poorer opinions of government and higher numbers of protests (Davis, Murdie, and Steinmetz Reference Davis, Murdie and Steinmetz2012; Murdie and Bhasin Reference Murdie and Bhasin2011). However, HRNGOs do not target certain countries on the basis of need alone; they act strategically, in a way that boosts “market share” (Cooley and Ron Reference Cooley and Ron2002). For instance, HRNGOs are more likely to direct their information campaigns at countries that feature “hot” issues or high-profile conflicts, that gain widespread attention in other print media, and that have a larger number of local partner NGOs (Meernik et al. Reference Meernik, Aloisi, Sowell and Nichols2012; Ron, Ramos, and Rodgers Reference Ron, Ramos and Rodgers2005). This may strike some as a positive development, but others portray HRNGOs as playing an artificial and unevenly distributed constituency-building role in foreign countries. As such, these organizations are sometimes characterized as “agents of dissemination” in a kind of norm-promoting “industry” (Gready Reference Gready2010, 5). If it is true that HRNGOs effectively transplant ideas, but more so in the countries they target directly, then we might expect the following hypothesis to hold:

-

• NGO hypothesis: Inhabitants of countries that receive more attention from international HRNGOs should show greater interest in human rights.

A third mechanism of outside-in transmission is acculturation, which can occur in and through international human rights institutions. Though state participation in the human rights regime is voluntary, some argue that international bodies change behavior by serving as sites for socializing state actors into the prevailing order (Goodman and Jinks Reference Goodman and Jinks2013; Greenhill Reference Greenhill2010). This extends insights from sociological models that document processes of “global cultural homogenization,” of which formal human rights organizations are a critical part (Finnemore Reference Finnemore1996, 328). World Society theory holds that global culture gradually advances over time, leading to institutional isomorphism and decoupling; for instance, we should expect states to ratify more and more human rights treaties, incorporate identically worded rights provisions into constitutions, and establish similarly designed national human rights institutions—even when these actions are increasingly detached from local context (Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Boli, Thomas and Ramirez1997). The reason is that state actors seek to conform, behaving in line with dominant cultural scripts that favor governance practices centered around bureaucracy, markets, and individual rights. However, whether offering public commitments to international human rights norms is catalytic, filtering down into a population-wide human rights resonance, is an open question, and one often left unaddressed by state-centric, macro-sociological approaches. Some scholarship does find that human rights legalization exerts a gradual impact by inspiring domestic constituencies to mobilize and generate domestic legal reforms (Berlin and Dancy Reference Berlin and Dancy2017; Simmons Reference Simmons2009); by helping to translate a universal language of justice to the disempowered (Benhabib Reference Benhabib2009; Merry Reference Merry2006); or at a deeper level, by producing the concept of the “individual as an autonomous actor” (Finnemore Reference Finnemore1996, 332). Presumably, these trickle-down effects of international acculturation, if they exist, would be more pronounced in those states that have ratified more human rights treaties, making the international legal discourse more available to their own citizens. Thus, the following expectation:

-

• Human rights regime hypothesis: Inhabitants of countries with more commitments to international human rights agreements should show greater interest in human rights.

The Bottom-Up Model

A great deal of research also questions whether these top-down mechanisms of human rights promotion—FDI, transnational NGOs, or human rights treaties—have any observable impact (e.g., Clark and Kwon Reference Clark and Kwon2018; Hafner-Burton Reference Hafner-Burton2008; Posner Reference Posner2014). But if it is not top-down dissemination that makes the discourse resonate, then what does? An alternative bottom-up theory holds that interest in human rights emerges primarily when local conditions are ripe. The discourse diffuses and roots down in various contexts because it serves a useful function for social movements and agents of change. Therefore, the adoption of human rights is not caused by actors or institutions in the global core, but an outgrowth of local political causes struggling to reach a wider audience. For instance, even though they emphasize the important role of transnational advocacy organizations from the Global North, Keck and Sikkink (Reference Keck and Sikkink1998) fit into the bottom-up approach because they argue that local actors are the prime movers in the boomerang model of human rights pressure. According to this model, concern for human rights starts with the efforts of local civil society, who in the face of domestic obstacles, seek outside assistance. This is more likely to happen in situations of dire need, when physical integrity violations are rampant.

If human rights interest is diffuse, but does not travel through lines of transmission from the top down, then what would predict the appropriation of the human rights idiom in any particular context? Two ancillary theories may assist in generating cross-national expectations. The most influential of these is modernization theory, which holds that “economic development produces systematic changes in society and politics” (Inglehart and Welzel Reference Inglehart and Welzel2010, 553). This account is prominent in research on endogenous democratization. Neo-institutionalists posit that the desire for seventeenth-century English wealth-holders to secure property rights against the sovereign generated constitutional rule of law (North and Weingast Reference North and Weingast1989). The lesson is that that rights claims thrive in moments when old elites’ economic power weakens, and with it their political control. Extrapolating, one may use this theory to explain fluctuations in rights-based claim-making. As new pockets of wealth emerge in a country’s economy—for example, a growing middle class—so too do rights claims and demands for public goods. This is rooted in the individual desire to protect property from government expropriation. Previously disenfranchised out-groups with new wealth will “demand political concessions in return for tax compliance” (Ansell and Samuels Reference Ansell and Samuels2010, 1549).

North and Weingast’s contractarian version of the historical emergence of rights is focused on elites, and may not necessarily explain why a discourse of human rights might become widespread in a nation. A second version of modernization theory does consider the “role of ordinary people” in linking economic growth to liberal democracy. Inglehart and Welzel’s (Reference Inglehart and Welzel2010) “mass priorities” account holds that with economic growth in a society comes less everyday worry over “existential security,” (553) and more “emphasis on self-expression values—a syndrome of trust, tolerance, political activism, support for gender equality, and emphasis on freedom of expression…” (557). This package of concerns—which correlate strongly with economic development and technological advancement—echoes human rights ideals. It is not a stretch, then, to think that economic growth may also inspire ordinary citizens eager for self-expression to explore the concept of human rights.

-

• Economic growth hypothesis: Inhabitants of countries experiencing sustained economic growth should show greater interest in human rights.

A second endogenous explanation is similar to the first, with the exception that it is not exclusively materialist. In short, human rights claims emerge organically in domestic political interactions, but these need not be determined by deeper economic structures. This kind of formulation might be found in literature on social movements. Essentially, one may conceive of human rights as one claim-making technology in a larger repertoire of contention, which “comprises what people know they can do when they want to oppose a public decision they consider unjust or threatening” (della Porta Reference della Porta, Snow, Porta, Klandermans and McAdam2013, 1). Human rights claims take their place alongside other tools in the arsenal of collective actors challenging the legitimacy of certain governing actions.

When applied to actual examples, those who subscribe to this human rights-as-resistance model see state repression and rights expression to be mutually reinforcing. In the Swedens of the world, where individual dignity is generally respected by government and where any incidents are transparently reported and addressed, there is not a pressing need to mobilize around protection of human rights (Eck and Fariss Reference Eck and Fariss2018). However, in the Zimbabwes of the world, where citizens live in fear of their governments, and do not trust courts to act as neutral arbiters of disputes, people look to human rights as an external resource for individual and legal empowerment, precisely because human rights are not dependent on a flawed domestic constitution. Though not a grammar of violence, human rights do embody a radical proposition: that local government should be reformed or replaced in line with internationally defined norms. In circumstances where government resorts to unauthorized violence, human rights become a logical language of resistance. Theoretically, this aligns with Donnelly’s (Reference Donnelly2003) argument that rights claims themselves are self-liquidating: where rights are respected, human rights claims cease; inversely, where rights are not respected, human rights claims abound.

The resistance model explains a number of findings within comparative scholarship. Some scholars discuss how transnational human rights movements emerge in response to lack of reform (Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink1998), while others presume regimes follow a “law of coercive responsiveness” (Davenport Reference Davenport2007). Under this law, governments are reactionary, responding to protests and other challenges with violence when it strengthens their hold on power. Because government violence and human rights mobilization so often coincide, it is hard to know which is causally prior. Yet regardless of whether governing elites or resistors are the prime movers in the repression-resistance cycle, the empirical expectation should be the same:

-

• Human rights violations hypothesis: Inhabitants of countries with more human rights violations should show a higher interest in human rights.

EMPIRICAL EVALUATION

Global Search Rates

How is relative interest in the human rights discourse distributed across time and space? We answer this question, and thus test the hypotheses produced by the top-down and bottom-up models, by studying trends in aggregate Google searches. Put simply, in which countries are people most prone to input Google searches containing “human rights,” relative to people in other countries? To investigate, we examine search data from 109 countries across five language groups: English, Spanish, Portuguese, French, and Arabic. We use the data produced to empirically evaluate theories about cross-national variations in human rights interest over the 5-year period between 2015 and 2019.Footnote 11 For the English language group, we study searches for the term “human rights,” and for other language groups, we analyze searches for the most common translation of the phrase. For example, in Spanish, the search term is “derechos humanos,” and in Arabic, it is “huquq al-insan.”

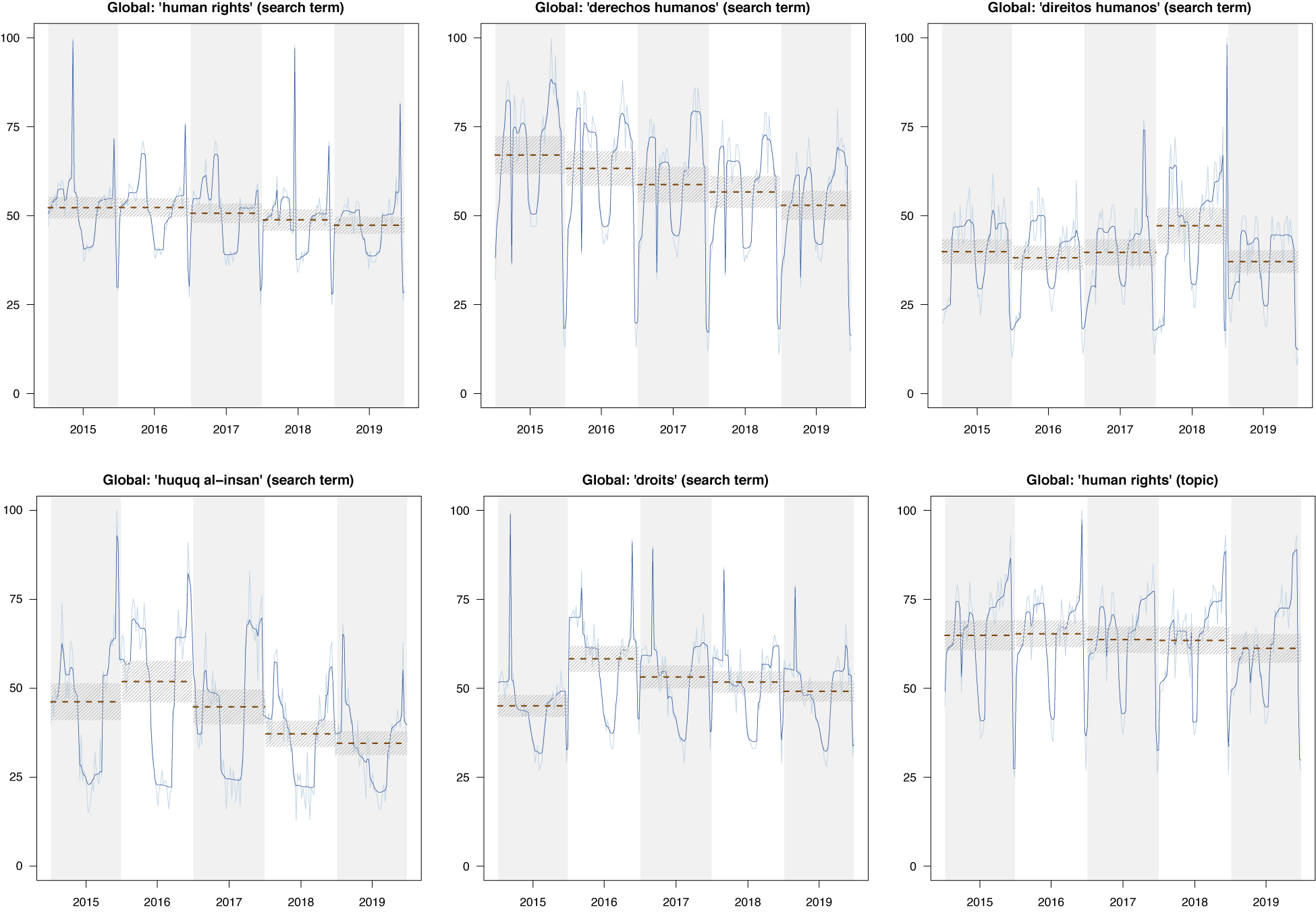

Figure 2 plots weekly search rates for each language group over a 260-week period.Footnote 12 The y-axis is the min–max value indicating how much searching there is at the global level across all weeks. High values, and peaks in the trend, mean that there was more searching in a given week compared to all other weeks on the x-axis. Two things to note are, first, that the smoothed global trend in human rights searching is relatively flat. It is not appreciably increasing or decreasing over this period of time, in any language.Footnote 13 Second, human rights searching appears to be seasonal. While it increases in the spring and fall, it decreases during the mid-summer and in December. It is yet unclear why this is the case.Footnote 14

Figure 2. Global Weekly Search Rates from Google Trends for Five Language Groups (2015–19)

Note: Absolute comparisons of the global rate are valid within each figure but not between figures because of the min–max transformation described above (95% CI). Relative comparisons of change in the trend over time are possible between panels. Note that the human rights topic (lower right panel) pools searching across language group. In Section C of the Supplementary Material, we present global trends for other 5-year periods: 2012–16, 2013–17, and 2014–28.

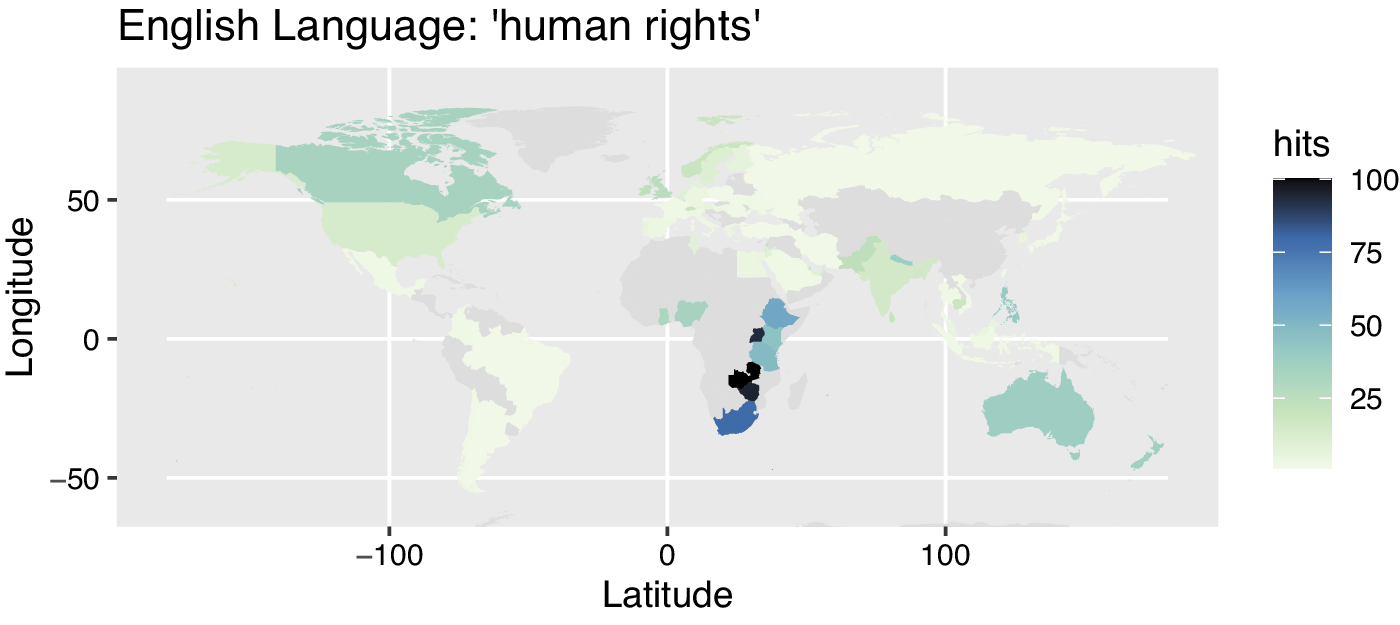

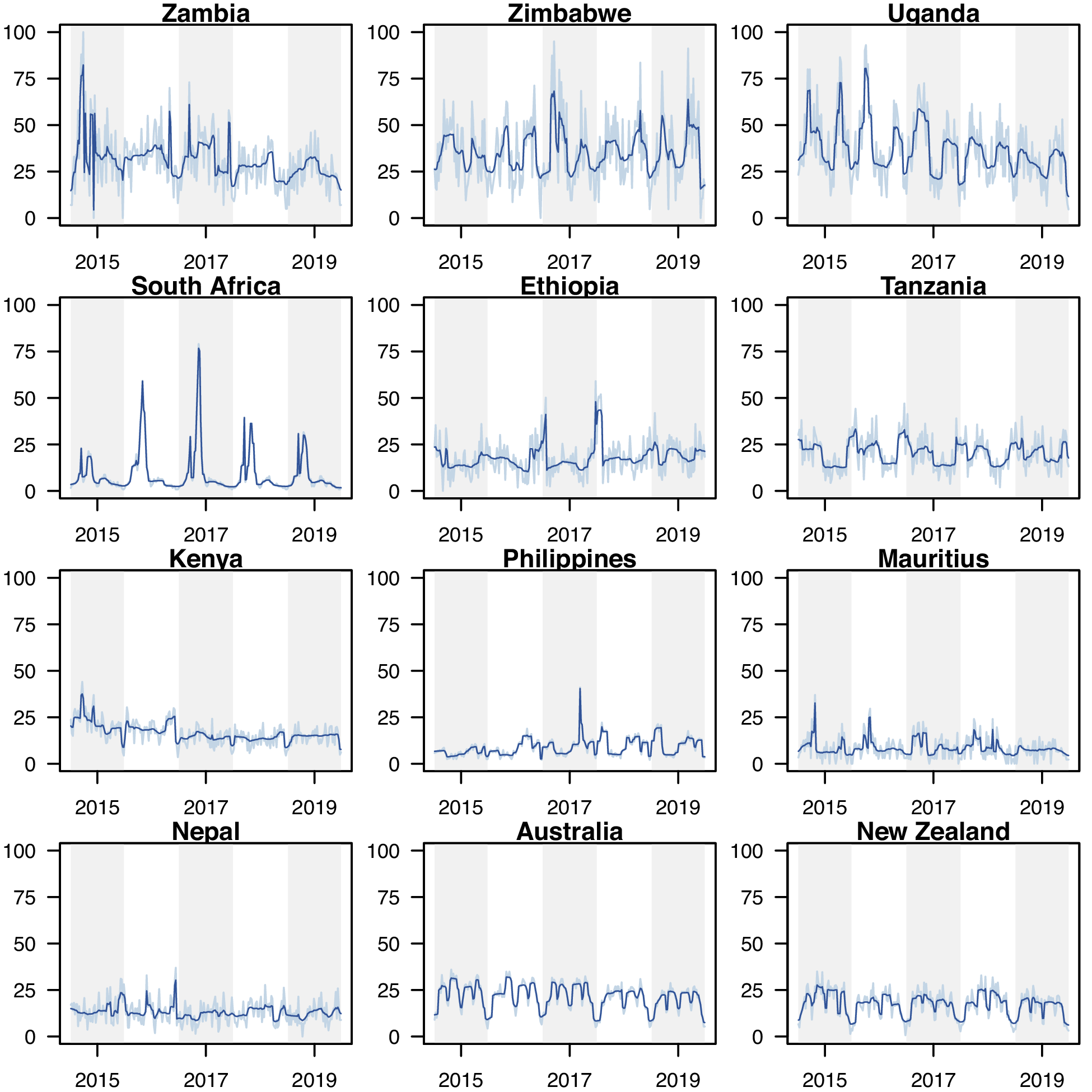

We further analyze temporal trends in aggregate searches across different countries, in order to locate which populations are the top searchers in each language. Our initial expectation was that the most searches for human rights would be located in OECD countries, which are wealthy, educated, and filled with university students and professionals in the NGO sector. This expectation is wildly off the mark. Figures 3–6 present the geographic distribution and the list of top searchers in English and Spanish, respectively.Footnote 15 Almost universally, human rights interest is most pronounced in countries in the Global South. In English, the three populations with the most relative searching for “human rights” are in the sub-Saharan countries of Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Uganda. The United Kingdom and the United States do not make the top 12 searchers presented in these figures. The United Kingdom is 17th on the list, and the United States is 28th, behind Bangladesh and Qatar. In the Spanish language group, the top five searchers are Central American states. Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and Mexico are ranked 1–4. Argentina, which has formerly been referred to as a “global human rights protagonist,” is all the way down in the 15th position (Sikkink Reference Sikkink2014).

Figure 3. Map of Google Search Rates for “Human Rights” in the English Language

Note: Darker colors indicate a higher relative rate of searching compared to other countries conducting the same search. The rectangular projection (i.e., Plate Carrée projection) is defined by equally spaced parallels, equally spaced straight meridians, and is true to scale at 0 latitude.

Figure 4. Rate of Google Searches for “Human Rights” in the English Language across Country-Weeks, 2015–19

Note: Top 1–12 countries displayed in descending order.

Figure 5. Map of Google Search Rates for “Derechos Humanos” in the Spanish Language

Note: Darker colors indicate a higher relative rate of searching compared to other countries conducting the same search. The rectangular projection (i.e., Plate Carrée projection) is defined by equally spaced parallels, equally spaced straight meridians, and is true to scale at 0 latitude.

Figure 6. Rate of Google Searches for “Derechos Humanos” in the Spanish Language across Country-Weeks, 2015–19

Note: Top 1–12 countries displayed in descending order.

Figure 7. Coefficient Plot of Results from Regression Models with Language Fixed Effects

Note: The search mean, search median, and search max dependent variables are measures of the yearly mean, median, or max of the country-week search rate value. Independent variables are measured annually for each country-year unit (2015–19). Lines represent 90% and 95% confidence intervals.

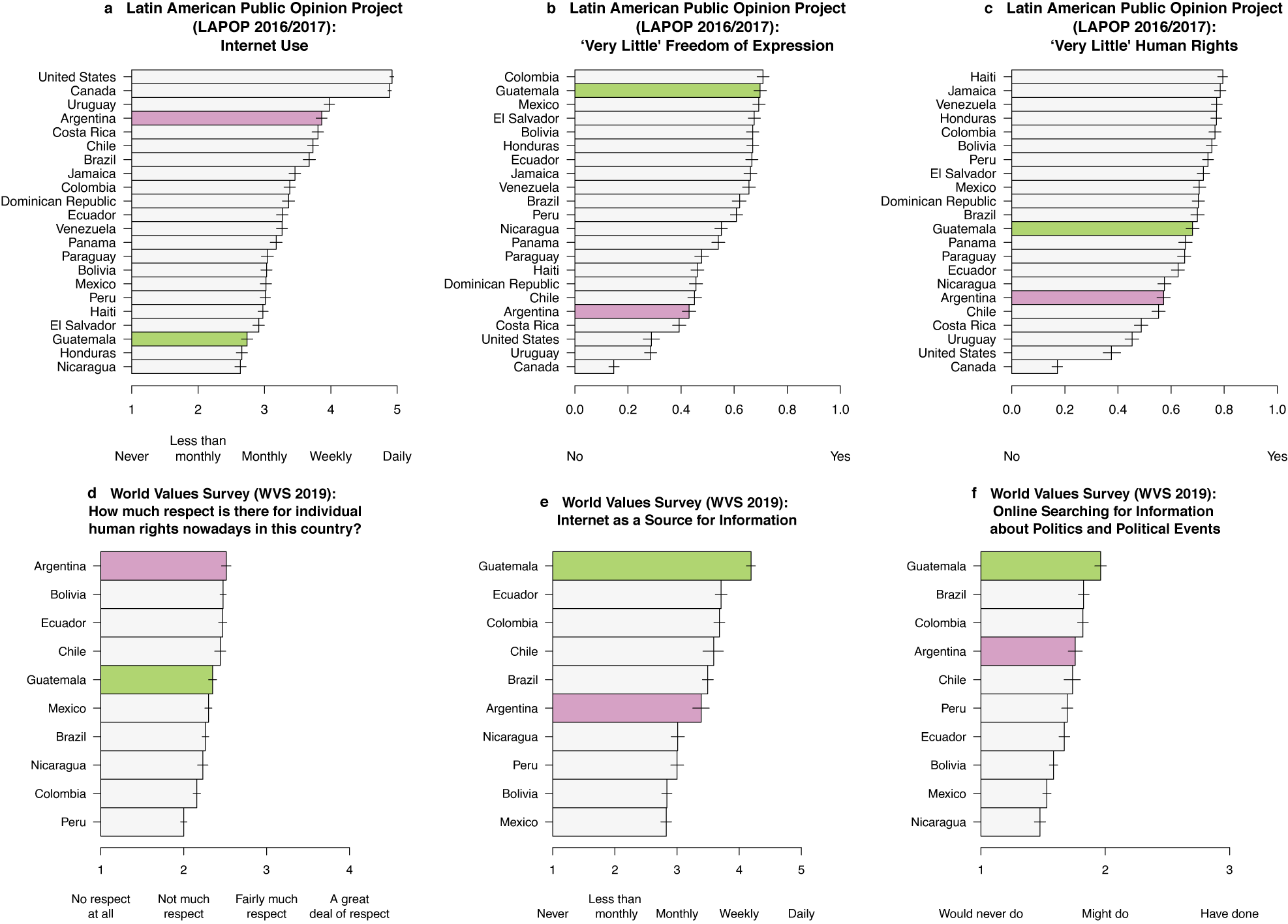

Figure 8. Human Rights Survey Validation

Note: We compare country-level averages of subject response rates by question across two surveys for their most recent waves for LAPOP in the top row (administered in 2016–17) and the World Values Survey wave 7 in the bottom row (administered in 2017–20). We highlight and compare Guatemala (green) and Argentina (pink). Guatemalans are at the top of the list for use of the internet as a source of information generally, and information about political events.

Figure 9. Google Search Proportions

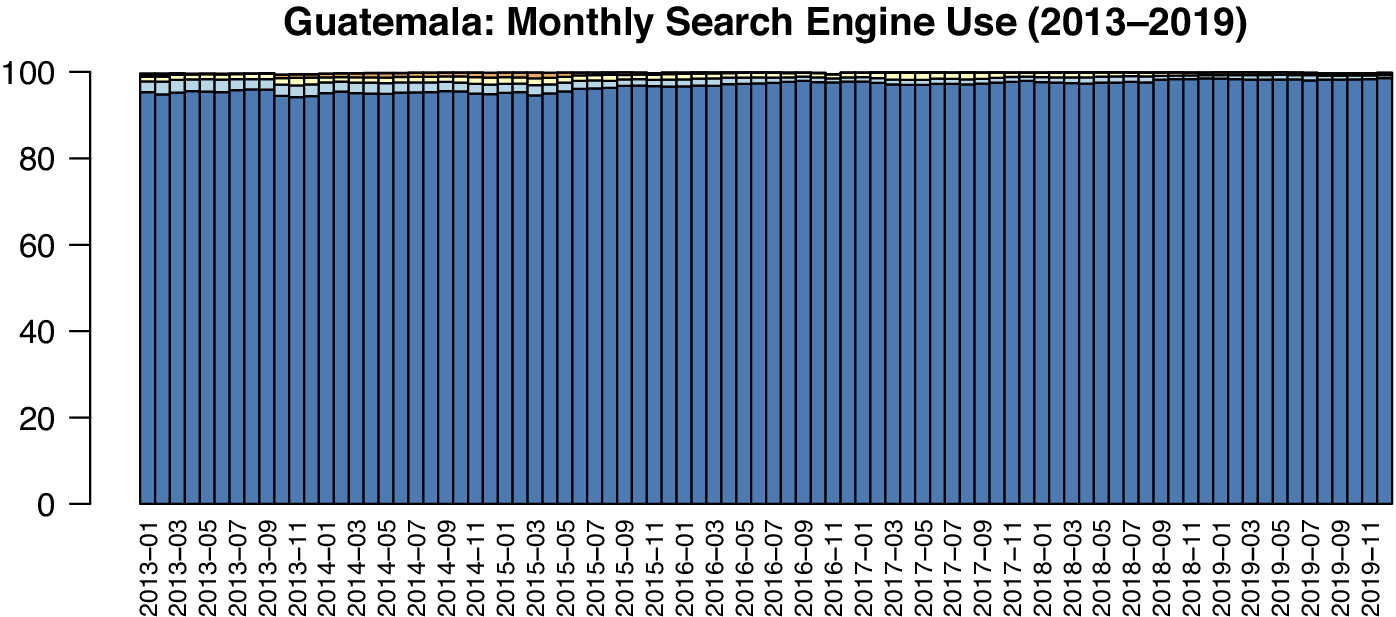

Note: Google search (dark blue) dominates all other search engines (all other colors) for all regions of the world. In Guatemala, Google accounts for approximately 94.5%–98.5% of search requests. Data are taken from the statcounter Globalstats website: https://gs.statcounter.com/search-engine-market-share/all/guatemala#monthly-201301-201912 (last accessed: February 12, 2021).

Figure 10. Related Co-occurring Search Queries and Search Topics for Guatemala (Top Row) and Relative Search Rates by City and Region (Bottom Row)

Note: Rates are relative to 100 for human rights as a topic (left panel) and the search term “derechos humanos.” A google “query” is equivalent to a “search term” as we have used the term and is language specific. Topics are based on bundles of related search terms and are language agnostic. Google does not provide full information about the process by which they create topics, so we have focused most of our analysis on natural language search terms (queries).

One way of synthesizing these findings is that populations in the Global South are steady-state searchers, plugging the phrase “human rights” into Google’s engine on a more regular basis than populations in the Global North. This, we argue, represents a difference between sustained human rights interest and passing curiosity in headline events. Take Guatemala and Uganda, which across all 5-year samples are consistently in the top three most interested in human rights. Though we know neither the raw total of net Google searches nor the actual number of human rights searches made by Guatemalans or Ugandans, we do know the relative rate of these searches. Based on calculations of rate, we draw comparative inferences. For example, an average Ugandan searches approximately 7.3 times for human rights every one time an average American does.Footnote 16 And individuals in Guatemala on average search 10 times more often for derechos humanos than do individuals in Spain. This wide gap between Global South countries and countries in the Global North is striking, and it leads back to our central research question: what determines variation in human rights interest across countries?

Cross-National Variations

Why are Guatemalans and Ugandans top searchers for human rights in Spanish and English? The theories we outlined above offer very different answers. The top-down model would hold that these countries likely receive the most pressure from foreign investors, attract more attention from NGOs, or interact more with the international legal regime. The bottom-up model would probably chalk up the prevalence of human rights discourse to growing GDP, or to upticks in levels of political repression and violence.

Here, we analyze which expectations bear out across cases. We generated a dataset including five years of observations for each language-country-year in our sample. Each panel of this dataset includes yearly aggregate Google searches in each language spoken in a given country over the period 2015–19. For every single country-year observation, we record three different Google measures. Search mean represents the average weekly Google search rate for a country in an entire year. Search median is the median weekly Google search rate for each country in year. And search max is the maximum yearly search rate. Higher values on each of these variables indicate that inhabitants of a particular state more regularly search for “human rights” each week over an entire calendar year compared to populations in other states. The range of values for search mean is 0 to 68, with a standard deviation of 13.37; the range of values for search median is 0 to 68.5, with a standard deviation of 13.68; and the range of values of search max is 0 to 100, with a standard deviation of 25.1. These measures are meant to capture the latent interest in human rights in different countries (see Section B of the Supplementary Material for descriptive statistics).

The reason that we use yearly aggregates for our dependent variables is that doing so places greater emphasis on sustained attention, rather than short-term spikes in interest. The United States would score high for 1 week in the summer of 2018—when family separations on the Mexican border became headline news—but the United States regularly scores low on search mean, search median, and even on search max, because its average yearly values are much lower than the values in this single week. This, we argue, is because the U.S. population has lower latent human rights interest compared to populations in other states.

To assess the hypotheses presented above, we estimate a regression model, with a fixed effects parameter for each different language group. We include six independent variables. The first, FDI inflows as a percentage of total GDP, we take from the World Bank. The second, Amnesty report rate, is defined by the number of Amnesty International’s (AI) reports published on a country in any given year, per one hundred thousand residents of that country.Footnote 17 Because AI is one of the two foremost HRNGOs in the world (with Human Rights Watch), this measure should capture the degree to which a country is subject to global human rights campaigning. To derive this indicator, we scraped Amnesty’s website and built a corpus of over seventy-five thousand documents, including news reports, background reports, and urgent actions, among others. We used AI’s own labels to determine which country is covered in each publication. Amnesty report rate is more extensive and more updated than other similar variables used in the literature, which either rely on specific sub-samples of AI written content or are available only through the early 2000s (Ron, Ramos, and Rodgers Reference Ron, Ramos and Rodgers2005). Third, we include a measure of total human rights treaty ratifications (HR treaties), which we derive by summing the number of ratifications each country has made to the 27 agreements listed by the UN Treaty Collection as promoting human rights. These include signature agreements like the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, but also lesser-known agreements like the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance.Footnote 18 Fourth is a measure of percentage GDP growth, also drawn from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators. Finally, we include a variable called HR violations, which is the inverse of Fariss’s normalized Human Rights Protection Scores (v4) data; for our models, the higher the score, the more regular government violence is directed at a country’s inhabitants (Fariss Reference Fariss2014; Reference Fariss2019; Fariss, Kenwick, and Reuning Reference Fariss, Kenwick and Reuning2020).

A final measure that we include is a control variable called Internet censorship. A valid concern with our research design is that searching for human rights will be less prevalent in countries like China, where the central government makes a concerted effort to limit internet access, or to block certain information from users. Three points here. First, China is not a case in our cross-national statistical models, but not because it fails to respect internet privacy. It is excluded because we only include searches in language groups that span a variety of countries. Doing so provides us with variation to analyze with statistics. Chinese-language Google searches overwhelmingly occur in only three countries: China, the United States, and Malaysia. That does not give us much leverage when considering covariation with other state-level variables. Second, we can examine the “China problem”—that internet control would affect Google searches for human rights—by examining its effects in other cases. This is why we include the Internet censorship variable, derived from the Varieties of Democracy Project.Footnote 19 It captures how much, in practice, states’ governments filter the internet.Footnote 20

Figure 7 visualizes results from the three models, and Table 1 presents coefficients and levels of significance. The first thing to note is that some expectations derived from the top-down model are supported, but not in overwhelming fashion. FDI inflows are statistically insignificant in all but the third model, suggesting that countries with higher FDI inflows are no more or less likely to show greater mean interest in human rights, though they are associated with greater yearly maximum searches. Given the small magnitude of these findings, however, one might say that material inducements do not seem to exert much influence on human rights uptake in a country.

Table 1. Country-Year Regression Analysis with Language Fixed Effects

Note: Models include a fixed effects parameter for each language group (Spanish, Portuguese, French, English, and Arabic). Search mean, search median, and search max dependent variables are measures of the yearly mean, median, or max of the country-week search rate value for each country-year unit. Independent variables are measured annually for each country-year unit. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Amnesty report rate is positive and statistically significant in all three models, meaning that the more a country is targeted for exposure by groups like Amnesty International, the more that country’s population searches for human rights in Google, on average. While this is grounds for rejecting the null NGO hypothesis, we still urge some caution in interpreting this result. For one, the substantive significance of the Amnesty report rate coefficient is fairly small: a one-standard-deviation change in Amnesty reporting leads to just a 0.3-point increase in mean or median search rates (the rate DVs range from 0 to 100 points). But also, additional tests show this finding to be sensitive to variable operationalization and model specification; in robustness checks, some models produce findings in the opposite direction, and others yield statistically insignificant coefficients (see Section L of the Supplementary Material). The relationship between NGOs and measurable interest in human rights certainly warrants further investigation, but at the very least, it does not appear that the work of Western NGOs is a primary driver of human rights resonance across the globe. Finally, disconfirming the expectations of the top-down model, the effect of HR treaties is statistically indistinguishable from zero. It does not seem to be the case that embeddedness in the human rights regime, on its own, drives collective interest in human rights.

The bottom-up models’ expectations appear more on the mark. The GDP growth and HR violations variables perform in the model as expected, and their substantive effects are more robust than the other variables. In contexts where the national economy is growing, there are more people regularly searching “human rights” on the internet. This is the second most powerful predictor in the model, judged by magnitude; a one-standard-deviation change in growth corresponds with around a 0.9-point increase in mean human rights search rates.

By far the most powerful predictor in the model, though, is HR violations. A one-standard-deviation increase in this variable leads to a 1.9-unit increase in Google search rates. By comparison, this effect is 2.2 times greater than GDP growth, and 6.4 times greater than the effect of Amnesty reporting. This finding is robust to every single model we have specified, and it is not conditional on external inducements or persuasion. For instance, to account for the possibility that human rights interest spikes precisely in scenarios with a combination of external pressures and internal repression, we specified a set of models with an interaction between HR violations and Amnesty report rate (see Section L of the Supplementary Material), only to find that the interaction is negative and statistically significant in all models.

Another set of models incorporates an interaction between HR violations and HR treaty ratifications (see Section L of the Supplementary Material). This variable is positive and statistically significant in the three main models. So while the embeddedness of a country into the human rights treaty regime has no independent effect on the local appeal of the discourse, that is, it does not affect all populations evenly, it does magnify the relationship between government violence and interest in human rights throughout the population (e.g., Simmons Reference Simmons2009). This finding validates world society theories, but only in part (Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Boli, Thomas and Ramirez1997). Human rights as a legal and cultural script have spread nearly everywhere, but people are more likely to access that script in situations of acute need (cf. Law Reference Law2018; Merry Reference Merry2006). While not the final word on the matter, we take these results as evidence that concern for—or interest in—human rights is mostly generated within countries, when government violence is an everyday reality.

Measurement Validity

Our findings show that human rights is a discourse meant to directly challenge excesses of state coercion. It is not a leap to think that people facing widespread violence would seek out ways to empower themselves, and that they would do so in private on the internet. In short, the reason that we see more searches for human rights in countries of the Global South is that these countries are in the greatest need of rights. However, these findings may be legitimately challenged from the perspective of measurement theory. How could it be that these data capture an actual social process? To check the validity of the theory and the measures used to test the hypotheses, we introduce additional case study evidence to study the links of the four-step data-generating process described in the “Google as Method” section. We focus specifically on Guatemala, one of the top human rights-searching countries in the world.

Step 1 is interest-formation. Are Guatemalans concerned about human rights because of government repression? Indeed, evidence from a Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) survey in 2016/17 (Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) 2020) suggests that Guatemalans demonstrate a high level of concern for lack of freedom of expression, second only to Colombia in the entire region (see Figure 8b). Moreover, there is strong evidence that actual repressive events are correlated with higher human rights search rates. Section M of the Supplementary Material presents an analysis of weekly level data on government violence against civilians and Google searches. One can see a statistically significant lagged relationship: number of government-initiated violent events in a week is associated with more searches for human rights in the following week. These data, while preliminary, establish support for the mechanisms driving our causal theory; people respond in real time to cues, in this case real instances of state violence, by seeking information about human rights on the internet.

The second step in the data-generating process is use of the internet. While the same LAPOP survey project from above finds that Guatemalans use the internet much less than other countries in Latin American on average (Figure 8c), World Values Survey wave 7 data from 2017 to 2020 (Haerpfer et al. Reference Haerpfer, Inglehart, Moreno, Welzel, Kizilova, Diez-Medrano and Norris2020) show that Guatemalans are at the top of the list for use of the internet as a source of information generally, and information about political events specifically (Figure 8e,f). Note that the World Values Survey was conducted in Guatemala in 2019, 3 years after the LAPOP survey was conducted in 2016. These data suggest that while on average Guatemalans use the internet more sparingly than citizens in other countries, when they do, they search for political news and information at a higher rate.

The third step in the process is use of Google. Evidence suggests that Guatemalans overwhelmingly use this search engine when scouring the internet. Particularly over the period 2013–19, Google’s share of searches in Guatemala compared to other browsers is over 94.5%–98.5% across all monthly periods (Figure 9).Footnote 21

The fourth and final step involves information-seeking. What are Guatemalans looking for when they type “human rights” into the Google search bar? The Google Trends portal suggests that the queries most related to “human rights” searches in Guatemala are what are human rights, declaration of human rights, human rights inspector, and the interamerican court of human rights. Related search topics compiled by Google Trends include Law, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, American Convention on Human Rights, and Constitution (Figure 10).Footnote 22

All of this evidence suggests that the data-generation process assumed by our theory is plausible, and that we are capturing facets of that process with our independent and dependent variables. However, one problem remains. Even if this is true, Google aggregate data may still lack representativeness. After all, internet access is not equally distributed within states. Therefore, it could be that searches for human rights in developing countries are driven primarily by urban city-dwellers, students, and visitors from abroad working in the NGO sector. This certainly is a possibility. However, concentration of interest in major cities does not accurately describe Guatemala, where searches for human rights are distributed widely across the country. The cities that top the list of searchers are Huehuetenango and Cobán. These metros are one-tenth the size of Guatemala City, and each was a site of extreme violence during the civil war in the 1980s and remain a hotbed for indigenous protest and repression. This lends further credence to the theory that collective interest in human rights—expressed by population-wide searches in Google—responds to government abuse.

CONCLUSION

It is now in vogue to say that we are heading into a “post-human rights world” (Strangio Reference Strangio2017). But this revisionist claim is seldom grounded in good evidence. In this study, we have used Google aggregate search data to answer a little understood question: do human rights still resonate, and if so, where? We find that, by and large, the most human rights-interested populations, defined by the willingness to search for the phrase human rights in Google, are located in the Global South. People in countries like Uganda, Zambia, Mozambique, Guatemala, and El Salvador seek information about human rights at far higher rates than their counterparts in the United States, the United Kingdom, and even Argentina.

Why? The answer is not that rights ideals are being pushed onto them by neo-imperial Western actors, nor that rights uptake is a direct product of the international human rights regime. Instead, the answer is more straightforward: people show more interest in human rights when they are subject to coercive regimes, and, just like the malaria search validation demonstrates, people look to the internet for details about how to protect themselves. In the end, the language of human rights continues to appeal where people need rights the most. This fact has so far eluded direct observation, even though it appears to be a major point of dispute. Interdisciplinary scholarship on human rights is consumed with high-level debates over the nature of the discourse. Now ascendant is the posture of human rights “endism” (Teitel Reference Teitel, Sajó and Uitz2020). Here, it is worth reiterating how “serious people around the world…are not particularly impressed by the human rights criticism that has been recently formulated in academic debates” (Mahlman Reference Mahlman, Sajó and Uitz2020, 69). On the ground, the oppressed still seem to want human rights.

Though our findings dispute currents of thought that frame human rights resonance as a top-down phenomenon, they cannot be used to reach definitive conclusions about the hegemonic or counter-hegemonic nature of the discourse. For instance, the discovery that economic development is associated with country-wide interest in human rights could easily be construed as a function either of neoliberal hegemony or of anti-neoliberal counter-hegemony: one may surmise that domestic elites who benefit from liberalization increasingly mobilize rights to protect their assets, or alternatively, one could posit that the economically dispossessed use human rights to resist their marginalization by forces of globalization. Of course, it is also possible that human rights are simultaneously “beneficial for both hegemonic and counterhegemonic projects” (Perugini and Gordon Reference Perugini and Gordon2015, 17). Our data are simply too limited to weigh in on this matter. However, what we can say is that the concrete linkage between government violence and internet searches for human rights, which is evident at the yearly and weekly levels, strongly hints at a counter-hegemonic role for human rights.

Still, more research is needed. For instance, how is internet searching on government violence associated with social mobilization, collective action, and protest? And is it possible that interest in human rights is skewed by domestic class politics? In other words, might it be that domestic internet users are drawn to certain grammars of resistance, while those who lack access to the web are drawn to others? We cannot yet speak directly to these questions, and our hope is that theorists of human rights discourse will collaborate with empirical scientists in the future to devise innovative new strategies of evaluation.

Returning to the issue of what the future holds for human rights, we note an irony. Because human rights claims are clearly linked to government abuses, it could very well be that the democratic recession, the rise of authoritarian populism, and other global challenges will only expand reliance on the human rights discourse in the future. In this sense, a trend toward more engagement with human rights claims might be an indicator of stalled progress. Conversely, if measures are taken to improve human rights protections, the prevalence of human rights talk may dwindle. If this is the case, it means that a contracting human rights discourse worldwide would be a sign that events are on a path toward improvement. Whichever is the case, we can only say that these and other pressing matters should not be left to guesswork, but to research using the best evidence available.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055423000199.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at a Github reproduction archive maintained by the authors (https://github.com/CJFariss/Human-Rights-Search) and at the APSR Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/AV0CMJ.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This article was presented at the 2018 meeting of the International Studies Association, the 2019 meeting of the Peace Science Society (International), and seminars at Arizona State University, University of Georgia, the Conflict and Peace, Research and Development (CPRD) group at the University of Michigan, and University of Southern California. We would like to thank all of the participants at these talks and also Therese Anders, Molly Ariotti, Miriam Barnum, Megan Becker, Chad Clay, Rebecca Cordell, Justine Davis, Mark Drumbl, Micah Gell-Redman, Ben Graham, Mai Hassan, Murad Idris, Patrick James, Steve Jensen, Jonathan Markowitz, Menaka Philips, Sarah Shair-Rosenfield, Kathryn Sikkink, Wayne Sandholtz, Henry Thompson, Reed Wood, Thorin Wright, Htet Thiha Zaw, and Kelly Zvobgo for many helpful comments and suggestions.

FUNDING STATEMENT

G.D. acknowledges research support from The Gender, Justice and Security Hub, a project sponsored by the UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) through the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF). C.J.F. acknowledges research support from the Social Science Korea (SSK) Human Rights Forum, the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea, and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2016S1A3A2925085).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors affirm this research did not involve human subjects.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.