In 1621, the soldier Juan de Carmona went to visit a Ternaten herbalist of great renown called Don Juan in the streets of Intramuros Manila. He was looking for a charm that would help him win at gambling. Don Juan told him that to be successful, Juan de Carmona had to kill a crow and remove its heart. But try as hard as he might, Juan de Carmona could not capture a crow. He returned to Don Juan with some gunpowder, but the Ternaten herbalist was similarly unsuccessful. Don Juan prepared a substitute luck charm involving powdered roots, but still Juan de Carmona remained unlucky at gambling. He threw the powders in the river in despair.Footnote 1 This seemingly innocent story of a hapless gambler seeking fortune against fellow soldiers reveals a great deal about the levels of cultural mestizaje that took place in early modern port cities like Manila. In this interaction between a Spanish soldier and the Ternaten herbalist we find evidence for the convergence of Spanish, Moluccan, and Philippine beliefs, superstitions, and herbal knowledge. This convergence was repeated on an almost daily basis as members of the Spanish communities of Manila, Cebu, and Cavite looked for magical solutions to help them in affairs of the heart, to win at gambling, to determine the theft of lost objects, or to divine their own fortunes.

This article, based on 98 Inquisition cases held by the Archivo General de la Nación in Mexico, explores the extent of folk magic in early modern Manila as an example of the cultural mestizaje that occurred between Asian communities and the small population of Spaniards living in the archipelago.Footnote 2 The types of practices explored here—love charms, luck charms, spells of influence, divination—had their origins in early modern Europe and were found across the Spanish empire in the seventeenth century. Yet, in these Philippine cases, Spaniards and other Europeans sought out the expertise of Asian healers, herbalists, and spell-casters, as well as native priests and priestesses. Through these cases we witness the emergence of a new frontier culture which connected European folk traditions with Asian knowledge of botany, medicine, and spirituality to fulfil the needs of the Spanish community for magic.

Folk magic practices were extensive across the breadth of the early modern Spanish empire and consistently demonstrate a blending of Spanish folk beliefs with indigenous or African cultural, botanical, and medical knowledge.Footnote 3 There is consequently an extensive historiography that deals with these practices in both Europe and Latin America.Footnote 4 Where historians of folk magic in Spain have viewed these practices as challenging the religious authority of the Catholic Church,Footnote 5 colonial Latin American historians have been more interested in the way Inquisition records reveal daily contestations of colonial power by Indigenous and African communities.Footnote 6 This article combines both approaches. Within a frontier setting like colonial Manila, folk magic challenged racialised colonial hierarchies and religious authority at the same time. While Southeast Asian practitioners of folk magic used their practices to reclaim power within colonised spaces, the almost daily interactions between these practitioners and Spanish consumers of folk magic created a cultural mestizaje which undermined the pious imperialism of the Spanish colonial state. Folk magic thus offers a unique lens for exploring in unprecedented detail both interactions between Europeans and Southeast Asians as well as the instability of colonial power within a frontier society.

‘Folk magic’ is used here as a loose translation of the Spanish term hechicería, which encompasses a myriad of superstitious or magical practices used by Spanish communities across the empire to mediate relationships between people in matters of love, health, or fortune.Footnote 7 Although the Spanish Inquisition considered hechicería as a type of witchcraft, unlike the more serious accusation of brujería, it did not involve an explicit pact with the devil.Footnote 8 There are only two official instances of brujería in the Philippines between 1611 and 1639.Footnote 9 By contrast, hechicería was an almost daily practice for many. Despite provoking a large number of denunciations, these cases rarely resulted in a formal trial or punishment since the Inquisition did not consider hechicería a particularly serious infraction of religious law.Footnote 10 Nevertheless, hechicería was inherently subversive of established religious norms. As the Spanish historian María Tausiet writes, ‘magic and religion were two sides of the same coin’ and were blended together within the urban environment of early modern Spain such that many superstitious practices evoked the name of God, the Virgin Mary or other saints.Footnote 11 This cultural intertwining of magic and religion increasingly concerned religious authorities in the post-Reformation period, when Catholicism was deployed as a doctrine designed to encompass all earthly stages of life, replacing superstition within births, marriages, sickness, health, and death.Footnote 12 The introduction of Spanish folk magic into colonial spaces added new ethnic and cultural dynamics to the practices that proved subversive to colonial rule, especially since the majority of those providing hechicería services were not of European origin.Footnote 13 Historians of hechicería in colonial Latin America have also shown that such practices became a venue for the subversion of racial and gendered hierarchies. Women—particularly African, indigenous, and mestizo women—were able to use hechicería to reclaim power within colonised spaces.Footnote 14

By contrast to colonial Latin America, both folk magic and the broader role of the Inquisition in the Philippines remain under-explored. Until very recently, the defining works on the Philippine Inquisition was a book published in 1899 by José Toribio Medina and an article published in 1980 by F. Delor Angeles.Footnote 15 Both works are institutional histories; while witchcraft and magic are not mentioned by Medina at all, Delor Angeles argues that these cases were not considered important by Philippine inquisitors and were rarely ever pursued.Footnote 16 By comparison, the ground-breaking work of Romain Bertrand shows how Inquisition cases can be used as novel ethnographic sources to explore complex social relationships between Spaniards and their Philippine subjects. Bertrand uses a particular 1577 witchcraft trial to unravel the social and political world of the Spanish Philippines at the end of the sixteenth century. He demonstrates that such cases enliven our understanding of internal political tensions, the process of colonisation, the interweaving of European and indigenous knowledge systems, and the private lives of the inhabitants of Manila and Cebu.Footnote 17 This article follows the path opened by Bertrand, while a larger set of Inquisition cases leads to wider conclusions about the role of magic in everyday life within Spanish cities in the Philippines.Footnote 18

At the same time, the study of folk magic practices invites new reflections on the nature and extent of colonial domination. Within the fragile frontier society of the colonial Philippines, authorities were worried about the way that heterodox ritual practices within settler communities undermined the authority of the Catholic Church. Spanish imperial ideology has been described as a form of ‘pious’ or ‘messianic’ imperialism, where Catholicism was central to Spanish colonial rule.Footnote 19 This article explores in detail the unravelling of this ‘pious imperialism’ on the colonial frontier. Across the empire, Spanish officials sought to construct racialised hierarchies that emphasised the differences between Spaniards and their colonial subjects.Footnote 20 While this process often took the form of spatial segregation,Footnote 21 Rebecca Earle has shown that cultural practices were also important for the assertion of authority over colonial spaces: ‘individuals demonstrated their Catholic or indigenous status through their daily practices and were either confirmed or rejected in these performances by the other members of their community.’Footnote 22 Similar observations can be made about the central role of religious practice in establishing colonial rule. Mina García Soormally has recently argued that Spanish imperial ideology constructed a binary between Christian Spaniards and their colonised subjects by categorising indigenous customs and beliefs as idolatrous, ‘the remains of a subjectivity that, once colonized, becomes sinful, erroneous and false’.Footnote 23 Daily expressions of religious piety were both an important part of Spanish cultural identity and a means of asserting authority over indigenised spaces. Hechicería was doubly subversive of these goals, introducing an ambiguity into Spanish religious beliefs within intimate settings that incorporated indigenous actors, blurring the rigid cultural boundaries between coloniser and colonised.

These findings may seem surprising within a historiography that emphasises how Spanish religious practices—often narrowly defined as equivalent to the actions of Spanish missionaries—were adopted and adapted by Philippine indios, and not the other way around.Footnote 24 Yet, the widespread appearance of folk magic within the Inquisition record reveals something quite different about quotidian cultural practices among the Spanish community of Manila. Outside the formal structures of the Catholic Church and the religious orders, Spaniards demonstrated a surprising receptiveness and respect for Asian spiritual and botanical knowledge. Spanish women in particular sought the intervention of indigenous women to help them navigate their stormy relationships with their husbands, their lovers, and sometimes their lovers’ wives. These indigenous women were often themselves renowned spiritual leaders and healers, suggesting an even greater depth to the respect that some members of the Spanish community afforded them. For their part, indigenous healers and herbalists, native priestesses, and a group of noble Ternaten captives found novel ways of integrating into Spanish society through the exercise of their botanical, medical, and spiritual knowledge.

To explore the place of folk magic in early modern Manila, this article begins by unpicking the role and meaning of magic for the Spanish community in Manila, and the varying motivations of individuals for engaging in hechicería. I explore the European origins of many of these practices as well as the influence of traditions imported from New Spain via the Manila galleons. This discussion then allows us to understand the particular ways in which Asian botanical, medical, and spiritual knowledge was incorporated into Spanish folk magic. While Spaniards showed a particular respect for Philippine knowledge of medicines and poisons and their magical applications, the case study of the buyo—or betel nut—demonstrates how this cultural mestizaje manifested itself. The final section reflects on how these practices disrupted and influenced the processes of colonisation and Catholic conversion both in Manila and the provinces. Spanish religious authorities sought to repress folk magic at the same time as they were struggling to contain indigenous ‘idolatry’ and apostasy. Ultimately, folk magic practices among lay Spanish communities demonstrate that the goals of ‘pious imperialism’ were not shared by all settlers, contributing to the formation of new frontier cultures that drew upon both indigenous and European traditions, practices, and beliefs.

Hechicería in seventeenth-century Philippines

In 1633 Ana María began an illicit affair with the powerful and wealthy maestre de campo Don Lorenzo de Olasso, who showered the young woman with gifts and promised to lift her out of poverty.Footnote 25 Over the course of this romantic tryst, Ana María used herbs to kindle passion in her lover, placing them in his mouth while they were in bed together. When her husband was returning on the galleon after having been in New Spain for a year and a half, Ana María worried that she would be punished by him for her extramarital affair with Don Lorenzo. She sought help from the Visayan woman Monica de la Cruz, who gave her some oil with amber, musk and other pungent things as a remedy to make Ana María's husband love her well.Footnote 26 Ana María's case is typical of the types of hechicería practices that took place in seventeenth-century Manila. While women like Ana María relied on the help and knowledge of indigenous intermediaries such as Monica de la Cruz, they also drew upon folk magic traditions that extended across the empire. Before discussing the influence of Philippine and other Asian healers and magical practitioners on Spanish folk beliefs, it is worthwhile examining the European and Mexican origins of some of these practices.

Taken together, the 98 Inquisition cases examined here allow us to build a picture of just how widespread hechicería was among the Spanish community. These cases took place between 1611 and 1639 and involved 115 individuals accused of engaging in 154 acts of hechicería. In the majority of cases (65 per cent), these individuals brought themselves before the Inquisition, usually because they were told to by their confessor or in response to an edict condemning certain types of superstition. Nearly two-thirds (62 per cent) of those accused were men; however, women were more likely to be denounced by someone else (42 per cent of women compared to 24 per cent of men). The vast majority of accused (73 per cent) were of Spanish ethnicity, with 11 per cent categorised as mestizo, 10 per cent of Portuguese or other European origin, and just 6 per cent of non-European ethnicity. The complete absence of Philippine indios from these statistics reflects the fact that indigenous subjects of the Crown were exempt from the jurisdiction of the Inquisition from 1571, the year Manila was founded.Footnote 27

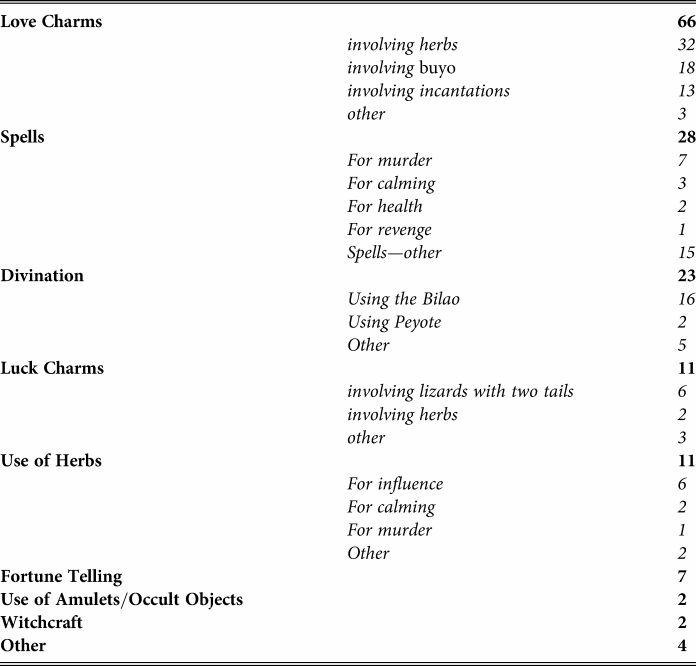

Within these cases we typically learn of the strained relations between men and women, of the widespread nature of extramarital affairs, of domestic violence, and the wooing tactics of unwed soldiers. Love magic was the most common form of hechicería (see table 1), often allowing women to reclaim their own forms of power within a highly gendered space.Footnote 28 Historians of superstition and love magic have noted a surprising commonality in practices across early modern Southern Europe in the signification of certain spells and rituals and the use of herbs, bodily fluids, and other objects to achieve their desired purpose.Footnote 29 As Jeffrey Watt has noted for early modern Italy, love magic followed certain ritualistic rules and languages—beans could be thrown in the fire, holy words might be written down or recited, powders and herbs could be used, wax statues might be created to symbolise the desired lover. Hair, nails, and bodily fluids were also often used, sometimes gifted to a lover, consumed with other mixtures, or buried under or near the house of the object of desire.Footnote 30 Tausiet notes that it was almost unimportant if such magic worked, as the purpose of love magic was to ‘enable people to give free expression to their cravings and desires, to provide a form of catharsis for the desperate and, above all, to create an emotional support network among members of one gender facing the insoluble problems of communicating with those of the other’.Footnote 31 Numerous historians have catalogued these same practices across diverse colonial settings, from New Spain to Guatemala, Lima, and even frontier regions like New Mexico where Ramón A. Gutiérrez argues love magic was ‘simply part of the colony's sexual dynamics, with its large numbers of single Spanish soldiers, many Indian women, and an exploitative context in which conquering men could assert their manly desires without much restraint’.Footnote 32

Table 1. Types of hechicería recorded by the Manila Inquisition, 1611–39

Sources: This table records 154 individual acts of hechicería involving 115 individuals. The data is sourced from 98 Inquisition cases from the following archival repositories: AGN, Mexico City, Indiferente Virreinal, caja 1766, exps. 27, 28; caja 2721, exps. 3, 17; caja 3436, exp. 50; caja 3466, exps. 15, 17, 18, 24, 25; caja 4052, exps. 9, 29; caja 4128, exps. 11, 12; caja 5425, exps. 3, 45. AGN, Inquisición, vol. 220, exp. 8; vol. 293, exps. 37, 65, 70, 72, 73, 74; vol. 298, exp. 10; vol. 333, exp. 16; vol. 336, exp. 1; vol. 355, exps. 25, 30, 31, 32; vol. 362, exps. 8, 33; vol. 461, exps. 8, 13.

In a similar vein to the New Mexican frontiers, soldiers and sailors were among the principal users of love magic in seventeenth-century Manila.Footnote 33 They commonly sought out charms made of herbs, hairs and other bodily fluids, and other substances to help them in their pursuit of both Spanish and indigenous women. They often shared recipes and information about love charms amongst themselves, although very rarely did any of these charms have any reported effect.Footnote 34 Most of these cases read very similarly to that of the hapless Thomas de Ribas who heard from a mestizo soldier about a herb that grew along the seashore. This friend collected this herb, mixed it with a bit of sesame oil and musk and told Thomas to dab the concoction on his hair at the front. Thomas tried this six or more times but it had no effect, so he smashed the bottle.Footnote 35

Love magic was also used by members of the Spanish elite. In rare instances, charms were sought to help with finding a suitable spouse. Such was the case with nineteen-year-old Doña Josepha de la Rossa y Cépedes who in 1621 used oils, roots and incantations, taking a handful of sand as she bathed in the sea while naming her desired husband.Footnote 36 In 1634, Doctor Luis Arias de Mora sought the help of several women when he was having trouble convincing the relatives of his lover to allow them to marry. He took powders mixed with chocolate, read out incantations in the Malay-language for eight days in a row, and allowed various spells to be performed using his hairs, but all to no avail.Footnote 37

Love magic was more commonly used in the pursuit of extramarital affairs, particularly by Spanish women. The historian of early modern Lima, María Emma Mannarelli, has noted that sex outside of marriage was both commonplace and widely tolerated.Footnote 38 Hechicería records suggest that this also was the case for early modern Manila. Women placed herbs inside their lovers’ clothes to woo them, or beneath their husbands’ pillows to make them sleep soundly while their wives engaged in illicit affairs.Footnote 39 Some men then complained that they had been bewitched by the women that they were sleeping with. Nicolás Bolen denounced Juana de Medrano for bewitching him into having an affair after dabbing him with a herb and some oil, and convincing him to lay with her while her husband slept soundly next to them in the same room. Nicolás felt that for six months he could go nowhere—not even to Mass—without Juana nearby and reported this as evidence of great bewitchment.Footnote 40 In 1626, Tomás de Villanueva reported that he had been sick with love for a married woman, unable to eat or sleep, and driven crazy. He paid four pesos to a black man who brought him some roots and told him to chew them and spit them at the woman. He tried this but it did not work. Another black woman called Andrea told him that he should cut some of the hairs from the woman and throw them out of the window, but this did not help either. After a period of time his affliction stopped on its own.Footnote 41

For some women, these affairs were important ways of supporting themselves, as was the case with the widow Francisca Díaz, who used buyo leaves tied together with thread and a piece of paper with words written in Malay to win back the affections of a man who had been providing for her.Footnote 42 When such affairs went awry, love magic also offered a solution. The widow Doña Catalina del Castillo sought revenge on a former lover with the help of an india called Juana Opa, who performed a spell using some eggs roasted in the fire and some of the man's undergarments.Footnote 43 Other women sought help in the form of spells or charms that would influence the mood of their husbands and lovers.Footnote 44 Gloria de Sufiño went in search of a remedy for a husband who beat her, and was given a herb which was said to be good for controlling anger. She was told to place this herb under her stairs, but before she could put the plan into action, her husband caught her and whipped her.Footnote 45

Much of this love magic adopted the same ritual symbolism described by historians of early modern Europe. We can see this most clearly in the use of bodily hairs and fluids, which were often a common component of love magic. In 1635, the soldier Gerónimo Díaz de Figueroa heard another soldier called Hernando Perea, a native of La Palma, say that to make a woman love a man it was necessary to take the seed of a man and the milk of a lactating woman and dab them on the chosen person.Footnote 46 Hairs, toe nails, flakes of skin and other bodily fluids were commonly added to other ingredients to make up love charms, spells of influence or other charms. Several Spanish women reported learning common incantations that appear elsewhere in the empire in this period. When they were still children, the three sisters Helena, Leonor and María all learned a love incantation from Gineta Bernal, the wife of an artilleryman, which began ‘with two I see you, with three I bind you, I drink your blood, and your heart I break’.Footnote 47 The same charm was used by Isabel de Zuñiga after she fought with her husband, to try to make him love her again.Footnote 48

While love magic was the most common form of hechicería practised in seventeenth-century Philippines, it was not the only type (see table 1). Aside from their pursuit of romantic interests, soldiers were also concerned with increasing their luck at gambling and sought out oils and other charms that might help them win.Footnote 49 A common story among them was that a two-tailed lizard was the ultimate lucky charm—a belief that appears to be found in both Asian and European cultures.Footnote 50 Many soldiers in Manila would wear them under their shirt sleeves while gambling.Footnote 51 In 1623, the soldier Juan Diaz Baptista recalled hearing some talk among the soldiers that if a lizard with two tails was placed in a pot with milk with the head face down, a stone would appear which would bring luck to anyone who took it gambling. He tried this, but only succeeded in killing the lizard, which he then dried out and wore beneath his shirt. He gambled with this lucky charm three or four times and always lost.Footnote 52 Several cases mention the existence of Chinese or Japanese fortune tellers, who typically used palmistry to tell the future fortunes of an individual.Footnote 53 However, the most common divination practice found amongst the Manila inquisition records also has its origins in Europe. This ritual, repeated over and over again in seventeenth-century Manila as a way of identifying a thief, always followed the same pattern.Footnote 54 A bilao—a Filipino sieve or woven winnowing basket—was placed on top of a pair of scissors and the names of the suspected thieves were read out. When the thief's name was spoken, the bilao would shake. Known as coscinomancy, this ritual has its origins in Ancient Greece and was widespread across early modern Europe.Footnote 55

While European practices were clearly transported into the Philippines, there is evidence that Spaniards and Mexican mestizos brought with them types of magic and herbal knowledge from New Spain. At times this happened in the port itself, as with Cristóbal de la Cruz who admitted to visiting a woman in Acapulco and acquiring some herbs that could be used as a love charm, although he claimed he threw them overboard before reaching Manila.Footnote 56 Chocolate was imported into Manila and its popularity among the Spanish community meant that it could sometimes be used to mask the taste of a potion.Footnote 57 For instance, the slave Brigida accused her mistress Doña María de Saldivar of murdering her husband by hiding certain powders in his chocolate. He died after taking this mixture three times.Footnote 58 Knowledge of peyote was also transferred to the Philippines from New Spain and is mentioned in several cases as an aid to finding lost items of missing people.Footnote 59 In 1623, the alcalde of the gaol in Manila, sergeant Juan de la Oliva, reported that one of his prisoners had escaped. A Mexican mestizo soldier called Bartolomé de Leon advised him that taking the herb peyote wold give him certain visions and allow him to know where the prisoner was. Juan de Oliva asked Bartolomé to take the peyote for him, but although Bartolomé had many frightening visions, the experiment did not bring them closer to finding the missing prisoner.Footnote 60

The Philippinisation of Spanish folk beliefs

While these practices drew upon folk magic traditions from early modern Europe, they also incorporated new traditions developed by the largely non-European providers of hechicería services. Within these cases, 128 individual practitioners of hechicería provided access to services such as procuring herbs, providing incantations or other prescriptions for love or luck charms, performing spells or divination ceremonies, and fortune telling. In contrast to the accused, these practitioners were overwhelmingly of Asian ethnicity (see fig. 1). While Philippine indios make up the largest single grouping of practitioners (39 per cent), Ternaten healers and herbalists comprised perhaps the most significant group involved in these activities. Many of these Ternatens maintained some connection to the household of the King of Ternate, who had been captured by the Spanish and imprisoned in Manila following their invasion of the Maluku Islands in 1606.Footnote 61 Hechicería offered these hostages a way of earning a living and subverting their captive status. While practitioners were more likely to be female (56 per cent), the large number of male practitioners suggests that this was less of a gendered pursuit than in other imperial contexts.Footnote 62 Spaniards wishing to acquire hechicería services typically met these practitioners close to home. While some individuals like the tribute collector Diego de Vargas and the alférez Miguel Nuñez de Torres met local herbalists while travelling in the provinces,Footnote 63 soldiers were more likely to encounter them within their companies.Footnote 64 Elite women used their servants and slaves to introduce them and their friends to hechicería practitioners elsewhere in the city.Footnote 65 The almost complete absence of Chinese people among the practitioners only confirms this view, since Chinese access to the Intramuros of the city and the private lives of its inhabitants was severely restricted.Footnote 66

Figure 1. Practitioners of hechicería in Manila by recorded racial category, 1611–39

Notes:

(a) Includes indios (23), Visayans (12), Pampangans (2)

(b) Includes Japanese (4), Moros (2), Bengali (2), Javanese (2) Ambonese (1), South Asians (1)

(c) Includes Mestizos (5), Mexican mestizos (1), Ternaten mestizos (1), Philippine mestizos (1)

(d) Includes Negros (3), Cafres (2), Mulatos (2)

Sources: The 98 Inquisition cases studied for this article recorded the race of 94 individual practitioners; a further 34 practitioners were identified but with unknown race. See AGN, Indiferente Virreinal, caja 1766, exps. 27, 28; caja 2721, exps. 3, 17; caja 3436, exp. 50; caja 3466, exps. 15, 17, 18, 24, 25; caja 4052, exps. 9, 29; caja 4128, exps. 11, 12; caja 5425, exps. 3, 45. AGN, Inquisición, vol. 220, exp. 8; vol. 293, exps. 37, 65, 70, 72, 73, 74; vol. 298, exp. 10; vol. 333, exp. 16; vol. 336, exp. 1; vol. 355, exps. 25, 30, 31, 32; vol. 362, exps. 8, 33; vol. 461, exps. 8, 13.

The materiality of hechicería practices mattered and this fact offers some insight into why Europeans sought out Asian practitioners of hechicería. As Tausiet argues, ‘the idea of the physical embodiment of the sacred in all kinds of symbols (statues, crucifixes, talismans, magic circles and so on) is essential to an understanding of the mindset of the period’.Footnote 67 The majority of love charms or other spells incorporated herbs and other locally-sourced substances and objects that were thought to have innate powers to achieve the desired ends. As newcomers to the Philippine environment, Spaniards relied on the botanical, medical, and spiritual knowledge of Asian practitioners to access this new magical frontier. The Asian practitioners of Spanish hechicería were able to mediate this knowledge and adapt it to the needs of the Spanish community.

Hechicería practitioners drew on the theatrical and ritualistic material culture that was central to pre-Hispanic Philippine religious practices. Philippine communities believed that the world was guided by both ancestors and spirits who were often embodied within the natural world in the form of trees, plants, animals, or sacred sites. These spirits were responsible for the health and fortune of individuals and local communities and guided the success or failure of important events such as harvests, hunting trips, or warfare. Regular ritual ceremonies were performed in order to placate this spirit world.Footnote 68 Such ceremonies were typically conducted inside houses and involved an animal sacrifice—usually of chickens or pigs but also occasionally deer or carabao—followed by a feast involving the whole community.Footnote 69 During the sowing or harvesting of the rice fields, offerings were typically made to the spirit that was believed to be the owner of the land. Dominican missionaries working in Laguna de Bay in the 1680s reported that these feasts could last for up to four days.Footnote 70 Community members contributed offerings to the feast in honour of the spirits in the form of fish, eggs, tamales, cooked rice, wine, oil, vinegar, grapes, and other types of food.Footnote 71 A large number of material objects were used during such ceremonial sacrifices. In the early 1680s, Dominican priests working in the Zambales mountains confiscated more than 3,500 objects associated with ritual sacrifices performed within Zambales homes. These objects ranged from plates, bowls, and glasses used within the ritual feasting to fans, pieces of gold, stones, palm leaves, bells, and many different types of cloth.Footnote 72 Such objects and rituals also made their way into hechicería practices. For example, when Doña Luisa de Rosa wanted to pursue an extramarital affair in 1619, the Visayan woman Francisca instructed her to make an offering of some small items of gold, silver, and coloured cloth at the base of a tree. Francisca's daughter, Juana, also performed a ceremony in Luisa's bedroom involving a piece of linen, a candle, a small knife, a mirror, some rosemary, some lavender, and some oil.Footnote 73

Hechicería practitioners also drew upon extensive botanical and medicinal knowledge that incorporated Philippine flora and fauna into their spells and charms. While numerous chroniclers commented on the extensiveness of Philippine botanical and medicinal knowledge,Footnote 74 the most detailed account comes from Fr Juan Delgado who produced a manuscript in 1751 containing hundreds of pages of information on Philippine plants and their uses, derived from indigenous sources.Footnote 75 Delgado recounts almost endless lists of plants used to cure all types of illnesses, from headaches and stomach upsets to ulcers, boils, and wounds. Missionaries like Delgado evidently experimented with this knowledge themselves. The Jesuit chronicler Fr Francisco Colín, for instance, recounts several stories in which indigenous medical knowledge proved superior to that of the Europeans, such as when the herb Manungal was used effectively to counter a widespread illness that took many Spanish lives in Manila in 1628. Colín himself was cured by the application of the Alipayon leaf to a serious leg wound. After several days of dressing and changing this herb, the wound healed and Colín was left with just a scar and a deep impression of the medicinal virtues of the local flora.Footnote 76

Not all botanical knowledge was mobilised for the purposes of healing. The Spanish feared and grudgingly respected their Philippine adversaries for their use of poisons in warfare.Footnote 77 Poisons were sourced from venomous lizards and other animals and plants and then transferred on to the tips of arrows or darts. It was said that even the smallest wound from such weapons would result in certain death. Poisons were also used outside of warfare. The anonymous author of the Boxer Codex noted that Visayans used poison as an effective form of abortion.Footnote 78 Antonio de Morga wrote of multiple different poisons that could be placed in food and drink or smoked as incense. He believed there were plants that could kill just through touch or when placed beneath someone's mattress, while other poisons took a year to work.Footnote 79 We find evidence of such practices in Inquisition records. In 1620, when the 16 year-old Anna Manuel wanted to kill her husband, a slave called Gracia gave her some sticks to grate and give to her husband to drink. She was also told to place a small piece of paper along with some sticks, hairs, and powders under his pillow. All of this gave her husband an illness that lasted a month.Footnote 80 Philippine indios also possessed detailed knowledge of antivenoms that could reverse the effects of different types of poison. Morga noted that a favourite antivenom came from consuming certain insects which were specially bred for that purpose.Footnote 81

At the same time, Spanish chroniclers demonstrate the way this knowledge blended with Philippine forms of magic. Delgado notes several plants whose purpose was specifically designed to deal with hexes, spells, or the evil effects of witches. Lubican leaves, for example, were dried and made into wreathes to be worn around the neck to ward off evil magic inflicted by witches or herbalists.Footnote 82 The Tagalogs believed hexes could be administered through mixtures or herbs or roots designed for the purposes of love magic, spells of influence, and the power of taking away or restoring someone's health.Footnote 83 Several Inquisition cases refer to herbs used to soothe another's anger.Footnote 84 For instance, in 1626, Cristóbal de la Cruz received a herb from a Pampangan indio who told him to keep it with him and whenever he saw the face of one who wanted to do him evil all the rage would leave this man.Footnote 85 The Boxer Codex notes that Tagalogs used both incantations and amulets for healing, good luck, invincibility in warfare, and protection against evil spells, poisons, or other dangers.Footnote 86

We can clearly see how these forms of botanical and medicinal knowledge were used by Asian practitioners within hechicería cases. Practitioners were able to supply ready-made herbs and poisons as well as incantations, amulets, and other types of spells to Spaniards looking for love or luck charms. One ingredient that appears repeatedly in many of these charms most accurately represents the blending of Spanish folk beliefs with Asian botanical knowledge: buyo, an addictive and mild stimulant made from the areca nut, betel leaves, and activated lime. Buyo was highly esteemed in the Philippines and had long been integrated into local customs. It was a common and often central part of ritual ceremonies and offerings to ancestor spirits and was also used as part of burial practices where the juice of the buyo was smeared on the body and placed inside the mouth so that it would enter the interior.Footnote 87

In the seventeenth century, both Spaniards and Philippine indios carried buyo everywhere they went in finely wrought silver or gold boxes.Footnote 88 Delgado noted that the indios always had it in their mouth and that most of the Europeans had picked up the habit from them.

By day and by night they are continuously chewing in the manner that cows chew straw and hay. Those who are aficionados [of buyo] say that it has many benefits to chew it; one is that the smell of the leaf hides bad breath; it alleviates toothache and maintains teeth, warms the breast and the stomach when they have colds.Footnote 89

Like other chroniclers, Delgado remained sceptical of these benefits, saying that constantly chewing buyo caused a person's mouth and saliva to be stained blood red, the mouth to become cracked and covered in sores, and the teeth to fall out. He lamented the addiction which interrupted Mass and confession, leaving missionaries no choice but to allow it to be brought into the confessional. Indeed, some missionaries serving in the provinces also became addicted to the substance.Footnote 90 Such was the consumption of buyo that in the 1630s, the colonial government introduced a monopoly on its sale—similar to that of tobacco—which Delgado estimated earned the Crown 18,000 pesos each year. He believed a shortage in the supply of buyo would be far more likely to spark a rebellion than any shortage in rice or other food.Footnote 91

Unsurprisingly then, buyo was frequently used in love charms. Buyo was considered an excellent gift and was typically brought when visiting another's house.Footnote 92 Delgado noted that ‘among the Tagalogs a very close friendship is made when one gives another the sapa, which is the buyo that has already been chewed, and these friends are called casapa.’Footnote 93 Many the hapless soldier was encouraged to offer the chewed remains of his buyo to his desired lover.Footnote 94 Men and women mixed semen, fingernails, and hairs or flakes of skin from various parts of the body with buyos in elaborate charms that sometimes involved invocations or other rituals or the smearing of the sapa on the desired lover.Footnote 95 For instance, in 1629, the soldier Luis Velasco was advised to take some hairs from the woman he desired and mix them with the residue of her chewed buyo and some civet musk and then smear this mixture on her.Footnote 96

Buyo thus mirrors the use of chocolate described by Martha Few in colonial Guatemala. While chocolate became a central part of Guatemalan life, adopted by all sectors of colonial society, Few demonstrates that it also came to be associated with female social disorder. ‘Women took advantage of their roles in food preparation to assert power over the men in their lives’, by using chocolate as a central ingredient in many forms of sexual witchcraft, or love magic.Footnote 97 Chocolate could easily be mixed with bodily fluids as well as powders and herbs, and that these were often designed to control male sexuality.Footnote 98 The gender dynamics described by Few for colonial Guatemala differ to the situation in seventeenth century Manila, where men were more likely to seek out hechicería services than women and the providers of those services were more evenly split between genders. Yet there is one clearly gendered aspect to hechicería cases in the Philippines, revolving around the role of indigenous women as well-known spiritual intermediaries.

In the pre-Hispanic Philippines, spiritual leadership was almost always provided by women. Known as catalonas in Tagalog and babaylans in the Visayas, these native priestesses were seen as conduits between the physical and the spirit world and could act as mediators with ancestors as well.Footnote 99 In the small number of cases when men fulfilled these roles, they dressed as women.Footnote 100 Inquisition records from Manila suggest that the spiritual power of such women was also recognised among the Spanish population, particularly among Spanish women. Although there was a sizeable community of men providing hechicería services in Manila, Spanish women were far more likely to seek help from other women.Footnote 101 Spanish women would seek out native priestesses to help them mediate their relationships; in turn, indigenous women found a space to establish their independence within the new frontier society. Philippine women were able to use their reputation to build a business as healers and practitioners of hechicería.Footnote 102 For example, when Doña Catalina de Guzman wanted to kill her husband, she looked for help from two native priestesses, one a local resident of Manila, and the other an elderly woman with a well-known reputation as a witch who was summoned to Manila from Malolos in Pampanga. Although both women were imprisoned and treated poorly by Doña Catalina, they were paid 15 pesos for their services, indicating that women could use their magical skills to earn a living.Footnote 103 The Ternaten María de Pedrosa earned 500 pesos for the murder of an unnamed man in 1634, which she achieved through multiple rituals using parts of his hair, clothing, excrement, and discarded bread, as well as burying and burning an egg with his figure painted on it.Footnote 104 María de Saldivar admitted paying the Visayan Francisca Gómez more than 1,000 pesos in the form of jewellery and money in return for elaborate ceremonies that she performed.Footnote 105 Indeed, Francisca appears to have made a profitable business out of hechicería services and even trained her daughter Juana in her skills, as evidenced by their combined intervention into Doña Luisa de Rosa's love life in 1619.Footnote 106

Contested frontiers of pious imperialism

Although hechicería was not considered a serious religious crime by the Inquisition, the widespread use of folk magic was of concern for religious authorities in the Philippines because it undermined religious domination within this new frontier society and impacted the conversion process within indigenous communities. In early modern Spanish society, magic and Christianity competed with one another over the same spiritual domains, creating a duality within lay practices that drew upon both sanctioned religion and unsanctioned ‘superstitious’ beliefs.Footnote 107 The Inquisition used its powers to target superstitious and magical practices as part of a larger project of supplanting these existing folk practices with sanctioned Catholic sacraments and observances. This process required a substantial cultural shift that was still under way across the empire in the early seventeenth century, meaning that the religious beliefs and customs of the Spanish community of Manila were far less homogeneous than often represented.Footnote 108 Many of those accused of hechicería in Manila confessed that they were unaware that these practices were wrong in the eyes of the Church until they were told by their confessor.Footnote 109

The aims of the Catholic Church among Spanish lay communities paralleled missionary efforts within indigenous communities. Daniel T. Reff has argued that missionaries approached the conversion of New World communities with methods that had been developed by monks and bishops over many centuries in medieval Europe, transforming local spiritual landscapes by replacing pagan symbols, beliefs, and rituals with Christian ones.Footnote 110 In New Spain, this process involved the dramatic and often violent destruction of indigenous sacred sites and idols. In the Philippines, the Dominican missionary Fr Juan Ibáñez took a similar approach in the town of Santo Tomás, symbolically exorcising caves that were frequently used for indigenous ceremonies, erecting crosses outside their entrances.Footnote 111 Nevertheless, most Philippine religious practices were grounded in everyday routines and took place within domestic environments, meaning that missionaries more often approached this cultural colonisation through the confiscation and destruction of objects associated with ritual ceremonies.Footnote 112 For example, Fr Ibáñez accompanied his exorcisms with a series of household searches where he seized food and other items intended for ceremonies and threw them in the river.Footnote 113 Similarly, Jesuit missionaries operating in Leyte in 1601 built a pyre out of indigenous religious artefacts, setting fire to them to prove that these objects no longer held sacred power.Footnote 114

The existence of hechicería within the colonial environment undermined these efforts since it demonstrated a plurality of beliefs among the colonial classes. It was therefore subversive of colonial control and generated a number of investigations by the Inquisition and religious orders into the relationship between indigenous beliefs and the presence of magic and witchcraft in the archipelago.Footnote 115 These investigations were prompted initially by emerging evidence that Spanish women in particular were using indigenous ceremonies known as maganitos as powerful symbolic acts of folk magic. Such practices went beyond the ‘ordinary’ categories of superstition to which the Inquisition was accustomed, demonstrating the extent of cultural mestizaje occurring within this unsanctioned realm.

Two notorious cases of Spanish women engaging in indigenous rituals took place in 1611. In Cebu, the mestiza Doña Francisca Carreño organised a maganito involving a plate and an egg when her daughter fell ill. Performed by an elderly Ambonese slave called Saloma and witnessed by many Moluccan and Visayan indios, this ceremony was intended to foresee whether the child would recover from her illness.Footnote 116 A far more dramatic series of maganitos were performed in Manila when the noblewoman Doña María de Saldivar decided that she wanted to kill her lover's wife. Doña María was embroiled in a well-known affair with the secretary Pedro Hurtado de Esquivel, who she hoped to marry. After her own husband died—allegedly through poisoning by Doña María's own hand—she sought out the help of some Visayans to perform a series of maganitos with the objective of securing the untimely death of her rival, Doña Magdalena. The maganitos lasted many weeks and were performed on the beach and within Doña María's own house by Francisca Gomez, Pedro Macao, and his wife Catalina Limoan. During these ceremonies, the Visayans killed chickens and made offerings of crabs and cooked rice. They danced and sang and hit the wall of the house to signify that Doña Magdalena was to die. Doña María put on a perfume that was supposed to draw the soul of Doña Magdalena so that she might be killed with a sword or dagger. All of this had no effect on Doña Magdalena. Quite the contrary. The Visayan Pedro Macao noted wryly that following the maganito, the secretary Pedro Hurtado de Esquivel died instead of his wife.Footnote 117

Such an affair, conducted by someone so integrated into the heart of Manila's Spanish elite, naturally troubled the religious orders in the city. The three Visayans engaged in Doña María's maganitos were brought before the Inquisition several years later to furnish more details about their activities and to testify as to whether they had consorted with the devil. All three Visayans said they did not know if the devil had come or not but they had been forced to perform these ceremonies by Doña María.Footnote 118 The appearance of the devil within these testimonies replaces the indigenous term ‘divata’, meaning spirit, and reflects a desire by the religious orders to interpret indigenous religious practices as idolatry and witchcraft. The view that indigenous religion resulted from a genuine pact with the devil was common among Spanish religious thinkers.Footnote 119 Morga wrote of maganitos as acts in which ‘the devil deceived them … with a thousand errors … appear[ing] to them in various horrible and fearful forms … so that they feared and trembled at him; and adored him.’Footnote 120 Delgado similarly argued that the extent of indigenous medicinal knowledge could only be possible because of a pact with the devil who had communicated this knowledge to native priests and priestesses during their maganitos.Footnote 121

Missionaries believed that such pacts with the devil could be undone through the careful work of religious instruction. Nevertheless, a minority of priests believed that the devil had infiltrated the Philippines to such an extent that he had built a cabal of witches who followed his commands. In 1637, the Jesuit Fr Fabricio Sersale wrote an extraordinary account of a large society of Philippine witches who had formed an international communion that extended along the winds and via the arts of the devil between the Philippines, Mexico, Madrid, and Rome.Footnote 122 In 1651, the Dominican Fr Teodoro de la Madre de Dios similarly argued that there were so many witches, sorcerers, and evil-doers in the islands that there was not a single town free of them. He believed that the explicit pacts these women made with the devil led them to shun Christian beliefs and practices, such as attending communion or confession.Footnote 123

Bertrand argues that such beliefs impelled the subjugation of native priestesses, who were seen as one of the leading forces preventing the religious conversion of indigenous communities.Footnote 124 This came to a head in 1638, when a Javanese woman called Lucía was burned at the stake in Cebu. She was accused of leading a procession of a hundred witches—all Philippine indios, apart from herself—and of organising ceremonies where they smeared their naked bodies with coconut oil, danced and sang while eating human flesh, flew through the air, and summoned devils in the form of carabaos and serpents.Footnote 125 This case is extraordinary as the only known example of witch burning in Philippine history.Footnote 126 At the same time, the use of maganitos by Spanish women also suggests that while missionaries and inquisitors sought to repress the power of native priestesses, the same power attracted the attention and respect of the lay community. Missionaries wanted these practices stamped out, but often did not get the necessary support from secular authorities to do so. Both Sersale and Madre de Dios reported very limited interest by the secular authorities in matters of indigenous witchcraft.Footnote 127

This lack of support may have been more pragmatic than anything else. The burning at the stake of the Javanese woman Lucía was an example of the widespread frontier violence that accompanied Christian conversion and took place within a context of decades of rebellion by many Visayan communities against the evangelising activities of Spanish missionaries. Within these rebellions, Visayans typically took to the mountains, fortifying themselves in hill forts and re-establishing their own forms of religious practice. With limited military resources at their disposal, Spanish authorities often failed to adequately respond to this resistance to evangelisation. The records of these rebellions are unsurprisingly charged with spiritual symbolism.Footnote 128 For example, a major rebellion in 1621 on the island of Bohol was led by four babaylans (native priests) who instructed their followers to burn down their villages and churches and desecrate any Christian religious items that they could find. The babaylans believed that they were protected by a divata (ancestor spirit) who would cause the mountains to shake and the bullets of the Spanish muskets to misfire.Footnote 129 In Panay in 1663, an indigenous priest named Tapar led another rebellion, subverting Christian symbolism by appointing those among his followers as the Son, the Holy Ghost, the Virgin Mary, apostles, popes, and bishops.Footnote 130

Such acts were not restricted to the Visayas. Across the archipelago, indigenous communities turned the symbolic desecration of religious symbols against Christian missionaries. Caragan rebels in 1631 laid siege to the church and convent in the town of Tandag. They sacked the buildings and desecrated religious artefacts, smashing crucifixes and taking an axe to the statues of Christ, before killing four Recollect priests. Following these destructive acts, the rebels held a mock Mass, with an india called Maria Campan dressing herself in the priest's robes, throwing holy water around the church and declaring ‘I am Father Jacinto.’Footnote 131 In 1621, Irrayan rebels in the province of Cagayan similarly adopted the garb of local priests and thrust a knife into the face of a statue of the Virgin Mary to see if she would bleed.Footnote 132 Further north, Isneg rebels descended from the Apayao mountains during a major rebellion in 1661 and laid waste to the Dominican church in Pata, smashing all the statues of the Virgin Mary and of Christ.Footnote 133

The project of ‘pious imperialism’ was evidently contested by communities across the archipelago. On a more mundane level, the pluralism of Spanish beliefs as evidenced through folk magic practices helped to foster an ambivalence among some neophyte communities towards Catholicism. Outside times of rebellion, indigenous communities simply hid their activities from the missionaries, choosing locations outside of towns to continue to conduct their own religious customs. Many missionaries wrote that indigenous communities often moved further away from evangelising priests—settling into remote farmlands or retreating into the mountains;Footnote 134 those who remained often left their faith at the church door.Footnote 135 Within the fragile frontier environment of Manila, the inconstancy of indigenous converts was compounded by the largely non-Christian Chinese community. Fr Angulo wrote that the pagan Chinese frequently ‘introduce[d] among the indios … their customs and pagan rites, their little esteem for the laws of God, or respect for those of the Church, their idolatries, their deceits, weaknesses, drunkenness’, all of which was opposed to what the indios learned from the evangelical ministers.Footnote 136

These factors emphasised the frontier nature of Manila in the early seventeenth century. Despite the many assertions by church historians that the evangelisation of the Philippines was completed by the end of the seventeenth century,Footnote 137 historical anthropologists have typically emphasised the incompleteness of religious conversion among Philippine communities.Footnote 138 This is evidenced by the continuation of many pre-Hispanic religious practices and their adoption and adaptation within Filipino folk Catholicism. Such continuity is seen particularly in magical practices relating to the role of sorcerers and healers within Philippine communities. In many parts of the archipelago, indigenous traditions involving the invocation of spirits—for instance, at harvest time or in times of illness—remain important parts of local culture. The anthropologist Fenella Cannell argues that both these practices and the way that they are viewed by Philippine communities have been shaped by the lengthy history of contact with Catholic missionaries. Although communities continue to look to spirits for guidance and healing through the mediation of modern-day shamans, these practices are often interpreted by those who engage with them as a type of devil-worship and therefore typically take place clandestinely.Footnote 139

When considering the evolution of such cultural practices, anthropologists have typically focused on the role of missionaries in attempting to either stamp out indigenous ‘idolatry’—thus forcing these practices underground—or on their ability to translate Christian concepts into indigenous cultural practices. What is missing here is an assessment of the role of Spanish forms of folk magic, as practised by lay communities, and its interaction with indigenous cultural traditions. As this article has demonstrated, hechicería became a frontier for bridging a gap between settler and indigenous cultural beliefs in an unseen spirit world that was able to mediate relationships and divine the fortunes of those who practised this form of folk magic. The folk magic that we find in early modern Manila mirrors similar practices found across the empire in this same period. Men and women looked towards magical interventions to help them in matters of love, health, and fortune; and they did so despite the censuring of these activities by the church and Inquisition. A diverse group of Asian men and women were essential in facilitating access to this magic. Spaniards looked towards Philippine healers and herbalists, native priestesses, and Ternaten nobles. In doing so, they recognised the skills of these practitioners as healers, herbalists, and spiritual guides, while also acknowledging the need for specialist, local knowledge that allowed the Spanish community access to a local landscape of magic and medicine. Although we can identify many commonalities in this story with other parts of the empire—especially in the ways hechicería practitioners challenged gender and racial hierarchies—it was the actions of these Asian practitioners that lends hechicería in the Philippines its own unique flavour. These practitioners facilitated the coming together of folk traditions of magic that created a cultural mestizaje unique to this space.

Folk magic thus allows us a new way of viewing colonial Manila. This is not merely because we learn, in perhaps unprecedented detail, of the personal lives of its residents and their love affairs, rivalries, conquests and betrayals. These stories also demonstrate the porous and permeable nature of colonial culture and the ways both indigenous and European lay communities challenged the dominance of ‘pious imperialism’ on the frontier. The dogmatic image gleaned from Spanish missionary chronicles of a pious people intent on the conquest, conversion, and civilising of heathen peoples becomes less assured. Spaniards themselves engaged in their own forms of unsanctioned folk religion which was remarkably receptive and adaptive of local traditions.