The fact that financial markets went markedly into shock has to be attributed to a lack of confidence in policies and leadership. It’s a failure of worldview.

I found out to my intense surprise and disappointment that my father did not have, what I then thought was a basic necessity for any real person – a “Weltanschauung”! The subsequent history of my life and thought could probably be written in terms of the progressive discovery on my part how right my father had been.

Sometimes we get overwhelmed by the uncertainties of life and the open-endedness of the future. The pandemic gripping the world in 2020/21 is one such instance. As the virus spread, a sense of personal vulnerability and radical uncertainty spread as well, barely masked by incessant talk about changing risk calculations.Footnote 3 In such moments many of us do not turn to theories, models, or hypotheses. Instead, we turn to worldviews to give us some traction in a world suddenly turned upside down. President Trump’s worldview valued national borders that could be closed to foreigners. Early on, he imposed a ban on travel from China. The World Health Organization and many others were aghast. Their worldview valued open borders and unobstructed travel. In January 2021, during his last day in office, President Trump lifted travel bans his administration had previously imposed, only to have the incoming Biden administration immediately reverse his decision. This is not to deny the obvious. After four years in office, President Trump’s general worldview had affected state and local officials of the Republican party, not to mention tens of millions of his supporters.Footnote 4

The 2020/21 pandemic is merely the latest example of the kinds of uncertainties students of world politics confront on a daily basis.Footnote 5 On March 3–4, 2020, for example, it was unclear how the stock market would react to the biggest emergency rate cut of the Federal Reserve since the Great Recession of 2008. Most market analysts expected a bounce in stock prices; instead, the market tanked. A few weeks later – again to everyone’s total surprise, as the real economy cratered and the number of unemployed topped 30 million – April 2020 turned out to be the best month Wall Street had recorded since 1987. Politics is similarly unpredictable. For example, the outcome of the Super Tuesday Democratic primary of March 2020 was entirely uncertain. Nobody had a clue how it would affect the relative standing of the main contenders. In the event, Joe Biden’s string of victories stunned analysts and practitioners alike. Shomik Dutta, a veteran of Obama campaigns, lamented: “It’s a bizarre feeling to realize that all the things I obsess over in politics … did not seem to matter very much at all.”Footnote 6 Eight months later, most pollsters agreed that Joe Biden would win the 2020 US Presidential election comfortably, and perhaps with a blow-out. Pollsters had tweaked their models, learning from their 2016 mistakes. All the hard work was to no avail. The cliff-hanger election disproved a tsunami of surveys.Footnote 7

With its unexpected turns and twists, time and again world politics has stumped participants and analysts with momentous events. The end of the Cold War, German unification, the peaceful disintegration of the Soviet Union, the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, the 2008 financial crisis and its aftermath, the Arab Spring, Brexit and the election of Donald Trump, the surge of protest across the United States after the murder of George Floyd, the coronavirus pandemic, and the wildfires engulfing the American West coast in 2020 were all big surprises. Insider knowledge and the political intuition of central protagonists are of little help. Chancellor Kohl’s 1989 predictions about the process of German unification were wrong, as were those of Prime Minister Cameron in 2016 about the outcome of the Brexit referendum. And so too were the well-considered judgments of leading American international relations theorists. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Kenneth Waltz bet that the Soviet Union would last another century, Robert Keohane that the era of American hegemony had passed.Footnote 8 When the unexpected undermines or overturns our most respected theories, we often fall back on our worldviews for guidance.

For Theodore White, “It is the nature of politics that men must always act on the basis of uncertain facts … Were it otherwise, then … politics would be an exact science in which our purposes and destiny could be left to great impersonal computers.”Footnote 9 Putting aside the concept of uncertainty, most students of world politics have followed economics in focusing their attention on calculable risk.Footnote 10 For example, in her authoritative and sophisticated analysis of risk and uncertainty in international politics, Rose McDermott writes that risk and uncertainty comingle.Footnote 11 She thus combines both as she identifies mechanisms of risk propensity that occur under conditions of “high” uncertainty. In the remainder of her book, however, she puts aside the problem of uncertainty and focuses exclusively on the domain of risk.

While it is not possible to scale the magnitude of uncertainty, it is possible to distinguish between two types: operational uncertainty and radical uncertainty. Known unknowns create operational uncertainty which, given more or better information, may transform into calculable risk. This, however, is not a panacea. Under conditions of operational uncertainty, better and more information and knowledge, as in the squeezing of a balloon, can simply push radical uncertainty into some other, unrecognized part of the political context.Footnote 12 On questions of security and political economy, this is standard practice in the analysis of world politics.Footnote 13 Uncertainty is conflated with the concept of risk and thus remains invisible.Footnote 14 McDermott acknowledges this fact. “It is impossible,” she writes, “to predict the characteristics of many different variables simultaneously in advance, especially when they may have unknown interaction effects. Even the nature of many of the critical variables may be unknown beforehand.”Footnote 15 Analysis proceeds based on the unrealistic assumption that, separated by different information, parties to a conflict in world politics share in the same understanding of how the world works. New information leads to revised risk calculations and thus offers a way forward.

Withdrawn from the precarious domain of uncertainty, the future is domesticated into the more agreeable form of risk, thus retaining a family resemblance with the present and the past. Measurable confidence intervals strip the future of the deep anxiety that attends the unknown. We live life forward while understanding it backward. The malleability of the world is reflected in the multiple ways we have convinced ourselves of knowing the future. Prediction becomes a specific technology of “future making and world crafting,” made possible by severing the link between a man-made future and religion.Footnote 16 This offers us an avenue for managing expectations and thus to exercise some control over time. But such efforts can run up against manifestations of uncertainty such as technological breakthroughs, authority crises, consensus breakdowns, revolutionary upheavals, generational conflicts, and other forces that restructure the political landscape.Footnote 17 Theories and models are thus defeated by the unpredictable as world politics moves beyond control.Footnote 18 And, as Ernst Haas observed long ago, theories and models can unwittingly exacerbate problems of turbulence by pretending to create predictability for parts of political reality while weakening our understanding of the whole.Footnote 19

Worldviews differ in the salience they assign to risk and uncertainty. Approaches such as subjective probability theory explore ways of thinking about rationality and its relation to risk and uncertainty.Footnote 20 Rationality can take the form of different, situationally specific kinds of reasonableness. Since total chaos and existential uncertainty are terrifying, concepts such as ontological security probe different forms of reasonableness under conditions of risk and uncertainty.Footnote 21 And reasonableness differs in worldviews populated by different cosmologies, memories, imaginaries, emotions, and moral sensibilities: “It is not the information but the worldview that drives actors.”Footnote 22

The concept of a risk-inflected control of nature and society is so reassuring that we simply close our eyes to the self-evident: the ineluctability of the uncertainties of life. Why we do so is not self-evident. To be sure, the idea of risk is profound and has been immensely beneficial in human affairs. Indeed, a couple of centuries ago it was revolutionary to think that the future could serve the present, and that the chance of loss is an opportunity for gain.Footnote 23 But these important insights should not make us deny the obvious: uncertainty and an open future are important aspects of world politics. Uncertainty results in part from people holding different theories of how the world works. The financial meltdown of 2008 showed widely accepted risk models to have been utterly useless in predicting the crisis. Very little has changed either in the specific field of finance or in the broader analysis of world politics. We have been so fully seduced by the Hobbesian notion of control that we overlook the surprises Machiavelli writes about. We have placed all of our bets on the all-controlling Leviathan, while forgetting about the jolts fortuna administers regularly.Footnote 24

This is not to argue that uncertainty is the only factor shaping political life. Social science and common sense offer tools that equip us to cope with “knowable unknowns” and the risky aspects of life in a partly orderly world.Footnote 25 However, “unknowable unknowns” also exist, and these radical uncertainties shape a reality not amenable to risk analysis. Compared to the Great Recession of 2008, the 2020 pandemic raised broader uncertainties, thereby linking challenges in public health to escalating individual and social fears, and to collapsing economies. And this global pandemic is mild compared to the dramatic environmental changes that may well be unfolding under conditions of global warming. That crisis, Scott Hamilton writes, may pose “an unprecedented existential and temporal uncertainty concerning the future of human subjectivity, and of the Earth itself.”Footnote 26

The first typical reaction to our encounters with uncertainty is bafflement at the unexpected, and subsequently a labored process of normalizing the abnormal, followed by amnesia. Metaphors help. Echoing George Kennan’s insistence that we are gardeners, not mechanics, former Secretary of State George Shultz once remarked that “diplomacy is like gardening. The layout of the garden is set. It just has to be tended.”Footnote 27 But times have changed. For many students of politics, today’s world looks and feels like a jungle. Robert Kagan, a prominent neoconservative public intellectual, captures this mood in the title of his book, The Jungle Grows Back.Footnote 28 He explains that liberalism “took root, spread and evolved” in an order that “was always artificial and tenuous, challenged from within and without” by the natural forces of an anarchic geopolitics. “Like a garden, it can last only so long as it is tended and protected. Today, the US seems bent on relinquishing its duties in pushing back the jungle.”Footnote 29 Susan Rice, who served as National Security Advisor under President Obama, concurs when she speaks of “Trump’s Hobbesian jungle.”Footnote 30 And an unflappable, rational former physicist, Germany’s Chancellor Merkel, watches as the liberal multilateral world she helped sustain is “shoved aside by the law of the jungle.”Footnote 31 Like Germany, Canada too must learn how to navigate a “jungle-like world.”Footnote 32 Today, the jungle has become a common metaphor for the many disruptions and weirdnesses of the unpredictable.Footnote 33 Jungle and garden metaphors are stand-ins for worldviews that often remain unspoken while helping us navigate the turbulent currents of world affairs.

We should be wary, though, of loading the dice only on the side of looming threats. Jungles and forests are not only places of dread but also sites of hope. Uncertainty can reveal vulnerabilities that lead to creative responses and empowerment of the disempowered. Such bigger issues could be environmental or social. Viewed in a broader context, Jared Diamond argues, a “successful resolution of the pandemic crisis may motivate us to deal with … bigger issues that we have until now balked at confronting.”Footnote 34 Aided by the shocking vulnerabilities of African Americans revealed once again by the pandemic, the explosion of the Black Lives Matter movement in America in the summer of 2020 created a powerful multiracial coalition that vented its fury at police violence as one among many instances of systemic racism. This was the latest installment of a rights revolution that has spread globally during the last half-century, in fits and starts to be sure, and often in unpredictable directions.

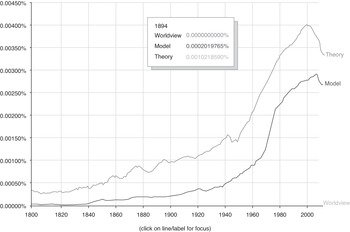

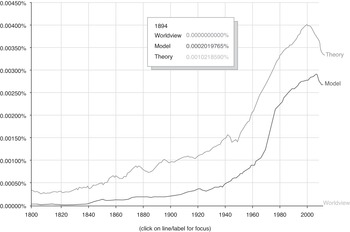

Although they provide important anchors at many moments of uncertainty, the lack of attention to worldviews in the analysis of world politics is striking. Measured by Google Books Ngram Viewer, in sharp contrast to the concepts of “theory” and “model,” Figure 1.1 shows that the concept of “worldview” is barely used.Footnote 35 Two decades ago, Peter Haas popularized the concept of epistemic communities, writing in the most cited article of International Organization, the highest-ranked journal of world politics in the United States, that epistemic communities refer to networks of knowledge-based individuals “who share the same worldview.”Footnote 36 While many scholars have followed his lead in developing the concept of epistemic community, none, to my knowledge, has followed up to inquire into the concept of worldview. While we might be vaguely aware of uncertainty’s role in global politics, we seem to prefer not to look this challenge in the face by examining our worldviews.

Figure 1.1 Ngrams: worldview, theory, model

In conceiving and contributing to this book, I have ventured for a third time off the conventional garden path of international relations scholarship. As was true of all other scholars of world politics, the end of the Cold War caught me by surprise. I wanted to understand why and turned to cultural sociology for new insights. The Culture of National Security,Footnote 37 mainstream realists and liberals thought in the mid-1990s, was no more than a futile exercise in postmodern flim-flam that had nothing to do with respectable social science. It turned out, however, that cultural sociology was central to the constructivist theories of international relations that quickly secured for themselves seats at the high table of theory. Seeking to understand the Great Recession of 2008–09 two decades later, I tracked the broader political implications of uncertainty and developed a conceptualization of power that was less materialist and less focused on Hobbesian notions of control. Film and cultural studies provided me with valuable insights into the dynamics of unpredictable possibilities and potentialities of what Lucia Seybert and I called Protean Power.Footnote 38 The evident difficulty that book’s argument created for many of my colleagues, as it forced them to come to terms with uncertainty and potentiality, has led me in this book to turn to the natural sciences, which for more than a century have been no strangers to these two concepts. Uncertainty and Its Discontents seeks to show the deep Newtonian roots of the firm convictions of what a scientific study of world politics entails, and our never-ending amazement when the unexpected derails those scientific endeavors. I will argue that “the relational revolution” in twentieth-century physics, and many of the natural sciences more generally, can enrich sociological relationalism in the social sciences.Footnote 39 It embeds risk-based, Newtonian thinking about a “world of being” in an uncertainty-inflected, Post-Newtonian thinking about a “relational world of becoming.” Thus, it explicitly acknowledges uncertainty and the open-ended potentialities of world politics.

This chapter seeks to better understand the scientific worldviews that make us overlook uncertainty as a central aspect of world politics. It examines the concept of worldview (Section 1.1); considers for the field of world politics the substantive and analytical formulations of worldviews in the form of political and analytical paradigms, as well as substantialist and relational ontologies and epistemologies that are embedded in them (Section 1.2); differentiates between Newtonianism and Post-Newtonianism (quantum mechanics) and humanism and hyper-humanism (scientific cosmology) as two dimensions structuring different worldviews (Sections 1.3 and 1.4); exemplifies the resulting four worldviews as presented in greater detail in Chapters 2–5 (Section 1.5); and concludes briefly with two illustrations (Section 1.6).

This chapter’s presentation of four strikingly different worldviews is balanced in Chapter 10 by a discussion of some workarounds and commonalities that provide a shared intellectual space for Newtonianism and Post-Newtonianism. Newtonianism prefers sharp distinctions. Philosophically, Post-Newtonianism does not. Chapter 10 thus adheres to Samuel Beckett’s admiration of “greyness.”Footnote 40 Moving from clearly demarcated “either–or” conceptual spaces in Chapter 1 to entangled “both–and” spaces in Chapter 10 suggests a radical reconceptualization of conventional understandings of science operating at both macro- and microlevels. Specific approaches in the field of scientific cosmology and quantum mechanics put the individual human experience rather than objective laws of nature at the center of the universe. This eliminates the traditional insistence on the difference between the natural and social sciences and holds forth the promise for the analysis of uncertainty and risk, rather than the insistence that world politics is marked simply by risk.

1.1 Worldviews

Worldviews offer global overviews evident in relatively constant, repetitive habits of beliefs and emotions that mediate the relations between an individual or group and the world.Footnote 41 They are animated by a sense of being in the world and of viewing how the world works or should work. Worldviews are neither purely descriptive nor purely explanatory. They contain both prescriptive and practical elements. Far from immutable, they are susceptible to fluctuations brought about by personal experience and change in the world. They comprise a flexible conceptual apparatus rooted in values. Relationally mediated by discourses and institutions, worldviews create narratives about what is possible, what is worth doing, and what needs to be done, as well as what is impossible, what is shameful, and what needs to be avoided. They thus have effects on the purposes and interests that shape policies and practices. Many techniques and rules, on their own terms, might be considered inadequate or too weak to justify policy and practice, yet they acquire a deeper legitimacy when embedded in a broader worldview. What Daston writes about natural orders is also apposite for worldviews: they are “long-lived, polyvalent, and evocative of powerful emotions.”Footnote 42 Operating at different levels of abstraction, several authors in this book point to a close relationship between worldviews and other, commonly used concepts. For example, in Chapter 5, Michael Barnett disaggregates holistic worldviews and points to the internal contradictions of their different components; and in Chapter 8 Bentley Allan considers worldviews built from more encompassing cosmologies.

Worldviews are concerned with viewing the world and understanding one’s place in it. They are suffused with epistemologies and ontologies. But in the discipline of international relations, in the words of John Ruggie, “epistemology is often confused with method, and the term ‘ontology’ typically draws either blank stares or bemused smiles.”Footnote 43 Today, almost without fail, social theories “posit an ontological beginning point … that one takes to be the foundations of the (world-) view being explored or posited.”Footnote 44 As epistemologies, worldviews concern the scientific or religious basis for knowing the world. Worldviews can be analytic or substantive. Paradigms, theories, models, and the explanatory constructs they deploy are analytic. Liberalism, Realism, and Marxism are substantive. Worldviews provide elastic interpretive guides to help navigate the world. They differ from both universal, trans-historical cosmologies and more specific, time-bound ideologies. The concept of worldview is contested and, for some, considered inherently contestable.Footnote 45 The chapters in this book provide ample material for both contestation and inherent contestability.

Because they are foundational, worldviews are important for understanding and evaluating human choice. Embodied in both views and practice, they both passively “re-flect” and actively “re-present” the world, offering views both of and for the world.Footnote 46 Because “we believe what we do largely because of the way our beliefs fit into our worldview,”Footnote 47 our diagnoses and solutions are not cheap talk. Worldviews consist of big yet simple ideas that operate at both individual and collective levels. They reflect and shape individual ideas, experiences, memories, and imaginations that always remain open to modifications and reinterpretations.Footnote 48 They are also collective systems of thought that offer some measure of coherence and consistency in an often unfathomable world.Footnote 49 Worldviews can incorporate contradictory and tension-inducing elements. Loosely coupled, they compete, coexist, and coevolve with one another.

The growing schisms dividing “metro” from “retro” have prompted a few observers to apply the concept of worldview to contemporary American politics.Footnote 50 Reflecting on the partisanship of the 1990s and early 2000s, cognitive scientist George Lakoff writes that “contemporary American politics is about worldview.”Footnote 51 Conservatives and Liberals have a very difficult time understanding each other because they rely on different commonsense notions as they interpret what they experience. Conservatives hold to a “Strict Father,” Liberals to a “Nurturing Parent” trope. In a similar vein, and adapting Max Weber to twentieth-century America, Eric Oliver and Thomas Wood try to capture the different intuitions and modes of reasoning that distinguish American’s disenchanted and enchanted worldviews.Footnote 52 Marc Hetherington and Jonathan Weiler, finally, develop a related argument that focuses on two worldviews epitomized by pick-up truck and Prius, John Wayne and Jane Fonda, meatloaf and vegetable biryani, and a preference for a fixed or fluid politics.Footnote 53 During the last half-century, operational political ideologies have increasingly lined up with such underlying worldviews and are now creating a polarized politics that is threatening the very fabric of American democracy. The notion of a unique and singular American worldview captured by the trope of American exceptionalism is mistaken. American worldviews express political inclinations and moral sensibilities that differentiate liberals from conservatives along a number of dimensions. On closer inspection, though, all of these dualities are oversimplified and fail to capture the fractal patterns of political change in America.Footnote 54 Despite such qualifications, it is difficult to deny that worldviews play a substantial role in American politics.

Individually experienced yet irreducibly social, worldviews circulate through society.Footnote 55 They have emotional and rational components that are seamlessly fused.Footnote 56 As modern neuroscience tells us, one does not exist without the other.Footnote 57 “Emotions are not irrational pushes and pulls,” Martha Nussbaum writes. “They are ways of viewing the world. They reside at the core of one’s being, the part of it with which one makes sense of the world.”Footnote 58 For Nussbaum, emotions are “appraisals or value judgements which ascribe to things and persons outside the person’s own control great importance for the person’s own flourishing.”Footnote 59 The Latin root of the word emotion means to “move out” from the individual toward others and the world. Although emotions are individual, they also have an inherently social character.Footnote 60 Their collective reality is closely linked to individual identity.Footnote 61 Emotions are an important aspect of how we view the world. This is not to deny that a worldview is also grounded in rational beliefs with little or no emotional content. Newtonian and Post-Newtonian scientific worldviews, for example, differ in their rejection or acceptance of uncertainty as a constitutive aspect of both the natural world and the political world.

Emotional and rational worldviews, Miriam Steiner has argued, can appear in a modified form that acknowledges the fuzzy boundary between optimization and intuition.Footnote 62 A modified rationalist worldview incorporates the notion of bounded rationality operating under constraints that encourages satisficing rather than optimizing behavior.Footnote 63 A modified nonrationalist worldview highlights the importance of intuition and subjective awareness. Some rationalist elements are always present in predominantly nonrationalist views, and vice versa. A comprehensive worldview integrates elements of both, featuring complex configurations of rationality and non-rationality.Footnote 64 Feelings of being in the world and being anchored in a particular worldview thus can challenge or reinforce our core beliefs. Such complementarities or contradictions can reinforce worldviews, alter them, or make them crumble.

The concept of worldview operates at a higher level than several related concepts that scholars of world politics have deployed in their analyses of world politics.Footnote 65 Foreign policy ideologies, belief systems, strategic cultures, operational codes, causal beliefs, cognitive maps, narratives, and policy and political paradigms are all related to, though distinct from, overarching worldviews. For example, worldviews are less coherent than Mark Haas’s foreign policy ideologies.Footnote 66 They are conceptually less clear than Ole Holsti’s belief systems, Alastair Iain Johnson’s strategic cultures, and Nathan Leites’s operational codes.Footnote 67 They are broader than the causal beliefs that interest Jeffrey Legro and the cognitive maps Robert Axelrod has deployed, and less determinative than the narratives that concern Ron Krebs.Footnote 68 They are less cognitive, less influenced by academic and bureaucratic experts, and socially and culturally more deeply embedded than are policy paradigms.Footnote 69 And they are overtly less political than political paradigms.Footnote 70

Worldviews can act as both stabilizing anchors and emergent processes. They can be both explicit and implicit. The very idea of a choice of worldview is itself the product of a specific worldview. In fact, some strands of neuroscience suggest the possibility that reason and consciousness set in only after – rather than before – the act of choosing has occurred.Footnote 71 Worldviews shape the views of both scholars and of the various actors they study. Worldviews connect the interpretation of the self in the analysis of the other and the world. In this chapter, for example, I am particularly interested in the scientific worldviews of scholars and the effect they have on the neglect or recognition of the constitutive importance of uncertainty in world politics. By contrast, in Chapter 2 Mark Haas and Henry Nau examine the worldviews of political leaders and the effects these worldviews have on political norms and practices. In Chapter 7, Prasenjit Duara covers the worldviews of both scholars and leaders.

These general characteristics of worldviews find more specific expression in the difference between the Newtonian and Post-Newtonian scientific worldviews that concern me here.Footnote 72 In the analysis of world politics and the social sciences, Newtonianism has been hegemonic. In contrast, quantum mechanics, with its insistence on the centrality of uncertainty at the subatomic level, has occupied a marginal position in the social sciences – including the study of world politics.Footnote 73 Furthermore, the relational revolution in scientific cosmology and several other branches of the natural sciences puts the concept of uncertainty into a much broader context. Both quantum mechanics and scientific cosmology are instances of a Post-Newtonian scientific worldview with far-reaching ramifications for our understanding of society and history. Yet, students of world politics have shown little interest in exploring and learning from Post-Newtonianism.

Newtonian uncertainty is cast in agentic terms and is believed to be manageable through the exercise of control power and risk management. In Post-Newtonianism it is considered systemic and can include protean power effects that thrive in the domain of the unexpected.Footnote 74 In the analysis of world politics, scholars with a Newtonian worldview typically downplay or overlook the distributed agency that is highlighted by Post-Newtonianism. Newtonianism offers a commitment to intervening in the world by accountable agents who seek to achieve some purpose or value. Post-Newtonianism is less focused on individual accountability. It points instead to the inherent contradiction within a Newtonian worldview, with its firm belief in laws or causal mechanisms that deny or limit freedom and agency while at the same time insisting on the primacy of agency and accountability. Although Newtonianism reigns supreme in the analysis of world politics and some of the other social sciences, it has been sidelined in physics and the natural sciences. Debates in quantum mechanics, for example, do not seek to attack or defend Newtonianism in general; they focus instead on which elements of a closed Newtonian system can be usefully incorporated in a broader view of a universe that is open.

The determinism and certainty of Newton’s macro world, softened by the laws of probability, has been replaced by the indeterminism and uncertainty of the micro world of quantum physics. According to Feynman, Mermin, and Baeyer, Newtonian and quantum physics are examples of scientific worldviews.Footnote 75 Taken together, these two scientific worldviews illuminate a politics marked by risk and uncertainty. In the Newtonian worldview, “the future after a fashion repeats the past.”Footnote 76 Novelty in Newtonianism is conceived of as recombinatorial, in contrast to the possibility of radical creativity and innovation in Post-Newtonianism. In the conventional understanding of world politics, the world is viewed as closed and inhabited by actors who feel threatened by uncontrollable uncertainty. Envisaging a world that is open and actors who are enabled by new possibilities seems implausible and uncomfortable.

Only a handful of scholars of world politics have explicitly introduced the concept of worldview into their analysis. For Patrick James, building on Rosenau, worldviews provide complex, holistic foundations for scientific research. They are not analytically consistent.Footnote 77 They subsume paradigms, theories, models, and hypotheses that seek to understand and explain patterned or specific events. Worldviews are inescapably normative and shape the understanding and explanation of reality. They are often self-confirming and sometimes self-invalidating. Divergent worldviews do not get resolved by appeals to logic and evidence but through individual experiences and social processes.Footnote 78 In contrast to James, worldviews for Jürg Gabriel are extremely simple and highlight a few concepts that for centuries have remained largely unchanged.Footnote 79 He identifies optimists among scholars who believe in a general accumulation of knowledge, and pessimists who are frustrated by the fact that, beyond a handful of small islands, accumulation is smothered by a proliferation of often incommensurable approaches. In contrast to the cumulative process of knowledge creation in the natural sciences, knowledge creation in international relations is repetitive. Time and again, students of world politics deal with foundational issues and concepts in light of new circumstances and information.

The stabilization of an uncertain world through worldviews is a political act.Footnote 80 Worldviews offer basic ideas that shape the questions we ask or fail to ask, provide us with explanatory and interpretive concepts, and suggest hunches or plausible answers.Footnote 81 They are a handle that organizes many of the world’s unknown or poorly understood facts. For Max Weber, a world image (Weltbild) or worldview consists of concepts and judgments that can provide the groundwork for a thoughtful ordering of the world and a narrative shaping of “salient areas of daily, human practice.”Footnote 82 But, contra Weber, worldviews operate in all societies and in all historical times.Footnote 83 They are imaginaries that are built around basic and often unarticulated assumptions such as “time, space, language and embodiment.”Footnote 84 Worldviews contain arguments about the ontological building blocks of the world, the epistemic requirements of acceptable knowledge claims, and the origin and destiny of humanity. They find expression in institutional and symbolic orders. They are legitimated by being part of the natural order of things, privilege some actors, such as priests or scientists, and embody shared values that are considered “natural.” Within a given worldview there can always exist a variety of different and often competing ways of understanding. Christianity’s religious wars are one example. Scientific schisms between Aristotelian and modern science and within modern science, between classical physics and quantum mechanics, are another. Lacking tight internal integration, worldviews infuse meaning into world politics. Inchoate as they often are, worldviews are central to our readiness to accept uncertainty as a constitutive aspect of world politics.

1.2 Paradigms, Substantialism, and Relationalism

In their discussions of worldviews, students of world politics have tended to collapse this concept’s multifarious analytical and political components into the more mundane “paradigm.” Footnote 85 Specifically, since the 1970s they have debated both Thomas Kuhn’s work on analytical paradigms and substantive political paradigms such as liberalism, realism, and Marxism. Commitments to Newtonian substantialism and Post-Newtonian relationalism, and the attendant (in)ability to conceptualize uncertainty as a constitutive part of world politics, are embedded in discussions about both types of paradigm.

Paradigms. Historian of science Thomas Kuhn used the concept of paradigm to characterize and distinguish the foundational assumptions of different scientific approaches.Footnote 86 Scientific progress was not a story of continuous and cumulative progress. It consisted instead of periods of normal science interrupted by brief periods of revolutionary science. Normal science is marked by the ascendance of a single paradigm that determines the central research questions, theoretical vocabulary, and acceptable methods and criteria for assessing how well a given question has been answered. When fully institutionalized, weak links of dominant paradigms are no longer recognized, foundational assumptions are no longer questioned, and anomalies are consistently overlooked or considered as lying outside of acceptable research programs. Revolutionary science occurs in brief spurts when scientists are frustrated by increasing numbers of anomalies, interested in new research questions, and committed to developing new approaches that might resolve troubling anomalies. Once the insurgents have acquired sufficient clout, conditions are ripe for the emergence of a new paradigm. Controversially, for Kuhn, paradigms are incommensurable with one another, so it is impossible to integrate or compare theories developed within different paradigms.

Kuhn’s argument about “paradigm shift” and “paradigm incommensurability” is analytical.Footnote 87 It tells us nothing about the world itself. His argument is about the perception of reality and not about the real world. In a Gestalt-flip paradigm shift, we do not necessarily lose the ability to see the rabbit or the duck, but we may not be able to see them at the same time. The argument about incommensurability that captured the imagination of the humanities and some of the social sciences resonates with shifts in the “soft” parts of paradigms. It fails, however, to capture their “hard” parts that deal with predictive accuracy, explanatory depth, and power. The incommensurability account mischaracterizes the process of inquiry in the modern natural sciences, specifically in the maturing of paradigms and their theoretical developments over time.Footnote 88 Difficulties of understanding across paradigms are not the same as the impossibility of understanding. The question of “what is,” after all, is not the same as “what is known” or “what can be made meaningful.”Footnote 89 Such difficulties do not imply that all statements about truth are contingent.Footnote 90 As a matter of fact, Kuhn’s later writings reflect a modified view on incommensurability, toward a more circumscribed claim about meaning variance across paradigms and the limits of our ability to translate adequately from one paradigm to another.Footnote 91 In any case, as Gunnell observes, “philosophy is no more the basis of science than social science is the basis of society.”Footnote 92 For those who believe that there is a reality outside of and apart from the observer, it makes little sense to ask a natural or social scientist whether they have nature or society right.

Kuhn sometimes likened revolutionary, paradigm-shifting scientific progress to the process of Darwinian evolution: nondirectional improvement with no specific purpose. By contrast, change during normal times, within a well-understood paradigm, is directional.Footnote 93 There are multiple truths in all scientific endeavors and, on the record of the last several centuries, natural scientists have ruled out many things previously thought to be true. There is thus justified hope of movement in the direction of greater truth.Footnote 94 That hope is weaker in the social sciences – which Kuhn saw as lingering in a preparadigmatic stateFootnote 95 – including the analysis of global politics, especially as long as it is captured by a worldview that fails to recognize the constitutive effects of uncertainty.

Since the middle of the twentieth century, students of world politics have debated their worldviews, first by employing the terminology of images and subsequently of substantive political paradigms. Carried by the unspoken assumption that we live in a world of probabilistic laws and risk, uncertainty has not been a subject in any of those debates. In the 1950s, the debate focused on the “image” of international relations.Footnote 96 For Wright, a synthesis of different mental images defined each scholar’s perspective on international relations.Footnote 97 The world thus generates a uniform picture that lines up with the worldview accepted by individuals or groups. McClosky, Boulding, and Waltz all assumed that a stable, external world is reflected in multiple, shifting, subjective representations that scholars imagine to be images of unified, coherent wholes.Footnote 98 The image of world politics thus was embedded deeply in a Newtonian worldview. As Robert Dahl wrote in a foundational article on power in 1957, power and risk may be complicated, but “they don’t defy the laws of nature as we understand them.”Footnote 99 The role of uncertainty in the world was not a matter of concern within a Newtonian worldview or paradigm.

In the late 1960s, Graham Allison shifted away from anchoring international relations scholarship in images.Footnote 100 He developed three conceptual lenses or paradigms to capture how individuals, organizations, and governments behave. Allison was not interested in developing a comprehensive view of the world as much as picking up different pieces of the world that warrant explanation. As was true of the 1950s, his perspective betrayed a Newtonian worldview. His conceptual lenses perceived a real, known, and knowable world that remained an external and stable reference point.

This was true also for the prolonged discussion of realist, liberal, and Marxist paradigms by scholars of international relations in the 1980s and 1990s, which paralleled the discussion of rationalism, institutionalism, structuralism, and culturalism in the field of comparative and American politics.Footnote 101 Paradigmatic “isms” became the foundational worldviews or approaches for understanding world politics. Disagreements among analytical or substantive paradigms occurred on the firm ground of a single, real, stable world that was subject to law-like generalizations or mechanism-based analyses. The uncertainties of that world did not figure in the discussions. Furthermore, substantive political paradigms offered communities of purpose and value and focused on the problem of alternative consequences of action. With no single paradigm prevailing, each one asserted its own particular view as sacrosanct.Footnote 102 Indeed, each paradigm sought to “convey a world view more basic than theory”Footnote 103 and, following Kuhn (indeed, often directly inspired by him), viewed itself as incommensurable with all other paradigms. Hence, engagement with proponents of competing paradigms was viewed as a futile exercise. These paradigmatic worldviews were not dynamically competing but frozen in Newtonian time and space; and so too were the risk-based, theoretical worlds they generated.Footnote 104

Substantialism and Relationalism. Analytical and political paradigmsFootnote 105 deal with epistemological problems of the relation between the observing mind and the observed world. They can also embody substantive ontological claims about the world and objects in it.Footnote 106 Their more or less explicit epistemological and ontological claims take the form of substantialism or relationalism.

In Newtonianism, substantial entities such as individual objects or persons exist with their internal characteristics prior to interacting with other entities. Social entities are aggregates of individuals.Footnote 107 In short, substantialism takes pregiven entities as the starting point and imbues them with properties and agency. Strong versions assume that individual choices are driven by objective or intersubjective features of the world.Footnote 108 Substantialism thus includes actor-centered approaches that rely on the logic of appropriateness.Footnote 109 Norms, culture, and identity are structural features that shape individual and state action. Both rational choice and norm-based approaches view individual human action as the elementary unit of social life. For rational choice approaches, preexisting actors typically “generate self-action” that is consistent with preexisting interests and attributes. Similarly, many norm-based approaches view individuals as “self-propelling … entities” that follow internalized norms that are fixed for the timespan under investigation.Footnote 110 Substantialism expresses the Newtonian worldview in which classical conceptions of atoms as the smallest entities constitute the physical world, just as independent social entities are the building blocks of the social and political world.

Two key concepts in relationalism are processes and yoking.Footnote 111 Rescher defines processes as “coordinated group[s] of changes in the complexion of reality, an organized family of occurrences that are systematically linked to one another either causally or functionally.”Footnote 112 He emphasizes processes as prior (and irreducible) to substances, arguing that this allows for an approach that prioritizes change. Unowned processes, such as nuclear proliferation and the growth of economic interdependence, cannot be viewed as the product of any particular agent’s actions.Footnote 113 Rescher ties a process-oriented view of the world to quantum physics, which suggests that “at the microlevel, what was usually deemed a physical thing, a stably perduring object, is itself no more than a statistical pattern – a stability wave in a surging sea of process.”Footnote 114 He regards the shift away from the atom to particle physics in the understanding of the physical world as analogous to the shift from substantialism to relationalism.

Focusing on boundaries rather than entities, Abbott shares Rescher’s interest in relations.Footnote 115 According to his analysis, social entities come into existence when actors tie social boundaries together in specific ways. He defines boundaries as “difference[s] of character,” which are gradually sorted into two sides to form stable properties through social interactions.Footnote 116 The idea of yoking refers to the connection of such boundaries by social actors in a way that defines entities inhabiting one or the other side of the social boundary. Abbott offers the example of the concept of social work, which did not exist prior to the late nineteenth century. It was created by the yoking together of different boundaries related to gender, training, and prior professional attachments. Abbott’s description of relationalism thus stresses intersubjectivity and social context in a way that Rescher’s process-oriented philosophy does not.

Extending this perspective, Laura Zanotti follows Karen Barad’s lead by taking “quantum ontologies” as the starting point for her analysis of a strong version of relationalism.Footnote 117 The fundamental ontological indeterminacy in the natural world “can only be contingently resolved in the intra-action between the observer, and the observed, the human, and the non-human.” In giving relations rather than substances primary ontological status, this is similar to the approaches discussed earlier. But it goes beyond them in positing a specific relationship between human and nonhuman aspects of the world. Zanotti relies on the concept of “apparatus” – ways of engaging with the world – to refer to the means by which boundaries and properties of objects are determined and ontological closure is achieved. Agency should not be considered a property that individuals possess. It operates, rather, through the apparatuses we use “to bring about differentiated forms of materialization of matter and the social.”Footnote 118 Agency is not a free-floating means for humans to enact their will on the world. It is instead caught up in complex entanglements of the human and nonhuman.Footnote 119 This version of relationalism incorporates uncertainty even more fully into its analysis than versions that focus on processes or boundaries.

In the field of political economy, the Open Economy Politics (OEP) approach exemplifies some of the advantages and disadvantages of substantialism and relationalism. OEP is readily intelligible and generates useful baselines for what to expect in the world. But it lacks “sensitivity to the social fabric of international politics.”Footnote 120 That shortcoming was readily apparent after the financial meltdown of 2008–9. After the dust had settled, OEP had precious little to offer by way of analysis or interpretation to help in our understanding of the greatest uncertainty-induced calamity in the international political economy since the 1930s.Footnote 121 Similarly, international relations scholars often characterize international interdependence in substantialist terms. They describe international interdependence with a focus on the strategic interaction among purposive actors. According to Milner, under conditions of interdependence, states’ “actions and attainments of their goals are conditioned by others’ behavior and their expectations and perceptions of this.”Footnote 122 This conceptualization emphasizes preexisting entities with interactions that affect their ability to achieve various objectives. An alternative, relational account of interdependence might “focus on the ways in which trade and other networks are constitutive of boundary conditions of the state and other projects,” as Jackson and Nexon argue.Footnote 123 These examples highlight the differences between a substantialist approach that takes entities as the starting point for analysis and a relational approach that looks at how one set of relations gives rise to others. Indebted to Newtonianism, substantialist approaches tend to focus on the concept of risk and neglect uncertainty’s central place in world politics.

In short, substantialism expresses a Newtonian worldview. A wide range of outcomes in closed systems can be explained with reference to a few abstract, universal principles.Footnote 124 Autonomy refers to the notion that “actors are analytically distinguishable from the practices and relations that constitute them.”Footnote 125 Rational choice approaches seek to abstract from specific contexts. Models are generally transposable. This produces “timeless, context-free, and abstract knowledge,”Footnote 126 as opposed to a relational, practice-oriented Post-Newtonian worldview. It emphasizes an indeterminacy that can be resolved in contextually specific processes of materialization. Mayntz and Scharpf’s actor-centered relationalism combines actor autonomy with contextual factors.Footnote 127 It does not give explanatory primacy “to specific features of the immediate spatial-temporal environment in which actors operate.”Footnote 128 Instead, it assumes that social relations embed actors and constrain their autonomy. The relations in which actors are embedded generate key actor attributes, capacities, and characteristics. Contextualism can be either “thin” or “thick.” Thin contextualism allows for some level of generalization about actor relations and positions; actors and context are analytically separable. In contrast, “thick contextualism” focuses on immediate lifeworlds and the local experiences of actors; actors do not have a clear analytical status independent of their contexts and analysis is more resistant to generalization.Footnote 129

Yaqing Qin’s eclectic view of world politics draws on both substantialist and relationalist elements.Footnote 130 It is partly substantialist and Newtonian, as it highlights the importance of cultural background knowledge of civilizational communities. Culture for him is an indelible birthmark, a crystallized background knowledge of worldviews and all theoretical systems. Qin argues that practice theorists such as Adler and Pouliot limit their notion of communities of practice with shared background knowledge too severely to those that form around specific groups (such as activists, diplomats, and epistemic communities) operating in bounded issue areas (such as national security, the environment, or the economy).Footnote 131 He defines culture as “the way of life of a people who share a lot in terms of behaviors, values, beliefs, and perspectives without consciously knowing them … [A] cultural community is a group of people bound by background knowledge.”Footnote 132 According to Qin, the differences between, for instance, Western and Chinese cultures mean that scholars based in these cultures develop different social theories of how the world works.Footnote 133 Like Huntington, this formulation flirts with a reification of culture as a unified object neglecting contestation and conflict within and encounters and engagements between cultures and civilizational complexes.Footnote 134

Qin is also a Newtonian humanist. While Mustafa Emirbayer, like Jackson and Nexon, views relations as a “general term … [that] may involve human and non-human factors,” Qin’s approach specifically concerns relations between humans in a Newtonian manner;Footnote 135 the Confucian and Daoist philosophies Qin draws on understand relations between humans to be the foundation of social theory and ethics. Importantly, “state actors” are treated as humans and, apparently, as unitary actors. And so are civilizational complexes, as illustrated by Qin’s discussion of the relations between China and the Soviet Union.Footnote 136

The focus on human relations entails a focus on human agency. Qin critiques the concept of yoking as a “temporo-spatial chance with few human elements involved. In other words, nothing would happen if the necessary processes were not related, perhaps by chance.”Footnote 137 By contrast, his focus on human relations puts human agency at the center of relationalism. This is reflected in his discussion of Jackson and Nexon’s view of “relations before states,” by which they mean that relations are ontologically prior to states.Footnote 138 Qin does not believe that relations should be seen as prior to actors. Instead, relations and actors are constitutive of one another: actors are defined by their relations, and relations are always between actors. In this way, actors and relations are coconstitutive “processual simultaneities.”Footnote 139 The agency implicit in these relations between human actors is in turn important for harmony and balance, key concepts in Qin’s approach. He argues that “human agency provides the sufficient condition for harmony … When both the self and the other have learned through education and self-cultivation how to behave appropriately, their behavior is neither too aggressive nor too humble. … As a result, the relationship between the self and the other is harmonious and society is harmonious, too.”Footnote 140 Culture, harmony, balance, and human agency are indelibly linked in the production of social orders.

In his treatment of dialectics, in contrast, Qin leans toward processualism and articulates a relational Post-Newtonian worldview. He argues that Western notions of dialectics, typically relied on by both substantialist and relational approaches, are fundamentally different from the idea of “zhongyong dialectics” in Confucian and Daoist thought.Footnote 141 While Western notions of dialectics – drawn mainly from Hegel – emphasize difference, conflict, and irreconcilability, zhongyong dialectics are based on harmony and “immanent” relationships between polarities.Footnote 142 In Qin’s understanding of a dialectical relationship, each pole is inclusive of its opposite; they are both “always engaged with each other in the process of becoming the other.”Footnote 143 In contrast to Abbott, entities are not yoked – that is, socially constructed through the tying together of proto-boundaries – as much as each side of a boundary already includes the other.Footnote 144 The social world is thus marked by harmony or balance between different poles. Qin’s eclecticism works along the substantialist–relationalist continuum. His reliance on both Newtonian and Post-Newtonian worldviews remains implicit, and the potential for incorporating both risk and uncertainty into his analysis remains unexplored. In Qin’s approach, worldviews inform analytical perspectives more or less directly. Conversely, and less strongly, analytical perspectives can occasionally have a small impact on worldviews. Both are coevolving, competing, or complementary ways of understanding or engaging with the world. Since Newtonian concepts are baked into our conventional language, Qin’s anthropocentrism takes for granted absolute dimensions of time and space as a background into which political actors are placed and analysis is conducted at a distance. In contrast, Post-Newtonianism acknowledges no background, and time and space are active processes of becoming that shape politics and political analysis.

Students of world politics have relied on paradigms as the core construct to debate both analytical and substantive views of the world. With rare exceptions, the substantialism and relationalism that inform their approaches never question a deeply ingrained Newtonian worldview.Footnote 145 Typically, that worldview encompasses a substantialist ontology, a probabilistic epistemology, and a commitment to replicable techniques that can help in error reduction. As John Ruggie observed almost thirty years ago, “As for the dominant positivist posture in our field, it is reposed in deep Newtonian slumber wherein method rules.”Footnote 146 It is this Newtonian slumber that conceals the constitutive part of uncertainty in world politics.

1.3 Newtonianism vs. Post-Newtonianism (Quantum Mechanics)

To grasp more fully the implicit worldview that makes it so difficult for students of world politics to accept uncertainty as a constitutive factor of world politics, this and the next section discuss some salient differences between Newtonianism and Post-Newtonianism (quantum mechanics) on the one hand, and humanism and hyper-humanism (scientific cosmology) on the other. My discussion of quantum mechanics and scientific cosmology is selective. Many of the issues I touch on are considered either peripheral (by most experimental physicists) or contestable (by scientific cosmologists). That is not to say that there are no widespread agreements on the meaning of the stunning and rapidly accumulating experimental and observational findings in both fields, as is true, for example, of the broad support for the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics. I have tried to capture how both fields are thinking about the natural world, in sharp contrast to Newtonianism and the conventional view shared by most students of world politics, which leaves no space for uncertainty.

Although scientific discoveries often defy common sense, worldviews integrate them into social and political life.Footnote 147 In the analysis of world politics, the best Newtonian scientific knowledge searches for law-like correlational statements and causal mechanisms.Footnote 148 The external world is real. Representational knowledge is located in absolute dimensions of time and space. And knowledge has a status that is independent of the observer. The simple billiard ball model of international relations, conventionally taught to first-year college students, is a good example of a mechanistic application of cause-and-effect reasoning. Following the example of economics, many scholars of world politics look to Newtonian physics as their main source of scientific inspiration.Footnote 149 But after he had listened to a Nobel Prize economics lecture, physicist David Mermin observed pithily that with its integrals and derivatives, economics was just “like physics, except physics works.”Footnote 150

Newtonianism. Newton’s laws of motion articulate a universal set of principles to account for planetary movements: “The prototype for the order of universal natural law is universal gravitation, set forth in all its magisterial generality by Isaac Newton in his Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy.”Footnote 151 Newton assumed that movement occurs in relation to absolute space and time. Imagined as a large empty container or background, each bit of space is exchangeable. God invented matter and created the moving objects that fill this space. Nature is governed by objective principles. Thus, Newton arrived at the view of a clock-like universe: a consistently working machine that reflects a hidden order, captured by the universal laws of motion and accessible to human reason and observation.Footnote 152

A scientific Newtonian worldview began to replace a metaphysical religious one in sixteenth-century Europe. Knowable laws of a predictable Nature replaced the unknowable arbitrariness of an all-knowing God. Science encouraged self-organization and undermined existing hierarchies. In the hands of Kepler, Galileo, Descartes, Newton, Spinoza, and Leibniz, mathematics as the most knowable of the sciences was always also philosophical or even religious. The Newtonian worldview does not deny God as the creator of the world. But it does make God a mathematician and His logical plan becomes available for scientific interrogation. Human perception of the world is skewed; mathematics is not. It can fully understand and predict the linear interactions between the discrete objects of this world. Matter is dead; the human mind is not. And it can control and bend Nature to humanity’s will. Relying on an inherent universalism, linearity, and reductionism, and superseding Aristotle’s syllogistic logic and Descartes’ deductive tendencies, Newton’s inductive scientific methodology led him to the higher scientific truths articulated in his three laws:Footnote 153 “Newton, more than any other man, had banished mystery from the world by discovering a “universal law of nature,” thus demonstrating what others had only asserted: that the universe was rational and intelligible through and through, and capable, therefore, of being subdued to the uses of men.”Footnote 154

Newtonianism has a powerful grip on the social sciences, including important strands in political science and, specifically, international relations.Footnote 155 In the Newtonian worldview, “the world was considered to be deterministic. Blended with the atomized and axiomatic approaches to the study of science, reason had in many senses become rationalism. Society was there to be solved.”Footnote 156 It made “the world feel less anarchic and more predictable,” and “strengthened the commonsense belief in a world designed by a higher intelligence and a superior force” – for some God, for others the Laws of Nature.Footnote 157 The assumed order of the world held forth the promise of control. The sciences do not eliminate from our lives the irrational, mystical, and religious. Far from it. But, as illustrated by conventional scientific practices, the notion of control continues to have a powerful grip on students of world politics and the social sciences more generally, at times as a metaphor “with a quasi-poetic function.”Footnote 158 Since the eighteenth century, atomistic natural philosophy and, specifically, Newton’s image of the universe, has left an indelible mark on political thought.Footnote 159

As the reigning scientific worldview, Newtonianism thus informs the conventional understandings of world politics. For example, the mechanical foundations of Newtonianism have had a strong effect on the progressive imagination of the American Founding Fathers and modern theorists of a recurrent balance of power.Footnote 160 Liberalism and realism share the Newtonian view of the political universe as self-sustaining and self-regulating objects or actors. In both, the flux of events is viewed as subject to fixed laws or statistical regularities. Entities are knowable and can be governed by humans. And humans are set apart in nature by the power of their reason.Footnote 161

In search of intellectual simplicity, the analysis of world politics typically homogenizes reality by conflating a large number of diverse political phenomena and entities under a small number of concepts. It also adopts strong assumptions about how world politics works, using statistical analysis or experiments to support its search for simple causal relations. This approach to understanding the world hews closely to Newton’s own words: scientific truth is to be found, “in the simplicity, and not in the multiplicity and confusion of things.”Footnote 162 When we explain world politics by making simple distinctions – East and West, land and water, then and now – we follow Newton’s advice.

As a matter of fact, Newton encountered multiplicity and confusion in human affairs, and painfully so. In the spring of 1720 he sold his shares of the South Sea Company, pocketing a 100 percent profit of £7,000. The price of the shares continued to rise. Not wishing to lose out on this speculative frenzy, Newton bought shares back at three times the price of his original investment. The bubble burst a few months later and decimated Newton’s savings as he reportedly lost the equivalent of $3 million in today’s money. He subsequently lamented that “I can calculate the motion of heavenly bodies but not the madness of people.”Footnote 163 This “multiplicity and confusion of things” is central to a Post-Newtonian worldview.

Although students of world politics share Newton’s befuddlement about the unexpected, they hold fast to his orderly worldview. The typical response to the often shocking predictive and explanatory failures of their preferred constructs has been to reexamine their theories and models with the hope that, eventually, the Newtonian strategy of simplification will lead to the discovery of valid laws and causal mechanisms that generate compelling explanations and accurate predictions.Footnote 164 This, however, is not how it turned out in physics. Most physicists agree that quantum mechanics has superseded Newtonian physics and simply get on with their work.Footnote 165 Modern physics and cosmology have discarded Newton’s notion of absolute space and time. Although the classical model remains a convenient computational tool for many practical problems, it conveys a misleading view of nature as orderly and accessible to neutral observation, when the reality is rather disorderly and often barely accessible. Furthermore, despite its practical usefulness, the classical model is inadequate for understanding the subatomic world and thus fails to account for the many practical applications of particle physics. It does not offer a general explanatory framework.Footnote 166 To be sure, some physicists held tight to their belief in a Newtonian world. Slowly but surely, however, most acknowledged the failings in their worldview and moved on. This process became less difficult after a plausible alternative presented itself.

Post-Newtonianism. In the late nineteenth century, experimental physics began to probe the subatomic structure of matter. Electrons, quarks, photons, gluons, neutrinos, and a few “Higgs bosons” are the elementary particles studied by quantum mechanics.Footnote 167 It describes these particles and their movement. They are not real, like little pebbles; “They are the elementary excitations of a moving substratum … miniscule moving wavelets.”Footnote 168 Einstein’s special relativity theory of time and space, and relativistic quantum field theory more generally, opened up an invisible world of energy governed by randomness. Nineteenth-century philosophical relationalism inspired the first, philosophically informed generation of quantum physicists to think relationally about many of the new phenomena they discovered with ingenious experiments. Only subsequently did a materialist and quantized version of relationalism claim to be foundational because it was “real.” Although the weirdness of the quantum world has defied all attempts at explanation, the new theory became a marvel of predictive accuracy. It has generated technological innovations and applications that continue to revolutionize the social and political world despite the scant attention paid by students of world politics.Footnote 169

Early on, though, some prominent political scientists recognized the importance of new developments in physics. William Bennett Munro, President of the American Political Science Association, delivered his address on the topic of “physics and politics” in 1927, regretting that the study of government was “still in bondage to the eighteenth-century deification of the abstract, individual man.”Footnote 170 In Scientific Man vs. Power Politics, which he described toward the end of his career as his favorite among his voluminous writings, Hans Morgenthau explicitly recognized the significance of changes in physics for the analysis of world politics.Footnote 171 This work was published in 1946, a few decades after the quantum revolution, and Newtonian physics for Morgenthau already was “a ghost from which life has long since departed.”Footnote 172 Since the classical model had been disproven and rejected by physicists, it no longer could serve as an adequate guide for the social sciences and students of world politics. It needed to be replaced by the complex worldview of quantum mechanics. Morgenthau argued that the scientific studies of world politics would have to settle for a disquieting mixture of the knowable and the unknowable.Footnote 173 Quantum physics had introduced indeterminacy and thus radically transformed the calculable, determinist universe of the classical model.Footnote 174 Complete knowledge of either past or future had become a chimera, as scholars came to acknowledge that their current approach to understanding world affairs would never yield reliable predictions of individual events: “The next quantum jump of an atom is as uncertain as your life and mine.”Footnote 175 Out-of-equilibrium nature does not know its own future, and neither do we. And while probabilistic predictions and scientific laws can provide insights into the modal tendencies of statistical aggregates, they are like quantum physics in that they cannot provide any insight into individual units of observation. Morgenthau thus called for a thorough revision of simplified social science modeling.Footnote 176 He pleaded that the unification of the natural and the social sciences should be triggered by their shared ignorance when confronting the unknowable and the insuperable. We can thank Morgenthau for positing that, when we take quantum mechanics rather than the classical model as our guide, “the structure of the natural world finds its exact counterpart in the social world.”Footnote 177 Seventy-five years later, students of world politics are still trying to catch up.

Many baffling aspects occur in the subatomic world. Quantum physics cannot be visualized. It is not determinist. Quantum effects depend on the size of an object multiplied by its typical momentum; for electrons moving in an atom, quantum uncertainties predominate.Footnote 178 The world is not a causal machine but a creative generator of realized and unfolding propensities and potentialities.Footnote 179 The inventors of quantum theory also discovered the observer-created reality that flies in the face of notions of objectivity.Footnote 180 Quantum mechanics directs our attention to apparatuses of measurement and argumentation, and the performances and practices they entail.Footnote 181 They bring to light relational aspects of difference; the boundary-producing effects of measurement and argumentation; and the entanglements between objects and subjects, matter and meaning, and the natural and social worlds.Footnote 182

Life does not evolve in space and time conceived, respectively, as a collection of preexisting points in an empty container that matter inhabits and as a succession of evenly spaced intervals available as a referent for all bodies. Instead, following Einstein, life is an iterative evolution of four-dimensional spacetime.Footnote 183 Space is not empty. Far from being vacant, a vacuum teems with possibilities.Footnote 184 The fields that make up the world are subject to tiny fluctuations. Basic particles have ephemeral existences that are continually created and destroyed:Footnote 185 “The world is a continuous, restless swarming of things, a continuous coming to light and disappearance of ephemeral entities … A world of happenings, not of things.”Footnote 186 Indeterminacy provides the condition for an open future. Possibilities are not static. They are always reconfigured and reconfiguring.Footnote 187 New possibilities open up as others close down. Although the world’s presentation of an infinitude of relational possibilities cannot be controlled, it can be captured by conventional experiments and the imposition of isolated, efficient cause-and-effect chains. In this view, uncontrollable surprises are normal in a world of changing possibilities. Subatomic particles are wrapped up in infinities of possibilities that have changed our image of the atom and our practices of imagining.Footnote 188 Quantum mechanics puts uncertainty, indeterminacy, potentiality, and possibility, rather than constraint and necessity, at its center. It offers an alternative to Newtonianism that students of international relations are largely unaware of as they think about the nature of world politics and its many uncertainties.

A century of astoundingly successful experimental work has yielded no agreement about the meaning of quantum theory.Footnote 189 However, it has generated powerful experimental results establishing, for example, particle entanglement without any observable mechanisms, creating what Einstein called “spooky action at a distance.” Different approaches and interpretations illustrate that crucial aspects of the meaning of quantum physics remain unresolved.Footnote 190 But most physicists would agree with Rovelli that the key insight of quantum physics is “the relational aspect of things.”Footnote 191 Smolin goes so far as calling “the 20th-century revolution in physics the relational revolution … in full swing in the rest of science.”Footnote 192 Although it is not free of internal contradictions, what has come to be known as Niels Bohr’s Copenhagen interpretation remains the most widely accepted. This is not to deny the existence of important critics of Copenhagen, including Albert Einstein, David Bohm, Hugh Everett, and John Bell.Footnote 193 Disagreement centers on the nature of measurement.Footnote 194

“Quantum Realists” believe that the history of the world is a history of endless splits, which occur every time a macroscopic body is tied to a choice of quantum states. This view stipulates the existence of an inconceivably large number of uncorrelated multiverses. For David Mermin, this is “the reduction ad absurdum of reifying the quantum state.”Footnote 195 Its plausibility, furthermore, is impaired by the requirement that conditions in our universe have to be just right.Footnote 196 Realists are waiting for a post-quantum revolution that, perhaps, would make quantum mechanics a special case of a more general theory, such as “objective collapse models” or some other theory not yet invented. Such a revolution could thus repeat a new cycle in which quantum physics would be subsumed, just as it subsumed Newtonian physics in the early twentieth century. Physics Nobel Prize winner Steven Weinberg characterized that quest as interesting but also “to some extent whistling in the dark.”Footnote 197 And while physicists work, scholars of international relations wait and remain beholden to Newtonianism and the denial of uncertainty as a constitutive part of world politics.

“Quantum Instrumentalists” believe that measurements of the world taken by humans themselves affect that world at a most fundamental level. The world is therefore not governed by impersonal physical laws that control human behavior together with everything else. Discussed further in Chapter 10, Quantum Bayesianism (or QBism), for example, offers a radically subjective interpretation of quantum mechanics that provides a coherent, unconventional answer to the mysterious meaning of the subatomic world.Footnote 198 The probability that one or another quantum state will emerge is not regulated by firm Newtonian laws that are irrevocable and universal. Instead, individual human actors assign these probabilities on the basis of their private beliefs. Based on past experience, updating that experience with new information, and adhering to the rules of Bayesian statistics, individuals calculate what might happen next. This process does not involve any physical laws or mechanisms operating on the wave function conceived of as a mathematical abstraction, rather than as an objective entity existing out there in the real world. It involves only individual experience, belief, and updating. Individual experience is intrinsically private and cannot be accessed by others. This does not mean that the world exists only in an individual’s head. QBism is not solipsistic. Instead, each individual holds to the subjective belief, with the highest degree of confidence (p=1.0), that others experience the world as oneself does, and all rely on verbal or nonverbal communication to create the intersubjectivity and entanglement which, in turn, create a social world out of individual experience and belief. We are not free to make up our own individual world. QBism provides instead for a world that exists external to each actor without reifying that world as an extant, external entity.

QBism differs diametrically from Wendt’s pathbreaking book on quantum consciousness.Footnote 199 Wendt’s research program is foundational. He seeks to create a consistent, coherent, and complete system of knowledge, grounding human consciousness in the materiality of the world. His work is in line with the view of 2020 Nobel Prize–winning physicist Roger Penrose. QBism is pragmatic. It takes experience (or Wendt’s consciousness) as given before making its argumentative move. QBism works in the tradition of Dewey’s pragmatism.Footnote 200 Knowledge is not a set of securely anchored systematic propositions. “The claims to knowledge we can defend by our impressive scientific successes,” writes Nancy Cartwright, “do not argue for a unified world of universal order, but rather for a dappled world of mottled objects.”Footnote 201 Knowledge is a set of successive attempts to cope with problematic situations that are more or less successful in historically variable, polymorphic contexts.Footnote 202 Like all of physics, QBism is a product of human thought and culture. For QBism there is no “reality” out there; it is all in our heads and the world is created through individual experience, beliefs, information updating, apparatuses of measurement and argumentation, and the creation of intersubjectivity through communication. For QBism, human experience (or Wendt’s consciousness) is foundational and creates the quantum world; for Wendt, quantum physics is the foundation on which he grounds his far-ranging search for consciousness (or QBism’s experience). For QBism, the move is from individual experience (or consciousness) to the world; for Wendt, the move is from the world to individual consciousness (or experience). For QBism, worldviews are epistemologically grounded; for Wendt, individuals are ontologically walking wave functions. These research programs and argumentative moves are opposite but not necessarily antithetical. Chewing on different ends of the same stick, it is not a far-fetched hope that somewhere, sometime, someone will succeed in making them meet.

1.4 Humanism (Dilthey and Weber) vs. Hyper-Humanism (Scientific Cosmology)