INTRODUCTION

Abdominal pain is a common presenting complaint during childhood. Although a wide variety of etiologies are associated with abdominal pain, appendicitis is the most common surgical cause in children.Reference Green, Bulloch and Kabani 1 Historically, there has been concern that analgesia could mask signs or symptoms of appendicitis, leading to diagnostic difficulty, and therefore worsened outcomes.Reference Vane 2 , Reference Armstrong 3 However, this belief has been clearly refuted by recent evidence.Reference Green, Bulloch and Kabani 1 , Reference Manterola, Vial and Moraga 4 - Reference Kang, Kim and Kim 7 Multiple pediatric randomized controlled trials and a recent systematic review demonstrated that, when opioid analgesia is provided, there is no difference in accuracy and timeliness of diagnosis of appendicitis and no difference in rates of appendicitis-related complications.Reference Green, Bulloch and Kabani 1 , Reference Bailey, Bergeron and Gravel 5 , Reference Poonai, Paskar and Konrad 6 , Reference Kokki, Lintula and Vanamo 8 Further, a Cochrane review of adults with acute abdominal pain has also demonstrated that analgesia does not mask appendicitis or delay the diagnosis.Reference Manterola, Vial and Moraga 4

In recent years, the importance of appropriate and timely analgesia for children has become increasingly recognized. The World Health Organization considers analgesia to be a fundamental human right.Reference Cousins and Lynch 9 In addition, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) advocates for prompt pain assessment and analgesia provision in the emergency department (ED), and advises not to withhold analgesia in children with abdominal pain.Reference Fein, Zempsky and Cravero 10 For severe pain, the AAP recommends systemic opioid analgesics.Reference Fein, Zempsky and Cravero 10 Appendicitis is known to be a painful condition; recent literature reported that 50.1% of children with appendicitis had pain scores consistent with severe pain, with an additional 40.9% in moderate pain.Reference Goyal, Kuppermann and Cleary 11 Therefore, given the likelihood of moderate to severe pain in appendicitis, optimal management would be to provide analgesia early in an ED visit, with the majority of patients receiving opioid analgesics.

Despite this, analgesia provision for children with acute appendicitis may still be inadequate, either due to low rates of opioid provision, underdosing of analgesia, or extended time delays prior to receipt of analgesia.Reference Goyal, Kuppermann and Cleary 11 - Reference Delaney, Pankow and Avner 13 The reasons for this are multifactorial and include age-dependent clinical presentation, difficulty in assessing pain in children, lack of comfort in using opioids in children, time constraints in busy acute care settings, and unwarranted concerns of obscuring the signs and symptoms of a surgical abdomen.Reference Fein, Zempsky and Cravero 10

A review of current practice patterns regarding pain management may encourage and form a basis for focused knowledge translation strategies to support optimal analgesic use for suspected appendicitis in children. We sought to describe current practice surrounding pain management for suspected or confirmed acute appendicitis in children across Canadian pediatric emergency departments (PEDs).

METHODS

Study design

This was a planned substudy of a retrospective, multicentre, medical record review of practice variation in children admitted to the hospital for suspected appendicitis.Reference Thompson, Schuh and Gravel 14 We hypothesized that suboptimal analgesia would be provided to children with suspected appendicitis. This study was approved by the Conjoined Health Research Ethics Board (CHREB) at the University of Calgary and the research ethics board at each participating institution.

Setting and participants

Twelve Canadian PEDs participated in the study, all of which are members of both Pediatric Emergency Research Canada and the Canadian Association of Pediatric Surgeons. Medical records of children ages 3 to 17 years who were admitted to the hospital with an ED diagnosis of appendicitis or suspected appendicitis were eligible for inclusion in the study. Medical records were reviewed for eligibility starting in two separate time periods (February and October 2010) to limit bias related to seasonal variation in both patient presentations and physician practice. During seasonal peaks in patient volume, analgesia could be prolonged due to long wait times and limited staffing resources. Medical records were reviewed sequentially by trained research assistants until a minimum of 25 records were collected in each time period, for a total minimum convenience sample of 50 records per site. This method of sampling was chosen to limit data skew from large institutions that would see more cases of appendicitis each month than smaller sites. Medical records were excluded if the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit or if the patient had been partially or fully investigated at another site. The ED visit that led to admission was the only source of data in patients who had repeated presentations.

Methods and measurements

Data relevant to analgesic provision were extracted from the standardized data abstraction forms used by the parent study directly into a study-specific Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (version 14.3.8, Redmond, WA).Reference Thompson, Schuh and Gravel 14 Patient demographics, including age, sex, Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) rating, and surgical outcomes were included, with the goal of stratifying analgesic provision by CTAS score and age group. Data regarding specific analgesic agents were collected, including frequency of use of specific analgesic agents and doses prescribed. Data pertaining to timing of analgesic provision during the visit were also collected, including time from triage to an initial dose of analgesia and the timing of analgesic with respect to surgical consultation and PED interventions.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the proportion of children with suspected acute appendicitis who received any analgesia while in the ED. Secondary outcomes included the relative frequency of use of different types of analgesia, the proportion of children who received opioids for suspected appendicitis, the median time to initial provision of analgesia, and timing of analgesia relative to medical interventions such as ultrasound performance and surgical consultation.

Analysis

Continuous, normally distributed data were summarized using means and standard deviations or percentages and frequencies, as appropriate. Non-parametric data were summarized using medians and interquartile ranges. Differences in proportions were analysed using the Fisher exact test. A p-value of 0.05 was deemed significant. Data were analysed using SPSS (version 20, IBM SPSSTM, New York, NY).

RESULTS

Demographics

Data from 619 medical records were included in the review, with the number of records per site varying from a minimum of 50 to a maximum of 55. The mean (SD) patient age was 11.4 (3.5) years. The median (IQR) length of stay in the PED was 395 (277.5, 544.5) minutes, or 6.6 hours. Further patient demographics are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1 Demographic characteristics of children with suspected or confirmed acute appendicitis (N=619) (Site-specific data are available in parent study.)

Analgesic use

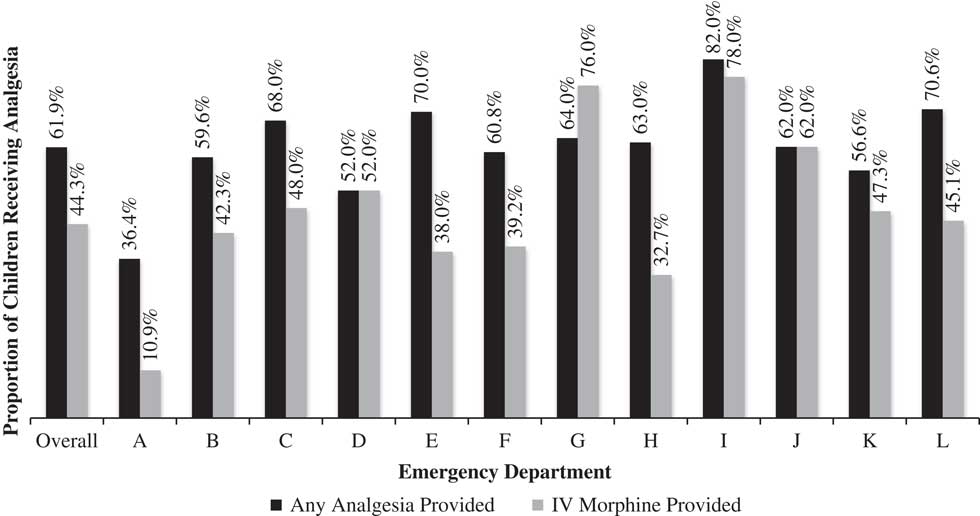

Overall, 61.8% (381/616) of children received analgesia while in the PED. Across sites, there was an overall significant difference in the proportion of children receiving analgesia (p<0.01), ranging from 36.4% q(20/55) to 82.0% (41/50) (Figure 1). The proportion of children receiving individual analgesic agents is reported in Table 2.

Figure 1 Proportion of children who received either any pharmacologic analgesia or any intravenous morphine while in the emergency department (N=616), displayed overall and by site. The relation between site and receipt of analgesia was significant (p<0.01), as was the relation between site and opioid provision (p<0.001).

Table 2 Proportion of children receiving individual analgesic agents (N=616)

IM=intramuscular; IV=intravenous; PO=oral.

Opioid use

Overall, 47.9% (295/616) of all patients received an opioid analgesic while in the PED. Of the children who received analgesia, 77.4% (295/381) received an opioid analgesic. Rates of opioid provision were significantly different across sites (p<0.001). Morphine was the most frequently provided opioid analgesic (see Table 2), with 44.3% (273/616) of all children receiving morphine by any route. The lowest proportion of children receiving morphine at any one site was 10.9% (6/55), and the highest was 78.0% (39/50). For the initial dose of intravenous (IV) morphine, the median (IQR) weight-based dose was 0.06 (0.04, 0.09) mg/kg.

When patients were stratified according to age group, there was a significant overall difference in the administration of any opioid (p<0.001). IV morphine was the most common opioid administered in each age group; 77.8% (21/27) of preschool children (3 to 5 years), 59.3% (108/182) of school-aged children (6 to 12 years), and 79.1% (136/172) of adolescents (13 to 17 years) received IV morphine.

Thirteen percent (83/619) of patients were triaged as either a 1 (resuscitation) or 2 (emergency) on the five-level CTAS, and 77.1% (64/83) of these patients received analgesia. Of the sixty-four who received analgesia, 79.7% (51/64) received opioid analgesics. There was no significant relationship between a more severe acuity score (CTAS 1 or 2) and opioid administration (p=0.06).

Timing of analgesia

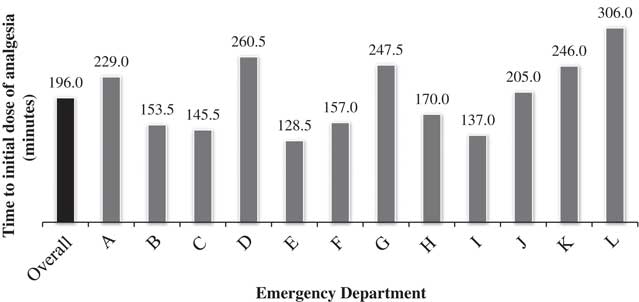

The median (IQR) time from triage assessment to an initial dose of analgesia was 196.0 (101.0, 309.5) minutes, or 3.3 hours. There was significant overall variation across sites (p<0.005). The shortest median (IQR) time to analgesia at a single site was 128.5 (34.8, 283.8) minutes (2.1 hours), and the longest was 306.6 (172.5, 412.5) minutes (5.1 hours) (Figure 2). Of those patients who received analgesia, 43.5% (117/269) received their initial dose after surgical consultation was performed (p<0.05). Forty-four percent (121/277) received their initial dose of analgesia after an abdominal ultrasound to investigate appendicitis was completed (p<0.05).

Figure 2 Median duration of time between triage assessment and initial dose of analgesia, in those patients who received analgesia (N=378), displayed overall and by site. There was significant variation across sites (p<0.005).

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that variable provision of analgesia remains prevalent in proven or suspected cases of pediatric appendicitis across Canadian PEDs. Analgesia provision appeared suboptimal with regards to underdosing, delayed timing, and inappropriate use of mild oral analgesics for a condition that is known to cause moderate to severe pain in 91% of patients.Reference Goyal, Kuppermann and Cleary 11 Only two-thirds of children received any analgesia while in the PED. Despite being the recommended analgesic for severe pain, less than half of all children in our national study received an opioid analgesic agent.Reference Bailey, Bergeron and Gravel 5 , Reference Fein, Zempsky and Cravero 10 , Reference Cole and Maldonado 15 The factors contributing to the significant variation amongst sites are not identified in this study but may relate to variations in policies or protocols, surgeon preferences, or PED volumes.

Our study suggests that current practice in Canadian PEDs does not reflect the known importance and safety of analgesia in the treatment of children with acute abdominal pain.Reference Green, Bulloch and Kabani 1 , Reference Manterola, Vial and Moraga 4 , Reference Bailey, Bergeron and Gravel 5 , Reference Poonai, Paskar and Konrad 6 , Reference Kokki, Lintula and Vanamo 8 Overall practice patterns are inconsistent with recommendations from the AAP regarding pain management in emergency settings, which state that both pain assessment and management should begin at triage, and that analgesia should not be withheld in abdominal pain.Reference Fein, Zempsky and Cravero 10 When compared practice patterns in prior literature, our study demonstrated similar rates of both overall analgesia and opioid provision.Reference Goyal, Kuppermann and Cleary 11 , Reference Delaney, Pankow and Avner 13 In a recent American study of a large national database, 56.8% of pediatric patients with acute appendicitis received analgesia, with 41.3% receiving an opioid analgesic.Reference Goyal, Kuppermann and Cleary 11 Similarly, a smaller study demonstrated that 60% of patients with acute appendicitis received analgesia while in a PED, with 45% receiving morphine.Reference Delaney, Pankow and Avner 13 Still, practice continues to be suboptimal, given that less than half of all children received an IV opioid.Reference Goldman, Crum and Bromberg 12 , Reference Goldman, Narula and Klein-Kremer 16 , Reference Kim, Galustyan and Sato 17 In our study, IV morphine was provided significantly less frequently to school-aged children as compared to preschool or adolescent. This is in contrast to earlier literature, where younger children have been shown to receive less analgesia for painful conditions.Reference Dong, Donaldson and Metzger 18 , Reference Alexander and Manno 19 Patient refusal of analgesia could have contributed to this finding; school-aged children may be more likely to refuse analgesia due to fear of additional pain of IV access. In addition, underdosing of morphine demonstrated in previous literature persisted in our findings.Reference Poonai, Paskar and Konrad 6 , Reference Goldman, Crum and Bromberg 12 , Reference Goldman, Narula and Klein-Kremer 16

Interestingly, a recent survey of Canadian physicians, including those trained in pediatric emergency, pediatrics, emergency, and family medicine, demonstrated substantially higher self-reported rates of analgesic provision in pediatric appendicitis as compared to our findings.Reference Poonai, Cowie and Davidson 20 In a case of suspected appendicitis, 92.1% of survey respondents reported that they would offer immediate analgesia. Fifty-eight percent reported that they would offer an IV opioid analgesic.Reference Poonai, Cowie and Davidson 20 This may reflect social desirability bias due to self-reporting,Reference Mindell, Coombs and Stamatakis 21 or patient refusal of analgesia. The discrepancy between self-reported rates of analgesia provision and the directly observed rates of analgesia provision suggest that providers are likely aware of the need to provide analgesia. Still, there appears to be persistent barriers to the actual provision of adequate analgesia.

A delay of over 3 hours to provision of analgesia for a known painful condition is arguably universally unacceptable, and deferral of an initial dose until after surgical consult or abdominal ultrasound is incongruent with current guidelines.Reference Fein, Zempsky and Cravero 10 Timing of analgesia provision with respect to abdominal ultrasound is particularly relevant, given the pain associated with ultrasound in a patient who already has abdominal pain. Triage-initiated pain protocols have been shown to be effective in improving the timing and consistency of analgesic provision. In an ED that services both adult and pediatric patients, a protocol for the provision of intranasal fentanyl for pediatric patients with moderate to severe pain significantly reduced the time to an initial dose of analgesia.Reference Holdgate, Cao and Lo 22 There is also evidence of successful multitiered interventions for pain management. In an Australian PED, Corwin et al. demonstrated increased rates of analgesia provision and faster median times to analgesia following a multifaceted intervention that involved education of patients and providers, in addition to organizational changes.Reference Corwin, Kessler and Auerbach 23 Similar encouraging results have been shown for hospitalized pediatric patients. A multisite Canadian study demonstrated that a multidimensional knowledge translation strategy was able to increase rates of pain assessment, increase analgesia provision, and decrease pain intensity scores in hospitalized pediatric patients.Reference Stevens, Yamada and Estabrooks 24 Canadian EDs may benefit from similar interventions to optimize analgesia in acute appendicitis, because the knowledge-to-practice gap shown in our study suggests a need to direct focus towards strategies to improve analgesia provision and introduce consistency across Canada.

LIMITATIONS

There are inherent limitations to retrospective medical record reviews, including the challenge of data being uncharted or unable to be located. In addition, this was a secondary analysis of data collected for another primary objective; therefore, some data of interest, such as pain scores, were not collected. Without pain scores, the true degree of pain for these patients is unknown. Although recent literature suggests 91.0% of patients with appendicitis will have moderate to severe pain,Reference Goyal, Kuppermann and Cleary 11 , Reference Bundy, Byerley and Liles 25 we were unable to determine the severity of pain in our population. In addition, this data set does not capture patients who were offered analgesia and declined. It is plausible that some patients and families refused analgesia for fear of adverse effects, a perceived lack of pain, or mild pain that was not significant enough to require analgesia. Finally, this study only included patients attending PEDs; therefore, these findings may not be generalizable to all EDs. However, the low rates of analgesia provision and long delays prior to analgesia receipt remain as important findings.

CONCLUSIONS

Our multicentre retrospective review suggests that, across Canadian PEDs, suboptimal analgesia provision remains prevalent when treating pediatric patients with suspected appendicitis. Furthermore, current practice patterns are inconsistent with guidelines for the management of appendicitis-related pain children in timing, dosage, and choice of analgesic agent, despite self-reported provider knowledge of the necessity of analgesia.Reference Fein, Zempsky and Cravero 10 , Reference Cole and Maldonado 15 , Reference Poonai, Cowie and Davidson 20 Multidimensional strategies to narrow the knowledge to practice gap in analgesia provision for pediatric appendicitis, including triage-initiated protocols for analgesia and practice guidelines for health care providers, may help address this issue.

Acknowledgements: The above was presented at the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians (CAEP ) Annual Conference in June 2015 in Edmonton, Canada. AR, SA, and GT designed and planned the study. NP contributed to the planning and completion of the statistical analyses. AR drafted the manuscript, with all authors contributing to manuscript revisions and edits. Site-specific study administration and data collection for the original appendicitis practice variation study was performed by members of the Pediatric Emergency Research Canada (PERC) Appendicitis Study Group: Suzanne Schuh, MD; Jocelyn Gravel, MD; Sarah Reid, MD; Eleanor Fitzpatrick, RN, MN; Troy Turner, MD; Maala Bhatt, MD; Darcy Beer, MD; Geoffrey Blair, MD; Robin Eccles, MD; Sarah Jones, MD; Jennifer Kilgar, MD; Natalia Liston, MD; John Martin, MD; Brent Hagel, PhD; and Alberto Nettel-Aguirre, PhD. This study was funded through an internal University Research Grants Committee (URGC) Seed Grant, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB.

Competing interests: None declared.