Introduction

For decades, the dominant paradigm in the sociology of collective action presented the “masses” as incapable of rational deliberation and autonomous means–ends calculation. Over the last thirty years, that assumption has been turned completely upside down. Critical views came first from historians, who underlined the provision of norms and moral standards in explaining explosions of collective violence, yet the paradigmatic shift in the field was effected only with the reception of rational-choice approaches to human behaviour. With the establishment of a consensus on the strategic nature of agency, the rejected version is now available as a topic for more objective historical analysis.

Definitions of collective behaviour as irrational, spontaneous, and unreliable go back to Gabriel Tarde, Gustave Le Bon, and other social psychologists from the early twentieth century, who elaborated their works in the context of a crisis in classical liberalism which had given rise to fears about the emergence of mass politics. As part of a critical reappraisal of those authors, in the last few decades a new generation of social psychologists has reflected on the meanings and usages of terms such as crowd, multitude, and mob in classic texts from the field.Footnote 1 Until today, however, that interest in historical semantics has remained limited both in scope and range. Stereotypes and prejudices about multitudes in action are usually regarded as a universal component of cultures, and specialized research tends to focus on the contributions by the founders of the sciences of social behaviour.Footnote 2

The purpose of this article is to widen our knowledge about the category of multitude through a historical study of its conceptual formation. The process of the conceptualization of the term involved relevant transformations in its meaning before it was coined for a scientific-academic category. Some of those transformations took place as early as the Enlightenment, which appears as a fulcrum in the history of the semantic field of disorder. Focus on the eighteenth century entails an important reorientation in the scope of analysis too. Economics did not exist as an independent science before the mid-nineteenth century,Footnote 3 which means that modern theoretical definitions of rationality cannot be taken as understood in the period being studied here.Footnote 4

Scholars have linked the growth of a public sphere during the Enlightenment with the emergence of representations of the subject as if it were a rational self-interested individual.Footnote 5 The diffusion of the notion of interest functioned as a landmark in the modern distinction between rationality and irrationality, while yet another source of evolution towards this modern dichotomy were notions of the multitude as coined and refined around the revolts and popular upheavals occurring throughout the eighteenth century. The policies enacted in the wake of enlightened despotism unleashed popular disturbances which played out as “laboratories of language”, where the need to cope with the social reactions triggered by institutional reforms demanded new classifications and understandings of conflict which fostered semantic innovations beyond available repertoires.

This article will focus on one particular eighteenth-century popular revolt, the “motín de Esquilache” [Esquilache riots] of 1766. Traditionally interpreted as a combination of food riot and anti-despotic protest, the revolt exploded in the capital of the Spanish monarchy, Madrid, spreading through several towns both on the peninsula and in the Americas. Classical social historians reckoned it was the most widespread, prolonged, and potentially devastating eighteenth-century revolt in western Europe before 1789.Footnote 6 It was nevertheless defeated, so it failed to bring with it a comprehensive alternative framework of semantic referents. Compared with the French Revolution, experimentation with language in the case of Bourbon Spain would be much more constrained by the inherited stock of meanings,Footnote 7 but in this case the investment in discourse for assessing this revolt was significant, given the challenge posed to legitimate order.

A study of the elaboration of a conceptual vocabulary about the social certainly falls within the discipline of intellectual history, but reaches beyond it too. The issues treated in this article are similarly relevant to renewing the field of social history. In recent decades, the so-called “linguistic turn” has challenged classical social history by highlighting the linguistic dimension of all social experience.Footnote 8 Profiting from a growing consensus, the perspective followed by this text tries to supplement social history with historical semantics.

Conceptualization can be understood as a kind of social activity produced by linguistic devices through communication.Footnote 9 Classical social history tended to regard intellectual processes as indices of social change, but concepts themselves can be considered factors of historical transformation which deeply affect social dynamics. Once instituted, they influence human agency by constraining agents in the meaning they can attribute to reality, to their actions, and to those of others. That is so largely because concepts condense different layers of time, so their use in communicative action calls forth cumulative experience and at the same time invokes foreseeable expectations.Footnote 10 Modern concepts in particular contain a whole new temporality which breaks with the past as thelos and orients action towards the anticipation of the future.

Historical semantics can profit as well from other sources of inspiration, especially the “Cambridge School” of intellectual history, whose members have stressed the role of traditions of language and the relevance of context to the elaboration of discourse.Footnote 11 Attention to these dimensions is important for understanding the interplay between the inherited stock of meanings, the reception and re-elaboration of new vocabularies, and semantic transformation.

Conceptual change takes place not only within political processes; it can be regarded itself as a political event.Footnote 12 In the case of terminology relating to conflicts, conceptualization has strong bearings on social classifications affecting the recognition and identity of collective actors. The acquisition of new meanings by riot and multitude after 1766 was part of the response to the challenge made by the populace to legitimate order; the usage of the new concepts in discourse of itself forced a sharp reorientation of state policies. But semantic change had another unaddressed political effect: it informed the official accounts which have been used since as sources for the study of the motín de Esquilache. A study of the conceptual framework of those narratives and documents can offer critical insights useful not only for renewing the interpretation of the riot discussed here in particular but also for rethinking the conventional definition of riots in general.

A legacy of linking riots to conspiracies

Renaissance humanism established a dividing line in Western culture by providing a renewed discourse that devised an autonomous status for the political sphere. Throughout the early modern period, republican tropes reinterpreted from the classical ideal of citizenship were refined and diffused through disputes and arguments in favour of or against civic versions of humanism. A fully fledged tradition of language was thus created that supplied a basic vocabulary on conflict and political agency.Footnote 13 Republicanism made extensive use of two extreme expressions of disorder: revolution and civil war. Originally very close in meaning in the legacy from antiquity, with the rise of centralized monarchies and the raison d’état the two terms experienced a process of differentiation, revolution becoming identified more with concrete situations of extreme political unrest resembling a world turned upside down.Footnote 14

From the very origins of the humanist movement, discourse dealing with episodes of political conflict incorporated a series of anthropological assumptions. The bases and the leadership of upheavals were regarded as composed by two very different social and moral constituencies: the “plebs”, or the mob, were understood to be an amorphous collective of individuals of low social class, easily manipulated, and who, when exposed to fanaticism and roused in great numbers, tended naturally to resort to violence. Leaders, on the contrary, were usually considered individuals belonging to upper social ranks or privileged corporations and were seen as utterly evil characters, plainly conscious of their immoral condition and so capable of managing their passions for plotting.Footnote 15 Such a complex approach made conspiracy a necessary ingredient in any assessment of social disorder: not only minor uprisings or revolutions but even chaotic civil wars were assumed to require the concourse of some kind of intellectual authority and more or less explicit leadership by individuals of higher status. That is what made revolts so potentially dangerous, but at the same time allowed for specialized curtailment and repression on the part of the authorities, who could show mercy to the mobs and focus on conspirators and leaders.

European principalities possessed particular political constitutions and legal frameworks, although languages and frames of reference varied according to contexts, not only over time but also in space. In general, the nurturing of vernacular political cultures was propelled by the reception of humanist tropes in a tradition of holistic images of the body politic. An organic political imagination stressed hierarchy and interdependence between the different parts of the body politic, while the order thus created acknowledged legitimacy in a recourse to violence under circumstances regulated by custom, thus fostering a language of political liberty and representation.Footnote 16

The monarchy of the Habsburg dynasty distilled a singular combination of those features. At its core, the kingdom of Castile, the military expansion and centralization of the monarchy played against the leverage of territorial representative institutions. The complete absence of a Reformation movement and the pro-Catholicism of the Habsburg Empire encouraged a rhetoric of meta-political goals that would exert a lasting influence over the whole legitimation discourse and the institutional setting of the so-called Catholic monarchy.Footnote 17 In this context, the reception of civic humanist rhetoric would be marked by regular manipulation of republican tropes on the part of official discourse.Footnote 18

Although Castilian humanists quickly adopted the available terminology of conflict, its use does not seem to have followed the expected pattern. The “War of the Comuneros” or Comunidades of Castile – a widespread urban revolt against the imperial aspirations of Charles V – would be referred to in learned circles not as a revolution but as a civil war.Footnote 19 Imperial expansion did not, for its part, enhance the former semantic field: already, during the colonization of the New World, recurrent power struggles and upheavals triggered by reforms regulating control over Indians were labelled in official and unofficial accounts as “guerras civiles” [civil wars];Footnote 20 intervention in confessional disputes in continental Europe helped in turn to naturalize the usage of “civil war” for defining conflicts involving non-Catholic minorities inside the empire.Footnote 21

Yet the link between riot and conspiracy was kept, if not stressed, and is well reflected in the conventional usage acquired by the term “motín”. Originally restricted to manifestations of military insurrection, the recourse to mercenary troops and the strong links between local military power and propertied groups made “riot” the usual term for referring to protests which erupted from resistance to Spanish domination and which involved the resort to violence by the populace.Footnote 22 It does not seem, however, to have provided enough semantic content by itself and was commonly reinforced by adding to it qualifying synonyms such as “rebelión” [rebellion] or “tumulto” [tumult].

The seventeenth-century Hispanic political culture saw no major evolutions in the semantic field of disorder. In other European principalities the synergies between constitutional crises and confessional disputes urged semantic distillations and evolutions. Instead, in the domains of the Catholic monarchy fiscal crises triggered by military drawbacks were not supplemented with religious conflicts, and constitutional matters affected only territories outside Castile, such as Catalonia, Naples, or Portugal. Once crushed, any “revolutions” breaking out in such regions could be discredited as disorderly events mainly expressing opposition to natural authority. Inside Castile, the stock of meaning was at first affected by the expansion of neo-stoicism, a current in political thought stressing obedience to authority as an expression of moral integrity and endurance in the face of the contingencies of political events.Footnote 23 In an institutional setting that fostered court factionalism, the rise of personal rule focused political intrigues and popular protest on trying to curtail the ascendancy of “strongmen”, or validos.Footnote 24 Outside the court, widespread but localized social conflicts seem to have been well covered by the inherited repertoire of terms.Footnote 25

By the beginning of the eighteenth century, the terminology available for publicists in the new Bourbon dynasty appears to have been characterized by a degree of semantic imprecision and interchangeability in conventional usage. In the Diccionario de la lengua castellana, published between 1726 and 1739 by the newly created Real Academia Española under Philip V (1700–1746), the term bullicio for example meant “contienda, alboroto, sedición o tumulto” [fight, turmoil, sedition, or tumult]; while alboroto could be taken to mean “tumulto, ruido, altercación, alteración, pendencia entre personas con voces y estrépito” [tumult, noise, fight, alteration, struggle between people with loud voices and sounds]. In the same official dictionary, “motín” was defined as “tumulto, movimiento o levantamiento del pueblo” [tumult, movement, or upheaval by the people], whereas “tumulto” stood for “motín, alboroto, confusión popular” [riot, turmoil, popular confusion].Footnote 26 All these terms were included in the juridical category of “bullicios” [rackets] and “conmociones populares” [popular commotions] inherited from Habsburg legislation.Footnote 27

The 1766 revolt and the limits of traditional vocabulary

However, other trends were developing at the same time. With the waning of the religious wars and the consolidation of absolutist monarchies, the reflection on conflict was deeply transformed all across Europe, and especially so after the events of 1688 in England, when for the first time a “revolution” had not led to the violence which would, according to the repertoire of the humanists, have been expected from sudden and radical political shifts.Footnote 28 Profiting from that, the term could subsequently make its way into depolitized public spheres as a metaphor for the speed and depth of change in social habits.Footnote 29 In turn, that semantic twist epitomized the emergence of a new language of natural rights and self-interested individuals, which became diffused through a discourse on wealth and knowledge as being spontaneously produced through communication and exchange.Footnote 30

In Spain, those trends were revised from the late seventeenth century onward by a generation of natural and moral philosophers who succeeded in outflanking traditional neo-scholastic knowledge.Footnote 31 By the mid-eighteenth century a rapid and deeply rooted reception of other major semantic bases of commercial society had taken place, and this gathered momentum during the short reign of Ferdinand VI (1746–1759).Footnote 32

As opposed to the language of civic virtue, that of interest as a source of wealth received enthusiastic recognition from the beginning not only among learned public figures and proyectistas [project-makers], but even from bureaucrats. With the accession to the throne of Ferdinand's brother Charles III (1759–1788), several policy measures were enacted on the basis of that inspiration, including intervention in public spaces of the capital with the purpose of emulating other major cities from other “civilized” nations. After reforming the organization of commercial exports, the monarchy essayed in 1765 a new system of urban commercial supply that ended the traditional monopoly exerted by local authorities and opened the market to middlemen.Footnote 33 The legislation was on the way to being implemented when, at the beginning of 1766, a typical combination of bad harvests and supply shortages caused the price of bread to soar, creating an atmosphere of popular unrest. At just the same time, the favorito of the king, the Marquis of Squillace, banned the inhabitants of the capital from wearing the usual long capes and round hats, using the argument that they were inappropriate for a civilized population. He imposed instead new costumes of foreign origin. A context already ripe for connecting food shortages, market speculation, and reforms was thus driven to the verge of explosion by a measure that touched upon a tradition of popular criticism towards arbitrary personal rule.

On 23 March 1766 the populace of Madrid revolted. The uprising grew in extent and intensity, lasting for three whole days, and resurfacing in other major cities of the country.Footnote 34 In a first move, quadrillas of commoners defied local authorities whenever they tried to force pedestrians to change their attire; they also attacked the house of the marquis and harassed other bureaucrats. The next day, as regular soldiers took to the streets, groups of men and women defied soldiers: scuffles with the royal guards produced over forty casualties from both sides. A crisis cabinet was summoned to court; the higher-ranking nobles and bureaucrats gathered around the king took the decision to comply with the people's demands, which included the removal of Squillace from office and the dismissal of the much-hated Belgian royal guards, as well as the repeal of the laws on grain markets and clothing.

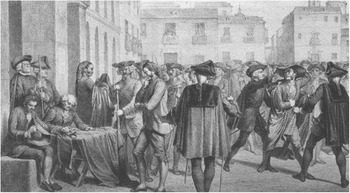

Figure 1 “El motín de Esquilache” [Squillace riots] (1766–1767), by Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828). The painting shows a Franciscan friar preaching the multitude in the second day of the riot against Squillace. It is supposed to represent Father Yecla, the monk who delivered the demands of the populace of Madrid to King Charles III. Priests were said to have emerged as spontaneous mediators between the rebels and the authorities, although this picture painted in the aftermath of the revolt stresses a perception of the populace as constituted by traditionalist religious values. Oil on canvas, 46 × 60 cm, private collection. Used with permission.

Even so, as the king abandoned the city without fully enacting the concessions, groups of organized locals entered military garrisons, armed themselves, and blocked the entrances to the capital, sending an embassy to the royal palace in Aranjuez. Charles III replied that he would return to the city and enforce the agreements once the revolutionaries had handed over power to the legitimate authorities. Only after three days of popular control of the capital did the authorities manage to restore order, although there remained unrest for weeks in the form of libel and other anonymous writings. Other major cities of the peninsula experienced upheavals as well; they followed a similar pattern, with popular assaults on public granaries and the houses of merchants.

Among enlightened bureaucrats, such an unexpected and uncontrollable outburst of collective violence prompted the urgent desire to discredit it as part of the efforts to re-establish order. That in turn implied a need to name, qualify, and classify the events. The first occasion for so doing in the short term came in June 1766, when a ceremony sponsored by the court was convoked for the purpose of asking the king to derogate the grants conceded to the populace.Footnote 35 A royal decree, issued for the occasion by the attorneys of the Council of Castile, described the revolt at length.

Apart from declaring the illegitimacy of the so-called Congregación extraordinaria de gentes de Madrid [Extraordinary Gathering of the People of Madrid], the popular collective action of March was rejected as being “nula”, “ilícita”, “insólita”, “defectuosa”, “obscura”, “violenta”, “de pernicioso ejemplo”, “obstinada”, “ilegal”, and “irreverente” [ineffective, illicit, unwonted, defective, obscure, violent, a dangerous model, obstinate, illegal, and irreverent]. The adjectives were explained in detail in order to justify the lack of recognition of the “congregación” as a collective entity: thus, it was qualified as ineffective because it lacked any capacity to represent; it was considered illicit because it did not seek the recognition of the Cuerpo del Ayuntamiento [Body of the Municipality], “sin cuya participación previa no podía deliberar nada” [without the aid of which it could not take any decision]; it was qualified as unwonted because “jamás el Pueblo de Madrid se acostumbra a congregar en Cuerpo formado” [the People of Madrid never congregate as a Body]. Summarizing, the subject of the spring riot had been an “abominable congregación de gentes fantásticas y díscolas” [abominable congregation of fantastic and unruly people] that could not claim any recognition at all because, as the attorneys wrote, “sobre un Cuerpo quimérico e incierto no puede recaer representación constante y verdadera” [there can be no constant and true representation attributed to a chimerical and uncertain Body].

It can be seen that each of the arguments deployed against the subject of the revolt made use of the available stock of organological images rooted in inherited constitutional language. Much the same can be said about the terminology offered to name the events: bullicio and alboroto were recurrently employed, although tumulto was the most usual term. Interestingly enough, motín does not appear in this official document, although it was the term most used in the discussions by courtiers leading to the decision to instigate the ceremony.Footnote 36 In spite of its vagueness and interchangeableness, the inherited terminology seems at first sight resilient enough to accommodate an episode of disorder much greater in intensity and extent than past experiences.

Yet official documents were not the only sources of discourse about the 1766 revolt. A look at some of the others provides us with a different image of the semantic context created by the motín de Esquilache.

Semantic crisis: a riot without conspiracy

Apart from “riot”, terms with strong implications such as “civil war” and “revolution” were discarded too in the first official assessment of the events. Although their use had initially been much refracted in the Hispanic political culture, they could have had a second chance as classificatory categories in the aftermath of the 1766 revolt. As part of the revisionism of foreign political philosophy, a more orthodox interpretation of civic humanist tropes was being offered in those years, especially through the reception of Montesquieu.Footnote 37 The new “strongman” at court, the Count of Aranda, himself sponsored a project full of republican overtones.

Actually, the summoning of the legitimate corporate bodies around the king reflected the rise of republican sensibilities in court circles in the aftermath of the revolt. It was not by chance that the declaration by the attorneys of the Council of Castile was preceded by a manifestation of loyalty signed up to by the nobility of the Villa y Corte.Footnote 38 The gathering of a body of the privileged was part of a plan devised by Aranda for a reorganization of the aristocracy around a sort of mixed constitution in the humanist tradition, which would act as a bulwark against corruption and disorder.

This constitutional programme in the making demanded an interpretation of the riot inspired by civic tropes. It would not appear in official documents, but it was offered in other works sponsored by the new group in power. Tomás Sebastián y Latre, a member of the circle of the Count of Aranda, published an account of the revolt taking place in another major city of the Iberian peninsula, Zaragoza, capital of the old kingdom of Aragon, a region with experience of representative institutions. Republican language pervades the narrative, focused on the repression of the popular tumult rather than on the upheaval itself.Footnote 39

The protagonists of the story are depicted as citizens in the ancient classical ideal successfully overcoming a situation of major social disruption. Neither civil war nor revolution are, however, used to define the events, and the author does not offer arguments for his avoiding both terms. That is all the more intriguing given that in his narrative the rioters of Zaragoza are characterized as embodying two of the features attributed in humanist literature to civil wars and revolutions: the low moral and social standards of the mobilized, and their recourse to violence when gathered in numbers in public spaces. Yet in excluding those terms Sebastián y Latre was perhaps adhering to a tradition.

For a third element was missing from the 1766 revolt, an element conventionally considered a sine qua non either of civil war or revolution: a conspiracy plotted by individuals from the upper ranks of society capable of manipulating the mob for their own immoral ambitions. In effect, an outstanding feature of the revolt against Squillace was the apparent absence of publicly declared or known leadership: the royal authorities did not detain any leader, and only a few priests were targeted, a move that led to an investigation which eventually ended with the expulsion of the Jesuit religious order from the domains of the Hispanic monarchy one year later, in 1767. The Jesuits were accused of having incited the populace, but not of conspiring in the conventional sense of the term: from an organological perspective, a conspiracy implied machinations by individuals, not by an institution as a whole, because integral parts of the body politic could not conspire as such.

The formal absence of a conspiracy in the motín de Esquilache contradicts the fact that the revolt began after the imposition of a measure partly aimed at forestalling possible conspiracies. In effect, Squillace had justified the banning of traditional costume by arguing that it was inappropriate for standards of civilization, but also because long capes and hats allowed people to conceal their faces in public places.Footnote 40 Once the revolt was over, the authorities declared their intention to detain those they assumed to have been the instigators; and yet it seems they failed to do so even after carrying out surveillance.

Over the decades, writers and scholars have addressed the question of whether there really was a conspiracy behind the 1766 revolt and, if so, who organized it.Footnote 41 However, contributions to the debate, which has involved both traditional political historians and classical social historians, have overlooked an important contextual element: since very early on, official discourse openly neglected the presence of any leadership in the revolt. In the document drawn up for the June 1766 ceremony, the general attorneys of the Council of Castile argued that the gathering of the populace of Madrid could not legitimately demand recognition “porque nadie aparece representando aquella especie de gentes” [because nobody appears to be representing that sort of people].Footnote 42

Figure 2 “Origen del motín contra Esquilache” [Origins of the riot against Squillace] (1864), by Eusebio Zarza (fl.1842–1881). Elaborated 100 years after the events, the picture evokes an episode in the enforcement in 1766 of the legislation banning the inhabitants of Madrid from wearing traditional long capes and round hats. Part of a wider set of political measures oriented to adapt the capital to “civilization”, the initiative implemented by local authorities triggered the riot against the favorito of King Charles III, the Marquis of Squillace. Although the revolt was caused by other deeper issues, this particular aspect was stressed in the Grand Narratives of nineteenth-century historiography, where it would be interpreted as a sign either of the love of liberty or traditional customs by the Spanish populace. Lithography in two inks, 154 × 240 mm in a sheet (255 × 360 mm), printed in J. Donon′s workshop.

In spite of apparent efforts to identify a conspiracy, it seems that the authorities were unwilling to credit the rioters with leadership. In the past, however, no conflict seems to have called for such an approach, which suggests in the first place that the protest was regarded as a particularly strong challenge to the established order and called therefore for an especially tough discursive response, even at the cost of abandoning the long-established convention of linking riots to conspiracies. If leaders were acknowledged, protesters would gain some kind of recognition for their demands; more particularly, if an aristocratic plot were revealed, Aranda's constitutional project based on the moderating role of the nobility would be openly questioned before its implementation, adding a crisis of legitimacy from above to the one from below represented by the popular revolt.

Neglecting the intervention of a conspiracy was one way of denying political personality to individual protesters, irrespective of their social background. That was a course of action that fitted well in a context of absolutist rule, which implied the complete depoliticizing of subjects. Blaming the instigation of the riot on the Jesuit order reinforced the inherited organic language of social order: it was assumed that, by eliminating what had apparently turned out to be a rotten member, the body politic as a whole would revitalize itself.

The contextual needs of legitimization seem to have been satisfied with the legacy of semantic referents. The assessment of a revolt without a plot created, however, its own linguistic problem: in the absence of suitable terminology, the term used in referring to the revolt against Squillace depended on experimentation.

Conceptual innovation within inherited language

In order to account for semantic experimentation in the aftermath of the March 1766 riot, we need to travel again, this time to Barcelona. The capital of the old principality of Catalonia witnessed no disorder, chiefly because the military governor had enough troops at hand to prevent it.Footnote 43 Once order had been re-established everywhere, local authorities also associated themselves with the wave of expressions of loyalty to the monarch; in this case, Catalan writers had a chance to interpret events from a more distant position.

Francisco Romá y Rosell, attorney in the city audiencia [court], took this initiative. In 1767, one year after the revolt, he published a work that was not just another pamphlet showing fidelity to King Charles III, but rather an entire Disertación histórico-político-legal sobre los colegios y gremios de Barcelona [Historical-Political-Legal Dissertation on the Corporations and Guilds of Barcelona]. Most of the text was actually a justification for the privileges of the city's guilds, and of corporations in general, which he saw as a basic referent for identity in a well-ordered society, and one that played a moral role reaching beyond its particular constituencies.Footnote 44

At first sight that had little to do with the issue at stake. Yet by arguing in favour of the social utility of corporations, Romá y Rosell's pamphlet focused on the role of guilds in situations of disruption to the social order. Corporations were a bulwark against disorder, but also the touchstone for their existence. In his view, revolts were the product of the malfunctioning of guilds, which resulted in an increasing inability to display their moral function over society as a whole. That perspective entailed a groundbreaking understanding of the sociological structure of the populace. For Romá y Rosell, the people did not exist as a separate, autonomous entity: they acquired personality only when duly incorporated and distributed among the different members that made up the body politic.

Such a radical version of organic discourse assumed a sociological distinction between good and evil subjects. In the humanist tradition no strong relationship could be established between the moral and the social bases of disorder: evil and passion were regarded as overall human temptations, the characteristic feature of the lower ranks being their potential exposure to both, and in large numbers, by manipulation from above. Instead, Romá y Rosell distinguished between a morally safe and reliable majority of members of corporations, and a minority of disenfranchized individuals who, excluded as they were from recognition and legitimate personality, easily became a threat to peace and order.

In fact, revolts were triggered whenever corporations failed to keep this marginal population under control. In his own words, if corporations and guilds were useful it was because “dan en todas partes pruebas de fidelidad cuando los vagos se amotinan” [they give proof of fidelity when the idle resort to mutinies].Footnote 45 Disorder necessarily started outside corporations. While dignifying the lower ranks when duly incorporated into guilds or exposed to their moralizing effects, such rhetoric degraded rebels ultimately because of their lack of corporate affiliation. Thus, anticipating the qualification offered by the founders of the psychology of masses, Romá y Rosell referred to the unreliability of the masses, a view that was not so much a reflection of moral prejudice on his part but one based on sociologically elaborated reflection.

The multitude was being conceptually outlined as a social entity. Interestingly enough, Romá y Rosell did not make use of the usual terminology when referring to participants in violent collective action. Official documents and accounts of the 1766 events speak of “la Plebe más infame y baxa” [the lowest and most infamous plebs];Footnote 46 instead of that he used the term “vagos” [idle], which, together with “ociosos” [lazy] and “malentretenidos” [of bad habits], was in that period acquiring the contours of a fully fledged semantic field.Footnote 47 The classification he devised thus supplemented moral prejudice with the division of labour as a vehicle for social inclusion and exclusion.

Making distinctions among the multitude based on social and economic characteristics paved the way for a reclassification of manifestations of disorder. Innovatively, Romá y Rosell reduced the inherited variety of rather unspecific and interchangeable terms to just two alternatives: “conspiraciones” [conspiracies] and “motines” [riots].Footnote 48 The latter were the type of mobilization natural for the idle. Not only that: appealing in the first place to disenfranchized vagabonds, riots could also attract members from guilds. There was a social limit to that however. In Romá y Rosell's view, whereas the rank and file could be dragged into revolt, the heads of corporations resisted becoming involved in violent collective action against authority.

Such explicit exoneration of the representatives of corporations placed Romá y Rosell's argument on the same line as the official rhetoric of riot displayed in the capital and the court. Further elaboration was needed, though, in order to clarify why the lower and upper layers of corporations were prone to different behaviour in a context of social agitation. That is where the distinction between conspiracy and riot played a crucial role. What defined riots was not just the protagonism of the idle; it was the singular character of its wider potential social bases. For Romá y Rosell, “por las más sólidas razones, y con la autoridad de la Historia” [according to the strongest of reasons and following the authority of History] it need be acknowledged that “los Plebeyos no tienen pensamientos, ni séquito para urdir conspiraciones” [plebeians have neither thoughts nor a retinue for plotting conspiracies].Footnote 49

Thus, Romá y Rosell was also founding the myth of the spontaneity of popular upheavals on sounder sociological ground: as opposed to the humanist tradition, for which the ephemeral character of revolts derived from the contingent display of evil in human affairs, collective action by the masses was now also seen as refracted by the social resources for mobilization at their disposal. He found the populace on the one hand unable to deploy the networks required for plotting conspiracies, that is, lacking enough material and social capital. That argument was, however, preceded by another, much more innovative and original one, according to which people of lower rank did not possess the intellectual status required for conspiracy. The sentence is rather ambiguous, though, and the lack of “pensamientos” can be understood in cognitive, educational, or moral terms; it probably involved a mixture of all three.Footnote 50 In any case, that vision superseded the inherited tradition that denied personality to the masses exclusively due to their moral standards: what defined the multitude now was its inability to elaborate autonomously the ideas needed for sustained collective action.

In a context prior to the rise of economics and sociology as instituted sciences, Romá y Rosell was outlining the contours of the semantic field of irrationality. That involved conceptual definition, which he drew from the emerging language of the Enlightenment, which assumed culture and knowledge as conditions for the useful employment of human reason. The combination of that with tropes from political economy resulted in a sociological conceptualization of disorder: all that the populace could unleash were riots, “motines”; by contrast, conspiracies were taken as the natural type of disorder practised by the upper echelons because, even if it was for morally reprehensible purposes, their cultural level assured them the capacity for an independent use of reasoning.

In making his case for classifying the revolt against Squillace as a riot, Romá y Rosell was offering the authorities an understanding of the popular upheaval that lacked any significant ideological dimension. That was a way of further depriving the revolt of legitimacy, and of reinforcing the official response to it. In order to do so, and to profit from the official denial of an aristocratic plot, he had to break discursively with the long-established tradition of including conspiracies as a sine qua non of relevant disorders. His alternative definition involved reflecting on the sources of unreliability, spontaneity, and irrationality. Even if he did not use the term multitud, the result was a definition which anticipated the scientific coinage of the concept 100 years later by the fathers of the behavioural sciences.

Conceptualization was part of the politics for restoring order after March 1766. That helps explain why semantic innovation was pursued within a well-established legacy of organic tropes of order. The redefinition of motín actually profited from the ambiguity of the inherited terminology of disorder. According to the Dictionary of the Real Academia Española, whereas a tumult was a revolt against superior authority in general, a riot was defined as an upheaval by the people or a multitude “contra sus cabezas o jefes” [against its heads or leaders]. Thus motín seemed better to suit Romá y Rosell's conceptualizing effort.

Nevertheless, his redefinition of the field of disorder involved a very distinctively modern ingredient: the incorporation of a new temporalization oriented towards the future. For Romá y Rosell, riots were to a certain degree legitimate processes of collective action. In his own words, as opposed to conspiracies, “los motines son consecuencia forzosa de los extremos de la libertad sin límites, y de la opresión del despotismo” [riots are the forcible consequence of the extremes of unlimited freedom and despotic oppression]. They could thus be anticipated and eventually avoided whenever order was “sujeto a una autoridad absoluta, pero moderada” [subject to an absolute, but moderate authority].Footnote 51

Far from justifying the revolt of March 1766, the author was demanding the sort of government which would be capable of avoiding future disorders. That placed Romá y Rosell in line with the growth of a new science of government – centred on the notion of police – that tried to reduce the impact of Fortuna over human affairs by a modern understanding of necessity overcome through knowledge.Footnote 52 Conceptualizations such as Romá y Rosell's were a prerequisite for those, since scientific discourse on politics could be elaborated only on the basis of concepts that incorporated a prognosis and anticipation of the future as a “horizon of expectations”.

In the case of Bourbon Spain, the aftermath of the crisis of 1766 witnessed a reorientation in institutional reforms from the promotion of commerce to social control; interestingly enough, its core was a whole policy of repression towards individuals lacking corporate affiliation.Footnote 53 If those measures could be successfully enacted it was in the first place because authorities could profit from a broader definition of riot as a mobilized aggregation of violent, disenfranchized individuals excluded from corporations. Defining and classifying revolt resulted in a major political event, deeply influencing the emerging institutional context after the motín de Esquilache.

Conclusion

In modern dictionaries, conspiracy and riot define rather opposite social phenomena; however, they had originally belonged to a common field by reference to which different instances of social disorder were named. Their semantic content became forever separated in the eighteenth century in the wake of popular revolts against Enlightenment reforms. The discourse surrounding the motín de Esquilache in Spain contains traces that allow for an interpretation of the way the process may have taken place in the context of the crisis of the Old Regime.

By depriving the masses of intellectual autonomy, Enlightenment discourse made a major contribution to the definition of modern dichotomies such as rationality/irrationality, multitude/minority, and publicity/secrecy. At the same time, it reconceptualized the social dimension of disorder, although that took place before the emergence of the social sciences, so that moral, cognitive, and social dimensions remained inseparable during the emergence of that conceptualization of the multitude.

From a wider perspective, the growing opposition between riot and conspiracy seems to have been part of a major transformation in learned culture, epitomized by the rise of critique as a socially embedded phenomenon.Footnote 54 One of its longer-term effects would be the shaping of new kinds of prejudice, about multitudes in general and about the lower ranks of society in particular, which were to reorient thoroughly the history of the semantic field of disorder.

The trends described in this article accelerated throughout Europe over the following decades. Police measures were partially successful in preventing and even curtailing riots, but they could not stop the expansion of another, ever more widespread phenomenon: the threats of conspiracy gathering momentum in the 1780s.Footnote 55 As with so many other issues, the French Revolution represented a dividing line in the social usage of conspiracy, where it was seen alternatively as an integral component of revolution or as its utter negation, although both possibilities had something in common. Each stressed the new definition acquired by the modern phenomenon of revolution, in which purposive action played a major role.

That complex relationship between conspiracy and revolution was to be inherited by liberal elites, at the expense of the traditional link between conspiracy and riot.Footnote 56 As the nineteenth century advanced, liberal discourse approached the repertoires of collective action used by those excluded from voting even more as reactive riots devoid of intellectual content regarding them.Footnote 57 It was in this interpretive background that the classical social psychology of the masses was produced.

Yet if social scientists coined the conventional definition of riot, social historians were crucial to diffusing it in the twentieth century. By classifying historical revolts as riots, they actively helped to divulgate the identification of popular protests with the spontaneous eruption of the masses driven by necessity. In a less conscious way, a positivistic usage of available sources often made them assume the common meta-narrative inserted in them, according to which the populace lacked the capacity to produce political ideas independently.

Renewed by several generations of social scientists and historians, the rhetorical power of this meta-narrative has not only made invisible the semantic process reconstructed here, but also deformed modern accounts of relevant historical revolts. In the case of the protest against Squillace, there are pieces of evidence that have never been made to fit properly into conventional accounts of the events. For example, the fact that rebels produced important political documents such as a so-called “Constituciones u Ordenanzas” [Constitutions or Ordinances] signed by a self-identified “Cuerpo Patriótico en defensa del Rey y del reino para quitar y sacudir la opresión con que se intentaba arruinar estos grandes Dominios” [Patriotic Body in defence of the King and Kingdom in order to eliminate the oppression that was trying to ruin these great domains].Footnote 58 Texts of that kind strongly suggest that 1766 was only partially a bread riot, or a protest against the decree banning traditional popular dress. It seems that there was in fact a discourse in the making which would reach beyond opposition to Enlightenment reforms.

It still remains to study the semantics of that discourse in detail, but also to assess the extent to which it was a product of popular communicative action, or a re-elaboration of other intellectual sources.Footnote 59 Social history and the history of political language could establish a space for collaboration there. Until today, however, social and political historians have preferred to stick to debating whether there was an aristocratic conspiracy behind the revolt, a line of interpretation that implicitly reproduces old prejudices about the capacity of the multitude for producing independent discourse and deliberation.

In recent years, the concept of multitude has been returned from the historiography to the political philosophical arena.Footnote 60 Its vindication as a legitimate collective agent of sovereignty in the globalized world has, however, been elaborated based on an interpretation of the classics of those who, like Baruch Spinoza, wrote before the semantic changes described in this article. Any chance of the concept of the multitude succeeding in the public sphere of the twenty-first century will require taking into consideration the cumulative effect of the layers of meaning incorporated since the eighteenth century into the conventional usage of the term, and in particular the deep effect that long-lasting prejudices have had on the inability of the masses to produce rational political deliberation.