Introduction

Aid and foreign direct investment (FDI) are both widely seen as means by which less developed economies can develop (Donaubauer, Herzer, & Nunnenkamp, Reference Donaubauer, Herzer and Nunnenkamp2014). The former is usually based on inter-governmental or bilateral agreements forged for humanitarian or geopolitical purposes, whereas the latter involves the profit-seeking behavior of multinational enterprises (MNEs). China's growing foreign aid and FDI over the past few decades, particularly in Africa, has sparked the interest of scholars and policymakers in part because of the complexities involved (Voss, Buckley, & Cross, Reference Voss, Buckley and Cross2010). Some studies suggest that Chinese aid has been used to pave the way for entry by its MNEs by reducing risk, building a munificent environment in host countries for Chinese firms, and establishing good political relationships with them (Morgan & Zheng, Reference Morgan and Zheng2019; Zhang, Yuan, & Kong, Reference Zhang, Yuan and Kong2010). Others argue that FDI projects by Chinese MNEs are national policy tools undertaken to support the Chinese government's economic, social, and political goals (Dreher, Fuchs, Parks, Strange, & Tierney, Reference Dreher, Fuchs, Parks, Strange and Tierney2018; Witt & Lewin, Reference Witt and Lewin2007).

The root of the differing views on Chinese aid and FDI is a strong suspicion of their relatively lower independence from their government. Since the 1990s, China has been using large state-owned enterprises (SOEs) as a vehicle for outward FDI in less developed economies (Arnoldi, Villadsen, Chen, & Na, Reference Arnoldi, Villadsen, Chen and Na2019; Jiang, Peng, Yang, & Mutlu, Reference Jiang, Peng, Yang and Mutlu2015). As the economic transition in China introduced market logic into Chinese SOEs (Child & Rodrigues, Reference Child and Rodrigues2005; Raynard, Lu, & Jing, Reference Raynard, Lu and Jing2020), they sought business opportunities in other countries, while continuing to support the Chinese government (Huang, Xie, Li, & Reddy, Reference Huang, Xie, Li and Reddy2017; Zhou, Gao, & Zhao, Reference Zhou, Gao and Zhao2017), for example, by procuring key resources to fuel China's economic expansion (Deng, Reference Deng2013). As the rapid economic transition continued, privately owned enterprises (POEs) emerged, along with their SOE counterparts, as prolific sources of FDI in developing and developed economies (Lardy, Reference Lardy2014; Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2018). Some have speculated that POEs are also acting as state agents (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Xie, Li and Reddy2017).

We answer the call of Witt, Li, Välikangas, and Lewin (Reference Witt, Li, Välikangas and Lewin2021) to explore the role played by governments and politics in international business and investigate whether Chinese aid influences SOE and POE FDI in Africa in different ways. We distinguish FDI projects conducted by Chinese SOEs from those of POEs and argue that SOEs are more likely than POEs to follow Chinese aid to a target country. Our rationale stems from the fact that SOEs operate under a hybrid government-market institutional logic, while POEs operate mainly under a market-oriented one (Boisot & Child, Reference Boisot and Child1996; Li, Cui, & Lu, Reference Li, Cui and Lu2014). We further test the distinction by examining how political and market environments influence the association of Chinese aid and the FDI decisions of the two.

We test this hypothesis, using hand-collected data from multiple sources, on a matched sample of 3,598 Chinese aid projects and 3,760 Chinese FDI events in 50 African countries between 2001 and 2015. Addressing potential causal direction and endogeneity concerns with conditional logit models and lagged dependent variables, we find a tendency on the part of both SOEs and POEs to invest in an African country which has seen an increase in its share of Chinese aid in the entire continent, but that the impact is significantly greater for SOEs than for POEs. We further test the institutional logic of this relationship and find that the effect of Chinese aid on FDI is stronger in the case of SOEs when the focal country has policies consistent with those voiced by China in the United Nations, but that this is not the case for POEs. In contrast, when the focal aid-recipient country has low investment risk, the association between aid and FDI deteriorates for POEs, while it remains undeterred for SOEs. Altogether, our findings provide clues that Chinese SOEs invest in Africa to support China's goals while POEs are likely to act as their own agents and are less likely to follow aid in low-risk countries.

Our findings contribute to three streams of literature. First, we extend previous research on the relationship between aid and FDI by borrowing from the varieties of capitalism literature and distinguishing between the reactions of Chinese SOEs and POEs following Chinese aid to an African country. Second, our research indicates that differences in institutional constraints within China also extend outside her borders. While SOEs are under coercive institutional pressure from their home and host governments, POEs may also act as free agents and seek economic returns from their investment in Africa. Our third contribution is about the mechanism through which profit-driven MNEs may take advantage of the close inter-government relationship between home and host countries. We show that the benefits could be a reduction in investment risk, as Chinese POE FDI in a host country is positively associated with Chinese aid when – and only when – the investment environment is high risk. We also offer some practical and policy implications.

Theoretical Background

Foreign Aid and FDI Location Choice

Foreign aid is material help given by one country to another country (or region). The recipient country is typically less economically developed than the donor and/or dealing with natural disasters or conflicts (Boone, Reference Boone1996). Foreign aid takes various forms, including, but not limited to, the shipment of emergency food and water, medical assistance, and other material, developmental, or technical assistance, grants, concessional loans, trade credits, and debt forgiveness (Bluhm et al., Reference Bluhm, Dreher, Fuchs, Parks, Strange and Tierney2018; Zeleza, Reference Zeleza2014). Donors often set well-defined goals, but the impact of aid on recipient countries is often complex and multifaceted (Garriga & Phillips, Reference Garriga and Phillips2014). Research on foreign aid examines its efficacy in achieving intended outcomes, such as improving infrastructure or the education system, or achieving economic growth (Boone, Reference Boone1996; Williamson, Reference Williamson2008). In another stream of research which attempts to explain why aid may not work as well as expected, researchers have uncovered unintended consequences arising from inefficient resource allocation in recipient countries (Harms & Lutz, Reference Harms and Lutz2006; Kimura & Todo, Reference Kimura and Todo2010) and non-developmental motives on the part of donors (Dreher et al., Reference Dreher, Fuchs, Parks, Strange and Tierney2018; Garriga & Phillips, Reference Garriga and Phillips2014). In general, regardless of intended outcomes or unintended consequences, foreign aid is presumed to benefit the recipient country in one way or another (Dreher et al., Reference Dreher, Fuchs, Parks, Strange and Tierney2018).

One major area of interest for scholars has been the effect of aid on bilateral relations, particularly FDI from a donor country to a recipient one (Nwaogu & Ryan, Reference Nwaogu and Ryan2015; Selaya & Sunesen, Reference Selaya and Sunesen2012). The mechanism is through the aid itself and other channels afforded by it. Aid is typically fundamentally and structurally facilitated by donor-country firms and organizations that have the capacity to carry out the intended mission. For example, in 2012, direct (i.e., non-multilateral) US aid projects in Afghanistan were initially almost entirely carried out by American agencies and companies – some were later subcontracted (Tarnoff, Reference Tarnoff2012).

The implementation of aid projects increases the exchange of information between donors and recipients and stimulates the building of formal and informal relationships. These confer legitimacy and social capital to the donor country, and garner MNEs recipient country knowledge (Kimura & Todo, Reference Kimura and Todo2010; Morgan & Zheng, Reference Morgan and Zheng2019). This not only lessens the possibility of conflict between donor-country MNEs and recipient-country stakeholders, but also engenders the building of trust and the possibility of developing joint business opportunities (Morgan & Zheng, Reference Morgan and Zheng2019; Stevens & Newenham-Kahindi, Reference Stevens and Newenham-Kahindi2017). The combination of such legitimacy creation and relationship-building paves the way for firms from a donor country to take advantage of opportunities in a recipient country at lesser risk (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Yuan and Kong2010). Furthermore, information gathered through aid projects is often helpful to donor-country MNEs as they become more knowledgeable about underdeveloped economies in which local data are absent, non-transparent, or unreliable (Garriga & Phillips, Reference Garriga and Phillips2014).

Scholars suggest that in addition to implementing agencies investing in recipient countries, in order to carry out aid projects, other firms from the focal donor-country follow aid to recipient countries (Morgan & Zheng, Reference Morgan and Zheng2019). Investing abroad is a crucial decision for MNEs. MNEs prefer to invest in more stable countries with lower environmental uncertainties (Delios & Henisz, Reference Delios and Henisz2003) and less liability of foreignness (Johanson & Vahlne, Reference Johanson and Vahlne2009), but also with more business opportunities (Dunning, Reference Dunning1998; Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2018). Aid can help in achieving most of these by strengthening inter-governmental relations between donors and recipients, or at least by signaling potential resolutions to uncertainties in the destination country (Garriga & Phillips, Reference Garriga and Phillips2014; Shapiro, Vecino, & Li, Reference Shapiro, Vecino and Li2018). As MNEs need to conform to institutional pressures in both home and host countries, friendly and stable inter-governmental relations between them reduce tensions caused by this duality (Kostova & Roth, Reference Kostova and Roth2002). MNEs that conform to the recipient country's institutional norms are able to reduce the liability of foreignness and minimize the likelihood of hostile action on the part of a host government (Asiedu, Jin, & Nandwa, Reference Asiedu, Jin and Nandwa2009). Indeed, Shapiro et al. (Reference Shapiro, Vecino and Li2018) find donor-country MNEs are much less likely to become involved in public disputes with a host government than MNEs from other countries. While home country aid does not necessarily reduce FDI risks or increase business opportunities (Harms & Lutz, Reference Harms and Lutz2006; Remmer, Reference Remmer2004), it does usually make recipient countries safer and more friendly, thereby increasing their attractiveness (Kang & Won, Reference Kang and Won2017; Kimura & Todo, Reference Kimura and Todo2010).

Chinese SOE and POE FDI

SOEs dominated China's economy during the central planning era. Now, after four decades of pro-market transition, the percentage of SOEs in China's economy has been substantially reduced and the SOEs remaining transformed into more market-oriented entities (Raynard et al., Reference Raynard, Lu and Jing2020). They receive less support from the government, and they are less constrained by it. SOEs take part in market competition. Some have gone public and are listed domestically, some even abroad (Haveman, Jia, Shi, & Wang, Reference Haveman, Jia, Shi and Wang2017). Nonetheless, Chinese SOEs and POEs are still quite different.

In China, SOEs are granted better property rights protection (Che & Qian, Reference Che and Qian1998), have easier access to scarce resources held by the government (Hanley, Liu, & Vaona, Reference Hanley, Liu and Vaona2015), and even have monopoly status in some key industries (Magnus, Reference Magnus2018). SOEs also enjoy a high status in China because of legitimacy spillovers from the government (Raynard et al., Reference Raynard, Lu and Jing2020), albeit this comes with an obligation to fulfill governmental economic, social, and political goals (Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Gao and Zhao2017). Due to their inherent hybrid nature and dual identities, Chinese SOEs may struggle to strike a balance between such obligations and market competitiveness (Guo, Huy, & Xiao, Reference Guo, Huy and Xiao2017).

Beginning in the 1950s, most Chinese FDI was undertaken by SOEs (Deng, Reference Deng2013). After China joined the WTO, POEs were permitted to engage in international expansion practices (Buckley et al., Reference Buckley, Clegg, Cross, Liu, Voss and Zheng2007). This slightly preceded China transitioning from being a major FDI recipient to an exporter of capital. Compared with the international expansion of Chinese POEs, that of Chinese SOEs is usually seen as undertaken to implement the government's earlier ‘Go-Out’ policy or a response to the more recent Belt and Road Initiative (Huang, Shen, & Zhang, Reference Huang, Shen and Zhang2022; Wang & Liu, Reference Wang and Liu2022). On the one hand, resources provided by the Chinese government may uniquely help SOEs deal with international market risk and latecomer disadvantages, but on the other hand, SOEs can be overburdened with state-related responsibilities. In some of these cases, links with the government provide SOEs with an unfair advantage to the extent that POEs are unable to compete (Tang, Wang, & Shen, Reference Tang, Wang and Shen2021).

POEs might enjoy an advantage stemming from favorable government policy (Lu, Liu, & Wang, Reference Lu, Liu and Wang2011), while at the same time, they might be hampered by requirements to secure permission to invest in a particular foreign country (Stevens & Newenham-Kahindi, Reference Stevens and Newenham-Kahindi2017). They might benefit from governmental support, and might also have to compete with SOEs for access to markets and resources (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Wang and Shen2021). POEs also differ from SOEs in that they tend to have a somewhat riskier approach to cross-border investment in order to acquire technology and brands (Lyles, Li, & Yan, Reference Lyles, Li and Yan2014) and to improve their economic performance (Ramasamy, Yeung, & Laforet, Reference Ramasamy, Yeung and Laforet2012). Furthermore, Ramasamy et al. (Reference Ramasamy, Yeung and Laforet2012) also suggest that SOEs are more likely to invest in risky countries, while POEs tend to focus more on commercially viable opportunities.

Conceptual Framework and Hypotheses Development

Chinese aid and FDI are both salient and controversial. Chinese aid to Africa started in 1956, shortly after the formation of the People's Republic of China. At that time newly independent African countries needed help in building their nations, and China was keen to support countries that did not want to be aligned with either the Soviet Union or the West (Zeleza, Reference Zeleza2014). From the 1980s, as its reforms and economic developments accelerated, China was deemed by some to be a ‘rogue donor’ and accused of using aid to secure geopolitical favors, natural resources, and other economic or non-economic benefits at the expense of the development and independence of recipient countries (Dreher et al., Reference Dreher, Fuchs, Parks, Strange and Tierney2018, Reference Dreher, Fuchs, Hodler, Parks, Raschky and Tierney2019; Strange & Humphrey, Reference Strange and Humphrey2019). In the second decade of the 21st century, Chinese aid to Africa attracted even more attention and controversy even though it amounted to less than one-fifth of one percent of the Chinese government's total aid budget, as opposed to over 5 percent in the 1970s (Morgan & Zheng, Reference Morgan and Zheng2019; Strange & Humphrey, Reference Strange and Humphrey2019). Today Chinese FDI and the rise of Chinese MNEs have become global business topics fraught with geopolitical tension. In 2020, China's total FDI flow to Africa was US$4.23 billion and its FDI stock had reached US$43.4 billion. At 2.8 percent of China's total FDI flow and 1.7 percent of its global FDI stock, it was the second smallest to any continent (MOFCOM, 2021). Scholars, policymakers, and the media continue to grapple with what makes Chinese aid and MNE FDI in Africa different from that of other countries (Lessard, Reference Lessard2014; The Economist, 2022), although little evidence has been found to support this (Demir, Reference Demir2016; Dreher et al., Reference Dreher, Fuchs, Parks, Strange and Tierney2018). Questions still swirl around Chinese SOE and POE FDI behavior in aid-recipient countries. We take an institutional view of SOEs and POEs to explore differences in their investment behavior in Africa.

Aid from China and Chinese SOE vs. POE FDI

Chinese aid may reduce risk and increase the payoff of SOEs and POEs investment in recipient countries, encouraging them to undertake FDI (Morgan & Zheng, Reference Morgan and Zheng2019; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Yuan and Kong2010). First, when the Chinese government provides assistance and enters into a bilateral relationship with a recipient country, it shows confidence in that country, which might be seen as a quasi-guarantee for Chinese investment (Asiedu et al., Reference Asiedu, Jin and Nandwa2009). In addition, sociopolitical risks in recipient countries may be lower if the conflict between the government in power and other stakeholders can be mitigated by an improvement in general welfare brought about by aid. Second, aid may have a vanguard effect that provides Chinese MNEs with access to local social capital and tacit knowledge (Morgan & Zheng, Reference Morgan and Zheng2019; Stevens & Newenham-Kahindi, Reference Stevens and Newenham-Kahindi2017), thereby reducing SOE and POE environmental and behavioral uncertainties and bringing to light business opportunities that require trust and cooperation in joint business development (Kimura & Todo, Reference Kimura and Todo2010).

Finally, regardless of whether the motives behind Chinese aid are purely humanitarian or other motivations are at play (Abdulai, Reference Abdulai2016; Dreher et al., Reference Dreher, Fuchs, Parks, Strange and Tierney2018), some scholars suggest that Chinese aid in Africa improves recipient country institutions (Arewa, Reference Arewa2016) and infrastructure (Donaubauer, Meyer, & Nunnenkamp, Reference Donaubauer, Meyer and Nunnenkamp2016), creating more information and investment opportunities for MNEs (Garriga & Phillips, Reference Garriga and Phillips2014). Chinese SOEs and POEs may follow aid trends in their FDI (Ebbers, Reference Ebbers2018; Li et al., Reference Li, Ding, Hu and Wan2014), irrespective of whether they intend to further the geopolitical goals of the Chinese government (Dreher et al., Reference Dreher, Fuchs, Parks, Strange and Tierney2018) or are motivated by other interests (Witt & Lewin, Reference Witt and Lewin2007).

Differences in the institutional forces to which SOEs and POEs are subject to may cause them to behave differently when investing in recipient countries. While both types of firms are under some pressure to further China's interests in a recipient country, this is more the case for SOEs because government ownership confers on them additional privileges and constraints (Morck, Yeung, & Zhao, Reference Morck, Yeung and Zhao2008). The equity linkage between SOEs and the government entails obligations that intensify institutional pressure. The top managers of SOEs are usually political appointees and are closely monitored at both the central and local government levels to ensure that they further sociopolitical goals as well as market efficiency (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Huy and Xiao2017). Indeed, at times SOEs pursue precarious sociopolitical objectives (Bass & Chakrabarty, Reference Bass and Chakrabarty2014) or attempt to exert tight control over key sectors and industries (Magnus, Reference Magnus2018; Zheng & Huang, Reference Zheng and Huang2018), even at the expense of profitability. In that sense, we might consider SOEs to be acting as government agents as opposed to being purely profit-driven. They are, therefore, more likely to follow Chinese aid to recipient countries in order to ensure that projects are implemented and political goals are met (Wang, Cui, Vu, & Feng, Reference Wang, Cui, Vu and Feng2022). In exchange, their interests are protected by state institutions, reducing the risks associated with investing in distant countries. The Chinese government gives SOEs resources and forgives their financial inefficiencies (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Xie, Li and Reddy2017; Li et al., Reference Li, Ding, Hu and Wan2014). Moreover, as the government accumulates social capital and local knowledge through its aid projects, SOEs’ closeness to the government gives them greater access to knowledge and more legitimacy than is the case for POEs.

Aid-recipient governments are also motivated to safeguard Chinese SOEs, as the property of the aiding government, from expropriation and conflicts with local stakeholders. Their motivation is to ensure the economic interests of the aid-providing government and maintain a good standing bilateral relationships and flow of aid (Asiedu et al., Reference Asiedu, Jin and Nandwa2009). Some have suggested that SOEs play on this strategy to elaborate on their identity with the Chinese government to increase their legitimacy and credibility (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Cui, Vu and Feng2022).

There is much less institutional pressure on POEs to pursue national interests, but they are also a few rungs below on the hierarchical ladder in terms of access to resources and they do not enjoy the same level of protection as SOEs (Magnus, Reference Magnus2018; Zheng & Huang, Reference Zheng and Huang2018). Host country protection could be afforded to Chinese POEs, but not as strongly as it is for SOEs in which the government has an ownership stake (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Cui, Vu and Feng2022). As POEs are not seen as having the same legitimacy in the eyes of aid-recipient governments, they are not treated in the same way unless they are subcontracting or partnering with SOEs (Ramasamy et al., Reference Ramasamy, Yeung and Laforet2012; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Cui, Vu and Feng2022). Furthermore, even though POEs might get a pat on the back for furthering Chinese interests, SOE managers are more likely to be rewarded with career promotions (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Huy and Xiao2017). For these reasons, POEs are more likely to follow a market-oriented logic created via institutional transformation and competition (Lazzarini, Mesquita, Monteiro, & Musacchio, Reference Lazzarini, Mesquita, Monteiro and Musacchio2021; Witt & Lewin, Reference Witt and Lewin2007). Therefore, regardless of whether SOEs are profit-driven or not, they are more likely than POEs to engage in FDI in countries that are recipients of Chinese aid.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): The likelihood of a Chinese firm making an FDI in a country will have a greater association with the relative share of aid the country received from the Chinese government if the firm is a SOE than if it is a POE.

Aid-Recipient Country Political Alignment with China

We expect the relative advantage that SOEs have over POEs when investing in a country to be amplified the more politically aligned the host country is with China. Such countries are more likely to see Chinese aid in a positive way, and aid is thus more likely to lead to greater social capital and legitimacy for the Chinese government, which it can then confer on SOEs, resulting in their enjoying a better reputation and higher levels of protection from recipient countries (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Cui, Vu and Feng2022).

Whether a country sends aid for humanitarian reasons, to gain access to critical resources, or to increase soft power (Arewa, Reference Arewa2016), the aiding government will try to protect its interests and image in the recipient country (Akhtaruzzaman, Berg, & Lien, Reference Akhtaruzzaman, Berg and Lien2017; Donaubauer et al., Reference Donaubauer, Meyer and Nunnenkamp2016). Chinese SOEs, as institutional actors (Butzbach, Fuller, Schnyder, & Svystunova, Reference Butzbach, Fuller, Schnyder and Svystunova2022), whether fulfilling their responsibilities to the state (Dreher et al., Reference Dreher, Fuchs, Parks, Strange and Tierney2018) or seeking economic returns (Bass & Chakrabarty, Reference Bass and Chakrabarty2014; Ralston, Terpstra-Tong, Terpstra, Wang, & Egri, Reference Ralston, Terpstra-Tong, Terpstra, Wang and Egri2006), will do the same. The coercive institutional pressure does not allow them to shirk these responsibilities. They are more likely to protect China's interests by making stronger commitments through investment in African countries whose policies are aligned with those of the Chinese government (Abdulai, Reference Abdulai2016; Dreher et al., Reference Dreher, Fuchs, Parks, Strange and Tierney2018; Lu et al., Reference Lu, Li, Wu and Huang2018). Indeed, SOEs are often implementing agencies of China's aid programs and are able to establish closer ties with the recipient governments to convey legitimacy and protect China's image (Morck et al., Reference Morck, Yeung and Zhao2008; Raynard et al., Reference Raynard, Lu and Jing2020; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Cui, Vu and Feng2022).

POEs, in contrast, are relatively free to follow market logic (Ramasamy et al., Reference Ramasamy, Yeung and Laforet2012; Yang, Ru, & Ren, Reference Yang, Ru and Ren2015), although they are expected to protect national interests to some degree (Lardy, Reference Lardy2014). Given the differences in responsibilities and potential benefits of SOEs and POEs, it is more likely that SOEs will invest in aid-recipient African countries that have policies aligned with those of China. African countries that support China on the international stage can expect to be rewarded with more SOE investment in addition to aid. Hence, we propose our second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 (H2): The political alignment of the aid recipient country with China can strengthen the positive association between the share of aid the country has received from the Chinese government and the likelihood of Chinese firms investing there, but the association is stronger for SOEs than for POEs.

The Desirable Investment Profile of Aid-Recipient Countries

Many studies (e.g., Ramasamy et al., Reference Ramasamy, Yeung and Laforet2012; Wang & Liu, Reference Wang and Liu2022) have shown that Chinese SOEs are more willing than POEs to operate in higher political risk countries. Borrowing from this logic, we hold that the institutional pressure on SOEs explains why they appear to pay less attention to economic factors such as destination country's investment risk, while POEs seem to respond more to market pressures and more driven by financial opportunities (Lazzarini et al., Reference Lazzarini, Mesquita, Monteiro and Musacchio2021). When operating in aid-recipient countries, SOEs are forced to act as national champions (Lazzarini et al., Reference Lazzarini, Mesquita, Monteiro and Musacchio2021) charged with helping to implement the Chinese government's agenda (Butzbach et al., Reference Butzbach, Fuller, Schnyder and Svystunova2022). The implementation of an aid project may be the very reason SOEs decide to invest in an African country, and thus it is not surprising that the success of the project will be their primary objective (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Cui, Vu and Feng2022). This is consistent with the role of SOEs to invest in countries that demonstrate political views congruent with those of China, and hence are likely to pay less attention to their investment risk profile.

Chinese SOEs seek to maintain China's and its aid's image as altruistic (Li et al., Reference Li, Ding, Hu and Wan2014). This is not to say that there are no other goals. Undoubtedly, China is interested in obtaining resources in many – if not all – of the African countries to which it supplies aid. However, it is important to China that it is not seen as an exploitative neo-colonial power (Abdulai, Reference Abdulai2016; Zeleza, Reference Zeleza2014), but that its motives are primarily seen as altruistic (Arewa, Reference Arewa2016). In their role as representatives of the Chinese government, SOEs are charged with helping on both fronts: building the image China wishes to project and protecting strategic resources in recipient countries (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Cui, Vu and Feng2022), even if those efforts are at the expense of financial performance (Zheng & Huang, Reference Zheng and Huang2018). In sum, while some SOEs try to improve performance through various strategies, such as outsourcing activities to POEs (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Cui, Vu and Feng2022), the legitimacy of China's intentions is vested in SOEs’ success in completing and implementing their projects (Lazzarini et al., Reference Lazzarini, Mesquita, Monteiro and Musacchio2021; Morgan & Zheng, Reference Morgan and Zheng2019), regardless of the financial risks involved (Li et al., Reference Li, Ding, Hu and Wan2014; Wang & Liu, Reference Wang and Liu2022).

In contrast, even though POEs may receive some support from the government and in return can be expected to consummate China's interests (Morgan & Zheng, Reference Morgan and Zheng2019), they are able to pursue a market logic (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Ru and Ren2015) and avoid high-risk regions (Lazzarini et al., Reference Lazzarini, Mesquita, Monteiro and Musacchio2021). They can be expected to balance return and learning opportunities against risk (Lyles et al., Reference Lyles, Li and Yan2014) and hence to generally prefer to operate in lower-risk, market-oriented countries (Ramasamy et al., Reference Ramasamy, Yeung and Laforet2012; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Ru and Ren2015).

Based on these institutional and ownership logics, we suggest that when the investment profile of an African country is deemed to be less risky and more profitable, POE investment will be less likely to follow government aid, in contrast to SOEs which are not allowed to be deterred by high risk. Hence our third and final hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 (H3): A low-risk investment profile in an aid-recipient country weakens the positive association between the share of aid the country has received from the Chinese government and the likelihood of Chinese firms investing there, more so for POEs than for SOEs.

Methods

Data

To test our hypotheses, we constructed a dataset from several sources. Approvals of investments in Africa by Chinese firms were hand-collected from China's Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM). The sample contains 3,760 investments by 2,120 MNEs from all 30 provincial-level administrative zones of mainland China between 2001 and 2015. MOFCOM stopped collecting firm-level data in 2015, hence the cutoff date. A large majority of these 2,120 firms are not publicly traded or are subsidiaries of partially public firms, making it impossible to obtain the size of their African investments or even the most basic firm-level information (e.g., employment size, revenues, etc.). We were able to find information on their ownership by manually matching firm names with data posted on Tianyancha (https://www.tianyancha.com), a corporate-intelligence website with information on Chinese firms.

We obtain data on Chinese official aid from AidData (Bluhm et al., Reference Bluhm, Dreher, Fuchs, Parks, Strange and Tierney2018). The dataset includes 3,598 projects in 50 recipient countries in Africa between 2000 and 2014. This database has been widely used in previous studies (e.g., Dreher et al., Reference Dreher, Fuchs, Parks, Strange and Tierney2018; Morgan & Zheng, Reference Morgan and Zheng2019; Strange, Dreher, Fuchs, Parks, & Tierney, Reference Strange, Dreher, Fuchs, Parks and Tierney2017).

Information on countries receiving Chinese aid is obtained from multiple sources, such as the World Development Indicators (WDI), the Centre d’Études Prospectives et d'Informations Internationales (CEPII), the International Country Risks Group (ICRG), the United Nations General Assembly, and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).

Measures

The list of all variables, a brief description of their measurement, and their sources are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Definition of key variables and their data sources

Dependent variable

Fifty of the 54 African countries received Chinese financial aid during the study period. MOFCOM reports the name of the company that made a direct investment in a country in a given year but not its amount. Therefore, following Li, Hernandez, and Gwon (Reference Li, Hernandez and Gwon2019), our dependent variable investijt is a dummy variable coded 1 if a firm i made an investment in country j in year t, and 0 otherwise. This means that if a Chinese firm made two investments in the same year or in different years, they are coded as separate entries. Similarly, firm i investing in two projects in country j in year t yields two entries.

We distinguish ownership and separate the sample into direct investments made by SOEs and those made by POEs. We manually collected information about the ownership of firms from Tianyancha. We defined SOEs as firms controlled by the central or local governments or by the State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission. Other firms were labeled POEs.

Independent variable

Due to the lack of transparency in China's official reporting, the specific aid projects in each country and their amount are not available. We measured a country's yearly amount of aid received from China (its AidRatio) by its share of all aid projects financed by China in Africa in that particular year. We obtained the data from Version 2.0 of AidData, an open-source collection of data that publishes the Chinese Official Financial Aid to Africa as a subset of the Global Chinese Developmental Finance Dataset, which it aggregates from multiple sources. While this source has been criticized for its lack of transparency, it has been used by previous scholars (Dreher et al., Reference Dreher, Fuchs, Parks, Strange and Tierney2018; Morgan & Zheng, Reference Morgan and Zheng2019; Strange et al., Reference Strange, Dreher, Fuchs, Parks and Tierney2017) and is the most reliable source currently available (Constantaras, Reference Constantaras2016).

Moderators

Political alignment of the recipient country with China's policies was measured by the similarity in votes cast each year at United Nations sessions (Bailey, Strezhnev, & Voeten, Reference Bailey, Strezhnev and Voeten2017). The variable is coded 1 if country j in year t voted similar to China, and zero if not.

The International Country Risk Guide (ICRG) proposes the investment profile, measured as the quality of a country's institutional environment and hence its level of risk. It has three subcomponents: contract viability and expropriation, profits repatriation, and payment delays. Each component is rated from 4 (best) to 0 (worst). We added scores for these three subcomponents to measure a country's level of risk, so the score varies from 12 (lowest risk or best investment profile) to zero (highest risk or worst profile).

Control variables

Table 1 shows the sources of the country-level variables we entered to control for endogeneity and other potential effects. One factor affecting foreign investment is geographic distance, so we control for that with the log of the number of kilometers between China and the host country (Mayer & Zignago, Reference Mayer and Zignago2011). We also control for bilateral investment treaties (BITs), which are coded 1 from the year when a BIT with China came into force, and 0 otherwise. We also entered ICRG indices measuring a country's government stability, law and order, level of internal conflicts, socioeconomic conditions, and level of corruption. We also controlled for other economic factors and include the natural log of the focal country's population, GDP per capita, and annual export value (the latter two variables are measured at constant 2014 dollars). To account for reverse causality and endogeneity, we also entered the lagged aid ratio as a control variable (Li, Ding, Hu, & Wan, Reference Li, Ding, Hu and Wan2021).

Analytical Methods

Conditional logit

Following Li et al. (Reference Li, Cui and Lu2019), we use the conditional logit estimator to test our hypotheses. This model estimates the conditional probability that a Chinese firm will choose to invest in a particular country from a set of alternative investment locations (Tan & Meyer, Reference Tan and Meyer2011). We model the probability of MNE i investing in country j in year t as:

where Pijt is the probability of firm i, whether SOE or POE, investing in country j in year t; X is a set of explanatory variables in year t−1; k is the set of alternative investment locations; and β is the coefficient of maximum likelihood estimation of the probability that the explanatory variables will affect the dependent variable. The variance in this model is across country attributes. Factors that do not vary across countries are directly accounted for, similar to a fixed effect. Thus, firm characteristics are included in this model (Greene, Reference Greene2018).

Potential endogeneity

We used several techniques to deal with potential endogeneity and performed supplementary analyses. Amongst them, we lagged all explanatory variables by one year to account for possible reverse causality, and lagged the independent variable by 2 years to control for unobserved firm characteristics that may cause endogeneity problems. We employed conditional logit estimation to solve some of these problems by accounting for the variance of firm attributes and unobserved factors. We also utilized instrumental variables to eliminate potential endogeneity issues.

Results

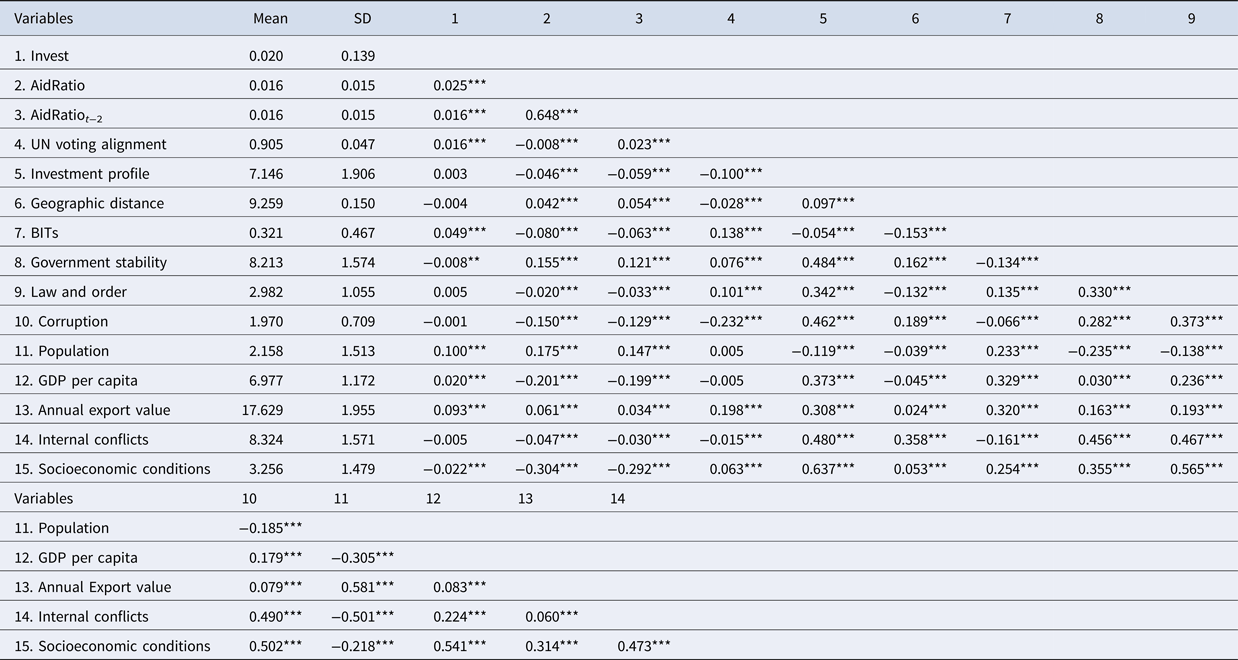

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics and correlation matrix. We calculate the variance inflation factors (VIFs) to test for multicollinearity. The average VIF is 1.83, and the maximum is 2.71, both well below the recommended threshold of 10 (Ryan, Reference Ryan2008). The recentering approach is a simple mathematical transformation that helps to assess interaction effects in non-linear models. Following Jeong, Siegel, Chen, and Newey (Reference Jeong, Siegel, Chen and Newey2020), we center moderators prior to creating the interaction terms. McFadden's R-squared are reported as pseudo R-squared to show the goodness of fit of the models. Unlike the generic R-squared in OLS analysis, pseudo R-squared is specific to logit and conditional logit estimation and does not have the same interpretation as R-squared. Pseudo R-squared is used more for comparing the fit of different models on the same dataset rather than as an absolute measure of goodness of fit, which is what R-squared is used for (Cameron & Windmeijer, Reference Cameron and Windmeijer1997). Taking Models 2 (for SOEs) and 3 (for POEs) as the baseline, entering independent variables and interaction terms in models 4–5, 6–7, and 8–9 yield larger pseudo R-squared.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix

Notes: **Indicates significance at the p ≤ 0.05 (***p ≤ 0.01) level of confidence.

H1 predicts that the likelihood of a Chinese firm investing in an African country is higher the share of that country in China's total African aid disbursements in the previous year, and that the increase will be greater for Chinese SOEs than for Chinese POEs. Model 1 of Table 3 is the baseline model, which only includes control variables. Model 2 tests how China's aid to a given African country affects the likelihood of SOE FDI in that country the following year. The coefficient of aid ratio in Model 2 is positive and significant (β = 9.113, p ≤ 0.001), which means that the higher the country's share of the Chinese African aid, the higher the likelihood Chinese SOE will invest in it the following year. Model 3 shows that the same relationship is also statistically significant for POEs (β = 3.855, p ≤ 0.1). We use seemingly unrelated estimation (SUEST) to test whether the coefficients are statistically different. The results show that the coefficient of aid on SOE FDI is larger than that on POE FDI, and that this difference is statistically significant after joint post-estimation (β = 2.760, p ≤ 0.1). Thus, H1 is supported.

Table 3. Results of conditional logit regression analyses of the likelihood of SOE and POE FDI decisions

Notes: Robust standard errors are in parentheses. *Indicates significance at the p ≤ 0.10 (**p ≤ 0.05; ***p ≤ 0.01) level of confidence.

H2 suggests that the political alignment with China moderates the positive association between aid and FDI proposed in H1. We predicted that this relationship would be more significant for SOEs than for POEs. Model 4 of Table 4 shows that the coefficient for the interaction term between a country's aid ratio and its UN voting alignment with China is positively significant for SOEs (β = 185.7, p ≤ 0.05), while Model 5 shows that it is not significant for POEs (β = −46.69, n.s.), providing support for H2.

Table 4. Results of conditional logit regression analyses of the moderation role

Notes: Robust standard errors are in parentheses. *Indicates significance at the p ≤ 0.10 (**p ≤ 0.05; ***p ≤ 0.01) level of confidence.

H3 predicts that the positive association between the share of the Chinese African aid an African country receives and the probability that a Chinese firm will subsequently invest in the country is weaker if the target country is deemed low risk, and that this is more marked for POEs than for SOEs. Model 6 in Table 4 shows that the impact of the interaction between the share of aid and host country investment profile is not significant for SOE investment (β = −1.094, n.s.), while Model 7 of Table 4 shows that it is negative and significant in the case of POEs (β = −2.239, p ≤ 0.05). These results support H3.

Supplementary Analysis and Potential Endogeneity

We performed four sets of supplementary analyses to investigate alternative explanations and rule out endogeneity. Please refer to the Supplementary material to this article for detailed explanations and results. The first supplementary analysis tackles the endogeneity issue inherent in the aid–FDI relationship and the role of home country firms as implementing agencies. To deal with these issues, we omitted all entries by Chinese firms that we determined were implementing aid projects. This did not change our results.

To deal with potential endogeneity, we find an exogenous instrumental variable for the aid ratio from China. We use net official development assistance the recipient country received from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries each year, sourced from the World Bank Indicators. OECD's assistance to each country is unlikely to be associated with Chinese MNEs’ FDI location choice because Chinese companies are far less likely to invest in a country following other countries’ aid or being the implementing agency for them. The results of the main effect model show that the effect of the instrument variable is statistically significant and positive; hence supporting our main hypothesis.

We also investigate an alternative measure for our main independent variable, the level of aid provided by China to each African country. We replace the aid ratio by the number of aid projects a recipient country receives each year. The results are very similar to our main analyses and support our hypotheses. The final test uses a different methodology, a mixed logit model, to deal with unobserved heterogeneity. Again, the results are similar.

Discussion

The surge in Chinese FDI over the past two decades is a complex phenomenon that has drawn scholarly attention from numerous economic and political perspectives (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Xie, Li and Reddy2017). One salient issue is the significant influence the government has on Chinese MNEs (Arnoldi et al., Reference Arnoldi, Villadsen, Chen and Na2019; Deng, Reference Deng2013). Many believe that the FDI of Chinese MNEs in some politically unstable African countries is driven more by what is in the interest of the Chinese government than by profit-seeking (Voss et al., Reference Voss, Buckley and Cross2010). This notion is fueled by marked signs that Chinese MNEs have followed the same pattern as Chinese aid projects in Africa (Morgan & Zheng, Reference Morgan and Zheng2019; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Yuan and Kong2010). In this study, we investigate two ways by which the government may be influencing Chinese MNEs investing in Africa. One has to do with Chinese aid to focal African countries and the other is government ownership.

Our findings show that Chinese aid projects in African countries are significantly associated with the likelihood of Chinese FDI in those countries, although that likelihood is higher for SOEs than for POEs. We argue that aid strengthens inter-governmental relationships between China and recipient countries (Morgan & Zheng, Reference Morgan and Zheng2019; Stevens & Newenham-Kahindi, Reference Stevens and Newenham-Kahindi2017), and that Chinese SOEs are in a better position than POEs to reap the benefits because they are owned by the government (Morck et al., Reference Morck, Yeung and Zhao2008).

Our findings also indicate that SOEs seeking to invest abroad may be due to greater government pressure, while POEs are more likely to pursue market opportunities. When SOEs invest abroad they are more constrained by Chinese national policies and objectives, such as Five-Year Plans (Li et al., Reference Li, Ding, Hu and Wan2014). They might be said to have a hybrid nature in that they are both government agencies and market players, and as such their FDI has a dual purpose. First, SOEs are more likely to act as intermediaries that implement the Chinese government's aid projects (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Cui, Vu and Feng2022), while also being economic entities. Second, Chinese SOE FDI in an aid-recipient country clarifies the vague purposes and subsequent consequences of the aid. They are friendship bridges between China and African nations while also ensuring the protection of China's national interests. Previous studies have sought to explain the link between Chinese aid and SOE FDI by a need for resources to fuel China's economic development (Dreher et al., Reference Dreher, Fuchs, Parks, Strange and Tierney2018). Our findings suggest that SOE FDI may also serve as a channel to ensure that the recipient country engages in international policies that are aligned with those of China. In contrast, we find that POEs do not only follow SOEs abroad in response to China's Go-Out policy, but also take advantage of Chinese aid in a recipient country to pursue market-based opportunities. This is shown by the fact that their FDI only follows Chinese aid in the case of high-risk countries.

The limitations of this study are primarily due to data. Since the Chinese government does not release official, project-level financial information about its foreign aid activities, we had to rely on AidData, which synthesizes and standardizes a large amount of public information on Chinese aid to African countries – see Dreher et al. (Reference Dreher, Fuchs, Parks, Strange and & Tierney2021) and Strange et al. (Reference Strange, O'Donnell, Gamboa, Parks and Perla2014) for this source and its limitations. Despite our best efforts, we were not able to find the amount of government aid or firm FDI in each African country and so resorted to using a country's share of the total Chinese aid budget for Africa and whether a Chinese firm invested in the focal country. For this reason, we cannot claim causality, but conditional correlations. Future research might attempt to collect data on the amount of aid granted to a particular country and see whether this affects the results.

Theoretical Implications

Despite limitations, we make three theoretical contributions. Our first is the literature connecting aid, FDI, and varieties of capitalism in the Chinese context. The findings of previous empirical studies on the relationship between aid and FDI, in general, have been mixed (e.g., Harms & Lutz, Reference Harms and Lutz2006; Selaya & Sunesen, Reference Selaya and Sunesen2012), but scholars have found a consistently positive relationship between aid and FDI from donor countries (e.g., Kang & Won, Reference Kang and Won2017; Kimura & Todo, Reference Kimura and Todo2010). We find, at least in the case of China, that aid has a ‘vanguard effect’ (Kimura & Todo, Reference Kimura and Todo2010; Stevens & Newenham-Kahindi, Reference Stevens and Newenham-Kahindi2017) that attracts MNE investment to aid-recipient countries. We suggest several reasons for this and show their mechanisms, but propose that the observed outcome depends chiefly on the nature of Chinese MNEs (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Cui, Vu and Feng2022) and on differences between SOEs and POEs (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Wang and Shen2021). The singularity of the view of Chinese MNEs that may state that all Chinese MNEs are agents of the government may have prevented us heretofore from understanding the real purpose of Chinese SOEs and POEs. By this, we mean that Western MNEs are often seen as acting independently from their governments, while scholars and policymakers often view Chinese MNEs as being an extension of the state charged with heralding China's soft power (Lazzarini et al., Reference Lazzarini, Mesquita, Monteiro and Musacchio2021). We do not intend to refute that one of the roles of Chinese MNEs is establishing Chinese soft power abroad, but we do want to draw attention to our findings that POEs are more aligned with market logic than with government policies (Lardy, Reference Lardy2014). In addition, although Chinese SOEs do have certain obligations to the state, they can also contribute to the development of host countries. Future studies might revisit other aspects of Chinese MNE behavior with the understanding that SOEs and POEs operate under different rules under different capitalist or other systems rather than the assumption that they are homogeneous.

Second, our research contributes to the broader international business literature by answering calls (e.g., Wang et al., Reference Wang, Cui, Vu and Feng2022; Witt et al., Reference Witt, Li, Välikangas and Lewin2021) to investigate the relevant unexplored role of political influence on international business (e.g., Wang et al., Reference Wang, Cui, Vu and Feng2022; Witt et al., Reference Witt, Li, Välikangas and Lewin2021). Chinese aid has been criticized by some for being less development-oriented than that of Western countries, indeed China has been accused of harming institutions in recipient countries (Halper, Reference Halper2010), although others counter such accusations (Arewa, Reference Arewa2016; Dreher et al., Reference Dreher, Fuchs, Parks, Strange and Tierney2018; Zeleza, Reference Zeleza2014). Chinese MNEs investing in Africa are sometimes portrayed as helping the Chinese government further its geopolitical goals (Morgan & Zheng, Reference Morgan and Zheng2019), and sometimes as shrewd profit-seeking businesses with superior entrepreneurial and managerial skills that can be adept at dealing with weak African institutions (Wang & Liu, Reference Wang and Liu2022). We find that the institutional constraints on SOE FDI decision-making lead them to prioritize the agenda of the government over economic opportunities. There is no contradiction in Chinese SOEs helping the government build bridges with African countries and nurturing jointly held global interests, but also seeing to their own interests as MNEs. In other words, it is not a case of either-or, but rather of MNEs taking on an additional layer of responsibility.

Our third contribution is to highlight the conditional association between POE investment and Chinese aid. The primary motivation of Chinese POEs is not the furtherance of government goals, but the pursuit of economic opportunities in Africa that grow out of Chinese aid. However, when their economic interests are at risk, POEs rely on the legitimacy, social relationships, learning, and business opportunities Chinese aid creates. Our results complement previous studies that have found that Chinese POEs are risk averse in their FDI (e.g., Ramasamy et al., Reference Ramasamy, Yeung and Laforet2012) and provide the boundary condition of institutional support in high-risk environments.

Practical Implications and Future Studies

Our findings do not support the criticism leveled at Chinese SOEs – or POEs. SOE FDI has broad strategic objectives (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Shen and Zhang2022), which go beyond asset-seeking and market expansion. We acknowledge that SOEs pursue strategic assets, such as natural resources, and that they are also charged with implementing aid projects (Abdulai, Reference Abdulai2016). Meeting this multitude of obligations can make for quite complex situations. However, aid-recipient countries stand to gain from this and create win-win situations by actively directing FDI from donor countries to partnership with key industries and firms. Such relationships with profit-seeking MNEs can further target economic development in aid-recipient countries (Lyles et al., Reference Lyles, Li and Yan2014).

Chinese aid is increasing globally. Can that aid be structured in such a way as to further Chinese domestic economic development and its POEs as well as aid-recipient countries? Assuming the Chinese government's plan is to increase its soft power (Arewa, Reference Arewa2016) and to protect its interests and image in aid-recipient countries (Akhtaruzzaman et al., Reference Akhtaruzzaman, Berg and Lien2017), what role might POEs play? African countries are eager to have better technology and to benefit from scientific advances through FDI to fuel their development, but the potential contribution of Chinese firms, particularly that of SOEs, although much cheaper, may be perceived to be not nearly as good as that of their Western counterparts. However, in recent years, many Chinese POEs have emerged to possess superior technology with known positive images. Future studies might investigate whether well-known POE FDI can further China-brand recognition without relying on help from the government. As an extension, future studies can probe whether POEs are more effective than SOEs in utilizing aid to improve China's soft power in Africa and other developing nations.

Funding statement

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 72072099), [2021/01-2024/12].

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/mor.2023.33

Xuanjin Chen (chenxj@swjtu.edu.cn) is an assistant professor at School of Economics and Management, Southwest Jiaotong University. She received her PhD in Business Administration from Tsinghua University. Her research interests include firm globalization, innovation knowledge spillover, and non-market strategies. Her work has been published in journals such as the Journal of Business Research, Business Strategy and the Environment, and Management and Organization Review.

Majid Ghorbani (majidghorbani@ceibs.edu) is an associate professor of practice at the China Europe International Business School. His primary research interests lie in the role of formal and informal institutions on firms’ innovation, entrepreneurship, and CSR strategies. He received his PhD in International Business from Simon Fraser University and his BA in International Politics from Peking University. His research has been published in the Journal of Business Ethics, International Business Review, and Management and Organization Review.

Zhenzhen Xie (xiezhzh23@mail.sysu.edu.cn) is a professor in the Business School, Sun Yat-Sen University, China. She received her PhD from School of Business at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. Her work has been published in the Journal of International Business Studies, Management Science, Asia Pacific Journal of Management, among others. Her research interests include firm internationalization, non-market strategies, and innovation in emerging economies.